95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 26 August 2014

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 2 - 2014 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00126

This article is part of the Research Topic Telemedicine in Low-Resource Settings View all 18 articles

Laurent Bonnardot1,2*

Laurent Bonnardot1,2* Joanne Liu3,4

Joanne Liu3,4 Elizabeth Wootton5

Elizabeth Wootton5 Isabel Amoros6

Isabel Amoros6 David Olson7

David Olson7 Sidney Wong8

Sidney Wong8 Richard Wootton9,10

Richard Wootton9,10

In 2009, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) started a pilot trial of store-and-forward telemedicine to support field workers. One network was operated in French and one in English; a third, Spanish network was brought into operation in 2012. The three telemedicine pilots were then combined to form a single multilingual tele-expertise system, tailored to support MSF field staff. We conducted a retrospective analysis of all telemedicine cases referred from April 2010 to March 2014. We also carried out a survey of all users in December 2013. A total of 1039 referrals were received from 41 countries, of which 89% were in English, 10% in French, and 1% in Spanish. The cases covered a very wide range of medical and surgical specialties. The median delay in providing the first specialist response to the referrer was 5.3 h (interquartile range 1.8, 16.4). The survey was sent to 294 referrers and 254 specialists. Of these, 224 were considered as active users (41%). Out of the 548 users, 163 (30%) answered the survey. The majority of referrers (79%) reported that the advice received via the system improved their management of the patient. The main concerns raised by referrers and specialists were the lack of support or promotion of system at headquarters’ level and the lack of feedback about patient follow-up. Because of the size of the MSF organization, it is clear that there is potential for further organizational adoption.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is an international, independent, and medical humanitarian organization that responds to emergency situations and provides medical assistance to people in need affected by armed conflict, epidemics, natural disasters, and exclusion from healthcare (1). A defining characteristic of the organization is its innovation (2). Over the years, MSF has developed considerable expertise in pioneering new technology for resource-limited settings in different fields, such as medical (e.g., automated TB diagnostic testing (GeneXpert), malaria Rapid Diagnostic Test) or logistical (e.g., inflatable hospitals with operating theaters, oxygen concentrators, vaccination kit).

It is not surprising, then, that MSF should take advantage of new information technology to improve the quality of health care for patients in low-resource settings. The work in question began in 2009, when MSF started a pilot trial of two telemedicine systems to support field workers. One was operated in French and one in English; a third, Spanish system was brought into operation in 2012. They were established initially in collaboration with the Swinfen Charitable Trust (3). In late 2013, the three telemedicine pilots were combined into a single multilingual system, using technology based on the Collegium Telemedicus system (4). Because of the constraints of MSF operations (e.g., legal, confidentiality, reporting), the multilingual system was established on a secure web server of its own, telemed.msf.org.

The product of this 4-year development period is a tele-expertise system, tailored to support MSF field staff. It is based on a highly secure web messaging system (see Box 1). It aims to facilitate the primary-specialty care interface by allowing a primary care physician to obtain an expert second opinion about a difficult clinical problem within a few hours.

Box 1. The MSF tele-expertise system.

Purpose

A tool for use in the field to improve access to specialized clinical advice. It is available in English, French, and Spanish.

Workflow

(1) Referrer logs in at https://telemed.msf.org using any web browser. Then submits a clinical case, including attachments if appropriate (e.g., pictures, video clips).

(2) Case-coordinator reviews the referral and allocates the case to an appropriate specialist. If there is no answer within 24 h, the case-coordinator re-allocates the case to another specialist.

(3) Specialist is notified by email that there is a referral requiring advice, logs in, and answers the case. The specialist can conduct a direct dialog with the referrer if required.

Method of operation

A secure, web-based messaging system. Confidentiality is ensured by removing any identifying patient data. Email is only used for notifications (i.e., that a case has been submitted or an answer received) and for advisory messages (e.g., login reminder).

Example

Clinical case sent through MSF tele-expertise system.

The aim of the present study was:

1. to review telemedicine activity in the first 4 years

2. to assess user satisfaction with the system.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of all cases referred from April 2010 to March 2014. Information relating to the cases was extracted from the database of the tele-expertise system. Ethics permission was not required, because patient consent to access the data had been obtained and the work was a retrospective chart review conducted by the organization’s staff in accordance with its research policies.

We also carried out a survey of all users in December 2013. The survey contained 50 questions. These were closed-ended, multiple-choice, and scale type questions, and open-ended questions. The questions were established after literature research combined with qualitative data collection (in-depth interview and participating observation). The survey was tested on three referrers and three specialists, in English and in French. After the pilot testing, the survey was sent to all referrers and specialists registered in the database, regardless of whether or not they were active (i.e., had logged in and sent or answered cases). Versions of the survey were made available in French and English. Web-based software (https://www.surveymonkey.com/) was used for collecting the data.

Data were examined with the usual methods for quantitative analysis, while the results of the open-ended questions were processed in a qualitative way. The present paper reports a preliminary analysis of the survey results.

Over a 4-year period, the tele-expertise system evolved from separate, single-language telemedicine networks to an integrated, multilingual system. This encompassed:

300 field health workers from all MSF operational centers (French, Dutch, Belgium, Spanish, and Swiss)

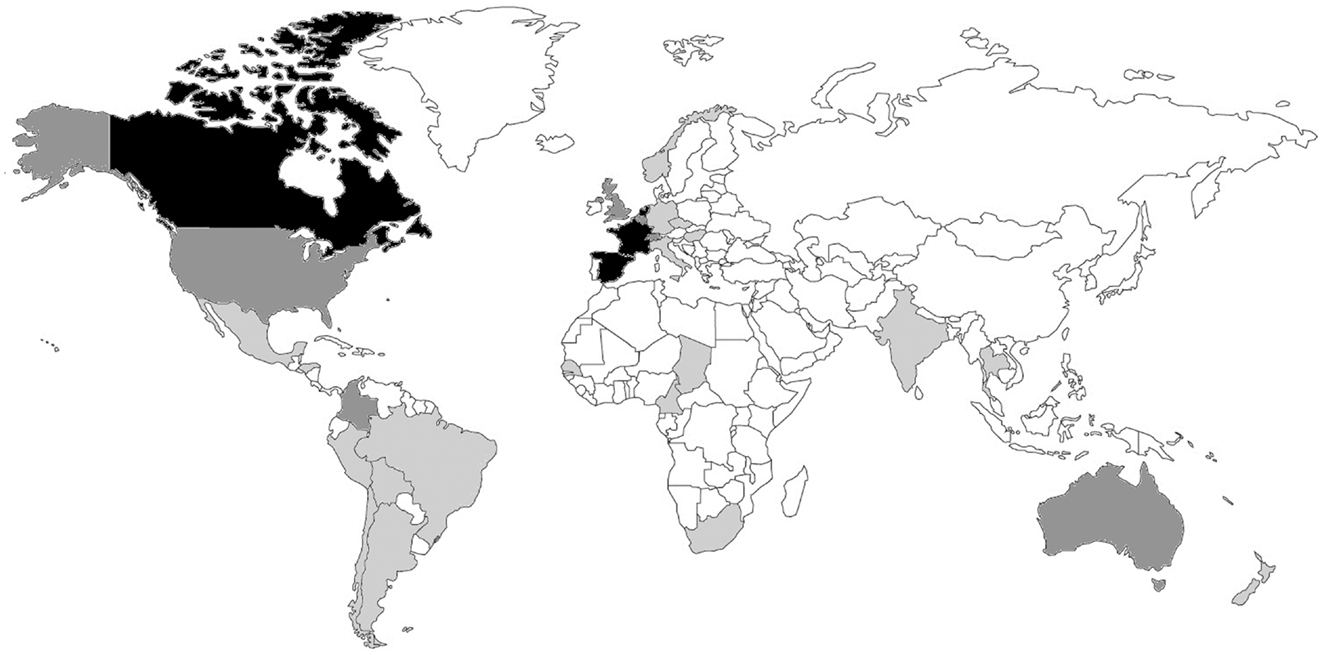

250 volunteer specialists from all over the world (Figure 1). The specialists cover most of the medical and surgical specialties; 90% have direct MSF or field experience

9 case-coordinators, who are volunteers:

1 in each language (English, French, Spanish);

1 within each of the 5 MSF operational centers;

1 for radiological cases

2 software engineers (part-time).

Figure 1. Country of origin of the specialists (n = 269). The countries are shaded: light gray, <5 specialists; dark gray, 5–25 specialists; black, >25 specialists.

During the 4-year study period, the caseload rose in the first 2 years and subsequently stabilized at about 1–2 cases/day (Figure 2). The peak was mainly the result of radiology cases submitted from a single hospital in the Central African Republic, which had no radiological expertise available on-site. Fluctuations were mainly related to specific implementation episodes and to promotion in presentations to the organization’s staff.

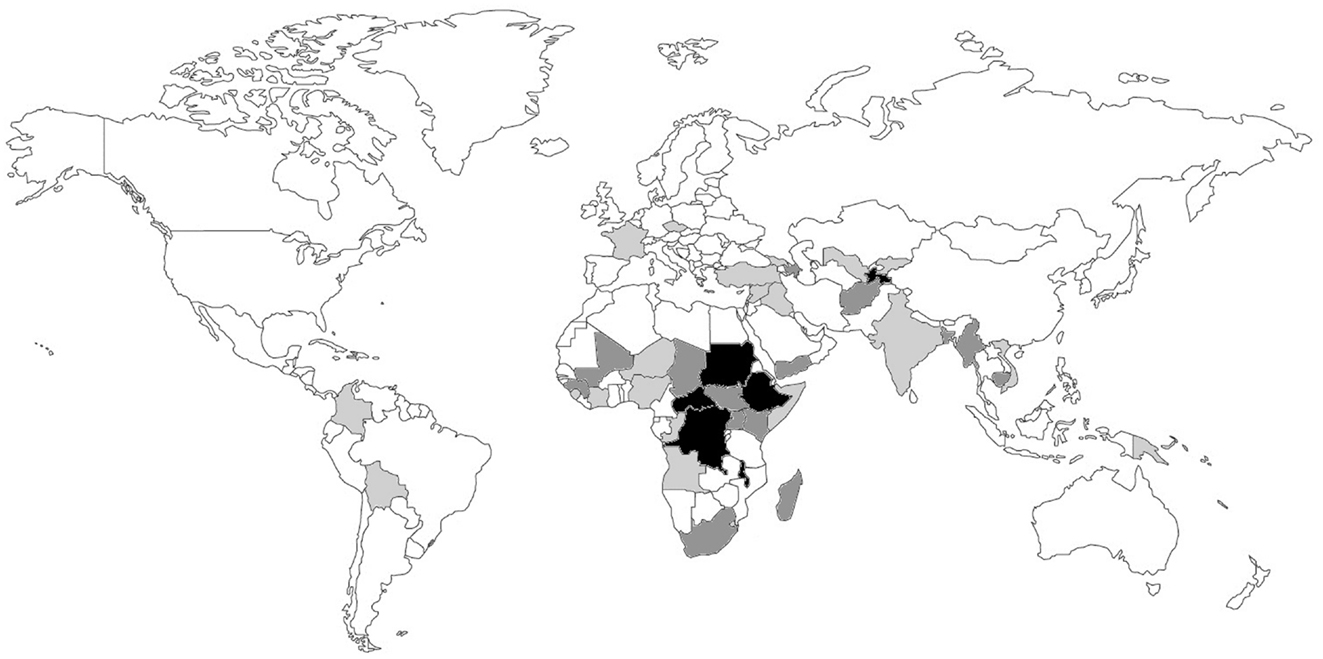

A total of 1039 referrals were received from 41 countries (Figure 3), of which 89% were in English, 10% in French, and 1% in Spanish.

Figure 3. Country of origin of the telemedicine cases (n = 1039). The countries are shaded: light gray, <5 cases; dark gray, 5–50 cases; black, >50 cases. The country of origin could not be determined in a small proportion of cases (1.2%).

The majority of the case allocations were done by four case-coordinators (93%). The median delay in allocating a new case was 0.5 h (interquartile range, IQR 0.17, 1.9). The median delay in providing the first specialist response to the referrer was 5.3 h (IQR 1.8, 16.4).

Two-thirds of the cases (66%) required a single allocation (also known as a query) to produce a specialist response, while one-third of the cases required more than one allocation. The mean number of allocations per case was 1.51 (Figure 4). The median number of messages per case was 4 (IQR 3, 6).

The cases covered a very wide range of medical and surgical specialties (Table 1). The most common type of referral was for radiology (44%), which reflected the difficulties being experienced at a small number of hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa.

The majority of the cases were submitted by relatively few referrers (see Figure 5). For example, 80% of cases were submitted by only 10% of the referrers.

Similarly, the majority of queries were answered by relatively few specialists (see Figure 6). For example, 80% of queries were sent to only 16% of all specialists.

The survey was sent to 294 referrers and 254 specialists. Of these, 224 were considered as active users (41%). Out of the 548 users, 163 (30%) answered the survey. The survey was completed reasonably promptly by the majority of the respondents: 70% questionnaires were completed within 6 days. Responses from French and English users were analyzed together.

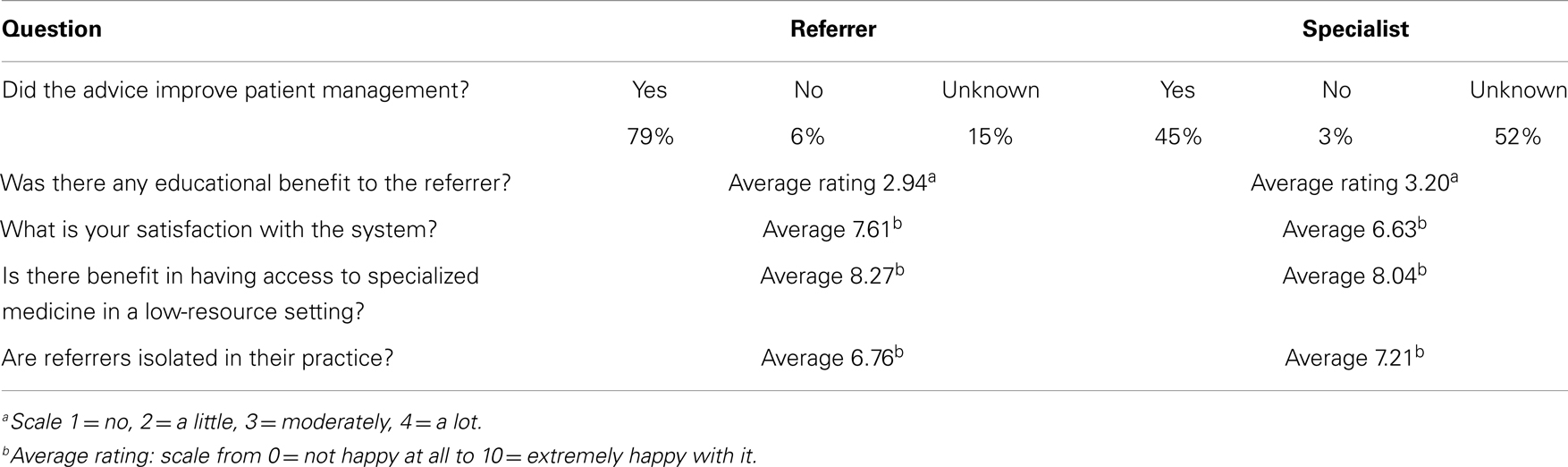

The survey results were generally positive (Tables 2A,B) demonstrating a high level of user participation, despite the questionnaire being rather long (50 questions).

The main features of the users and their IT habits are shown in Table 3. Answers to questions related to satisfaction and the benefits of system use are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Although many users skipped this part of the survey, this was mainly because the questions could not be answered unless the respondent had actually used the tele-expertise system.

Table 4. Comparison of referrer and specialist opinions about the benefits and satisfaction with the system.

A summary of the commonly-occurring referrer and specialist comments made in response to the open-ended questions are shown in Tables 5 and 6. The main concerns raised by referrers and specialists were the lack of support or promotion of system at headquarters’ level and the lack of feedback about patient follow-up.

Médecins Sans Frontières has previously used both store-and-forward and real-time telemedicine (5, 6). Although the real-time telemedicine work was considered successful, the requirement for good quality Internet connections makes real-time telemedicine much more expensive than store-and-forward work. Cost is crucial in the humanitarian context or in places which have very few resources. Indeed, the consequences of wastage that would have little effect on health care in high income countries can have a profound impact in low-resource settings. Store-and-forward telemedicine certainly has disadvantages in comparison with real-time telemedicine – principally, the interaction between the parties is not as immediate – but it also has considerable advantages: it is cheaper and it is easier to organize. Thus in a low-resource setting, store-and-forward telemedicine is inherently more likely to be sustainable.

The present review shows that the experience of the MSF tele-expertise system is generally positive. At the time of writing, it is in its fifth year of operation, and as is well-known, many telemedicine projects fail to survive beyond their initial set-up phase (7). Another positive sign is that the referrers who sent cases continued to do so, an objective demonstration of their satisfaction with the system and its value to them.

Comments made by the volunteer specialists suggest that they were highly motivated and frequently expressed frustration about not getting enough cases. It is clear that the positive image of MSF worldwide has been a key factor in recruiting and keeping motivated our specialist volunteers.

The creation of the network, which was set up initially in a few months, is itself a kind of achievement. It reflects the global footprint of MSF, its considerable field expertise, and its multilingualism and multiculturalism: 550 users, 74 countries connected, and tele-expertise available in three languages from specialists with significant field experience.

Based on the user survey, it is clear that the tele-expertise system is easy to use and provides clinically useful diagnostic and management advice to clinicians in the field. The majority of referrers (79%) reported that the advice received via the system improved their management of the patient. In contrast, only about half of the specialists (45%) felt that the advice they had given would improve patient management while another half did not know/were not able to answer (unknown). The same phenomenon was reported in a recent survey of the users of the Swinfen telemedicine system (8). In the present study, the explanation may be that since many specialists had not answered any case, they were not in a position to comment on potential improvement.

Finally, if objective improvement in patent management remains to be demonstrated from the patient point of view, it is clear that there is a precious educational value for the referrers who take full advantage of expert advice and experience to assist them in overcoming their professional isolation.

The main limitation of the present study is that it was retrospective, and there was no control system to compare it with. On the other hand, the survey questionnaires were completed by both users and non-users of the system, which reduces the bias inherent in surveys that are only completed by system users.

The response rate to the survey was not as high as would be expected in an online survey of doctors in industrialized countries, where response rates of 50–60% can be achieved. However, in the context of an online survey of telemedicine doctors in low-resource settings, the response rate was reasonable. For comparison, a previous survey of an HIV telemedicine network had a response rate of only 19% (9). The dangers of a low response rate are non-response bias (if the answers of respondents differ from the potential answers of those who did not respond) and response bias (if respondents tend to give answers that they believe that the questioner wants). Since we are not aware of the opinions of the non-responders, this may represent a potential source of bias in the present work.

The two main lessons learned concern the uneven pattern of system usage and the relative lack of referrer feedback:

Although there are 550 registered users, only about half of them are active, i.e., have logged in and sent or answered cases. We believe that this is typical of large telemedicine systems of this type, but there appear to be few published reports for comparison. Furthermore, the distribution of activity among the active users was very uneven, e.g., 80% of cases were submitted by only 10% of the referrers, and 80% of queries were sent to only 16% of all specialists. This uneven pattern of usage may lead to the demotivation of specialists who agree to answer cases, but do not subsequently receive referrals. The uneven pattern of referrals may be a consequence of limited communication and promotion of the system by MSF, with little briefing of staff before their deployment to the field; both reflect a lack of political support to embrace telemedicine. In the future, positive attempts must be made to engage all users.

Feedback from the referrer about patient follow-up is crucial for quality improvement and is necessary to keep the volunteer specialists informed about cases that they have advised on. The lack of feedback from referrers may also lead some specialists to lose interest in continued participation. Almost all specialists request follow-up after a teleconsultation (52% considered follow-up desirable and 47% considered it necessary or mandatory), and most referrers acknowledge a willingness to provide it. The reasons for the relative lack of follow-up data are probably not due to an unwillingness to provide it by the referrers. The stated reasons include a lack of time and a feeling that it was unnecessary. In addition, it is the nature of MSF operations in conflict zones and other resource-limited settings that patients are often seen in hospital, treated, and then disappear, not being available for subsequent follow-up to take place. Despite these practical difficulties, we have recently established a system by which follow-up requests are sent to the referrer automatically by email after a predetermined interval. This may improve the feedback in future.

After 4 years of development, MSF has put into place a multilingual tele-expertise system to support workers in the field. User surveys confirm that the system provides helpful advice, which has a positive effect on patient outcomes. It is reliable and efficient. It improves patient management, has educational value for those involved, and reduces isolation for the referrers. Because of the size of the MSF organization, it is clear that there is potential for further organizational adoption. This will depend on political support from within the organization itself.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank the volunteer case-coordinators and specialists, who represent the cornerstone of the system. We are particularly grateful to Jean Rigal, Jean-Hervé Bradol, Marie Pierre Allié, Will Wu, Olivier Steichen, Christian Hervé, Ondine Ripka and the MSF legal department, Leslie Shanks, Katherine Gottwald, Raghu Venugopal, Pedro Pablo Pablo, Carme Baraldes, Eric Comte, Bertrand Draguez, Jean-Paul Jemmy, Saskia Spijker, Judith Herrera, Annette Heinzelmann, Micaela Serafini, Jarred Halton, Elisa Salvado, and all our field referrers.

1. Médecins Sans Frontières. MSF Activities. (2014). Available from: http://www.msf.org/msf-activities

2. Bradol J-H, Vidal C, editors. Medical Innovations in Humanitarian Situations. (2014). Available from: http://www.msf.org.au/fileadmin/specialfeatures/medical_innovations/medinnovbk.pdf

3. Patterson V, Swinfen P, Swinfen R, Azzo E, Taha H, Wootton R. Supporting hospital doctors in the Middle East by email telemedicine: something the industrialized world can do to help. J Med Internet Res (2007) 9(4):e30. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.4.e30

4. Wootton R, Wu WI, Bonnardot L. Nucleating the development of telemedicine to support healthcare workers in resource-limited settings: a new approach. J Telemed Telecare (2013) 19(7):411–7. doi:10.1177/1357633X13506511

5. Zachariah R, Bienvenue B, Ayada L, Manzi M, Maalim A, Engy E, et al. Practicing medicine without borders: tele-consultations and tele-mentoring for improving paediatric care in a conflict setting in Somalia? Trop Med Int Health (2012) 17(9):1156–62. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03047.x

6. Coulborn RM, Panunzi I, Spijker S, Brant WE, Duran LT, Kosack CS, et al. Feasibility of using teleradiology to improve tuberculosis screening and case management in a district hospital in Malawi. Bull World Health Organ (2012) 90(9):705–11. doi:10.2471/BLT.11.099473

7. Broens TH, Huis in’t Veld RM, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, Hermens HJ, van Halteren AT, Nieuwenhuis LJ. Determinants of successful telemedicine implementations: a literature study. J Telemed Telecare (2007) 13(6):303–9. doi:10.1258/135763307781644951

8. Patterson V, Wootton R. A web-based telemedicine system for low-resource settings 13 years on: insights from referrers and specialists. Glob Health Action (2013) 6:21465. doi:10.3402/gha.v6i0.21465

Keywords: telemedicine, telehealth, developing countries, tele-expertise, multilingual network

Citation: Bonnardot L, Liu J, Wootton E, Amoros I, Olson D, Wong S and Wootton R (2014) The development of a multilingual tool for facilitating the primary-specialty care interface in low resource settings: the MSF tele-expertise system. Front. Public Health 2:126. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00126

Received: 14 June 2014; Paper pending published: 15 July 2014;

Accepted: 07 August 2014; Published online: 26 August 2014.

Edited by:

Philip Baba Adongo, University of Ghana, GhanaReviewed by:

Wilma Alvarado-Little, AlvaradoLittle Consulting LLC, USACopyright: © 2014 Bonnardot, Liu, Wootton, Amoros, Olson, Wong and Wootton. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laurent Bonnardot, Fondation Médecins Sans Frontières, 8 Rue Saint Sabin, Paris 75011, France e-mail:bGJvbm5hcmRvdEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.