- School of Health, Medicine and Applied Sciences, Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, QLD, Australia

Introduction: Resilience is enabled by internal, individual assets as well as the resources available in a person's environment to support healthy development. For Indigenous people, these resources and assets can include those which enhance cultural resilience. Measurement instruments which capture these core resilience constructs are needed, yet there is a lack of evidence about which instruments are most appropriate and valid for use with Indigenous adolescents. The current study reviews instruments which have been used to measure the resilience of Indigenous adolescents in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States (the CANZUS nations). The aim is to provide guidance for the future use of instruments to measure resilience among Indigenous adolescents and provide recommendations for research to strengthen evidence in this area.

Method: Instruments were identified through a systematic search of resilience intervention and indicator studies targeting Indigenous youth from CANZUS nations. The studies were analyzed for information on the constructs of resilience measured in the instruments, their use with the targeted groups, and their psychometric properties. A second search was conducted to fill in any gaps in information. Instruments were included if they measured at least one construct of resilience reflecting individual assets, environmental resources, and/or cultural resilience.

Results: A total of 20 instruments were identified that measured constructs of resilience and had been administered to Indigenous adolescents in the CANZUS nations. Instruments which measured both individual assets and environmental resources (n = 7), or only environmental resources (n = 6) were most common. Several instruments (n = 5) also measured constructs of cultural resilience, and two instruments included items addressing all three constructs of individual assets, environmental resources, and cultural resilience. The majority of the reviewed studies tested the reliability (75%) and content or face validity (80%) of instruments with the target population.

Conclusion: There are several validated instruments available to appropriately measure constructs of resilience with Indigenous adolescents from CANZUS nations. Further work is needed on developing a consistent framework of resilience constructs to guide research efforts. Future instrument development and testing ought to focus on measures which include elements of all three core constructs critical to Indigenous adolescent resilience.

Introduction

Resilience is a concept that is increasingly used to understand the factors and processes that contribute to the maintenance of well-being, effective coping, and success in the face of life's challenges (1, 2). As a strengths-based concept concerned with understanding and enhancing protective and promotive factors (1), resilience is a promising construct for researching Indigenous adolescent health and well-being. To better understand resilience for Indigenous adolescents and identify the impact of resilience-enhancing interventions, appropriate measurement instruments are needed which capture core constructs of resilience. Furthermore, these measurement instruments need to be shown to be valid, and demonstrate that they can reliably predict relevant outcomes for this population (3). In other words, measurement instruments for Indigenous adolescents need to be psychometrically sound and be shown to operationalize Indigenous concepts of well-being (4).

To be able to assess the validity and reliability of measurement instruments used to assess Indigenous adolescent resilience, we must first clearly identify the constructs of resilience which are known and often included in measurement instruments. Reaching such clarity is difficult considering there is no one definition or theoretical basis for resilience that is consistently agreed upon or used (5). This goal is also complicated by the fact that resilience is highly dependent on a person's context and culture (6, 7). Therefore, measurement instruments are required that take account of cultural diversity and/or that are tailored to specific populations and/or settings.

This review grapples with this complexity in an attempt to: increase understanding of the constructs of resilience relevant to Indigenous adolescents; appraise the inclusion of such constructs in measurement instruments which have been utilized to study Indigenous adolescent resilience; and, evaluate the psychometric properties of said instruments for use with the Indigenous adolescent populations with which they were used.

Background

Constructs of Resilience

Resilience has been conceptualized as a set of personality traits which assist a person to adapt positively through adversity (8). However, theorists argue that rather than a static individual characteristic, resilience can be understood as a dynamic process that is situationally and contextually embedded (5, 9, 10). Such a socioecological perspective of resilience recognizes that there are numerous protective and promotive assets and resources that serve to enhance resilience (11).

Individual assets are those intrapersonal and interpersonal skills and qualities that enable people to deal positively with emotions, work toward their desired future and maintain positive social connections. Assets include skills and qualities such as: self-efficacy; self-esteem and confidence; distress tolerance; stress management; communication skills; empathy; a balanced perspective; optimism; problem solving; goal planning and future orientation; personal awareness; and strong racial or ethnic identity (1, 12–14). Environmental resources are the support and opportunities available in a person's environment that enable positive development and successful adaptation. Such resources include: positive peer support and influence; supportive adult role models; strong family support and kinship networks; connection with members of one's cultural or social group; as well as opportunities to engage in socially valued and meaningful roles and activities (12, 14). Individual resilience-promoting assets interact with and are influenced by the resources available in a person's environment (15, 16) across multiple systems including families, peers, communities and schools (7, 12).

Concepts of resilience have existed for many Indigenous peoples even before the term resilience was coined (17). While many of the resilience-promoting individual assets and environmental resources previously outlined are recognized as universally important (18–21), there are several key cultural distinctions in the way in which Indigenous peoples conceptualize resilience (10, 22, 23). For example, family and community level factors contribute significantly more to Indigenous peoples' resilience than do individual factors (22). Cultural resilience is another key construct which may be more important for Indigenous peoples than individual-level factors (19, 22). Cultural resilience is a term that has been used to describe the degree to which the strengths of a person's culture support and promote coping (24). Cultural resilience can be strengthened through cultural connectedness, demonstrated by factors such as: a strong Indigenous identity; connections to family, community, cultural traditions, and the natural environment; and Indigenous worldviews and spirituality (17, 20, 21, 25, 26). Cultural connectedness is an important protective factor for Indigenous adolescent mental health and well-being (22, 27), and has been shown to protect against substance abuse, mental distress and suicidal behavior, and to increase prosocial outcomes such as improved socio-economic indicators and academic achievement (22, 28, 29).

Measuring Resilience

The diversity of definitions and theories of resilience has led to the development of many measurement instruments which incorporate various combinations of individual, family, and social protective and/or risk factors (30). However, many international resilience instruments are framed within Western epistemologies and may not be valid or reliable for Indigenous people who hold differing perspectives and values (29, 31–33). Considering that constructs of resilience are culturally bound, measurement instruments are needed which are reflective of Indigenous conceptualizations and language (34, 35).

Several recent reviews of resilience measurement tools have collectively identified 19 separate instruments (30, 36, 37), many of which measure different constructs (37). Several of these instruments consider only the individual personality traits that contribute to resilience and exclude environmental resources. One review found that of four resilience scales that specifically targeted adolescents, all but one assessed only individual traits (37). Another review found that the majority of measurement instruments focused on resilience at the individual level, with only five instruments identified that adequately demonstrated a socioecological concept of resilience (30). Considering the importance of family and community level factors for Indigenous peoples resilience (22), this calls into question whether such individually focused measurement instruments would accurately measure Indigenous adolescent resilience.

Furthermore, there are examples of instruments which measure constructs of cultural resilience (25, 27); these factors are generally not measured in commonly used and recognized resilience instruments (30, 36, 37). One exception is the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM) which assesses for cultural and contextual influences on resilience (38) and has proven validity with Canadian Aboriginal youth (39) and with Indigenous Australian boarding school students (40). Its reliability and validity with other Indigenous adolescent groups is unknown.

The Present Study

This review examines the international literature on measurement instruments that have been used with Indigenous adolescents to measure key constructs of resilience. The measurement instruments included for analysis were drawn from a systematic review of psychosocial resilience intervention and indicator studies with Indigenous adolescents in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States [CANZUS nations (41)]. Specifically, we examine which constructs of resilience are reflected in the reviewed instruments and whether they capture resilience constructs that have been documented as important to Indigenous people. This review also examines the reliability and validity of the assessed measurement instruments with the Indigenous adolescent populations with whom they are used. Key issues in measuring resilience for this population group will be discussed.

Methods

The measurement instruments reported in this exploratory review were located in publications found in a literature search conducted to identify relevant studies which aimed to either improve or measure the resilience of Indigenous adolescents in the CANZUS nations. Studies were included in this review if they reported the development, testing or utilization of instruments to measure resilience constructs with Indigenous adolescents. A separate literature review has been written by the authors on interventions to improve Indigenous adolescent resilience.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The reviewed measurement instruments were taken from studies found in a literature search of peer-reviewed and gray literature published in English from January 1st 1990 to May 31st 2016 inclusive. The start date coincides with the third wave of resilience studies that focused on enhancing resilience by intervention (42). Publications were included if they met the following criteria:

1. The study was from Australia, Canada, New Zealand or the United States;

2. The study was focused on resilience as it pertains to Indigenous adolescents; and,

3. The study included at least one instrument which measured constructs of resilience for Indigenous adolescents.

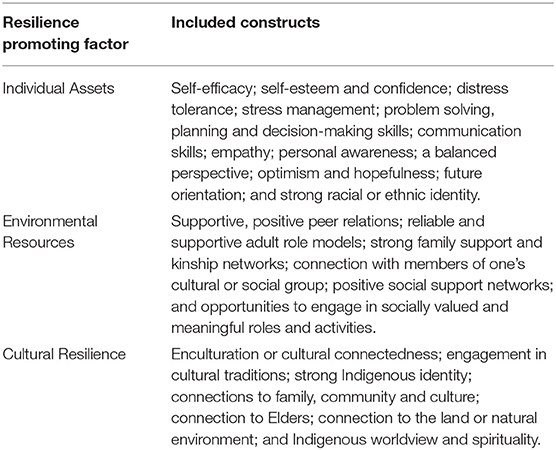

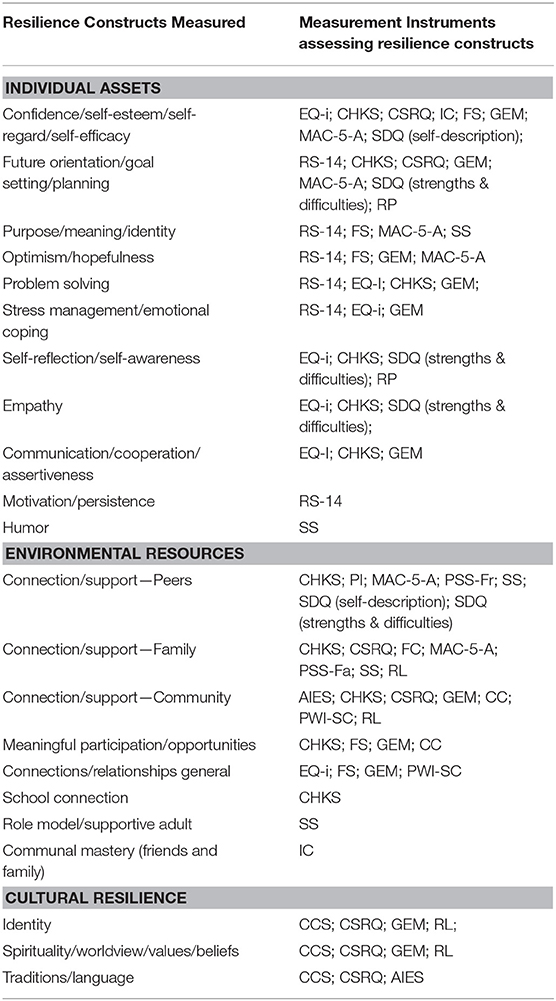

Included publications were screened to identify measurement instruments which had been used to assess constructs of resilience with Indigenous adolescent populations. The constructs of resilience against which the measurement instruments were screened were identified through a review of the relevant literature. Key resilience publications revealed a range of resilience constructs which we grouped according to whether they reflected individual assets, environmental resources, or cultural resilience constructs for Indigenous people. See Table 1 for the constructs of resilience used to determine inclusion of measurement instruments. Measurement instruments were included for analysis if they assessed at least one construct of resilience identified in Table 1.

Search Strategy

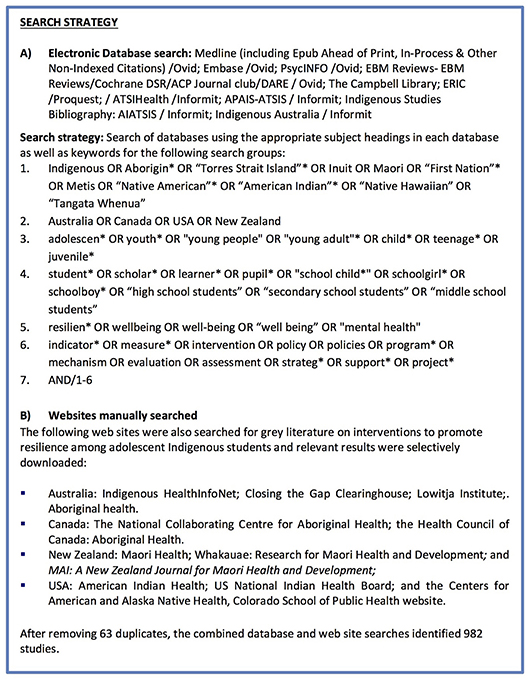

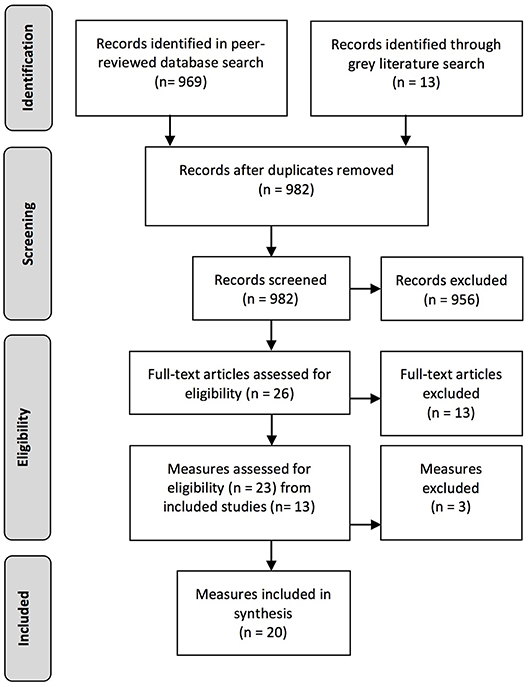

The search strategy comprised five steps. See Figure 1 for summary of the search strategy.

Step 1: An expert librarian (MK) searched 11 relevant electronic databases identifying 969 references excluding duplicates.

Step 2: Relevant gray literature in 11 clearinghouses and websites across the four countries were searched for additional literature, locating 13 more publications.

Step 3: The abstracts of the 982 identified references were manually examined, with 25 studies identified for examination of full text articles. One additional relevant study known to the authors which did not appear in the search results for unknown reasons, was also included bringing the total number of studies to 26.

Step 4: The full-text articles of the 26 references were examined in further detail to identify the use of measurement instruments which assessed constructs of resilience. Thirteen references were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria leaving 13 publications with a total of 23 measurement instruments.

Step 5: The included studies were examined for detail on the resilience constructs measured and instrument psychometric properties. As several of the studies from the initial search results did not include such details, a second targeted search was performed to identify further studies reporting details of specific instrument items and psychometric development and testing of the identified measurement instruments. Similar to the method employed by Ahern et al. (36), first we searched for the references on the identified measurement instruments cited in the studies included. We then conducted searches of the identified measurement instrument name, looking specifically for studies on instrument development and testing, coupled with the search terms adolescent and Indigenous. Three measurement instruments were excluded because they had either not been validated, or information on the psychometric properties of the instruments was not reported or could not be found in the second search. A total of 20 validated measurement instruments which assessed constructs of resilience for Indigenous adolescents were included for final analysis. See Figure 2 for a flow chart of our PRISMA search strategy (43).

Identification, Screening, and Inclusion of Publications

The search results of both peer-reviewed and gray literature were imported into the bibliographic citation management software, Endnote X7 with duplicates removed. Titles and abstracts of publications were screened by one author (CJ); those which did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded. The full texts of the remaining publications were retrieved and screened by blinded reviewers (RB, JM). Inconsistencies in reviewer assessments were resolved by consensus. Included publications were screened by one author (CJ) for instruments which measure constructs of resilience.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data on the included measurement instruments found in the original and second search were extracted from relevant studies. For each instrument, data was extracted on the instrument type, target population and any samples utilized in studies. Data were also extracted on the explicit constructs that the included instruments measured. This was achieved by assessing individual instrument items when available, or whatever information was reported regarding the constructs measured in the relevant studies. Sometimes these very clearly reflected the resilience constructs provided in Table 1, yet often constructs were expressed using different language to that identified in the literature. Therefore, an analysis process was undertaken in which the constructs identified in instruments were compared with the core resilience constructs to identify commonalities. Details on the identified constructs measured in each instrument and the related resilience constructs can be found in the Supplementary Table 1. Each instrument was also assessed for its reported validity and reliability with Indigenous adolescents or other populations. Data on measurement validity and reliability found in the reviewed studies was extracted and is reported in detail in Supplementary Table 1.

Results

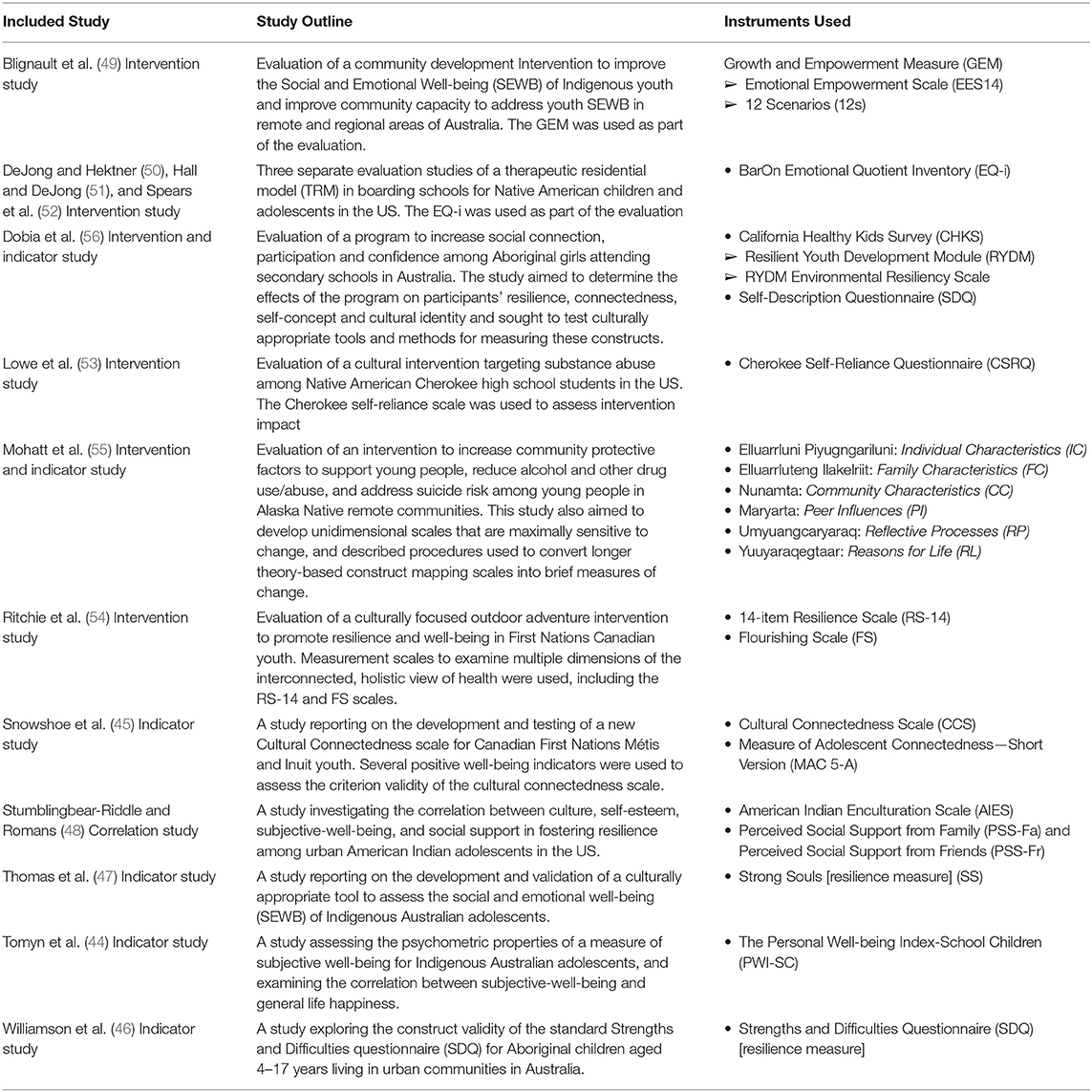

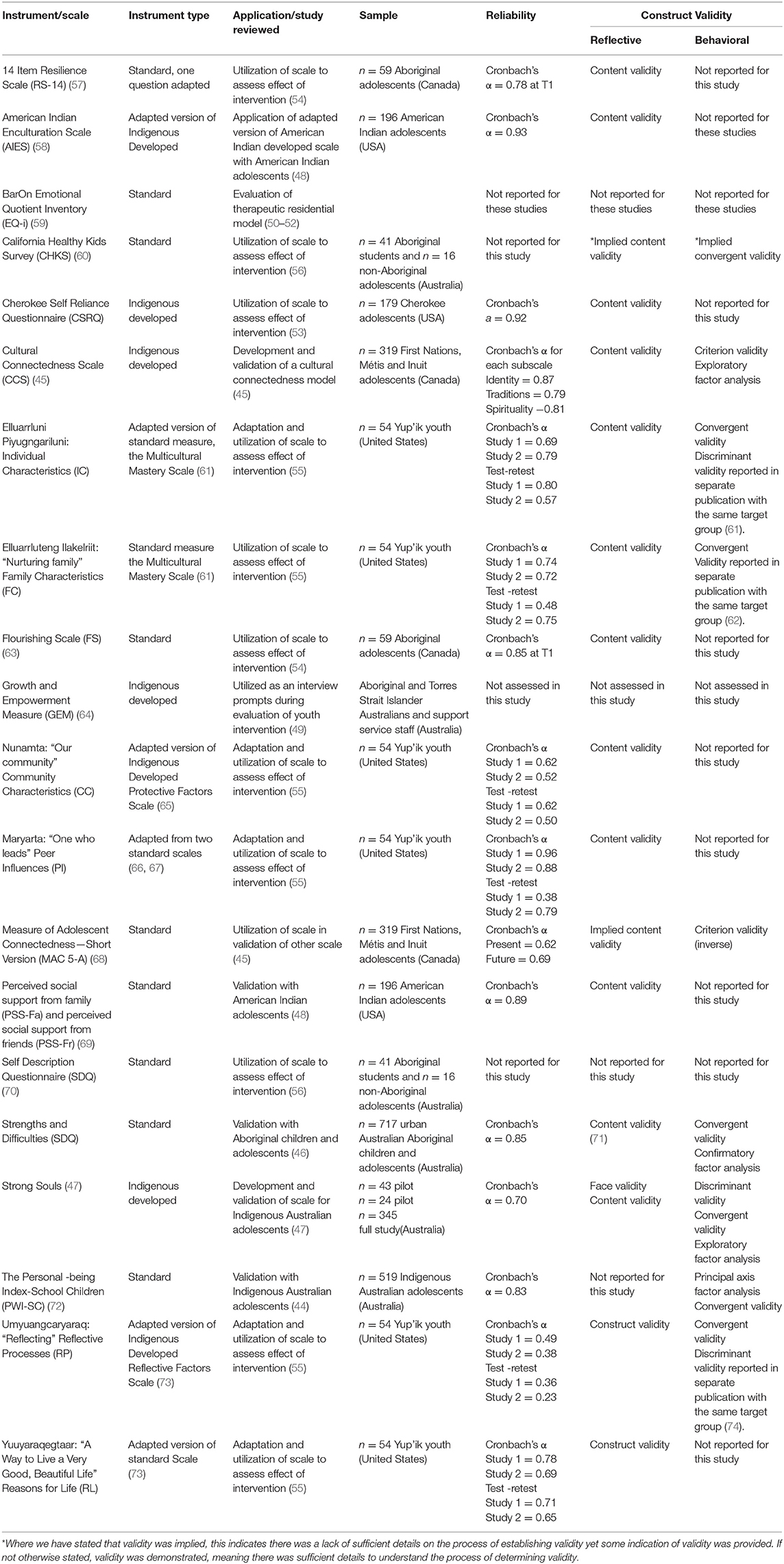

The 13 reviewed studies included four which focused on the development and testing of resilience measurement instruments (44–47); one correlation study that examined the relationship between various instruments measuring resilience constructs (48); and eight intervention studies which utilized measurement instruments reflecting constructs of resilience for Indigenous adolescent populations (49–54), two of which were also concerned with the development and testing of appropriate measurement tools for the target populations (55, 56). Some of these studies also utilized additional instruments for measuring other mental health and well-being constructs, however these were not included in this review as they did not reflect the constructs of resilience previously specified (see Table 1). Details of the relevant studies are provided in Table 2.

Constructs of Resilience Measured

Of the 20 included measurement instruments, seven measured constructs of resilience consistent with the ecological definition which incorporates both individual assets and environmental resources (CHKS; SDQ-self-description; IC; FS; MAC-5A; SS; SDQ-strengths and difficulties). In contrast, there were six instruments which measured only environmental resources (FC; CC; PI; RL; PSS-Fr & PSS-Fa; PWI-SC) and three which only assessed individual assets (EQ-i; RP; RS-14). We also found three instruments which were focused on Indigenous specific constructs of cultural resilience (CCS; AIES), one of which also measured environmental resources (RL). Lastly, two identified measurement instruments addressed all three constructs of resilience, including individual assets, environmental resources, and cultural resilience (GEM; CSRQ).

The most common individual assets addressed across measurement instruments were those related to self-esteem/confidence/self-regard/self-efficacy (n = 8), and a future orientation, goal setting and planning (n = 7). Other common individual assets related to optimism and hopefulness (n = 4), purpose, identity and meaning (n = 4), problem-solving (n = 4), and self-reflection/self-awareness (n = 4). Ecological resilience constructs were very well-represented across the included instruments with connection to/support from community (n = 8), peers (n = 7), and family (n = 7) being common. A further four measurement instruments assessed opportunities and meaningful participation. Indigenous-specific cultural resilience constructs were included in numerous Indigenous-developed measurement instruments. Most commonly assessed was identity (n = 4) and Indigenous spirituality, worldviews, values and beliefs (n = 3). Table 3 shows the resilience constructs reflected in the reviewed measurement instruments, detailing which instruments assessed each construct.

Two of the reviewed instruments (SDQ-Strengths and Difficulties and SS) included deficit-based items assessing issues such as anxiety, depression, suicide risk, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems alongside strengths-based resilience items. Indeed, both of these instruments focused more on assessing problems, with Strong Souls (SS) including 9/25 resilience-focused items and 16/25 deficit-focus items, and SDQ including 11/25 strengths-based items and 14/25 deficit-focused items. Three other instruments reviewed (PI, RP, and RL) addressed risk factors concerning alcohol use and suicidality, yet items were framed from a strengths-based perspective, assessing resilience assets, and resources which could protect against these risks.

Psychometric Properties of the Included Measurement Instruments

Of the 20 measurement instruments reviewed, eight (40%) were un-adapted standard instruments (EQ-I; CHKS; FS; MAC5-A; PSS-Fa & PSS-Fr; SDQ (self-description); SDQ (strengths and difficulties); PWI-SC) and five (25%) were adaptations of standard instruments (RS-14; IC; FC; PI RL). Three instruments (15%) were developed specifically for the use with Indigenous youth (CRSQ, CCS, SS), three (15%) were adaptations of instruments developed for use with Indigenous adults from the same target population (AIES; CC; RP), and one was an un-adapted instrument developed for Indigenous adults from the same target population (GEM). All eight instruments (40%) reviewed that had been adapted from their original form had been examined for reliability and some form of construct validity. Reliability, in the form of internal consistency measured by Cronbach's α, was examined for 16 (80%) of the instruments, and one study (55), which reported on six instruments also examined test-retest reliability. Excellent reliability was demonstrated for three instruments, good reliability for six, and acceptable reliability for six. However, two instruments were found to have questionable reliability, and one poor (see Table 4). Eight of the measures that reported Cronbach's α were examined with sample sizes of <100, and this included those with lower reported levels of α. Construct validity was considered in terms of both the behavior of the instrument and whether it reflects the construct being measured. Content or face validity was assessed for 16 of the instruments (80%) with community steering or advisory groups. Ten instruments (50%) demonstrated validity, as reported through examinations of convergent or discriminant validity, or some form of factor analysis. The Psychometric properties for each measurement are briefly outlined in Table 4.

Supplementary Table 1 provides greater detail on the resilience constructs assessed and psychometric properties of each measurement instrument.

Discussion

The reviewed studies reported measurement instruments to assess Indigenous adolescent resilience. The resilience constructs measured varied between studies, as did the reliability and validity of the instruments for use with the target population. We will discuss some of the key themes and issues associated with both the constructs of the instruments and their psychometric properties in turn.

Constructs of Resilience

There is a lack of clarity and consistency in the literature regarding key definitions and concepts of resilience. This lack of clarity and consistency is reflected in resilience measurement instruments, many of which assess resilience enhancing assets pertaining to individuals, yet do not assess factors in one's environment that help to support and build resilience (30, 37). This is incongruent with much of the current resilience literature which holds that the resources and support in one's environment are critical to an individual's resilience (5, 9–11, 15, 16). There is a need for development of a clear framework on the constructs that are key to resilience to help bring consistency to this research field. Such a framework should elucidate the central role that both individual and environmental level factors play in promoting resilience. For Indigenous adolescents, such a framework would also need to incorporate cultural resilience constructs specific to the participating Indigenous peoples.

Research studies indicate that environmental resources such as connection to family and community are particularly important for Indigenous peoples, and may have a greater impact on their overall resilience than individual factors (22, 33). It was positive to see that the majority of instruments reviewed in this study included items for both individual assets and environmental resources. Although less common than measures of environmental resources, constructs of cultural resilience were also present in several instruments, particularly those developed by and for Indigenous peoples. This is important considering the central role that culture plays in Indigenous people's resilience (19, 22, 27).

Cultural resilience is understood to be about the ways in which the strengths of one's culture support and promote coping (24). However, various context dependent factors influence the ways in which people make meaning of, and take strength from culture (75). This makes measuring cultural resilience a challenge because it manifests differently across diverse Indigenous populations (19, 20), generations (76), and contexts (40). Therefore, further clarification of what cultural resilience means, and how it is expressed and experienced for different Indigenous peoples in different contexts is needed.

The constructs of cultural resilience identified in the reviewed measures included: identity; spirituality/worldviews/values/beliefs; and, traditions/language. These constructs are consistent with components of the related concept of cultural connectedness, or enculturation, which is understood to strengthen cultural resilience. The components of cultural connectedness identified in North American literature include: traditional activities; cultural identification; and traditional spirituality (77). These cultural connectedness components have been found to be valid for Canadian First Nations, Métis and Inuit youth (45), and Native American people in the US (77). However, no research examining the validity of this conceptualization of cultural connectedness with other Indigenous populations was found.

The Growth and Empowerment (GEM) instrument developed for Indigenous Australians included items related to Indigenous identity and spirituality. This suggests that Indigenous identity and spirituality may be important aspects of cultural connectedness, and therefore cultural resilience, among diverse groups of Indigenous peoples in different countries, and contexts. Nevertheless, further research into the similarities and differences in constructs of cultural resilience among different groups of Indigenous people internationally is needed to better understand this complex, context dependent concept.

Of all the reviewed instruments, only two [Growth and Empowerment (GEM) measure and the Cherokee Self Reliance Scale (CSRS)] included items assessing all three core constructs of individual assets, environmental resources, and cultural resilience constructs. Even though these are the most comprehensive measures reviewed, they were both developed for particular Indigenous contexts and may not be applicable to other populations. Further research into whether the GEM and CSRS could be appropriate for use other Indigenous adolescent populations is warranted. Additionally, future development of measurement instruments to assess Indigenous adolescent resilience should aim to ensure that instruments cover all core resilience constructs.

Interestingly, only two of the included studies incorporated instruments which have been previously identified as measures of resilience (30, 37); these were the California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS) and the 14 item Resilience Scale (RS-14). All other included instruments measured constructs of resilience but were not identified explicitly as resilience measures. Concepts of resilience are closely related to and overlap with other constructs of well-being such as social and emotional learning and development; hence, there are a range of instruments which measure key constructs of resilience that are not explicitly identified as such. Given that many recognized resilience instruments do not measure a socio-ecological perspective of resilience and, even less so, constructs of cultural resilience, other instruments that do so may be more appropriate for measuring resilience among Indigenous adolescents.

Instrument Reliability and Validity

One key factor limiting evidence-based practice interventions to improve well-being for Indigenous people is the lack of well-validated instruments. There is a recognized ongoing need to test and develop culturally appropriate measures to ensure they are psychometrically sound and operationalize Indigenous concepts of well-being (4). The studies revealed many different measurement instruments which have been used to study resilience with Indigenous adolescent populations across the CANZUS nations. It is promising that so many of the included measurement instruments have been tested and shown to be reliable and valid with the relevant target population. Sixteen of 20 measurement instruments assessed (80%) tested the reliability and some form of validity with the Indigenous adolescent populations with which they were being utilized.

The measurement of instrument reliability using Cronbach's α is positive, with the majority of reviewed instruments demonstrating acceptable to excellent reliability. However, Cronbach's α is not always appropriate, particularly in small samples with non-normal distributions (78, 79). Forty percent of the instruments reporting Cronbach's α were examined with sample sizes of <100 (78). This may have affected instrument reliability in some cases. To improve assessments of instrument reliability, it is important that testing is done with adequate samples.

Promisingly, content or face validity was assessed for the majority (80%) of the instruments in the studies in which they were employed. Studies' research advisory groups or steering committees' provided validation that the instruments were understandable and accurately reflected the relevant constructs in the specific cultural contexts in which they were being applied. Behavioral validity in the form of convergent or discriminant validity, or through factor analyses, was also demonstrated in 50% of instruments. The absence of reporting behavioral validity for the other instruments may be due to intervention studies included not reporting on the examination of the relationship of resilience to related constructs. Similarly, to reduce participant burden in studies of adolescents over time, additional scales of related constructs may not be included unless necessary to address the primary research question.

Other considerations in deciding on appropriate measurement instruments are the effect of age, and the test-retest reliability of instruments. Differences in comprehension levels between adolescents and children (80) and even between younger and older adolescents can differ markedly (40). Therefore, when determining the appropriateness of measurement instruments, the potential impacts of age variation should be tested. This was not examined in any of the studies reviewed. Furthermore, test-retest reliability was only examined for a handful of instruments, and several of those identified less than optimal test-retest reliability. Good test-retest reliability is important for measurement instruments intended to be used to assess changes over time and intervention outcomes. Therefore, it needs to be considered in the selection and testing of instruments for intervention studies

Due to the unique and contextualized conceptualizations of health and well-being held by Indigenous peoples, measurement instruments need to be comprehensible, and reflective of local understandings. For this reason, there is an imperative to develop measurement instruments which specifically reflect Indigenous constructs (44). Of all the instruments reviewed, 15% were developed specifically for use with Indigenous youth, and 20% for Indigenous adults, based on research on localized concepts of health and well-being, and how they can be measured. This kind of instrument development ensures a high level of content validity and cultural appropriateness which is highly important for Indigenous peoples.

However, there are also other approaches to measurement which can be equally valid. For example, in a recent study on the development of a local resilience and risk survey for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, participants considered survey instruments developed for and/or by Indigenous Australians to be too complex or of less relevance than international measurement instruments (40). It was concluded that internationally validated instruments can be useful for measuring Indigenous adolescent well-being if they are adapted in collaboration with local communities and services and tested with local Indigenous participants (40). Considering that changes to wording or response options can result in large differences in the performance of instruments (81), the importance of testing the psychometric properties of modified or adapted instruments cannot be underestimated. In the reviewed studies, all eight adapted instruments had been examined for reliability and some form of validity.

Another consideration for the study of resilience measurement instruments for Indigenous adolescents is that localized measurement instruments, either developed or adapted for selected groups, are often not appropriate for use with the general population, and consequently data cannot be compared to that of the general population (72). An alternative is to determine the validity of mainstream instruments with Indigenous populations. This allows for the comparison of the psychometric performance of scales and health indicators or outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous samples (44, 82). Two studies (44, 46) assessed the psychometric properties of mainstream instruments with Indigenous Australian children and adolescents.

This review shows that the use of tailored, adapted and standardized measurement instruments are all potentially useful approaches to measuring Indigenous adolescent resilience. However, it is important to recognize the tension that exists between having tailored measures for use with particular populations in their unique contexts, and testing standardized instruments to allow for comparability across populations.

Measuring Resilience and Risk

Resilience, as a strengths-based construct, should arguably be measured using strengths-based instruments. However, we found some measures which assessed a greater percentage of deficit-based than strengths-based items. Determining the balance between risk related and resilience related questions when developing and choosing survey instruments can be difficult (40). Often it is important to assess for risk factors, such as suicide risk, among Indigenous adolescents, but measures of resilience also require the use of instruments which have a significant focus on strengths-based constructs. Perhaps in response to the limited availability of measures which assess an appropriate range of resilience promoting factors, several of the included studies (45, 48, 54–56), utilized multiple measurement instruments to assess various constructs related to adolescent well-being and resilience. This is one potentially feasible approach to measuring resilience among Indigenous adolescents but consideration need to be given to participant burden when administering large and complex questionnaire packages.

There are different approaches which can be taken in risk assessment. Many mainstream approaches to assessing risk may be culturally incongruent and inappropriate for use with Indigenous communities (83). To increase effectiveness, risk assessment must also be formulated in response to local cultural meanings and practices. Culturally sensitive and strengths-based approaches to assessment of risk factors was demonstrated by Mohatt et al. (55) in the Peer Influences (PI), Reflective Process (RP), and Reasons for Life (RL) instruments; PI measured protective peer influences in relation to drug and alcohol use by assessing peer attitudes that discourage alcohol or other drug use; RP assessed reflective processes about the potential consequences of alcohol use and abuse on self, family, and the Alaskan Native way of life; and RL assessed reasons why a person would not want to end their life when feeling suicidal, without mentioning suicide, emphasizing cultural beliefs and experiences that make life more enjoyable, worthwhile and meaningful. These measures were deemed by the communities involved to be more culturally sensitive than mainstream risk measures. The appropriateness and validity of such strengths-based risk assessment is something worth investigating with other Indigenous youth across the CANZUS nations.

Limitations

Although the reviewed measurement instruments were identified through a comprehensive search strategy designed to identify the majority of peer- and non-peer reviewed literature, it is possible that some relevant publications were not found. There is a risk of publication bias considering that studies which do not find positive results are often not published. It is also recognized that many publications are not available in the most accessible international databases (84). Furthermore, as the authors are based in Australia, with longstanding skills and experience in Australian Indigenous health equity research, several known Australian Indigenous focused data bases were searched. Equivalent Indigenous health specific databases for the other included countries are not known by the authors. Additionally, other instruments known to the authors were included. As the authors are more familiar with Indigenous developed or tailored measurement instruments in the Australian context, this may have resulted in a bias toward Australian instruments.

Although terms for measures and indicators were included, because the original search was focused on resilience intervention studies, this may have also limited the results. This was not intended to be a comprehensive review. However, considering the range of instruments found which were not identified as resilience instruments, a further, more in-depth search specific to terms associated with constructs of resilience would likely reveal further instruments which measure constructs of resilience and have been utilized and validated with Indigenous adolescents.

Summary

Core constructs of resilience for Indigenous adolescents include those relating to environmental resources and cultural resilience, as well as individual strengths and assets. To effectively measure resilience with this population group, instruments are needed which reflect and capture all core constructs. The reviewed instruments by and large reflected core resilience constructs, however only two included items reflecting all three core constructs. To assess a range of resilience constructs, many studies used multiple measurement instruments. While this is one approach to measuring Indigenous adolescent resilience, consideration needs to be given to potential participant burden. Future development, adaptation and use of instruments to measure Indigenous adolescent resilience should aim to ensure that all core resilience constructs are captured.

Instruments which assess core resilience constructs, but are not explicitly identified as resilience measures, are arguably more appropriate than known resilience measures which only capture individual resilience supporting assets. Considering the importance of environmental resources and cultural resilience in Indigenous people's resilience, measurement instruments which do not assess these may not adequately measure resilience for Indigenous adolescents. Furthermore, future studies should prioritize the assessment of cultural resilience as a core part of resilience, alongside environmental resources and individual assets. However, further research attention is needed toward understanding and clarifying specific constructs of cultural resilience in different contexts, and their similarities and differences.

The majority (75%) of the reviewed publications reported testing of instrument reliability with the target population. However, the reliability statistics of some instruments were less than acceptable, and may have been affected by small samples sizes. To gain a clearer picture of instrument reliability, it is important that testing is done with larger samples. Attention also needs to be paid to the test-retest reliability of instruments if their intended use is to measure the impacts of interventions or levels of resilience over time.

Content or face validity was assessed for the majority (80%) of the instruments in the studies in which they were employed. Research advisory groups or steering committees' provided validation that the instruments are understandable and accurately reflect the relevant constructs in the specific cultural contexts they were being applied. While using instruments developed specifically for Indigenous adolescent populations is one way to ensure strong validity and reliability, this may not always be the best approach. The adaptation of instruments designed for other populations is another valid approach if shown to be psychometrically sound. Also, the benefits of testing the reliability and validity of non-adapted mainstream instruments with Indigenous people, is that if shown to be reliable and valid they can facilitate the comparison of intervention effects with those of their mainstream counterparts.

Conclusion

This review demonstrates that there is a range of instruments which have been successfully used to measure resilience with Indigenous adolescent populations in CANZUS nations. While the majority of these instruments are not well-established and commonly used resilience measures, they strongly reflected the core constructs of resilience for Indigenous people. The majority of reviewed instruments were also shown to be reliable and valid for use with the target populations. When choosing instruments to measure Indigenous adolescent resilience, key considerations are the selection of instruments which reflect core resilience constructs and the testing of instrument reliability and validity. This review provides examples of potential instruments which could be used in future studies, as well as guidance for the testing and development of further instruments to measure Indigenous adolescent resilience.

Author Contributions

RB and JM designed the study protocol used for the search. CJ was responsible for the initial screening of search results and data extraction for included studies and RB and JM both completed second screening. CJ was primarily responsible for writing the review draft, and RB and EL contributed to the drafting of the review. CJ, RB, JM, and EL all contributed feedback and edited the review. All authors have approved the final version for submission and agree to be accountable for all aspects of this work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Mary Kumvaj (MK) in conducting the literature search.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00194/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

AIES, American Indian Enculturation Scale; CANZUS, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, United States; CC, Nunamta: Community Characteristics; CCS, Cultural Connectedness Scale; CHKS, California Healthy Kids Survey; CRSQ, Cherokee Resilience Scale Questionnaire; CYRM, Child and Youth Resilience Measure; EQ-i, BarOn Emotional Quotient Inventory; FC, Elluarrluteng Ilakelriit: Family Characteristics; FS, Flourishing Scale; GEM, Growth and Empowerment Measure; IC, Elluarrluni Piyugngariluni: Individual Characteristics; MAC 5-A, Measure of Adolescent Connectedness – Short Version; PI, Maryarta: Peer Influences; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; PSS-Fa, Perceived Social Support from Family; PSS-Fr, Perceived Social Support from Friends; PWI-SC, The Personal Well-being Index-School Children; RL, Yuuyaraqegtaar: Reasons for Life; RP, Umyuangcaryaraq: Reflective Processes; RS-14−14-item Resilience Scale; RYDM, Resilient Youth Development Module; SS, Strong Souls; SDQ, Self-Description Questionnaire; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

References

1. Zimmerman MA, Stoddard SA, Eisman AB, Caldwell CH, Aiyer SM, Miller A. Adolescent resilience: promotive factors that inform prevention. Child Dev Perspec. (2013) 7:215–20. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12042

2. McCalman J, Bainbridge R, Russo S, Rutherford K, Tsey K, Wenitong M, et al. Psycho-social resilience, vulnerability and suicide prevention: impact evaluation of a mentoring approach to modify suicide risk for remote Indigenous Australian students at boarding school. BMC Public Health. (2016) 16:98. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2762-1

3. Bodkin-Andrews G, O'Rourke V, Craven RG. The utility of general self-esteem and domain-specific self-concepts: their influence on Indigenous and non-Indigenous students' educational outcomes. Aust J Educ. (2010) 54:277–306. doi: 10.1177/000494411005400305

4. Newton D, Day A, Gillies C, Fernandez E. A review of evidence-based evaluation of measures for assessing social and emotional well-being in Indigenous Australians. Aust Psychol. (2015) 50:40–50. doi: 10.1111/ap.12064

5. Aburn G, Gott M, Hoare K. What is resilience? An integrative review of the empirical literature. J Adv Nursing. (2016) 72:980–1000. doi: 10.1111/jan.12888

6. Ungar M, Brown M, Liebenberg L, Othman R, Kwong WM, Armstrong M, et al. Unique pathways to resilience across cultures. Adolescence. (2007) 42:287–310. Available online at: https://search-proquest-com.elibrary.jcu.edu.au/docview/195945008?accountid=16285

7. Ungar M, Russell P, Connelly G. School-based interventions to enhance the resilience of students. J Educ Dev Psychol. (2014) 4:66–83. doi: 10.5539/jedp.v4n1p66

8. Windle G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev Clin Gerontol. (2011) 21:152–69. doi: 10.1017/S0959259810000420

9. Khanlou N, Wray R. A whole community approach toward child and youth resilience promotion: a review of resilience literature. Int J Mental Health Addiction. (2014) 12:64–79. doi: 10.1007/s11469-013-9470-1

10. Bainbridge R. Becoming empowered: a grounded theory study of Aboriginal women's agency. Aust Psychiatry. (2011) 19:S26–9. doi: 10.3109/10398562.2011.583040

11. Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health. (2005) 26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357

12. Olsson CA, Bond L, Burns JM, Vella-Brodrick DA, Sawyer SM. Adolescent resilience: a concept analysis. J Adolescence. (2003) 26:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00118-5

13. Neblett EW, Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor AJ. The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Dev Perspect. (2012) 6:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x

14. Newman T. Promoting Resilience: A Review of Effective Strategies for Child Care Services. Exeter: Centre for Evidence-Based Social Services, University of Exeter (2002).

15. Lutha SS, Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev Psychopathol. (2000) 12:857–85. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400004156

16. Masten AS, Coatsworth JD. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: lessons from research on successful children. Am Psychol. (1998) 53:205–20. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.53.2.205

17. Garrett MT, Parrish M, Williams C, Grayshield L, Portman TA, Rivera ET, et al. Invited commentary: fostering resilience among Native American youth through therapeutic intervention. J Youth Adolesc. (2014) 43:470–90. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0020-8

18. Hopkins KD, Zubrick SR, Taylor CL. Resilience amongst Australian Aboriginal youth: an ecological analysis of factors associated with psychosocial functioning in high and low family risk contexts. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102820

19. Henson M, Sabo S, Trujillo A, Teufel-Shone N. Identifying protective factors to promote health in American Indian and Alaska Native adolescents: a literature review. J Prim Prev. (2017) 38:5–26. doi: 10.1007/s10935-016-0455-2

20. Young C, Tong A, Nixon J, Fernando P, Kalucy D, Sherriff S, et al. Perspectives on childhood resilience among the Aboriginal community: an interview study. Aust N Z J Public Health. (2017) 41:405–10. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12681

21. Rasmus S, Allen J, Connor W, Freeman W, Skewes M. Native transformations in the Pacific Northwest: a strength-based model of protection against substance use disorder. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. (2016) 23:158–86. doi: 10.5820/aian.2303.2016.158

22. Burnette CE, Figley CR. Risk and protective factors related to the wellness of American Indian and Alaska Native youth: a systematic review. Int Public Health J. (2016) 8:137–54. Available online at: https://search-proquest-com.elibrary.jcu.edu.au/docview/1841296784?accountid=16285

23. Whiteside M, Tsey K, Cadet-James Y, McCalman J. Promoting Aboriginal Health: The Family Wellbeing Empowerment Approach. Cham: Springer (2014). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-04618-1

24. Clauss-Ehlers CS. Sociocultural factors, resilience, and coping: support for a culturally sensitive measure of resilience. J Appl Dev Psychol. (2008) 29:197–212. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.02.004

25. Mohatt NV, Fok CC, Burket R, Henry D, Allen J. Assessment of awareness of connectedness as a culturally-based protective factor for Alaska Native youth. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. (2011) 17:444–55. doi: 10.1037/a0025456

26. Haswell MR, Blignault I, Fitzpatrick S, Jackson Pulver L. The Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Indigenous Youth: Reviewing and Extending the Evidence and Examining its Implications for Policy and Practice. Sydney, NSW: Muru Marri, UNSW Australia (2013).

27. Bals M, Turi AL, Skre I, Kvernmo S. The relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms and cultural resilience factors in Indigenous Sami youth from Arctic Norway. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2011) 70:37–45. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v70i1.17790

28. DeCou CR, Skewes MC, López ED. Traditional living and cultural ways as protective factors against suicide: perceptions of Alaska Native university students. Circumpolar Health Suppl. (2013) 72:142–6. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.20968

29. Dockery AM. Culture and wellbeing: the case of Indigenous Australians. Soc Indicat Res. (2010) 99:315–32. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9582-y

30. Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2011) 9:1–18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-8

31. Parker JDA, Saklofske DH, Shaughnessy PA, Huang SHS, Wood LM, Eastabrook JM. Generalizability of the emotional intelligence construct: a cross-cultural study of North American aboriginal youth. Person Individ Differ. (2005) 39:215–27. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.01.008

32. Prout S. Indigenous wellbeing frameworks in Australia and the quest for quantification. Soc Indicat Res. (2012) 109:317–36. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9905-7

33. Kirmayer LJ, Sehdev MS, Whitley R, Dandeneau SF, Isaac C. Community resilience: models, metaphors and measures. J Aboriginal Health. (2009) 5:62–117.

34. Janca A, Lyons Z, Balaratnasingam S, Parfitt D, Davison S, Laugharne J. Here and now Aboriginal assessment: background, development and preliminary evaluation of a culturally appropriate screening tool. Aust Psychiatry. (2015) 23:287–92. doi: 10.1177/1039856215584514

35. Dingwall KM, Cairney S. Psychological and cognitive assessment of Indigenous Australians. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2010) 44:20–30. doi: 10.3109/00048670903393670

36. Ahern NR, Kiehl EM, Sole ML, Byers J. A review of instruments measuring resilience. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. (2006) 29:103–125. doi: 10.1080/01460860600677643

37. Smith-Osborne A, Whitehill Bolton K. Assessing resilience: a review of measures across the life course. J Evid Based Soc Work. (2013) 10:111–26. doi: 10.1080/15433714.2011.597305

38. Liebenberg L, Ungar M, LeBlanc JC. The CYRM-12: a brief measure of resilience. Can J Public Health. (2013) 104:e131–5.

39. Ungar M, Liebenberg L. Assessing resilience across cultures using mixed methods: construction of the child and youth resilience measure. J Mixed Methods Res. (2011) 5:126–49. doi: 10.1177/1558689811400607

40. McCalman J, Bainbridge RG, Redman-MacLaren ML, Russo S, Tsey K, Ungar MT, et al. The development of a Survey instrument to assess Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students' resilience and risk for self-harm. Front Educ. (2017) 2:1–13. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00019

41. Meyer WH. Indigenous rights, global governance, and state sovereignty. Hum Rights Rev. (2012) 13:327–47. doi: 10.1007/s12142-012-0225-3

42. Masten AS. Resilience in developing systems: progress and promise as the 4th wave rises. Dev Psychopathol. (2007) 19:921–30. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000442

43. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Br Med J. (2009) 339:332–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

44. Tomyn AJ, Norrish JM, Cummins RA. The subjective wellbeing of Indigenous Australian adolescents: validating the personal wellbeing index-school children. Soc Indicat Res. (2013) 110:1013–31. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9970-y

45. Snowshoe A, Crooks CV, Tremblay PF, Craig WM, Hinson RE. Development of a cultural connectedness scale for First Nations youth. Psychol Assess. (2015) 27:249–59. doi: 10.1037/a0037867

46. Williamson A, McElduff P, Dadds M, D' Este C, Redman S, Raphael B, et al. The construct validity of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire for Aboriginal children living in urban New South Wales, Australia. Aust Psychol. (2014) 49:163–70. doi: 10.1111/ap.12045

47. Thomas A, Cairney S, Gunthorpe W, Paradies Y, Sayers S. Strong souls: development and validation of a culturally appropriate tool for assessment of social and emotional well-being in Indigenous youth. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2010) 44:40–8. doi: 10.3109/00048670903393589

48. Stumblingbear-Riddle G, Romans JS. Resilience among urban American Indian adolescents: exploration into the role of culture, self-esteem, subjective well-being, and social support. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. (2012) 19:1–19. doi: 10.5820/aian.1902.2012.1

49. Blignault I, Haswell M, Jackson Pulver L. The value of partnerships: lessons from a multi-site evaluation of a national social and emotional wellbeing program for Indigenous youth. Aust N Z J Public Health. (2016) 40:S53–8. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12403

50. DeJong JA, Hektner JM. L3 therapuetic model site. Am Indian Alska Native Ment Health Res. (2006) 13:79–122. doi: 10.5820/aian.1302.2006.79

51. Hall PS, DeJong JA. Level 1 therapuetic model site. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. (2006) 13:17–51. doi: 10.5820/aian.1302.2006.17

52. Spears B, Sanchez D, Bishop J, Rogers S, DeJong JA. Level 2 therapeutic model site. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. (2006) 13:52–78. doi: 10.5820/aian.1302.2006.52

53. Lowe J, Liang H, Riggs C, Henson J, Elder T. Community partnership to affect substance abuse among Native American adolescents. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2012) 38:450–5. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.694534

54. Ritchie SD, Wabano MJ, Russell K, Enosse L, Young NL. Promoting resilience and wellbeing through an outdoor intervention designed for Aboriginal adolescents. Rural and Remote Health. (2014) 14:1–19.

55. Mohatt GV, Fok CC, Henry D, People Awakening Team, Allen J. Feasibility of a community intervention for the prevention of suicide and alcohol abuse with Yup'ik Alaska Native youth: The Elluam Tungiinun and Yupiucimta Asvairtuumallerkaa studies. Am J Commun Psychol. (2014) 54:180–6. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9646-2

56. Dobia B, Bodkin-Andrews G, Parada RH, O'Rourke V, Gilbert S, Daley A, et al. Aboriginal Girls Circle: Enhancing Connectedness and Promoting Resilience for Aboriginal Girls: Final Pilot Report. Sydney, NSW: University of Western Sydney (2014).

57. Wagnild GM, Young HM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J Nurs Meas. (1993) 1:165–78.

58. Winterowd C, Montgomery D, Stumblingbear G, Harless D, Hicks K. Development of the American Indian Enculturation scale to assist counseling practice. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. (2008) 15:1. doi: 10.5820/aian.1502.2008.1

59. Bar-On R, Parker J. EQ-i: YV. Baron Emotional Quotient Inventory: Youth Version. Technical Manual. In: Parker JDA, editors. The Handbook of Emotional Intelligence. New York, NY: MHS (2000). p. 343–62.

60. Austin G, Duerr M. Guidebook for the California Healthy Kids Survey. San Francisco, CA: WestEd. (2004).

61. Fok CC, Allen J, Henry D, Mohatt GV, People Awakening Team. Multicultural mastery scale for youth: multidimensional assessment of culturally mediated coping strategies. Psychol Assess. (2012) 24:313–27. doi: 10.1037/a0025505

62. Fok CC, Allen J, Henry D, People Awakening Team. The brief family relationship scale: a brief measure of the relationship dimension infamily functioning. Assessment. (2014) 21:67–72. doi: 10.1177/1073191111425856

63. Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D, Oishi S, et al. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indicators Res. (2010) 97:143–56. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

64. Haswell MR, Kavanagh D, Tsey K, Reilly L, Cadet-James Y, Laliberte A, et al. Psychometric validation of the Growth and Empowerment Measure (GEM) applied with Indigenous Australians. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2010) 44:791–9. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.482919

65. Allen J, Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM, Hazel KL, Thomas L, Lindley S. The tools to understand: community as co-researcher on culture-specific protective factors for Alaska Natives. J Prevent Interven Commun. (2006) 32:41–59. doi: 10.1300/J005v32n01_04

66. Beauvais F. The need for community consensus as a condition of policy implementation in the reduction of alcohol abuse on Indian reservations. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. (1992) 4:77–81. doi: 10.5820/aian.0403.1990.77

67. Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Adolescent drug use: findings of national and local surveys. J Consult Clin Psychol. (1990) 58:385. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.58.4.385

68. Karcher M. The Hemingway—Measure of Adolescent Connectedness: A Manual for Interpretation and Scoring. San Antonio, TX: University of Texas. (2012).

69. Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: three validation studies. Am J Commun Psychol. (1983) 11:1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416

70. Marsh HW, Ellis LA, Parada RH, Richards G, Heubeck BG. A short version of the self description questionnaire II: operationalizing criteria for short-form evaluation with new applications of confirmatory factor analyses. Psychol Assess. (2005) 17:81–102. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.1.81

71. Williamson A, Redman S, Dadds M, Daniels J, D'Este C, Raphael B, et al. Acceptability of an emotional and behavioural screening tool for children in Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services in urban NSW. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2010) 44:894–900. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.489505

72. Cummins RA, Lau ALD. Personal Wellbeing Index – School Children (PWI-SC) (English). Melbourne, VIC: Deakin University (2005).

73. Allen J, Fok CC, Henry D, Skewes M, People Awakening Team. Umyuangcaryaraq “Reflecting”: multidimensional assessment of reflective processes on the consequences of alcohol use among rural Yup'ik Alaska Native Youth. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2012) 38:468–75. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.702169

74. Abimbola S, Negin J, Jan S, Martiniuk A. Towards people-centred health systems: a multi-level framework for analysing primary health care governance in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. (2014) 29 (Suppl. 2):ii29–39. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu069

75. Wexler L. Looking across three generations of Alaska Natives to explore how culture fosters indigenous resilience. Transcultu Psychiatry. (2014) 51:73–92. doi: 10.1177/1363461513497417

76. Oré CE, Teufel-Shone NI, Chico-Jarillo TM. American Indian and Alaska Native resilience along the life course and across generations: a literature review. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. (2016) 23:134–57. doi: 10.5820/aian.2303.2016.134

77. Fleming J, Ledogar RJ. Resilience and indigenous spirituality: a literature review. Pimatisiwin. (2008) 6:47–64.

78. Sheng Y, Sheng Z. Is coefficient alpha robust to non-normal data? Front Psychol. (2012) 3:34. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00034

79. McNeish D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we'll take it from here. Psychol Methods. (2017) 23:412–33. doi: 10.1037/met0000144

80. Brouzos A, Misailidi P, Hadjimattheou A. Associations between emotional intelligence, socio-emotional adjustment, and academic achievement in ahildhood: the influence of age. Can J Schl Psychol. (2014) 29:83–99. doi: 10.1177/0829573514521976

81. Goodman R, Iervolino AC, Collishaw S, Pickles A, Maughan B. Seemingly minor changes to a questionnaire can make a big difference to mean scores: a cautionary tale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2007) 42:322–7. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0169-0

82. Haswell-Elkins M, Sebasio T, Hunter E, Mar M. Challenges of measuring the mental health of Indigenous Australians: Honouring ethical expectations and driving greater accuracy. Aust Psychiatry. (2007) 15(Suppl.1):S29–33. doi: 10.1080/10398560701701155

83. Wexler LM, Gone JP. Culturally responsive suicide prevention in indigenous communities: Unexamined assumptions and new possibilities. Am J Public Health. (2012) 102:800–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300432

Keywords: resilience, indigenous, adolescents, measurement instruments, socioecological resilience, cultural resilience

Citation: Jongen C, Langham E, Bainbridge R and McCalman J (2019) Instruments for Measuring the Resilience of Indigenous Adolescents: An Exploratory Review. Front. Public Health 7:194. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00194

Received: 24 April 2018; Accepted: 01 July 2019;

Published: 16 July 2019.

Edited by:

Daniel Vujcich, School of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Marisa Theresa Gilles, Western Australian Center for Rural Health (WACRH), AustraliaSarah Derrett, University of Otago, New Zealand

Copyright © 2019 Jongen, Langham, Bainbridge and McCalman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Crystal Jongen, Y3J5c3RhbC5za3kuam9uZ2VuQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Crystal Jongen

Crystal Jongen Erika Langham

Erika Langham Roxanne Bainbridge

Roxanne Bainbridge Janya McCalman

Janya McCalman