- 1Department of Health Promotion Sciences, Zuckerman College of Public Health, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

- 2Departamento de Antropología, Universidad de las Américas Puebla, Cholula, Mexico

Background: The militarization of the US–Mexico border region exacerbates the process of “Othering” Latino immigrants – as “illegal aliens.” The internalization of “illegality” can manifest as a sense of “undeservingness” of legal protection in the population and be detrimental on a biopsychological level.

Objective: We explore the impacts of “illegality” among a population of US citizen and permanent resident farmworkers of Mexican descent. We do so through the lens of immigration enforcement-related stress and the ability to file formal complaints of discrimination and mistreatment perpetrated by local immigration enforcement agents, including local police authorized to enforce immigration law.

Methods: Drawing from cross-sectional data gathered through the National Institute of Occupation Safety and Health, “Challenges to Farmworker Health at the US–Mexico Border” study, a community-based participatory research project conducted at the Arizona–Sonora border, we compared Arizona resident farmworkers (N = 349) to Mexico-based farmworkers (N = 140) or Transnational farmworkers who cross the US–Mexico border daily or weekly to work in US agriculture.

Results: Both samples of farmworkers experience significant levels of stress in anticipation of encounters with immigration officials. Fear was cited as the greatest factor preventing individuals from reporting immigration abuses. The groups varied slightly in the relative weight attributed to different types of fear.

Conclusion: The militarization of the border has consequences for individuals who are not the target of immigration enforcement. These spillover effects cause harm to farmworkers in multiple ways. Multi-institutional and community-centered systems for reporting immigration-related victimization is required. Applied participatory research with affected communities can mitigate the public health effects of state-sponsored immigration discrimination and violence among US citizen and permanent residents.

Introduction

US immigration enforcement efforts grew considerably over the last few decades, with a nearly 15-fold increase in funding from 1986 to 2012 channeled into the nation’s principle enforcement agencies. Customs and border protection (CBP) and immigration and customs enforcement (ICE), whose FY2012 budget totaled 17.9 billion dollars (1), contribute to the militarization of the US–Mexico border. Militarization is defined as the saturation of and pervasive encounters with immigration officials including local police enacting immigration and border enforcement policy with military style tactics and weapons (2). These enforcement measures are applied at ports of entry (POE), in the deserts, rivers, and mountains between POEs, and, increasingly, in public spaces, workplaces, and residential areas in the border region and elsewhere (3, 4).

The territorial boundary of the sovereign state has always been fundamental to the creation of social hierarchies. The intersections of ethnicity, race, class, and gender relegate people to social categories some of whose members have rights of membership, including US citizens and permanent residents and “Others” who do not possess such rights, such as unauthorized immigrants or “illegal aliens” (5, 6). In the US–Mexico border region, the process of “Othering” categorizes Latino immigrants and migrants, including their non-immigrant co-ethnics as “illegal aliens” (5, 7, 8). The symbolic violence (9, 10) or the implicit way in which cultural and social domination is maintained on an unconscious level through discriminatory practices generated by sexism, racism, and classism naturalizes the notion of “illegality.” Through this process, certain groups are categorized as non-rights-bearing individuals (11, 12). The erasure of legal personhood manifests as the inability to obtain work authorization and restricted physical and social mobility, which reinforces immigrants’ forced invisibility, exclusion, and sense of vulnerability to being deported (12, 13). The militarization of the border contributes to the construction of such notions of “illegality” of Latino populations by inscribing difference “upon Mexican migrants” themselves, as their distinctive spatialized (and racialized) status as “illegal aliens,” as Mexicans “out of place” (5).

In the context of the “War on Terror,” the regulatory policies associated with enforcement conflate migrants with terrorists, drug smugglers, and human traffickers who represent a threat to national security (14–16). The criminalization of immigration law erodes the legal protections that once covered non-citizens, subjecting ever-growing numbers to deportation (17–19). Further, there is growing evidence that border enforcement leads to maltreatment of persons that violates their civil and human rights through the excessive use of force and verbal and physical abuse (4, 14, 20).

Cumulative exposure to institutional arrangements, ethno-racial hierarchies, and citizen/non-citizen distinctions that systematically marginalize individuals create disproportionate levels of structural vulnerability (21). Defined as “a positionality that imposes physical and emotional suffering on specific population groups and individuals in patterned ways,” structural vulnerability reproduces inequality by casting certain groups as less worthy of material and social protection (22). The subordinated status created through “illegality” may be internalized by Latino immigrant and migrants and detrimental on a biopsychological level (23–26). Farmworkers especially experience high levels of structural vulnerability due to their subordinate status in the social hierarchy (27). As a result, farmworkers in general experience greater prevalence of chronic disease risk factors and poorer mental health outcomes compared to non-farmworker US Hispanic populations (28–31).

This study aimed to explore ways in which a relatively large sample of immigrant and migrant farmworkers of Mexican descent who are US citizen and permanent residents and live and work in the Arizona–Sonora, Mexico border region experience “illegality” and the impact it has on their health. We hypothesized that transnational border residents, or those farmworkers who live permanently in Mexico and cross the border to work in US agriculture would be more likely to experience an internalized sense of “illegality” due to their residence outside the US and the need to cross the border for employment. Such perceptions of “illegality” could come in form of feeling as though they “belonged less” to the nation compared to those immigrant and migrant farmworkers who live in Arizona because of their residence outside the country. We contend that the need to cross the border daily and interact frequently with immigration enforcement officials at points of entry would bolster transnational farmworkers sense of being “Other” and negatively affect their well-being.

Materials and Methods

The National Institute of Occupation Safety and Health, “challenges to farmworker health (CFH) at the US–Mexico Border” is a community-based participatory research (CBPR) project conducted by the University of Arizona, Zuckerman College of Public Health, and the Binational Migration Institute located in the Department of Mexican American Studies in partnership with Campesinos Sin Fronteras, a community-based agency serving regional border residents and Derechos Humanos, a human rights organization advocating on behalf of Arizona immigrant families (32). A detailed discussion of this partnership is reported elsewhere (4, 33).

Challenges to farmworker health is a cross-sectional, population-based survey using a randomized proportionately representative household sample (N = 299) and a convenience sample (N = 200) of men and women of Mexican descent aged 20 years and older who were farmworkers during the 12 months preceding the survey. To obtain the household sample, researchers randomly selected census blocks for three adjacent Arizona-border communities; all were low income and typically medically under-served communities in which agricultural workers were the dominant residents. A modified survey was then utilized as an opportunistic survey conducted at specific pick-up points for farmworkers with the same enrollment restrictions mentioned, who may have been missed in the primary survey. This survey targeted those farmworkers not living in local household but rather commute from a distance, live in their automobiles, live across the border (including US residents), or live in “colonias” not yet mapped to the existing city and county neighborhood plots. For the purposes of this paper, the household and opportunistic samples were merged and stratified by transnational farmworkers who did not live in the US but crossed the Mexico border daily or weekly to work in US agriculture (N = 140) and those farmworkers whose primary residence was in Arizona (N = 349) referred to herein as Arizona-based farmworkers.

Essential to this study, were community health workers or Promotoras, who shared cultural and linguistic history of participants, contributed to survey modification and provided insight into cultural and regional relevance of interview questions. Promotoras were trained by UA research staff to conduct interviews and collected the majority of the survey data over the summer months of 2006–2007. Promotoras contacted a total of 323 adults who met study criteria, of which 299 agreed to participate, resulting in a 93% response rate. We believe CBPR, which equitably engaged affected community members throughout the research process, and the full engagement of Promotoras as trusted members of the community, increased the likelihood of participation and quality of the self-reported data. A detailed description of the CFH study sampling frame and partner agency relationships in CBPR is found elsewhere (33).

To examine the existing level of structural vulnerability within the population, descriptive statistics were calculated for variables shared by both the household and the abbreviated opportunistic survey instruments, these include selected demographics (age, years working in US agriculture), immigration status, access to health care coverage, and immigration encounter and immigration-related stress. Drawing from survey items from the Immigration and Border Interaction Survey conducted over a 15-year period in one Southern Arizona-border community (34, 35), respondents were also asked about their experiences with immigration officials and the perceptions of how immigration officials differentiate between US citizens and individuals unauthorized to be in the US. Stress was measured with items from the Border Community and Immigration Stress Scale (BCISS), a 21-item scale that considers the presence and intensity of culturally and contextually relevant stressors (33). BCISS stress domains include migration, acculturation, and barriers to health care, discrimination, economic strains, and family separation. For this study, we explored four border community and immigration-related stressors, including stress caused by encounters with immigration officials, local police, and the presence of military in the region. The BCISS is a 5-point Likert scale, which measures the level or intensity of the stress experienced for each given domain. For the domains of interest, we created a dichotomous variable to categorize respondents by self-reported feelings of very or extreme stress and those that experienced low to moderate stress. Data reported here illustrate those respondents who self-reported very or extreme stress, which is narrated in text as intense stress. Full description of the 21-BCISS can be found elsewhere (33).

Most importantly, we wanted to explore how such cumulative immigration-related surveillance, encounters and stress might contribute to a sense of undeservingness of social protection from immigration-related mistreatment or discrimination among study participants. To do so, we analyzed Arizona and transnational participants’ short narratives of reasons to file and not to file a formal complaint with immigration authorities regarding an immigration related mistreatment episode.

Analysis

We explored differences between the two samples through Fisher’s Exact for demographic and experiences with immigration officials. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 10.0 software. We used grounded theory to code themes that emerged from the short narratives and stratified that analysis by Arizona and transnational participants (36). The UA Office of Human Subject Protection approved this research.

Results

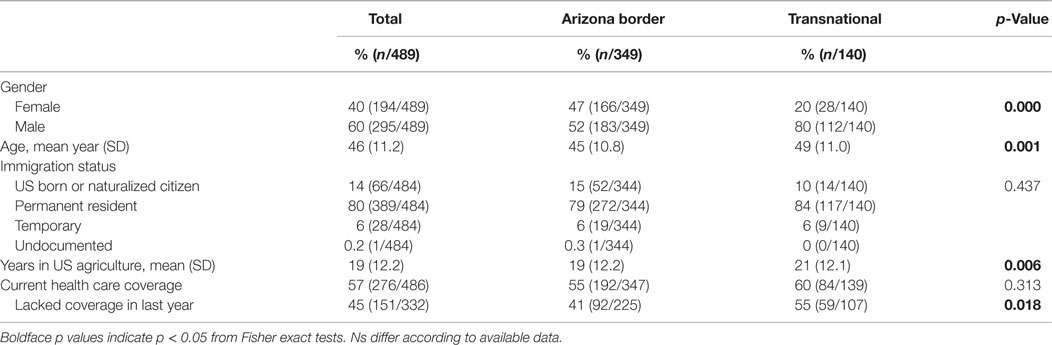

There were no significant differences between the two samples in terms of immigration status as approximately 90% of all participants were self-identified US citizens or permanent residents. Only one participant self-identified with an undocumented immigration status and this participant was in the Arizona-border sample (Table 1). The remaining 8% of participants had a temporary residency status, meaning that they were in the process of permanent residency status or had a border-crossing card, which allowed them to cross into the US and work in US agriculture. Transnational farmworkers were significantly more likely to be male, older and employed for more years in US agriculture compared to Arizona-based border farmworkers.

Experiences with US Immigration Officials, Including Local Police

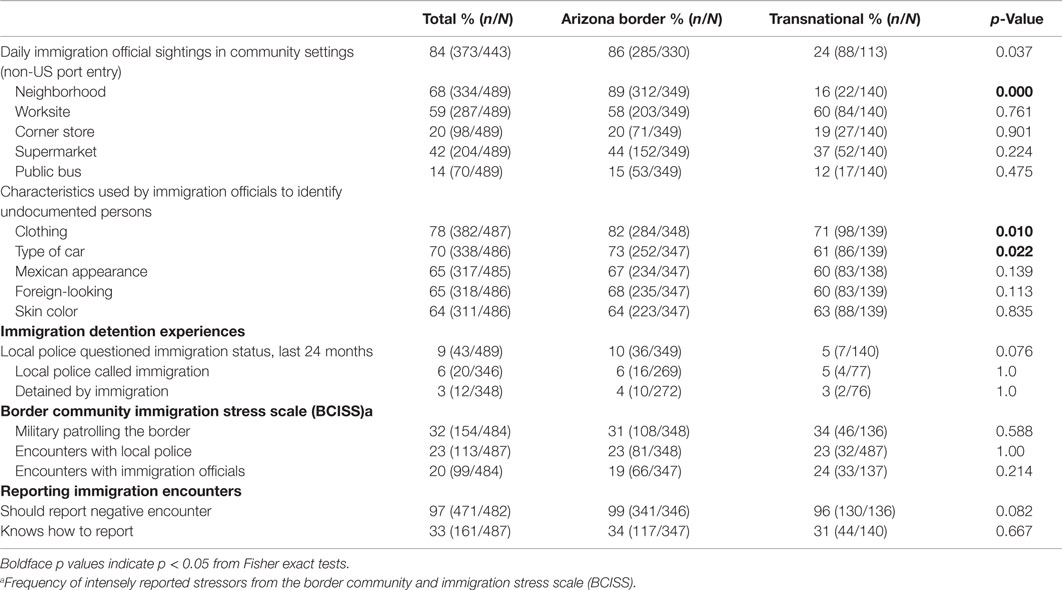

Although the Arizona-border sample was significantly more likely to see immigration officials in their neighborhoods, both study samples were as likely to observe immigration officials at the worksite, corner store, and the local supermarket. Arizona border respondents were significantly more likely to believe immigration officials, including local police, used individual characteristics of clothing and the type of vehicle to identify undocumented persons (Table 2). Although not statistically significant, Arizona border residents were more likely to be detained and questioned by local police regarding their immigration status compared to the transnational participants. Among those participants who were detained by local police, local police called immigration officials and detained Arizona and transnational farmworkers at almost equal rates.

Table 2. Comparisons of experiences and encounters with US immigration and local police among Arizona-border and transnational farmworkers.

Almost all Arizona and transnational farmworkers believed negative immigration encounters should be reported. However, only about one-third of both populations reported knowing how to file a formal complaint of immigration mistreatment.

In terms of self-reported immigration-related intense stress, approximately one-third of all participants experienced intense stress due to military patrolling the border region. No <20% of all respondents experienced this same level of intense stress in anticipation of encounters with local police or encounters with immigration officials. There were no significant differences in the levels of stress produced by such encounters among the two samples.

Complaint Making Regarding Immigration Mistreatment

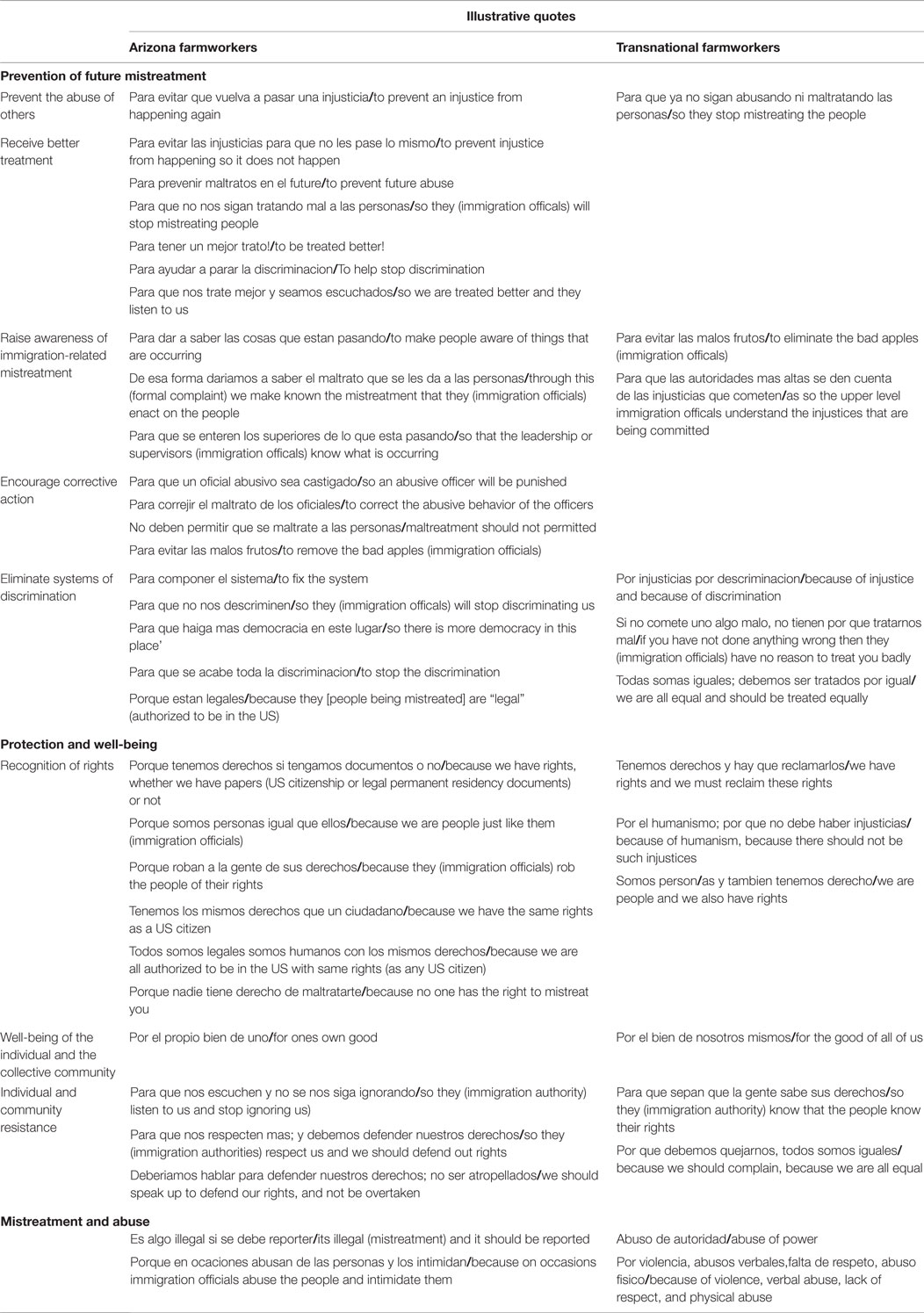

Farmworker short narratives illuminated several themes regarding reasons to file a complaint of mistreatment by immigration officials (Table 3). Prevention of future mistreatment accounted for 29% of all narratives. According to farmworkers, filing a complaint of immigration-related mistreatment contributed to the prevention of mistreatment in several forms. First and foremost by filing a formal complaint one could contribute to raising awareness of immigration-related mistreatment. Complaints also served to elicit corrective action among those immigration officials who engaged in behavior beyond the scope of their mandate. More broadly, farmworkers believed formal complaints could contribute to the elimination of existing systems of discrimination.

Table 3. Summary of reasons to file a formal complaint of immigration-related mistreatment among Arizona and transnational farmworkers of Mexican descent.

The second major thematic category within the reasons to file a complaint of mistreatment was protection of overall well-being. Protection of well-being came in many forms including acknowledgment of civil and human rights, and avoidance of abuse. Farmworkers described in detail their inherent civil and human rights, which they believe should protect them and their community members from such mistreatment. Although far less mentioned, in some cases, farmworkers described the forms of resistance individual and community members engage in to monitor mistreatment.

When comparing the two groups, Arizona-border residents more often identified prevention of future mistreatment and human and civil rights compared to transnational participants who were more literal in their rational for complaint making who most often abuse of any kind. Both sets of participants reported formal complaint making about immigration-related mistreatment could contribute to positive changes in the larger immigration and police system.

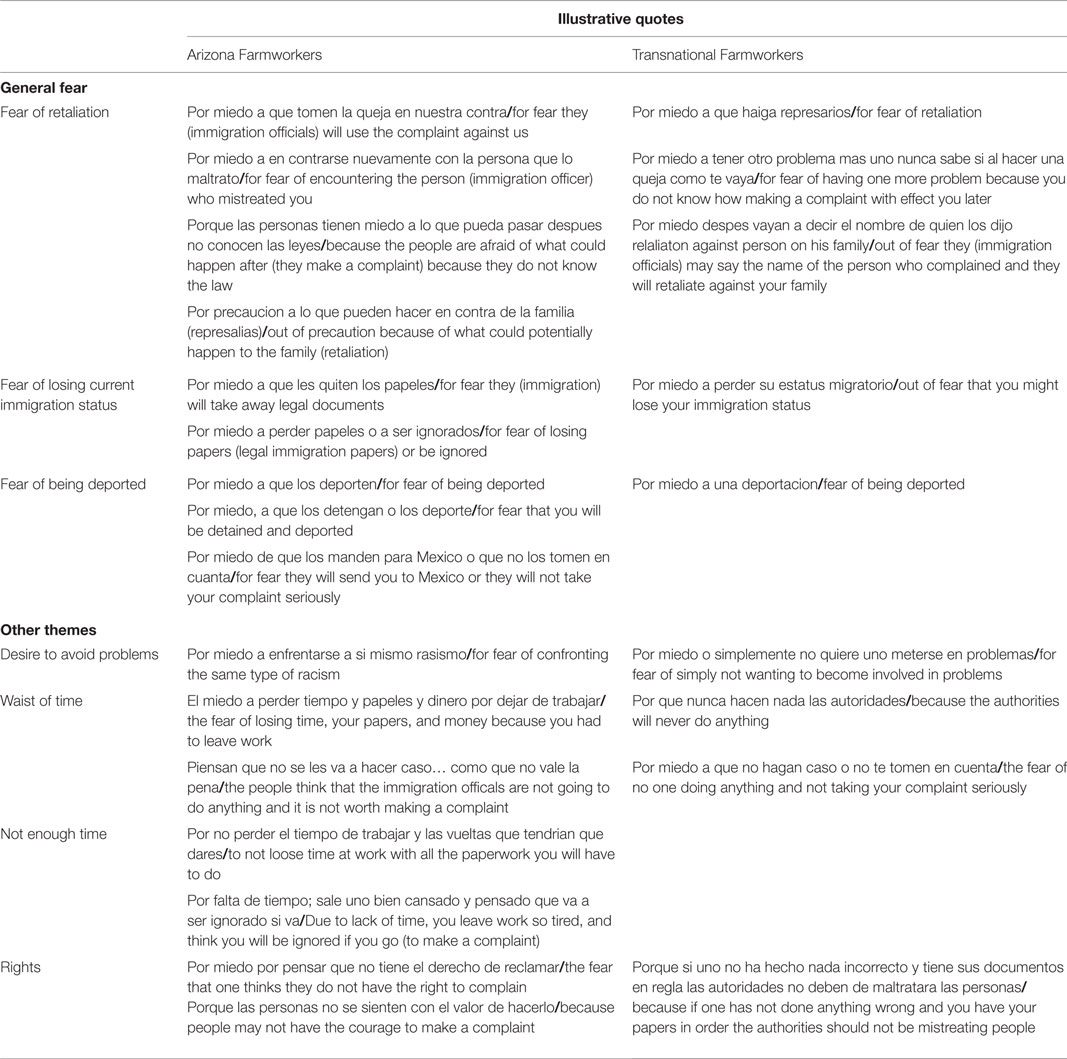

We shift now to the reasons farmworkers would choose not to make a formal complaint of immigration-related mistreatment. Approximately 31% of the total sample stated fear as the number one reason not to file a formal complaint of mistreatment (Table 4). Fear came in many forms including fear of retaliation by immigration officials, fear of losing current immigration status, and fear of being deported (Table 4). Although a nuanced form of fear, other farmworkers described not filing a report because they wanted to avoid problems with officials, suggesting that by virtue of filing they may experience some form of investigation. Others expressed the sense that their complaint would not be taken seriously even if they reported it. The intensive work hours among farmworkers was also a deterrent from filing a report, as some farmworkers described not having enough time in the day to do so. This sense of not having enough time to file was often linked to the idea of wasting time in filing as if their complaint would not be acted upon.

Table 4. Summary of reasons not to file a formal complaint of immigration-related mistreatment among Arizona and transnational farmworkers of Mexican descent.

Discussion

We show that in the border region, immigrants and migrants of Mexican descent with US permanent residence and citizenship feel vulnerable to being identified as “out of place” and, subsequently, the target of immigration enforcement. Immigration officials’ presence was pervasive and not confined to the US port of entry but was experienced by participants in public spaces, including neighborhoods, worksites, and local markets. Arizona border and transnational immigrant and migrant farmworkers experience high levels of stress associated with encounters and or anticipated encounters with immigration officials. Furthermore, participants believed that these officials used personal characteristics to differentiate the population and identify individuals with an undocumented or “illegal” immigration status. We were unable to confirm our hypothesis, as there were only a few consistent differences between the two samples that would suggest that any one group would internalize “illegality” more or less than the other. Lack of difference between the two groups suggests that US immigration enforcement permeates the public spaces where both Arizona resident and transnational farmworkers conduct their lives constituting an imminent threat of state-sponsored violence to both of these authorized populations.

Most notable of the ways in which the two populations may internalize a sense of “illegality” or “undeservingness” for social protection from immigration-related discrimination and mistreatment is the high proportion of respondents reporting fear as the primary reason why they themselves or others in the community may not report immigration mistreatment. Immigration enforcement in the borderlands relies heavily not only on undocumented status but also on legal status as perceived through ethno-racial profiling of subjects. In the context of militarized border enforcement and the criminalization of immigration, the distinctions between rights-bearing subjects and those without any rights are blurred. While farmworkers indicate that they know their rights to file complaints and the positive potential of doing so (Table 3), their fears indicate that they do not believe their rights can protect them within the militarized climate of the border (Table 4). Permanent residents and citizens of Mexican descent internalize their subordinated racialized status, fearing that their legal status can be easily revoked if they file complaints of maltreatment by immigration officers or local police. Deportability – an essential dimension of “illegality” – is not only implicated in creating an exploitable workforce (5) but also is a key site of the production of state power and the ability of the US to govern its citizens and permanent residents (37). The social cost of the symbolic and material fortification of the border can be measured in its effects upon farmworkers’ sense of exclusion and fear of losing “that which has been established,” that is, their basic rights as residents and citizens. This study provides further evidence of the “spillover” effects of immigration enforcement onto groups who are not the target of immigration enforcement. The resulting biopsychological harm demonstrates how the current enforcement regime is detrimental to society (38).

Public Health Policy Implications and Future Research

As border security remains compulsory to the US immigration reform policy debate, and persuasive in public discourse, our study confirms that immigration policy and specifically those polices aimed at border enforcement is a structural determinant of health. Defined by the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, structural determinants are those distal policy and systems levels phenomena that directly and indirectly affect the public’s health (39, 40). Such structural determinants require large-scale political and social change. Institutional practices of discrimination within US immigration and border enforcement political systems have only recently emerged as determinants of health inequality (41) and few studies have linked these experiences to poor mental health outcomes (33). Broadly, restrictive or punitive immigration policies are known to limit access to health and social services (42, 43), education opportunities, and adequate employment remuneration (41, 44). In Arizona, anti-immigrant policies have been documented to limit mobility among Mexican immigrants to engage in normal activities and create fear of accessing health and social services among the population (43).

Our study provides strong evidence for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to enact and enforce policies that benefit public health, such as; (1) articulate and make transparent CBP training, oversight, investigation protocols, and the disciplinary actions taken against CBP officers and local police who breach their scope when enforcing immigration law (20, 45); (2) create a transparent, community-centered oversight system to document and monitor immigration-related victimization, including corruption and excessive use of force by CBP and local police enacting immigration law; (3) develop an accountability plan by CBP and local law enforcement to systematically report and respond to community concerns of corruption and excessive use of force.

Participatory action research that fully engages affected border communities is necessary to monitor immigration-related victimization and locate the points of community and policy-level intervention to decrease victimization within border communities. The Southern Border Communities Coalition’s, “Revitalize, Not Militarize” is one example of a grassroots effort in which border community members have mobilized to reframe the issue of border security as an issue of economic development. Calling for investment in all border communities to improve the quality of life of the region and trade between the US and Mexico, the campaign engages a multi media platform for border residents to share their testimonies, monitor immigration-related mistreatment, and civil and human rights abuses and advocate at state and national levels for oversight and accountability by the Department of Homeland Security and Customs and Border Patrol Agents (46). Such community-driven campaigns linked to advocacy can contribute to empowerment of affected communities and have the potential to begin to repair the detrimental effects of immigration-related structural vulnerability, which includes the internalization and normalization of such violence.

Limitations and strengths

This study may not be generalizable to non-border communities; study participants may be more likely to be in frequent contact with immigration authorities compared to those individuals in non-border communities. These results may also underestimate the prevalence of immigration-related mistreatment and associated stress in highly militarized and policed communities, as those individuals with an undocumented immigration status may be less likely to participate. Data are self-report and the potential for social desirability may also contribute to over or under estimation of mistreatment experiences. The CBPR approach, however, contributed to the overall strength of the study, specifically, in survey development, data collection, and the validity of the study constructs to community identified health issues. Study partners were uniquely embedded in the community, and shared many of the cultural and immigration trajectories of study participants thus giving UA researchers invaluable insight and access to a highly vulnerable population. This historical and trusting relationship between University researchers and study partner agencies, and the utilization of Promotoras as primary data collectors contributed to increased cultural salience of sampling procedures, survey instrument development and implementation as evidenced by a 93% response rate and limited missing data in the household survey data.

Conclusion

US citizens and permanent residents of Mexican descent living in the border region experience frequent encounters with immigration officials in public spaces at almost equal rates. These encounters are not confined to the point of entry. Anticipation of such encounters is experienced as intense stressors. Moreover, the primary reason for not reporting immigration-related abuse or mistreatment is fear and specifically the fear of losing existing immigration status. Such mistrust in the system and fearing retaliation by the state is evidence of a population who has potentially normalized mistreatment as a form of coping in the face of a broken system in which justice and retribution could only occur at a cost. Multi-institutional and community-centered systems for reporting and mitigating immigration-related victimization are required. Applied participatory research with affected communities can mitigate the public health effects of state-sponsored immigration discrimination and violence.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Meissner D, Kerwin D, Chishti M, Bergeron C. Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (2013).

2. Dunn T. The Militarization of the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1978-1992: Low-Intensity Conflict Doctrine Comes Home. Austin, TX: CMAS Books, University of Texas at Austin (1996).

3. Heyman J. The state and mobile peoples at the U.S.-Mexico border. In: Lem W, Gardiner Barber P, editors. Class, Contention, and a World in Motion. Oxford: Berghahn Press (2010). p. 58–78.

4. Sabo S, Shaw S, Ingram M, Teufel-Shone N, Carvajal S, de Zapien JG, et al. Everyday violence, structural racism and mistreatment at the US-Mexico border. Soc Sci Med (2014) 109:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.005

5. De Genova N. Working the Boundaries: Race, Space, and “Illegality” in Mexican Chicago. Durham, NC: Duke University Press (2005).

6. Menjívar C. Liminal legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan immigrants’ lives in the United States. Am J Sociol (2006) 111(4):999–1037. doi:10.1086/499509

7. Chavez L. The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press (2008).

8. Ngai M. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (2004).

9. Bourgois P. Recognizing invisible violence: a thirty-year ethnographic retrospective. In: Rylko-Bauer B, Whiteford L, Farmer P, editors. Global Health in Times of Violence. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press (2009). p. 17–40.

10. Bourdieu P, Wacquant L. Symbolic violence. In: Scheper-Hughes N, Bourgois P, editors. Violence in War and Peace: An Anthology. Malden, MA: Blackwell (2004). p. 272–4.

11. Coutin SB. Legalizing Moves: Salvadoran Immigrants Struggle for U.S. Residency. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press (2000).

13. Coutin SB. Denationalization, inclusion, and exclusion: negotiating the boundaries of belonging. Indiana J Global Leg Stud (2000) 7(2):585–93.

14. Golash-Boza TM. Immigration Nation: Raids, Detentions and Deportations in Post 9/11 America. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers (2012).

15. Martinez D, Slack J, Heyman JM. Bordering on Criminal: The Routine Abuse of Migrants in the Removal System. Part I: Migrant Mistreatment While in U.S. Custody. Washington, DC: American Immigration Council (2013).

16. Nevins J. Operation Gatekeeper and Beyond: The War on “Illegals” and the Remaking of the U.S.-Mexico Boundary. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge (2010).

17. Coleman M. Immigration geopolitics beyond the Mexico-US border. Antipode (2007) 39(1):54–76. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2007.00506.x

18. Golash-Boza TM. Due Process Denied: Detentions and Deportations in the United States. New York, NY: Routledge (2012).

19. Stumpf J. The crimmigration crisis: immigrants, crime, and sovereign power. Am Univ Law Rev (2006) 56(2):367–419.

20. Slack J, Martinez D, Whiteford S, Lee A. Border Militarization and Health: Violence, Death, and Security (2013). Available from: http://works.bepress.com/scott_whiteford/ (accessed 9, 2015)

21. Viruell-Fuentes EA. Beyond acculturation: immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Soc Sci Med (2007) 65:1524–35. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010

22. Quesada J, Kain Hart L, Bourgois P. Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Med Anthropol (2011) 30(4):339–62. doi:10.1080/01459740.2011.576725

23. Gonzales RG, Chavez L. “Awakening to a nightmare”: abjectivity and illegality in the lives of undocumented 1.5-generation Latino immigrants in the United States. Curr Anthropol (2012) 53(3):255–81. doi:10.1086/665414

24. Lee A. “Illegality,” health problems and return migration: cases from a migrant sending community, Puebla, Mexico. Reg Cohes (2013) 3(1):62–93. doi:10.3167/reco.2013.030104

25. McGuire S, Georges J. Undocumentedness and liminality as health variables. ANS Adv Nurs Sci (2003) 26(3):185–95. doi:10.1097/00012272-200307000-00004

26. Willen SS. Toward a critical phenomenology of “illegality”: state power, criminalization, and abjectivity among undocumented migrant workers in Tel Aviv, Israel. Int Migr (2007) 45(3):8–38. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2007.00409.x

28. Villarejo D, Lighthall D, Williams D, Souter A, Mines R. Suffering in Silence: A Report on the Health of Agricultural Workers. Berkeley, CA: California Institute for Rural Studies (2000).

29. Villarejo D, McCurdy S, Bade B, Samuels S, Lighthall D, Williams D. The health of California immigrant hired farmworkers. Am J Ind Med (2010) 53:387. doi:10.1002/ajim.20796

30. Alderete E, Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Lifetime prevalence of and risk factors among Mexican migrant farmworkers in California. Am J Public Health (2000) 90:608. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.4.608

31. Hovey J. Mental Health and Substance Abuse Migrant Health Monograph Series. 4th ed. Buda, TX: National Center for Farmworker Health Inc (2001). p. 18–35.

32. Rosales C, Carvajal S, McClelland J, Ingram M, Rubio-Goldsmith R, de Zapien J. Challenges to Farmworker Health at the US Mexico Border: A Report on Health Status of Yuma County Agricultural Workers. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona (2009).

33. Carvajal SC, Rosales C, Rubio-Goldsmith R, Sabo S, Ingram M, McClelland DJ, et al. The border community and immigration stress scale: a preliminary examination of a community responsive measure in two southwest samples. J Immigr Minor Health (2012) 15(2):427–36. doi:10.1007/s10903-012-9600-z

34. Koulish RE. US Immigration Authorities and Victims of Human and Civil Rights Abuses: The Border Interaction Project Study of South Tucson, Arizona, and South Texas. Tucson, AZ: Mexican American Studies & Research Center, University of Arizona (1994).

35. Goldsmith PR, Romero M, Rubio-Goldsmith R, Escobedo M, Khoury L. Ethno-racial profiling and state violence in a Southwest barrio. Aztlán (2009) 34(1):93–123.

37. De Genova N. The deportation regime: sovereignty, space, and the freedom of movement. In: De Genova N, Peutz N, editors. The Deportation Regime. Durham, NC: Duke University Press (2010). p. 33–65.

38. Aranda E, Menjívar C, Donato K. The spillover consequences of an enforcement-first U.S. immigration regime. Am Behav Sci (2014) 58(13):1687–95. doi:10.1177/0002764214537264

39. Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, Goldblatt P. Building of the global movement for health equity: from Santiago to Rio and beyond. Lancet (2011) 379(9811):181–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61506-7

40. CSDH. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva (2008).

41. Acevedo-Garcia D, Sanchez-Vaznaugh EV, Viruell-Fuentes EA, Almeida J. Integrating social epidemiology into immigrant health research: a cross-national framework. Soc Sci Med (2012) 75(12):2060–8. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.040

42. Hacker K, Chu J, Leung C, Marra R, Pirie A, Brahimi M, et al. The impacts of immigration and customs enforcement on immigration health: perceptions of immigrants in Everette, Massachusetts, USA. Soc Sci Med (2011) 73:586–94. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.007

43. Hardy L, Getrich C, Quezada J, Guay A, Michalowski R, Henley E. A call for further research on the impact of state level immigration policies on public health. Am J Public Health (2012) 102(7):1250–4. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300541

44. Viruell-Fuentes EA. “Its so hard”: racialization processes, ethnic identity formations, and their health implications. Du Boise Rev Washington, DC: American Immigration Council (2011) 8(1):37–52. doi:10.1017/S1742058X11000117

45. Martínez D, Slack J, Heyman J. “Migrant Mistreatment While in U.S. Custody.” Part I of Bordering on Criminal: The Routine Abuse of Migrants in the Removal System Washington, DC: American Immigration Council (2013).

46. Sustainable Business Coalition. Revitalize, not Militarize Campaign (2014). Available from: http://www.revitalizenotmilitarize.org/

Keywords: immigration policy, mistreatment, border health, stress, psychological, prevention and control

Citation: Sabo S and Lee AE (2015) The spillover of US immigration policy on citizens and permanent residents of Mexican descent: how internalizing “illegality” impacts public health in the borderlands. Front. Public Health 3:155. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00155

Received: 14 March 2015; Accepted: 20 May 2015;

Published: 11 June 2015

Edited by:

Rosemary M. Caron, University of New Hampshire, USAReviewed by:

Laura Rudkin, University of Texas Medical Branch, USAKathryn Welds, Curated Research and Commentary, USA

Copyright: © 2015 Sabo and Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Samantha Sabo, 1295 N Martin Avenue, Drachman Hall A268, Tucson, AZ 85621, USA,c2Fib0BlbWFpbC5hcml6b25hLmVkdQ==

Samantha Sabo

Samantha Sabo Alison Elizabeth Lee

Alison Elizabeth Lee