94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Public Health , 15 November 2022

Sec. Health Economics

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1009964

This article is part of the Research Topic Translating Health Economics Research into Public Health Action: Towards an Economy of Wellbeing View all 15 articles

Background: Welfare legal problems and inadequate access to support services follow both the socioeconomic and the health inequalities gradients. Health Justice Partnership (HJP) is an international practitioner-led movement which brings together legal and healthcare professionals to address the root causes of ill health from negative social determinants. The aim of this paper was to identify the current evidence base for the cost-effectiveness of HJP or comparable welfare advice services.

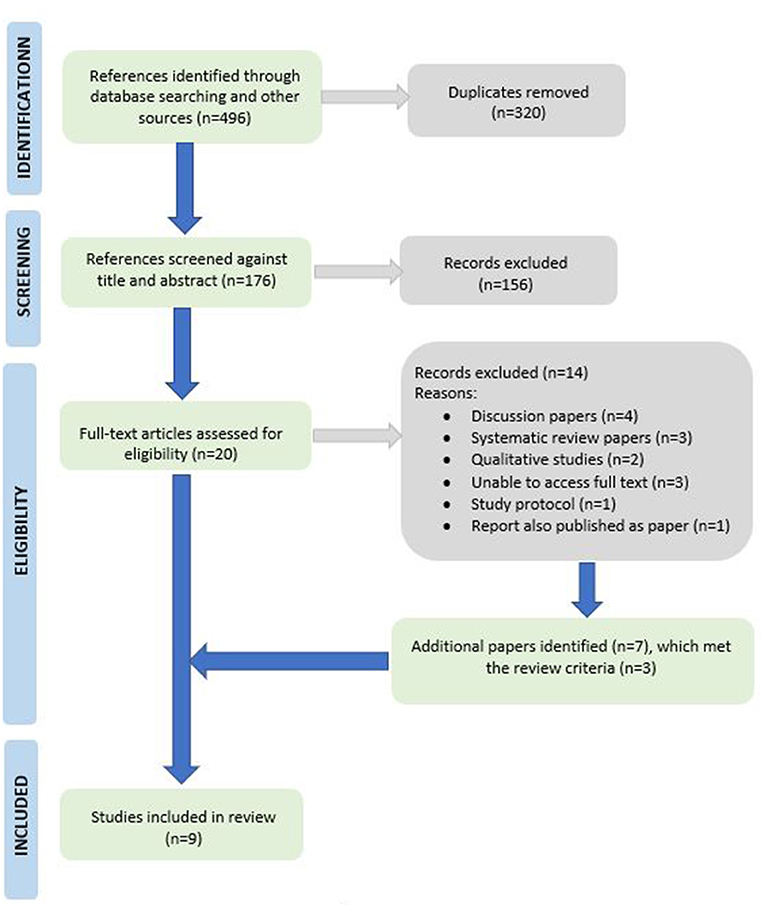

Methods: A rapid review format was used, with a literature search of PubMed, CINAHL, ASSIA, PsycINFO, Medline, Cochrane Library, Global Health and Web of Science identifying 496 articles. After removal of duplicates, 176 papers were screened on titles and abstracts, and 20 papers met the eligibility criteria. Following a full-text screening, a further 14 papers were excluded due to lack of economic evaluations. Excluded papers' reference lists were scanned, with a further 3 further papers identified which met the inclusion criteria. A final pool of nine studies were included in this review.

Results: Studies focused on the financial benefit to service users, with only three studies reporting on cost effectiveness of the interventions. Only one study reported on the economic impact of change of health in service users and one study reported on changes in health service use.

Conclusion: This review highlights the current evidence gap in evaluating the cost-effectiveness of adequate access to free legal welfare advice and representation. We propose that an interdisciplinary research agenda between health economics and legal-health services is required to address this research gap.

Socioeconomic deprivation is acknowledged to cast a long shadow on the health and wellbeing of affected populations, not only within but across generations (1). We are familiar with models of the socioeconomic determinants of health e.g., the Dahlgren-Whitehead model (2). The 2010 Marmot review (3) proposed six policy objectives required to reduce health inequalities:

1. Give every child the best start in life

2. Enable all children, young people and adults to maximize their capabilities and have control over their lives

3. Create fair employment and good work for all

4. Ensure a healthy standard of living for all

5. Create and develop healthy and sustainable places and communities

6. Strengthen the role and impact of ill-health prevention.

Successful and sustainable approaches to reducing these health inequalities will depend upon stronger collaborative working across sectors.

Experience of welfare legal problems and inadequate access to free legal support follows not only the socioeconomic gradient, but also the health inequalities gradient (4–7). Although legal issues are embedded in most social determinants of health and are recognized at the macro legislative level, the need for free legal services to improve health at a local or individual level has largely been overlooked. It was not specifically highlighted in the 10-year reviews by Marmot and colleagues (8, 9), nor in the current discourse on “leveling up” (10).

It is acknowledged that the root cause of a significant proportion of healthcare usage (in both primary and secondary healthcare) in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations is not only due to the direct health outcomes associated with depression but associated “non-health” socio-legal issues, such as family breakdown, employment problems, access to welfare benefits and inadequate housing (11). People on low income or experiencing poor physical or mental health are more likely to have a need for legal support in accessing welfare benefits, managing debt or addressing housing issues. However, they often have difficulty accessing legal support and frequently approach inappropriate sources, such as GPs who are unlikely to be able to provide guidance (12, 13). This additional strain on GPs in deprived areas is not only unlikely to be effective for the individual but it deflects primary care resources away from healthcare provision in already overburdened GP practices.

Health Justice Partnership (HJP) is an international practitioner-led movement which brings legal and healthcare professionals together to address the root causes of ill health among low income and vulnerable groups from negative social determinants (4). HJPs, which are also referred to as medical-legal partnerships (MLP) in the US, are collaborations between health and free welfare legal services providing advice and support for patients experiencing health-harming challenges such as housing problems (e.g., landlord/tenant disputes, housing discrimination), benefits (e.g., benefits accessibility and claims denials), family (e.g., child support and civil protective orders) and consumer (e.g., bankruptcy and utility shut-offs). Welfare legal service providers working in partnership with health services are therefore highly relevant to public health, as they focus on prevention, by addressing upstream systematic social and legal problems that affect patient and population health. Many of the health issues experienced by individuals are due to, or exacerbated by, the effect of unenforced laws or incorrect denial of critical services or support that they are entitled to. Rather than creating new laws, the primary aim of HJP is to ensure that public bodies comply with current statutory responsibilities and that individuals receive the benefits and conditions to which they are legally entitled.

The aim of this paper was to present a rapid literature review to identify the current evidence base for the cost-effectiveness of HJP or comparable welfare advice services. In addition, to investigate if there is evidence for the impact of these services on wider measures, such as service user health and healthcare usage.

The literature search strategy followed rapid review procedure (14). The period 1st January 1995 to 14th July 2022 used covers the period since HJP were first reported (15). The following academic databases were examined: PubMed, CINAHL, ASSIA, PsycINFO, Medline, Cochrane Library, Global Health and Web of Science. Titles and abstracts were searched, with search terms based on the criteria of “social welfare legal advice” AND “health economic evaluation methods”. The full list of terms searched for were: “legal support” OR “legal advice” OR “legal service” OR “health justice” OR “health justice partnership” OR “health-justice partnership” OR “medical legal partnerships” OR “medical-legal partnerships” OR “health law partnership” OR “Citizens Advice” OR “CAB” OR “welfare legal advice” OR “ welfare benefits” OR “welfare claims” OR “debt advice” OR “housing advice” OR “immigration advice” OR “family advice” AND “cost-benefit analysis” OR “cost-utility analysis” OR “cost-effective analysis” OR “cost effective*” OR “social return on investment” OR “return on investment” OR “social cost-benefit analysis” OR “ cost-minimization analysis” OR “cost-consequence analysis” An additional search in Google Scholar was also conducted using the same search terms.

The database search identified 496 references. After the removal of duplicates, 176 references were screened against title and abstracts, with a further 156 papers being excluded. This left a total of 20 papers to be assessed on their full text articles. All searches and article assessments were carried out by the lead author (RG). Papers that did not contain financial or economic analyses were excluded. Excluded papers included systematic reviews, discussion papers, qualitative studies, a trial protocol paper and a report that was later published in a peer reviewed journal. Although reviews and discussion papers were not included, their reference lists were scanned to identify additional citations. This identified seven additional papers that were retrieved for further examination, three of which met the inclusion criteria for this review. A final pool of nine articles was included in this rapid review (see Table 1). Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for this study. Quality assessments were carried out for the nine included articles using the Joanna Briggs Institute JBI critical appraisal tools for Case Reports, Randomized Controlled Trials, Quasi-Experimental and Economic Evaluation.

Figure 1. PRISMA study selection flowchart (25).

Of the nine papers identified, eight described studies conducted in the UK (17–24), and one described a study conducted in the US (16). Four were studies published in peer-reviewed journals (16, 18, 22, 24) and five were non-peer reviewed reports including: a 2015-16 Citizens Advice (CA) report (17), a National Institute of Health & Care Research (NIHR) study report (19), University of Chester digital repository report (20), a study report from the Glasgow Centre for Population Health (21), and a UK-based housing association study report (23). Of the nine studies, seven were mixed methods studies, with five of these being case reports (16, 17, 20–22), two being pilot RCTs (19, 24) and one was a quasi-experimental controlled trial (23). The ninth study was a quantitative quasi-experimental controlled trial (18). Only one study was classified as a HJP intervention (16); four of the studies had welfare advice provided by CA (17–20) or Money Advice, which is an equivalent service based in Scotland (21). One study described welfare advice provided by Macmillan Cancer Support (22), one study described social landlord associations providing welfare advice (23), and in one study welfare advice was provided by local authority welfare department (24). Of the nine studies included, the four peer reviewed studies (16, 18, 22, 24) were of moderate to high quality, according to the JBI quality appraisal checklists. Whereas the non-peer reviewed studies (17, 19–21, 23) were of low to moderate quality (see Appendix).

The single study that reported on a HJP was a study on the impact of civil legal aid services for women experiencing intimate partner violence in the US (16). This small study (n = 82) reported that 12 months after initial service use, women had an average increase in income of $5,500, which was driven by significant increases in wages from jobs and child support (private income) and decreases in food stamps (public income). The scheme had a positive return on investment (ROI), as women's overall income increased by $2.41 for every $1 spent on the service. A year after accessing the service, the odds of women being in poverty was approx. 2.5 times lower [reverse odds ratio (rOR) = 0.28] than before service use. This indicated that as well as the financial improvements to service users and government (due to the reduction in public support) the intervention was able to improve the socio-economic status of service users.

The CA 2015/16 financial evaluation (17) reported a ROI of £20.57 for every £1 invested in welfare advice services. This included £10.97 financial increase to service users (through benefits gained, debts written off and consumer problems resolved), £1.52 of savings to government (due to reduction in benefits claimed and health service demand), and £8.08 in wider economic and social benefits (for clients and CA volunteers). Sixty-five to seventy-five percent clients also stated that welfare issues were causing them stress and anxiety, although the impact of service use on these measures was not assessed.

Several of the studies included reviewed the provision of CA welfare advice services in primary or secondary healthcare settings. Woodhead et al., evaluated the cost-effectiveness of co-located welfare services, and the impact of debt advice on mental health and primary healthcare use (18). The study reported a ROI of £15 to service users per £1 of funder investment, with an average financial gain per participant of £2,689 over the 8-month study period. The service also reduced the level of common mental disorders (CMD) diagnoses for specific demographic groups, with both women and black service users having a reduced likelihood of CMD diagnosis compared to controls (rOR = 0.37 and rOR = 0.09, respectively). The authors reported that after 3 months there were no significant changes in GP consultation rates, although this was a shorter evaluation period than the 8 months used for the financial evaluation.

A feasibility RCT to determine the effect of debt counseling in primary care settings on mental health and healthcare use (19) was not able to complete the planned health economics evaluation due to a small trial size (n = 61) and high dropout rate over the 12-months of the trial. Although the study did not report cost-effectiveness, we have included this study as it was one of the few studies to aim to complete a full economic evaluation. In addition, descriptive statistics from the health economic dataset indicate that the intervention group did have lower levels of acute admissions and higher levels of community service use for mental healthcare or alcohol/substance misuse than the control group. Further studies are needed to determine if these reported changes indicate significant changes in use of healthcare due to a welfare intervention.

Caiels and Thurston also reported an average of £1,041 financial gains for service users of welfare advice in primary care (20). Although the study did not include a ROI analysis, CA consultancy time per case type was included. A high number (68%) of services users also reported improvements in anxiety and general health in qualitative interviews, but these changes were not corroborated by the self-report questionnaire data (SF-12).

Three of the included studies focused on the provision of legal or welfare advice for specific target groups or welfare issues. The Healthier, Wealthier Children Project (21) provided welfare advice services to pregnant women and families with young children at risk of, or experiencing, child poverty. Welfare advice was provided in healthcare settings with referrals by midwifes and health visitors. The service identified that almost half of service users were entitled to additional financial support and reported an average gain per service user of £3,404. Improvements in wellbeing were reported in qualitative interviews, but not quantified.

Moffatt et al. (22) evaluated a Macmillan Cancer Support funded welfare rights service to cancer patients. The authors reported that 96% of service users had successful welfare benefit claims, which led to a median increased weekly income of £70.30. A full cost evaluation was not completed in this study. Qualitative analysis highlighted that the impact of the intervention had lessened the impact of lost earnings, helped offset the costs associated with cancer, increased the ability to maintain independence, reduced stress and anxiety, and improved wellbeing and quality of life. Although this study did not look to include changes in these factors in their evaluation, these are factors that may have the potential to show a higher level of economic return on this type of intervention.

Evans and McAteer (23) reported that a scheme for social landlords providing debt advice to their tenants who were in debt arears decreased tenants' debt arrears by an average of £360 a year. The scheme had a positive ROI, with landlords recouping £122 for every £100 invested, due to both a reduction in arrears and the costs associated with addressing the debt. Half of participants reported that the service had helped them avoid court appearances or eviction. The threat of eviction is often a traumatic experience to tenants (26) and evictions also have high-cost implications for landlords (27). So, the study demonstrated that provision of welfare legal advice services can have financial benefits to both tenants and landlords, with potential further economic benefits due positive impacts of health and wellbeing of tenants.

Howel et al. (24) was the only paper to include both financial and health measures in their economic analyses. This included a within-trial cost-consequence analysis (CCA) to provide a breakdown and range of individual costs and benefits, and a Cost-Utility Analysis (CUA) that included both cost data and a measure of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) using the EQ-5D questionnaire. Although the provision of domiciliary advice to older people in socio-economically deprived areas was not cost effective in this trial, the study highlighted several issues that could be used as guidance for future studies. By targeting geographical areas rather than individuals with socio-economic inequalities, participants turned out to be more affluent than anticipated and therefore less eligible for the welfare service, indicating the need for more tailored and targeted interventions. The CUA showed that the intervention was more costly but also more effective than usual care, with the CCA highlighting that 38% of delivery costs were due to advisors traveling to participants' homes. This indicates that further work is required to explore he potential cost-effectiveness of services provided outside CA or healthcare settings. This may include online or group-based services or co-location with other multi-disciplinary centers already being used by potential service users, such as social/community centers or food banks.

The aim of this review was to determine the current evidence of the cost-effectiveness of legal and welfare rights services. Only nine studies were identified, including four peer-reviewed studies (of medium-high quality) and five non-peer reviewed reports (of low-medium quality).

Eight of the included studies reported financial improvement to services users, with the ninth study unable to report due to low recruitment. However, only three of the papers reported on cost-effectiveness of interventions or included an assessment on the financial impact on stakeholders other than service users. Although this is in line with the studies' perspective, it is perhaps surprising that ROI was not more consistently investigated, considering that the focus of the studies was financial gain due to service provision.

In addition, few studies looked to determine the wider impact of the interventions on health or health service use. Although many of the studies used qualitative interviews to investigate changes in mental and physical health, only three studies used quantitative measures and one study used a health economic measure (CUA) to evaluate the impact of the interventions on participants' health. As discussed in the introduction, a significant amount of primary and secondary healthcare usage is reported to be driven by non-health socio-legal issues. However only one study reported on changes in healthcare usage (18). No changes were reported after 3 months in the study, although this was acknowledged as a rather short time period for follow-up. As the socio-economic problems that are addressed by legal and welfare programs often have adverse impacts on mental and physical health, it seems reasonable to conclude that health measures should be included in legal and welfare service evaluations.

The Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders (LASPO) Act of 2012 is acknowledged to have significantly restricted legal aid funding in the UK (28). It is perhaps not surprising that many of the studies identified in this review were provided by charities such as CA. CA provides similar welfare advice to HJP, including providing advocacy to some clients, and has continued to receive funding from government and local councils post-2012. However, the search included pre-2012 studies and US based studies, where HJP is well-established (15). As only one HJP specific study, and only a total of four peer-reviewed welfare intervention studies with health economic evaluations were identified in this review, it indicates that there is a lack of economic evaluations of these services.

We propose that developing effective methods to measure the impact of HJP and similar interventions may be difficult due to the following reasons. These types of interventions are often used to treat diverse populations or interventions, where outcomes can vary significantly across different population groups or intervention types. There may be barriers to information sharing between healthcare organizations and legal partners, which was highlighted in a recent study (29). There are also considerable differences in the US and UK healthcare systems, the two countries with the main utilization of health justice interventions (15), which may mean it is difficult to compare the impact of interventions. The requirement to develop a more standardized approach to evaluating legal and welfare studies has been highlighted (30). A more consistent quantitative approach to intervention assessments would also give the ability to provide a consistent health economic assessment of these types of interventions.

In conclusion, this rapid literature review highlights the current evidence gap in what we know about the potential cost-effectiveness to society of enabling people to have adequate access to welfare advice and specialist free legal advice and representation. Based on the geographical location of reviewed articles we propose an initial UK/US focused interdisciplinary research agenda between health economics and legal-health services to address this research gap, with the intention to extend this to a more international research agenda in future years.

RG, HG, and RT: review conceptualization. RG: database searches, article assessments, paper reviews, paper quality assessments, and writing review. HG and RT: editing review and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1009964/full#supplementary-material

1. Maguire D, Buck D. Inequalities in Life Expectancy-Changes Over Time and Implications for Policy. King's Fund (2015).

2. Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Equity in Health. Institute for Futures Studies (2007). Available online at: http://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10234/187797/GoeranD_Policies_and_strategies_to_promote_social_equity_in_health.pdf?sequence=1oratttps://www.iffs.se/media/1326/20080109110739filmZ8UVQv2wQFShMRF6cuT.pdf (accessed June 7, 2022).

3. Marmot M, Allen J, Goldblatt P, Boyce T, McNeish D, Grady M, et al. The Marmot Review: Fair Society, Healthy Lives. London: UCL (2010).

4. Genn H. When law is good for your health: mitigating the social determinants of health through access to justice. Curr Leg Probl. (2019) 72:159–202. doi: 10.1093/clp/cuz003

5. Balmer NJ, Patel A, Denvir C, Pleasence P. Unmanageable Debt and Financial Difficulty in the English and Welsh Civil and Social Justice Survey: Report for the Money Advice Trust. London: Legal Services Commission (2010).

6. Coumarelos C, Pleasence P, Wei Z. Law and disorders: Illness/disability and the experience of everyday problems involving the law. Justice Issue. (2013) 17:1–23. doi: 10.3316/ielapa.277728567019202

7. Prettitore P. Do the Poor Suffer Disproportionately From Legal Problems? Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2022/03/23/do-the-poor-suffer-disproportionately-from-legal-problems/ (accessed June 21, 2022).

8. Marmot M. Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. BMJ. (2020) 368:m693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m693

9. Marmot M, Allen J, Goldblatt P, Herd E, Morrison J. Build Back Fairer: The Covid-19 Marmot Review. The Health Foundation (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/build-back-fairer-the-covid-19-marmot-review (accessed June 10, 2022).

10. Gov.uk. Policy paper Leveling Up in the United Kingdom (2022). Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1052046/Executive_Summary.pdf (accessed July 15, 2022).

11. Advice C. Royal College of General Practitioners. Advice in Practice: Understanding the Effects of Integrating Advice in Primary Care Settings. London: Citizens Advice (2018).

12. Finn D, Goodship J. Take-Up of Benefits and Poverty: An Evidence and Policy Review. JRF/CESI Report. London: Center for Economic and Social Inclusion (2014).

13. Pleasence P, Balmer NJ, Buck A. The health cost of civil-law problems: further evidence of links between civil-law problems and morbidity, and the consequential use of health services. J Empir Leg Stud. (2008) 5:351–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-1461.2008.00127.x

14. Tricco AC, Khalil H, Holly C, Feyissa G, Godfrey C, Evans C, et al. Rapid reviews and the methodological rigor of evidence synthesis: a JBI position statement. JBI Evid Synth. (2022) 20:944–9. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-21-00371

15. Beardon S, Woodhead C, Cooper S, Ingram E, Genn H, Raine R. International evidence on the impact of health-justice partnerships: a systematic scoping review. Public Health Rev. (2021) 42:1603976. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2021.1603976

16. Teufel J, Renner LM, Gallo M, Hartley CC. Income and poverty status among women experiencing intimate partner violence: A positive social return on investment from civil legal aid services. Law Soc Rev. (2021) 55:405–28. doi: 10.1111/lasr.12572

17. Citizens Advice. Modelling Our Value to Society in 2015/16. Available online at: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/Public/Impact/ModellingthevalueoftheCitizensAdviceservicein201516.pdf (accessed July 22, 2022).

18. Woodhead C, Khondoker M, Lomas R, Raine R. Impact of co-located welfare advice in healthcare settings: prospective quasi-experimental controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. (2017) 211:388–95. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.117.202713

19. Gabbay MB, Ring A, Byng R, Anderson P, Taylor RS, Matthews C, et al. Debt counselling for depression in primary care: an adaptive randomised controlled pilot trial (DeCoDer study). Health Technol Assess. (2017) 21:1. doi: 10.3310/hta21350

20. Caiels J, Thurston M. Evaluation of the Warrington District CAB GP Outreach Project. Centre for Public Health Research, Chester: University College Chester (2005).

21. Naven L, Withington R, Egan J. Maximising Opportunities: Final Evaluation Report of the Healthier, Wealthier Children (HWC) Project. Glasgow Centre for Population health (2012). Available online at: tinyurl.com/cdnd8us (accessed May 13, 2013).

22. Moffatt S, Noble E, White M. Addressing the financial consequences of cancer: qualitative evaluation of a welfare rights advice service. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e42979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042979

23. Evans G, McAteer M. Does Debt Advice Pay? A Business Case for Social Landlords. London: The Financial Inclusion Centre (2011).

24. Howel D, Moffatt S, Haighton C, Bryant A, Becker F, Steer M, et al. Does domiciliary welfare rights advice improve health-related quality of life in independent-living, socio-economically disadvantaged people aged≥ 60 years? Randomised controlled trial, economic and process evaluations in the North East of England. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0209560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209560

25. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

26. Tsai J, Huang M. Systematic review of psychosocial factors associated with evictions. Health Soc Care Commun. (2019) 27:e1–9. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12619

27. Holl M, Van Den Dries L, Wolf JR. Interventions to prevent tenant evictions: a systematic review. Health Soc Care Commun. (2016) 24:532–46. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12257

28. Low Commission on the Future of Advice and Legal Support (England and Wales), Low CM. Tackling the Advice Deficit: A Strategy for Access to Advice and Legal Support on Social Welfare Law in England and Wales. London: Legal Action Group (2014).

29. Thorpe JH, Cartwright-Smith L, Gra E, Mongeon M, National Center for Medical Legal Partnership. Information Sharing in Medical-Legal Partnerships: Foundational Concepts and Resources (2020). Available online at: https://medicallegalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Information-Sharing-in-MLPs.pdf (accessed May 25, 2022).

Keywords: health justice partnerships (HJP), health economics, welfare legal advice, return on investment (ROI), rapid review, cost-consequence analysis (CCA), cost-utility analysis (CUA), public health

Citation: Granger R, Genn H and Tudor Edwards R (2022) Health economics of health justice partnerships: A rapid review of the economic returns to society of promoting access to legal advice. Front. Public Health 10:1009964. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1009964

Received: 02 August 2022; Accepted: 26 October 2022;

Published: 15 November 2022.

Edited by:

Mariana Dyakova, Public Health Wales NHS Trust, United KingdomReviewed by:

Chin Chin Sia, Taylor's University, MalaysiaCopyright © 2022 Granger, Genn and Tudor Edwards. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rachel Granger, cmFjaGVsLmdyYW5nZXJAYmFuZ29yLmFjLnVr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.