94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 09 April 2021

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.593553

This paper describes a framework used to understand public health entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship for the purpose of pedagogy and practice. To ground this framework in the academic literature, a scoping review of the literature was conducted with application of a snowball method to identify further articles from the bibliographies of the search results. Recurring themes were identified to characterize common patterns of public health entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship. These themes were design thinking, resource mobilization, financial viability, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and systems strengthening. Case examples are provided to illustrate key themes in both intrapreneurship and entrepreneurship. This framework is a starting point to further the discourse, teaching, and practice of entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship in public health. More research is needed to understand implications for power and privilege, capacity building, financing, scaling, and policy making related to entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship in public health.

Public health entrepreneurship is an emerging field, driven by the desire of public health students and practitioners to be more action oriented. In a recent study, public health students voiced that public health research must be accompanied by action; public health entrepreneurship provides a potential pathway for action; a unique skillset is required for public health entrepreneurship; and public health entrepreneurship provides an opportunity for inter-professional collaboration and cross-pollination of knowledge across disciplines (1). However, no framework has been published for understanding and teaching public health entrepreneurship. Comprehensive frameworks have been developed for learning and teaching medical device innovation, social entrepreneurship, and general entrepreneurship but these views do not directly link to and center on public health perspectives, problems and solutions (2–4). Entrepreneurship as an experimental process has been packaged and popularized using approaches such as the lean startup method, which may not be suited for all entrepreneurial endeavors (5). Suitable and effective approaches for a particular problem may be contingent on industry, cultural practices, stakeholders, technology and other factors; hence the need for a specialized framework. The business and management literature includes a wide range of definitions and scopes for entrepreneurship. In a recent review, Botelho et al. divide these into four categories: subsistence entrepreneurship, self-employed entrepreneurs, traditional business entrepreneurship, and innovation driven entrepreneurship. This article focuses on the latter category. Innovation entrepreneurship entails entering into new, often unknown or unproven, markets that are characterized by high uncertainty. Innovation driven entrepreneurship does not necessarily require new high-technological advances, but rather a new recombination that produces a new way of conducting a particular set of activities (6). Social entrepreneurship more specifically is driven by social innovation and the desire to produce social change. Dees defines social entrepreneurs as those who play the role of change agents in the social sector by adopting a mission, recognizing and relentlessly pursuing new opportunities to serve that mission, engaging in a process of continuous innovation with accountability to constituencies served and outcomes created; and acting boldly without being limited by resources currently in hand (7). Public Health entrepreneurship is a form of social entrepreneurship.

Public health entrepreneurship has been defined as “the application of entrepreneurial skills to advance public health” (8). This definition implies the inclusion of intrapreneurship: applying an entrepreneurial mindset and skillset within an existing organization. Public health entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship (PHEI) takes as its starting point the public health mission and social justice (9).

The literature on PHEI is limited, yet indicates an appetite for greater understanding of and planning for this area of training and practice (10). As PHEI emerges as a field of training and practice, a framework is needed to structure future research, pedagogy, and implementation. This paper describes a scoping literature review to inform a framework for teaching public health entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship.

A literature review was conducted to identify papers with public health entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship as their primary focus, as indicated by the title. The search terms [“public health”] AND [“entrepreneurship” OR “intrapreneurship” OR “innovation”] were applied in a pub med title search. This identified 88 papers, which were screened based on the Jacobsen et al. definition of the application of entrepreneurial skills to advance public health (8). The screening narrowed down the results to 23 papers which fell under the scope of this definition. A snowball method was applied to include relevant references cited in the bibliographies of the 23 articles, resulting in a total of 96 papers (Figure 1). The relevancy of references cited in the bibliographies was determined again by the above definition of the application of entrepreneurial skills to advance public health. These 96 papers were reviewed and tabulated; and common patterns in public health entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship (PHEI) were extracted using thematic analysis.

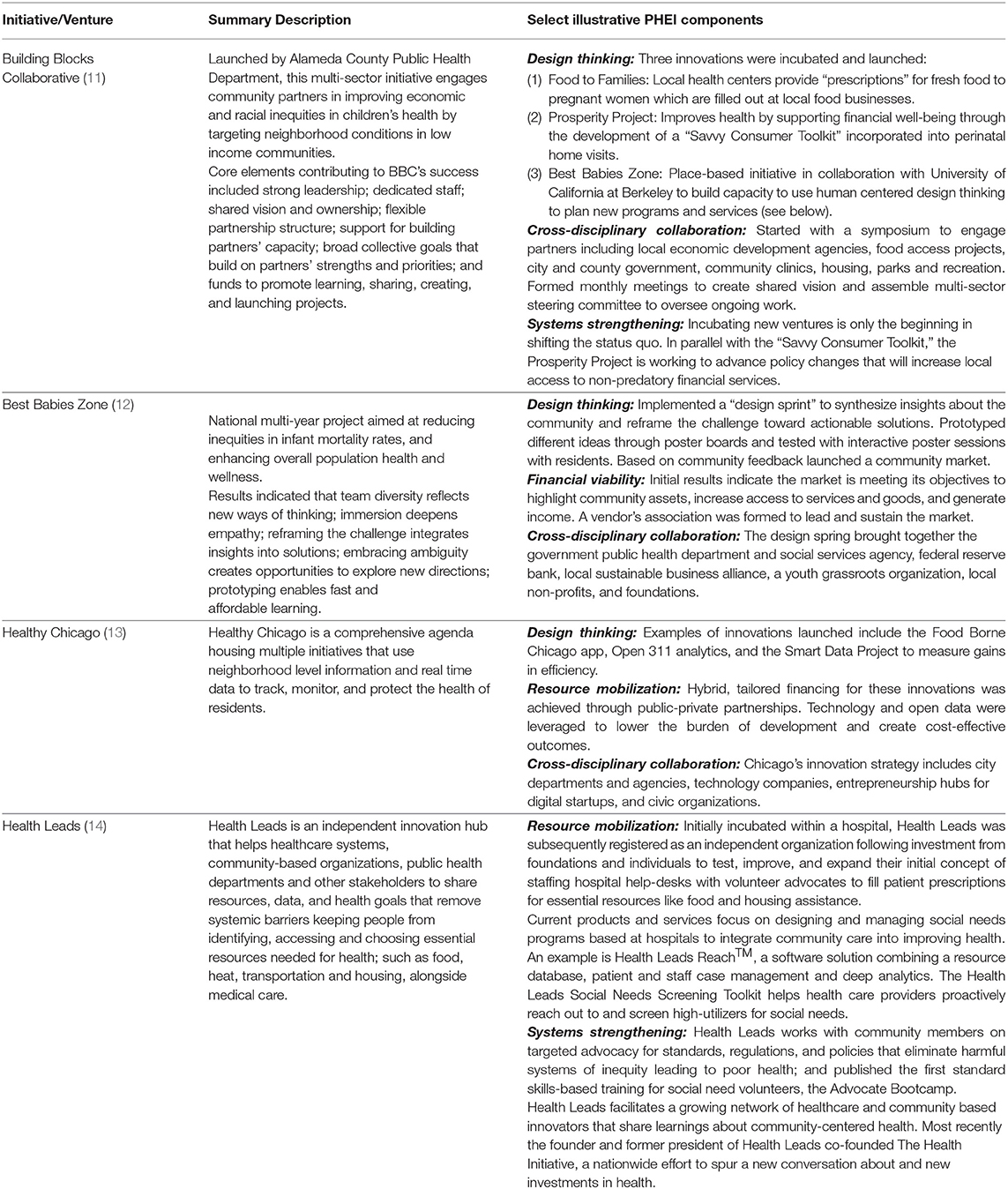

Five integral components of PHEI were identified through thematic analysis of the 96 resulting papers. These components are described below and illustrated with case examples (Table 1). A full list of the 96 articles is presented in Appendix 1.

Table 1. Case examples from literature review illustrating key components of public health entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship.

A pre-requisite for PHEI is human centered design thinking. Design thinking is a problem-solving methodology that focuses on in-depth understanding, rapid idea generation, and prototyping to generate innovative solutions to complex challenges (11). It is an adaptive process for innovation that prioritizes the needs and values of the people most affected. Engaging communities in identifying needs and assets is already a characteristic of evidence based public health (15). Design thinking adds the elements of rapid prototyping, testing and iteration with constant feedback from users to generate rapid cycles of failure and accelerate learning (16). Local community based organizations can act as laboratories for developing new solutions and service delivery (17). The government public health workforce can also be a source of entrepreneurial activity (8). Creativity can be learned (18). Building a culture of innovation in public health requires the allocation of time and resources to iterate and learn from failures (8, 19–21). This includes recognizing that innovation has a high risk of failure, and learning to manage risk. These elements of design thinking have been reflected in various approaches to defining public health innovation (Table 2).

Farmer and Fizpatrick point to Drucker's use of the term entrepreneurship to describe entrepreneurs in the 1800s as those who shift resources into areas of greater yield. They apply this definition to health workers who identify opportunities, mobilize people and resources including funding; demonstrating persistence in serially initiating new initiatives by identifying gaps, injecting their vision, exciting others and securing resources (27). Hernandez et al. refer to Dees' description of social entrepreneurs as acting boldly without being limited by resources currently in hand (10). Wei-Skillern highlights the entrepreneurial quality of mobilizing resources beyond one's control (28). Orton describes competency in civic entrepreneurship as the ability to combine skills, marshal human and other resources, attract start-up funds, and identify revenue streams for sustainability (29).

Funding is an important component of resource mobilization and authors voiced a need within more traditional public health institutions for smaller grants that support prototype projects and allow creators to pursue ideas to failure or success (21). The importance of funding from the private sector and health sector payers including major provider networks and managed care organizations was also emphasized; as well as the need to bring in new players and social investment approaches such as the Global Impact Investing Network (22). Flexible funding streams are needed to innovate new funding models blending funds from a variety of sources (30).

Building a business model was cited as an important component of adopting a public health innovation approach; bridging direct health sector innovation with global and domestic public health problems, the former of which is often venture capital backed and profit oriented and the latter of which requires a non-profit approach (22). Financial viability can either refer to a business model which generates new sources of revenue, for example in the case of a new venture; or that which results in improved efficiencies and cost savings, for example in the case of intrapreneurship within government agencies. Sources of revenue may include payers such as Medicaid (8). Microenterprise was also cited as a business model (17).

PHEI teams are interdisciplinary in composition, including different sub-disciplines and skill areas within the field of public health, such as health management, policy, epidemiology, bioinformatics, social and behavioral sciences, nutrition and environmental sciences; alongside roles and professions from other fields such as engineering, information technology, education, urban planning, social media, design, management and finance (9, 13, 18, 31, 32). Beyond the internal composition of the team, PHEI leverages partnerships across sectors in the design and implementation of public health innovations. These may include local health departments, policy experts, civic and business technologists, funding organizations, community-based organizations, and universities (8, 13, 16, 17, 33). More broadly speaking, PHEI entails a decentralized, multisectoral, horizontal collaborative problem solving approach, forming alliances and bringing together multiple actors such as entrepreneurs, activists, economists, academics, scientists, researchers, private sector, government sector, technology users (17, 19, 29, 34). Thus, PHEI breaks silos within and beyond the walls of public health, at multiple levels including the internal team, formal partners, and other collaborators (Figure 2).

Through this network approach, the products and services created through PHEI aim to strengthen existing systems, rather than creating parallel systems; through careful consideration, and integration of existing infrastructure and stakeholders (28). Systems thinking requires going beyond the involvement of different disciplines to understand the relationships between them and how those interactions will change as a result of the proposed innovation (35). When combined with an entrepreneurial orientation, systems thinking can result in novel solutions-oriented approach to complex problems; this aspect of PHEI is critical in ensuring that the improvements which are made in the health of the public are made equitably (9). Systems thinking requires novel metrics to capture the impact of PHEI beyond the traditionally used additive input-output evaluation approaches (16).

The five components of the PHEI framework are summarized in Table 3.

This is the first paper to present a framework for characterizing entrepreneurship and intrapreneuership in public health. The scoping literature review conducted to inform this framework resulted in more examples of intrapreneurship within government than of entrepreneurship and new ventures. This result, combined with the intrinsic nature of public health systems, underscores the importance of developing frameworks for understanding and supporting public health entrepreneurship that include innovations within and across government systems.

This framework has been tested for pedagological purposes through a course launched at Yale University titled “Public Health Entrepreneurship and Intrapreneurship.” The course was structured around the components of the framework; and was cross-registered at Yale School of Management, School of Public Health, School of Environment, and Jackson Institute of Global Affairs. The PHEI framework was used to analyze case studies of PHEI identified through the author's work and through case study collections including Yale School of Management raw cases and Harvard Business School Publishing. Topics areas included primary health, maternal child health, social and environmental determinants of health; spanning global and domestic settings. Fifty five students registered for the course, giving it an overall rating of 4.3/5 in the course evaluation. A sample comment stated that students “appreciated the funding/management perspective of the course. Often as a public health student. we try to implement an educational campaign to bring awareness to solve issues. This course talked about funding models beyond donor support, and partnerships and stakeholder engagement.”

Feedback was also solicited at the American Public Health Association (APHA) annual meeting in Fall 2019, during a round table session held by the community-based public health caucus. During the 90-min session, a one-page overview of the framework was distributed and presented by the author to participants in four back-to-back round table discussions. Comments was elicited from fifteen participants through focus group discussion in conjunction with a written survey. A sample comment indicated that “while this is a valuable framework to understand entrepreneurship and intrapraneurship in the context of public health training, a more detailed framework is needed to inform investment decisions and capacity building for public health entrepreneurs.” Other comments included the importance of linking PHEI with public health policy.

Further input was elicited from twelve subject matter experts including authors of selected papers and public health entrepreneurs through telephone interviews. Participants commented that human centered design thinking can help ensure a constant feedback loop of community voice and public participation in the design and implementation of public health programs, mimicking the “product market fit” of the private sector; as opposed to traditional public health programs which are designed using a top-down rather than a bottom-up approach. While some emphasized the importance of the ideation process of human centered design thinking, others emphasized the importance of integrating existing ideas into existing systems rather than generating new ideas. The use of data was underscored to balance risk with evidence, and to develop adaptive revenue models which are responsive to the scientific models underlying public health products and services. Feedback was consistent on the importance of being risk prepared rather than risk averse; and on the role of managing failure as a part of the design and iteration process.

It was noted that the framework does not explicitly address power and privilege. Design thinking entails community engagement, but it is important to analyze cases with a critical lens to determine whether different voices were heard, whether the community participated in a meaningful rather than tokenizing way, and whether community capacity and leadership were built. Systems thinking also entails understanding whether root causes and inequities are being addressed, and whether the venture will result in a shift of power to address root causes and inequities. Just as PHEI requires a shift in culture to budget for and manage risks and failures, so too does it require a shift in culture to innovate with rather than for marginalized and underserved individuals and communities. With the application of this framework over time and the unfolding of further research and practice in PHEI, these and other nuances in the initial components of the framework may be further developed into separate components. This is also likely to include the financing and policy related aspects of PHEI. Another area for further development is understanding and characterizing the relationship between the different components.

Finally, it is important to note that a limitation of this study is that it is a scoping review which does not attempt to capture the full literature on PHEI. While it may be too early in this emerging sub-discipline of public health for a systematic review, the results indicate a growing number of attempts to characterize PHEI in the literature, especially in government settings. The number of papers on entrepreneurship and new ventures in public health was limited, indicating an opportunity for partnership between academic researchers and entrepreneurs. The accelerated digital transformation in healthcare and public health catalyzed by Covid-19 presents a ripe opportunity for case studies to explore how themes of this paper were or were not applied (36–38). Moreover, while this search was conducted using PubMed to capture public health publications, a more comprehensive search in the future could include additional databases to capture a broader set of journals in the social sciences, management and business. This may result in the inclusion of a broader set of social innovation examples, such as public private partnerships (39).

In summary, this framework is a starting point to further the discourse, teaching, research and practice of PHEI. This is an emerging field within public health, and more data is needed to better understand and characterize its nuances, opportunities, and limitations. In keeping with the cross-disciplinary nature of PHEI, this data and understanding can only be achieved through cross-sectoral collaboration of entrepreneurs, intrapreneurs, researchers and academics, funders, communities, government, the technology and private sector, and other diverse stakeholders.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

TC conducted the scoping review, analyzed results, developed and tested framework, conducted focus groups and interviews, and wrote manuscript.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author gratefully acknowledges Martin Williams, Leslie Curry, Mark Schlesinger, Kate Nyhan, and Victoria Ellison for their input and support. The following authors and practitioners provided feedback on the PHEI framework: Ross Shegog, Elisabeth Becker, Cameron Lister, Peter Jacobson, Bina Shrimali, Howard Koh, Rebecca Onie, Trishan Panch, Rushika Fernandopulle, Mona Mowafi, Richard Siegrist, and Nalaka Gooneratne. Special thanks to Elisabeth Becker for help assimilating entrepreneurship literature and to Olav Sorenson for guidance on the literature.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.593553/full#supplementary-material

1. Becker ERB, Chahine T, Shegog R. Public health entrepreneurship: a novel path for training future public health professionals. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:89. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00089

4. Yock PG, Zenios S, Makower J, Brinton TJ, Kumar UN, Watkins FTJ, et al. Biodesign: The Process of Innovating Medical Technologies. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2015). doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316095843

5. Felin T, Gambardella A, Stern S, Zenger T. Lean startup and the business model: experimentation revisited. Long Range Planning. Long Range Plann. (2019) 53:2. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2019.06.002

7. Dees JG. The Meaning of “Social Entrepreneurship.” (2001). Available online at: https://centers.fuqua.duke.edu/case/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/03/Article_Dees_MeaningofSocialEntrepreneurship_2001.pdf (accessed March 20, 2021).

8. Jacobson PD, Wasserman J, Wu HW, Lauer JR. Assessing entrepreneurship in governmental public health. Am J Public Health. (2015) 105:S318–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302388

9. Erwin PC, Brownson RC. The public health practitioner of the future. Am J Public Health. (2017) 107:1227–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303823

10. Hernández D, Carrión D, Perotte A, Fullilove R. Public health entrepreneurs: training the next generation of public health innovators. Public Health Rep. (2014) 129:477–81. doi: 10.1177/003335491412900604

11. Shrimali BP, Luginbuhl J, Malin C, Flournoy R, Siegel A. The building blocks collaborative: advancing a life course approach to health equity through multi-sector collaboration. Matern Child Health J. (2013) 18:373–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1278-x

12. Vechakul J, Shrimali BP, Sandhu JS. Human-centered design as an approach for place-based innovation in public health: a case study from Oakland, California. Matern Child Health J. (2015) 19:2552–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1787-x

13. Choucair B, Bhatt J, Mansour R. A bright future. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2015) 21:S49–55. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000140

14. Martin WM, Mazzeo J, Lemon B. Teaching public health professionals entrepreneurship: an integrated approach. J Enterpr Cult. (2016) 24:193–207. doi: 10.1142/S0218495816500084

15. Jacobs JA, Jones E, Gabella BA, Spring B, Brownson RC. Tools for implementing an evidence-based approach in public health practice. Prev. Chronic Dis. (2012) 9:E116. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110324

16. Lister C, Payne H, Hanson CL, Barnes MD, Davis SF, Manwaring T. The public health innovation model: merging private sector processes with public health strengths. Front Public Health. (2017) 5:192. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00192

17. Tucker JD, Fenton KA, Peckham R, Peeling RW. Social entrepreneurship for sexual health (SESH): a new approach for enabling delivery of sexual health services among most-at-risk populations. PLoS Med. (2012) 9:e1001266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001266

18. Ness RB. Tools for innovative thinking in epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. (2012) 175:733–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr412

19. Fisher JS. Public health accreditation board's innovation center continues the mission to advance the quality and performance of health departments. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2018) 24:S117–9. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000726

20. Locke R, Castrucci BC, Gambatese M, Sellers K, Fraser M. Unleashing the creativity and innovation of our greatest resource—the governmental public health workforce. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2019) 25:S96–102. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000973

21. Samet JM, Ness RB. Epidemiology, austerity, and innovation. Am J Epidemiol. (2012) 175:975–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws035

22. Hatef E, Sharfstein JM, Labrique AB. Innovation and entrepreneurship. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2018) 24:99–101. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000665

23. Davis JA, Marino LD, Vecchiarini M. Exploring the relationship between nursing home financial performance and management entrepreneurial attributes. Adv Health Care Manag. 4:147–65. doi: 10.1108/S1474-8231(2013)00000140011

24. Lumpkin GT, Dess GG. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manage. Rev. (1996) 21:135–72. doi: 10.5465/amr.1996.9602161568

25. Rauch A, Wiklund J, Lumpkin G, Frese M. Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneursh. Theor. Pract. (2009) 33:761–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00308.x

26. Fung M, Simpson S, Packer C. Identification of innovation in public health. J Public Health. (2010) 33:123–30. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq045

27. Farmer J, Kilpatrick S. Are rural health professionals also social entrepreneurs? Soc Sci Med. (2009) 69:1651–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.003

28. Wei-Skillern. Networks as a Type of Social Entrepreneurship to Advance Population Health. Preventing Chronic Disease (2010).

29. Orton S, Umble K, Zelt S, Porter J, Johnson J. Management academy for public health: creating entrepreneurial managers. Am J Public Health. (2007) 97:601–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.082263

30. Fraser M, Castrucci BC. Beyond the status quo. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2017) 23:543–51. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000634

31. Dalton CB. Enablers of innovation in digital public health surveillance: lessons from Flutracking. Int Health. (2017) 9:145–7. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihx009

32. Niccum BA, Sarker A, Wolf SJ, Trowbridge MJ. Innovation and entrepreneurship programs in US medical education: a landscape review and thematic analysis. Med Educ Online. (2017) 22:1360722. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2017.1360722

33. DeSalvo KB, Wang YC, Harris A, Auerbach J, Koo D, O'Carroll P. Public health 3.0: a call to action for public health to meet the challenges of the 21st century. NAM Perspect. (2017) 7:E78. doi: 10.31478/201709a

34. Piot P. Innovation and technology for global public health. Glob Public Health. (2012) 7:S46–53. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2012.698294

35. Leischow SJ, Milstein B. Systems thinking and modeling for public health practice. Am J Public Health. (2006) 96:403–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.082842

36. Gunasekeran DV, Tham YC, Ting DSW, Tan GSW, Wong PTY. Digital health during COVID-19: lessons from operationalising new models of care in ophthalmology. Lancet Dig Health. (2021) 3:E124–34. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30287-9

37. Peek N, Sujan M, Scott P. Digital health and care in pandemic times: impact of COVID-19. BMJ Health Care Informat. (2020) 27:e100166. doi: 10.1136/bmjhci-2020-100166

38. Pérez Sust P, Solans O, Fajardo JC, Medina Peralta M, Rodenas P, Gabaldà J, et al. Turning the crisis into an opportunity: digital health strategies deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2020) 6:e19106. doi: 10.2196/19106

Keywords: design thinking, systems thinking, social enterprise and social entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship, government intrapreneurship, public health entrepreneurship, public health innovation

Citation: Chahine T (2021) Toward an Understanding of Public Health Entrepreneurship and Intrapreneurship. Front. Public Health 9:593553. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.593553

Received: 10 August 2020; Accepted: 08 March 2021;

Published: 09 April 2021.

Edited by:

Harshad Thakur, National Institute of Health and Family Welfare, IndiaReviewed by:

Wim Naudé, RWTH Aachen University, GermanyCopyright © 2021 Chahine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Teresa Chahine, dGVyZXNhLmNoYWhpbmVAeWFsZS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.