94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 11 July 2022

Sec. Infectious Diseases – Surveillance, Prevention and Treatment

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.914943

This article is part of the Research TopicImproving Immunization Programmes Uptake and Addressing Vaccine HesitancyView all 17 articles

Mohammed Noushad1*

Mohammed Noushad1* Mohammad Zakaria Nassani1

Mohammad Zakaria Nassani1 Mohammed Sadeg Al-Awar2,3

Mohammed Sadeg Al-Awar2,3 Inas Shakeeb Al-Saqqaf4

Inas Shakeeb Al-Saqqaf4 Sami Osman Abuzied Mohammed5

Sami Osman Abuzied Mohammed5 Abdulaziz Samran1

Abdulaziz Samran1 Ali Ango Yaroko6

Ali Ango Yaroko6 Ali Barakat1

Ali Barakat1 Omar Salad Elmi7

Omar Salad Elmi7 Anas B. Alsalhani8

Anas B. Alsalhani8 Yousef Fouad Talic1

Yousef Fouad Talic1 Samer Rastam9

Samer Rastam9Objectives: Preventing severe disease and acquiring population immunity to COVID-19 requires global immunization coverage through mass vaccination. While high-income countries are battling vaccine hesitancy, low-income and fragile nations are facing the double dilemma of vaccine hesitancy and lack of access to vaccines. There is inadequate information on any correlation between vaccine hesitancy and access to vaccines. Our study in a low-income nation aimed to fill this gap.

Methods: In the backdrop of a severe shortage of COVID-19 vaccines in Yemen, a low-income fragile nation, we conducted a nation-wide cross-sectional survey among its healthcare workers (HCWs), between 6 July and 10 August 2021. We evaluated factors influencing agreement to accept a COVID-19 vaccine and any potential correlation between vaccine acceptance and lack of access to vaccines.

Results: Overall, 61.7% (n = 975) of the 1,581 HCWs agreed to accept a COVID-19 vaccine. Only 45.4% of the participants agreed to have access to a COVID-19 vaccine, with no sex dependent variations. Although several determinants of vaccine acceptance were identified, including, having a systemic disease, following the updates about COVID-19 vaccines, complying with preventive guidelines, having greater anxiety about contracting COVID-19, previous infection with COVID-19, believing COVID-19 to be a severe disease, and lower concern about the side effects of COVID-19, the strongest was access to vaccines (OR: 3.18; 95% CI: 2.5–4.03; p-value: 0.001).

Conclusion: The immediate and more dangerous threat in Yemen toward achieving population immunity is the severe shortage and lack of access to vaccines, rather than vaccine hesitancy, meaning, improving access to vaccines could lead to greater acceptance.

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been a global public health threat for more than 2 years, causing more than 516 million infections and 6.25 million deaths (1). There are also suggestions that globally, at least half of the COVID-19 deaths have been thought to be missed. For example, it has been suggested that the percentage of deaths from COVID-19 reported in the United States is just 78%, and in a highly populated country like India, it is only 10% indicating a public health burden greater than reported (2). This is especially true in resource-poor and conflict countries where intentional or unintentional largescale mortality underreporting, shortages in testing capacity and availability of health care workers (HCWs) are major concerns (3). So far, the World Health Organization (WHO) has identified more than thirteen variants of the SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19, and it is expected to mutate further, unless global population immunity is successfully achieved (4). Currently, the favored pathway to reach that goal is through successful global vaccination programs.

Although several countries are still facing recurrent waves of the virus transmission, the implementation of robust vaccination programs have been instrumental in limiting morbidity and mortality from COVID-19. However, the optimum immunization coverage necessary to reach global population immunity can be achieved only by regulated and inclusive vaccine distribution covering all countries regardless of country income index.

Since healthcare workers (HCWs) work in the frontline in the fight against COVID-19, they are one of the most vulnerable. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 80,000 to 180 000 health and care workers could have died from COVID-19 between January 2020 and May 2021 (5). Due to their vulnerability, and to prevent a potential breakdown of the healthcare system, globally they have been prioritized to receive vaccination against COVID-19. Thanks to the implementation of coordinated vaccination programs, as of September 2021, more than 80% of the HCWs in 22 mostly high-income countries (HIC) have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19 (5). Unfortunately, these figures are overshadowed by considerable differences across regions and economic groups. For example, as of November 2021, only 27% of HCWs in the African continent have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19, a result of extreme vaccine inequity (6).

While several HICs are battling vaccine hesitancy in pursuit to achieve maximum vaccine coverage, it is vaccine inequity that has crippled low-income countries (LIC). Even after a year since the approval of several vaccines against COVID-19, LICs are still struggling with extreme shortage in vaccine supply, enough to fully vaccinate only a fraction of their populations, while HICs have fully vaccinated more than 73% of their populations (7). Numerous studies have been conducted worldwide on vaccine hesitancy/acceptance among HCWs and the general population. However, there is inadequate information on the correlation between vaccine hesitancy/acceptance and access to vaccines. In the backdrop of a severe vaccine shortage in Yemen, we conducted an exploratory cross-sectional study among HCWs in Yemen, a low-income conflict nation, to identify predictors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and any potential correlation with lack of access to vaccines.

This study is part of a large project on global COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Therefore, the methodology and the questionnaire followed is similar across all the studies (8). A cross-sectional self-administered survey was conducted among HCWs in Yemen between 6 July and 10 August 2021. The “Report of the SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy” was used as a guide in preparing the questionnaire (9). As part of the validation of the study, a pilot study was initially carried out on 10 participants, after which expert opinions were taken from specialists in the field. The survey questionnaire, developed on Google Forms, was distributed by dual mode (online and paper based) to prospective participants. The questionnaire required <5 min to complete. Participation was voluntary and the participants provided informed consent on the survey platform before proceeding to the survey items. Participants were not asked to disclose their names or email addresses, and their anonymity was guaranteed during the data collection process. The survey form was designed in such a way that only complete forms would qualify for submission.

This study was approved by the Research Committee of College of Dentistry, Dar Al Uloom University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (COD/IRB/2020/2).

The sample size was calculated using Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health–OpenEpi (http://www.openepi.com/Menu/OE_Menu.htm, accessed on 25 June 2021). We used 50% as the 'hypothesized percentage frequency of the outcome factor (vaccine acceptance) in the population, which is recommended for an unknown frequency, and 4% as the absolute precision. The resultant sample size for 99% confidence interval using these parameters was 1,036.

Participants were recruited using convenience sampling. Participants included HCWs from all governorates of Yemen. Participants below the age of 18 years were not included in the study. Participants were not paid compensation for participation in the study.

General attitudes toward vaccines were measured using a 2-item scale and participants' attitudes toward the health authorities were measured using a 4-item scale. Participants were then asked if they had access to COVID-19 vaccines. Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 “strongly agree” to 5 “strongly disagree” (8).

This was measured using a 7-item scale. Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 “strongly agree” to 5 “strongly disagree” (8).

Socio-demographic factors included age group, sex, nationality, place of work and region. Participants' reports on chronic medical conditions (e.g., asthma, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and/or cancer) were used to indicate the presence or absence of pre-existing co-morbidity. Other variables included participants' self-updating on COVID-19 vaccine development, prior infection with COVID-19, perception of COVID-19 severity, compliance with government COVID-19 guidelines, and anxiety toward contracting COVID-19.

Descriptive statistics were expressed as percentages and numbers for each item/survey question. The main outcome of this study was the agreement to accept a COVID-19 vaccine and potential correlation with access to vaccines. The current study considered any participant to have an intention to vaccinate if he/she agreed or strongly agreed on the item “I will get vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine,” or if they had already taken the vaccine. Bivariate statistical analysis of the relationship between the main outcome “agreement to accept a COVID-19 vaccine” and demographic and other parameters was performed using the Chi-squared test for trend for ordinal factors, and the Chi-squared test for categorical variables. A multivariate binary logistic regression model was used to determine the predictors for intention to vaccinate. The following factors were examined as potential predictors for “intention to vaccinate:” age group, sex, nationality, presence of any medical condition, following updates on the development of vaccines against COVID-19, opinion about the severity of COVID-19, compliance with COVID-19 preventive guidelines, and anxiety about contracting COVID-19, previous COVID-19 infection, concerns about side effects of COVID-19 vaccines and access to COVID-19 vaccines. We chose possible covariates based on biological plausibility, and all factors that showed significant results in the bivariate analysis. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp).

Overall, 1,581 HCWs completed the survey questionnaire (response rate 73%). Of the participants, 61.7% (n = 975) expressed their agreement to get vaccinated against COVID-19. Males (54.1%) and females (45.9%) were equally distributed. The majority of the participants were from the 19–29 years age group (62.4%) and from the Azal province (52.6%). The majority of the participants had no comorbidities (81.8%). Characteristics and demographics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Data regarding participants' awareness about COVID-19 are presented in Table 2. It can be noted that more than a quarter of the participants (27.6%) were previously infected with COVID-19, while only 10.9% got vaccinated against COVID-19. At least 74.3% of the participants agreed that COVID-19 is a threat to public health in Yemen, and 81.8% have been updating themselves on the development of COVID-19 vaccines. Less than a half of the participants (39%) rated COVID-19 as a severe disease. Just 7.1% expressed their poor compliance with COVID-19 preventive guidelines, and only 12.7% agreed that they were highly anxious about contracting COVID-19 (Table 2).

67.4% of the participants agreed that vaccines against COVID-19 are important to overcome the pandemic, 69.1% were concerned about their side effects and 44.1% thought that the vaccines have been produced in a hurry without following guidelines. 69.8% of the participants agreed that it was important for them to get vaccinated in order to protect those with weaker immune systems, and almost half of them (44.8%) were prepared to delay getting vaccinated for those who deserved it more than them. 68.4% of the participants agreed to pay to get vaccinated. In terms of pandemic management and organization of vaccination campaigns by the health authorities, 45.9 and 42.8% expressed their satisfaction, respectively. Similarly, less than half the participants expressed their satisfaction with the support provided by non-governmental organizations (NGO) (48.6%) and the international community (48.1%). Support for a mandatory vaccination program against COVID-19 was expressed by just 41.5% of the participants. 45.4% of the participants agreed that they have access to a COVID-19 vaccine. The abovementioned results are summarized in Table 3.

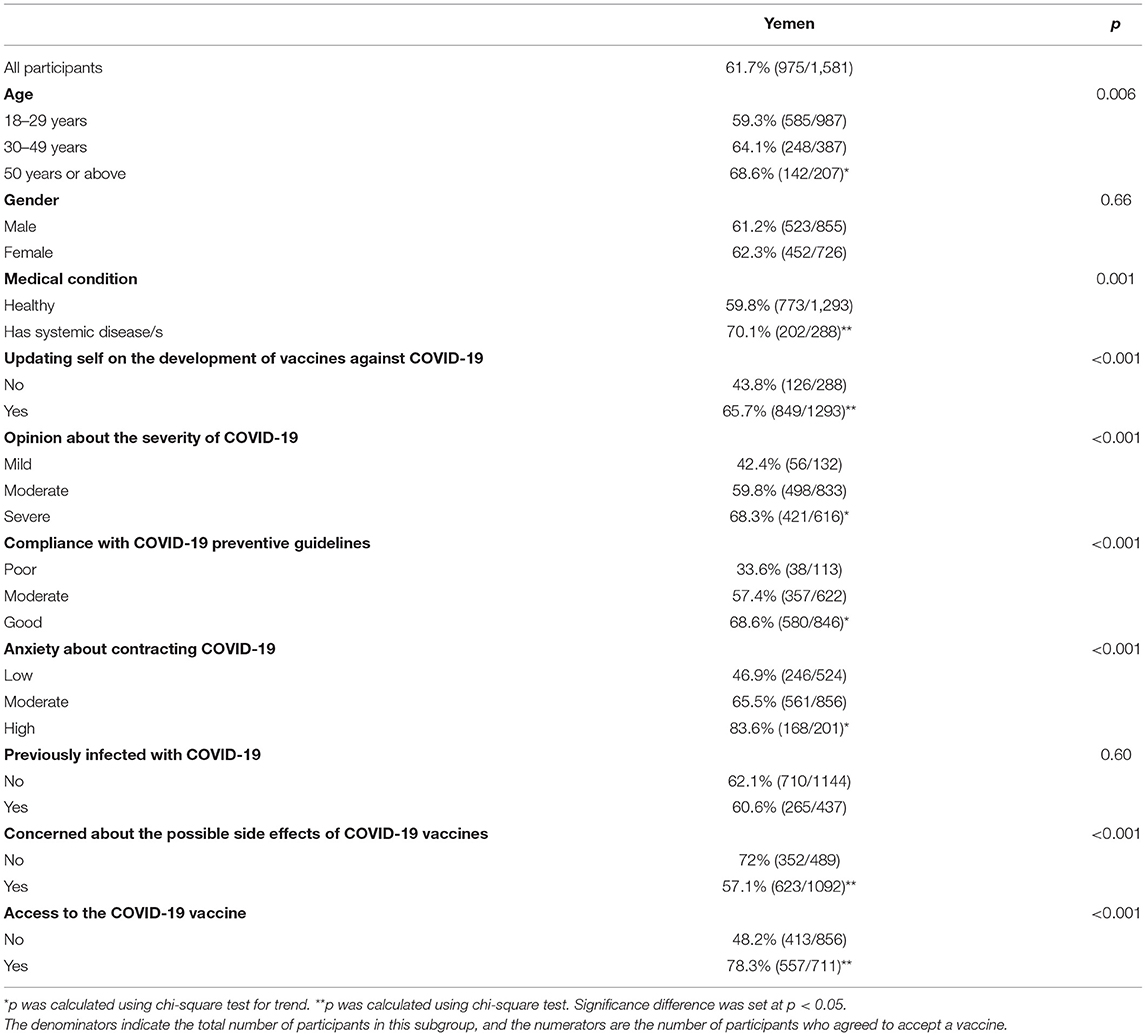

The bivariate statistical analysis indicated a possible association between participants' intention to vaccinate and eight factors (p < 0.05; Table 4). The intention to get vaccinated increased significantly with increase in age and in those with systemic disease/s. Updating self on the development of COVID-19 vaccines, increasing severity perception about COVID-19, increasing compliance with preventive guidelines, a higher level of anxiety about contracting COVID-19, and lack of concern about the side effects of COVID-19 vaccines were all associated with a greater agreement to get vaccinated. Importantly, access to COVID-19 vaccine was significantly associated with a higher intention to get vaccinated. Details of the above results are presented in Table 4. There was no gender-based association with access to vaccines (Supplementary Table).

Table 4. Bivariate statistical analysis of the relationship between the main outcome “intention to vaccinate” and potential influential factors.

The logistic regression analysis indicated a possible association between agreement to get vaccinated against COVID-19 and six factors. These include having a systemic disease (OR: 1.49 95% CI: 1.03–2.16; p-value: 0.03), following the updates about COVID-19 vaccines (OR: 1.92; 95% CI: 1.43–2.57; p-value: 0.001), those who believed COVID-19 to be a severe disease, those who complied with preventive guidelines, those with greater anxiety about contracting COVID-19 (OR: 3.31; 95% CI: 2.08–5.25; p-value: 0.001), previous infection with COVID-19, those less concerned about the side effects of COVID-19 vaccines (OR: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.38–0.64; p-value: 0.001) and those who have access to a COVID-19 vaccine (OR: 3.18; 95% CI: 2.5–4.03; p-value: 0.001; Table 5). Of these, compliance with preventive guidelines, anxiety about contracting COVID-19, and access to a COVID-19 vaccine were showed to have the greatest association.

The success in the fight against COVID-19 rests largely on optimum immunization coverage through equitable vaccine distribution. Our study aimed to identify potential determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and any possible correlation with lack of access to vaccines, in Yemen, a low-income fragile nation. Although we did a similar study on the general population in Yemen, the current study looked for any similarities or differences with the previous study (10). Interestingly, the overall vaccine acceptance rate indicated by participants in our study (61.7%) is comparable to that indicated by HCWs in a similar study we conducted in neighboring Saudi Arabia (64.1%), a high-income country (11). It is however greater than that indicated by the general population, in the similar study we conducted in Yemen (10). Our results are comparable to other studies in HICs in the region, including one on more than 15,000 HCWs in Saudi Arabia (64.9%), one on HCWs in the United Arab Emirates (57.6%) and another one in the general population in Oman (56.8%) (12–14).

Studies in other fragile nations have indicated wide ranging results. For example, in an early multi-country study in Palestine, Syria and Jordan, it was shown that only 32.2% of the participants intended to be vaccinated against COVID-19 (15). Similarly, in two studies in Syria, the agreement to be vaccinated against COVID-19 was indicated by only about 37% of the participants (16, 17). A study in Iraq among HCWs and the general population revealed a vaccine acceptance rate similar (61.7%) to that of our study, with HCWs indicating higher acceptance rate than the general population (18). However, a study in Somalia indicated a higher acceptance rate of 76.8%, with HCWs indicating greater willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine than the general population (19). These results should encourage policymakers to leverage HCWs as a means of vaccine promotion among the general public since they have been shown to be trusted sources of information on vaccines (19, 20).

As in most countries, the burden of COVID-19 in Yemen is still unclear, the main reason being a severe shortage in testing capacity and availability of HCWs (3). Although a geospatial grave counting study in Yemen could not attribute all of the excess deaths to COVID-19, a seroprevalence study conducted in Aden in November 2020 indicates that the virus transmission is far higher than reported (21, 22). Nonetheless, the agreement of at least 74% of the participants on COVID-19 being a public health threat in Yemen, and almost 82% updating themselves on the development of vaccines against COVID-19 indicate their high level of awareness on COVID-19 and the vaccines against it. The challenge now lies in supplying enough doses to fill the gap between supply and demand.

Apart from demographic and other factors (Table 5), the strongest determinant of vaccine acceptance in our study was access to vaccines, which is similar to our study on the general population in Yemen (10). Even though access to COVID-19 vaccines was slightly higher among HCWs than the general population (39.9%), only 45.4% of the participants in the current study definitely agreed that they have access to a COVID-19 vaccine, and a mere 10.9% indicated having taken the COVID-19 vaccine (10). This is in sharp contrast to a recent study on vaccine intention among HCWs in neighboring Saudi Arabia, in which all the participants reported having been vaccinated against COVID-19 (23). Fragile nations like Yemen are faced with the double dilemma of vaccine shortage and logistic concerns related to the conflict. For example, in a study in Libya, 71.6% of the participants believed that COVID-19 vaccine distribution would be difficult, given the conflict related challenges there (24). Although access to vaccination facilities can be inconvenient to women and children, especially in low-income and fragile nations, as indicated in our study on the general population in Yemen, this variation may not be apparent among HCWs. With vaccine access rates of 45.7% in males and 45% in females, there was no sex-based differences in access to vaccines among participants in our current study. Unlike the general public, since participants in our study are HCWs who have been prioritized to receive vaccination against COVID-19, this finding is logical.

As of 13 March 2022, just 1.2% of the Yemeni population of more than 30 million have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19, while those in HICs is more than 73%. Moreover, during the same period, while the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people in HICs is 192.17, that in LICs is a mere 19.52 (7). Although Yemen was promised a supply of 1.9 million vaccine doses throughout 2021, so far it has not received even a third of that number (25). These huge discrepancies and broken promises could lead to further decay of trust in policymakers and the international community. Our results indicate a low level of trust among HCWs in Yemen on NGOs (48.6%) and the international community (48.1%). This should prompt policymakers and stakeholders to take immediate action to gain back the trust, which could indirectly lead to greater vaccine acceptance.

Our results suggest that the immediate and greater threat in Yemen toward achieving population immunity is the lack of access to vaccines, rather than vaccine hesitancy. This is in agreement with a previous similar study on the general population in Yemen, highlighting the importance of provision of access to vaccines in low-income and fragile nations (10). Moreover, apart from vaccine inequity, due to the conflict related conditions, residents of these countries, especially women and children, are faced with the additional challenge of difficulty in accessing vaccination facilities. At a time when HICs are racing to provide booster/third dose of the vaccine, consideration should be given to simultaneously accelerate vaccine supplies in low-income and fragile nations, to achieve the minimum threshold necessary to attain population immunity. In light of the emergence of new variants of the wild-type virus, achieving population immunity in LICs is not only critical to protecting their populations, but it is also in the best interest of attaining global population immunity. The WHO, other NGOs operating in Yemen and other low-income and fragile nations, the COVAX and donor nations should work determinedly and inclusively with all parties and stakeholders to ensure that no one is left behind in the pursuit to achieve optimum vaccine coverage.

Notable strengths of our study include the wide coverage of the respondents spanning over all the provinces of Yemen, representing different demographic characteristics, and the large sample size. Moreover, this is the first study on vaccine acceptance among HCWs in Yemen following vaccine rollout, and the first study to assess any potential correlation between vaccine acceptance and lack of access to vaccines among HCWs. A limitation of our study is the inclusion of only complete questionnaires, which could affect the response rate, and the high number of participants from a particular age group (18–29 years old). Another limitation of our study is the web-based administration of the survey questionnaire. Since participants in our study included only those with access to internet facilities, there is a possibility for bias. Moreover, the web-based administration could be a cause for lower motivation of the participants to complete the questionnaire. However, due to the conflict related conditions in Yemen and the COVID-19 related restrictions, this was the best mode currently available. Since the rate of vaccine acceptance of the population could change over time, especially as more vaccines become available and accessibility increases, further studies will provide added value on the evolving vaccine acceptance trend among the public in Yemen. Similar studies in other low-income and fragile nations will provide a wider and global perspective on the correlation between vaccine acceptance and access to vaccines.

Our results in Yemen, a low-income conflict country suggests vaccine acceptance comparable to those of neighboring countries. The potential correlation between vaccine acceptance and access to vaccines however indicates that a potential increase in supply will lead to an increase in demand. This should prompt policymakers to regulate vaccine supply to ensure that sufficient vaccines are distributed to low-income countries as well. Our results also send a strong message to policymakers on the importance of provision of access to vaccines to LICs and fragile nations in the event of possible future pandemics as well.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

This study was approved by the Research Committee of College of Dentistry, Dar Al Uloom University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (COD/IRB/2020/2). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

MN and MZN: conceptualization, methodology, and writing—original draft. MN, MZN, MA-A, IA-S, SM, AS, AY, AB, OE, AA, YT, and SR: investigation, data collection, and writing—review for important intellectual content and editing. SR, MN, and MZN: data analysis. All authors approved the final draft of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Postgraduate and Scientific Research at Dar Al UIoom University for their support for this work. The authors also extend their sincere acknowledgment and appreciation to the HCWs who stayed back in Yemen despite the conflict, to serve the Yemeni population.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.914943/full#supplementary-material

1. WHO. World Health Organization Health Emergency Dashboard. WHO COVID-19 Homepage. Available online at: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed March 11, 2022).

2. Whittaker C, Walker PGT, Alhaffar M, Hamlet A, Djaafara BA, Ghani A, et al. Under-reporting of deaths limits our understanding of true burden of covid-19. BMJ. (2021) 375:n2239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2239

3. Noushad M, Al-Saqqaf IS. COVID-19 case fatality rates can be highly misleading in resource-poor and fragile nations: the case of Yemen. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2021) 27:509–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.01.002

4. WHO. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Variants. World Health Organization. Available online at: https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants (accessed May 26, 2022).

5. WHO. Health and Care Worker Deaths During COVID-19. WHO (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/20-10-2021-health-and-care-worker-deaths-during-covid-19 (accessed March 1, 2022).

6. WHO. Only 1 in 4 African Health Workers Fully Vaccinated Against COVID-19. WHO (2021). Available online at: https://www.afro.who.int/news/only-1-4-african-health-workers-fully-vaccinated-against-covid-19 (accessed March 1, 2022).

7. Our World in Data. Available online at: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed March 13, 2022).

8. Noushad M, Rastam S, Nassani MZ, Al-Saqqaf IS, Hussain M, Yaroko AA, et al. A global survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers. Front Public Health. (2022) 9:794673. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.794673

9. Sage Working Group. Report of the Sage Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Sage Working Group (2014). Available online at: https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WOR KING_GROUP_vaccine_hesitancy_final.pdf (accessed June 30, 2021).

10. Noushad M, Al-Awar MS, Al-Saqqaf IS, Nassani MZ, Alrubaiee GG, Rastam S. Lack of access to COVID-19 vaccines could be a greater threat than vaccine hesitancy in low-income and conflict nations: the case of Yemen. Clin Infect Dis. (2022) 2:ciac088. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac088

11. Noushad M, Nassani MZ, Alsalhani AB, Koppolu P, Niazi FH, Samran A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine intention among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccines. (2021) 9:835. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080835

12. Elharake JA, Galal B, Alqahtani SA, Kattan RF, Barry MA, Temsah MH, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. (2021) 109:286–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.07.004

13. Saddik B, Al-Bluwi N, Shukla A, Barqawi H, Alsayed HAH, Sharif-Askari NS, et al. Determinants of healthcare workers perceptions, acceptance and choice of COVID-19 vaccines: a cross-sectional study from the United Arab Emirates. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2021) 18:1–9. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1994300

14. Al-Marshoudi S, Al-Balushi H, Al-Wahaibi A, Al-Khalili S, Al-Maani A, Al-Farsi N, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) toward the COVID-19 vaccine in oman: a pre-campaign cross-sectional study. Vaccines. (2021) 9:602. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060602

15. Zein S, Abdallah SB, Al-Smadi A, Gammoh O, Al-Awaida WJ, Al-Zein HJ. Factors associated with the unwillingness of Jordanians, Palestinians and Syrians to be vaccinated against COVID-19. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2021) 15:e0009957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009957

16. Shibani M, Alzabibi MA, Mouhandes AE, Alsuliman T, Mouki A, Ismail H, et al. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among Syrian population: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:2117. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12186-6

17. Mohamad O, Zamlout A, AlKhoury N, Mazloum AA, Alsalkini M, Shaaban R. Factors associated with the intention of Syrian adult population to accept COVID19 vaccination: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1310. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11361-z

18. Al-Metwali BZ, Al-Jumaili AA, Al-Alag ZA, Sorofman B. Exploring the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population using health belief model. J Eval Clin Pract. (2021) 27:1112–22. doi: 10.1111/jep.13581

19. Ahmed MAM, Colebunders R, Gele AA, Farah AA, Osman S, Guled IA, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptability and adherence to preventive measures in Somalia: results of an online survey. Vaccines. (2021) 9:543. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060543

20. Smith PJ, Kennedy AM, Wooten K, Gust DA, Pickering LK. Association between health care providers' influence on parents who have concerns about vaccine safety and vaccination coverage. Pediatrics. (2006) 118:e1287–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0923

21. Koum Besson ES, Norris A, Bin Ghouth AS, Freemantle T, Alhaffar M, Vazquez Y, et al. Excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic: a geospatial and statistical analysis in Aden governorate, Yemen. BMJ Glob Health. (2021) 6:e004564. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004564

22. Bin Ghouth AS, Al-Shoteri S, Mahmoud N, Musani A, Baoom NA, Al-Waleedi AA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Seroprevalence in Aden, Yemen: A Population-Based Study (2021). Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3909778

23. Ibrahim Arif S, Mohammed Aldukhail A, Dhaifallah Albaqami M, Cabauatan Silvano R, Titi Msn MA, Arif BI, et al. Predictors of healthcare workers' intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: a cross sectional study from Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Biol Sci. (2021) 29:2314–22. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.11.058

24. Elhadi M, Alsoufi A, Alhadi A, Hmeida A, Alshareea E, Dokali M, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and acceptance of healthcare workers and the public regarding the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:955. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10987-3

25. UNICEF. Yemen Receives 360 000 COVID-19 Vaccine Doses Through the COVAX Facility. UNICEF (2021). Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/yemen-receives-360000-covid-19-vaccine-doses-through-covax-facility (accessed March 1, 2022).

Keywords: vaccine acceptance, low-income country, Yemen, lack of access, COVID-19

Citation: Noushad M, Nassani MZ, Al-Awar MS, Al-Saqqaf IS, Mohammed SOA, Samran A, Yaroko AA, Barakat A, Elmi OS, Alsalhani AB, Talic YF and Rastam S (2022) COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Associated With Vaccine Inequity Among Healthcare Workers in a Low-Income Fragile Nation. Front. Public Health 10:914943. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.914943

Received: 07 April 2022; Accepted: 17 June 2022;

Published: 11 July 2022.

Edited by:

Francesca Licata, University Magna Graecia of Catanzaro, ItalyReviewed by:

Hannah Brindle, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, United KingdomCopyright © 2022 Noushad, Nassani, Al-Awar, Al-Saqqaf, Mohammed, Samran, Yaroko, Barakat, Elmi, Alsalhani, Talic and Rastam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammed Noushad, bS5ub3VzaGFkQGRhdS5lZHUuc2E=; aW55YTExM0B5YWhvby5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.