- 1Faculty of Medicine, Damascus University, Damascus, Syria

- 2Faculty of Medicine, Aleppo University, Aleppo, Syria

- 3Department of Experimental Surgery, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Background: Lockdown restrictions due to COVID-19 have affected many people's lifestyles and ability to earn a living. They add further distress to the lives of people in Syria, who have already endured 9 years of war. This study evaluates distress and the major causes of concerns related to COVID-19 during the full lockdown.

Methods: Online questionnaires were distributed using SPTSS, K10, and MSPSS which were used with other demographic, war- and COVID-19-related questions that were taken from The (CRISIS) V0.1 Adult Self-Report Baseline Form.

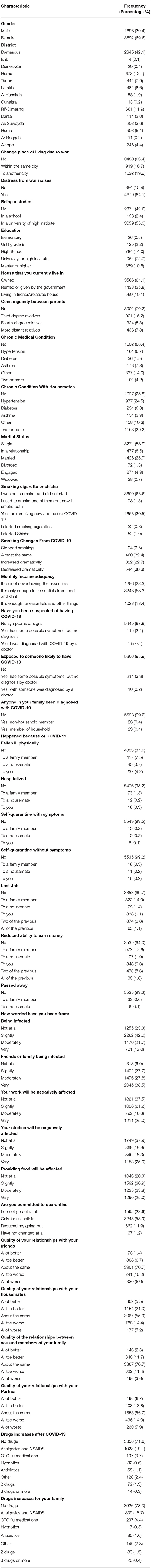

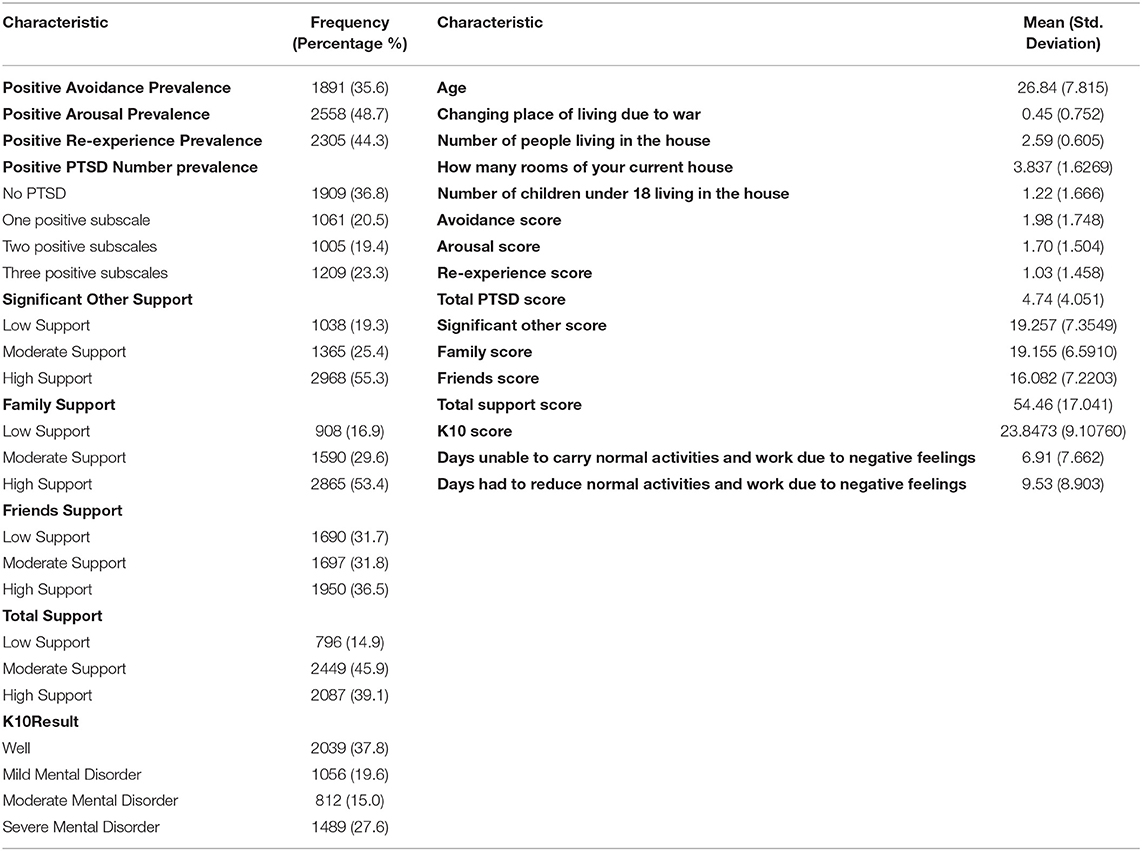

Results: Our sample included 5,588 with the mean age of 26.84 ± 7.815 years. Of those, only one case of COVID-19 was confirmed. Over 42.7% had two or more positive PTSD symptoms, 42.6% had moderate or severe mental disorder, but only 14.9% had low social support. Higher PTSD and K10 scores overall were seen in female participants and with most of war variables (P < 0.05). Relationships with the partner being negatively affected and distress from a decline in ability to work and provide food were the most prominent.

Conclusions: The indirect effects of COVID-19 are far more than that of the pathogen itself. A reduced ability to earn and to provide food were the main concerns indicated in this study. Relationships deteriorated in participants with high K10 and PTSD scores who also had more symptoms and used more hypnotics in the last four weeks. Smoking patterns were not related to K10 and PTSD. Social support played a role in reducing stress, but when relationships were affected, lower support was observed.

Introduction

Further to the ramifications of war which the Syrian population has been experiencing since 2011, the spread of the COVID-19 virus has created additional challenges. With the new restrictions imposed by the government in Syria, the country was in full lockdown despite having few confirmed cases; all non-essential business, schools, universities, parks, mosques, churches, and other areas of common gathering were closed. A forced lockdown was announced from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. on weekdays and 12 p.m. to 6 a.m. on weekends. This potentially made it even harder for Syrians to cope with the underlying stress caused by years of insecurity, fear, and loss. While institutions and governments around the world designated specific hotlines, projects and support platforms for citizens coping with the stress of changes to their life brought by the pandemic (1–4), such measures in Syria did not take place. The reason for this could be attributed to the stigma regarding mental health, which is highly prevalent in most developing countries (5) but also to the difficult nine years of war the country had been experiencing, making any mental health programs now appear unreasonably out of context.

Previous literature on outbreaks has focused on the physical health consequences of the disease and less on the mental health sequela that social distancing can generate. However, disasters, whether they are natural, man-made or industrial, have an impact on the social structure of the community and therefore strongly impact the mental health of these communities (5). This impact can cause and aggravate medical conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, substance abuse, and a broad range of maladaptive and harmful behaviors such as child and domestic abuse (6). For instance, after the hurricane of Maria in Puerto Rico, the country had 25 suicides every month during the three months following the hurricane and 19 suicides per month in the eight following months, which were an increase from the baseline before the hurricane (7). As for PTSD, it was diagnosed in 30–40% of people surviving a disaster compared to the 8% prevalence in the general population (7).

Studies have tried to understand the impact of disease outbreaks on the mental health of those affected, proving that survivors of diseases, like SARS, can suffer from elevated stress and worry, even one year after the disease outbreak (8). While it is very important to understand the ramifications of disease outbreaks on the mental health of the community affected directly by the disease, the impact of the crisis goes beyond those who acquire the disease and affect even the healthiest members of the community (9). Some risk factors that make individuals more prone to have impaired wellbeing and quality of life during COVID-19 have been identified such as fears of infection, being lonely, boredom, frustration, and pervasive anxiety while others have been identified as protective factors including resilience and social support (10). These risk factors may also be related to negative outcomes such as suicide. It is suggested that these aspects might be from neglect and abuse since childhood (11).

Our study aims to understand that impact in the context and background of war and evaluates how disease outbreaks and war have significant consequences on mental health. In this study, we assess mental health during COVID-19 by asking participants direct questions related to the outbreak and its effect on life, and indirectly by measuring post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), social support, and mental distress. This study used the same methods adopted by a previous study, conducted one year before to allow comparisons (12). We hypothesize that PTSD symptoms and mental distress from living in war-torn Syria have increased during COVID-19 and that social support minimized it. We also speculated that COVID-19 related variables are similar to the effects of war on mental health.

Methods

Sampling

We conducted a cross-sectional study across Syria from April 6 to April 13, 2020. Online surveys were distributed in Arabic to participants from several Syrian governorates. The study only included participants who were living within Syria. Participants who answered key questions and lived in Syria during COVID-19 lockdown and generally in Syria in the last 9 years were included. The questionnaires were posted online twice each day at 10 a.m. and 10 p.m. in online Social Media groups that were concerned with different topics to cover the widest possible population.

Questionnaires

Socioeconomic Status (SES)

Socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed by asking whether the place where the participants lived was owned, rented, or whether they were living with friends or accommodation provided by the government. We also asked whether the family income was adequate for essentials, or allowed them to buy more items.

Screening for Mental Disorder

An Arabic version of Kessler 10 + LM (K10 + LM) was used to screen and measure the severity of psychological distress (13–15). K10 is a self-reported measure that enables the assessment of anxiety and depression in the last 4 weeks, with scores ranging from 10 to 50, and each question has five possible responses. The answers score from one when replying “none of the time” to five when replying “all of the time.” Higher scores are indicative of higher levels of psychological distress. The severity of mental distress is divided into four levels: scores 10–19 will be likely well, scores 20–24 will likely have a mild disorder, scores 25-29 will likely have a moderate disorder, and finally scores 30 and above will likely have a severe disorder.

Social Support

We used the Arabic version of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (16, 17) to assess the social support from friends, significant others, and family with four questions for each source. We used total mean scores (not means of each individual question) for comparisons with other variables. The norms will likely vary according to culture, nationality, age, and gender. The mean scores for the total or individual subscale are divided into 3 categories: 1 to 2.9 to be considered low support, 3 to 5 to be considered moderate support, and 5.1 to 7 to be considered high support.

PTSD

The Screen for Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms (SPTSS) tool of diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM) IV was used. It contains three clusters of avoidance, arousal, and re-experience. The first two responses of “Not at all” and “1 or 2 times” represent the score 0 and the other responses represent the score 1. When scoring three or more on avoidance, two or more on arousal, and one or more on re-experience, that cluster is considered positive. Although it is based on DSM IV, it is somewhat close to what is used in the International Classification of Disease 11 (ICD-11) criteria and is reliable when screening for PTSD. SPTSS is a brief screening method that is not based on a single trauma model which helps to identify individuals who have high levels of SPSS symptoms and are not linked to a specific event.

COVID-19 Questions

We used questions that involved COVID-19 from The Coronavirus Health Impact Survey (CRISIS) V0.1 Adult Self-Report Baseline Form (18), and we translated them and added extra questions. CRISIS is a self-reported baseline current form, and we only used some of the questions. Questions involved Health/Exposure status in the last 2 weeks, distress from COVID-19, feeling new symptoms that could not be attributed to allergies, distress from different aspects, smoking, relationships, and earning money being affected. These questions with their answers are demonstrated in Table 1.

Other Questions

Basic demographic questions were included on gender, age, educational level, whether they were currently a student, the governorate where they lived, and whether they had consanguineous parents. We asked whether they were distressed from war noises or having to change their place of living due to war and the number of these changes experienced.

Definitions

Consanguinity was defined as third-degree consanguinity when the parents were first cousins, and fourth-degree consanguinity when the parents were second cousins, or second cousins once removed. We defined IT work type as engineering around a computer, IT, web design, or communication engineering that required programming. We defined engineering work types as civil, electrical/mechanical engineering, and architecture.

We defined a retail worker as a job selling costumers products, either in stores, or being a salesman. Medical engineering was part of “other health workers.” Working in television, radio, entertainment, or journalism were categorized in the “media” work type. We defined “office” work type as any work in an office either in a company or private practice such as accounting and law. A photographer or any job involving music, painting, or design except for web design was included in the “Art and music” category.

Data Process

Data were processed using IBM SPSS software version 26 for Windows (SPSS Inc., IL, USA). Chi-square, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), linear regression, and independent t-tests were performed to determine the statistical significance between the groups. Pearson correlation was also calculated. Through the same software, odds ratios (ORs) and the 95% confidence intervals for the groups were calculated using Mantel–Haenszel test. Values of <0.05 for the two-tailed P values were considered statistically significant.

Results

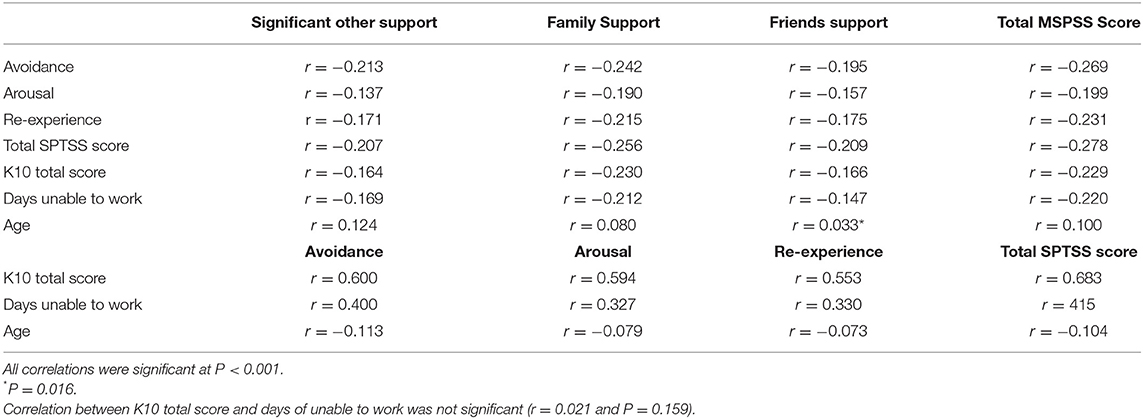

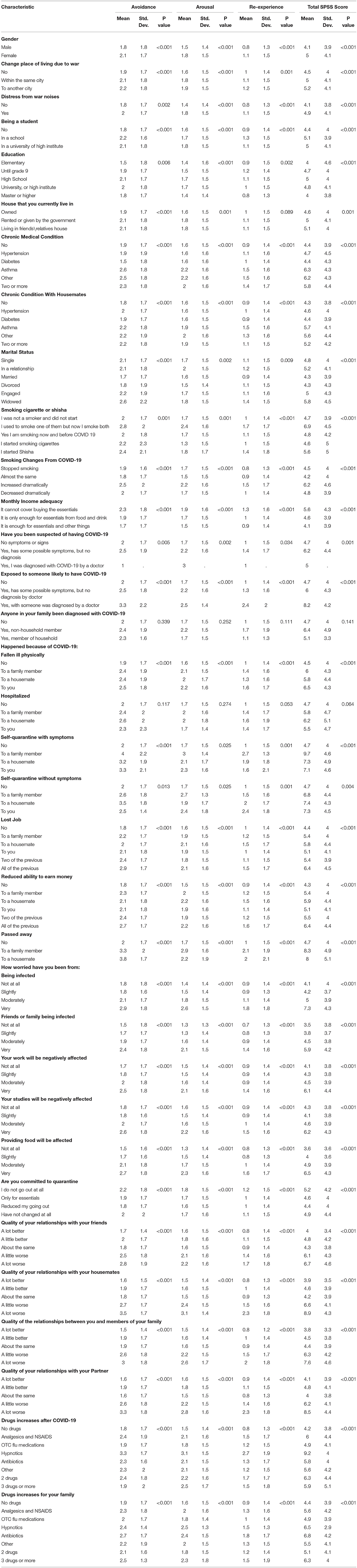

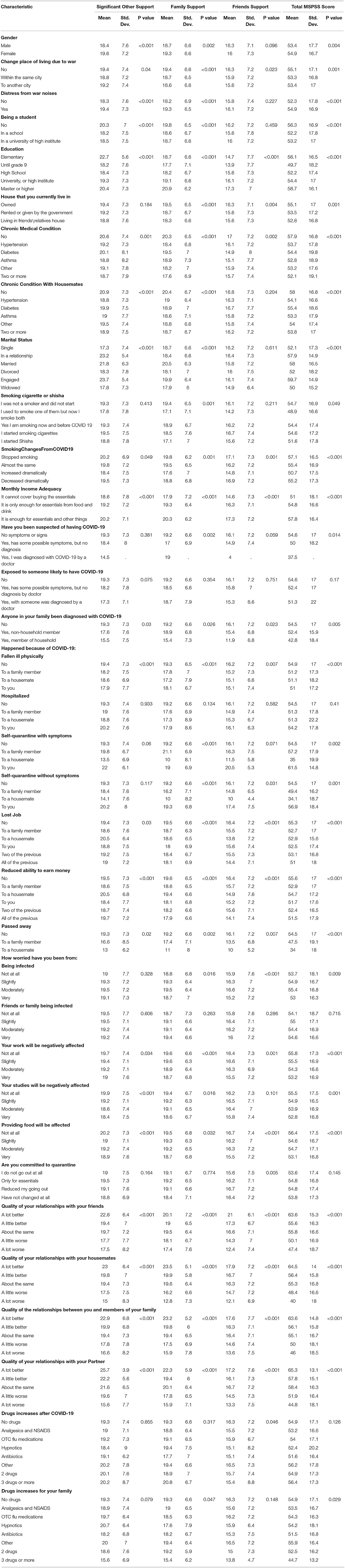

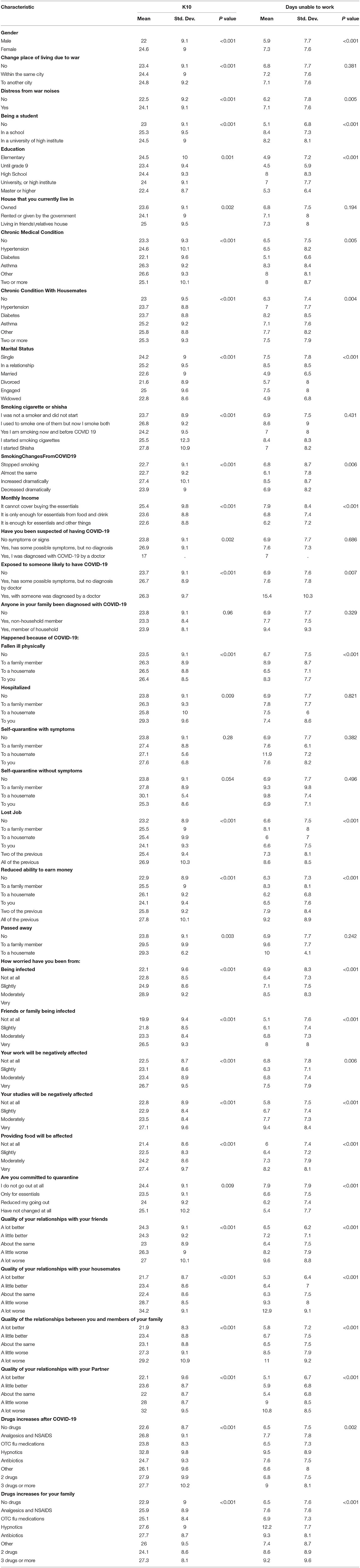

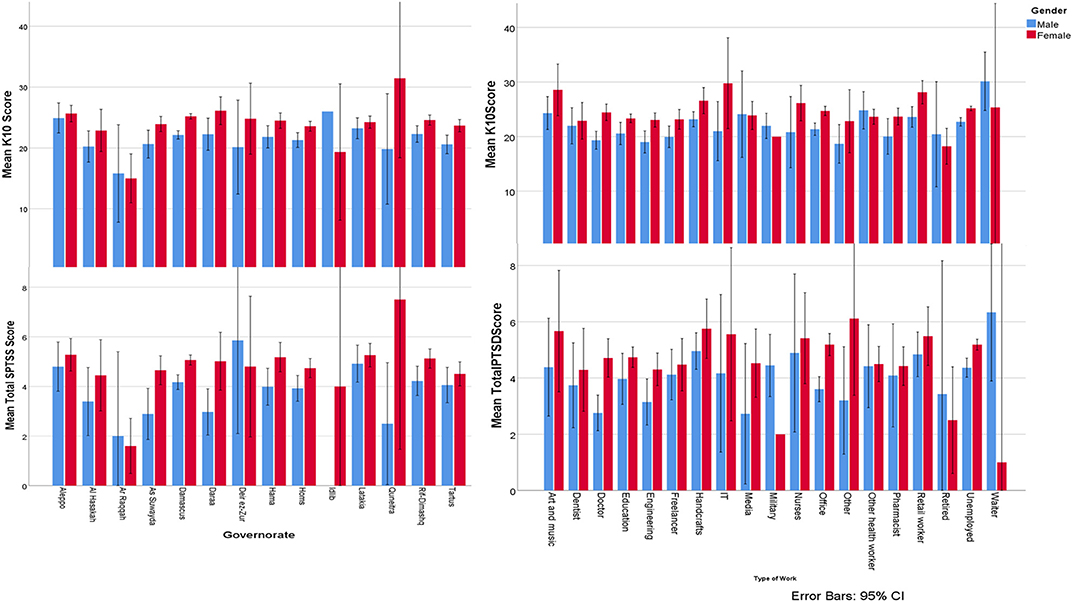

Our sample comprised 5,588 participants from all across Syria with 3,892 (69.6%) female participants. The mean age was 26.84 ± 7.815 years. In the sample, 37.8% were well according to K10, but 27.6% had a probable severe mental disorder. Approximately, 37% did not report positive SPTSS items, and 23.3% met the criteria for probable PTSD. Characteristics of subjects, their responses to COVID-19 questions, war variables, and other nominal variables are demonstrated in Table 1. Age, PTSD, MSPSS, K10 scores, and results on other war and numeral variables are demonstrated in Table 2. COVID-19 questions, war, and other variables associated with SPTSS items and total scores are demonstrated in Table 3 with each social support and total MSPSS support scores demonstrated in Table 4, and K10 + LM scores and days demonstrated in Table 5. PTSD, and K10 scores distributions in governorates by gender and according to the type of work are demonstrated in Figure 1. The associations between PTSD clusters, K10 scores, and social support are demonstrated in Table 6.

Table 3. SPTSS items and total mean scores and correlations with COVID-19 and war variables along with other variables.

Table 4. MSPSS items and total scores mean scores and correlations with COVID-19 and war variables along with other variables.

Table 5. K10 scores, days unable to work and days of reduced work and correlations with COVID-19 and war variables along with other variables.

Figure 1. SPTSS and K10 scores by gender distribution according to the type of work and governorates.

PTSD

Avoidance, arousal, and total PTSD scores differed according to governorate (P = 0.009, P = 0.060, and P = 0.020, respectively). These PTSD scores differences are demonstrated in Figure 1. All PTSD items did not correlate with consanguinity (P > 0.05). PTSD items and total scores differed according to governorate and type of work or being unemployed (P < 0.05), with total PTSD score differences having (P < 0.001) and demonstrated in Figure 1.

Regressing gender, educational level, rented housing, type of work, having a chronic medical condition, marital status, monthly income adequacy, distress from war noises, and changing place of living due to war on PTSD scores using forward linear regression was significant (P < 0.001) with having a chronic condition (R2 = 3.2%), gender (R2 = 1.4%), monthly income adequacy (R2 = 1.3%), marital status (R2 = 0.3%), changing place of living due to war and educational level (R2 = 0.2%) contributing to the variance. SPTSS item score correlations are demonstrated in Table 3.

MSPSS

Family, friends, significant other, and total support were significantly correlated with the type of work and governorate (P < 0.001), but with consanguinity (P > 0.05).

Regressing gender, educational level, rented accommodation, type of work, having a chronic medical condition, marital status, monthly income adequacy, distress from war noises, and changing place of living due to war on total MSPSS score using forward linear regression was significant (P < 0.001), with social status (R2 = 2.4%), monthly income adequacy (R2 = 1.8%), having a chronic medical condition (R2 = 1.3%), and educational level (R2 = 1%) while living in rented accommodation, type of work, and distress from war noises (R2 = 0.2%) and (P < 0.05) contributing to the variance.

K10

K10 had no association with consanguinity (P > 0.05). K10 total score was different according to governorate and type of work or being unemployed (P < 0.05), with total PTSD score differences having (P < 0.001) and demonstrated in Figure 1.

When Regressing gender, educational level, rented accommodation, type of work, having a chronic medical condition, marital status, monthly income adequacy, distress from war noises, and changing place of living due to war on total K10 score by using forward linear regression, (P < 0.001) for gender (R2 = 2.2%), and having a chronic condition (1.7%), monthly income adequacy (R2 = 0.8%), and social (R2 = 0.6%) while change place of living due to war (R2 = 0.4%) and educational level (R2 = 0.3%) for (P < 0.05). When using forward linear regression on total days of not being able to work with the same previous variables, (P < 0.001) for the type of work (R2 = 1.5%), gender (R2 = 0.8%), marital status (R2 = 1%), having a chronic medical condition (R2 = 0.8%), and monthly income adequacy (R2 = 0.6%).

COVID-19 Variables

When regressing gender, educational level, rented accommodation, type of work, having a chronic medical condition, marital status, monthly income adequacy, distress from war noises, changing place of living due to war, along with other COVID-19 variables of distress from losing the job, decreased income, passing away, the distress of being infected or a family member, distress of the job, studies, and food being affected on total SPTSS score by using forward linear regression, (P < 0.001) for the distress that the ability to provide food will be affected (R2 = 8%), distress from friend or family being infected (R2 = 2.6%), having a chronic condition (R2 = 1.9%), studies being affected (R2 = 1.6%), gender (R2 = 1.4%), job being affected (R2 = 1%), and passing away (R2 = 0.6%) while losing their job, being infected (R2 = 0.4%), and educational level [R2 = 0.2%, P < 0.05].

When regressing the same previous variables on total MSPSS score, (P < 0.001) for social status (R2 = 3.3%), monthly income adequacy (R2 = 1.6%), having a chronic condition (R2 = 1%), passing away (R2 = 0.8%), and educational level (R2 = 0.7%) while decreased income, type of work, and distress from work noise [R2 = 0.3%, P < 0.05]. When regressing the same previous variables on total K10 score with the same previous variables, (P < 0.001) for the distress that the ability to provide food is affected (R2 = 6.6%), gender (R2 = 2.5%), studies being affected (R2 = 1.7%), a friend or family being infected (R2 = 1.3%), having a chronic medical condition (R2 = 1%), and losing their job (R2 = 0.7%) while job being affected (R2 = 0.3%), educational level, distress being infected and passing away [R2 = 0.2, P < 0.05). When regressing the same previous variables on total days of not being able to work with the same previous variables, (P < 0.001) for the distress that studies will be affected (R2 = 3%), gender (R2 = 1%), the distress of food provision being affected (R2 = 0.9%), and type of work (R2 = 0.8%), while having a chronic medical condition (R2 = 0.6%), marital status (R2 = 0.3%), and decreased income (R2 = 0.4%), and educational level (R2 = 0.3%) for (P < 0.05).

No significant difference between gender and smoking changes in lockdown (P > 0.05). However, female participants felt more distress from war noises, more symptoms in the last two weeks, worried more than a friend or member of their family might have it, worried less that job will be affected or the ability to provide food will be affected, committed more to lockdown, their relationships worsened less with friends but more with family in the house and other family members, and took more medication than male participants (P < 0.05). No significant difference between gender in the relationship with partner or studies being affected (P > 0.05).

Being single was correlated with decreasing amount smoked in lockdown more (P < 0.011) and was correlated with less distress from war (P < 0.001). Being married was correlated with less distress of family or friend having COVID-19 when compared to being single (P < 0.001), but with more distress of job being affected (P = 0.009). There was no significant difference in distress about not being able to provide food during the COVID-19 pandemic and being single or married (P > 0.05).

Younger ages were insignificantly correlated with being distressed from acquiring COVID-19 (P = 0.082), significantly correlated with being distressed that a family may have it, a job affected, studies, and providing food being affected from COVID-19 (P < 0.05). Relationships with friends was more stable in older ages as in the younger ages they tended to improve or deteriorate (P < 0.001) while the relationship with housemates was not affected dramatically Younger participants overall their relationship deteriorate more frequently (P < 0.001). Moreover, the relationship with other family members and partners improved more frequently in the older ages (P < 0.001).

Discussion

Our study found that 1,891 (35.6%) participants had avoidance symptoms, 2,558 (48.7%) had arousal symptoms, 2,305 (44.3%) had re-experience symptoms, 1,005 (19.4%) had two PTSD symptoms, 2,301 (42.6%) had moderate to severe mental disorder, and 706 (14.9%) had low social support. Furthermore, female participants were found to have higher avoidance, arousal, re-experience, and mental disorder (K10) scores despite having higher social support scores. Moreover, being distressed from war noises, changing their place of living due to war, being a university or school student, not having an adequate monthly income, and most COVID-19 worries were associated with increased SPTSS and K10 scores and a decreased social support score. However, when regressing to determine the most significant contributing factors, we found that distress about providing food was the main contributing factor to the high SPTSS and K10 scores followed by distress from friends or family being infected, studies being affected from COVID-19, their job being affected from COVID-19, and gender. Social status and monthly income adequacy were the highest contributing factors to having low social support. Interestingly, no factors related to war were found to be significant when using the regression model.

COVID-19

This study assessed the psychological distress caused by the lockdown, and the new social and financial challenges caused by the pandemic, rather than by the illness itself, as <10 cases were confirmed in Syria at the time of the study. Our results show that psychological distress and PTSD symptoms are more common in participants with weak social support, problems at work, and who face challenges in the provision of food. Although our study showed a decrease in the overall frequency of smoking in both genders, there was no significant change in smoking habits among genders This can be explained by an increase in the cost of tobacco during the lockdown or could because of warnings of the effects of smoking on COVID-19.

Regular habits and war exposure in Syria were found to be related to unusual exposures to different substances (19). This exposure has led to an increase in different medical conditions compared to other countries such as allergic rhinitis (20) and laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (21), and both were related to distress from war noises.

Regarding familial relationships, almost half of the participants reported a difference in the relationship with their housemates but over 70% did not report a change in the relationship with other family members and friends.

PTSD, MSPSS, and K10 With COVID-19

Our Study

The provision of food during the lockdown was a big stressor identified by the participants, associated with higher SPTSS and K10 scores. Higher PTSD and mental disorder scores were observed in subjects with a deteriorated relationship with their family, housemates, and friends. This could be from the impact of reduced supports for mental health or from participants with higher PTSD and mental disorder scores suffering from more fragile relationships.

Although participants who tested positive for COVID-19 were few, higher PTSD and mental disorder scores were seen amongst them and their family members. A quarter of the participants did not report having flu-like symptoms but those who had symptoms had not been diagnosed. Higher scores of PTSD and mental distress were also observed in subjects who were self-isolated when asymptomatic compared to an asymptomatic family member who had not. Higher scores were seen when a housemate's ability to earn money was affected, more than when a family member's ability to earn money was affected. This could be explained by the fact that female participants comprised over two-thirds of our sample, and in Syria, a large number of women rely on their housemates to earn money.

Lower PTSD and mental disorder scores were observed in those that ignored lockdown instructions and were able to go out and buy household essentials. Patients with higher scores reported using hypnotics more frequently. Interestingly, social support decreased in participants who did not smoke or used to smoke and commenced using shisha which could be from this habit affecting housemates or the irritability from ceasing cigarette smoking. Higher social support was found in participants with relationships not being affected or improved in the lockdown while higher PTSD scores were seen in participants whose relationships deteriorated with their partners.

Fewer working hours being affected from mental distress were observed in married participants which could be explained by schools being closed and parents having to stay home to look after their children. Higher mental disorder scores and fewer working days being affected from mental distress were observed in participants who increased their smoking habits. Furthermore, the higher the K10 score, the more symptomatic the participants became. Interestingly, subjects with decreased working hours had higher social support and therefore a better relationship status. Higher PTSD scores were observed with higher mental disorder scores, and more days of being unable to work with correlations of (r = 0.682), and (r = 0.415), respectively. Interestingly, mental disorders scores and days of being unable to work had an insignificant correlation (P = 0.159).

Other Studies

The nature of COVID-19 required new methods to collect data as it can be expensive to safely collect data from a large population. The impact that the pandemic has is still uncertain, which could cause anxiety, worry, and even despair (22). Internet-based questionnaires proved to be very effective during the pandemic in many countries where specific questionnaires were developed for this purpose, for example in Italy (23).

Many studies have also found that COVID-19 had severe effects on mental health. Studies from Italy indicated that COVID-19 was linked to anxiety, distress, and symptoms of PTSD (24, 25). The lockdown also affected sleep quality (24). An association was found with general anxiety, and depression in Ireland (26). Another study from Hong Kong found that around a quarter of the population declared that their mental health got worse during the pandemic. Most of the worries were from being infected, not having sufficient masks, and being bothered when not being able to work from home. Interestingly, an association with a previous event was established as participants who did not have experience with the previous SARS outbreak had a worse mental health status (27).

One study among adults in the USA found that COVID-19-related experience was associated with an odds ratio higher than 3 of having probable anxiety and depression and the stress from COVID-19 could predict a variance of (R2 ≥ 30) with anxiety and depression (28). However, a study in Spain demonstrated that the levels of symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress were low at the beginning, but these levels rose after staying at home (29). Nevertheless, a study in the UK found that the early stages of the pandemic were associated with a modest increase of mental health problems including anxiety, depression, and trauma symptoms (30).

PTSD, MSPSS, and K10 With Other Variables

As PTSD needs at least 4 weeks to develop, we used the SPTSS score as a probable indicator rather than cut-off points. Having certain medical conditions was associated with higher scores in SPTSS and K10, especially when having a family member with chronic medical conditions like asthma. This may indicate the need to address the psychological effect of chronic medical conditions, not only on the affected person but on other members of their household. Participants who did not own the house they lived in and had an inadequate monthly income had higher SPTSS and K10 scores which indicates the role of financial burden. Avoidance scores were higher when losing a housemate while other PTSD symptoms scores increased more when participants had lost a family member. This could be explained by the stereotype brought to the widowed woman in the community that makes her feel isolated. Another theory could be that the morale of the widowed dropped, as losing a partner is considered a major trauma and the possibility of losing the social and financial support of the partner is also significant.

Mental distress and PTSD have been identified in many studies to be more common in female participants, particularly from war noises (12). Distress was also more common in female schoolchildren aged 15 years and over, but male schoolchildren had more tendency to smoke (31), which was similar to adults in Syria (32). The high prevalence of PTSD and severe mental distress are not novel findings and the prevalence found in our study was lower than a previous study that used the same materials and same scales conducted a year ago (12). The previous study found that 60.8% of the sample had two positive PTSD clusters or more according to DSM IV and 61.2% of the sample had moderate to severe mental disorders according to K10. Our study findings were also lower than those of a study on Syrian schools in Damascus (31) in which PTSD prevalence was found to be 53%. This may indicate that war may have a more severe effect than the pandemic.

Many risk factors for psychological distress were identified that were associated with COVID-19 such as female gender, being younger than 50 years of age, being in direct contact with someone who was infected by COVID-19, having a high risk of acquiring COVID-19, the presence of children at home, low income, having previous medical conditions in them or with others and being uncertain about the risk of contagion (25, 26, 30). However, despite the finding that psychological distress is associated with younger age, being 65 years or older was associated with more severe anxiety related to COVID-19 (26). In Turkey, a neighboring country to Syria, it was found that being female, living in an urban place, and having a previous psychiatric problem were associated with anxiety, compared to depression which was only associated with living in an urban place. However, being female, having a chronic medical condition, and having psychiatric disorders were associated with anxiety (33).

Limitations

As PTSD needs four weeks to develop (according to the strict definition), we used scoring symptoms rather than diagnosing cut-off, which is perhaps more indicative of an acute stress disorder. This study was online and mainly involved participants who had enough free time to fill in the survey which may neglect the truly affected population. Furthermore, the days of fewer productivity questions in K10-LM may not be fully understood for some participants and therefore were not mentioned in the discussion. This study used a questionnaire and is not based on medical diagnosis, which would have been more accurate. No clinical examination by professionals was conducted and therefore determining if the effect of COVID-19 was truly more severe than war is not conclusive.

The sampling method, the use of an online questionnaire, the sample size compared to the population, and the subjectivity of the used method were the main source of biases in our study.

Conclusion

Although full lockdown can be an effective method for preventing the spread of pandemic diseases such as COVID-19, this study indicates that it causes severe distress. This is reflected in mental distress and PTSD symptoms even in countries that were originally affected by wars, as the restrictions of lockdowns can obstruct lifestyle and the ability to earn and provide daily food. Social support has a role and to some extent reduces the amount of stress either on PTSD or distress from COVID-19. Being widowed, low SES, low social support, and living in rented accommodation were associated the most with distress as the ability to earn and to provide food were the most common stressors. Having high K10 and PTSD scores were associated with having more symptoms of COVID-19 despite not being exposed to it. PTSD and severe mental distress were prevalent in the Syrian community due to the psychological effects of war in the previous 9 years. Positive PTSD clusters in this study were less prevalent compared to previous studies in Syria which may suggest that the first weeks of lockdown might reduce the stress. However, this study suggests that COVID-19 stress, mainly from the effect on the economy, might be more distressing than experiencing war.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

Informed consent was taken before participants completed the survey. Informed consent was also taken for using and publishing the data. Confidentiality was assured by not asking or publishing any data that may refer to the individual identity. The ethical aspects of the study were approved by Damascus University deanship (Damascus, Syria).

Author Contributions

AK: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, resources, validation, original draft, writing, review, and editing. AF: review and editing, original draft, investigation, software, and resources. LM: original draft, writing, review, and editing. AG: conceptualization, project administration, editing, and software. RA: project administration, investigation, and resources. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ANOVA, Analysis of variance; CI, Confidence Interval; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CRISIS, The CoRonavIruS Health Impact Survey; DSM, Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders; ICD, International Classification of Disease; K10, Kessler; MSPSS, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; NMIH, National Institute of Mental Health; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SES, Socioeconomic status; SPSS, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; SPTSS, Screen for Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms.

References

4. Kakaje A, Alhalabi MM, Ghareeb A, Karam B, Mansour B, Zahra B, et al. Rates and trends of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: an epidemiology study. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:6756. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63528-0

5. Makwana N. Disaster and its impact on mental health: a narrative review. J Family Med Prim Care. (2019) 8:3090–5. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_893_19

6. Neria YNA, Galea S Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychol Med. (2008) 38:467–80. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001353

7. César A, Alfonso M. PTSD and suicide after natural disasters. Psychiatric Times. (2018) 35:4. Available online at: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/ptsd-and-suicide-after-natural-disasters

8. Lee AM, Wong WJ, McAlonan GM. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry. (2007) 52:233–40. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200405

9. Galea S. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing. JAMA Intern Med. (2020) 180:817–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562

10. Serafini G, Parmigiani B, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Sher L, Amore M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. Int J Med. (2020) 113:531–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201

11. Pompili M, Innamorati M, Lamis DA, Erbuto D, Venturini P, Ricci F, et al. The associations among childhood maltreatment, “male depression” and suicide risk in psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Res. (2014) 220:571–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.056

12. Kakaje A, Al Zohbi R, Hosam Aldeen O, Makki L, Alyousbashi A, Alhaffar MBA. Mental disorder and PTSD in Syria during wartime: a nationwide crisis. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:2. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-03002-3

13. Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Aust N Zeal J Public Health. (2001) 25:494–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00310.x

14. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SLT, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. (2002) 32:959–76. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074

15. Palazón-Bru A, Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Zamorski MA, Colman I. The psychometric properties of the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) in Canadian military personnel. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0196562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196562

16. Zimet G. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) - Scale Items and Scoring Information. (2016).

17. Kazarian RMS. Validation of the Arabic translation of the Multidensional Scale of Social Support (Arabic MSPSS) in a Lebanese community sample. Arab J Psychiatry. (2012) 23:159–68. Available online at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2012-34151-008

18. The CoRonavIruS Health Impact Survey (CRISIS) V0.3. Adult Self-Report Follow Up Form. National Institute of Mental Health (NMIH). Available online at: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/dr2/CRISIS_Adult_Self-Report_Follow_Up_Current_Form_V0.3.pdf.

19. Kakaje A, Alhalabi MM, Ghareeb A, Karam B, Hamid A, Mansour B, et al. Breastfeeding and Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: Potential Leukemogenesis in Children in Developing Countries. Damascus. (2020). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-25489/v2

20. Kakaje A, Alhalabi MM, Alyousbashi A, Hamid A, Hosam Aldeen O. Allergic rhinitis and its epidemiological distribution in Syria: a high prevalence and additional risks in war time. BioMed Research International. (2020) 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2020/7212037

21. Kakaje A, Alhalabi MM, Alyousbashi A, Hamid A, Mahmoud Y. Laryngopharyngeal reflux in war-torn Syria and its association with smoking and other risks: an online cross-sectional population study. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:11. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041183

22. Stein MB. COVID-19 and anxiety and depression in 2020. Depression Anx. (2020) 37:302. doi: 10.1002/da.23014

23. Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Casagrande M. COVID-19 pandemic in the Italian population: validation of a post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaire and prevalence of PTSD symptomatology. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:11. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114151

24. Casagrande M, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Forte G. The enemy who sealed the world: effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Med. (2020) 75:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.011

25. Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Casagrande M. The enemy which sealed the world: effects of COVID-19 diffusion on the psychological state of the italian population. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:6. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061802

26. Hyland P, Shevlin M, McBride O, Murphy J, Karatzias T, Bentall RP, et al. Anxiety and depression in the Republic of Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. (2020) 142:249–56. doi: 10.1111/acps.13219

27. Choi EPH, Hui BPH, Wan EYF. Depression and Anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:10. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103740

28. Gallagher MW, Zvolensky MJ, Long LJ, Rogers AH, Garey L. The impact of Covid-19 experiences and associated stress on anxiety, depression, and functional impairment in American Adults. Cognitive Ther Res. (2020) 44:1043–51. doi: 10.1007/s10608-020-10143-y

29. Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Dosil-Santamaria M, Picaza-Gorrochategui M, Idoiaga-Mondragon N. Niveles de estrés, ansiedad y depresión en la primera fase del brote del COVID-19 en una muestra recogida en el norte de España. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. (2020) 36:4. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00054020

30. Shevlin M, McBride O, Murphy J, Miller JG, Hartman TK, Levita L, et al. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress and COVID-19-related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open. (2020) 6:6. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.109

31. Kakaje A, Zohbi RA, Alyousbashi A, Abdelwahed RNK, Aldeen OH, Alhalabi MM, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anger and mental health of school students in Syria after nine years of conflict: a large-scale school-based study. Pyschol Med. (2020). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-27218/v1. [Epub ahead of print].

32. Kakaje A, Alhalabi MM, Alyousbashi A, Ghareeb A, Hamid L. Smoking Habits in Syria and the Influence of War on Cigarette and Shisha Smoking. Syria. (2020).

Keywords: COVID-19, lockdown, psychological distress, posttraumatic stress disorder, mental disorders, conflict, developing country, Syria

Citation: Kakaje A, Fadel A, Makki L, Ghareeb A and Al Zohbi R (2021) Mental Distress and Psychological Disorders Related to COVID-19 Mandatory Lockdown. Front. Public Health 9:585235. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.585235

Received: 20 July 2020; Accepted: 22 February 2021;

Published: 26 March 2021.

Edited by:

Wulf Rössler, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Gianluca Serafini, San Martino Hospital (IRCCS), ItalyMaria Casagrande, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Kakaje, Fadel, Makki, Ghareeb and Al Zohbi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ameer Kakaje, YW1lZXIua2FrYWplJiN4MDAwNDA7aG90bWFpbC5jb20=; orcid.org/0000-0002-3949-6109

Ameer Kakaje

Ameer Kakaje Ammar Fadel

Ammar Fadel Leen Makki2,3

Leen Makki2,3 Ayham Ghareeb

Ayham Ghareeb Ragheed Al Zohbi

Ragheed Al Zohbi