94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 15 February 2021

Sec. Children and Health

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.631492

This article is part of the Research Topic The Effects of Climate Change and Environmental Factors on Exercising Children and Youth View all 5 articles

The rapid development of cities results in many public health and built-up environmental problems, which have vital impacts on children's growth environment, the development of children, and city contradictions. There is a lack of children being a main concern when constructing new urban areas or reconstructing old districts. Children's activity spaces tend to be standardized and unified (kit, fence, and carpet) “KFC style” designs, which leads to the urban neighborhood space and the environment being insufficient to attract children to conduct activities. Therefore, starting from the urban neighborhood space environment, this paper explores what kind of spatial environment is needed for children's physical activity and its impact on children's physical activity. Taking six residential areas in the Changchun Economic Development Zone as the research object, based on the theory of children's ability development and game value, this paper uses the Woolley and Lowe evaluation tool to quantify the impact of the theory on the urban neighborhood space environment and children's physical activity. It can be confirmed that there is a significant correlation between the spatial characteristics of an urban neighborhood and the general signs of the environment on the duration and intensity of the physical activity of children. The results show that: (1) the differences in children's ages result in differences in the duration and intensity of children's physical activity in the urban neighborhood space environment; (2) the open space factor of the neighborhood space has the most significant influence on the duration of children's physical activity; (3) in terms of the environmental characteristics, whether children can be provided with education and learning opportunities has a significant impact on the duration of children's physical activity; (4) there is a significant positive correlation between children's age and the duration and intensity of the physical activity, exercise type, and imaginative activity. These results show that the urban neighborhood space environment can affect the duration of children's physical activity. In future urban residential area planning and design, urban children can meet the self-demand of physical activity in the neighborhood space through the reasonable balance and combination of neighborhood space characteristics and environmental characteristics.

A large number of studies have focused on the link between child health problems and environmental characteristics, such as the impact of neighborhood spatial security on physical activity (1), and the report on the impact of low-income neighborhoods on youth physical activity (2). It mainly follows the logic of “spatial demand-influencing factor-planning strategy” (3, 4), and makes a systematic study on the demand and planning strategy of urban children's outdoor public space (5, 6). Western countries that have experienced earlier urbanization are gradually aware of the negative impact of rapid urbanization on children's physical and mental development. High-rise and high-density urban development has squeezed children's public activity spaces, such as outdoor playgrounds and green spaces (7, 8). The independent activity and physical activity levels of children in outdoor public activity spaces have decreased sharply in many countries (9–11). However, childhood obesity, cardiovascular disease, and psychological disease have increased significantly each year (12). A lack of physical activity is one of the leading causes of children's health problems. Health environment research has a long history (13, 14). In recent years, the neighborhood environment's impact on health, which is a microspatial scale effect, has received little attention (15, 16). Neighborhood space, as the closest to life space category in residents' daily lives, is also the primary place for children's daily activities, and thus the neighborhood space has a broad impact on children's physical and mental health (17, 18). According to the theory of children's ability development, Woolley defined the developmental themes of children's activity space as “environmental,” “physical logical,” “social,” “creative,” and “educational.” In outdoor activity spaces, children's social, emotional, cognitive, and mental health development can be promoted through game activities (19–22).

The opportunity to promote physical activity in a neighborhood environment means creating the environment. Through environmental construction, mobility can be reduced to promote deep-seated interaction and communication. The environmental perception is people's subjective feelings and psychological judgements of the surrounding environment and its changes and is the psychological basis of people's environmental behavior. Only through the cognitive environment can human beings guide their behavior through the environment. Children generate information via landscape stimulation through perception, generate cognition, and form a corresponding emotional reflection, which will affect the degree of engagement of children in physical activities. It is essential to understand the relationship between the neighborhood environment, children's physical activity, and their growth and development. The rationality and scientificity of neighborhood environmental activity space planning and design from children groups' perspectives can effectively promote children's physical activity. They will affect children's behavioral mode and health status in the future (23, 24), which are very important for their healthy growth.

With the rapid development of urbanization, urban construction has improved rapidly. Nevertheless, the development of children's playgrounds is relatively backward, and they are not adequately planned and allocated, reflecting the contradiction between children's needs and the urban development. The allocation of public resources in a fair and just society must be based on maximizing the interests of the weakest. As the lowest level of many groups, children should be the group that the government pays the most attention to when formulating public policies (25). Children's playground design tends to be instrumental and indoor as a socially vulnerable group due to their fundamental demands that are not easy to express (26, 27). For children, the urban outdoor activity spaces are hugely compressed. As children interact most closely, the physical activity status of urban neighborhood spaces has become an urgent research topic (28). To address the particularities of children groups, the security problems and responsibility of children's playgrounds are also reasons that children's playgrounds excessively rely on finished game facilities. Moreover, the spatial environment around children's residences is incredibly closely related to children's physical activity (29, 30), and the global positioning system shows that 63% of children's physical activity is near their residences (31). It has been shown that the community neighborhood space environment is the most essential outdoor activity space for children, and the space's environmental quality has also become the most critical factor affecting children's physical activity (32). Besides, Western countries mainly focus on single-factor investigations from the perspective of hygiene, focusing on children's health and physical activity levels.

This study was conducted to investigate the physical activities of children in the neighborhood space. Starting with the social attributes of children, this paper analyses the correlation between children's physical activity types and the spatial factors in their neighborhood and environmental factors to explore the needs of children's activities for the spatial environment.

Therefore, based on the theory of children's psychological cognitive development, the relationship between the urban neighborhood space environment and children's physical activity is quantified. Specifically, our aim is to explore the influence of the neighborhood space and children's physical activity from a microdesign perspective by quantifying the physical activities of children in neighborhood spaces.

In this work, we ask the following research questions:

Research question 1 (RQ1): Does the difference in children's ages affect the duration and intensity of physical activity in urban neighborhood spaces?

Research question 2 (RQ2): Among the spatial characteristics and environmental characteristics of urban neighborhoods, such as vegetation, are there relevant factors affecting the duration and intensity of children's physical activity? What factors are related to the duration and intensity of children's physical activity, and which factor has the most significant impact on the factors affecting the duration and intensity of physical activity?

Research question 3 (RQ3): Does the type of physical activity in children affect the conclusions already observed?

In domestic research, a “neighborhood” has no clear regional boundary in terms of spatial elements, so it usually refers to a neighborhood space defined by the community's administrative division. In the investigation and visiting process, it was found that the residents of each community do not flow frequently, and most of the activities are concentrated in the residential area. Therefore, compared with the community, the residential area is more in line with the concept of a “neighborhood” (15). In this study, the residential area is taken as the spatial unit of neighborhood research, and six residential areas of the Changchun and Technological Development Zone are selected as the research objects, as shown in Figure 1. They are the following: Fulin Jiayuan, Sade Xinyuan, Dongfang Wandacheng, Linhe Fengjing, Tiandi Shierfang, and Beihai Lijing. There are many residents and children here, and the residential area was built at an exact time. It has social and economic characteristics, reflecting the physical space environment surrounded by urbanization (28). Therefore, the research will help to obtain universal research results.

Through field visits, the spatial notation method (33, 34) was used to observe the situation and form of children's physical activity in the neighborhood environment activity spaces, and the assignment method was adopted to assess the intensity of physical activity. First, children's activity intensity was divided into five levels: low, lower, medium, higher, and high. The values ranged from 1 to 5 (35) from low to high, respectively. The average value of children's physical activity intensity indicated that children were living. All types of activities occur in busy times. This value is relative. The higher the value is, the higher the intensity of the physical activity. Second, a questionnaire was designed to investigate the types and characteristics of children's physical activity in the study area, and the Woolley and Lowe assessment tool was used to evaluate the spatial characteristics and environmental characteristics of the neighborhood outdoor space (37). Based on the concept of children's activity game value and the research from many fields, the British researcher Woolley (38) proposed corresponding evaluation tools based on the relationship between children's space design and the activity value.

In the preliminary survey, it was found that most of the children who play independently on outdoor playgrounds do so most often on weekends. Therefore, this survey focuses on the weekend. During this period, there were large numbers of children and sufficient samples. After asking parents' permission and the child's consent we started these research activities. We explained our organization and identity to the interviewees (certificates and letters of introduction issued by the school), and ensured that all the information of the interviewees would only be used for this academic research and would never be disclosed through any means which made the interviewees fully trust our research team and then they authorized the research. Besides, fill in the questionnaire. We explained the reason and purpose of our research which aimed at exploring the influence of environmental and space on children's activities. Meanwhile, only one respondent was surveyed to elaborate and explain the problem. Therefore, both the children themselves and their guardians are willing to provide information, and the respondents' confirmation of the authorization of information is included in each questionnaire. During the questionnaire distribution, we distributed questionnaires one by one, filled them out, collected them, and then issued the next questionnaire which needed a number of volunteers conducting research together. In this way, the recovery rate of the questionnaire is guaranteed. At the same time, if the recruiters do not understand the contents of the questionnaire when filling in the questionnaire, the volunteers can give immediate and timely reply, which ensures the efficiency of the questionnaire. A total of 510 questionnaires were distributed, and 500 were recovered. Of these 500 questionnaires, which 498 were valid, and the effective response rate was 97%. The questionnaire content involves children's age, time, frequency, activity type, and evaluation of the spatial and environmental characteristics of children's activities in residential areas.

Due to children's limited cognitive ability, only 4- to 15-year-old children were investigated and divided into three age groups: 4–7, 8–11, and 12–15 years old. The selection of the children as the research objects is based on the following two reasons: (1) According to the cognitive development theory of child psychologist Jean Piaget (36), the developmental concept of the interaction between children's psychological development and environment (37) defines this as appropriate, and children's physical and mental characteristics are shown in Table 1. (2) Four- to 15-year-old children have relatively healthy independence, and they have more opportunities and types of physical activities in which to participate. Game activities are the main activities of children in the age group, and they have a clear image and initiative in the process of playing (26). The diversity of activity types is more abundant, they can express their wishes, and the influence of guardians on children's activities is small (39). Children aged 8–11 and 12–15 were interviewed face-to-face, and questionnaires were used. Parents or child caregivers completed the questionnaires reviewing the neighborhood space's physical activities for the children aged 4–7.

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 20.0) was used to process the data to analyse the validity and reliability of urban neighborhood spatial environmental activities. The factors involved in the questionnaire were standardized with SPSS 20.0, and then reliability analysis was conducted. Reliability analysis was used to study the reliability and accuracy of quantitative data. When analyzing the α coefficient of the questionnaire (Cronbach's α coefficient), if this value is higher than 0.8, it indicates high reliability. The Cronbach's α coefficient of this study is 0.841. The KMO and Bartlett test are used to verify the validity. The KMO is 0.801 and >0.8. Thus, the validity of the research data is excellent. Therefore, it can be inferred that the questionnaire's validity and reliability are promising, indicating that the data are real and practical.

As shown in Table 2, regarding age, the age frequency distributions of the three sample groups are not significantly different, which shows that the age distribution of children in urban neighborhood space activities is relatively uniform. Nearly one-third of the children in the sample had an activity duration of “more than 90 min,” accounting for 29.80% of the total. In terms of physical activity intensity, 61.20% of children's activity intensity was at high and medium-high levels. Furthermore, 39.00% of the activity time was in the “afternoon.” Besides, the proportion of evening samples was 38.20%, and more than half of the activity time was in the afternoon and evening. Additionally, the types of children's physical activities were statistically analyzed, as shown in Figure 2. We found that in the neighborhood space, the activity frequency of kicking a ball was the highest. The frequency of slide activity was the lowest; and the frequencies of rock climbing, swinging, playing hide and seek, painting, skateboarding, cycling, and the five other types of activities were not significantly different.

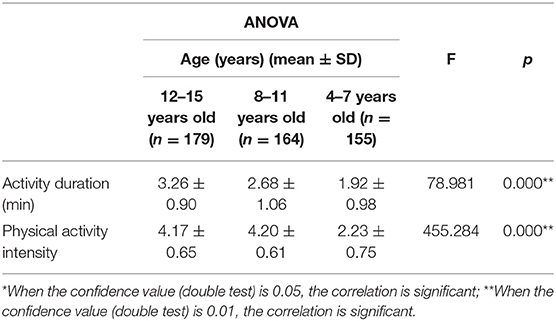

In this section, we review the research issues. Analysis of variance (single-factor analysis of variance) was used to study the difference between children's age and the duration and intensity of physical activity. Therefore, we can answer research question 1 (RQ1). Table 3 shows that different age samples have a significant effect on the duration and intensity of physical activity (p < 0.05), which means that different age samples have significant effects on the different times and intensities of physical activity.

Table 3. Analysis of variance between the duration of children's physical activity and children's age.

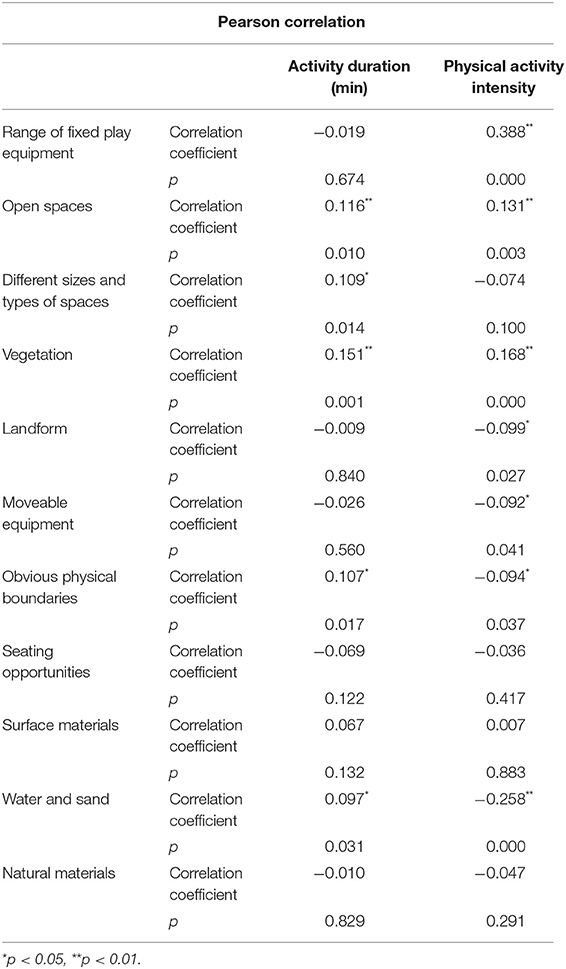

To answer research question 2, we calculated the correlations of the time and intensity of physical activity and the relationship between the intensity and the surrounding spatial environment. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the correlation. Table 4 shows the results for the length of children's activities and the open space, different scales and types of space, vegetation, and the spatial characteristics of children's activities. There is a positive correlation between the physical boundary, and playable water and sand at a site. The physical activity intensity of children shows a negative correlation with the terrain, movable materials, the physical boundary of the site, and playable water and sand, which shows that these factors limit children's medium- and high-strength physical activities.

Table 4. Correlation analysis of the duration and intensity of children's physical activity and neighborhood spatial factors.

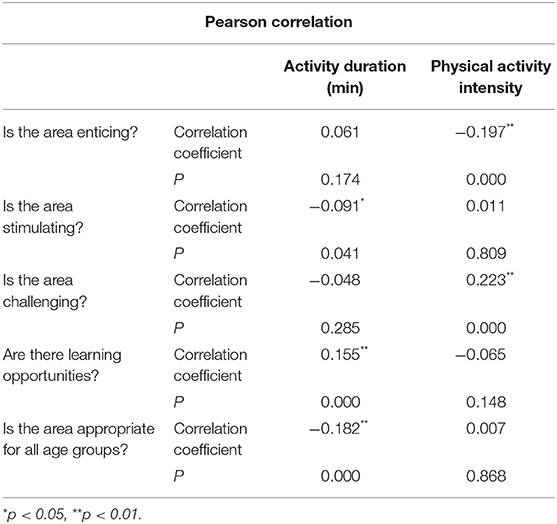

The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to identify the strength of the correlation relationship between children's physical activity time and the neighborhood environment, as shown in Table 5. Among the factors related to children's physical activity time and the neighborhood environment, physical activity time was significantly negatively correlated with whether visual stimulation was used and whether education and learning opportunities were provided. This is a different answer to research question 2 (RQ2). Regarding the intensity of physical activity, whether the environment is challenging has a positive correlation and whether the space is attractive has a negative correlation with the intensity of activity.

Table 5. Correlation analysis of the duration and intensity of children's physical activity and neighborhood environmental factors.

Research question 3 (RQ3) questioned whether the type of physical activity would affect the duration and intensity of physical activity. As shown in Table 6, we analyzed the correlation between 14 types of children's physical activity. (1) The length of children's activities has a significant positive correlation with the types of activities, such as adventuring, performing programmes, and painting; and a negative correlation with the types of activities such as standing, sitting, and playing in a sandpit. (2) As for the intensity of the physical activity, it was negatively correlated with activities such as standing, sitting and playing in a sandpit and was positively correlated with cycling, playing football, playing hide and seek, exploring, giving performances, painting, rough-and-tumble, rock climbing, skateboarding, etc. Besides, we add that there is a significant positive correlation between children's age and swinging, sliding, cycling, playing hide-and-seek, exploring, playing in a sandpit, skateboarding, and other activities and negatively correlated with giving performances, painting, rock climbing, rough-and-tumble, and other activities.

The types of children's physical activity are relatively diverse. Referring to the theory of availability and the description of children's physical game classification by Fjørtoft (3), the 14 types of children's physical activity are divided into four types: passive, physical, constructive and symbolic. They are shown in Table 7.

As shown in Table 8, correlation analysis was used to study age; activity duration and intensity; and the passive, athletic, and imaginative types. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to measure the strength of the correlation. The results showed that (1) there was a significant positive correlation between children's age and sports activities and a significant negative correlation between children's age and imaginative and constructive activities. (2) There was a significant positive correlation between physical activity and motor and imaginative activities and a significant negative correlation between the durations of physical activity and passive activity. (3) There is a positive correlation between the intensity of physical activity and the type of exercise and imagination. There is a significant negative correlation between the intensity of physical activity and the passive type and the construction type.

In previous research, we also studied the correlation between urban outdoor space and children's emotional and physical activities (11). The fairness of urban built-up environments for children is not high. The care given to children is insufficient (40). This study's main purpose is to explore the relationship between the spatial environment of the urban neighborhood and children's physical activity. The research shows that the relationship between the neighborhood's spatial characteristics and the physical activity of children can be evaluated following Woolley and Lowe. However, the evaluation results of the Woolley and Lowe assessment tool can objectively reflect the relationship between children's activities and space and show that there is a significant correlation between them. The results show a positive correlation between sports and constructive activities and children's age while there is a negative correlation between passive activities and the duration of children's activity. In terms of the duration and type of physical activity of children, the diversity of the spatial environment and spatial factors in urban residential areas promotes children's physical activity level. Simultaneously, it also provides more opportunities for children to choose their own preferred and suitable physical activities, enhances children's interest in activities, and reduces the possibility of children participating in passive physical activities (41). Besides, the influences of vegetation and the development space's elements on children's physical activity time are the most and second most important characteristics of neighborhood space; therefore, it is particularly important to ensure the equalization of children's activity space and green space vegetation in neighborhood space.

Since children's activity space tends to be a kit, fenced in, or PET, the excessive artificial design and uniform equipment and facilities in the activity field lack consideration of children's needs, limiting the level of children's outdoor physical activity. Therefore, the goal of the equalization of neighborhood space is to meet children's activities, emotional communication, physical development, etc. From the microdesign point of view, different from the previous study on whether the urban residential neighborhood space is child-oriented that showed that the main criteria include accessibility, safety, and employability (42), this study explored and analyzed the relationship among children's physical activity, spatial environmental factors, and children's physical activity types based on the spatial characteristics, environmental characteristics, and types of children's physical activity in an urban neighborhood. The diversity of neighborhood space environmental factors has a positive impact on the duration of children's physical activity, improving the quality of children's physical activity and allowing children to acquire the five abilities of “physical,” “social,” “emotional,” “creative” and “challenging” at the same time (43). The diversity also enables children to obtain pleasant feelings and rich experiences through physical activities, thus improving children's activities in the neighborhood space environment (43). In previous studies, we also confirmed that natural materials such as vegetation have a significant correlation with the duration of children's activity in the spatial environment. They can promote the duration of and intensity children's physical activity, and children with longer outdoor activity times have higher cardiopulmonary fitness (44) and better children's physical and mental health development (45, 46). However, there are few children's activity places with natural materials in the urban neighborhood space, which shows a significant deviation between children's own needs, the actual construction of the city and the habitual neglect and deprivation of children's rights (25).

Neighborhood space and its environmental elements play potential roles in children's activities, growth, and development. Based on the theory of mind (TOM) (47, 48), we can exchange our ideas, goals, and desires with others in activities and promote children's ability to make friends and socialize. Creating ambiguity in the spatial environment will enable children to explore more (49), which is the site's physical boundary index mentioned in the Woolley and Lowe evaluation tool. Therefore, the construction and design of children's outdoor space activity places need to consider children's unique attributes. Based on the interdisciplinary theories of children's psychology, environmental behavior, cognitive science, and development psychology (36), the national government should promote children-based policies and improve the construction of public space for children.

Based on the main relationship between the spatial environment and children's activity level, the results for the urban neighborhood spaces of other cities may be different due to economic and regional differences. Besides, most of the current relevant research on children's outdoor space design results from the perspective of children's psychological and physiological needs explores children's space needs at different ages and children's behavior development in different spaces while the research on activity intensity is relatively limited. It is hoped that our research can be used deeply explore the level of physical activity of children of different ages in different cities. This study is based on field surveys, questionnaire interviews, and direct observations. Although these qualitative survey data can be quantified, there is still a lack of instruments to detect the objective neighborhood space physical environment index and its impact on children's physical activity opportunities (9). Future research should be quantified using the objective indicators and the research precision and depth should be deepened.

Besides, we use Woolley & Lowe assessment tools in the environment and the space of two dimensions scores to add together in order to achieve the final evaluation score. Not only this way of statistics in statistical is easier to obtain the relationship between the two kinds of things but also the evaluation criterion that are included in the tool are applicable.It also can make more specific description for the environment and space specific, cause the angel to clearly understand of the meaning of the questionnaire, and let the results will be more credible. For the impact between the environment space and children's activities discussed in our study, it is more appropriate, and it is advantageous for the adynamic place of children and the score of value. This is of great reference significance to the establishment of evaluation criteria for the design of children's activity space. However, this evaluation tool originated in the UK, and to some extent has been influenced by the UK. If this tool is to be more widely used in the future, some evaluation criteria need to be adjusted and optimized.

The urban neighborhood space environment has an important impact on urban residents' physical and mental health, including children. This kind of neighborhood space environment in people's daily lives will affect basic well-being, such as health and safety, and the learning ability and development level of children.

In this study, the neighborhood space environment was used to explore the duration of children's physical activity, to study public space planning and design needs, and to ensure the allocation of children's activity space in the public space. Different from the traditional choice of the residential area surrounding environmental variables as the research area, we use the perspective of children to explore the impacts of the space and environment on children's physical activity and to explore the influence of several different characteristics on children's physical activity level. The aim is to shape and improve outdoor public space, create high-quality outdoor opportunities for children, make children healthier and more creative, and better integrate children into society.

First, regarding neighborhood space characteristics, vegetation landscape elements can provide visual aesthetic and interactive opportunities for children in outdoor activity spaces. There is a significant positive correlation between the duration of children's activities and the intensity of physical activities. Open space provides places for children's activities, group activities, and group activities, increasing the opportunities for children's extracurricular activities, thereby promoting children's physical activity level. Second, children's physical activity time can be prolonged by contacting the natural environment in the neighborhood space and providing children with the opportunity for operations or experimentation. Finally, regarding the types of children's activities, passive activities shorten the time of children's physical activities and limit the intensity of children's physical activities.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because we explained our institution and identity (certificate and letter of introduction issued by the University) to the interviewee. We ensured all the interviewee's information was only used for academic research and would not be disclosed in any way, which made the interviewee fully trust the research team and then authorized the research. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to MTlTMDM0MTIzQHN0dS5oaXQuZWR1LmNu.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Conceptualization: YB and MG. Methodology, writing—original draft preparation, and visualization: MG. Software, investigation, and data curation: YB. Validation and formal analysis: MG and DL. Resources and supervision: YB, XZ, and DL. Writing—review and editing: MG, XZ, and DL. Funding acquisition: DL. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 51708052) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant Number 2017M622964).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would especially like to thank the children who participated in our survey.

1. Forsyth A, Wall M, Choo T, Larson N, Van Riper D, Neumark-Sztainer D. Perceived and police-reported neighborhood crime: linkages to adolescent activity behaviors and weight status. J. Adolesc. Health. (2015) 57:222–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.05.003

2. Romero AJ. Low-income neighborhood barriers and resources for adolescents' physical activity. J. Adolesc. Health. (2005) 36:253–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.027

3. Fjørtoft I. Landscape as playscape: the effects of natural environments on children's play and motor development. Child. Youth Environ. (2004) 14:21–44. doi: 10.7721/chilyoutenvi.14.2.0021

4. Herrington S, Lesmeister C. The design of landscapes at child-care centres: seven Cs. Landsc. Res. (2006) 31:63–82. doi: 10.1080/01426390500448575

5. Wang X, Woolley H, Tang Y, Liu HY, Luo YY. Young children's and adults' perceptions of natural play spaces: a case study of Chengdu southwestern China. Cities. (2018) 72:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2017.08.011

6. Wen FH, Wang YS. Health space demand and governance strategy of child-friendly community. Beijing Plan. Rev. (2020) 3:25–9 (in Chinese).

7. Xu MY, Geyer T, Mao P, Tian T. International certification mechanism of child-friendly cities (communities) and related practices and theory development of European and American areas. Urban Plan. Int. (2020). Available online at: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.5583.TU.20200929.1818.005.html (in Chinese) (accessed January 25, 2021).

8. Shen Y, Mu XY, He L. Study on the development characteristics and re-developing direction of children's playing space in high-rise housing estate. Hum. Geogr. (2015) 30:28–33 (in Chinese). doi: 10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2015.03.005

9. Han XL, Stemudd C, Zhao WQ. Progress in the research on children's outdoor physical activity in cities. Hum. Geogr. (2011) 26:29–33 (in Chinese). doi: 10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2011.06.007

10. Bagot KL, Allen FCL, Toukhsati S. Perceived restorativeness of children's school playground environments: nature, playground features and play period experiences. J. Environ. Psychol. (2015) 41:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.11.005

11. Whitzman C. Policies and practices that promote children's independent mobility. Urban Plan. Int. (2008) 23:56–61. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-9493.2008.05.009

12. Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. (2010) 1186:125–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x

13. Miao J, Wu XG. Urbanization, socioeconomic status and health disparity in China. Health Place. (2016) 42:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.09.008

14. Gostin LO, Hodge JG, Bloom BR, El-Mohandes A, Fielding J, Hotez P, et al. The public health crisis of underimmunisation: a global plan of action. Lancet Infect. Dis. (2020) 20:e11–6. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30558-4

15. Zhang SY, Lin SN, Li ZG, Guo Y. Influence of neighborhood environmental perception on self-rated health of residents in cities of China: a case study of Wuhan. Hum. Geogr. (2019) 34:32–40 (in Chinese). doi: 10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2019.02.005

16. Shi MJ. The research review and its implications of neighborhood effects in Euramerican cities. Urban Plan. Int. (2017) 32:42–8 (in Chinese). doi: 10.22217/upi.2017.108

17. Piccininni C, Michaelson V, Janssen I, Pickett W. Outdoor play and nature connectedness as potential correlates of internalized mental health symptoms among Canadian adolescents. Prev. Med. (2018) 112:168–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.04.020

18. Barton J, Bragg R, Pretty J, Roberts J, Wood C. The wilderness expedition: an effective life course intervention to improve young people's well-being and connectedness to nature. J. Exp. Educ. (2016) 39:59–72. doi: 10.1177/1053825915626933

19. Hillman CH, Pontifex MB, Castelli DM, Khan NA, Raine LB, Scudder MR, et al. Effects of the FITKids randomized controlled trial on executive control and brain function. Pediatrics. (2014) 134:e1063–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3219

20. Chen A. Top 10 research questions related to children physical activity motivation. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. (2013) 84:441–7. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2013.844030

21. Cleland V, Crawford D, Baur LA, Hume C, Timperio A, Salmon J. A prospective examination of children's time spent outdoors, objectively measured physical activity and overweight. Int. J. Obes. (2008) 32:1685–93. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.171

22. McCurdy LE, Winterbottom KE, Mehta SS, Roberts JR. Using nature and outdoor activity to improve children's health. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care. (2010) 40:102–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.02.003

23. Wickel EE, Belton S. School's out… now what? Objective estimates of afterschool sedentary time and physical activity from childhood to adolescence. J. Sci. Med. Sport. (2016) 19:654–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.09.001

24. Yang X, Telama R, Hirvensalo M, Tammelin T, Viikari JS, Raitakari OT. Active commuting from youth to adulthood and as a predictor of physical activity in early midlife: the Young Finns Study. Prev. Med. (2014) 59:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.019

25. Peng WJ, Tian L, Xiao J, Wang YY. Child's infrastructure in cities—urban planning and design to guarantee child rights. Landsc. Arch. Front. (2020) 8:100–9 (in Chinese). doi: 10.15302/J-LAF-1-030012

26. Luo Y, Wang X. Research on children playground of natural style in urban outdoor space based on landscape perception. Landsc. Arch. (2017) 3:73–8 (in Chinese). doi: 10.14085/j.fjyl.2017.03.0073.06

28. Wang D, Han XL. Children's outdoor physical activities in Beijing urban-village neighborhood subjected to environmental factors: a case study on Dayouzhuang and Saoziying Neighborhood. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pek. (2012) 48:841–7 (in Chinese). doi: 10.13209/j.0479-8023.2012.109

29. Renalds A, Smith TH, Hale PJ. A systematic review of built environment and health. Fam. Commun. Health. (2010) 33:68–78. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181c4e2e5

30. De Vet E, De Ridder DTD, De Wit JBF. Environmental correlates of physical activity and dietary behaviours among young people: a systematic review of reviews. Obes Rev. (2011) 12:e130–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00784.x

31. Jones AP, Coombes EG, Griffin SJ, Van Sluijs EMF. Environmental supportiveness for physical activity in English schoolchildren: a study using global positioning systems. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. (2009) 6:42. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-42

32. A LT, Han XL. The Impact of the outdoor environment of the traditional community on children's physical activities: a case study of the unit community of Beijing Institution of Nuclear Environment (BINE). J. Hum. Settl. West China. (2015) 30:64–7 (in Chinese). doi: 10.13791/j.cnki.hsfwest.20150614

33. Little S. Engaging youth in placemaking: modified behavior mapping. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. (2020) 17:6527. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186527

34. Wang XX, Wu CZ. An observational study of park attributes and physical activity in neighborhood parks of Shanghai, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. (2020) 17:2080. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17062080

35. Han J, Ye CK, Han XL. The impact of neighborhood space in traditional residential on childrens' perception and physical activities: a case study in Zhonglouwan Neighborhood. Urban Stud. (2013) 20:1–4 (in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-3862.2013.05.024

36. Huitt W, Hummel J. Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development: Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University (2003).

37. Wang X, Woolley H, Zhang J, Liu XY, Wang QN. Scientific exploration of outdoor children's play space design: Woolley & Lowe evaluation tool and its application. Chin. Landsc. Arch. (2020) 36:86–91 (in Chinese). doi: 10.19775/j.cla.2020.03.0086

38. Woolley H, Lowe A. Exploring the relationship between design approach and play value of outdoor play spaces. Landsc. Res. (2013) 38:53–74. doi: 10.1080/01426397.2011.640432

40. Ding Y. The research of children's interest and urban planning's basic values. Urban Plan. Forum. (2009) 7:177–81 (in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3363.2009.z1.039

41. Wang XT, Han XL. Impact of diverse environmental factors on children's physical activity in playgrounds. J. Hum. Settl. West China. (2018) 33:100–5 (in Chinese). doi: 10.13791/j.cnki.hsfwest.20180616

42. Ziviani J, Wadley D, Ward H, Macdonald D, Jenkins D, Rodger S. A place to play: socioeconomic and spatial factors in children's physical activity. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. (2008) 55:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2006.00646.x

43. Senda M. What is a good environment for children's growth. Landsc. Arch. (2012) 3:148–51 (in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-1530.2012.03.027

44. Schaefer L, Plotnikoff RC, Majumdar SR, Mollard R, Woo M, Sadman R, et al. Outdoor time is associated with physical activity, sedentary time, and cardiorespiratory fitness in youth. J. Pediatr. (2014) 165:516–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.05.029

45. Mavoa S, Lucassen M, Denny S, Utter J, Clark T, Smith M. Natural neighbourhood environments and the emotional health of urban New Zealand adolescents. Landsc. Urban Plan. (2019) 191:103638. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103638

46. World Health Organization. The Health and Social Effects of Nonmedical Cannabis Use. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016).

47. Goldstein TR, Winner E. Engagement in role play, pretense, and acting classes predict advanced theory of mind skill in middle childhood. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. (2011) 30:249–58. doi: 10.2190/IC.30.3.c

48. Qu L, Shen PX, Chee YY, Chen LX. Teachers' theory-of-mind coaching and children's executive function predict the training effect of sociodramatic play on children's theory of mind. Soc. Dev. (2015) 24:716–33. doi: 10.1111/sode.12116

Keywords: children, physical activity, environmental characteristics, spatial characteristics, neighborhood space

Citation: Bao Y, Gao M, Luo D and Zhou X (2021) Effects of Children's Outdoor Physical Activity in the Urban Neighborhood Activity Space Environment. Front. Public Health 9:631492. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.631492

Received: 20 November 2020; Accepted: 13 January 2021;

Published: 15 February 2021.

Edited by:

Patrick De Boever, University of Antwerp, BelgiumReviewed by:

David Mulenga, Copperbelt University, ZambiaCopyright © 2021 Bao, Gao, Luo and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dan Luo, bHVvZGFuQGNxdS5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.