- 1Language Center, College of Humanities, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana

- 2Family Health Care Nursing Department, School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 3Institute for Health and Aging, School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, CA, United States

Research has shown that music can be used to educate or disseminate information about public health crises. Grounded in the edutainment approach, we explored how songs are being used to create awareness about COVID-19 in Ghana, a sub-Saharan African country. YouTube was searched, and 28 songs met the study inclusion criteria. We conducted a thematic analysis of the song lyrics. Most lyrics were in English, Ghanaian Pidgin English, Akan, Ga, or Dagbani. Reflecting the multilingual population of Ghana, half of the songs contained three languages to convey their message, and only five songs were in one language. Eight themes emerged from the analysis: public health guidelines, COVID-19 is real and not a hoax, COVID-19 is infectious, prayer as method to stop the virus, emotional reaction and disruption of “everyday” activities; verbally expelling the virus, call for unity and collective efforts, and inspiring hope. We show that songs have the potential as a method for rapidly sharing information about emerging public health crises. Even though, it is beyond the scope of this study to draw conclusions about the reception and impact of songs on awareness and knowledge, the study shows that examining song lyrics can still be useful in understanding local attitudes toward COVID-19, as well as strategies for promoting preventive behaviors. We note that additional multidimensional efforts are needed to increase awareness among the general public about the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” related to the spread of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) that causes COVID-19. Shortly thereafter on March 12, 2020, the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic (1). Following these declarations and other reports about the emergence of a new severe respiratory infection, public health officials rapidly developed and deployed public health messages about the pandemic around the world. Over a short period of time, the general public was provided information about COVID-19 and guidance about how to mitigate spread of the virus (e.g., face coverings, washing hands, physical distancing). However, awareness (attitudes, knowledge) of COVID-19 differs across various parts of the world. For example, low awareness and misperceptions about COVID-19 were reported in some parts of the world, such as North America, Europe and Africa (2, 3). As a result, there have been urgent calls to find innovative ways to increase awareness about COVID-19 and help reduce the outbreak of this infectious disease (4, 5).

Ghana recorded its first two cases of COVID-19 on March 12, 2020 and cases have risen exponentially in the country to 13,717 as of June 20, 2020 (with 85 deaths), prompting presidential directives to increase awareness among citizens by creating and disseminating information on various preventive measures. These directives, mainly in English with direct translation in Ghanaian Sign Language, were disseminated on electronic and social media platforms. However, citizens who do not understand the national or official language must rely on other citizens to be accurately informed. As of April 25, 2020, the National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE), which could effectively educate citizens in every district using various indigenous Ghanaian languages, had been unable to do so due to lack of government funds (6). To compensate for the lack of funding, citizens were educated with regularly posted updates on the NCCE website and social media platforms (7). This strategy, however, does not address citizens who are more isolated and lack access to the internet or citizens who cannot read the official language.

Apart from the updates from the NCCE, some musicians in the country took personal initiatives to compose songs in local languages to educate the public about the disease. These songs were without any government or non-governmental organization support and were also not a part of an official campaign or intervention. Music plays an integral role in the culture of many African countries including Ghana. In addition to serving entertainment purposes, music highlights socio-cultural values and helps in the performances of daily routines. It is also used to recount history, and it forms a part of festivals, ceremonies related to rites of passage and other cultural functions (55). Music can be used as a vehicle for praise and criticism, especially in cases where authority figures are involved (8, 9). Also, it has the ability to alter knowledge, attitudes and behavior (10–13), and the potential to provide a way to access target audiences that could be missed with other methods of communication (14). Broadly speaking, music can play a pivotal role in helping increase awareness or gaining insight into different social issues.

Music forms a part of edutainment, a popular strategy that allows for educational messages to be embedded in entertainment media in order to positively change behaviors and attitudes (15). Edutainment is a combination of education and entertainment (57). It is a theory-based communication process which, according to Ganeshasundaram and Henley (52), “involves the design and implementation of media programs that deliberately incorporate persuasive, educational content in popular entertainment formats to influence audience knowledge, attitudes, behavioral intentions, and practices” (p. 311). This communication process is a tool for implicit persuasion as it is able to suspend disbelief and facilitate changes in the behavior of an audience (16, 17). Govender (53) asserts that in terms of facilitating a desired behavioral or social change, edutainment has been more innovative in Africa than in other parts of the world. As a result, some non-governmental agencies financially support programs and activities that engage members of a community and attempt to solve social problems through creative artistic processes that are receptive and entertaining (18).

Generally, edutainment health interventions are complementary to traditional public health interventions (18). Several studies have reported how songs and music can be used as a means of education and increasing awareness in public health context and clinical experience (12, 19–21, 50). Thus, the use of music to influence knowledge, attitudes and behaviors toward infectious diseases like COVID-19 is not a new phenomenon in Africa. In relation to HIV/AIDS and Ebola, for instance, research shows how popular artists in the region incorporated health-promoting messages and basic information about these diseases, and communicated preventative measures in their songs (14, 22–24). In 2000, a campaign dubbed “Stop AIDS: Love Life” involved a music video produced by Ghanaian musicians to increase awareness about HIV/AIDS in the country. The campaign was implemented by Johns Hopkins University and the Ghana Social Marketing Foundation. It was aimed at de-stigmatizing HIV/AIDS, encouraging compassionate care and support for people living with HIV/AIDS, and encouraging citizens to adopt safe sex behavior (25). Also, various studies document how popular musicians were commissioned by organizations such as WHO and UNICEF in 2014–2016 to compose prevention songs as a response to the Ebola outbreak in Liberia and other parts of Africa (21, 26).

Certain characteristics of songs, such as repetition and the capacity for involuntary recall, enhance the effectiveness of educational messages (27). These characteristics underpin reasons why, as earlier mentioned, HIV/AIDS and Ebola prevention messages were conveyed through songs in various parts of Africa (28–30). In Uganda, for example, music was recognized by healthcare workers as “a more localized and thus more effective medical intervention than outreach efforts in the form of lectures and seminars” ((29), p. 27). The assumption is that in African communities, the performance of songs can facilitate information dissemination and public debate on sensitive health topics (15). It is therefore not surprising that songs have been composed in Ghana and other African nations (e.g., Liberia, Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda, Cameroun, and Kenya) to educate people about the novel coronavirus (31). The purpose of this paper is to describe the content of song lyrics related to COVID-19 messaging and to highlight among other things the preventative measures embedded in them. The songs examined were composed by individual Ghanaian musicians and posted on their YouTube channels during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Setting

Ghana is located in West Africa, bordered on the west side by the Ivory Coast, and by the Atlantic Ocean in the south. According to recent census data, the population of Ghana is 29 million (32) with over 81 spoken languages (51). Four languages, including English, Akan, Hausa, and Ghanaian Pidgin English (GhPE), are the most common languages used for broad communication in the country (51).

Akan is the primary language spoken in the south (including the capital, Accra) and Hausa is the primary language spoken in the north (33). However, English is Ghana's official national language used in education, politics, government business, international trade, and technology (34–36). English is also the language used in print media and most electronic media programs. However, about eight of the written indigenous languages, including Akan, Ewe, Ga, Dagbani, Dagaare, and Gonja, are used for certain programs on radio and television (37, 38).

Data Extraction

YouTube [www.youtube.com], a music sharing website, was searched to identify coronavirus-related songs from Ghanaian musicians. following Google. According to the 2020 Alexa report, following Google [www.google.com], YouTube is the second of 500 top websites frequently used among Ghanaians (www.alexa.com/topsites/countries/GH). This makes YouTube the most popular and most patronized music and video sharing website in Ghana. The search was conducted from April 1, 2020 through May 30, 2020 with the following terms “Ghana coronavirus song,” “coronavirus song Ghana,” “coronavirus song from Ghana,” “coronavirus audio from Ghana,” and “coronavirus video from Ghana.” A total of 40 songs from both well-established and upcoming musicians were found. We included songs by Ghanaian artists in English or Ghanaian local language with any COVID-19 educative information. We excluded songs that only mentioned COVID-19 without providing any implicit or explicit public health message about the disease. An example can be retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EduNrGL5OwE.

The songs were searched and selected by three bachelor-prepared research assistants based on the exclusion and inclusion criteria. The selected songs were then reviewed by two PhD prepared researchers. Each song was assessed solely in terms of its lyrics and no other features such as tempo, rhythm, or mood. Non-English lyrics were translated and transcribed by language experts from Ghana. The lyrics were then reviewed to obtain information about key issues raised (themes), language(s) used, and references to specific symptoms and preventive measures. Of the 40 songs identified, 28 met the inclusion criteria.

Data Analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis to examine the lyrics of the selected songs. As a qualitative method, a thematic analysis allows for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterned themes within the songs. The four phases of analysis (immersion, code generation, theme identification, and theme confirmation) that guide a systematic thematic analysis were employed (39). First, we became immersed and acquainted with the data by reviewing the lyrics of each song and noting preliminary points of interest. Secondly, two of the authors engaged with the transcribed lyrics and lyrics were double-coded. Codes were then compared to ensure consistency. We coded any mention of coronavirus, its effects, or how people can avoid it or deal with it. Thirdly, we merged codes and categorized them into major themes. Lastly, we reviewed and made clear definitions for each theme generated from the data. The most representative lyrics for each identified theme were selected to summarize the findings. Non-English lyrics are first presented in italics in the original language, and then followed by an English translation. There was no disagreement between the authors during the analysis.

Results

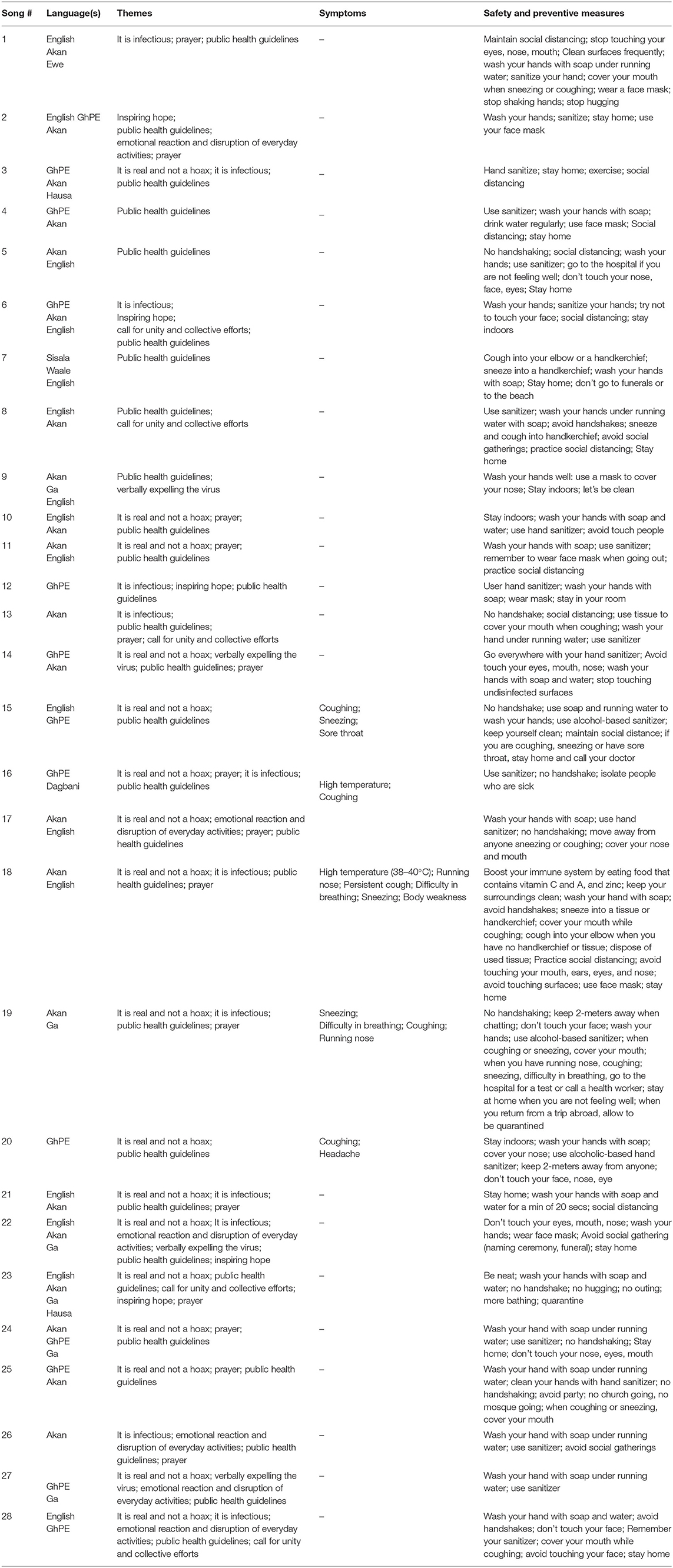

The final dataset included 28 songs that met study selection criteria. In addition to the themes described below, other characteristics of the lyrics are summarized in Table 1, including the languages in which the songs were sung, the signs and symptoms mentioned in the lyrics, and any mention of coronavirus preventive measures. The songs were in various genres of Ghanaian music including Hip-life, Gospel and Highlife. While only five songs were in one language, most were multilingual, with 14 songs in three languages and 10 songs in two languages (See Table 1). The languages that dominated the songs were Akan (n = 21), English (n = 16), and Ghanaian Pidgin English (GhPE) (n = 13).

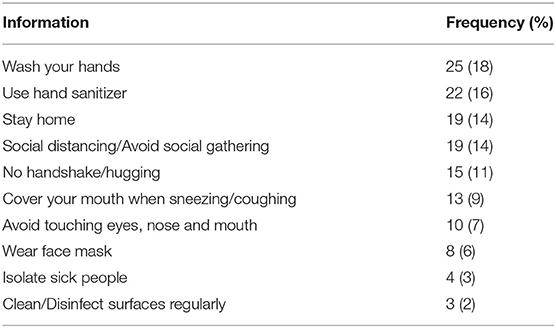

As shown in Table 1, all 28 songs mention some way to help prevent the infection. The step that people can take to prevent the transmission of the disease were also integrated in the lyrics. Examples of prevention included: wash your hands with soap under running water; rub your hands with alcohol-based sanitizer on a regular basis; avoid handshakes; use face masks; avoid social gatherings such as parties, funerals, and outdoor ceremonies; cover your mouth with a tissue when coughing or sneezing; and put yourself at a distance of about 2 m (6 feet) from other people during interactions.

Eight major themes emerged from the analysis of the song lyrics: (1) Public health guidelines, (2) COVID-19 is real and not a hoax, (3) COVID-19 is infectious, (4) Prayer as method to stop the virus, (5) Emotional responses and disruption of “everyday” activities, (6) Verbally expelling the virus, (7) Call for unity and collective efforts, and (8) Inspiring hope. Each of these themes is described below.

Public Health Guidelines

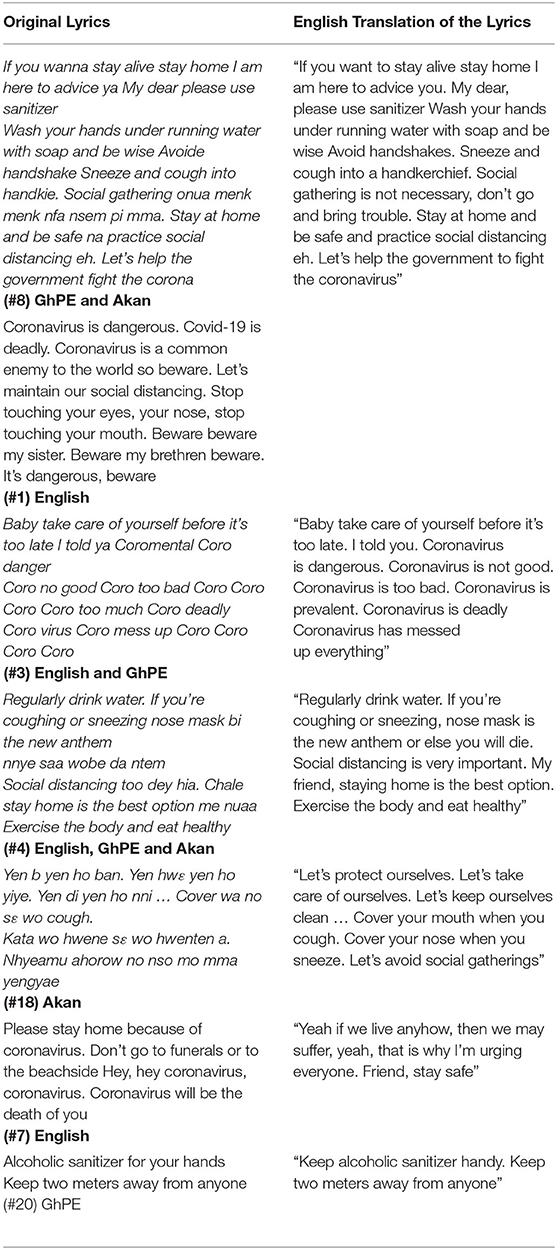

The most prevalent theme in all the songs was emphasis on public health guidelines including the need for personal responsibility to avoid getting infected and infecting others. The lyrics suggested that the only way to combat the disease is to adhere to public health guidelines. Lyrics indicated that people can generally take care of themselves during the pandemic by adopting healthy lifestyles and by being compliant with public health guidelines from the WHO, Ghana Health Service, and Ministry of Health. Examples of lyrics that support this theme are as follow.

Lyrics supporting the theme of public health guidelines

As seen in Table 2, all the preventive measures were found in the song lyrics. Handwashing was the most frequently mentioned measure (n = 25). The musicians also emphasized the need for individual responsibility to avoid contracting coronavirus and subsequently, ward off death. They added that in order to maintain health, one must eat healthy, maintain good personal hygiene, keep surroundings clean, remain hydrated, and exercise regularly.

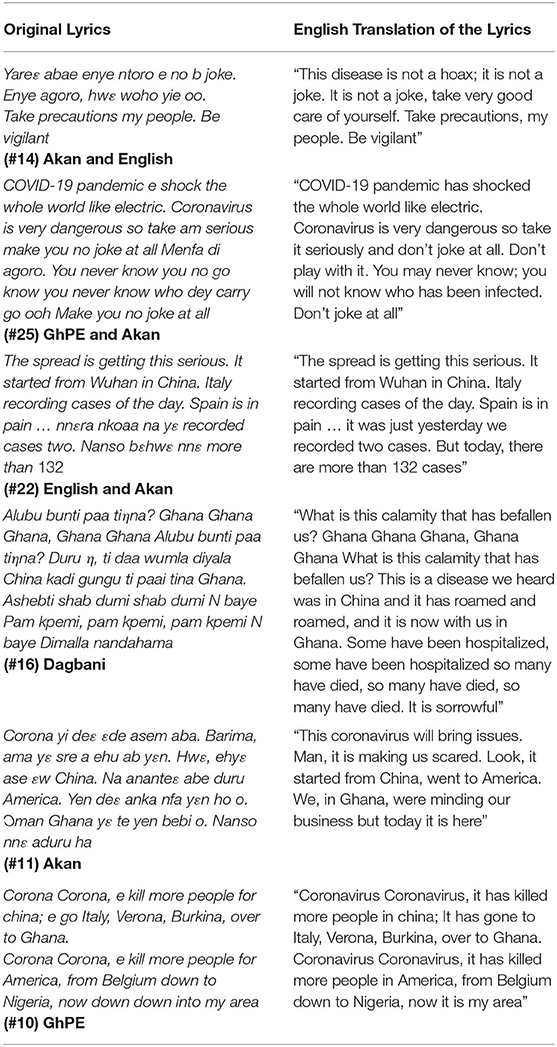

COVID-19 Is Real and Not a Hoax

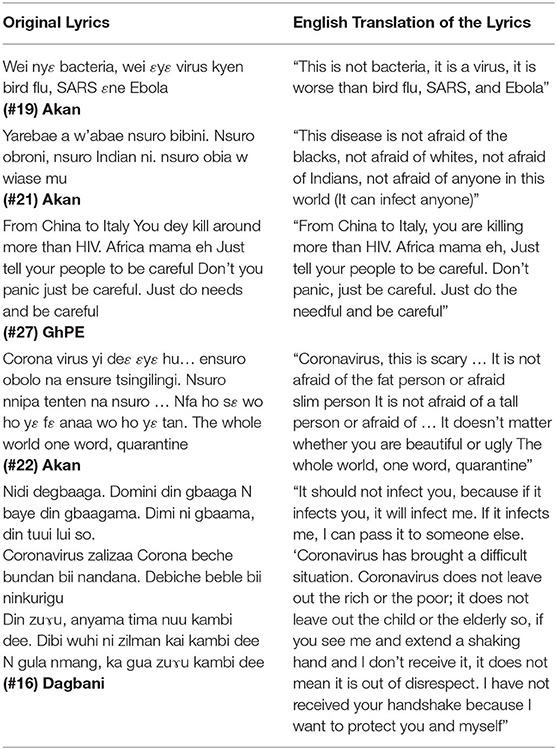

The songs sought to inform the public that coronavirus is real and not a hoax as believed by some people. Some lyrics indicated that the disease emerged from China and spread to almost all parts of the world including Europe, United States of America, and Africa. Musicians sang about many people dying, and many others being hospitalized in these countries as a result of contracting the disease. Others referred to the fact that Ghana first recorded only two cases but there has since been an exponential growth in the number of infections. Lyrics that support this theme are listed below.

Lyrics supporting the theme that coronavirus is real and not a hoax

COVID-19 Is Infectious

In addition to informing the public that COVID-19 is real and not a hoax, the songs warned that the virus is very infectious. Some lyrics made it clear that the novel coronavirus is even more infectious than other viral diseases including HIV, SARS, and Ebola, and older adults are the most vulnerable. The songs that projected this theme also had content about the disease affecting all categories of people, regardless of race, age, or social status. Below are examples of lyrics to support this theme.

Lyrics supporting the theme that coronavirus is infectious

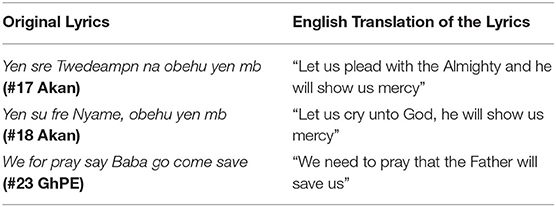

Prayer as Method to Stop the Virus

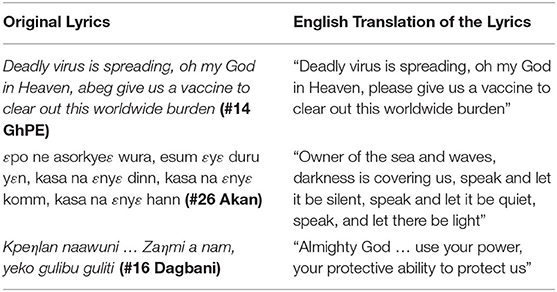

More than half of the songs expressed the idea that divine intervention is needed to curb the spread of the virus, and to heal and protect people. Some of the lyrics urged their audience to pray to God. For example:

Other lyrics were actual prayers asking God to help find a vaccine, restore calm to the world, or protect the people. The following are three such examples:

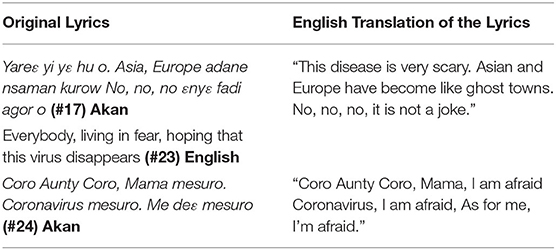

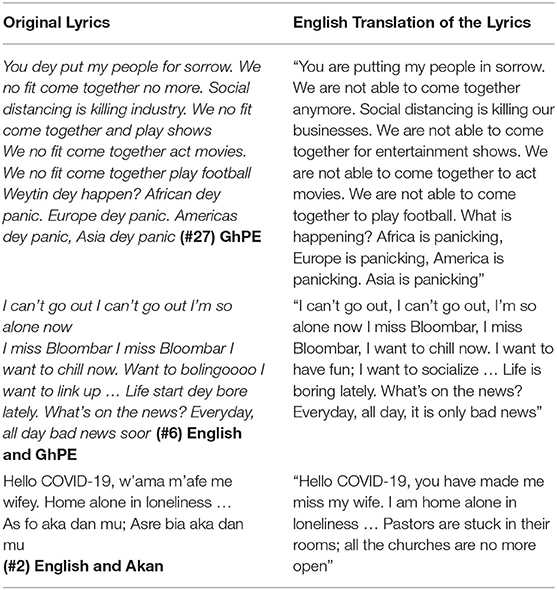

Emotional Reaction and Disruption of “Everyday” Activities

Apart from the health implications of coronavirus, other effects of the disease highlighted in the data include the fear it has induced in people and the emotional reactions to disruptions in social and economic activities. In the examples below, the world in general is identified as a fearful place, and some specific countries have been described as “ghost towns” due to the restrictions placed on movement.

Other lyrics mentioned that social gatherings are no longer allowed, thus no more public entertainment, sports, or religious activities. Consequently, people are feeling lonely because they cannot see their partners, loved ones or friends. Here are examples of lyrics that support this theme.

Lyrics supporting the theme of coronavirus emotional reactions to disrupted activities

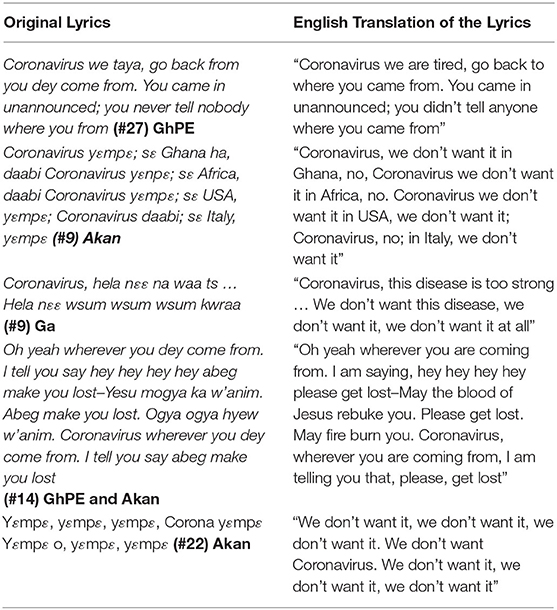

Verbally Expelling the Virus

On the basis of belief in the power of words by Ghanaians in general, some musicians verbally expelled the virus in their lyrics. Some clearly stated the world does not want this disease, while others asked the virus to go back to where it came from. Four examples of this theme are presented below.

Lyrics supporting the theme of verbally expelling the virus

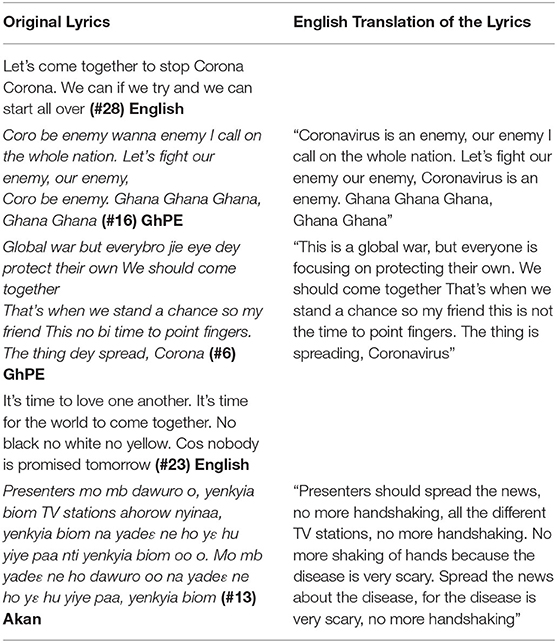

Call for Unity and Collective Efforts

In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, many lyrics in the data have called for a more collaborative mindset among individuals at the national level and among nations of the world at the global level. As everyone struggles to adapt to the current reality, people must recognize the need to support and collaborate across borders, to share what works and what does not work in fighting the disease. Some musicians described coronavirus as “a common enemy” and thus reinforced the need for unity and collective efforts at both national and global level to help defeat the virus. Some examples of this theme are included below.

Lyrics supporting the theme that coronavirus requires unity and collective efforts

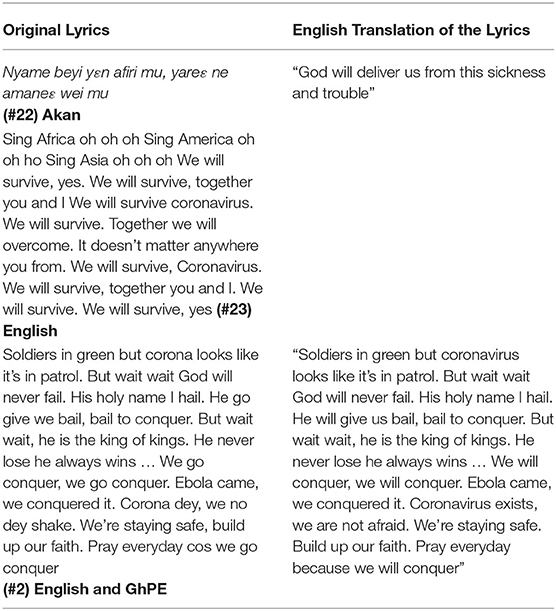

Inspiring hope

There were also lyrics that assured their audience that this pandemic will not last forever, and that soon the world will recover from its negative impact. Some musicians also expressed their belief that God will heal those infected and deliver the world from this pandemic.

Lyrics that illustrate the theme of inspiring hope:

Discussion

As evident in Table 1, the lyrics analyzed in this study involved various topics to create awareness about COVID-19. The major themes found from the analysis are “public health guidelines;” “COVID-19 is real and not a hoax;” “COVID-19 is infectious;” “prayer as method to stop the virus;” “emotional responses and disruption of “everyday” activities;” “verbally expelling the virus;” “call for unity and collective efforts;” and “inspiring hope.” The lyrics provided content on the prevalence of the disease, how indiscriminating and infectious it is, and how it has disrupted social activities on both personal and global level. Some signs and symptoms were identified in the lyrics, along with steps that people can take to prevent the transmission of the disease.

The song lyrics tend to identify COVID-19 as a global social crisis with significant public health impact rather than a local health issue. Thus, some of the musicians resorted to prayer and asked for divine intervention. They inform the public that COVID-19 has no cure, and infected people may be asymptomatic. They also conveyed emotional appeals that warned listeners that the disease is “an (common) enemy,” “highly infectious,” “dangerous,” “wicked,” “scary,” “serious,” and “deadly.” While some of these descriptions may induce fear, the message that many people all over the world have been infected irrespective of age, race, nationality, physical stature or social status, can be viewed as an essential step in de-stigmatizing the disease.

Acknowledging that loneliness is a common feeling during social isolation can help to address mental health issues, and the act of inspiring hope in some lyrics may also enhance the quality of life of persons who are already infected (54) or assure listeners who are not yet infected that overcoming the disease is possible. The theme of inspiring hope in this study highlights a belief among Ghanaians that reassurance is needed in every predicament, and thus important in health and social care (40). Together, these songs propose a collective effort to completely fight the virus, but at the same time encourage listeners to take responsibility for their own health and adopt the necessary precautions to avoid the impact of the disease. The theme of “call for unity and collective efforts” reflects the communal nature of the Ghanaian society. The collectivity that is projected in the lyrics of the songs implicate not only those who are affected (in)directly by the disease but also, everyone around them (41, 42).

In addition to promoting the public health guidelines for COVID-19, some of the musicians encouraged the use of prayer as well as verbally expelling the virus as methods of combating the disease. This is unsurprising because research has revealed that in Ghana, some people conceptualize the causes and cures of diseases through both biomedical and religious/spiritual means (43, 44, 56). As noted by Okyerefo and Fiavi (56), among Ghanaians, the religious/spiritual methods are viewed as complementary rather than challenging or competing with the biomedical models of healthcare. Seeking divine intervention through prayer during the COVID-19 pandemic can be attributed to the belief that “doctors can treat certain conditions, but only God heals” ((56), p. 308). The act of verbally expelling the virus is a display of belief in the power of words among Ghanaians. The general notion is that the power of spoken words just as the health of a person has a link with the metaphysical and supernatural world. As a result, words can be effective in dismissing diseases and healing practices (45). In a broad sense, the themes of prayer and verbally expelling the virus in this study provide us with the understanding that in Ghana, biomedical models exist and operate alongside other healthcare practices.

The multilingual nature of Ghana was also reflected in the song lyrics. Akan, English, and GhPE were the languages used most often in the composition of these songs. This finding is not surprising, rather it validates the assertion that these languages serve as “lingua francas” in Ghana. Akan is the most widely used local language in different social contexts (46) while English is the defacto official/national language and a cross-ethnic “lingua franca” in Ghana (35, 36). GhPE, however, functions as the only medium of communication between English speakers and non-English speakers who do not share a common local language or non-English people of different linguistic backgrounds (47, 51). Most of the musical artists displayed their bilingual/multilingual identity as Ghanaian and primarily used these languages of wider communication to ground their messages in socio-culturally relevant contexts.

Even though there are several local languages spoken in sub-Saharan Africa (48), most of the WHO and national educational guidelines on COVID-19 are in the country's official language (English or French). It is therefore important for public health specialists, politicians, media experts, and social leaders to employ strategies that use local languages rather than an official language only understood by smaller portions of a country's population. The use of songs composed in local languages could be an important means of sensitizing vulnerable citizens to the awareness and health implications of COVID-19. Music has much to offer to the communication efforts related to COVID-19 and is especially appropriate for educational needs due to its inherent participatory nature (see (49)). In addition to musicians, other artistic entertainers such as comedians and poets should also be involved in the broader efforts to engage and educate the public through messages conveyed in their spoken words. This should be done in consultation with public health workers to avoid misinformation.

Despite educational efforts targeted at creating awareness about COVID-19, the number of cases continues to soar in many parts of the world. This increase would suggest the need for new and novel approaches that can complement the existing mechanisms for raising COVID-19 awareness and prevention. Song lyrics may be one such approach. Although some lyrics may be controversial or irrelevant just for the purpose of creating a rhythm, music still represents an inexpensive yet innovative and powerful tool for discussing the novel coronavirus and best practices for preventing its spread. It is also noteworthy that not all song lyrics will make a positive contribution to promoting preventive behaviors; however, analysis of song lyrics can provide insight into local attitudes toward the virus. In addition, collaboration between health workers and musicians can offer a means to disseminate information in an accessible way.

Undoubtedly, additional research is needed in order to fully understand the impact of using music and lyrics to educate the public on COVID-19, however existing literature clearly demonstrates that music contributes a great deal to public education efforts related to HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases. The messages embedded in the lyrics of songs are designed to reach a large segment of the population faster and in a meaningful and more memorable fashion. People with a broad range of literacy and access to information can better retain these types of messages and thus achieve the goal of public health knowledge.

Limitations

The major limitations of this study include the limited focus on Ghana music and the potential for missing some songs created during this short time frame or not having access to other songs that were short-lived in the media. In addition, many of the songs used as data for this study could benefit from a more detailed lyrical analysis (9), which we hope will be undertaken in future research. Nevertheless, this paper focused on the unique and novel contribution of music to creating awareness about COVID-19 in Ghana and similar studies should also be conducted in other countries. Also, we did not assess the impact of the song lyrics on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors; therefore, a more comprehensive ethnographic study is needed to understand the impact of the songs on the society.

Conclusion

Raising public awareness on any social issue or health crisis often demands an increase in information dissemination through both formal and informal means. While it was not our intention to prioritize any one dissemination strategy, educating the public through diverse musical genres and other non-deliberative means could yield valuable global results. Music is one such information dissemination vehicle or promotion strategy utilized in health communication in many places over time, mainly because it has the potential to facilitate the process of behavioral change among specific sectors of the population. We showed that the lyrics in the songs used as data are informative and encourage people that they can and should take responsibility for their health and adhere to necessary safety protocols. Thus, the discourse on COVID-19 expressed through songs has relevance for the development of culturally appropriate health messaging. Results from this study support the idea that music has the ability to contribute to the fight against coronavirus and can be employed as an enjoyable supplement that reinforces or amplifies educational efforts in various communities around the world.

Results from this study can also be used to inform policymakers that investing in health communications using music could be worthwhile. Supporting musicians with sufficient resources to engage and educate citizens about the ongoing pandemic could be cost-effective. This study should be viewed as the beginning of a journey to document how music can be used to raise awareness about COVID-19. Generally, music is not immune to the problems of misinformation, and attention to song lyrics may provide broad insight into local discourse, including ideas that may contradict accepted public health messages. Therefore, a future study could focus on some recognition of the diversity of messages that may be communicated through songs in order to provide a more nuanced perspective. Further research is required to assess the impact of song lyrics as well as melodies and rhythms. However, results from this study should stimulate interest in how to use songs and tailor them to local communities to fight against COVID-19 and other future pandemic health crises.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

RT participated in the design of the study, analyzed all the research data, and drafted the manuscript. JN participated in the design of the study, analyzed the data, and reviewed the manuscript. JJ reviewed the manuscript and supervise the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by UCSF Population Health and Health Equity Scholar award under Grant number 7504575; the National Endowment for the Arts under Grant number P0541213; and the National Institute of Aging at the National Institutes of Health under Grant number P30AG15272.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Henrietta Freeman, Tricia Thompson, Wisdom Agbadi, Clement Agoni, and Yahaya Mohammed Sadat for their assistance in translating the non-English lyrics into English. We also thank Dr. Kathryn Lee for reviewing earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.607830/full#supplementary-material

References

1. WHO. Director-General's Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—March 2020. (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—2-march-2020 (accessed September 18, 2020).

2. Geldsetzer P. Use of rapid online surveys to assess people's perceptions during infectious disease outbreaks: a cross-sectional survey on COVID-19. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e18790. doi: 10.2196/18790

3. Seytre B. Erroneous communication messages on COVID-19 in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hygiene. (2020) 103:587–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0540

4. Wolf MS, Serper M, Opsasnick L, O'Conor RM, Curtis LM, Benavente JY, et al. Awareness, attitudes, and actions related to COVID-19 among adults with chronic conditions at the onset of the US outbreak: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Internal Med. (2020) 173:100–9. doi: 10.7326/M20-1239

5. Hu D, Lou X, Xu Z, Meng N, Xie Q, Zhang M, et al. More effective strategies are required to strengthen public awareness of COVID-19: evidence from Google Trends. J Glob Health. (2020) 10:1003. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.0101003

6. Prime News Ghana. We're unable to educate Ghanaians on coronavirus due to lack of funding from govt – NCCE. (2020). Available online at: www.ghanaweb.com; https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/We-re-unable-to-educate-Ghanaians-on-coronavirus-due-to-lack-of-funding-from-govt-NCCE-934519 (accessed May 20, 2020).

7. GhanaWeb. If you pay attention, you will see our works – NCCE boss tells Ghanaians. (2020). Available online at: www.ghanaweb.com; https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/If-you-pay-attention-you-will-see-our-works-NCCE-boss-tells-Ghanaians-932512 (accessed May 20, 2020).

8. Peek PM, Yankah K. African Folklore: An Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Routledge (2004). doi: 10.4324/9780203493144

9. Kambon OB, Adjei GK. Singing truth to power and the disempowered: the case of Lucky Mensah and his song, “Nkrato”. In:Olukotun A, Omotoso SA, editors. Political Communication in Africa. Berlin: Springer International Publishing (2017). p. 133–58. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-48631-4_9

10. Brown WJ, Fraser BP. Celebrity identification in entertainment-education. In: Singhal A, Cody MJ, Rogers EM, Sabido M, editors. Entertainment-Education and Social Change: History, Research, and Practice Entertainment-Education and Social Change. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum (2004). p. 119–38.

11. Brown S. How does music work? In: Brown S, Volgsten U, editors. Music and Manipulation: On the Social Uses and Social Control of Music. New York, NY: Berghahn Books (2006).

12. Bekalu MA, Eggermont S. Aligning HIV/AIDS communication with the oral tradition of Africans: a theory-based content analysis of songs' potential in prevention efforts. Health Commun. (2015) 30:441–50. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.867004

13. Kwong M. The impact of music on emotion: comparing rap and meditative yoga music. Inquiries J Student Pulse. (2016) 8:1. Available online at: http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1402 (accessed May 20, 2020).

14. Bastien S. Reflecting and shaping the discourse: the role of music in AIDS communication in Tanzania. Soc Sci Med. (2009) 68:1357–60. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.030

15. McConnell BB. Music and health communication in The Gambia: a social capital approach. Soc Sci Med. (2016) 169:132–40. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.028

16. Slater MD, Rouner D. Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Commun Theory. (2002) 12:173–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00265.x

17. Moyer-Gusé E. Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Commun Theory. (2008) 18:407–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x

18. Wang H, Singhal A. East Los high: transmedia edutainment to promote the sexual and reproductive health of young Latina/o Americans. Am J Public Health. (2016) 106:1002–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303072

19. Friedson SM. Dancing prophets: Musical experience in Tumbuka healing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1996).

20. Okigbo AC. South African music in the history of epidemics. J Folklore Res. (2017) 54:87–118. doi: 10.2979/jfolkrese.54.2.04

21. Bunn C, Kalinga C, Mtema O, Abdulla S, Dillip A, Lwanda J, et al. Arts-based approaches to promoting health in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. BMJ Global Health. (2020) 5:e001987. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001987

22. Isabirye J. Philly Lutaaya: popular music and the fight against HIV/AIDS in Uganda. J Postcolonial Writing. (2008) 44:29–35. doi: 10.1080/17449850701820632

23. Frishkopf M. Popular music as public health technology: music for global human development and “Giving Voice to Health” in Liberia. J Folklore Res. (2017) 54:41–86. doi: 10.2979/jfolkrese.54.2.03

24. McConnell BB, Darboe B. Music and the ecology of fear: Kanyeleng women Performers and Ebola prevention in the Gambia. Africa Today. (2017) 63:29–42. doi: 10.2979/africatoday.63.3.03

25. Sweat M. Report to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). A framework for classifying HIV-prevention interventions. Geneva: UNAIDS (2008).

26. Stone RM. “Ebola in Town:” creating musical connections in liberian communities during the 2014 Crisis in West Africa. Africa Today. (2017) 63:79–97. doi: 10.2979/africatoday.63.3.06

27. Van Buren KN. Partnering for social change: exploring relationships between musicians and organizations in Nairobi, Kenya. Ethnomusicol Forum. (2007) 16:303–26. doi: 10.1080/17411910701554070

28. National Research Council. Preventing and Mitigating AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: National Academy Press (1996).

30. Barz G, Cohen J. The Culture of AIDS in Africa: Hope and Healing Through Music and the Arts. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2011). doi: 10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199744473.001.0001

31. Salaudeen A. African Artists Are Creating Catchy Songs to Promote Awareness About Coronavirus. Cable News Network. (2020). Availbel online at: https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/17/africa/coronavirus-music-africa-intl/index.html (accessed May 20, 2020).

32. World Bank. Data: Ghana Population. (2019). Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL (accessed June 07, 2020).

33. Ansah GN. Re-examining the fluctuations in language in-education policies in post-independence Ghana. Multilingual Educ. (2014) 4:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13616-014-0012-3

34. Amfo NAA, Houphouet EE, Dordoye EK, Thompson R. “Insanity is from home:” the expression of mental health challenges in Akan. Int J Language Culture. (2018) 5:1–28. doi: 10.1075/ijolc.16016.amf

35. Anyidoho A, Dakubu MEK. Ghana: indigenous languages, English, and an emerging national identity. In: Simpson W, editor. Language and National Identity in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2008). p. 141–57.

36. Dako K, Quarcoo MA. Attitudes towards English in Ghana. Legon J Humanities. (2017) 28:20–30. doi: 10.4314/ljh.v28i1.3

37. Akrofi A. English literacy in Ghana: the reading experiences of ESOL first graders. TESOL J. (2003) 12:7–12. doi: 10.1002/j.1949-3533.2003.tb00124.x

38. Thompson R, Anderson JA. Interactive programmes on private radio stations in Ghana: an avenue for impoliteness. J African Media Stud. (2018) 10:55–72. doi: 10.1386/jams.10.1.55_1

39. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

40. Benson RB, Cobbold B, Boamah EO, Akuoko CP, Boateng D. Challenges, coping strategies, and social support among breast cancer patients in Ghana. Adv Public Health. (2020) 2020:4817932. doi: 10.1155/2020/4817932

41. Kane AA, Rink F. How newcomers influence group utilization of their knowledge: integrating versus differentiating strategies. Group Dyn. (2015) 19:91–105. doi: 10.1037/gdn0000024

42. van Swol LM, Carlson CL. Language use and influence among minority, majority, and homogeneous group members. Commun Res. (2017) 44:512–29. doi: 10.1177/0093650215570658

43. Peprah P, Gyasi RM, Adjei POW, Agyemang-Duah W, Abalo EM, Kotei JNA. Religion and Health: exploration of attitudes and health perceptions of faith healing users in urban Ghana. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6326-4

44. Kpobi LN, Swartz L, Omenyo CN. Traditional herbalists' methods of treating mental disorders in Ghana. Transcult Psychiatry. (2019) 56:250–66. doi: 10.1177/1363461518802981

45. Adu-Gyamfi S, Marfo C, Gbolo SC, Kodua P. Words in healing: some ethnographic observations from the Hohoe Area of Ghana. Int J Soc Sci Educ. (2018) 8:77–94.

46. Thompson R. Common Akan insults on GhanaWeb: a semantic analysis of kwasea, aboa, and gyimii. In: Peeters B, Mullan K, Sadow L, editors. Studies in ethnopragmatics, cultural semantics, and intercultural communication. Singapore: Springer Nature (2020). p. 103–22. doi: 10.1007/978-981-32-9975-7_6

47. Huber M. Ghanaian Pidgin English in its West African Context. A Sociohistorical and Structural Analysis. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. (1999). doi: 10.1075/veaw.g24

48. Downing LJ. Accent in African languages. In van der Hulst H, Goedemans R, van Zanten E, editors. A survey of word accentual patterns in the languages of the world. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter (2010). p. 381–427.

49. McConnell BB. Music, Health, and Power: Singing the Unsayable in the Gambia. New York, NY: Routledge (2019). doi: 10.4324/9780367312732

50. Barz G, Cohen J. Music and HIV/AIDS in Africa. In: Stone RM, editor. The Garland Handbook of African Music. New York, NY: Routledge (2008). p. 148–59. doi: 10.4324/9780203927878-13

51. Eberhard DM, Simons GF, Fennig CD. Ethnologue: Languages of the world, 20th Edn. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. (2019). Available online at: http://www.ethnologue.com (accessed June 22, 2020).

52. Ganeshasundaram R, Henley N. Reality television (Supernanny): a social marketing “place” strategy. J Consumer Market. (2009) 26:311–9. doi: 10.1108/07363760910976565

53. Govender E. Working in the greyzone: exploring education-entertainment in Africa. African Commun Res. (2013) 6:5–32.

54. Hasson-Ohayon I, Kravetz S, Meir T, Rozencwaig S. Insight into severe mental illness, hope, and quality of life of persons with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Psychiatry Res. (2009) 167:231–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.04.019

55. Mbaegbu CC. The effective power of music in Africa. Open J Philos. (2015) 5:176–83. doi: 10.4236/ojpp.2015.53021

56. Okyerefo MPK, Fiaveh DY. Prayer and health-seeking beliefs in Ghana: understanding the “religious space” of the urban forest. Health Sociol Rev. (2017) 26:308–20. doi: 10.1080/14461242.2016.1257360

Keywords: infectious disease, edutainment, preventive measure, song lyrics, multilingual population

Citation: Thompson RGA, Nutor JJ and Johnson JK (2021) Communicating Awareness About COVID-19 Through Songs: An Example From Ghana. Front. Public Health 8:607830. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.607830

Received: 18 September 2020; Accepted: 10 November 2020;

Published: 18 January 2021.

Edited by:

Rukhsana Ahmed, University at Albany, United StatesReviewed by:

James Olumide Olufowote, University of Oklahoma, United StatesCharles C. Okigbo, North Dakota State University, United States

Copyright © 2021 Thompson, Nutor and Johnson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rachel G. A. Thompson, Z29sZGF0aG9tcHNvbkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Rachel G. A. Thompson

Rachel G. A. Thompson Jerry John Nutor2

Jerry John Nutor2