94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Public Health , 13 February 2018

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 6 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00031

This article is part of the Research Topic Health Promotion for Indigenous Youth: Priorities, Strategies, and Evidence View all 6 articles

Background: Youth peer-led interventions have become a popular way of sharing health information with young people and appear well suited to Indigenous community contexts. However, no systematic reviews focusing on Indigenous youth have been published. We conducted a systematic review to understand the range and characteristics of Indigenous youth-led health promotion projects implemented and their effectiveness.

Methods: A systematic search of Medline, Embase, and ProQuest Social Sciences databases was conducted, supplemented by gray literature searches. Included studies focused on interventions where young Indigenous people delivered health information to age-matched peers.

Results: Twenty-four studies were identified for inclusion, based on 20 interventions (9 Australian, 4 Canadian, and 7 from the United States of America). Only one intervention was evaluated using a randomized controlled study design. The majority of evaluations took the form of pre–post studies. Methodological limitations were identified in a majority of studies. Study outcomes included improved knowledge, attitude, and behaviors.

Conclusion: Currently, there is limited high quality evidence for the effectiveness of peer-led health interventions with Indigenous young people, and the literature is dominated by Australian-based sexual health interventions. More systematic research investigating the effectiveness of peer-led inventions is required, specifically with Indigenous populations. To improve health outcomes for Indigenous youth, greater knowledge of the mechanisms and context under which peer-delivered health promotion is effective in comparison to other methods of health promotion is needed.

Improving the health status of Indigenous young people remains a longstanding aspiration in the colonized western countries of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States of America. Indigenous populations tend to have a younger age profile, and Indigenous adolescents bear a high burden of health problems associated with substance misuse, violence, trauma, sexually transmissible infections and unplanned, high-risk pregnancies; this is related to both historical and contemporary trauma including intergenerational trauma (1).

Government strategies to improve the health outcomes of Indigenous youth often promote the use of peer-led interventions (2–5). Peer-led health promotion is defined as “the teaching or sharing of health information, values and behaviors by members of similar age or status groups” (6). The perceived advantages of the approach derive from the fact that peers have a high level of interaction with one another, and the ability to impart health information in relatable ways (7). Theories of behavioral change (i.e., social learning theory, theory of reasoned action, and diffusion of innovation theory) posit that individuals can be motivated to change their beliefs and practices by observing and interacting with others in their community (8).

Within youth communities, sites of interaction include schools, sporting and recreational events, and designated youth spaces, such as drop-in centers and residential colleges. Interactions can occur one-on-one or in group settings and can take the form of informal discussions between peers or can be more structured. Peer-led interventions are considered particularly useful for educating youth about sensitive topics that may cause fear or embarrassment if discussed with adults, including substance use and sexual health (2).

A number of systematic reviews have examined the efficacy of youth peer-led health promotion programs (9–11). A review by Harden and colleagues found 12 methodologically sound outcome evaluations of peer-led youth health promotion programs; of these, 7 studies found evidence of improved behavioral outcomes (e.g., reduced smoking prevalence, increased frequency of cancer self-examination, reduced incidence of unprotected sex) (9). A further three studies of peer-led interventions found evidence of improvements in relation to “proxy” outcomes, including self-efficacy in using condoms, future intention to use condoms, and attitudes toward sexual health testing (9). A more recent systematic review focusing exclusively on peer-led sexual health interventions supported these findings, with the majority of studies demonstrating improvements in knowledge and attitudes (10). Similarly, a 2016 review of peer-led youth interventions relating to alcohol and other drug use found evidence of lower substance use, improved self-efficacy to engage in safer behaviors, and improved knowledge about target behaviors (11).

However, these studies focus predominately on non-Indigenous populations. Interventions that are effective in one setting are not necessarily directly applicable or transferable to other settings. Effectiveness may be influenced by a range of local factors including social acceptability, culture, the availability of human, financial and material resources, and the educational and socio-economic level of the target population (12). Many of these factors are relevant to Indigenous populations given their unique cultural identities, and experiences of colonization and contemporary social marginalization. For instance, a study of brief intervention tobacco cessation training for clinical staff in an Indigenous health service found no evidence of effectiveness, despite strong evidence from other populations (13). Potential explanations for the difference in outcomes include the fact that health workers were conscious that smoking served an important social function in the communities, and tobacco control was perceived to be less urgent than other local health and social issues (13).

This study seeks to address the gap in the literature by systematically reviewing studies of Indigenous peer-led health promotion programs in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States of America.

The findings of the study will be used to inform the development of a peer-led program to reduce the rates of sexually transmissible infections and blood-borne viruses among Indigenous youth living in remote Australia (14). To that end, existing studies will be analyzed to ascertain: (1) what approaches to peer-led health promotion have been used in Indigenous contexts; and (2) what is the effectiveness of the different approaches.

Existing systematic reviews on the subject of peer-led health interventions were used to identify potentially relevant search terms (11, 15, 16). A combination of text words and database-specific indexing terms/subject headings were used to increase search sensitivity, and no publication date filters were imposed. The searches were conducted in December 2016 and repeated in June 2017. Full search terms are set out in Supplementary Material.

A combination of health/medical and social science databases (Medline, EMBASE, and ProQuest Social Sciences Database) were searched to reflect the multidisciplinary nature of the study of peer-led youth health interventions. To capture gray literature and publications not contained in electronic databases, supplementary searches were conducted. Google [terms: peer-education AND (young or youth) AND (Indigenous OR Aboriginal) AND health] and Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet HealthBulletin (terms: peer OR youth OR young) were searched (no comparable Indigenous databases in New Zealand or North America were identified). Only the first 10 pages of results were manually scanned for relevance. Reference lists of included studies were also scanned for relevant literature.

Results were exported to EndNote and titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. To be included in the systematic review, studies needed to relate to a health promotion intervention that was both aimed at, and delivered by, young people aged 13–29 years who were Indigenous to New Zealand, Australia, Canada, or the United States of America. This systematic review was designed to include both qualitative and quantitative study designs to ensure that both stakeholders’ perceptions/experiences and numerical indicators of effectiveness were captured. Exclusion criteria are set out in Box 1.

Box 1. Exclusion criteria.

Exclude publications that:

• are duplicates

• merely describe an intervention without results (e.g., study protocols, program descriptions)

• do not contain a detailed description of study design and/or findings (e.g., conference posters)

• are published in a language other than English.

The titles and abstracts of all studies were screened by one reviewer (Daniel Vujcich for studies published before December 2016; Jessica Thomas for studies between December 2016 and June 2017). All studies which were not excluded upon preliminary review were then independently screened by two reviewers (Daniel Vujcich and Jessica Thomas) with reference to the full text. Inter-coder consistency was high; only two studies resulted in disagreement about application of inclusion/exclusion criteria and the disagreement was resolved following a discussion between the reviewers.

Included studies were coded for details of study population, study design, nature of intervention, and intervention effectiveness. The quality of the included studies was assessed using Critical Appraisal Skills Program Checklists, and major limitations are set out in the Results section. Meta synthesis was not conducted due to the diversity in the design of the included studies.

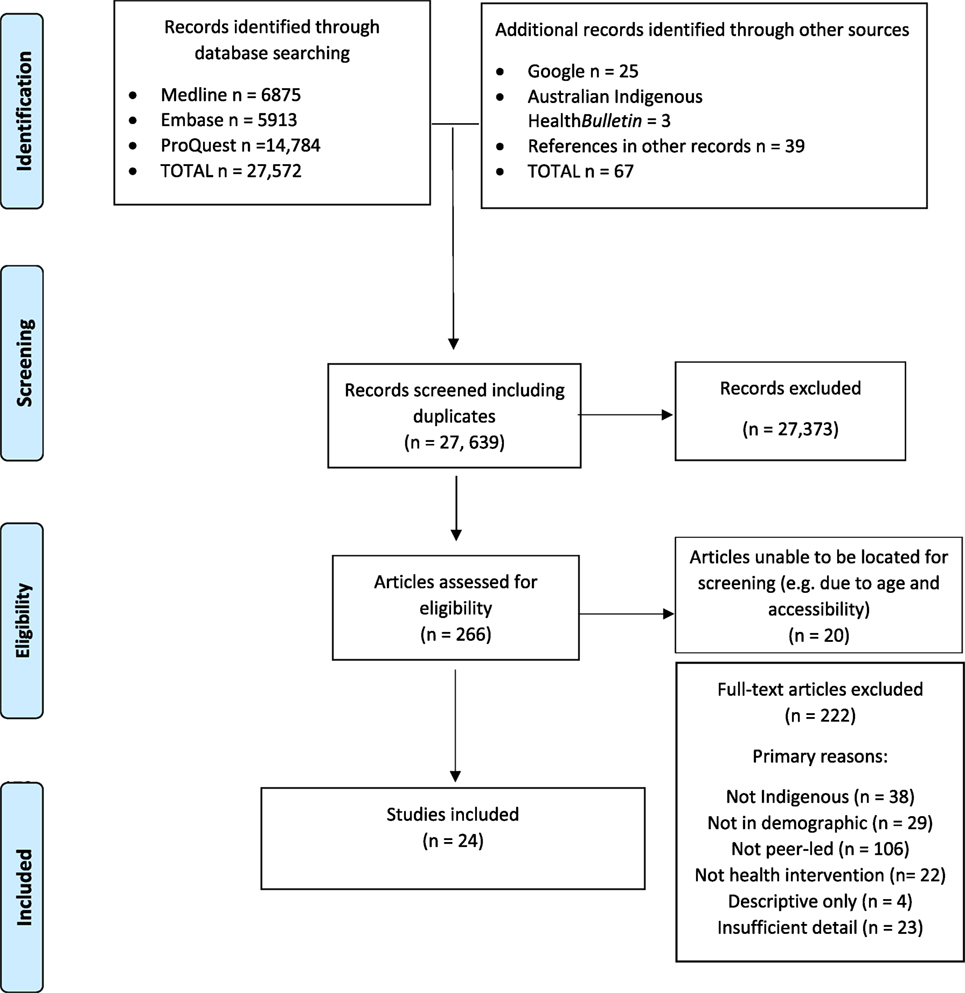

Figure 1 summarizes the results of each stage of the search strategy described above. The 24 included studies related to 20 interventions with Indigenous peer-led components; some studies examined the same programs using different methods or with a focus on different outcomes.

Figure 1. Search result PRISMA diagram (17).

The main characteristics of the interventions are summarized in Table 1. Of the 20 interventions, 9 were based in Australia, 4 were based in Canada, and 7 were based in the United States of America; none of the included studies related to a program aimed at New Zealand’s Maori population. Seven interventions focused on sexual health in combination with another topic area (i.e., alcohol and other drugs/chronic disease/life skills), two focused on sexual health only, three focused on alcohol and other drugs, three studies focused on mental health, two studies focused on asthma/smoking prevention, two studies focused on diabetes, and one focused on cancer prevention generally.

Six programs were conducted in rural and/or remote settings (one of these also had an urban component) and seven projects were aimed at urban youth only. The setting was not reported for the remaining seven interventions.

Eleven of the interventions were community-based only (and two were a combination of community- and school-based). The majority of community-based interventions used cultural and artistic activities as a means of engaging youth (19–22, 27–29, 37). For instance, in some Australian projects, Indigenous youth taught dance, song-writing, and video skills to peers and encouraged them to develop products and/or performances that could be used for wider health promotion (19–22). Similarly, in the United States, the Native Comic Book Project trained young people to deliver 16 lessons to peers with the goal of creating comic books to enhance healthy decision-making around cancer prevention (35).

Five of the interventions were school-based only. These varied between structured curricula/classes (26, 32–34), mentoring arrangements in which older youth offered health guidance and support to younger peers (39) and a creative project whereby students were involved in developing and performing a play incorporating health messages (40).

In the two clinic-based peer-led interventions, youth encouraged their peers to engage with health services. For the Deadly Liver Mob project (17), Indigenous clients attending a needle and syringe program were given a monetary incentive for educating other people about hepatitis C transmission and getting them to visit the service. Similarly, the Young Person Check project (18) offered monetary incentives to youth who recruited peers to obtain STI tests at the clinic.

The interventions differed in terms of the degree of formal education that was offered to peer educators. In some interventions, a highly structured train-the-trainer format was utilized. The Native STAND project (34–35) required peer leaders to complete a course comprising 29 weekly sessions, and the Indigenous Peer Education Project included wider skill development such as public speaking, first aid and computing skills (25). By contrast, other interventions imparted information through one-off sessions and encouraged participants to share what they had learned with others. For instance, peer leaders in the Deadly Liver Mob project received information about blood-borne viruses from Aboriginal health workers during a clinic visit and were encouraged to pass the information on to others (17).

Many of the interventions incorporated some element of Indigenous cultural education or practice. The Four R Program (32) was based on the Indigenous Medicine Wheel Life Cycles, the Indigenous Hip Hop Projects (21) fused traditional culture with modern art forms, and the Taking Action against HIV intervention (29) educated youth about the impact of colonization on Indigenous health outcomes.

The majority of studies found some evidence of changes in behavior, knowledge, or attitude associated with peer-led interventions, as set out in Table 2. Evidence of changes in behavior included increased STI/BBV testing (17, 18), increased use of health services (25), and decreased alcohol and/or other substance use (36, 39). Effects on knowledge included increased awareness of sexual health issues (19, 25, 27–29, 31, 33, 37), improved healthy lifestyle knowledge (38), better understanding of dangers of drug abuse and/or addiction (37, 40), and better understanding about mental health issues and how to support someone feeling depressed (21). Attitudinal changes included improved self-confidence, self-esteem, and/or self-perception (22, 25, 27–29, 31, 32, 35, 36), increased intention to reduce/abstain from substance use (26, 40), and increased intention to use condoms (33).

The quality of the evidence was variable. The only randomized controlled trial was a study in which American Indian teenagers were randomly assigned to one of three group interventions designed to prevent alcohol abuse (39). All groups involved some element of peer counseling, but differed in terms of their additional components (one group had no additional components, one group included self-contracts establishing limits on alcohol use, and the final group included self-contracts and classes). The quantity and frequency of drinking decreased for all groups; however, the results were derived from a small sample (30 youth across the three groups) and the absence of a “non-treatment” group makes it more difficult to discount the possibility that external factors may have driven the observed change. Similarly, the results from a non-randomized trial (the Narragansett substance abuse prevention program) were limited by the fact that the samples were small (n = 9 in intervention and n = 25 control), and confounding factors were not considered in the design despite significant differences in the demographic characteristics of the groups (36).

The majority of the remaining publications were based on experimental pre- and post-study designs. The validity of the results were affected by methodological limitations including small samples (26, 30, 32, 35, 38, 39); high loss to follow-up (21, 33, 36); limited presentation of data (19–25, 29, 31, 34–37); difficulties disaggregating the effects of peer-led interventions from simultaneous interventions (17, 18); and failure to account for confounding factors (30).

This review investigated the use and effectiveness of peer-led health promotion by Indigenous youth. Twenty examples of youth peer-led health interventions in Indigenous contexts were found. The interventions included in this systematic review were most commonly on the topic of sexual health, alcohol, and other drugs and mental health/suicide prevention. Most interventions were based in Australia. Only a minority of studies found evidence of changes of behavior, although this is common in evaluations of public health interventions given the need for long follow-up periods (42). Evidence of changes in knowledge and attitudes was more common, consistent with systematic review findings on the effectiveness of peer-based interventions in other settings (10, 43). In addition to population health improvements, benefits were also conferred to peer leaders in the form of improved self-perception and, in one case, post-intervention employment opportunities.

Methodological limitations impacted on the quality of evidence-base relating to peer-based interventions for Indigenous youth. The relative dearth of “high level” evidence on this subject is not surprising. There are a number of difficulties associated with evaluating peer-led interventions involving Indigenous youth. First, any research involving youth raises distinct ethical issues; these include perceived power disparities, capacity to provide informed consent and legal obligations on the researcher to disclose otherwise confidential data (e.g., reports of physical or sexual abuse) (44, 45). Parents, schools, and other authorities often act as gatekeepers, thus limiting researchers’ access to young people (44–46). Consequently, researchers may avoid studying young people in favor of other classes of participants.

Second, researchers may have difficulty recruiting sufficiently large samples of Indigenous people in the relevant demographic, as shown in Table 2. Given their experiences of colonial exploitation, some Indigenous communities are wary of research and individuals may be reluctant to participate in studies (47–49). Moreover, Indigenous people comprise only a small proportion of the total population in Australia (3%), New Zealand (15%), Canada (4%), and the United States of America (1%) (50–53). It follows that:

many data sources are unsuitable for Indigenous program evaluation because they do not have sufficient numbers of Indigenous respondents for analysis. Even when quantitative analysis is possible, small sample sizes can drastically limit statistical power. This means that, given realistic sample sizes, only very large program impacts are likely to be detected at standard statistical levels (54).

Other issues which can affect research in Indigenous contexts include remoteness, transient populations, and delays due to cultural events (55).

Finally, there are a number of barriers to accurately gauging the effects of population or community-level interventions, regardless of the target group. For example, it can be difficult to recruit sufficient numbers of communities with comparable characteristics; replicate the level and intensity of exposure across communities; and ascertain whether any observed changes are attributable to the intervention or other environmental influences (56).

It does not follow that research on the effectiveness of Indigenous peer-led health interventions should be dismissed as being too difficult. A number of high quality randomized controlled trials have been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of peer-led interventions among Indigenous children (below the 13- to 29-year-old age category that is the focus of this review). These include an evaluation of the Healthy Buddies program in Manitoba in which 60 schools were enrolled in the study; 10 schools were randomly assigned to the Healthy Buddies program, and 10 schools were assigned to receive a standard curriculum (57). First Nations schools were equally represented in the intervention and control arm. Students receiving the peer-led intervention had a significant reduction in waist circumference compared with the control group, and the effects on waist circumference were higher among First Nations compared with other students. Rigorous school-level non-randomized case–control studies of interventions for Indigenous Canadian children have also been conducted and have demonstrated significant effects on physical and behavioral outcomes (58, 59).

In addition to research conducted in academic settings, providers of peer-led health programs could be empowered to build the evidence base. Recommendations include improving service providers’ access to practical evaluation tools; developing their knowledge and skills in evaluation techniques; and providing additional funding to support rigorous data collection (60).

There is also a need for studies which directly compare whether peer-led health interventions are more effective if delivered in school or non-school settings, or whether certain features such as length of training, cultural content, or provision of incentives improve efficacy. At present, funders and planners have little empirical guidance as to what features of peer-led interventions are essential to maximize success. Such information is needed to ensure that resources are utilized in a manner that is most likely to redress the health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth. Research to identify factors influencing success is also necessary given the findings that peer-led health promotion can affect young people’s self-esteem and self-confidence.

With respect to the limitations of this review, it is likely that some studies of Indigenous peer-led health interventions were not located because the findings were not publicly available. The search strategy for this systematic review included gray literature; however, it is possible that relevant sources of gray literature from New Zealand and North America were inadvertently missed by the Australian-based researchers. In addition, some potentially relevant studies may have been excluded because there was insufficient detail to determine whether the inclusion criteria were met.

Currently, there is limited evidence for the effectiveness of peer-led health interventions with Indigenous young people and the knowledge base is dominated by Australian-based sexual health interventions. The studies found positive outcomes from youth peer-led interventions; however, the research available has methodological limitations. More systematic research investigating the effectiveness of peer-led inventions, particularly with Indigenous populations, is required. To improve health outcomes for Indigenous youth, greater knowledge of the mechanisms and context under which peer-delivered health promotion is effective in comparison to other methods of health promotion is needed.

DV, JT, and JW contributed to the design of the work. DV and JT acquired data. All authors contributed to analysis and interpretation, contributed to drafting and critical revisions, approved the final version for publication, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Jelena Maticevic, Amanda Sibosado, Vicki Gordon, Brian Castine, Dominic Guerrera, Mark Saunders, and Linda Forbes.

Funding was provided by the Commonwealth Government of Australia, Department of Health (ITA-H1516G007).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00031/full#supplementary-material.

1. Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet (2009) 374(9683):65–75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60914-4

2. Australian Government. Fourth National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Blood-Borne Viruses and Sexually Transmitted Infections Strategy 2014–2017. Department of Health (2014). Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/ohp-bbvs-atsi

3. Queensland Government. Queensland Sexual Health Strategy 2016. Department of Health (2016). Available from: http://mn-s.weebly.com/youth-suicide-prevention-strategy.html

4. West Kimberley Youth Sector Conference Working Party. Youth Strategy 2014–2016. Kimberley Institute (2014). Available from: http://www.kimberleyinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/WKYSC-Strategy-2014-2016-final.pdf

5. Government of Canada. Acting on What We Know: Preventing Youth Suicide in First Nations. Government of Canada (2005). Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/first-nations-inuit-health/reports-publications/health-promotion/acting-what-we-know-preventing-youth-suicide-first-nations-health-canada-2003.html

6. Sciacca JP. Student peer health education: a powerful yet inexpensive helping strategy. Peer Facil Q (1987) 5(2):4–6.

7. Milburn K. A critical review of peer education with young people with special reference to sexual health. Health Educ Res (1995) 10(4):407–20. doi:10.1093/her/10.4.407

8. UNAIDS. Peer Education and HIV/AIDS: Concepts, Uses and Challenges. Geneva: UNAIDS (1999). Available from: http://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub01/jc291-peereduc_en.pdf

9. Harden A, Oakley A, Weston R. A Review of the Effectiveness and Appropriateness of Peer-Delivered Health Promotion for Young People. Institute of Education, University of London (1999). Available from: http://eprints.ioe.ac.uk/15275/

10. Sun WH, Miu HYH, Wong CKH, Tucker JD, Wong WCW. Assessing participation and effectiveness of the peer-led approach in youth sexual health education: systematic review and meta-analysis in more developed countries. J Sex Res (2016) 55(1):31–44. doi:10.1080/00224499.2016.1247779

11. Hunt S, Kay-Lambkin F, Simmons M, Thornton L, Slade T, Killackey E, et al. Evidence for the Effectiveness of Peer-Led Education for at Risk Youth: An Evidence Check Rapid Review Brokered by the Sax Institute. Sydney: Sax Institute (2006).

12. Wang S, Moss J, Hiller J. Applicability and transferability of interventions in evidence-based public health. Health Prom Int (2006) 21(1):76–83. doi:10.1093/heapro/dai025

13. Harvey D, Tsey K, Cadet-James Y, Minniecon D, Ivers R, Minniecon D, et al. An evaluation of tobacco brief intervention training in three indigenous health care settings in north Queensland. Aust N Z J Public Health (2001) 26(5):426–31. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.2002.tb00342.x

14. South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute. The Remote STI and BBV Project. South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (2017). Available from: https://youngdeadlyfree.org.au/about-us/the-remote-sti-and-bbv-project/

15. Kim CR, Free C. Recent evaluations of the peer-led approach in adolescent sexual health education: a systematic review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health (2008) 40(3):144–51. doi:10.1363/4014408

16. Medley A, Kennedy C, O’Reilly K, Sweat M. Effectiveness of peer education interventions for HIV prevention in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Educ Prev (2009) 21(3):181–206. doi:10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3.181

17. Biggs K, Walsh J, Ooi C. Deadly liver mob: opening the door-improving sexual health pathways for Aboriginal people in Western Sydney. Sex Health (2016) 13(5):457–64. doi:10.1071/SH15176

18. Fagan P, Cannon F, Crouch A. The young person check: screening for sexually transmitted infections and chronic disease risk in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth. Aust N Z J Public Health (2013) 37(4):316–21. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.12078

19. McEwan A, Crouch A, Robertson H, Fagan P. The Torres Indigenous Hip Hop project: evaluating the use of performing arts as a medium for sexual health promotion. Health Promot J Austr (2013) 24(2):132–6. doi:10.1071/HE12924

20. Crouch A, Robertson H, Fagan P. Hip hopping the gap – performing arts approaches to sexual health disadvantage in young people in remote settings. Aust Psychiatry (2011) 19(1):SS34–7. doi:10.3109/10398562.2011.583046

21. Hayward C, Monteiro H, McAullay D. Evaluation of Indigenous Hip Hop Projects. Melbourne: Beyondblue (2009).

22. Bentley M. Evaluation of the Peer Education Component of the Young Nungas Yarning Together Program. Adelaide: South Australian Community Research Unit (2008).

23. Tighe J, McKay K. Alive and kicking goals! Preliminary findings from a Kimberley suicide prevention program. Adv Ment Health (2012) 10(3):240–5. doi:10.5172/jamh.2012.10.3.240

24. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Demonstration Projects for Improving Sexual Health in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Youth: Evaluation Report. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2013).

25. Mikhailovich K, Arabena K. Evaluating an indigenous sexual health peer education project. Health Promot J Austr (2005) 16(3):189–93. doi:10.1071/HE05189

26. McCallum GB, Chang AB, Wilson CA, Petsky HL, Saunders J, Pizzutto SJ, et al. Feasibility of a peer-led asthma and smoking prevention project in Australian schools with high indigenous youth. Front Pediatr (2017) 5:33. doi:10.3389/fped.2017.00033

27. Flicker S, Danforth J, Konsmo E, Wilson C, Oliver V, Jackson R, et al. “Because we are natives and we stand strong to our pride”: decolonizing HIV prevention with aboriginal youth in Canada using the arts. Can J Aborig Commun Based HIVAIDS Res (2013) 5:4–24.

28. Wilson C, Oliver V, Flicker S. “Culture” as HIV prevention. Gatew Int J Commun Res Engagem (2016) 9(1):74–88. doi:10.5130/ijcre.v9i1.4802

29. Flicker S, Yee J, Larkin J, Jackson R, Prentice T, Restoule JP, et al. Taking Action! Art and Aboriginal Youth Leadership for HIV Prevention. Toronto, ON (2012).

30. Huynh E, Rand D, McNeill C, Brown S, Senechal M, Wicklow B, et al. Beating diabetes together: a mixed-methods analysis of a feasibility study of intensive lifestyle intervention for youth with type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabetes (2015) 39(6):484–90. doi:10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.09.093

31. Majumdar BB, Chambers TL, Roberts J. Community-based, culturally sensitive HIV/AIDS education for Aboriginal adolescents: implications for nursing practice. J Transcult Nurs (2004) 15(1):69–73. doi:10.1177/1043659603260015

32. Crooks C, Exner-Cortens D, Burn S, Lapointe A, Chiodo D. Two-years of relationship-focused mentoring for First Nations, Metis, and Inuit adolescents: promoting positive mental health. J Prim Prev (2017) 38:87–104. doi:10.1007/s10935-016-0457-0

33. Smith MU, Rushing SC, The Native STAND Curriculum Development Group. Native STAND (students together against negative decisions): evaluating a school-based sexual risk reduction intervention in Indian boarding schools. Health Educ Monogr (2011) 28(2):67–74.

34. Rushing SNC, Hildebrandt NL, Grimes CJ, Rowsell AJ, Christensen BC, Lambert WE. Healthy & empowered youth: a positive youth development program for native youth. Am J Prev Med (2017) 52(3):S263–7. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.024

35. Montgomery M, Manuelito B, Nass C, Chock T, Buchwald D. The native comic book project: native youth making comics and healthy decisions. J Cancer Educ (2012) 27(1):41–6. doi:10.1007/s13187-012-0311-x

36. Parker L. The missing component in substance abuse prevention efforts: a Native American example. Contemp Drug Probs (1990) 17:251.

37. Aguilera S, Plasencia AV. Culturally appropriate HIV/AIDS and substance abuse prevention programs for urban native youth. J Psychoactive Drugs (2005) 37(3):299–304. doi:10.1080/02791072.2005.10400523

38. Marlow E, D’Eramo Melkus G, Bosma AM. STOP diabetes! An educational model for Native American adolescents in the prevention of diabetes. Diabetes Educ (1998) 24(4):441–50. doi:10.1177/014572179802400403

39. Carpenter RA, Lyons CA, Miller WR. Peer-managed self-control program for prevention of alcohol abuse in American Indian high school students: a pilot evaluation study. Int J Addict (1985) 20(2):299–310. doi:10.3109/10826088509044912

40. Mitschke D, Loebl K, Tatafu E, Matsunaga D, Cassel K. Using drama to prevent teen smoking: development, implementation, and evaluation of crossroads in Hawai’i. Health Promot Pract (2010) 11(2):244–8. doi:10.1177/1524839907309869

41. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med (2009) 6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

42. Jepson R, Harris F, Platt S, Tannahill C. The effectiveness of interventions to change six health behaviours: a review of reviews. BMC Public Health (2010) 10:538. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-538

43. Harden A, Oakley A, Oliver S. Peer-delivered health promotion for young people: a systematic review of different study designs. Health Educ J (2001) 60(4):339–53. doi:10.1177/001789690106000406

44. Morrow V, Richards M. The ethics of social research with children: an overview. Child Soc (1996) 10:90–105. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.1996.tb00461.x

45. Ethics and Social Research Council. Research with Children and Young People. Ethics and Social Research Council (2017). Available from: http://www.esrc.ac.uk/funding/guidance-for-applicants/research-ethics/frequently-raised-topics/research-with-children-and-young-people/

46. Bauman L, Sclafane J, LoIacono M, Wilson K, Macklin R. Ethical issues in HIV/STD prevention research with high risk youth: providing help, preserving validity. Ethics Behav (2008) 18(2/3):247–65. doi:10.1080/10508420802066833

47. Cochran P, Marshall C, Garcia-Downing C, Kendall E, Cook D, McCubbin L, et al. Indigenous ways of knowing: implications for participatory research and community. Health Policy Ethics (2008) 98:22–7. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.093641

48. Tuhiwai Smith L. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. New York: Zed Books (1999).

49. Humphery K. Dirty questions: indigenous health and ‘western research’. Aust N Z J Public Health (2001) 25:197–202. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00563.x

50. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Australian Bureau of Statistics (2011). Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3238.0.55.001

51. Statistics NZ. Census Ethnic Group Profiles: Maori. StatsNZ (2013). Available from: http://archive.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/ethnic-profiles.aspx?request_value=24705&parent_id=24704&tabname=#24705

52. Statistics Canada. Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Metis and Inuit. Statistics Canada (2011). Available from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-011-x/99-011-x2011001-eng.cfm

53. National Congress of American Indians. Demographics. National Congress of American Indians (Accessed 2017). Available from: http://www.ncai.org/about-tribes/demographics

54. Cobb-Clark D. The Case for Making Public Policy Evaluations Public. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (2013).

55. Snijder M, Shakeshaft A, Wagemakers A, Stephens A, Calabria B. A systematic review of studies evaluating Australian indigenous community development projects: the extent of community participation, their methodological quality and their outcomes. BMC Public Health (2015) 15:1154. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2514-7

56. Merzel C, D’Afflitti J. Reconsidering community-based health promotion: promise, performance, and potential. Am J Public Health (2003) 93(4):557–74. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.4.557

57. Ronsley R, Lee AS, Kuzeljevic B, Panagiotopoulos C. Healthy Buddies™ reduces body mass index Z-score and waist circumference in Aboriginal children living in remote coastal communities. J Sch Health (2013) 83(9):605–13. doi:10.1111/josh.12072

58. Santos RG, Durksen A, Rabbani R, Chanoine J-P, Miln AL, Mayer T, et al. Effectiveness of peer-based healthy living lesson plans on anthropometric measures and physical activity in elementary school students: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA Pediatr (2014) 168(4):330–7. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3688

59. Eskicioglu P, Halas J, Sénéchal M, Wood L, McKay E, Villeneuve S, et al. Peer mentoring for type 2 diabetes prevention in first nations children. Pediatrics (2014) 133(6):e1624–31. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2621

Keywords: peer education, health promotion, Aboriginal health, first nations health research, Indigenous health, systematic review, youth, young people

Citation: Vujcich D, Thomas J, Crawford K and Ward J (2018) Indigenous Youth Peer-Led Health Promotion in Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and the United States: A Systematic Review of the Approaches, Study Designs, and Effectiveness. Front. Public Health 6:31. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00031

Received: 08 September 2017; Accepted: 29 January 2018;

Published: 13 February 2018

Edited by:

Colette Joy Browning, Shenzhen International Primary Healthcare Research Institute, ChinaReviewed by:

Janya McCalman, Central Queensland University, AustraliaCopyright: © 2018 Vujcich, Thomas, Crawford and Ward. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniel Vujcich, ZGFuaWVsLnZ1amNpY2hAYWhjd2Eub3Jn

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.