- 1Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Community Health Sciences, Counseling, and Counseling Psychology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, United States

- 2Center for Population Health and Aging, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 3Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, School of Public Health, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

The rapid growth of the global aging population has raised attention to the health and healthcare needs of older adults. The purpose of this mini-review is to: (1) elucidate the complex factors affecting the relationship between chronological age, socio-economic status (SES), access to care, and healthy aging using a SES-focused framework; (2) present examples of interventions from across the globe; and (3) offer recommendations for research-guided action to remediate the trend of older age being associated with lower SES, lack of access to care, and poorer health outcomes. Evidence supports a relationship between SES and healthcare access as well as healthcare access and health outcomes for older adults. Because financial resources are proportional to health status, efforts are needed to support older adults and the burdened healthcare system with financial resources. This can be most effective with grassroots approaches and interventions to improve SES among older adults and through data-driven policy and systems change.

Introduction

Healthy aging, also known as successful aging (1), is defined by the World Health Organization as “the process of developing and maintaining functional ability that enables well-being in older age” (2). It encompasses the physical and mental capacities of an older adult at any given time (3) as well as the resources and supports they access and utilize. Central to the concept of healthy aging is disease and disability prevention and management; maintenance of good physical and cognitive functionality; and engagement in active lifestyles and healthful behaviors (4). Healthy aging is a primary goal of modern medicine, especially as it relates to geriatric care. Despite efforts to make healthy aging ‘the new normal (5, 6), subsets of the growing older adult population are faced with financial hardships resulting in inequities of resource distribution and disparities in health outcomes.

As our global society rapidly ages, we potentially face a future of impoverished older adults lacking access to care in already overburdened healthcare systems. In this context, healthy aging is fraught with difficulties. This mini-review: (1) discusses the relationship between chronological age, socio-economic status (SES), access to care, and healthy aging; (2) presents examples of interventions from across the globe; and (3) offers recommendations for research-guided action to remediate the trend of older age being associated with lower SES, lack of access to care, and poorer health outcomes.

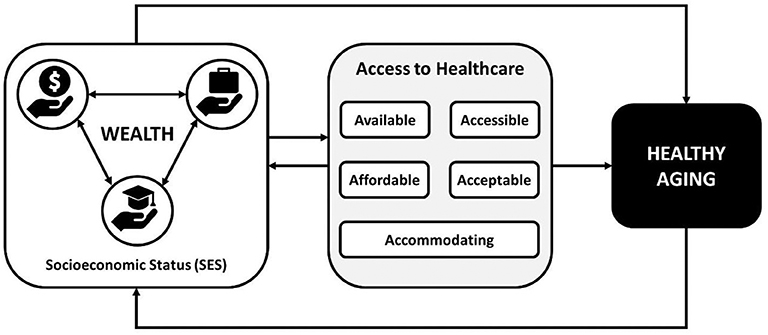

In the framework of this mini-review (see Figure 1), healthy aging is primarily a function of SES, with SES consisting of lifelong evolving and recursive statuses around the reflexive position of a person's financial situation, educational attainment, and employment status. A person's ability to access care is mediated by SES. Access to healthcare implies the availability of relevant and effective services and providers, physical accessibility, and affordability, how accommodating services and service providers are, and the acceptability of the services and service providers to the patient (7). Whether a population has access to healthcare is typically measured through availability (i.e., a count of providers in a defined area), utilization (i.e., rates of a target population using a certain type of healthcare service or resource), and health outcomes of the target population (8).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for socioeconomic status and healthcare access driving healthy aging.

In addition, access to care can affect a person's SES through a downward trajectory, where (for example) poverty reduces access to healthcare, which leads to increased morbidity, which leads to increased poverty and further reductions in access to care. Context, such as rurality, neighborhood, or country has a similar relationship to healthy aging through SES. A person's context also affects access to care, as noted in areas with limited access to care due to lack of healthcare providers (like rural or remote communities). Given the relative difficulty of changing context and the extended timeframe needed to do so, it is essential to target interventions at the more immediately accessible constructs of access to care and SES through wealth and reducing financial disparities and costs of care. In a variety of contexts, lower SES is associated with reduced access to care, poorer health outcomes, and increased mortality and morbidity as individuals age (9–18). Thus, this mini-review specifically targets the relationship between wealth, access to healthcare, and healthy aging.

Wealth, Access to Care, and Healthy Aging

Our framework emphasizes the socioeconomic gradient (or “wealth-health” gradient), which highlights the positive relationship between wealth and health. That is, as wealth increases so does health, with the converse also holding true. Lower economic status leads to poorer health, which in turn leads to a dangerous cycle of further impoverishment (19). Simply stated, there is a relationship between SES and health, with low SES associated with poorer health (20–24).

Wealth and Healthy Aging

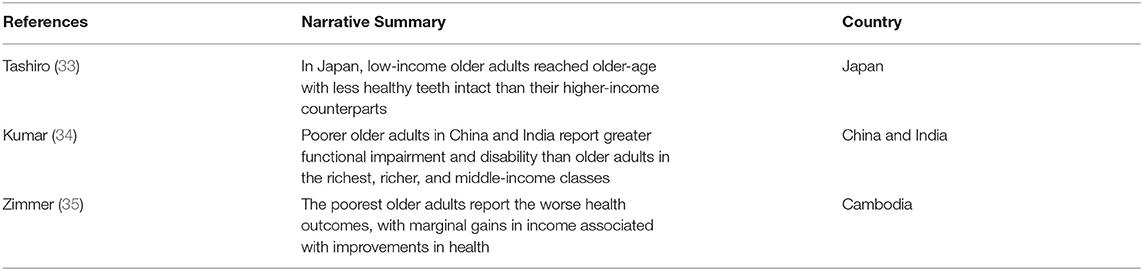

The “wealth-health” gradient becomes more pronounced as people age. Socioeconomic status is intimately tied to healthy aging, with greater wealth producing a greater likelihood of health among older adults (25). This association may be due to the combined effects of increased stress, trauma, allopathic load, and limited access to appropriate and timely healthcare (17, 26–28). Low SES also contributes to heavier disease burden. For example, poorer older adults experience more dental disease (29, 30) and disability (31, 32). This effect is global. In Japan, low-income older adults reached older-age with less healthy teeth intact than their higher-income counterparts (33). Poorer older adults in China and India report greater functional impairment and disability than older adults in the richest, richer, and middle-income classes (34). In Cambodia, the poorest older adults report worse health outcomes, with marginal gains in income associated with improvements in health (35). Financial instability can, in some cases, explain the poorer mortality and morbidity often found among racial and ethnic minorities compared to majority populations (36). Table 1 provides an overview of selected evidence documenting the relationship between wealth and healthy aging from different countries.

Wealth and Access to Care

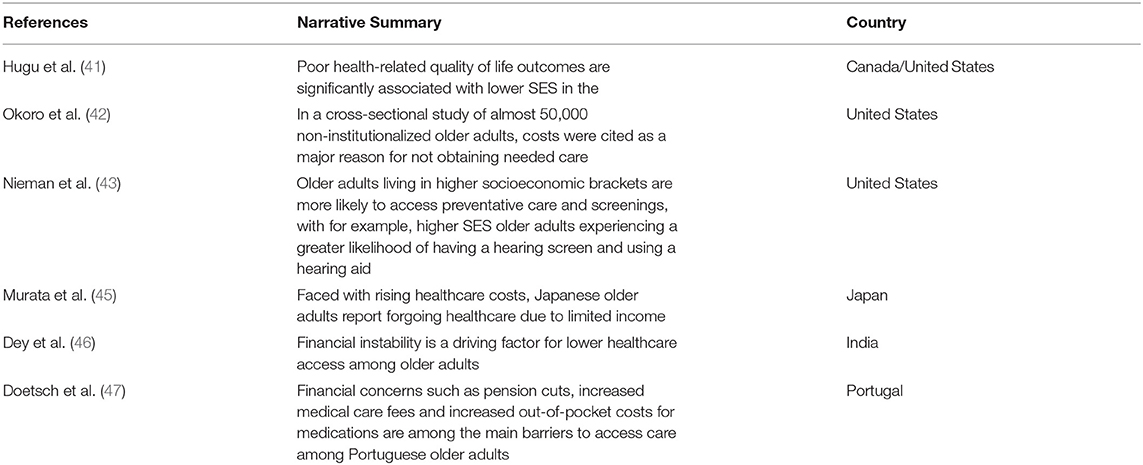

Socioeconomic status is tied to healthcare access among older adults, perceived or otherwise (37, 38). Variation in healthy aging based on income levels may be attributed to differential healthcare access: wealthier older adults have better access to care, and access to care (from preventative services to long-term care) may be associated with better health outcomes (21, 39, 40). Poor health-related quality of life outcomes are significantly associated with lower SES in the United States, which is possibly driven by limited healthcare access among poorer older adults (41). In a cross-sectional study of almost 50,000 non-institutionalized older adults, costs were cited as a major reason for not obtaining needed care (42). Older adults living in higher socioeconomic brackets are more likely to access preventative care and screenings, with for example, higher SES older adults experiencing a greater likelihood of having a hearing screen and using a hearing aid (43). Lower SES is associated with longer wait times in countries with centralized healthcare systems (44). Faced with rising healthcare costs, Japanese older adults report forgoing healthcare due to limited income (45). In India, financial instability is a driving factor for lower healthcare access among older adults (46). Portuguese older adults cite financial concerns (e.g., pension cuts, increased medical care fees, and increased out-of-pocket costs for medications) among the main barriers to access to care (47). In some cases, older adults with low SES are simply not offered the same care as older adults with higher incomes, resulting in income-related treatment disparities (48–50). Table 2 provides an overview of selected evidence documenting the relationship between wealth and access to care from different countries.

Access to Care and Healthy Aging

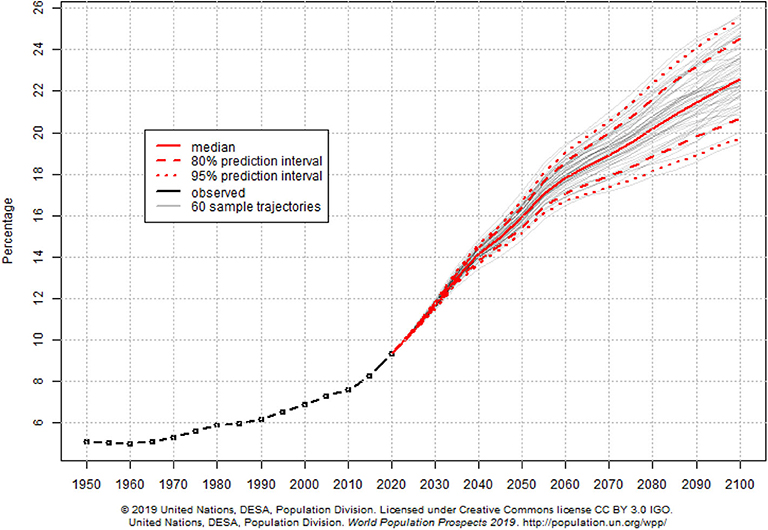

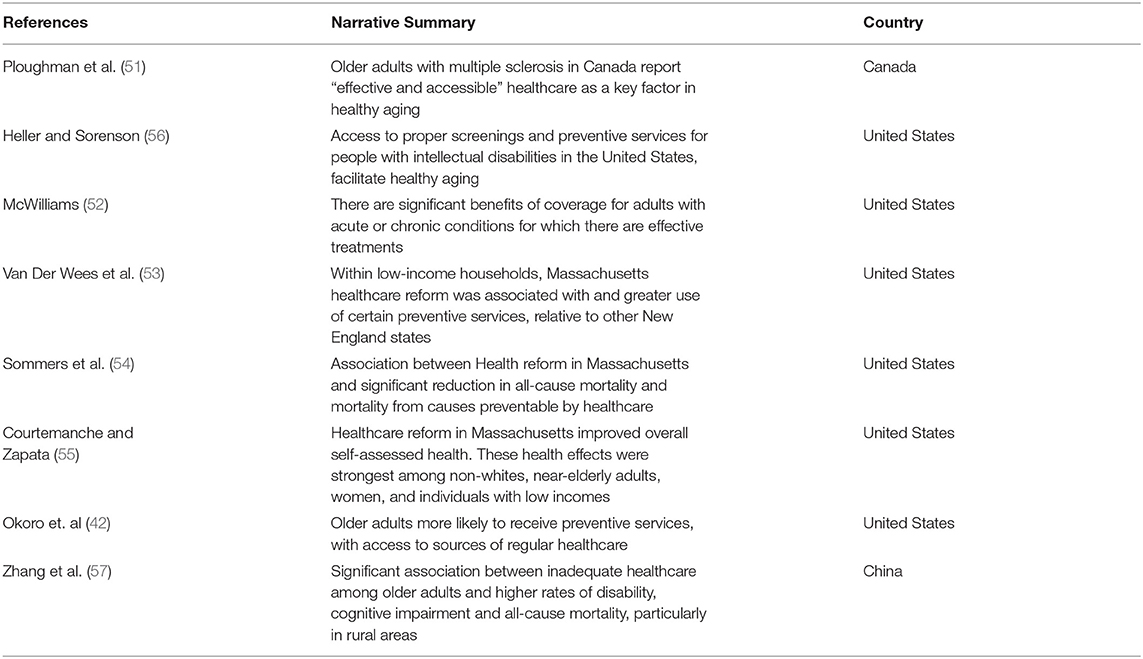

Access to healthcare is related to healthy aging. Older adults with multiple sclerosis in Canada report “effective and accessible” healthcare as a key factor in healthy aging (51). In the United States, providing health insurance coverage—a necessary conduit for access to healthcare—improves health outcomes and mortality in general and among older adults (52–55). Older adults in the United States are significantly more likely to receive clinical preventive services with access to regular sources of healthcare. (42) Similarly, for people with intellectual disabilities in the United States, access to proper screenings and preventive services facilitates healthy aging (56). In China, self-reported inadequate access to healthcare among older adults was significantly associated with higher rates of disability, cognitive impairment, and all-cause mortality, particularly in rural areas (57). Considering the importance of access to healthcare for healthy aging, our global community struggles to provide appropriate and timely access to healthcare for people aged 65 or older (58). Our difficulty to provide relevant and effective services for older adults is partially attributed to rapidly shifting demographics. As the number of projected older adults grows from about 524 million in 2010 to nearly 1.5 billion in 2050, the projected number of younger people (ages 0–25 years) is expected to decrease (59). This phenomenon shifts the dependency ratio and results in an increasing percentage of older adults in the global population (see Figure 2).

Still more of our difficulty providing access to care may be explained by shifts in disease burden. As our global population steadily ages, the chronic diseases highly associated with aging (e.g., heart disease, stroke, and COPD) now pose the greatest threat to global health (59). In 2000, dementia was the 14th leading cause of death worldwide, but by 2016, dementia-related deaths rose to the 5th leading cause of death (60). Across the globe, healthcare systems may be ill-prepared to shift resources to meet the demand for geriatric care and chronic disease treatment and management. Table 3 provides an overview of selected evidence documenting the relationship between access to care and healthy aging from different countries.

Improving Access to Healthcare Among Older Adults

A lack of financial resources leads to poor health, which can, in turn, lead to a dangerous cycle of further impoverishment (19). Future disparities in mortality based on income inequalities in older adults could diminish with the implementation of interventions designed to reduce barriers to care among younger populations (61). Internationally, interventions that either directly improve healthcare access (e.g., by expanding health insurance) or focus on alleviating financial disparities typically lead to improved health among older adults (62–64).

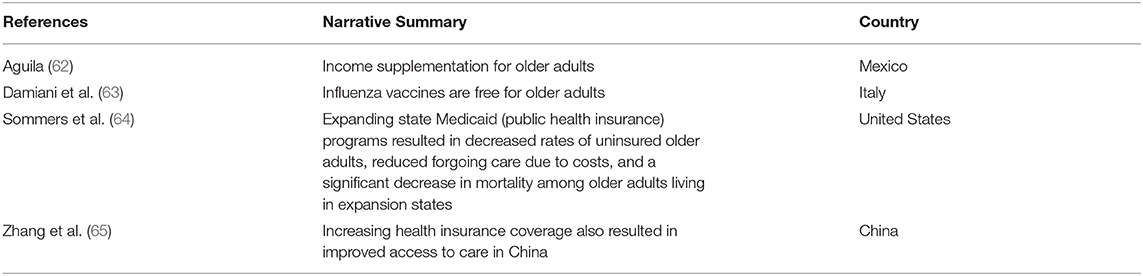

Mexico experimented with income supplementation for older adults. Elderly residents of two states in the Yucatan who received income supplementation (i.e., a 44% increase in household income) spent their extra income on doctor visits and medications, and realized improved health outcomes (62). In Italy, socioeconomic disparities in influenza vaccinations exist among adults, but not among older adults. Influenza vaccines are free for older adults, thus potentially remediating any socioeconomic effect in vaccine uptake (63). In the United States, expanding state Medicaid (public health insurance) programs resulted in decreased rates of uninsured older adults, reduced forgoing care due to costs, and a significant decrease in mortality among older adults living in expansion states (64) Increasing health insurance coverage also resulted in improved access to care in China (65). Table 4 provides an overview of selected evidence documenting strategies to improve access to healthcare among older adults from different countries.

Discussion

The rapid growth of the global aging population alongside projected decreases in younger demographics (59) will pose new and intensified access barriers and burdens on healthcare systems worldwide. This scenario highlights the importance of building and supporting healthcare infrastructure and processes to effectively identify the healthcare needs of older adults and efficiently serve them with quality services. With a growing consumer base and unchanged healthcare systems, our ability to adequately care for an aging society will become labored and severely compromised, which will diminish health outcomes and opportunities for healthy aging.

As documented in this mini-review, substantial evidence exists to support the strong interplay between socioeconomic status (SES), healthcare access, and healthy aging. Several studies document the relationship between SES, healthcare utilization, and health outcomes among older adults across the globe. Universally, the majority of studies show that lower SES is associated with more access barriers (10–16), which is subsequently associated with worse health outcomes and premature death. Compounding disparities exist which exacerbate these relationships among people of color and other minority or traditionally disenfranchised groups (36, 65). Evidence suggests that removing the financial barriers to healthcare access such as providing universal healthcare coverage in European countries or Medicare in the United States (64) can improve health outcomes.

Traditionally, the Anderson Behavioral model contextualizes healthcare access as a function of predisposing, enabling, and need-related factors (66). While this is a strong approach to understand the factors associated with healthcare access, it is an individual-level model and requires additional context to apply to larger communities and populations. The issue of healthcare access among older adults has upstream and downstream elements and considerations. Because aging begins at birth, the outcomes that manifest in older adulthood have origins in earlier years that are more formative. The SES of an individual throughout their life-course can enhance or suppress disease and other healthcare needs. And, patterns of healthcare utilization in earlier years can characterize older adult healthcare access and utilization patterns.

Recommendations for Future Research

Surveillance efforts and research are needed to better understand the trends in aging and associated disparities in SES and healthcare access worldwide, especially in light of the seemingly paradoxical findings in the recent literature. However, measurement issues complicate our ability to fully understand the relationship between SES and healthcare access among older adults. In the field of health services research, SES is not uniformly measured, which has vast implications for advancing healthy aging. Measurement of SES in health services research is difficult, due to the variety of definitions and constructs measured under this concept (67–69). Choice of definition and measurement affects the outcomes of disparity research. Considering the complexity of appropriately measuring SES (a combination of education, employment, and income), multidimensional SES measures (i.e., household income vs. community wealth) may create a more accurate picture of the drivers of health disparities (70, 71). Unfortunately, many studies simply measure and utilize one aspect of SES (e.g., household income), which does not fully encapsulate SES and only serves as a proxy to the theorized construct. Or, studies include multiple measures of SES, but include them in statistical models as separate variables, not accounting for multicollinearity and interdependence. This measurement issue is further complicated when measuring SES in later life because of the complexities of SES based on educational norms of decades past, years post-retirement, and subsidized healthcare in advanced age. As such, it is suggested that SES is better measured by wealth instead of income as people age and retire (72). This ultimately has practical implications that influence the associated findings, interpretations, and recommendations for action to improve healthcare access within the field. For example, while increasing health insurance coverage resulted in improved access to care in China, income-related disparities still existed. Higher-income older adults accessed more outpatient services (65). This suggests a need to further explore the relationship between income, health insurance, and healthcare access among older adults. Developing standardized and evidence-based guidelines for trend surveillance among these factors would allow more accurate and consistent comparisons between countries and other contexts. Likewise, creating expert consensus on measurement issues related to SES is necessary to improve our understanding of the relationship between SES, access to care, and healthy aging, and facilitate moving beyond mortality as the major outcome of that relationship.

Furthermore, we find diminishing returns as marginalized populations attain higher socioeconomic statuses, with people of color experiencing less health benefits than whites from socioeconomic attainment (73). In a study of preventative screenings among women living in the United States, Monnat found that low SES women were less likely to receive a mammogram or pap smear (74). As SES increased, white women were more likely than women of color to receive these services. In what Monnat referred to as “paradoxical returns,” the likelihood that Asian women received a mammogram or Pap smear decreased as SES increased. Even when healthcare services are introduced in a community by reducing the proximity to clinics or reducing socioeconomic barriers, there is no guarantee that target populations, including older adults, will access and utilize these services. Moving forward, we must consider the upstream and downstream effects of SES on healthcare access. While SES hinders the ability of older adults to access healthcare services, improving their financial situation in any capacity alleviates burdens and stressors that can improve their healthcare use patterns and health outcomes. For example, linking older adults to services that save them money (e.g., congregate meal programs, medication assistance programs, transportation services) increases the chances they will use the unused funds for needed healthcare.

Opportunities exist to rethink traditional healthcare to provide complementary services that are free or low-cost. While healthcare is often considered to take place within clinical settings, other resources, services, and programs can assist older adults in the community. For example, in the United States, the federal government has supported a number of evidence-based programs for low-income and vulnerable older adults to help them improve health outcomes (e.g., fall prevention, chronic disease self-management) (75–77). These programs transcend traditional clinical settings and complement healthcare while increasing access to health services.

There is a projected increase in the number of older adults, and an attendant decrease in the number of younger adults in the years to come (59). This projection brings to light the importance of putting structures in place that identify the needs and challenges of providing care to older adults, as well as an estimation of the resources needed to ensure older adults have healthcare access to improve their health outcomes. Properly assessing SES among older adults is essential for providing older adults with basic and necessary healthcare access and services. Although programs like Medicaid in the United States have helped in this regard, more can be done (64). At current, the healthcare system is ill-equipped to handle the volume of older adults requiring healthcare, which creates an inverse supply-demand ratio. In short, even if access to healthcare is improved for those with low SES, the healthcare system may be unable to adequately serve the influx in older adult patients. However, because evidence supports that financial resources are directly proportional to good health (19), efforts are needed to support individuals and the healthcare system with financial resources. This can be most effective with grassroots approaches and interventions to improve SES among older adults and through data-driven policy and systems change.

Caveats

While access to care is necessary for health aging, focusing on access alone is not sufficient to improve the health of populations (78). Access to health care can improve health outcomes, but most likely only to a certain degree, necessitating a complementary focus on social determinants (79). In some instances, more healthcare doesn't equal “more” health. In Taiwan, increased access to health care through health insurance and the resulting increase in health services utilization did not affect mortality or self-perceived health (80). Similarly, more expensive healthcare isn't linked to better outcomes, at least among Medicare recipients in the United States (81). In Brazil, where older adults have access to healthcare through a public health care system and private insurance, patient perceptions affect treatment initiation and glycemic control of Type II diabetes (82). Improving access to healthcare by reducing financial disparities and improving wealth among older adults is a vital first step but should not be seen as the final step in ensuring global healthy aging.

Author Contributions

DM, OO, and MS conceptualized, wrote, and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. McLaughlin SJ. Healthy aging in the context of educational disadvantage: the role of “Ordinary magic”. J Aging Health. (2017) 29:1214–34. doi: 10.1177/0898264316659994

2. World Health Organization. Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health (2016-2020)[Internet]. Geneva: WHO (2016).

3. Beard JR, Officer A, De Carvalho IA, Sadana R, Pot AM, Michel JP, et al. The world report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. The Lancet. (2016) 387:2145–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00516-4

4. McLaughlin SJ, Jette AM, Connell CM. An examination of healthy aging across a conceptual continuum: prevalence estimates, demographic patterns, and validity. J Gerontol Ser. (2012) 67:783–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr234

5. Ory MG, Smith ML. What if healthy aging is the 'new normal'? Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:1389. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111389

6. Jin K. New perspectives on healthy aging 2017. Europe PMC. Prog Neurobiol. (2017) 167:1. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2017.08.006

7. McLaughlin CG, Wyszewianski L. Access to care: remembering old lessons. Health Services Res. (2002) 37:1441–3. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12171

8. Gulliford M, Figueroa-Munoz J, Morgan M, Hughes D, Gibson B, Beech R, et al. What does 'access to health care' mean? J Health Serv Res Policy. (2002) 7:186–8. doi: 10.1258/135581902760082517

9. Bassuk SS, Berkman LF, Amick III BC. Socioeconomic status and mortality among the elderly: findings from four uS communities. Am J Epidemiol. (2002) 155:520–33. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.6.520

10. Luo J, Zhang X, Jin C, Wang D. Inequality of access to health care among the urban elderly in northwestern china. Health Policy. (2009) 93:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.06.003

11. Hu P, Wagle N, Goldman N, Weinstein M, Seeman TE. The associations between socioeconomic status, allostatic load and measures of health in older taiwanese persons: taiwan social environment and biomarkers of aging study. J Biosoc Sci. (2007) 39:545–56. doi: 10.1017/S0021932006001556

12. Menec VH, Shooshtari S, Nowicki S, Fournier S. Does the relationship between neighborhood socioeconomic status and health outcomes persist into very old age? A population-based study. J Aging Health. (2010) 22:27–47. doi: 10.1177/0898264309349029

13. Sun J, Deng S, Xiong X, Tang S. Equity in access to healthcare among the urban elderly in china: does health insurance matter? Int J Health Plann Manage. (2014) 29:e127–e44. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2227

14. Wee LE, Yeo WX, Yang GR, Hannan N, Lim K, Chua C, et al. Individual and area level socioeconomic status and its association with cognitive function and cognitive impairment (low mMSE) among community-dwelling elderly in singapore. Dement Geriat Cogn Disord. (2012) 2:529–42. doi: 10.1159/000345036

15. Shea S, Lima J, Diez-Roux A, Jorgensen NW, McClelland RL. Socioeconomic status and poor health outcome at 10 years of follow-up in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0165651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165651

16. Stringhini S, Carmeli C, Jokela M, Avendaño M, McCrory C, d'Errico A, et al. Socioeconomic status, non-communicable disease risk factors, and walking speed in older adults: multi-cohort population based study. BMJ. (2018) 360:k1046. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1046

17. Wenger NS, Solomon DH, Roth CP, MacLean CH, Saliba D, Kamberg CJ, et al. The quality of medical care provided to vulnerable community-dwelling older patients. Ann Intern Med. (2003) 139:740–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00008

18. Rehkopf DH, Haughton LT, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Subramanian SV, Krieger N. Monitoring socioeconomic disparities in death: comparing individual-level education and area-based socioeconomic measures. Am J Public Health. (2006) 96:2135–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075408

20. Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. Income inequality and health: a causal review. Soc Sc Med. (2015) 128:316–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.031

21. Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Peregoy JA. Summary Health Statistics for US Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office (2012).

22. Hajat A, Kaufman JS, Rose KM, Siddiqi A, Thomas JC. Long-term effects of wealth on mortality and self-rated health status. Am J Epidemiol. (2010) 173:192–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq348

23. Ramsay SE, Whincup PH, Morris RW, Lennon LT, Wannamethee SG. Extent of social inequalities in disability in the elderly: results from a population-based study of british men. Ann Epidemiol. (2008) 18:896–903. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.09.006

24. Feinstein JS. The relationship between socioeconomic status and health: a review of the literature. Milbank Quart. (1993) 71:279–22. doi: 10.2307/3350401

25. Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Seeman TE. Poverty and biological risk: the earlier “aging” of the poor. J Gerontol. (2009) 64:286–92. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln010

26. Perissinotto CM, Cenzer IS, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in older persons: a predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. (2012) 172:1078–84. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993

27. Baum A, Garofalo JP, Yali AM. Socioeconomic status and chronic stress: does stress account for SES effects on health? Ann N Y Acad Sci. (1999) 896:131–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08111.x

28. Kondo N, Saito M, Hikichi H, Aida J, Ojima T, Kondo K, et al. Relative deprivation in income and mortality by leading causes among older japanese men and women: aGES cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2015) 69:680–5. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-205103

29. Dolan TA, Atchison K, Huynh TN. Access to dental care among older adults in the United States. J Dent Educ. (2005) 69:961–74. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2005.69.9.tb03993.x

30. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health (2000).

31. Fleck C. Older minorities are becoming america's poorest residents. AARP Bulletin Today. (2008).

32. Schoeni RF, Martin LG, Andreski PM, Freedman VA. Persistent and growing socioeconomic disparities in disability among the elderly: 1982-2002. Am J Public Health. (2005) 95:2065–70. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048744

33. Tashiro A, Aida J, Shobugawa Y, Fujiyama Y, Yamamoto T, Saito R, et al. Association between income inequality and dental status in japanese older adults: analysis of data from jAGES2013. Japanese J Public Health. (2017) 64:190–6. doi: 10.11236/jph.64.4_190

34. Kumar K, Shukla A, Singh A, Ram F, Kowal P. Association between wealth and health among older adults in rural china and india. J Econ Ageing. (2016) 7:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jeoa.2016.02.002

35. Zimmer Z. Poverty, wealth inequality and health among older adults in rural cambodia. Soc Sci Med. (2008) 66:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.032

36. Du XL, Fang S, Vernon SW, El-Serag H, Shih YT, Davila J, et al. Racial disparities and socioeconomic status in association with survival in a large population-based cohort of elderly patients with colon cancer. Cancer. (2007) 110:660–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22826

37. Fitzpatrick AL, Powe NR, Cooper LS, Ives DG, Robbins JA. Barriers to health care access among the elderly and who perceives them. Am J Public Health. (2004) 94:1788–94. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1788

38. Yamada T, Chen C, Murata C, Hirai H, Ojima T, Kondo K, Harris JR III. Access disparity and health inequality of the elderly: unmet needs and delayed healthcare. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2015) 12:1745–72. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120201745

39. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2012: With Special Feature on Emergency Care. Hyattsville, MD (2013).

40. Klabunde CN, Joseph DA, King JB, White A, Plescia M. Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening test use-United States, 2012. Morb Mort Weekly Rep. (2013) 62:881.

41. Huguet N, Kaplan MS, Feeny D. Socioeconomic status and health-related quality of life among elderly people: results from the joint canada/United States survey of health. Soc Sci Med. (2008) 66:803–10. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.011

42. Okoro CA, Strine TW, Young SL, Balluz LS, Mokdad AH. Access to health care among older adults and receipt of preventive services. Results from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system 2002. Prev Med. (2005) 40:337–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.009

43. Nieman CL, Marrone N, Szanton SL, Thorpe RJ Jr, Lin FR. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in hearing health care among older americans. J Aging Health. (2016) 28:68–94. doi: 10.1177/0898264315585505

44. Siciliani L, Verzulli R. Waiting times and socioeconomic status among elderly europeans: evidence from SHARE. Health Econ. (2009) 18:1295–306. doi: 10.1002/hec.1429

45. Murata C, Yamada T, Chen C, Ojima T, Hirai H, Kondo K. Barriers to health care among the elderly in japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2010) 7:1330–41. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7041330

46. Dey S, Nambiar D, Lakshmi JK, Sheikh K, Reddy KS. Health of the elderly in india: challenges of access and affordability. In: Aging in Asia: Findings From New and Emerging Data Initiatives. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (2012).

47. Doetsch J, Pilot E, Santana P, Krafft T. Potential barriers in healthcare access of the elderly population influenced by the economic crisis and the troika agreement: a qualitative case study in lisbon, portugal. Int J Equity Health. (2017) 16:184. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0679-7

48. Mamdani MM, Tu K, Austin PC, Alter DA. Influence of socioeconomic status on drug selection for the elderly in canada. Ann Pharmacother. (2002) 36:804–8. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A044

49. Lemmens V, Van Halteren AH, Janssen-Heijnen M, Vreugdenhil G, Repelaer van Driel O J, et al. Adjuvant treatment for elderly patients with stage iII colon cancer in the southern netherlands is affected by socioeconomic status, gender, and comorbidity. Ann Oncol. (2005) 16:767–72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi159

50. Odubanjo E, Bennett K, Feely J. Influence of socioeconomic status on the quality of prescribing in the elderly-a population based study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2004) 58:496–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02179.x

51. Ploughman M, Austin MW, Murdoch M, Kearney A, Fisk JD, Godwin M, et al. Factors influencing healthy aging with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. (2012) 34:26–33. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.585212

52. McWilliams J. Health consequences of uninsurance among adults in the United States: recent evidence and michael implications. Milbank Q. (2009) 87:443–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00564.x

53. Van der Wees, Philip J, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Improvements in health status after massachusetts health care reform. Milbank Q. (2013) 91:663–89. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12029

54. Sommers BD, Long SK, Baicker K. Changes in mortality after massachusetts health care reform: a quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med. (2014) 160:585–93. doi: 10.7326/M13-2275

55. Courtemanche CJ, Zapata D. Does universal coverage improve health? The massachusetts experience. J Policy Anal Manag. (2014) 33:36–69. doi: 10.1002/pam.21737

56. Heller T, Sorensen A. Promoting healthy aging in adults with developmental disabilities. Dev Disab Res Rev. (2013) 18:22–30. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.1125

57. Zhang X, Dupre ME, Qiu L, Zhou W, Zhao Y, Gu D. Urban-rural differences in the association between access to healthcare and health outcomes among older adults in china. BMC Geriatr. (2017) 17:151. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0538-9

58. Osborn R, Moulds D, Squires D, Doty MM, Anderson C. International survey of older adults finds shortcomings in access, coordination, and patient-centered care. Health Aff. (2014) 33:2247–55. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0947

60. World Health Organization. Disease Burden and Mortality Estimates: Cause-Specific Mortality, 2000-2016. Geneva: World Health Organization. (2018).

61. Currie J, Schwandt H. Inequality in mortality decreased among the young while increasing for older adults, 1990-2010. Science. (2016) 352:708–12. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1437

62. Aguila E, Kapteyn A, Smith JP. Effects of income supplementation on health of the poor elderly: the case of mexico. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2015) 112:70–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414453112

63. Damiani G, Federico B, Visca M, Agostini F, Ricciardi W. The impact of socioeconomic level on influenza vaccination among italian adults and elderly: a cross-sectional study. Prev Med. (2007) 45:373–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.007

64. Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. (2012) 367:1025–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202099

65. Zhang Y, Mao W, Xu L, Miao Z, Dong D, Tang S. Does health insurance matter to the use of health services for the elderly in china? A multiyear, nationwide, cross-sectional study. Lancet. (2018) 392:S53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32682-5

66. Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health Soc. (1973) 1973:95–124. doi: 10.2307/3349613

67. Shavers VL. Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. J Natl Med Assoc. (2007) 99:1013–23.

68. Duncan GJ, Daly MC, McDonough P, Williams DR. Optimal indicators of socioeconomic status for health research. Am J Public Health. (2002) 92:1151–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.7.1151

69. Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, et al. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. (2005) 294:2879–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879

70. Freedman VA, Grafova IB, Rogowski J. Neighborhoods and chronic disease onset in later life. Am J Public Health. (2011) 101:79–86. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178640

71. Fotso J, Kuate-Defo B. Measuring socioeconomic status in health research in developing countries: should we be focusing on households, communities or both? Soc Indicators Res. (2005) 72:189–237. doi: 10.1007/s11205-004-5579-8

72. Allin S, Masseria C, Mossialos E. Measuring socioeconomic differences in use of health care services by wealth versus by income. Am J Public Health. (2009) 99:1849–55. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141499

73. Assari S. Socioeconomic determinants of systolic blood pressure; minorities' diminished returns. J Health Econ Dev. (2019) 1:1.

74. Monnat SM. Race/ethnicity and the socioeconomic status gradient in women's cancer screening utilization: a case of diminishing returns? J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2014) 25:332. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0050

75. Smith ML, Towne S, Herrera-Venson A, Cameron K, Horel SA, Ory MG, et al. Delivery of fall prevention interventions for at-risk older adults in rural areas: findings from a national dissemination. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:2798. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122798

76. Smith ML, Towne SD, Herrera-Venson A, Cameron K, Kulinski KP, Lorig K, et al. Dissemination of chronic disease self-management education (CDSME) programs in the United States: intervention delivery by rurality. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:638. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060638

77. Ory MG, Smith ML. Research, practice, and policy perspectives on evidence-based programing for older adults. Front Public Health. (2015) 3:136. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00136

78. Heiman HJ, Artiga S. Beyond health care: the role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. Health. (2015) 20:1–10.

79. Miller DP, Bazzi AR, Allen HL, Martinson ML, Salas-Wright CP, Jantz K, et al. A social work approach to policy: implications for population health. Am J Public Health. (2017) 107:S243–S9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304003

80. Chen L, Yip W, Chang M, Lin HS, Lee SD, Chiu YL, et al. The effects of taiwan's national health insurance on access and health status of the elderly. Health Econ. (2007) 16:223–42. doi: 10.1002/hec.1160

81. Tsugawa Y, Jha AK, Newhouse JP, Zaslavsky AM, Jena AB. Variation in physician spending and association with patient outcomes. JAMA Int Med. (2017) 177:675–82. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0059

Keywords: socioeconomic status, healthcare access, access to care, healthy aging, older adults

Citation: McMaughan DJ, Oloruntoba O and Smith ML (2020) Socioeconomic Status and Access to Healthcare: Interrelated Drivers for Healthy Aging. Front. Public Health 8:231. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00231

Received: 14 November 2019; Accepted: 15 May 2020;

Published: 18 June 2020.

Edited by:

Colette Joy Browning, Federation University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Shane Andrew Thomas, Australian National University, AustraliaCathy H. Gong, Australian National University, Australia

Copyright © 2020 McMaughan, Oloruntoba and Smith. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Darcy Jones McMaughan, ZC5tY21hdWdoYW5Ab2tzdGF0ZS5lZHU=

Darcy Jones McMaughan

Darcy Jones McMaughan Oluyomi Oloruntoba3

Oluyomi Oloruntoba3 Matthew Lee Smith

Matthew Lee Smith