- 1Department of Medical Genetics, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Dental School, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran

- 3Faculty of Medicine, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

- 4Department of Medical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

- 5Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Research Institute for Health Development, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

- 6Board Certificate Oral and Maxillofacial Radiologist, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences (NKUMS), Bojnurd, Iran

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions on travel and quarantine measures made people turn to self-medication (SM) to control the symptoms of their diseases. Different studies were conducted worldwide on different populations, and their results were different. Therefore, this global systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the pooled prevalence of self-medication.

Methods: In this systematic review and meta-analysis, databases of Scopus, PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science were searched without a time limit. All eligible observational articles that reported self-medication during the COVID-19 pandemic were analyzed. Heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using Cochran's Q test and I2 statistics. A random-effects model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of self-medication. The methodological quality of the articles was evaluated with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Results: Fifty-six eligible studies were reviewed. The pooled prevalence of self-medication was 48.6% (95% CI: 42.8–54.3). The highest and lowest prevalence of self-medication was in Asia (53%; 95% CI: 45–61) and Europe (40.8%; 95% CI: 35–46.8). Also, the highest and lowest prevalence of self-medication was related to students (54.5; 95% CI: 40.8–68.3) and healthcare workers (32.5%; 16–49). The prevalence of self-medication in the general population (48.8%; 40.6–57) and in patients with COVID-19 (41.7%; 25.5–58). The prevalence of self-medication was higher in studies that collected data in 2021 than in 2020 (51.2 vs. 48%). Publication bias was not significant (p = 0.320).

Conclusion: During the COVID-19 pandemic, self-medication was highly prevalent, so nearly half of the people self-medicated. Therefore, it seems necessary to provide public education to control the consequences of self-medication.

Introduction

On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a state of public health emergency due to the emergence of COVID-19 disease. Six months later, ~20 million cases and 700,000 deaths were reported worldwide (1). People resorted to self-medication (SM) due to the fear of contracting COVID-19, misinformation, and low access to health services. With people confined to their homes, the Internet was the only source of information they had access to. Also, when the hospitals were filled with patients, people were afraid to go to the hospitals and started self-medication (2).

Self-medication refers to choosing and using drugs to treat self-diagnosed symptoms and diseases without consulting a doctor (3). Self-medication includes the purchase and use of over-the-counter (OTC) medications, prescription-only medications (POMs), and leftover medication out of recommended (4). Self-medication leads to resource waste, increased pathogens resistance, and antibiotic resistance (3, 5). Also, self-medication is associated with incorrect dosage, incorrect route of administration, long-term use, improper storage, drug interactions, polypharmacy, and the risk of dependence and abuse, so it has become a serious public health problem worldwide (6, 7). In most cases, the feeling of the mildness of the disease and no need to consult a doctor, previous pleasant experiences with self-treatment, the feeling of being able to self-care, and the lack of availability of a doctor increase self-treatment (4). Furthermore, socio-economic factors, lifestyle, sources of medical information, access to medicines, and the potential of managing some diseases through self-care are related to the continuous increase of self-treatment worldwide (7, 8). On the other hand, self-treatment reduces the economic burden on patients, the high cost of hospital treatments, and the pressure on health care systems, limiting the number of hospital visits (6, 9). Because self-treatment starts with self-diagnosis, the probability of its being incorrect is high, and even a correct diagnosis can be associated with the wrong treatment choice. Also, the average consumers do not know if they are in a particular group with significant side effects of medicine or not; they are unaware of drug contraindications. Sometimes, the patients take the same active ingredient with a different name, and there is a risk of double medication or harmful interactions. Sometimes there is a risk of the wrong prescription (e.g., intravenous instead of intramuscular) (10).

Different studies that have investigated the prevalence of self-medication in the COVID-19 pandemic around the world have reported different results. Knowing the prevalence of self-medication in this pandemic can provide health policymakers and researchers with helpful information. Therefore, the present study was conducted to estimate the overall prevalence of self-medication in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis, which sought to estimate the pooled prevalence of self-medication in endemic COVID-19 globally, was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (11). The PRISMA checklist is attached as a Supplementary File 1. The protocol of this systematic review was not registered in Cochrane and PROSPERO.

Search strategy

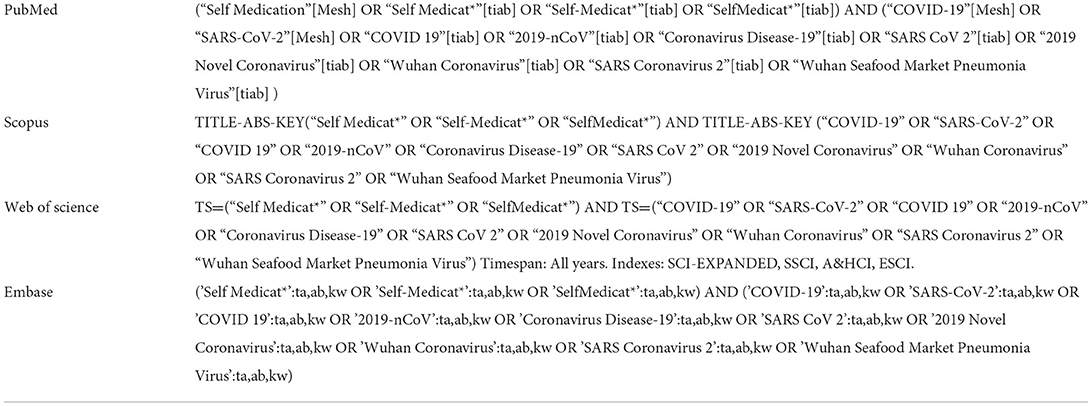

We searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase databases from January 2020 to May 2022 using the following terms: (“Self Medication” OR “Self Medicat*” OR “SelfMedicat*”) AND (“COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “COVID 19” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “Coronavirus Disease-19” OR “SARS CoV 2” OR “2019 Novel Coronavirus” OR “Wuhan Coronavirus” OR “SARS Coronavirus 2” OR “Wuhan Seafood Market Pneumonia Virus”). Databases were searched in June 2022. To access more articles, the reference list of selected articles was reviewed. Further details are provided in Table 1.

Selection of studies and data extraction

The inclusion criteria were: observational studies reporting data on the prevalence or frequency of self-medication during the COVID-19 pandemic and published in English. Exclusion criteria included unrelated studies, interventional studies, review articles, theses, case reports, and repeated articles. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the authors independently read the title and abstract of all articles and separated the relevant ones. In the next step, the authors reviewed the full text of these articles, and essential information such as the first author's name, year of publication, sample size, type of study, country, target group, mean age, and time of data collection were recorded in a pre-prepared form. Any disagreement was resolved by consultation and discussion.

Quality assessment

We used the Newcastle-Ottawa scale to check the methodological quality and assess the bias of the articles, which included seven items and three dimensions of selection, comparison, and result. These dimensions were assigned 5, 2, and 3 stars, respectively. The selection dimension with four items evaluates the target population, sample size estimation, non-response rate, and measurement tool. The first three items can be assigned up to one star and the fourth item up to two stars. The comparable dimension evaluates the use of the control group and can get up to two stars. The result dimension has two items evaluating the result (two stars) and statistical tests (one star). High-quality articles were defined as ≥4 stars (12). The bias assessment was checked by two authors independently, and any disagreements were resolved through consultation.

Meta-analysis

STATA version 16 software was used for data analysis. We used the binomial distribution to combine the selected studies. To show the general prevalence of self-medication from the Forest plot and to examine the heterogeneity among the selected studies, we used the I2 index and Cochran's Q test. We considered the I2 level >75% as high heterogeneity. Because the I2 index in this study was more than 75% and Cochran's Q test was significant, the random effects model was used to combine the selected studies. Subgroup analysis was performed based on the continent, target population, and year of data collection. Also, a meta-regression test was used to investigate the relationship between the prevalence of self-medication and the mean age of the participants. The publication bias of the studies was evaluated using a funnel plot based on Egger's regression.

Results

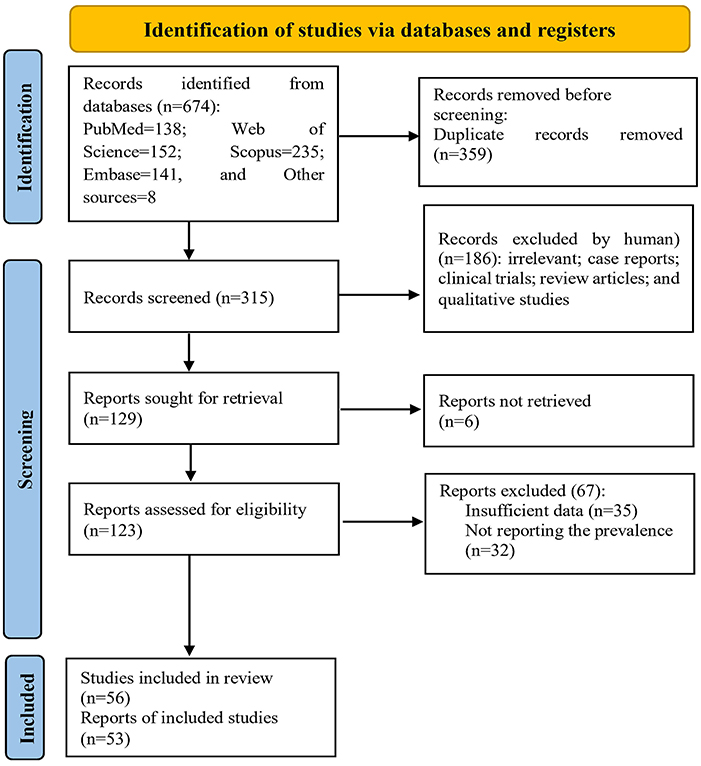

In the initial search, 674 articles were retrieved, of which 359 were removed due to duplication. Then, the authors independently reviewed the remaining articles' titles and abstracts. After screening the articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 186 articles were excluded. The full text of six articles could not be retrieved. The full text of the remaining 123 articles was reviewed. Sixty-seven articles were excluded due to not reporting the prevalence of self-medication or incomplete reports. Finally, 56 articles with a sample size of 56,063 subjects were included in the analysis (Figure 1).

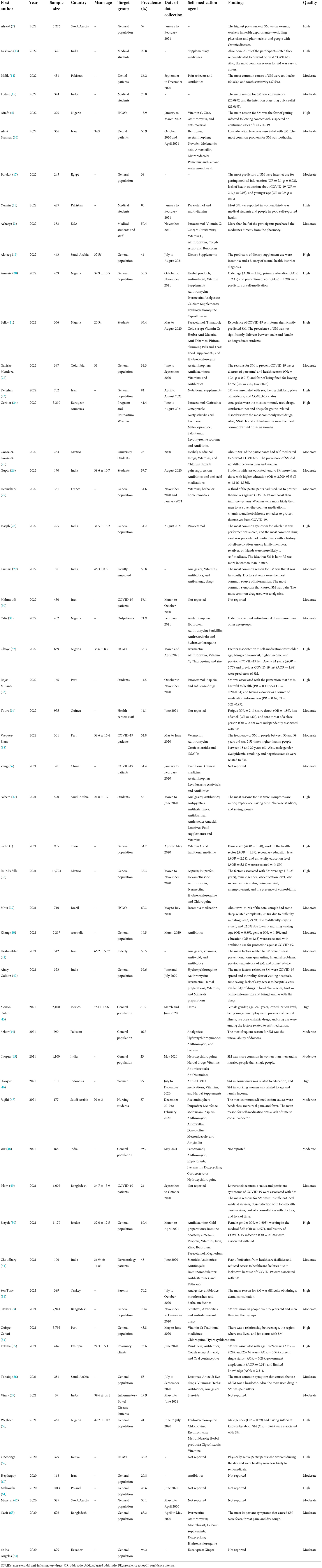

In terms of quality, 32 articles had moderate quality, and 24 studies had excellent quality (Supplementary File 2). Twenty-six studies were published in 2022, 24 in 2021, and 6 in 2020. Twelve articles published in 2022, 14 published in 2021, and two published in 2020 were high quality. Most of the studies were conducted in the Asian continent (n = 31) and on the general population (n = 29). Also, the data of 31 studies were collected in 2020. Most studies were conducted in three countries: India (n = 11), Saudi Arabia (6 studies), and Nigeria (6 studies) (Table 2). The pooled prevalence of self-medication in these three countries was 45% (95% CI: 35–55), 57% (95% CI: 43–71), and 43.5% (95% CI: 26.5–60.5), respectively.

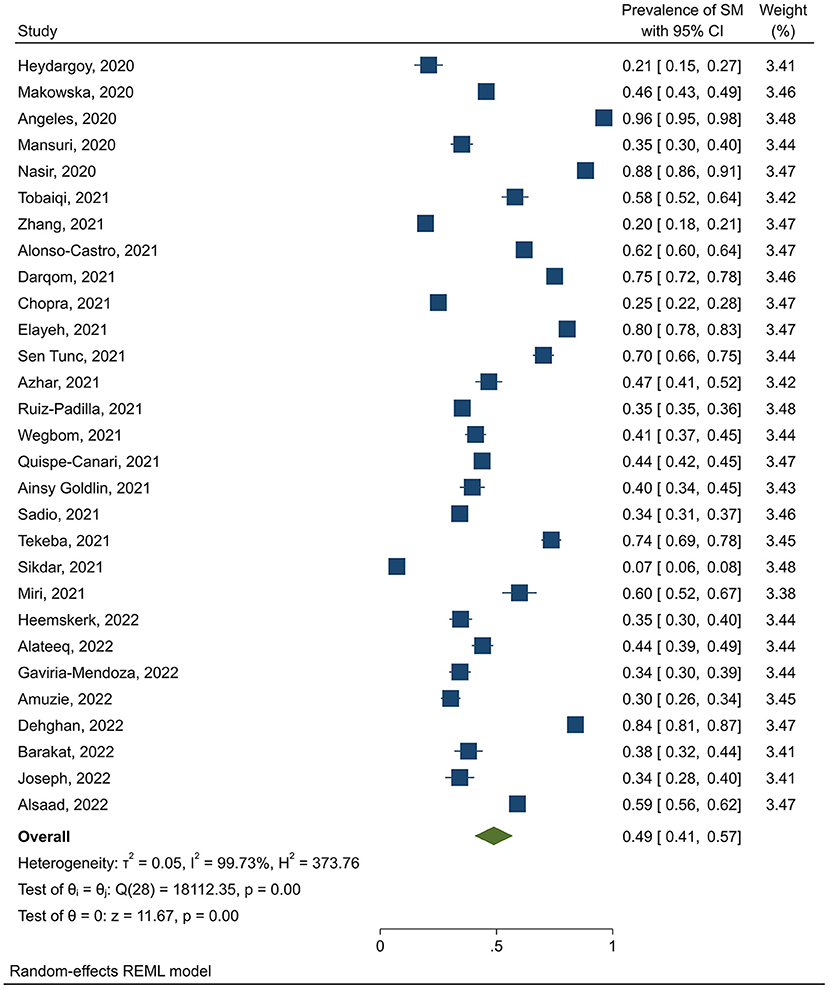

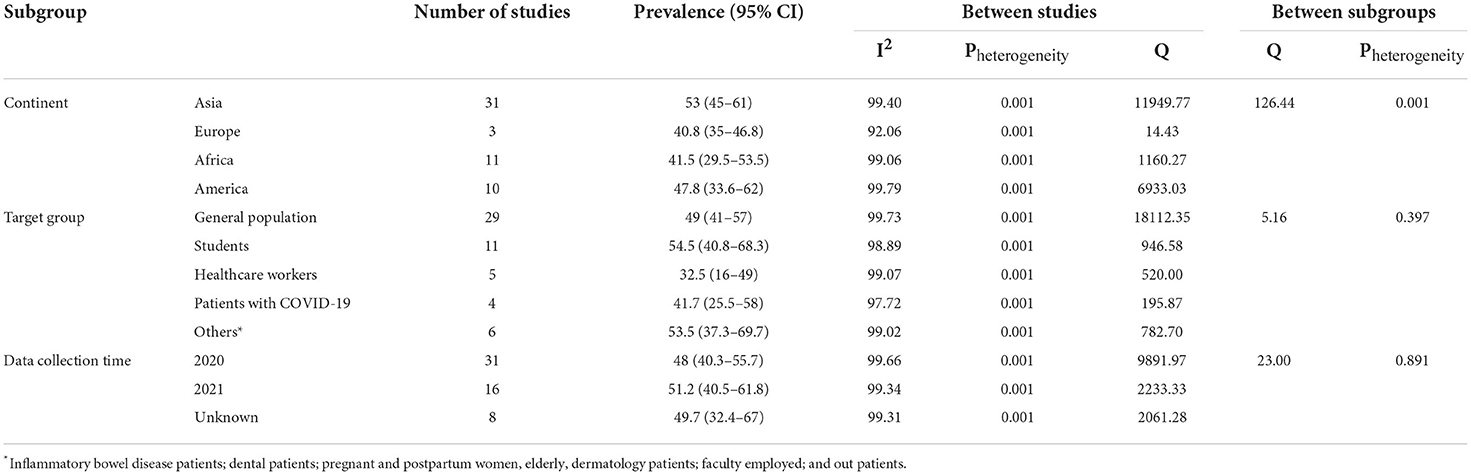

The pooled prevalence of self-medication was 49% (95% CI: 43–54). Also, the findings by continent showed that the highest and lowest prevalence of self-medication was in Asia (53%, 95% CI: 45–61) and Europe (40.8%, 95% CI: 35–46.8), respectively. The prevalence of self-medication in America (47.8%, 95% CI: 33.6–62) was higher than in Africa (41.5%, 95% CI: 29.5–53.5). By dividing the target population, the findings showed that the highest and lowest prevalence of self-treatment was related to students (54.5%, 95% CI: 40.8–68.3) and healthcare workers (35.5%, 95% CI: 16–49). The prevalence of self-medication in the general population was 49% (95% CI: 41–57) (Figure 2).

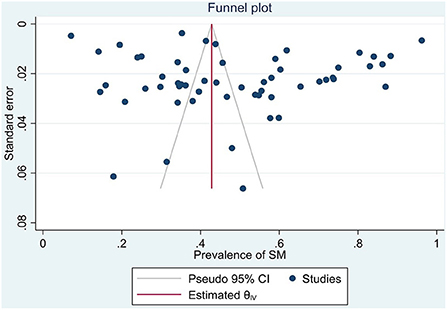

Also, the prevalence of self-medication in studies collected in 2021 (51.2%, 95% CI: 40.5–61.8) was higher than in studies collected in 2020 (48%, 95% CI: 40.3–55.7). The results of the subgroup analysis are presented in Table 3, the meta-regression results showed that the prevalence of self-medication was not related to the study sample size (p = 0.629), and the mean age of participants (p = 0.170). Publication bias was also not significant (p = 0.363) (Figure 3).

Table 3. Prevalence of self-medication during the COVID-19 pandemic by continent, target population, time of data collection.

Discussion

This study, which was conducted to estimate the cumulative prevalence of self-medication in the COVID-19 pandemic, showed that nearly half of the people have self-medicated. The results of a previous meta-analysis conducted on 14 relevant studies published between April 1, 2020, and March 31, 2022, showed that the pooled prevalence of self-medication was 44.9% (65). In addition to updating that study, we reported the results of 56 eligible studies by continent, target population, and time of data collection in the present study. James et al. (66) noted that people worldwide practice self-care practices, which in many cases are done through self-medication.

If self-treatment is done correctly, it can be beneficial for one's health. The WHO also recognizes correct self-medication as a type of self-medication (67). Mir et al. (48) mentioned that self-medication encourages patients to rely on themselves in making decisions for the management of minor illnesses.

The highest prevalence of self-medication was related to students. A recent meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of self-medication in students (before the COVID-19 pandemic) was 49.5% (68). The prevalence of self-medication among college students seems to have increased during this pandemic. This finding can be attributed to their higher education level compared to the general population. The lowest prevalence of self-medication was related to healthcare workers. This finding may be due to their familiarity with the consequences of self-medication. The low prevalence of self-medication in the European continent can be due to clear instructions regarding the distribution and provision of medicine and the general knowledge of the people of that region. The prevalence of self-medication was higher in studies that collected data in 2021. The reason for this finding can be the reduction of people's extreme fear of the COVID-19 virus and everyone's familiarity with this disease. False information at the beginning of the disease and the health measures applied by the governments had led to psychological distress and significant fear in the people, so in some countries, people bought and stored toilet paper, face masks and staple foods and even armed (69).

Although the high prevalence of self-medication can indicate people's self-care behavior, it can also lead to serious risks, especially for the elderly, children, pregnant women, and people with underlying diseases. Due to the fact that in the future, it is possible that other waves of the COVID-19 pandemic or other pandemics may occur, it is necessary to prepare and present instructions and guidelines to separate safe self-medication from high-risk ones so that the risks of self-medication are minimized.

Limitations

One of the limitations of this study was that gray texts were not included in the analysis. The reason was the lack of access to the databases that provided these documents. Another limitation of this study was that in this systematic review and meta-analysis, only articles published in English were analyzed.

Conclusion

This study showed that self-medication during the COVID-19 pandemic was highly prevalent, so nearly half of the people had self-medicated at this time. The prevalence of self-medication in students was higher than in other groups. Also, with increasing age, the prevalence of self-medication had an almost downward trend. Considering the consequences of self-medication, it seems necessary to educate the general population through the media to increase drug information and improve their health literacy. Awareness of drug risks can reduce the practice of self-medication now and even in pandemics that may occur in the future.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

GK and FT contributed to designing and performing this systematic review. RG and GK checked the data and conducted data analyses. SA and ML contributed to writing and editing the paper. All authors read and confirmed the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1041695/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Sadio AJ, Gbeasor-Komlanvi FA, Konu RY, Bakoubayi AW, Tchankoni MK, Bitty-Anderson AM, et al. Assessment of self-medication practices in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak in Togo. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:58. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10145-1

2. Ray I, Bardhan M, Hasan MM, Sahito AM, Khan E, Patel S, et al. Over-the-counter drugs and self-medication: a worldwide paranoia and a troublesome situation in India during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Med Surg. (2022) 78:103797. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103797

3. Acharya A, Shrestha MV, Karki D. Self-medication among Medical Students and Staffs of a Tertiary Care Centre during COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive cross-sectional study. J Nepal Med Assoc. (2022) 60:59–62. doi: 10.31729/jnma.7247

4. Adenike ME, Ibunkunoluwa B, Bede CA, Akinnawo OE. Knowledge of COVID-19 and preventive measures on self-medication practices among Nigerian undergraduates. Cogent Arts Humanities. (2022) 9:2049480. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2022.2049480

5. Adebisi YA, Oladunjoye IO, Tajudeen YA, Lucero-Prisno III DE. Self-medication with antibiotics among seafarers: a public health issue. Int Maritime Health. (2021) 72:241–2. doi: 10.5603/IMH.2021.0045

6. Aitafo JE, Wonodi W, Briggs DC, West BA. Self-Medication among health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in southern Nigeria: knowledge, patterns, practice, and associated factors. Int J Health Sci Res. (2022) 12:1–14. doi: 10.52403/ijhsr.20220223

7. Alsaad HA, Almahdi JS, Alsalameen NA, Alomar FA, Islam MA. Assessment of self-medication practice and the potential to use a mobile app to ensure safe and effective self-medication among the public in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. (2022) 30:927–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2022.05.010

8. Ayalew MB. Self-medication practice in Ethiopia: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2017) 11:401. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S131496

9. Noone J, Blanchette CM. The value of self-medication: summary of existing evidence. J Med Econ. (2018) 21:201–11. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1390473

10. Bown D, Kisuule G, Ogasawara H, Siregar C, Williams G. WHO guidelines for the regulatory assessment of medicinal products for use in selfmedication: general information. WHO Drug Inf . (2000) 14:18–26.

11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group* P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Internal Med. (2009) 151:264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

12. Modesti PA, Reboldi G, Cappuccio FP, Agyemang C, Remuzzi G, Rapi S, et al. Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0147601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147601

13. Kashyap S, Budihal BR. Self medication practices for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 among undergraduate medical students. J Asian Med Students' Assoc. (2022). Available online at: https://www.jamsa.amsa-international.org/index.php/main/article/view/401 (accessed October 21, 2022).

14. Malik NS, Umair M, Malik IS. Self medication among dental patients visiting Tertiary Care Hospital, during COVID-19. JPDA. (2021) 31:43–8. doi: 10.25301/JPDA.311.43

15. Likhar S, Jain K, Kot LS. Self-medication practice and health-seeking behavior among medical students during COVID 19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. MGM J Med Sci. (2022) 9:189. doi: 10.4103/mgmj.mgmj_107_21

16. Namvar MA, Mansori K, Gerayeli M. Self-medication for oral health problems in COVID-19 outbreak: prevalence and associated factors. Odovtos Int J Dental Sci. (2022) 516–24. doi: 10.15517/IJDS.2022.50876

17. Barakat AM, Mohasseb MM. Self-medication with antibiotics based on the theory of planned behavior among an Egyptian rural population during the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Egypt J Commun Med. (2022) 41:1–10. doi: 10.21608/ejcm.2022.139501.1220

18. Yasmin F, Asghar MS, Naeem U, Najeeb H, Nauman H, Ahsan MN, et al. Self-medication practices in medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional analysis. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:803937. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.803937

19. Alateeq D, Alsubaie MA, Alsafi FA, Alsulaiman SH, Korayem GB. The use of dietary supplements for mental health among the Saudi population: a cross-sectional survey. Saudi Pharm J. (2022) 30:742–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2022.03.017

20. Amuzie CI, Kalu KU, Izuka M, Nwamoh UN, Emma-Ukaegbu U, Odini F, et al. Prevalence, pattern and predictors of self-medication for COVID-19 among residents in Umuahia, Abia State, Southeast Nigeria: policy and public health implications. J Pharm Policy Prac. (2022) 15:34–43. doi: 10.1186/s40545-022-00429-9

21. Bello I, Akinnawo E, Akpunne B, Mopa-Egbunu A. Knowledge of COVID-19 and preventive measures on self-medication practices among Nigerian undergraduates. Cogent Arts Humanities. (2022) 9:2049480.

22. Gaviria-Mendoza A, Mejia-Mazo DA, Duarte-Blandon C, Castrillon-Spitia JD, Machado-Duque ME, Valladales-Restrepo LF, et al. Self-medication and the 'infodemic' during mandatory preventive isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therapeutic Adv Drug Safety. (2022) 13. doi: 10.1177/20420986221072376

23. Dehghan M, Ghanbari A, Heidari FG, Shahrbabaki PM, Zakeri MA. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in general population during COVID-19 outbreak: a survey in Iran. J Integrative Med. (2022) 20:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2021.11.004

24. Gerbier E, Favre G, Tauqeer F, Winterfeld U, Stojanov M, Oliver A, et al. Self-reported medication use among pregnant and postpartum women during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a European multinational cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:5335–42. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095335

25. Gonzalez-Gonzalez MDR, Yeverino-Gutierrez ML, Ramirez-Estrada K, Gonzalez-Santiago O. Self-medication for prevention of COVID-19 in university students of the northeast of Mexico. Interciencia. (2022) 47:240–3.

26. Gupta S, Chakraborty A. Pattern and practice of self medication among adults in an urban community of West Bengal. J Fam Med Primary Care. (2022) 11:1858–62. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1823_20

27. Heemskerk M, Le Tourneau FM, Hiwat H, Cairo H, Pratley P. In a life full of risks, COVID-19 makes little difference. Responses to COVID-19 among mobile migrants in gold mining areas in Suriname and French Guiana. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 296:114747. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114747

28. Joseph N, Colaco SM, Fernandes RV, Krishna SG, Veetil SI. Perception and self-medication practices among the general population during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in Mangalore, India. Curr Drug Safety. (2022). doi: 10.2174/1574886317666220513101349. [Epub ahead of print].

29. Kumari D, Lahiri B, Das A, Mailankote S, Mishra D, Mounika A. Assessment of self-medication practices among nonteaching faculty in a private dental college-a cross-sectional study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. (2022) 14:S577–80. doi: 10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_796_21

30. Mahmoudi H. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practice regarding antibiotic self-treatment use among COVID-19 patients. GMS Hygiene Infect Control. (2022) 17:1–5. doi: 10.3205/dgkh000415

31. Odis A. Attitude, knowledge and use of self-medication with antibiotics by outpatients of Gbagada General Hospital Gbagada Lagos. Int J Infect Dis. (2022) 116:S16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.12.039

32. Okoye OC, Adejumo OA, Opadeyi AO, Madubuko CR, Ntaji M, Okonkwo KC, et al. Self medication practices and its determinants in health care professionals during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pharmacy. (2022) 44:507–16. doi: 10.1007/s11096-021-01374-4

33. Rojas-Miliano C, Galarza-Caceres DN, Zárate-Vargas AM, Araujo-Ramos G, Rosales-Guerra J, Quiñones-Laveriano DM. Characteristics and factors associated with self-medication due to COVID-19 in students of a Peruvian University. Revista Cubana de Farmacia. (2022) 55:1–10.

34. Toure A, Camara SC, Camara A, Conde M, Delamou A, Camara I, et al. Self-medication against COVID-19 in health workers in Conakry, Guinea. J Public Health Africa. (2022) 13:1–4. doi: 10.4081/jphia.2022.2082

35. Vasquez-Elera LE, Failoc-Rojas VE, Martinez-Rivera RN, Morocho-Alburqueque N, Temoche-Rivas MS, Valladares-Garrido MJ. Self-medication in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a crosssection study in northern Peru. Germs. (2022) 12:46–53. doi: 10.18683/germs.2022.1305

36. Zeng QL, Yu ZJ, Ji F, Li GM, Zhang GF, Xu JH, et al. Dynamic changes in liver function parameters in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a multicentre, retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. (2021) 21:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06572-z

37. Saleem RT, Butt MH, Ahmad A, Amin M, Amir A, Ahsan A, et al. Practices and attitude of self-medication during COVID-19 pandemic in university students with interventional role of pharmacist: a regional analysis. Latin Am J Pharmacy. (2021) 40:1946–53.

38. Ruiz-Padilla AJ, Alonso-Castro AJ, Preciado-Puga M, Gonzalez-Nunez AI, Gonzalez-Chavez JL, Ruiz-Noa Y, et al. Use of allopathic and complementary medicine for preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection in Mexican adults: a national survey. Saudi Pharm J. (2021) 29:1056–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2021.07.009

39. Mota IA, de Oliveira Sobrinho GD, Morais IPS, Dantas TF. Impact of COVID-19 on eating habits, physical activity and sleep in Brazilian healthcare professionals. Arquivos de neuro-psiquiatria. (2021) 79:429–36. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x-anp-2020-0482

40. Zhang A, Hobman EV, De Barro P, Young A, Carter DJ, Byrne M. Self-medication with antibiotics for protection against COVID-19: the role of psychological distress, knowledge of, and experiences with antibiotics. Antibiotics. (2021) 10:1–14. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10030232

41. Heshmatifar N, Quchan ADM, Tabrizi ZM, Moayed L, Moradi S, Rastagi S, et al. Prevalence and factors related to self-medication for COVID-19 prevention in the elderly. Iran J Ageing. (2021) 16:112–27. doi: 10.32598/sija.16.1.2983.1

42. Ainsy Goldlin TJ, Prakash M. Cyberchondria and its impact on self-medication and self care in COVID-19 pandemic - a cross sectional study. Biomed Pharmacol J. (2021) 14:2235–44. doi: 10.13005/bpj/2322

43. Alonso-Castro AJ, Ruiz-Padilla AJ, Ortiz-Cortes M, Carranza E, Ramirez-Morales MA, Escutia-Gutierrez R, et al. Self-treatment and adverse reactions with herbal products for treating symptoms associated with anxiety and depression in adults from the central-western region of Mexico during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Ethnopharmacol. (2021) 272:113952. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.113952

44. Azhar H, Tauseef A, Usman T, Azhar Y, Ahmed M, Umer K, et al. Prevalence, attitude and knowledge of self medication during COVID-19 disease pandemic. Pakistan J Med Health Sci. (2021) 15:902–5. doi: 10.53350/pjmhs21155902

45. Chopra D, Bhandari B, Sidhu JK, Jakhar K, Jamil F, Gupta R. Prevalence of self-reported anxiety and self-medication among upper and middle socioeconomic strata amidst COVID-19 pandemic. J Educ Health Promotion. (2021) 10:73. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_864_20

46. D'arqom A, Sawitri B, Nasution Z, Lazuardi R. “Anti-COVID-19” medications, supplements, and mental health status in indonesian mothers with school-age children. Int J Women's Health. (2021) 13:699–709. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S316417

47. Faqihi A, Sayed SF. Self-medication practice with analgesics (NSAIDs and acetaminophen), and antibiotics among nursing undergraduates in University College Farasan Campus Jazan University, KSA. Ann Pharmaceutiques Francaises. (2021) 79:275–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2020.10.012

48. Mir S, Shakeel D, Qadri Z. Self-medication practices during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. (2021) 14:80–2. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2021.v14i10.42761

49. Islam MS, Ferdous MZ, Islam US, Mosaddek AM, Potenza MN, Pardhan S. Treatment, persistent symptoms, and depression in people infected with COVID-19 in Bangladesh. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1453–59. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041453

50. Elayeh E, Akour A, Haddadin RN. Prevalence and predictors of self-medication drugs to prevent or treat COVID-19: experience from a Middle Eastern country. Int J Clin Prac. (2021) 75:e14860. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14860

51. Choudhary N, Lahiri K, Singh M. Increase and consequences of self-medication in dermatology during COVID-19 pandemic: an initial observation. Dermatol Ther. (2021) 34:e14696. doi: 10.1111/dth.14696

52. Sen Tunc E, Aksoy E, Arslan HN, Kaya Z. Evaluation of parents' knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding self-medication for their children's dental problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health. (2021) 21:98. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01466-7

53. Sikdar K, Anjum J, Bahar NB, Muni M, Hossain SMR, Munia AT, et al. Evaluation of sleep quality, psychological states and subsequent self-medication practice among the Bangladeshi population during COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. (2021) 12:100836. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100836

54. Quispe-Canari JF, Fidel-Rosales E, Manrique D, Mascaro-Zan J, Huaman-Castillon KM, Chamorro-Espinoza SE, et al. Self-medication practices during the COVID-19 pandemic among the adult population in Peru: a cross-sectional survey. Saudi Pharm J. (2021) 29:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2020.12.001

55. Tekeba A, Ayele Y, Negash B, Gashaw T. Extent of and factors associated with self-medication among clients visiting community pharmacies in the era of COVID-19: does it relieve the possible impact of the pandemic on the health-care system? Risk Manage Healthcare Policy. (2021) 14:4939–51. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S338590

56. Tobaiqi MA, Mahrous KW, Batoot AM, Alharbi SA, Batoot AM, Alharbi AM, et al. Prevalence and association of self-medication on patient health in Medina. Med Sci. (2021) 25:2685–97.

57. Vinay G. Increased self-medication with steroids in inflammatory bowel disease patients during COVID-19 pandemic: time to optimize specialized telemonitoring services. Euroasian J Hepato Gastroenterol. (2021) 11:103–4. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1342

58. Wegbom AI, Edet CK, Raimi O, Fagbamigbe AF, Kiri VA. Self-medication practices and associated factors in the prevention and/or treatment of COVID-19 virus: a population-based survey in Nigeria. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:606801. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.606801

59. Onchonga D, Omwoyo J, Nyamamba D. Assessing the prevalence of self-medication among healthcare workers before and during the 2019. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic in Kenya. Saudi Pharm J. (2020) 28:1149–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2020.08.003

60. Heydargoy MH. The effect of the prevalence of COVID-19 on arbitrary use of antibiotics. Iran J Med Microbiol. (2020) 14:374–84. doi: 10.30699/ijmm.14.4.374

61. Makowska M, Boguszewki R, Nowakowski M, Podkowińska M. Self-medication-related behaviors and Poland's COVID-19 lockdown. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:8344–9. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228344

62. Mansuri FMA, Zalat MM, Khan AA, Alsaedi EQ, Ibrahim HM. Estimating the public response to mitigation measures and self-perceived behaviours towards the COVID-19 pandemic. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. (2020) 15:278–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2020.06.003

63. Nasir M, Chowdhury A, Zahan T. Self-medication during COVID-19 outbreak: a cross sectional online survey in Dhaka city. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. (2020) 9:1325–30. doi: 10.18203/2319-2003.ijbcp20203522

64. de los Ángeles M, Minchala-Urgilés RE, Ramírez-Coronel AA, Aguayza-Perguachi MA, Torres-Criollo LM, Romero-Sacoto LA, et al. Herbal medicine as prevention and treatment against COVID-19. Archivos Venezolanos de Farmacologia y Terapeutica. (2020) 39:948–53.

65. Ayosanmi OS, Alli BY, Akingbule OA, Alaga AH, Perepelkin J, Marjorie D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of self-medication practices for prevention and treatment of COVID-19: a systematic review. Antibiotics. (2022) 11:808–14. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11060808

66. James H, Handu SS, Al Khaja KA, Otoom S, Sequeira RP. Evaluation of the knowledge, attitude and practice of self-medication among first-year medical students. Med Principles Prac. (2006) 15:270–5. doi: 10.1159/000092989

67. World Health Organization. The Role of the Pharmacist in Self-Care and Self-Medication: Report of the 4th WHO Consultative Group on the Role of the Pharmacist. The Hague (1998).

68. Fetensa G, Tolossa T, Etafa W, Fekadu G. Prevalence and predictors of self-medication among university students in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pharm Policy Prac. (2021) 14:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s40545-021-00391-y

Keywords: self-medication, prevalence, systematic review, COVID-19, meta-analysis

Citation: Kazemioula G, Golestani S, Alavi SMA, Taheri F, Gheshlagh RG and Lotfalizadeh MH (2022) Prevalence of self-medication during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 10:1041695. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1041695

Received: 11 September 2022; Accepted: 17 October 2022;

Published: 03 November 2022.

Edited by:

Yusra Habib Khan, Jouf University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Sukrit Kanchanasurakit, University of Phayao, ThailandMohammed Gumaa, TRUST Research Center, Egypt

Copyright © 2022 Kazemioula, Golestani, Alavi, Taheri, Gheshlagh and Lotfalizadeh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammad Hassan Lotfalizadeh, ZHIubW9oYW1hZGhhc3NhbmxvdGZpemFkZWhAZ21haWwuY29t

Golnesa Kazemioula1

Golnesa Kazemioula1 Reza Ghanei Gheshlagh

Reza Ghanei Gheshlagh Mohammad Hassan Lotfalizadeh

Mohammad Hassan Lotfalizadeh