95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Public Health , 04 June 2021

Sec. Planetary Health

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.644748

This article is part of the Research Topic Challenges and Successes of One Health in the Context of Planetary Health in Latin America and the Caribbean View all 20 articles

Working the One health strategy in developing countries is a challenge, due to structural weaknesses or deprivation of financial, human, and material resources. Brazil has policies and programs that would allow continuous and systematic monitoring of human, animal, and environmental health, recommending strategies for control and prevention. For animals, there are components of the Epidemiological Surveillance of zoonosis and Animal Health Programs. To guarantee food safety, there are Health Surveillance services and support of the Agropecuary Defense in the inspection of these products, productive environments, and their inputs. Environmental Surveillance Services monitor water and air quality, which may influence health. For human health, these and other services related to Health Surveillance, such as Worker Health and Epidemiological Surveillance, which has a training program responsible for forming professionals groups to respond effectively to emergencies in public health are available. Therefore, Brazil has instruments that may allow integrated planning and intervention based on the One Health initiative. However, the consolidation of this faces several challenges, such as insufficient resources, professional alienation, and lack of the recognition of the importance of animal and environmental health for the maintenance of human and planetary well-being. This culminates in disarticulation, lack of communication, and integration between organizations. Thus, efforts to share attributions and responsibilities must be consolidated, overcoming the verticality of the actions, promoting efficiency and effectiveness. Finally, this perspective aims to describe the government instruments that constitute potential national efforts and the challenges for the consolidation of the One Health initiative in Brazil.

One Health is an integrative and cooperative health initiative, with a transdisciplinary approach to health promotion and surveillance at the local, regional, national or global level, aiming to achieve optimal health conditions, given the recognition of the interconnection and interdependence between human, animals, and the environment (1, 2).

Historically, the perspective that environmental health affects humans has existed since the classical era. Hippocrates stated that biological and environmental conditions affect human health (3). Afterward, Aristotle and Galen sought to elucidate similarities between human and animal vital systems, allowing the creation of Comparative Medicine (4, 5).

In the 19th century, pathologist Robert Virchow coined the term “zoonosis,” to name diseases transmitted from animals to humans, based on his observations with helminths, believing that there is no separation between animal and human health (5, 6).

Despite the recognition of this relationship, it was only 1970s that the epidemiologist Calvin Schwabe introduced the “One Medicine” theory, to name, in a holistic way, the connection between animals and humans in nutrition, habitat, and health, stating that both human and veterinary medicine have the same scope in physiology, anatomy, and pathology (7, 8).

The United Nations (UN), World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) have recently established a cooperation to promote the perspective of One Health, encouraging the implementation of government policies and programs guided by it (9–11).

To this end, the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) was signed in 2014 with more than 64 nations and international non-governmental organizations supporting the collaborative approach. This will accelerate the consolidation and compliance of the requirements from the OIE Terrestrial and Aquatic Animal Health Codes, the WHO International Health Regulations (IHR), and other global health regulations for planetary health (8, 12, 13).

Despite the increase in rhetoric and support for the One Health model, it is difficult to find authentic examples of multidisciplinary or multi-sectoral efforts that transcend traditional public, animal, and environmental health “silos” (13, 14).

The ability to face threats to public and animal health effectively and efficiently requires effort and proper planning. A prerequisite for this is the training and capacitation of the public and private health sectors. However, this, within the One Health strategy, remains a challenge, especially for developing countries. This stems from competing priorities, insufficient and fragmented funding, with a lack of integration and communication between sectors (14, 15).

Some positive international experiences in this path have been reported, such as the One Health Workforce (OHW) project by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). This aims to build partnerships with institutions and leaders in Africa and Southeast Asia to assist in the identification of technical, collaborative, and organizational characteristics, important for the development of the workforce in alignment with the goals established in the GHSA and by the Joint External Evaluation– International Health Regulations (JEE – IHR) (16, 17).

In Latin America, the incorporation of the One Health strategy into government plans is timid and the integration of animal, environmental and human programs and sectors is insignificant (9–11).

In Brazil, the One Health concept itself requires recognition by health professionals and is not acknowledged by important entities such as the Federal Council of Medicine. As an effect, the power of interventions and control strategies over the environmental causes of diseases is limited, and these activities are often restricted to veterinary professionals. On the other hand, public policies for Health Surveillance (HS) have allowed the gradual insertion of One Health supportive efforts in health practices, however with little integration between their organizations (9–11, 17, 18).

An adequate surveillance system, with a strong laboratory network, is the key component of any disease prevention and control strategy. To develop an effective One Health implementation plan, it is necessary to reexamine how the existing systems are structured, resourced, and managed. These analyzes would contribute to the development and sustainability of the synergy between human, animal, and environmental health initiatives (12–14, 19).

Thus, this perspective article aims to present the potential, successes and challenges of government health strategies, programs and policies in Brazil, from One Health point of view. The present discussion is based on the analysis of the official documents, legislation and health informational systems.

One of the most important aspects of pathogen control at the human, animal, and environmental interface is the development of appropriate scientific-based Surveillance and Risk Management policies that respect transboundary regulations (12, 14, 19).

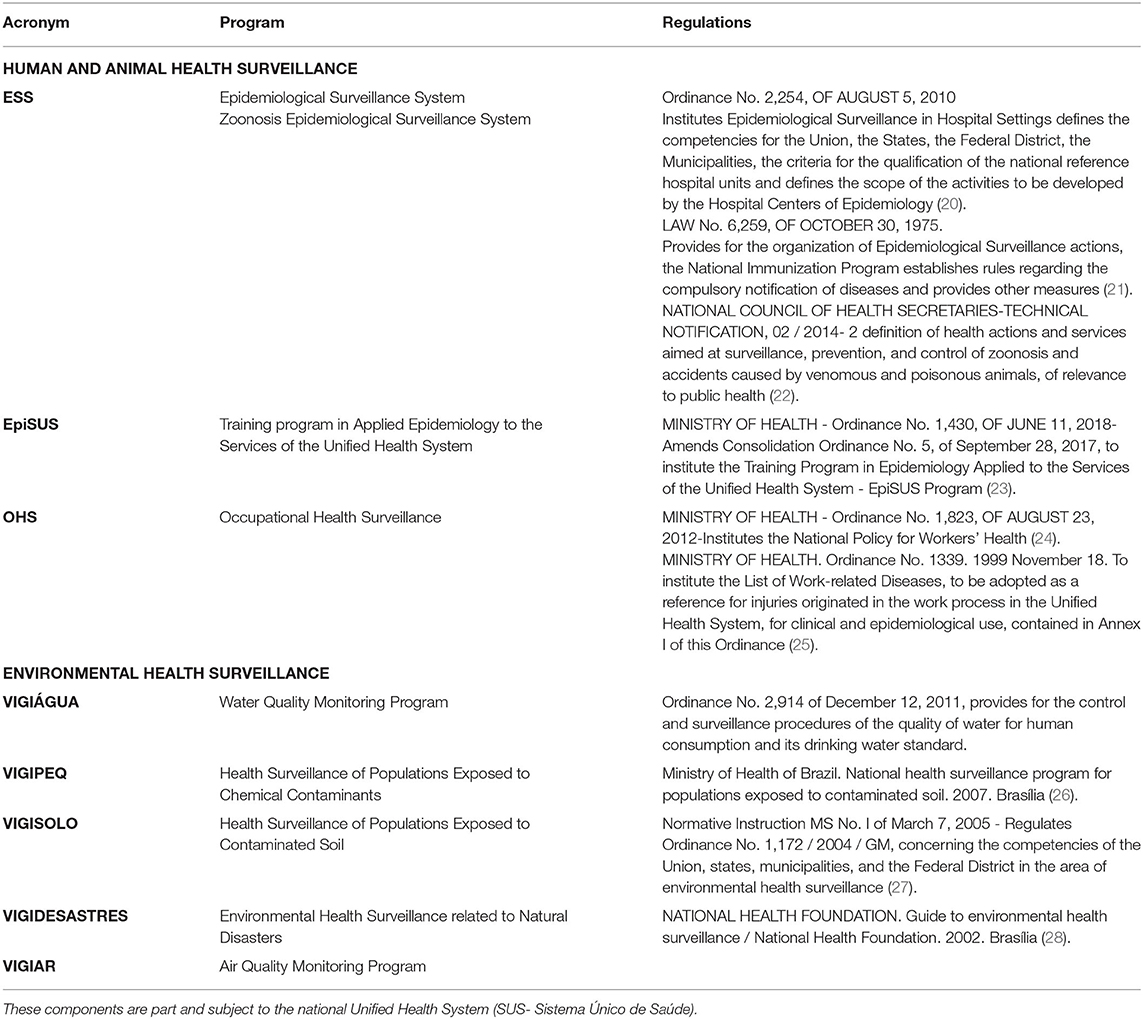

In Brazil, there is a complex system for monitoring human, animal, and environmental health conditions, based on the Health Surveillance System (HSS) and in the use of epidemiology as a planning tool. This system is supported by organizations such as the Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento- MAPA (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply) and the Sistema Único de Saúde- SUS (Unified Health System) and its respective policies, programs, regulations, and health information systems as summarized in Tables 1, 2 and described in detail in the following text (46–49).

Table 1. Organizational components of Health Surveillance System (HSS) programs and policies regarding the human, animal, and environmental health.

Table 2. Organizational components of Health Surveillance System (HSS) programs and policies regarding the human, animal, and environmental health in Brazil.

Brazil's health system emerged due to an organizational restructuring and popular social movements. With the implementation of this universal and integral system, normative actions created for stimulation of the HSS, brought with it the redefinition of health practices, allowing their greater integration with epidemiology. This surveillance system is based on four main pillars, focused mainly on conditions that affect human health, namely: Epidemiological, Sanitary, Environmental and Occupational Health Surveillance Systems (12–15, 50).

The National Environmental Health Surveillance System performs continuous and systematic monitoring of environmental conditions that may interfere with human and animal health such as water, soil, air, biological factors and vectors, environmental disasters, and accidents with contaminants. The operational instruments to make this viable are VIGIÁGUA (evaluates the quality of water for human consumption), VIGIPEQ (acts on environmental contaminating chemicals), VIGISOLO (acts on the quality of soil and cultivation activities), VIGIAR (evaluates air quality), and VIGIDESASTRES (surveillance and management of environmental disasters) (26–28, 46–48).

The Epidemiological (ES) component of the Surveillance System is responsible for systematic monitoring of adverse health events, and control measures proposition, consolidated by the National ES System and its sub-areas, allowing significant advances in the capacity to respond to health problems. ES monitors communicable and non-communicable diseases and other health problems, such as accidents, violence, and a strategic area, that performs Zoonosis Surveillance, recognizing the importance of the animal-human bond. The latter is responsible for monitoring the progress of animal diseases and accidents with venomous animals. The recognition of the importance of zoonotic diseases by the health system is extremely relevant; both for management and for the health care itself, since, on average 60–80% of human diseases are of animal origin (20–25, 49, 51–53).

In the context of ES, Brazil also has a Training program in Applied Epidemiology to the Services of the Unified Health System- EpiSUS, part of the Department of Surveillance of Communicable Diseases of the Health Surveillance System. This program counts with multidisciplinary teams, aiming to enhance the ability to respond to public health emergencies and encourage the exchange of professionals and experiences at national and international levels, to improve the national technical capacity in field epidemiology, becoming an international reference in this field (23, 51, 53–57).

The Occupational Health Surveillance, part of HSS, monitors occupational risk factors and determinants of human health conditions that are related to the production and labor processes, as well as the ones related to the work environment (23, 54–57).

The Sanitary Surveillance System, coordinated by ANVISA, the national agency for Sanitary Surveillance, works in the regulation, control, and inspection of goods, products, and environments that are directly or indirectly related to health conditions, from production to consumption. It is recognized as a set of integrated institutional, administrative, programmatic, and social strategies, guided by public policies that aim the elimination, reduction, or prevention of individual and collective health risks, based on comprehensive services and actions that are essential to the health defense and promotion. This breadth of activities justifies the fact that these actions are developed as a democratic and participatory exercise and in an articulated way, to guarantee the quality of products, services, and environments, fundamental aspects for global health. Therefore, the Sanitary Surveillance is not restricted to purely technical actions, but its driving axes are actions aimed at the strengthening of the society and citizenship to promote health and preventing risks, damages or injuries (15, 45, 49, 54, 55, 58).

Also responsible for One Health, regarding animal health, food safety, trade and transit of products of animal and vegetable origin are the programs subjected to MAPA, the institution responsible for the National Agropecuary Defense (18, 57, 58).

The Agropecuary Defense relates to all stages of agricultural and livestock production, since the registration and inspection of agricultural inputs; production, industrialization, inspection and trade of products and by-products of animal and vegetable origin; besides acting in the import and export of inputs and products, as well as in the transit of these products and animals. In this way, it would not only promote and protect animal, human and environmental health but also help to increase economic incentives by promoting security and adding value to agricultural products (12, 29–36, 59–63).

Also subject to the National Agricultural Defense services, are the Animal Health Programs, namely: National Equine Health Program, National Poultry Health Program, National Program for the Control and Eradication of Brucellosis and Tuberculosis, National Goat and Sheep Health Program, National Herbivore Rabies Control Program, National Apiculture Health Program, National Program for the Eradication and Prevention of Foot-and-Mouth Disease, coordinated by MAPA (38–44, 61–64).

These programs aim to prevent, control, or eradicate diseases of public health importance or that may threaten international trade, ensuring animal health through health education activities; epidemiological studies; the inspection of breeding establishments, fiscalization of agricultural events and animal transit, notifying the occurrence of these diseases, in addition to guaranteeing the competitive value of the products in the international market (38–44, 61–64).

Furthermore, an operational instrument for Agropecuary Defense is VIGIAGRO, MAPA's instance that regulates the flow of animals, products, and agricultural inputs in frontiers, to ensure their safety and quality, preventing or minimizing potential risks to the One health (14, 18, 64–66).

In this construct, the programs and services presented have the potential for the insertion of the multidisciplinary and integrative approach of One Health, with intra and intersectoral collaboration Tis approach is appropriate to the current context of growing concerns about the consequences of the interactions between humans, animals, and the environment, in a productive framework based on capitalist ideals (58, 59, 67–69).

The importance of the policies and operationalization referred in this perspective article is acknowledged, but several challenges are found for the consolidation of its potential, the main ones being the disarticulation, the verticality of the actions, and the overlapping of attributions (1–5).

The central goals of the One Health model include altering the organization's work from a vertical and hierarchical approach to a horizontal and integrated one, in addition to moving from individual “silos” to a transdisciplinary functioning (1, 2, 14).

The difficulties in achieving these goals and in the integration between the spheres that work animal, human, and environmental health start in the professional training of those who work in these fields. Few individuals enter the workforce with crosscutting skills to thrive in transdisciplinary or multi-sectoral teams (14, 15).

The increase in the number and distribution of qualified personnel has proved to be one of the main limitations in most developing regions. This limitation, added to the financial, structural, and bureaucratic constraint faced by this sector, prevents it from satisfactorily exercising its potential, putting global health at risk (15).

The need and benefits of an integrated surveillance system to better understand the emergence and epidemiology of diseases have been demonstrated. This should count with a health care notification system and a comprehensive national database including environmental monitoring, human and animal health diagnostic systems, essential components of an integrated surveillance system, and for the implementation of One Health (12–15, 61).

Brazil has all these components, but they do not articulate or communicate. Even more, they sometimes overlap their attributions and compete for authority and hierarchy. The information produced by different organizations, rarely crosses that 'silo' that produced them, even though it could support health actions as a whole, producing and using information and communication in a shared way, to better instrumentalize the intervention (15).

For example, information on the incidence and prevalence of work-related illnesses could be used to modify production processes, minimizing the risks and potential damage. The occurrence of water and foodborne diseases could contribute to the improvement of the performance of Agropecuary Defense, among others. Just as, information about environmental health can be useful to guide all production processes, to help understanding the epidemiology and natural history of diseases, allowing the intervention in their origins. This would promote cheaper, more assertive, and definitive solutions to health problems and demands, making individuals, animals, and the environment healthier, more productive, and sustainable (12–15).

While some progress has been done, there is a need for continued investment and political commitment to address the persistent challenges in public health. As it can be seen in the Tables 1, 2, the programs are not recent efforts and some of them are more than 20 years old. This is also a challenge since they are sealed in their 'silos', without undergoing major changes over the years and without communicating with other programs and institutions. Still in this sense, it is clear that changes in global initiatives and situations such as the pandemic due to the coronavirus have little or no influence on the construction of regulatory frameworks.

The One Health initiatives are of complex consolidation from both a political, technical, and sanitary perspective (12, 14, 15). The implementation of the strategies presented here, associated with the complex movement of political and administrative restructuring in Brazil represented progress in the direction of producing more effective interventions, however, it further aggravated the fragmentation and sectorization of health actions. This resulted in a surveillance based primarily on a routine centered on the notification and investigation of cases and the transmission of data to other levels for the consolidation of bases and information systems, frequently not reaching the final goal of triggering an intervention (15).

The lack of articulation and use of health information for planning interventions can be evidenced with a contemporary example. The COVID-19 pandemic and the recent worsening of it at the national level in early 2021 are the results of a lack of planning and intervention by governmental health spheres that have proved inefficient and non-resolute. Instead of applying the information, fees, numbers to equip their infrastructure and instruct their professionals, the highest governmental spheres have chosen to hide and fragment the health information consolidated by the Epidemiological Surveillance Systems and not apply it for planning and structuring measures to mitigate the health crisis (70–72).

The integration and articulation between health actions, organizations, and policies would promote greater effectiveness and efficiency of health interventions, promoting global health and expanding the response capacity. However, there are still restrict limits to the autonomy of federal entities in Brazil, perpetuating an excess of verticality in programs and decisions, which makes it difficult to move toward the integration of surveillance systems in the perspective of democratizing the health practices (15, 59, 73).

The action of these entities and services should be in the sense of sharing attributions and responsibilities, without leaving behind the technical specification of each of the areas. This would imply new roles, as well as new dynamics, relationships, and innovative practices at all levels, which denotes the complexity and challenge of its implementation (59, 73, 74).

Thus, it is proposed to work, from the One Health approach, in an articulated and integrated set of actions, which assume specific configurations according to the environmental, animal, and human health situation of each territory, transcending the institutionalized spaces of the health services system, the verticality, and hierarchy of agencies and programs. Thus, seeking a dialogue between “cause control,” “risk control” and “damage control” through the redefinition of the object, the means of work, activities, and technical and social relations (12, 13, 15).

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The authors contributed equally to all phases of the manuscript construction and revision.

The authors acknowledge the financial support from CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), FAPEMIG (Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa de Minas Gerais), and CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeicoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior). MM is supported by CNPq.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors acknowledge the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior for the support in all scientific endeavors.

1. McEwen SA, Collignon PJ. Antimicrobial resistance: a one health perspective. Microbiol Spectr. (2018) 6:521–47. doi: 10.1128/9781555819804.ch25

2. Zinsstag J, Crump L, Schelling E, Hattendorf J, Maidane YO, Ali KO, et al. Climate change and One Health. FEMS Microbiol Lett. (2018) 365:fny085. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fny085

3. Capua I, Cattoli G. One health (r) evolution: learning from the past to build a new future. Viruses. (2018) 10. doi: 10.3390/v10120725

4. Ryu S, Kim BI, Lim JS, Tan CS, Chun BC. One health perspectives on emerging public health threats. J Prev Med Public Health. (2017) 50:411–4. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.17.097

5. Conrad PA, Mazet JA, Clifford D, Scott C, Wilkes M. Evolution of a transdisciplinary “One Medicine–One Health” approach to global health education at the University of California, Davis. Prev Vet Med. (2009) 92:268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2009.09.002

6. Osburn B, Scott C, Gibbs P. One world—one medicine—one health: emerging veterinary challenges and opportunities. Rev Sci Tech. (2009) 28:481. doi: 10.20506/rst.28.2.1884

7. ATLAS, Ronald M. One Health: Its origins and Future. One Health: The Human-Animal-Environment Interfaces in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer (2012). p. 1–13.

8. Zinsstag J, Schelling E, Waltner-Toews D, Tanner M. (2011). From “one medicine” to “one health” and systemic approaches to health and well-being. Prev Vet Med. (2011) 101:148–56. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2010.07.003

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One Health Basics. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/index.html (accessed October 20, 2020).

10. Organização Mundial da Saúde. Organização das Nações Unidas para Alimentação e Agricultura, Organização Mundial da Saúde Animal. A Tripartite Concept Note. Geneva (2010) Available online at: https://www.who.int/influenza/resources/documents/tripartite_concept_note_hanoi/en/ (accessed October 20, 2020).

11. Evans BR, Leighton FA. A history of one health. Rev Sci Tech. (2014) 33:413–20. doi: 10.20506/rst.33.2.2298

12. Wondwossen GA, Dupouy-Camet J, Newport MJ, Oliveira CJB, Schlesinger LS, Saif YM, et al. The global one health paradigm: challenges and opportunities for tackling infectious diseases at the human, animal, and environment interface in low-resource settings. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2014) 8:e3257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003257

13. Cleaveland S, Sharp J, Abela-Ridder B, Allan KJ, Buza J, Crump JA, et al. One health contributions towards more effective and equitable approaches to health in low-and middle-income countries. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. (2017) 372:20160168. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0168

14. Chatterjee P, Kakkar M, Chaturvedi S. Integrating one health in national health policies of developing countries: India's lost opportunities. Infect Dis Poverty. (2016) 5:87. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0181-2

15. Oliveira CMd, Cruz MM. Sistema de Vigilância em Saúde no Brasil: avanços e desafios. Saúde em Debate. (2015) 39:255–67. doi: 10.1590/0103-110420151040385

16. World Health Organization. Joint external evaluation tool: International Health Regulations, (2005). Geneva: World Health Organization (2018).

17. Schwind JS, Gilardi KVK, Beasley VR, Mazet JAK, Smith WA. Advancing the ‘One Health' workforce by integrating ecosystem health practice into veterinary medical education: the envirovet summer institute. Health Educ J. (2016) 75:170–83. doi: 10.1177/0017896915570396

18. Vieira, E. S de S. Defesa Agropecuária e Inspeção de Produtos de Origem Animal: uma Breve Reflexão sobre a Operação Carne Fraca e Possíveis Contribuições ao Aprimoramento dos Instrumentos Normativos Aplicáveis ao Setor. Brasília: Núcleo de Estudos e Pesquisas/CONLEG/Senado, Março/2017 (Texto para Discussão n° 230).

19. Filho ODAR. O papel do Vigiagro na prevenção da introdução de pragas quarentenárias no Brasil. Anais do Seminário Internacional sobre Pragas Quarentenárias Florestais. (2012). p. 43.

20. Brasil. Lei N° 8.171. 1991 January 17. Available online at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8171.htm (accessed March 25, 2021).

21. Brasil. Lei N° 6.259. 1975 October 30. Available online at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l6259.htm (accessed March 25, 2021).

22. CONASS. Nota Técnica 02. 2014. Available online at: https://www.conass.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/NT-02-2014-Zoonoses.pdf (accessed March 25, 2021).

23. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Portaria N° 1430. 2018 June 11. Available online at: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2018/prt1430_12_06_2018.html (accessed March 25, 2021).

24. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Portaria N° 1.823. 2012 August 23. Available online at: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2012/prt1823_23_08_2012.html (accessed March 23, 2021).

25. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Portaria N° 1.339. 1999 November 18. Available online at: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/1999/prt1339_18_11_1999.html (accessed March 23, 2021).

26. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Portaria N° 2.914. 2011 December 12. Available online at: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2011/prt2914_12_12_2011.html (accessed March 23, 2021).

27. Diário oficial da União. Instrução Normativa N° 20. 2020 March 13. Available online at: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/instrucao-normativa-n-20-de-13-de-marco-de-2020-247887393 (accessed March 25, 2021).

28. Fundação Nacional de Saúde. Guia de vigilância ambiental em saúde/Fundação Nacional de Saúde. 2002. Brasília

29. Brasil. Lei N° 8.171. 1991 January 17. Available online at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8171.htm (accessed March 25, 2021).

30. Brasil. Decreto N° 30.691. 1952 March 29. Available online at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/1950-1969/d30691.htm (accessed March 25, 2021).

31. Brasil. Lei N° 6.198. 1974 December 26. Available online at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/1970-1979/L6198.htm (accessed March 25, 2021).

32. Brasil. Lei N° 7.802. 1989 July 11. Available online at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l7802.htm (accessed March 25, 2021).

33. Brasil. Lei N° 7.608. 1988 November 8. Available online at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/1980-1988/l7678.htm (accessed March 25, 2021).

34. Brasil. Lei N° 8.918. 1994 July 14. Available online at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8918.htm (accessed March 25, 2021).

35. Brasil. Lei N° 24.114. 1934 April 12. Available online at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/1930-1949/d24114.htm (accessed March 25, 2021).

36. Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento. Instrução Normativa N° 51. 2011 November 4. Available online at: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/insumos-agropecuarios/insumos-pecuarios/alimentacao-animal/arquivos-alimentacao-animal/legislacao/instrucao-normativa-no-51-de-4-de-novembro-de-2011.pdf/view (accessed March 25, 2021).

37. Diário Oficial da União. Instrução Normativa N° 91. 2020 September 18. Available online at: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/instrucao-normativa-n-91-de-18-de-setembro-de-2020-278692423 (accessed March 25, 2021).

38. Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento. Instrução Normativa N° 6. 2018 January 16. Available online at: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/laboratorios/credenciamento-e-laboratorios-credenciados/legislacao-metodos-credenciados/diagnostico-animal%20arquivos/InstruoNormativaMAPAn6de16dejaneirode2018AprovadaasDiretrizesGeraisparaPreveno.doMORMO.pdf/view (accessed March 25, 2021).

39. Secretaria de Agricultura e Abastecimento do Estado de São Paulo. Portaria 193. 1994 September 19. Available online at: https://www.defesa.agricultura.sp.gov.br/legislacoes/portaria-mapa-193-de-19-09-1994,369.html (accessed March 25, 2021).

40. Diário Oficial da União. Instrução Normativa N° 10. 2017 March 3. Available online at: < https://www.in.gov.br/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/19124587/do1-2017%E2%80%9306-20-instrucao-normativa-n-10-de-3-de-marco-de-2017%E2%80%9319124353 (accessed March 25, 2021).

41. Agência Estadual de Defesa Sanitária Animal e Vegetal do Mato Grosso do Sul. Programa Nacional de Sanidade de Caprinos e Ovinos. (2020). Available online at: https://www.iagro.ms.gov.br/programa-nacional-de-sanidade-caprinos-e-ovinos-pnsco/ (accessed March 25, 2021).

42. Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento. Instrução Normativa N° 5. 2000 March 31. Available online at: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/inspecao/produtos-vegetal/legislacao-1/biblioteca-de-normas-vinhos-e-bebidas/instrucao-normativa-no-5-de-31-de-marco-de-2000.pdf/view (accessed March 25, 2021).

43. Diário Oficial da União. Instrução Normativa N° 16. 2018 May 8. Available online at: https://www.in.gov.br/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/19599014/do1-2018-06-07-instrucao-normativa-n-16-de-8-de-maio-de-2018-19598923 (accessed March 25, 2021).

44. Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento. Instrução Normativa MAPA N° 44. 2007 October 02. Available onine at: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/sanidade-animal-e-vegetal/saude-animal/programas-de-saude-animal/febre-aftosa/documentos-febre-aftosa/instrucao-normativa-mapa-no-44-de-02-de-outubro-de-2007.pdf/view (accessed March 25, 2021).

45. Brasil. Lei N° 9.782. (1999). Available online at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9782.htm (accessed March 25, 2021).

46. Queiroz ACL, Cardoso LSM, Silva SCF, Heller L, Cairncross S. Programa Nacional de Vigilância em Saúde Ambiental Relacionada à Qualidade da Água para Consumo Humano (Vigiagua): lacunas entre a formulação do programa e sua implantação na instância municipal. Saúde e Sociedade. (2012) 21:465–78. doi: 10.1590/S0104-12902012000200019

47. Souza GDS, Costa LCAD, Maciel AC, Reis FDV, Pamplona YDAP. (2017). Presença de agrotóxicos na atmosfera e risco à saúde humana: uma discussão para a Vigilância em Saúde Ambiental. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. (2017) 22:3269–80. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320172210.18342017

48. Augusto LGDS. Saúde e vigilância ambiental: um tema em construção. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde. (2003) 12:177–87. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742003000400002

49. De Freitas Guimarães F, Baptista AAS, Machado GP, Langoni H. Ações da vigilância epidemiológica e sanitária nos programas de controle de zoonoses. Veterinária e Zootecnia. (2010) 17:151–62.

50. Jorcelino TM, de Rezende ME, Silva MS. O sistema de vigilância agropecuária internacional e de vigilância em saúde ambiental no Distrito Federal. in Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia-Resumo em anais de congresso (ALICE). Brasilia: Distrito Federal. (2020) 2:2020.

51. Pinheiro TMM, Machado JMH, Ribeiro FSN. A vigilância em saúde do trabalhador. In: Conferência Nacional de Saúde do Trabalhador. Brasilia: Distrito Federal. (2005).

52. Portal Brasileiro de Dados Abertos. Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento - MAPA. (2019). Available online at: http://dados.gov.br/organization/about/ministerio-da-agricultura-pecuaria-e-abastecimento-mapa (accessed September 21, 2020).

53. Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento - MAPA. Programa Nacional de Sanidade Avícula (PNSA). (2020). Available online at: http://antigo.agricultura.gov.br/assuntos/sanidade-animal-e-vegetal/saude-animal/programas-de-saude-animal/pnsa/programa-nacional-de-sanidade-avicola-pnsa (accessed September 21, 2020).

54. Agência Estadual de Defesa Sanitária Vegetal e Animal do Mato Grosso do Sul - IAGRO. Programa Nacional de Controle da Raiva dos herbívoros e Outras Encefalopatias - PNCERH. (2019) Available online at: https://www.iagro.ms.gov.br/programa-nacional-de-controle-da-raiva-dos-herbivoros-e-outras-encefalopatias-pncerh/#:~:text=O%20Programa%20Nacional%20de%20Controle,vigil%C3%A2ncia%20epidemiol%C3%B3gica%20e%20outros%20procedimentos (accessed September 21, 2020).

55. Tilocca B, Soggiu A, Musella V, Britti D, Sanguinetti M, Urbani A, et al. Molecular basis of COVID-19 relationships in different species: a one health perspective. Microb Infect. (2020) 22:218–20. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.03.002

56. Menna LF, Santaniello A, Todisco M, Amato A, Borrelli L, Scandurra C, et al. The Human-animal relationship as the focus of animal-assisted interventions: a one health approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:3660. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193660

57. O'Brien MK, Macy W, Pelican K, Perez AM, Errecaborde KM. Transforming the One Health workforce: lessons learned from initiatives in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Rev Sci Tech. (2019) 38:239–50. doi: 10.20506/rst.38.1.2956

58. Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde. Ministério da Saúde EpiSUS – “Além das Fronteiras.” Contribuindo para o Fortalecimento da Epidemiologia Aplicada aos Serviços do SUS. Brasília: OPAS, Ministério da Saúde (2015).

59. Teixeira CF, Paim JS, Vilasbôas AL. SUS, modelos assistenciais e vigilância da saúde. Fundamentos da vigilância sanitária. Inf Epidemiol Sus. (1998) 7:7–28.

60. Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento - MAPA. Sanidade de Equídeos (2017). Available online at: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/sanidade-animal-e-vegetal/saude-animal/programas-de-saude-animal/sanidade-de-equideos (accessed September 21, 2020).

61. Defesa Agropecuária do Estado de SP. Programa Estadual de Controle e Erradicação da Brucelose e Tuberculose Animal (PECEBT). (2020). Available online at: https://www.defesa.agricultura.sp.gov.br/www/programas/?/sanidade-animal/programa-estadual-de-controle-e-erradicacao-da-brucelose-e-tuberculose-animal-pecebt-sp/&cod=59#:~:text=O%20Programa%20Nacional%20de%20Controle,promover%20a%20competitividade%20da%20pecu%C3%A1ria (accessed September 21, 2020).

62. Freitas MTDD. Atuação do Médico Veterinário na Vigilância Agropecuária Internacional (VIGIAGRO) (Bachelor's thesis). Departamento de Medicina Veterinária, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Recife, Brasil (2018).

63. Mulder AC, Kroneman A, Franz E, Vennema H, Tulen AD, Takkinen J, et al. HEVnet: a One Health, collaborative, interdisciplinary network and sequence data repository for enhanced hepatitis E virus molecular typing, characterization and epidemiological investigations. Eurosurveillance. (2019) 24:1800407. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.10.1800407

64. Mitchell ME, Alders R, Unger F, Nguyen-Viet H, Le TTH, Toribio JA. The challenges of investigating antimicrobial resistance in Vietnam-what benefits does a One Health approach offer the animal and human health sectors? BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1–12.

65. Johnson J, Howard K, Wilson A, Ward M, Gilbert GL, Degeling C. Public preferences for One Health approaches to emerging infectious diseases: a discrete choice experiment. Soc Sci Med. (2019) 228:164–71. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.03.013

66. Dente MG, Riccardo F, Bolici F, Colella NA, Jovanovic V, Drakulovic M, et al. Implementation of the one health approach to fight arbovirus infections in the Mediterranean and Black Sea region: assessing integrated surveillance in Serbia, Tunisia, and Georgia. Zoonoses Public Health. (2019) 66, 276–87. doi: 10.1111/zph.12562

67. Garcia SN, Osburn BI, Cullor JS. A one health perspective on dairy production and dairy food safety. One Health. (2019) 7:100086. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2019.100086

68. MAPA-Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento/Gabinete do Ministro. PORTARIA N° 562. 2018 April 11. MAPA- Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento/Gabinete do Ministro

69. World Health Organization. One Health. (2017). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/one-health (accessed August 15, 2020).

70. González-Bustamante B. Evolution and early government responses to COVID-19 in South America. World Dev. (2021) 137:105180. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105180

71. Jorge DCP, Rodrigues MS, Silva MS, Cardim LL, da Silva NB, Silveira IH, et al. Assessing the nationwide impact of COVID-19 mitigation policies on the transmission rate of SARS-CoV-2 in Brazil. medRxiv. (2021) 2021:2020–06. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.26.20140780

72. Lasco G. Medical populism and the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Public Health. (2020) 15:1417–29. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1807581

73. Campos CEA. O desafio da integralidade segundo as perspectivas da vigilância da saúde e da saúde da família. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. (2003) 8:569–84. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232003000200018

Keywords: Health Surveillance, agricultural defense, animal health, animal-human bond, zoonosis

Citation: Espeschit IdF, Santana CM and Moreira MAS (2021) Public Policies and One Health in Brazil: The Challenge of the Disarticulation. Front. Public Health 9:644748. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.644748

Received: 21 December 2020; Accepted: 27 April 2021;

Published: 04 June 2021.

Edited by:

Christina Pettan-Brewer, University of Washington, United StatesReviewed by:

Maxine Anne Whittaker, James Cook University, AustraliaCopyright © 2021 Espeschit, Santana and Moreira. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Isis de Freitas Espeschit, aXNpc2RlZnJlaXRhc2VzcGVzY2hpdEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.