95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 09 April 2019

Sec. Children and Health

Volume 7 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00075

Stefanos Stylianos Plexousakis*

Stefanos Stylianos Plexousakis* Elias Kourkoutas

Elias Kourkoutas Theodoros Giovazolias

Theodoros Giovazolias Kalliopi Chatira

Kalliopi Chatira Dimitrios Nikolopoulos

Dimitrios NikolopoulosMuch research on school bullying and victimization have outlined several individual, family, and school parameters that function as risk factors for developing further psychosocial and psychopathological problems. Bullying and victimization are interrelated with symptoms of psychological trauma, as well as emotional/ behavioural reactions, which can destabilize psychosocial and scholastic pathways for children and adolescents. The current study explored the various dimensions of psychological trauma (depressive symptoms, somatization, dissociation, avoidance behaviours) associated with school bullying/victimization in relation to parental bonding among 433 students (8–16 years old) from representative large cities in Greece. The following scales were employed: (a) Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire, (b) Child Report of Post-traumatic Symptoms (CROPS), and (c) Parental Bonding Inventory instrument (PBI). Pathways analysis extracted a series of models which showed that maternal and paternal overprotection (anxious-controlling/aggressive) had positive association with post-traumatic stress symptoms. Specifically, the quality of parental bonding was related with children's bullying/victimization experiences and post-traumatic symptomology. Conversely, results indicated that maternal and paternal care can reduce the manifestation of post-traumatic stress symptoms. Implications for interventions are discussed.

Bullying is a significant social stressor for children and adolescents and has an estimated prevalence depending on the definition of bullying and the sample used. Peer maltreatment is estimated to be between 20 and 45%; bullying that occurs once a week or more can be as high as 32% (1–7). Bullying is defined as a long-lasting and systemic form of interpersonal aggression from an individual (perpetrator), where the victims are persistently exposed to negative or violent actions from other student/s over a period and struggles to defend themselves against these actions (8).

Bullying behaviours emerge as a consequence of repeated exposure to aggression in the form of verbal hostility, teasing, physical violence, or social exclusion (7). As a subtype of aggressive behaviour, bullying involves an imbalance of power between perpetrators and victims, where one side (perpetrator) demonstrates negative actions, and the other (victim) is not able to defend her-/himself (9–12). Many researchers have emphasized the group aspect of bullying not only as a dyadic problem between a bully and a victim which is rather recognized as a group phenomenon including bystanders (13, 14).

Exposure to bullying is a significant risk factor that contributes independently to the emergence of psychological difficulties and pathology, regardless of pre-existing mental health symptomology, genetic predisposition, or family psychosocial difficulties (15). Many studies have found that bullying is the root of severe negative psychological and physical consequences, including depression, anxiety, reduced self-esteem, decreased school attendance and avoidance symptoms, somatization, as well as suicide ideation/attempts/completions (3, 4, 10, 11, 16–18). Some researchers claim that school bullying can cause symptoms such as those experienced by survivors of child maltreatment and abuse (19). Bullying prevalence in Greece has the same varying statistics as schools in other European countries. Owing to increasing prevalence of bullying incidents in Greece, with consequent emotional difficulties to many students, there is an emerging necessity to carry out research exploring the deleterious effects (including trauma symptoms) both to victims and bullies (20). In fact, this is the first proposed study in Greece, with a randomly selected sample, to examine post-traumatic stress symptomology resulting from bullying and victimization in relation to parental bonding.

Much research has revealed that various individual, family, and school parameters function as risk factors for developing further psychosocial and psychopathological difficulties. Symptoms of psychological trauma, as well as emotional/ behavioural reactions, can destabilize children's psychosocial and scholastic pathways. Previous studies have emphasised the catalytic role of dysfunctional families, and more specifically the negative impact of hostile and aggressive parental overprotection, on children's involvement in bullying incidents, both as victims or perpetrators. On the other hand, maternal and/or paternal care is also a significant protective factor against the manifestation of children's internalizing or externalizing disorders (21, 22). Thus, the present study examined whether bullying experiences, as a victim or perpetrator, is associated with post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSD, DSM-V). More importantly, we addressed whether parental bonding quality (care, indifference, overprotection, encouragement of autonomy) influences the relationship between bullying roles and traumatic symptoms.

Extensive research has revealed that bullying experiences are associated with emotional difficulties, including feelings of loneliness, anxiety, depression, adjustment difficulties, low academic performance, low self-esteem (4, 23–33) and a lack of appropriate social skills. More recent studies have shown that bullying is also associated with symptoms of psychological dissociation (34–36), somatization (37–39), avoidance behaviours (40–46), and symptoms of PTSD (47–50).

Although the initial introduction of PTSD in the DSM was not primarily designed with children and adolescents in mind, a developmental perspective has gradually been introduced in newer DSM versions (51). The evolution of diagnostic criteria has indicated that PTSD in childhood and adolescence is almost identical with criteria applied to adults (i.e., trauma re-enactment, horrible dreams, “shrinked” hope for the future, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma event, lack of interest, and somatization of stress and anxiety; (52). Bullying can potentially hamper bio-psycho-social growth; therefore, it is necessary to apply a developmental perspective to increase our understanding as to how a PTSD diagnosis can be applied, as well as examine how we can reduce emerging traumatic effects (53). Bullying is an interpersonal event that occurs at a salient relational level; from this perspective, there are several aspects of children's and adolescents' lives that could be affected in a deleterious way as a result of PTSD experiences. Such experiences occur at a very critical time, when the brain is developing bio-psycho-social systems that regulate emotions, dramatically influencing behaviour (54). In recent years, some studies have examined the degree to which school bullying is related to the presence of PTSD symptomology (55). For instance, Mynard et al. (30) revealed that 37% of bullying victims reported significant PTSD symptoms. Additionally, River (56) revealed that 25% of participants appeared to experience PTSD symptoms, particularly intrusive memories of bullying instances, even after leaving school. McKenny et al. (57) also found a significant association between being bullied and PTSD symptoms among school-aged children. Furthermore, several studies observed that bullies, who may also be victims themselves, experience higher levels of suicidal ideation and potential PTSD symptomology (4, 5, 58).

Herman [1992, (59)], as well as Terr (60), claimed that an individual who has been repeatedly bullied, experiences a situation of helplessness, similar to a victim of trauma; therefore, they suggested that bullying dynamics could be considered a form of repeated trauma. Olweus (8) emphasized that three distinct criteria characterize bullying into an experience of chronic trauma. Primarily, there is an intention to harm the victim, which is directly experienced by a victim or indirectly by a bystander. Bullying can be direct or indirect and cause both physical and psychological damage. Secondly, the repetitive nature of bullying is similar to Terr's (60) trauma of a second type, as well as Herman's complex PTSD (59). The accumulative effect of exposure to bullying undermines a victim's sense of self and can cause short-term and long-term consequences. Finally, bullying involves an imbalance of power between the perpetrator and victim, which can lead a victim into a sense of helplessness and weakness, critical characteristics in all forms of trauma (61). Several studies provide evidence of a strong association between bullying and PTSD symptoms, emphasizing that bullying could potentially be a form of continuous trauma rather than a mere acute stress experience (62, 63).

Previous studies have emphasized the impact of dysfunctional family relationships with both parents, which are linked with a child's involvement with bullying behaviours (64, 88). It is now clear that both bullies and victims experience inadequate support from parents. There are also significant findings indicating the existence of domestic violence and other adversities within the lives of bullies and victims (65). Many bullies appear to experience authoritarian parental styles and conflicts (66). Authoritarian style parental bonding is strongly associated with higher levels of bullying, while passive style parental bonding and pedagogy are linked with victimization (67). More recent findings indicate that among parents who practice hostile control, children exhibit a higher potential for engaging in bullying behaviours (22, 68). Children who experience insecure and avoidant parental bonding are likely to demonstrate callous-unemotional characteristics (69, 70). Parents who lack care and emotional warmness can rear children who exhibit a lack of empathy, which can lead to bullying proneness (20). Recent studies have also shown that bullying perpetrators experience low levels of parental care and higher levels of overprotection (71). Parents who are supportive and demonstrate a caring style reduce the possibility of their children engaging in bullying behaviours (72). Other studies have emphasized the significance of a father's protective role as a defence against peer bullying (21). A father's involvement is an even more important factor when a mother's involvement is low (21).

Until recently, very few studies have investigated the relationship between bullying and traumatic symptoms, while accounting for the role of parental bonding. This is quite striking given that many children and adolescents are frequently exposed to bullying behaviours that result in serious emotional symptoms that can destabilize their academic, emotional, and social progress. Therefore, we reviewed previous literature in order to investigate aspects of post-traumatic symptoms related to bullying behaviours among school-aged children. There has been a call for more studies clarifying the effect of bullying on the manifestation of post-traumatic stress symptoms and how parental bonding affects this relationship (30, 55–57) within a representative sample of Greek students. Based on previous studies (51), we expected that as many as 20–30% of students would report a bullying experience, but fewer would report frequent bullying. Although previous studies have revealed that more boys than girls are involved in bullying, this appears to have changed as different indirect forms of bullying are emerging (2, 41). The core question of our study was to clarify the degree to which bullying behaviours are associated with symptoms of PTSD. Regarding gender, previous studies have revealed that girls are more vulnerable to manifesting post-traumatic stress symptoms (73, 74); therefore, we expected to find higher post-traumatic symptom scores among girls than boys (4, 5).

We explored the various aspects/dimensions of psychological trauma symptoms in relation to school bullying/victimization along with parental bonding quality (care, indifference, overprotection, and encouragement of autonomy) among 433 students (8–17 years old) from all over Greece. Specifically, we examined how traumatic symptom levels (depression, somatization, avoidance behaviour, dissociation) are associated with parental bonding type, in the context of bullying type, and how bullying behaviour roles are shaped (75). Here, we discussed and analysed a specific model that emphasises how certain types of parental bonding can cause certain emotional reactions in relation to bullying and traumatic symptoms. One basic assumption is that there is a negative role of parental overprotection (anxious or controlling/aggressive) and emotional reactions/risk for victimization that emerges for students in the present sample.

We used a randomly selected sample taken from a survey conducted in Greece during 2013–2014. We selected a sample from schools from the largest urban areas of Greece, including Athens (65.6%, n = 284), Thessaloniki (21.0%, n = 91), and Crete (13.4%, n = 58). A total of 433 students aged 8–17 years participated in our study. Sample size was estimated apriori using G*Power version 3.1 (76). The analysis indicates that a sample size of 311 would be sufficient to detect significant direct and indirect associations with a power of 0.80 and an alpha of 0.05 (The total population was 516.034 students).

Boys comprised 45.5% (n = 197) of our sample, while girls comprised 54.5% (n = 236). The age distribution of our sample was as follows: 10 years (8.1%, n = 35), 11 years (18.9%, n = 82), 12years (21.0%, n = 91), 13 years (20.1%, n = 87), 14 years (20.6%, n = 89), 15 years (10.6%, n = 46), 16 years (0.5%, n = 2), and 17 years (0.2%, n = 1). The class distribution was as follows: Primary School: 5th Grade (24%, n = 104), 6th Grade (20.1%, n = 87); High school: 1st Class (22.4%, n = 97), 2nd Class (21.7%, n = 94), 3rd Class (11.8%, n = 51).

Consent to carry out the study was initially obtained from the Ministry of Education (both for primary and secondary education departments). Later, we sought permission from local school authorities and finally from each school's directors. Written informed consent was sought from parents to allow their children to participate. We sent a sealed letter to each parent (through their children) with a written description regarding the nature and goals of our study and invited parents to provide written consent. Following guidelines from the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy Code of Ethics (77), children who did not obtain written permission from parents were excluded from participating. We asked the class teacher to ensure children that all responses would be confidential, so that children could feel secure and confident about participating. We clearly told the children that no individual from the school or their parents would see their answers; this was to ensure each student's psychological integrity and obtain answers provided with a sense of safety and security. Our survey met all ethical standards and criteria of the Greek Educational Department from the Ministry of Education, as well as the Ethical Research Committee at the University of Crete. Due to the sensitive nature of our study concerning trauma symptoms and bullying, we used methods that respected children and ensured their health and safety. We stated clearly the goals of our study, we only included children who obtained permission from their parents and the school director, the language and research instruments were child-friendly, and we stated clearly that no child was obliged to participate without his/her individual permission (77).

Bullying was measured using the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (78, 79). The students were first provided a written definition/explanation of bullying behaviours so as to assist with comprehending the phenomenon. The scale comprised 40 questions, which sought information regarding the following areas: Prevalence of bullying, duration of the bullying event, type of bullying, identification of bullying roles, general psychosocial adjustment, internalizing, or externalizing symptoms, self-evaluation, depressive tendencies, general aggressiveness, antisocial behaviours, general bullying attitudes, and evaluation of awareness regarding teachers and parents. (7, 78, 79). Our sample completed the Greek version of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (78, 80, 81). Cronbach alphas ranged between 0.83 and 0.87 for victimization across groups and time measures and between 0.65 and 0.88 for bullying (81).

Symptoms of trauma were measured using the Children's Report of Post-traumatic Symptoms (CROPS) (109). CROPS is a self-report scale comprising 25 questions examining a child's post-traumatic stress symptoms from having been involved in a stressful incident. Answers were provided on an analogue scale ranging from 0 to 2 (three-point Likert scale, where 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, and 2 = very often). A total score was estimated by adding all answers together, where higher scores meant the existence of clinically significant PTSD symptomology (82). The following main traumatic symptoms were examined: 1. depression/anxiety (Questions: 4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25) 2. psychic-dissociation (Questions: 1,2,3,17,18) 3. somatisation (Questions: 12, 13, 14,15), 4. avoidance behaviours (Questions: 5, 6, 8, 24). As for CROPS we also used the Greek Version (67). The CROPS has internal consistency with an alpha value of 0.91. Its 4–6 week test–retest correlation is 0.80 (83, 84).

Parental bonding was measured using the Parental Bonding Inventory Scale (PBI) (75, 85). The scale consists of two questionnaires: (a) Father's Parental Bonding and (b) Mother's Parental Bonding. Both questionnaires comprise 25 questions, and each explore the following factors: 1. care (Questions: 1, 5, 6, 11, 12, 17), 2. over-protection (Questions: 8, 9, 10, 13, 19, 20, 23), 3. indifference (Questions: 2, 4, 14, 16, 18, 24), 4. encouragement of autonomy (Questions: 3, 7, 15, 21, 22, 25).

Data were analysed using the SPSS/V21 statistical program (86, 87) for Windows. Statistical methods included frequency and percentage analyses, means comparisons, hypothesis testing, parametrical tests, t-tests for independent samples, ANOVAs, regression analyses, path analyses, and confirmatory factor analyses.

Confirmatory analyses revealed that the identified factors fit the data well. Path analyses generated a series of models (see Figures 1–3) with the following parameters: (a) four dimensions of parental bonding (care, indifference, overprotection, encouragement of autonomy) (b) four types of traumatic symptoms (depression-anxiety, dissociation, avoidance, somatization), and (c) two forms of bullying (bully, victim).

Our data fit all necessary conditions for best-fit models. The aforementioned results agree with the assumptions of a confirmatory factor analysis. We can assume that the PBI and CROPS factors in our data are consistent with those mentioned in previous studies and similar theories. The thresholds listed in the tables are taken from Hu and Bentler (88).

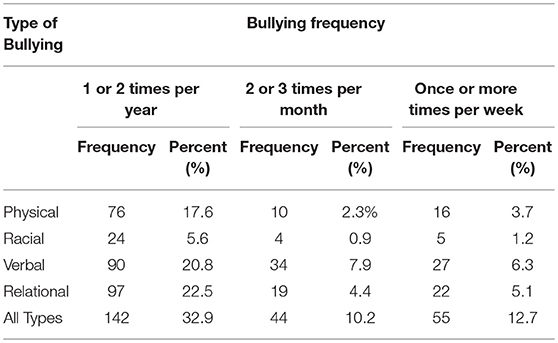

Our results revealed that 102 students (23.5%) experienced bullying (as victims) at least once during the last year. A total of 14 students (3.2%) reported high frequency bullying (one to several times per week) as seen in Table 1. A total of 6 students (1.4%) reported that they had experienced physical bullying, or one of the more prevalent forms of bullying, many times every week, while 38 students (8.8%) reported that they had experienced bullying only once or twice every week. As expected, verbal bullying, as well as relational bullying, was the most prevalent form of bullying. More specifically, 27 students (6.3%) reported that they had experienced verbal bullying one or more times every week, while 52 students (12%) had experienced relational bullying. Racial bullying was reported by 24 students (5.5%). Several students (n = 68, 15.7%) reported being bullied by classmates (Table 2). Regarding gender, victims reported that perpetrators were mainly boys (45 students, 10.4%), but there was a significant number of girl perpetrators reported (n = 12, 2.8%) (Table 3). Our findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that perpetrators are, to a large degree, boys. Bullying occurred mainly at the individual level rather than at the group level. At the group level, 31 students (7.2%) reported being bullied by boys, while 15 students (3.5%) reported being bullied by girls. However, 18 students (4.2%) reported being bullied by both boys and girls. It is very important to mention that a significant number of students (n = 26, 6%) did not react (e.g., telling perpetrators to stop or asking for help from peers or an adult); therefore, these victims manifested intense emotional reactions (e.g., crying). A significant number of students were not able to report bullying behaviours to an adult in order to protect themselves; specifically, 28 students (6.5%) did not tell anyone.

Table 1. Students from survey's sample who were bullying victims by type of bullying and frequency of the event.

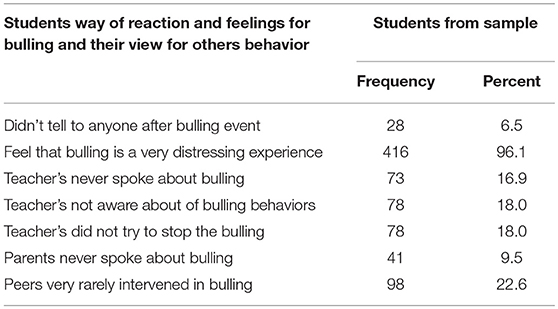

It is important to highlight that several students (n = 73, 16.9%) reported that teachers never spoke to them about bullying in school (Table 4). Additionally, 41 students (9.5%) reported that parents did not speak to them about bullying. Regarding where at school bullying occurred, 50 students (11.6%) reported being bullied while coming to, or leaving from, school. It is quite interesting to note students' perceptions about teachers' awareness. For instance, 78 students (18.0%) stated that teachers were not aware of bullying behaviours, and 35 students (8.1%) felt that teachers did not try to stop the bullying. Regarding the role of bystanders, many students (n = 98, 22.6%) reported that their peers very rarely intervened, even though most students (96.1%) feel that bullying is a very distressing experience. Regarding bystanders' reactions, while many students (n = 172, 39.7%) reported the incident to an adult, it is quite interesting that several students (n = 142, 32.8 %) tried to have no relationship with the event, while some students participated or watched with pleasure (n = 17, 3.9%).

Table 4. Students from survey's sample by way of reaction and feelings for bullying and their view for others behavior.

Our t-test analyses revealed that the average values for boys as victims were higher than girl's for different types of bullying (physical, verbal, relational, racial). For the general victim's scale, the difference between boys and girls was statistically significant (with boys having a higher average).

Using a psychometric instrument (CROPS) for the identification of post-traumatic stress symptoms, we observed that 100 students (23.1%) (Table 5) reported that they “daydream during the day”, indicating the existence of emotional difficulties related to internalized problems of anxiety, depression, and psychic dissociation, which are the most serious manifestations of trauma reactions (83). Additionally, 155 students (35.8%) reported that sometimes “I lose track of myself when people talk to me”. Several students (144; 33.3%) reported serious difficulties with their ability to concentrate, which is indicative of internalized difficulties due to anxiety or depression. Additionally, 112 students (25.9%) reported feeling sad and melancholic.

It is noteworthy that 200 students (46.2%) reported that “sometimes, I think about the awful things that have happened to me,” indicating the existence of traumatic stress by reliving the traumatic event. Another important finding was that 173 students (40%) reported that “sometimes I try to forget about the awful things that have happened to me,” reflecting the traumatic symptom of avoidance. A total of 165 students (38.1%) reported that “I am concerned that awful things could happen to me,” indicating a struggle with anxiety. Anxiety was also identified by 92 students (21.2%) who reported sleep difficulties. Another 141 students (32.6%) reported sleep disturbances with nightmares. It is notable that 165 students (38.1%) reported the existence of headaches; 112 students (25.9 %) reported having stomach aches; and 88 students (20.3%) reported sometimes feeling sick. These three somatic symptoms are part of the axis of somatization for PTSD (52). A total of 185 students (42.7%) reported feeling tired and lacking in energy, and 72 students (16.6%) reported feeling completely alone, further indicative of depression symptomology. Additionally, 92 students (21.2%) reported feeling “strange and differently than other children,” and 101 students (23.3%) reported feeling that “something is wrong with me,” reflective of possible anxiety or depression symptoms. A total of 171 students (39.5%) reported feeling that “it is my fault when awful things happen to me,” while 78 students (18.0%) reported “feeling bad-luck” in their life. Additionally, 125 students (28.9%) felt that they were not of great importance. These responses are indicative of possible low self-esteem and a generally bleak future, which are all characteristic of PTSD. It is also interesting that 241 students (55.7%) reported that several things triggered annoyance and anger, possibly reflecting externalizing difficulties with anger management. Finally, 182 students (42%) reported being vigilant to awful things that could occur, suggesting another key post-traumatic stress symptom (52).

While average symptom scores were higher among girls when compared with boys, only avoidance behaviour scores were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Figure 1 revealed that having an overprotective mother was positively associated with the emergence of traumatic symptoms (r.f. = 0.02, p < 0.001); however, an ideal level of maternal care reduced the likelihood of a child being a bully (r.f. = −0,14, p < 0.001). Having also an overprotective mother was related with a child being a victim (r.f. = 0.17, p < 0.001). Additionally, being a child victim was strongly associated with the emergence of traumatic symptoms (r.f. = 0.05, p < 0.001) and with the possibility of being a bully (r.f. = 0.25, p < 0.001). We also observed that a mother's facilitation of autonomy reduced the likelihood of a child being a bully (r.f. = −0,08, p < 0.05). In terms of bullying roles and depression, the following were observed. First, a child who experienced an overprotective mother was more likely to be victim (r.f. = 0.017, p < 0.001). Several of these children exhibited symptoms of depression (indirect effect) (r.f. = 0.05, p < 0.001), while another segment also reported being a bully (r.f. = 0.025, p < 0.001). These results suggest that a mother's overprotective tendencies and traumatic experiences as a victim are plausible risk factors for the exhibition of depressive symptoms (internalizing symptoms) and/or aggressive bullying (externalizing symptoms). Furthermore, results suggested that a lack of maternal care was increasing the likelihood of a child being a victim (r.f. = −0.014, p < 0.001).

Bullying roles in relation to psychic dissociation produced the following observations. There was a significant positive association between mother's overprotection and child victimization (indirect effect) (r.f. = 0.017, p < 0.001). Greater maternal overprotection increased the likelihood of a child being a victim. Being a child victim was also strongly related with the possibility of being a perpetrator (indirect effect) (r.f. = 0.025, p < 0.001). A lack of maternal care was also related with a child taking on a perpetrator role (r.f. = −0.014, p < 0.001), with a caring mother making it less likely that a child would be a bully. Being a victim was also linked to the manifestation of psychological dissociation (r.f. = 0.05, p < 0.001). Also, a lack of maternal encouragement of a child's autonomy was associated with a child being a perpetrator (r.f. = −0.08, p < 0.05), with the converse being true if a mother encouraged autonomy. Maternal overprotection was also related with a child experiencing psychological dissociation.

Bullying roles in relation to somatization produced the following results. First, there was a significant positive association between maternal overprotection and child victimization, and being a victim was strongly related with being a perpetrator (indirect effect) (r.f. = 0.025, p < 0.001). Conversely, maternal care reduced likelihood of a child being a perpetrator (r.f. = −0.014, p < 0.001), establishing maternal care as a major protective factor. Being a victim had positive association with reported somatization (indirect effect) (r.f. = 0.06, p < 0.001). Maternal encouragement of a child's autonomy was also related to a decreased likelihood of a child being a perpetrator (r.f. = −0,08, P < 0,05), while maternal overprotection was significantly associated with a child's somatization (r.f. = 0.02, p < 0.05).

Assessing bullying roles in relation to avoidance behaviour led to the following observations. Maternal overprotection had positive association with child victimization (indirect effect) (r.f. = 0.017, p < 0.001), and being a victim had strong relation with a child being a perpetrator (r.f. = 0.025, p < 0.001). Increased maternal care was related to a decreased likelihood of a child being a perpetrator (r.f. = −0.014, p < 0.001). Being a victim had also positive association with avoidance behaviours (r.f. = 0.04, p < 0.001). Furthermore, maternal overprotection was strongly related with a child manifesting avoidance behaviour (r.f. = 0.03, p < 0.001). Maternal facilitation of a child's autonomy was associated with a decreased likelihood of a child being a perpetrator (r.f. = −0.08, p < 0.05). Finally, maternal care was related to a decrease in a child's avoidance behaviours.

Within the somatization and avoidance behaviour path models, maternal overprotection was associated of children taking on a victim role. Furthermore, maternal overprotection directly related with the manifestation of children's traumatic symptoms. This was particularly the case for avoidance behaviours.

Figure 2 indicates that having an overprotective father is strongly associated a child being a victim (r.f. = 0.14, p < 0.001). Conversely, paternal care had negative relation with being a victim (r.f. = −0.17, p < 0.001). Being a child victim was also positively associated with a child being a bully (r.f. = 0.25, p < 0.001). Furthermore, being a child victim had strong relation with reported trauma symptoms (r.f. = 0.05, p < 0.001). Having an overprotective father was additionally related with reported trauma symptoms (r.f. = 0.02, p < 0.001). A father's indifference had negative association with reported trauma symptoms (r.f. = −0.01, p < 0.05). For the path analysis regarding bullying roles and depression, the following was observed. First, a lack of paternal care was related with a high likelihood of a child being a victim (r.f. = −0.17, p < 0.001), the child reporting depression symptoms (r.f. = 0.05, p < 0.001), and the child being a perpetrator (r.f. = 0.014, p < 0.001). As compared to the maternal path analysis, a paternal lack of care had positive association with a child being a perpetrator. Second, paternal overprotection increased the probability of a child being a victim (r.f. = 0.05, p < 0.001) and subsequently experiencing depression symptoms (r.f. = 0.025, p < 0.001).

In terms of bullying roles and psychological dissociation, the following were observed. Specifically, paternal overprotection was positively associated with a child being a victim (r.f. = 0.014, p < 0.001). Being a victim had strong relation with a child being a perpetrator (r.f. = 0.025, p < 0.001). On the contrary, paternal care had negative association with being a child victim (r.f. = −0.017, p < 0.001). Furthermore, being a victim was positively related with reported psychological dissociation (indirect effect) (r.f. = 0.06, p < 0.001).

Regarding the path between bullying roles and somatization, we first observed a significant positive association between paternal overprotection and child victimization (r.f. = 0.014, p < 0.001). Child victimization was also strongly related with perpetration (r.f. = 0.025, p < 0.001). Paternal care was a protective factor against victimization (r.f. = −0.017, p < 0.001). Victimization, in turn, was related with reported somatization (indirect effect) (r.f. = 0.06, p < 0.001). Hence, paternal overprotection increases the probability that a child would become a victim and later manifest somatization and/or perpetrator behaviours. This same pathway was observed when examining a father's lack of care.

Regarding the path between bullying roles and avoidance behaviours, we observed a significant positive association between paternal overprotection and victimization (indirect effect) (r.f. = 0.014, p < 0.001). Child victimization was related with perpetration (r.f. = 0.025, p < 0.001). Conversely, paternal care was negatively associated with victimization (r.f. = −0.017, p < 0.001). Victimization was positively related with reported avoidance behaviours (r.f. = 0.04, p < 0.001). Finally, paternal overprotection was associated with avoidance behaviours (r.f. = 0.02, p < 0.001). Hence, victimization was related with avoidance behaviours through paternal overprotection, while an indirect relationship between victimization and avoidance was still significant.

As shown in Figure 3, having an overprotective father is strongly related with the report of traumatic symptoms (r.f. = 0.02, p < 0.001). Second, a child who has been a victim is more likely to report traumatic symptoms (indirect effect) (r.f. = 0.05, p < 0.001). Third, being a child victim increased the probability of being a bully (r.f. = 0.24, p < 0.001). Table 3 revealed that paternal care decreased the likelihood of a child being a victim (r.f. = −0.13, p < 0.05). Maternal overprotection had a significant association with victimization (r.f. = 0.15, p < 0.05) Paternal overprotection was related with a child expressing bullying behaviours (r.f. = 0.11, p < 0.05), while, maternal care decreased this probability (r.f. = −0.11, p < 0.05).

The most significant finding regarding mothers' role, as perceived by the child, is that mother's overprotection (see Figure 1) has strong association with a child becoming a victim, with two different pathways/outcomes; first pathway is related with the development of traumatic symptoms and the second pathway with child to become a perpetrator. We can assume that mother's overprotection consists a significant risk factor for children's vulnerabilization that may lead to traumatic symptoms or for a child to react in an aggressive way through bullying behavioral patterns (15). A plausible explanation of maternal overprotection negative association is that this type of parenting practice (in the hostile/controlling or anxious form) seen to impede children to spontaneously developing their own potential (22).

Our second significant finding is that a lack of maternal care, which indicates blunted emotional responsiveness, was related with a child becoming a perpetrator. Similarly, previous studies, showed that lack of care, which considered a form of emotional deprivation and neglect, is associated with instrumental or intentional aggressive behaviour (89, 90). Studies have revealed that parent's emotional absence, accompanied with lack of emotional responsiveness, creates a state of intense emotional frustration that can transform into negative and hostile feelings such as anger and rage, resulting to hostile behaviours and open aggressiveness (21, 22).

Similarly, regarding father's role (see Figure 2), the strongest finding is that paternal overprotection is associated without any other contributing factor with the manifestation of traumatic symptoms. The role of father, as a key socialization factor, is critical during transition in pre-adolescent or adolescent period (21, 22). We assume that fathers who seem to impede their children's primordial need for socialization through overprotection (in the aggressive or anxious controlling form) have a very strong negative impact on their children's developmental pathway, with increased risk of leading them to trauma symptoms. Additionally, father overprotective attitude is related, to a significant degree, with the bully behaviour. A plausible explanation for this finding is that some children and adolescents react in an aggressive way against these paternal practices or transform their hostile and aggressive feelings to externalized symptoms/aggressive behaviours. Another significant finding regarding father's role is that the lack of paternal care which also means lack of paternal protection and support, increases the likelihood of these children for being victimized and in turn to either develop traumatic symptoms or aggressive behaviour (bully) [see also (15)].

It is worth noticing that according to our results (see Figure 3) a father's overprotective stance has a stronger association than mother's on a child's emotional state and vulnerabilization, as it is related directly to symptoms of trauma. According to previous studies (21, 22), a plausible explanation is that father has a more critical role than mother, during preadolescence and adolescence, on children's social/emotional development and coping strategies formation. Our results show that overprotective fathering reduces their children's psychological potential, rendering them vulnerable undertaking bullying roles and exhibiting traumatic symptoms.

The PBI though, does not differentiate controlling or aggressive from anxious overprotective parenting. However, research shows that both forms of overprotective parenting are considered a form of emotional abuse in the sense that prevent children from critical socialization process and therefore from developing the appropriate interpersonal skills and coping strategies (22, 91).

Overall, the most significant finding of our research was the negative association of parental overprotection, on children's involvement to bullying and victimization, as well as to the development of trauma states, through different pathways, a finding which is consistent with other studies (22). Both overprotection (as a form of control) and lack of care (as a form of emotional neglect and lack of support) regarding social-emotional development, create high risks conditions for psychological vulnerability. When the child experiences additional forms of victimization in other contexts, such as school, she/he is likely to develop strategies to cope with intrapersonal and interpersonal anxiety and negative emotions, subsequently resulting in internalizing or externalizing symptoms (aggressiveness or depression/emotional-social withdrawal). Our results are consistent with previous studies which have emphasized the impact of dysfunctional relationships with both parents, which are linked with a child's involvement with bullying behaviours [66; (88); 41]. Moreover, our results are consistent with recent studies who have also shown that perpetrators experience low levels of parental care and higher levels of overprotection (71). Our research findings are in agreement with those which emphasized the significance of a father's protective role as a defence against peer bullying (15, 21) and generally about caring parents who are supportive and demonstrate a caring style of parenting that reduces the possibility of their children engaging in bullying behaviours (72).

The quality of parental bonding plays an essential role in children's affective and psychosocial development and related disorders (22). In our study, one of the most significant findings regarding both parents overprotective attitude, as perceived by the children, is that consists a significant risk factor for being involved in bullying and victimization and in developing traumatic symptoms through various pathways.

Considering these results in totality, we believe that it is necessary to create a new integrative approach (92–94) of examining bullying through the lens of traumatic symptoms and the quality of parental bonding. This helps provide an assessment of deeper psychological interactions that lead to the emergence of negative emotional consequences among victims and bullies, therefore, to be able to design and establish a more comprehensible model of prevention and intervention within family and school contexts that will take into consideration the quality of family dynamics and the quality of parental bonding.

We also suggest that holistic approaches for tackling bullying should incorporate other experiential interventions (108, 113) (i.e., through stories, painting, music, art interventions), which could facilitate children to create a coherent narrative of their painful experiences, through indirect and alternative therapeutic methods, especially for those who have manifested traumatic symptoms in response to bullying and neglect. Therefore, attempts should be made to help children regain their self-esteem, a sense of emotional control and core identity by helping them better cope with family and school based interpersonal trauma. Hence, we argue that bullying can cause multiple traumatic symptoms, especially when is combined with problematic or dysfunctional family background that create a vulnerability to children or lead them to aggressive counteractions (95). Consequently, our therapeutic interventions should consider the bullying experience as a form of relational/interpersonal trauma (94) that should be placed in the context of previous family relational experiences that play an essential role as protective or risk factors (15). It is important to highlight the significant role of the therapeutic relationship when confronting trauma symptoms, so as to develop the appropriate therapeutic strategies according to the child's developmental stage (see Figure 4) or pathway and specific family context in order to re-establish trust and ensure post-traumatic growth.

We attempted to achieve a new understanding regarding bullying phenomena through the lens of traumatic relationships in order to emphasize that bullying comprises an interpersonal trauma that occurs between individuals or groups (63). One individual who has been bullied experiences a state of helplessness and weakness, similar to any other victim of a very traumatic experience, especially if these occurs in the context of very important relationships, such as parental and peer relationships, and during critical developmental stages, when children or preadolescents have not yet completed/integrated the appropriate cognitive-emotional mechanisms to properly deal with stressful situations like bullying. Therefore, it has been suggested that bullying dynamics are experienced as repeated trauma (59, 60, 112). Our study is consistent with previous research results indicating that stressful life events do play a crucial role in the development of depression (96, 97), anxiety (98), and post-traumatic stress symptoms (99). The present study also highlights the need to include problematic parental practices and bonding as stress factors that lead to victimization and bullying, often without any other factor mediation to post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Our study also emphasizes that even children who react in aggressive ways, as bullies, might have experienced problematic or destabilizing relationships with parents. A plausible clinical explanation, advanced by many experts and researchers is that aggressive and bully behaviour in this case consists a coping strategy/defence mechanism against feelings of vulnerability or even depression and low self-esteem (33). Unfortunately, bullying is often considered a normal developmental experience by several school directors and staff (62). However, the association between bullying and post-traumatic stress symptoms is considered a form of trauma (62). Several health professionals insist that children and adolescents who are exposed to extreme stress are more likely to develop serious mental health issues; therefore, bullying is very often a continuous trauma rather than an acute stressful experience (63).

We propose a therapeutic model for addressing bullying that includes post-traumatic stress symptoms; this is based on a previous model, namely the diathesis-stress model, that has received significant empirical evidence (100, 101) and has contributed to our understanding of how stressful events in the context of relationships can result in depression outcomes (102) and social exclusion (81). We do believe that bullying comprises an important stressful event that causes serious emotional disturbances to children and adolescents, regardless of the bullying role (bully, victim, bully/victim, bystander) and manner of involvement (26, 27). Our clinical intervention and hermeneutical model is also consistent with previous results, including Ferguson and Dyck's (103) and Dishion's (95) studies, who argued that it is critical to apply a model that explores the complex relational patterns within family and school contexts and considers the stress and emotional states of a child in order to better clarify the development of aggressiveness.

Bullying is not merely a dyadic problem between a bully and a victim but is rather recognized as a group phenomenon occurring in a social context where several factors operate to facilitate, prevent or hide bullying behaviours (13, 14). Our research is placed within the social/ecological model of school bullying focusing on the quality of parental bonding which is strongly related post-traumatic symptoms (104–107, 110).

As long as this is the first proposed study in Greece, to examine post-traumatic stress symptomology resulting from bullying and victimization in relation to parental bonding, we believe that our research results can have many useful implications for practice and improve bullying situation in Greek Schools, while percentages fluctuate in similar levels as other European countries.

We propose several implications for clinical and school practice considering the fact that most school interventions focusing on alleviating bullying experiences are currently ignoring the existence of PTSD symptoms. It is important to highlight that schools need to develop interventions to deal with traumatic symptoms in an appropriate way. Schools must focus on specific students who have manifested symptoms of trauma and provide psychoeducation programs. For instance, school staff could develop better awareness so as to identify the existence of post-traumatic stress symptoms in order to refer students to relevant services (i.e., individual/group therapy and/or educational interventions). School personnel could be more vigilant and sensitive to different forms of avoidance behaviours (typically higher among girls) that possibly mask a child's trauma from a bullying experience.

Every school could develop holistic and systemic programs that provide counselling and psychotherapy, as well as individual interventions, that can focus on a child's relationships with his/her family, internalizing or externalizing difficulties, and consider bullying as a form of interpersonal trauma.

One of limitation was the self-report nature of our chosen methodology. Future research should also include qualitative methods (interviews, etc.) that engage bullies and victims so as to clarify a deeper understanding of bullying and parental attitude or family relational dynamics through children's and adolescents' personal narrative/experience and a discourse analysis methodology. It also appears that in the Parental Bonding Inventory, latent variables may be perceived differently across different age groups. Thus, further research is needed in order to understand whether such differences are due to actual developmental changes in children's perceptions of the parent-child relationship or conceptual problems pertaining to children's ability to conceive the PBI's theoretical constructs. Another limitation was the small number of perpetrators sampled. Future research should recruit larger samples in order to offer a more complete picture of bullying phenomena. Given that the present study was carried out for only 1 year, we cannot treat this as a longitudinal analysis. Future longitudinal research could explore risks and protective factors, in addition to victims' and bullies' personality characteristics that are relevant to development during a longer study period. Additionally, future research should explore the bi-directionality/causality of bullying. This indicates that we should clarify a crucial question: whether the manifestation of post-traumatic stress symptoms is the result of a bullying experience or if children who experienced trauma in the past are more likely find themselves in bullying situations.

Future research should be more analytical and qualitative in order to examine comorbidities and other essential elements, including family risk and protective factors and the perceived role of masculinity in a society, as boys typically display higher percentages of all forms of bullying. We also need to examine the effect of cultural issues and ethics, social norms, and the role of each therapeutic approach in order to address bullying in schools and the community.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the supplementary files.

Written informed consent was obtained from parents of participating adolescents and children. All participants provided written consent or assent before completing the questionnaires. The study protocol was approved by the University of Crete Ethics Committee and the Ministry of Education in Greece. All parents of subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

SP, KC, TG, and DN designed the study which is part of PS Ph.D. thesis. SP wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and developed and performed the statistical analysis in conjunction with EK and TG. EK reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

I would like to thank Dr. Maria Georgiadi for her continuous encouragement, support and valuable guidance during the writing of the paper.

1. Berger KS. Update on bullying at school: science forgotten? Dev Rev. (2007) 27:90–126. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2006.08.002

2. Craig W, Harel-Fisch Y, Fogel-Grinvald H, Dostaler S, Hetland J, Simons-Morton B, et al. A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. Inter. J. Pub. Health. (2009) 54, 216–224: doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-5413-9

3. Hawker DSJ, Boulton MJ. Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta- analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2000) 41:441–69. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00629

4. Klomek AB, Marrocco F, Kleinman M, Schonfeld I, Gould MS. Bullying, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2007) 46:40–9. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242237.84925.18

5. Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. (2001) 285:2094–100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094

6. Roland E, Idsoe T. Aggression and bullying. Aggress Behav. (2001) 27:446–62. doi: 10.1002/ab.1029

7. Solberg ME, Olweus D. Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Aggress Behav. (2003) 29:239–68. doi: 10.1002/ab.10047

8. Olweus D. Bullying at Schools: What We Know and What We Can Do. Malden, MA; Oxford: Blackwell (1993).

9. Bowes L, Arseneault L, Maughan B, Taylor A, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. School, neighbourhood, and family factors are associated with children's bullying involvement: a nationally representative longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2009) 48:545–53. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819cb017

10. Herba CM, Ferdinand RF, Stijnen T, Veenstra R, Oldehinkel AJ, Ormel J, et al. Victimization and suicide ideation in the TRAILS study: specific vulnerabilities of victims. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2008) 49:867–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01900.x

11. Olweus D. Bullying at school: basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (1994) 35:1171–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01229.x

12. Salmivalli C. Bullying and the peer group: a review. Aggress Viol Behav. (2010) 15:112–20. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

13. Olweus D. Peer harassment: a critical analysis and some important questions. In: Juvonen J and Graham S, editors. Peer Harassment in School: The Plight of the Vulnerable and Victimized. Newyork, NY: Guilford Press (2001) p. 3–20.

14. Salmivalli C. Group view on victimization: Empirical findings and their implications. In Juvonen J and Graham S, editors. Peer Harassment In School: The Plight of the Vulnerable and the Victimized. NewYork, NY: Guilford Press (2001) 398–419.

15. Arsenault L, Bowes L, Caspi A, Maughan B, Moffitt TE. Families promote emotional and behavioural resilience to bullying: evidence of an environmental effect. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2010) 51:809–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02216.x

16. Klomek AB, Sourander A, Niemela S, Kumpulainen K, Piha J, Tamminen T, et al. Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: a population-based birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2009) 48:254–61. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318196b91f

17. Roland E. Aggression, depression and bullying others. Aggress Behav. (2002) 28:198–206. doi: 10.1002/ab.90022

18. Smith PK. Commentary III. Bullying in life-span perspective: What can studies of school bullying and workplace bullying learn from each other? J Commun Appl Psychol. (1997) 7:249–55.

19. Carlisle N, Rofes E. School bullying: do adult survivors perceive long-term effects? Traumatol. (2007) 13:16–26. doi: 10.1177/1534765607299911

20. Mitsopoulou E, Giovazolias T. The relationship between perceived parental bonding and bullying: The mediating role of empathy. Eur J Counsel Psychol. (2013) 2:1–16. doi: 10.5964/ejcop.v2i1.2

21. Flouri E, Buchanan A. Life satisfaction in teenage boys: the moderating role of father involvement and bullying. Aggress Behav. (2002) 28:126–33. doi: 10.1002/ab.90014

22. Rohner RP. Introduction to interpersonal acceptance-rejection theory (IPAR Theory) and evidence. Online Readings Psychol Cult. (2016) 6:2–40. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1055

23. Andreou E. Bullying/Victims problems and their association with coping behaviour in conflictual peer interactions among school-age children. Educ Psych. (2001) 21:59–66. doi: 10.1080/01443410125042

24. Beaty LA, Alexeyev EB. The problem of school bullies: what research tells us. Adolesc. (2008) 43:1–11.

25. Copeland W, Wolke D, Anglod A, Costello J. Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatr. (2013) 70:419–26. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504

26. Ferguson CJ, San Miguel C, Hartley RD. A multivariate analysis of youth violence and aggression: The influence of family, peers, depression, and media violence. J Pediatr. (2009) 155:904–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.06.021

27. Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpelä M, Rantanen P, Rimpelä A. Bullying at school—An indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. J. Adolescence. (2000) 23:661–674. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0351

28. Kochenderfer-Ladd B, Ladd GW. Variations in peer victimization: relations to children's maladjustment. In Juvonen J and Graham S, editor. Peer Harassment in School: The Plight of the Vulnerable and Victimized. NewYork, NY: Guilford Press. (2001). p. 25–48.

29. Kumpulainen K, Räsänen E, Puura K. Psychiatric disorders and the use of mental health services among children involved in bullying. Aggress Behav. (2001) 27:102–10. doi: 10.1002/ab.3

30. Mynard H, Joseph S, Alexander J. Peer victimization and posttraumatic stress in adolescents. Person Individ Differ. (2000) 29:815–21. doi: 10.1016/S01918869(99)00234-2

31. Smith PK, Cowie H, Olafsson RF, Liefooghe APD. Definitions of bullying: a comparison of terms use, and age and gender difference, in a fourteen-country international comparison. Child Dev. (2002) 73:1119–33. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00461

32. Srabstein J, Piazza T. Public health, safety and educational risks associated with bullying behaviors in American adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. (2008) 20:223–33. doi: 10.1515/IJAMH.2008.20.2.223

33. Tsaousis I. The relationship of self-esteem to bullying perpetration and peer victimization among schoolchildren and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. (2016) 31:186–99. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2016.09.005

34. Becker-Blease KA, Deater-Deckard K, Eley T, Freyd JJ, Stevenson J, Plomin R. A genetic analysis of individual differences in dissociative behaviors in childhood and adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2004) 45:522–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00242.x

35. Liotti G. Trauma, dissociation, and disorganized attachment: Three strands of a single braid. Psychother Theory Res Pract Train. (2004) 41:472–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.41.4.472

36. Thomas PM. Dissociation and internal models of protection: Psychotherapy with child abuse survivors. Psychother Theory Res Pract Train. (2005) 42:20–36. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.42.1.20

37. Gini G, Pozzoli T. Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: a meta- analysis. Pediatr. (2013) 132:720–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0614·

38. Knack JM, Jensen-Campbell LA, Baum A. Worse than sticks and stones? bullying is associated with altered HPA axis functioning and poorer health. Brain Cogn. (2011) 77:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2011.06.011

39. Rigby K. Peer victimization at school and the health of secondary school students. Br J Educ Psychol. (1999) 69:95–104. doi: 10.1348/000709999157590

40. Elliot M. Bullies and victims. In Elliot M, editor. Bullying – A Practical Guide to Coping for Schools, 3rd ed. London: Pearson (2002). p. 1–11.

41. Marsh HW, Nagengast B, Morin AJS, Parada RH, Craven RG, Hamilton LR. Construct validity of the multidimensional structure of bullying and victimization: an application of exploratory structural equation modeling. J Educ Psychol. (2011) 103:701–32.

42. Rigby K. Bullying in Schools and What To Do About It. Melbourne, VIC: Council for Educational Research (1996).

43. Card NA, Isaacs J, Hodges EVE. Correlates of school victimization: Implications for prevention and intervention In: Zins JE, Elias MJ, Maher CA, editors. Bullying, Victimization, and Peer Harassment: A Handbook of Prevention and Intervention. New York, NY: Haworth Press (2007). p. 339–66.

44. Graham S, Bellmore A, Juvonen J. Peer victimization in middle school: when self- and peer views diverge. In: Zins JE, Elias MJ, Maher CA, editors. Bullying, Victimization, and Peer Harassment: A Handbook of Prevention and Intervention. New York, NY: Haworth Press. (2007). p. 121–141.

45. Juvonel J, Nishina A, Graham S. Peer harassment, psychological adjustment, and school functioning in early adolescence. J. Educ. Psychol. (2000) 92:349–359. doi: 10.1037//0022-0663.92.2.349

46. Konishi C, Hymel S, Zumbo BD, Li Z. Do school bullying and student-teacher relations matter for academic achievement? A multilevel analysis. Can J Sch Psychol. (2010) 25:19–39. doi: 10.1177/0829573509357550

48. Mikkelsen EG, Einarsen S. Basic assumptions and symptoms of post-traumatic stress among victims of bullying at work. Eur J Work Org Psychol. (2002) 11:87–111. doi: 10.1080/13594320143000861

49. Tehrani N. Bullying: A source of chronic post-traumatic stress? Br J Guidance Counsel. (2004) 32:357–66. doi: 10.1080/03069880410001727567

50. Field T. Bully In Sight: How to Predict, Resist, Challenge and Combat Workplace Bullying, 4th ed. Oxford: Success Unlimited (2001).

51. Idsoe T, Dyregrov A, Cosmovici E. Bullying and PTSD symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2012) 40:901–11. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9620-0

52. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

53. Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, Layne CM, Briggs EC, Ostrowski SA, Fairbank JA. DSM-V PTSD diagnostic criteria for children and adolescents: a developmental perspective and recommendations. J Traum Stress. (2009) 22:391–8. doi: 10.1002/jts.20450

54. Lancaster SL, Melka SE, Rodriguez BF. An examination of the differential effects of the experience of DSM-IV defined traumatic events and life stressors. J Anxiety Disord. (2009) 23:711–7. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.02.010

55. Nader R, Koch WJ. Does Bullying Result in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder? (2006). Available online at: http://www.drwilliamkoch.com/articles/~Bullying%20and%20PTSD%20Review.doc (accessed December, 2018).

56. Rivers I. Recollections of bullying at school and their long-term implications for lesbians, gay men and bisexuals. Crisis. (2004) 24:169–75. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.25.4.169

57. McKenney KS, Pepler D J, Craig WM, Connolly JA. Psychosocial consequences of peer victimization in elementary and high school - an examination of posttraumatic stress disorder Symptomatology. In: Kendall-Tackett KA and Giacomoni SM, editors. Child Victimization. Maltreatment, Bullying and Dating Violence, Prevention and Intervene. Kingston, NJ: Civic Reserach Institute (2002). 151–157.

58. Veenstra R, Lindenberg S, Oldehinkel AJ, De Winter AF, Verhulst FC, Ormel J. Bullying and victimization in elementary schools: A comparison of bullies, victims, bully/ victims, and uninvolved preadolescents. Dev Psychol. (2005) 41:672. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.672

60. Terr L. Childhood traumas: an outline and overview. Amer J Psychiatr. (1991) 148:10–20. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.1.10

61. Meiser-Stedman R, Smith P, Glucksman E, Yule W, Dalgleish T. Parent and child agreement for acute stress disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and other psychopathology in a prospective study of children and adolescents exposed to single-event trauma. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2007) 35:191–201. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9068-1

62. Kay B. A Cross National Study of Bullying Experienced by British and American School Children: Determining a Typology of Stressors and Symptoms. Philadelphia: Temple University. (2005).

63. McLaughlin L, Laux JM, Pescara-Kovach L. Using multimedia to reduce bullying and victimization in third-grade urban schools. Profess Sch Counsel. (2006) 10:153–60.

64. Rigby K. Psychosocial functioning in families of Australian adolescent schoolchildren involved in bully/victim problems. J Fam Ther. (1994) 16:173–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6427.1994.00787.x

65. Baldry AC. Bullying in schools and exposure to domestic violence. Child Abuse Negl. (2003) 27:713–32. doi: 10.1016/S01452134(03)00114-5

66. Baldry AC, Farrington DP. Bullies and delinquents: Personal characteristics and parental styles. J Commun Appl Soc Psychol. (2000) 10:17–31. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1298

67. Georgiou SN. Parental style and child bullying and victimization experiences at school. Soc Psychol Edu. (2008) 11:213–27. doi: 10.1007/s11218-007-9048-5

68. Conners-Burrow N, Johnson D, Whiteside-Mansell L, Mckelvey L, Gargus R. Adults matter: protecting children from the negative impacts of bullying. Psychol Sch. (2009) 46:593–604. doi: 10.1002/pits.20400

69. Fite J, Greening L, Stoppelbein L. Relation between parenting stress and psychopathic traits among children. Behav Sci Law. (2008) 26:239–48. doi: 10.1002/bsl.803

70. Cummings-Robeau L, Lopez G, Rice G. Attachment-related predictors of college students' problems with interpersonal sensitivity and aggression. J Soc Clin Psychol. (2009) 28:364–91. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2009.28.3.364

71. Mohebi M, Mirnasab M, Wiener J. Parental and school bonding in Iranian adolescent perpetrators and victims of bullying. Sch Psychol Inter. 37, 1–23. doi: 10.1177/0143034316671989

72. Shetgiri H, Avila R, Flores G. Parental characteristics associated with bullying perpetration in US children aged 10 to 17 years. Res Pract. (2012) 102:2280–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300725

73. Bokszczanin A. PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents 28 months after a flood: age and gender differences. J Trauma Stress. (2007) 20:347–51. doi: 10.1002/jts.202

74. Laufer A, Solomon Z. Gender differences in PTSD in Israeli youth exposed to terror attacks. J Interpers Violence. (2009) 24:959–76. doi: 10.1177/0886260508319367

75. Sideridis G, Kafetsios K. Perceived parental bonding, fear of failure and stress during class presentations. Inter J Behav Dev. (2008) 32:119. doi: 10.1177/0165025407087210

76. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. (2007) 39:175–191. doi: 10.4236/psych.2015.64033

77. British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy. Ethical Framework for the Counselling and Psychotherapy Professions. London: Rigby (2018)

80. Deliyanni-Kouimtzi K, Athanasiadou C, Konstan-tinou K, Papathanasiou M, Psalti A. Taetotetes fuloe, Ethnikes Taetotetes Kai Scholike via. Ereenontas te via kai te thematopoiese sto scholiko choro [Gender identity, national iden- tities and school violence. Investigation of violence and victimization in the school envi- ronment]. Enthiamese ekthese toe proyramma- tos Pethayoras, Periothos 1/3/2004-31/3/005 (2005).

81. Gazelle H, Ladd GW. Anxious solitude and peer exclusion: a diathesis-stress model of internalizing trajectories in childhood. Child Dev. (2003) 74:257–78.

82. Soberman GB, Greenwald R, Rule DL. A controlled study of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for boys with conduct problems. In: R. Greenwald, editor Trauma and Juvenile Delinquency: Theory, Research, and Intervention. New York: The Haworth Maltreatment & Trauma Press. (2002) 217–235.

83. Greenwald R, Rubin A. Assessment of posttraumatic symptoms in children: development and preliminary validation of parent and child scales. Soc Pract. (1999) 9:61–75.

84. Corcoran K, Fischer J. Measures for Clinical Practice: A Sourcebook, volume 1: Couples, Families, And Children, 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Free Press. (2000).

85. Tsaousis I, Mascha K, Giovazolias T. Can parental bonding be assessed in children? Factor structure and factorial invariance of the parental bonding instrument (PBI) between adults and children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2012) 43:238–53. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0260-3.

87. Howitt D, Cramer DC. Introduction to SPSS in Psychology. London, UK: Pearson Education Limited (2010).

89. Greenwald R. The role of trauma in conduct disorder. In Greenwald R, editor Trauma and Juvenile Delinquency: Theory, Research, and Interventions. New York: Haworth Press, (2002a) 5–23.

90. Greenwald R.Trauma and Juvenile Delinquency: Theory, Research, and Interventions. New York, NY: Haworth Press (2002b).

91. Kourkoutas E. Behavioural Disorders in Children: Ecosystemic Psychodynamic Interventions Within Family and School Context. New York, NY: Nova science (2012).

92. Blitz LV, Lee Y. Trauma informed methods to enhance school-based bullying prevention initiatives: an emerging model. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (2015) 24:20–40. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2015.982238

93. Palmer S, Woolfe R. Integrative and Eclectic Counselling and Psychotherapy. London: Sage (2000).

94. Sanderson C. Counselling Skills for Working with Trauma. London: Jessica Kingsley Publisher (2013).

95. Dishion TJ. A developmental model of aggression and violence: Microsocial and macroso-cial dynamics within an ecological framework. In Lewis M, Rudolph D, editor Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. New York, NY: Springer (2014) p. 449–465.

96. Garber J, Horowitz JL. Depression in children. In: Gotlib IH and Hammen CL, editor Handbook Of Depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press. (2002) p. 510–40.

97. Hammen C, Rudolph KD. Childhood mood disorders. In Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editor Child Psychopathology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press (2003). p. 233–78.

98. Leen-Feldner EW, Zvolensky MJ, Feldner MT. A test of a cognitive diathesis–stress model of panic vulnerability among adolescents. In Sanfelippo AJ, editor. Panic Disorders: New Research. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Biomedical Books (2006). p. 41–64.

99. Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ, Feldner MT, Lewis SF, Fauber AL, Leen-Feldner EW, et al. Anxiety sensitivity taxon and trauma: Discriminant associations for post-traumatic stress and panic symptomatology among young adults. Depress. Anxiety. (2005) 22:138–49. doi: 10.1002/da.20091

100. Garber J, Hilsman R. Cognitions, stress, and depression in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. (1992) 1:129–67. doi: 10.1016/S1056-4993(18)30615-1

101. Gibb BE, Alloy LB. A prospective test of the hopelessness theory of depression in children. J Clin Child Adol Psychol. (2006) 35:264–74. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_10

102. Chango JM, McElhaney KB, Allen JP, Schad MM, Marston E. Relational stressors and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: rejection sensitivity as a vulnerability. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2012) 40:369–79. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9570-y

103. Ferguson CJ, Dyck D. Paradigm change in aggression research: The time has come to retire the general aggression model. Aggress Viol Behav. (2012) 17:220–8. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.02.007

104. Espelage DL, Rao MA, de la Rue L. Current research on school-based bullying: A social-ecological perspective. J. Soc. Distress. Homeless. (2013) 22:21–7. doi: 10.1179/1053078913Z.0000000002

105. Hong JS, Garbarino J. Risk and protective factors for homophobic bullying in schools: An application of the social-ecological framework. Educ Psychol Rev. (2012) 24:271–85. doi: 10.1007/s10648-012-9194-y

106. Swearer SM, Espelage DL. A social-ecological framework of bullying among youth. In Espelage L and Swearer SM, editor Bullying in American schools: A Social-Ecological Perspective on Prevention and Intervention. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, (2004) p. 1–12.

107. Swearer SM, Espelage DL, Koenig B, Berry B, Collins A, Lembeck P. A social-ecological model of bullying prevention and intervention in early adolescence. In: Jimerson SR, Nickerson A. B, Mayer MJ, Furlong MJ, editor Handbook of School Violence and School Safety. New York, NY: Routledge (2012).p. 333–355.

109. Greenwald R. Psychometric review of the problem rating scale. In: Stamm BH, editor. Measurement of Stress, Trauma, and Adaptation. Lutherville, MD: Sidran (1996). p. 242–3.

110. Espelage DL, Swearer SM. A social-ecological model for bullying prevention and intervention: understanding the impact of adults in the social ecology of youngsters. In: Jimerson SR, Swearer SM, Espelage DL, editors, Handbook of Bullying in Schools: An International Perspective. New York, NY: Routledge (2010). p. 61–72.

Keywords: bullying, victimization, parental bonding, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, trauma

Citation: Plexousakis SS, Kourkoutas E, Giovazolias T, Chatira K and Nikolopoulos D (2019) School Bullying and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms: The Role of Parental Bonding. Front. Public Health 7:75. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00075

Received: 11 February 2019; Accepted: 15 March 2019;

Published: 09 April 2019.

Edited by:

Marie Leiner, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Raúl Navarro, University of Castilla La Mancha, SpainCopyright © 2019 Plexousakis, Kourkoutas, Giovazolias, Chatira and Nikolopoulos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stefanos Stylianos Plexousakis, c19wbGV4QGhvdG1haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.