94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Public Health, 26 March 2018

Sec. Radiation and Health

Volume 6 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00085

In recent years, the effects of electromagnetic fields (EMFs) on the immune system have received a considerable interest, not only to investigate possible negative health impact but also to explore the possibility to favorably modulate immune responses. To generate beneficial responses, the immune system should eradicate pathogens while “respecting” the organism and tolerating irrelevant antigens. According to the current view, damage-associated molecules released by infected or injured cells, or secreted by innate immune cells generate danger signals activating an immune response. These signals are also relevant to the subsequent activation of homeostatic mechanisms that control the immune response in pro- or anti-inflammatory reactions, a feature that allows modulation by therapeutic treatments. In the present review, we describe and discuss the effects of extremely low frequency (ELF)-EMF and pulsed EMF on cell signals and factors relevant to the activation of danger signals and innate immunity cells. By discussing the EMF modulating effects on cell functions, we envisage the use of EMF as a therapeutic agent to regulate immune responses associated with wound healing.

The immune system is constituted by a very complex network of cells, tissues, and organs that through soluble factors and direct cell-to-cell contacts interact among themselves and with cells belonging to other (organ) systems. This network is the main organizational feature that allows the immune system to keep its dynamic equilibrium (homeostasis) through activating and inhibitory signals and, at the same time, to adapt the response to environmental cues. A healthy immune system permits the organism to interact with the environment in a safe way, keeping invading pathogens under control. At the same time, it “ignores” microorganisms and/or antigens that do not represent a danger for the host.

Perturbing agents, such as toxic compounds (1), ionizing radiation (2), and some pathogens (3) can compromise the integrity of the immune system as they damage immune cells and/or irreversibly alter some immune functions. If the organism is exposed to these factors during early life, when the maturing immune system is particularly susceptible, damages may be immediate, but can also emerge only late in life (4).

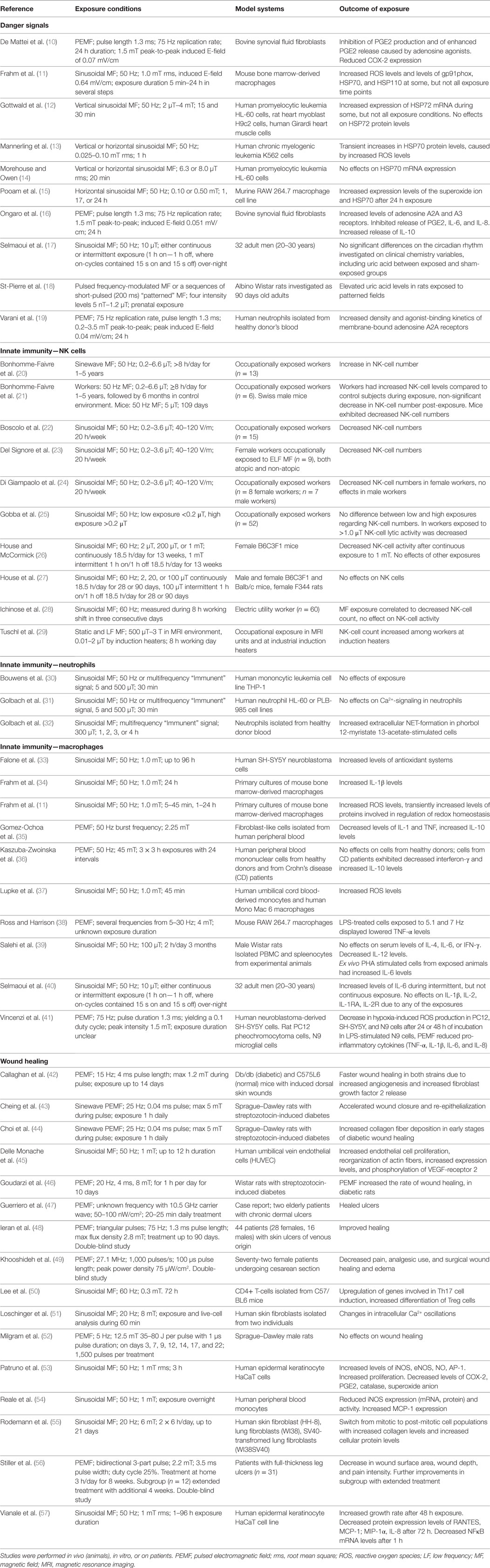

Biological effects of the exposure to electromagnetic fields (EMFs) were investigated in a large number of biological targets, including the immune system. The effects depend on frequency, amplitude, and duration of exposure as well as on the characteristics of the targeted cell types. Concerns on possible detrimental effects of extremely low frequency (ELF)-EMF exposure on human health were raised but, due to contradictory conclusions, no consensus was reached (5). Noteworthy, in recent years the possibility to use EMF exposure to modulate immune cell responses has been proposed and debated (6–9). In the present review, focusing on responses to ELF-EMFs and pulsed EMFs (PEMFs), we discuss experimental evidence and unmet issues of this hypothesis, in the context of the current view of the immune system. Nowadays, the immune system is thought to be activated by “danger signals” which are relevant not only to the induction of inflammation and immune responses but also to the activation of counter regulatory (anti-inflammatory/modulatory) mechanisms required to shutdown inflammation and allow tissue healing. While description and discussion of the quoted articles is done in a narrative way throughout the manuscript, the details on exposure conditions of each cited study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Available study details in papers cited in sections on danger signals, innate immunity and wound healing, that are dealing with experimental effects of MF exposure.

According to the historical self/non-self paradigm, the immune system would generate a response against foreign (non-self) antigens and not against antigens belonging to the organism (self) (58, 59). With time this model was challenged by new findings and revisited. Indeed, the immune system not only recognizes specific antigens (through the antigen-specific receptors of T and B lymphocytes), but also some characteristics or patterns common to groups of infectious agents (pathogen-associated molecular patterns, PAMPs) (60). PAMPs are recognized by germ-line gene-encoded receptors, commonly referred to as pattern recognition receptors (PRR), which are expressed on cells of both the innate and the adaptive immunity. The identification and characterization of toll-like receptors and other groups of PRR, substantiated PAMPs as the initial triggers of an immune response against invading organisms (61, 62). Subsequently, Matzinger (63, 64) proposed that not only external antigens but also self-components, when representing a danger, can trigger an immune response (danger theory). Hence, non-self “safe” antigens would be tolerated by the immune system, as (normally) is the case with commensal bacteria and food antigens.

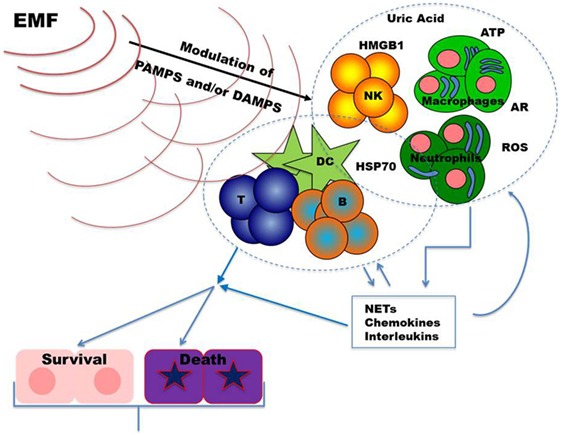

During tissue damage or cell death a broad array of molecules, defined as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), is released (Figure 1). DAMPs are very heterogeneous molecules depending on injured cell and tissue types and comprise intracellular proteins (such as heat-shock proteins, HSPs, and high-mobility group box 1, HMGB1), proteins derived from the extracellular matrix (such as hyaluronan breakdown fragments) and non-protein molecules (such as uric acid and ATP). DAMPs can also be actively released by live cells undergoing life threatening stresses in order to signal their status to surrounding (immune) cells. As the PAMPs, DAMPs induce inflammatory processes activating the immune response through the stimulation of PRR (65–67). Thus, these molecules can be used by the organism to alert the immune system for damages induced by invading pathogens, as well as by other noxious agents or “internal” distress. Innate immune cells (neutrophils, macrophages, NK cells, and other cells) exert their first line protective functions and amplify the response by secreting chemokines, cytokines, and other inflammatory mediators. Inflammation promotes cell recruitment, maturation, and activation of the adaptive immune system cells (T and B lymphocytes) which carry out a potent antigen-specific immune response against pathogens (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Upon infection and/or tissue damage pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from microorganisms and damage-associated molecular patterns from injured cells alert the immune system. Stimulated innate immune cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, and NK cells, further amplify these danger signals secreting chemokines, cytokines, and other inflammatory mediators. The resulting inflammatory response sustains recruitment and activation of the adaptive immune system cells (T and B lymphocytes). Once an effective immune response is carried out, inflammation returns to homeostatic levels allowing tissue repair. Dysregulations in immune responses lead to chronic inflammation which may result in further tissue damage. Exposure to EMFs could modulate inflammatory responses by targeting, in different cell types, signal transduction pathways and/or molecules relevant to danger signals. Abbreviations: ARs, adenosine receptors; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; B, B cells; DC, dendritic cells; HMGB1, high mobility group box-1; HSP70, heat shock protein 70; NKs, natural killer cells; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps; ROS, reactive oxygen species; T, T cells.

Alterations in pathways regulating DAMPs generation and their effects can result in inflammatory/immune-mediated diseases. Inhibition of their action may, therefore, represent a therapeutic target in these diseases. Noteworthy, recent evidences revealed that DAMPs contribute to restore the equilibrium (homeostasis) playing an important role also in the promotion of tissue repair (67, 68). As schematized in Figure 1, in the following part of the review, we summarize findings on the effects of the exposure to EMFs on DAMPs, focusing mainly on those relevant to immunomodulation.

Heat-shock proteins are highly evolutionary conserved proteins that change their expression levels in response to heat shock, oxidative stress, anticancer drugs, or other stressful conditions [for recent review see Ref. (69)]. HSPs act as molecular chaperones involved in protein folding and transportation. Extracellular HSPs activate antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and take part in the induction of the adaptive immune response by carrying peptides for cross-presentation. HSPs have also been described to act as danger signals (likewise in the absence of pathogens) because, once released in the extracellular milieu during cell damage processes (necrosis), they are able to modulate PAMP-induced responses. As a result, they induce secretion of inflammatory cytokines in APCs, including dendritic cells and macrophages (70).

Not all of the HSPs have an activating, pro-inflammatory function. In some conditions, indeed low amounts of HSPs, such as HSP60, can downregulate adaptive immune responses to self-antigens by upregulating regulatory T (Treg) cell activity and consequently reducing T cell proliferation and counteracting autoimmunity (71). Whether EMFs might be used to induce low levels of HSPs to ameliorate autoimmune diseases has not been investigated. The modulatory role of HSP60 was recently confirmed in wound healing and tissue regeneration. Interestingly, the authors found that HSP60 induced M2 macrophages, a cell type involved in the control of inflammation and regenerative processes (72).

It has been shown that ELF-MF exposure induces HSP expression in mouse macrophages [50 Hz, 1.0 mT up to 24 h (11)] and also in the human leukemia cell line K562 [50 Hz, 0.025–0.10 mT, 1 h (13)]. The authors also detected a possible connection between reactive oxygen species (ROS) release and HSP expression after exposure to MFs (50 Hz, 0.10 mT, for 1 h), since scavengers inhibited the free radical production and the expression of HSP70. It has to be pointed out that none of these studies differentiated between intra and intercellular HSPs. Enhancement of production and HSP70 expression by ELF-MFs (50 Hz, 0.1 or 0.5 mT) were also confirmed in RAW264 cells (an Abelson murine leukemia virus transformed cell line used as a macrophage model) (15). However, in other studies, with exposure of HL-60, H9c2, and Girardi heart cells to lower intensity MF and/or for shorter periods [60 Hz, 6.3 or 8.0 µT, 20 min (14); 50 Hz, 2 µT–4 mT, 15 or 30 min (12)] no change in HSPs expression was detected.

HMGB1 is an archetypical danger signal (alarmin), involved in inflammation-induced tissue damage as well as in tissue repair (73). HMGB1 is released passively during cellular necrosis and actively secreted by inflammatory immune cells (monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells) and non-immune cells under stressful conditions (74–76). Oxidative stress-induced HMGB1 secretion is negatively regulated by HSP72 (77–80). Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of HMGB1 by PARP1 increases its potential as damage signal. Noteworthy, PARP1 activation is induced by DNA damage and by oxidative stress, and leads to stimulation of inflammation and immune responses (81). In spite of several publications describing the effects of ELF-MFs on oxidative stress and HSPs, no studies reported data on HMGB1 or PARP.

Uric acid is a product of the purine metabolic pathway released by damaged cells and acting as an endogenous danger signal. Uric acid triggers NOD-like receptor protein 3-dependent inflammation, with important implications for systemic inflammatory responses. There are few studies that have measured uric acid in the context of ELF exposure. In human male volunteers, Selmaoui et al. evaluated the effects of acute exposure to both continuous and intermittent EMFs (50 Hz, 10 µT) on the circadian rhythm and on clinical chemistry variables, including uric acid, and found no significant differences between exposed and sham-exposed groups (17). Surprisingly, St-Pierre and colleagues have shown that adult rats prenatally exposed to EMFs [frequency-modulated or sequences of short-pulsed (200 ms) MF, 5 nT–1.2 μT] exhibited high levels of uric acid in addition to various abnormalities of the hippocampus (18). Apart from the fact that the previously discussed publications report different types of EMFs exposures, transient alterations on circulating uric acid levels may reveal damage signals in the form of tissue relevant effects.

Elevated extracellular ATP concentrations represent a damage signal that works as a chemoattractant, induces release of inflammatory cytokines and activates the expression of ectonucleotidases, which rapidly break down ATP to adenosine (82, 83). Adenosine is involved in both upregulation of inflammatory responses and their down-modulation, confirming the dual role of DAMPs-activated pathways in stimulation and control of immune responses. The outcome of the adenosine rise depends on the repertoire of adenosine receptors (ARs) expressed by the targeted cells. Virtually all of the innate and adaptive immune cells, as well as many other cell types, express ARs. Whereas A1 and A3 ARs inhibit adenylate cyclase activity and, therefore, decrease cAMP production, stimulation of A2A and A2B ARs increase cAMP accumulation (84). The cAMP is a potent negative regulator of innate and adaptive immune cells, including effector T cells (85). It induces the expression of CTLA-4, a receptor negatively regulating T cell functions (86, 87), promotes differentiation of regulatory/suppressive T cells and secretion of inhibitory cytokines (88).

There are strong evidences that low-frequency, low-energy PEMFs exert an anti-inflammatory effect through the upregulation of A2A and A3 ARs, leading to a reduction in the expression of inflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-8) [(89) and references herein]. PEMF-induced upregulation of A2A receptor occurs in different cell types and tissues, including neuronal cells, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes [reviewed in Ref. (90)]. Neutrophils exposed to PEMFs (pulse length 1.3 ms, 75 Hz replication rate, 24 h, 0.2–3.5 mT) showed significant increase in A2A receptor signaling and in the capability, upon treatment with adenosine agonists, to inhibit the generation of the superoxide anion (19). Of particular interest for the control of ischemic injury are the inhibitory effects of PEMF exposure on hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) expression in microglia cells (41). Indeed, activation of microglia cells during ischemia and reperfusion leads to amplification of danger signals with subsequent strong inflammatory responses that largely contribute to tissue damage. Inhibition of the PGE2 (prostaglandin E2) and cycloxigenase-2 (COX2) pathways, with consequent reduction in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8) and an increase in anti-inflammatory factors (cAMP, IL-10), was also observed in synovial fibroblasts from bovine and osteoarthritis patients (10, 16).

Evidence from the literature thus shows that both ELF-MFs and PEMFs can affect signals associated with damage generally resulting in anti-inflammatory effects. Yet, information on the effects of ELF-MFs and PEMFs on some key damage/danger-associated molecules relevant to immunomodulation, such as HMGB1 and uric acid, is still lacking.

Danger signals may be released by any damaged tissue cell and result in the expression or release of other inflammatory factors by tissue cells and innate immune cells. Innate immune cells represent the first line of defense against pathogens and can actively secrete further danger/activating factors. While producing their response, innate immune cells prepare the context for the activation of the adaptive immune response, which involves antigen-specific receptor-bearing T and B cells. It is, therefore, of interest to consider whether the exposure to EMFs may affect innate immune cells, directly or indirectly through the effects on danger signals or other mechanisms.

Natural killer cells (NK) are considered innate immune cells as they express germ-line encoded inhibitory and activating receptors, many in a stochastic way (91). But, they also exhibit characteristics of adaptive immune cells such as the ability to mount enhanced secondary responses to cognate antigenic challenge, revealing their capability to generate memory responses (92). The diversity in pattern expression of NK cells allowed the identification of different subsets performing distinct functions. One of the main tasks of NK cells is to eliminate infected or transformed cells by direct cytolysis or by secreting immune mediators that regulate T cell, neutrophil, and macrophage activation and migration to the injured sites. Thus, altered function of NK cells may strongly impact infection and tumor clearance.

Studies in animal models showed that, in particular experimental settings, exposure to EMFs (60 Hz, 1 mT, continuous, 13 weeks) leads to a reduction or, in more extreme cases to the suppression, of NK activity. Unfortunately, none of these studies demonstrated that short- or long-term exposure to ELF-EMFs would compromise survival upon challenge with an infectious agent or tumor cells in animals whose NK cell function was reduced or lost (26, 27). It is, therefore, difficult to conclude the actual impact on health of these findings. It remains to be addressed if chronic exposure to ELF-EMF would affect cytokine/chemokine production by NK cells and how possible alterations in these soluble factors would interfere with functions of T cells and dendritic cells.

Studies in humans focused mainly on NK cell counts in occupationally exposed subjects (see Table 1) with contrasting results. Some authors observed an increase (20, 21, 29), others a decrease (22–24, 28) of peripheral blood NK cells after ELF-EMF exposure. A study (25) reported the effects of ELF-EMF on NK activity in a group of 52 occupationally exposed workers. Individuals were stratified according to the ELF-EMF exposure dose in low (<0.2 μT) and high (>0.2 μT) exposed workers and NK function assessed as an ability to lyse target cells. Highly exposed workers showed no differences in peripheral blood NK cell number, but a reduction in their lytic capacity compared with low exposed workers. The biological significance of these changes remains to be elucidated.

Neutrophils play pivotal roles in recognition, phagocytosis, and eradication of pathogens. Neutrophils, with their wide range of PRR, are able to sense danger and, with their chemotactic receptors, quickly migrate into the sites of injury or infection (93–95). Through the secretion of cytokines and chemokines, neutrophils are able to orchestrate both immune and inflammatory responses. During their action against pathogens, neutrophils may damage tissues, but also support resolution of inflammation and healing of injured tissues (96–98). In addition to the traditional phagocytic function, neutrophils may fight against microbes by delivering granules with enzymatic functions (99) and by what has been defined as neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) (100). NETs are extracellular traps that capture and destroy extracellular microbes and are constituted by a backbone of nuclear decondensed chromatin mixed with neutrophil-derived antimicrobial proteins. The generation of NET results, for the neutrophil, in a unique form of cell death called NETosis followed by phagocytosis by macrophages (101). NETs are double-edged swords: on one side they limit infection; on the other side they expose self-DNA and intracellular proteins, potentially exposing the organism to the risk of developing autoimmunity and inflammatory diseases (102).

The role that neutrophils play in immune response, their high reactivity, mobility, and sensitivity make them putative targets for investigating possible cell modulation effects by ELF-EMF exposure. The first study investigating ELF-EMF impact on NET formation, ex vivo, was performed by the group of Golbach et al. and showed that ELF-EMF (multifrequency “Immunent” signal; 300 µT; 1–4 h) alone was unable to induce NETs (32). However, the ELF-EMF was able to significantly enhance NET formation in freshly isolated peripheral blood neutrophils that were pre-activated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA). In fact, PMA is a potent activator of NADPH oxidase that triggers the generation of ROS, which are key elements for the induction of NET. ROS is needed for the dissociation of peptide complexes containing neutrophil-derived antimicrobial proteins. Golbach et al. by using selective pharmacological oxidase inhibitors demonstrated that the NADPH pathway is critical for ELF-EMF-enhanced NET formation, possibly by increasing ROS production (32).

Several groups suggested that ELF-EMFs may affect calcium homeostasis and thus interfere in different ways in cell function, depending on the ELF-EMF targeted cell [reviewed in Ref. (103)]. In the case of neutrophils, studies using human promyelocytic cell lines differentiated into neutrophils have shown that an in vitro exposure to a 50 Hz sine wave or an “Immunent” signal at an environmentally relevant magnetic flux density of 5 µT or peak 500 µT was not altering the levels of calcium signaling (30). Gene expression patterns of calcium-signaling related genes, cell morphology, as well as the presence of intracellular microvilli were not changed by the MF in either HL-60 or PLB-985 cell lines (31). Thus, under this particular experimental condition, type of ELF-EMF exposure and type of cell lines analyzed, ELF-EMF exposure seems not to interfere with calcium homeostasis in neutrophils.

Macrophages are cells differentiated from monocytes that left blood circulation and entered tissues, where they work as actuators and regulators of inflammatory processes as well as of innate and adaptive immune responses (104). Macrophages can be activated by the classical (M1 macrophages) or the alternative (M2 macrophages) pathway, resulting in cells producing pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory factors, respectively. M1 cells are induced by interferon-γ (IFN-γ), LPS, or endogenous danger signals and produce large amounts of TNF, IL-6, IL-12, and ROS. M2 cells are activated by Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-10, or IL-13 and act as anti-inflammatory cells. These cells produce low level oxygen intermediates, polyamines and prolines, which induce proliferation and collagen production. The M2 cells are involved in resolving inflammation, increase fibrogenesis, and activate tissue repair and wound healing (105–107). However, while M1- and M2-type factors are relevant elements to define a different activation status of macrophages, the physiological picture might be more complex. Indeed, macrophages do not appear committed to either an entirely inflammatory or an anti-inflammatory expression pattern with some M1 and M2 markers displaying variable expression (108).

Several studies showed that free radical homeostasis is influenced by ELF-EMFs (5, 6, 109, 110). Some in vivo studies showed that ELF-MF exposure using different intensities [from 4 mT (PEMF) to 7 mT], time schedules (single or repetitive), and durations (min to days) influence the redox homeostatic system toward a pro-oxidative shift [for reviews see Ref. (110, 111)]. This oxidative stress is very mild, thus no or very moderate cellular/tissue damages, such as lipid peroxidation were detected. However, Lupke and co-workers suggested that ELF-MFs (50 Hz, 1.0 mT, 45 min) would affect immune cells by membrane-associated components leading to moderate ROS release and changes in radical homeostasis. This, in turn, causes down-stream events, including changes in gene expression leading to the activation of the alternative pathway in human monocytes and in a macrophage cell line (37). Under similar MF-exposure conditions (50 Hz, 1.0 mT, different time points), Frahm et al. showed in mouse primary bone marrow-derived macrophages an effect on the expression of redox regulatory proteins associated with increased levels of ROS (11) and IL-1β production (34). Changes in redox status and differentiation were also found in neuroblastoma cells (human SH-SY5Y cell line) after short-term MF-exposure (50 Hz MF; 1.0 mT; up to 96 h) (33). The authors detected modulations of the redox status of the cells, without any oxidative damage, by a positive modulation of antioxidant enzyme expression and a significant increase in GSH (glutathione) levels. It seems that MFs (from 0.025 mT and higher) activate cell systems to release moderate amounts of free radicals via the alternative pathway that can lead to the consumption of the intracellular antioxidants. In general, pro-inflammatory factors are downregulated and anti-inflammatory cytokines are upregulated as a result of the moderate oxidative stress induced by MF exposure.

With the aim to investigate the potential for PEMFs to downregulate markers of inflammation expressed by macrophages, Ross and Harrison (38) exposed LPS-activated murine RAW 264.7 macrophages to a square-wave pulsed MF at 0.4 mT. The authors found a statistically significant decrease in the levels of LPS-induced TNF-α and NFκB activation after exposure to 5.1 Hz PEMF, but not at other frequencies (investigated range: 5.1–30 Hz). Unfortunately, this work suffers from partly insufficient description of the exposure conditions and dosimetry and of a large inter-experimental variation for some parameters. Further studies could shed some light on these issues. A reduction in the expression of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and TNF) was also observed in PBMC-derived fibroblast-like cells (35) exposed to PEMFs (50 Hz burst frequency; 2.25 mT, 15 min on days 7, 8, and 9 of culture), concomitant with an increase in IL-10 production. In another study (36), the effects of 45 mT PEMF were investigated on cytokine production in PBMC from healthy donors and from Crohn’s disease (CD) patients. Exposed and stimulated PBMCs from CD patients showed a decrease in IFN-γ and an increase in IL-10 production, whereas PEMF-exposure had minimal effect on PBMCs from controls.

Of some interest, for the long in vivo exposure period, is the work by Salehi et al. (39), which was performed using male Wistar rats exposed to a 50 Hz sine wave MF (100 µT, 2 h/day, 3 months). There were no effects on body or tissue weight. No effects were found on IFN-γ (a Th1 type cytokine) or IL-4 (a Th2 type) in either serum concentration or supernatants from whole spleen PHA-stimulated cell cultures. A reduction of IL-12 (a Th1-inducing cytokine) concentration in serum, but not in culture supernatants, was reported. Conversely, an increase in IL-6 (an inflammatory cytokine) production by ex vivo stimulated spleen cells was observed (but no effects on serum IL-6 concentration). No data were shown on cytokines properly definable as Th17 type. Thus, the authors’ conclusion that ELF-EMFs would downregulate Th1 responses and upregulate Th17 responses is not sustained by the data shown. What cell type was affected by EMF exposure remains undetermined.

The effects of acute exposure to a 50 Hz MF (10 µT) on male volunteers were investigated by Selmaoui et al. (40). Subjects were exposed or sham-exposed at two separate 24 h periods for 9 h during night. The ELF-EMF was either continuous or intermittent (1 h on, 1 h off). Intermittent exposure caused increased levels of IL-6, whereas all the other exposure conditions did not affect IL-6 expression as well as the cytokines and cytokine receptors.

Overall, even if there are some contradictory results especially on the effects on NK cells, several studies show a potential anti-inflammatory effect of the exposure to ELF-EMFs and PEMFs. In macrophages, the reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines induced by ELF-EMFs is associated with the activation of regulatory mechanisms induced by a moderate oxidative stress. However, in the case of neutrophils, activation of oxidative stress by ELF-EMFs induces activation of NETosis, an effect that might result in a more effective response and, therefore, in the limitation of the inflammatory burden over time. This interesting aspect needs confirmation before any definitive conclusion can be drawn.

Wound healing is a very complex process comprising a series of events from initial bleeding and coagulation (hemostasis), to acute inflammation with cell recruitment, proliferation of connective tissue and parenchymal cells, synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins, and finally wound remodeling. The immune cells play a relevant role in all the processes from initial inflammation until tissue remodeling (112, 113). Upon activation, platelets generate the cloth and release several factors which, together with DAMPs from damaged cells and PAMPs from microorganisms, induce an intense inflammatory response. As discussed above, danger signals not only promote inflammation but they also activate processes leading to downregulation of immune responses. This is a very important feature, as control of inflammation is required for tissue regeneration. Alterations in these critical steps result in non-healing ulcers with self-sustaining chronic inflammation as it occurs in some diseases, including neuropathy, ischemia, venous hypertension, diabetes, decubitus, and others (113).

Findings discussed above on the effects of ELFs and PEMFs on inflammation suggest that EMFs could be effective in promoting tissue repair. Indeed, several studies described positive outcomes of EMF exposure in wound healing in both animal models and humans [for review see Ref. (114–116)]. During the initial phases of wound healing, neutrophils and pro-inflammatory M1 type macrophages play a crucial role in the protection from pathogens and in the clearance of cell debris. As already mentioned, exposure of neutrophils to PEMFs promotes the formation of NETs and NETosis ex vivo (32), an effect that could potentiate the initial response. Removal of pathogens through an effective action of neutrophils, followed by clearance of dead neutrophils by macrophages, is a prerequisite for the subsequent control of inflammation and repair phases. A switch of M1 to M2 type macrophages (the latter expressing anti-inflammatory and repair-promoting factors) could be promoted by the exposure to ELF-EMF. As discussed above (34, 37), ELF-EMF can modulate ROS in macrophages (and neutrophils) favoring M2 type activation. Low concentrations of ROS may also support healing through promotion of angiogenesis (117). In diabetic mice, exposure to PEMFs (15 Hz; 4 ms pulse length; max 1.2 mT during pulse; exposure up to 14 days) resulted in a faster wound healing associated with an increase in angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and production of fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2). In this model, FGF-2 was also able to prevent tissue necrosis in response to ischemic insult, suggesting that non-invasive angiogenic stimulation by PEMFs might be useful in preventing ulcer formation in diabetic patients (42). Effects on angiogenesis were also found in vitro in human endothelial cells exposed to ELF-EMF (sinewave MF; 50 Hz; 1 mT; up to 12 h), with an increase in the expression of VEGF receptor, cell proliferation, and tubule formation (45). Several studies done in rats showed that treatment with PEMFs (20–25 Hz, 0.04/0.4 ms, 4–8 mT, 1 h/day) accelerated wound reduction, enhanced recruitment of myofibroblastic cells, increased collagen fibers and tensile strength, and promoted re-epithelialization in normoglycemic as well as in diabetic animals (43, 44, 46). However, another study did not find effects on skin wound healing in rats exposed to a 5 Hz PEMF with 12.5 mT flux density (52).

Effects of the exposure to ELF-EMF are not confined to innate immune cells. Lee et al. (50) showed that both Th17-type cytokine production and Treg cell differentiation are upregulated in human CD4 cells exposed to 60 Hz 0.3 mT EMF. Noteworthy, Th17 cells play a critical role not only in host defense but also in tissue regeneration, including skin and mucosa (118), whereas Treg cells are deputed to the negative control of immune responses and are required for the maintenance of immune tolerance (119).

Application of PEMFs to the skin was used in various clinical conditions. Reduction in wound healing time and rate of recurrence of chronic venous leg ulcers were described in two randomized double-blinded studies [1.3 ms pulse; max flux density 2.8 mT; up to 90 days (48); 2.2 mT; 3.5 ms pulse; weeks (56)], with beneficial effects and pain reduction lasting beyond the period of treatment. However, in another study, no statistically significant effects were found in healing time of ulcers or pain perception (120). More recently, a reduction of pain and wound inflammation in women undergoing cesarean surgery was reported (49). No adverse effects were observed in any of the studies (47, 48, 56, 120). Although all these in vivo studies and clinical observations showed positive results, the real picture is more complex because there is still a fraction of patients that does not respond with improved healing. Several in vitro studies, using cell lines or ex vivo isolated cells, showed that sensitivity to EMF varies with cell type. In fact, fibroblasts seem to respond better to ELF-EMF of 20 Hz and 6–8 mT (51, 55) whereas keratinocytes (53, 57), monocytes (54), macrophages, and endothelial cells (42, 45) are sensitive to EMF of 50 Hz and 1 mT. Thus, different chronic ulcers, probably depending on their origin, may require different ELF-EMF exposure parameters in order to improve healing.

Potential use of ELF-EMF and PEMFs as modulator of immune responses alone or in combination with pharmacological therapies represents a novel frontier of investigation with interesting clinical perspectives. As discussed above, danger signals stimulate an immune response, but also activate mechanisms that (later on) will negatively regulate immune cell activation. There seems to be a potential for modulation of danger signals by ELF-MF and PEMFs leading to reduced inflammation (as shown in Figure 1) and promotion of healing processes as indicated by several publications. Mechanisms are not well characterized, but they seem to include increased ROS production and increased expression of certain HSPs for ELF-MFs while PEMFs seem to control inflammation by upregulating ARs pathways. Noteworthy, these pathways are involved in any inflammatory condition and, therefore, they might represent relevant therapeutic targets in several (chronic) inflammatory diseases.

Whereas the majority of the in vitro studies focused on monocytes/macrophages and fibroblasts, the effects of the exposure to EMF on other cell types are not well defined. In macrophages, the reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines induced by ELF-EMF is associated with the activation of regulatory mechanisms induced by a moderate oxidative stress. However, in the case of neutrophils, activation of oxidative stress by ELF-EMF induces activation of NETosis. A better characterization of the effects on neutrophils would be relevant for the treatment of wounds characterized by the presence of infections. Furthermore, studies should also be extended to other key damage/danger-associated molecules to better understand the relations between EMF exposure, oxidative stress, and immune-modulation associated with (wound) healing. Lack of data on Langerhans cells, the skin-specialized dendritic cells, should also be addressed considering their local role in antigen uptake and stimulation of immune responses.

Understanding whether differences in the effects depend on specific exposure parameters or more on targeted cell types, as well as underlying mechanisms, is necessary for possible therapeutic purposes. Addressing this issue needs systematic and comparative studies, where the dependency on waveforms, modulations, frequencies, flux densities, and exposure durations are investigated. Moreover, in order to draw conclusions on possible mechanisms, considering the redundancy of the immune system, studies should always consider the effects on upstream and downstream elements of the investigated pathway rather than just one or two parameters.

Wound healing promoted by EMF in certain patient groups, possibly combined with pharmacological treatments seem to be the most promising area for further studies. However, as discussed above, not all patients experienced a therapeutic effect by the exposure to EMF in wound healing. This observation suggests that for wound healing, EMF could be effective only in some specific types of wounds. ELF-EMFs and PEMFs, by acting through ROS and adenosine pathways, respectively, could thus be suitable for wounds of different origins. Large clinical studies, with well-defined criteria for inclusion of patients, together with experimental studies could shed some light on all these aspects.

MR, MS, M-OM, and CP designed the review manuscript structure, drafted, revised, and approved the version to be published as well as agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

The authors declare that the review was written in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was partially supported by COST EMF-MED Action (BM1309), European network for innovative uses of EMFs in biomedical applications.

1. Burns-Naas LA, Jean Meade B, Munson AE. Toxic responses of the immune system. 6 ed. In: Klaassen CD, editor. Casarett & Doulss’s Toxicology. The Basic Science of Poisons. Chicago, USA: McGraw-Hill (2001). p. 419–70.

2. Frasca D, Pioli C, Guidi F, Pucci S, Arbitrio M, Leter G, et al. IL-11 synergizes with IL-3 in promoting the recovery of the immune system after irradiation. Int Immunol (1996) 8(11):1651–7. doi:10.1093/intimm/8.11.1651

3. Rouse BT, Sehrawat S. Immunity and immunopathology to viruses: what decides the outcome? Nat Rev Immunol (2010) 10(7):514–26. doi:10.1038/nri2802

4. Dietert RR, Piepenbrink MS. The managed immune system: protecting the womb to delay the tomb. Hum Exp Toxicol (2008) 27(2):129–34. doi:10.1177/0960327108090753

5. Santini MT, Rainaldi G, Indovina PL. Cellular effects of extremely low frequency (ELF) electromagnetic fields. Int J Radiat Biol (2009) 85(4):294–313. doi:10.1080/09553000902781097

6. Simko M, Mattsson MO. Extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields as effectors of cellular responses in vitro: possible immune cell activation. J Cell Biochem (2004) 93(1):83–92. doi:10.1002/jcb.20198

7. Boscolo P, Di Gioacchino M, Di Giampaolo L, Antonucci A, Di Luzio S. Combined effects of electromagnetic fields on immune and nervous responses. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol (2007) 20(2 Suppl 2):59–63. doi:10.1177/03946320070200S212

8. Jauchem JR. Effects of low-level radio-frequency (3kHz to 300GHz) energy on human cardiovascular, reproductive, immune, and other systems: a review of the recent literature. Int J Hyg Environ Health (2008) 211(1–2):1–29. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2007.05.001

9. Guerriero F, Ricevuti G. Extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields stimulation modulates autoimmunity and immune responses: a possible immuno-modulatory therapeutic effect in neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen Res (2014) 11(12):1888–95. doi:10.4103/1673-5374.195277

10. De Mattei M, Varani K, Masieri FF, Pellati A, Ongaro A, Fini M, et al. Adenosine analogs and electromagnetic fields inhibit prostaglandin E2 release in bovine synovial fibroblasts. Osteoarthritis Cartilage (2009) 17(2):252–62. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.002

11. Frahm J, Mattsson MO, Simko M. Exposure to ELF magnetic fields modulate redox related protein expression in mouse macrophages. Toxicol Lett (2010) 192(3):330–6. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.11.010

12. Gottwald E, Sontag W, Lahni B, Weibezahn K-F. Expression of HSP72 after ELF-EMF exposure in three cell lines. Bioelectromagnetics (2007) 28(7):509–18. doi:10.1002/bem.20327

13. Mannerling AC, Simko M, Mild KH, Mattsson MO. Effects of 50-Hz magnetic field exposure on superoxide radical anion formation and HSP70 induction in human K562 cells. Radiat Environ Biophys (2010) 49(4):731–41. doi:10.1007/s00411-010-0306-0

14. Morehouse CA, Owen RD. Exposure to low-frequency electromagnetic fields does not alter HSP70 expression or HSF-HSE binding in HL60 cells. Radiat Res (2000) 153(5):658–62. doi:10.1667/0033-7587(2000)153[0658:ETLFEF]2.0.CO;2

15. Pooam M, Nakayama M, Nishigaki C, Miyata H. Effect of 50-Hz sinusoidal magnetic field on the production of superoxide anion and the expression of heat-shock protein 70 in RAW264 Cells. Int J Chem (2017) 9(2):23–36. doi:10.5539/ijc.v9n2p23

16. Ongaro A, Varani K, Masieri FF, Pellati A, Massari L, Cadossi R, et al. Electromagnetic fields (EMFs) and adenosine receptors modulate prostaglandin E(2) and cytokine release in human osteoarthritic synovial fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol (2012) 227(6):2461–9. doi:10.1002/jcp.22981

17. Selmaoui B, Lambrozo J, Touitou Y. Assessment of the effects of nocturnal exposure to 50-Hz magnetic fields on the human circadian system. A comprehensive study of biochemical variables. Chronobiol Int (1999) 16(6):789–810. doi:10.3109/07420529909016946

18. St-Pierre LS, Mazzuchin A, Persinger MA. Altered blood chemistry and hippocampal histomorphology in adult rats following prenatal exposure to physiologically-patterned, weak (50–500 nanoTesla range) magnetic fields. Int J Radiat Biol (2008) 84(4):325–35. doi:10.1080/09553000801953300

19. Varani K, Gessi S, Merighi S, Iannotta V, Cattabriga E, Spisani S, et al. Effect of low frequency electromagnetic fields on A2A adenosine receptors in human neutrophils. Br J Pharmacol (2002) 136(1):57–66. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0704695

20. Bonhomme-Faivre L, Marion S, Bezie Y, Auclair H, Fredj G, Hommeau C. Study of human neurovegetative and hematologic effects of environmental low-frequency (50-Hz) electromagnetic fields produced by transformers. Arch Environ Health (1998) 53(2):87–92. doi:10.1080/00039896.1998.10545968

21. Bonhomme-Faivre L, Marion S, Forestier F, Santini R, Auclair H. Effects of electromagnetic fields on the immune systems of occupationally exposed humans and mice. Arch Environ Health (2003) 58(11):712–7. doi:10.3200/AEOH.58.11.712-717

22. Boscolo P, Bergamaschi A, Di Sciascio MB, Benvenuti F, Reale M, Di Stefano F, et al. Effects of low frequency electromagnetic fields on expression of lymphocyte subsets and production of cytokines of men and women employed in a museum. Sci Total Environ (2001) 270(1–3):13–20. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(00)00796-8

23. Del Signore A, Boscolo P, Kouri S, Di Martino G, Giuliano G. Combined effects of traffic and electromagnetic fields on the immune system of fertile atopic women. Ind Health (2000) 38(3):294–300. doi:10.2486/indhealth.38.294

24. Di Giampaolo L, Di Donato A, Antonucci A, Paiardini G, Travaglini P, Spagnoli G, et al. Follow up study on the immune response to low frequency electromagnetic fields in men and women working in a museum. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol (2006) 19(4 Suppl):37–42.

25. Gobba F, Bargellini A, Scaringi M, Bravo G, Borella P. Extremely low frequency-magnetic fields (ELF-EMF) occupational exposure and natural killer activity in peripheral blood lymphocytes. Sci Total Environ (2009) 407(3):1218–23. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.08.012

26. House RV, McCormick DL. Modulation of natural killer cell function after exposure to 60 Hz magnetic fields: confirmation of the effect in mature B6C3F1 mice. Radiat Res (2000) 153(5 Pt 2):722–4. doi:10.1667/0033-7587(2000)153[0722:MONKCF]2.0.CO;2

27. House RV, Ratajczak HV, Gauger JR, Johnson TR, Thomas PT, McCormick DL. Immune function and host defense in rodents exposed to 60-Hz magnetic fields. Fundam Appl Toxicol (1996) 34(2):228–39. doi:10.1006/faat.1996.0192

28. Ichinose TY, Burch JB, Noonan CW, Yost MG, Keefe TJ, Bachand A, et al. Immune markers and ornithine decarboxylase activity among electric utility workers. J Occup Environ Med (2004) 46(2):104–12. doi:10.1097/01.jom.0000111963.64211.3b

29. Tuschl H, Neubauer G, Schmid G, Weber E, Winker N. Occupational exposure to static, ELF, VF and VLF magnetic fields and immune parameters. Int J Occup Med Environ Health (2000) 13(1):39–50.

30. Bouwens M, de Kleijn S, Ferwerda G, Cuppen JJ, Savelkoul HF, Kemenade BM. Low-frequency electromagnetic fields do not alter responses of inflammatory genes and proteins in human monocytes and immune cell lines. Bioelectromagnetics (2012) 33(3):226–37. doi:10.1002/bem.20695

31. Golbach LA, Philippi JG, Cuppen JJ, Savelkoul HF, Verburg-van Kemenade BM. Calcium signalling in human neutrophil cell lines is not affected by low-frequency electromagnetic fields. Bioelectromagnetics (2015) 36(6):430–43. doi:10.1002/bem.21924

32. Golbach LA, Scheer MH, Cuppen JJ, Savelkoul H, Verburg-van Kemenade BM. Low-Frequency electromagnetic field exposure enhances extracellular trap formation by human neutrophils through the NADPH pathway. J Innate Immun (2015) 7(5):459–65. doi:10.1159/000380764

33. Falone S, Grossi MR, Cinque B, D’Angelo B, Tettamanti E, Cimini A, et al. Fifty hertz extremely low-frequency electromagnetic field causes changes in redox and differentiative status in neuroblastoma cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol (2007) 39(11):2093–106. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2007.06.001

34. Frahm J, Lantow M, Lupke M, Weiss DG, Simko M. Alteration in cellular functions in mouse macrophages after exposure to 50 Hz magnetic fields. J Cell Biochem (2006) 99(1):168–77. doi:10.1002/jcb.20920

35. Gomez-Ochoa I, Gomez-Ochoa P, Gomez-Casal F, Cativiela E, Larrad-Mur L. Pulsed electromagnetic fields decrease proinflammatory cytokine secretion (IL-1beta and TNF-alpha) on human fibroblast-like cell culture. Rheumatol Int (2011) 31(10):1283–9. doi:10.1007/s00296-010-1488-0

36. Kaszuba-Zwoinska J, Ciecko-Michalska I, Madroszkiewicz D, Mach T, Slodowska-Hajduk Z, Rokita E, et al. Magnetic field anti-inflammatory effects in Crohn’s disease depends upon viability and cytokine profile of the immune competent cells. J Physiol Pharmacol (2008) 59(1):177–87.

37. Lupke M, Rollwitz J, Simko M. Cell activating capacity of 50 Hz magnetic fields to release reactive oxygen intermediates in human umbilical cord blood-derived monocytes and in Mono Mac 6 cells. Free Radic Res (2004) 38(9):985–93. doi:10.1080/10715760400000968

38. Ross CL, Harrison BS. Effect of pulsed electromagnetic field on inflammatory pathway markers in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. J Inflamm Res (2013) 6:45–51. doi:10.2147/JIR.S40269

39. Salehi I, Sani KG, Zamani A. Exposure of rats to extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields (ELF-EMF) alters cytokines production. Electromagn Biol Med (2013) 32(1):1–8. doi:10.3109/15368378.2012.692343

40. Selmaoui B, Lambrozo J, Sackett-Lundeen L, Haus E, Touitou Y. Acute exposure to 50-Hz magnetic fields increases interleukin-6 in young healthy men. J Clin Immunol (2011) 31(6):1105–11. doi:10.1007/s10875-011-9558-y

41. Vincenzi F, Ravani A, Pasquini S, Merighi S, Gessi S, Setti S, et al. Pulsed electromagnetic field exposure reduces hypoxia and inflammation damage in neuron-like and microglial cells. J Cell Physiol (2017) 232(5):1200–8. doi:10.1002/jcp.25606

42. Callaghan MJ, Chang EI, Seiser N, Aarabi S, Ghali S, Kinnucan ER, et al. Pulsed electromagnetic fields accelerate normal and diabetic wound healing by increasing endogenous FGF-2 release. Plast Reconstr Surg (2008) 121(1):130–41. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000293761.27219.84

43. Cheing GL, Li X, Huang L, Kwan RL, Cheung KK. Pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF) promote early wound healing and myofibroblast proliferation in diabetic rats. Bioelectromagnetics (2014) 35(3):161–9. doi:10.1002/bem.21832

44. Choi MC, Cheung KK, Li X, Cheing GL. Pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) promotes collagen fibre deposition associated with increased myofibroblast population in the early healing phase of diabetic wound. Arch Dermatol Res (2016) 308(1):21–9. doi:10.1007/s00403-015-1604-9

45. Delle Monache S, Alessandro R, Iorio R, Gualtieri G, Colonna R. Extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields (ELF-EMFs) induce in vitro angiogenesis process in human endothelial cells. Bioelectromagnetics (2008) 29(8):640–8. doi:10.1002/bem.20430

46. Goudarzi I, Hajizadeh S, Salmani ME, Abrari K. Pulsed electromagnetic fields accelerate wound healing in the skin of diabetic rats. Bioelectromagnetics (2010) 31(4):318–23. doi:10.1002/bem.20567

47. Guerriero F, Botarelli E, Mele G, Polo L, Zoncu D, Renati P, et al. Effectiveness of an innovative pulsed electromagnetic fields stimulation in healing of untreatable skin ulcers in the frail elderly: two case reports. Case Rep Dermatol Med (2015) 2015:576580. doi:10.1155/2015/576580

48. Ieran M, Zaffuto S, Bagnacani M, Annovi M, Moratti A, Cadossi R. Effect of low frequency pulsing electromagnetic fields on skin ulcers of venous origin in humans: a double-blind study. J Orthop Res (1990) 8(2):276–82. doi:10.1002/jor.1100080217

49. Khooshideh M, Latifi Rostami SS, Sheikh M, Ghorbani Yekta B, Shahriari A. Pulsed Electromagnetic fields for postsurgical pain management in women undergoing cesarean section: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin J Pain (2017) 33(2):142–7. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000376

50. Lee YJ, Hyung KE, Yoo JS, Jang YW, Kim SJ, Lee DI, et al. Effects of exposure to extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields on the differentiation of Th17 T cells and regulatory T cells. Gen Physiol Biophys (2016) 35(4):487–95. doi:10.4149/gpb_2016011

51. Loschinger M, Thumm S, Hammerle H, Rodemann HP. Induction of intracellular calcium oscillations in human skin fibroblast populations by sinusoidal extremely low-frequency magnetic fields (20 Hz, 8 mT) is dependent on the differentiation state of the single cell. Radiat Res (1999) 151(2):195–200. doi:10.2307/3579770

52. Milgram J, Shahar R, Levin-Harrus T, Kass P. The effect of short, high intensity magnetic field pulses on the healing of skin wounds in rats. Bioelectromagnetics (2004) 25(4):271–7. doi:10.1002/bem.10194

53. Patruno A, Amerio P, Pesce M, Vianale G, Di Luzio S, Tulli A, et al. Extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields modulate expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase, endothelial nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in the human keratinocyte cell line HaCat: potential therapeutic effects in wound healing. Br J Dermatol (2010) 162(2):258–66. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09527.x

54. Reale M, De Lutiis MA, Patruno A, Speranza L, Felaco M, Grilli A, et al. Modulation of MCP-1 and iNOS by 50-Hz sinusoidal electromagnetic field. Nitric Oxide (2006) 15(1):50–7. doi:10.1016/j.niox.2005.11.010

55. Rodemann HP, Bayreuther K, Pfleiderer G. The differentiation of normal and transformed human fibroblasts in vitro is influenced by electromagnetic fields. Exp Cell Res (1989) 182(2):610–21. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(89)90263-2

56. Stiller MJ, Pak GH, Shupack JL, Thaler S, Kenny C, Jondreau L. A portable pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) device to enhance healing of recalcitrant venous ulcers: a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Br J Dermatol (1992) 127(2):147–54. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb08047.x

57. Vianale G, Reale M, Amerio P, Stefanachi M, Di Luzio S, Muraro R. Extremely low frequency electromagnetic field enhances human keratinocyte cell growth and decreases proinflammatory chemokine production. Br J Dermatol (2008) 158(6):1189–96. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08540.x

59. Doherty PC, Zinkernagel RM. A biological role for the major histocompatibility antigens. Lancet (1975) 1(7922):1406–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(75)92610-0

60. Janeway CA Jr. The immune system evolved to discriminate infectious nonself from noninfectious self. Immunol Today (1992) 13(1):11–6. doi:10.1016/0167-5699(92)90198-G

61. Janeway CA Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol (2002) 20:197–216. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359

62. Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell (2006) 124(4):783–801. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015

63. Matzinger P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu Rev Immunol (1994) 12:991–1045. doi:10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.005015

64. Matzinger P. The danger model: a renewed sense of self. Science (2002) 296(5566):301–5. doi:10.1126/science.1071059

65. Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, Obeid M, Ortiz C, Criollo A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med (2007) 13(9):1050–9. doi:10.1038/nm1622

66. Tian J, Avalos AM, Mao SY, Chen B, Senthil K, Wu H, et al. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat Immunol (2007) 8(5):487–96. doi:10.1038/ni1457

67. Venereau E, Ceriotti C, Bianchi ME. DAMPs from cell death to new life. Front Immunol (2015) 6:422. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00422

68. Anders HJ, Schaefer L. Beyond tissue injury-damage-associated molecular patterns, toll-like receptors, and inflammasomes also drive regeneration and fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol (2014) 25(7):1387–400. doi:10.1681/asn.2014010117

69. Radons J. The human HSP70 family of chaperones: where do we stand? Cell Stress Chaperones (2016) 21(3):379–404. doi:10.1007/s12192-016-0676-6

70. Basu S, Binder RJ, Suto R, Anderson KM, Srivastava PK. Necrotic but not apoptotic cell death releases heat shock proteins, which deliver a partial maturation signal to dendritic cells and activate the NF-kappa B pathway. Int Immunol (2000) 12(11):1539–46. doi:10.1093/intimm/12.11.1539

71. Zanin-Zhorov A, Cahalon L, Tal G, Margalit R, Lider O, Cohen IR. Heat shock protein 60 enhances CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell function via innate TLR2 signaling. J Clin Invest (2006) 116(7):2022–32. doi:10.1172/JCI28423

72. Pei W, Tanaka K, Huang SC, Xu L, Liu B, Sinclair J, et al. Extracellular HSP60 triggers tissue regeneration and wound healing by regulating inflammation and cell proliferation. NPJ Regen Med (2016) 1:16013. doi:10.1038/npjregenmed.2016.13

73. Straino S, Di Carlo A, Mangoni A, De Mori R, Guerra L, Maurelli R, et al. High-mobility group box 1 protein in human and murine skin: involvement in wound healing. J Invest Dermatol (2008) 128(6):1545–53. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5701212

74. Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature (2002) 418(6894):191–5. doi:10.1038/nature00858

75. Wahamaa H, Vallerskog T, Qin S, Lunderius C, LaRosa G, Andersson U, et al. HMGB1-secreting capacity of multiple cell lineages revealed by a novel HMGB1 ELISPOT assay. J Leukoc Biol (2007) 81(1):129–36. doi:10.1189/jlb.0506349

76. Klune JR, Dhupar R, Cardinal J, Billiar TR, Tsung A. HMGB1: endogenous danger signaling. Mol Med (2008) 14(7–8):476–84. doi:10.2119/2008-00034.Klune

77. Jiang W, Bell CW, Pisetsky DS. The relationship between apoptosis and high-mobility group protein 1 release from murine macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide or polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid. J Immunol (2007) 178(10):6495–503. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6495

78. Tang D, Kang R, Xiao W, Jiang L, Liu M, Shi Y, et al. Nuclear heat shock protein 72 as a negative regulator of oxidative stress (hydrogen peroxide)-induced HMGB1 cytoplasmic translocation and release. J Immunol (2007) 178(11):7376–84. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7376

79. Tang D, Kang R, Xiao W, Wang H, Calderwood SK, Xiao X. The anti-inflammatory effects of heat shock protein 72 involve inhibition of high-mobility-group box 1 release and proinflammatory function in macrophages. J Immunol (2007) 179(2):1236–44. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1236

80. Tang D, Shi Y, Kang R, Li T, Xiao W, Wang H, et al. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates macrophages and monocytes to actively release HMGB1. J Leukoc Biol (2007) 81(3):741–7. doi:10.1189/jlb.0806540

81. Rosado MM, Bennici E, Novelli F, Pioli C. Beyond DNA repair, the immunological role of PARP-1 and its siblings. Immunology (2013) 139(4):428–37. doi:10.1111/imm.12099

82. Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, Lazarowski ER, Kadl A, Walk SF, et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature (2009) 461(7261):282–6. doi:10.1038/nature08296

83. Wiley JS, Sluyter R, Gu BJ, Stokes L, Fuller SJ. The human P2X7 receptor and its role in innate immunity. Tissue Antigens (2011) 78(5):321–32. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2011.01780.x

84. Lapa FDR, Júnior SJM, Cerutti ML, Santos ARS. Pharmacology of adenosine receptors and their signaling role in immunity and inflammation. In: Thatha SJ, editor. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. London: InTech (2014). p. 85–130.

85. Raker VK, Becker C, Steinbrink K. The cAMP pathway as therapeutic target in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol (2016) 7:123. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00123

86. Pioli C, Gatta L, Frasca D, Doria G. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibits CD28-induced IkappaBalpha degradation and RelA activation. Eur J Immunol (1999) 29(3):856–63. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199903)29:03<856::AID-IMMU856>3.0.CO;2-P

87. Nasta F, Corinti S, Bonura A, Colombo P, Di Felice G, Pioli C. CTLA-4 regulates allergen response by modulating GATA-3 protein level per cell. Immunology (2007) 121(1):62–70. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02537.x

88. Vendetti S, Riccomi A, Sacchi A, Gatta L, Pioli C, De Magistris MT. Cyclic adenosine 5'-monophosphate and calcium induce CD152 (CTLA-4) up-regulation in resting CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol (2002) 169(11):6231–5. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6231

89. Vincenzi F, Padovan M, Targa M, Corciulo C, Giacuzzo S, Merighi S, et al. A(2A) adenosine receptors are differentially modulated by pharmacological treatments in rheumatoid arthritis patients and their stimulation ameliorates adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. PLoS One (2011) 8(1):e54195. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054195

90. Varani K, Vincenzi F, Ravani A, Pasquini S, Merighi S, Gessi S, et al. Adenosine receptors as a biological pathway for the anti-inflammatory and beneficial effects of low frequency low energy pulsed electromagnetic fields. Mediators Inflamm (2017) 2017:2740963. doi:10.1155/2017/2740963

91. Orru V, Steri M, Sole G, Sidore C, Virdis F, Dei M, et al. Genetic variants regulating immune cell levels in health and disease. Cell (2013) 155(1):242–56. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.041

92. Sun JC, Beilke JN, Lanier LL. Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. Nature (2009) 457(7229):557–61. doi:10.1038/nature07665

93. Nourshargh S, Hordijk PL, Sixt M. Breaching multiple barriers: leukocyte motility through venular walls and the interstitium. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2010) 11(5):366–78. doi:10.1038/nrm2889

94. Mocsai A. Diverse novel functions of neutrophils in immunity, inflammation, and beyond. J Exp Med (2013) 210(7):1283–99. doi:10.1084/jem.20122220

95. Thomas CJ, Schroder K. Pattern recognition receptor function in neutrophils. Trends Immunol (2013) 34(7):317–28. doi:10.1016/j.it.2013.02.008

96. Cassatella MA. The production of cytokines by polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Immunol Today (1995) 16(1):21–6. doi:10.1016/0167-5699(95)80066-2

97. Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol (2006) 6(3):173–82. doi:10.1038/nri1785

98. Borregaard N, Sorensen OE, Theilgaard-Monch K. Neutrophil granules: a library of innate immunity proteins. Trends Immunol (2007) 28(8):340–5. doi:10.1016/j.it.2007.06.002

99. Reeves EP, Lu H, Jacobs HL, Messina CG, Bolsover S, Gabella G, et al. Killing activity of neutrophils is mediated through activation of proteases by K+ flux. Nature (2002) 416(6878):291–7. doi:10.1038/416291a

100. Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science (2004) 303(5663):1532–5. doi:10.1126/science.1092385

101. Parker H, Dragunow M, Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Requirements for NADPH oxidase and myeloperoxidase in neutrophil extracellular trap formation differ depending on the stimulus. J Leukoc Biol (2012) 92(4):841–9. doi:10.1189/jlb.1211601

102. Kaplan MJ, Radic M. Neutrophil extracellular traps: double-edged swords of innate immunity. J Immunol (2012) 189(6):2689–95. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1201719

103. Pall ML. Electromagnetic fields act via activation of voltage-gated calcium channels to produce beneficial or adverse effects. J Cell Mol Med (2013) 17(8):958–65. doi:10.1111/jcmm.12088

104. Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science (2010) 327(5966):656–61. doi:10.1126/science.1178331

105. Song E, Ouyang N, Horbelt M, Antus B, Wang M, Exton MS. Influence of alternatively and classically activated macrophages on fibrogenic activities of human fibroblasts. Cell Immunol (2000) 204(1):19–28. doi:10.1006/cimm.2000.1687

106. Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol (2008) 8(12):958–69. doi:10.1038/nri2448

107. Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity (2010) 32(5):593–604. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007

108. Hume DA. The many alternative faces of macrophage activation. Front Immunol (2015) 6:370. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00370

109. Simko M. Cell type specific redox status is responsible for diverse electromagnetic field effects. Curr Med Chem (2007) 14(10):1141–52. doi:10.2174/092986707780362835

110. Mattsson MO, Simko M. Grouping of experimental conditions as an approach to evaluate effects of extremely low-frequency magnetic fields on oxidative response in in vitro studies. Front Public Health (2014) 2:132. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00132

111. Mattsson MO, Simko M. Is there a relation between extremely low frequency magnetic field exposure, inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases? A review of in vivo and in vitro experimental evidence. Toxicology (2012) 301(1–3):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2012.06.011

113. Landen NX, Li D, Stahle M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: a critical step during wound healing. Cell Mol Life Sci (2016) 73(20):3861–85. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2268-0

114. Costin GE, Birlea SA, Norris DA. Trends in wound repair: cellular and molecular basis of regenerative therapy using electromagnetic fields. Curr Mol Med (2012) 12(1):14–26. doi:10.2174/156652412798376143

115. Pesce M, Patruno A, Speranza L, Reale M. Extremely low frequency electromagnetic field and wound healing: implication of cytokines as biological mediators. Eur Cytokine Netw (2013) 24(1):1–10. doi:10.1684/ecn.2013.0332

116. Saliev T, Mustapova Z, Kulsharova G, Bulanin D, Mikhalovsky S. Therapeutic potential of electromagnetic fields for tissue engineering and wound healing. Cell Prolif (2014) 47(6):485–93. doi:10.1111/cpr.12142

117. Roy S, Khanna S, Nallu K, Hunt TK, Sen CK. Dermal wound healing is subject to redox control. Mol Ther (2006) 13(1):211–20. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.684

118. Brockmann L, Giannou AD, Gagliani N, Huber S. Regulation of TH17 cells and associated cytokines in wound healing, tissue regeneration, and carcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci (2017) 18(5):E1033. doi:10.3390/ijms18051033

119. Plitas G, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: differentiation and function. Cancer Immunol Res (2016) 4(9):721–5. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.cir-16-0193

Keywords: electromagnetic fields, immune-regulation, damage-associated molecular patterns, inflammation, extremely low frequencies, pulsed electro-magnetic fields, immune system, wound healing

Citation: Rosado MM, Simkó M, Mattsson M-O and Pioli C (2018) Immune-Modulating Perspectives for Low Frequency Electromagnetic Fields in Innate Immunity. Front. Public Health 6:85. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00085

Received: 24 October 2017; Accepted: 05 March 2018;

Published: 26 March 2018

Edited by:

Dariusz Leszczynski, University of Helsinki, FinlandReviewed by:

Wilhelm Mosgoeller, Medizinische Universität Wien, AustriaCopyright: © 2018 Rosado, Simkó, Mattsson and Pioli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claudio Pioli, Y2xhdWRpby5waW9saUBlbmVhLml0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.