- 1School of Public Health, Institute for Human Rights, Southeast University, Nanjing, China

- 2Department of Humanities, South East Technological University, Carlow, Ireland

- 3Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Nottingham Ningbo China, Ningbo, China

- 4Network for Education and Research on Peace and Sustainability (NERPS), Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan

- 5Prime Institute of Public Health, Peshawar Medical College, Peshawar, Pakistan

- 6Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sarajevo, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 7School of Public Health, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 8China Institute for Urban Governance, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

Introduction: Domestic violence is toxic to society. With approximately one in three women on average falling victim to domestic violence, systematic solutions are needed. To further complicate the issue, mounting research shows that COVID-19 has further exacerbated domestic violence across the world. Situations could be even more pronounced in countries like China, where though domestic violence is prevalent, there is a dearth of research, such as intervention studies, to address the issue. This study investigates key barriers to domestic violence research development in China, with a close focus on salient cultural influences.

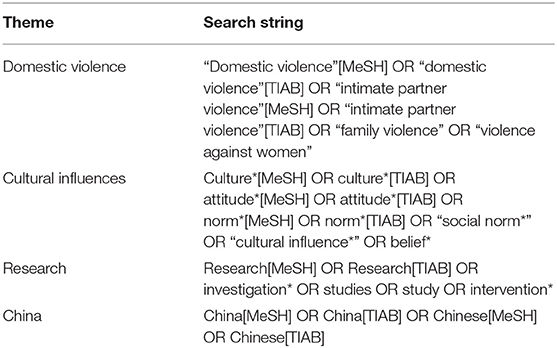

Methods: A review of the literature on domestic violence in China in PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus was conducted to answer the research question. The search was focused on three themes, domestic violence, China, research, and cultural influences.

Results: The study findings show that categorizing domestic violence as a “family affair” is a key barrier to domestic violence research development in China—an incremental hindrance that prevents the public and policymakers from understanding the full scale and scope of domestic violence in China. In addition to abusers, witnesses, and victims, even law enforcement in China often dismisses domestic violence crimes as “family affairs” that resides outside the reach and realm of the law. The results indicated that mistreating domestic violence crimes as “family affairs” is a vital manifestation of the deep-rooted cultural influences in China, ranging from traditional Confucian beliefs in social harmony to the assumed social norms of not interfering with other people's businesses.

Conclusion: Domestic violence corrupts public health and social stability. Our study found that dismissing domestic violence cases as “family affairs” is an incremental reason why China's domestic violence research is scarce and awareness is low. In light of the government's voiced support for women's rights, we call for the Chinese government to develop effective interventions to timely and effectively address the domestic violence epidemic in China.

Introduction

Domestic violence is toxic to society. Domestic violence or violence against women could be understood as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life” (1). Domestic violence not only has a devastating effect on personal and public health, it is also a constant threat to social stability and global solidarity (2). On an individual level, mounting research shows that domestic violence could result in long-term damages to people's physical and psychological health (3–8). On a global level, data from the World Health Organization show that one in every three women falls victim to domestic violence (2).

However, due to a lack of research, there is a shortage of up-to-date and systematic investigations of domestic violence in developing countries. What is clear, though, is that currently available research paints a dire picture. A systematic review study that pooled all published papers conducted in low- and middle-income countries indicates that, for instance, lifetime intimate partner violence against women was as prevalent as 55% (9). Additional compounding factors are also present. As seen amid the pandemic, partially due to issues such as prolonged time spent with the abusers, deteriorated financial stability, and disrupted local and national support programs, COVID-19 has further exacerbated domestic violence worldwide (10–12). In the early days of the pandemic, for instance, police records show that in Jianli city, Hubei Province, China, there was a three-fold hike of domestic violence cases influenced heavily by the pandemic and its prevention measures (e.g., lockdowns) (13).

While similar trends are also present in developed countries, what is unique about domestic violence in countries like China is that the victims often face the dual burden of lack of systematic awareness at the societal level (i.e., dearth of timely and quality research) and have limited timely and systematic support from society. Traditionally, a key solution to address domestic violence has been via effective intervention programs, ranging from researchers-led programs, non-profit organizations initiated support groups, local government-sponsored hotlines, or state-funded safe houses (14). However, these interventions are often poorly developed in countries such as China (15), where there is a pronounced dearth of research on domestic violence and a lack of solutions to which victims could turn for help. In other words, though domestic violence's prevalence in China has long been established —similar if not worse than the global average (i.e., 34%) (16), domestic violence research and interventions in China are often rudimentary and of suboptimal priority (17).

This lack of priority is also reflected in police officers' attitudes toward domestic violence cases in China. In a study on 623 police officers in China, for instance, researchers found that nearly half of law enforcement personnel (i.e., 46.5%) are likely to not make arrests of domestic violence abusers, regardless of the severity of the violence (18). These insights combined, overall, further underscore the imperative for in-depth and comprehensive research on domestic violence in China, which in turn, could raise the awareness of domestic violence across society and help government and health officials to develop evidence-based intervention programs to eliminate, if not eradicate, domestic violence in China. However, to date, there is a dearth of investigations on factors that negatively influence the research development on domestic violence in China, particularly in light of the unique insights exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic (15). Thus, to bridge the research gaps, this study aims to examine the key barriers to domestic violence research development in China, with a close focus on salient cultural influences.

Methods

A review of the literature on domestic violence research in China in PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus was conducted to answer the study question. In the context of this study, barriers to domestic violence research development in China were operationalized as incremental links that prevent the public and the policymakers from understanding the scale and scope of domestic violence in China. While a number of cultural influences and social norms could shape domestic violence in China, we only focused on the most salient factors (e.g., most cited) identified in academic literature. The narrative literature review approach was adopted as the review framework, which could be understood as “an objective, thorough summary and critical analysis of the relevant available research and non-research literature on the topic being studied” (19). One key advantage of the narrative literature review approach is that it could help the researchers gain a structured understanding of the literature in an effective manner (19).

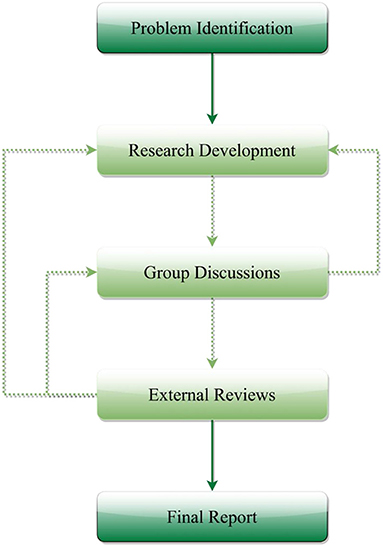

The search was focused on four themes, domestic violence, China, research, and cultural influences. Though domestic violence could happen to both men and women (20), as women are often the predominant gender in domestic violence victims, our study focused on female domestic violence. An example PubMed search term could be found in Table 1. The search was first conducted on May 25, 2021, with the follow-up review completed on December 28, 2021. A schematic representation of the research flow could be found in Figure 1. Scholarly papers were excluded if they: (1) were not published in English, (2) were not focused on domestic violence research on women, and (3) could not provide key insights on the influences of cultural or social norms on domestic violence in China. To ensure up-to-date insights could be considered to help contextualize the findings and white papers were also reviewed and analyzed.

Results

Of the total number of articles included in the review and subsequent analysis (N = 21), the vast majority were published within the last 5 years (n = 12), and adopted various methodological approaches. Some of the reviewed studies used qualitative approaches investigated domestic violence in the context of family experiences [e.g., (21)] or a series of interviews with males (n = 18) who had used violence against their partner [e.g., (22)]; while others adopted more quantitative approaches, such as cross-sectional designs with large groups of participants [e.g., (23, 24)], or a pre-post experimental design with police officers (N=401) in evaluating changing attitudes toward domestic violence [e.g., (25)]. Detailed information on the list of articles reviewed could be found in Table 2.

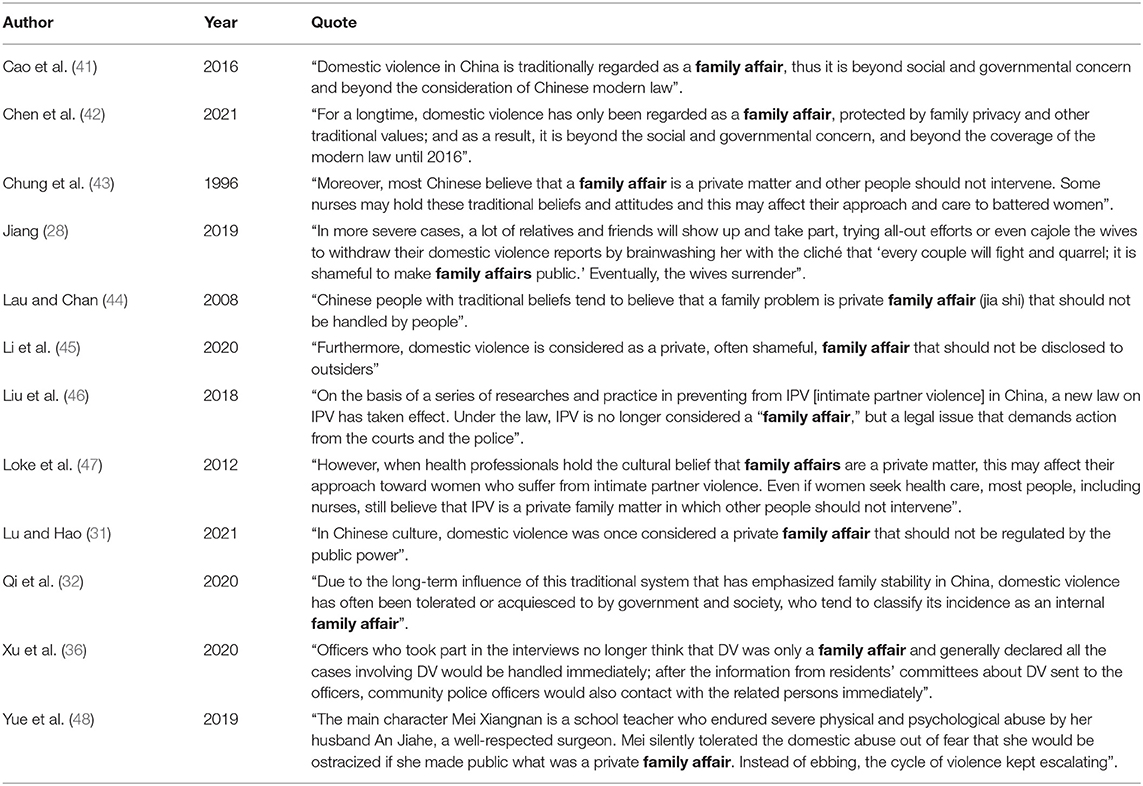

The study findings show that categorizing domestic violence as a “family affair” is a key barrier to domestic violence research development in China—an incremental hindrance that prevents the public and policymakers from understanding the full scale and scope of domestic violence in China. In addition to abusers, witnesses, and victims, even law enforcement in China often dismisses domestic violence crimes as “family affairs” that reside outside the reach and realm of the law [e.g., (36)]. The results indicated that mistreating domestic violence crimes as “family affairs” is a vital manifestation of the deep-rooted cultural influences in China, ranging from traditional Confucian beliefs in social harmony to the assumed social norms of not interfering with other people's businesses [e.g., (27)]. A list of exemplary quotes could be found in Table 3.

Discussion

This study set out to investigate key barriers to domestic violence research development in China, with a close focus on salient cultural influences. Our research is the first that explored barriers that hinder the public and policymakers' understanding of the full scale and scope of domestic violence in China. While many factors shape the lack of domestic violence research in China, we focused on salient cultural influences that are most discussed in published academic papers. The study findings show that, by diminishing domestic violence crimes into “private” “family affairs”, cultural and social norms play a defining role in shaping the domestic violence narrative and public awareness of the topic in China (27). The results also indicate that almost all key stakeholders, ranging from abusers, witnesses, families and friends, victims, to police officers, often dismiss domestic violence crimes as matters of “family affairs” that reside outside the reach and realm of the law [e.g., (24, 28, 47)]. These sobering insights combined, in turn, shed light on why the current research development is insufficient to inform the public and policymakers about the full scale and scope of domestic violence in China.

Domestic Violence as a “Family Affair”

Our findings show that categorizing domestic violence as a “family affair” is a critical barrier to domestic violence research development in China—an incremental hindrance that prevents the public and policymakers from understanding the prevalence, severity, and repercussions of domestic violence in China. In light of the human and economic tolls associated with domestic violence, the public nature of domestic violence crimes, as indicated in its impacts on all sectors of societies, as opposed to limiting it as “private” and “family affairs”, is abundantly evident (49–53). Analyses conducted in the United States in 2014, for instance, show that domestic violence lifetime cost was $103,767 per female victim and $23,414 for individual male victims, paired with the fact that 43 million U.S. adults are victims of domestic violence, the total cost of domestic violence on society could amount to $3.6 trillion over victims' lifetime (54). However, due to poor research development, it is unclear in terms of what might be the totality of the human and economic toll of domestic violence in China, let alone insights that factor in the most up-to-date impacts of COVID-19 on the scale, scope, and severity of domestic violence in the country.

What is clear, though, is China has nearly four times the U.S.'s population (55), and lacks the domestic violence prevention infrastructure that is available in developed countries such as the U.S. (56–58), critical intervention mechanisms that have the potential to help victims fend off the adverse impacts of domestic violence. These insights combined, in turn, further underscore the problematic nature of the research gap. Without essentials such as domestic violence crime reporting, monitoring, and surveillance, basic understanding such as what are the impacts of domestic violence on avoidable medical experiences, workforce productivity lost, and long-term social stability could not be achieved. Needless to say, without these understandings, government and health officials may not be able to evaluate, let alone prevent, the repercussions of domestic violence as an overlooked public health epidemic on the health and wellbeing of the society at large.

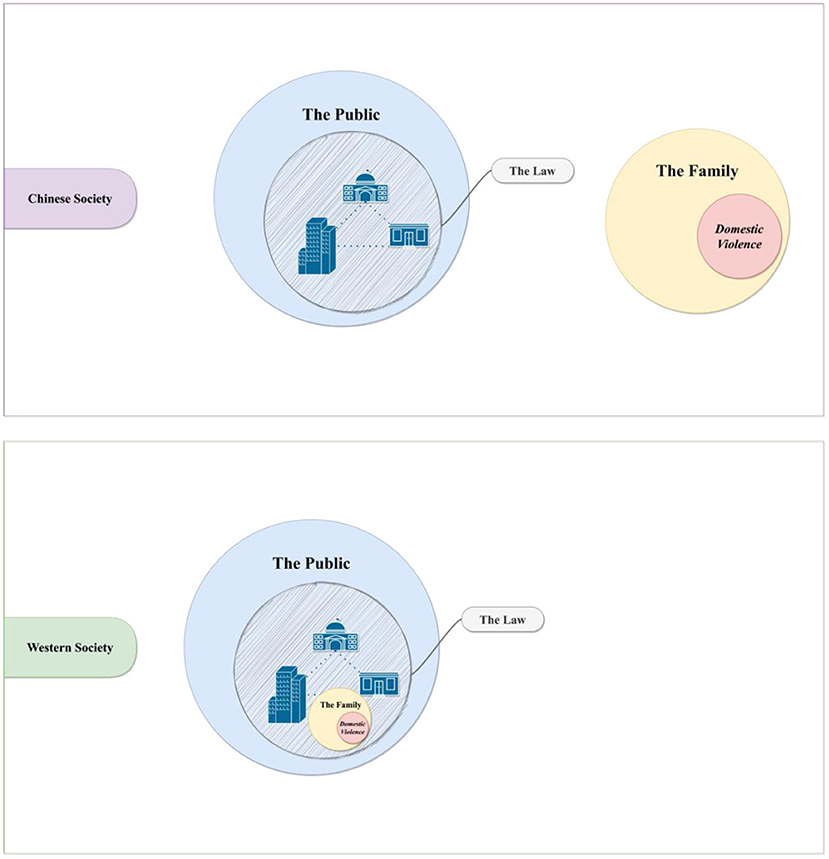

It is important to note that dismissing domestic violence crimes as matters of “family affairs” is not a phenomenon that is unique to China. Many societies, for instance, either due to population makeup or geographical proximity to China, also face the issue (59–63). Furthermore, cultures that are often influenced by traditional or conventional social beliefs, such as the Arab world, also found that “family affairs” could be a frequent excuse cited by abusers for their crimes and a salient barrier that prevents victims from seeking help (64–66). However, what is unique about categorizing domestic violence crimes as “family affairs” in China centers on its prevalence and pervasiveness. The study findings show that, in addition to abusers, witnesses, and victims, even law enforcement in China often dismisses domestic violence crimes as “family affairs” that reside outside the reach and realm of the law (40, 45, 67). A schematic representation of the unique categorization of domestic violence in Chinese society, as found in our analyses, could be seen in Figure 2.

In a study on accident and emergency nurses in Hong Kong, researchers found that 43% of the participants do not believe they have a duty to intervene in violence domestic cases (43). What is equally, if not more, alarming, is that in the same study, among all of the 57% of nurses who indicated they should intervene, all of them endorsed the traditional Chinese saying— “even a good judge cannot adjudicate family disputes” (43). Similar patterns—failing to help domestic violence victims per their job descriptions and the requirement of the law—are also found in other stakeholders (47). These insights combined suggest that in order to fundamentally change this corrosive practice of labeling domestic violence crimes as “family affairs”, systematical measures led by government and health officials are needed urgently.

A Social Ecological Approach

One way to effectively change the cultural influences and social norms associated with equating domestic violence as a “family affair” is via addressing the issue from a social ecological perspective (68). The social ecological model suggests that public behaviors are often shaped by various influences with different levels of social implications. These influences could often be grouped into the intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy level factors (68). Drawing insights from the social ecological model, we propose a government-led, community-facilitated, organization-sponsored, and individual-responsible approach to address the deep-rooted cultural and social influences on domestic violence in China.

Change the “Family Affair” Narrative

It is important to underscore that, as evidenced in behavioral sciences literature (69–71), referencing domestic violence as a “family affair” could reduce the perceived severity and create a climate of complacency in society. To effectively address this issue, media professionals, health organizations, and perhaps most importantly, government agencies need to take a more significant role in changing the narrative surrounding domestic violence. Government agencies, for instance, especially those involved in or associated with law enforcement, need to set the example of banning the misleading use of “family affair” in formal and informal reference to domestic violence. Persuasive health campaign interventions could also help change the narrative. Health campaign interventions can be understood as using communication or marketing tools and techniques to change the target audience's attitudes and behavior toward a health phenomenon (72). As the literature suggests, health campaign interventions are effective in shifting culture and social norms around a social phenomenon (72–76). Considering that the association between domestic violence and “family affair” is deeply rooted in the Chinese culture, the government must initiate health campaign interventions tailored to social norms around the “family affair” phenomenon (77–79).

Improve Women's Financial Autonomy

It is important to note that the Chinese government has been making progress in improving women's rights. In a Lancet study on Chinese women's overall health and quality of life development, ample evidence shows that substantial strides were made in the past 70 years (80). However, ingrained issues may need the government's sustained intervention to address. For instance, though China's gender wage gap has been relatively low compared to countries such as the U.S. (81), it has been on the rise (82). Recurring evidence shows that financial capabilities are often closely linked to women's susceptibility to domestic violence (83). In other words, it is possible that financial autonomy has the potential to help women think and live above submissive culture patterns (84), such as cultural influences that translate domestic violence crimes into “family affairs”. These insights combined suggest that addressing the gender wage gap in China could be a key strategy that the Chinese government could adopt to mitigate domestic violence.

Interventions That Hold Individuals Responsible

Another critical intervention that policymakers should consider is improving the utility and functionality of the 2016 Anti-Domestic Violence Law in China, implementation of which has been lax among law enforcement personnel (32, 85, 86). In addition to traditional intervention programs designed for abusers (e.g., training or rehabilitation opportunities) (87), another way to address this issue is via incorporating domestic violence abuser history for the past 5 years as a part of individuals'—both male and female job seekers—eligibility for applying for and working at the public sectors. In other words, people with a record of domestic violence crimes for the past 5 years should not be allowed to apply for working as public servants, vital personnel who might be exposed to tasks that are inappropriate for abusers, such as domestic violence victims relocation.

A key advantage of this program centers on its non-judgmental attitude toward whether domestic violence crimes are “family affairs”. Essentially, the proposed intervention approach aims to address domestic violence at the behavioral level, as opposed to the belief level—regardless of which belief systems the abusers hold or how conventional their views toward family or women might be (88–90), if they commit domestic violence crimes for the past 5 years, they should not be allowed in desirable and high-stake jobs like pubic servants. Needless to say, due to its novelty—no such interventions have been previously deployed in China, rigorous and evidence-based development processes are needed to ensure this intervention has the potential to reach the desirable intervention outcome—reduce domestic violence prevalence in China in scale. In the same vein, the central government should also make abilities to implement the Anti-Domestic Violence Law a key capacity of the local governments. As a matter of fact, Changsha, the capital city of Hunan Province, China, has already made domestic violence prevention a key component of their performance assessment rubric—effectively making abilities to prevent domestic violence a part of public officials' job descriptions (91). Overall, the promises of these approaches center on their potential to incentivize both individuals and local governments to invest in domestic violence prevention efforts on a daily basis.

Community-Facilitated Collaborative Interventions

In addition to incentivizing current or formal domestic violence abusers to not commit domestic violence crimes via potential career prospects and job opportunities, limiting these perpetrators' access to victims or opportunities to inflict harm may also be a practical approach. For instance, making domestic violence history searchable in the national marriage registry free of charge could help women avoid being exposed to these abusers. To further incentivize abusers to refrain from harming their current or formal intimate partners, making the records “dormant” if the perpetrators are able to manage to not commit domestic violence for 5 years could be another effective behavior nudge. Currently, Yiwu, a southern city in China, has already made such a searchable digital system available city-wide (92). Overall, this big data-based domestic violence surveillance and monitoring mechanism have the potential to engage all stakeholders, ranging from victims, families and friends, community members, city officials, health experts, to abusers, in curbing and controlling domestic violence crimes across sectors of societies.

Limitations

While our study bridges important research gaps, it is not without limitations. First, the narrative review approach was adopted to gauge the research question. While a narrative review could be a key step in determining the suitability of systematic reviews, the non-systematic nature of the research method nonetheless limits the study results' reproducibility and replicability (93). Furthermore, we only reviewed scholarly literature published in English. As our key research objective is to gauge the scale and scope of academic work available on domestic violence in China, this decision is well-justified. However, by doing this, it is possible that insights published in Chinese or other languages in non-academic venues are not presented in this study. To address these issues, future research could adopt the systematic review approach to examine the research question with a search that is both broad and comprehensive.

Conclusion

Domestic violence endangers public health and social stability. Our study found that dismissing domestic violence crimes as “family affairs” is a key reason why China's domestic violence research is scarce and awareness is low. In light of the government's voiced support for women's rights, we call for the Chinese government to develop effective interventions to timely and effectively address the domestic violence epidemic in China. To further shed light on the issue, future research could develop interventions that target the corrosive practice of treating domestic violence in China as a “family affair” to further improve women's health and quality of life, public health and wellbeing, social stability, as well as global solidarity.

Author Contributions

ZS developed the research idea and drafted the manuscript. DM, AC, JA, HC, SŠ, and YC reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Institute of College Student Development, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (grant number DFY-SJ-2021055).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We wishes to express her gratitude to the editor and reviewers for their constructive input.

References

1. World Health Organization (2021). Violence against women. Available online at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/violence-against-women#tab=tab_1 (accessed December 12, 2021).

2. World Health Organization (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and nonpartner sexual violence. Available online at: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en/ (accessed December 12, 2021).

3. Bradbury-Jones C, Isham L. The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:2047–9. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15296

4. Guo J, Fu M, Liu D, Zhang B, Wang X, van IJzendoorn MH. Is the psychological impact of exposure to COVID-19 stronger in adolescents with pre-pandemic maltreatment experiences? A survey of rural Chinese adolescents. Child Abuse Neglect. (2020) 110:104667. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104667

5. Han SD, Mosqueda L. Elder abuse in the COVID-19 era. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2020) 68:1386–7. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16496

6. Usher K, Bhullar N, Durkin J, Gyamfi N, Jackson D. Family violence and COVID-19: increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2020) 29:549–52. doi: 10.1111/inm.12735

7. van Gelder N, Peterman A, Potts A, O'Donnell M, Thompson K, Shah N, et al. COVID-19: reducing the risk of infection might increase the risk of intimate partner violence. EClinicalMedicine. (2020) 21:100348–100348. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100348

8. World Health Organization (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on mental, neurological and substance use services. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924012455 (accessed December 12, 2021).

9. Semahegn A, Torpey K, Manu A, Assefa N, Tesfaye G, Ankomah A. Are interventions focused on gender-norms effective in preventing domestic violence against women in low and lower-middle income countries? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health. (2019) 16:93. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0726-5

10. Anurudran A, Yared L, Comrie C, Harrison K, Burke T. Domestic violence amid COVID-19. Int J Gynecol Obstetr. (2020) 150:255–6. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13247

11. Bouillon-Minois J-B, Clinchamps M, Dutheil F. Coronavirus and quarantine: catalysts of domestic violence. Violence Against Women. (2020) 1077801220935194. doi: 10.1177/1077801220935194

12. Cowling P, Forsyth A. Huge rise in domestic abuse cases being dropped in England and Wales. (2021). Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-58910802 (accessed December 12, 2021).

13. Allen-Ebrahimian B. (2020). China's domestic violence epidemic. Available online at: https://www.axios.com/china-domestic-violence-coronavirus-quarantine-7b00c3ba-35bc-4d16-afdd-b76ecfb28882.html (accessed December 12, 2021).

14. World Health Organization (2010). Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. Geneva, Switzerland. Available online at: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/violence/9789241564007_eng.pdf (accessed December 12, 2021).

15. Su Z, McDonnell D, Roth S, Li Q, Šegalo S, Shi F, et al. Mental health solutions for domestic violence victims amid COVID-19: A review of the literature. Global Health. (2021) 17:67. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00710-7

16. Parish WL, Wang T, Laumann EO, Pan S, Luo Y. Intimate partner violence in China: national prevalence, risk factors and associated health problems. Int Fam Plan Perspect. (2004) 30:174–81. doi: 10.1363/3017404

17. Zhang H, Zhao R. Empirical research on domestic violence in contemporary China: continuity and advances. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. (2018) 62:4879–87. doi: 10.1177/0306624X18801468

18. Lin K, Sun IY, Wu Y, Xue J. Chinese police officers' attitudes toward domestic violence interventions: do training and knowledge of the anti-domestic violence law matter? Policing and Society. (2021) 31:878–94. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2020.1797027

19. Cronin P, Ryan F, Coughlan M. Undertaking a literature review: a step-by-step approach. Br J Nurs. (2008) 17:38–43. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.1.28059

20. World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed December 12, 2021).

21. Tsun AO-K, Lui-Tsang PS-K. Violence against wives and children in Hong Kong. J Fam Econ Issues. (2005) 26:465–86. doi: 10.1007/s10834-005-7845-6

22. Chan KL. The Chinese concept of face and violence against women. Int Soc Work. (2006) 49:65–73. doi: 10.1177/0020872806059402

23. Ko Ling C, Brownridge DA, Tiwari A, Fong DYT, Leung W-C. Understanding violence against Chinese women in Hong Kong: an analysis of risk factors with a special emphasis on the role of in-law conflict. Violence Against Women. (2008) 14:1295–312. doi: 10.1177/1077801208325088

24. Wang X, Wu Y, Li L, Xue J. Police officers' preferences for gender-based responding to domestic violence in China. J Family Viol. (2021) 36:695–707. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00237-2

25. Hayes BE, Connolly EJ, Wang X, Mason M, Ingham C. Chinese police cadets' attitudes toward domestic violence: a pretest/posttest design. Crime Delinq. (2020) 68:0011128719901110. doi: 10.1177/0011128719901110

26. Ko Ling C. Sexual violence against women and children in Chinese societies. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. (2009) 10:69–85. doi: 10.1177/1524838008327260

27. He X, Hang Ng K. In the name of harmony: the erasure of domestic violence in China's judicial mediation. Int J Law, Policy Family. (2013) 27:97–115. doi: 10.1093/lawfam/ebs014

28. Jiang J. The family as a stronghold of state stability: two contradictions in China's anti-domestic violence efforts. Int J Law, Policy Family. (2019) 33:228–251. doi: 10.1093/lawfam/ebz004

29. Li L, Sun IY, Lin K, Wang X. Tolerance for domestic violence: do legislation and organizational support affect police view on family violence? Police Pract Res. (2021) 22:1376–89. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2020.1866570

30. Lin K, Wu Y, Sun IY, Wang X. Rank, experience, and attitudes towards domestic violence intervention: a moderated mediation analysis of Chinese police officers. Polic J Policy Pract. (2021). 15:2225–40. doi: 10.1093/police/paab056

31. Lu H, Hao W. Combating domestic violence during COVID-19: what does the Chinese experience show us? Front Law China. (2021) 16:3–34. doi: 10.3868/s050-010-021-0002-9

32. Qi F, Wu Y, Wang Q. Anti-domestic violence law: the fight for women's legal rights in China. Asian J Women's Stud. (2020) 26:383–96. doi: 10.1080/12259276.2020.1798069

33. Qu J, Wang L, Zhao J. Correlates of attitudes toward dating violence among police cadets in china. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. (2018) 62:4888–903. doi: 10.1177/0306624X18801552

34. Sun IY, Wu Y, Wang X, Xue J. Officer and organizational correlates with police interventions in domestic violence in China. J Interpers Violence. (2020) 0886260520975694. doi: 10.1177/0886260520975694

35. Xie L, Eyre SL, Barker J. Domestic violence counseling in rural northern China: gender, social harmony, and human rights. Violence Against Women. (2017) 24:307–21. doi: 10.1177/1077801217697207

36. Xu Y, Li J, Wang J. Empirical study on handling of domestic violence cases by police. China J Soc Work. (2021) 14:48–58. doi: 10.1080/17525098.2020.1844930

37. Xue N. Perceptions of and attitudes towards domestic violence in China: implications for prevention and intervention. (Doctor of Philosophy Doctoral). The University of Manchester, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing database. (2008).

38. Wang X, Hayes BE, Zhang H. Correlates of Chinese police officer decision-making in cases of domestic violence. Crime Delinq. (2019) 66:1556–78. doi: 10.1177/0011128719850502

39. Wu Y, Lin K, Li L, Wang X. Organizational support and Chinese police officers' attitudes toward intervention into domestic violence. Polic Int J. (2020) 43:769–84. doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-04-2020-0048

40. Zhao R, Zhang H, Jiang Y, Yao X. The tendency to make arrests in domestic violence: perceptions from police officers in China. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. (2018) 62:4923–41. doi: 10.1177/0306624X18801653

41. Cao Y, Li L, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Guo X, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of exposure to domestic physical violence on children's behavior: a Chinese community-based sample. J Child Adolesc Trauma. (2016) 9:127–35. doi: 10.1007/s40653-016-0092-1

42. Chen W, Cao Y, Guo G, Zhang Y, Mao Q, Sun S, et al. Effective intervention in domestic violence in Chinese communities: an eight-year prospective study. EC Psychol Psychiat. (2021) 10:4–16.

43. Chung MY, Wong TW, Yiu JJ. Wife battering in Hong Kong: accident and emergency nurses' attitudes and beliefs. Accid Emerg Nurs. (1996) 4:152–5. doi: 10.1016/S0965-2302(96)90063-6

44. Lau Y, Chan KS. Moderating effect of concern for face on help seeking intention who experienced intimate partner violence during pregnancy: A retrospective cross-sectional study. In: Garner, J. B., Christiansen, T. C. (Eds.), Social Sciences in Health Care and Medicine. New York: Nova Science Publishers. (2008). p. 181–198.

45. Li Q, Liu H, Chou K-R, Lin C-C, Van I-K, Davidson PM, et al. Nursing research on intimate partner violence in China: a scoping review. Lancet Reg Health - Western Pacific. (2020) 2:100017. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100017

46. Liu N, Cao Y, Qiao H, Ma H, Li J, Luo X, et al. Traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms in the Chinese male intrafamilial physical violence perpetrators: a comparative and structural equation modeling study. J Interpers Violence. (2018) 36:2841–61. doi: 10.1177/0886260518764103

47. Loke AY, Wan MLE, Hayter M. The lived experience of women victims of intimate partner violence. J Clin Nurs. (2012) 21:2336–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04159.x

48. Yue Z, Wang H, Singhal A. Using television drama as entertainment-education to tackle domestic violence in China. J Develop Commun. (2019) 30:30–44.

49. Day T, McKenna K, Bowlus A. The economic costs of violence against women: An evaluation of the literature. Ontario, Canada. (2005). Available online at: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/vaw/expert%20brief%20costs.pdf (accessed December 12, 2021).

50. Fang X, Fry DA, Ji K, Finkelhor D, Chen J, Lannen P, et al. The burden of child maltreatment in China: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. (2015) 93:176–185C. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.140970

51. The Asia Foundation. (2017). Impact of Domestic Violence on the Workplace in China. San Francisco, CA: Available online at: https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Impact-of-Domestic-Violence-on-the-Workplace-in-China.pdf (accessed December 12, 2021).

52. World Health Organization (2004). The Economic Dimensions of Interpersonal Violence. Geneva: Available online at: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/violence/economic_dimensions/en/ (accessed December 12, 2021).

53. World Health Organization (2014). Health Statistics and Information Systems. Estimates for 2000–2012. Geneva: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/index1.html (accessed December 12, 2021).

54. Peterson C, Kearns MC, McIntosh WL, Estefan LF, Nicolaidis C, McCollister KE, et al. Lifetime economic burden of intimate partner violence among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. (2018) 55:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.049

55. United Nations. (2020). Population division: World Population Prospects 2019. Available online at: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed December 12, 2021).

56. Hu R, Xue J, Wang X. Migrant women's help-seeking decisions and use of support resources for intimate partner violence in China. Violence Against Women. (2021) 28:169–93. doi: 10.1177/10778012211000133

57. Wei D, Hou F, Hao C, Gu J, Dev R, Cao W, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and associated factors among men who have sex with men in China. J Int Viol. (2019) 36:NP11968–93. doi: 10.1177/0886260519889935

58. Yuan W, Hesketh T. Intimate partner violence and depression in women in China. J Inter Viol. (2019) 36:NP12016–40. doi: 10.1177/0886260519888538

59. Leng CH. Women in Malaysia: Present Struggles and Future Directions. In: Ng, C. (Ed.), Positioning women in Malaysia: class and gender in an industrializing state. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. (1999). p. 169–189 doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-27420-8_9

60. Lu J. Shifting public opinion in different cultural contexts: marriage equality in Taiwan. Georgetown J Int Affairs. (2020) 21:209–15. doi: 10.1353/gia.2020.0030

61. Nguyen TD. Prevalence of male intimate partner abuse in Vietnam. Viol Against Women. (2006) 12:732–9. doi: 10.1177/1077801206291555

62. Rydstrøm H. Encountering “hot” anger: domestic violence in contemporary Vietnam. Viol Against Women. (2003) 9:676–97. doi: 10.1177/1077801203009006004

63. Tonsing J, Barn R. Intimate partner violence in South Asian communities: exploring the notion of “shame” to promote understandings of migrant women's experiences. Int Soc Work. (2016) 60:628–39. doi: 10.1177/0020872816655868

64. Almosaed N. Violence against women: a cross-cultural perspective. J Muslim Minority Affairs. (2004) 24:67–88. doi: 10.1080/1360200042000212124

65. Keshav S, Roma K, Puja K, Saria P, Karan Pratap S. Policies and social work against women violence. In: Fahri, Ö. (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Policies, Protocols, and Practices for Social Work in the Digital World. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global. (2021). p. 442–462. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-7772-1.ch025

66. Mugoya GCT, Witte TH, Ernst KC. Sociocultural and victimization factors that impact attitudes toward intimate partner violence among Kenyan women. J Interpers Violence. (2014) 30:2851–71. doi: 10.1177/0886260514554287

67. Ye Y. Livestreamer's horrific death sparks outcry over domestic violence. (2020). Available online at: http://www.sixthtone.com/news/1006260/livestreamers-horrific-death-sparks-outcry-over-domestic-violence (accessed December 12, 2021).

68. Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. (1977) 32:513–31. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

69. Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. (1979) 47:263–91. doi: 10.2307/1914185

70. Schwartz A, Goldberg J. Prospect theory, reference points, and health decisions. Judgm Decis Mak. (2008) 3:174–80.

71. Treadwell JR, Lenert LA. Health values and prospect theory. Med Decis Making. (1999) 19:344–52. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9901900313

72. Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet. (2010) 376:1261–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4

73. Baldry AC, Pagliaro S. Helping victims of intimate partner violence: The influence of group norms among lay people and the police. Psychol Violence. (2014) 4:334–47. doi: 10.1037/a0034844

74. Fishbein M, Yzer MC. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Commun Theory. (2003) 13:164–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00287.x

75. Su Z, Mackert M, Li X, Han JK, Crook B, Wyeth B. “Study Natural” without drugs: An exploratory study of theory-guided and tailored health campaign interventions to prevent nonmedical use of prescription stimulants in college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:4421. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124421

76. Tankard ME, Paluck EL. Norm perception as a vehicle for social change. Soc Issues Policy Rev. (2016) 10:181–211. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12022

77. Kreuter MW, Farrell DW, Olevitch LR, Brennan LK. Tailoring Health Messages: Customizing Communication With Computer Technology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. (2000). doi: 10.4324/9781410603319

78. Kreuter MW, Skinner CS. Tailoring: what's in a name? Health Educ Res. (2000) 15:1–4. doi: 10.1093/her/15.1.1

79. Noar SM, Harrington NG, Aldrich RS. The role of message tailoring in the development of persuasive health communication messages. Ann Int Commun Assoc. (2009) 33:73–133. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2009.11679085

80. Qiao J, Wang Y, Li X, Jiang F, Zhang Y, Ma J, et al. A Lancet Commission on 70 years of women's reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health in China. Lancet. (2021) 397:2497–536. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32708-2

81. OECD. (2021). Gender wage gap. Available online at: https://data.oecd.org/earnwage/gender-wage-gap.htm (accessed December 12, 2021).

82. Iwasaki I, Ma X. Gender wage gap in China: a large meta-analysis. J Labour Market Res. (2020) 54:17. doi: 10.1186/s12651-020-00279-5

83. Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. (2012) 3:231–80. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231

84. Tu X, Lou C. Risk factors associated with current intimate partner violence at individual and relationship levels: a cross-sectional study among married rural migrant women in Shanghai, China. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e012264. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012264

85. Cheng L, Wang X. Legislative exploration of domestic violence in the People's Republic of China: a sociosemiotic perspective. Semiotica. (2018) 2018:249–68. doi: 10.1515/sem-2016-0174

86. He X, Yu C. An empirical study on cases of domestic violence: Samples of 212 cases from 22 provinces, 4 municipalities, and 4 autonomous regions in China. Canad Soc Sci. (2018) 14:51–8.

87. Arce R, Arias E, Novo M, Fariña F. Are interventions with batterers effective? A meta-analytical review. Psychosoc Interv. (2020) 29:153–64. doi: 10.5093/pi2020a11

88. Brown J. Factors related to domestic violence in Asia: the conflict between culture and patriarchy. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. (2014) 24:828–37. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2014.884962

89. Jaschok M, Miers S. Women in the Chinese patriarchal system: submission, servitude, escape and collusion. In: Jaschok, I., Miers, S., (Eds.), Women and Chinese patriarchy: submission, servitude, and escape. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. (1994). p. 1–24.

90. Sangwha L. The patriarchy in China: an investigation of public and private spheres. Asian Journal of Women's Studies. (1999) 5:9–49. doi: 10.1080/12259276.1999.11665840

91. Cai Y. China's Anti-Domestic Violence Law at the five-year mark. (2021). Available online at: https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1006903/chinas-anti-domestic-violence-law-at-the-five-year-mark (accessed December 12, 2021).

92. Kuo L. Chinese city launches domestic violence database for couples considering marriage. (2020). Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/24/chinese-city-launches-domestic-violence-database-for-couples-considering-marriage (accessed December 12, 2021).

Keywords: domestic violence, COVID-19, china, family affairs, public health, interventions

Citation: Su Z, McDonnell D, Cheshmehzangi A, Ahmad J, Chen H, Šegalo S and Cai Y (2022) What “Family Affair?” Domestic Violence Awareness in China. Front. Public Health 10:795841. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.795841

Received: 08 November 2021; Accepted: 17 January 2022;

Published: 04 March 2022.

Edited by:

Noor Hazilah Abd Manaf, International Islamic University Malaysia, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Tony Butler, University of New South Wales, AustraliaErwin Rotas, Department of Education, Philippines

Copyright © 2022 Su, McDonnell, Cheshmehzangi, Ahmad, Chen, Šegalo and Cai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhaohui Su, c3poQHV0ZXhhcy5lZHU=; Yuyang Cai, Y2FpeXV5YW5nQHNqdHUuZWR1LmNu

Zhaohui Su

Zhaohui Su Dean McDonnell

Dean McDonnell Ali Cheshmehzangi3,4

Ali Cheshmehzangi3,4