94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 14 October 2021

Sec. Environmental Health and Exposome

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.718846

This article is part of the Research Topic Environmental Health Issues in Contemporary Southeast Asia View all 7 articles

Background: Carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning is the leading cause of poisoning death worldwide, but associations between CO poisoning and weather remain unclear.

Objective: To quantify the influence of climate parameters (e.g., temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed) on the incidence risk of acute CO poisoning in Taiwan.

Methods: We used negative binomial mixed models (NBMMs) to evaluate the influence of weather parameters on the incidence risk of acute CO poisoning. Subgroup analyses were conducted, based on the seasonality and the intentionality of acute CO poisoning cases.

Results: We identified a total of 622 patients (mean age: 32.9 years old; female: 51%) with acute CO poisoning in the study hospital. Carbon monoxide poisoning was associated with temperature (beta: −0.0973, rate ratio (RR): 0.9073, p < 0.0001) but not with relative humidity (beta: 0.1290, RR: 1.1377, p = 0.0513) or wind speed (beta: −0.4195, RR: 0.6574, p = 0.0806). In the subgroup analyses, temperature was associated with the incidence of intentional CO poisoning (beta: 0.1076, RR: 1.1136, p = 0.0333) in spring and unintentional CO poisoning (beta: −0.1865, RR: 0.8299, p = 0.0184) in winter.

Conclusion: Changes in temperature affect the incidence risk for acute CO poisoning, but the impact varies with different seasons and intentionality in Taiwan. Our findings quantify the effects of climate factors and provide fundamental evidence for healthcare providers to develop preventative strategies to reduce acute CO poisoning events.

Carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning is a global issue of great significance for public health and societal costs (1–4). According to worldwide epidemiological data, in 2017 the cumulative incidence and mortality rates of CO poisoning were about 137 cases and 4.6 deaths per one million person-years, respectively. Over the past 25 years, the worldwide incidence has remained stable, but the mortality rate has declined by 40% due to continued public health education and the improvement of treatment (5, 6). However, epidemiological features vary in different countries. According to statistics from Taiwan's government, and contrary to the global trend, the mortality rate of unintentional poisoning continued to increase from 1.6 to 3.5 per million person-years during the period of 1997–2003 in Taiwan (7, 8), which was mostly related to old piping and improper use of heating systems. Moreover, the incidence of intentional CO poisoning (e.g., charcoal-burning suicide) also surged from 0.22 to 9.8 per million person-years during 1999–2019 (9, 10), and this has now became the second most common cause of intentional deaths (11).

Identifying risk factors is vital to developing appropriate precautions and weather-related factors have been considered one of the most important risk factors for acute CO poisoning. A previous study by Tiekuan Du et al. in Beijing indicated that temperature was inversely correlated with the incidence of acute CO poisoning (r = −0.467) (12). Another study from Roca-Barceló Aina et al. in the UK also demonstrated clear seasonality in the incidence of acute CO poisoning (13). However, the risk factors may vary depending on the intention behind the CO poisoning; for example, unintentional CO poisonings probably related to improper installation of household heating systems (14) were associated with seasonal variations or particular weather conditions, such as colder seasons or sudden changes in temperature (15–17). Some specific demographics with high risk of intentional CO poisoning were identified as male patients (6), patients with psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression or schizophrenia) (18) and patients of unmarried status (8, 9, 19, 20). Thus, the study of CO poisoning cannot merely involve research of one specific region or any single risk factor.

However, current evidence regarding the risk factors for acute CO poisoning, especially through weather impacts has mostly come from Western countries (21, 22). The generalizability into Asian countries with different cultural and climatic patterns remains unclear. For example, the climate of Taiwan is warm (mean annual temperature: 24.6°C), rainy (mean rainy days: 146 days) and humid (mean relative humidity: 79.43%), so the weather impacts on CO poisoning in Taiwan may differ from previous reports. In addition, previous studies have mostly explored the association between temperature changes and CO poisoning, while the influence of other important weather factors (e.g., relative humidity and wind speed) on this issue remains unclear (12, 21). We therefore conducted this study to fill the knowledge gap and assist healthcare providers and policy makers to develop more strategies based on weather parameters to avoid intentional and unintentional CO poisoning.

We conducted a retrospective study by analyzing the electronic medical records of Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan from 2010 to 2015. Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital is the largest medical center in Taiwan, handling over 8,000 admissions monthly, and 17,000 and 330,000 patient visits for emergency and outpatient care, respectively. This study was approved by the Chang Gung Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board (IRB: CMRPG2E0091). Given the retrospective nature of this study, the need for informed consent was waived by the above mentioned committee.

We included adult patients diagnosed with acute CO poisoning, defined by carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) levels >5% in non-smokers and >10% in smokers (23), who were admitted or transferred to the emergency department of the study hospital. The COHb levels were measured by arterial blood gas at the initial medical institution or the Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. We excluded patients without complete information (e.g., incomplete documentation of medical records or transfer sheets).

We collected patients' demographics, including sex, age, past history of psychiatric diseases, marital status, coma scale upon arrival at the study hospital, sources of CO exposure, and intentional or unintentional purpose. This was performed by two clinical physicians (CHW and SCL) manually reviewing the electronic medical records or the medical transfer sheets. We obtained the mean values of daily weather parameters (e.g., temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed) during the study period from the Linkou weather station of the Central Weather Bureau of Taiwan, the official meteorological research and forecasting institution in Taiwan.

The primary outcomes were the effects from changes in daily mean temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed on the incidence of acute CO poisoning. We calculated the incidence of acute CO poisoning as the daily number of acute CO poisoning cases divided by the daily number of all patients seeking medical services in the emergency settings of the study hospital.

We compared baseline demographic characteristics in acute CO poisoning cases based on their intentionality (intentional or unintentional) using independent t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. We used negative binomial mixed models (NBMMs) to deal with the possible issue of over-dispersion while estimating the association between CO poisoning cases and environmental factors for correlated count data. Specifically, the environmental record of the year (i.e., 2010–2015) is included as a random factor and weather parameters are considered as fixed effects in the mixed model. To determine if the effects of weather parameters on the incidence of acute CO poisoning cases varied between intentional and unintentional poisonings and different seasons (i.e., spring, summer, fall, and winter), we also performed subgroup analyses based on intentionality and seasonality. We calculated the rate ratio (RR) of each weather parameter for the incidence of acute CO poisoning based on the multi-variable NBMMs. Moreover, we determined the variance inflation factor (VIF) to test for multicollinearity, and all VIF-values were <2, indicating low collinearity among weather parameters. All P-values were two-sided and those <0.05 were considered statistically significant. We performed analyses using SAS Enterprise statistical software (version 5.1).

During the period 2010–2015, we initially identified a total of 660 acute CO poisoning cases in the emergency settings in the study hospital. After excluding 38 cases due to incomplete data (Figure 1), we finally included in this study 622 CO poisoning cases with a mean age of 32.9 years old; 305 (49.0%) were male. We found 249 (40.0%) and 373 (60.0%) cases with intentional and non-intentional CO poisoning, respectively. The greatest differences between the intentional and the non-intentional CO poisoning groups were found in the source of CO poisoning (charcoal burning: 92.3 vs. 5.6%, p < 0.05; water heater incomplete combustion or incorrect use: 1.6 vs. 87.9%, p < 0.05) and the history of psychiatric diseases (42.6 vs. 1.6%, p < 0.05). Detailed comparisons of baseline characteristics in CO poisoning cases with different intentionality are listed in Table 1.

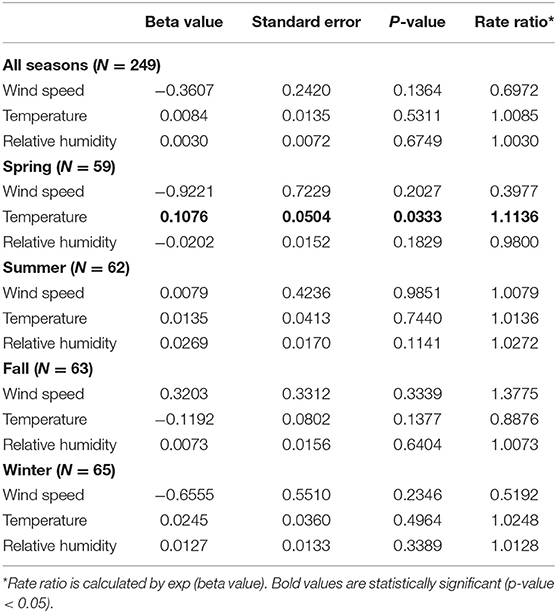

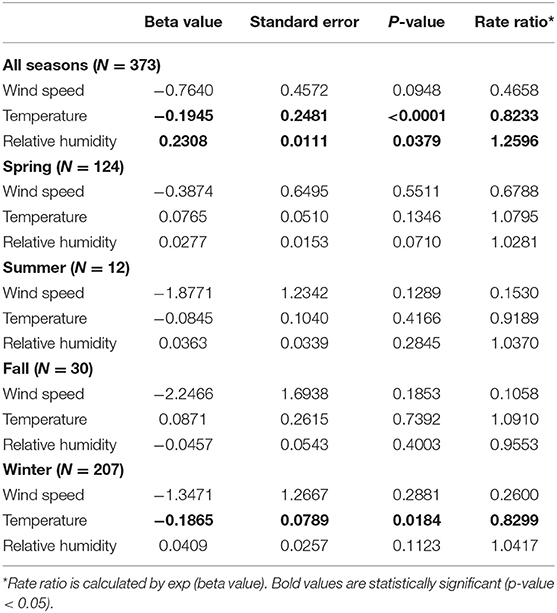

Overall, the NBMMs indicated that the temperature was significantly associated with the incidence of acute CO poisoning (beta: −0.0973, RR: 0.9073, p < 0.0001), and there were no significant associations between the relative humidity (beta: 0.1290, RR: 1.1377, p = 0.0513) or wind speed (beta: −0.4195, RR: 0.6574, p = 0.0806) and the incidence of acute CO poisoning (Table 2). However, the impact of weather changes on the incidence of acute CO poisoning varied, depending on whether the poisoning was intentional (Table 3) or unintentional (Table 4). No specific weather parameters associated with intentional CO poisoning were observed, but temperature (beta: −0.1945, RR: 0.8233, p < 0.0001) and relative humidity (beta: 0.2308, RR: 1.2596, p = 0.0379) were significantly associated with the incidence of unintentional CO poisoning. After the subgroup analyses according to different intentionality and seasons, temperature was associated with the incidence of intentional CO poisoning in spring (beta: 0.1076, RR: 1.1136, p = 0.0333) and unintentional CO poisoning during winter (beta: −0.1865, RR: 0.8299, p = 0.0184).

Table 3. Subgroup analyses of the changes of weather parameters on the incidence of intentional CO poisoning.

Table 4. Subgroup analyses of the changes of weather parameters on the incidence of unintentional CO poisoning.

Development of a local body of data regarding risk factors for CO poisoning has been crucial for reducing the incidence of CO poisoning. This study provides local data on CO poisoning in an Asian setting and demonstrates not only that weather changes could affect the incidence of acute CO poisoning, but also that climate impacts on CO poisoning vary, depending on the intentionality of the poisonings. We have quantified the relative effects of weather changes on CO poisoning, and our findings indicate that increased risks of unintentional CO poisoning are associated with lower temperature and higher relative humidity. However, no significant impacts of weather factors on intentional CO poisoning were observed in our study.

Several studies have illustrated that the incidence of CO poisoning varies with different seasons (13, 16, 24) and temperature changes are the leading risk factors. A previous study by Shie HG et al. in Taiwan found that while the daily maximum temperature was lower than 18.4°C, the odds ratio for unintentional CO poisoning incidence was increased 2.15 times, compared to the odds ratio when the temperature exceeded 27.1°C (8). Similarly, temperature changes were considered to be associated with the incidence of suicide attempts (25, 26). However, in a recent study the correlation between temperature changes and suicide incidence remained inconclusive, probably due to different regions or study designs (27). In our study, we not only found that lower temperature leads to higher risk of CO poisoning, but also that an increase of 1°C may lead to a 10% decrease in acute CO poisoning incidence. The higher incidence of unintentional CO poisoning at lower temperatures may be the result of people closing doors and windows to keep warm at home, thus preventing air circulation and increasing indoor CO levels, especially with improper installation of household heating systems. This tendency of linear association between temperature and CO poisoning events was also observed in other studies (12, 17), and may reflect the increasing probability of people staying indoors and using household heating systems as the weather gets colder.

Relative humidity reflects the moisture content of the atmosphere at a given temperature. Based on relevant studies in Taiwan, relative humidity has a significant impact on apparent temperature, especially in subtropical regions. Higher relative humidity in cold weather makes people feel it is colder than the actual temperature (28), which may in turn lead to increased heater usage. One study in Romania also revealed direct association between humidity and the CO concentration in the environment (29). However, studies by Du et al. and Ruan et al. have indicated that relative humidity in the domicile did not significantly affect the incidence of acute CO poisoning (12, 17). This inconsistency may stem from the fact that some previous studies failed to conduct subgroup analyses to evaluate relative humidity and CO poisoning with different intentions. In this study, our findings support that higher relative humidity is only associated with an increased risk of unintentional CO poisoning, but not of intentional CO poisoning.

Carbon monoxide tends to concentrate near its sources if wind speed is low, especially when it is under 1.3m/s (30). Hung et al. have indicated that higher wind speed and higher temperature were the most important climate factors to prevent acute CO poisoning occurrences (17). In our study, however, there was no correlation between wind speed and CO poisoning. This result implies that in CO poisoning events mostly attributed to indoor heating systems or charcoal burning, the outdoor wind speed had little effect on the indoor CO concentration if the indoor environment was poorly ventilated.

Seasonal variation in cases of CO poisoning was observed in one previous study in Korea (31). In our study, over 73% of CO poisoning cases happened during spring and winter with four times more CO poisoning cases in winter compared to summer. We also found correlation between temperature and intentional poisoning in spring and unintentional poisoning in winter after conducting subgroup analyses. The higher incidence of unintentional CO poisoning in winter is closely related to elevated indoor CO concentration from improper installation and use of heating systems.

In Taiwan, April and May are the rainy seasons; the weather is humid, hot, and unstable. Some studies have illustrated a significant seasonal variation in suicide attempts with a distinct seasonal pattern, especially in spring and autumn, found in females (32–34). Other researchers have documented a positive association between climate factors like the intensity of sunlight (longer day length), higher temperature, more humidity, and suicide (35, 36). As we know, serotonin concentration and tryptophan (the primary precursor of serotonin) levels in the brain are often associated with impulsive control and aggressive behaviors; both neurotransmitters show a prominent seasonal rhythm with lower plasma levels measured in spring in comparison to other seasons (37). These reasons may partly explain the increase in intentional CO poisoning in the spring, as the temperature rises, observed in our study.

Consistent with previous studies from Western countries, our study confirms the influence of temperature on CO poisoning in Taiwan (8, 16). Our study also recognizes that relative humidity is a further potential risk factor for unintentional CO poisoning, which has never been evaluated in previous studies. Our findings may be clinically important to build up a forecasting system for CO poisoning occurrences by incorporating weather parameters in the future. For example, when weather forecasts predict higher humidity and lower temperature approaching, we may issue weather warnings to remind the public to be aware of increased risks of CO poisoning and to take related measures (e.g., opening windows, being cautious with heating systems) in advance.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting quantitative risk evaluations of several weather parameters on CO poisoning incidence in Taiwan. Most importantly, we conducted subgroup analyses based on the intentionality of CO poisoning, and found the effects of weather changes on CO poisoning differed, depending on the intention behind the poisoning. However, our findings should be interpreted cautiously due to the nature of retrospective studies. First, we did not evaluate other risk factors of CO poisoning, since we only focused on weather changes in this study. Second, we only used the daily mean values of weather parameters to evaluate the risks of CO poisoning, but weather parameters undergo huge variations in Taiwan. Third, cigarette smoking was a special issue, since smokers often have higher COHb levels. However, it was not always feasible to identify smokers in our routine clinical practice. In our study, 21% (131/622) of the patients were identified as smokers, but for the majority of the patients uncertainty about their smoking status remained, which hindered further analysis. Fourth, although this study was drawn from the largest medical center in Taiwan, climate effects on CO poisoning are regionally highly variable. The generalizability of the result is subject to regional considerations and should be further confirmed in other medical institutions. Finally, this city-based study depicted the situation of CO intoxication in northern Taiwan. The results should be interpreted with caution if applying to individuals.

Changes in daily mean temperature and relative humidity affect the incidence of unintentional CO poisoning, but not of intentional CO poisoning in Taiwan. Our findings quantified the effects of climate factors and provided fundamental evidence for healthcare providers and policy makers to develop preventative strategies based on weather changes and patient's intentions to reduce acute CO poisoning events.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

S-CL and S-CS: conceptualization, review, and editing. S-CL, S-CS, K-CC, and C-HW: methodology. S-CS, K-CC, and C-HW: data curation, investigation, and formal analysis. C-HW: original draft and visualization. S-CL: funding acquisition. M-JH, C-CY, and S-CL: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The work was funded by Chang Gung Medical Foundation (grant number: CMRPG2E0091).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors are grateful to the Central Weather Bureau of Taiwan for the assistance in the collection of data of the weather parameters and thank Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan for providing valuable cause of death data and statistics.

1. Hampson NB. Cost of accidental carbon monoxide poisoning: a preventable expense. Prev Med Rep. (2016) 3:21–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.11.010

2. Braubach M, Algoet A, Beaton M, Lauriou S, Héroux ME, Krzyzanowski M. Mortality associated with exposure to carbon monoxide in WHO European Member States. Indoor Air. (2013) 23:115–25. doi: 10.1111/ina.12007

3. Iqbal S, Law HZ, Clower JH, Yip FY, Elixhauser A. Hospital burden of unintentional carbon monoxide poisoning in the United States, 2007. Am J Emerg Med. (2012) 30:657–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.03.003

4. Ran T, Nurmagambetov T, Sircar K. Economic implications of unintentional carbon monoxide poisoning in the United States and the cost and benefit of CO detectors. Am J Emerg Med. (2018) 36:414–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.08.048

5. Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G. Worldwide epidemiology of carbon monoxide poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. (2020) 39:387–92. doi: 10.1177/0960327119891214

6. Hampson NBUS. Mortality due to carbon monoxide poisoning, 1999-2014. Accidental and intentional deaths. Ann Am Thorac Soc. (2016) 13:1768–74. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201604-318OC

7. Ku CH, Hung HM, Leong WC, Chen HH, Lin JL, Huang WH, et al. Outcome of patients with carbon monoxide poisoning at a far-east poison center. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0118995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118995

8. Shie HG, Li CY. Population-based case-control study of risk factors for unintentional mortality from carbon monoxide poisoning in Taiwan. Inhal Toxicol. (2007) 19:905–12. doi: 10.1080/08958370701432173

9. Pan YJ, Liao SC, Lee MB. Suicide by charcoal burning in Taiwan, 1995-2006. J Affect Disord. (2010) 120:254–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.003

10. Lin C, Yen TH, Juang YY, Leong WC, Hung HM, Ku CH, et al. Comorbid psychiatric diagnoses in suicide attempt by charcoal burning: a 10-year study in a general hospital in Taiwan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2012) 34:552–6. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.03.015

11. Chien WC, Lin JD, Lai CH, Chung CH, Hung YC. Trends in poisoning hospitalization and mortality in Taiwan, 1999-2008: a retrospective analysis. BMC Public Health. (2011) 11:703. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-703

12. Du T, Zhang Y, Wu JS, Wang H, Ji X, Xu T, et al. Domicile-related carbon monoxide poisoning in cold months and its relation with climatic factors. Am J Emerg Med. (2010) 28:928–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.06.019

13. Roca-Barceló A, Crabbe H, Ghosh R, Freni-Sterrantino A, Fletcher T, Leonardi G, et al. Temporal trends and demographic risk factors for hospital admissions due to carbon monoxide poisoning in England. Prev Med. (2020) 136:106104. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106104

14. Kao LW, Nañagas KA. Toxicity associated with carbon monoxide. Clin Lab Med. (2006) 26:99–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2006.01.005

15. Sheikhazadi A, Saberi Anary SH, Ghadyani MH. Nonfire carbon monoxide-related deaths: a survey in Tehran, Iran (2002-2006). Am J Forensic Med Pathol. (2010) 31:359–63. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181f23e02

16. Hung DZ, Deng JF, Yang CC, Jen LY. The climate and the occurrence of carbon monoxide poisoning in Taiwan. Hum Exp Toxicol. (1994) 13:493–5. doi: 10.1177/096032719401300707

17. Ruan HL, Deng WS, Wang Y, Chen JB, Hong WL, Ye SS, et al. Carbon monoxide poisoning: a prediction model using meteorological factors and air pollutant. BMC Proc. (2021) 15:1. doi: 10.1186/s12919-021-00206-7

18. Huang CC, Ho CH, Chen YC, Lin HJ, Hsu CC, Wang JJ, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of carbon monoxide poisoning: nationwide data between 1999 and 2012 in Taiwan. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. (2017) 25:70. doi: 10.1186/s13049-017-0416-7

19. Choi YR, Cha ES, Chang SS, Khang YH, Lee WJ. Suicide from carbon monoxide poisoning in South Korea: 2006-2012. J Affect Disord. (2014) 167:322–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.026

20. Hosseininejad SM, Aminiahidashti H, Goli Khatir I, Ghasempouri SK, Jabbari A, Khandashpour M. Carbon monoxide poisoning in Iran during 1999-2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Forensic Leg Med. (2018) 53:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2017.11.008

21. Ghosh RE, Close R, McCann LJ, Crabbe H, Garwood K, Hansell AL, et al. Analysis of hospital admissions due to accidental non-fire-related carbon monoxide poisoning in England, between 2001 and 2010. J Public Health (Oxf). (2016) 38:76–83. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv026

22. Salameh S, Amitai Y, Antopolsky M, Rott D, Stalnicowicz R. Carbon monoxide poisoning in Jerusalem: epidemiology and risk factors. Clin Toxicol (Phila). (2009) 47:137–41. doi: 10.1080/15563650801986711

23. Veiraiah A. Carbon monoxide poisoning. Medicine. (2020) 48:197–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2019.12.013

24. Nazari J, Dianat I, Stedmon A. Unintentional carbon monoxide poisoning in Northwest Iran: a 5-year study. J Forensic Leg Med. (2010) 17:388–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2010.08.003

25. Geltzer AJ, Geltzer AM, Dunford RG, Hampson NB. Effects of weather on incidence of attempted suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning. Undersea Hyperb Med. (2000) 27:9–14.

26. Burke M, González F, Baylis P, Heft-Neal S, Baysan C, Basu S, et al. Higher temperatures increase suicide rates in the United States and Mexico. Nat Clim Chang. (2018) 8:723–9. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0222-x

27. Pervilhac C, Schoilew K, Znoj H, Müller TJ. [Weather and suicide: association between meteorological variables and suicidal behavior-a systematic qualitative review article]. Nervenarzt. (2020) 91:227–32. doi: 10.1007/s00115-019-00795-x

28. Huang C-H, Tsai H-H. Chen H-c. Influence of weather factors on thermal comfort in subtropical urban environments. Sustainability. (2020) 12:2001. doi: 10.3390/su12052001

29. Barbulescu A, Barbes L. Modeling the carbon monoxide dissipation in Timisoara, Romania. J Environ Manage. (2017) 204(Pt 3):831–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.02.047

30. Rozante JR, Rozante V, Souza Alvim D, Ocimar Manzi A, Barboza Chiquetto J, Siqueira D'Amelio MT, et al. Variations of carbon monoxide concentrations in the megacity of São Paulo from 2000 to 2015 in different time scales. Atmosphere. (2017) 8:81. doi: 10.3390/atmos8050081

31. Kim YS. Seasonal variation in carbon monoxide poisoning in urban Korea. J Epidemiol Community Health. (1985) 39:79–81. doi: 10.1136/jech.39.1.79

32. Morken G, Lilleeng S, Linaker OM. Seasonal variation in suicides and in admissions to hospital for mania and depression. J Affect Disord. (2002) 69:39–45. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00373-6

33. Yip PS, Yang KCA. comparison of seasonal variation between suicide deaths and attempts in Hong Kong SAR. J Affect Disord. (2004) 81:251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.09.001

34. Benard V, Geoffroy PA, Bellivier F. [Seasons, circadian rhythms, sleep and suicidal behaviors vulnerability]. Encephale. (2015) 41(4 Suppl 1):S29–37. doi: 10.1016/S0013-7006(15)30004-X

35. Rock D, Greenberg DM, Hallmayer JF. Increasing seasonality of suicide in Australia 1970-1999. Psychiatry Res. (2003) 120:43–51. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(03)00165-3

36. Volpe FM, Tavares A, Del Porto JA. Seasonality of three dimensions of mania: psychosis, aggression and suicidality. J Affect Disord. (2008) 108:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.09.014

Keywords: carbon monoxide poisoning, accidental poisoning, weather warnings, weather parameters, climate factors, climate effects on CO poisoning

Citation: Wang C-H, Shao S-C, Chang K-C, Hung M-J, Yang C-C and Liao S-C (2021) Quantifying the Effects of Climate Factors on Carbon Monoxide Poisoning: A Retrospective Study in Taiwan. Front. Public Health 9:718846. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.718846

Received: 01 June 2021; Accepted: 20 September 2021;

Published: 14 October 2021.

Edited by:

Xerxes Seposo, Nagasaki University, JapanReviewed by:

Erica Ponzi, University of Oslo, NorwayCopyright © 2021 Wang, Shao, Chang, Hung, Yang and Liao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shu-Chen Liao, ZXJtZHN1c2FuQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.