- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

- 2Office of Healthcare Equity, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, United States

- 3University of California, Berkeley School of Law, Berkeley, CA, United States

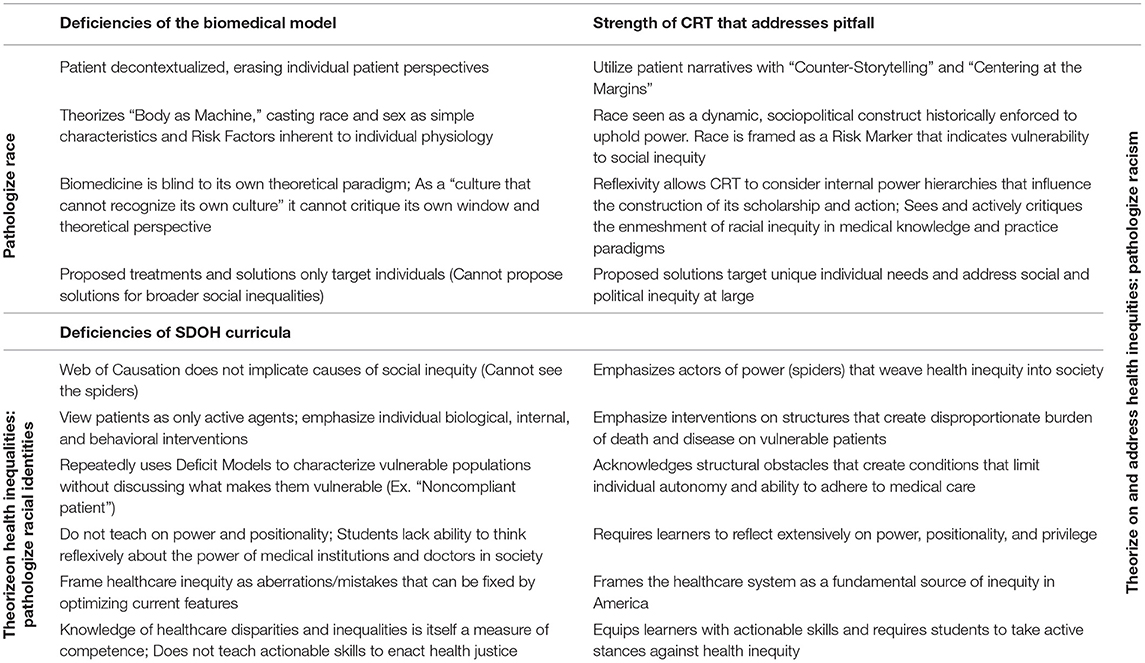

A professional and moral medical education should equip trainees with the knowledge and skills necessary to effectively advance health equity. In this Perspective, we argue that critical theoretical frameworks should be taught to physicians so they can interrogate structural sources of racial inequities and achieve this goal. We begin by elucidating the shortcomings in the pedagogic approaches contemporary Biomedical and Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) curricula use in their discussion of health disparities. In particular, current medical pedagogy lacks self-reflexivity; encodes social identities like race and gender as essential risk factors; neglects to examine root causes of health inequity; and fails to teach learners how to challenge injustice. In contrast, we argue that Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a theoretical framework uniquely adept at addressing these concerns. It offers needed interdisciplinary perspectives that teach learners how to abolish biological racism; leverage historical contexts of oppression to inform interventions; center the scholarship of the marginalized; and understand the institutional mechanisms and ubiquity of racism. In sum, CRT does what biomedical and SDOH curricula cannot: rigorously teach physician trainees how to combat health inequity. In this essay, we demonstrate how the theoretical paradigms operationalized in discussions of health injustice affect the ability of learners to confront health inequity. We expound on CRT tenets, discuss their application to medical pedagogy, and provide an in-depth case study to ground our major argument that theory matters. We introduce MedCRT: a CRT-based framework for medical education, and advocate for its implementation into physician training.

Introduction

As the healthcare system struggles to combat racial health injustices, it is important to interrogate how medical education may contribute by failing to address inequity on a pedagogical and rhetorical level (1, 2). Though a portion of US medical schools now include some health disparities teaching, few engage in critical examination of health inequity (3, 4). As defined by Kawachi, health inequality is the “generic term used to designate differences, variation, and disparities in the health achievements of individual groups,” whereas health inequity “refers to those inequalities in health that are deemed to be unfair or stemming from some form of injustice” (5).

This distinction between health inequalities (used here interchangeably with health disparities) and health inequities is important, and often missed. Many have expressed concern that current health disparities curricula—often referred to as “Social Determinants of Health” (SDOH) curricula—fail to engage with health inequity (6). These models merely name the existence of health differences and describe social determinants (such as access to food, educational attainment, income level) without relating them to power structures that marginalize different populations (6). This inability (or unwillingness) of SDOH to contextualize healthcare within relevant sociopolitical realities leaves trainees without Structural Competence—the proficiency to articulate or challenge root causes of unequal conditions (6–9). To ensure healthcare professionals are able to provide high-quality patient care and advance health justice, medical education needs a robust approach to health inequity that can scrutinize racial injustices pertaining to clinical practice, physician training, and scientific knowledge production (3, 10–12).

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is uniquely primed to help achieve this goal. CRT is an intellectual movement, body of scholarship, and analytical toolset historically developed to interrogate relationships between law and racial inequality (13). By training learners to identify and oppose fundamental sources of patient marginalization and engage in self-critique of health services research, CRT does what biomedical and health disparities curricula cannot: rigorously prepare physician trainees to combat health inequity. In this Perspective, we review current pitfalls of Biomedical and SDOH educational models, introduce MedCRT: A CRT-based framework for medical education, and advocate for its implementation in physician training.

Background

How physicians are trained undoubtedly impacts the professionals they become and the systems they influence. Currently, medical training is dominated by knowledge produced by Western biomedicine, a field with limited diversity and inclusion (14–17). As such, the discipline has limited ability to disrupt social hierarchies (18) that perpetuate inequities, and has inadvertently reified problematic paradigms, including biological notions of race (3, 4, 8, 19).

Students and educators empowered as critical learners and scientist-scholars can create a more ethical healthcare system (4, 20). But US medical education notably lacks space—in terms of faculty positions, classroom hours, assessment considerations—dedicated to training students how political economy shapes medical knowledge and systems today (3, 11, 21). This undermines social science perspectives, effaces the muscularity of social powers in dictating health outcomes, and narrows critical scholarly introspection (22, 23). Biomedicine extolls the importance of peer review for strong scholarship, but fails to bring interdisciplinary experts to its own table (7).

Calls for anti-racist education have been made nationally (24, 25). However, these efforts have been mostly student-led or elective, and lack established support (8). Effective and critically anti-racist health justice education is not yet institutionalized in US medical education (3).

What Is Your Theory? The Shortcomings of the Biomedical Model

The biomedical model (BM) characterizes bodies as machines, and disease as machine malfunction: pathology arises when biological components (hormones, tissues) are impaired (26–28). As Krieger states, this paradigm “divorce[s] external forces from the internal mechanisms: it focuses on the inner-workings of the machine…rather than interrogating factors that shape the contexts within which the machine acts (how was the machine built? Where does it thrive?)” (28). This focus on individual machinations relays that the source of disease—and disease disparities—is found within the body's borders, divorcing human health from socio-political realities (29). Because pathology is understood to arise from/in bodies, its presumed solutions do too. Proposed treatments engage only individual machines, and include pharmaceuticals, surgeries, and behavior changes (27, 29).

The BM is reductionist and essentialist. Because it reasons that risk factors are physiologic components of each patient's “machine” that confer higher probabilities of disease, ideas like race and sex are flattened as immutable characteristics that can be tabulated as machine parts. Rather than being appraised as complex political constructions rooted in cultural history, race becomes a series of genes; sex, a soup of hormones. This conceptualization deduces that health disparities arise from different and dysfunctional machine parts, which impedes nuanced comprehension of why people of different identities suffer unequal health outcomes (or what these identities even are). Learners of the BM discuss “poverty but not oppression, race but not racism, sex but not sexism, and homosexuality but not homophobia” (6).

Biomedicine has a set of assumptions and logic models—a theoretical paradigm—that guides how the discipline and its resulting scholarship conceive of concepts such as race, sex, disease disparities, and disability. This lens impacts the questions, methods, and conclusions produced. Yet, the field denies the existence of an overriding framework and presumes it is apolitical and value-neutral (3, 17, 30–33). It is a culture that cannot recognize its own culture (34). This hinders its ability to interrogate the window through which it observes and interprets the world (30).

All thinking and research is guided by theory, and critical formations within social science disciplines draw attention to this fact to interrogate the limits, format, and assembly of their “windows” and the views they provide (32, 35). This practice allows social scientists to analyze inequities that impact their approaches and explanations—their thinking (32). Lenses warp light. But biomedicine's insistence that it relies on pure empiricism—that it sees the world without an intervening theoretical frame—means it cannot evaluate the process, construction, and ensuing flaws of its understanding of bodies, disease, and racial difference (36–41). The field is left without the scholarly articulation and rhetorical defenses that help identify and combat racism embedded in hospitals and professional medical culture (32). This lack of reflexivity has ushered hidden curricula into the healthcare system (14–16). As result, medical trainees struggle to identify and disrupt injustice out in society and within their own professional homes. Given only the “Master's Tools” (42), they are left “on a road to nowhere” (6). Medical pedagogy needs critical perspectives that can help elucidate the social and scientific phenomena that allow injustice to perpetuate in its own house. It must learn to see the window, in order to critique and correct the lens through which contemporary biomedicine perceives racial inequities.

Social Determinants of Health Theory: Where Is the Spider?

While many institutions have sought to address limitations of the BM with SDOH teaching, these emerging curricula are still ill-equipped to challenge health inequity (6). In these instances, social determinants are often presented as well-worn considerations that are in some ways natural and immutable. A number of conditions—poverty, race, diet, sex—are labeled as “risk factors” entangled on a “web” of contributing elements that increase the likelihood of a given pathology (27, 43–46). Importantly, however, the spider that weaves the web is absent in this metaphor (43). The material and historical conditions that create unequal distributions of power and resources—the conditions that spin the web of inequity such as racial supremacy, wealth concentration, neoliberal capitalism, and misogyny—are not included, considered, learned, or taught (43). The lack of an agent implies that these important determinants of health appear at nobody's behest. Thus, SDOH models imply that the disproportionate suffering of vulnerable populations originates from expected or natural differences instead of inequities engineered through unjust provisions set in place by empowered systems.

By pivoting discussions away from actors (spiders) that create inequity, SDOH curricula deliberate only biological, internal, and behavioral “causes” of disproportionate disease. Marginalized identities are pathologized: students learn that “urban” patients face more chronic disease due to poor diets and poverty. Learners are not taught unequal contexts of urban engineering, police surveillance, neighborhood segregation, and food deserts that limit well-being (47–49). This failure to include critical explanations on why, how, and by whom groups of people are historically and actively oppressed means SDOH curricula continually frame marginalized populations as deficient—not only financially, but also with regards to literacy, acumen, and ability (36, 37). Wealth and privilege are also social determinants of health—as are whiteness, citizenship, and proximity to political power. Yet, SDOH curricula bypass these considerations (and neglect to discuss who benefits from health inequity) to continually fixate on perceived deficiencies of “at-risk” populations. The repetition of the deficit-model constantly stigmatizes patients of color as poor, illiterate, needy, and unknowledgeable, while also implicitly supporting their surveillance, which can worsen existing health inequities (3, 4, 8, 19, 36, 37).

Without spiders, the visible agents in the web are patients, which locates them as the only active—and therefore, the only culpable—individuals in the disease pathway. Health disparities are thus framed as the outcome of poor individual choices or faulty genetics (4, 29, 38). This emphasizes targeted behavioral and biomedical interventions rather than considering structural solutions to structural obstacles. Consider, for example, how terms such as “non-compliant” (39, 40) ignore institutional inequities in insurance, transportation, and access that limit ability to adhere to prescribed treatments. This underscoring of individual culpability implicitly casts social justice efforts as philanthropic enterprises (needed to help people make better decisions or overcome genetic predisposition) rather than justified, reparative endeavors necessary to rectify historical wrongs (4). Like the BM, SDOH curricula lack theorization that explicitly associates socio-political economy with health inequity. Instead, students are taught to label populations as “vulnerable” without understanding what makes them vulnerable.

Lastly, because SDOH pedagogy does not incorporate teaching on actionable skills or solutions, students learn about health disparities but are not taught how to achieve justice (6). For example, implicit bias is framed as a cause of health disparities (13), but students are not asked to consider the origins of anti-black/pro-white biases, nor how to combat them. Prejudices are framed as subtle, innocuous preferences that are “unconscious,” which removes the purveyor's culpability and casts biases as normative and uncontrollable (41). Instead of an intervention, implicit bias tests—which associate racial discrimination with aversion to poisonous snakes—become “an alibi” that functions to permit further prejudice (50).

Racism is a leading cause of implicit bias: so how can students attack unconscious prejudice if they are not taught what racial hierarchy is or how it functions structurally? Without understanding how power operates in society, students cannot conceptualize how institutional and interpersonal prejudices disadvantage marginalized people regardless of conscious intent. White students, for example, will have difficulty comprehending racial inequity if they are unable to articulate or acknowledge their own privilege. This is also where traditional cultural competency models fail (51–54). Not only do they attempt to compartmentalize the needs of patient populations—often through troubling racial stereotypes—they “serve to further Other communities, because it (teaches) students to see difference without dissecting their own power” (17, 55). Learners receive information about human difference without being taught to challenge unjust distributions of power, which relegates SDOH pedagogy to a formality where competencies can be obtained without meaningful movement toward equity. Though medical schools may respond to the call for social justice with SDOH, lack of critical analyses on race and health renders these attempts ineffective (6).

Critical Race Theory

We have described the ways US medical education fails to address health inequities. In their reticence or inability to engage in theoretical analysis of sociopolitical power, BM and SDOH curricula decontextualize human experience and erase patient perspectives (56, 57). Students are taught to fixate on individual choices and innate flaws—locating “responsibility” for poor health outcomes within those who inhabit them. Importantly, this may fail to engender empathy (or even discourage empathy) toward those facing structural violence (38). Lack of critical perspective also prevents “disciplinary self-critique” and fails to teach trainees how to act meaningfully against injustice (6, 12).

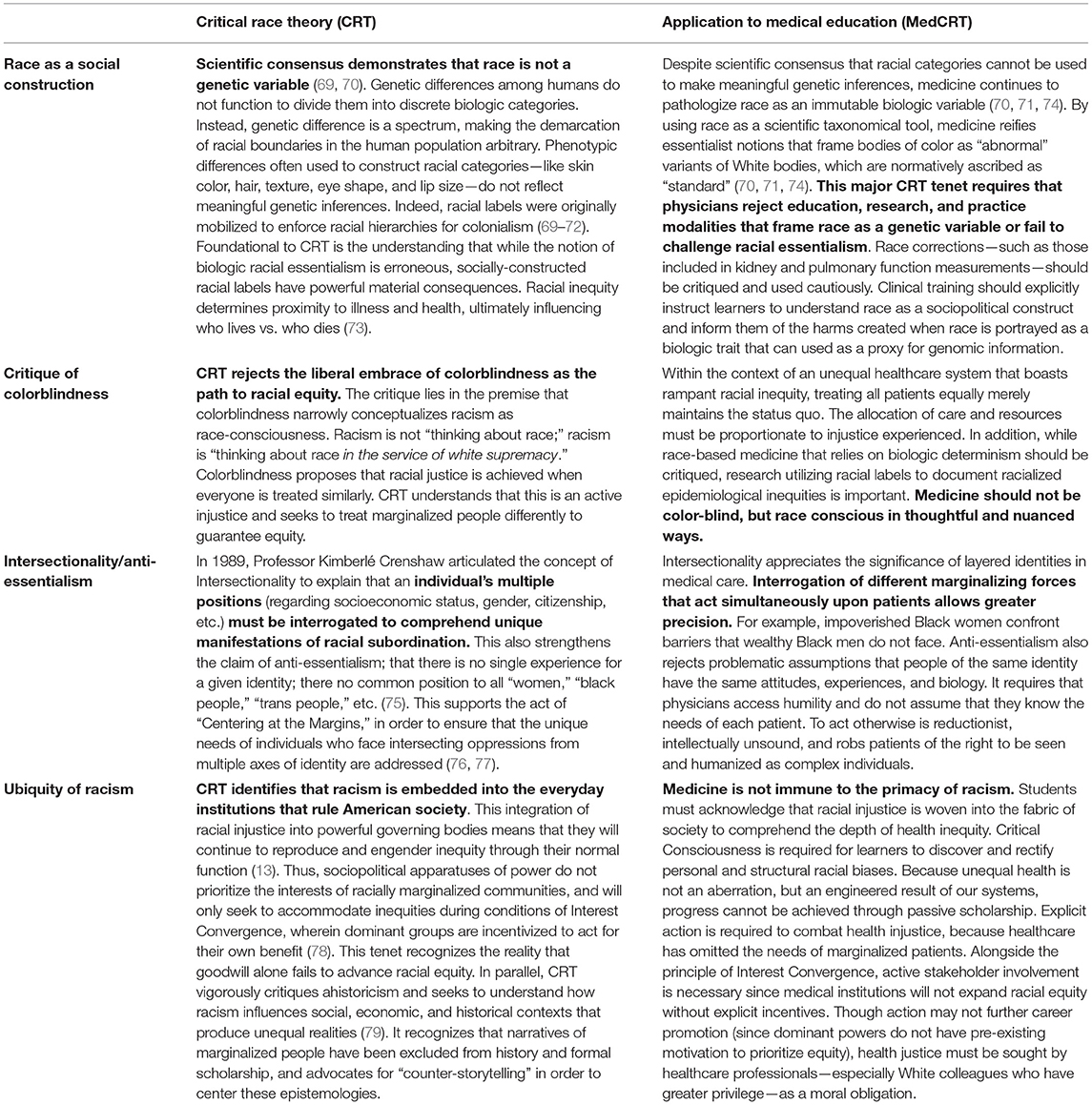

Current pedagogy on culture, bias, and diversity have been insufficient in engendering equity (54). New methods of building critical consciousness are necessary to bridge comprehension of inequities to care and praxis against them (58). A form of critical teaching and scholarship, Critical Race Theory (CRT) is able to address the deficiencies of current medical pedagogy by embracing tenets that help students achieve critical consciousness (59) of structural inequity (see Table 1).

Unlike the BM—which inaccurately presumes race is an essential component of the human machine—CRT asserts that race is not genetic but a power construct engineered to enforce racial hierarchy. In addition, CRT stresses that racism is so prevalent in society that it has become normalized to the point of invisibility (60–62). This recognition comes with comprehension that racism has shaped governing systems of the United States and is embedded into every institution of power (63). Thus, normal institutional operations—including that of medicine, healthcare, and scientific research—produce and perpetuate racial hierarchies and injustices by design (62). CRT demonstrates that racial categorization incites racism, which directs power and privilege toward some and away from others, justifies unfair outcomes, and reconciles how professed commitments to equality co-exist with the undeniable fact of injustice (13). This acknowledgment helps visualize the sociopolitical powers that influence medicine, and in juxtaposition to existing biomedical and SDOH models, grants learners and educators skills of self-critique required to “see the window” and dissect the racial inequities embedded in their own organizations (64). At its core, CRT seeks to identify and rectify systemic practices that generate racial injustice (63, 65). Importantly, CRT is not only interested in scholarship for scholarship's sake; It is committed to action that advances social equity (66, 67).

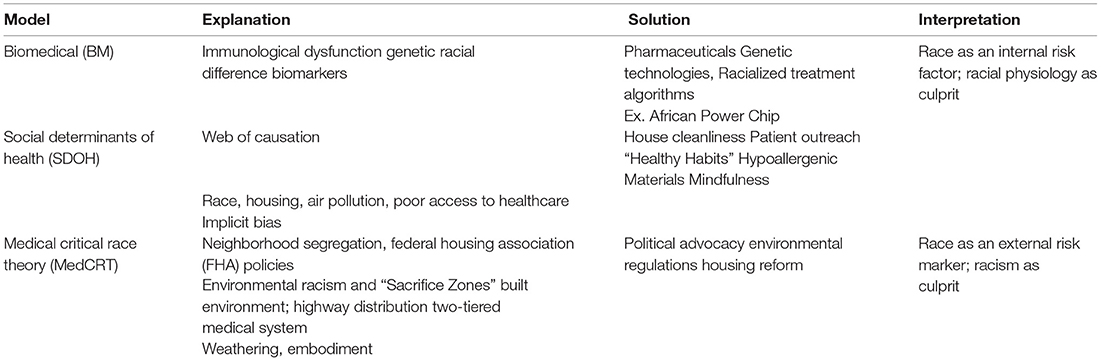

A medical CRT (MedCRT) framework requires scholars and learners to: “(1) Analyze race and racism as fundamental social structures within science, medicine, and society, (2) Challenge scientific theories of race that obscure the institutional mechanisms that generate racial health inequity, and (3) Produce analyses that mobilize and support antiracist praxis” (68) (see Table 2). MedCRT's iterative methodology continually questions complex power dynamics and “place[s] medicine in a social, cultural, and historical context” to develop nuanced comprehension of race, injustice, and health (51). While biomedical and SDOH models characterize race as an intrinsic individual risk factor, CRT asserts that racial identity should instead be understood as a risk marker that inscribes vulnerability to structural racial inequities in education, environmental safety, criminal justice, housing segregation, and social investment (45, 46). This transforms the question of differing racial epidemiology from “How do, and which intrinsic biological racial differences cause health disparities?” to “How do, and which racial injustices cause health inequities?” This allows robust avenues for learners to identify and intervene where health injustices originate. Further, in interrogating how and why atavistic beliefs of racial biology persist, (What is considered legitimate scientific knowledge? Who has the authority to create it? What agendas are implicitly supported by theories of intrinsic racial biology?) CRT not only allows for examination of biomedicine's theoretical window—it also abets understanding of how injustice has warped the lens (3).

Table 2. Critical race theory adapted to medical education (MedCRT) (13).

This sharpening of self-critique is not only important for the training of scientists and scholars who must examine the questions, methodologies, and interpretations of health inequality research to create new and better knowledge (12). It also aids in the Structural Competence and compassionate caregiving of clinicians. Both academic and clinical medicine are strengthened by the ability to understand one's position of power, as “critical consciousness” is theorized to be an important component of a trainee's ability to address health inequities (6, 80).

While traditional medical education may erase reflexivity by endorsing “the belief that (a healthcare provider's) class, race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation are irrelevant to their medical practice” (17), CRT emphatically names its importance to ensure learners contextualize their care and improve on their ability to humanize patients (14, 81). For example, providers seeking to understand racial HIV inequities noted a “CRT lens proved especially useful in articulating the deep, complex, and systemic structural underpinnings of psychosocial barriers” in their patients, which allowed them to offer better, more compassionate medical care (82). This may ultimately improve patient outcomes, which represents an important opportunity for future research.

The guiding theory of illness (what causes and distributes disease) dictates the measures, methodologies, and justifications trainees and educators have to not only research and explain phenomena, but to articulate causative factors and thus imagine solutions (26–28, 38). Thus, theory matters. The window matters (see Box 1 for a case study). Overall, because CRT develops in learners a better understanding of structures of oppression, self-critique that can cultivate greater consciousness for change (105), and action-oriented praxis, it is a pedagogical intervention uniquely equipped to bolster health justice training and advancement (82). As a critical framework that offers necessary perspectives on race, racism, and health inequity for physicians, we propose that MedCRT should be employed to reform medical education.

Box 1. Theory matters: racial asthma inequities as a case study.

The guiding theory of illness dictates how students understand, explain, and challenge health inequities. Thus, theory matters. To reiterate our arguments in this paper and illustrate the importance of CRT-based medical curricula, we utilize the case example of childhood asthma, for which there are known contemporary health inequities. We show how Biomedical, SDOH, and CRT models of medical education identify different causal justifications for this racial difference in disease morbidity and mortality, and how these operationalized theories impact the corollary solutions each pedagogic framework proposes to address the problem. Concepts are summarized below.

For Black children, the mortality rate for asthma hangs six times higher than it does for their white counterparts (83). As discussed, the biomedical model portrays race as an essential genetic characteristic, and intuits that black race is an internal risk factor that predisposes black youth to this disease. As such, purveyors of biomedical theory may teach medical students about differential racial genetics that act as biologic predictors to asthma (84). Research on genetic mutations—such as those impacting SPINK5, DPP-1, and GRPA genes—are offered as the root of health disparities (85, 86). Genes that cause racialized responses to treatment options are also touted as rationale (87). The underlying notion is that if physician-scientists are able to locate genetic racial differences, targeting them through pharmacology and gene therapies will serve as a potent method to minimize racial disparities. This theory is pervasive and financially well-supported. The 2013 NIH Biennial Report (88) details million-dollar investment in the development of the “African Power Chip—” a genome-sequencing endeavor meant to “discover genes associated with asthma in African ancestry populations.”

SDOH curricula may go a step further in their discussion of asthma health inequalities by outlining a web of causation that connects risk factors like race, gender, and housing to unequal disease outcomes. It may teach students, for example, that people of color have higher exposure to mold, low-quality housing, or cockroaches that increase likelihood of asthma (89, 90). Data demonstrating that people of color have higher rates of smoking (89) may also be posited as a cause of disproportionate illness. Solutions, therefore, focus on behavioral changes like smoking cessation measures, patient outreach on hygiene education, or instruction to purchase hypoallergenic materials to minimize exposure to triggers. This ignores data that demonstrates how communities of color are targeted with significantly higher rates of tobacco advertisements as a predatory business strategy (91). SDOH shows students the web of health inequality, but not the spider that weaves racial inequity.

In fact, systemic racism manifests in myriad ways to cause racial health inequities in asthma. CRT helps us see how. This in turn helps inform solutions that are fundamental to promoting health justice. First, CRT asserts that race is a sociopolitical construct, which weakens the biomedical theory that differences in asthma prevalence can be explained by genetic racial differences in cell signaling and lung physiology. This also undermines the idea that genomic pursuits like the African Power Chip represent sustainable remedies to health inequities. CRT's position on the ubiquity of racism, the rejection of colorblindness, and the importance of intersectionality also combine to provide important insights that inform the causation of and interventions for asthma health inequities.

Given CRT's origins in law, it is appropriate to begin with the historical enmeshment of racial inequity in the criminal justice system. Today, the United States imprisons a larger percentage of its Black population that South Africa did during apartheid (92). Despite similar rates of drug use, Black men are 12 times more likely to be arrested for drug offenses than white counterparts (93). Being locked up is bad for your lungs. People with a history of incarceration are twice as likely to have asthma than the non-incarcerated American population (94).

America's lack of a socialized healthcare system ties medical access to financial security. While the black- white income gap itself is large, it is perhaps more important to consider the generational wealth gap, which is startling at 91,000 dollars for whites, 6,500 dollars for blacks. This is a 14-fold difference, and this gap is widening (95). Given economic analysis demonstrating that 50% of the median homeowner's wealth comes from the value of their property, it is important to understand how Black American families were historically denied home ownership. In the 1930's, the Federal Housing Association financed 60% of all American homes, yet <2% of these loans were awarded to people of color (96). Black neighborhoods were routinely “red-lined” and coded for mortgage default, stranding them in poorly-resourced and underdeveloped geographic locations (97). This discrimination is foundational to government-sponsored racial segregation, which, even when controlled for income, is tied to not only asthma, but heart disease, cancer, and lower life expectancy overall (98). In the South Bronx, a child is 14.2 times as likely to be hospitalized for asthma-related complications than a child in wealthier neighborhood <2 miles away (99). Importantly, the racial housing inequity is tied not only to issues of socioeconomic status, but environmental exposure.

Urban planning in America has time and again chosen to destroy places where people of color live, breathe, play, and pray. Throughout American history, black neighborhoods have been decimated to make way for highway construction, or else chosen as sites near which toxic waste landfills are placed (98, 100). Indeed, Black and Hispanic populations have higher exposure to 13 out of 14 main environmental pollutants (101) and are twice as likely to live near sources of industrial pollution in residential areas known as “sacrifice zones” (102).

CRT shows how the pervasiveness of racial injustice in American incarceration, urban planning, resource allocation, and environmental damage represent disproportionate, constant, and serious insults that are definitively linked to higher rates of lung disease in people of color. Its relevant intersections with poverty, imprisonment, and gender give methods to theorize thoughtfully on how to attend to specific populations jeopardized by multiple identities. Lastly, alongside epidemiologic scholarship on Weathering and Embodiment (103, 104)—concepts that tie how racial discrimination and social inequality translate to biologic dysfunction—the importance of rejecting to colorblindness as a path to equity is highlighted. It is necessary to pay attention to race insofar as it lets us see how racism is a major driver of health inequity. We need a critical theory of race—CRT—to locate the spider.

Discussion

Critical Race Theory (CRT) emerged in the 1970s to challenge the shortcomings of the law by mobilizing an unrealized imagination: “What would the legal landscape look like today if non-white people were at the table when our society and its institutions were being organized?” We are inspired. What would medicine—its training, practice, and presumption—look like if it were informed by the scholarship and experiences of a vast diversity of people: people who are racially-marginalized, sociologists, community organizers, queer, differently-abled?

Though medical education has made strides to address health disparities, these efforts are falling short. The burdens of racism are indisputable. Physicians are taught to train their eyes on the numbers, but without critical frameworks, they will continue to perseverate on health inequality ineffectively. They will know about health disparities, but be unable to articulate health inequities well enough to challenge them (6).

Health equity cannot be achieved through technologic advancement or market-based ingenuity. It is, fundamentally, not a problem of science, but an issue of ethics and justice. Indeed, while 30,000 deaths could be prevented through medical innovation annually, eliminating excess mortality associated with education inequities would save 200,000 lives yearly (106). Remaining idle and ignorant renders our institutions complicit in an unjust system that makes our patients sicker. Medical trainees should receive robust, critical education that allows them to confront the forces that bolster health inequity. This requires the analytical and action-oriented pedagogical framework of Critical Race Theory.

Since its origins in jurisprudence, CRT has expanded into realms of education and public health (64, 66, 107–110). That CRT has been effectively incorporated into other domains to better address educational, health, and legal inequities demonstrates that incorporating CRT into medical pedagogy is necessary. Indeed, that CRT remains absent from physician education suggests that efforts to address racial inequity in medicine are lagging. It further underlines that MedCRT perspectives must be integrated in senior, administrative, and faculty-level continuing medical education—not just that of early trainees.

Medical education is a powerful site of action: Institutional commitment to equity can begin with improving how we teach and produce knowledge about inequity itself. The principles of Critical Race Theory are especially equipped to train learners to see spiders that weave political economy and power together to create injustice. We urge medical institutions and educators to mobilize greater engagement with Critical Race Theory and take a decisive step toward a more equitable future for students and patients alike.

Author Contributions

JT was responsible for conceptualization, research, original writing, and revisions. EL and KB was responsible for research, original writing, and revisions. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 28:1504–10. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1

2. Hostetter M, Klein S. In Focus: Reducing Racial Disparities in Health Care by Confronting Racism. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund (2018).

3. Braun L. Theorizing race and racism: preliminary reflections on the medical curriculum. Am J Law Med. (2017) 43:239–56. doi: 10.1177/0098858817723662

4. Braun L, Saunders B. Avoiding racial essentialism in medical science curricula. AMA J Ethics. (2017) 19:518–27. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.6.peer1-1706

5. Kawachi I, Subramanian S, Almeida-Filho N. A glossary for health inequalities. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2002) 56:647–52. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.9.647

6. Sharma M, Pinto AD, Kumagai AK. Teaching the social determinants of health: a path to equity or a road to nowhere? Acad Med. (2018) 93:25–30. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001689

7. Jones DS, Greene JA, Duffin J, Harley Warner J. Making the case for history in medical education. J Hist Med Allied Sci. (2015) 70:623–52. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/jru026

8. Tsai J, Ucik L, Baldwin N, Hasslinger C, George P. Race matters? Examining and rethinking race portrayal in preclinical medical education. Acad Med. (2016) 91:916–20. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001232

9. Ahmad NJ, Shi M. The need for anti-racism training in medical school curricula. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. (2017) 92:1073. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001806

10. Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. (2014) 103:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032

11. Westerhaus M, Finnegan A, Haidar M, Kleinman A, Mukherjee J, Farmer P. The necessity of social medicine in medical education. Acad Med. (2015) 90:565–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000571

12. Hardeman RR, Karbeah JM. Examining racism in health services research: a disciplinary self-critique. Health Serv Res. (2020) 55:777–80. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13558

13. Bridges KM. Critical Race Theory: A Primer. 1st ed. St. Paul, MN: West Academic: Foundation Press (2019).

14. DasGupta S, Fornari A, Geer K, Kumar V, Lee HJ, Rubin S, et al. Medical education for social justice: Paulo Freire revisited. J Med Hum. (2006) 27:245–51. doi: 10.1007/s10912-006-9021-x

15. Haegele JA, Hodge S. Disability discourse: overview and critiques of the medical and social models. Quest. (2016) 68:193–206. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2016.1143849

16. Hafferty FW, Castellani B. 2 The hidden curriculum. In: Handbook of the Sociology of Medical Education. New York, NY: Routledge (2009). p. 15.

17. Sharma M. Applying feminist theory to medical education. Lancet. (2019) 393:570–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32595-9

18. Bailey M. The flexner report: standardizing medical students through region-, gender-, and race-based hierarchies. Am J Law Med. (2017) 43:209–23. doi: 10.1177/0098858817723660

19. Ripp K, Braun L. Race/ethnicity in medical education: an analysis of a question bank for step 1 of the United States Medical Licensing Examination. Teach Learn Med. (2017) 29:115–22. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2016.1268056

21. Anderson W. Teaching ‘race’ at medical school: social scientists on the margin. Soc Stud Sci. (2008) 38:785–800. doi: 10.1177/0306312708090798

22. Cooke M, Irby DM, Sullivan W, Ludmerer KM. American medical education 100 years after the Flexner report. N Engl J Med. (2006) 355:1339–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055445

23. Chowkwanyun M. The strange disappearance of history from racial health disparities research. Du Bois review. Soc Sci Res Race. (2011) 8:253–70. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000142

24. Tsai J, Crawford-Roberts A. A call for critical race theory in medical education. Acad Med. (2017) 92:1072–3. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001810

25. Wear D, Zarconi J, Aultman JM, Chyatte MR, Kumagai AK. Remembering Freddie gray: medical education for social justice. Acad Med. (2017) 92:312–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001355

26. Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol. (2001) 30:668–77. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.668

27. Krieger N. Got theory? On the 21 st c. CE rise of explicit use of epidemiologic theories of disease distribution: a review and ecosocial analysis. Curr Epidemiol Rep. (2014) 1:45–56. doi: 10.1007/s40471-013-0001-1

28. Krieger N. Epidemiology and the People's Health: Theory and Context. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2011).

29. Porter D. How did social medicine evolve, and where is it heading? PLoS Med. (2006) 3:e399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030399

30. Wilson HJ. The myth of objectivity: is medicine moving towards a social constructivist medical paradigm? Fam Pract. (2000) 17:203–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.2.203

31. Ziman J. Getting scientists to think about what they are doing. Sci Eng Ethics. (2001) 7:165–76. doi: 10.1007/s11948-001-0038-2

33. Rees CE, Monrouxe LV. Theory in medical education research: how do we get there? Med Educ. (2010) 44:334–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03615.x

34. Taylor JS. Confronting “culture” in medicine's “culture of no culture”. Acad Med. (2003) 78:555–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00003

35. Paradis E, Nimmon L, Wondimagegn D, Whitehead CR. Critical theory: broadening our thinking to explore the structural factors at play in health professions education. Acad Med. (2020) 95:842–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003108

36. Simis MJ, Madden H, Cacciatore MA, Yeo SK. The lure of rationality: why does the deficit model persist in science communication? Public Underst Sci. (2016) 25:400–14. doi: 10.1177/0963662516629749

37. Solorzano DG, Yosso TJ. From racial stereotyping and deficit discourse toward a critical race theory in teacher education. Multicult Educ. (2001) 9:2–8.

38. Stone DA. Causal stories and the formation of policy agendas. Polit Sci Q. (1989) 104:281–300. doi: 10.2307/2151585

39. Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. (Author Abstract). Am J Public Health. (2004) 94:2084. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.12.2084

40. Tsai J, Brooks K, DeAndrade S, Ucik L, Bartlett S, Osobamiro O, et al. Addressing racial bias in wards. Adv Med Educ Pract. (2018) 9:691. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S159076

41. Bonilla-Silva E. Rethinking racism: toward a structural interpretation. Am Sociol Rev. (1997) 62:465–80. doi: 10.2307/2657316

42. Lorde A. The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house. Sister Outsider Essays Speeches. (1984) 1:10–4.

43. Krieger N. Epidemiology and the web of causation: has anyone seen the spider? Soc Sci Med. (1994) 39:887–903. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90202-X

44. Krieger N. Sticky webs, hungry spiders, buzzing flies, and fractal metaphors: on the misleading juxtaposition of “risk factor” versus “social” epidemiology. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (1999) 53:678. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.11.678

45. Blackmore C, Ferre C, Rowley D, Hogue C, Gaiter J, Atrash H. Is race a risk factor or a risk marker for preterm delivery? Ethn Dis. (1993) 3:372–7.

46. Shim JK. Heart-Sick: The Politics of Risk, Inequality, and Heart Disease. New York, NY: NYU Press (2014).

47. Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. (2001) 116:404. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50068-7

48. Cummins S, Macintyre S. Food environments and obesity-neighbourhood or nation? Int J Epidemiol. (2006) 35:100–4. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi276

49. Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Affairs. (2005) 24:325–34. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.325

50. UNESCO. Sociological theories: race and colonialism. In: Chapter 12: Hall S. Race, Articulation, and Societies Structured in Dominance. Paris (1981).

51. Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med. (2009) 84:782–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398

52. Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (1998) 9:117–25. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

53. Baker K, Beagan B. Making assumptions, making space: an anthropological critique of cultural competency and its relevance to queer patients. Med Anthropol Q. (2014) 28:578–98. doi: 10.1111/maq.12129

56. Kumagai AK. A conceptual framework for the use of illness narratives in medical education. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. (2008) 83:653. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181782e17

57. Haque OS, Waytz A. Dehumanization in medicine: causes, solutions, and functions. Perspect Psychol Sci. (2012) 7:176–86. doi: 10.1177/1745691611429706

58. Saetermoe CL, Chavira G, Khachikian CS, Boyns D, Cabello B. Critical race theory as a bridge in science training: The California State University, Northridge BUILD PODER program. In: Paper presented at: BMC Proceedings (2017).

59. Zaidi Z, Vyas R, Verstegen D, Morahan P, Dornan T. Medical education to enhance critical consciousness: facilitators' experiences. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. (2017) 92:S93. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001907

60. Hatch AR. Critical race theory. In: The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing (2007).

62. Gotanda N, Peller G. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement. New York, NY: The New Press (1995).

63. Brayboy BMJ. Toward a tribal critical race theory in education. Urban Rev. (2005) 37:425–46. doi: 10.1007/s11256-005-0018-y

64. Ford CL. Public health critical race praxis: an introduction, an intervention, and three points for consideration. Wis L Rev. (2016) 3:477.

65. Bernal DD. Critical race theory, Latino critical theory, and critical raced-gendered epistemologies: recognizing students of color as holders and creators of knowledge. Qual Inq. (2002) 8:105–26. doi: 10.1177/107780040200800107

66. Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health. (2010) 100:S30–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171058

68. Hatch AR. Transformations of race in bioscience: critical race theory, scientific racism, and the logic of colorblindness. Issues Race Soc Interdiscip J. (2014) 2:17–41.

69. Yudell M, Roberts D, Desalle R, Tishkoff S. Taking race out of human genetics. Science. (2016) 351:564–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4951

70. Crowe T. How science has been abused through the ages to promote racism. In: The Conversation (2015). Available online at: https://theconversation.com/how-science-has-been-abused-through-the-ages-to-promote-racism-50629

72. Agassiz L. [Letter written August 10, 1863 to S. G. Howe]. In: Louis Agassiz Correspondence and Other Papers. MS Am 1419. (1863). Available online at: https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FHCL.HOUGH:2643633?n=622

73. Gloria L-B. Critical race theory-what it is not! In: Lynn M, Dixson AD, editors. Handbook of Critical Race Theory in Education. London: Routledge (2013).

74. Roberts DE. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-create Race in the Twenty-First Century. New York, NY: New Press (2011).

75. Harris AP. Race and essentialism in feminist legal theory. Stanford Law Rev. (1990) 42:581–616. doi: 10.2307/1228886

76. Lindo E, Williams B, González MT. Uncompromising hunger for justice: resistance, sacrifice, and latcrit theory. Seattle J Soc Justice. (2019) 16:727–813. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3334113

77. Solorzano DG, Yosso TJ. Critical race and LatCrit theory and method: counter-storytelling. Int J Qual Stud Educ. (2001) 14:471–95. doi: 10.1080/09518390110063365

78. Eberly LA, Richterman A, Beckett AG, Wispelwey B, Marsh RH, Cleveland Manchanda EC, et al. Identification of racial inequities in access to specialized inpatient heart failure care at an academic medical center. Circ Heart Fail. (2019) 12:e006214. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006214

79. Delgado R. Storytelling for oppositionists and others: a plea for narrative. Mich Law Rev. (1989) 87:2411–41. doi: 10.2307/1289308

81. Tsevat RK, Sinha AA, Gutierrez KJ, DasGupta S. Bringing home the health humanities: narrative humility, structural competency, and engaged pedagogy. Acad Med. (2015) 90:1462–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000743

82. Freeman R, Gwadz MV, Silverman E, Kutnick A, Leonard NR, Ritchie AS, et al. Critical race theory as a tool for understanding poor engagement along the HIV care continuum among African American/Black and Hispanic persons living with HIV in the United States: a qualitative exploration. Int J Equity Health. (2017) 16:54. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0549-3

83. Gupta RS, Carrión-Carire V, Weiss KB. The widening black/white gap in asthma hospitalizations and mortality. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2006) 117:351–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.047

84. Barnes KC, Grant AV, Hansel NN, Gao P, Dunston GM. African Americans with asthma: genetic insights. Proc Am Thor Soc. (2007) 4:58–68. doi: 10.1513/pats.200607-146JG

85. Gamble C, Talbott E, Youk A, Holguin F, Pitt B, Silveira L, et al. Racial differences in biologic predictors of severe asthma: data from the severe asthma research program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2010) 126:1149–56.e1141. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.049

86. Scirica C, Celedon J. Genetics of asthma—potential implications for reducing asthma disparities. Chest. (2007) 132:770S–81S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1905

87. Choudhry S, Ung N, Avila P, Ziv E. Pharmacogenetic differences in response to Albuterol between Puerto Ricans and Mexicans with asthma. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. (2005) 171:563–70. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1286OC

88. Report of the Director: National Institutes of Health Fiscarl Years 2012 & 2013. National Institutes of Health (2013).

89. Hughes HK, Matsui EC, Tschudy MM, Pollack CE, Keet CA. Pediatric asthma health disparities: race, hardship, housing, and asthma in a national survey. Acad Pediatr. (2017) 17:127–34. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.011

90. Weitzman M, Gortmaker S, Sobol A. Racial, social, and environmental risks for childhood asthma. Am J Dis Child. (1990) 144:1189–94. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150350021016

92. Alexander M. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Revised edition/with a new foreword by Cornel West. ed. New York, NY: New Press (2011).

93. Klimo P Jr., Lingo PR, Baird LC, Bauer DF, Beier A, Durham S, et al. Congress of neurological surgeons systematic review and evidence-based guideline on the management of patients with positional plagiocephaly: the role of repositioning. Neurosurgery. (2016) 79:E627–9. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001428

94. Lehrnbecher T, Robinson P, Fisher B, Alexander S, Ammann RA, Beauchemin M, et al. Guideline for the management of fever and neutropenia in children with cancer and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation recipients: 2017 update. J Clin Oncol. (2017) 35:2082–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.7017

95. Terry S CC, Hoxie J. Dreams Deferred: How Enriching the 1% Widens the Racial Wealth Divide, Jamaica Plain, MA. Inequality.Org (2019).

97. Tobin G. Divided Neighborhoods: Changing Patterns of Racial Segregation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publication (1987).

98. Bullard R. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. San Francisco, CA: WESTVIEW PRESS Boulder (1990).

99. Adams L, Afshar N, Agerton T, Ajaiyeoba T, Anekwe A, Angell S. Community Health Profiles 2018: Mott Haven and Melrose. New York, NY: Department of Helath and Mental Hygiene (2018). Available online at: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2018chp-bx1.pdf

100. Karas D. Highway to inequity: the disparate impact of the interstate highway system on poor and minority communities in American cities. New Vis Public Affairs. (2015) 7:9–21.

101. Bell ML, Ebisu K. Environmental inequality in exposures to airborne particulate matter components in the United States. (Research) (Report). Environ Health Pers. (2012) 120:1699. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205201

102. Bullard RD. Unequal Protection: Environmental Justice and Communities of Color. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books (1994).

103. Krieger N. Embodiment: a conceptual glossary for epidemiology. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2005) 59:350. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.024562

104. Gravlee CC. How race becomes biology: embodiment of social inequality. Am J Phys Anthropol. (2009) 139:47–57. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20983

105. Amiot NM, Mayer-Glenn J, Parker L. Applied critical race theory: educational leadership actions for student equity. Race Ethn Educ. (2020) 23:200–20. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2019.1599342

106. Woolf SH, Johnson RE, Phillips RL Jr., Philipsen M. Giving everyone the health of the educated: an examination of whether social change would save more lives than medical advances. Am J Public Health. (2007) 97:679–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084848

107. Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Commentary: just what is critical race theory and what's it doing in a progressive field like public health? Ethn Dis. (2018) 28(Supp. 1):223–30. doi: 10.18865/ed.28.S1.223

108. Graham L, Brown-Jeffy S, Aronson R, Stephens C. Critical race theory as theoretical framework and analysis tool for population health research. Crit Public Health. (2011) 21:81–93. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2010.493173

109. Hiraldo P. The role of critical race theory in higher education. Vermont Connect. (2010) 31:7. Available online at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/tvc/vol31/iss1/7

Keywords: critical race theory, health inequity and disparity, medical education, social determinants of health, biomedical model, health pedagogy, racial justice, medical critical race theory

Citation: Tsai J, Lindo E and Bridges K (2021) Seeing the Window, Finding the Spider: Applying Critical Race Theory to Medical Education to Make Up Where Biomedical Models and Social Determinants of Health Curricula Fall Short. Front. Public Health 9:653643. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.653643

Received: 14 January 2021; Accepted: 23 April 2021;

Published: 09 July 2021.

Edited by:

Georges C. Benjamin, American Public Health Association, United StatesReviewed by:

Charles F. Harrington, University of South Carolina Upstate, United StatesStacie Craft DeFreitas, University of Houston–Downtown, United States

Copyright © 2021 Tsai, Lindo and Bridges. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer Tsai, amVubmlmZXIudy50c2FpQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Jennifer Tsai

Jennifer Tsai Edwin Lindo

Edwin Lindo Khiara Bridges

Khiara Bridges