94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Public Health , 12 May 2020

Sec. Infectious Diseases – Surveillance, Prevention and Treatment

Volume 8 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00199

This article is part of the Research Topic Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, Clinical Management and Public Health Response View all 400 articles

Fabrizio Ricci1,2*

Fabrizio Ricci1,2* Pascal Izzicupo3

Pascal Izzicupo3 Federica Moscucci4

Federica Moscucci4 Susanna Sciomer4

Susanna Sciomer4 Silvia Maffei5

Silvia Maffei5 Angela Di Baldassarre3

Angela Di Baldassarre3 Anna Vittoria Mattioli6

Anna Vittoria Mattioli6 Sabina Gallina1

Sabina Gallina1Since the escalation of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, over a billion people across the world have faced restrictions due to varying degrees of confinement, and in the absence of a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2, massive public health interventions have been implemented to contain the outbreak. The lockdown set up in many countries to combat the COVID-19 epidemic entails unprecedented disruption of lives and work, determining specific risks related to mental and physical health in the general population, especially among those who stopped working during the current outbreak (1). The implementation of confinement policies to contain COVID-19 could be a catalyst for concealed mental and physical health conditions, further enhancing the effects of psychosocial risk factors, including stress, social isolation, and negative emotions that may act as barriers against behavioral changes toward an active lifestyle and negatively impact on global health, well-being and quality of life, ultimately resulting in result in a range of chronic health conditions (2, 3).

The World Health Organization (WHO) classified physical inactivity as the fourth leading risk factor accounting for 6% of global mortality, following hypertension (13%), smoking (9%) and diabetes (6%). The relationship between physical inactivity and obesity trends was quite evident since 1953 when the London Busmen Study showed that bus drivers who mainly sat during work presented with larger waist circumferences, higher levels of adiposity and increased risk of coronary events than bus conductors, who walked the aisles and climbed the stairs of double-decker buses (4).

Physical inactivity levels are rising in many countries with significant implications for the prevalence of non-communicable diseases and the general health of the population worldwide. The WHO recommends that adults accumulate at least 150 min of moderate to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) or 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity (VPA) throughout the week, cumulated in bouts lasting ≥10 min. This volume of physical activity (PA) is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality and a number of other healthcare benefits (5). Unfortunately, attained levels of daily PA are largely insufficient, especially in western countries.

Recent evidence suggests that sedentary behavior (SB) is independently associated with traditional CV risk factors and increased CV morbidity and global mortality, regardless of PA volume (6). SB is defined as any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents, while in a sitting, reclining or lying posture. Typical SB includes “screen time” (TV viewing, videogame playing, computer use), car-driving, and reading. Importantly, in a dose-response meta-analysis of 34 studies, including 1,331,468 community-dwelling participants, total sitting time volumes >8 h and 6 h/day were associated with increased risk of all-cause death and CV death, respectively, in PA adjusted analyses (7). For TV viewing time, an increased risk for all-cause and CV mortality was strongest above levels of 3–4 h/day, regardless of PA level (7).

Thus, physical inactivity and SB should be considered as separate entities with their unique determinants and health consequences, but with synergistic harmful effects on CV health (8).

While containing the spreading of the contagion as quickly as possible is the urgent public health priority, there have been few public health guidelines for the public as to what people can or should do in terms of maintaining their daily exercise or PA routines (9, 10). Safeguarding psycho-physical health in a lockdown situation is paramount, and special attention should be paid to elderly and pediatric populations. With advancing age, it becomes more difficult to reverse the effects of deconditioning of the musculoskeletal system. Children and adolescents have higher PA needs than adults, and these are more difficult to achieve during the quarantine period, also due to the influence of home environment (11). Both physical and social environmental factors operating within the home space are indeed important influences on SB and PA, especially for the pediatric population (12). Regarding adolescents, another point that warrants careful vigilance concerns the risks associated with increased total screen time, including the total hours spent on computer, TV and video gaming.

WHO just released guidance intended for people in self-quarantine without any symptoms or diagnosis of acute respiratory illness, containing a set of practical advice on how to stay active and reduce SB while at home. WHO further highlights how standard recommendations of 150 min of MVPA or 75 min of VPA per week, or a combination of both, can still be achieved even at home, with no special equipment and with limited space.

There is a robust health rationale for staying active at home in the current precarious environment, for all age groups. The following are general recommendations, unless otherwise specified.

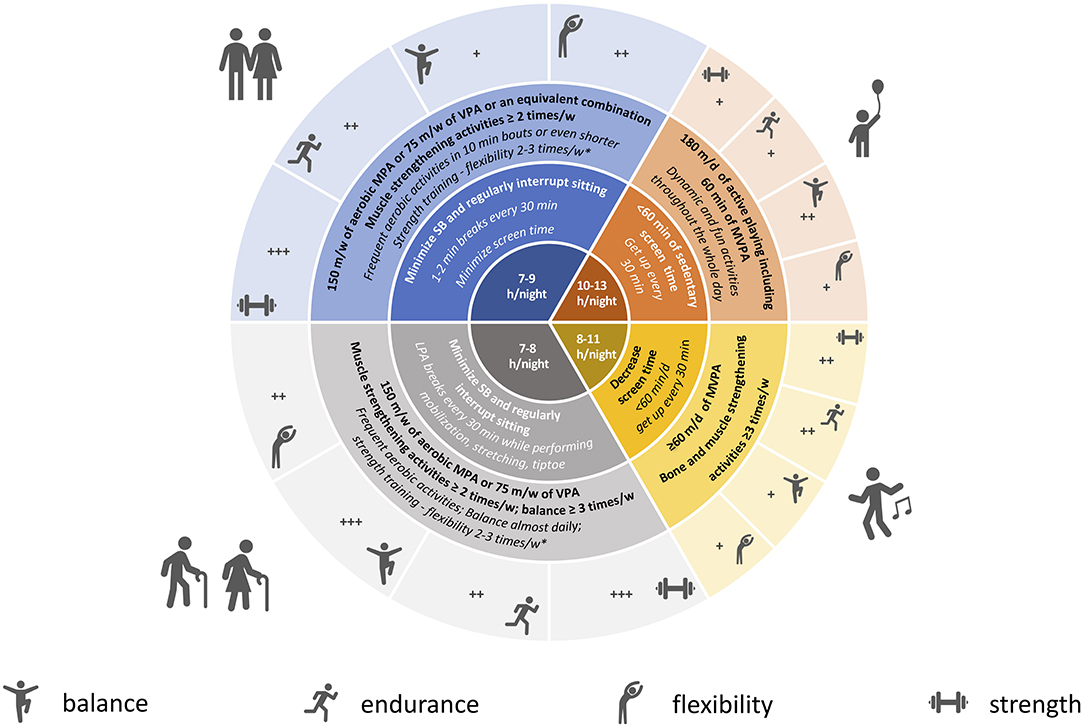

Specific recommendations and tips for children, adults, and elderly are further detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleep recommendations, and tips for COVID-19 quarantine period. Blue, adults; gray, older people; orange, preschooler; yellow, school-aged children and adolescents; Bold, international guidelines and recommendations; Italic, tips for quarantine period; PA, physical activity; SB, sedentary behavior; LPA, light-intensity physical activity; MPA, moderate-intensity physical activity; VPA, vigorous-intensity physical activity; MVPA, moderate to vigorous-intensity physical activity. In the central portion of the figure we reported recommended hours of sleep by age group. *Perform strengthening activities in non-consecutive days. +, ++, +++: relative importance of PA/exercise type for each age category. Dumbbell: muscle and bone strengthening activities; running: aerobic activities; monopodalic standing: balance exercise; bending: flexibility.

While recognizing the importance of confinement policies set up to contain COVID-19 pandemic, we firmly recommend the relevance of home-based programs for disruption physical inactivity and sedentary behavior as a critical behavioral strategy for the prevention of global health and consequences of psychosocial stress during the current lockdown.

FR and PI drafted the manuscript. All co-authors provided critical revision for important intellectual content.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Zhang SXW, Wang Y, Rauch A, Wei F. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 288:112958. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958

2. Lippi G, Henry BM, Bovo C, Sanchis-Gomar F. Health risks and potential remedies during prolonged lockdowns for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Diagnosis. (2020) 7:85–90. doi: 10.1515/dx-2020-0041

3. Lippi G, Henry BM, Sanchis-Gomar F. Physical inactivity and cardiovascular disease at the time of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2020). doi: 10.1177/2047487320916823. [Epub ahead of print].

4. Morris JN, Heady JA, Raffle PA, Roberts CG, Parks JW. Coronary heart-disease and physical activity of work. Lancet. (1953) 262:1053–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(53)90665-5

5. Puggina A, Aleksovska K, Buck C, Burns C, Cardon G, Carlin A, et al. Policy determinants of physical activity across the life course: a ‘DEDIPAC’ umbrella systematic literature review. Eur J Public Health. (2018) 28:105–18. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx174

6. Young DR, Hivert MF, Alhassan S, Camhi SM, Ferguson JF, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. Sedentary behavior and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2016) 134:e262–79. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000440

7. Patterson R, McNamara E, Tainio M, de Sa TH, Smith AD, Sharp SJ, et al. Sedentary behaviour and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. (2018) 33:811–29. doi: 10.1007/s10654-018-0380-1

8. Chomistek AK, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Lu B, Sands-Lincoln M, Going SB, et al. Relationship of sedentary behavior and physical activity to incident cardiovascular disease: results from the Women's Health Initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 61:2346–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.031

9. Chen P, Mao L, Nassis GP, Harmer P, Ainsworth BE, Li F. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): the need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. J Sport Health Sci. (2020) 9:103–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.02.001

10. Hall G, Laddu DR, Phillips SA, Lavie CJ, Arena R. A tale of two pandemics: how will COVID-19 and global trends in physical inactivity and sedentary behavior affect one another? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.005. [Epub ahead of print].

11. Sheldrick MP, Maitland C, Mackintosh KA, Rosenberg M, Griffiths LJ, Fry R, et al. Associations between the Home Physical Environment and Children's Home-Based Physical Activity and Sitting. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:4178. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16214178

12. Jaeschke L, Steinbrecher A, Luzak A, Puggina A, Aleksovska K, Buck C, et al. Socio-cultural determinants of physical activity across the life course: a 'Determinants of Diet and Physical Activity' (DEDIPAC) umbrella systematic literature review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2017) 14:173. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0627-3

Keywords: physical activity, sedentary behavior, cardiovascular prevention, COVID 19, quarantine, coronavirus

Citation: Ricci F, Izzicupo P, Moscucci F, Sciomer S, Maffei S, Di Baldassarre A, Mattioli AV and Gallina S (2020) Recommendations for Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behavior During the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Front. Public Health 8:199. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00199

Received: 15 April 2020; Accepted: 01 May 2020;

Published: 12 May 2020.

Edited by:

Alexander Rodriguez-Palacios, Case Western Reserve University, United StatesReviewed by:

Dario Mendoza-Romero, Fundación Universitaria del Área Andina, ColombiaCopyright © 2020 Ricci, Izzicupo, Moscucci, Sciomer, Maffei, Di Baldassarre, Mattioli and Gallina. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fabrizio Ricci, ZmFicml6aW8ucmljY2lAdW5pY2guaXQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.