94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Public Health , 30 April 2018

Sec. Public Health Policy

Volume 6 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00107

Karen McPhail-Bell1,2*

Karen McPhail-Bell1,2* Veronica Matthews2

Veronica Matthews2 Roxanne Bainbridge3

Roxanne Bainbridge3 Michelle Louise Redman-MacLaren3,4

Michelle Louise Redman-MacLaren3,4 Deborah Askew5,6

Deborah Askew5,6 Shanthi Ramanathan7

Shanthi Ramanathan7 Jodie Bailie2

Jodie Bailie2 Ross Bailie2

Ross Bailie2

On Behalf of the Centre RCS Lead Group

On Behalf of the Centre RCS Lead Group

In Australia, Indigenous people experience poor access to health care and the highest rates of morbidity and mortality of any population group. Despite modest improvements in recent years, concerns remains that Indigenous people have been over-researched without corresponding health improvements. Embedding Indigenous leadership, participation, and priorities in health research is an essential strategy for meaningful change for Indigenous people. To centralize Indigenous perspectives in research processes, a transformative shift away from traditional approaches that have benefited researchers and non-Indigenous agendas is required. This shift must involve concomitant strengthening of the research capacity of Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers and research translators—all must teach and all must learn. However, there is limited evidence about how to strengthen systems and stakeholder capacity to participate in and lead continuous quality improvement (CQI) research in Indigenous primary health care, to the benefit of Indigenous people. This paper describes the collaborative development of, and principles underpinning, a research capacity strengthening (RCS) model in a national Indigenous primary health care CQI research network. The development process identified the need to address power imbalances, cultural contexts, relationships, systems requirements and existing knowledge, skills, and experience of all parties. Taking a strengths-based perspective, we harnessed existing knowledge, skills and experiences; hence our emphasis on capacity “strengthening”. New insights are provided into the complex processes of RCS within the context of CQI in Indigenous primary health care.

Globally, Indigenous peoples experience significant health disparities (1). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (hereafter respectfully referred to as “Indigenous”) Australians experience disparities in health status and poor access to/quality of care when compared to non-Indigenous Australians (2, 3). Improving the quality of primary health care provided to Indigenous Australians is one necessary step to redress these health disparities (4). Continuous quality improvement (CQI) methods are key to improving primary health-care service delivery, with an emerging evidence base demonstrating promising results in Indigenous health (5, 6).

Systems and stakeholder capacity to participate in and lead CQI research in Indigenous primary health care is required to generate benefits (7, 8). Yet the processes, skills, knowledge, and system supports necessary to undertake CQI research in this setting have been largely undefined and fragmented. This raises the question of what is an appropriate model of CQI research capacity strengthening (RCS) in Indigenous primary health care that is of value and benefit to Indigenous Australians?

The Centre for Research Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement for Indigenous primary healthcare services (the Centre) has collaboratively developed a CQI-RCS model. This model draws on capacity strengthening (9) and quality improvement capacity building evidence (10), to theorize strategies to strengthen capacity for CQI research in Indigenous primary health care. Reflecting extant capacities, loci of power, cultural strengths and relationships, the model aims to strengthen existing capacity rather than assume a need to “build” from a zero base (11); as reflected in the Centre’s “all teach, all learn” approach to CQI-RCS. This paper presents the model’s development and four principles to inform approaches to Indigenous health RCS.

Continuous quality improvement refers to “a system of regular reflection and refinement to improve processes and outcomes that will provide quality health care” (12). Through CQI research, primary health-care quality improvement efforts have been accelerated and strengthened at multiple levels and contexts (13). Clinical performance assessment and improvements have been achieved across a range of services (14, 15) and structured health service and systems assessment facilitated to support best practice (16, 17). CQI research continues to play an important role in testing the acceptability of CQI approaches and their impact on Indigenous primary health care (5, 18).

In Australia, CQI methods have attracted significant resourcing and policy focus, including for Indigenous primary health care. The National CQI Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care and the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation both prioritise CQI-RCS in the Indigenous community-controlled sector to support co-creation and translation of CQI knowledge (19, 20). The National Health and Medical Research Council funded the Centre for 2015–2019 to improve Indigenous health outcomes by accelerating and strengthening system-wide CQI efforts. The Centre brings together leaders and practitioners of CQI in Indigenous primary health care from community-controlled and government health services, universities, research centers, and policy organizations across Australia (21).

The capacity to perform research is an essential component of a well-functioning public health system (22). A variety of research capacities are required to lead and/or participate in health research aimed at individual, organizational, and systems-level change (23). RCS occurs through research processes and systems, including but going beyond individual training when health equity is the goal (11). Health RCS involves skills- and confidence-building through training, mentorship triads, and apprenticeship-style learning; partnerships and collaborations; dissemination and knowledge translation; empowerment, local governances (ownership) and leadership; as well as infrastructure and resources (24). A literature review by Kahwa and colleagues defined health RCS as:

An ongoing and iterative process of empowering individuals, interdisciplinary teams, networks, institutions and societies to identify health and health-related challenges; to develop, conduct and manage scientifically appropriate and rigorous research to address those challenges in a dynamic and sustainable manner; and to share, apply and mobilize research knowledge generated with the active participation of engaged stakeholders and decision-makers (25).

This definition underscores the need for a systems-orientation and the importance of empowerment and capacity in research production and utilization. The Kahwa definition does not detail specific capacities to be strengthened through RCS. The definition does, however, identify a framework in which RCS occurs within and across five structural levels: individual, team, health services, network and support, and national research infrastructure/bodies (25). Eight integrated dimensions for health RCS design, coordination and evaluation span the five levels (25):

1. building skills and confidence

2. research applicability

3. developing partnerships and linkages

4. appropriate dissemination and knowledge translation to maximize impact

5. including elements of continuity and sustainability

6. making investments in infrastructure to enhance research capacity building

7. leadership

8. empowerment

The backdrop to Indigenous health RCS is a history of imposed research that generally has not benefited Indigenous Australians, reflecting the exploitative nature of colonization in Australia (7, 26). We acknowledge there are positive examples of Indigenous health research. Yet historically research was about examining and documenting the “exotic other” and conducted to protect non-Indigenous populations from disease (27). More recently, it has often served the priorities of non-Indigenous researchers and perpetuated a deficit-narrative that justifies mainstream intervention in Indigenous people’s lives “for their own good” (28). Such an approach undermines Indigenous control—an important determinant of population health and wellbeing (29)—while overlooking the value and strengths of Indigenous knowledge, experience, and perspectives (30).

Indigenous health RCS is important for self-determination of health research and sustainable outcomes for Indigenous people (31, 32). Research led by Indigenous people and communities provides a means of re-asserting control over country, livelihoods, and knowledge impacted through colonization (33). Indigenous research leadership has been changing the narrative so that Indigenous paradigms, community needs, priorities, and culture are at the center of health research, and designed to deliver benefit to Indigenous peoples (8). Capacity development of all involved in Indigenous health research remains a crucial factor for successfully developing this new research paradigm (8).

One 5-year Indigenous RCS intervention found that keys to success were: an agreement to embrace Indigenous research principles with creation of space for two-way learning between Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers; recognizing Indigenous ownership, leadership and respect as core to an Indigenous research agenda; and acknowledging “cultural difference challenges” inherent to relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers (34). As such, Indigenous health RCS must involve mutual learning (35)—“all teach, all learn”—and a strengths-based approach to Indigenous health research that embraces concepts of Indigenous wellbeing, knowledge and sovereignty (30, 36, 37).

The Centre developed and implemented a dedicated CQI-RCS Program, which intersects with its network and research programs, and seeks to enhance capacities within the Indigenous primary health-care setting to conduct and use CQI research. The Centre’s motto, “all teach, all learn” embodies the value placed upon mutual learning, where CQI-RCS Program users are both learners and teachers. CQI-RCS Program users include Indigenous and non-Indigenous:

• research translators: service providers, managers, policy makers, and communities in areas relevant to comprehensive primary health care in Indigenous communities.

• early-career researchers: post-graduate and undergraduate students; research project officers; Ph.D. candidates; early-career, and mid-career researchers.

• Senior researchers: more senior researchers with experience in research on CQI, comprehensive primary health care, health systems, and other related areas.

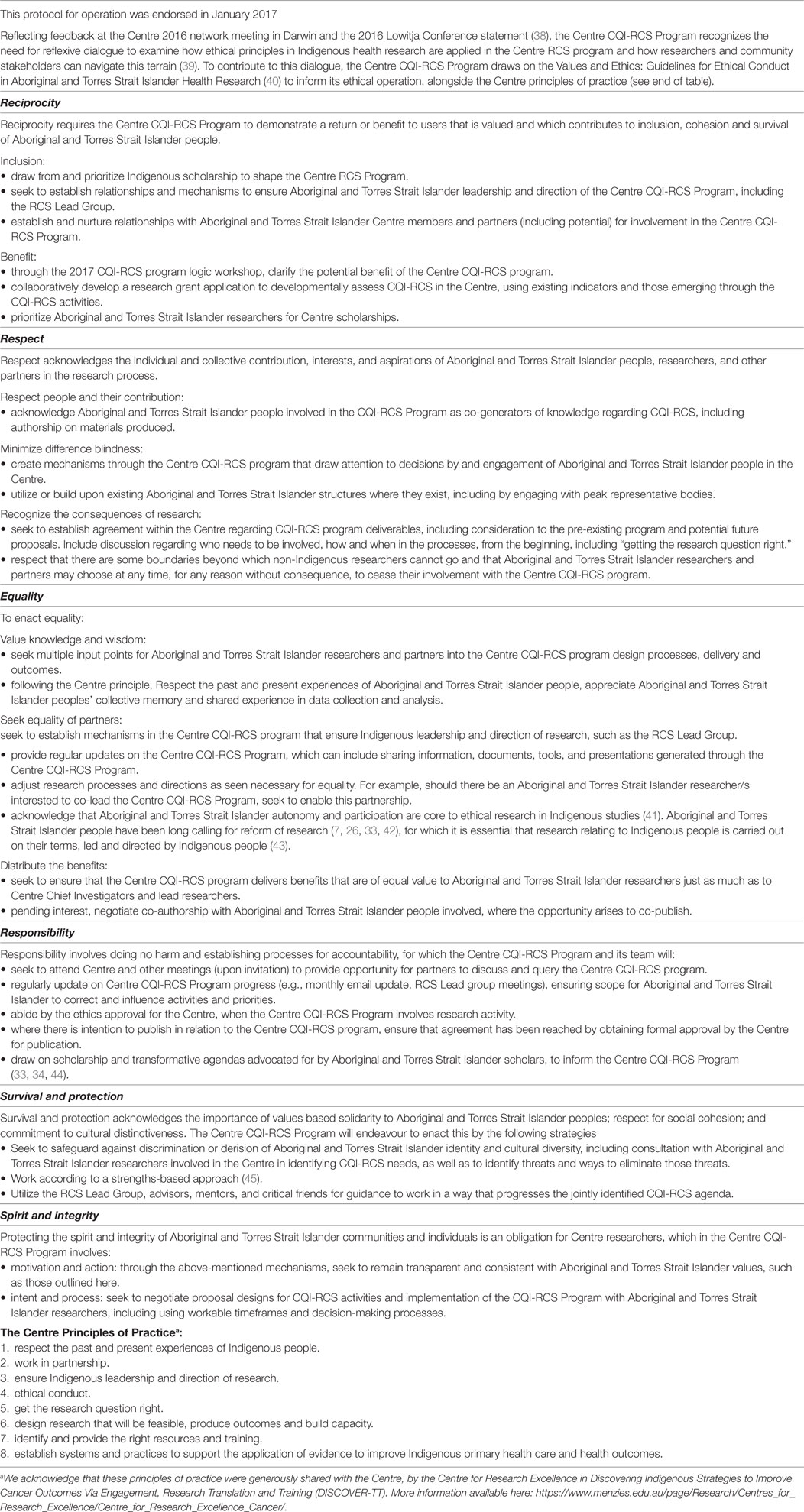

The collaborative development of the CQI-RCS model commenced with the appointment of a full-time RCS fellow in 2016, followed by establishment of a RCS Lead Group (Lead Group), development of a values and ethics protocol (Table 1), and construction of a program logic to guide the embedding of the CQI-RCS Program across the Centre’s activities.

Table 1. Values and ethics protocol for continuous quality improvement (CQI) research capacity strengthening (RCS).

The Lead Group, established in January 2017 by the non-Indigenous RCS Fellow (Karen McPhail-Bell) and co-chaired by Veronica Matthews, an Aboriginal researcher, guided the development of the CQI-RCS Program (see Terms of Reference in Supplementary Material). The Lead Group’s composition reflected systems-based participatory action research (21) and triads for enhancing RCS (hubs of research translators, early-career and senior researchers) (46). Members included Indigenous and non-Indigenous early-career and senior researchers, government and community-controlled health service representatives, who met monthly by teleconference during the development phase (see Acknowledgments). The Lead Group operated within the governance structure of the Centre, with co-lead representation at quarterly Centre Management Committee meetings.

The Lead Group developed a values and ethics protocol to express how the CQI-RCS Program would address the six values of ethical research with Indigenous people and communities (47) (Table 1). The protocol embodied the “all teach, all learn” maxim, with Indigenous members mentoring non-Indigenous members (and vice-versa), and senior researchers mentoring less experienced researchers. The protocol provided direction for the Lead Group’s approach to shared decision-making and activities, including creating space for dialog regarding matters of power and control over the CQI-RCS program.

A program logic describes how a program’s activities, impacts, outputs, and outcomes interact, to show the intended causal links (48). Development of the CQI-RCS Program logic sought to enact a collaborative partnership approach that, given the Indigenous health research context (described above), focused on the lived experiences, ideas, interests, and aspirations of Indigenous people (49, 50). Development occurred in four phases. First, through examination of key literature, particularly Indigenous scholarship in this space, and reflecting a strengths-based approach (45, 51), the Lead Group defined CQI-RCS as follows.

CQI-RCS means to enhance capacities to conduct and use CQI research that is valued by and of benefit to Indigenous peoples, in the Indigenous primary healthcare setting, with the specific purpose of supporting integrated quality improvement and building on the collaborative platform of the Centre.

CQI-RCS acknowledges existing strengths, knowledge and work. Through “all teach, all learn”, CQI-RCS involves a mutual exchange between Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers, research users, and communities to ensure sustained benefit from CQI research. CQI-RCS enables individuals, communities, organizations, services and broader systems to make informed decisions about, participate in, utilize, lead and generate CQI research.

Second, the Lead Group sought feedback from all members (approximately 70 individuals) of the Centre’s network regarding: current CQI-RCS successes and challenges; suggestions to support Indigenous leadership and participation in CQI research; and short-term and long-term outcomes that could inform the development of the program logic and the CQI-RCS Program.

Third, the Lead Group, Centre research-leads and invited Indigenous leaders in RCS came together for a 1-day workshop, designed and facilitated by Karen McPhail-Bell and Veronica Matthews with the Lead Group, to develop a CQI-RCS program logic model. Fourth, the Lead Group presented the model to the Centre’s bi-annual network meeting for feedback, prior to finalization.

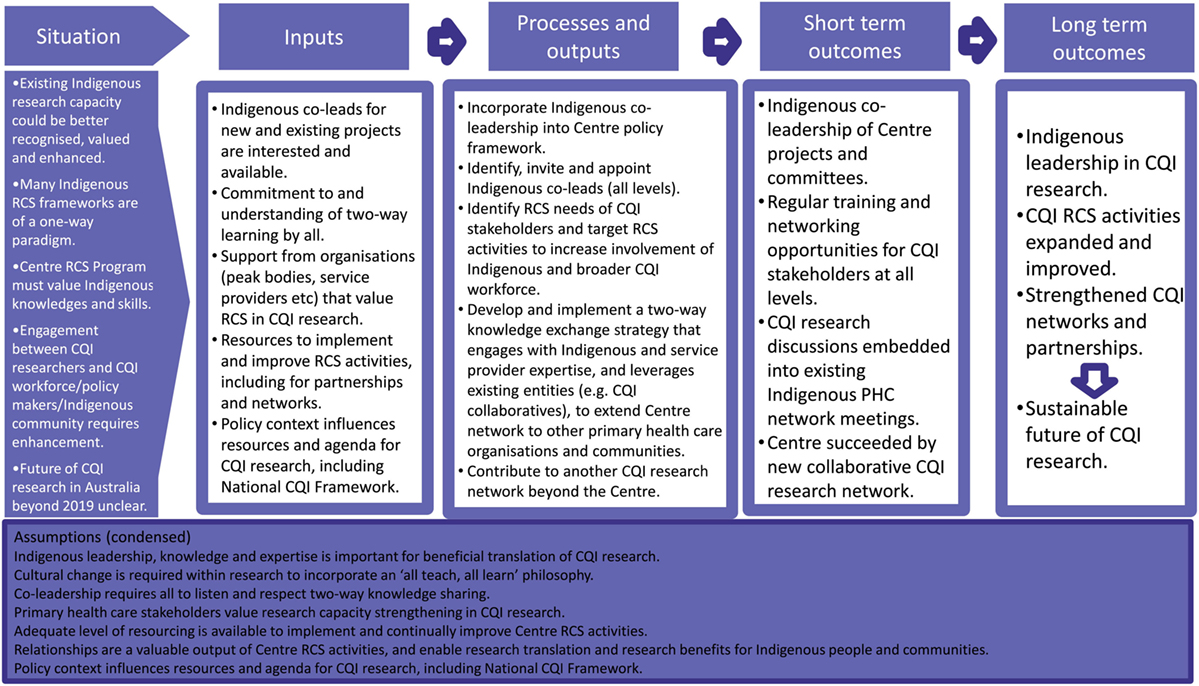

The program logic identifies CQI-RCS program priorities for implementation tied to short- and long-term outcomes, activities, participation, input, assumptions, and monitoring and evaluation indicators. The priorities are: indigenous co-leadership in the Centre’s CQI research; improve and expand the Centre’s RCS activities; strengthen CQI research networks and partnerships; and develop sustainable CQI research for improving Indigenous health through primary health care. A detailed program logic was produced for each of these priorities, which tied together in one overarching program logic map (Figure 1). The program logic model encapsulates the value of Indigenous-led CQI research for strengthening primary health care, to benefit Indigenous peoples and improve Indigenous health.

Figure 1. An overarching program logic “map” of the Centre’s Continuous Quality Improvement Research Capacity Strengthening Program.

Four principles informed the CQI-RCS approach and provide a possible starting point for those seeking to implement RCS models in Indigenous primary healthcare contexts. The principles are discussed in detail below: (1) mutual/two-way learning; (2) Indigenous co-leadership as core; (3) sharing power and facilitating relationships; and (4) resourcing and continuous improvement.

At the core of the “all teach, all learn” motto is the valuing of Indigenous cultures, knowledge, and expertise alongside Western research and knowledge, and recognition that different kinds of capacities are to be developed in different people, processes, organizations, and systems. For example, in the Indigenous primary health-care context, individual capacities include knowledge, skills, and experience to: conduct and critically assess research; participate in all stages of the research; contribute to research-informed action; maintain respectful relationships; and facilitate culturally safe processes. Consistent with other mutual RCS approaches, we found that not all the same capacities need to be developed in all stakeholders, and that such capacities are influenced by worldview, knowledge, experience, and relationships (11, 34). The Lead Group’s approach was informed by the collective understanding that in the Australian context, mutuality requires valuing Indigenous voices, identity and knowledge, and recognition of power held by decision-makers, institutions, and structures to improve or undermine Indigenous health (35, 52–56).

Indigenous-led research refers to research that is led and driven by Indigenous researchers, practitioners, policy makers, and communities in partnership with community organizations or through collaborative approaches involving Indigenous community/ies at each stage of the research process (53). As a step toward Indigenous leadership, the CQI-RCS model seeks to enact Indigenous co-leadership with non-Indigenous people already holding leadership roles. Across the Centre’s research projects, non-Indigenous leads have/are working to establish co-leadership arrangements with Indigenous people involved in those projects, in recognition of the capabilities and expertise brought by Indigenous people to the research process. Co-leads can be researchers, community members, service providers, and policy makers of varying seniority or position, who support mutual RCS. These co-lead arrangements involve attention to creating culturally safe spaces, as reflected in the values and ethics protocol (Table 1).

A commitment to Indigenous co-leadership brings considerations and tensions to negotiate collectively, to produce mutually beneficial outcomes. Methodologies that seek to support and value Indigenous knowledge within CQI research, and involve Indigenous people and their interests, are necessary (57). For non-Indigenous people in leadership roles, this means leading in partnership with Indigenous people and organizations, and seeking to share power over ownership of the research and associated decisions, processes, outcomes, and benefits.

The Lead Group provided a structure to enable Indigenous co-leadership of CQI-RCS and share decision-making and direction between diverse individuals and perspectives. The development process collectively identified and formalized the CQI-RCS priorities and approach, which provided momentum for power-sharing and involvement of more Indigenous people within the Centre. Respectful relationships underpinned these processes and structures, as reflected in the program logic (Figure 1). Strengthening networking and partnerships for CQI-RCS are key for transfer and implementation of innovations (58), and accountability and research priorities that benefit Indigenous Australians (7). Indigenous ownership and stakeholder relationships from the outset of research enhance the likelihood of research relevance and thus translation and benefit (43). Allowing sufficient time for meaningful relationship building is essential for quality research in this space and is a RCS activity itself as it enables respectful engagement with Indigenous knowledge and perspectives (26, 34, 59).

Resources (especially staffing) are required to enable the communication, relationships, engagement and training that facilitate CQI-RCS. Likewise, resourcing and continuous learning are essential to enable co-leadership, which is generally an additional responsibility for busy Indigenous translators/leaders/researchers. While the Lead Group developed the CQI-RCS program model, implementation will be the responsibility of all within the Centre. Using a continuous improvement approach, the Centre can now test application of the CQI-RCS program logic across its research programs and activities and monitor progress against the CQI-RCS priorities.

CQI-RCS must occur across multiple domains and levels to enable broader, systems-level engagement in health research at all stages, from research question formation to dissemination of outcomes. Our multi-level, systems view of CQI-RCS is consistent with other RCS models, such as that of Kahwa et al. (25) (described earlier) with integrated dimensions at individual, team, health service, network, and national levels. Our model adds to this by including the requirement that CQI-RCS is contextualized according to Indigenous leadership, knowledge, and aspirations, with principles to guide an approach to CQI-RCS.

As stated earlier, our model draws on generic and quality improvement capacity building evidence. Like quality improvement capacity building (10), knowledge is limited regarding methods to attribute successful elements to RCS interventions (25). The numerous RCS definitions in the literature (23, 60–63) are reported to have adversely affected development of meaningful assessment, monitoring, and evaluation of RCS; so has the context-specific and complex nature of RCS (25). The CQI-RCS principles presented here provide a pathway to address this knowledge gap, through implementation and evaluation in other contexts.

We acknowledge that while program logics have considerable merits, their linear and managerial format can be alienating, lack a systems perspective, and neglect relationships between people and process issues (64, 65). Some program logics include feedback loops to counter the typical linear approaches (66). Like other researchers (67, 68), we consider our program logic (Figure 1) to be an approximation of an anticipated path to be adjusted over time, rather than a replica of reality.

A strength of this CQI-RCS model is its emphasis upon inclusivity of voices and co-leadership, which is reflected in its collaborative development. A traditional, Western approach to research does not convey the model’s espoused principles of power-sharing, and Indigenous and non-Indigenous co-leadership. We are conscious that Indigenous health RCS may have produced unintended consequences of non-Indigenous researchers benefiting (through grants, publications, etc.) at the expense of Indigenous-led research (44, 69). However, these tensions are not reason to discontinue involvement of non-Indigenous researchers; nor do we believe this CQI-RCS work has been at the expense of Indigenous-led research. Rather, non-Indigenous researchers must uphold the struggle for genuine self-determination of Indigenous people and engage with Indigenous people as thinkers, knowers, and experts (30). Our model, with its guiding principles and logic, provides a tool to guide RCS in Indigenous primary health-care contexts, to enable sustained and Indigenous-controlled health research that benefits Indigenous people and communities, framed within a CQI and systems approach.

This paper presents the development of a CQI-RCS model in Indigenous primary health care. The program logic provides a framework for CQI-RCS implementation, monitoring and evaluation of collaboratively determined priorities and outcomes. This is important because there are no existing models of which we are aware that articulate and inform CQI-RCS in Indigenous primary health care in this way. The model also points to the importance of mutual learning, Indigenous co-leadership, power-sharing and sufficient resourcing. The new knowledge generated through developing this model echoes calls of Indigenous Australians seeking research reform that benefits Indigenous peoples (7, 26, 33, 57). The CQI-RCS model presents a possible pathway to enhance capacities to conduct and use CQI research that is valued by and of benefit to Indigenous peoples in the Indigenous primary health-care setting.

Co-Lead: Veronica Matthews, Research Fellow, Wingara Mura Leadership Program Fellow, The University of Sydney, University Centre for Rural Health; Co-Lead: Karen McPhail-Bell, Research Capacity Building Fellow, University of Sydney, University Centre for Rural Health; Kerry Copley, CQI Program Coordinator—Top End, Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance NT (AMSANT); Louise Patel, CQI Program Coordinator—Central Australia and the Barkly, AMSANT; Roxanne Bainbridge, Principal Research Fellow—Indigenous Health, School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, CQUniversity; Michelle Redman-MacLaren, Adjunct Academic, Centre for Indigenous Health Equity Research, CQUniversity; Senior Research Fellow, College of Medicine and Dentistry, James Cook University; Deborah Askew, Research Director, Southern Queensland Centre of Excellence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care (Inala Indigenous Health Service); Shanthi Ramanthan, Post Doctorate Fellow—Health Research Economics, Hunter Medical Research Institute; Nalita Turner, Researcher, Menzies School of Health Research; Ross Bailie, Director, University of Sydney, University Centre for Rural Health—North Coast; CIA the Centre; Jodie Bailie, Research Fellow (Evaluation), University of Sydney, University Centre for Rural Health; Isaac Hill (January–April 2017), Statewide Data and IT Coordinator—CQI Unit, Aboriginal Health Council of SA; Janya McCalman (January–April 2017), Senior Research Fellow, School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, CQUniversity.

KM-B conceived, drafted, reviewed, and finalized the manuscript for submission. All authors critically revised and approved this manuscript and, with the Lead Group (named in Acknowledgements), provided co-leadership for the Centre CQI-RCS work that forms this manuscript’s content.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors acknowledge the invaluable and ongoing direction and contributions by the Centre RCS Lead Group (see above). The authors also acknowledge active participation and contribution by those attending the CQI-RCS workshop on 20 March 2017, which included the CQI-RCS Lead Group, Heather D’Antoine, Juanita Sherwood, Sarah Larkins, and Chris Doran. The authors thank Kerryn Harkin for her support with organisation of the program logic workshop. The development of this manuscript would not have been possible without the support and commitment from the participants of the Centre for Research Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement.

The National Health and Medical Research Council funded the Centre for Research Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement (Grant ID 1078927).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00107/full#supplementary-material.

1. Anderson I, Robson B, Connolly M, Al-Yaman F, Bjertness E, King A, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (The Lancet–Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): a population study. Lancet (2016) 388(10040):131–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00345-7

2. Australian Government. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia (2017).

3. Bailie J, Schierhout G, Laycock A, Kelaher M, Percival N, O’Donoghue L, et al. Determinants of access to chronic illness care: a mixed-methods evaluation of a national multifaceted chronic disease package for Indigenous Australians. BMJ Open (2015) 5:e1–11. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008103

4. Davy C, Harfield S, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A, Grad F, et al. Access to primary health care services for Indigenous peoples: a framework synthesis. Int J Equity Health (2016) 15(1):163. doi:10.1186/s12939-016-0450-5

5. Bailie R, Si D, O’Donoghue L, Dowden M. Indigenous health: effective and sustainable health services through continuous quality improvement. Med J Aust (2007) 186(10):525–7.

6. Matthews V, Schierhout G, McBroom J, Connors C, Kennedy C, Kwedza R, et al. Duration of participation in continuous quality improvement: a key factor explaining improved delivery of type 2 diabetes services. BMC Health Serv Res (2014) 14(1):578. doi:10.1186/s12913-014-0578-1

7. Bainbridge R, Tsey K, McCalman J, Kinchin I, Saunders V, Lui FW, et al. No one’s discussing the elephant in the room: contemplating questions of research impact and benefit in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian health research. BMC Public Health (2015) 15:696. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2052-3

8. AIATSIS, The Lowtija Institute. Changing the Narrative in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research. Canberra: The Lowitja Institute (2017).

9. Otoo S, Agapitova N, Joy B. The Capacity Development Results Framework: A Strategic and Results-Oriented Approach to Learning for Capacity Development. Washington: The World Bank (2009).

10. Mery G, Dobrow MJ, Baker GR, Im J, Brown A. Evaluating investment in quality improvement capacity building: a systematic review. BMJ Open (2017) 7(2):e012431. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012431

11. Redman-MacLaren M, MacLaren D, Harrington H, Asugeni R, Timothy-Harrington R, Kekeubata E, et al. Mutual research capacity strengthening: a qualitative study of two-way partnerships in public health research. Int J Equity Health (2012) 11:79. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-11-79

12. Wise M, Angus S, Harris E, Parker S. National Appraisal of Continuous Quality Improvement Initiatives in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care. Canberra: The Lowitja Institute (2013). Available from: https://www.lowitja.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/CQI_Nat_Appraisal_Report-WEB.pdf (Accessed: December 14, 2016).

13. Bailie R, Bailie J, Larkins S, Broughton E. Editorial: continuous quality improvement (CQI) – advancing understanding of design, application, impact, and evaluation of CQI approaches. Front Public Health (2017) 5:306. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2017.00306

14. Gibson-Helm M, Rumbold AR, Teede HJ, Ranasinha S, Bailie R, Boyle JA. Improving the provision of pregnancy care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women: a continuous quality improvement initiative. BMC Preg Childbirth (2016) 16(1):118. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0892-1

15. Bailie J, Laycock A, Matthews V, Bailie R. System-level action required for wide-scale improvement in quality of primary health care: synthesis of feedback from an interactive process to promote dissemination and use of aggregated quality of care data. Front Public Health (2016) 4:1–12. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00086

16. Cunningham FC, Ferguson-Hill S, Matthews V, Bailie R. Leveraging quality improvement through use of the systems assessment tool in indigenous primary health care services: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res (2016) 16(1):583. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1810-y

17. Bonomi AE, Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, VonKorff M. Assessment of chronic illness care (ACIC): a practical tool to measure quality improvement. Health Serv Res (2002) 37(3):791–820. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.00049

18. Si D, Bailie R, Connors C, Dowden M, Stewart A, Robinson G, et al. Assessing health centre systems for guiding improvement in diabetes care. BMC Health Serv Res (2005) 5(1):56. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-5-56

19. NACCHO. National CQI Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care 2015 – 2025. NACCHO Position Statement. Canberra: National Aboriginal and Islander Health Organisation (2015).

20. The Lowitja Institute. National CQI Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care 2015-2025. Draft. Canberra: The Lowitja Institute (2015).

21. Bailie R, Matthews V, Brands J, Schierhout G. A systems-based partnership learning model for strengthening primary healthcare. Implement Sci (2013) 8:143. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-8-143

22. Jong-wook L. Global health improvement and WHO: shaping the future. Lancet (2003) 362:2083–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15107-0

23. Bates I, Akoto AYO, Ansong D, Karikari P, Bedu-Addo G, Critchley J, et al. Evaluating health research capacity building: an evidence-based tool. PLoS Med (2006) 3(8):1224–9. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030299

24. Kaseje D, Edwards N, Mortley N. Indicators for measuring and evaluating research capacity building. In: Edwards N, Kaseje D, Kahwa E, editors. Building and Evaluating Research Capacity in Healthcare Systems. Ottawa: UCT Press (2016). p. 215–48.

25. Kahwa E, Edwards N, Mortley N. Research capacity building: a literature review and the theoretical framework. In: Edwards N, Kaseje D, Kahwa E, editors. Building and Evaluating Research Capacity in Healthcare Systems: Case Studies and Innovative Models. Ottawa: UCT Press (2016). p. 1–260.

26. Smith LT. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd ed. Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago Press (2012).

27. Thomas D, Bainbridge R, Tsey K. Changing discourses in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research, 1914–2014. Med J Aust (2014) 201(1 Suppl):S15–8. doi:10.5694/mja14.00114

28. McPhail-Bell K, Bond C, Brough M, Fredericks B. “We don’t tell people what to do”: ethical practice and Indigenous health promotion. Health Promot J Aust (2015) 26(3):195–9. doi:10.1071/HE15048

29. Tsey K, Every A. Evaluating Aboriginal empowerment programs: the case of Family WellBeing. Aust N Z J Public Health (2000) 24(5):509–14. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.2000.tb00501.x

30. McPhail-Bell K, Nelson A, Lacey I, Fredericks B, Bond C, Brough M. Using an Indigenist framework for decolonising health promotion research. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Doing Cros. Singapore: Springer (2017). p. 1–20.

31. Gray M, Oprescu F. Role of non-Indigenous researchers in Indigenous health research in Australia: a review of the literature. Aust Health Rev (2016) 40(4):459–65. doi:10.1071/AH15103

32. Foster D, Williams R, Campbell D, Davis V, Pepperill L. ‘Researching ourselves back to life’: new ways of conducting Aboriginal alcohol research. Drug Alcohol Rev (2006) 25(3):213–7. doi:10.1080/09595230600644673

33. Rigney L-I. Indigenous Australian views on knowledge production and indigenist research. In: Kunnie JE, Goduka NI, editors. Indigenous Peoples’ Wisdom and Power: Affirming Our Knowledge. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Ltd (2006). p. 32–48.

34. Elston JK, Saunders V, Hayes B, Bainbridge R, McCoy B. Building Indigenous Australian research capacity. Contemp Nurse (2013) 46(1):6–12. doi:10.5172/conu.2013.46.1.6

35. Laycock A, Walker D, Harrison N, Brands J. Building capacity through research. In: Laycock A, Walker D, Harrison N, Brands J, editors. Researching Indigenous Health: A Practical Guide for Researchers. Canberra: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health (2011). p. 131–54.

36. Walker J, Lovett R, Kukutai T, Jones C, Henry D. Indigenous health data and the path to healing. Lancet (2017) 390(10107):2022–3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32755-1

37. Bond C, Brough M. The meaning of culture within public health practice – implications for the study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. In: Anderson I, Baum F, Bentley M, editors. Beyond bandaids: Exploring the underlying social determinants of Aboriginal health Papers from the Social Determinants of Aboriginal Health Workshop. Adelaide, Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health (2007). p. 229–38.

38. The Lowitja Institute. The Lowitja Conference Statement. Melbourne: The Lowitja Institute (2016). p. 1–2.

39. Morton Ninomiya ME, Pollock N. Reconciling community-based Indigenous research and academic practices: knowing principles is not always enough. Soc Sci Med (2017) 172:28–36. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.007

40. NHMRC. Values and Ethics: Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research. Canberra: Australian Government (2003). Available from: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/health_ethics/human/conduct/guidelines/e52.pdf (Accessed: November 5, 2016).

41. AIATSIS. Guidelines for Ethical Research in Australian Indigenous Studies. Canberra (2011). Available from: http://aiatsis.gov.au/research/ethical-research/guidelines-ethical-research-australian-indigenous-studies (Accessed: November 5, 2016).

42. Sjoberg D, McDermott D. The deconstruction exercise: an assessment tool for enhancing critical thinking in cultural safety education. Int J Crit Indig Stud (2016) 9(1):28–48.

43. Tsey K, Lawson K, Kinchin I, Bainbridge R, McCalman J, Watkin F, et al. Evaluating research impact: the development of a research for impact tool. Front Public Health (2016) 4:160. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00160

44. Bond C. What is NHMRC’s Capacity to Resource Indigenous-Led Research? The Croakey Blog (2016). Available from: https://croakey.org/leading-aboriginal-researcher-raises-some-critical-questions-for-the-nhmrc/ (Accessed: November 22, 2016).

45. Brough M, Bond C, Hunt J. Strong in the city: towards a strength-based approach in Indigenous health promotion. Health Promot J Aust (2004) 15(3):215–20. doi:10.1071/HE04215

46. Labonte R, Packer C, Schaay N, Sanders D. Improving “research-to-action” through research triads. In: Edwards N, Kaseje D, Kahwa E, editors. Building and Evaluating Research Capacity in Healthcare Systems: Case Studies and Innovative Models. Ottawa: UCT Press (2016). Available from: https://www.idrc.ca/en/book/building-and-evaluating-research-capacity-healthcare-systems-case-studies-and-innovative-models (Accessed: October 13, 2016).

47. National Health and Medical Research Council. Ethical Conduct in Research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and Communities: Guidelines for Researchers and Stakeholders. Public Consultation Draft. Canberra: Australian Government (2017).

48. Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence. Developing and Using Program Logic: A Guide. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health (2017). Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/research/Publications/developing-program-logic.pdf (Accessed: December 28, 2017).

50. Rigney L-I. Internationalisation of an Indigenous anti-colonial cultural critique of research methodologies: a guide to indigenist research methodology and its principles. Annual International Conference Proceedings: Research and Development in Higher Education: Advancing International Perspectives. Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australia (HERDSA) (1999). p. 109–21. doi:10.2307/1409555

51. Mittelmark MB, Bull T. The salutogenic model of health in health promotion research. Glob Health Promot (2013) 20(2):30–8. doi:10.1177/1757975913486684

52. Nicholls R. Research and Indigenous participation: critical reflexive methods. Int J Soc Res Methodol (2009) 12(2):117–26. doi:10.1080/13645570902727698

53. Clapham K. Indigenous-led intervention research: the benefits, challenges and opportunities. Int J Crit Indig Stud (2011) 4(2):40–8.

54. Evans M, Miller A, Hutchinson P, Dingwall C. Decolonizing research practice: indigenous methodologies, Aboriginal methods, and knowledge/knowing. In: Leavy P, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2014). p. 179–91.

55. Hayman N, Reid P, King M. Improving health outcomes for Indigenous peoples: what are the challenges? Editorial. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2015) 8:6–9. doi:10.1002/14651858.ED000104

56. Bond C. Starting at strengths… an Indigenous early years intervention. Med J Aust (2009) 191(3):175–7.

57. Rigney L-I. A first perspective of indigenous Australian participation in science: framing indigenous research towards indigenous Australian intellectual sovereignty. Chamcool Conference. Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary (2001).

58. McCalman J, Tsey K, Clifford A, Earles W, Shakeshaft A, Bainbridge R. Applying what works: a systematic search of the transfer and implementation of promising Indigenous Australian health services and programs. BMC Public Health (2012) 12:600. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-600

59. Bond C, Foley W, Askew D. “It puts a human face on the researched” – A qualitative evaluation of an Indigenous health research governance model. Aust N Z J Public Health (2015) 40:89–95. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.12422

60. Department for International Development. How to Note: Capacity Building in Research. A DFID Practice Paper. London: DFID (2010). p. 1–42. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/187568/HTN_Capacity_Building_Final_21_06_10.pdf (Accessed: February 25, 2017).

61. Edwards N, Kaseje D, Kahwa E. Building and Evaluating Research Capacity in Healthcare Systems: Case Studies and Innovative Models. Capetown: UCT Press (2016).

62. Cooke J. A framework to evaluate research capacity building in health care. BMC Fam Pract (2005) 6:44. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-6-44

63. Kayrooz C, Chambers B, Spriggs J. Between four worlds: building research capacity in Papua New Guinea. Dev Pract (2006) 4524(791963552):97–102. doi:10.1080/09614520500451345

64. McPhail-Bell K, MacLaren D, Isihanua A, MacLaren M. From “what” to “how” – capacity building in health promotion for HIV/AIDS prevention in the Solomon Islands. Pac Health Dialog (2007) 14(2):124–31.

65. Grove NJ, Zwi AB. Beyond the log frame: a new tool for examining health and peacebuilding initiatives. Dev Pract (2008) 18(1):66–81. doi:10.1080/09614520701778850

66. Greenhalgh T, Fahy N. Research impact in the community-based health sciences: an analysis of 162 case studies from the 2014 UK research excellence framework. BMC Med (2015) 13(1):232. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0467-4

67. Searles A, Doran C, Attia J, Knight D, Wiggers J, Deeming S, et al. An approach to measuring and encouraging research translation and research impact. Health Res Policy Syst (2016) 14:60. doi:10.1186/s12961-016-0131-2

68. Ramanathan S, Reeves P, Deeming S, Bailie RS, Bailie J, Bainbridge R, et al. Encouraging translation and assessing impact of the Centre for Research Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement: rationale and protocol for a research impact assessment. BMJ Open (2017) 7(12):e018572. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018572

Keywords: research capacity strengthening, continuous quality improvement, Indigenous leadership, research translation, primary health-care services, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, Indigenous health, collaborative leadership

Citation: McPhail-Bell K, Matthews V, Bainbridge R, Redman-MacLaren ML, Askew D, Ramanathan S, Bailie J and Bailie R (2018) An “All Teach, All Learn” Approach to Research Capacity Strengthening in Indigenous Primary Health Care Continuous Quality Improvement. Front. Public Health 6:107. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00107

Received: 17 September 2017; Accepted: 03 April 2018;

Published: 30 April 2018

Edited by:

Edward Broughton, University Research Co, United StatesReviewed by:

Hugh J. S. Dawkins, Government of Western Australia Department of Health, AustraliaCopyright: © 2018 McPhail-Bell, Matthews, Bainbridge, Redman-MacLaren, Askew, Ramanathan, Bailie and Bailie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karen McPhail-Bell, a2FyZW4ubWNwaGFpbC1iZWxsQHN5ZG5leS5lZHUuYXU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.