- Office of Public Health Studies, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, United States

Engagement of undergraduate public health students in active learning pedagogy has been identified as critical for recruitment, retention, and career preparation efforts. One such tool for engagement that has proven successful in STEM programs is deliberative pedagogy, where it is used to stimulate student interest in research and policy applications of technical course content. Broadly applied, deliberative pedagogy is a consensus model of decision-making, applied as an in-class exercise, where students work in small groups and model a community task force with assigned group roles. In these groups, students collect evidence from literature and media sources, and prepare a consensus response to an assigned question. Here we present an adaptation of this pedagogy to provide undergraduates with the tools needed to actively engage in public health policy and planning work groups. This adaptation is first applied during an introductory public health course, where it is used as a tool for engagement and excitement, and as a critical thinking exercise. It additionally serves as an opportunity for students to apply information literacy skills and engage with research and policy initiatives discussed in class. The same tool is reintroduced prior to graduation in a capstone course, where the emphasis shifts to application of research skills and analytical concepts. The activity is also an opportunity for students to apply professional skills needed for engagement in program development, program evaluation, institutional policy, and legislative advocacy. Through application of this pedagogical tool at two critical time points in an undergraduate curriculum, students develop skills necessary for early career professionals and are better prepared to actively engage in policy and planning as it relates to critical public health initiatives, both locally and globally.

Background and Rationale

Education of undergraduate students involves a need to introduce, reinforce, and apply basic professional skills, in addition to imparting core content knowledge. Undergraduate education traditionally includes foundational general education courses for this purpose; it is also important for the student's specific degree program to facilitate application of professional skills within the framework of major-specific graduation criteria.

In the last decade there has been a dramatic expansion of public health education from it's historic focus on graduate education and curriculum design into undergraduate programs1,2 As a result, public health programs and faculty have needed to gain a better understanding of undergraduate student pedagogical needs beyond mastery of introductory public health-specific skills and content knowledge.

Employer assessments of college graduates further supports the need for graduates to demonstrate professional skills in critical thinking, team work and collaboration, and in the ability to apply quality information and data to solve real-world challenges. In a job outlook report conducted and published by the National Association of Colleges and Employers, 82.9% of surveyed respondents reported a need for problem-solving, teamwork, and leadership, with an equivalent 82.9% reporting a demand for graduates to demonstrate an ability to work as a team (1). In a similar study compiled at the request of the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U), employers reported asking for increased college-level emphasis on integrative learning (73% of respondents), teamwork skills (76%), critical thinking and analytical reasoning skills (73%), and the ability to locate, organize, and evaluate information from multiple sources (70%) (2).

The literature further supports the need to incorporate active learning pedagogy for increased student engagement (3, 4) and performance (5), which may have further implications for student recruitment and retention efforts.

Deliberative pedagogy is a consensus model of decision-making intended to model the function of a community task force (6). Applied in an educational setting as an in-class exercise, students work in small groups in the capacity of assigned group roles. In these groups, students work collaboratively to collect evidence from literature and media sources, then critically appraise and apply this evidence to develop a consensus response to an assigned question. Through employment of this pedagogical practice at two strategic time points in an undergraduate public health curriculum, students develop, and practice workplace-oriented skills in critical thinking, information appraisal and literacy, and teamwork/collaboration. Students are additionally prepared to actively engage in real-world public health challenges and apply quality information to professional engagement in program planning and policy development.

Pedagogical Framework

Three high-impact educational practices are predominantly reflected in application of deliberative pedagogy. By nature, deliberative pedagogy is a collaborative project, conducted in small student groups, and requires undergraduate students to engage in research practices to find and evaluate credible evidence relevant to their assigned prompt questions. Application of both collaborative projects and undergraduate research are high impact educational practices (7). Focus topics of assigned group prompt questions further reflect values of diversity and global learning, another high-impact educational practice (7). Prompts assigned often focus on public health issues of global importance or implication, or local issues with broad implications. Diversity of opinion is promoted during discussion, most notably represented by the student designated as the “devil's advocate” of the group, as is the practice of applying high quality evidence to support the group's final consensus statement.

Deliberative democracy pedagogy applies several critical component elements (CCEs) identified by the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH)3, and additionally utilizes Liberal Education and America's Promise (LEAP) learning objectives (8, 9). Relevant objectives relate to inquiry and analysis, critical thinking, information literacy, teamwork, problem solving, and social responsivity.

Team-based experiential learning approaches, as applied through deliberative pedagogy, have been shown to be effective in higher education broadly (10, 11), and specifically in application within public health education (12). Peer group learning, applied in small, semi-independent group settings, has been effective in promoting higher order skills in higher education (13), and inquiry-based activities applied in small groups have promoted the mastery of complex material among students (14). Undergraduate programs have been successful in application of a deliberative pedagogy to increase student ability to evaluate and synthesize information, and to actively engage in civic issues engagement (6, 15). The literature further provides support of the effectiveness of deliberative pedagogy in comparison to standard lecture format as evidenced by changes in student self-reported understanding of course content and increases in assessment-based content knowledge (15).

Learning Environment

The University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (UHM) is a public research university with enrollment of 17,612 students, and undergraduate students comprising about 73% of enrollees4 Public health education began at UHM in 1962 with the offering of graduate-level public health degrees. The Bachelor of Arts in public health (BAPH) degree was added in January 2014, has produced more than 140 graduates, and currently supports approximately 170 declared majors.

Deliberative pedagogy was introduced into public health courses at UHM in fall 2015, and is currently applied at two strategic time points throughout the BAPH curriculum at UHM. It is first introduced during our PH 201 (Introduction to Public Health) course. In this course, the target audience centers on new and prospective undergraduates. As a large lecture format general education course, many, but not all, enrolled students are interested in further pursuing public health as a future field of study. Enrollment in the courses often ranges from 70 to 100 students per class. As an introductory course, the students frequently have no prior exposure to public health concepts and the emphasis of the pedagogy centers on introducing and applying basic public health concepts and skills, including critical thinking skills, collaborative learning, and both collection, and application, of high-quality evidence. The application of this pedagogy further serves to promote awareness among new public health students of current issues of public health concern (e.g., climate change).

Early offerings of the PH 201 course had a small class size, ranging from 30 to 40 students per semester. In-class student debates on public health topics were employed as critical thinking exercises for students when class sizes were small. However, as enrollment in PH 201 increased in subsequent semesters, application of deliberative pedagogy replaced the student debate activities as an approach to scale the activity, while meeting similar critical thinking objectives.

This pedagogy is again applied during our PH 489 (Public Health Undergraduate Capstone Seminar) course. This is often the last public health course students enroll in prior to graduation. As the capstone course, it is intended to integrate students' prior classroom learning with the exposure to public health practice attained through their capstone service-learning or research experience, and to prepare students to enter the workforce or graduate study. As such, the target audience is advanced public health majors who have completed their required public health capstone projects and most, if not all, required coursework in public health. In this course, the emphasis of deliberative pedagogy shifts to center on career preparation and real-world application of public health skills and content. As a university designated writing intensive seminar format course, enrollment is set at a maximum of 20 students per class.

Learning Objectives

While the deliberative pedagogy and approach is consistently applied throughout the curriculum, it has slightly different goals depending on the course, and subsequently the target audience of students, in which it is being implemented.

Learning objectives of the deliberative pedagogy in PH 201 (Introduction to Public Health) include the following:

1. Introducing and applying critical thinking skills on public health topics

2. Practicing research and investigative skills in population health

3. Identifying and interpreting quality resources in popular and professional literature

4. Exposing students to current controversies and discussions in the field

5. Making connections to public health practice.

Learning objectives of the deliberative pedagogy in PH 489 (Public Health Undergraduate Capstone Seminar) include the following:

1. Reinforcing students' critical thinking skills in public health practice

2. Applying public health skills and concepts to controversies and discussions that students may encounter as early career professionals

3. Gaining practice in teamwork, collaborative problem-solving, and policy development within a public health practice context

4. Integrating public health knowledge with practice in policy analysis

5. Gaining experience in professional communications for policy advocacy

Pedagogical Format

Deliberative Pedagogy is a consensus decision-making activity modeled on task force protocol. Students work collaboratively in small groups to practice using critical thinking and teamwork to identify information needs and collect evidence, then develop, present, and defend a consensus position on an ethical issue in public health.

Preparation activities require 30–45 min of time allotted in-class to organize the group and plan work. Groups of 4–6 students are pre-assigned into designated group roles by the instructor, primarily for efficiency, but also to challenge students in roles they may not ordinarily have selected for themselves. Each group is assigned a focus question to investigate, and given a worksheet that prompts them to assign team roles, identify the underlying public health issues, develop the group's initial stance on the focus question, identify sub-questions to investigate and potential sources of evidence. Following in-class small group discussion, students are allotted 1–2 weeks for group members to investigate questions identified by the group discussion and collect data.

After the allotted time for research and collection of evidence, groups reconvene in class to review data and develop, present and defend their team's evidence-based consensus statement on the focus question. A final group worksheet documents consensus statement, team member roles, key pieces of evidence with American Psychological Association (APA) citations, and criteria for validity. A full class session is dedicated to this effort and includes 45–60 min for discussion and statement development, as well as 15 min for presentation/large group discussions.

In PH 489, where the deliberative democracy activities also are intended to reinforce teamwork as a critical public health job skill, an additional element is added between the two deliberative democracy activities. After the completion of the first deliberative democracy project, students are guided through an in-class discussion to reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of their teamwork, and uncover for themselves core concepts in team functioning. This understanding is then reinforced through a lecture and guided small-group activities on teamwork. Students are then organized into groups for the second deliberative democracy assignment, and each group is required to develop a team contract that addresses individual responsibilities, team rules and consequences.

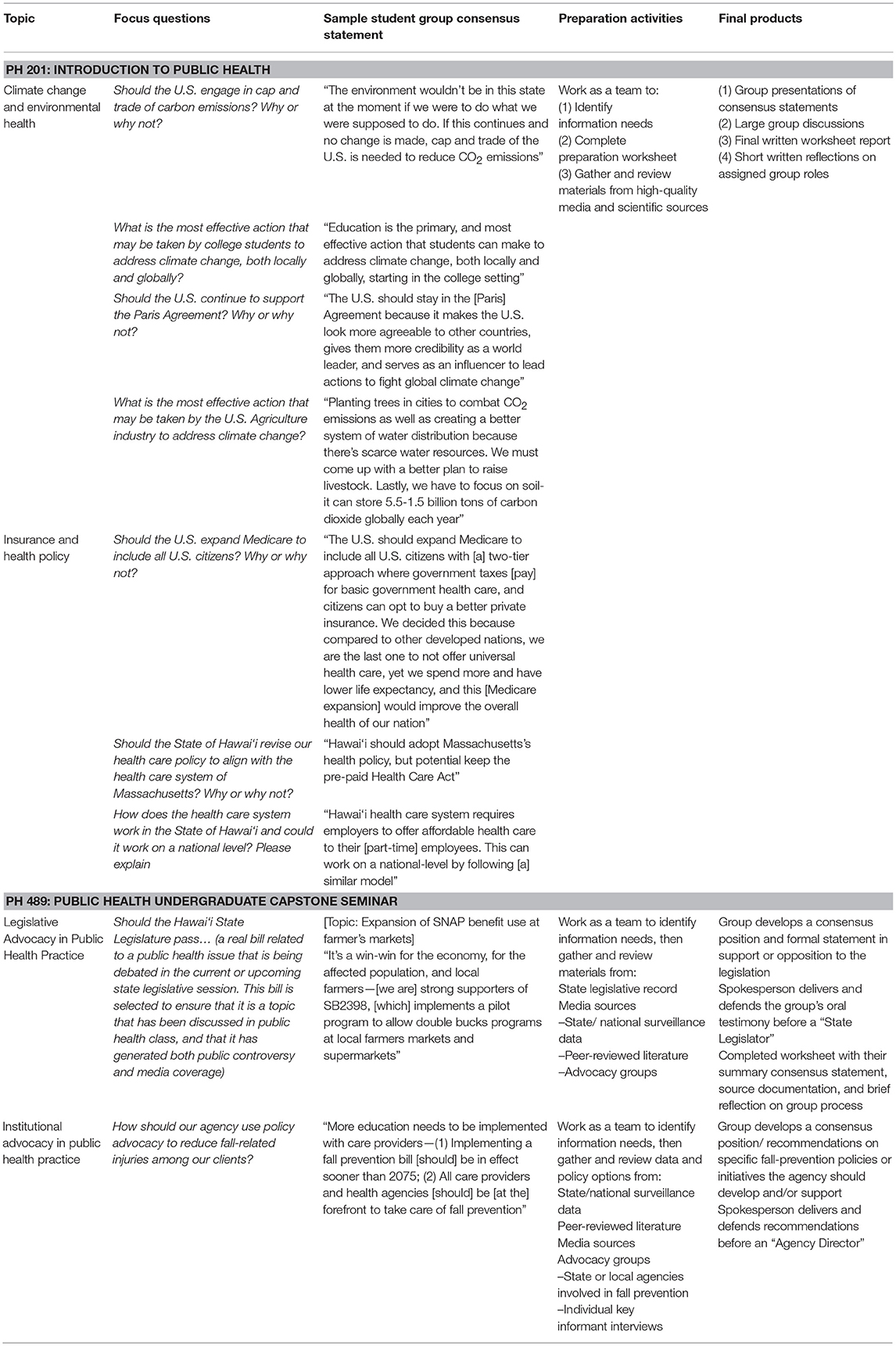

Deliberative democracy pedagogy is implemented twice during PH 201- once centered on a topic of environmental health importance, and later centered on a topic of health policy relevance. During PH 489, it is implemented twice- once centered on a topic of legislative advocacy, and later centered on a topic of community health and institutional policy. More specific details describing application of deliberative pedagogy in each PH 201 (Introduction to Public Health) and PH 489 (Public Health Undergraduate Capstone Seminar) are described in Table 1.

Outcomes and Assessment Results

Since the deliberative democracy pedagogy is applied in slightly different ways, with variations in learning objectives, during two distinct courses within the UHM public health curriculum, outcome and assessment data are presented here separately.

PH 201 (Introduction to Public Health) Outcomes and Assessment

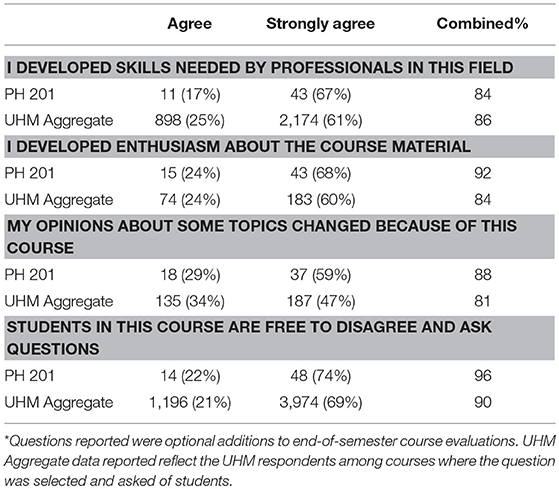

When applied in PH 201 (Introduction to Public Health), deliberative democracy pedagogy is a emphasized as a tool through which college freshmen and sophomores with minimal background in public health apply basic public health concepts and skills, including critical thinking skills, collaborative learning, and application of high-quality evidence. The pedagogy also helps to encourage awareness of key public health issues, and promote student enthusiasm in the undergraduate degree program and in public health careers. PH 201 end-of-semester course evaluation data corresponding to the most recent semester, Spring 2018, is provided in Table 2 as compared to aggregated data from the full UHM campus.

In coding of open-ended responses on the most current PH 201 course evaluation (Spring 2018, n = 64 responses), the top two coded reponses to “what do you feel was the most valuable aspect of this course?” was interactions or discussions (8 responses) and specifically named deliberative democracy discussions (7 responses). In a free comments section, the most common feedback (8 responses) indicated students wanted deliberative democracy activities to be expanded or utilized more frequently in the course.

Anecdotal evidence from end-of-semester interviews conducted with instructors of public health courses taken by students following PH 201 suggests students are able to better distinguish between high and low quality evidence, and are better able to recognize when data are needed to support claims, compared to student demonstration of skills prior to implementation of deliberative democracy pedagogy.

PH 489 (Undergraduate Public Health Capstone) Outcomes and Assessment

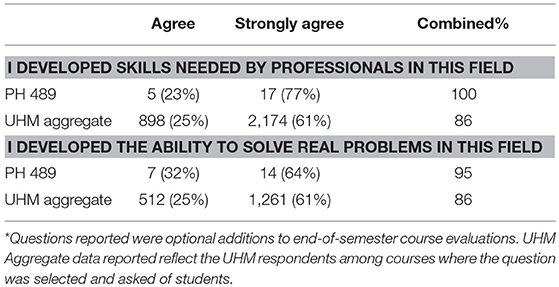

When applied in PH 489 (Undergraduate Public Health Capstone), deliberative democracy pedagogy is a career development tool promoting application of professional skills, and encouraging engagement of early career professionals in policy development and analysis. The pedagogy is intended to strengthen students' awareness of the role of policy advocacy in public health practice, to build students' familiarity with common data sources used in policy analysis, and to reinforce critical-thinking, professional teamwork and professional communication skills related to public health policy advocacy. PH 489 end-of-semester course evaluation data corresponding to the most recent semester, Spring 2018, is provided in Table 3 as compared to aggregated data from the full UHM campus.

Open-ended responses to a question asking students to identify the most valuable parts of the course were coded. More than half (9 out of 14) of the comments identified in-class group activities like the deliberative democracy activities as the most valuable part of the class. They felt that these activities were valuable because they “helped me remember key points about public health,” “involved practice of real-world skills,” or “involved preparation for public health careers.”

Since the BAPH program is relatively new, data gathered from employers of graduates is pending, however, an employer survey is currently being developed with plans for deployment within the academic year.

Discussion

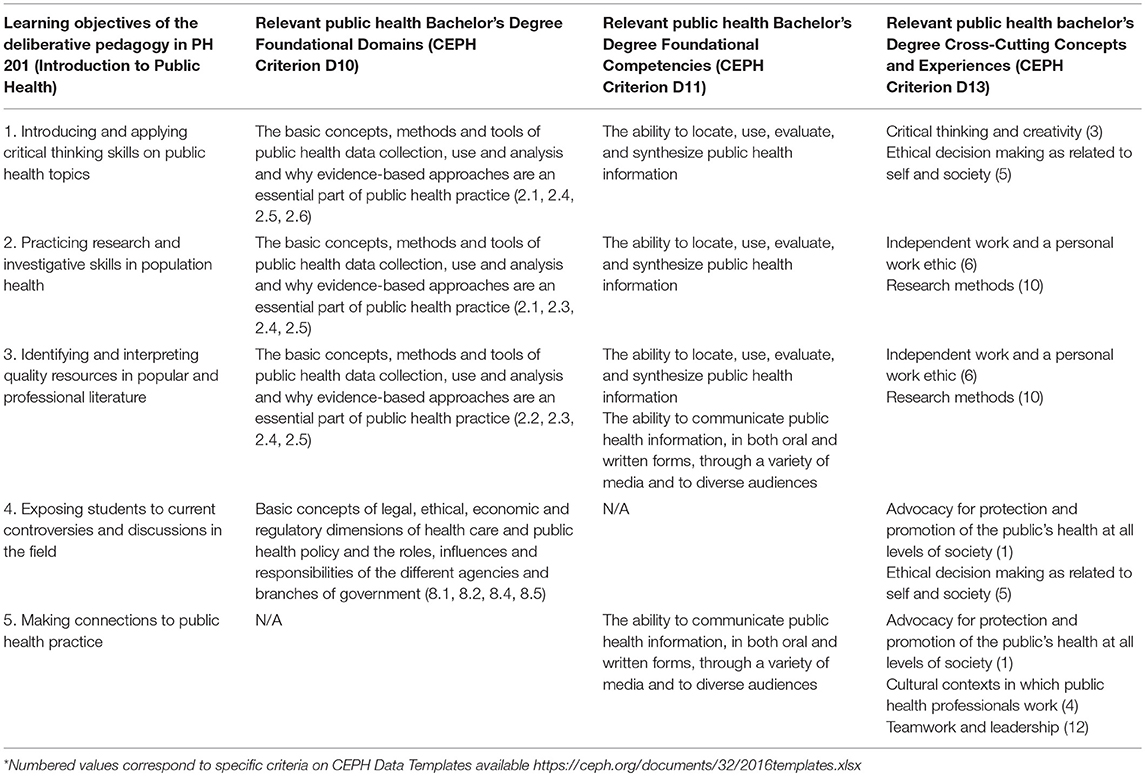

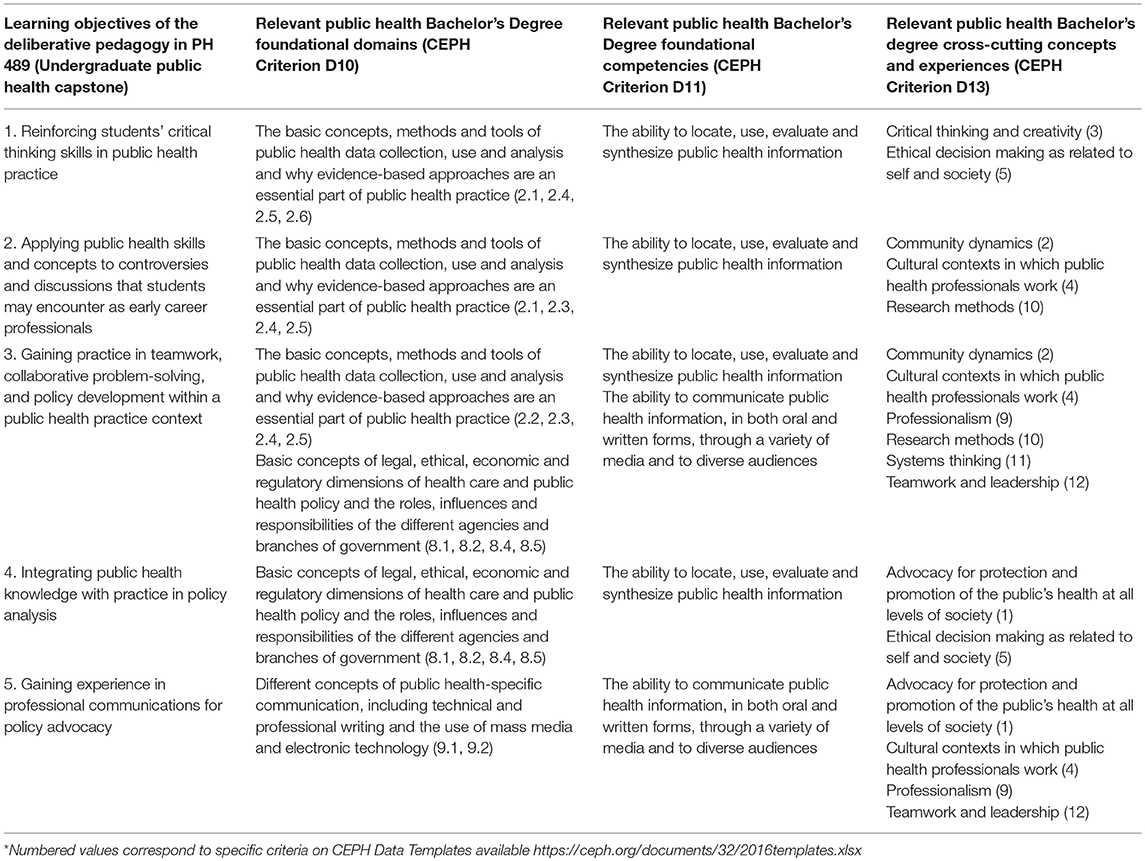

Deliberative Democracy activities can foster critical thinking and help students make the link between policy and the concrete public health practice experiences (6, 15). Deliberative Democracy activities are closely related to task force or team activities routinely performed in public health practice, and can be an effective tool for career preparation. Learning objectives associated with Deliberative Democracy, also integrate well with public health Bachelor's degree program competencies as outlined by CEPH (Council on Education for Public Health) accreditation criteria (16) D10 (Public Health Bachelor's Degree Foundational Domains), D11 (Public Health Bachelor's Degree Foundational Competencies), and D13 (Public Health Bachelor's Degree Cross-Cutting Concepts and Experiences) as outlined in Tables 4, 5.

Table 4. Learning Objectives of Deliberative Pedagogy in PH 201 (Introduction to Public Health) Mapped with CEPH (Council on Education for Public Health) Accreditation Criteria*.

Table 5. Learning objectives of deliberative pedagogy in PH 489 (Undergraduate Public Health Capstone) Mapped with CEPH (Council on Education for Public Health) Accreditation Criteria*.

Throughout application of deliberative pedagogy at two strategic curriculum time points, student feedback and assessment activities lead to adaptations and evolution of pedagogical application. In working with a large, lecture-format course of introductory public health students within the framework of PH 201, it was clear that careful instruction and repetition was important, as was continuous monitoring during discussions. Preparation for deliberative pedagogy class sessions must include curricula focused on critical thinking, finding quality resources, and evaluating evidence, which were found to be essential in providing an adequate foundation of skills to apply during deliberative pedagogy sessions. The use of multiple focus, or prompt, questions was necessary to expose students to a range of issues related to a central topic, and avoid redundancy during report-back. Logistically, advanced assignment of student groups and designated roles was found to maximize time spent on discussion, rather than logistics. Grading of preparation activities and final products separately was also identified as necessary to address student absences during one of the two designated class sessions.

In applying deliberative pedagogy in a seminar-format course with advanced public health students within the framework of PH 489, we found students required prompting and specific guidance from the instructor to link the in-class deliberative pedagogy policy activities to related content introduced during prior courses. This is further supported by literature articulating the benefits of repetition throughout an undergraduate degree curriculum (17). Logistically, adding a class session between the first and second deliberative pedagogy sessions where students reflect on collaborative team function and discussed professional teamwork skills was found to enhance student skill development in the second session. Specifying a broad range of information sources to consult for policy questions supported advanced students in understanding the range of practical factors agency staff and leadership may weigh in developing an agency response to a public health concern. Finally, deliberative pedagogy sessions were found to have greater salience for advanced students when the connection to public health career skills was made explicit throughout the activity.

Deliberative Democracy pedagogy is successfully applied at UHM during two critical time points in the undergraduate public health curriculum. Data suggests it is successful in meeting intended learning objectives, including the application of critical thinking skills and promoting the linkage between policy and the concrete public health practice experiences. Deliberative Democracy activities are closely related to task force or team activities routinely performed in public health practice, and can be an effective tool for career preparation.

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the University of Hawai‘i (UH) Human Studies Program as exempt from federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. Authority for the exemption applicable is documented in the Code of Federal Regulations at 45 CFR 46.101(b) 4. The protocol was approved by the Office of Research Compliance, University of Hawai‘i system (Protocol Number 2018-00751).

Author Contributions

DN-H: initial conception and adaptation of the pedagogy to both courses; DN-H and OB: contributed substantial reformatting of the pedagogy; DN-H: wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Both authors wrote sections of the manuscript, contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Contributions by DN-H partially funded in relation to Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity (BUILD): Enhancing Cross Disciplinary Infrastructure and Training at Oregon (EXITO), funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (1RL5MD009591-01).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge initial introduction to this pedagogy provided through project-related discussions as a part of Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity (BUILD): Enhancing Cross Disciplinary Infrastructure and Training at Oregon (EXITO) project funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (1RL5MD009591-01). Curriculum development support related to the PH 489 course provided by Ms. Michelle Tagorda. The authors gratefully acknowledge their contributions.

Footnotes

1. ^https://bigfuture.collegeboard.org/majors/health-professions-related-clinical-sciences-public-health-public-health

2. ^https://www.aspph.org/connect/data-center/

References

1. National Association of Colleges and Employers. The Key Attributes Employers Seek on Students' Resumes [Internet]. [cited Oct 28, 2018]. (2018) Available online at: https://www.naceweb.org/about-us/press/2017/the-key-attributes-employers-seek-on-students-resumes/

2. Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Inc. How Should Colleges Prepare Students To Succeed In Today's Global Economy? [Internet]. (2006) p. 14. Available online at: https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/2007_full_report_leap.pdf

3. Armbruster P, Patel M, Johnson E, Weiss M. Active learning and student-centered pedagogy improve student attitudes and performance in introductory biology. CBE Life Sci Edu. (2009) 8:203–13. doi: 10.1187/cbe.09-03-0025

4. Prince M. Does active learning work? A review of the research. J Eng Edu. (2004) 93:223–31. doi: 10.1002/j.2168-9830.2004.tb00809.x

5. Freeman S, Eddy SL, McDonough M, Smith MK, Okoroafor N, Jordt H, et al. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2014) 111:8410–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319030111

6. Shaffer T, Longo N, Manosevitch I, Thomas M. (eds.). Deliberative Pedagogy: Teaching and Learning for Democratic Engagement. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press (2017).

7. Kuh GD, O'Donnell K, Reed SD. Ensuring Quality & Taking High-Impact Practices to Scale. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities, & Liberal Education and America's Promise (Program) (2013).

8. Petersen DJ, Albertine S, Plepys CM, Calhoun JG. Developing an educated citizenry: the undergraduate public health learning outcomes project. Public Health Rep. (2013) 128:425–430. doi: 10.1177/003335491312800517

9. Wykoff R, Petersen D, Weist EM. The recommended critical component elements of an undergraduate major in public health. Public Health Rep. (2013) 128:421–424. doi: 10.1177/003335491312800516

10. Kayes AB, Kayes DC, Kolb DA. Experiential learning in teams. Simul Gam. (2005) 36:330–54. doi: 10.1177/1046878105279012

11. Michaelsen LK, Knight AB, Fink LD. (eds.). Team-Based Learning: A Transformative Use of Small Groups. Westport, CN: Greenwood Publishing Group (2002).

12. Yeatts KB. Active learning by design: an undergraduate introductory public health course. Front Public Health. (2014) 2:284. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00284

13. Collier KG. Peer-group learning in higher education: the development of higher order skills. Stud High Educ. (1980) 5:55–62.

14. Clark MC, Nguyen HT, Bray C, Levine RE. Team-based learning in an undergraduate nursing course. J Nurs Educ. (2008) 47:111–7. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20080301-02

15. Weasel LH, Finkel L. Deliberative pedagogy in a nonmajors biology course: active learning that promotes student engagement with science policy and research. J College Sci Teach. (2016) 45:38. doi: 10.2505/4/jcst16_045_04_38

16. Council on Education for Public Health. Accreditation Criteria Schools of Public Health Public Health Programs. Silver Spring, MD: Council on Education for Public Health (2016).

Keywords: public health education, bachelors of public health, undergraduate public health, undergraduate education, curriculum development, high-impact educational practices, career preparation, critical thinking

Citation: Nelson-Hurwitz DC and Buchthal OV (2019) Using Deliberative Pedagogy as a Tool for Critical Thinking and Career Preparation Among Undergraduate Public Health Students. Front. Public Health 7:37. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00037

Received: 07 November 2018; Accepted: 13 February 2019;

Published: 04 March 2019.

Edited by:

Andrew Harver, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, United StatesReviewed by:

Iffat Elbarazi, United Arab Emirates University, United Arab EmiratesEdward J. Trapido, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center New Orleans, United States

Copyright © 2019 Nelson-Hurwitz and Buchthal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Denise C. Nelson-Hurwitz, ZGVuaXNlbmVAaGF3YWlpLmVkdQ==

Denise C. Nelson-Hurwitz

Denise C. Nelson-Hurwitz Opal Vanessa Buchthal

Opal Vanessa Buchthal