- 1Department of Public Health, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, United States

- 2Department of Human Development and Family Science, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, United States

- 3Department of Health Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, United States

- 4School of Social Work, University of Missouri St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 5Health Sciences Library, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, United States

Trans and gender non-conforming (TGNC) people experience poor health care and health outcomes. We conducted a qualitative scoping review of studies addressing TGNC people's experiences receiving physical health care to inform research and practice solutions. A systematic search resulted in 35 qualitative studies for analysis. Studies included 1,607 TGNC participants, ages 16–64 years. Analytic methods included mostly interviews and focus groups; the most common analysis strategy was theme analysis. Key themes in findings were patient challenges, needs, and strengths. Challenges dominated findings and could be summarized by lack of provider knowledge and sensitivity and financial and insurance barriers, which hurt TGNC people's health. Future qualitative research should explore the experiences of diverse and specific groups of TGNC people (youth, non-binary, racial/ethnic minority), include community-based methods, and theory development. Practice-wise, training for providers and skills and support for TGNC people to advocate to improve their health, are required.

Current research highlights the critical need to address health disparities and improve health outcomes among individuals who identify as transgender (1, 2). Transgender (trans) is an umbrella term for people whose gender identity, gender expression, or behavior does not conform to that typically associated with the sex to which they were assigned at birth (3). The term includes people who identify as gender non-conforming, a term that generally refers to people who do not adhere to the binary (e.g., male/female) concept of gender (3).

Trans and gender non-conforming (TGNC) people report many health disparities. For instance, discrimination and minority stress contribute to higher rates of poor mental health outcomes among TGNC people (4). These outcomes include, but are not limited to, depression (5–7), anxiety (5, 6), and suicide attempts (5, 7, 8). Trans women report much higher rates of HIV than the general population (9). Additionally, when compared to their cisgender counterparts, TGNC people report higher rates of disordered eating (5), smoking, obesity, and poor self-rated physical and mental health (10).

TGNC individuals are a vulnerable population due to the societal stigma associated with their identity (11), but they also experience unique hurdles to accessing quality healthcare. Despite the well-documented health disparities among TGNC individuals, research in this area is relatively new and only gained significance in the last decade (12). As understanding of the TGNC population and their health needs has increased, the community, itself, has changed to include more diverse identities and experience of gender (13). Many binary and non-binary TGNC individuals seek medical care to support physical changes that align with their gender identity (e.g., hormone therapy, surgery), increasing the importance of healthcare in the experience of being TGNC. However, given that transgender medicine is still a new area, many medical providers have received limited or no training in how to work with TGNC patients, and some hold biases associated with the binary approach to sex present in medicine (14). As a result of this, TGNC individuals may experience negative experiences in healthcare, not only as a result of societal stigma, but also due to competency issues among providers.

The most recent U.S. Transgender Survey indicated that TGNC people are also less likely to be insured than the general population and that notable numbers of trans people report negative health experiences (33%) or avoiding medical care (25%) (15). Relatedly, Edmiston et al. (1) reported that TGNC people are also less likely to access preventative health screenings. Lerner and Robles (16) identified discrimination from health care providers as a central cause of the underutilization of health care. Improving quality health care experiences for TGNC people, offers an opportunity to improve health outcomes, via enhanced care and decreased distress. We conducted a qualitative scoping review of studies addressing TGNC people's experiences receiving physical health care to implement more responsive TGNC care and improve trans health outcomes.

Prior reviews have begun to organize findings about TGNC health and health care. A recent review addressed TGNC persons' mental health care experiences (4). Cicero et al. (17) reviewed studies of transgender health care experiences to contextualize them within the Gender Affirmation Framework, categorizing health care experiences into social, medical, legal, and psychological barriers. Heng et al. (18) conducted a review of transgender people's general health care experiences—excluding specific health concerns like emergency care or HIV care.

The field of trans health is an emerging yet under researched area. Understanding current experiences is critical both for informing future healthcare research and adding to the literature needed to improve healthcare education. This analysis builds on prior reviews, to identify how to improve care and outcomes for TGNC people. First, the following analysis focuses exclusively on qualitative research and includes a quality assessment of the research using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ), a 32-item checklist for comprehensive reporting of qualitative studies (19). Qualitative research is well-suited to capture the nuances of patient experiences and needs (20). Assessing the quality of the research allows us to make recommendations for future qualitative directions and contributions in this field. Second, we also use theory-generating qualitative meta-synthesis methods (21). This approach provides a scoping summary of existing findings, and also cultivates generalizable theory pertaining to the research question. Third, we address all areas of physical health and do not exclude specific health concerns, such as HIV, to create a full picture of physical health that includes: challenges faced by TGNC people with health care providers and in health care systems.

Materials and Methods

Scoping Review

Our review was guided by five processes: (a) identify the research question driving the review, (b) identify relevant studies, (c) select studies, (d) extract data for selected categories, (e) analyze and synthesize findings, (f) and report data (21, 22). This study was approved by the primary author's institutional review board.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

To meet inclusion criteria, articles had to be peer reviewed, written in English and based on research studies that took place in the U.S. between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2018. Other criteria included: the use of qualitative methods or inclusion of text, narratives, images, or artifacts as data; study samples with at least 50% trans men and/or trans women and/or gender non-conforming individuals who were represented in the findings; and the description of physical health care experiences with providers or physical health care as a major finding in the study. Methods articles, theoretical articles, presentations, and government and non-government reports were excluded.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were created to meet our scoping review goals. We chose to limit our analysis to studies in the U.S., because personal, familial, legal, and social experiences of TGNC people differ greatly across cultures. These differences influence medical encounters for TGNC patients and our ability to integrate findings of those encounters meaningfully into U.S. findings. We limited the studies in this review to those that included at least 50% TGNC to ensure their representation in LGBT studies beyond the listing of the T in the acronym alone. Similarly, we limited our sample to studies with at least one theme addressing health care or provider experiences to ensure that these types of findings were adequately represented in the studies. We focused our review on physical health experiences because a recent review of mental health care experiences exists (4); and mental health often requires different approaches, interactions, and treatments than physical health experiences to be combined meaningfully in an analysis of physical health interactions.

Search Procedures

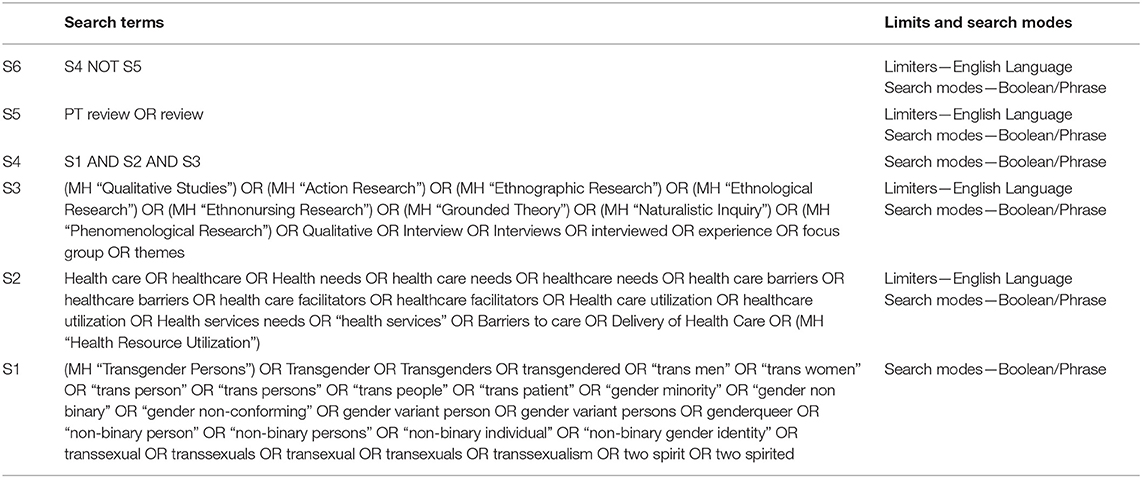

The 5th author, in consultation with the first and third authors, created a search strategy. The base search strategy was constructed by an analysis of key terms in MeSH, and from relevant articles in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL (see Table 1). The following databases were searched: EMBASE (Ovid), PubMed, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Web of Sciences, CAB Direct, Gender Watch (ProQuest), and PsycINFO (EBSCOhost). All searches were run in May, 2019, and the base search was adapted to each database.

Screening and Study Selection

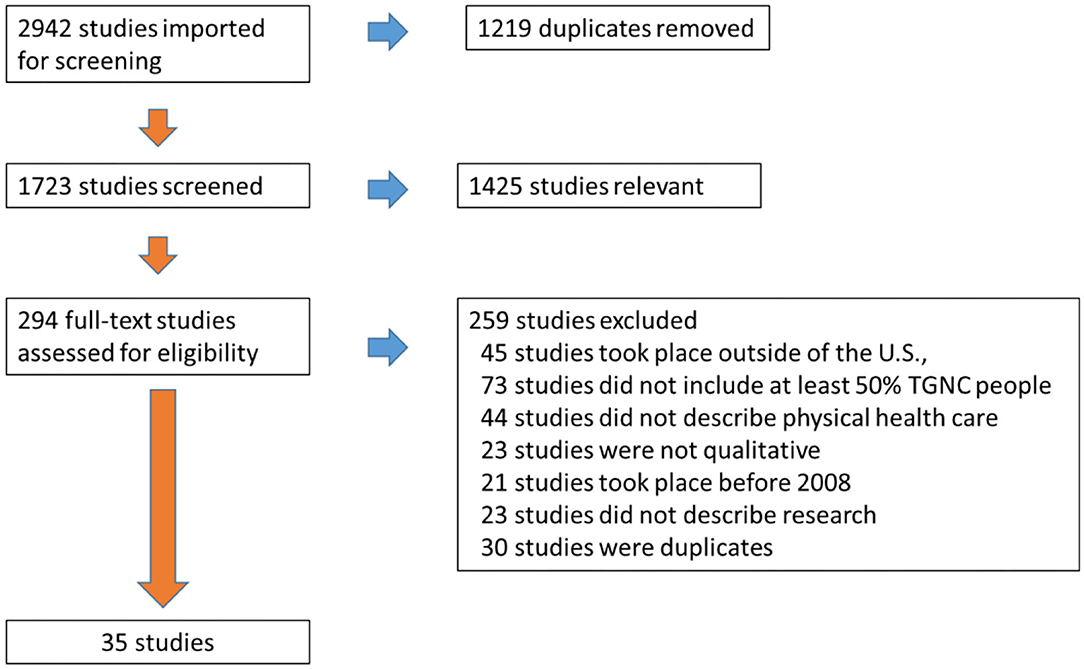

The search identified a total of 2,942 citations. First, 1,219 duplicates were removed, leaving a total of 1,723 studies to be screened. The first four authors reviewed every title and abstract, performed the abstract review process, and reached consensus regarding articles relevant for further consideration (n = 294 articles). Two independent reviewers then read each full text article (n = 294) and used a screening form to verify inclusion criteria for each article. The reviewers then discussed each full text article that was being considered for inclusion. If there was discordance between the article and the inclusion criteria, the two reviewers presented the article to a third independent reviewer. Discussions ensued between all three reviewers until agreement occurred. At this point 259 articles were excluded for not meeting screening criteria: 45 studies took place outside of the U.S., 73 studies did not include at least 50% TGNC people, 44 studies did not describe physical health care, 23 studies were not qualitative, 21 studies took place before 2008, 23 studies did not describe research, and 30 studies were duplicates. As a result, 35 studies were retained for analysis. The screening and selection process was depicted using the PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1.

Analysis

Analysis included collating important summary items to describe the depth and breadth of the articles, assessing article quality, and identifying key themes in the study results (21, 22). We extracted the following categories of data: inclusion criteria, sample size, key demographics (ethnicity, income, and gender), aim, recruitment settings, methods, analysis strategies, and findings. We extracted these categories of data to provide study overviews, support COREQ scoring, and facilitate theory development.

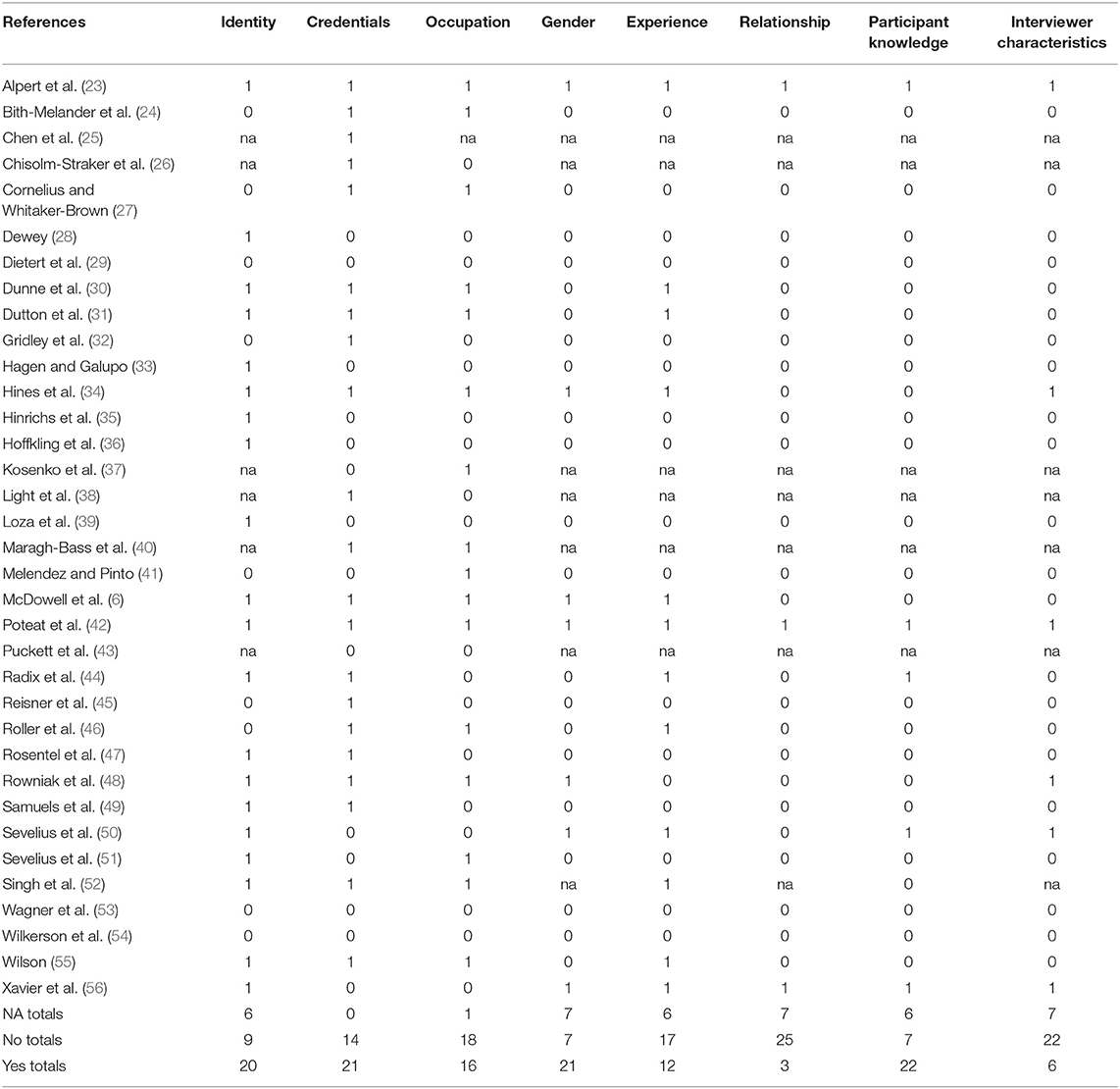

Quality of the articles was evaluated with the COREQ (19). COREQ items are grouped into three domains: research team and reflexivity, study design, and data analysis and reporting. Domain 1 addresses characteristics of the interviewer and the interviewer relationship with the participants with questions about interviewer credentials and how well the interviewer and participant know each other (eight items). Domain 2 addresses theoretical framework, participant selection, sample size, and data collection (15 items). Questions focus on where the data was collected and what the sample looks like. Domain 3 addresses data analysis and reporting (nine items) via explanations of themes and how participant quotes and input are integrated into the publication. We pilot-tested the COREQ with four articles, in which the first four authors reviewed their responses and discussed discrepancies until they were eliminated. At least two authors systematically reviewed each article by extracting all text related to the above categories, resolving any discrepancies, and producing a detailed data matrix that described basic components of the studies.

Data were then analyzed for the purpose of identifying generalizable themes and constructs that communicate transgender healthcare experiences within a working theoretical model (21). This process was described in detail along with the findings in the results section.

Synthesis

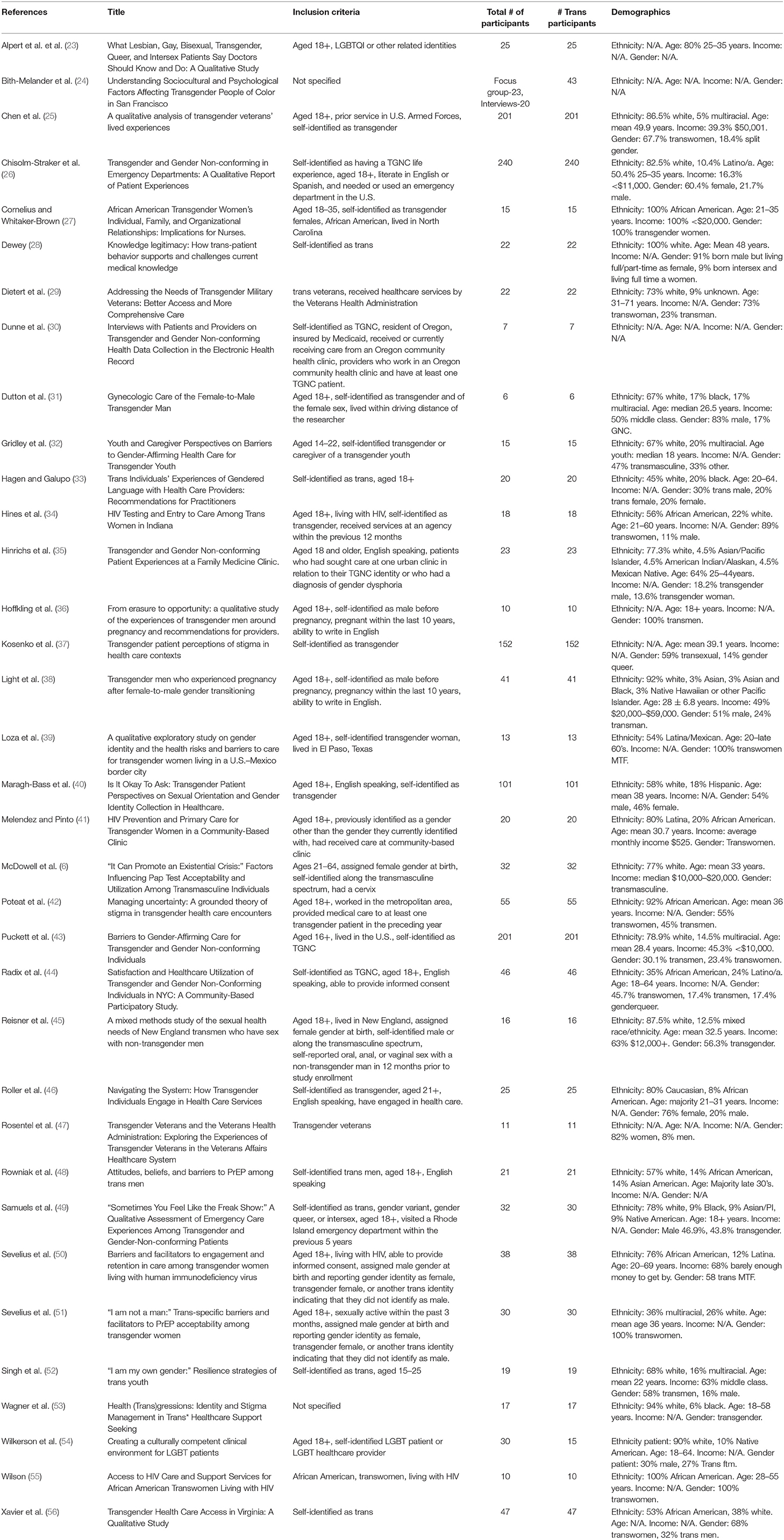

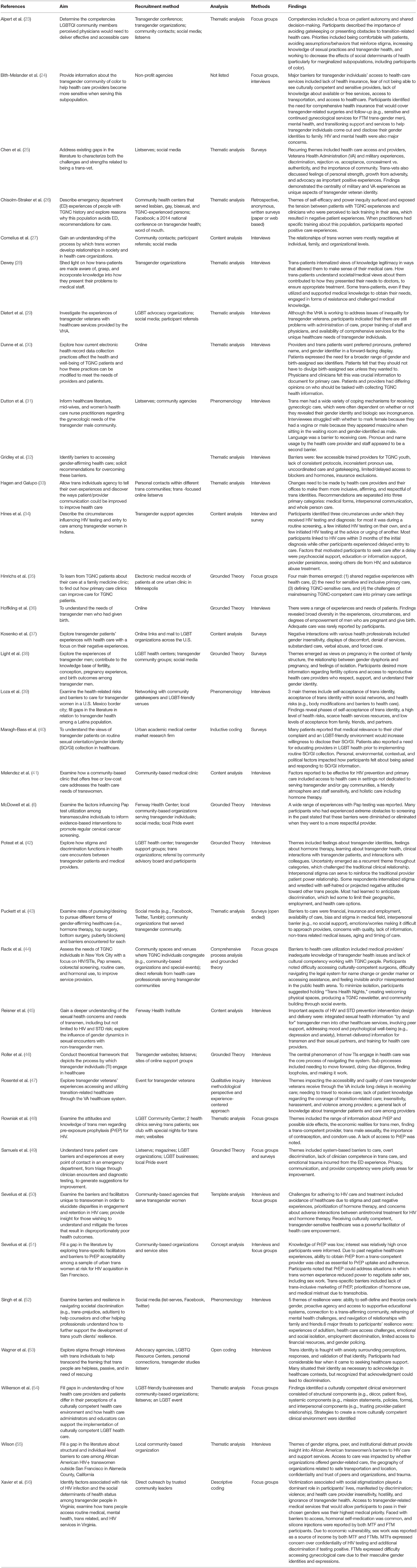

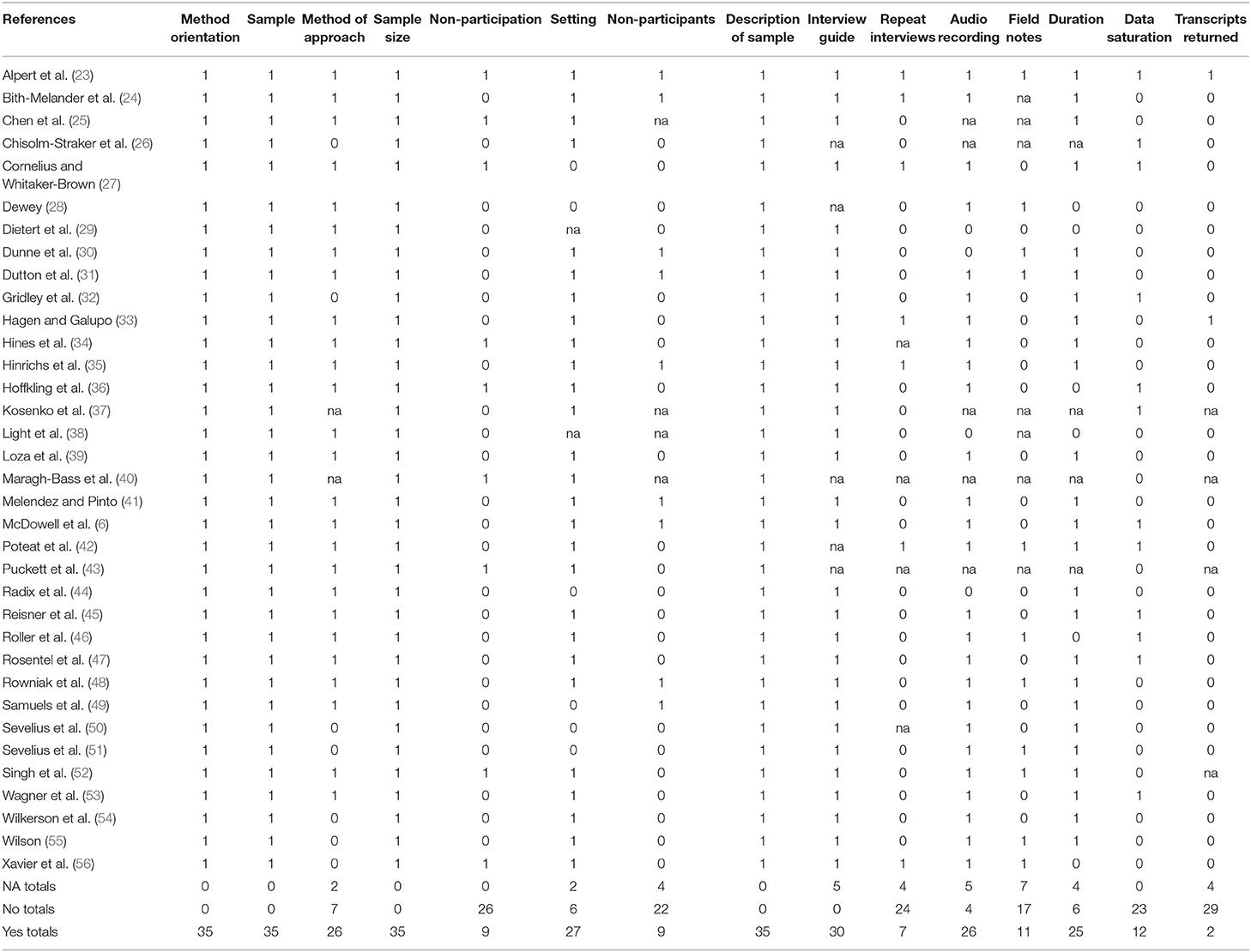

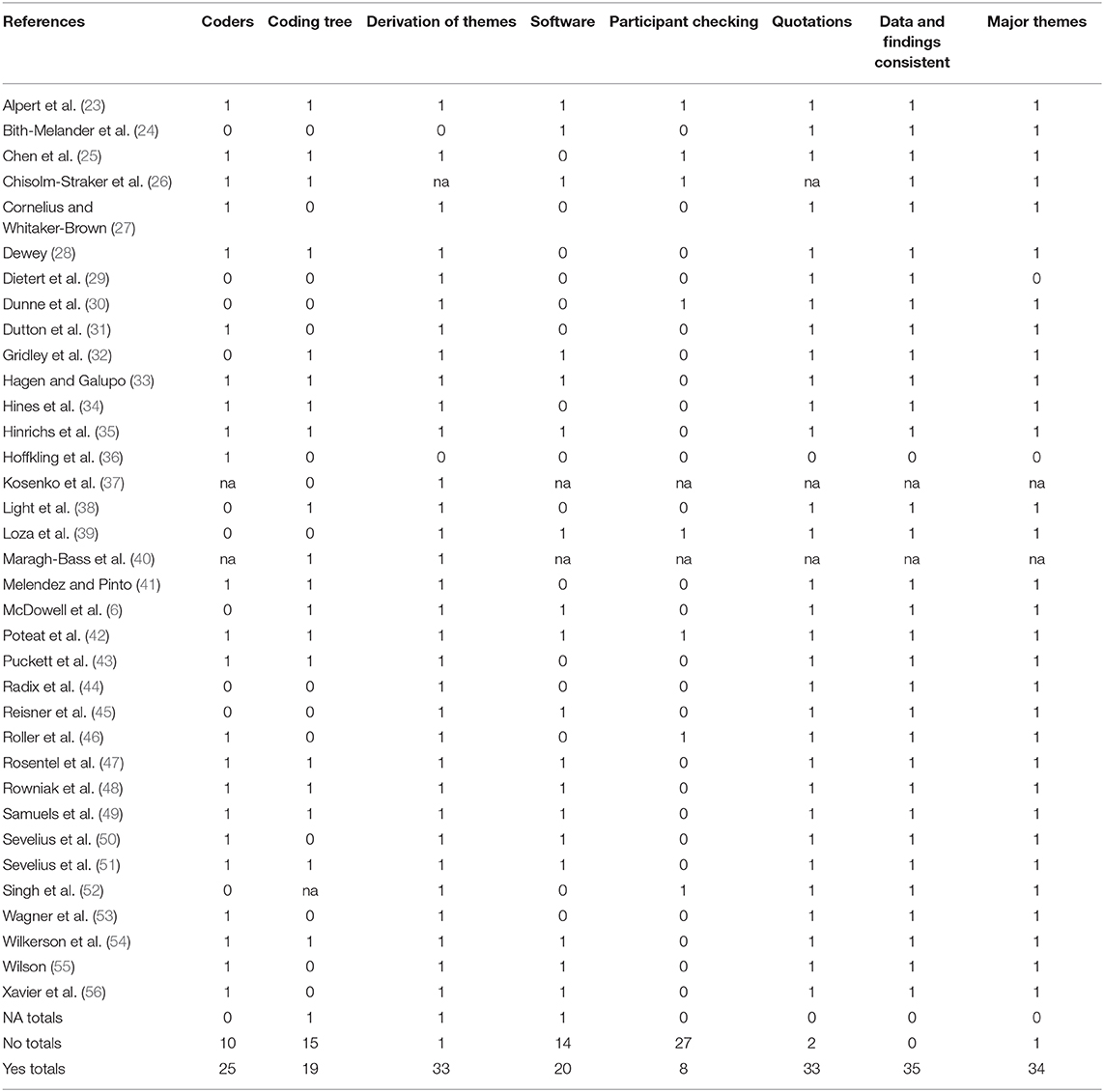

We summarized and synthesized methodological aspects and demographics from each article in Tables 2, 3. We summarized and synthesized key elements from the COREQ in Tables 4–6.

Results

Study Descriptions

Table 2 describes inclusion criteria, sample size, and participant demographics. The majority of studies addressed trans patient experiences with general care [e.g., (23, 28, 42, 45)], but six studies focused specifically on HIV care [e.g., (34, 41, 48)], four on obstetrics and gynecological care [e.g., (36, 38)], three on veteran health care clinics (25, 29, 47) and two on emergency room care (26, 49).

All studies took place in the United States (U.S.) and included transgender participants. Authors defined trans in different ways by most commonly including participants who identified as “trans” [e.g., (24, 30, 34, 46)], “trans or gender non-conforming” [e.g., (35, 43, 44)] or as having a different gender identity compared to the birth identity [e.g., (41, 51)]. One study included LGBTQ participants, of which 50% identified as trans (54) and one study included two intersex participants (49). For all other studies, TGNC comprised 100% of the study population. Just over half of the studies included participants who were 18 or older (n = 19). The most common age inclusion criteria was very broad or included participants aged 16, 18, 21, or 25 years and older without upward limits [e.g., (38–40, 48)]. Eligibility criteria for a few studies included age ranges, and two of those articles limited eligibility to youth under age 25 (32, 52). Study sample sizes ranged from 6 to 201 participants.

The actual demographic make-up of the study participants was as follows:

• Gender: This review represents 1,624 participants and 1,607 TGNC participants. Most studies included trans men and trans women; six studies included trans women only [e.g., (37, 55)] and six included trans men only [e.g., (36, 57)].

• Age: Following inclusion criteria, participants in these studies ranged from 16 to 64 years.

• Ethnicity: Three studies included 100% African American or mostly African American samples (over 90%) (27, 42, 55) and two studies had all or mostly White participants (over 90%) (38, 53). One study had mostly Latinx participants (41). The majority of studies that included race/ethnicity had a mix of ethnicities although over 10 studies included over 70% White samples. Few other races/ethnicities were strongly represented besides White, Black, or Latinx.

Study Methods Summary

Table 3 outlines study aims, recruitment settings, methods, analysis strategies, and key findings. The majority of study aims focused on exploring trans people needs, experiences, use of, or engagement in care. Other study aims centered specifically on barriers to seeking care [e.g., (32, 43)], understanding cultural competency and stigma [e.g., (23, 33, 49)], or how to improve care [e.g., (24, 38)]. Several studies highlighted trans people's resilience, facilitators, or strengths related to care [e.g., (25, 52)].

Almost all studies used a mix of recruitment methods. The most common settings were health or community centers that might serve or attract trans participants [e.g., (23, 28, 51)], social media or the web more generally [e.g., (25, 27, 52)], personal contacts [e.g., (42, 56)] or at trans-specific events [e.g., (49, 54, 57)].

The most common method that researchers used to study trans experiences were interviews [e.g., (29, 39, 53)], open-ended surveys [e.g., (37)], or focus groups [e.g., (23, 48, 56)]. A few studies used interviews and focus groups together. The most common analytic strategies were variations of thematic or content analysis [e.g., (26, 34, 45)]. A few authors cited phenomenology (31, 39, 52) or Grounded Theory [e.g., (35, 36, 46)].

Themes in Findings

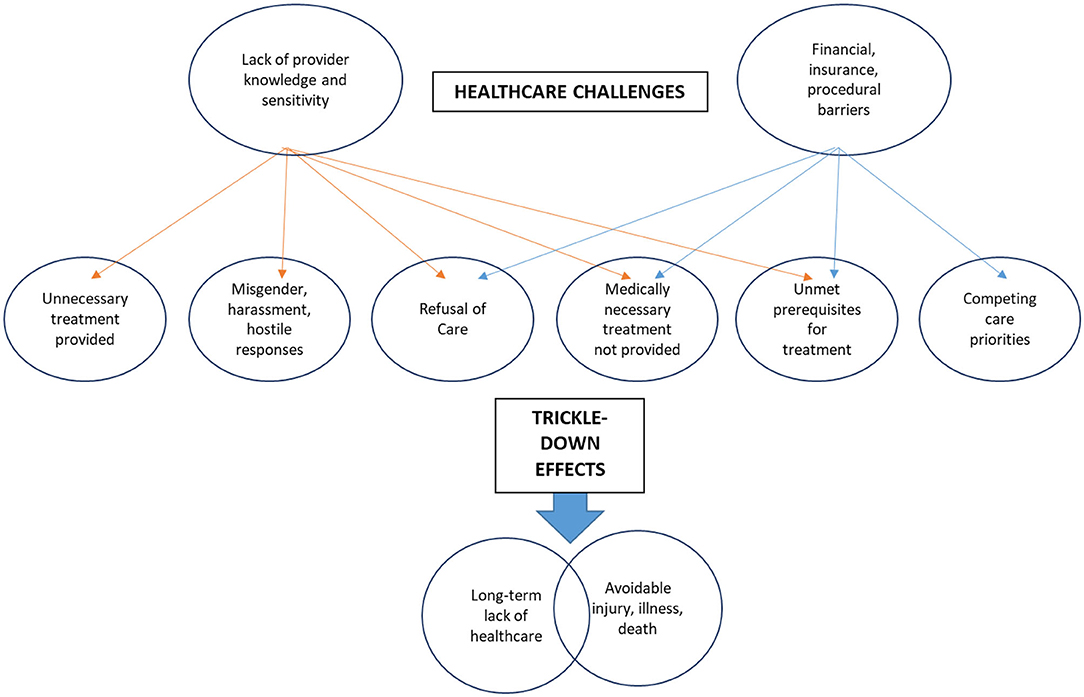

Findings were varied, given varied study aims, populations, and methods (see Table 3). We conducted a theme analysis of study findings to identify themes (21). An initial round of coding identified three major themes: health care challenges, health care needs, and TGNC resources and strengths. Challenges were the largest category of findings and included a lack of provider knowledge and or sensitivity (e.g., poor training, lack of competency, hostile treatment environments, stigma, discrimination, harassment) and financial and insurance barriers (poverty, lack of affordable care for basic health and gender affirming health changes, lack of access to care, inadequate insurance). Needs included improved care and knowledge from providers, peer support, patient autonomy, and patient-informed practices. TGNC patient strengths were persistence as a self-advocate, resilience amid adversity in life and in healthcare, and willingness to grow from adversity.

To better understand the largest category of themes, challenging experiences within the health system, we conducted a second round of coding in which findings of each research article were analyzed for mentions of major challenges—“Lack of provider knowledge and sensitivity” and “Financial/insurance barriers” and affiliated mentions of consequences (e.g., “Trickle-down effects). Code frequencies and overlaps were used to draw connections between challenges and their effects. Figure two articulates a theoretical model to conceptualize the larger impact of TGNC people's healthcare experiences (21).

Trickle-Down Effects: A Model for Conceptualizing Larger Impact

Lack of Provider Knowledge and Sensitivity

Many qualitative findings captured the detriments of lack of provider knowledge [e.g., (31, 36, 46, 53)]. Primary data illustrated that providers lacking adequate training or awareness to provide gender-affirming healthcare resulted in adverse healthcare experiences for TGNC patients. For instance, practitioners often provided unnecessary probing, questioning, or physical examinations as a result of their lack of knowledge. Practitioners were often misinformed about a potential lack of congruence between gender identity and biological anatomy, which resulted in treatment that was overly invasive or not medically necessary. Conversely, TGNC individuals frequently reported the lack of medically necessary treatment as a result of a lack of education on behalf of the medical provider. For instance, healthcare providers would often neglect to perform medically necessary cancer screenings, STI education and care, or in extreme cases, emergency medical care for illness or injury. Findings also indicated frequent harassment, misgendering, and hostile responses, ranging from humiliating the TGNC patient, refusing appropriate privacy, or asking the patient to leave the facility.

Codes nested under the theme of “Lack of provider knowledge and sensitivity” were most commonly associated with the trickle-down effects of “Long-term lack of healthcare” and “Avoidable injury, sickness, or death.” Primary qualitative data revealed that the trickle-down effects of lacking provider knowledge resulted in sustained, long-term lack of necessary physical healthcare, either as a result of fear-based avoidance, or blatant refusal of medically necessary, preventative healthcare [e.g., (23, 24, 27, 28, 35, 37, 40, 42, 43, 48, 50, 51, 56)]. Moreover, a lack of appropriate medical care often resulted in reported avoidable injury, illness, or in some circumstances, possible death of the TGNC individual. For example, qualitative evidence highlighted a range of severity, from infections resulting from emergency care practitioners ignoring symptoms or refusing care [e.g., (26, 37, 54)], cancer emerging from a lack of preventative screening [e.g., (31, 45)], or lack of life-saving treatments administered [e.g., (50, 51)]. Evidence suggested that benign ignorance about TGNC healthcare needs can have severe, life threatening consequences for TGNC patients.

Financial and Insurance Barriers

While there was some overlap with the sub-theme of “Lack of provider knowledge,” this sub-theme was distinct in that it highlighted more systemic financial and procedural barriers faced by TGNC individuals within the healthcare system. From a societal standpoint, gender affirming healthcare such as hormone therapy and surgical procedures are often not covered by insurance, and TGNC individuals are also significantly less likely to have medical coverage (23, 42, 44, 56). This leaves cost burden on the TGNC patient, resulting in debt and forces TGNC people to choose between allocating limited financial resources to either standard, preventative healthcare, or gender affirming care. Additionally, financial burden also hinders the ability to attend to prerequisite healthcare necessary for eligibility for gender affirming care. Primary qualitative data consistently described TGNC individuals that were unable to afford preliminary healthcare appointments required for receiving hormone therapy (43, 53), which sometimes led TGNC patients to seek and obtain gender affirming treatments on the black market, and/or through self-administered methods.

As a result, the trickle down effects of financial, insurance, or procedural barriers were associated with a lack of long-term healthcare and avoidable injury, illness, or possible death [e.g., (23, 26, 34, 38, 41, 45, 54, 56)]. In addition to the health risks of forced resource allocation choice or black market procedures, primary qualitative data repeatedly highlighted that TGNC individuals were more likely to turn to sex work in order to afford healthcare.

Study Quality Summary

Tables 4–6 outline the results of the COREQ. Domain one addressed research team and reflexivity with eight sub-domains. Subdomains were evaluated aggregately to understand the patterns of meeting criteria among qualitative studies of TGNC people's experience in health care. Thus, a perfect score for each sub-domain was 35 because there are 35 studies and each study received a point for addressing a domain. Average scores for each sub-domain in domain one were outlined in Table 4. The average score across all domain one sub-domain scores was 15.1. Several sub-domains in domain one were not relevant for scoring. This was true for online studies with no human interviewer for whom to consider for reflexivity issues (e.g., interviewer identity and characteristics, gender, experience/training, relationship with or knowledge of participants). Domain scores ranged from three studies to 21 studies receiving a check point for the domains (see Table 4). Studies (20 or more out of 35) most commonly identified interviewer identity; interviewer gender; and participant knowledge of the interviewer, as their reasons for doing the research. Studies also frequently identified the credentials of the primary author of the study. Few studies have determined if the interviewer established a relationship with participants prior to the study (only three studies) and reported characteristics about the interviewer (only six studies), such as potential interviewer biases and assumptions.

Domain two addressed study design with 15 sub-domains. Summary scores for each sub-domain are in Table 5. The average score across all domain two scores was 21.6. Domain scores ranged from two to 35 studies receiving a check point for the domains. Nearly all (35/35) of the studies identified study methodological orientation or theory, sampling strategy, sample size, and sample description. Many studies (e.g., 20 or more) reported the study duration and setting, method of recruiting participants, description of an interview guide, and whether or not interviews were recorded. Few studies described who refused to participate or dropped out of the study (nine studies), who was present besides researchers or participants in the interviews (nine studies), if repeat interviews were carried out (seven studies) or if transcripts were returned to participants for corrections or comments (two studies).

Domain three addressed analysis and findings with nine sub-domains. Average scores for each sub-domain are in Table 6. The average score across all sub-domains was 26.3. Domain three scores ranged from eight to 35 studies receiving check points for the domains. Thirty or more studies described how they derived themes from the data, presented results that were consistent with their analyses, described major and minor themes, and provided participant quotations. Only eight studies commented on allowing the participants the opportunity to give feedback on the findings.

Discussion

This scoping review summarized elements of studies addressing TGNC people's experiences of receiving physical health care and identified directions for theory, research, and practice to explain and address TGNC people's health care experiences. Reviews to date cover TGNC people's experiences of mental health care and limited aspects of physical health care. This review builds on and expands those findings.

Stigma and Discrimination

White and Fontenot (4) found that although participants did report welcoming mental health care environments, most also experienced stigma and discrimination, which was worse for racial/ethnic minority TGNC persons. Our findings indicated that TGNC people face similar challenges in physical health care, and in addition to the stigma, report that providers lack competency, education, and ability to give patients referrals for more complex physical needs like surgeries. Other recent reviews on aspects of TGNC people's physical health care experiences included a focus on discrimination and stigma at the provider, office, and medical system level (4, 18). Moreover, our findings highlighted that the consequences of adverse health system experiences are pervasive across the life span, and throughout all domains of biological, psychological, and social health. Indirect consequences resulting include lack of ongoing healthcare and life-long avoidance and/or fear of the health system, sub-standard health care that does not meet the health needs of the individual, and in the worst case, avoidable injury or death.

TGNC people also reported lack of access to adequate care, which reflects discrimination at the structural level. For example, problems attaining employment, which could relate to employment discrimination, can hurt health care options. Lack of insurance coverage for services that TGNC people need—such as reassignment surgeries—also reflects a larger system bias against understanding these processes as necessary.

Resilience Amid Discrimination

Despite challenges, our findings also add an awareness of patient identified areas of strengths. Studies in this review identified the importance of positive influences like peer support, patient autonomy, and patient-informed practices. Additionally, TGNC patients are resilient, and willing to self-advocate if given opportunities and skills. Such resiliency, if respected and built upon by providers, could help TGNC people navigate the health care system more successfully.

Provider Impact and Trickle-Down Consequences of TGNC Care

The theoretical model produced (Figure 2) highlights extensive thematic analysis for the purpose of presenting a conceptual model to aid healthcare practitioners in comprehending the severe consequences of adverse healthcare experiences for TGNC individuals. This model highlights the life-long health consequences of such experiences. By highlighting the trickle-down challenges of TGNC patients, health practitioners have the capacity to better understand the long-term effects of their medical decisions and practices. In addition, health practitioners can better conceptualize the impetus for obtaining appropriate gender-affirming training and understanding the health needs of TGNC patients.

Limitations of Existing TGNC Healthcare Data

This review also highlighted several notable issues in the existing body of qualitative work on TGNC people's physical health care experiences. On one hand, the amount of information generated by qualitative studies was rich, detailed, and revealing. On the other hand, study samples were limited demographically. There were inconsistencies in how each research team defined trans people which made it challenging to compare and collate research results (58). Also, as trans research grows, and different groups under the trans umbrella become more visible, it is important to acknowledge the heterogeneity of trans people and their needs. Recent research, for example, notes that non-gender conforming groups report worse health outcomes than those who identify as trans male or female (59–61). Given that one of the strengths of qualitative research is to explore in depth the experiences of specific groups of people, studies differentiated by varied trans identities may be more informative than studies that have a broad sample of all TGNC identities.

Relatedly, studies addressed the experiences of a wide range of ages. It was common for studies to include samples of “18 and older.” Different life phases bring different health challenges, however. Research points toward distinct disparities and health concerns for very young (62) and aging trans people (63), for example. Future studies may be able to generate even more useable results if they focus on specific life experiences, like youth, adolescence, mid-life or older adulthood. Only three studies focused on the experiences of African American TGNC people, despite research that intersections of identity, such as ethnicity and gender, matter, for an assessment of health care experiences and outcomes (64).

Similarly, most of the studies in this review covered health generally, a very broad topic. Specific studies were limited to explorations of HIV or obstetric health care or the delivery of veteran or emergency room services. Given the range of health disparities experienced by trans people, an understanding of broader experiences of physical care are needed.

Several studies used online surveys, which resulted in larger samples. In other areas of research on sensitive topics, like sexual behavior, for example, online surveys or mechanisms of answering sensitive questions elicit higher reports of sensitive risk behaviors (65). Limitations exist as well, such as the inability to explore issues in depth with an interviewer. Online surveys are necessary for the broad recruitment of TGNC samples but may miss the nuances of regional experiences. Additional research should investigate the pros and cons of online surveys verses local interviews.

The most common methods used in the studies were individual or group interviews. Although these methods are valuable, there may be a place for additional methods, like ethnography or visual methods in this field, to supplement existing research with observations of doctor visits to assist in the description of the health care experience. These methods may add depth to existing studies.

Relatedly, the review identified only one community based participatory research (CBPR) study (66). CBPR is a partnership approach to research in which researchers and communities work together to define research problems, determine how to study them, and translate results into action. Given the success of CBPR in conducting collaborative research and disseminating collaborative results with marginalized communities (66, 67), CBPR qualitative studies may be a helpful addition to this field of work and may further drive research questions and answer to solutions. The studies in this review predominantly used theme analysis, which was a beneficial tool in identifying patterns in data. As the field of TGNC health grows, moving beyond identification of patterns to more complex forms of analysis, like theory generation, will help move the field forward (20).

Study Limitations

Our review was subject to several limitations. Although systematic, it was possible that we excluded articles despite our library search. The COREQ is a valuable instrument to assess the quality of qualitative work (19). In the context of this analysis, however, limitations did exist. Domain 1, regarding the research team, assumes an in-person interaction, not an online survey. Given the rising popularity of on-line qualitative instruments, challenges arise when using the COREQ. The gender item under reflexivity was stated as a binary (e.g., was the researcher male or female) which was not always relevant to our studies. Some of the other topics were uncommon in our studies all-together. For example, the presence of non-participants in an interview setting and conducting repeating interviews (domain 2) were not entirely clear and were frequently not reported. The first three items in domain 3 (e.g., were major themes presented clearly?) are widely open to interpretation, unlike many of the other specific elements of the instrument. In addition, we limited the review to U.S. based studies. The review does not capture the experience of TGNC in developing and/or countries outside of the U.S.

Those limitations notwithstanding, this was the first study, to our knowledge to evaluate qualitative trans studies using the COREQ, which offered important patterns for attention in future research. The least commonly reported items in domain one were the characteristics of the interviewer and the interviewer relationship with the participant. Excluding limiting measures listed above, least commonly reported items in domain two were data saturation and information about the people who refused participation in the study. In domain three, participant checking was least reported.

Future Research Directions

Our analysis also identifies important areas for future study and action regarding the physical health care experiences of TGNC people. The experiences of diverse TGNC including gender, age, ethnic and other diverse aspects of identity—and diverse health care experiences, and resiliency, are in need of further study. These strategies are particularly important for qualitative research that explore subpopulations in great detail. Methods beyond interview and focus group alone, such as ethnography, visual methods, or participatory approaches may add to current qualitative findings. Going beyond capturing themes to building theory will be critical. Measures beyond the COREQ, to capture the growing field of online interviewing, will assist with building the field.

Future Practice Directions

Our findings reveal the need for change in the physical health care system, as the health consequences for transgender individuals are severe and perpetuate life-long health disparities. For the purpose of informing health professionals about the severity of stigma, discrimination, and challenges within the health environment for TGNC individuals, findings from our analysis were used to develop a theoretical model of trickle-down effects of adverse experiences (21). This model synthesizes salient themes and connects challenges identified within this qualitative scoping review to latent trickle-down effects of adverse experiences (see Figure 2). This model was intended to accompany findings reported in this study, while also translating research findings directly to practice.

Author Contributions

MT conceptualized the article, led the analysis, and writing of the article. SK took part in article review and wrote significant parts of the discussion. LB took part in article review and helped with the introduction. EK helped with article review and article editing. RG led the search for articles. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Edmiston EK, Donald CA, Rose Sattler A, Klint Peebles J, Ehrenfeld JM, Eckstrand KL. Preventative health services for transgender patients: a systemic review. Transgender Health. (2016) 1:216–30. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0019

2. Safer JD, Coleman E, Feldman J, Garofalo R, Hembree W, Radix A, et al. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obesity. (2016) 23:168–71. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000227

3. American Pschological Association. Transgender People, Gender Identity and Gender Expression. (2019). Available online at: https://www.apa.org/topics/lgbt/transgender

4. White BP, Fontenot HB. Transgender and non-conforming persons' mental healthcare experiences: an integrative review. Arch Psychiatric Nurs. (2019) 33:203–10. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2019.01.005

5. Lefevor GT, Boyd-Rogers CC, Sprague BM, Janis RA. Health disparities between genderqueer, transgender, and cisgender individuals: an extension of minority stress theory. J Counsel Psychol. (2019) 66:385–95. doi: 10.1037/cou0000339

6. McDowell MJ, Hughto JMW, Reisner SL. Risk and protective factors for mental health morbidity in a community sample of female-to-male trans-masculine adults. BMC Psychiatry. (2019) 19:16. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-2008-0

7. Tebbe EA, Moradi B. Suicide risk in trans populations: an application of minority stress theory. J Counsel Psychol. (2016) 63:520–33. doi: 10.1037/cou0000152

8. Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, Barrios LC, Demissie Z, McManus T, et al. Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students - 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. Morbid Mortality Weekly Rep. (2019) 68:67–71. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3

9. Becasen JS, Denard CL, Mullins MM, Higa DH, Sipe TA. Estimating the prevalence of HIV and sexual behaviors among the US transgender population: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2006-2017. Am J Public Health. (2018) 109:e1–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304727

10. Streed CG, McCarthy EP, Hass JS. Association between gender minority stress and self-reported physical and mental health in the United States. JAMA Internal Med. (2017) 177:1210–1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1460

11. Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychol Res Pract. (2012) 43:460–7. doi: 10.1037/a0029597

12. Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. (2011). Washington, DC. Available online at: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/The-Health-of-Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-and-Transgender-People.aspx

13. Motmans J, Nieder TO, Bouman WP. Transforming the paradigm of nonbinary transgender health: a field in transition. Int J Transgend. (2019) 20:119–25. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2019.1640514

14. Korpaisarn S, Safer JD. Gaps in transgender medical education among healthcare providers: a major barrier to care for transgender persons. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. (2018) 19:271–5. doi: 10.1007/s11154-018-9452-5

15. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S.Transgender Survey. (2016). Available online at: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

16. Lerner JE, Robles G. Perceived barriers and facilitators to health care utilization in the United States for transgender people: a review of recent literature. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2017) 28:127–52. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2017.0014

17. Cicero EC, Reisner SL, Silva SG, Merwin EI, Humphreys JC. Health care experiences of transgender adults: an integrated mixed research literature review. Adv Nurs Sci. (2019) 42:123–38. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000256

18. Heng A, Heal C, Banks J, Preston R. Transgender people's experiences and perspectives about general healthcare: a systematic review. Int J Transgenderism. (2018) 19:359–78. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2018.1502711

19. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

20. Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications (2008).

22. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

23. Alpert AB, CichoskiKelly EM, Fox AD. What lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex patients say doctors should know and do: a qualitative study. J Homosexual. (2017) 64:1368–89. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1321376

24. Bith-Melander P, Sheoran B, Sheth L, Bermudez C, Drone J, Wood W, et al. Understanding sociocultural and psychological factors affecting transgender people of color in San Francisco. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. (2010) 21:207–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.01.008

25. Chen JA, Granato H, Shipherd JC, Simpson T, Lehavot K. A qualitative analysis of transgender veterans' lived experiences. Psychol Sexual Orientation Gender Diversity. (2017) 4:63–74. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000217

26. Chisolm-Straker M, Jardine L, Bennouna C, Morency-Brassard N, Coy L, Egemba MO, et al. Transgender and gender nonconforming in emergency departments: a qualitative report of patient experiences. Transgender Health. (2017) 2:8–16. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0026

27. Cornelius JB, Whitaker-Brown CD. African American transgender women's individual, family, and organizational relationships: implications for nurses. Clin Nurs Res. (2017) 26:318–36. doi: 10.1177/1054773815627152

28. Dewey JM. Knowledge legitimacy: how trans-patient behavior supports and challenges current medical knowledge. Qualitative Health Res. (2008) 18:1345–55. doi: 10.1177/1049732308324247

29. Dietert M, Dentice D, Keig Z. Addressing the needs of transgender military veterans: better access and more comprehensive care. Transgender Health. (2017) 2:35–44. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0040

30. Dunne MJ, Raynor LA, Cottrell EK, Pinnock WJA. Interviews with patients and providers on transgender and gender nonconforming health data collection in the electronic health record. Transgender Health. (2017) 2:1–7. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0041

31. Dutton L, Koenig K, Fennie K. Gynecologic care of the female-to-male transgender man. J Midwifery Womens Health. (2008) 53:331–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.02.003

32. Gridley SJ, Crouch JM, Evans Y, Eng W, Antoon E, Lyapustina M, et al. Youth and caregiver perspectives on barriers to gender-affirming health care for transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. (2016) 59:254–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.017

33. Hagen DB, Galupo MP. Trans* individuals' experiences of gendered language with health care providers: recommendations for practitioners. Int J Transgenderism. (2014) 15:16–34. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2014.890560

34. Hines DD, Draucker CB, Habermann B. HIV testing and entry to care among trans women in Indiana. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. (2017) 28:723–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2017.05.003

35. Hinrichs A, Link C, Seaquist L, Ehlinger P, Aldrin S, Pratt R. Transgender and gender nonconforming patient experiences at a family medicine clinic. Acad Med. (2018) 93:76–81. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001837

36. Hoffkling A, Obedin-Maliver J, Sevelius J. From erasure to opportunity: a qualitative study of the experiences of transgender men around pregnancy and recommendations for providers. Pregnancy Childbirth. (2017) 17:332. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1491-5

37. Kosenko K, Rintamaki L, Raney S, Maness K. Transgender patient perceptions of stigma in health care contexts. Med Care. (2013) 51:819–22. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829fa90d

38. Light AD, Obedin-Maliver J, Sevelius JM, Kerns JL. Transgender men who experienced pregnancy after female-to-male gender transitioning. Obstetr Gynecol. (2014) 124:1120–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000540

39. Loza O, Beltran O, Mangadu T. A qualitative exploratory study on gender identity and the health risks and barriers to care for transgender women living in a U.S.–Mexico border city. Int J Transgenderism. (2017) 18:104–18. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2016.1255868

40. Maragh-Bass AC, Torain M, Adler R, Ranjit A, Schneider E, Shields RY, et al. Is it okay to ask: transgender patient perspectives on sexual orientation and gender identity collection in healthcare. Acad Emerg Med. (2017) 24:655–67. doi: 10.1111/acem.13182

41. Melendez RM, Pinto RM. HIV prevention and primary care for transgender women in a community-based clinic. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. (2009) 20:387–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.06.002

42. Poteat T, German D, Kerrigan D. Managing uncertainty: a grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 84:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019

43. Puckett JA, Cleary P, Rossman K, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Barriers to gender-affirming care for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. Sex Res Soc Policy. (2018) 15:48–59. doi: 10.1007/s13178-017-0295-8

44. Radix AE, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Gamarel KE. Satisfaction and healthcare utilization of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals in NYC: a community-based participatory study. LGBT Health. (2014) 1:302–8. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0042

45. Reisner SL, Perkovich B, Mimiaga MJ. A mixed methods study of the sexual health needs of New England transmen who have sex with nontransgender men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. (2010) 24:501–13. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0059

46. Roller CG, Sedlak C, Draucker CB. Navigating the system: how transgender individuals engage in health care services. J Nurs Scholarship. (2015) 47:417–24. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12160

47. Rosentel K, Hill BJ, Lu C, Barnett JT. Transgender veterans and the veterans health administration: exploring the experiences of transgender veterans in the veterans affairs healthcare system. Transgender Health. (2016) 1:108–16. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0006

48. Rowniak S, Ong-Flaherty C, Selix N, Kowell N. Attitudes, beliefs, and barriers to PrEP among trans men. AIDS Educ Prev. (2017) 29:302–14. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2017.29.4.302

49. Samuels EA, Tape C, Garber N, Bowman S, Choo EK. “Sometimes you feel like the freak show”: a qualitative assessment of emergency care experiences among transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. Ann Emerg Med. (2018) 71:170–82.e171. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.05.002

50. Sevelius JM, Patouhas E, Keatley JG, Johnson MO. Barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in care among transgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus. Ann Behav Med. (2014) 47:5–16. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9565-8

51. Sevelius JM, Keatley J, Calma N, Arnold E. 'I am not a man': Trans-specific barriers and facilitators to PrEP acceptability among transgender women. Global Public Health. (2016) 11:1060–75. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1154085

52. Singh AA, Meng SE, Hansen AW. 'I am my own gender': resilience strategies of trans youth. J Counsel Dev. (2014) 92:208–18. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00150.x

53. Wagner PE, Kunkel A, Asbury MB, Soto F. Health (Trans)gressions: identity and stigma management in trans* healthcare support seeking. Women Lang. (2016) 39:49–74.

54. Wilkerson J, Rybicki M, Barber S, Cheryl A, Smolenski DJ. Creating a culturally competent clinical environment for LGBT patients. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. (2011) 23:376–94. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2011.589254

55. Wilson EC, Arayasiriku S, Johnson K. Access to HIV care and support services for African American transwomen living with HIV. Int J Transgenderism. (2014) 14:182–95. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2014.890090

56. Xavier J, Bradford J, Hendricks ML, Safford L, McKee R, Martin E, et al. Transgender health care access in virginia: a qualitative study. Int J Transgenderism. (2013) 14:13–7. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2013.689513

57. Peitzmeier SM, Agenor M, Bernstein IM, McDowell M, Alizaga NM, Reisner SL, et al. “It can promote an existential crisis”: factors influencing pap test acceptability and utilization among transmasculine individuals. Qualitative Health Res. (2017) 27:2138–49. doi: 10.1177/1049732317725513

58. Reisner SL, Deutsch MB, Bhasin S, Bockting W, Brown GR, Feldman J, et al. Advancing methods for US transgender health research. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obesity. (2016) 23:198–207. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000229

59. Aparicio-García ME, Díaz-Ramiro EM, Rubio-Valdehita S, López-Núñez MI, García-Nieto I. Health and well-being of cisgender, transgender and non-binary young people. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:2133. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102133

60. Olson-Kennedy J, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Kreukels BP, Meyer-Bahlburg HF, Garofalo R, Meyer W, et al. Research priorities for gender nonconforming/transgender youth: gender identity development and biopsychosocial outcomes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obesity. (2016) 23:172–9. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000236

61. Rider GN, McMorris BJ, Gower AL, Coleman E, Eisenberg ME. Health and care utilization of transgender and gender nonconforming youth: a population-based study. Pediatrics. (2018) 141:e20171683. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1683

62. Connolly MD, Zervos MJ, Barone CJ 2nd, Johnson CC, Joseph CL. The mental health of transgender youth: advances in understanding. J Adolesc Health. (2016) 59:489–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.012

63. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Cook-Daniels L, Kim HJ, Erosheva EA, Emlet CA, Hoy-Ellis CP, et al. Physical and mental health of transgender older adults: an at-risk and underserved population. Gerontologist. (2014) 54:488–500. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt021

64. Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality - an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. (2012) 102:1267–73. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750

65. Macalino GE, Celentano DD, Latkin C, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D. Risk behaviors by audio computer-assisted self-interviews among HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative injection drug users. AIDS Educ Prev. (2002) 14:367–78. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.6.367.24075

66. Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, Schulz AJ, McGranaghan RJ, Lichtenstein R, et al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. (2010) 100:2094–102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506

Keywords: transgender, health care, health disparities, qualitative, scoping review transgender healthcare experiences and needs

Citation: Teti M, Kerr S, Bauerband LA, Koegler E and Graves R (2021) A Qualitative Scoping Review of Transgender and Gender Non-conforming People's Physical Healthcare Experiences and Needs. Front. Public Health 9:598455. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.598455

Received: 24 August 2020; Accepted: 11 January 2021;

Published: 05 February 2021.

Edited by:

Katherine Henrietta Leith, University of South Carolina, United StatesReviewed by:

Miodraga Stefanovska-Petkovska, Universidade de Lisboa, PortugalCaroline Diane Bergeron, Public Health Agency of Canada, Canada

Copyright © 2021 Teti, Kerr, Bauerband, Koegler and Graves. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michelle Teti, dGV0aW1AaGVhbHRoLm1pc3NvdXJpLmVkdQ==

Michelle Teti1*

Michelle Teti1* Erica Koegler

Erica Koegler