94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 17 August 2022

Sec. Public Health Policy

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.934237

This article is part of the Research Topic Addressing the Sustainable Development Goals "Leave No One Behind" Promise: Migration and Health View all 14 articles

The total number of migrant elderly following children (MEFC) has gradually increased along with population aging and urbanization in recent decades in China. The purpose of this study was to investigate the mediating effect of family support on the relationship between acculturation and loneliness among the MEFC in Jinan, China. A total of 656 MEFC were selected by multistage cluster random sampling. Loneliness was measured using the short-form UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-8), while acculturation and family support were assessed using a self-designed questionnaire. Descriptive analysis, univariate analysis, and the structural equation model (SEM) were conducted to illustrate the relationship between the above indicators and loneliness. The average ULS-8 score of the MEFC was 12.82 ± 4.05 in this study. Acculturation of the MEFC exerted a negatively direct effect on loneliness and a positively direct effect on family support simultaneously, while family support exerted a negatively direct effect on loneliness. Family support partially mediated the relationship between acculturation and loneliness [95% CI: −0.079 to 0.013, p < 0.001], while the mediating effect of family support accounted for 14.0% of the total effect. The average ULS-8 score of 12.82 ± 4.05 implied a low level of loneliness in the MEFC in Jinan, China. Acculturation was found to be correlated with loneliness, while the mediating role of family support between acculturation and loneliness was established. Policy recommendations were provided to reduce loneliness and improve the acculturation and family support of the MEFC according to the findings above.

As the population has aged and urbanization has increased in recent decades, the number of migrant elderly has increased in China (1). According to the data of the Seventh National Population Census of China conducted in 2020, there were 375 million migrants, with a 70% increase seen over the past decade. Among them, 124 million were inter-provincial and 251 million were intra-provincial (2). Meanwhile, the proportion of the elderly among the migrant population in China continually increased from 4.9% in 2000 to 5.3% in 2015 (3). Among the significant number of the migrant elderly in China, those who migrated from their original residence following their children to another city in China in order to take care of the younger generation or to receive healthcare services were defined as the migrant elderly following children (MEFC) (4). The MEFC left their hometowns where they had lived for a long time and migrated to unfamiliar cities. The new living environment of the inflow cities may cause various problems for the MEFC, such as lifestyle changes, shrinkage of social networks, and unfamiliarity with local languages. These problems could also lead to physical discomfort, less social participation, lower acculturation, loneliness, and other mental health problems. The MEFC have thus become a vulnerable group in China's fast economic and social development and deserve more focus and research (5).

Peplau and Perlman suggest the following definition for loneliness: “loneliness is a painful feeling, usually a feeling that one's social needs are not met by the quantity or quality of one's social relationships, especially the quality (6, 7).” According to previous research, the level of loneliness increased with age among the elderly, especially those over 70 years old (8, 9). Tao's research revealed that the MEFC are more likely to feel loneliness in a new environment, which further affects their interpersonal relationships (10). Chinese immigrants in Canada were found to be lonely in Tam and Neysmith's study because their dependent children were unable to provide them with enough emotional support (11). In addition, a study on immigrants to Canada found that second-generation immigrants were lonelier than native-born Canadians (12).

Redfield defined the concept of acculturation as follows: “Acculturation comprehends those phenomena which result when groups of individuals having different cultures come into continuous first-hand contact, with subsequent changes in the original cultural patterns of either or both groups” (13). Studies have shown that the MEFC would face acculturation problems, including language, diet, customs, values, religious beliefs, etc. (14), while low levels of acculturation could further lead to high levels of loneliness (15, 16). Research among elderly immigrants in New Zealand reported that the challenges of loneliness for older immigrants stemmed from problems with culture, language, etc. (17). One study among migrant children in China found that migrant children with low levels of acculturation and social acceptance might experience greater stress and loneliness (18). Although previous studies have explored the relationship between acculturation and loneliness among elderly immigrants and migrant children, there is no research that has examined this association among the MEFC.

The loneliness experienced by the elderly in China is mainly affected by family support from spouses or children, etc. (19). A review by Bai described how harmonious family relationships could enable the MEFC to obtain reliable emotional support and avoid loneliness (20). A further study found that the disabled elderly with high levels of family support had lower levels of loneliness in Tangshan, China (21). It was also found that good family support could lead to better care and could reduce the loneliness of the elderly in Shanghai, China (22). A survey of elderly people in rural Anhui Province, China found that there was a high degree of loneliness, and social and family support played an important role in the development process of loneliness (23). Family support was also confirmed to play an important role in alleviating loneliness among older adults in a study of elderly Malaysians (24). High levels of family support were observed to be capable of preventing the loneliness of patients with cancer in Turkey (25). Although there have been studies on the relationship between family support and loneliness, there are relatively few studies on the MEFC.

Concerning the relationship between acculturation and family support, the existing research has generally found that family support increased with acculturation. Jewell's study revealed that higher acculturation led to higher family support among Mexican American women (26). One study of Chinese American older adults showed that good family support and cohesion could promote their acculturation (27). In addition, previous studies revealed that higher acculturation of children would lead to lower family support of their parents (28). Perez-Brena's research found that it might be easier for young immigrants to integrate into the local area than their parents and they accordingly had a higher degree of acculturation which would lead to differences in cultural values between young immigrants and their parents resulting in lower family support for the migrant elderly (29). Relatively few studies have investigated the association between acculturation and family support and we are not aware of any studies that have examined this relationship among the MEFC.

No research could be found to clarify the relationship between acculturation, family support, and loneliness simultaneously, while more attention has been paid to the relationship between acculturation, family support, and mental health (30). In a study of high school students who migrated to Norway, the cultural impact on mental health was found to be mediated by family support (31). In addition, a study of Chinese American older adults found that acculturation could affect the mental health of older immigrants through family support (32).

In summary, some studies have explored the relationship between acculturation and loneliness, family support and loneliness, and acculturation and family support, yet no research has ever clarified the association between acculturation, family support, and loneliness simultaneously, nor mentioned the MEFC as the research subject. This study aimed to clarify the relationship between acculturation and loneliness, and further verify whether there was a mediating effect exerted by family support on this relationship among the MEFC in Jinan, China.

Shandong Province is located in the east of China and Jinan is its capital city. Its GDP in 2020 was about 1.01 trillion Yuan (about US $158 billion), an increase of 4.9% over the previous year. As of 1 July 2020, Jinan has jurisdiction over 10 districts, two counties, 132 streets, and 29 towns. By the end of 2020, Jinan had a permanent population of 9.2 million, with an average annual growth rate of 1.27%. Among the permanent residents, the population living in towns is 6.76 million, accounting for 73.46%, and the population living in the countryside is 2.44 million, accounting for 26.54% (33). The seventh census showed that Jinan had a migrant population of 1.83 million (2).

The data were collected in Jinan, Shandong Province, China in August 2020. The subjects of the study were the elderly over 60 years old who followed their children to Jinan, China. This study adopted the method of multistage cluster sampling to select subjects. In the first stage of data collection, three regions were selected from a total of 10 regions as primary sampling units (PSU), considering the economic development and geographical location of Jinan, China. In the second stage, three zones were selected from each primary sampling unit (PSU) as secondary sampling units (SSU). In the third stage, three communities were selected from each SSU. Then, in these three communities, all elderly people over 60 who migrated with their children were taken as the total sample of this study.

In this survey, a total of 32 college students acted as investigators and received training on research background information, questionnaire content, and social survey skills. The investigators collected data in the form of face-to-face interviews with the subjects for about 20 min each. A total of 670 MEFC were selected and interviewed at first. However, 14 of them were excluded because there were obvious logical errors in their answers or their questionnaires were not completed. A total of 656 MEFC in Jinan, China were ultimately included in the study.

The theoretical basis is based on anthropologist Oberg's Culture Shock Theory. It refers to the sense of loss and accompanying anxiety in the process of cultural transformation. Oberg believes that culture shock is the result of an individual's contact with a different culture, such as tension and anxiety, and it is also the individual's sense of loss, confusion, and incompetence due to separation from the familiar culture and social symbols of the original culture. Studies have shown that culture shock generally goes through four stages, honeymoon stage, depression stage, adjustment stage, and adaptation stage. The change process of these four stages generally takes the form of a “U”-shaped curve. In the third stage, when immigrants gradually understand the difference between the original culture and the foreign culture, and gradually understand the local customs, they begin to adjust their emotions, gradually get out of the painful emotions, and gradually have their own social contact, with certain social support, which will lead to the gradual reduction of psychological loss and loneliness (34). Based on the culture shock theory, a structural equation model between the acculturation, family support, and loneliness of the MEFC was constructed in this study. When the MEFC gradually adapts to the local culture and customs, it will lead to lower loneliness. Meanwhile, acculturation will also result in a good family atmosphere and better family support, and finally, indirectly reduce the loneliness of MEFC.

This study used the short-form UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-8) to assess the loneliness of the MEFC in Jinan, China. There are a total of eight items in the ULS-8, each item can score 1–4 points (never, rarely, sometimes, always), and the total score is between 8 and 32 points. The eight items were the following: “(1) I lack companionship; (2) There is no one I can turn to; (3) I feel left out; (4) I feel isolated from others; (5) I am unhappy being so withdrawn; (6) People are around me but not with me; (7) I am an outgoing people; (8) I can find companionship when I want it.” The higher the score, the higher the degree of loneliness (35).

Four questions were used as the indicators of acculturation: “(1) understanding of local wedding customs; (2) understanding of local funeral customs; (3) understanding of local diet customs; and (4) understanding of local special food snacks.” Two levels of answers were set for each question in the current research: “1. don't understand; 2. understand.”

Family support in this study was measured by four aspects: “(1) children's support, (2) couple's support, (3) siblings' support, and (4) other family members' support.” Two levels of answers were set for each question: “1. no support or low support; 2. high support.”

A descriptive statistics, t-test, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were employed to describe and determine the statistically significant differences between demographic characteristics, acculturation, and family support by adopting the SPSS 26.0. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The structural equation model (SEM) was used to explore the relationship between acculturation, family support, and loneliness among the MEFC in Jinan, China. In this study, maximum likelihood estimation was used to estimate the best fitting model. The SEM consisted of endogenous and exogenous variables, the former being loneliness and the latter being acculturation and family support. The AMOS (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) statistical software package for Windows was conducted to run the SEM in order to obtain the maximum likelihood estimation of model parameters and to calculate the model fitness index. Finally, we performed bootstrap tests (the sampling process was repeated 1,000 times) to examine the total, indirect, and direct effects of the model. The indirect effect was regarded as statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) excluded zero (36).

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the MEFC in this study. A total of 656 MEFC were included in the data analysis, with a mean age of 66.19 ± 4.53 years old. Among them, 30.1% were 63–65 years old. The average score of ULS-6 among the MEFC was 12.82 ± 4.05 in this study. For the sociodemographic information, most of the MEFC were female (63.7%), had a rural Hukou (87.5%), were currently married (88.9%), were unemployed (74.4%), and had a monthly income of 0–1,000 (64.3%). Concerning education, 18.9% of the MEFC had received a high school education or above. Statistically significant differences between education level and loneliness were found among the MEFC in this study.

Table 2 shows the acculturation, family support, and loneliness of the MEFC. In terms of acculturation, the percentage of the MEFC who knew about the wedding customs, funeral customs, diet customs, and special food snacks of the inflow city was 42.4, 40.1, 51.1, and 46.5%, respectively. Concerning family support, most of the MEFC were able to obtain high support from their children (89.5%) and spouse (83.5%), while the percentage of support from siblings and other family members was 53.8 and 36.4%, respectively. Statistically significant differences were observed between loneliness and the four variables of assessing acculturation (wedding customs, funeral customs, diet customs, and special food snacks) separately in this study. Meanwhile, statistically significant differences between loneliness and the three variables of measuring family support (children support, sibling support, and other family support) were also found among the MEFC in the current study.

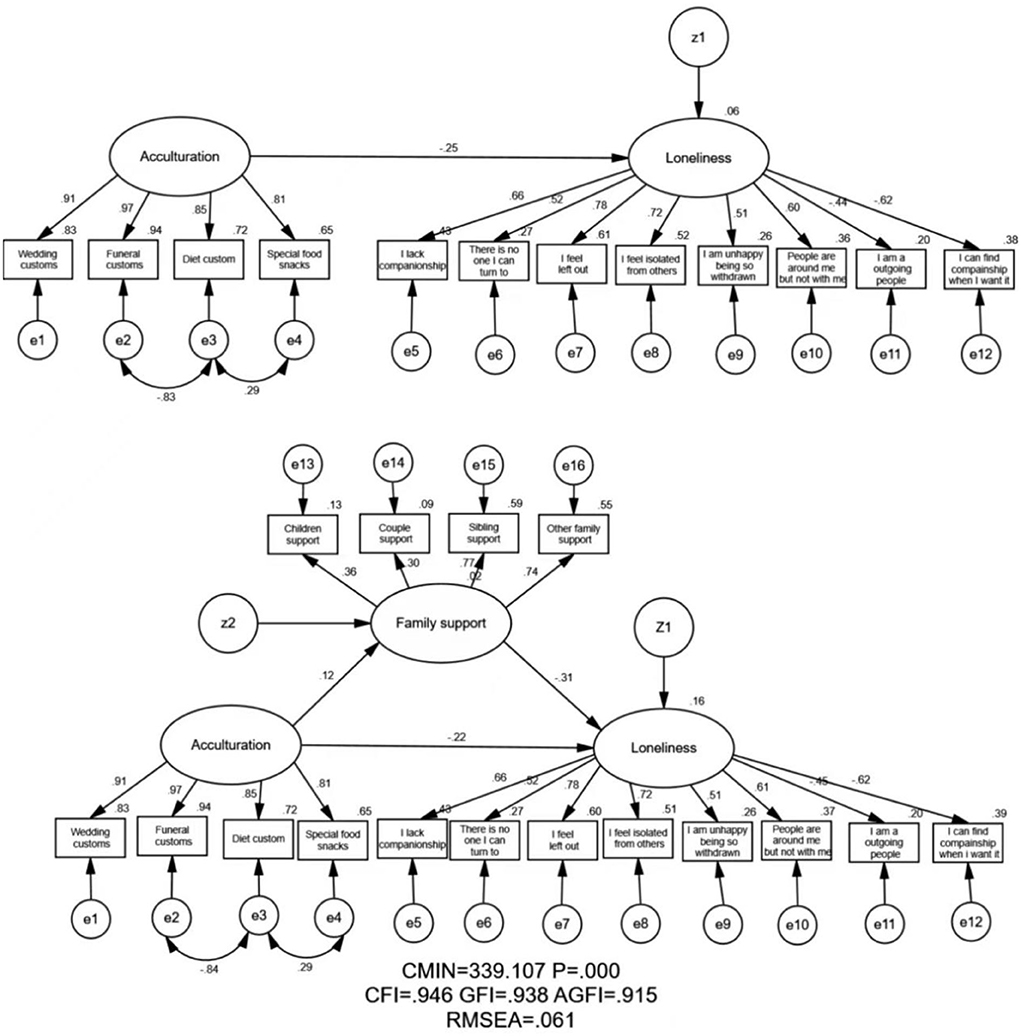

Table 3 displays the value of the model fit indicators of this study. As shown, the information of the model fitness indices was: CFI = 0.946 > 0.90; GFI = 0.938 > 0.90; AGFI = 0.915 > 0.90; RMSEA = 0.061 < 0.080. The chi-square value of the overall model was p < 0.001. All of the model fitness indices values indicated that the hypotheses model fits the empirical data very well in this study.

The relationship between acculturation, family support, and loneliness of the MEFC is shown in Figure 1. In detail, there are two figures in Figure 1: the upper figure shows the relationship between acculturation and loneliness, while the lower figure illustrates the mediating effect of family support on the association between acculturation and loneliness. In addition, the SEM could be used not only to analyze empirical relationships between different variables in the model but also to analyze statistical associations between observed and unobserved variables simultaneously. In this study, there were three unobserved variables: acculturation, family support, and loneliness. Among them, acculturation and family support were both represented by four observation variables, and loneliness was represented by eight observation variables.

Figure 1. Path diagram of the association between acculturation and loneliness with family support as a mediator (n = 656). Employing the cross-sectional data, the relationship between acculturation and family support, and loneliness was analyzed. Arrows indicate the associations and directions between variables, and double curved arrows indicate the correlation between each factor. All parameter estimates were statistically significant (p < 0.001); χ2 = Chi-square; GFI, Goodness of Fit Index; AGFI, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index; CFI, Comparative Fitness Index; RMSEA, Root-mean Square Error of Approximation; MEFC, migrant elderly following children.

As illustrated in Figure 1 (upper figure), acculturation exerted a negative effect on loneliness (the standardized effect = −0.25, p < 0.01). Moreover, as shown in Figure 1 (lower figure), acculturation exerted a negative effect on loneliness (the standardized effect = −0.22, p < 0.01), family support also exerted a negative effect on loneliness (the standardized effect = −0.31, p < 0.01), and acculturation exerted a positive effect on family support (the standardized effect = 0.12, p < 0.05).

Figure 1 also illustrated the mediation pathway model. The path coefficients showed that the total effect of acculturation on loneliness was −0.25 (upper figure in Figure 1). After adding family support (lower figure in Figure 1), the direct effect of acculturation on loneliness was −0.22.

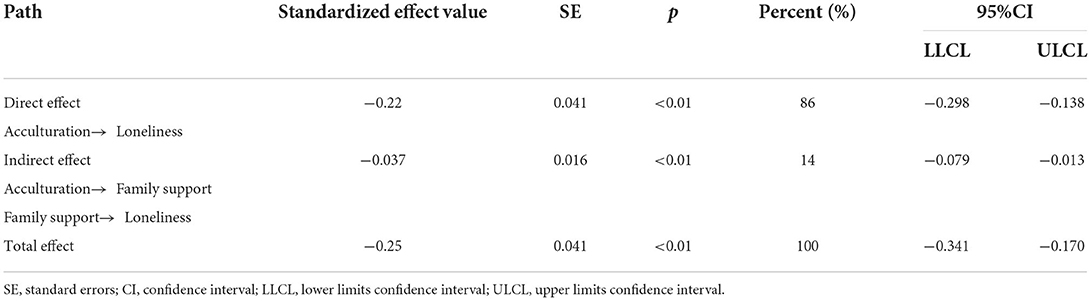

Table 4 shows the standardized total effect, direct effect, indirect effects, as well as the results of the mediating effect. Specifically, the standardized indirect effect coefficient of acculturation on loneliness through family support was −0.037, with a mediating effect of 14% [14% = 0.12 × (−0.31)/0.12 × (−0.31) +(−0.22)]. The bootstrap test suggested that the direct mediating effect via family support was −0.037 (95%CI: −0.079 to −0.013, p < 0.001). These effects were significant since the 95%CI excluded zero. Therefore, the association between acculturation and loneliness was achieved partly through family support.

Table 4. The standardized total, direct, and indirect effects of acculturation on loneliness with family support as mediators (N = 656).

Employing the SEM, this study investigated the relationship between loneliness, acculturation, and family support among the MEFC in Jinan, China. The results revealed that the loneliness of the MEFC was associated with their acculturation, while family support mediated the relationship between acculturation and loneliness.

The mean score of loneliness among the MEFC in this study was 12.82 ± 4.05, indicating that they had a low level of loneliness. This result is lower than a study of Italian elderly people (13.1 ± 6.9) (37), which might be because most of the MEFC come to the inflow city to take care of their children, so their bodies are relatively healthy, while physical frailty and disability are an important cause of loneliness (38). In addition, the loneliness level of this study was also lower compared to a Nigerian study of retired elderly people (20.31 ± 3.59) (39). It might be because most Nigerian elderly people are not accompanied by their children after retirement (40), and although most of the MEFC did not have a job, they were accompanied by their family members, so they had a lower level of loneliness. However, in a study on the elderly in rural China (11.09 ± 4.59) (41), it was found to have a lower level of loneliness than this study. The possible explanation for this difference was the MEFC were not used to the inflow cities and felt unfamiliar or the differences in socioeconomic status among sample cities.

A negative relationship between acculturation and loneliness was found among the MEFC in this study, that is, the better the acculturation, the lower the loneliness. The negative effect of acculturation on loneliness in our study was similar to that in the study conducted among older immigrants in Sweden, where it was also found that the migrant elderly were not able to adapt to the culture which could lead to feelings of alienation and non-belonging that triggered experiences of loneliness (42). In previous studies, the immigrants who were able to share a similar language and culture had lower levels of loneliness, while those who did not had higher levels of loneliness (43). The relationship between acculturation and loneliness could also be partially explained by the concept of cultural belonging (44). Although it might be a resource for migrants experiencing two different cultures during their migration, there are also inner conflicts in migrants' sense of belonging. Therefore, in terms of cultural belonging, if cultural attachment and inclusion between two cultures could prevent loneliness, then acculturation stress and cultural conflict could also increase the loneliness of migrants (45). Specifically, for the MEFC in this study, most of them came from rural areas and migrated to cities following their children. The big differences between their hometown and inflow city might cause cultural conflicts for them, and further result in increased loneliness.

The relationship between loneliness and family support in the MEFC was negative in this study, which was consistent with previous research that found that the level of family function and social support were important factors affecting the loneliness of the elderly (46, 47). Family relationship was an important part of the social network, and children were important sources of companionship, intimacy, and sharing (48). Spouse's company was also an important factor in reducing loneliness among older adults (49). In addition, sibling support could ease the loneliness of older adults (50). It is well-known that Asian populations are characterized by collectivism compared to the individualism of the West (51). Studies have shown that the loneliness of collectivist societies is higher than that of individual socialist societies (52) because the core of collectivism is interdependence which emphasizes the relationship between individuals (53). Srinivasan's research found that strong relationships were the norm in rural areas in India, while a lack of such social connections was akin to a departure from cultural norms and could be seen as painful which finally led to an increase in loneliness (54). In a study on Chinese American older adults, a supportive network was observed to reduce the effects of adverse stressors and to improve mental health outcomes (32). Regarding the MEFC in the current study, their support from family members might help them to face unfamiliar environments, integrate into the inflow city, and reduce their loneliness.

A positive relationship between acculturation and family support was observed in this study, implying that the improvement of acculturation would lead to higher levels of family support. This result was consistent with a study on Mexican Americans which also found that those who approved more of Mexican culture and customs would enjoy a higher level of family support (55). Moreover, it was found that second-generation Mexican Americans were more likely to have large family networks and receive family support than first-generation Mexican American women (56). However, a study on Latino-American adolescent boys showed that higher acculturation could lead to family conflicts. This might be due to the fact that the teenagers could more easily and actively integrate into the local culture and environment, while their parents would generally follow the original cultural values and customs. This gap in the acculturation of children and parents might lead to their differences in cultural values, and further cause conflicts among family members (57). For the MEFC, when they have better acculturation, they might become more cheerful, be more willing to communicate with their family members, and be more likely to have a higher level of family support.

This study found that the family support of the MEFC played a mediating role between acculturation and loneliness, and the mediating effect accounted for 14% of the total effect. This was similar to a previous study among Latino adults, which also found that family support had a mediating effect between acculturation and mental health (58). The reason may come from the fact that social support could reduce the stress caused by unfamiliar cultural environments during the intercultural transition of migrants and could further promote their physical and mental health (59). In detail, as an important resource for immigrants (60), social support has been shown to be associated with acculturation (61) and is helpful for the maintenance of the mental health of immigrants (62). Therefore, family support became a mediator between acculturation and loneliness. Compared with the young people who need to develop their careers in the inflow city, the MEFC might not have an urgent need to expand their network and comprehensively adapt to the local culture, since their main job is to take good care of their grandchildren. Moreover, taking care of their grandchildren consumed most of their time and energy, which also caused them to have limited time and energy for purposely enlarging their network and caring for their own health conditions. All of these factors made the MEFC more reliant on family support for adapting to life in the inflow city. In this sense, as a mediating variable, family support played an important role between acculturation and loneliness for the MEFC.

The following policy recommendations are provided based on the results of this study: First, the community could arrange certain programs and activities to help the MEFC to learn the culture of the inflow city, to better adapt to local life, and to enhance their sense of belonging. Second, the family members of the MEFC should pay attention to the mental health of the MEFC, provide them with a good living environment, and create a good family atmosphere. Third, community health centers are encouraged to pay attention to the mental health of the MEFC and conduct psychological counseling and health education.

This study has the following limitations: First, cross-sectional data was used and so causality cannot be predicted (such as the association between acculturation and family support). Second, due to the lack of systematic scales of family support and cultural adaptation in the questionnaire, we only selected certain relevant indicators for evaluation, which are expected to be improved in follow-up research. Third, multi-stage cluster sampling was employed to select the participants, yet the survey weights were not applied and calculated. Fourth, more confounding variable effects (such as duration of migration) on the loneliness of MEFC are needed to be examined in future studies. Finally, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this study only selected the MEFC in Jinan as the research subjects as more surveys in other cities in China could not be conducted. This means that the results cannot represent more MEFC populations in China.

The average ULS-8 score of 12.82±4.05 indicated a low level of loneliness among the MEFC in Jinan, China. Acculturation was found to be associated with loneliness, while family support was observed to play a partial mediating role between acculturation and family support among the MEFC in Jinan. Policy implications were provided to decrease loneliness and improve the mental health status of the MEFC based on the findings of this study.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

DZ analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. ZL and XS participated in the questionnaire survey and data processing. YS gave many valuable suggestions in response to the reviewer's comments. FK applied for funds to support this study, designed the study, completed the questionnaire design, supervised and participated in the data collection, instructed the writing, statistical analysis, data processing, and provided comments on the modification of the manuscript. SL gave many valuable comments on the draft and also polished it. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the final manuscript.

This study was supported and funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71804094), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2016M592161), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2016GB02), the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. 201603021), and the Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University (Nos. 2015HW002 and 2018JC055).

The research team greatly appreciates the funding support and the research participants for their cooperation and support.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

MEFC, Migrant elderly following children; ULS-8, the short-form UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-8) the short-form UCLA Loneliness Scale; SEM, structural equation model; χ2, Chi-square; GFI, Goodness of Fit Index; AGFI, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index; CFI, Comparative Fitness Index; RMSEA, Root-mean Square Error of Approximation; SE, standard errors; CI, confidence interval; LLCL, lower limits confidence interval; ULCL, upper limits confidence interval.

1. Beier Z, Mingzhu Y, Xuewen Q, Xin S. Review of social adaptation research of migrant elderly. Legal Syst Soc. (2020) 8:128–30. doi: 10.19387/j.cnki.1009-0592.2020.03.179

2. Jinan Bureau of Statistics. Announcement of the Seventh Census of Jinan. (2021). Available online at: http://jntj.jinan.gov.cn/art/2021/6/16/art_18254_4742896.html (accessed May 21, 2022).

3. National Health Commission (NHC). Report on China's Migrant Population Development in 2018(2018). Available online at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/xwdt/201812/a32a43b225a740c4bff8f2168b0e9688.shtml (accessed April 19, 2022).

4. Fanlei K, Mei K, Cheng L, Shixue L, Jun L, Research Research progress of the migrant elderly following children. Chin J Gerontol. (2020) 40:2443–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2020.11.059

5. Chunlei Ji, Chang M. Study on the relationship between loneliness and social support of urban migrant elderly. J Campus Life Mental Health. (2020) 18: 58–60. doi: 10.19521/j.cnki.1673-1662.2020.01.018

6. West DA, Kellner R, Moore-West M. The effects of loneliness: a review of the literature. Compr Psychiatry. (1986) 27:351–63. doi: 10.1016/0010-440X(86)90011-8

7. Peplau L, Perlman D. Perspectives on loneliness “being old and living alone”. In: Peplau LA, Perlman D, editors. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy. New York, NY: John Wiley (1982). p. 327–47. doi: 10.1093/geronj/38.4.492

8. Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. (2010) 40:218–27. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

9. Wolf TM, Scurria PL, Webster MG. A four-year study of anxiety, depression, loneliness, social support, and perceived mistreatment in medical students. J Health Psychol. (1998) 3:125–36. doi: 10.1177/135910539800300110

10. Weiwei T, Yue W, Yulin Z, Qianqian Y, Bo Z, Jie W, et al. The effects of self-acceptance and loneliness on the social adaptability of the migrant elderly. Chin Nurs Manag. (2018) 18:1051–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2018.08.010

11. Tam S, Neysmith S. Disrespect and isolation: elder abuse in Chinese communities. Can J Aging. (2006) 25:141–51. doi: 10.1353/cja.2006.0043

12. Wu Z, Penning M. Immigration and loneliness in later life. Ageing Soc. (2013) 35:64–95. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X13000470

13. Redfield R, Linton R, Herskovits MJ. Memorandum for the study of acculturation. Am Anthropol. (1936) 38:149–52. doi: 10.1525/aa.1936.38.1.02a00330

14. Shangxin C. Effects of cultural adaptation on physical and mental health of migrant elderly. Chin J Popul Sci. (2021) 3:112–25.

15. Lin Y, Kingminghae W. Social support and loneliness of Chinese international students in Thailand. J Popul Soc Stud. (2014) 22:141–57. doi: 10.14456/jpss.2014.10

16. Garcia DL, Savundranayagam MY, Kloseck M, Fitzsimmons D. The role of cultural and family values on social connectedness and loneliness among ethnic minority elders. Clin Gerontol. (2019) 42:114–26. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2017.1395377

17. Park HJ, Morgan T, Wiles J, Gott M. Lonely ageing in a foreign land: social isolation and loneliness among older Asian migrants in New Zealand. Health Soc Care Community. (2019) 27:740–7. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12690

18. Kuo B, Huang S, Li X, Lin D. Self-esteem, resilience, social support, and acculturative stress as predictors of loneliness in chinese internal migrant children: a model-testing longitudinal study. J Psychol. (2021) 155:387–405. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2021.1891854

19. Chen Y, Hicks A, While AE, Loneliness Loneliness and social support of older people in China: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Care Community. (2014) 22:113–23. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12051

20. Wenbo B. The problems and countermeasures of the social adaptation of the elderly migrant. Trop Agric Eng. (2021) 45:60–3.

21. Yuzhen L, Siqi A, Qiong S. Correlation between loneliness and family social support of advanced—age disabled elderly in Tangshan city. Nurs Res. (2018) 32:7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6493.2018.07.016

22. Huahong L, Junyan C, Zhang J, Chen Y, Chen W, Xuenan C. The influence of family support system on the loneliness of the elderly—taking Shanghai as an example. Health Nutr China. (2020) 30:5–7.

23. Wang G, Zhang X, Wang K, Li Y, Shen Q, Ge X, et al. Loneliness among the rural older people in Anhui, China: prevalence and associated factors. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2011) 26:1162–8. doi: 10.1002/gps.2656

24. Teh JK, Tey NP, Ng ST. Family support and loneliness among older persons in multiethnic Malaysia. Sci World J. (2014) 2014:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2014/654382

25. Pehlivan S, Ovayolu O, Ovayolu N, Sevinc A, Camci C. Relationship between hopelessness, loneliness, and perceived social support from family in Turkish patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. (2012) 20:733–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1137-5

26. Jewell SL, Letham-Hamlett K, Hanna IM, Luecken LJ, MacKinnon DP. Family support and family negativity as mediators of the relation between acculturation and postpartum weight in low-income mexican-origin women. Ann Behav Med. (2017) 51:856–67. doi: 10.1007/s12160-017-9909-x

27. Wang K, Zhang A, Sun F, Hu RX. Self-rated health among older chinese americans: the roles of acculturation and family cohesion. J Appl Gerontol. (2021) 40:387–94. doi: 10.1177/0733464819898316

28. Almeida J, Molnar BE, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: testing the concept of familism. Soc Sci Med. (2009) 68:1852–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.029

29. Perez-Brena NJ, Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Youths' imitation and de-identification from parents: a process associated with parent-youth cultural incongruence in Mexican-American families. J Youth Adolesc. (2014) 43:2028–40. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0101-3

30. N, Eres R, Postolovski Thielking M, Lim MH. Loneliness, mental health, and social health indicators in LGBTQIA+ Australians. Am J Orthopsychiatry. (2021) 91:358–66. doi: 10.1037/ort0000531

31. Oppedal B, Røysamb E, Sam DL. The effect of acculturation and social support on change in mental health among young immigrants. Int J Behav Dev. (2004) 28:481–94. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000126

32. Sun F, Gao X, Gao S, Li Q, Hodge DR. Depressive symptoms among older chinese americans: examining the role of acculturation and family dynamics. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2018) 73:870–9. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw038

33. Administrative division of Jinan City. Available online at: http://www.jinan.gov.cn/col/col129/index.html (accessed April 12, 2022).

34. Oberg K. Cultural shock: adjustment to new cultural environments. Pract Anthropol. (1960) 7:177–82. doi: 10.1177/009182966000700405

35. Hays RD, DiMatteo MR. A short-form measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess. (1987) 51:69–81. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6

36. Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. (2002) 7:422–45. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

37. Mulasso A, Roppolo M, Giannotta F, Rabaglietti E. Associations of frailty and psychosocial factors with autonomy in daily activities: a cross-sectional study in Italian community-dwelling older adults. Clin Interv Aging. (2016) 11: 37–45. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S95162

38. Langlois F, Vu TT, Kergoat MJ, Chassé K, Dupuis G, Bherer L. The multiple dimensions of frailty: physical capacity, cognition, and quality of life. Int Psychogeriatr. (2012) 24:1429–36. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000634

39. Igbokwe CC, Ejeh VJ, Agbaje OS, Umoke P, Iweama CN, Ozoemena EL. Prevalence of loneliness and association with depressive and anxiety symptoms among retirees in Northcentral Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. (2020) 20:153–76. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01561-4

40. Ojembe BU, Ebe KM. Describing reasons for loneliness among older people in Nigeria. J Gerontol Soc Work. (2018) 61:640–58. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2018.1487495

41. Hongjuan L, Yan Z, Yuanyuan C, Jianmei P, Hongsheng L. The effect of psychological stress on life satisfaction among the elderly in rural areas—the mediating role of loneliness. Chin J Gerontol. (2020) 40:4216–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2020.19.056

42. Olofsson J, Rämgård M, Sjögren-Forss K, Bramhagen AC. Older migrants' experience of existential loneliness. Nurs Ethics. (2021) 28:1183–93. doi: 10.1177/0969733021994167

43. De Jong GJ, Van der Pas S, Keating N. Loneliness of older immigrant groups in Canada: effects of ethnic-cultural background. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2015) 30:251–68. doi: 10.1007/s10823-015-9265-x

44. Barros S, Albert I. Living in-between or within? Cultural identity profiles of second-generation young adults with immigrant background. Int J Theory Res. (2020) 20:290–305. doi: 10.1080/15283488.2020.1832491

45. Albert I. Perceived loneliness and the role of cultural and intergenerational belonging: the case of Portuguese first-generation immigrants in Luxembourg. Eur J Ageing. (2021) 18:299–316. doi: 10.1007/s10433-021-00617-7

46. Liang L. Study on the relationship between loneliness, parent-child support and filial piety expectation in the elderly (dissertation/master's thesis) (2009). Changsha: Central South University.

47. Jie W. The relationship between social support, loneliness and subjective well-being of the elderly. Psychol Sci. (2008) 31:984–6. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2008.04.059

48. Dykstra PA. The differential availability of relationships and the provision and effectiveness of support to older adults. J Soc Pers Relat. (1993) 10:355–70. doi: 10.1177/0265407593103004

49. Shi-guo B, Nian X, Yun JI, Mediating Mediating effect of loneliness on relationship between social support and quality of life in the elderly. Chinese health education (2019) 35:161–165.

50. Voorpostel M, Van Der Lippe T. Support Between Siblings And Between Friends: Two Worlds Apart? J Marriage Family. (2007) 69:1271–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00446.x

51. North MS, Fiske ST. Modern attitudes toward older adults in the aging world: a cross-cultural meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. (2015) 141:993–1021. doi: 10.1037/a0039469

52. Lykes VA, Kemmelmeier M. What predicts loneliness? Cultural difference between individualistic and collectivistic societies in Europe. J Cross Cult Psychol. (2013) 45:468–90. doi: 10.1177/0022022113509881

53. Markus H, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. (1991) 98:224–53. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

54. Chokkanathan S. Prevalence of and risk factors for loneliness in rural older adults. Australas J Ageing. (2020) 39:545–51. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12835

55. Rodriguez N, Mira CB, Paez ND, Myers HF, Exploring Exploring the complexities of familism and acculturation: central constructs for people of Mexican origin. Am J Community Psychol (2007) 39:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9090-7

56. Zambrana RE, Silva-Palacios V, Powell DR. Parenting concerns, family support systems, and life problems in Mexica origin women: a comparison by nativity. J Community Psychol. (1992) 20:276–88. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(199210)20:4<276::AID-JCOP2290200403>3.0.CO;2-8

57. Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: longitudinal relations. J Community Psychol. (2000) 28:443–8. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(200007)28:4<443::AID-JCOP6>3.0.CO;2-A

58. Rivera FI. Contextualizing the experience of young Latino adults: acculturation, social support and depression. J Immigr Minor Health. (2007) 9:237–44. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9034-6

59. Adelman MB. Cross-cultural adjustment: a theoretical perspective on social support. Int J Intercult Rel. (1988) 12:183–204. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(88)90015-6

60. Noh S, Avison WR. Asian immigrants and the stress process: a study of Koreans in Canada. J Health Soc Behav. (1996) 37:192–206. doi: 10.2307/2137273

61. Birman D, Trickett EJ. Cultural transitions in first-generation immigrants: acculturation of Soviet Jewish refugee adolescents and parents. J Cross Cult Psychol. (2001) 32:456–77. doi: 10.1177/0022022101032004006

Keywords: loneliness, acculturation, family support, migrant elderly following children, mediating effect

Citation: Zong D, Lu Z, Shi X, Shan Y, Li S and Kong F (2022) Mediating effect of family support on the relationship between acculturation and loneliness among the migrant elderly following children in Jinan, China. Front. Public Health 10:934237. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.934237

Received: 02 May 2022; Accepted: 01 July 2022;

Published: 17 August 2022.

Edited by:

Chi Kin Law, The University of Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Daniel Ludecke, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, GermanyCopyright © 2022 Zong, Lu, Shi, Shan, Li and Kong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shixue Li, c2hpeHVlbGlAc2R1LmVkdS5jbg==; Fanlei Kong, a29uZ2ZhbmxlaUBzZHUuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.