94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 05 April 2022

Sec. Occupational Health and Safety

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.870772

This article is part of the Research Topic Factors and health outcomes of job burnout View all 18 articles

Perceived organizational support (POS) in the relationship between neuroticism and job burnout among firefighters received little attention in China. A sampling of 716 firefighters in China, we drew on perceived organization support theory and the notion of support as a buffer in job burnout, examining moderating effects of POS on the relationship between neuroticism and three components of burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment). Also, this study explored the mediating effect of burnout on the relationship between neuroticism and mental health (i.e., anxiety and depression). We found that two components (depersonalization and emotional exhaustion) of burnout have significantly mediated the relationship between neuroticism and anxiety and depression. At the same time, POS reinforced the relationship between neuroticism and depersonalization and emotional exhaustion. Therefore, organizations can take our analysis into account when taking actions to improve firefighters' mental health. The implications of these findings were discussed.

The Chinese government faces the challenge of an increasing number of disasters and accidents along with its rapid economic and social development. As a result, Chinese firefighters need to tackle increasing fires and respond to other emergencies, resulting in a high death rate (1). Firefighters are working as first responders who face emergent tasks, including fire suppression and rescue services which may cause severe injuries or deaths. Witnessing long-lasting life-threatening events and tragedies occur on colleagues can negatively affect a person's mental and physical health (2), causing anxiety (3, 4) and depression (5, 6). Moreover, without enough external assistance and organizational support, firefighters' mental problems become a more challenging issue that needs to be tackled urgently.

The overarching idea of our study was to find the impact of organizational support and how personality traits, especially neuroticism, influences firefighters' mental health. Neuroticism is a negative emotional trait characterized by proneness to anxiety, emotional instability, and self-consciousness (7). The personality trait of neuroticism is associated with anxiety and depression (8–12). A body of research has identified neuroticism as a vulnerable factor in both depressions (13, 14) and anxiety (15, 16).

Perceived Organizational Support (POS) is defined as employees' perception about how their organization values their contribution and cares about their wellbeing (17). A previous study found that POS was negatively correlated with job burnout of employees, meaning that the less POS, the fewer satisfaction employees would feel, resulting in more severe burnout (18). According to Cohen and Wills (19), support can promote personal self-esteem and provide sufficient information to individuals to help them define, understand, and respond to stressful events. Meanwhile, support has a function to provide physical resources and has a social companionship function to satisfy people's need to be accompanied and feel a sense of belonging (20). Organizational support is especially meaningful for researching burnout, which has long been recognized as a combination of work-related symptoms, including generalized fatigue and loss of motivation (21). Although burnout is linked to general personality factors (22), there has been little research on the relationship between firefighters' neuroticism and burnout. Particularly, firefighters who perceive their organizations are supportive will perform better, believing that organizations will provide them with resources to cope with the stress leading to less burnout.

Burnout is a psychological syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, feelings of cynicism, and reduced personal accomplishment (23). A recent study has shown that job burnout is one of the risk factors for anxiety and depression (24). Different elements of burnout contribute to mental health issues, in which exhaustion was positively correlated with depression, and the sense of professional inefficacy was positively correlated with anxiety (25). Vasilopoulos (26) found that participants who reported a high level of social anxiety also reported a high level of burnout. Mark and Smith (27) revealed that job demands, external efforts, and over-commitment were related to increased anxiety levels. Burnout might be a risky factor for developing depression (28, 29). Therefore, job burnout may be used as a diagnostic standard to assess employees' mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression. Neuroticism, as a susceptible personality trait, is positively related to anxiety and depression, which means neurotic employees have higher tendency to experience job burnout. Research for firefighters, a particular group for our society, is critical but rare, especially for neurotic firefighters. Hence, our study took neurotic personality into account to establish models to explore how burnout can mediate the relationship between such personality and anxiety or depression.

The current study recruited 716 full-time male professional firefighters in China who voluntarily participated in this study. The mean age was 26.39 years old, and the average month of work experience is 31.08 within the final data. The ethics committees from all authors' universities approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from participants before they started.

The BFI-2 is a 60-item self-report measure of personality traits (30), and each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The BFI-2 consists of five subscales with 12 items each: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, negative emotionality (neuroticism), and open-mindedness. The higher scores on one trait, the more probable the subject has such trait.

A previous study indicated that the Chinese version of the BFI-2 questionnaire to evaluate personality traits has good reliability and structural validity (31). The current study showed good internal consistency, α = 0.74, 0.84, 0.85, 0.82, 0.76 for extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, negative emotionality (neuroticism) and open-mindedness, respectively.

Maslach and Schaufei's MBI-GS has a good validation across occupational groups and nations (32). The Chinese version (CMBI-GS) was revised by Li Chaoping (33). It consists of 15 items, and all were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = never, 7 = every day). The CMBI-GS composes of three subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. The higher the score of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and the lower score in reduced personal achievement, the higher the probability for the subject to have job burnout.

In this study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment were 0.92, 0.93, and 0.91, respectively.

Zung (34) and Zung (35) designed the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), respectively, to quantify the degree of anxiety and depression symptoms. These scales both include 20 self-report items (4-point Likert scale). Mean values were calculated. The higher the scores, the higher the inclination for the subject to have anxiety or depression.

The Chinese versions have been validated in epidemiological surveys (36, 37). The current study showed good internal consistency (α = 0.83, 0.85, respectively) for anxiety and depression.

The perceived organizational support (POS) was measured by using the 8-item scale (38). The short version of the POSS has been widely applied among Chinese occupational groups with good reliability and validity (39).

In the present study, the alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.70.

In the present study, all analyses were calculated in R 4.1.1 (40). Common method deviation tests, descriptive analyses, and normal distribution were performed using the psych package (41). The correlation matrix table was made by using the apaTables package (42). We conducted multiple-level mediation analysis by using the lavaan package (43) and visualized the pathway by the lavaanPlot package (44).

Neuroticism was regarded as an independent variable (IV). Depression and anxiety were set as dependent variables (DV). Job burnout consisted of three components: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DE), and reduced personal accomplishment (RPA), and they were regarded as mediation variables (MV). The moderation variable was the perceived organizational support (MDV: POS). Before analysis, we used G*Power 3.1 software (45) to calculate the sample size. The result showed that the minimum sample size should be 191 for path analysis with an effect size of 0.3 (46), and the degree of freedom was 3. In this study, we had a sample size of 716 firefighters, which is much more than the critical value.

The Harman single factor test showed that the eigenvalues of 18 factors were more outstanding than one without rotation, and the explanatory variation of the first factor was 23.56%, lower than the critical value of 40% (47). Therefore, there was no obvious common methodological bias in this study.

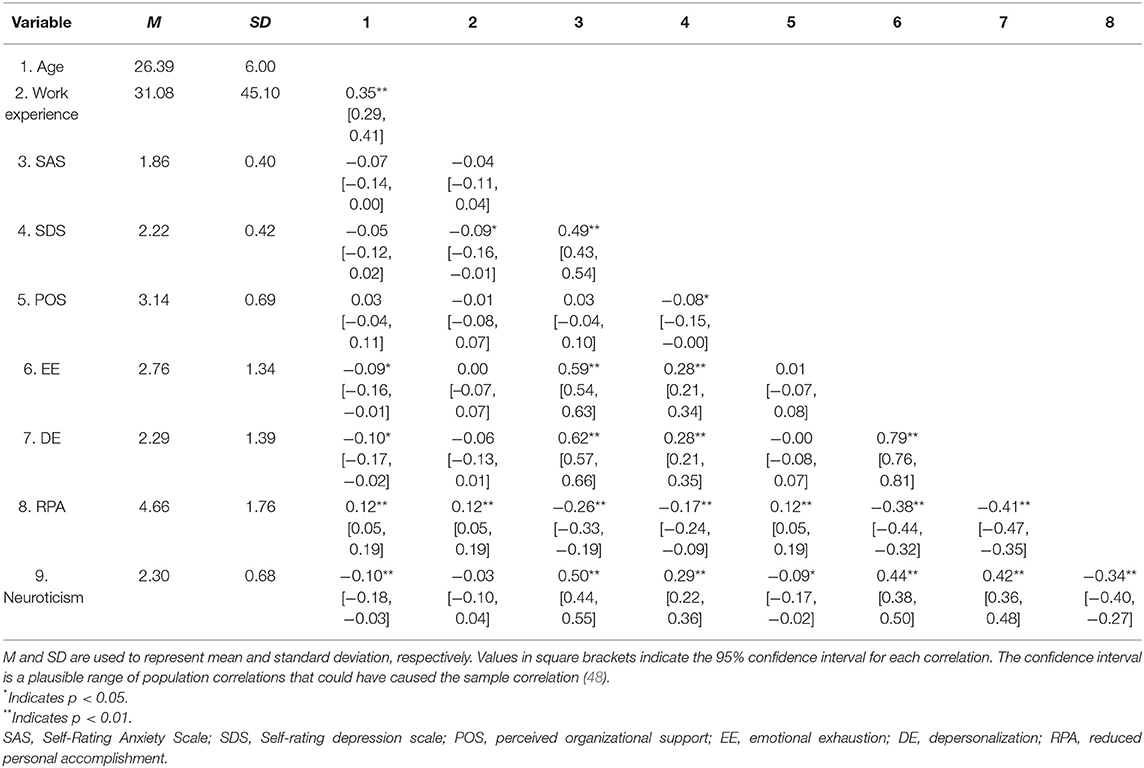

As Table 1 shows, the neuroticism trait was significantly positive correlated with anxiety (r = 0.50, p < 0.01) and depression (r = 0.29, p < 0.01). As expected, firefighters with higher neuroticism, anxiety and depression would experience more burnout (p < 0.01). The perceived organizational support was significantly negatively correlated with depression (r = 0.08, p < 0.05) and neuroticism (r = −0.09, p < 0.01), while it was not strongly correlated with anxiety (r = 0.03, p > 0.05). Age was significantly negatively correlated with the neuroticism trait (r = −0.10, p < 0.05).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations with confidence intervals for the main study variables.

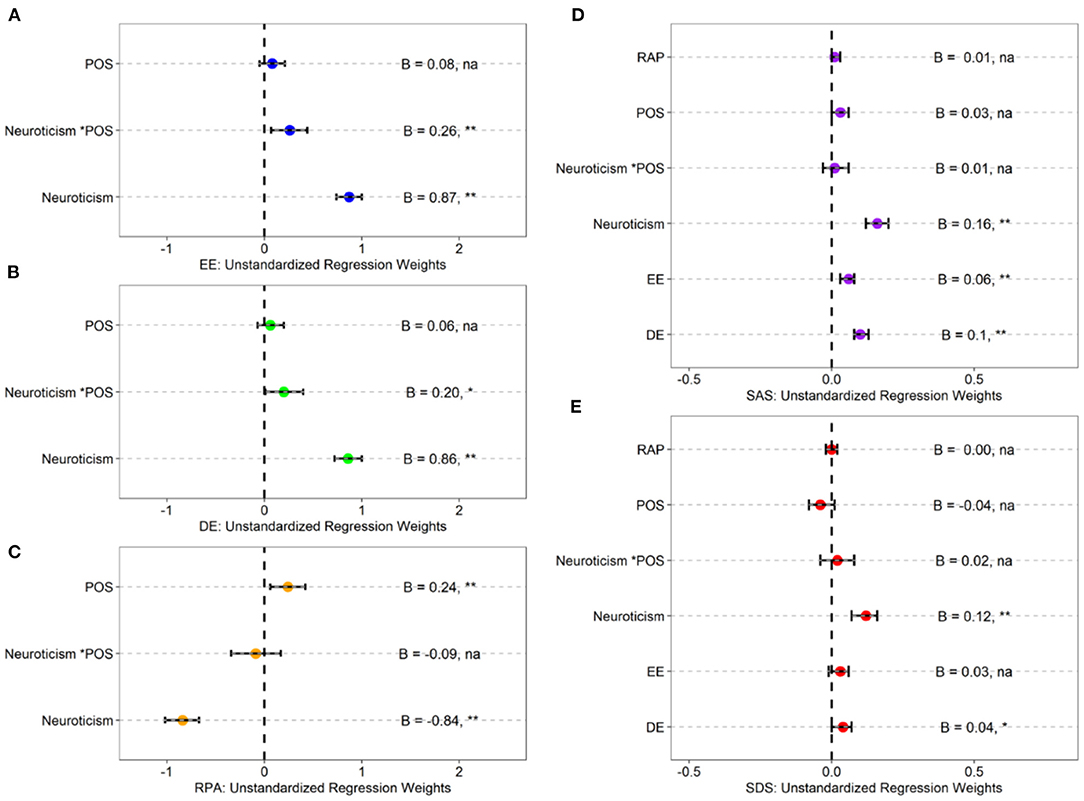

Corresponding with the multiple regression analysis (49) and following the recommendation by Aiken et al. (50), we mean-centered the two continuous variables (Neuroticism and POS) and tested the independent variable (Neuroticism), moderation variable (POS), and the interaction of independent and moderation variables (Neuroticism*POS) to predict mediation variables (EE, DE, RPA). The path analysis model was conducted, and overall fitness of the path model was acceptable {χ2/df = 41.03, p < 0.01; RMSEA = 0.24 [CI (0.20, 0.29)]; CFI = 0.95; GFI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.07}. Just as depicted in Tables 2, 3 illustrate the hypothetic model's unstandardized regression coefficients. Figure 1 shows the moderation results.

Figure 1. Unstandardized regression coefficients of the hypothesized model (N = 716). POS, perceived organizational support; EE, emotional exhaustion; DE, depersonalization; RPA, reduced personal accomplishment. (A) Indicates model 1. (B) Indicates model 2. (C) Indicates model 3. (D) Indicates model 4. (E) Indicates model 5. * indicates p < 0.05; ** indicates p < 0.01; na indicates p > 0.05.

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1, neuroticism (EE: B = 0.87, p < 0.01; DE: B = 0.86, p < 0.01) and Neuroticism*POS (B = 0.26, p < 0.01; DE: B = 0.20, p < 0.01) were reliable predictors of EE (Model 1) and DE (Model 2). Neuroticism was a negative predictor about RPA (B = −0.84, p < 0.01), while POS was a positive predictor (B = 0.24, p < 0.01). The interaction of neuroticism and POS was not significant (p > 0.05).

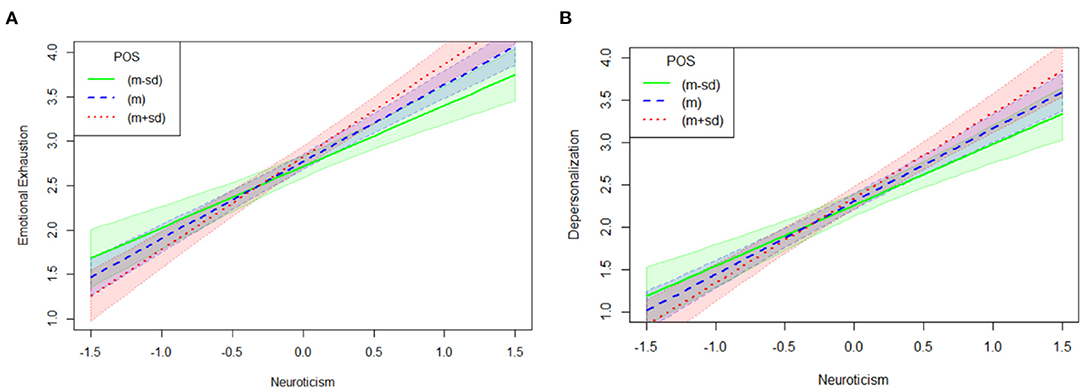

In terms with the statistical significance of the interaction between neuroticism and POS for emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, this result indicated that the association between neuroticism and emotional exhaustion increased in magnitude as the levels of POS increased from low [−1SD; β = 0.77, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (0.61, 0.92)] to moderate [Mean; β = 0.86, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (0.73, 0.99)] to high (+1SD; β = 0.99, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (0.84, 1.14)]. The positive relationship between neuroticism and emotional exhaustion was reinforced for the firefighters with higher levels of POS, which was an unexpected result (see Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Interaction of neuroticism and POS on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (N = 716). POS, perceived organizational support. (A) Indicates the interaction of neuroticism and POS on emotional exhaustion. (B) Shows the interaction of neuroticism and POS on depersonalization.

The results also indicated that the association between neuroticism and depersonalization increased in magnitude as the levels of POS increased from low [−1SD; β = 0.78, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (0.62, 0.94)] to moderate [Mean; β = 0.86, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (0.72, 0.99)] to high [+1SD; β = 0.96, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (0.80, 1.12)]. The positive relationship between neuroticism and depersonalization was reinforced for the firefighters with higher levels of perceived organizational support, which was an unexpected result (see Figure 2B).

The next step was to evaluate the mediating role of job burnout in the relationship between neuroticism and mental health (see Table 4). Results revealed that neuroticism positively predicted EE and DE (p < 0.01) and negatively predicted RPA (p < 0.01). The direct effect of neuroticism on anxiety (B = 0.16, p < 0.01) and depression (B = 0.12, p < 0.01) were significant.

The indirect association between neuroticism and anxiety through EE [β = 0.05, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (0.03, 0.07)] and DE [β = 0.09, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (0.07, 0.11)], was statistically significant, respectively. Similarly, the indirect association between neuroticism and depression through DE [β = 0.03, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (0.01, 0.05)], was statistically significant, respectively. The indirect role of RPA for anxiety and depression was not significant (p > 0.05).

Our results suggested that firefighters with the neurotic trait are more prone to experience anxiety and depression, which is consistent with the general population (12, 51). The relationship among neuroticism, depression and anxiety has been widely discussed (11, 52). Neuroticism is widely defined as a long-term tendency to experience negative emotions, especially when a person is threatened, depressed, or experiencing loss. High level of neuroticism results in skeptical emotional disorders and maladapted social or interpersonal relationships.

Inconsistent with our expectations, POS positively regulates the relationship between neuroticism and job burnout. For neurotic firefighters, the more organizational support they perceive can result in a higher level of burnout, especially in the dimensions of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. In China, firefighters are recruited from the army. Under such circumstances, once soldiers perceive that their organizations or commanders are concerned, they feel anxious instead of support. Supposedly, organizational structure and cultural differences lead to such a phenomenon. Therefore, perceived organizational support may have a reverse inhibitory effect on firefighters (53).

In line with the rich literature of previous studies, we found a strong correlation between burnout and anxiety, depressive symptoms. Interestingly, we found that depersonalization could mediate the relationship between neuroticism and both anxiety and depression. According to Melamed et al. (23), depersonalization is characterized by employees' tendency to regard others as objects. High level of depersonalization indicates that employees tend to be cynical, detached, or emotionally indifferent to colleagues and customers (i.e., rescuers and survivors) (54). Undertaking complex and heavy rescue tasks, firefighters experience many negative events frequently, which can easily lead to mental problems and emotional disorders.

Moreover, incorrectly understanding the will of organizations might worsen the situation. In sum, our study did well in researching the relationship between the neuroticism trait and mental health by considering the moderating role of POS and the mediating role of the three components of burnout among Chinese firefighters. Thereby current study can reveal some facts about the mental health condition of firefighters in China. Also, leaders or decision-makers can take action in terms of our models.

Some limitations in this study should be noted. First, our analysis does not infer causality between variables as in all the cross-sectional designs. Though we found the indirect association between neuroticism and anxiety through EE and DE was significant, DE played an indirect role through neuroticism to depression. In future research, network analysis (55) may be an excellent choice to explore the causality among main variables.

Second, we rely on the “subjective” measurement of anxiety and depression and occupational level variables. Some firefighters were mentally defensive in post-survey interviews though we repeatedly told them that this study was confidential and no results would be given to their senior commanders. This situation required us to use “objective” indicators (i.e., indicators that do not involve the perception or evaluation of respondents) to reduce the impact of various response deviations (such as social expectation deviation) (56).

Reducing firefighters' job burnout can benefit their physical and mental health and our society. Hence, it is crucial to explore the mediating mechanisms of job burnout influencing mental health, especially considering the moderating role of perceived organizational support among firefighters.

Our findings demonstrated that neuroticism traits influenced anxiety and depression through job burnout, and the role of perceived organizational support moderated the effects of neuroticism on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in the same direction. Future research should explore other contextual and individual mediators and moderators of the relationship between firefighters' personality traits and mental health to clarify the matter further.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by School of Psychology, Nanjing Normal University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

CS: study design. LZ and CL: data collection. YT: analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. ZM, WH, and YZ: critical revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

This study was supported by the Second station of the special service brigade, fire rescue detachment in Suzhou. The authors thank Hao Wu, who helped with the recruitment of subjects.

1. Hu Y, Shao J-z. Chinese Firefighter Fatalities 2007–2016. Taipei: Asia-Oceania Symposium on Fire Science and Technology (2018).

2. Chen XJ, Zhang LS, Peng ZK, Chen SX. Factors influencing the mental health of firefighters in Shantou City, China. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2020) 13:529–36. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S249650

3. Stanley IH, Hom MA, Spencer-Thomas S, Joiner TE. Examining anxiety sensitivity as a mediator of the association between PTSD symptoms and suicide risk among women firefighters. J Anxiety Disord. (2017) 50:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.06.003

4. Straud C, Henderson SN, Vega L, Black R, Van Hasselt V. Resiliency and posttraumatic stress symptoms in firefighter paramedics: the mediating role of depression, anxiety, and sleep. Traumatology. (2018) 24:140. doi: 10.1037/trm0000142

5. Gramlich MA, Neer SM. Firefighter-paramedic with posttraumatic stress disorder, horrific images, and depression: a clinical case study. Clin Case Stud. (2018) 17:150–65. doi: 10.1177/1534650118770792

6. Gulliver SB, Zimering RT, Knight J, Morissette SB, Kamholz BW, Pennington ML, et al. A prospective study of firefighters' PTSD and depression symptoms: The first 3 years of service. Psychol Tauma Theory Res Pract Policy. (2021) 13:44. doi: 10.1037/tra0000980

7. Enns MW, Cox BJ. Personality dimensions and depression: review and commentary. Can J Psychiatry. (1997) 42:274–84. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200305

8. Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S. Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. (1994) 103:103–16. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.103.1.103

9. Eysenck HJ. Neuroticism, anxiety, and depression. Psychol Inq. (1991) 2:75–6. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0201_17

10. Rusting CL, Larsen RJ. Diurnal patterns of unpleasant mood: associations with neuroticism, depression, and anxiety. J Pers. (1998) 66:85–103. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00004

11. Weinstock LM, Whisman MA. Neuroticism as a common feature of the depressive and anxiety disorders: a test of the revised integrative hierarchical model in a national sample. J Abnorm Psychol. (2006) 115:68. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.68

12. Williams AL, Craske MG, Mineka S, Zinbarg RE. Neuroticism and the longitudinal trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms in older adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. (2021) 130:126. doi: 10.1037/abn0000638

13. Boyce P, Parker G, Barnett B, Cooney M, Smith F. Personality as a vulnerability factor to depression. Br J Psychiatry. (1991) 159:106–14. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.1.106

14. Kendler KS, Kuhn J, Prescott CA. The interrelationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. (2004) 161:631–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.631

15. Hunt C, Slade T, Andrews G. Generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder comorbidity in the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Depress Anxiety. (2004) 20:23–31. doi: 10.1002/da.20019

16. Twenge JM. The age of anxiety? The birth cohort change in anxiety and neuroticism, 1952–1993. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2000) 79:1007. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.1007

17. Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Sava D. Perceived organisational support. J Appl Psychol. (1986) 71:500–7. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

18. Xu Z, Yang F. The impact of perceived organizational support on the relationship between job stress and burnout: a mediating or moderating role? Curr Psychol. (2021) 40:402–13. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9941-4

19. Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. (1985) 98:310–57. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

20. George JM, Reed TF, Ballard KA, Colin J, Fielding J. Contact with AIDS patients as a source of work-related distress: effects of organizational and social support. Acad Manag J. (1993) 36:157–71. doi: 10.5465/256516

21. Shirom A, Melamed S. A comparison of the construct validity of two burnout measures in two groups of professionals. Int J Stress Manag. (2006) 13:176–200. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.13.2.176

22. Bianchi R, Mayor E, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E. Burnout and depressive symptoms are not primarily linked to perceived organizational problems. Psychol Health Med. (2018) 23:1094–105. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2018.1476725

23. Melamed S, Shirom A, Toker S, Berliner S, Shapira I. Burnout and risk of cardiovascular disease: evidence, possible causal paths, and promising research directions. Psychol Bull. (2006) 132:327–53. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.327

24. Liu L, Chang Y, Fu J, Wang J, Wang L. The mediating role of psychological capital on the association between occupational stress and depressive symptoms among Chinese physicians: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-219

25. Golonka K, Mojsa-Kaja J, Blukacz M, Gawłowska M, Marek T. Occupational burnout and its overlapping effect with depression and anxiety. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. (2019) 19:229–44. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01323

26. Vasilopoulos S. Job burnout and its relation tosocial anxiety in primary school teachers. Hellenic J Psychol. (2012) 9:18–44.

27. Mark G, Smith AP. Occupational stress, job characteristics, coping, and the mental health of nurses. Br J Health Psychol. (2012) 17:505–21. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02051.x

28. Kaschka WP, Korczak D, Broich K. Burnout: a fashionable diagnosis. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int. (2011) 108:781–7. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0781

29. Koutsimani P, Montgomery A, Georganta K. The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:284. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284

30. Soto CJ, John OP. The next big five inventory (BFI-2): developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2017) 113:117. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000096

31. Zhang B, Li YM, Li J, Luo J, Ye Y, Yin L, et al. The big five inventory−2 in China: a comprehensive psychometric evaluation in four diverse samples. Assessment. (2021) 1–23. doi: 10.1177/10731911211008245

32. Schutte N, Toppinen S, Kalimo R, Schaufeli W. The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) across occupational groups and nations. J Occup Organ Psychol. (2000) 73:53–66. doi: 10.1348/096317900166877

33. Li Chaoping S-k. The influence of distributive justice and procedural justice on job burnout. Acta Psychol Sinica. (2003) 35:677.

34. Zung W. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1965) 12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008

35. Zung W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosom J Consul Liaison Psychiatry. (1971) 12:371–9. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0

36. Leung K, Lue B, Lee M-B, Tang L. Screening of depression in patients with chronic medical diseases in a primary care setting. Fam Pract. (1998) 15:67–75. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.1.67

37. Liu X, Oda S, Peng X, Asai K. Life events and anxiety in Chinese medical students. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (1997) 32:63–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00788922

38. Hekman DR, Bigley GA, Steensma HK, Hereford JF. Combined effects of organizational and professional identification on the reciprocity dynamic for professional employees. Acad Manag J. (2009) 52:506–26. doi: 10.5465/amj.2009.41330897

39. Shen J, Benson J. When CSR is a social norm: how socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. J Manage. (2016) 42:1723–46. doi: 10.1177/0149206314522300

40. R Core Team. R: A Language Environment for Statistical Computing (R version 4.1.1). R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2021). Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed March 10, 2022).

41. Revelle W. psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, Personality Research. R package version 2.1.6. (2021). Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accessed March 19, 2021).

42. Stanley D. apaTables: Create American Psychological Association (APA) Style Tables. R package version 2.0.8. (2021). Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=apaTables (accessed January 4, 2021).

43. Rosseel Y. lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. (2012) 48:1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

44. Lishinski A. lavaanPlot: Path Diagrams for ‘Lavaan' Models via ‘DiagrammeR'. R package version 0.6.2. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lavaanPlot (accessed August 13, 2021).

45. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. (2009) 41:1149–60. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

46. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Academic Press (1969).

47. Podsakoff N. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. (2003) 885:1037. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

48. Cumming G. The new statistics: why and how. Psychol Sci. (2014) 25:7–29. doi: 10.1177/0956797613504966

49. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Publications (2017).

50. Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (1991).

51. Shokrkon A, Nicoladis E. How personality traits of neuroticism and extroversion predict the effects of the COVID-19 on the mental health of Canadians. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0251097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251097

52. Pereira-Morales AJ, Adan A, Forero DA. Perceived stress as a mediator of the relationship between neuroticism and depression and anxiety symptoms. Curr Psychol. (2019) 38:66–74. doi: 10.1007/s12144-017-9587-7

53. Varvel SJ, He Y, Shannon JK, Tager D, Bledman RA, Chaichanasakul A, et al. Multidimensional, threshold effects of social support in firefighters: is more support invariably better? J Couns Psychol. (2007) 54:458. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.4.458

54. Garden A-M. Depersonalization: a valid dimension of burnout? Hum Relat. (1987) 40:545–59. doi: 10.1177/001872678704000901

55. Borsboom D, Cramer AO. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2013) 9:91–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608

Keywords: neuroticism, job burnout, perceived organization support, anxiety, depression

Citation: Tao Y, Ma Z, Hou W, Zhu Y, Zhang L, Li C and Shi C (2022) Neuroticism Trait and Mental Health Among Chinese Firefighters: The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support and the Mediating Role of Burnout—A Path Analysis. Front. Public Health 10:870772. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.870772

Received: 07 February 2022; Accepted: 18 March 2022;

Published: 05 April 2022.

Edited by:

Luigi Vimercati, University of Bari Aldo Moro, ItalyReviewed by:

Nina Rajovic, University of Belgrade, SerbiaCopyright © 2022 Tao, Ma, Hou, Zhu, Zhang, Li and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Congying Shi, c2hpY29uZ3lpbmcxMDE5QDE2My5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.