- 1Department of Community Medicine, Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University Medical College, Pune, India

- 2State Family Welfare Bureau, Department of Public Health, Government of Maharashtra, Pune, India

- 3United Nations Children's Funds (UNICEF), Mumbai, India

Background: Providing preconception care through healthcare workers at the primary health care level is a crucial intervention to reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes, consequently reducing neonatal mortality. Despite the availability of evidence, this window of opportunity remains unaddressed in many countries, including India. The public health care system is primarily accessed by rural and tribal Indian population. It is essential to know the frontline healthcare workers perception about preconception care. The study aimed to identify barriers and suggestions for framing appropriate strategies for implementing preconception care through primary health centers.

Methods: The authors conducted a qualitative study using focus group discussions (FGDs) with 45 healthcare workers in four FGDs (8–14 participants in each), in four blocks of Nashik district. The transcribed discussions were analyzed in MAXQDA software using the Socio-Ecological Model as an initial coding guide, including four levels of factors (individual, interpersonal, community, and institutional) that influenced an individual's behavior to use preconception care services.

Results: Healthcare workers had some knowledge about preconception care, limited to adolescent health and family planning services. The interpersonal factors included heavy workload, stress, lack of support and co-operation, and paucity of appreciation, and motivation. The perceived community factors included poverty, migration, poor knowledge of preconception care, lack of felt need for preconception services, the influence of older women in the household decision, low male involvement, myths and misconceptions regarding preconception services. The identified institutional factors were lack of human resources, specialized services, logistics, and challenges in delivering adolescent health and family planning programs. Healthcare workers suggested the need for program-specific guidelines, training and capacity building of human resources, an un-interrupted supply of logistics, and a unique community awareness drive supporting preconception care services.

Conclusion: Multi-level factors of the Socio-Ecological Model influencing the preconception care services should be considered for framing strategies in the implementation of comprehensive preconception care as a part of a continuum of care for life cycle phases of women.

Introduction

There has been increasing focus on Preconception care (PCC) globally, mainly due to its contribution to reducing adverse pregnancy outcomes. The present continuum of care does not include care before pregnancy. PCC bridges the gap in the continuum of care and aims to reduce parental risk factors before conception, thereby improving maternal and infant outcomes (1). The effectiveness of preconception interventions has been documented since 1979 (2). The systematic reviews since 2002 have strengthened the evidence of the utility of preconception interventions in reducing adverse pregnancy outcomes even in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) (3–10). Despite the availability of evidence-based PCC interventions, only Bangladesh (11), Philippines, Sri Lanka (12), China (13), United States of America (USA) (6), and United Kingdom (UK) (14) have provided guidelines and introduced PCC in their public health services (15). This window of opportunity for the timely achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) remains unaddressed for most countries, including India.

The maternal mortality ratio for India in the twenty-first century has declined from 301 (2001–2003) to 113 per 100,000 live birth (2016–18) (16). Similarly, the under-five child mortality rate has considerably reduced from 59 (2010) to 36 (2018) in the last decade (17). Nevertheless, the pace of this reduction has been slowed down in recent years (18, 19). World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended the rollout of PCC activities globally in 2013 (12). The government of India also included PCC in the India Newborn Action Plan, affirming PCC as one of the most critical pillars of the intervention package to address stillbirth and newborn health (20). The Federation of Obstetric and Gynecological Societies (FOGSI), India, circulated good clinical practices on PCC (21). However, these recommendations remain limited to ‘specialists' groups, extending services to upper socio-economic classes only. The primary health service provider in rural areas is the public sector (72%) (22). In India, presently PCC concept is limited to birth spacing services. To reach the rural, especially the vulnerable tribal population, and to widen the scope of PCC, implementing PCC services through the public health system in India is necessary. It is inevitable to consider the knowledge and perceptions of health workers to have a robust strategy.

PCC involves identifying and modifying potential risks for adverse pregnancy outcomes in the preconception period. Studies have suggested that identifying practical and feasible interventions based on local situations are crucial (23–26). Some health service research studies have identified factors contributing to the delivery and uptake of the PCC. Most of these studies are from High-Income Countries (27–36), and very few from Low-Income Countries (37–39). Studies from High-Income Countries identified lack of knowledge, awareness, demand, planning, publicity, unclear division of responsibilities, and poor coordination as challenges perceived by healthcare providers in providing PCC services (29, 31, 33, 35, 40). Health behavior of an individual is determined by several factors and it is important to know the knowledge and perceptions of the frontline healthcare workers (HCW). HCW are the first contact health care providers in the community and have a pivotal role in providing services. The extent of knowledge, behavior, and perception about PCC among HCW in India is almost unknown except for adolescent healthcare services and family planning services. To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study in India that seeks the perceptions of frontline healthcare workers about preconception care. The study aims to explore the healthcare workers knowledge and perceptions about challenges and strategies in introducing PCC. This study is a part of a comprehensive intervention study that broadly aims to reduce low birth weight and preterm births by addressing the known risk factors in the preconception period. The knowledge and behavior among women desiring pregnancy regarding preconception care are reported elsewhere (41).

Methods

The present paper uses the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines.

Study design

This is a qualitative study using Focus Group Discussions (FGD).

Study setting

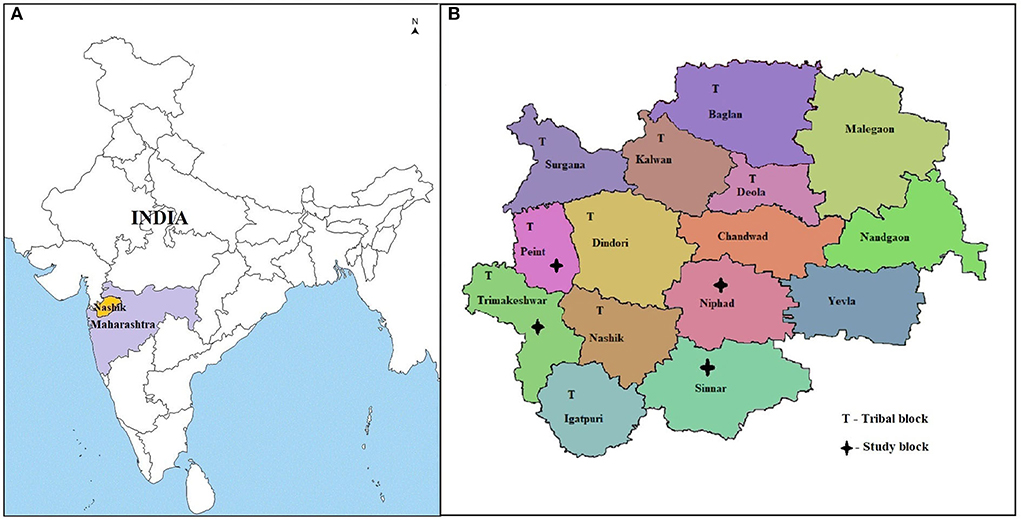

The authors conducted the study in rural areas of Nashik District, Maharashtra, India, covering a population of 6,109,052 (22). Nashik district was selected purposively as the district is a tribal dominant district. There are 15 blocks in the district, of which the government had notified nine blocks as tribal. Four blocks were selected, of which one tribal block and one non-tribal block were selected randomly as intervention blocks. Furthermore, adjacent one tribal and one non-tribal block were selected to match socio-cultural and geographical features as comparison blocks. Thus, two tribal and two non-tribal blocks were selected, covering a population of 976,149 individuals (15.98% of the district population). Figure 1 shows the locations of selected blocks.

Figure 1. Map of India showing the location of the study area, 2018-19. (A) India showing the location of selected Nashik district, State Maharashtra (B) Nashik district with selected study blocks. Source: Maps of India freely available and accessible at www.mapsofindia.com.

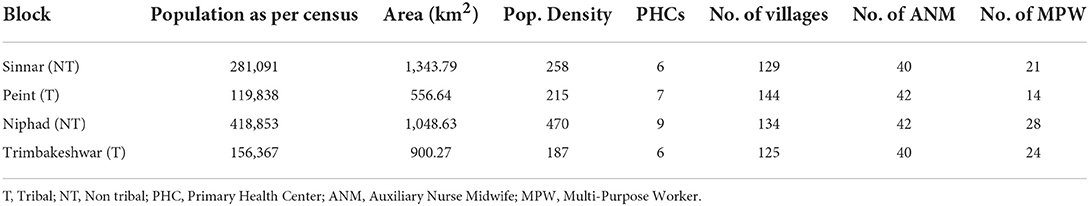

Table 1 gives the demographic information of selected blocks as per Census 2011 (22).

The public healthcare system in rural and tribal India is mainly through the Primary Health Center and Health Sub-Centers. Nashik district has 108 Primary Health Centers (PHCs) (each covering about 20,000–30,000 population each and having about 15 healthcare workers) and 592 Health Sub-Centers (HSC) (each covering about 3,000–5,000 population and having three healthcare workers).

Participants and recruitment

Female health workers (Auxiliary Nurse Midwife- ANM) and male healthcare workers (Multi-Purpose Workers- MPW) were the study participants working primarily at PHC and HSCs, and some of which were contractual. The MPW and ANM receive 1 year, and one and a half years of special professional health care training, respectively, after passing 10 years of regular schooling. About one-third of health workers [83] from study blocks were approached and informed through the institutional head about the purpose of the study, date, and venue of the FGD. A total of 45 HCW who volunteered to participate in four FGDs were recruited through convenient sampling. The team had planned to conduct one FGD in each block, and accordingly four FGDs were conducted. The authors had not planned to conduct FGDs till the data saturation point.

Data collection

An interview guide was used as a tool for data collection and it was prepared through a consultative process. The interview guide was validated, translated into the local language (Marathi), back-translated (English), and pre-tested in another rural area with similar settings. The interview guide consisted of domains, sub-domains, and probes. The probes were open-ended to allow the HCW to describe their knowledge, perception, and practices; identify challenges and possible strategies to deliver PCC services (Supplementary File S1).

All FGDs were conducted in June 2018 by four investigators, who are teaching faculties from a medical college and assisted by two research coordinators. Out of six members, four are females. All faculties are post-graduate in community medicine, one of them is doctorate also, and the research coordinators are post-graduate in public health. All the members are trained in conducting qualitative research and FGDs and have 5–42 years experience of doing research. The faculties conducted FGDs, and the coordinators facilitated by taking notes. FGDs were conducted in a separate room in the PHC, with exclusive presence of research team and participants only. Each research team conducting a FGD had two members, one faculty and one research coordinator. The authors ensured representation from all the PHC of the selected blocks. Before starting FGD, written informed consent was obtained from the HCW for participation, audio recordings, and subsequent publication. The facilitator ensured that the moderators covered all domains during discussions. The information about participant's age, sex, education, work-station, and work experience was collected. The facilitator gave the participants numbered placards, and the moderator addressed them by their respective placard numbers during FGD. They were also encouraged to freely discuss their perceptions, views, and experiences. All FGDs were conducted in the local language (Marathi). The research team and participants met for the first time during the FGD. The moderators first briefly introduced the project and further discussed domain and sub-domains. The moderator used probes if the discussion got diverted from the topic. Each FGD was conducted for about 50 minutes.

Data analysis

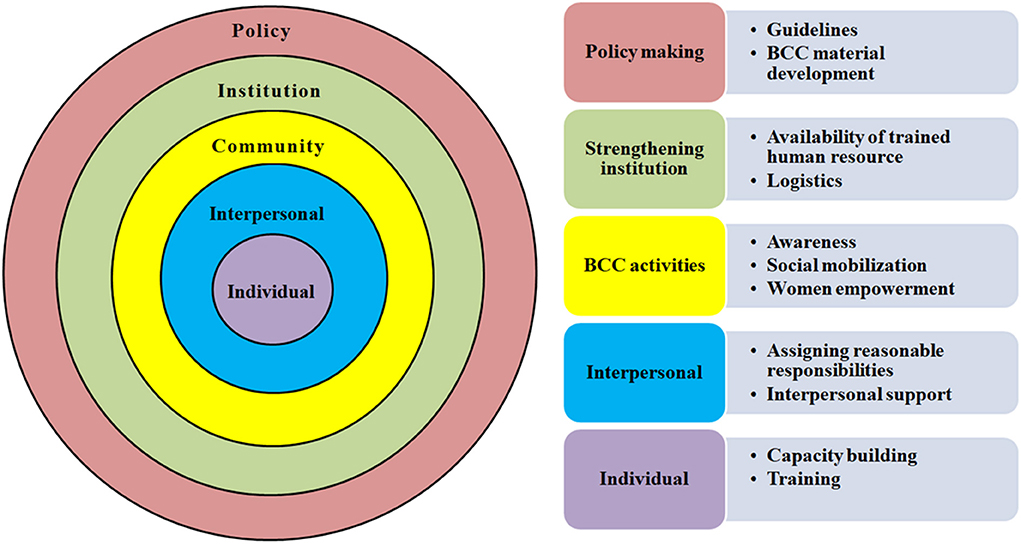

For accuracy, all FGDs were transcribed verbatim and checked several times against recordings and notes. Data were analyzed using a content analysis deductive approach using the Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) (42). The SEM is a theory-based framework to understand the multi-level and interactive effect of personal and environmental factors that determine the behavior of an individual and is used in many qualitative research studies. The framework includes factors at individual level, interpersonal level, i.e., among peers and colleagues, community and social level, and institutional levels, i.e., medical and social services (43). The codes namely individual, interpersonal, community and social, and institutional levels were used as an initial coding guide to describe themes. Newly derived codes representing each of these themes were added to the framework to build our model of factors influencing PCC. Data were analyzed using MAXQDA version 20.2. Three researchers, who were part of conducting FGD independently identified themes and sub-themes and finalized them through discussion with the remaining research team members. Any disagreement in themes was discussed and resolved. The research team translated the transcripts into English and included the unique quotes in Results Section. The data is deposited in the department.

Results

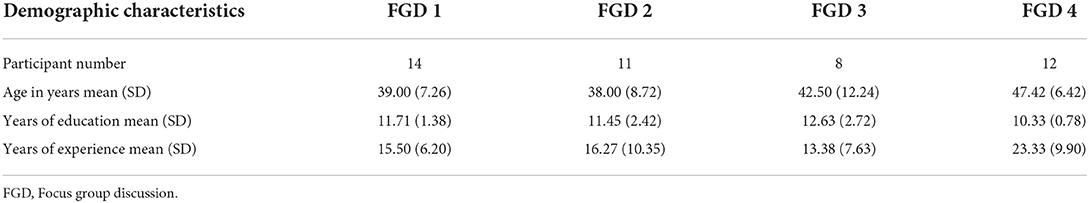

Table 2 gives the details of the participants. Forty-five health care providers (31 female and 14 males) participated in these four FGDs, with 8–14 participants in each group.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of focus group discussion participants, Nashik, India 2018–19 (n = 45).

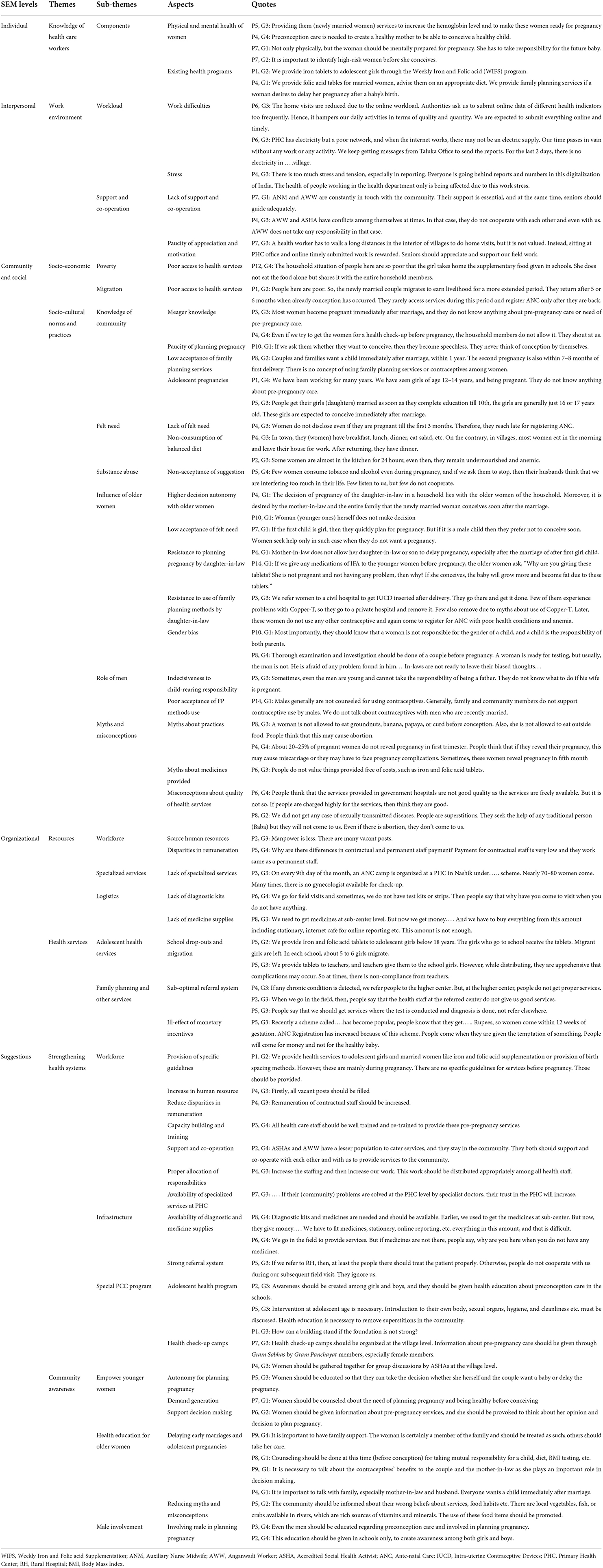

Table 3 gives the identified themes and sub-themes under four levels of SEM including the unique quotes denoting the participant and focus group numbers. Identified sub-themes were almost similar for tribal and non-tribal blocks; hence combined results are presented.

Table 3. Identified themes and sub-theme based on Socio-Ecological Model after focus group discussion.

Individual

Knowledge of healthcare workers

Most of the participants had some knowledge about PCC and highlighted the importance of women's health before conception. Some key health aspects like physical and mental growth and development, hemoglobin levels, body mass index (BMI), illness, and medical history of a woman before pregnancy were narrated by HCW as important components of preconception services. Participants also reported the link between the ill health of the woman with low birth weight and adverse pregnancy outcomes. HCW were aware that there is no formal PCC program in the country. However, adolescent health program and family planning services were highlighted as the essential components of PCC services.

Interpersonal

Work environment

Most of the participants informed about the heavy workload and workplace stress. They elaborated that compliance with supervisors' work pressure related to timely reporting took maximum time. This ultimately affected their primary work of providing services to the community. Few participants informed about poor support and co-operation from colleagues. The discrepancies in the payment of regular and contractual staff, and lack of appreciation and motivation from seniors were some of the points mentioned by participants for being dissatisfied.

Community and social

Socio-economic

Frontline workers stated that poverty was one of the factors that aggravated women's health conditions. These women lack access to health services.

Participants reported a significant migration, especially among the newly married couples for earning opportunities. The migrated couple rarely avail health services at their workplace. The women are already in the second trimester when they return home, and it is too late to optimize her health status.

Socio-cultural norms and practices

Knowledge among community members

Participants reported that early marriages are common in the community. School drop-out rate are high among young girls as families prefer them to get married leaving schools. Despite their young age, married girls are pressured to conceive immediately after marriage. Participants observed insufficient knowledge, minimum self-awareness, and lesser autonomy in decision-making among women regarding planning a pregnancy or the use of family planning services. HCW also stated that after first delivery, many women may get Copper-T inserted in a government hospital but remove it in a private hospital within a few months and conceive. This short inter-pregnancy interval may lead to anemia, undernourishment among women, and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

HCW stated that preconception period was not viewed as a critical phase in the woman's reproductive cycle. Families would pay attention only when the pregnancy was confirmed. Very few women consulted health workers to avail preconception care services. Women would rarely think of eating balanced diet before pregnancy. The priority of serving food has always been given to family members than women themselves.

Substance abuse

Mishri (application of roasted tobacco on gums and teeth) and alcohol consumption were predominantly seen among older tribal women. The respondents mentioned that on coming across women consuming Mishri or alcohol, they tried to convince them to abstain from the habits, informing the side effects on their health and the health of the upcoming baby. However, it was usually not appreciated by women and their husbands.

Influence of older women

The community workers noted that the older woman in the household (mainly mother-in-law) usually influenced the decision to plan pregnancy. They invariably force the newly married women to conceive immediately after marriage (usually within 1 year of marriage). Many older women opposed spacing, arguing that they had undergone many pregnancies and deliveries without any complications. Convincing older women of the household about spacing was a significant challenge faced by health workers as these older women boast that they knew everything.

Health workers stated that the family members want at least two children (invariably including one son) at the earliest. After that, couples may opt for sterilization (mainly women). However, if the woman has one or more girls, she is almost compelled to conceive and has no say in planning her pregnancy. The family members do not allow women to decide for herself. Besides, the older women believe that it is the daughter-in-law who is responsible for any reproductive issues, including infertility. If she fails to conceive or cannot give birth to a son, the family members deem it her failure and may subject her to physical or mental violence.

Role of men

At times, married boys, in adolescent age group could not take decision regarding conception. Health workers reported low contraceptive use among married male partners irrespective of age. Older members of the household do not even accept contraceptive use by young, newly married men.

Myths and misconceptions

Participants perceived many myths and taboos regarding food habits and medication in the community. The community followed the tradition of not disclosing the pregnancy during the first trimester. Few older women do not allow younger newly married women to eat papaya, banana, horse gram (Chana), etc. They believe that it causes miscarriage/abortions. The taboo also exists regarding the consumption of Iron and Folic Acid (IFA) tablets, believing it leads to healthier, bigger-sized baby and thereby leading to complications during delivery. Women are not allowed to undergo any health check-ups in the pre-pregnancy stage, especially by older women. There is a lack of knowledge regarding Reproductive Tract Infections (RTI) or Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) among women. Women sometimes sought services from traditional healers for primary or secondary infertility or abortion.

The community members have misconceptions about government services also. People do not appreciate and avail government services, thinking them as substandard. Medications like Iron and Folic acid tablets, deworming tables, etc., are given free of cost but not consumed by the women.

Organizational

Resources

Most participants emphasized the scarcity of human resources and specialized services at PHC. Further, health providers also highlighted scarcity of logistics, including irregular supply of investigation kits, medicines, and contraceptives, as one of the primary reasons leading to difficulties in diagnosis and treatment of acute or chronic conditions during preconception.

Health services

Participants highlighted adolescent health program and family planning services as the key services of PCC.

Adolescent health program

While discussing PCC, most participants spontaneously referred to the adolescent health program including provision of iron, folic acid and deworming tablets etc. The program is perceived as successful for adolescent school girls, but providing services to school drop-outs and migrants is challenging.

Family planning and other services

Family planning services are rarely provided to newly married couples. Medical services are provided in case of the irregular menstrual cycle or any other reproductive health-related problem or any diagnosed conditions. The participants often referred to antenatal and perinatal care. Participants explained that newly married women are regularly counseled about medical check-ups, but their compliance is poor. Women with chronic conditions are referred to secondary or tertiary health care centers. Nevertheless, these problems often remain unresolved due to inaccessibility, lack of proper services, or lack of confidentiality at the health care center. The issue of providing incentives to women was also raised. Incentives are often provided to the beneficiary for family planning and maternal health services. Frontline workers also drew attention to the ill effects of monetary incentives.

Suggestions for implementation

Strengthening health system

HCW expressed the need for afresh guidelines for preconception care. Increasing the trained workforce and capacity building of human resources was suggested. The participants specially underlined the need of training and refreshers training to provide preconception care services. Most participants suggested that reducing workload, re-distribution of work, and minimizing discrepancies in the payments will help HCW work efficiently. They strongly conveyed the need of support and co-operation from all colleagues. Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) and Anganwadi workers (AWW) have a lesser population to cater to, leading to better reach in the community, and hence enhanced support from ASHAs and AWW is expected. Some of the participants suggested incentive-based utilization of ASHA's services for PCC. The need for specialist services at PHC level was insisted upon. They believed that the availability of specialist doctors at PHC would play a significant role in the early diagnosis and treatment of high-risk women in the preconception period. This would further help build trust in the community and affect the accessibility of health care services. Strengthening health care institutions in the delivery of PCC services through regular supplies of diagnostic kits and medicines was suggested. The need for a robust referral system was also insisted upon.

Special PCC program

Most of the participants emphasized that the services should begin with adolescents. The Weekly Iron and Folic acid supplementation (WIFS) program can be subsumed as a part of PCC. The participants also emphasized taking a detailed medical history, medical check-ups, and laboratory investigations before pregnancy. They insisted on testing sickle cell anemia as the district belongs to the highly prevalent belt. Besides the management of highly prevalent diseases like sickle cell anemia or chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension; regular health check-up camps should be organized for diagnosis and treatment of reproductive tract infections.

Community awareness

Empower younger women

Participants thought that women's education plays a vital role in preconception care. Younger women can be empowered through health education, providing autonomy for planning pregnancy and generating demand for PCC services. Participants narrated that few educated women are less hesitant to come forward and ask about preconception care, use of contraceptives etc.

Health education for older women

Counseling was one of the essential strategies communicated by the respondents. It was suggested that families, especially the older women (mother-in-law), should be counseled, rather than individuals. Counseling of the entire family should be done before marriage and after marriage to include aspects like appropriate age of marriage, delaying pregnancy, increasing inter-pregnancy interval, the importance of PCC and health check-up before pregnancy, and prevention of domestic violence. Awareness about consuming a balanced diet, the need for three meals a day, the use of locally or seasonally available vegetables, and non-vegetarian items, especially seafood, should be encouraged.

Creating awareness in the community to dispel myths and taboos through health education was also recommended. Consumption of folic acid three months before conception to prevent neural tube defects should be informed on priority. Prevention of consanguineous marriage or between carriers of the sickle cell trait should also be included in counseling.

Male involvement

Awareness should also be created among male members to plan pregnancy. The use of contraceptives for delaying pregnancy, especially among adolescents, should be promoted.

Discussion

FGD method involving 8–14 participants is well documented to understand the knowledge and explore the perceptions, attitudes, and suggestions about a specific topic through an active interaction (44). All the participants were frontline health workers; hence authors thought documenting their awareness and perceptions is important. All the FGDs were conducted by qualified and experienced persons, allowing the health workers to express their opinions freely in the absence of supervisors. This study provides evidence on the perceptions of the HCW in rural and tribal settings. The study observed no difference in perception of challenges and strategies between tribal and non-tribal areas. This may be due to the health workers' comparable qualifications and experience, regularly transferred from tribal to non-tribal areas and vice versa.

The SEM considers the complex interplay between individual, interpersonal, community, and institutional factors (43). The most common perceived barriers at the individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels were sub-optimal knowledge, heavy workload, stress, and inadequate health workforce and resources. The most common perceived barriers at the community and social level were insufficient knowledge about preconception care among women and the community and the influence of older women. These were inter-linked with other socio-economic criteria and socio-cultural norms and practices.

Individual

Most of the HCW in this study have limited knowledge about PCC, which is similar to those observed in studies conducted in High-Income Countries like UK (31), and Low-Income Countries like Ethiopia (37, 38).

Interpersonal and organizational

The perceived challenges in the present study included limited health workforce, availability of specialist services, challenges related to payments of health workers, heavy workload, stress and competing for work priorities, lack of comprehensive PCC program analogous with findings of other studies (32, 34). General Practitioners also observe payment differences and unclear allocation of responsibilities in developed countries (29, 45). Chuang et al. stated that though health providers are aware of the importance of positive health before pregnancy, preconception counseling is rarely initiated and is not a high priority for them (34).

Community and social

The health care providers, mainly from High-Income Countries, report a similar lack of women's reproductive health knowledge, including PCC (32, 33, 35, 40, 45–47). This may be mainly due to the unawareness of the importance of preconception care in the community. A qualitative study in Pennsylvania observed that Physicians perceive rural community practices of unintended pregnancies, early childbearing, and large families as the major barriers to contraceptive and preconception care. They also added the absence of educational goals for career and life planning, including family planning, among younger women as the critical identified barriers (34). Another study by Peterson-Burch among the Latino population reports that families were reluctant to discuss reproductive health problems, particularly using birth control measures (30).

Indian scenario

The challenges to the implementation of PCC like illiteracy of adult Indian women (28.5%), marriage before legal age (23.3%), adolescent pregnancy (6.8%), anemia in non-pregnant women (57.2%), unmet need for family planning and spacing (9.4% and 4.0% respectively), are still highly prevalent. Some health workers talk about family planning (23.9%) as reported in the National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS) (48). The scenario is similar for the Nashik district (48). In India, many girls marry in adolescent age, have lower education and limited knowledge about reproductive health (49), lower decision-making autonomy (32, 50). It is also observed that mother-in-law influences the newly married woman's family planning decision (51, 52). Compliance with IFA supplementation during the peri-conception period varies from 5 to 43% (16, 37, 48). This low acceptance may be due to lack of knowledge, general feeling among women that conception and delivery are natural events and do not need intervention (53). Male involvement is low due to poor knowledge and gender norms (54).

Model for PCC

Similar to the present study findings, capacity building and training of health staff and formulating guidelines for comprehensive PCC services are recommended by many studies (28, 30, 32, 40). In line with our study, other studies also emphasize creating awareness in the community about the need and availability of PCC services, which could be achieved through focused mass educational campaigns (28, 40). Promoting motivation and demand for informed choices about conception and birth spacing should be executed through counseling and women empowerment (32, 40). One Australian study proposed the availability of a checklist, patient brochures, hand-outs, and posters to support the delivery of PCC interventions (32).

Thus, based on current findings, a model can be proposed for PCC services. Figure 2 depicts the core contents of this conceptual model based on the SEM framework, where the individual level shows minimal scope while the policy level shows the highest scope.

The model includes the dissemination of specific guidelines, health education material, and training of health workers. Behavioral Change and Communication (BCC) activities and material using different media can be developed and used during special awareness drives. The educational material should focus on demand generation, women empowerment, and social mobilization. Both, individual and group approaches (like Gram Sabhas) can be used for counseling. PCC may also be included as a part of Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (which provides specialized ANC services at PHC level on a specific day). This scheme should be supported with preconception care services, including medical examination and treatment if needed through capacity building of the healthcare workers, assigning reasonable responsibilities, and interpersonal support. These interventions will bring sustainable behavioral change to the community.

The situation and the challenges in most LMICs are similar to those identified in the present study. Hence the proposed model for PCC may be used as a preliminary guide by the LMICs for developing and implementing the PCC interventions. Further research should continue to determine the effect of this model in delivering PCC.

Strengths and limitations

The unique feature is that the study provides insights into the perceptions of the frontline health workers in rural settings (including tribal), considering multi-level factors of the SEM influencing the PCC services. The small sample size involving only one district limits the generalizability of the findings. The absence of representation from the urban and private sectors is another limitation. After a few initial meetings about the larger intervention project, the authors conducted this study. Hence, there is a possibility of acquiring some knowledge by HCW at PHC or subcenter before focus group discussions. Despite these limitations, study findings helped to develop a model strategy for implementing PCC services in the primary health system.

Conclusion

The study identifies key challenges perceived by the frontline healthcare workers as inadequate workforce and lack of knowledge and acceptance about preconception care services in the community, especially older female family members. Furthermore, it provides a model framework that can be used to develop strategies for implementing preconception care services.

We recommend an urgent need of institutional strengthening and human resource capacity building for a comprehensive PCC program. Appropriate BCC material designing for community awareness about PCC would be one of the best strategies for implementing PCC in the health care delivery system. The government may introduce PCC to address the gap in the continuum of care and give due importance. PCC can be an integral component of reproductive and child health, and the concerned program can be renamed Reproductive, Preconception, Maternal Neonatal Child Health and Adolescents (RPMNCHA).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, on reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (DCGI Regd. No. ECR/518/Inst/MH/2014/RR-17) vide letter number BVDUMC/IEC/11 dated 30th April 2018. Written informed consent for participation, and audio recording was obtained from all participants prior to the focus group discussion.

Author contributions

AC, JG, PP, and SP designed and conducted interviews under the supervision of PD. MK and AD helped in the recruitment of participants. AC, PD, and JG independently identified the themes, sub-themes, and conducted data analysis. AC, PD, JG, PP, and SP discussed and finalized the themes and sub-themes. AC prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. PD, JG, and PP undertook a critical review of the manuscript. AP, AS, PD, KB, AD, and AC drafted the guideline for the comprehensive public health interventions and its assessment. All authors conceived the study, reviewed, and approved the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UNICEF, Maharashtra, India through Department of Public Health, Government of Maharashtra.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Principal Secretary, Department of Public Health, Government of Maharashtra and all health officials of Department of Public Health at state and district level for their co-operation and support; Rajeshwari Chandrasekar, Chief of the Field Office, UNICEF Maharashtra; and Luigi D'Aquino, Chief of Health, UNICEF India and UNICEF Consultants and staff for the funding and technical support. Authors specially thank the health workers for their participation in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.888708/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Dean SV, Lassi ZS, Imam AM, Bhutta ZA. Preconception care: closing the gap in the continuum of care to accelerate improvements in maternal, newborn and child health. Reprod Health. (2014) 11:S1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-S3-S1

2. Freda MC, Moos MK, Curtis M. The history of preconception care: evolving guidelines and standards. Matern Child Health J. (2006) 10:43–52. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0087-x

3. Korenbrot CC, Steinberg A, Bender C, Newberry S. Preconception care: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J. (2002) 6:75–88. doi: 10.1023/A:1015460106832

4. Whitworth M, Dowswell T. Routine pre-pregnancy health promotion for improving pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. (2009) 4:536. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007536

5. Goossens J, De Roose M, Van Hecke A, Goemaes R, Verhaeghe S, Beeckman D. Barriers and facilitators to the provision of preconception care by healthcare providers: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. (2018) 87:113–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.06.009

6. Boulet SL, Parker C, Atrash H. Preconception care in international settings. Matern Child Health J. (2006) 10:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0091-1

7. Kotirum S, Kiatpongsan S, Kapol N. Systematic review of economic evaluation studies on preconception care interventions. Health Care Women Int. (2020) 1–15. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2020.1817025

8. Dean S V, Imam AM, Lassi ZS, Bhutta ZA. Systematic Review of Preconception Risks and Interventions. Div Women Child Heal Aga Khan Univ. (2012). 12(3):1–509. Available online at: https://globalmotherchildresearch.tghn.org/site_media/media/articles/Preconception_Report.pdf

9. Dean S, Rudan I, Althabe F, Webb Girard A, Howson C, Langer A, et al. Setting research priorities for preconception care in low- and middle-income countries: aiming to reduce maternal and child mortality and morbidity. PLoS Med. (2013) 10:1508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001508

10. Lassi ZS, Kedzior SGE, Das JK, Bhutta ZA. PROTOCOL Effects of preconception care and periconception interventions on maternal nutritional status and birth outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev. (2019) 15:1–9. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1007

11. World Diabetes Foundation. Preconception Care Through Religious Leaders in Bangladesh- Strengthening Pre-conception Care and Counseling on Diabetes and NCDs in Bangladesh Through Capacity Building in the Health System and Among Religious Leaders. Available online at: https://www.worlddiabetesfoundation.org/projects/bangladesh-wdf15-1237 (accessed March 25, 2021).

12. World Health Organization. Meeting to Develop a Global Consensus on Preconception Care to Reduce Maternal and Childhood Mortality and Morbidity. Geneva: WHO Headquarters, Geneva Meeting Report (2012). p. 78.

13. Zhou Q, Acharya G, Zhang S, Wang Q, Shen H, Li X. A new perspective on universal preconception care in China. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2016) 95:377–81. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12865

14. Public Health England. Making the Case for Preconception Care Planning and Preparation for Pregnancy to Improve Maternal and Child Health Outcomes. (2018). Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attacment_data/file/729018/making_the_case_for_preconception_care.pdf (accessed January 10, 2022).

15. Geneva Foundation for Medical Education Research. Obstetrics and Gynecology Guidelines. Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Available online at: https://www.gfmer.ch/Guidelines/Pregnancy_newborn/Preconception-care.htm (accessed December 11, 2021).

16. Office Office of Registrar General Government Government of India. Special Bulletin on Maternal Mortality in India 2016–2018. (2018). Available online at: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Bulletins/MMR%20Bulletin-2016-18.pdf (accessed March 25, 2021).

17. Office Office of Registrar General Government Government of India. Sample Registration system. Statistical report. (2018). Available online at: https://censusindia.gov.in/Vital_Statistics/SRS/Sample_Registration_System.html (accessed February 12, 2022).

18. Claeson M, Bos ER, Mawji T, Pathmanathan I. Reducing child mortality in India in the new millennium. Bull World Health Organ. (2000) 78:1192–9.

19. United Nations Children's Fund. UNICEF Data: Monitoring the Situation of Children Women. India: Key Demographic Indicators (2019). Available online at: https://data.unicef.org/country/ind/ (accessed March 20, 2021).

20. Ministry Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government Government of India. India Newborn Action Plan. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India (2014).

21. The Federation of Obstetric Gynecological Societies of India. Good Clinical Practice Recommendation (Mumbai). Available online at: https://www.fogsi.org/gcpr-preconception-care/ (accessed November 18, 2021).

22. Office Office of the Registrar General Government of India Ministry Ministry of Home Affairs Government Government of India. Census 2011. (2011). Available online at: https://censusindia.gov.in (accessed October 18, 2021).

23. Atrash H, Jack B. Preconception care: developing and implementing regional and national programs. J Hum Growth Dev. (2020) 30:363–71. doi: 10.7322/jhgd.v30.11064

24. Ebrahim SH, Lo SST, Zhuo J, Han JY, Delvoye P, Zhu L. Models of preconception care implementation in selected countries. Matern Child Health J. (2006) 10:37–42. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0096-9

25. Shannon GD, Alberg C, Nacul L, Pashayan N. Preconception healthcare delivery at a population level: construction of public health models of preconception care. Matern Child Health J. (2014) 18:1512–31. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1393-8

26. Mason E, Chandra-Mouli V, Baltag V, Christiansen C, Lassi ZS, Bhutta ZA. Preconception care: advancing from “important to do and can be done” to “is being done and is making a difference”. Reprod Health. (2014) 11(Suppl. 3):S8. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-S3-S8

27. Steel A, Lucke J, Reid R, Adams J. A systematic review of women's and health professional's attitudes and experience of preconception care service delivery. Fam Pract. (2016) 33:588–95. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmw094

28. Klein J. Preconception care for women with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a mixed- methods study of provider knowledge and practice. J Diabetes Res Clin Pr. (2017) 129:105–15. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.035

29. Poels M, Koster MPH, Franx A, Van Stel HF. Healthcare providers' views on the delivery of preconception care in a local community setting in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res. (2017) 17:92. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2051-4

30. Peterson-Burch FM, Olshansky E, Abujaradeh HA, Choi JJ, Zender R, Montgomery K, et al. Cultural understanding, experiences, barriers, and facilitators of healthcare providers when providing preconception counseling to adolescent Latinas with diabetes. Res J Women's Heal. (2018) 5:2. doi: 10.7243/2054-9865-5-2

31. Ojukwu O, Patel D, Stephenson J, Howden B, Shawe J. General practitioners' knowledge, attitudes and views of providing preconception care: a qualitative investigation. Ups J Med Sci. (2016) 121:256–63. doi: 10.1080/03009734.2016.1215853

32. Mazza D, Chapman A, Michie S. Barriers to the implementation of preconception care guidelines as perceived by general practitioners: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2013) 13:36. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-36

33. M'hamdi HI, van Voorst SF, Pinxten W, Hilhorst MT, Steegers EAP. Barriers in the uptake and delivery of preconception care: exploring the views of care providers. Matern Child Health J. (2017) 21:21–8 doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2089-7

34. Chuang C, Hwang SW, McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Rosenwasser L, Hillemeier MM, Weisman CS. Primary care physicians' perceptions of barriers to preventive reproductive health care in rural communities. Perspect Sex Reprod Heal. (2012) 44:78–83. doi: 10.1363/4407812

35. Bortolus R, Oprandi NC, Rech Morassutti F, Marchetto L, Filippini F, Agricola E, et al. Why women do not ask for information on preconception health? A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2017) 17:5. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1198-z

36. Ojifinni OO, Ibisomi L. Preconception care practices in Nigeria: a descriptive qualitative study. Reprod Health. (2020) 17:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-01030-6

37. Kassa A, Human S, Gemeda H. Level of healthcare providers' preconception care (PCC) practice and factors associated with non-implementation of PCC in Hawassa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. (2019) 29:903–12. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v29i1.12

38. Kassa A, Human SP, Gemeda H. Knowledge of preconception care among healthcare providers working in public health institutions in Hawassa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0204415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204415

39. Sattarzadeh N, Farshbaf-Khalili A, Khari E. Socio-demographic predictors of midwives' knowledge and practice regarding preconception care. Int J Women's Heal Reprod Sci. (2017) 5:212–7. doi: 10.15296/ijwhr.2017.38

40. Sijpkens MK, Steegers EAP, Rosman AN. Facilitators and Barriers for Successful Implementation of Interconception Care in Preventive Child Health Care Services in the Netherlands. Matern Child Health J. (2016) 20:117–24. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2046-5

41. Doke PP, Gothankar JS, Pore PD, Palkar SH, Chutke AP, Patil AV, et al. Meager perception of preconception care among women desiring pregnancy in rural areas: a qualitative study using focus group discussions. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:1489. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.689820

42. Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and practice. Jossey-Bass (2008). p. 465–85.

43. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Division Division of Communication. UNICEF 2017 Report on Communications for Development (C4D). (2018). Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/media/47781/file/UNICEF_2017_Report_on_Communication_for_Development_C4D.pdf (accessed June 28, 2022).

44. Wong LP. Focus group discussion: a tool for health and medical research. Singapore Med J. (2008) 49:256–60; quiz 261.

45. Stephenson J, Patel D Barrett G, Howden B, Copas A, Ojukwu O, et al. How do women prepare for pregnancy? Preconception experiences of women attending antenatal services and views of health professionals. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e0103085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103085

46. Saxena V, Naithani M, Kumari R, Singh R, Das P. Peri-conceptional supplementation of folic acid-knowledge and practices of pregnant women and health providers. J Fam Med Prim Care. (2016) 5:387. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.192374

47. Tokunbo OA, Abimbola OK, Polite IO, Gbemiga OA. Awareness and perception of preconception care among health workers in Ahmadu Bello University Teaching University, Zaria. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. (2016) 33:149. doi: 10.4103/0189-5117.192215

48. International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey – 5. International Institute for Population Sciences (2019). Available online at: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/ (accessed February 10, 2022).

49. Rose-Clarke K, Pradhan H, Rath S, Rath S, Samal S, Gagrai S, et al. Adolescent girls' health, nutrition and wellbeing in rural eastern India: a based study. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:673. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7053-1

50. Shakya HB, Dasgupta A, Ghule M, Battala M, Saggurti N, Donta B, et al. Spousal discordance on reports of contraceptive communication, contraceptive use, and ideal family size in rural India: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. (2018) 18. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0636-7

51. Kumar A, Bordone V, Muttarak R. Like Mother(-in-Law) Like daughter? Influence of the older generation's fertility behaviors on women's desired family size in Bihar, India. Eur J Popul. (2016) 32:629–60. doi: 10.1007/s10680-016-9379-z

52. Char A, Saavala M, Kulmala T. Influence of mothers-in-law on young couples' family planning decisions in rural India. Reprod Health Matters. (2010) 18:154–62. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(10)35497-8

53. Varghese JS, Swaminathan S, Kurpad AV, Thomas T. Demand and supply factors of iron-folic acid supplementation and its association with anemia in North Indian pregnant women. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0210634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210634

54. Nair S, Adhikari T, Juneja A, Gulati KB, Kaur A, Rao MVV. Community perspectives on men's role in the utilisation of maternal health services among saharia tribes in Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India: insights from a qualitative study. Matern Child Health J. (2021) 25:769–76. doi: 10.1007/s10995-020-03029-8

Keywords: preconception care, qualitative research, focus group discussion, Socio-Ecological Model, healthcare workers, challenges, suggestions

Citation: Chutke AP, Doke PP, Gothankar JS, Pore PD, Palkar SH, Patil AV, Deshpande AV, Bhuyan KK, Karnataki MV and Shrotri AN (2022) Perceptions of and challenges faced by primary healthcare workers about preconception services in rural India: A qualitative study using focus group discussion. Front. Public Health 10:888708. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.888708

Received: 03 March 2022; Accepted: 04 July 2022;

Published: 17 August 2022.

Edited by:

Rahul Shidhaye, Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences, IndiaReviewed by:

Vidya Raghavan, New Concept Centre for Development Communication, IndiaK. Anju Viswan, National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), India

Swati Shirwadkar, S. P. University of Pune, India

Copyright © 2022 Chutke, Doke, Gothankar, Pore, Palkar, Patil, Deshpande, Bhuyan, Karnataki and Shrotri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amruta Paresh Chutke, YW1ydXRhcmd1amFyQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Amruta Paresh Chutke

Amruta Paresh Chutke Prakash Prabhakarrao Doke

Prakash Prabhakarrao Doke Jayashree Sachin Gothankar

Jayashree Sachin Gothankar Prasad Dnyandeo Pore

Prasad Dnyandeo Pore Sonali Hemant Palkar

Sonali Hemant Palkar Archana Vasantrao Patil2

Archana Vasantrao Patil2