- 1Chelia District Health Office, Oromia Regional Health Bureau, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 2Department of Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ambo University, Ambo, Ethiopia

- 3Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ambo University, Ambo, Ethiopia

- 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ambo University Referral Hospital, Ambo, Ethiopia

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Medicine and Health Science, Ambo University, Ambo, Ethiopia

- 6Department of Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wachemo University, Hossana, Ethiopia

Background: The continuum of maternity care is a continuity of care that a woman receives during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period from skilled providers in a comprehensive and integrated manner. Despite existing evidence regarding maternal healthcare services discretely, the continuum of maternity care and its associated factors are not well-known in Ethiopia.

Objective: This study assessed the completion of the maternity continuum of care and associated factors among women who gave birth 6 months prior to the study in the Chelia district.

Methods: A community-based cross-sectional study with a stratified random sampling technique was conducted among 428 mothers at 10 randomly selected kebeles. Pretested and structured questionnaires were used to collect data. Bi-variable and multivariable logistic regression analyzes were performed to identify associated factors. Adjusted odds ratio with its 95% confidence interval was used to determine the degree of association, and statistical significance was declared at a p-value of <0.05.

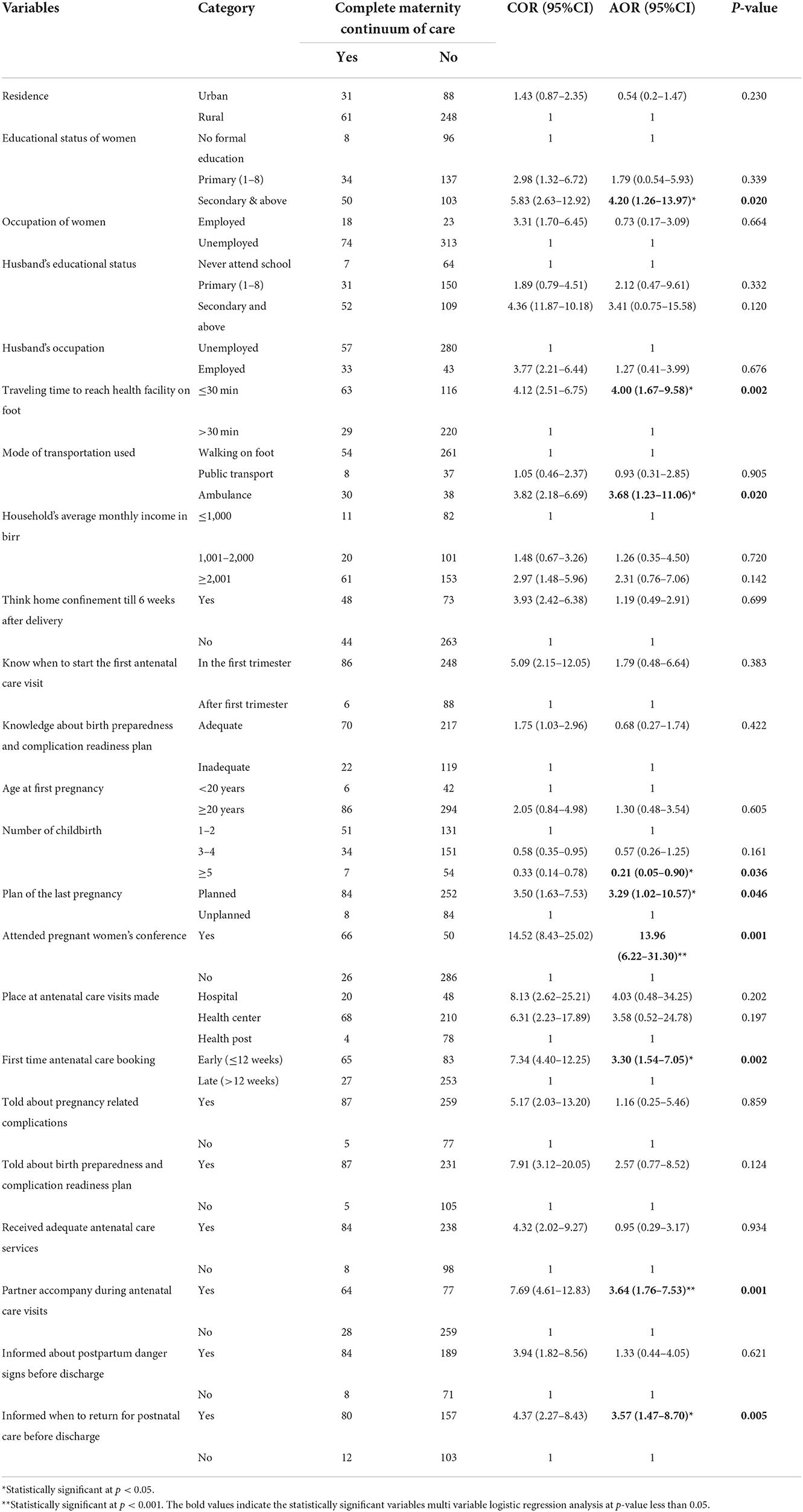

Results: In this study, 92 (21.5%) mothers completed the continuum of maternity care. Secondary and above education of mothers (AOR = 4.20, 95% CI:1.26–13.97), ≤30 min spent on walking by foot (AOR = 4.00, 95% CI: 1.67–9.58), using an ambulance to reach health facility (AOR = 3.68, 95% CI: 1.23–11.06), para ≥5 mothers (AOR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.05–0.90), planned pregnancy (AOR = 3.29, 95% CI: 1.02–10.57), attending pregnant women's conference (AOR = 13.96, 95% CI: 6.22–31.30), early antenatal care booking (AOR = 3.30, 95% CI: 1.54–7.05), accompanied by partners (AOR = 3.64, 95% CI: 1.76–7.53), and informed to return for postnatal care (AOR = 3.57, 95% CI: 1.47–8.70) were the factors identified.

Conclusion: In this study, completion of the maternity continuum of care was low. Therefore, appropriate strategic interventions that retain women in the continuum of maternity care by targeting those factors were recommended to increase the uptake of the continuum of maternity care.

Introduction

Access and use of maternity care services during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period from skilled providers are essential for the survival and wellbeing of the mother and newborn (1). An uptake of maternity care services in a continuum of care approach has a fundamental role in the reduction of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and saves mothers and babies. The key components of maternity care services are antenatal (ANC), skilled birth attendance (SBA), and postnatal care (PNC) (2).

The maternity continuum of care is the continuity of care received by women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period in comprehensive and integrated ways from a skilled provider (1, 3, 4). It is the package of high-impact maternal and child survival interventions along the continuum of care (5) and a strategy designed to monitor the quality of care provided for women and newborns (6). It is a simple, cost-effective, and low-technology intervention approach that can significantly reduce most of the preventable maternal and neonatal mortalities and maximizes the potential of women and neonates to enjoy the highest achievable level of health (1, 7, 8). The continuum of maternity care gives emphasis on two key dimensions which are the time and place or level of care. The time dimension highlights the importance of linkages among the packages of maternity care service provision over the time during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period (9). The place or level of care dimension includes the home, primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of care in healthcare deliveries (9–11). Globally, in 2017, a total of 2,95,000 women died from pregnancy and childbirth-related complications; of which, the majority of the deaths (86%) were accounted by South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Similarly, sub-Saharan Africa alone accounted for roughly two-thirds (66%) of global maternal deaths (12). Ethiopia is one of the countries with a high alert maternal mortality ratio of 401 deaths per 1,00,000 live births and accounted for about 5% of global maternal deaths (10, 12). Most of these deaths occur during childbirth and the days before the end of the first week after childbirth (11), due to the leading causes such as hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, and sepsis (13, 14), and more than 80% of them are preventable through appropriate maternity care services during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period in a continuum of care manner (6, 13, 15).

While substantial progress has been made, Ethiopia still needs to go about six and more than two-fold faster to achieve the 2030 global target of maternal and neonatal mortality reduction to less than 70 maternal deaths per 1,00,000 and less than 12 neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births, respectively (12, 16). Evidence from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) showed that completion of the maternity continuum of care was reported ranging from 5 to 75% from the studies conducted in Cambodia and Nepal, respectively (17, 18). In Ethiopia, the completion of the maternity continuum of care was reported as ranging from 6.56 to 67.8% (19, 20). Despite this evidence, the continuum of maternity care among mothers within 6 months of delivery was not addressed (21–25).

Although a number of efforts were attempted so far to address the status of maternal healthcare service utilization discretely, there is a dearth of evidence regarding the prevalence and factors associated with the completion of the continuum of maternity care among mothers who gave birth 6 months prior to the study in Ethiopia in general and in Oromia regional state in specific including the study area. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the completion of the maternity continuum of care and associated factors among women who gave birth in the last 6 months in the Chelia district.

Materials and methods

Study design, setting, and population

A community-based cross-sectional study design was conducted in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Oromia regional state, western Ethiopia, from 20 August to 30 September 2021. The district is located 178 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The district has 20 administrative kebeles (the lowest administrative unit in Ethiopia). Regarding health facilities, there are 1 general hospital, 4 health centers, 18 health posts, and 11 different types of private health facilities in the district. All mothers who gave birth 6 months prior to the study were the source population, whereas all mothers who gave birth 6 months prior to the study in randomly selected kebeles were the study population. Moreover, all mothers who were booked for antenatal care in the last pregnancy and found between the first week and 6 months after delivery were included in the study. However, mothers who fulfilled inclusion criteria but came from other areas after receiving any one of the maternity care services and those mothers who were critically ill during the data collection period were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

The sample size for this study was calculated for both specific objectives and compared, and the maximum sample size was taken. First, a single population proportion formula was used by considering the following assumptions: the proportion (P) of maternity continuum of care completion of 21.6%, which was taken from the previous study (26), 95% confidence interval at the critical value of Zα/2 = 1.96, 5% of absolute precision, and a design effect of 1.5.

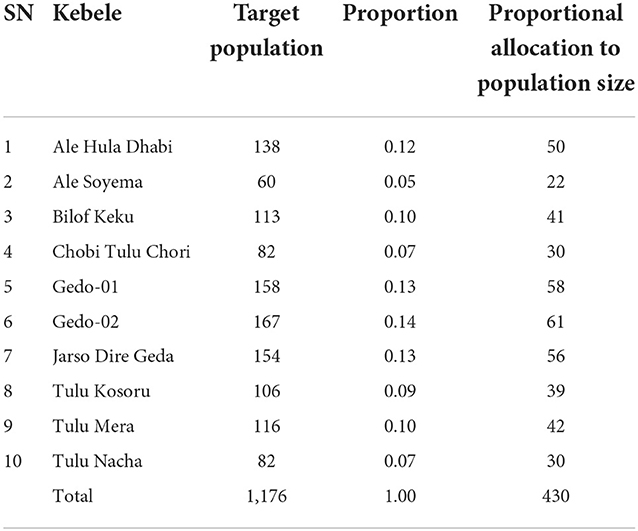

Therefore, with a 10% non-response rate, the minimum sample size for the first specific objective was 430. Similarly, the sample size was calculated for the determinant factors (19, 21, 27) to check for the adequacy of sample size by using 95% CI, power 80%, and ratio 1 (Table 1). By comparing the calculated sample size, 430 were taken as the final sample size for the study.

Table 1. Sample size determination for the second objective for mothers who gave birth in the last 6 months in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2021.

Sampling procedure and techniques

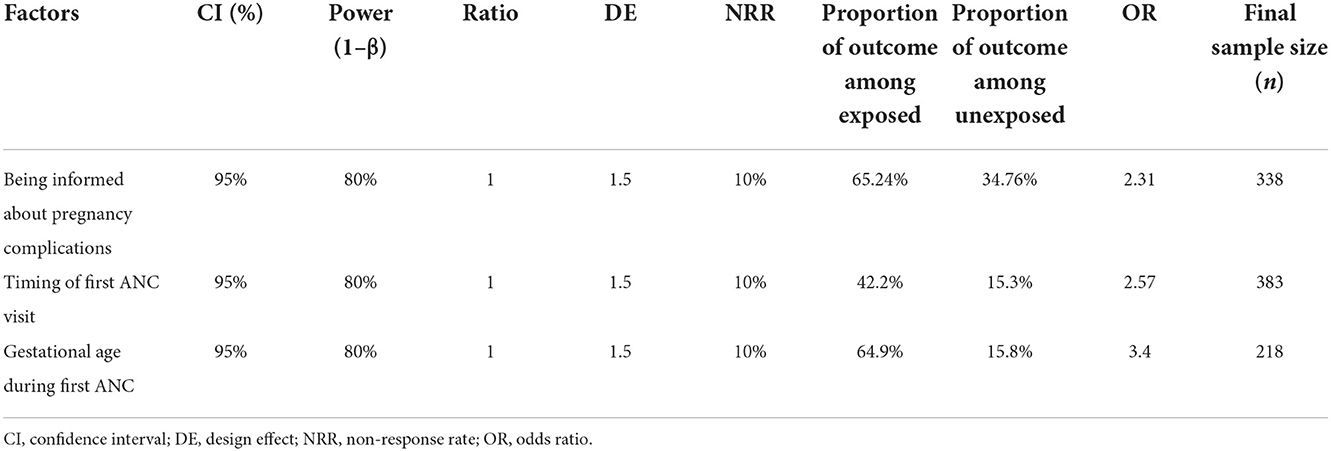

A two-stage stratified random sampling technique was employed for the selection of study subjects. In the first stage, 10 kebeles (two from urban and eight from rural strata) were selected by simple random sampling technique from a total of 20 kebeles in the district. In the second stage, the lists of households with eligible mothers were prepared from family folders found at a health post in collaboration with Health Extension Workers (HEWs) and used as a sampling frame. Then, the sample size was proportionally allocated to each selected kebele according to their population size, and a simple random sampling technique was applied to select households where eligible mothers were available. Finally, selected mothers were interviewed by data collectors at their homes with the guidance of the women's development army (WDA) from their respective villages. Mothers who were absent on the first day were revisited for the second time and absentees after two repeated visits were replaced by an immediate neighbor who fulfills inclusion criteria (Table 2).

Data collection tools and procedures

A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was adapted from different literature (19, 21–23, 26–31). The tool was arranged into three sub-titles namely socio-demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, reproductive and obstetric-related questions, and maternal healthcare service-related questions. It was initially developed in English and translated to Afan Oromo and then translated back to English by different language experts to ensure its consistency and accuracy. Data collection was conducted by four trained BSc Nurses who were recruited from outside of their catchment area. The data collection process was supervised by two health officers and a principal investigator during the data collection period.

Data quality management

Before data collection, 1-day training was given to data collectors and supervisors regarding the objective of the study, data collection procedures, and ethical considerations during data collection. Preceding the data collection, the tool was pretested on 5% of the calculated sample size. After pretesting, necessary modifications were considered. A clear explanation of the purpose and objective of the study was provided for all respondents before beginning an interview. Close supervision was carried out by supervisors and the principal investigator during the time of data collection. All filled questionnaires were checked for completeness and accuracy before data entry.

Data processing and analysis

Data were checked for completeness, coded, and entered into the computer using Epi-Data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 25 for analysis. Descriptive statistics and binary logistic regression (Bi-variable and multivariable logistic regression analyzes) model was done. Model fitness and multicollinearity effects between covariates were checked. From the bi-variable logistic regression analysis, variables having a p-value of ≤0.25 were considered eligible for multivariable logistic regression analysis. Finally, adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with their 95% confidence intervals were estimated to identify the presence and strength of associations, and statistical significance was declared at a p-value of <0.05.

Operational definition

• The maternity continuum of care was considered complete and coded as “1” when a mother received the three maternal healthcare services along with the continuum of care pathway from a skilled provider. These include four or more antenatal care (ANC) visits, childbirth attended by a skilled birth attendant (SBA), and postnatal checkup within the first week after delivery at health facilities [excluding pre-discharge postnatal care] or home by a skilled provider in a continuum of the care pathway and otherwise considered as not complete the continuum of care and coded as “0” (15, 21, 24–26, 30).

• A skilled provider is a professionally trained health worker which includes a medical doctor, midwife, nurse, and health officer (32).

Ethics statement

An ethical clearance letter with a Ref. No. of PGC/167/2021 was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Ambo University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences. Permission and a support letter to conduct the study were taken from the Chelia district health office. The purpose and importance of the study were explained, and finally, informed written consent was taken from all respondents. In addition, the confidentiality and privacy of the study participants were assured and respected.

Results

Socio-demographic and economic characteristics

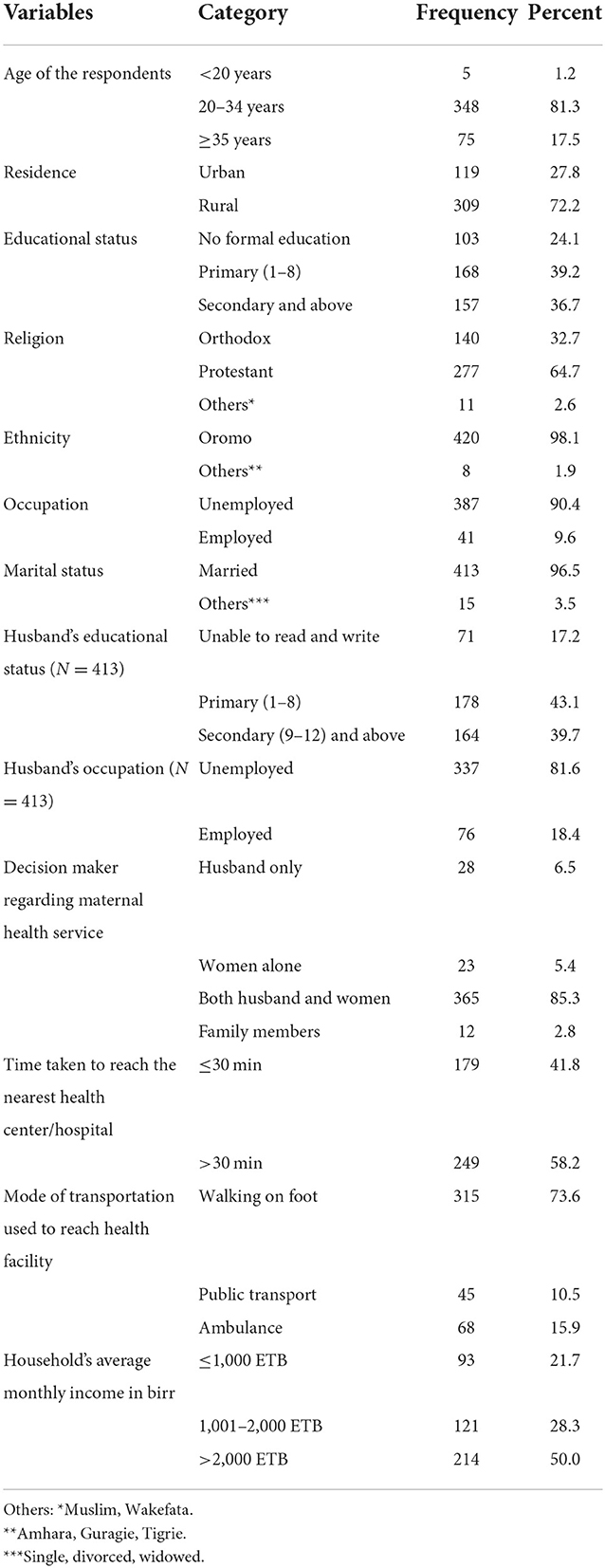

A total of 428 respondents yielding a response rate of 99.5% participated in the study. The mean age of the respondents was 28.9 (SD ± 4.871) years. One hundred and fifty-seven (36.7%) of the mothers attained a secondary and above level of education, whereas 103 (24.1%) of them have no formal education. More than half, 249 (58.2%), of the respondents spent more than 30 min walking on foot to reach the nearest health facility and 277 (73.6%) of them got the facility by walking on their feet for seeking maternity care services (Table 3).

Table 3. Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of mothers who gave birth in the last 6 months in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2021 (N = 428).

Reproductive and obstetrics-related characteristics

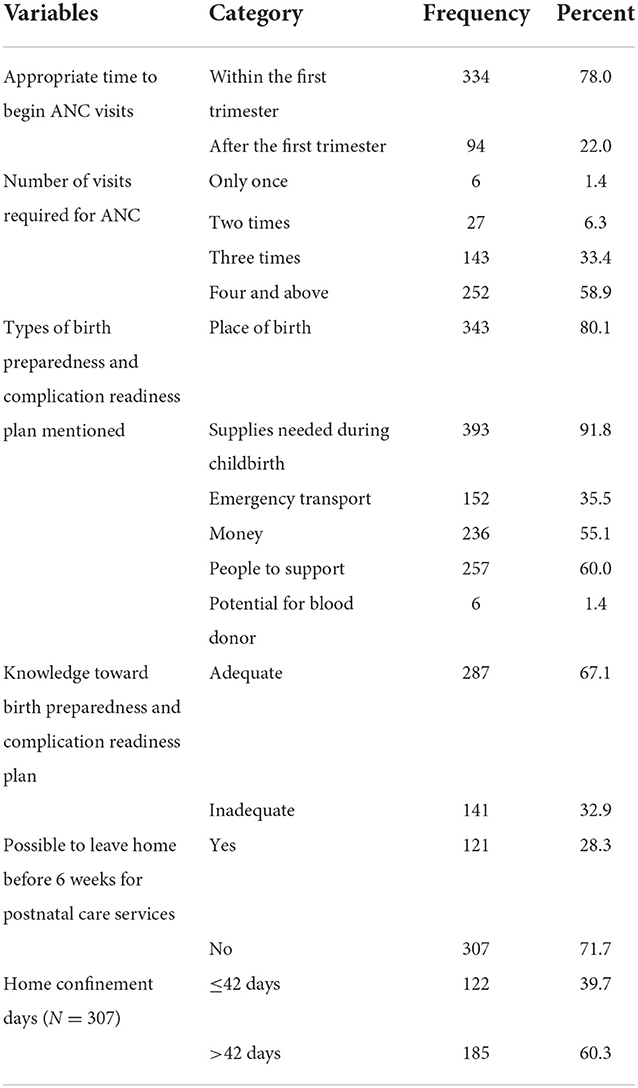

All respondents who participated in the study believed that all women need to have maternity care services from skilled providers and birth preparedness and complication readiness plans. Three hundred and thirty-four (78%) and 252 (58.9%) mothers know an appropriate time to start the first antenatal care visit and the need to have four and more ANC visits, respectively. Two hundred and eighty-seven (67.1%) mothers mentioned three and more practices of birth preparedness and complication plans. However, nearly, three-fourth, 307 (71.7%), of them reported that they need to be confined at home for the first 6 weeks after childbirth (Table 4).

Table 4. Knowledge of the respondents regarding reproductive and obstetric-related services of mothers who gave birth in the last 6 months in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2021 (N = 428).

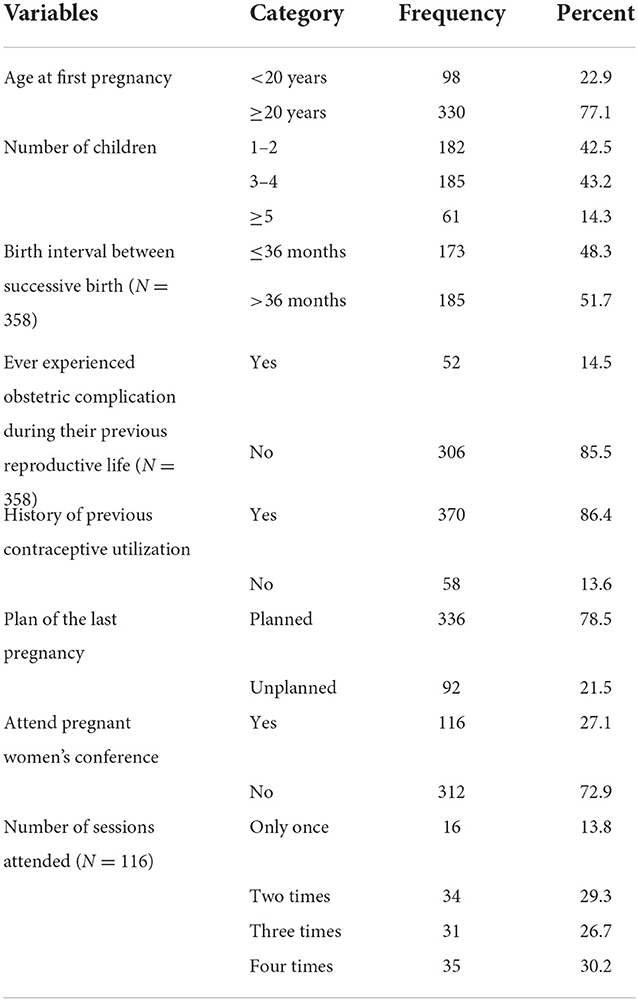

More than three-fourth, 330 (77.1%), of the respondents got their first pregnancy at an age of 20 and more years. Sixty-one (14.3%) respondents were para five and more, and 52 (14.5%) mothers had experienced different types of obstetric complications during their previous reproductive lives. Among the respondents who participated in the study, 92 (21.5%) of them reported that the last pregnancy was unplanned and 116 (27.1%) respondents attended at least one session of a pregnant women's conference (Table 5).

Table 5. Reproductive and obstetric characteristics of mothers who gave birth in the last 6 months in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2021 (N = 428).

Maternal healthcare service utilization

Antenatal care service utilization

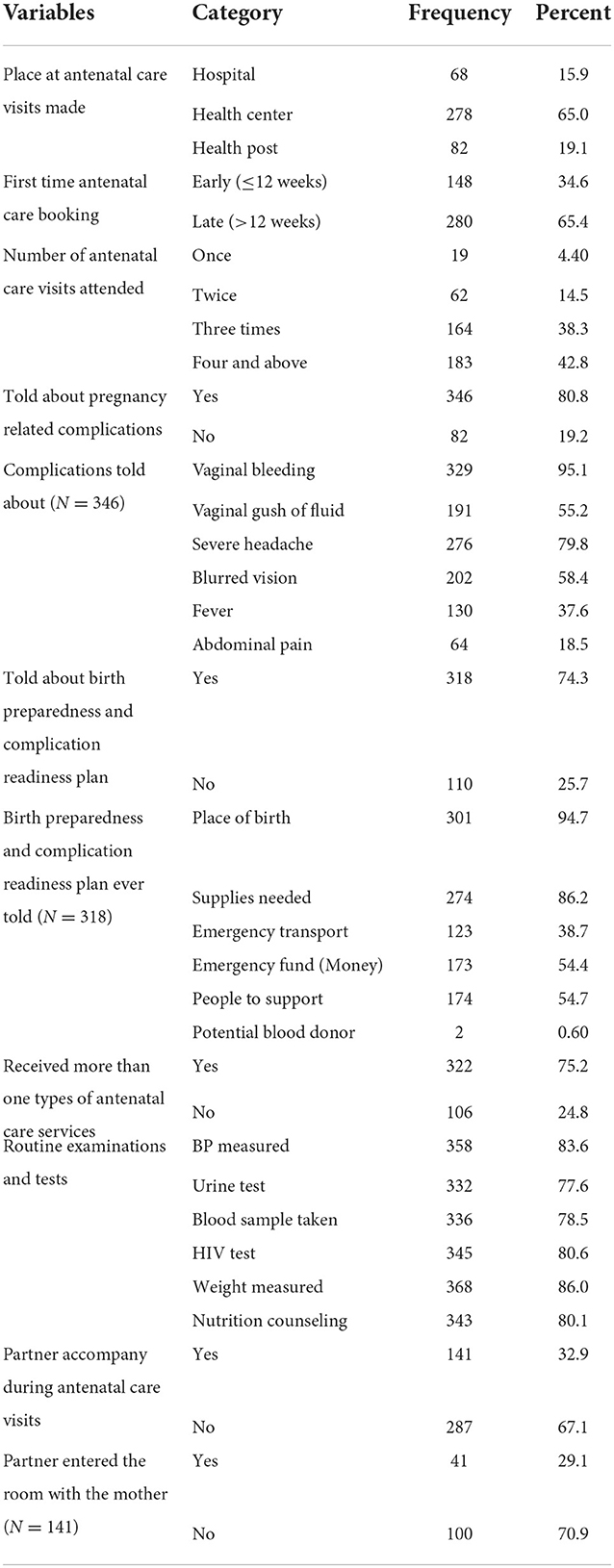

Of the total of 428 respondents, 148 (34.6%) of them initiated the first ANC visit early in the first trimester (within 12 weeks of gestation) and 183 (42.8%) of them attended ANC-4+ visits. About three-quarters, 318 (74.3%) and 346 (80.8%), of the respondents were informed about pregnancy-related complications and birth preparedness and complication readiness plans, respectively. Only, 141 (32.9%) of the respondents were accompanied by their partners to the maternity care service center (Table 6).

Table 6. Antenatal care service-related characteristics of mothers who gave birth in the last 6 months in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2021 (N = 428).

Labor and delivery service utilization

Among the total 428 respondents, 352 (82.2%) of them had childbirths attended by skilled birth attendants. Among mothers who received skilled birth attendance, only 50 (14.2%) of them stayed for 24 h and more in the health facility after giving birth. Two hundred and seventy-three (77.6%) respondents were informed about postpartum danger signs of both mothers and newborns, whereas 237 (67.3%) mothers were informed about when to return to health facilities for postnatal checkups (Table 7).

Table 7. Labor and delivery service-related characteristics of mothers who gave birth in the last 6 months in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2021 (N = 428).

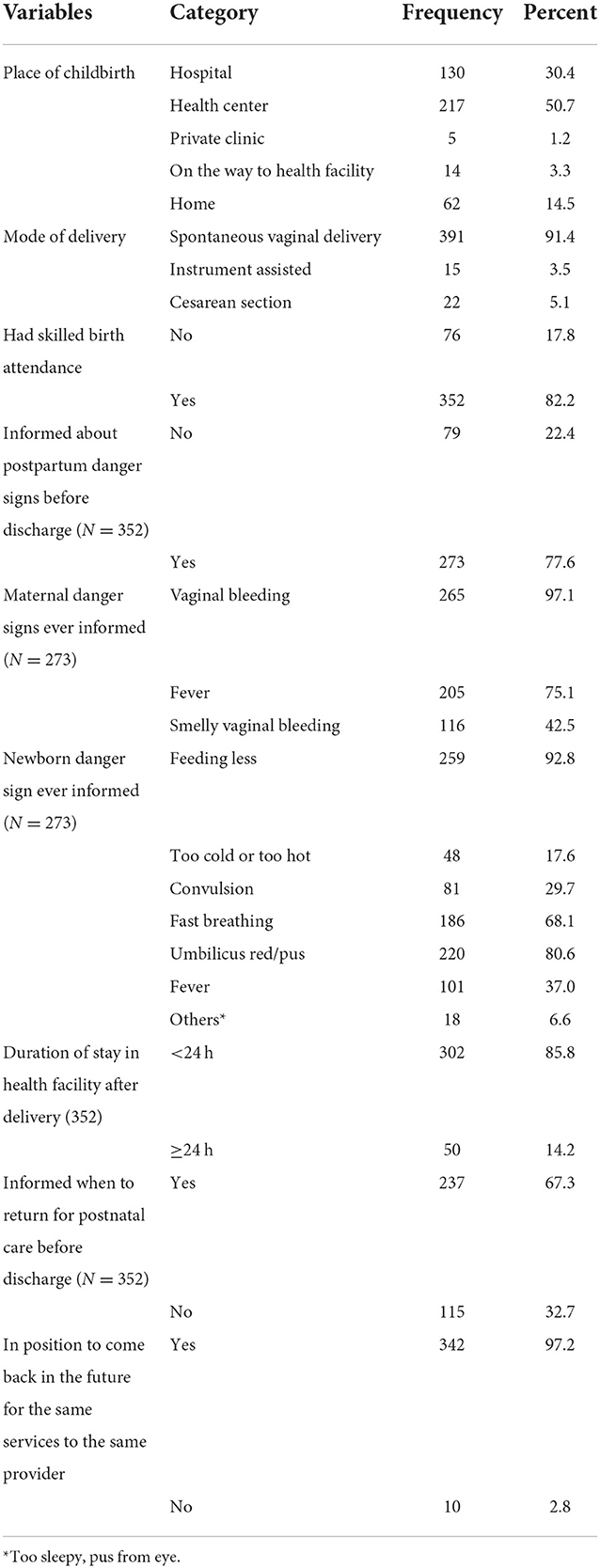

Postnatal care service utilization

Of the total of 428 respondents, nearly half, 213 (49.8), of them had at least one postnatal checkup in their last childbirth. However, only 139 (32.5%) mothers had at least one postnatal checkup within the first week of delivery. Most of the respondents were counseled for breastfeeding, 196 (92%), and postpartum family planning, 196 (92%). Among mothers who had postpartum checkups, 139 (65.3%) and 103 (48.4%) of their newborns got weight measurement and immunization services, respectively (Table 8).

Table 8. Postnatal care service-related characteristics among mothers who gave birth in the last 6 months in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2021 (N = 213).

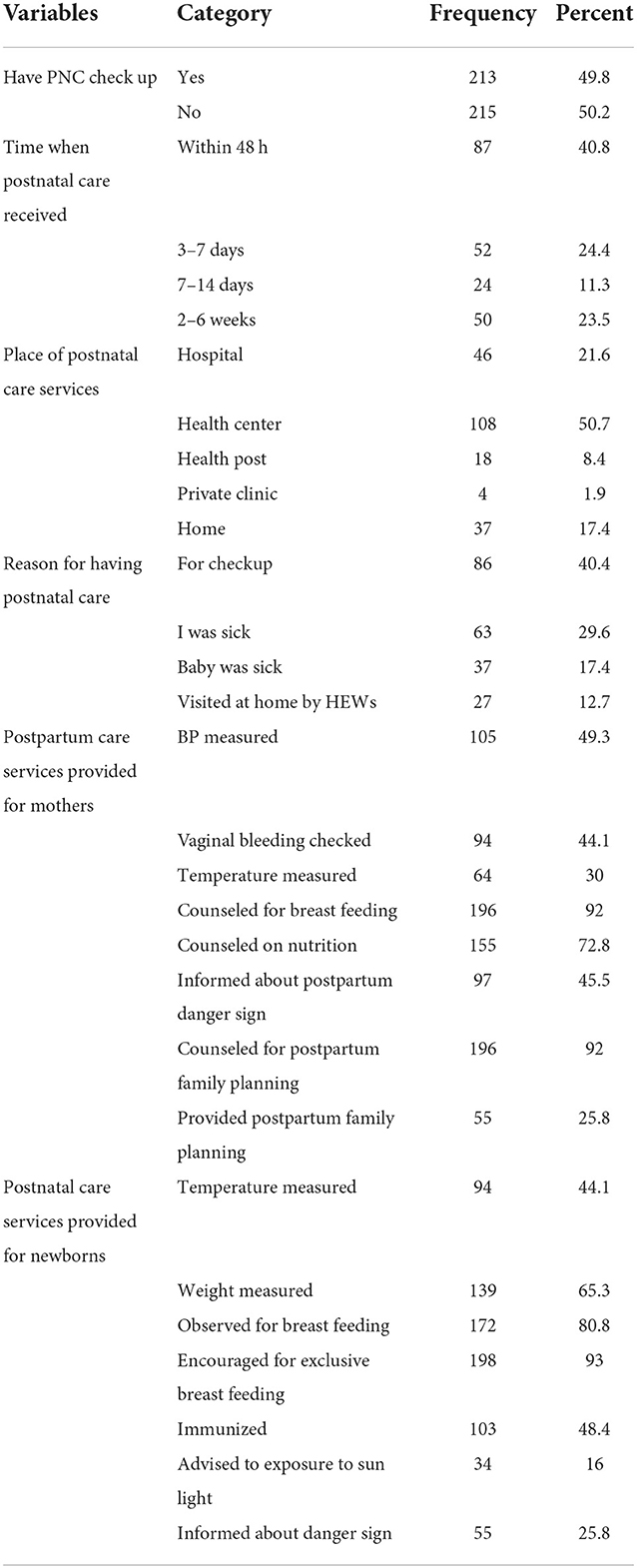

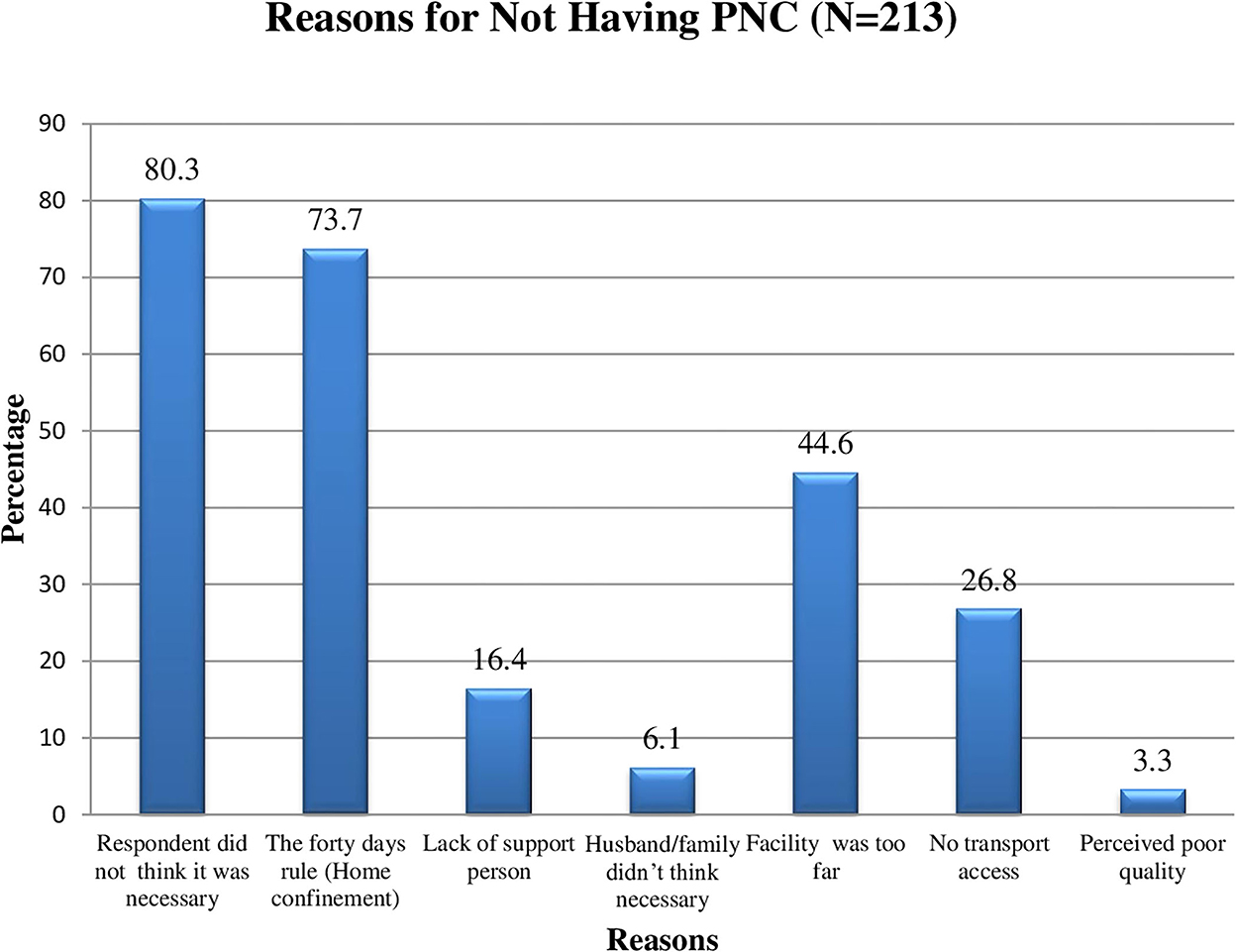

The majority of the respondents reported that they failed to have postnatal checkups due to being unaware of the need to have postnatal checkups, 171 (80.3%), and the 40-day rule of home confinement in their communities, 157 (73.7%). Moreover, 95 (44.6%) and 57 (26.8%) respondents claimed that the facility was too far and no access to transport to have a postnatal visit, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Reasons for not having postpartum check-up among mothers who gave birth in the last 6 months in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2021.

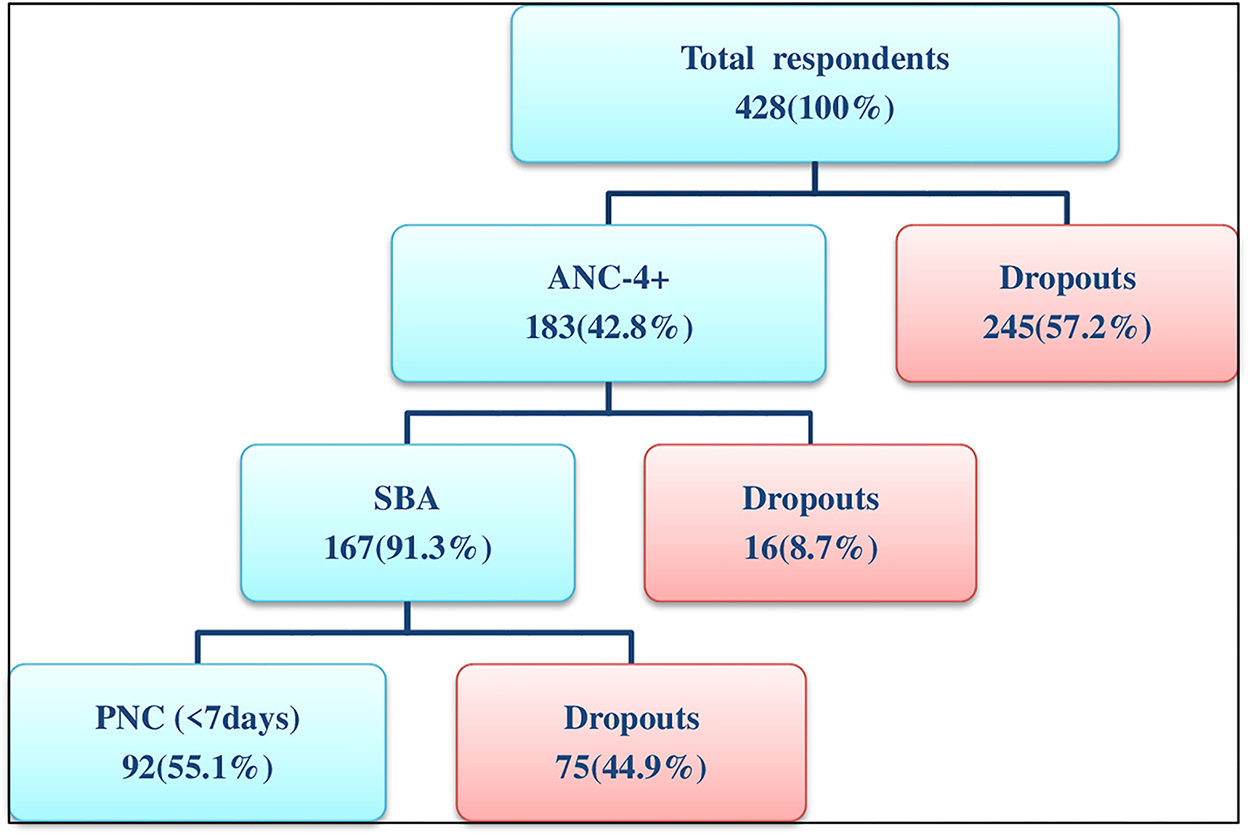

Completion of maternity continuum of care

Among all study participants, 183 (42.8%) had attended ANC-4+ visits and 167 (39%) of them retained in the continuum of care and received childbirth services from skilled birth attendants. However, only 92 (21.5%) mothers retained in the continuum of the care pathway and received at least one postnatal care service within the first week of delivery. Therefore, in this study, the overall completion of the maternity continuum of care was 21.5% (95% CI: 17.8–25.5).

Among the total 428 mothers who participated in the study, 336 (78.5%) of them were dropouts from the completion of the maternity continuum of care. Higher proportions of dropouts from the continuum of maternity care service utilization were observed at the completion of focused antenatal care visits and postnatal care service utilization (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Flowchart of the continuum of maternity care services utilization among mothers who gave birth in the last 6 months in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2021.

Factors associated with the completion of the maternity continuum of care

Place of residence, mother's and husband's level of education and employment status, time spent walking by foot to reach the nearest health facility, means of transportation used to reach a health facility, household's average monthly income, belief in a postpartum period home confinement, knowledge of appropriate time for first ANC booking, maternal age at first pregnancy, number of children, planned pregnancy, attendance of pregnant women's conference, place of ANC visits, early ANC booking within the first trimester, informed about pregnancy-related complications, and birth preparedness and complication readiness plan, receiving adequate ANC services, being accompanied by partners, being informed about postpartum danger signs, and when to return for a postpartum checkup before discharge were identified as candidate variables for multivariable logistic regression analysis.

In multivariable logistic regression analysis, mothers' secondary and above level of education, time spent ≤30 min by walking on foot to reach a health facility, use of an ambulance as a means of transportation, being para 5 and more, having planned pregnancy, attendance of pregnant women's conference (PWC), early ANC booking within the first trimester, being accompanied by partners, and informed when to return for postnatal checkups before discharge were variables associated with the completion of maternity continuum of care at a p-value of <0.05.

Mothers who attained a secondary and above level of education were 4.20 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care compared to those mothers who have no formal education (AOR = 4.20, 95% CI: 1.26–13.97). Mothers who spent ≤30 min of walking to reach the nearest health facility were four times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care compared to mothers expected to spend more than 30 min of walking to reach the nearest health facility (AOR = 4.00, 95% CI: 1.67–9.58). In addition, mothers who used an ambulance as a means of transportation to reach the health facility were 3.68 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care than those who did not use any of the vehicles but by walking on their feet (AOR = 3.68, 95% CI: 1.23–11.06).

This study also identified that para five and more mothers were 79% less likely to complete the maternity continuum of care compared to those mothers who have 1–2 children (AOR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.05–0.90). In this study, mothers to whom the last pregnancy was planned were 3.29 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care than their counterparts (AOR = 3.29, 95% CI: 1.02–10.57). Mothers who attended pregnant women's conferences were 13.96 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care than those who did not attend any session (AOR = 13.96, 95% CI: 6.22–31.30). The odds of completing the maternity continuum of care among the mothers who started ANC visits in the first trimester were 3.30 times higher than their counterparts (AOR = 3.30, 95% CI: 1.54–7.05).

Moreover, mothers who were accompanied by their partners to health facilities during their antenatal care visits were 3.64 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care compared to their counterparts (AOR = 3.64, 95% CI: 1.76–7.53). Similarly, mothers who were informed when to return for postnatal care during childbirth services to a health facility had 3.57 times higher odds of completing the maternity continuum of care than those never informed about the need to return to postnatal checkup while discharged after delivery (AOR = 3.57, 95% CI: 1.47–8.70) (Table 9).

Table 9. Factors associated with the completion of maternity continuum of care among mothers who gave birth in last 6 months in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2021.

Discussion

In this study, the overall completion of the maternity continuum of care was found to be 21.5% (95% CI: 17.8–25.5). Mothers' educational status, time spent by walking on foot and means of transportation used to reach the nearest health facility, parity, having planned pregnancy, attending pregnant women's conference, time of antenatal care booking, partners accompany, and informing when to return for postnatal care before discharge were factors associated with the completion of maternity continuum of care.

The completion of the maternity continuum of care in the present study is 21.5% (95% CI: 17.8–25.5). This finding revealed that a significant number of women dropped out from the continuum of maternity care. A higher proportion of women dropped out from the completion of the continuum of the maternity care pathway. This finding is in line with a study conducted in Nigeria (18.5%) (33), India (19%) (34), and the Dabat and Gondar Zuria districts of the Northern Gondar zone (21.6%) (26). However, it is higher than studies conducted in Cambodia (5%) (18), Ghana (7.9%) (35), Tanzania (10%) (25), Ethiopia (6.56% and 9.1%) (19, 28), Arba Minch Zuria district (9.7%) (30), Legambo district of South Wollo zone (11.2%) (36), and West Gojjam zone (12.1%) (29). The possible reason might be attributed to the time difference between the studies, and there could be an improvement in the accessibility of health services, which in turn improves the utilization of maternity care services.

However, the current finding is lower than the studies conducted in Zambia (38%) (37), Egypt (50.4%) (24), Ghana (66%) (38), Cambodia (60%) (3), Nepal (41%, 75%) (17, 39), Debre Birhan town (37.2%) (21), Enemay district (45%) (31), Motta town and Hulet Eji Enese district (47%) (27), and Debre Markos town (67.8%) (20). The possible explanation for the discrepancy might be due to the difference in maternity care services provision attributed to the difference in socio-demographic status, socioeconomic status, geographical barriers, availability, and accessibility of services and infrastructures between the countries and regions. The other reason might be the difference in the study area in which mothers from the current study were mostly rural dwellers, less educated, and had inadequate knowledge of the importance of having maternity care services in a continuum of care pathway. Moreover, the previous studies reported as maternity continuum of care was completed when mothers attended at least one ANC visit, had childbirth attended by SBA, and had at least one postpartum checkup within 6 weeks of delivery, and/or mothers attended ANC-4+ visits, had childbirth attended by SBA, and had one health checkup within 48 h or 6 weeks postpartum period (19–21, 26–31, 36). As a result, the estimation of an outcome variable might be increased when compared with this study which considered maternity continuum of care was completed for mothers who attended ANC-4+ visits, had childbirth attended by SBA, and had at least one health checkup either for themselves or for their newborns within the first week of the postpartum period.

Evidence revealed that the educational attainment of mothers was found to have a significant association with the completion of the maternity continuum of care. Accordingly, this study revealed that those mothers who attained a secondary and above level of education were 4.20 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care compared to those mothers who did not attend school. This finding is consistent with the studies conducted in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (8), India (34), Pakistan (15, 40), Lao Peoples' Democratic Republic (41), Ghana (35, 42), Nigeria (33), Egypt (24), and Ethiopia (21, 27, 31), in which mothers who attained a secondary and above level of education had higher odds of completing maternity continuum of care than those mothers who never attended school. This could be explained by the fact that more educated women have better opportunities to be aware of and able to decide when and from where to receive the recommended maternal healthcare services to be utilized throughout their reproductive lives.

Another evidence showed that the time spent walking to reach the nearest health facility for maternal and neonatal healthcare services was found to have a significant association with the completion of the maternity continuum of care. Accordingly, the finding of this study revealed that mothers who traveled for ≤30 min on foot to arrive at the nearest health facility were 4.0 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care compared to those who expected to travel for more than 30 min. This finding is comparable with the studies conducted in Cambodia (18) and Motta town and Hulet Eji Enese district of Northeast Ethiopia (27). The possible explanation is due to the fact that access to health facilities will reduce the traveling time and costs for transportation to reach health facilities and then leads to better utilization of maternity continuum of care services.

In this study, mothers who used an ambulance as a means of transportation to reach the nearest health facility had 3.68 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care than those who got a health facility by walking on their feet. This finding is supported by studies conducted in Ghana and Dabat and Gondar Zuria districts of Northern Gondar zone, Ethiopia, in which mothers who used a car as a means of transportation to get health facilities for skilled delivery services were more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care than those who got on their foot (26, 42). This might be explained by the fact that using any type of vehicle to get health facility will reduce the time spent on traveling to reach the nearest health facility and enhances skilled delivery service which is a key component of the maternity continuum of care services. Thus, using the ambulance to get to a health facility has a positive association with the completion of the maternity continuum of care.

In this study, parity was found to be significantly associated with the completion of the maternity continuum of care. The finding of this study revealed that mothers with para five and more were 79% less likely to complete the maternity continuum of care compared to para 1–2 mothers. This finding is consistent with the studies conducted in Pakistan and Egypt in which mothers with one or two birth orders had higher odds of completing the maternity continuum of care compared to their counterparts (15, 24). The possible explanation might be due to the fact that pregnancy and having a child is a source of joy and a means to replace offspring across the global community and, thus, newly married couples and those mothers with low birth orders are motivated to seek and utilize the recommended maternity care services from skilled care providers.

Mothers having a planned pregnancy were 3.29 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care compared to their counterparts. This finding is consistent with the studies conducted in the Arba Minch Zuria district of Gamo zone and Enemay districts of Northwest Ethiopia in which mothers to whom the last pregnancy was planned had higher odds of completing the maternity continuum of care than their counterparts (30, 31). The reason might be due to the fact that women with planned and wanted pregnancies are psychologically well prepared and cautious about their pregnancy and thus interested in seeking and utilizing the recommended maternal and neonatal healthcare services compared to their counterparts.

The finding of this study showed that women who attended pregnant women's conferences had 13.96 times higher odds of completing the maternity continuum of care compared to their counterparts. This finding is consistent with the study conducted in the rural Libokemkem district of Northwest Ethiopia in which women who attended pregnant women's conferences had higher odds of utilizing maternal health services compared to their counterparts (43). The possible explanation might be due to the fact that women who attended a PWC during their pregnancy could be able to have adequate maternal and neonatal healthcare service information that was recommended for all pregnant women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period from skilled providers and its merits and demerits of complete using and failing to do so compared with their counterparts.

This study also revealed women who were booked for ANC visits within the first 12 weeks of gestation for the last pregnancy were 3.30 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care than those mothers who were booked later on. This finding is supported by the studies conducted in Lao PDR (41), Tanzania (44), Motta town, and Hulet Eji Enese district of East Gojjam zone (27), Arba Minch Zuria district of Gamo zone (30), West Gojjam zone (29), and Debre Birhan town (21) in which women who were booked for ANC within the first trimester had a higher odds of completing maternity continuum of care than those booked late. The possible explanation might be due to the fact that women who booked the first ANC visit at the earlier gestational age would obtain greater opportunities of getting contact with skilled providers and adequate time for providers to communicate and enable the women to make adequate preparations and readiness to utilize the key maternity care components like skilled birth attendance and postpartum care.

The finding of this study also revealed that women who were accompanied by their partners while receiving maternity care services had 3.64 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care compared to those mothers who did not accompany skilled maternity care services by their partner. This finding is supported by the studies conducted in Bangladesh (45), Afghanistan (46), and Kenya (47) in which women who were accompanied by their partners to receive maternal and neonatal health services from skilled providers had higher odds of utilizing the next level of key maternity continuum of care components compared to their counterparts. The possible reason might be due to the synergetic effects of maternal healthcare service information and counseling provided to the couples could result in good awareness of the utilization of the key components of the maternity continuum of care services.

Mothers who were informed when to return to health facilities or maternity care services centers before discharge were 3.57 times more likely to complete the maternity continuum of care compared to their counterparts. This is consistent with the analysis done from EDHS 2016 data and a study conducted in the Dabat and Gondar Zuria district of Northern Gondar zone in which women who were informed about pregnancy-related complications and got appropriate health education regarding maternity care services to be utilized during their pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum period had higher odds of completing maternity continuum of care than their counterparts (26, 28). The possible reason might be the health information and education regarding maternity care services and postpartum period danger signs provided to women during their pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum period enhance their awareness and increase the need for seeking maternity care components compared to their counterparts. Generally, this study assessed the prevalence of the completion of the maternity continuum of care and identified factors associated with it among postpartum period mothers. This evidence might help program managers and healthcare providers to focus on identified factors to increase the uptake of the maternity continuum of care and, thus, contribute to the achievement of the global and national maternal mortality reduction plan.

This study has some limitations: First, it might be subjected to recall bias because the mothers may not recall all the services and advice they received. Second, since the study was cross-sectional, the temporal relationship between factors and outcome variables cannot be established. Finally, the incompleteness of the birth record at the health post by the health extension workers might lead the researchers to miss mothers during the sampling frame preparation.

Conclusion

An overall completion of the continuum of maternity care was low in the study area. Educational status of mothers, time spent by walking on foot and means of transportation used to reach the nearest health facility, parity, having planned pregnancy, attending pregnant women's conference, time of antenatal care booking, partners accompany, and informing when to return for postnatal care before discharge were factors associated with the completion of maternity continuum of care. Therefore, appropriate strategic interventions that retain women in the continuum of maternity care by targeting those factors were recommended to be in place by different stakeholders. Moreover, health offices should monitor the completion of the continuum of care as a performance measuring indicator as it is a priority agenda for quality service assurance and empower all healthcare providers including health extension workers and women development armies to help women to initiate early antenatal care visits, and conduct pregnant women's conference to increase uptake of the continuum of maternity care.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by an ethical clearance letter with a Ref. No. of PGC/167/2021 was obtained from Institutional Review Board of Ambo University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TB, NW, and GG conceived study protocol, participated in study design, analysis, report writing, and drafted the manuscript. FW, DD, and GM involved in analysis, report writing, and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ambo University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences for their financial support, and Chelia district health office for their assistance during data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1026236/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ANC, antenatal care; DHS, demographic and health survey; PNC, postnatal care; PWC, pregnant women's conference; SBA, skilled birth attendant; WHO, world health organization.

References

1. Tamang TM. Factors associated with completion of continuum of care for maternal health in Nepal. In: IUSSP XXVIII International Population Conference. Geneva (2017). p. 1–23.

2. World Health Organization. Making Pregnancy Safer Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Geneva: World Health Organization (2004).

3. Wang W, Hong R. Levels and determinants of continuum of care for maternal and newborn health in Cambodia-evidence from a population-based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2015) 15:62. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0497-0

4. World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Statistics-Monitoring Health for the SDGs. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016). p. 1–121.

5. Federal Ministry of Health. National Newborn and Child Survival Strategy Document Brief Summary 2015/16-2019/20. (2019).

6. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia: Health Sector Transformation Plan. (2015).

7. World Health Organization (WHO). Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM). Int J Reprod Heal. (2015).

8. Singh K, Story WT, Moran AC. Assessing the continuum of care pathway for maternal health in south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Matern Child Health J. (2016) 20:281–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1827-6

9. Kerber KJ, De Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, Okong P, Starrs A, Lawn JE. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health : from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. (2007) 370:1358–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5

10. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health (MOH). Health Sector Transformation Plan II (HSTP II) 2020/21-2024/25 (2013 EFY - 2017 EFY), Vol. 25. (2021).

11. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health (FMOH). Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health Postnatal Care Blended Learning Module for the Health Extension Programme. (2018).

12. World Health Organization. Trends in 2000 to 2017 Trends in Maternal Mortality?: 2000 TO 2017. World Health Organization (2019).

13. World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Statistics 2020: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization (2020).

14. Tesfaye G, Loxton D, Chojenta C, Assefa N, Smith R. Magnitude, trends and causes of maternal mortality among reproductive aged women in Kersa health and demographic surveillance system, eastern Ethiopia. BMC Women's Health. (2018) 18:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0690-1

15. Iqbal S, Maqsood S, Zakar R, Zakar MZ, Fischer F. Continuum of care in maternal, newborn and child health in Pakistan : analysis of trends and determinants from 2006 to 2012. BMC Health Serv Res. (2017) 17:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2111-9

16. World Health Organization. Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Selection of Data From World Health Statistics. Geneva: World Health Organization (2018). p. 4–7.

17. Koirala U, Kaphle HP, Yadav RK. Study of different factors associated with completion of continuum of care for maternal health services in Kaski district, Nepal. Asian Res J Gynecol Obstetr. (2020) 4:13–22. Available online at: https://journalarjgo.com/index.php/ARJGO/article/view/42

18. Kikuchi K, Yasuoka J, Nanishi K, Ahmed A, Nohara Y, Nishikitani M, et al. Postnatal care could be the key to improving the continuum of care in maternal and child health in Ratanakiri, Cambodia. PLoS ONE. (2018) 18:1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198829

19. Muluneh AG, Kassa GM, Alemayehu GA, Merid MW. High dropout rate from maternity continuum of care after antenatal care booking and its associated factors among reproductive age women in Ethiopia, evidence from Demographic and Health Survey 2016. PLoS ONE. (2020) 92:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234741

20. Amare NS, Araya BM, Asaye MM. Dropout from maternity continuum of care and associated factors among women in Debre Markos town, northwest Ethiopia. bioRxiv. (2019) 620120. doi: 10.1101/620120

21. Tizazu MA, Sharew NT, Mamo T, Zeru AB, Asefa EY, Amare NS. Completing the continuum of maternity care and associated factors in Debre Berhan town. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2021) 14:21–32. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S293323

22. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Monitoring Tools Birth Preparedness & Complication Readiness (BPCR). Maryland, MD: Brown's Wharf (2004). p. 338.

23. Federal Ministry of Health. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. 2016. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Rockville, MD: CSA and ICF (2016).

24. Hamed AF, Roshdy E, Sabry M. Egyptian status of continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health : Sohag Governorate as an example. Int J Med Sci Public Health. (2018) 7:417–26. doi: 10.5455/ijmsph.2018.0102607032018

25. Mohan D, LeFevre AE, George A, Mpembeni R, Bazant E, Rusibamayila N, et al. Analysis of dropout across the continuum of maternal health care in Tanzania : findings from a cross-sectional household survey. Health Policy Plann. (2017) 32:791–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx005

26. Atnafu A, Kebede A, Misganaw B, Teshome DF, Biks GA, Demissie GD, et al. Determinants of the continuum of maternal healthcare services in northwest Ethiopia : findings from the primary health care project. Hindawi J Preg. (2020) 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2020/4318197

27. Asratie MH, Muche AA, Geremew AB. Completion of maternity continuum of care among women in the post-partum period : magnitude and associated factors in the northwest, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. (2020) 1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237980

28. Chaka EE, Parsaeian M, Majdzadeh R. Factors associated with the completion of the continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health services in Ethiopia. Multilevel model analysis. Int J Prev Med. (2019) 10:136. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_26_19

29. Emiru AA, Alene GD, Debelew GT. Women's retention on the continuum of maternal care pathway in west Gojjam zone, Ethiopia : multilevel analysis. BMC Preg Childbirth. (2020) 5:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-02953-5

30. Haile D, Kondale M, Andarge E, Tunje A, Fikadu T, Boti N. Level of completion along continuum of care for maternal and newborn health services and factors associated with it among women in Arba Minch Zuria woreda, Gamo zone, southern Ethiopia : a community based cross—sectional study. PLoS ONE. (2020) 1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221670

31. Lankrew AS. Completion of maternity continuum of care and factors associated with it among mothers who gave birth in the last one year in Enemay district. J Pregnancy Child Health. (2020) 7. doi: 10.1155/2020/7019676

32. Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Key Indicators. Rockville, MD: EPHI and ICF (2019).

33. Akinyemi JO, Afolabi RF, Awolude OA. Patterns and determinants of dropout from maternity care continuum in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2016) 16:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1083-9

34. Usman M, Anand E, Siddiqui L, Unisa S. Continuum of maternal health care services and its impact on child immunization in India : an application of the propensity score matching approach. J. Biosoc. Sci. (2020) 16:1–20. doi: 10.1017/S0021932020000450

35. Shibanuma A, Yeji F, Okawa S, Mahama E, Kikuchi K, Narh C, et al. The coverage of continuum of care in maternal, newborn and child health: a cross-sectional study of woman-child pairs in Ghana. BMJ Glob Health. (2018) 1–13. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000786

36. Cherie N, Abdulkerim M, Abegaz Z, Walle Baze G. Maternity continuum of care and its determinants among mothers who gave birth in Legambo district, South Wollo, northeast Ethiopia. Health Sci Rep. (2021) 4:1–8. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.409

37. Sserwanja Q, Musaba MW, Mutisya LM, Olal E. Continuum of maternity care in Zambia : a National Representative Survey. Res Squ. (2021) 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-04080-1

38. Enos JY, Amoako RD, Doku IK. Utilization, predictors and gaps in the continuum of care for maternal and newborn health in Ghana. Int J Matern Child Health AIDS. (2021) 10:98–108. doi: 10.21106/ijma.425

39. Chalise B, Chalise M, Bista B, Pandey AR, Thapa S. Correlates of continuum of maternal health services among Nepalese women: evidence from Nepal multiple indicator cluster survey. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0215613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215613

40. Maheen H, Hoban E, Bennett C. Factors affecting rural women's utilization of continuum of care services in remote or isolated villages or Pakistan—A mixed-methods study. Women Birth. (2020) 2019:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.04.001

41. Sakuma S, Yasuoka J, Phongluxa K, Jimba M. Determinants of continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health services in rural Khammouane, Lao PDR. PLoS ONE. (2019) 1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215635

42. Yeji F, Shibanuma A, Oduro A, Debpuur C. Continuum of care in a maternal, newborn and child health program in Ghana : low completion rate and multiple obstacle factors. PLoS ONE. (2015) 1–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142849

43. Asresie MB, Dagnew GW. Effect of attending pregnant women's conference on institutional delivery, northwest Ethiopia: comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2019) 19:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2537-7

44. Larsen A, Exavery A, Phillips JF, Tani K. Predictors of health care seeking behavior during pregnancy, delivery, and the postnatal period in rural Tanzania. Matern and Child Health J. (2016) 2:1726–34. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-1976-2

45. Rahman AE, Perkins J, Islam S, Siddique AB, Moinuddin M, Anwar MR, et al. Knowledge and involvement of husbands in maternal and newborn health in rural Bangladesh. BMC Preg Childbirth. (2018) 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1882-2

46. Alemi S, Nakamura K, Rahman M, Seino K. Male participation in antenatal care and its influence on their pregnant partners' reproductive health care utilization : insight from the 2015 Afghanistan Demographic and Health Survey. J Bio Soc Sci. (2021) 53:436–58. doi: 10.1017/S0021932020000292

Keywords: maternity continuum of care, mothers, West Shoa zone, uptake of the continuum of maternity care, completion

Citation: Buli TD, Wakgari N, Ganfure G, Wondimu F, Dube DL, Moti G and Doba YS (2023) Completion of the continuum of maternity care and associated factors among women who gave birth in the last 6 months in Chelia district, West Shoa zone, Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 10:1026236. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1026236

Received: 23 August 2022; Accepted: 18 November 2022;

Published: 04 January 2023.

Edited by:

Peter Bai James, Southern Cross University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Gizachew Tiruneh, JSI Research and Training Institute, EthiopiaTesfanesh Lemma, Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia

Copyright © 2023 Buli, Wakgari, Ganfure, Wondimu, Dube, Moti and Doba. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Negash Wakgari, bmVnYXNod2FrZ2FyaSYjeDAwMDQwO3lhaG9vLmNvbQ==

Temesgen Daksisa Buli1

Temesgen Daksisa Buli1 Negash Wakgari

Negash Wakgari Gemechu Ganfure

Gemechu Ganfure Fikadu Wondimu

Fikadu Wondimu Gonfa Moti

Gonfa Moti