- 1School of Social Sciences and Psychology, Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Department of Social Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

- 3Marcs Institute for Brain and Behaviour, Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Individuals with schizophrenia lead a poor quality of life, due to poor medical attention, homelessness, unemployment, financial constraints, lack of education, and poor social skills. Thus, a review of factors associated with the holistic management of schizophrenia is of paramount importance. The objective of this review is to improve the quality of life of individuals with schizophrenia, by addressing the factors related to the needs of the patients and present them in a unified manner. Although medications play a role, other factors that lead to a successful holistic management of schizophrenia include addressing the following: financial management, independent community living, independent living skill, relationship, friendship, entertainment, regular exercise for weight gained due to medication administration, co-morbid health issues, and day-care programmes for independent living. This review discusses the relationship between different symptoms and problems individuals with schizophrenia face (e.g., homelessness and unemployment), and how these can be managed using pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods. Thus, the target of this review is the carers of individuals with schizophrenia, public health managers, counselors, case workers, psychiatrists, and clinical psychologists aiming to enhance the quality of life of individuals with schizophrenia.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a brain disorder that impacts how a person acts, thinks, and perceives the world (1). It is characterized by symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and diminished emotional expression (2). The cause of these symptoms has been attributed to a dysregulation of dopaminergic signaling (3). Schizophrenia is considered amongst the topmost 10 common disorders in the world (4), as about one percentage of the general population suffers from schizophrenia (5). Schizophrenia generally appears in the late teens or early adulthood. However, it may also appear in middle ages (6). Generally, the early onset of schizophrenia is associated with severe positive and negative symptoms (7). Schizophrenia was found to be more severe and more common in men than in women (8, 9). Schizophrenia is a chronic disorder that can be managed effectively with due care and management principles, in addition to antipsychotics medications. However, the likelihood of recovery is the highest, when schizophrenia is diagnozed and treated at its onset (7). With medications and non-pharmacological therapy, many individuals with schizophrenia can live independently and have a satisfactory life, as we explain in the current review.

The long-term disability burden related to schizophrenia is far greater than any other mental disorders (10). The direct cost of schizophrenia amounts to 1–3% of national health care budget and is almost up to 20% of the direct expenses of all types of mental health costs in most of the developed nations (7). The indirect costs, such as independent accommodation, financial support, supported employment and training, are comparable or even more than the direct costs, such as medications and hospital fees.

Importantly, one aim for treating this disorder is not only decreasing some of the symptoms, but also enhancing the quality of life of the patients (by having successful jobs, relationships among others). There are various quantitative studies on managing different symptoms associated with schizophrenia such as a meta-analysis of population-based studies of premorbid intelligence and schizophrenia (11), a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study (12) and Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders (7). However, there is no study till today that has reviewed the factors associated with the holistic management of schizophrenia, which we address in this review.

Possible Causes of Schizophrenia

Here, we will first discuss the possible causes of schizophrenia symptoms and how knowing them can lead to a successful holistic management of the disorder. There is no single cause of schizophrenia though several factors have been identified (13). As mentioned above, the probability of developing schizophrenia was found to be larger in males than females (8, 9). It was also reported that the onset of schizophrenia occurs earlier in males than females (14). Several studies have shown that schizophrenia may be hereditary (15). It has been found that if one of the parents suffers from schizophrenia, the children have a 10% chance of having that condition. Individuals with schizophrenia may become sensitive to any family tension, which may cause relapse (16). Stressful events might precede the onset of schizophrenia, as these incidents may act as triggering events in at-risk individuals (17). Before any acute symptom of schizophrenia may become evident, individuals with schizophrenia may become anxious, irritable and unable to concentrate. These symptoms cause difficulties with work and relationships may deteriorate.

Alcohol and drug use, particularly cannabis and amphetamine, might initiate psychosis in people susceptible to schizophrenia (18–20). Substance abuse is strongly linked to the recurrence of schizophrenia symptoms (21). Individuals with schizophrenia use alcohol and other drugs more than the general population (22, 23), which is detrimental to their treatment. A large number of individuals with schizophrenia have been found to smoke which contributes to poor physical health and wellbeing (24). Methamphetamine, cannabis and cocaine are found to trigger psychotic states in individuals with schizophrenia (25). Many studies have shown that methamphetamine can induce psychosis and schizophrenia, as reported in Thailand (26) and Finland (27). Substance abuse is much higher in individuals with schizophrenia than in the general population (28). In one research study (29), it was found that the use of cannabis and amphetamines significantly contributes to the risk of psychosis. Individuals with schizophrenia are generally sensitive to the psychotogenic effects of stimulant drugs, which act by releasing dopamine (30). As the symptoms of schizophrenia encompass almost all aspects of life, a holistic paradigm involving all the factors in management of daily living is very important.

Methods

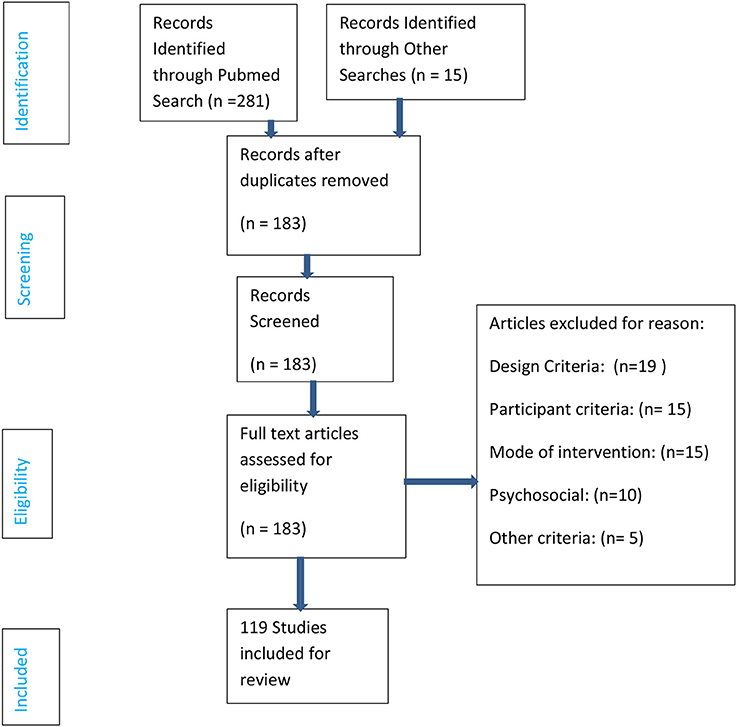

In our study, the eligibility criteria for selection of studies are their effectiveness in addressing issues related to holistic management of schizophrenia. The studies we considered are those which help manage symptoms of schizophrenia. Our search strategy included the following key words: schizophrenia, treatments, therapy, antipsychotic medication, management, quality of life, accommodation, employment and holistic. Many of these searches were conducted in combination. For example, we searched experimental studies that include all of these key words: schizophrenia, social relationship, and therapy (or treatment). We examined articles carefully to make sure the goal of the study is addressing the treatment of some symptoms of schizophrenia. Studies that did not address this topic were excluded. We repeated the same search using other aspects of schizophrenia, as we show in Table 1. Throughout this review, we provide assessment of the validity of the findings. We also provide interpretations of the results. We have studied only major antipsychotic medications We have searched studies in PubMed, PsychInfo, and in Google Scholar. A decision tree for our method of articles selection is given in Figure 1. Out of 296 articles initially identified for the proposed review. One hundred and thirteen were removed for duplication. Again out of 183 studies, 19 articles were excluded for non-relevant design criteria, 15 articles were excluded for participant criteria, 15 articles were excluded for mode of intervention, 10 articles were excluded for psychosocial reasons and 5 articles were excluded for other reason. Finally 119 studies were included for review.

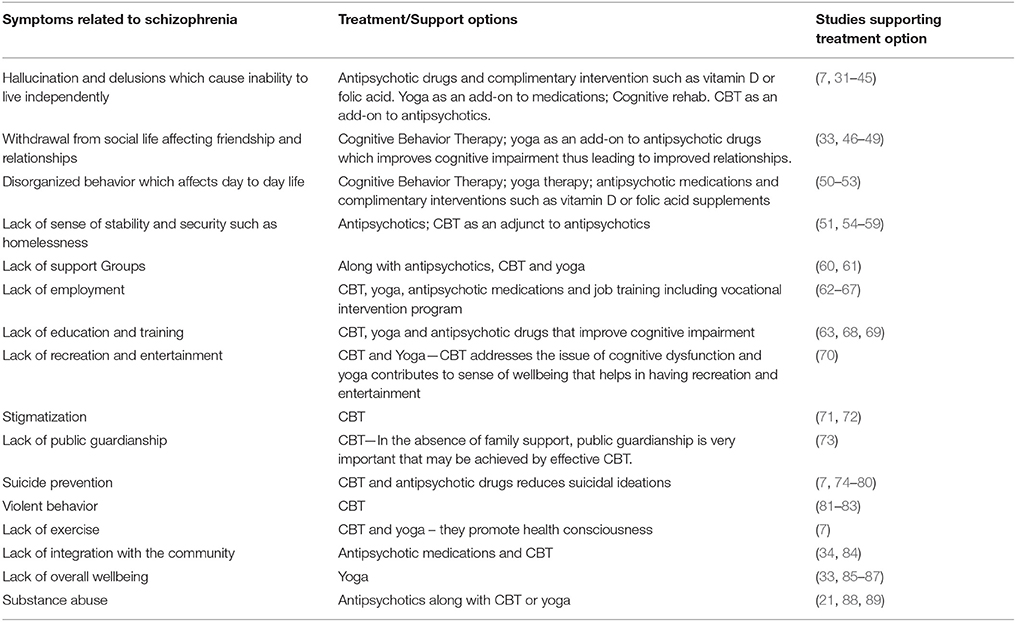

Table 1. The relationship between different symptoms and problems individuals with schizophrenia face, and how these can be managed using pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods.

Interventions for Schizophrenia

In this section, we will discuss the various existing therapies used for treating schizophrenia symptoms as well as problems the patients face, such as unemployment, lack of education, and lack of social relationships.

Pharmacological Intervention

It has been observed that full recovery from the symptoms of schizophrenia occurs in 6% of individuals with schizophrenia after a single episode of psychosis (90). In 39% of the patients, a deterioration of symptoms has been reported (90). Approximately, about one in seven individuals with schizophrenia achieve total recovery (91). Table 1 identifies the issues related to holistic management of schizophrenia and associated intervention options.

The initial treatment of schizophrenia often includes various antipsychotic medications. The targets of antipsychotic medications are generally the symptoms of schizophrenia but not the root causes of it, such as stress and substance abuse (see above). As mentioned in Table 1, most antipsychotic drugs ameliorate hallucinations and delusions, while some attempt to also address the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Antipsychotic medications are usually the only option for the treatment of schizophrenia. Most of antipsychotic treatments work by reducing the positive symptoms of schizophrenia through blocking dopamine receptors (7).

In one research study by Girgis et al. (92), 160 individuals with schizophrenia were randomized to clozapine or chlorpromazine treatment for up to 2 years. The adherence to clozapine was found to be higher than that of chlorpromazine. In another study conducted on 34 individuals with schizophrenia, it was found that there was no beneficial effect of clozapine over conventional antipsychotics (93). McEvoy et al. (94) found that a large percentage of individuals with schizophrenia discontinued treatment due to the inadequate efficacy of some antipsychotic drugs. An average daily dose of 523 and 600 mg/day of clozapine has been found to be effective in the treatment of positive and negative symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia (94). Sanz-Fuentenebro et al. (95) found that individuals with schizophrenia on clozapine continued their original treatment for a much longer period of time than patients on risperidone. Specifically, the retention rate for clozapine was 93 point 4% whereas the retention rate for risperidone was 82 point 8%. However, patients in the clozapine group normally have significant weight gain than those on risperidone (96).

In one study by Sahini et al. (97), a total of 63 patients were selected and randomly allocated to either clozapine or risperidone. The two groups were similar on sociodemographic variables including age, sex, education level, occupation, income, family type and marital status. The mean duration of illness was 19 point 39 months, in the clozapine group, and 18 point 63 months in the risperidone group. There was a significant reduction of positive symptoms in both drugs. It was found that both clozapine and risperidone equally reduced positive symptoms whereas clozapine was much superior compared to risperidone in reducing negative symptoms. Clozapine has been found to reduce suicidal ideation in individuals with schizophrenia (98); Along these lines, Hennen et al. (98) reported that with administration of clozapine in chronically psychotic patients has led to a reduced suicidal ideation. In fact, it was concluded that long-term treatment with clozapine resulted in a three-fold reduction of risk of suicidal behaviors. Further, patients on clozapine are often administered metformin (500 mg twice daily) to lose weight. Aripiprazole is sometime given along with clozapine to manage weight and improve metabolic parameters (99). In one study, Muscatello et al. (99), found that the administration of both aripiprazole and clozapine has led to a beneficial effect on the positive and general symptoms of individuals with schizophrenia, compared to clozapine alone.

Antipsychotic drugs also help ameliorate disoriented behavior in day-to-day life. They are also used to improve cognitive impairment, which in turn improves relationship and contributes to the attainment of education and employment. Antipsychotic drugs help improve disoriented behavior in day-to-day life. They are also used to improve relationships and enhance education (63, 68) and employment (62). Table 1 summarizes the role of pharmacological intervention in the holistic management of schizophrenia.

Complementary Intervention and Diet

Brown, et al. (100) found that the diets of schizophrenia patients contained more total fat and less fiber than the diets of a control group matched for age, gender, and education, although the intake of unsaturated fat was found to be similar in both groups. In another study (101), studied the dietary intake of 30 individuals with schizophrenia living in assisted-living facilities in Scotland as well as a control group matched for sex, age, smoking, and employment status. The majority of individuals with schizophrenia were overweight or obese, and saturated fat intake was higher than recommended in the diets for individuals with schizophrenia (102).

It was found that individuals with schizophrenia consumed less total fiber, retinol, carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, fruit, and vegetables than the control group (103).

McCreadie et al. (104) studied dietary habits of 102 individuals with schizophrenia with special emphasis on fruit and vegetable intake and smoking behavior. The study concluded that the patients (especially male patients) had poor dietary choices. Graham et al. (105) suggested that administering vitamin D to individuals with schizophrenia ameliorates their negative symptoms. In another study by Strassnig et al. (106), the dietary habits of a total of 146 adult community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia were studied. It was observed that the patients consumed a higher quantity of food that includes protein, carbohydrate, and fat than that of a control group Such habits can lead to cardiovascular diseases, type II diabetes, and systemic inflammation in individuals with schizophrenia (107). These diseases are related to a short lifespan in individuals with schizophrenia (108). In a research study by Joseph et al. (109), it has been suggested that high-fiber diets can improve the immune and cardiovascular system, thereby, preventing premature mortality in schizophrenia.

As mentioned in Table 1, the administration of folic acid supplements may help ameliorate positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Vitamin C, E, and B (including B12 and B6), were also found to be effective in managing schizophrenia symptoms (110). (The administration of vitamin D helps improve daily living (31), as mentioned in Table 1. Nonetheless, additional studies are required in order to investigate whether there is a relationship between complimentary medications and schizophrenia. Table 1 summarizes the role of complementary intervention in the holistic management of schizophrenia.

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is a therapeutic technique that helps modify undesirable mode of thinking, feeling and behavior. CBT involves practical self-help strategies, which are found to ameliorate positive symptoms in schizophrenia. CBT combines two kinds of therapies: “cognitive therapy” and “behavioral therapy.” The combination of these two techniques often enables the patient to have healthy thoughts and behaviors. Morrison (51) summarizes the use of CBT in individuals with schizophrenia to address the primary symptoms of illness as well as social impairments. Morrison (51) mentioned that many schizophrenia symptoms are resistant to pharmacological treatment and suggested CBT as an add-on to antipsychotics can be more effective than the administration of drugs alone. For example, several studies found that cognitive rehabilitation and CBT can ameliorate cognitive deficits and in turn positive symptoms (34, 35).

There are many techniques to alter thoughts and behavior using CBT. One research study described the key elements of CBT for schizophrenia (111), and concluded that various CBT techniques can be used effectively in schizophrenia. One of the techniques, known as cognitive restructuring, includes challenging the patient to come up with an evidence to prove that their beliefs are real. This technique assists the client to realize that they have delusions. This technique assists the patient to learn to identify and challenge negative thoughts, and modify the faulty thoughts with more realistic and positive ones. CBT was also found to be effective for managing homelessness. As CBT ameliorates cognitive impairment, it helps improve relationship and contributes positively to entertainment. Behavioral therapy aims to assist the patient to learn to modify their behavior. For example, they may rehearse conversational skills so that they can use these newly learned skills in social situations. CBT assists the patients in engaging in social circles which affects friendship and relationship as indicated in Table 1.

There have been validation studies of CBT in schizophrenia over the last 15 years. In schizophrenia, CBT is one of the most commonly used therapy in the UK (generally in addition to medications) (51). In fact CBT has been recommended as first-line treatment by the UK national health service (NHS) for individuals with schizophrenia. Similarly, the American Psychiatric Association recommended CBT for individuals with schizophrenia (112). Recently the US Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) has recommended CBT for patients who have persistent psychotic symptoms (112).

CBT was also found to be useful in reducing disorganized behavior which affects daily living in individuals with schizophrenia. In one research study by Wykes et al. (113) in the United States and United Kingdom, it has been found that CBT is more preferred than other behavioral therapies. This study show that CBT ameliorates positive symptoms, negative symptoms, mood and social anxiety. However, there was no effect on hopelessness. CBT sometimes includes the family of the patient in treatment session, which is why the patient and their carers usually welcome CBT. CBT brings the patient and their carers into a collaborative environment as a part of the treatment team and encourages them to participate actively in treatment. It has been found that hallucinations, delusions, negative symptoms and depression are also treated with CBT (38). CBT involves doing a homework which allows the patient and their carer to alleviate the distressing symptoms of schizophrenia. CBT encourages taking medications regularly and integrating with the community (51). CBT has also been found to have enhanced effect when combined with antipsychotic medication (114), as compared to the administration of medications alone.

In one study (38), 90 patients were treated using CBT for over 9 months. The therapy resulted in significant reductions in positive and negative symptoms and depression. After a 9-month follow-up evaluation, patients receiving CBT continued to improve, unlike those who did not receive CBT. In order to apply CBT to schizophrenia, a deep understanding of the patient's symptoms should be developed first (115). Then, the issues related to positive and negative symptoms need to be addressed. CBT also helps reduce suicidal ideation and violent behavior as well as encourages individuals with schizophrenia to regularly exercise, integrate with the community, avoid stigmatization, adopt public trusteeship and guardianship and avoid substance abuse. Table 1 identifies the issues related to holistic management of schizophrenia and associated CBT intervention options.

Yoga Therapy

Yoga therapy can also manage schizophrenia symptoms, often in combination with pharmacological medications (116). Pharmacological intervention alone might not produce all the desirable effects in managing schizophrenia symptoms, especially negative symptoms (60). Yoga, as an add-on to antipsychotic medications, helps treat both positive and negative symptoms, more than medications alone. Furthermore, pharmacological interventions often produce obesity in schizophrenia (60). Yoga therapy has been found to help reduce weight gain due to the administration of antipsychotic medications. Pharmacological interventions might cause endocrinological and menstrual dysfunction which may be positively treated by yoga therapy (60). In a research study by Gangadhar et al. (60), two groups of patients on antipsychotic medications were examined. In one group, yoga therapy was administered. In the other group, a set of physical exercises was applied. Both groups were trained for 1 month (at least 12 sessions). The yoga group showed better negative symptoms scores than the other group. Similarly, yoga therapy resulted in better effects on social dysfunction than the other group. Along these lines, Vancampfort et al. (117) found that practicing yoga reduces psychiatric symptoms and improves the mental and physical quality of life, and also reduces metabolic risk.

The most probable explanation of the effectiveness of yoga therapy is the production of oxytocin in the body (60). Oxytocin is a hormone which contributes to wellbeing. In one research study, 40 patients were administered oxytocin along with antipsychotic medications (118). It was found that both negative and positive symptoms improved in those patients. The results of yoga therapy are manifolds. Yoga therapy can lead to a reduction in psychotic symptoms and depression, improvement in cognition, and an increase in quality of life. Table 1 identifies the issues related to holistic management of schizophrenia and associated yoga intervention options.

Discussion

We have described and explained various factors to manage schizophrenia symptoms in a holistic manner. Although there are a multitude of research studies on pharmacological intervention, there are only few studies encompassing all the factors associated with holistic management of schizophrenia. Future work should attempt to provide a framework for holistic management of schizophrenia. Table 1 identifies the issues related to the holistic management of schizophrenia and intervention options for symptoms and issues most individuals with schizophrenia often face.

Based on our review (see Table 1), we found that different symptoms of schizophrenia (e.g., psychiatric symptoms, homelessness, unemployment, financial constraints, lack of education, poor relationship, among others) can be adequately addressed and managed using different methods (e.g., antipsychotics, CBT, yoga, among others). However, there are several issues like recreation and entertainment, public guardianship, and training for financial management that have not been adequately addressed in prior studies. Our review study provides a holistic account for how different symptoms in schizophrenia can be effectively managed.

Although most treatment studies focus on ameliorating positive and negative symptoms, other symptoms, such as homelessness and lack of education equally impact the quality of life in individuals with schizophrenia. Thus, targeting these symptoms is of paramount importance. By doing so, we will be able to provide an individualized treatment for schizophrenia as well as increase the patients' participation in society. Galletly et al. (7) provides a set of recommendations for the clinical management of schizophrenia. They adopt a somewhat holistic view of treating schizophrenia symptoms and problems the patients face such as unemployment. This guideline emphasizes early intervention, physical health, psychosocial treatments, cultural considerations and improving vocational outcomes as well as collaborative management and evidence-based treatment.

As shown in Table 1, even though different treatments can manage different schizophrenia symptoms, future research should investigate whether the combination of these treatments is effective, as it is possible that combining several treatments may not lead to the same effects of each therapeutic method administered alone. For example, although 85% of individuals with schizophrenia are on government support (7), they need to manage their finances. Group homes often provide financial management. However, in order to live independently, finance management is a problem for many patients. Independent living and integration with the community are areas which need further attention and work (84). Individuals with schizophrenia are often unable to run their daily chores. They need to be trained to prepare a meal, wash clothes, and administer medications. Relationship is a problem for individuals with schizophrenia. As they are unable to participate in a conversation fluently, it is difficult for many patients to form a strong relationship. Their relationship, if ever successful, often becomes week over time and patients gradually become isolated. Since individuals with schizophrenia become withdrawn from most social activities, their friends and peers become disinterested and finally desert them. Individuals with schizophrenia often depend on close family support to survive. Table 1 describes ways to ameliorate such problems, which can help improve the quality of life of the patients. Entertainment and recreation are important element in everyday life. Individuals with schizophrenia have a fair bit of time in their hand as they are often not engaged in full-time job or any such activities. They get bored, and they need recreation as well, which is a key part of enhancing their quality of life. Hobbies and other recreational activities will help them alleviate boredom.

In our proposed framework for holistic management of schizophrenia, in addition to conventional pharmacological therapy, it is important to include other non-pharmacological interventions to assist the patients obtain financial management, independent community living, independent living skill, insurance needs, public trustee and guardianship, relationship, friendship, and entertainment (71) as well as manage alcohol and other drug issues, domestic violence, and any other health problems issues.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Coyle JT. Schizophrenia: basic and clinical. Adv Neurobiol. (2017) 15:255–80. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-57193-5_9.

2. Shenton EM, Kikinis R, Jolesz AF, Pollak DS, Wible G, et al. Abnormalities of the left temporal lobe and thought disorder in schizophrenia — a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study. N Engl J Med. (1992) 327:604–12.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing (2013).

4. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. (2006) 3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442

5. Simeone JC, Ward AJ, Rotella P, Collins J, Windisch R. An evaluation of variation in published estimates of schizophrenia prevalence from 1990 - 2013: a systematic literature review. BMC Psychiatry (2015) 15:193. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0578-7

6. Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C. Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center AeSOP study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry (2006) 63:250–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.250

7. Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F, Humberstone V, Jablensky A, Killackey A, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2016) 50:410–72. doi: 10.1177/0004867416641195

8. Aleman A, Kahn RS, Selten JP. Sex differences in the risk of schizophrenia: evidence from meta-analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry (2003) 60:565–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.565

9. McGrath JL, Saha S, Chant D, Welham J. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol. Rev. (2008) 30:67–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn001

10. Neil AL, Carr VJ, Mihalopoulos C. What difference a decade? The costs of psychosis in Australia in 2000 and 2010: comparative results from the first and second Australian national surveys of psychosis. Austr. N. Z. J. Psychiatry (2014) 48:237–48. doi: 10.1177/0004867413508453

11. Khandakera MG, Barnetta H, Whitec RI, Jonesa BP. A quantitative meta-analysis of population-based studies of premorbid intelligence and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2011) 132:220–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.017

12. Wible GC, Anderson J, Shenton EM, Kricun A, Hirayasu Y, Tanaka S, et al. Prefrontal cortex, negative symptoms, and schizophrenia: an MRI study. Psychiatry Res. (2001) 108:65–78.

13. Park S, Lee M, Furnham A, Jeon M, Ko YM. (2017). Lay beliefs about the causes and cures of schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 63:518–24. doi: 10.1177/0020764017717283

14. Cornblatt AB, Lenzenweger MF, Dworkin HR, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L. Positive and negative schizophrenic symptoms, attention, and information processing. J. Med. Health Schizophr. Bull. (1985) 11:397–408.

15. Matsumoto M, Walton NM, Yamada H, Kondo Y, Marek GJ, Tajinda K. The impact of genetics on future drug discovery in schizophrenia. Expert Opin Drug Discov. (2017) 18:1–14. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2017.1324419

16. Buchanan WR. Persistent negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. (2007) 33:1013–22. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl057

17. Nasrallah H, Hwang M. Psychiatric and physical comorbidity in schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Clin. (2009) 32:719–914. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.10.002

18. Pogue-Geile FM, Harrow M. Negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia and depression: a followup, oxford journals, medicine and health. Schizophr Bull. (1984) 10:371–87.

19. Huabing L, Qiong L, Enhua X, Qiuyun L, Zhong H, Xilong M. Methamphetamine enhances the development of schizophrenia in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry (2014) 59:107–13. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900206

20. Medhus S, Rognli EB, Gossop M, Holm B, Mørland J, Bramness JG. Amphetamine-induced psychosis: transition to schizophrenia and mortality in a small prospective sample. Am. J. Addict. (2015) 24:586–9. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12274

21. Moore E, Mancuso SG, Slade T. The impact of alcohol and illicit drugs on people with psychosis: the second Australian National Survey of Psychosis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry (2012) 46:864–78. doi: 10.1177/0004867412443900

22. Chiappelli J, Chen S, Hackman A, Elliot Hong L. Evidence for differential opioid use disorder in schizophrenia in an addiction treatment population. Schizophr Res. (2017) 194:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.05.004

23. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, et al. (1990). Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA (1990) 264:2511–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450190043026

24. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry (2015) 72:1172–81. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1737

25. Moustafa AA, Salama M, Peak R, Tindle R, Salem A, Keri S, et al. (2017). Interactions between cannabis and schizophrenia in humans and rodents. Rev Neurosci. 28:811–23. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2016-0083

26. Kittirattanapaiboon P, Mahatnirunkul S, Boonchareon H, Thummawomg P, Dumrongchai U, Chutha W. Long-term outcomes in methamphetamine psychosispatients after first hospitalisation. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2010) 29:456–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00196.x

27. Niemi-Pynttäri JA, Sund R, Putkonen H, Vorma H, Wahlbeck K, Pirkola SP. (2013). Substance-induced psychoses converting into schizophrenia: a register-based study of 18,478 Finnish inpatient cases. J Clin Psychiatry (2013) 74:e94-9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07822

28. Sara GE, Large MM, Matheson SL. Stimulant use disorders in people with psychosis: a meta-analysis of rate and factors affecting variation. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry (2015) 49:106–17. doi: 10.1177/0004867414561526

29. Barkus E, Murray RM. Substance use in adolescence and psychosis: clarifying the relationship. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2010) 6:365–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131220.

30. Seeman MV, Seeman P. Is schizophrenia a dopamine supersensitivity psychotic reaction? Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry (2014) 48:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.10.003

31. Cieslak K, Feingold J, Antonius D, Walsh-Messinger J, Dracxler R, Rosedale M, et al. (2014). Low Vitamin D levels predict clinical features of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 159:543–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.08.031

32. Mehta UM, Keshavan MS, Gangadhar BN. Bridging the schism of schizophrenia through yoga-Review of putative mechanisms. Int Rev Psychiatry (2016) 28:254–64. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2016.1176905

33. Varambally S, Gangadhar BN, Thirthalli J, Jagannathan A, Kumar S, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of add-on yogasana intervention in stabilized outpatient schizophrenia: randomized controlled comparison with exercise and waitlist. Indian J Psychiatry (2012) 54:227–32. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.102414

34. Eack SM, Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Keshavan MS. Effects of cognitive enhancement therapy on employment outcomes in early schizophrenia: results from a two-year randomized trial. Res Soc Work Pract. (2011) 21:32–42. doi: 10.1177/1049731509355812

35. Subramaniam K, Luks TL, Fisher M, Simpson GV, Nagarajan S, Vinogradov S. Computerized cognitive training restores neural activity within the reality monitoring network in schizophrenia. Neuron (2012) 73:842–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.024

36. Haddock G, Tarrier N, Morrison AP, Hopkins R, Drake R, Lewis S. A pilot study evaluating the effectiveness of individual inpatient cognitive-behavioural therapy in early psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (1999) 34:254–8. doi: 10.1007/s001270050141

37. Kuipers E, Garety P, Fowler D, Dunn G, Bebbington P, Freeman D, et al. London-East Anglia randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for psychosis. I: effects of the treatment phase. Br J Psychiatry (1997) 171:319–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.4.319

38. Sensky T, Turkington D, Kingdon D, Scott JL, Scott J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive–behavioural therapy for persistent symptoms in schizophrenia resistant to medication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry (2000) 57:165–72. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.026

39. Beck AT. Successful outpatient psychotherapy of a chronic schizophrenic with a delusion based on borrowed guilt. Psychiatry (1952) 15:305–12. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1952.11022883

40. Drury V, Birchwood M, Cochrane R, Macmillan F. Cognitive therapy and recovery from acute psychosis: a controlled trial. I. Impact on psychotic symptoms. Br J Psychiatry (1996) 169:593–601. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.5.593

41. Amminger GP, Schafer RM, Schlogelhofer M, Klier MC, McGorry DP. Longer term outcome in the prevention of psychotic disorders by Vienna omega 3 study. Nat Commun. (2015) 2015:7934. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8934

42. Hill SK, Reilly JL, Keefe RS, Gold JM, Bishop JR, Gershon ES, et al. Neuropsychological impairments in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder: findings from the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP) study. Am. J. Psychiatry (2013) 170:1275–84. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12101298

43. Strauss J. Reconceptualizing schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. (2013) 40, S97–100. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt156

44. Thomas D. Quantitative studies of schizophrenic behaviour. Behav Processes (1976) 1:347–72. doi: 10.1016/0376-6357(76)90016-4

45. Waghorn G, Saha S, Harvey C, Morgan VA, Waterrus A, Bush R, et al. ‘Earning and learning' in those with psychotic disorders: the second Australian national survey of psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2012) 46:774–85. doi: 10.1177/0004867412452015

46. Turkington D, Kingdon D. Cognitive–behavioural techniques for general psychiatrists in the management of patients with psychoses. Bri J Psychiatry (2000) 177:101–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.2.101

47. Lewis S, Tarrier N, Haddock G. (2002). Randomised controlled trial of cognitive–behavioural therapy in early schizophrenia: acute-phase outcomes. Br J Psychiatry 181:s91–97. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.43.s91

48. Iyer SN, Mangala R, Anitha J, Thara R, Malla AK. An examination of patient-identified goals for treatment in a first-episode programme in Chennai, India. Early Interv Psychiatry (2011) 5:360–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00289.x

49. Ramsay CE, Broussard B, Goulding SM, Cristofaro S, Hall D, Kaslow NJ, et al. Life and treatment goals of individuals hospitalized for first-episode nonaffective psychosis. Psychiatry Res. (2011) 189:344–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.039

50. Teesson ML, Buhrich N. Psychiatric disorders in homeless men and women in inner Sydney. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2004) 38:162–8. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01322.x

51. Morrison KA. Cognitive behavior therapy for people with schizophrenia. Psychiatry (Edgmont). (2009) 6:32–33.

52. Cormac I, Jones C, Campbell C. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Schizophrenia (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Library (2002). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000524

53. Dickerson FB, Lehman AF. Evidence-based psychotherapy for schizophrenia: 2011 update. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2011) 199:520–6. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318225ee78

54. Jaeger M, Briner D, Kawohl W, Seifritz E, Baumgartner-Nietlishach G. Psychosocial functioning of individuals with schizophrenia in community housing facilities and the psychiatric hospital in Zurich. Psychiatry Res. (2015) 230:413–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.09.029

55. Teesson M, Hall W, Lynskey M, Degenhardt L. Alcohol- and drug-usedisorders in Australia: Implications of the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2000) 34:206–13. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00715.x

56. Folsom D, Jeste DV. Schizophrenia in homeless persons: a systematic review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2002) 105:404–13. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02209.x

57. Coldwell CM, Bender WS. The effectiveness of assertive community treatment for homeless populations with severe mental illness: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry (2007) 164:393–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.393

58. Girard V, Tinland A, Bonin JP, Olive F, Poule J, Lancon C, et al. Relevance of a subjective quality of life questionnaire for long-term homeless persons with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:72. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1227-0

59. Nelson G, Aubry T, Lafrance A. A review of the literature on the effectiveness of housing and support, assertive community treatment, and intensive case management interventions for persons with mental illness who have been homeless. Am J Orthopsychiatry (2007) 77:350–61. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.3.350

60. Gangadhar N, Varambally S. Yoga therapy for schizophrenia. Int J Yoga. (2012) 5:85–91. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.98212

61. Fontanella CA, Guada J, Phillips G, Ranbom L, Fortney JC. Individual and contextual-level factors associated with continuity of care for adults with schizophrenia. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2014) 41:572–87. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0500-x

62. Kinoshita Y, Furukawa TA, Kinoshita K, Honyashiki M, Omori IM, Marshall M, et al. Supported employment for adults with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013) 9:CD008297. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008297.pub2

63. Lysaker PH, Davis LW, Bryson GJ, Bell MD. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on work outcomes in vocational rehabilitation for participants with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizo Res. (2009) 107:186–91. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.10.018

64. Killackey EJ, Jackson HJ, Gleeson J, Hickie IB, McGorry PD. Exciting career opportunity beckons! Early intervention and vocational rehabilitation in first-episode psychosis: employing cautious optimism. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2006) 40:951–62. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01918.x

65. Major BS, Hinton MF, Flint A, Chalmers-Brown A, McLoughlin K, Johnson S. Evidence of the effectiveness of a specialist vocational intervention following first episode psychosis: a naturalistic prospective cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2010) 45:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0034-4

66. Rinaldi M, McNeil K, Firn M, Koletsi M, Perkins R, Singh SP. What are the benefits of evidence based supported employment for patients with first-episode psychosis? Psychiatric Bull. (2004) 28:281–4. doi: 10.1192/pb.28.8.281

67. Bond GR, Drake ER, Becker D. Generalizability of the individual placement and support (IPS) model of supported employment outside the US. World Psychiatry (2012) 11:32–39.

68. Drake ER, Bond RG, Becker RD. Individual Placement and Support: An Evidence-Based Approach to Supported Employment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2012).

69. Vargas G, Strassnig M, Sabbag S, Gould F, Durand D, Stone L, et al. The course of vocational functioning in patients with schizophrenia: re-examining social drift. Schizophr Res Cogn. (2014) 1:e41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2014.01.001

70. Beck AT, Rector NA. Cognitive approaches to schizophrenia: theory and therapy. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. (2005) 1:577–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144205

71. Koschorke M, Padmavati R, Kumar S, Cohen A, Weiss HA, Chatterjee S, et al. Experiences of stigma and discrimination faced by family caregivers of people with schizophrenia in India. Soc Sci Med. (2017) 178:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.061

72. Switaj P, Grygiel P, Chrostek A, Nowak I, Wciórka J, Anczewska M. The relationship between internalized stigma and quality of life among people with mental illness: are self-esteem and sense of coherence sequential mediators? Qual Life Res. (2017) 26:2471–8. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1596-3

73. Harvey PD, Stone L, Lowenstein D, Czaja SJ, Heaton RK, Twamley EW, et al. 9 The convergence between self-reports and observer ratings of financial skills and direct assessment of financial capabilities in patients with schizophrenia: more detail is not always better. Schizophr Res. (2013) 147:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.018

74. Hor K, Taylor M. Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol. (2010) 24:81–90. doi: 10.1177/1359786810385490

76. Bateman K, Hansen L, Turkington D, Kingdon D. Cognitive behavioral therapy reduces suicidal ideation in schizophrenia: results from a randomized controlled trial. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2007) 37:284–90. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.284

77. Challis S, Neilssen O, Harris A, Large M. Systematic meta-analysis of the risk factors for deliberate self-harm before and after treatment for first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. (2013) 127:442–54. doi: 10.1111/acps.12074

78. Palmer BA, Pankratz S, Bostwick MJ. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry (2005) 62:247–53. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.247

79. Preti A, Meneghelli A, Pisano A, Cocchi A, Programma T. Risk of suicide and suicidal ideation in psychosis: results from an Italian multi-modal pilot program on early intervention in psychosis. Schizophr Res. (2009) 113:145–50. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.007

80. Barak Y, Baruch Y, Achiron A, Aizenberg D. Suicide attempts of schizophrenia patients: a case-controlled study in tertiary care. J Psychiatr Res. (2008) 42:822–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.09.002

81. Large M, Smith G, Nielssen O. The relationship between the rate of homicide by those with schizophrenia and the overall homicide rate: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Res. (2009) 112:123–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.04.004

82. Erb M, Hodgins S, Freese R, Muller-Isberner R, Jockel D. Homicide and schizophrenia: maybe treatment does have a preventive effect. Crim Behav Ment Health (2001) 11:6–26. doi: 10.1002/cbm.366

83. Johnson M. National patient safety report. J Adult Protect. (2006) 8:36–38. doi: 10.1108/14668203200600020

84. Eack SM, Mesholam-Gately RI, Greenwald DP. Negative symptom improvement during cognitive rehabilitation: results from a 2-year trial of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy. Psychiatry Res. (2013) 209:21–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.020

85. Manjunath RB. Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences; 2009. Efficacy of Yoga Therapy as an Add-on Treatment for In-patients and Out-Patients with Functional Psychotic Disorder. Dissertation (2009).

86. Nagendra HR, Telles S, Naveen KV. (2000). An Integrated Approach of Yoga Therapy for the Management of Schizophrenia. Final Report submitted to Department of ISM and H, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India New Delhi.

87. Walsh R, Roche L. Precipitation of acute psychotic episodes by intensive meditation in individuals with a history of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry (1979) 136:1085–6.

88. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Brunette MF. Management of persons with co-occuring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: program implications. World Psychiatry (2007) 6:131–136.

89. Cather C, Pachas GN, Cieslak KM, Evins AE. Achieving smoking cessation in individuals with schizophrenia: special considerations. CNS Drugs. (2017) 36:471–81. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0438-8

90. Morgan VA, McGrath JJ, Jablensky A, Badcock JC, Waterreus A, Bush R, et al. Psychosis prevalence and physical, metabolic and cognitive co-morbidity: data from the second Australian national survey of psychosis. Psychol Med. (2014) 44:2163–76. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002973

91. Jaaskelainen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, John J, McGrath JJ, Saha S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2013) 39:1296–306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs130

92. Girgis RR, Phillips MR, Li X, Li K, Jiang H, Wu C, et al. Clozapine v. chlorpromazine in treatment-naive, first-episode schizophrenia: 9-year outcomes of a randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry (2011) 199:281–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081471

93. Woerner MG, Robinson DG, Alvir JM, Sheitman BB, Lieberman JA, Kane JM. Clozapine as a first treatment for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry (2003) 160:1514–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1514

94. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, Davis SM, Meltzer HY, Rosenheck RA, et al. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine quetiapine and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry (2006) 163:600–10. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.600

95. Sanz-Fuentenebro J, Taboada D, Palomo T, Aragües M, Ovejero S, Del Alamo C, et al. Randomized trial of clozapine vs. risperidone in treatment-naïve first-episode schizophrenia:results after one year. Schizophr Res. (2013) 149:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.003

96. Taylor DM, McAskill R. Atypical antipsychotics and weight gain – a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2000) 101:416–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101006416.x

97. Sahni S, Chavan BS, Sidana A, Priyanka K, Gurjit K. Comparative study of clozapine versus risperidone in treatment-naive, first-episode schizophrenia: a pilot study. Indian J Med Res. (2016) 144:697–703. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_279_15

98. Hennen J, Baldessarini RJ. Suicidal risk during treatment with clozapine: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. (2005) 73:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.05.015

99. Muscatello MRL, Bruno A, Pandolfo G, Micò U, Scimeca G, Di Nardo F, et al. (2011). Effect of aripiprazole augmentation of clozapine in schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. (2011) 127:93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.12.011

100. Brown S, Birtwistle J, Roe L, Thompson C. The unhealthy lifestyle of people with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. (1999) 29:697–701. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798008186

101. McCreadie R, MacDonald E, Blackock C, Tilak-Singh D, Wiles D, Halliday J, et al. Dietary intake of schizophrenic patients in Nithsdale, Scotland: case-control study. BMJ. (1998) 317:784–785. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7161.784

102. Gothelf D, Falk B, Singer P, Kairi M, Phillip M, Zigel L, et al. Weight gain associated with increased food intake and low habitual activity levels in male adolescent schizophrenic inpatients treated with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry. (2002) 159:1055–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1055

103. Kalaydjian AE, Eaton W, Cascella N, Fasano A. The gluten connection: the association between schizophrenia and celiac disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2006) 113:82–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00687.x

104. McCreadie RG. Diet, smoking, and cardiovascular risk in people with schizophrenia: descriptive study. Br J Psychiatry (2003) 183:534–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.6.534

105. Graham KA, Keefe RS, Lieberman JA, Calikoglu AS, Lansing KM, Perkins DO. Relationship of low vitamin D status with positive, negative and cognitive symptom domains in people with first-episode schizophrenia. Early Interv Psychiatry (2015) 9:397–405. doi: 10.1111/eip.12122

106. Strassnig M, Singh BJ, Ganguli R. Dietary intake of patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry (Edgmont). (2005) 2:31–5. doi: 10.1080/10401230600614538

107. Kraft DB, Westman CE. Schizophrenia, gluten, and low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diets: a case report and review of the literature. Nutr Metabol. (2009) 6:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-6-10

108. Ran MS, Chen EY, Conwell Y, Chan CL, Yip PS, Xiang MZ, et al. Mortality in people with schizophrenia in rural China: 10-year cohort study. Br J Psychiatry (2007) 190:237–42. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025155

109. Joseph J, Depp C, Shih PB, Cadenhead KS, Schmid-Schönbein G. Modified mediterranean diet for enrichment of short chain fatty acids: potential adjunctive therapeutic to target immune and metabolic dysfunction in Schizophrenia? Front Neurosci. (2017) 11:155. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00155

110. Brown HE, Roffman J. Vitamin supplementation in the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. (2014) 28:611–22. doi: 10.1007/s40263-014-0172-4

111. Tai S, Turkington D. The evolution of cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: current practice and recent developments. Schizo Bull. (2009) 35:865–73. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp080

112. Jauhar S, McKenna PJ, Radua J, Fung E, Salvador R, Laws RK. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the symptoms of schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis with examination of potential bias. Br J Psychiatry (2014) 204:20–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116285

113. Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, Tarrier N. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: effect sizes clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophr Bull. (2008) 34:523–37. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm114

114. Pinto A, La Pia S, Menella R. Cognitive behavioural therapy and clozapine for patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. (1999) 50:901–4. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.7.901

115. Turkington D, Kingdon D, Weiden PJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. (2006) 163:365–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.365

116. Jha A. Yoga therapy for schizophrenia. Acta Psychiat Scand. (2008) 117:397–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01151.x

117. Vancampfort DL, Probst M, Helvik Skjaerven L, Catalán-Matamoros D, Lundvik-Gyllensten A, Gómez-Conesa A, et al. Systematic review of the benefits of physical therapy within a multidisciplinary care approach for people with schizophrenia. Phys Ther. (2012) 92:1–13. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20110218

Keywords: schizophrenia, holistic management, individualized treatment, antipsychotics, quality of life

Citation: Ganguly P, Soliman A and Moustafa AA (2018) Holistic Management of Schizophrenia Symptoms Using Pharmacological and Non-pharmacological Treatment. Front. Public Health 6:166. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00166

Received: 27 October 2017; Accepted: 17 May 2018;

Published: 07 June 2018.

Edited by:

Frederick Robert Carrick, Bedfordshire Centre for Mental Health Research in Association with the University of Cambridge (BCMHR-CU), United KingdomReviewed by:

Deana Davalos, Colorado State University, United StatesAdonis Sfera, Loma Linda University, United States

Copyright © 2018 Ganguly, Soliman and Moustafa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pronab Ganguly, cHJvbmFiZ2FuZ3VseUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Pronab Ganguly

Pronab Ganguly Abdrabo Soliman2

Abdrabo Soliman2 Ahmed A. Moustafa

Ahmed A. Moustafa