- 1Norwegian Centre for Integrated Care and Telemedicine, University Hospital of North Norway, Tromsø, Norway

- 2Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway

- 3Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International, Geneva, Switzerland

- 4Department of Medical Ethics and Legal Medicine (EA 4569), Paris Descartes University, Paris, France

- 5Fondation Médecins Sans Frontières, Paris, France

User surveys in telemedicine networks confirm that follow-up data are essential, both for the specialists who provide advice and for those running the system. We have examined the feasibility of a method for obtaining follow-up data automatically in a store-and-forward network. We distinguish between follow-up, which is information about the progress of a patient and is based on outcomes, and user feedback, which is more general information about the telemedicine system itself, including user satisfaction and the benefits resulting from the use of telemedicine. In the present study, we were able to obtain both kinds of information using a single questionnaire. During a 9-month pilot trial in the Médecins Sans Frontières telemedicine network, an email request for information was sent automatically by the telemedicine system to each referrer exactly 21 days after the initial submission of the case. A total of 201 requests for information were issued by the system and these elicited 41 responses from referrers (a response rate of 20%). The responses were largely positive. For example, 95% of referrers found the advice helpful, 90% said that it clarified their diagnosis, 94% said that it assisted with management of the patient, and 95% said that the telemedicine response was of educational benefit to them. Analysis of the characteristics of the referrers who did not respond, and their cases, did not suggest anything different about them in comparison with referrers who did respond. We were not able to identify obvious factors associated with a failure to respond. Obtaining data by automatic request is feasible. It provides useful information for specialists and for those running the network. Since obtaining follow-up data is essential to best practice, one proposal to improve the response rate is to simplify the automatic requests so that only patient follow-up information is asked for, and to restrict user feedback requests to the cases being assessed each month by the quality assurance panel.

Introduction

Follow-up is an integral part of consultation in medical practice. No doctor would give advice about a patient without attempting to follow the patient’s subsequent progress and/or trying to obtain some feedback. This basic principle is not altered when the consultation takes place at a distance (teleconsultation). Follow-up is part of routine clinical care, conducted in order to confirm that the situation is evolving as expected, and to allow the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment to be adjusted as appropriate. It is also important for doctors to learn from their successes and mistakes, as part of a reflective practice (1).

Thus, it is not surprising that surveys in telemedicine networks show that the specialists who provide advice wish to receive follow-up data about the cases they have worked on. In a survey of telemedicine users in Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), almost all specialists wanted follow-up information (52% considered follow-up desirable and 47% considered it necessary or mandatory) (2). In a survey of specialists in the Swinfen telemedicine network, 83% stated that they would like to receive follow-up information about the patient (3). We assume that provision of follow-up data is useful in keeping the specialists motivated, i.e., to ensure their continued participation in the telemedicine network and their availability to provide advice. It is also probably the only way that specialists can improve their service, since many of them will be based in high-income countries and without feedback it is impossible for them to know if their answers are useful; prompt feedback from the referrer may be perceived as a mark of gratitude for the service provided, which is important since many specialists volunteer their time and expertise for free. While it can reasonably be assumed that the provision of follow-up data is useful for many reasons, there is no literature about this (an experiment to test the assumption would be difficult, although not impossible).

Follow-up is also useful for those running the network, especially if a research study is to be conducted. Follow-up provides information about the value of the telemedicine consultations, and about the performance of individual specialists. Information about the latter is very valuable for the case coordinator in the allocation process, since experience shows that some specialists answer more quickly and comprehensively than others. Finally, providing follow-up data is probably a good discipline for the referrers, as it makes them think about the progress of their patients and about the value of the telemedicine advice they have received.

In the present paper, we distinguish between patient follow-up, which is information about the progress of a patient and is based on outcomes, and user feedback, which is more general information about the telemedicine system itself, including user satisfaction and the benefits resulting from the use of telemedicine.

Objectives

The primary research question was whether a method could be developed for obtaining follow-up data automatically in a general teleconsulting network, which was providing a service in low-resource settings. The secondary research question was whether it was feasible to obtain both follow-up data and user feedback simultaneously.

Methods

The present study required the development of a method to obtain data from the referrers and then a demonstration of its feasibility in practice. We combined the collection of both kinds of information into a single questionnaire, i.e., it represented a progress report.

The work was performed in two stages:

1. development of an information-collection tool;

2. demonstration of its feasibility in the MSF telemedicine network. Details of the network have been published elsewhere (2, 4).

Ethics permission was not required, because patient consent to access the data had been obtained and the work was a retrospective chart review conducted by the organization’s staff in accordance with its research policies.

Development of the Questionnaire

A questionnaire was developed by a consensus between three experienced telemedicine practitioners (two were medical specialists with field experience). It was based on accepted tools used in previous studies (3, 5). The final questionnaire was evaluated and approved by an independent evaluator.

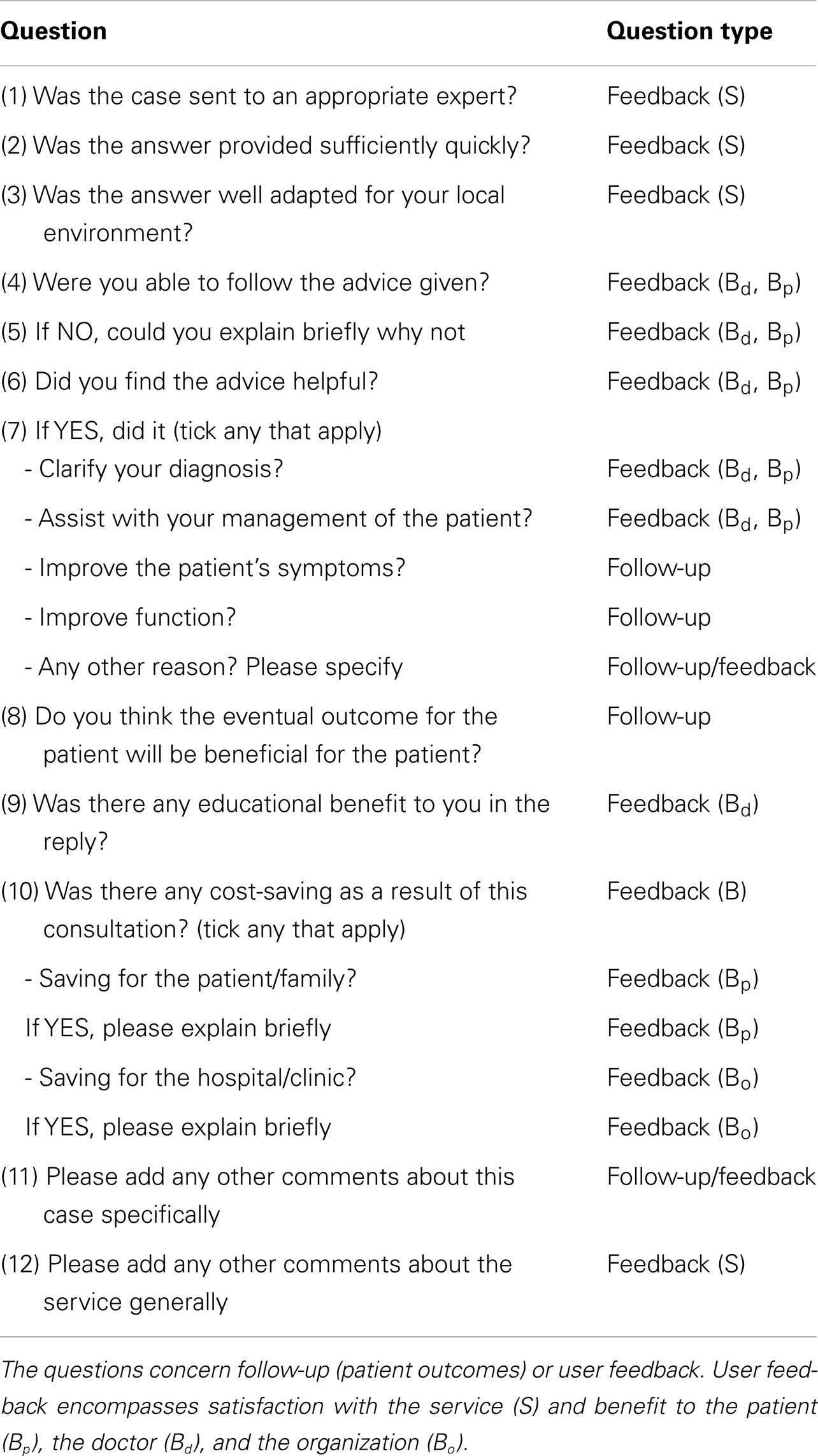

The final questionnaire consisted of 12 questions, which concerned both patient follow-up and user feedback, Table 1. The questions about follow-up concerned the referrer’s opinion about whether the eventual outcome would be beneficial for the patient. The questions about feedback concerned the referrer’s opinion about whether the process was satisfactory (e.g., the way that the referral had been handled in the telemedicine network) and what the benefits were, for the patient and doctor.

Automatic Request for Information

Modifications were made to the telemedicine system so that automatic requests for progress reports were sent to every referrer at a pre-determined interval after a new case had been submitted. The request allowed the referrer to log in to the server and then provided a link for the referrer to respond to the questionnaire.

Demonstration of Feasibility

To demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed approach, automatic requests for progress reports were issued in respect of cases submitted in the MSF telemedicine network for a 9-month period starting in October 2013. An email request was sent automatically by the telemedicine system to each referrer exactly 21 days after the initial submission of the case. When the referrer completed the progress report, an email notification was sent simultaneously to the expert(s) involved in the case and to the case-coordinators.

Analysis of Responses

Responses to the requests were analyzed approximately 4 weeks after the final request had been sent. The free-text comments were examined and, based on a content analysis, the main themes were extracted.

Results

Analysis of Responses

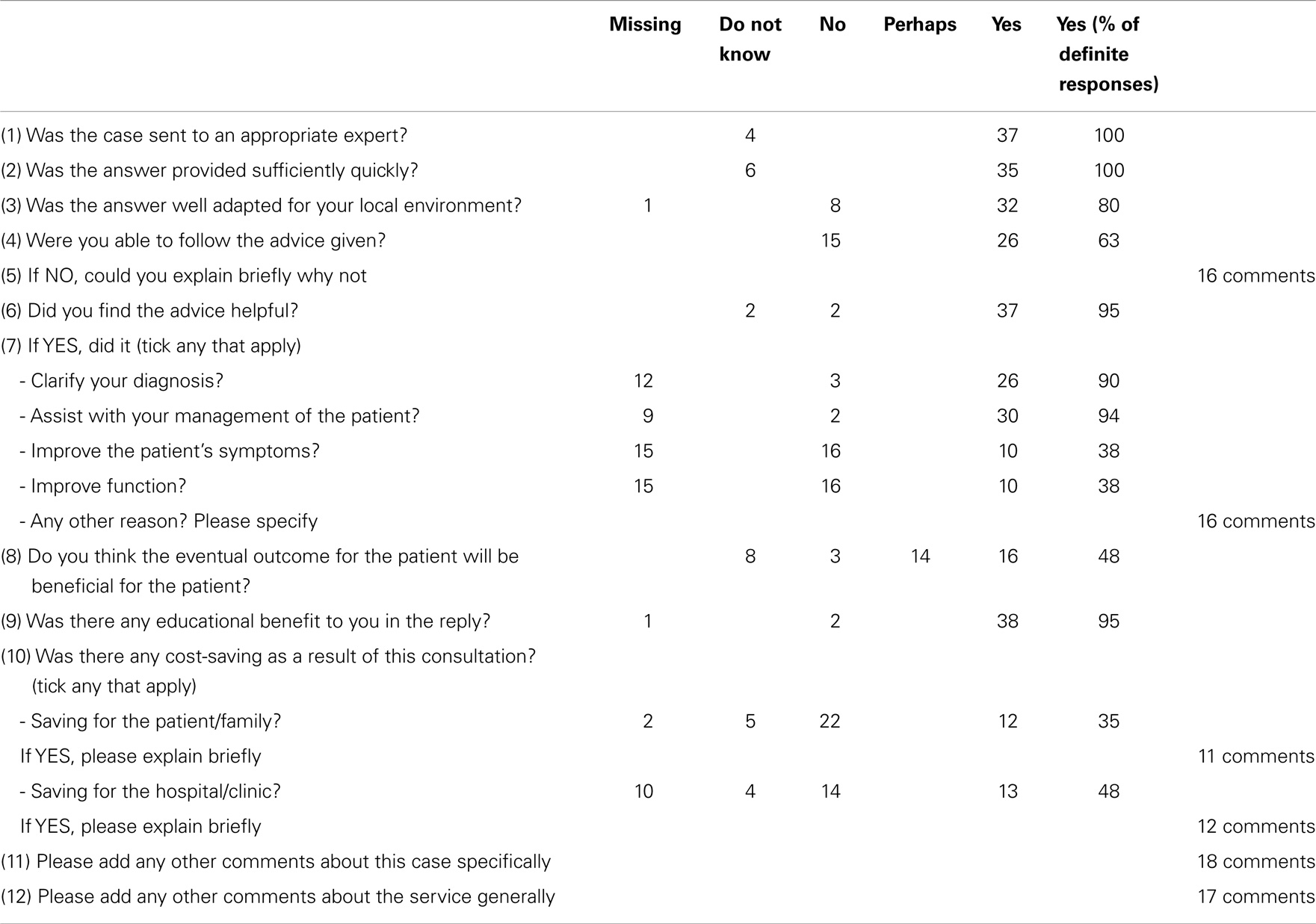

During the pilot trial, 201 requests for progress reports were issued by the system and these elicited 41 responses from referrers (a response rate of 20%). The responses were largely positive. For example, excluding the Do not know and Missing responses, 95% of referrers stated that they found the advice helpful, 90% said that it clarified their diagnosis, and 94% said that it assisted with management of the patient. In addition, 95% said that the telemedicine response was of educational benefit to them. The responses are summarized in Table 2.

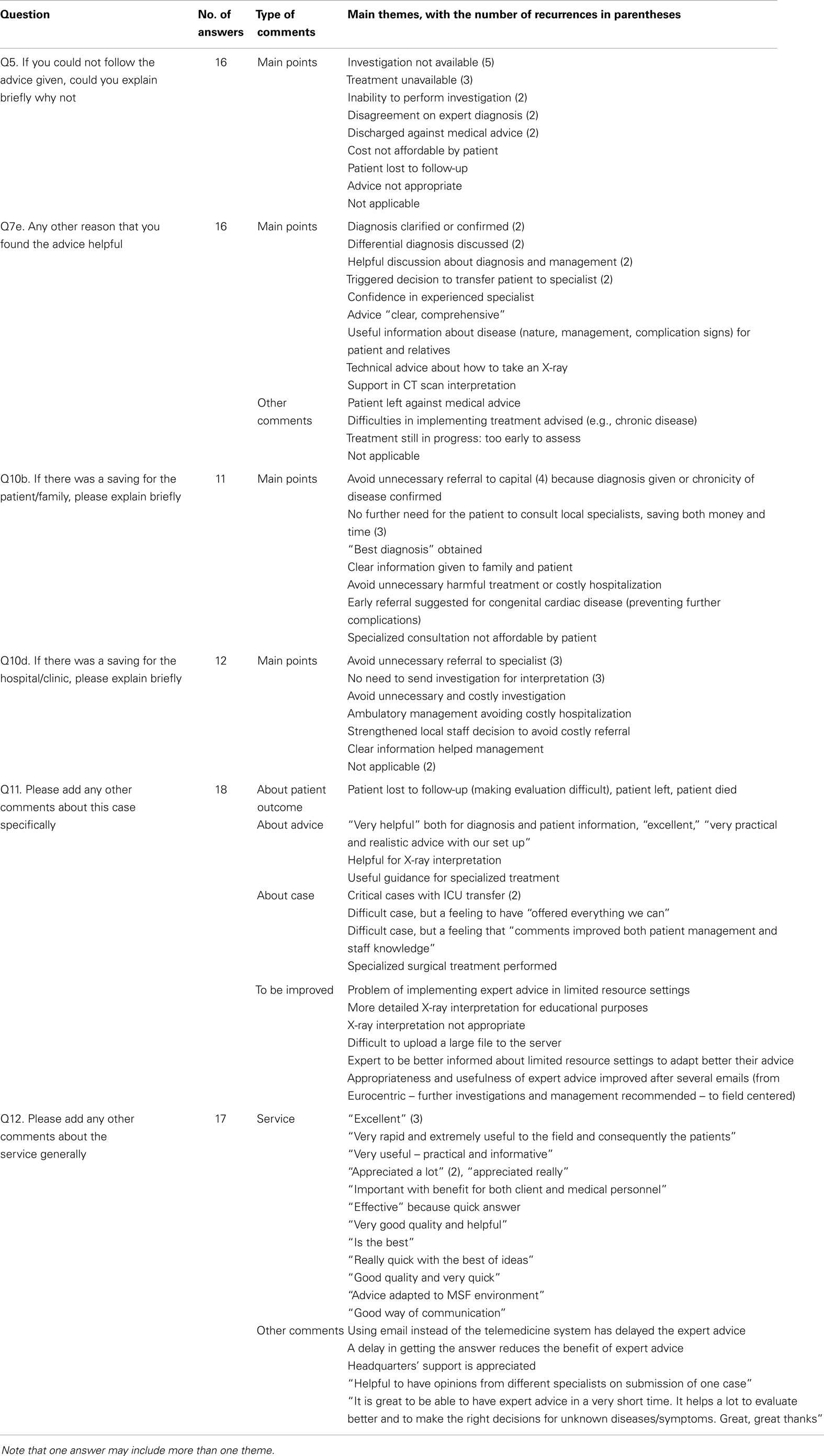

The qualitative analysis of the free comments confirmed this positive feedback from the responders, see Table 3. The expert advice was considered by the referrer as “clear, comprehensive, and useful,” helping both in the clinical management (diagnosis and management) and the information delivered to the patient and relatives. Referrers considered that the non-availability of an investigation or treatment that had been suggested was the main limitation in following the advice received. For this reason, some referrers emphasized the importance of making the expert aware of the constraints of the referral setting and the limited resources available.

Satisfaction with the system was also very high and the words used by responders emphasized the efficiency of the system (“excellent, very good quality, quick, practical …”). In terms of benefit, avoiding unnecessary referral to a higher level of health care or avoiding further specialized consultation were mentioned as the main reasons for cost savings.

Analysis of Non-Responses

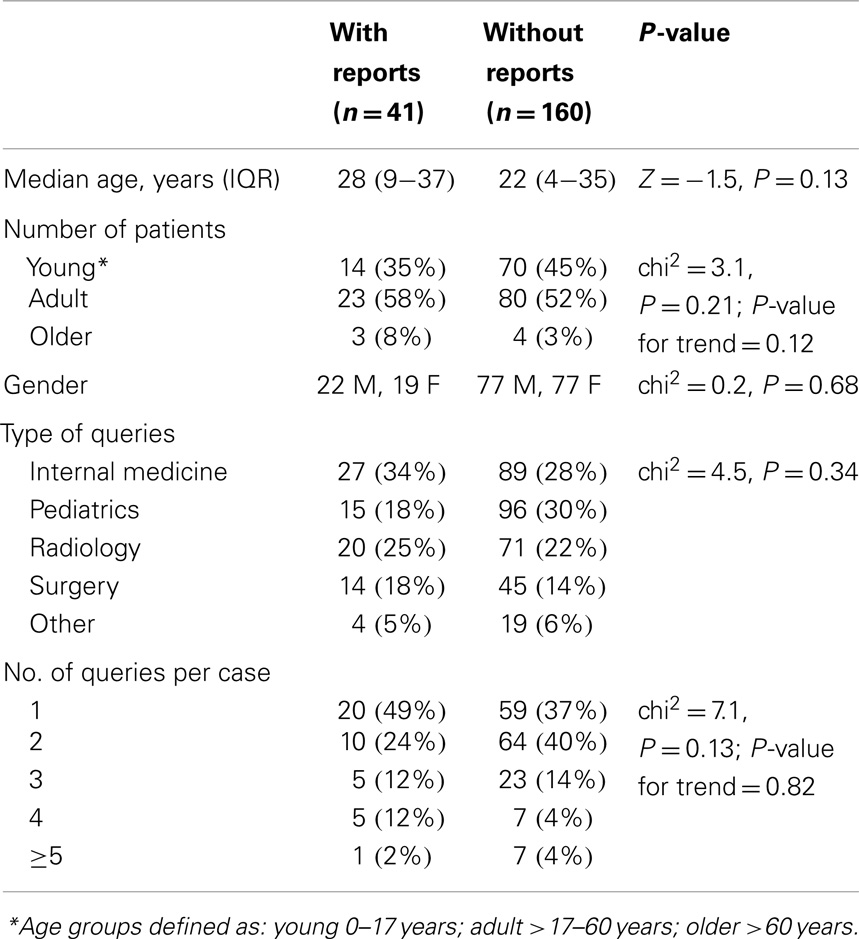

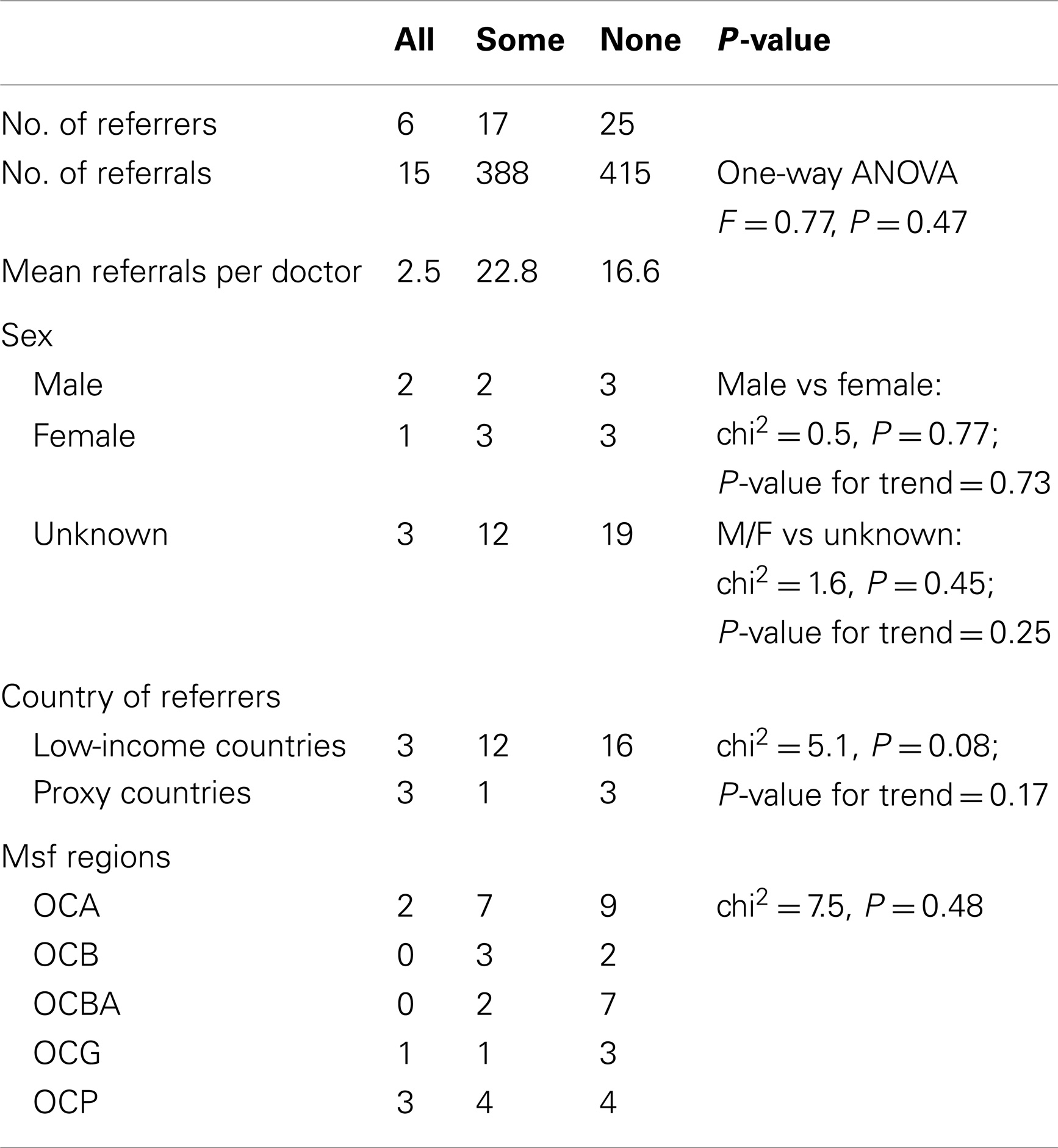

During the pilot trial, questionnaires were completed for 41 cases. That is, no questionnaire was completed for the other 160 cases. These two groups of cases might have differed in some way, and any difference might be a reason why the referrers decided to respond or not to respond. Various characteristics of the two groups were, therefore, compared. The median age of the patients in Group 1 (those with responses) was 27.5 years, and the median age of the patients in Group 2 (those without responses) was 22.0 years. However, the difference was not significant (P = 0.13). There were no significant differences in the gender of the patients in the two groups, nor the type of queries required to answer them, nor the number of queries for each case, see Table 4.

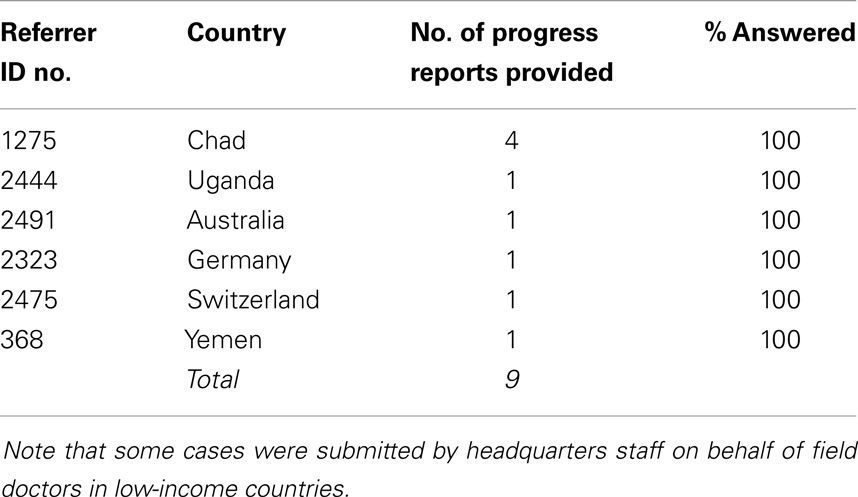

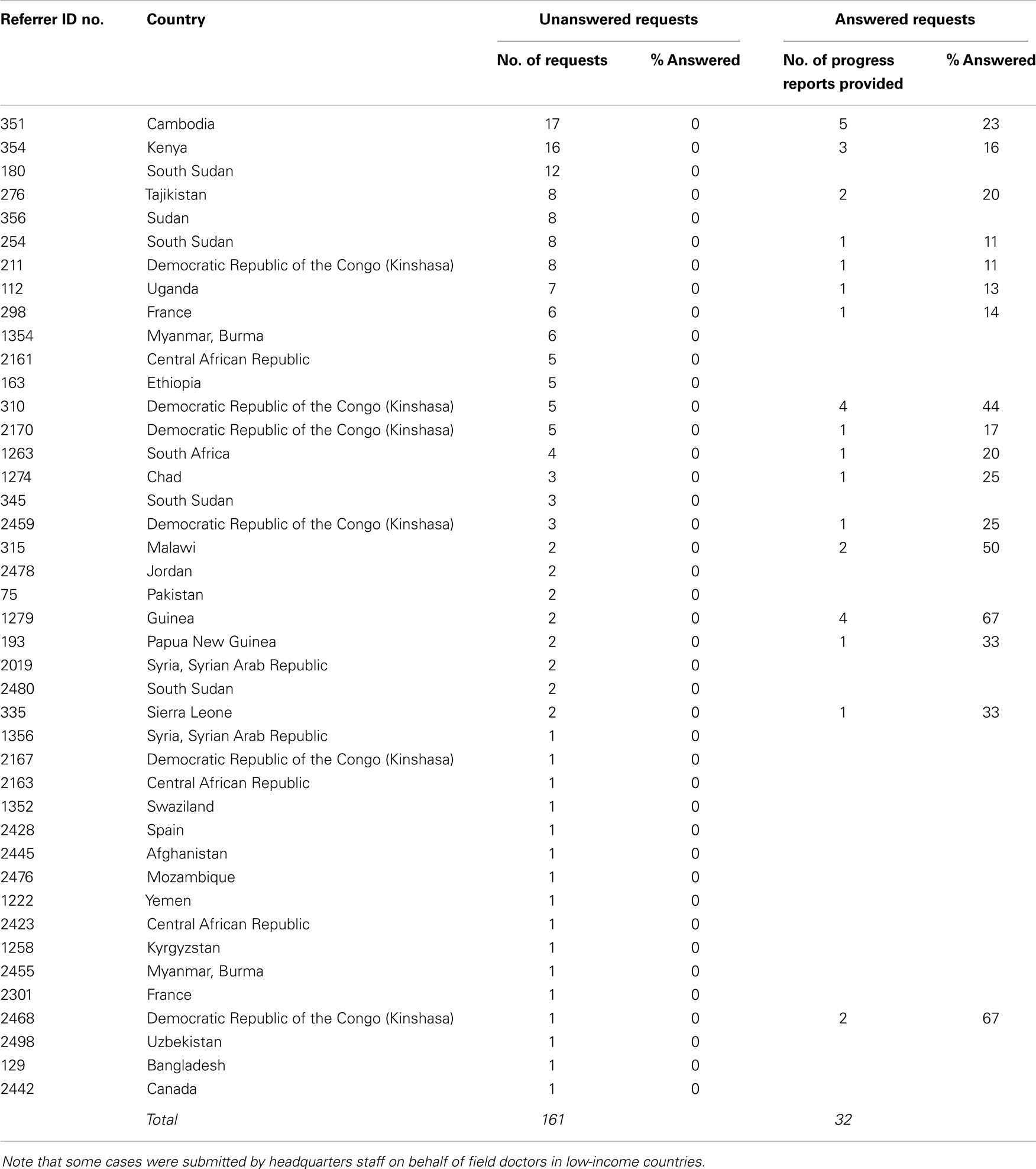

Responders and Non-Responders

Six referrers provided progress reports for every request they received, see Table 5. However, the majority provided either some reports, or none, see Table 6. There were no obvious differences between the three groups (responders to all, some, or none of the requests) in the characteristics available for comparison, see Table 7.

Discussion

The present work shows that both patient follow-up data and user feedback information can be obtained in a telemedicine network, via an automatic questionnaire. In a 9-month pilot trial, there was a response rate of 20%. How can we interpret this response rate? In physician surveys conducted in industrialized countries, a response rate of say 50–60% would be considered normal (6, 7). However, there is little published data about the response rate in online surveys of doctors in developing countries, and even less about the response rate in online surveys of doctors concerning the use of telemedicine in developing countries. A reasonable comparator is the study by Zolfo et al., of health-care workers using store-and-forward telemedicine in the management of difficult HIV/AIDS cases, which had a response rate of 19% (8).

The dangers of a low response rate are non-response bias (if the answers provided by respondents differ from the potential answers of those who do not answer), and response bias (if respondents tend to give answers that they believe that the questioner wants). Analysis of the characteristics of the referrers who did not respond, and the cases, did not suggest anything different about them in comparison with referrers who did respond. The comparison of referrers was, however, limited by the restricted information available about them. For reasons of information security, the telemedicine system stores little personal information about the users, and the accounts tend to be used by more than one person as staff are rotated through the field.

We were not able to identify obvious factors associated with a failure to respond. The response rate may, therefore, simply reflect the pressures of working in low-resource settings, and especially, the high turnover of field staff, which acts against the treating doctor being in post when a request for follow-up data is made some weeks later.

Measures to increase survey response rates are reasonably well understood, and include offering financial incentives, and following up online requests with copies of the survey sent out on paper. These are probably not appropriate in the present context. Nonetheless, it would seem prudent if this technique is to be adopted into routine service to try and increase the response rate. This raises a number of questions for future research:

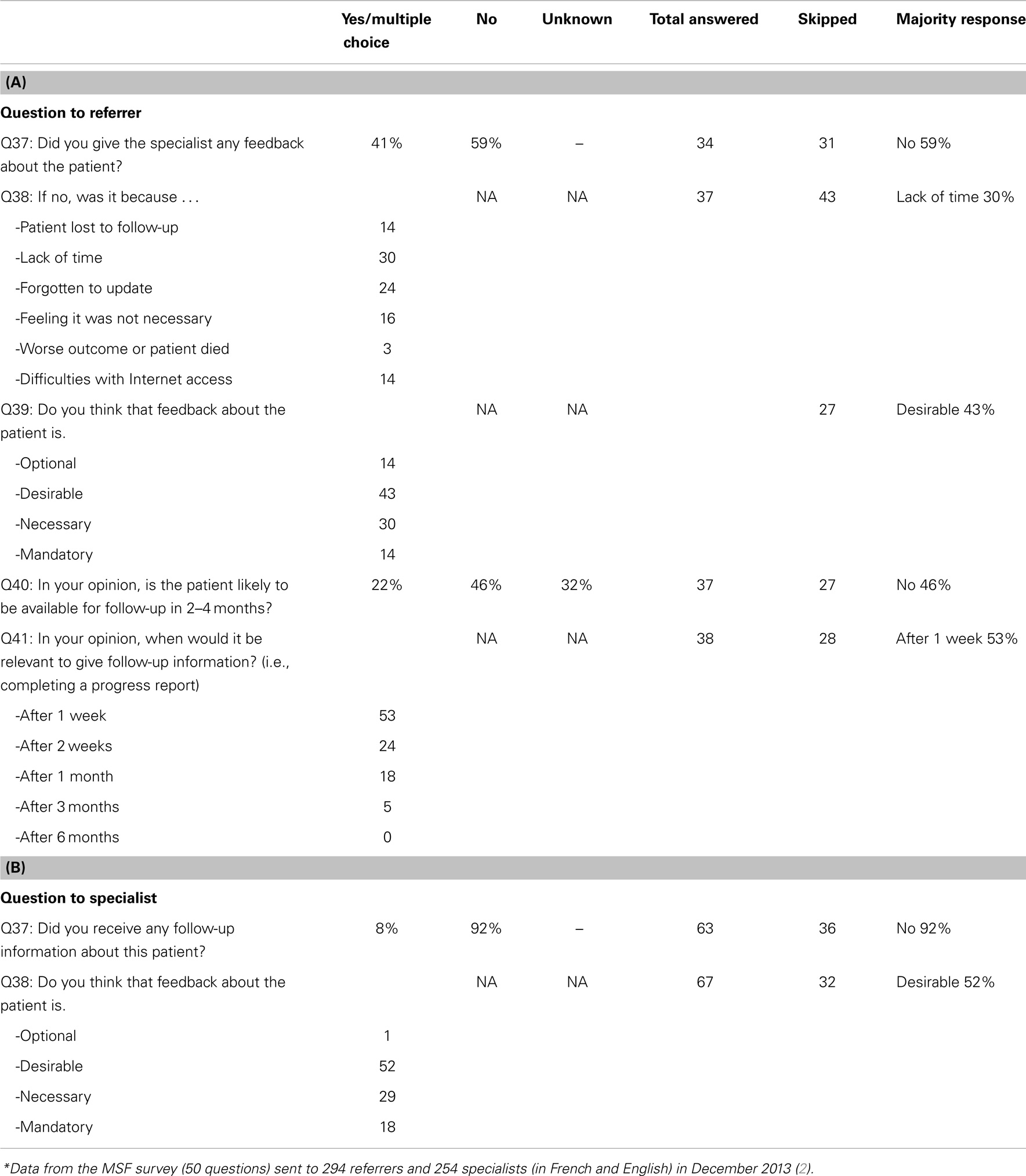

1. when should follow-up data be requested? i.e., is 21 days the right time? Other work (2) suggests that a shorter interval, such as 1 week, would be appropriate, see Table 8

2. is there an optimum time interval for all patients, or does the optimum time vary, depending on the specialty being consulted?

3. what is the right number of questions? i.e., is 12 questions too many? Reducing the survey to 2–3 questions might make a response more likely.

4. is it appropriate to ask for user feedback each time that a follow-up report is requested? Should requests for user feedback be made separately from requests for follow-up data (and less frequently)?

5. is a single follow-up report sufficient, or should there be say a short-term and a longer term report?

Table 8. Data from a previous survey,* (A) responses from referrers; (B) responses from specialists.

As mentioned in the Introduction, it is highly desirable to obtain follow-up data for each case. Even though there are other ways to obtain follow-up information, e.g., from the regular dialog between expert and referrer, the benefit of using an automatic request is that a standardized report is obtained for each case. Thus, the main problem in practice is the low response rate, and how best to encourage the referrer to complete the questionnaire. One potential way to increase the response rate would be to reduce the number of questions, in order to allow the referrer to answer within 1–2 min. As shown in a previous survey (2), the main reasons given for not answering were a lack of time > forgotten to update > patient lost to follow-up > difficulties with Internet access (Table 8). This is why we propose to separate the reporting of follow-up data from obtaining user feedback.

If user feedback is solicited separately from the follow-up data, then a natural time to request it would be when the monthly quality assurance (QA) review is conducted (9). This activity involves an expert panel making an assessment of a recent case that has been selected at random. If user feedback is requested from the referrer for the same case, then both the panel’s and the referrer’s views on the quality of the teleconsultation can be compared.

Finally, it is worth noting that specialists tend to underestimate the value of their responses. In a recent survey (3), Patterson examined the perceived value of telemedicine advice. There were 62 cases where it was possible to match up the opinions of the referrer and the consultants about the value of a specific teleconsultation. In 34 cases (55%), the referrers and specialists agreed about the value. However, in 28 cases (45%), they did not; specialists markedly underestimated the value of a consultation compared to referrers. A survey of MSF telemedicine users found a similar phenomenon (2). This reinforces the importance of obtaining user feedback from the referrers, who are best placed to evaluate the benefits to the patient.

Conclusion

Obtaining data from referrers by automatic request is feasible. The technique provides useful information for specialists and for those running the network. The modest response rate could be improved. Since obtaining follow-up information on each case is essential to best practice, a proposal to improve the response rate is to re-design the follow-up questionnaire to be as simple as possible, and to obtain user feedback separately, by sending a more detailed questionnaire in parallel with the randomly selected cases reviewed each month by the QA expert panel.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Will Wu for software support and Dr Olivier Steichen (AP-HP, Tenon Hospital, Paris) for helpful comments.

References

1. Plack MM, Greenberg L. The reflective practitioner: reaching for excellence in practice. Pediatrics (2005) 116(6):1546–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0209

2. Bonnardot L, Liu J, Wootton E, Amoros I, Olson D, Wong S, et al. The development of a multilingual tool for facilitating the primary-specialty care interface in low resource settings: the MSF tele-expertise system. Front Public Health (2014) 2:126. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00126

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Patterson V, Wootton R. A web-based telemedicine system for low-resource settings 13 years on: insights from referrers and specialists. Glob Health Action (2013) 23(6):21465. doi:10.3402/gha.v6i0.21465

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Halton J, Kosack C, Spijker S, Joekes E, Andronikou S, Chetcuti K, et al. Teleradiology usage and user satisfaction with the telemedicine system operated by Médecins Sans Frontières. Front Public Health (2014) 2:202. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00202

5. Wootton R, Menzies J, Ferguson P. Follow-up data for patients managed by store and forward telemedicine in developing countries. J Telemed Telecare (2009) 15(2):83–8. doi:10.1258/jtt.2008.080710

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol (1997) 50(10):1129–36. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00126-1

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Flanigan TS, McFarlane E, Cook S. Conducting survey research among physicians and other medical professionals – a review of the current literature. Proceedings of the Survey Research Methods Section. Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association (2008) p. 4136–47. Available from: https://www.amstat.org/Sections/Srms/Proceedings/

8. Zolfo M, Bateganya MH, Adetifa IM, Colebunders R, Lynen L. A telemedicine service for HIV/AIDS physicians working in developing countries. J Telemed Telecare (2011) 17(2):65–70. doi:10.1258/jtt.2010.100308

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Wootton R, Liu J, Bonnardot L. Assessing the quality of teleconsultations in a store-and-forward telemedicine network. Front Public Health (2014) 2:82. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00082

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: telemedicine, telehealth, quality assurance, quality control, LMICs

Citation: Wootton R, Liu J and Bonnardot L (2014) Quality assurance of teleconsultations in a store-and-forward telemedicine network – obtaining patient follow-up data and user feedback. Front. Public Health 2:247. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00247

Received: 06 August 2014; Accepted: 07 November 2014;

Published online: 24 November 2014.

Edited by:

Connie J. Evashwick, George Mason University, USAReviewed by:

Armin D. Weinberg, Life Beyond Cancer Foundation, USAJay E. Maddock, University of Hawaii at Manoa, USA

Frederick North, Mayo Clinic, USA

Copyright: © 2014 Wootton, Liu and Bonnardot. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Richard Wootton, Norwegian Centre for Integrated Care and Telemedicine, University Hospital of North Norway, PO Box 6060, 9038 Tromsø, Norway e-mail:cl93b290dG9uQHBvYm94LmNvbQ==

Richard Wootton

Richard Wootton Joanne Liu3

Joanne Liu3 Laurent Bonnardot

Laurent Bonnardot