94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Public Health , 23 March 2018

Sec. Public Health Policy

Volume 6 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00093

This article is part of the Research Topic Public Health Nutrition: Assessing Evidence to Determine Policy and Practice View all 9 articles

Nutrition is an important component of public health and health care, including in education and research, and in the areas of policy and practice. This statement was the overarching message during the third annual International Summit on Medical Nutrition Education and Research, held at Wolfson College, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, in August 2017. This summit encouraged attendees to think more broadly about the impact of nutrition policy on health and communities, including the need to visualize the complete food system from “pre-farm to post-fork.” Evidence of health issues related to food and nutrition were presented, including the need for translation of knowledge into policy and practice. Methods for this translation included the use of implementation and behavior change techniques, recognizing the needs of health-care professionals, policy makers, and the public. In all areas of nutrition and health, clear and effective messages, supported by open data, information, and actionable knowledge, are also needed along with strong measures of impact centered on an ultimate goal: to improve nutritional health and wellbeing for patients and the public.

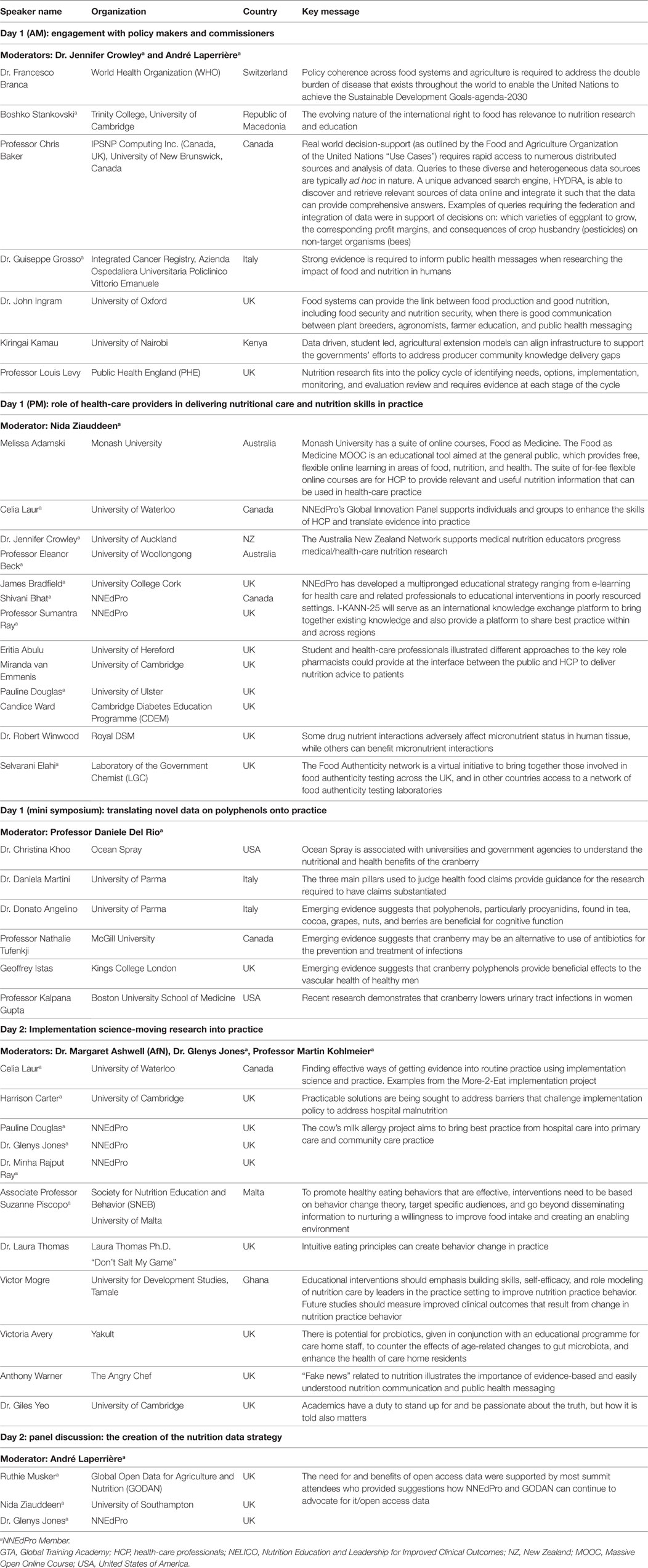

Nutrition has a vital role in maintaining health and preventing disease. As such, a chain of events from food production, through the food environment to dietary choices, advice and interventions, summatively impact nutritional status, thus modulating health or disease. With an increasing recognition of the preventative role of nutrition in health-related policy and practice, effective strategies are needed to bridge current divides between nutrition research and professional education, as well as between the agricultural and human health-related knowledge bases in nutrition. This was the main message of the third annual International Summit on Medical Nutrition Education and Research event hosted by the Need for Nutrition Education/Innovation Programme (NNEdPro) Global Centre for Nutrition and Health, and the Global Open Data for Agriculture and Nutrition (GODAN) at Wolfson College, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom (UK) on August 1–2, 2017. The Summit brought together international organizations and individuals involved in nutrition education and research. This year, the focus was on how to work together to build a strong evidence base and translate that evidence into policy and practice, looking at the whole system of food, nutrition, and health. A schematic representation of the conference theme, as outlined by Sumantra Ray (SR) and André Laperrière (AL) is provided in Figure 1, and a list of speakers and key messages is in Table 1. The aim of this perspective is to outline key messages from the Summit and present ideas for future consideration.

Table 1. Speakers and key messages from the Third International Summit on Medical Nutrition Education and Research.

While nutritional issues can be approached from different perspectives when considering individual United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), the UN Decade of Action on Nutrition aims to bring together a matrix of SDG-relevant actions with Nutrition as a common denominator (1, 2). Considering a food systems approach, it is recognized that well-designed policy can impact “pre-farm” by influencing food production from the very beginning of the food-cycle. Determining what crops farmers grow can impact on the farming methods needed to tend and nurture the crop, as well as influence resultant yields. Farming practices also impact food production, which impacts on food environment and nutrient quality, thus subsequently influencing dietary choices, leading to the “post-fork” impact on nutritional and health status. Examining this whole systems approach demonstrated the need for strong evidence and ways to translate that evidence into policy and practice at all levels within the system, including clear communication, and public health messaging.

Engaging with policy makers and commissioners is essential, particularly when looking at improving health outcomes of individuals by taking a systems approach of “pre-farm to post-fork.” In line with this approach, Franceso Branca from the World Health Organization (WHO) outlined priorities for global nutrition policy in the context of the SDG—agenda 2030, particularly Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security, and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture (1). Policy makers should be addressing the double burden of malnutrition, as undernutrition or overweight/obesity, combined with nutrition-related non-communicable diseases (NCD), can all play a role at individual, household, and population levels, and across the lifespan. Policy coherence is needed across food systems and agriculture, and the UN Decade of Action on Nutrition (2) demonstrates that nutrition is a key concern for the WHO commission.

Policy makers should also recognize that access to open data can support policy decisions in agriculture. For example, Chris Baker presented a search tool that provides a user-friendly graphical interface, for complex ad hoc query composition suitable for policy makers or programme managers. This tool will have a query engine that is able to discover online data resources from multiple organizations (e.g., the European Food Safety Authority), retrieve, and integrate the data on a per query basis. This tool could help determine the type of crops and quantities to be grown that would contribute to a healthier diet for a specific population demographic.

John Ingram discussed how policy makers should know the potential for food systems to bridge food production and nutrition. As part of this, they should recognize the differences between the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations definition of “food security,” and the Committee on World Food Security (CFS) definition of “nutrition security.” Overall, “nutrients are seen as a crucial component of security, and food security is seen as a crucial component of nutrition security” (3, 4). A food system perspective is needed to structure the necessary dialog between researchers along the whole food chain (plant breeders, agronomists,1 extension services (farmer education),2 raw material processors, final product processors, through to nutritionists, anthropologists, and behavioral psychologists) to link agriculture to nutrition outcomes. Policy makers should also acknowledge the need to educate farmers about which crops to grow/produce, as discussed by farmer and agricultural economist, Kiringai Kamau.

From a cross-border legal perspective, the evolving nature of the international right to food, and its relevance within nutrition research and education was presented by Bosko Stankovski. Policy makers should know that the right to food is progressive and should be seen as dynamic, not static, as evidenced in three UN documents (5–7). Giuseppe Grosso discussed the need for strong evidence to inform policy and public health messages, recognizing the limitations of some studies, including the ethical challenges when researching the impact of food and nutrition in humans.

Louis Levy (LL) of Public Health England (PHE) presented a UK perspective on nutrition evidence, policy development, and implementation. LL discussed how nutrition research fits into the policy cycle of identifying needs and options, following through to implementation, monitoring, and evaluation/review. Evidence is required at each stage of the cycle and is accompanied by consultation when applicable.

To put nutrition policies into practice, one approach is to focus on educating health-care providers and developing their skills to deliver safe and effective nutrition care. For example, the Food as Medicine, Massive Open Online Course, presented by Melissa Adamski, provides free, flexible, online learning for the general public, with education on the relationship between food, nutrition, and health. Under this Food as Medicine brand, a suite of for-fee online courses have also been developed for health-care professionals (HCP) without a nutrition background, or as refresher courses for nutrition professionals (8), a number of which have been externally quality assured by the UK Association for Nutrition.

To further encourage international shared learning in nutrition education, the NNEdPro’s Global Innovation Panel (GIP) supports individuals and groups to work and learn together to enhance the skills of HCP and translate evidence into practice. For example, within GIP, the Australia and New Zealand Network (ANZ Network) aims to support medical nutrition educators progress medical/health-care nutrition research. NNEdPro is also developing e-learning materials for the University of Cambridge, School of Clinical Medicine, which is also included as pre-learning material for the NNEdPro Summer School Foundation Certificate Course in Applied Human Nutrition. The global application of such teaching methods was illustrated in NNEdPro’s Urban Slum Project that delivered a series of workshops to educate local HCP and lay volunteers on delivering nutrition advice to the urban slum population in India (9).

Another way that NNEdPro supports HCP education is through the International Knowledge Application Network in Nutrition 2025 initiative (I-KANN-25), which uses the global increase in NCDs as an example to illustrate its application. I-KANN-25 is part of NNEdPro’s education and training academy, which facilitates: nutrition education at the University of Cambridge; the Summer School in Applied Human Nutrition (Cambridge); the annual International Summit (Cambridge); and e-learning initiatives. I-KANN-25 seeks to connect materials from these initiatives and more, to be used internationally, such as through the development of an online portal, which will encourage regional adaptations and opportunities for international interaction to facilitate learning. The I-KANN-25 online network will be modeled on the Food Authenticity Network, developed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). The Defra initiative spans 21 countries to bring together those involved in food authenticity testing (10).

Pharmacists play a key role within primary care, often having more contact with members of the community than other HCP (11). For this reason, pharmacists are a key group that should be aware of the importance of nutrition. To highlight this opportunity/need, NNEdPro ran an essay competition entitled, “The role of nutrition in pharmacy settings.” The competition, the third in a series of annual NNEdPro essay competitions (12, 13), was open to those working in or studying pharmacy, and those attending the NNEdPro Summer School. The pharmacy winner was University of Herefordshire student, Eriata Abulu who presented ideas from her essay, as did Summer School student winner, Miranda Van Emmenis. Both competition winners and a panel of speakers highlighted that with additional training, pharmacists could fulfill a key role at the interface between the public and HCP to deliver evidence-based nutrition messages.

To demonstrate a specific example of how nutrition science integrates with pharmacists’ clinical role, Robert Winwood presented on drug nutrient interactions.

The emerging evidence regarding the benefits of polyphenols provided an interesting case study on how evidence-based nutrition that has proven clinical effectiveness can be translated into practice. To present this case, Daniele Del Rio (DDR) provided an introduction to polyphenols, while Christina Khoo set the scene by outlining Ocean Spray’s history and collaboration of research with universities, government agencies, and other companies to highlight evidence regarding the impact of cranberries on health.

A series of researchers outlined emerging evidence for polyphenols in health. Daniela Martini presented on requirements for scientific substantiation of health claims, indicating the benefits of using the three main pillars on which food claims are judged to provide guidance for the quality research required to have claims substantiated (14, 15). Donato Angelino presented evidence suggesting that polyphenols, in particular, proanthocyanidins, found in tea, cocoa, grapes, nuts, and berries, are beneficial for cognitive function. However, lack of robust biomarkers of dietary intake hampers progress in this field. Geoffrey Istas presented on the effects of polyphenols on vascular function in healthy men. Nathalie Tufenkji discussed cranberry as an alternative for prevention of urinary tract infections (UTIs), an infection that contributes to global spread of antibiotic resistance. Kalpana Gupta focused on the impact of cranberry on UTIs, the most common bacterial infection in women (16). KG’s research among women with recent history of UTI demonstrates a lowered number of symptomatic UTI episodes for those consuming cranberry juice (17), suggesting an alternative preventative measure.

With the expanding evidence in nutrition research, knowing when and how to get that research into practice is key. Knowledge translation, implementation, behavior change, and communication of nutrition messages are important components when translating this research into practice. Celia Laur presented an example of an effective implementation project from the Canadian More-2-Eat project, which improved nutrition care in five Canadian hospitals. By working with hospital champions and support teams, and using a variety of implementation and behavior change strategies, all five hospitals successfully implemented nutrition screening, and a method of triaging at risk patients to receive appropriate care. A toolkit to support implementation is available online (18), and plans are underway to sustain change and spread nationally and internationally, including in the UK.

In the UK context, a barrier to addressing hospital malnutrition is the confusion and misunderstanding about who is responsible for malnutrition. Harrison Carter (HC) explained the need for HCP to understand how to get policy into practice, including how it may require a whole system/service change, such as staff contractual alterations and workforce agreements. He also mentioned the costs associated with implementation to improve hospital malnutrition as another barrier. Medical nutrition education at all levels was one practical recommendation to address policy implementation barriers.

Another UK example of an implementation project underway focused on nutritional management of cow’s milk allergy, currently, a neglected clinical area. The aim is to bring examples of best practice from hospital care into primary and community practice for this most common food allergy in infants and young children. Focus groups and interviews are being conducted to inform what needs to be done and how, with a theory of change model being created.

Presenting accurate nutrition messages in a way that is easy to understand is another important aspect within public health. Anthony Warner, a well-known blogger with a “temperament,” presented on bad science and the truth about healthy eating. Faddish diets from insta-food stars thrive in a world that favors easy explanation. People are attracted to these easy explanations over real science, potentially making decisions harmful to health. In a world of “fake news” with many providing their opinion on nutrition, qualified nutrition professionals have an important role in providing information that is evidenced based and easily understood.

While messaging is important, we also need to change behavior. To effectively promote healthy eating behaviors, Suzanne Piscopo discussed how nutrition interventions should be based on behavior change theory, target specific audiences, and go beyond disseminating information to nurturing willingness to improve food intake and creating enabling environments (19). Laura Thomas provided an example of this, describing use of intuitive eating principles in practice to create changes in behavior (20). A broader perspective was taken by Victor Mogre who explained the evidence from across several countries regarding educational interventions to improve nutrition care competencies and delivery by doctors and other HCP (21). When it comes to medical nutrition education, there is far more in common across regions than there are differences. Needs assessments should inform the design of interventions in order to improve nutrition practice behavior.

Giles Yeo’s (GY) presentation, although focused on the genetics of body weight and several unique examples, provided a strong emphasis on nutrition communication, and transmission of that message from trusted sources. GY argued that academics have a duty to be passionate about the truth, but how the truth is told also matters.

Continuing with the translation of nutrition evidence into practice, another area with growing evidence is the use of probiotics in a care home environment, which was presented by Victoria Avery. This educational programme is used to increase care home staff knowledge of the potential benefits that probiotics can provide. Caryl Nowson provided another example of nutrition translation and the promotion of healthy aging through bringing together the training of medical, nursing, nutrition, and physical activity HCP. Many HCP include professional domains for lifestyle approaches to reducing disease, which enables nutrition in care of the older person to be made part of everyone’s business. To translate this approach into action, examples were provided including a project to increase muscle mass and strength in women living independently in retirement villages (22). The recommendation was that if all HCP curricula included nutrition competencies, skills learned would provide opportunities to develop real-world inter-disciplinary approaches for: disease prevention and management to identify nutritional risk; the importance of lifestyle to patients for health; and support nutritional self-management of patients.

There is a need for open nutrition data in all of its forms (i.e., source data, descriptive collated information, research intelligence, and evidence synthesis) to be available for relevant experts to access and analyze. A discussion, chaired by AL and led by Ruthie Musker, Nida Ziauddeen, and Glenys Jones, outlined the need for and use of open data. A significant challenge raised during the discussion was ethics; the need for consent from participants, through to challenges of ethical approval at organization level. For example, whether university ethics review boards would approve collection and future use as open data. Most people recognized the need for and benefits of open data and provided suggestions for how NNEdPro and GODAN can continue to advocate and develop systems for open data access, such as the use of trials registries and repositories, formats for standardizing the anonymization of subject data, and ways to link data sources.

Nutrition education provides the means to connect the ever-expanding and changing body of research-based evidence to policy and practice. This year, the Summit focused more broadly on how to impact policy and the need to concentrate on the full food system from “pre-farm to post-fork.” Once it is clear that strong evidence exists and the timing is right for translation into policy and practice, implementation and behavior change techniques should be employed, targeting HCP and the public. In all areas within nutrition and health, clear and effective messages are needed along with strong measures of impact centered on an ultimate goal: to improve nutritional health and wellbeing for patients and the public with a longer term view to link nutritional interventions, both at population and individual levels, to measureable health outcomes.

Ethical approval was not required for this article because the risk to summit participants was deemed minimal, and all speakers consented to the inclusion of their details and key messages.

JC and CL led on writing the manuscript, while JC, CL, HC, GJ, and SR were involved in editing and finalizing this article. SR provided senior oversight. All authors were involved in organizing the Summit. All speakers in Table 1 were provided the opportunity to review this article to ensure accurate reflection of their presentations, however, were not involved in writing.

JC, CL, HC, GJ, and SR are core members of the NNEdPro group, which hosted the Summit.

The Royal College of Physicians and the Royal Society of Biology accredited this event for Continuing Professional Development points. The programme from the Summit is available online. CL and HC chaired the event, with leadership from all NNEdPro directors including SR, Pauline Douglas (PD), DDR, Minha Rajput-Ray (MRR), and AL. The authors extend thanks to all speakers, moderators, and attendees for their informative and insightful contributions to the Summit. The authors also wish to thank all those involved in coordinating the Summit, including NNEdPro Directors, SR, PD, MRR, DDR, as well as team members Dr. Lauren Ball, Shivani Bhat, James Bradfield, and Francesca Ghelfi. Thanks also to partner organizations of the NNEdPro Group including the British Dietetic Association (BDA), Global Open Data for Agriculture and Nutrition (GODAN), Society for Nutrition Education and Behaviour (SNEB), Ulster University School of Biomedical Sciences, and Cambridge University Health Partners (including Cambridge University Hospitals and the School of Clinical Medicine).

This Summit was supported by: Platinum Level: GODAN and DSM; Key supporters: Mead Johnson, and Yakult; Symposium Supporter: Ocean Spray; Associated Supporters and Knowledge Partners: American Society of Nutrition (ASN), British Nutrition Foundation (BNF), Cambridge Diabetes Education Programme, Lead Government Chemist (LGC), MyFood24, Parenteral Enteral Nutrition (PEN), The Nutrition Society. The annual Summit is also made possible by support in kind from NNEdPro’s strategic partners, including, the British Dietetic Association, University of Cambridge, Ulster University, and the Society for Nutrition Education and Behaviour.

1. United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals (2015). Available from: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed September 2017).

2. United Nations. United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition 2016-2025 (2017). Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/decade-of-action/en/ (accessed September 2017).

3. Food and Agricultural Organization. The State of Food and Agriculture. Available from: http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/w1358e/w1358e00.htm

4. Committee on World Food Security. Report of the 39th Session of the Committee on World Food Security (2012). Available from: http://www.fao.org/bodies/cfs/cfs39/en/ (accessed September 2017).

5. United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Available from: http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ (accessed September 2017).

6. United Nations. International Covenant on Cultural, Economic and Social Rights (1966). Available from: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx (accessed September 2017).

7. United Nations. Food Assistance Convention (2003). Available from: http://www.ifrc.org/docs/idrl/I1060EN.pdf (accessed September 2017).

8. Monash University. Food as Medicine (2017). Available from: https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/food-as-medicine (accessed September 2017).

9. Rajput-Ray M, Bhat S, Roy AR, Banerjee R, Ray S. Is there a solution to tackle child malnutrition in urban slums? CN Focus (2016) 8:3.

10. Food Authenticity Network. Food Authenticity a Virtual Network for Food Authenticity Analysis 2017 (2017). Available from: http://www.foodauthenticity.uk/ (accessed September 2017).

11. World Health Organization Consultative Group. The Role of the Pharmsist in the Healthcare System (1994). Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh2995e/1.6.2.html#Jh2995e.1.6.2 (accessed September 2017).

12. The NNEdPro Group. Strengthening doctors nutrition knowledge and education. CN Focus (2015) 15:2.

14. Martini D, Rossi S, Biasini B, Zavaroni I, Bedogni G, Musci M, et al. Claimed effects, outcome variables and methods of measurement for health claims proposed under European Community Regulation 1924/2006 in the framework of protection against oxidative damage and cardiovascular health. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis (2017) 27:473–503. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2017.01.008

15. Martini D, Biasini B, Rossi S, Zavaroni I, Bedogni G, Musci M, et al. Claimed effects, outcome variables and methods of measurement for health claims on foods proposed under European Community Regulation 1924/2006 in the area of appetite ratings and weight management. Int J Food Sci Nutr (2017):1–21. doi:10.1080/09637486.2017.1366433

16. Gupta K, Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Stamm WE. Patient-initiated treatment of uncomplicated recurrent urinary tract infections in young women. Ann Int Med (2001) 135:9–16. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-1-200107030-00004

17. Beerepoot M, Ter Riet G, Nys S. Lactobacilli versus antibiotics to prevent urinary tract infections. A randomized double-blind non-inferiority trial in postmenopausal women. Arch Int Med (2012) 172:704–12. doi:10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.111

18. Canadian Malnutrition Taskforce. More-2-Eat Implementation Project. Available from: http://nutritioncareincanada.ca/research/more-2-eat-implementation-project

19. Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. Implement Sci (2011) 6:42. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

21. Mogre V, Scherpbier A, Stevens F, Aryee P, Cherry M, Dornan T. Realist synthesis of educational interventions to improve nutrition care competencies and delivery by doctors and other healthcare professionals. BMJ Open (2016) 6:e010084. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010084

22. Daly R, O’Connell S, Mundell N, Grimes C, Dunstan D, Nowson C. Protein-enriched diet, with the use of lean red meat, combined with progressive resistance training enhances lean tissue mass and muscle strength and reduces circulating IL-6 concentrations in elderly women: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Amer J Clin Nutr (2014) 99:899–910. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.064154

Keywords: nutrition, public health, health care, policy, global food systems, implementation

Citation: Crowley JJ, Laur C, Carter HDE, Jones G and Ray S (2018) Perspectives from the Third International Summit on Medical Nutrition Education and Research. Front. Public Health 6:93. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00093

Received: 21 November 2017; Accepted: 12 March 2018;

Published: 23 March 2018

Edited by:

Carmencita David Padilla, University of the Philippines Manila, PhilippinesReviewed by:

Georgi Iskrov, Plovdiv Medical University, BulgariaCopyright: © 2018 Crowley, Laur, Carter, Jones and Ray. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer Jean Crowley, amVubmlmZXJjcm93bGV5MDk5QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==;

Sumantra Ray, c3I1MDZAY2FtLmFjLnVr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.