95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 14 June 2021

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.667729

This article is part of the Research Topic Knock-on Mental Health Effects of Substance and Drug Use as a Coping Strategy View all 7 articles

Tore Bonsaksen1,2*

Tore Bonsaksen1,2* Øivind Ekeberg3

Øivind Ekeberg3 Inger Schou-Bredal4,5

Inger Schou-Bredal4,5 Laila Skogstad6,7

Laila Skogstad6,7 Trond Heir8,9

Trond Heir8,9 Tine K. Grimholt10,11

Tine K. Grimholt10,11Background: The outbreak of COVID-19 has had a major impact on people's daily life. This study aimed to examine use of alcohol and addictive drugs during the COVID-19 outbreak in Norway and examine their association with mental health problems and problems related to the pandemic.

Methods: A sample of 4,527 persons responded to the survey. Use of alcohol and addictive drugs were cross-tabulated with sociodemographic variables, mental health problems, and problems related to COVID-19. Logistic regression analyses were used to examine the strength of the associations.

Results: Daily use of alcohol was associated with depression and expecting financial loss in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak. Use of cannabis was associated with expecting financial loss in relation to COVID-19. Use of sedatives was associated with anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Use of painkillers was associated with insomnia and self-reported risk of complications if contracting the coronavirus.

Conclusion: The occurrence of mental health problems is more important for an understanding of the use of alcohol and addictive drugs during the COVID-19 outbreak in Norway, compared to specific pandemic-related worries.

The outbreak of COVID-19 has had a major impact on people's daily life. To prevent the spread of the coronavirus disease, strict policies have emphasized keeping a physical distance to other people, commonly known as social distancing (1, 2). These policies introduced abrupt changes in economic life. Most travels and events were canceled, and non-vital businesses were closed. Consequently, financial problems suddenly became a reality for many businesses, many employees were temporarily furloughed from their jobs (3) and unemployment rates increased rapidly (4). During this time, there has been a worldwide growing concern that living under restrictive social distancing policies and a general sense of uncertainty may have a profound impact on the mental health of the population (5–8).

While the use of various pharmaceuticals generally reflects the burden of disease in a society, the use of alcohol and addictive drugs may also vary according to changes in environmental conditions. Thus, the use of these substances may be expected to rise during difficult times, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies of healthcare personnel during previous infectious disease outbreaks have shown alcohol use to be higher among those who worked in high-risk locations and situations, compared to those who worked in low-risk situations (9, 10). Moreover, during the current COVID-19 crisis, evidence of increased alcohol use in the general population (11), as well as a higher demand for cannabis products on the darknet (12), have been found.

Recent studies based on data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic have demonstrated associations between higher alcohol use and middle age, higher income, job loss, stress, sleep problems, and depression (13). Thus, the use of alcohol may be associated with distal (sociodemographic factors, mental health) and proximal factors (circumstances evoked by the COVID-19 situation) alike. While mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety, have been linked with increased alcohol use during the pandemic (14), the consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak (e.g., fear of virus transmission, loneliness, and financial problems) may be related to increased use of alcohol and other substances. Thus, to increase the understanding of use of alcohol and addictive drugs in the COVID-19 context, the explanatory power of a wider range of variables related to the pandemic's consequences needs to be considered. However, we are unaware of similar population studies concerned with the use of multiple addictive drugs during the COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, while recent studies have examined the prevalence of use of alcohol and addictive drugs in the general Norwegian population (15), such studies may not reflect the use of such substances during extraordinary circumstances such as the current pandemic. The aims of the study were to examine use of alcohol and addictive drugs during the COVID-19 outbreak and examine their association with mental health problems and problems related to the pandemic.

A population-based cross-sectional study that dealt with reactions in the Norwegian population after the COVID-19 outbreak (the CORONAPOP study) (16, 17), was conducted with a web-link open to all citizens between April 8th, 2020 and May 20th, 2020. The web-link was hosted and disseminated by several institutions, including Oslo University Hospital, Sunnaas Rehabilitation Hospital, University of Oslo, and Oslo Metropolitan University. The link to the survey was further disseminated on social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram, by the individual researchers and other individuals who wanted to share the link to the survey. The study was also featured in national and local newspapers.

Norwegian citizens aged 18 years or older were invited to participate. There were no exclusion criteria.

Sociodemographic and health-related data were collected as self-report measures via the web-based survey. The survey employed several measures identical to the ones used in the Norwegian population health survey (the NORPOP study), which was conducted as a postal survey in 2014–2015 (18–21). New questions pertaining to the possible concerns and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic were developed by the research group at the time of the pandemic outbreak.

Data were collected for age group (18–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years, and 70 years or older) gender (male/female), highest completed education level (elementary school, high school, <4 years of higher education, and 4 years of higher education or more), employment status (working/in education vs. not), cohabitation status (living with spouse or partner vs. not), and living with children (living with children under the age of 18 years vs. not). Size of place of residence was categorized as <200 inhabitants, 200–19.999 inhabitants, 20.000–99.999 inhabitants, and 100.000 inhabitants or more. In Norway, a significant part of the population lives in rural areas. The categories were made considering that about 20–30% of the population belong to each of the categories, and the NORPOP study (18–21) used the same categories.

We used the phrase: “Use of alcohol and addictive drugs and pharmaceuticals: have you used any of these?” Below was a list containing alcohol, cannabis, sedatives, and painkillers/opioids, with examples provided for sedatives and painkillers/opioids. Response options were “no,” “sometimes,” “weekly,” “daily,” and “several times daily.” Participants who reported that they used alcohol daily were classified as daily drinkers. Participants who reported that they (had) used cannabis, sedatives or painkillers/opioids “sometimes” or more often, were classified as “sometimes, weekly or daily” (S/W/D) users of the relevant substance.

We used the phrase: “Below is a list of health problems. Do you have, or have you had, any of these?” Among the listed problems were anxiety, depression, insomnia, and suicide thoughts. The response alternatives were “no,” “yes previously, but not during the last month” and “yes, during the last month.” Those who confirmed having one or more of the listed health problems during the last month were classified as currently having the relevant mental health problems.

Relating to the COVID-19 situation, participants were asked to respond “yes” or “no” to the following questions: (a) “Are you suffering, or do you think you will be suffering, economic loss?”, (b) “Have you been in quarantine or in isolation due to the corona virus?”, (c) “Are you at risk of experiencing complications from COVID-19?”, and (d) “Do you have friends or close family that you worry about?” Participants who indicated “yes” on any of these questions were classified as “experiencing/expecting economic loss,” “experienced quarantine/isolation,” “risk of complication,” and/or “worry about friends/family,” respectively.

Frequencies and proportions (%) were calculated for all categorical variables, and all were cross tabulated with the occurrence of daily alcohol use, and with sometimes/weekly/daily use of cannabis, sedatives, and painkillers. Single and multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to assess associations between sociodemographic variables, mental health problems and COVID-19 related problems, and the use of substances. In the multiple logistic regression analyses, all independent variables were entered together in order to cancel out the effects of covariation between the independent variables. Post-hoc interaction analyses were performed for alcohol use to assess whether significant associations were dependent on levels of sociodemographic variables showing skewed distributions (i.e., age group, gender, education, and size of place of residence). Interaction terms were included separately in a second step of the analysis, while adjusting for sociodemographic variables, mental health problems and COVID-19 related problems. For alcohol, we distinguished between daily use (1) vs. less frequent or no use (0). For cannabis, sedatives, and painkillers, we distinguished between sometimes/weekly/daily use (1) vs. no use (0). Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported. IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (22) was used for statistical analyses, and the significance level was set at 5%.

The questionnaires were answered anonymously. Ethical approval for conducting the study was granted from the Regional Committee for Medical and Healthcare Ethics (REK no. 130447).

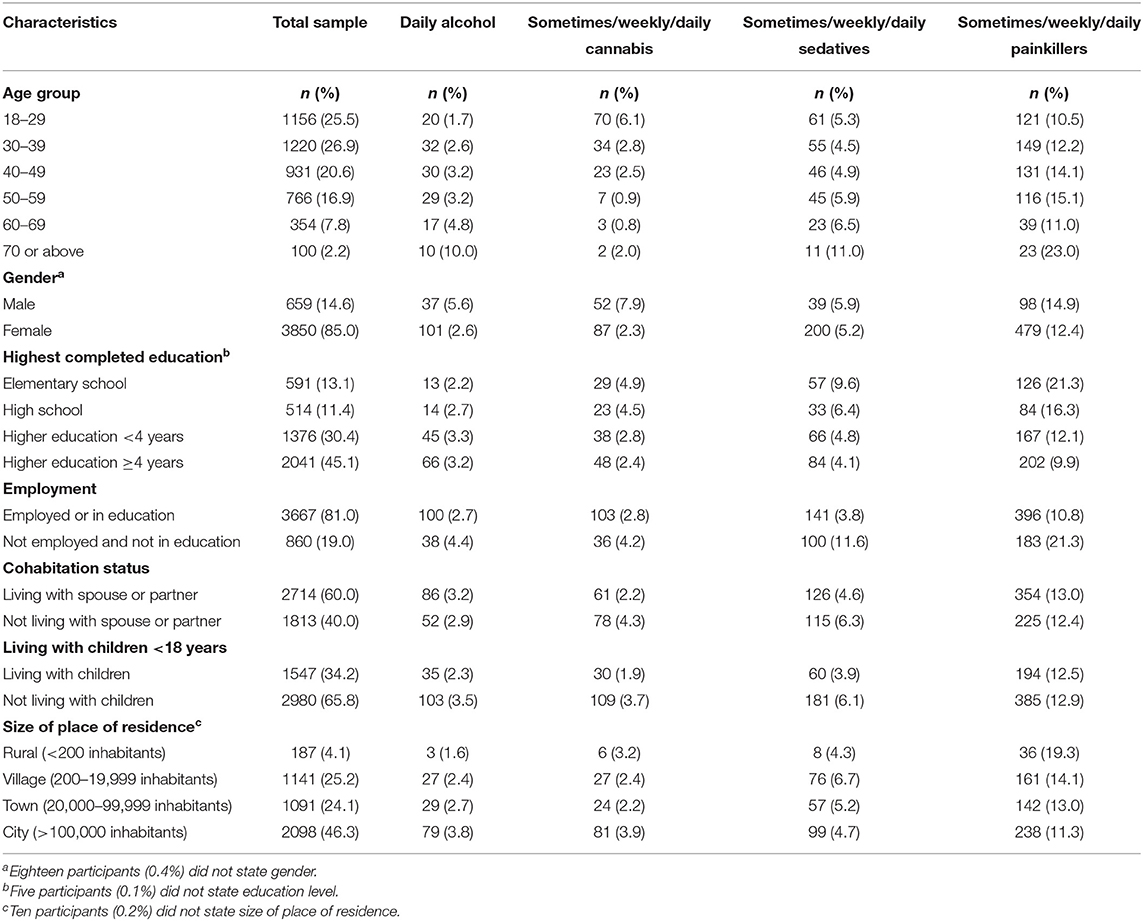

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample is displayed in Table 1. More than half of the sample was under 40 years of age, and the number of participants was lower in the higher age groups. A majority were women (85.0%), had higher education (75.5%) and were employed or in education (81.0%). Current anxiety and depression were reported by 17.1 and 12.5%, respectively, while 31.8% reported insomnia. A smaller proportion (3.6%) reported having had suicide thoughts during the last month, while the larger proportion (61.7%) reported having none of the listed mental health problems. With regards to COVID-19, 25.3% expected to suffer financial loss, 28.3% had been quarantined or in isolation and 23.4% reported to be at risk of experiencing complications if contracting the coronavirus. The large majority (83.9%) were worried about someone close to them.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (n = 4,527), among daily users of alcohol (n = 138) and among sometimes/weekly/daily users of cannabis (n = 139), sedatives (n = 241), and painkillers (n = 579).

As shown from the multiple logistic regression analysis in Table 2, the odds of using alcohol daily were higher for those of higher age (OR: 1.31, p < 0.001) and among those with higher education (OR: 1.61, p < 0.05), and lower among women than men (OR: 0.50, p < 0.01). Daily use of alcohol was also associated with depression (OR: 3.40, p < 0.001) and with expecting financial loss in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak (OR: 1.66, p < 0.01).

The post-hoc analyses revealed a significant interaction between age group and depression (p = 0.02). Cross tabulating depression and daily alcohol use for each of the age groups revealed a significant association for participants aged 18–29 years (ϕ = 0.15, p < 0.001), 30–39 years (ϕ = 0.15, p < 0.001), and 40–49 years (ϕ = 0.13, p < 0.001), while the association was not significant for participants in the older age groups. Thus, depression was more strongly related to daily alcohol use in the younger age groups. None of the other tested interaction terms were found to be statistically significant.

As shown from the multiple logistic regression analysis in Table 3, the odds of using cannabis were lower for those of higher age (OR: 0.53, p < 0.001) and among women (OR: 0.19, p < 0.001). The odds of using cannabis were higher among those who expected financial loss in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak (OR: 1.62, p < 0.05).

As shown from the multiple logistic regression analysis in Table 4, the odds of using sedatives were higher for those of higher age (OR: 1.17, p < 0.01) and lower among those having employment (OR: 0.58, p < 0.01). Use of sedatives was also associated with anxiety (OR: 4.76, p < 0.001), depression (OR: 1.64, p < 0.01), and insomnia (OR: 2.15, p < 0.001).

As shown from the multiple logistic regression analysis in Table 5, the odds of using painkillers were lower for those with higher education (OR: 0.64, p < 0.001) and those with employment (OR: 0.66, p < 0.001). Use of painkillers was also associated with insomnia (OR: 1.48, p < 0.001) and reporting risk of complications if contracting the coronavirus (OR: 1.57, p < 0.001).

This study examined use of alcohol and addictive drugs in the Norwegian population during the COVID-19 outbreak and examined the substance use in association with mental health problems and problems related to the pandemic. The occurrence of mental health problems was found to be more important for an understanding of the use of alcohol and addictive drugs during the COVID-19 outbreak, compared to specific pandemic-related worries.

Daily use of alcohol was associated with expecting financial loss in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak. Some people may have felt that their lives had been turned upside down regardless of the consequence for their personal economy, while others have lost their jobs, or they lived in constant fear of losing it (3). The expectance of financial loss may be frequently occurring among people employed with private sector jobs that were strongly affected by market fluctuations, which may translate into an increased risk of losing their job. Many businesses in Norway were temporarily closed at the onset of COVID-19, resulting in a rapid increase in unemployment rates (4). The consequences were particularly severe for people employed in the transportation and tourism industries, for which unemployment rates were twice as high compared to other industries (4). Although one might assume a relationship between the expectance of financial loss and depression, the results substantiated an association between expecting financial loss and daily use of alcohol that was independent of depression.

Adjusted for all variables, daily use of alcohol retained its association with depression. The detected association between alcohol use and depression is in line with a range of studies (23), including a recent Norwegian population study in which having anxiety or depression was associated with daily alcohol use (24). Thus, use of alcohol appears to be relatively independent from external circumstances. As demonstrated by Ertl et al. (25), alcohol use in the context of mental health problems may be linked with relief-oriented motives for drinking, as opposed to reward-oriented motives. In their study, more psychopathology was associated with relief-oriented drinking motives. It is possible that relief-oriented drinking may increase during crises as many people struggle with stress reactions to the crisis. The results from the post-hoc interaction analyses suggest that this may more often be the case among people in the younger age groups. A study from Finland showed that more psychological symptoms predicted a pattern of heavy drinking from adolescence to midlife (26). Although the cross-sectional design of this study prohibits concluding about the direction of the association, depression appears to be consistently linked with heavy and frequent use of alcohol during the COVID-19 outbreak, as shown in other countries alike (13). Lastly, we noted the association between higher education levels and higher odds of daily use of alcohol. While this indicates that a high-frequent drinking pattern is more common among those with higher education, it does not necessarily point toward more alcohol-related problems in this group.

Use of cannabis was associated with expecting financial loss in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak. Cannabis use was also associated with younger age, a finding which is in line with previous Norwegian population studies (27). Generally, young people are often employed in part-time jobs while undergoing education—in Norway, one in three full-time students have part time jobs (28). Moreover, they often have jobs in the retail and service industries such as shops and restaurants, which might be particularly affected by crises such as the COVID-19 outbreak. Thus, people of young age are generally in a vulnerable economic situation which may become even worse with the potential loss of a job.

Use of sedatives was associated with anxiety, depression, and insomnia. This result appears to reflect that sedatives are commonly used pharmaceuticals for mental disorders in general (29). It is also consistent with the findings in a recent general population study from Norway (15), demonstrating higher relative risk of a wide range of disorders, including anxiety, depression and insomnia, for people who had used sedatives sometimes or more often.

Use of painkillers was associated with insomnia and reporting risk of complications if contracting the coronavirus. Sleep and pain have been shown to have a bidirectional relationship—sleep problems can be caused by pain, while better sleep can reduce pain (30). For people experiencing pain, the use of painkillers can therefore be a logical means to regaining sleep. Use of painkillers have also been shown to be associated with higher risk of a wide range of diseases, including pulmonary disease and cancer (15). As these diseases are often painful (31, 32) and constitute increased risk of fatal outcome if the person is exposed to COVID-19 infection, the occurrence of these and similar pain-inducing diseases may contribute to explain the association between perceived risk of complications and use of painkillers.

The cross-sectional survey design precludes us from establishing causal relationships between the variables under study; the study is therefore limited in its mere detection of statistical associations between mental health problems and problems relating to the COVID-19, and the use of alcohol and addictive drugs. To overcome some of the limitations related to a cross-sectional study design, future studies may include follow-up assessments that will allow for studying how the use of alcohol and drugs develops over time, and how their use may be related to a range of specific exposures.

While a range of variables were used as possible predictors of substance use, other variables—not accounted for in this study—might have added to the explanatory power of the statistical model. Such variables may include confinement at home, working from home, spending more time together at home, home conflicts, and having children at home during daytime. Possibly, the consumption of substances would be related to these situations. Alternatively, these situations may increase the risk of mental health problems, which in turn was found to be related to use of substances.

The use of standard mental health measurements might have been a preferred option to our use of single-item scales, and future studies may include the use of standardized measures such as the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (33, 34). The recently developed Fear of COVID-19 Scale has shown to be promising (35), and the Norwegian version of the scale may also be serviceable (36). However, standard measurements are generally longer and place a larger burden on participants, especially when used in context of a larger survey. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that the use of single-item measures can be a valid and reliable option for measuring mental health phenomena (37–40). Similarly, with regards to alcohol use, measuring the quantity of drinking in addition to the frequency of drinking may have provided a more comprehensive estimate of risky drinking. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that high-frequent drinking is associated with increased health risk, even in the case of moderate consumption (41, 42).

The recruitment strategy was based on disseminating the link to the survey via various social media, and the strategy makes generalizing the results to the general population impossible due to selection bias. In fact, the sample was dominated by young, urban, and highly educated persons, and the vast majority were female. Among the general population in Norway, a significant part lives in rural areas, but this rural population was underrepresented in this study. Therefore, one should be cautious when comparing prevalence rates related to the use of alcohol and addictive drugs to previously established prevalence rates in the general population. In comparison to previously established prevalence rates (15, 24), it appears that the rate of daily alcohol use is similar, whereas the rates of “sometimes/weekly/daily” use of cannabis, sedatives, and painkillers are lower in this study. However, it has been argued that skewed samples are more prone to affect prevalence rates of substance use, while less prone to affect associations between predictors and substance use outcomes (43, 44). The post-hoc interaction analyses conducted with regards to alcohol use in this study were largely in line with this view. The relatively large sample size and the possibility to compare the results from the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak with a previous general population study (NORPOP) are strengths of the study. However, we stress that the study was conducted exclusively with participants living in Norway, which makes it impossible to transfer the conclusions of the study to other countries. Similar studies conducted in other countries and settings are therefore warranted.

Compared to specific pandemic-related worries, the occurrence of mental health problems was found to be more important for the use of alcohol and addictive drugs during the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in Norway. Depression was associated with daily use of alcohol, while several mental health problems including depression, anxiety, and insomnia were associated with use of sedatives. Worries specifically related to the COVID-19 outbreak were of less importance in relation to the use of alcohol and addictive drugs. While the results of a population survey do not warrant direct application to individual clients with alcohol or drug problems, the study indicates that mental health problems constitute an important context for the use of alcohol and addictive drugs during the pandemic. Public health initiatives aimed at reducing harmful use of alcohol and drugs should therefore consider the occurrence of mental health problems in the targeted population. Conversely, increased incidence of mental health problems in a population may warrant further assessment of service needs related to substance use.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, upon completion of the research project.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Regional Committee for Medical and Healthcare Ethics. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

TB, TH, IS-B, ØE, LS, and TG: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, and writing—review and editing. TB: formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization. TG: project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Open Access fees were funded by Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Elverum, Norway.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors thank the study participants for their participation.

1. Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health Specifies Advice on Social Distancing. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of Public Health (2020). Available online at: https://www.fhi.no/nyheter/2020/fhi-presiserer-rad-om-sosial-distansering/ (accessed March 1, 2021).

2. Ministry of Health. Regulation on Interventions to Prevent the Spread of Contagious Disease Etc. by the Corona Outbreak. Oslo: Ministry of Health (2020)

3. Blustein DL, Duffy R, Ferreira JA, Cohen-Scali V, Cinamon RG, Allan BA. Unemployment in the time of COVID-19: a research agenda. J Voc Behav. (2020) 119:103436. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103436

4. Statista. Unemployment Rate After the Coronavirus Outbreak in Norway in 2020 by Industry. (2020). Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1113595/unemployment-rate-after-the-coronavirus-outbreak-in-norway-by-occupation/ (accessed March 1, 2021).

5. Serafini G, Parmigiani B, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Sher L, Amore M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM Int J Med. (2020) 113:531–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201

6. Haider I, Tiwana F, Tahir S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adult mental health. Pak J Med Sci. (2020) 36:S90–4. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2756

7. Mi L, Jiang Y, Xuan H, Zhou Y. Mental health and psychological impact of COVID-19: Potential high-risk factors among different groups. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 53:102212. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102212

8. Kaufman KR, Petkova E, Bhui KS, Schulze TG. A global needs assessment in times of a global crisis: world psychiatry response to the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open. (2020) 6:e48. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.25

9. Brooks SK, Dunn R, Amlôt R, Rubin GJ, Greenberg N. A systematic, thematic review of social and occupational factors associated with psychological outcomes in healthcare employees during an infectious disease outbreak. J Occup Environ Med. (2018) 60:248–57. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001235

10. Wu P, Liu X, Fang Y, Fan B, Fuller CJ, Guan Z, et al. Alcohol abuse/dependence symptoms among hospital employees exposed to a SARS outbreak. Alcohol Alcohol. (2008) 43:706–12. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn073

11. Capasso A, Jones AM, Ali SH, Foreman J, Tozan Y, DiClemente RJ. Increased alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic: the effect of mental health and age in a cross-sectional sample of social media users in the U.S. Prev Med. (2021) 145:106422. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106422

12. Groshkova T, Stoian T, Cunningham A, Griffiths P, Singleton N, Sedefov R. Will the current COVID-19 pandemic impact on long-term cannabis buying practices? J Addict Med. (2020) 14:e13–e4. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000698

13. Neill E, Meyer D, Toh WL, van Rheenen TE, Phillipou A, Tan EJ, et al. Alcohol use in Australia during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic: initial results from the COLLATE project. Psych Clin Neurosci. (2020) 74:542–9. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13099

14. Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Alcohol and depression. Addiction. (2011) 106:906–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03351.x

15. Bonsaksen T, Skogstad L, Grimholt TK, Heir T, Ekeberg Ø, Lerdal A, et al. Substance use in the Norwegian general population: prevalence and associations with disease (early online). J Subst Use. (2020) 26:144–50. doi: 10.1080/14659891.2020.1784303

16. Bonsaksen T, Heir T, Schou-Bredal I, Ekeberg Ø, Skogstad L, Grimholt TK. Post-traumatic stress disorder and associated factors during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:9210. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249210

17. Schou-Bredal I, Grimholt T, Bonsaksen T, Skogstad L, Heir T, Ekeberg Ø. Optimists' and pessimists' self-reported mental and global health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway (early online). Health Psychol Rep. (2021) 1–9. doi: 10.5114/hpr.2021.102394. [Epub ahead of print].

18. Bonsaksen T, Ekeberg Ø, Skogstad L, Heir T, Grimholt TK, Lerdal A, et al. Self-rated global health in the Norwegian general population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2019) 17:188. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1258-y

19. Grimholt TK, Bonsaksen T, Schou-Bredal I, Heir T, Lerdal A, Skogstad L, et al. Flight anxiety reported from 1986 to 2015. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. (2019) 90:384–8. doi: 10.3357/AMHP.5125.2019

20. Heir T, Bonsaksen T, Grimholt T, Ekeberg Ø, Skogstad L, Lerdal A, et al. Serious life events and post-traumatic stress disorder in the Norwegian population. Br J Psych Open. (2019) 5:e82. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.62

21. Schou-Bredal I, Heir T, Skogstad L, Bonsaksen T, Lerdal A, Grimholt T, et al. Population-based norms of the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R). Int J Clin Health Psychol. (2017) 17:216–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.07.005

23. Conner KR, Pinquart M, Gamble SA. Meta-analysis of depression and substance use among individuals with alcohol use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. (2009) 37:127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.11.007

24. Bonsaksen T, Heir T, Skogstad L, Grimholt TK, Ekeberg Ø, Lerdal A, et al. Daily use of alcohol in the Norwegian general population: prevalence and associated factors. Drugs Alcohol Today. (2020) 20:109–21. doi: 10.1108/DAT-02-2020-0010

25. Ertl V, Preuße M, Neuner F. Are drinking motives universal? Characteristics of motive types in alcohol-dependent men from two diverse populations. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9:38. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00038

26. Berg NJ, Kiviruusu OH, Lintonen TP, Huurre TM. Longitudinal prospective associations between psychological symptoms and heavy episodic drinking from adolescence to midlife. Scand J Public Health. (2018) 47:420–7. doi: 10.1177/1403494818769174

27. Skretting A, Bye EK, Vedøy TF, Lund KE. Substances in Norway 2016 [Rusmidler i Norge 2016]. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of Public Health (2016).

28. Statistics Norway. Too Much Time Spent on Paid Work Leads to a Reduction in Study Time. Oslo: Statistics Norway (2017). Available online at: https://www.ssb.no/en/utdanning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/too-much-time-spent-on-paid-work-leads-to-a-reduction-in-study-time (accessed March 1, 2021).

29. Creado S, Plante DT. An update on the use of sedative-hypnotic medications in psychiatric disorders. Curr Psych Rep. (2016) 18:78. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0717-y

30. Bohra MH, Kaushik C, Temple D, Chung SA, Shapiro CM. Weighing the balance: how analgesics used in chronic pain influence sleep? Br J Pain. (2014) 8:107–18. doi: 10.1177/2049463714525355

31. Bentsen SB, Miaskowski C, Cooper BA, Christensen VL, Henriksen AH, Holm AM, et al. Distinct pain profiles in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. (2018) 13:801–11. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S150114

32. van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol. (2007) 18:1437–49. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm056

33. Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. Geneva: World Health Organization (2001).

34. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption - II. Addiction. (1993) 88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x

35. Ahorsu DK, Lin C-Y, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: development and initial validation. Int J Mental Health Addict. (2020) 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [Epub ahead of print].

36. Iversen MM, Norekvål TM, Oterhals K, Fadnes LT, Mæland S, Pakpour AH, et al. Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. Int J Mental Health Addict. (2021) 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00454-2. [Epub ahead of print].

37. Mahoney J, Drinka TJ, Abler R, Gunter-Hunt G, Matthews C, Gravenstein S, et al. Screening for depression: single question versus GDS. J Am Geriatr Soc. (1994) 42:1006–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06597.x

38. Littman AJ, White E, Satia JA, Bowen DJ, Kristal AR. Reliability and validity of 2 single-item measures of psychosocial stress. Epidemiology. (2006) 17:398–403. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000219721.89552.51

39. Nagy MS. Using a single-item approach to measure facet job satisfaction. J Occup Organ Psychol. (2002) 75:77–86. doi: 10.1348/096317902167658

40. Wanous JP, Reichers AE, Hudy MJ. Overall job satisfaction: how good are single-item measures? J Appl Psychol. (1997) 82:247–52. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.247

41. Askgaard G, Gronbaek M, Kjaer MS, Tjonneland A, Tolstrup JS. Alcohol drinking pattern and risk of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study. J Hepatol. (2015) 62:1061–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.005

42. Rehm J, Taylor B, Mohapatra S, Irving H, Baliunas D, Patra J, et al. Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2010) 29:437–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00153.x

43. Rothman KJ, Gallacher JEJ, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol. (2013) 42:1012–4. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys223

Keywords: alcohol, COVID-19, pandemic, population survey, substance use

Citation: Bonsaksen T, Ekeberg Ø, Schou-Bredal I, Skogstad L, Heir T and Grimholt TK (2021) Use of Alcohol and Addictive Drugs During the COVID-19 Outbreak in Norway: Associations With Mental Health and Pandemic-Related Problems. Front. Public Health 9:667729. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.667729

Received: 14 February 2021; Accepted: 29 March 2021;

Published: 14 June 2021.

Edited by:

Patrik Roser, Psychiatric Services Aargau, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Chung-Ying Lin, National Cheng Kung University, TaiwanCopyright © 2021 Bonsaksen, Ekeberg, Schou-Bredal, Skogstad, Heir and Grimholt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tore Bonsaksen, dG9yZS5ib25zYWtzZW5AaW5uLm5v

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.