95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

POLICY BRIEF article

Front. Public Health , 13 August 2021

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.640205

This article is part of the Research Topic Women in Science: Public Mental Health 2021 View all 9 articles

The rapid evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emergency involved Italy as the first European country. Meanwhile, China was the only other country to experience the emergency scenario, implementing public health recommendations and raising concerns about the mental health of the population. The Italian National Institute of Health [Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS)] reviewed relevant scientific literature in mental health to evaluate the best clinical practices and established the collaboration with the WHO, World Psychiatry Association, and China to support the public health system in a phase of acute emergency. This process permitted the definition of organizational and practical-operational Italian guidelines for the protection of the well-being of healthcare workers. These guidelines have been extensively disseminated within the Italian territory for maximum stakeholder utilization.

Starting from February 2020, Italy was the first European country facing the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emergency. On March 8, 2020, several Northern Provinces of Italy were placed under lockdown, and on March 10, 2020, at 00:30, any movement of people across the whole Italian national territory was forbidden, unless motivated by compelling reasons of health or work. All Italian people suddenly experienced confinement at home, physical distancing, while simultaneously receiving dramatic news from all media concerning the pandemic evolution and hospital emergencies, with potential negative impacts on the mental health of the people, as shown in a recent German study (1).

The transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was particularly rapid and dramatic in northern Italy, where COVID-19 health workers were suddenly asked to implement changes in activities and processes of care, such as team and workspace procedures. Frontline health workers were, and continue to be among the worst affected, facing shortages of personal protective equipment and enduring exhausting work schedules (2).

At the peak of the Italian pandemic, China was the only other country to experience the emergency scenario and lockdown. At that time, China had already implemented a series of public health recommendations and raised concerns about the mental health of the general population and high-risk groups (3).

As a consequence of the lockdown, Italian people experienced a sharp change in their behavior as well as living and working environment. Prolonged confinement, change of routines, lack of economic resources, and uncertainty of lockdown duration, caused several adverse psychological effects such as stress, anxiety, depression, and frustration in the general population (4). Evidence suggested that women were more often reporting anxiety symptoms. Indeed, women were almost three times more likely than men to report anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic (5, 6). Moreover, the school closure and quarantine have placed considerable psychological stress on children and adolescents that were unable to maintain their interpersonal life and their free time activities and sports (7). Social media and social networks could be used as a tool for online counseling, restoring daily routines, and communication. However, social media activities should be considered with caution, as the length and frequency of media consumption is a significant risk factor associated with increased anxiety and depression (8, 9). Moreover, susceptibility to mental health problems was compounded by the experience of dramatic life events, such as bereavement, unavailability of final farewell in terminal situations, and parental separation due to confirmed or suspected infection. Another important behavioral change caused by the lockdown and the parallel closure of many outpatients mental health services and day-centers was represented by the sudden increase in the amount of time spent face-to-face between a patient and his/her family members, increasing the risk of relapse, higher levels of symptoms, and poorer functioning in patients with psychotic disorders (10).

Public health services received detailed instructions on overcoming challenges in providing mental healthcare (11), especially for individuals with existing mental health conditions, who were at high risk of negative outcomes (12–15). For example, efforts were made to provide telehealth interventions, which helped some, but proved challenging for individuals with higher needs of support, such as people with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. While telehealth has been advocated as an effective strategy to keep contacts with patients in treatment, organize a triage of new requests, respond to requests of changes in medication profiles, and set up videoconferencing with patients needing psychological support and counseling, it also raises several problems (e.g., effectiveness, quality, and therapeutic relationship established with a patient) which should be carefully investigated (16).

The Italian National Institute of Health [Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS)] consequently elaborated specific guidelines for COVID-19 diagnostic and care procedures, particularly for individuals in the autistic spectrum and/or with intellectual disabilities, to optimize the management of sharp changes in the living and working environment and daily routine of such individuals. The main areas addressed by the ISS guidelines included strategies to promote the training of professionals, reorganize clinical and care activities through the development and maintenance of remote interventions, scheduled interventions in the presence, and patient management in the long-term facilities.

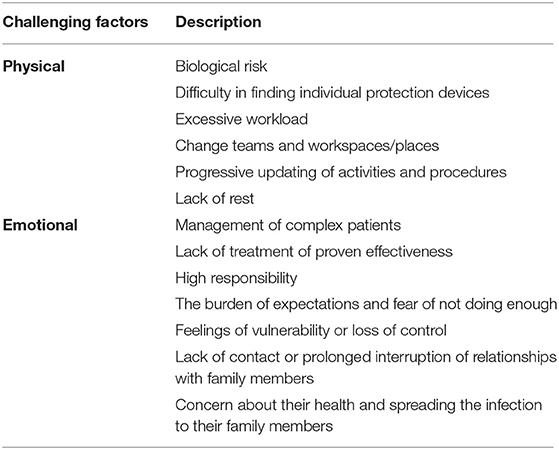

Finally, frontline health workers found themselves exposed to biological risk factors, social isolation from family members, and subsequently, intensified challenges of recovery from physical and emotional distress (as shown in Table 1). Moreover, in COVID-19 care settings, they experienced a lack of effective interventions and changes in the ways of communicating with the families of patients (17). Overburdening and prolonged stress affects attention focus comprehension and decision-making, which can have a lasting effect on overall well-being (11). Therefore, the protection of health professionals and the promotion of their health and well-being are among the key components of public health measures in tackling the COVID-19 epidemic (11, 18–22).

Table 1. Physical and emotional challenging factors of health professional workers as a consequence of the rapid evolution of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-Cov-2) emergency {Italian National Institute of Health [Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS)] Working Group on Mental Health and Emergency COVID-19, 2020}.

The ISS is the main Italian center for research, control, and technical-scientific advice on public health and health guidance policies, as informed by scientific evidence alongside the Ministry of Health, the Regions, and the entire National Health Service. The ISS, in this as in other situations, cooperates with experts from other international organizations (e.g., WHO, UNICEF, Save The Children, and World Psychiatry Association). Only China, at that time, was devoted to face the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences on the mental health of the people. The ISS researchers reviewed relevant scientific literature in mental health to evaluate the best clinical practices. We established the collaboration with the World Psychiatric Association Action Plan 2021–23 Working Groups on Intellectual Developmental Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder, consolidating a working group that formulated advice to tackle mental distress for people with intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder, SIDiN (23). We also identified the Chinese guideline entitled “Guideline for Psychological Adjustment During the COVID-19 Pandemic” produced by the Disease Control and Prevention Department, National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. This document offered psychological adjustment guidance for the general population and specific at-risk groups (e.g., elderly, children, teenagers, pregnant women, people in home isolation, confirmed and suspected patients with COVID-19 and their relatives, and relatives of people dying of COVID-19), such as frontline workers for COVID-19. In addition, the guidelines described strategies for the adjustment of different psychological problems such as sleep problems, anxiety, panic, and worries about being infected.

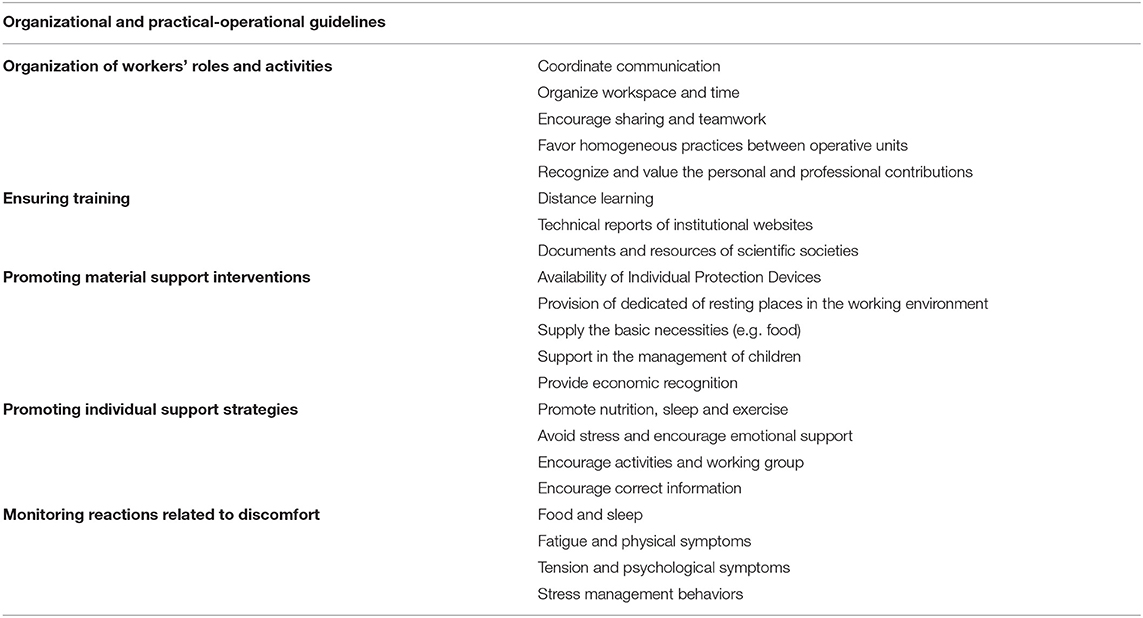

The Research Coordination and Support Service of the ISS collaborated with the Nottingham Ningbo GRADE Center and researchers of the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and Children's Hospital of Fudan University to translate and adapt the aforementioned guidelines for an Italian context, with consideration of contextual and cultural differences. The translation of Chinese guidelines has been useful in the preparation of the organizational and practical-operational guidelines for the health workers report “Interim guidance for the appropriate support of the health workers in the SARS-CoV-2 emergency scenario,” developed by the ISS Mental Health and Emergency Working Group COVID-19, which is accessible on the institutional ISS website (https://www.iss.it/en/rapporti-iss-covid-19-in-english/). This ISS report is freely available and has been extensively disseminated within the Italian territory for maximum stakeholder utilization. The report provides guidelines to organize the roles and activities of workers, ensure training (e.g., distance training, technical reports), promote material in support of interventions, and monitor psychological well-being such as individual support strategies, monitoring of reactions related to discomfort, activate psychological and psychiatry support, psychological, psychiatric, and psychopharmacological interventions (as shown in Table 2).

Table 2. The management of physical and emotional challenging factors of health professional workers during the SARS-Cov-2 emergency scenario (ISS Working Group on Mental Health and Emergency COVID-19, 2020).

The collaboration between Italy and China, established in a phase of acute emergency, has been fundamental as a basis for the definition of Italian guidelines dedicated to public mental health and promotion of the well-being of health workers, whose protection is a key component of public health measures in addressing the COVID-19 epidemic (15). The process was supported by consultation with the World Psychiatry Association and mental health guidelines were disseminated via an e-meeting organized by the WHO working in Ethiopia on Mental Health and COVID-19. This document describes an evidence-based process that can be taken as an example for future international collaborations to support the public health systems.

MLS: conceptualization and funding acquisition. MLS, FS, GG, and JX: writing the original draft preparation, writing the review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank Francesca Fulceri, Martina Micai, and Angela Caruso for their additional contribution.

1. Bendau A, Petzold MB, Pyrkosch L, Maricic LM, Betzler F, Rogoll J, et al. Associations between COVID-19 related media consumption and symptoms of anxiety, depression and COVID-19 related fear in the general population in Germany. Eur Arch of Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2020) 271:283–91. doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01171-6

2. ISS Working Group on Mental Health and Emergency Covid-19. Interim guidance for the appropriate support of the health workers in the SARS-CoV-2 emergency scenario. Version of May 28. (2020). Available online at: https://www.iss.it/rapporti-iss-covid-19-in-english (accessed July 6, 2020)

3. Li W, Yang Y, Liu ZH, Zhao YJ, Zhang Q, Zhang L, et al. Progression of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:1732–8. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45120

4. Serafini G, Parmigiani B, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Sher L, Amore M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM. (2020) 113:531–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201

5. Özdin S, Bayrak Özdin S. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2020) 66:504–11. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051

6. Wang Y, Di Y, Ye J, Wei W. Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychol Health Med. (2020) 30:1–10. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817

7. Poletti M, Raballo A. Coronavirus disease 2019 and effects of school closure for children and their families. JAMA Pediatr. (2021) 175:210. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3586

8. Nekliudov NA, Blyuss O, Cheung KY, Petrou L, Genuneit J, Sushentsev N, et al. Excessive media consumption about COVID-19 is associated with increased state anxiety: outcomes of a large online survey in Russia. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e20955. doi: 10.2196/20955

9. Ni MY, Yang L, Leung CMC, Li N, Yao XI, Wang Y, et al. Mental health, risk factors, and social media use during the COVID-19 epidemic and cordon sanitaire among the community and health professionals in Wuhan, China: cross-sectional survey. JMIR Ment Health. (2020) 7:e19009. doi: 10.2196/19009

10. Carpiniello B, Tusconi M, Zanalda E, Di Sciascio G, Di Giannantonio M. Psychiatry during the Covid-19 pandemic: a survey on mental health departments in Italy. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02997-z

11. de Girolamo G, Cerveri G, Clerici M, et al. Mental health in the covid-19 emergency: the Italian response. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:1–3. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1276

12. Carmassi C, Bertelloni CA, Dell'Oste V, Barberi FM, Maglio A, Buccianelli B, et al. (2020)a. Tele-psychiatry assessment of post-traumatic stress symptoms in 100 patients with Bipolar Disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic social-distancing measures in Italy. Front Psychiatry. 11:580736. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.580736

13. Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, Zhang L, Zhao X, Zou Y, et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069

14. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-MentalHealth-2020.1. (accessed July 6, 2020)

15. Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e21. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30090-0

16. Zhou X, Snoswell CL, Harding LE, Bambling M, Edirippulige S, et al. The role of telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemed J E Health. (2020) 26:377–9. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0068

17. COMMUNICoViD. and Position Paper. How to communicate with families living in complete isolation OINT DOCUMENT: SIAARTI Aniarti SICP SIMEU. (2020). Available online at: https://www.aniarti.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CommuniCoViD_eng-18apr20.pdf. (accessed July 6, 2020)

18. Carmassi C, Foghi C, Dell'Oste V, Cordone A, Bertelloni CA, Bui E, et al. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: What can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 292:113312. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113312

19. Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang BX, et al. (2020). The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 7:e14. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X

20. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

21. Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, health policies, international collaboration, Italian guidelines

Citation: Scattoni ML, Starace F, de Girolamo G and Xia J (2021) An Italy-China Collaboration for Promoting Public Mental Health Recommendations During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 9:640205. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.640205

Received: 17 February 2021; Accepted: 20 July 2021;

Published: 13 August 2021.

Edited by:

Eric Hahn, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyCopyright © 2021 Scattoni, Starace, de Girolamo and Xia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Luisa Scattoni, bWFyaWFsdWlzYS5zY2F0dG9uaUBpc3MuaXQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.