94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Psychiatry, 08 April 2025

Sec. Psychopharmacology

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1565852

Psychiatric disorders are marked by habitual patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior, and many mental health disorders are resistant to standard treatments (1–4). For example, symptoms of major depressive disorder include ruminative negative thoughts, pervasive sadness, and lack of goal-directed behavior (5–7). Similarly, many anxiety and trauma-related disorders are characterized by recurrent, intrusive, fear-based thoughts and patterns of avoidant behaviors (8, 9). In compulsive disorders, such as substance use disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and eating disorders, individuals repeatedly engage in maladaptive behaviors and thought patterns despite negative consequences (9). Even conditions as diverse as schizophrenia may show evidence of habitual thoughts in the form of recurrent hallucinations or delusions (10). These pervasive patterns across psychiatric disorders emphasize the role of ingrained neural habits, which perpetuate symptoms and hinder lasting recovery (2, 11).

In recent years, psychedelic therapies have emerged as promising potential treatments for a range of treatment-resistant psychiatric disorders (12–19). Despite efforts to classify psychedelics by subjective effects, chemical structure, or receptor targets, previous work suggests that these categories appear to have limited relevance to therapeutic applications, as diversely grouped psychedelics have shown promise in treating depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and addictions, and are consequently often defined simply by their ability to induce altered states of consciousness (20). Unlike traditional pharmacotherapies, which often require weeks or months of repeated sessions to produce measurable effects, psychedelics can induce rapid and long-lasting changes following only one or a few treatments (12, 14, 15, 21). Despite their diverse molecular structures and receptor targets, psychedelics share key similarities: they generate rapid-onset therapeutic effects and produce clinical benefits that endure well beyond their metabolic clearance (22). These enduring effects suggest that neuroplasticity may serve as the unifying core mechanism underlying their therapeutic action (22). While much attention has focused on their profound and often ineffable psychoactive phenomenology, psychedelics’ neurobiological mechanisms are equally germane.

Recent research has characterized psychedelics as belonging to a newly defined class of small-molecule pharmacotherapies called psychoplastogens (23). Derived from Greek roots for mind, plasticity and generation, psychoplastogens promote neuroplasticity within 24 to 72 hours of a single administration, a stark contrast to traditional pharmacotherapies, which may take weeks to yield similar effects (23). Neuroplasticity, commonly defined as the brain’s ability to reorganize and create new neural connections, plays a vital role in adaptation, learning, and recovery (24, 25). This capacity for change manifests at multiple levels of brain organization, including alterations in connectivity between brain regions, cellular modifications, and molecular adaptations that ultimately drive behavioral level changes (26).

Human neuroimaging studies offer compelling evidence of psychedelics’ impact on neuroplasticity, with multiple reviews detailing the significant changes in brain network connectivity after their administration (27–31). For example, increases in global brain connectivity and decreased network modularity have been associated with treatment response to psilocybin and ketamine, particularly in the prefrontal cortex (PFC); these findings may correlate with enhanced cognitive flexibility (27, 29, 30, 32, 33). Further, response to both ketamine and psilocybin is associated with decreased connectivity within the default mode network (DMN) limbic nodes, correlating with reduction in habitual, self-referential thought patterns (28, 30).

At the cellular level, psychoplastogens induce changes such as increased dendrite length, spine density, synaptic number, and intrinsic excitability, typically within 24 to 72 hours of a single dose (23, 34–37). However, different psychoplastogens may promote neuroplasticity through distinct effects. For instance, in preclinical models, ketamine increases the number of dendritic spines and enhances synaptogenesis, leading to increased synaptic density and strengthened connections between neurons, particularly in the prefrontal cortex (34). Similarly, positron emission tomography (PET) studies of ketamine have demonstrated increases in synaptic density in the human brain (38). Psilocybin, on the other hand, has been shown to robustly promote dendritic complexity, increasing the length and branching of dendritic spines, which enhances connectivity and communication with neighboring neurons (23).

At the molecular level, psychoplastogens engage key signaling pathways that drive synaptic growth and neural reorganization (23). For example, ketamine acts through the NMDA receptor, leading to a surge in glutamate release, AMPA receptor activation, and subsequent stimulation of pathways such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and mTOR, which support synaptogenesis and dendritic growth (22, 39–41). Similarly, MDMA modulates monoamine pathways, enhancing BDNF expression and synaptic plasticity (42, 43). Classical psychedelics like psilocybin primarily act as agonists at the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor, triggering cascades that promote synaptic signaling, increase dendritic complexity, and elevate neuroplasticity-related proteins (44). However, the implications of differing neuroplasticity effects on therapeutic efficacy are unknown.

On a behavioral level, studies have demonstrated that psychoplastogen administration can lead to significant changes in social learning, fear extinction, and adaptive behavior. For example, a Nature study found that diverse psychoplastogens enhance social learning by promoting neural plasticity in relevant brain circuits, while research on MDMA therapy has demonstrated its capacity to facilitate fear extinction learning (20, 45). Additionally, psychoplastogens have shown to reduce avoidance behaviors and promote behavioral activation (46). These behavioral changes align with observed neurobiological shifts, highlighting how psychoplastogens may translate molecular and cellular changes into meaningful clinical outcomes.

At face value, the ability of these compounds to catalyze neuroplasticity seems wholly beneficial. However, while neuroplasticity can allow the brain to appropriately adapt in the context of life experiences, it can also lead to maladaptive outcomes. Children with neglectful or abusive parents often develop maladaptive social tendencies, leading to difficulties in forming healthy relationships, increased vulnerability to anxiety or depression, and patterns of avoidant or aggressive behavior (47). This phenomenon, known as maladaptive plasticity, is also present in the reinforcement of harmful neural patterns, including those driving depression, addiction, anxiety, and PTSD (48–52).

This has important implications for psychedelic treatment design. For example, consider a hypothetical case of a combat veteran with PTSD who undergoes an unstructured psychedelic session. During the experience, the patient vividly re-experiences a traumatic memory but lacks the therapeutic support to process it effectively. Without proper integration, the session may inadvertently reinforce the brain’s fear circuits, leading to heightened hypervigilance and emotional reactivity. Instead of alleviating symptoms, the session could exacerbate the maladaptive patterns and further diminish adaptive regulation of fear responses.

This risk of maladaptive plasticity is not unique to PTSD. In substance use disorders, drug misuse strengthens reward pathways (51). As these circuits adapt, individuals experience heightened cravings and diminished sensitivity to natural rewards, perpetuating the addictive cycle (51). Over time, this plasticity can lead to compulsive behavior patterns that are resistant to change, even in the face of severe consequences (53, 54). Maladaptive plasticity also plays a role in chronic pain, where the brain continues to perceive pain signals even after the initial injury has healed, leading to a cycle of fear and avoidance behaviors (55–57). Consequently, neuroplasticity can be conceptualized as a double-edged sword. While it enables growth, learning, and recovery, it also underscores the importance of structured interventions to ensure that changes are beneficial.

Given that neuroplasticity can lead to either adaptive or maladaptive changes, how can clinicians selectively guide these effects toward positive outcomes? Neurorehabilitation models provide a constructive example of how neuroplasticity can be harnessed to selectively improve functioning and effect desired clinical outcomes. For example, after a stroke, spontaneous neuroplastic changes may occur, but are often insufficient for full recovery of lost functions (58, 59). Through targeted rehabilitation, therapy aims to retrain and reorganize the brain’s neural pathways to regain these abilities (26, 60). Physical therapy, for instance, focuses on repetitive movement to stimulate neuroplastic changes in the motor cortex, gradually rebuilding strength (60, 61). Speech therapy helps patients regain communication skills by stimulating the brain’s language centers (62). Occupational therapy focuses on adaptive functional recover of daily fine motor tasks, while cognitive therapy targets memory and attention deficits (63, 64). Without such synergistic and targeted therapeutic interventions, neuroplasticity may lead to maladaptive outcomes, such as learned nonuse of the affected limb or inefficient compensatory strategies (65). Structured, goal-directed therapy provides the necessary guidance to optimally channel neuroplastic changes.

Both historical and contemporary clinical literature underscore the role of psychotherapy in maximizing the therapeutic potential of neuroplasticity (66–71). Pioneering work on psychedelic therapies emphasized the necessity of structured therapeutic frameworks to translate the experiential insights of psychedelics into lasting behavioral change (69, 70). Such work has highlighted how psychotherapy not only supported safety and integration but also actively guided individuals toward adaptive change (72–74).

Psychoplastogen-assisted psychotherapeutic methods have differed across studies. For ethical conduct of research, a minimum standard includes basic preparatory psychoeducation about the nature of the psychoactive experience (75). However, a majority of psychedelic trials include additional preparatory therapeutic support, offering guidance on navigating non-ordinary states of consciousness, especially during intense or challenging emotions (13). Preparatory sessions are subsequently followed by one or more medication sessions, which includes at a minimum, supervision for safety if not psychological support or psychotherapy (13).

Post-medication therapy sessions, when included, often differ across clinical trials (13, 67, 76, 77). For instance, a few ketamine-assisted psychotherapy trials have utilized specific manualized psychotherapy platforms (e.g. motivational enhancement therapy, mindfulness-based therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy) (78–82). Additionally, many of the treatment-based psychoplastogen clinical trials include post-medication integratory psychotherapy sessions (13). These sessions are generally multimodal, drawing from a wide variety of therapeutic lineages, akin to the multimodal style commonly reported by practicing clinical therapists (13, 83), with the goal of translating psychological insights into positive actionable changes in daily life (84). For instance, the psychodynamic approach to therapy might be deliberately utilized to uncover unconscious patterns, emotions, and conflicts rooted in past experiences, this technique may be flexibly employed to help patients explore and process unconscious material and insights that emerges during the psychedelic experience (85–87). Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques may be used to help individuals identify and restructure negative thought patterns discovered during sessions (88–90). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) techniques can encourage patients to develop greater psychological flexibility, accept difficult emotions, and commit to meaningful action aligned with their values (90–92). Elements of motivational enhancement therapy (MET) may be integrated to help patients strengthen their intrinsic motivation for change and align their insights with concrete behavioral goals (93). Behavioral activation therapy techniques, may be utilized to encourage patients to engage in positive, rewarding activities that align with their values, while mindfulness practices may be employed to enhance self-awareness and emotional acceptance (94, 95).

Building on established psychotherapy techniques, psychedelic-assisted therapies offer a novel and promising approach to mental health treatment by harnessing the power of neuroplasticity. By opening up a “window of opportunity” for change, psychoplastogen-assisted therapy can help individuals deliberately break free from entrenched patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior, allowing a path forward towards enduring healing and growth. This process is reminiscent of critical periods in early development, where the brain is particularly sensitive to learning and environmental influences.

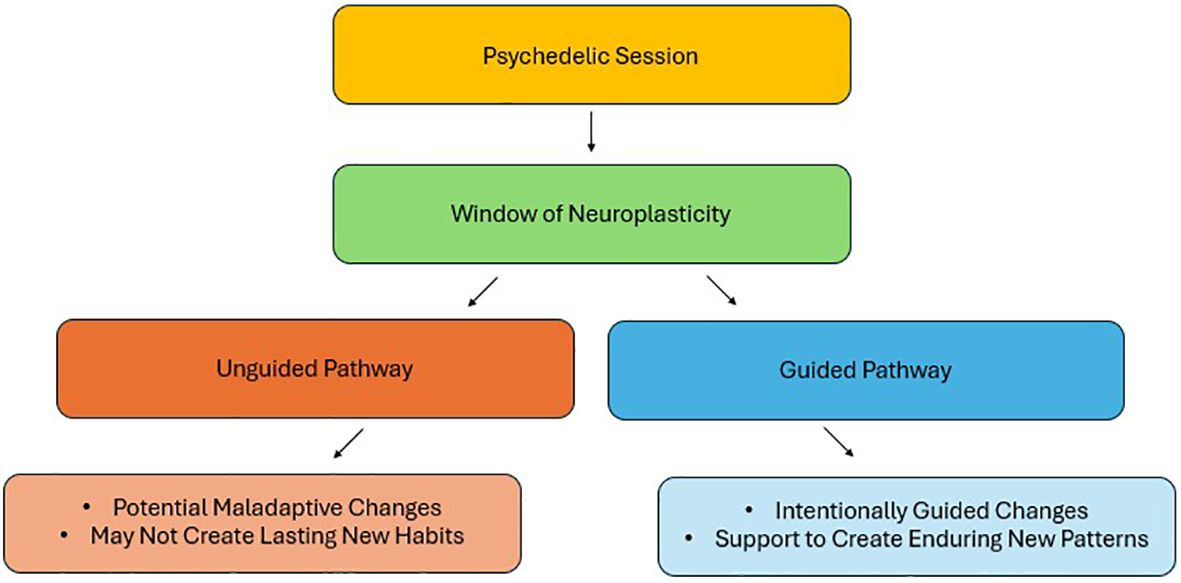

However, neuroplasticity is not inherently beneficial and requires careful therapeutic guidance to avoid maladaptive outcomes. Just as targeted, multimodal therapies are necessary to guide neuroplastic changes toward recovery following a stroke, psychotherapy is essential to direct psychedelic-induced neuroplasticity toward positive outcomes. Integrated psychotherapeutic approaches create a framework to translate the insights gained during psychedelic experiences into tangible behavioral and cognitive changes. Without therapeutic support however, the neuroplastic changes induced by psychedelics may be maladaptive, or not be properly consolidated, potentially limiting the durability and efficacy of treatment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Divergent pathways from the neuroplasticity window opened by psychedelics: adaptive vs. maladaptive outcomes.

As psychoplastogen treatments increasingly expand into clinical practice, personalized therapy approaches will likely be tailored to an individual’s unique clinical profile, such as incorporating motivational enhancement techniques for individuals with substance use disorders, leveraging cognitive-behavioral strategies or behavioral activation techniques to target major depressive disorder, or intentionally using somatic techniques to target dissociative tendencies. Consequently, therapist training and competency assessments may prove a better regulatory focus than rigid therapeutic protocols. Ultimately however, while psychedelics may open a window to neuroplastic change, it is the guiding hand of psychotherapy that will ensure the path chosen leads to positive mental health transformation.

JJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Admon R, Klavir O. Cognitive and behavioral patterns across psychiatric conditions. Brain Sci. (2021) 11:1560. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11121560

2. Colvin E, Gardner B, Labelle PR, Santor D. The automaticity of positive and negative thinking: A scoping review of mental habits. Cognit Ther Res. (2021) 45:1037–63. doi: 10.1007/s10608-021-10218-4

3. Woodhead S RT. The relative contribution of goal-directed and habit systems to psychiatric disorders. Psychiatria Danubin. (2017) 29:203–13.

4. Howes OD, Thase ME, Pillinger T. Treatment resistance in psychiatry: state of the art and new directions. Mol Psychiatry. (2022) 27:58–72. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01200-3

5. Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. (2000) 109:504–11. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504

6. Beblo T, Dehn LB. Clinical characteristics of emotional-cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder. In: Cognitive dimensions of major depressive disorder, vol. p. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press (2019). p. 87–99.

7. Hjartarson KH, Snorrason I, Bringmann LF, Ögmundsson BE, Ólafsson RP. Do daily mood fluctuations activate ruminative thoughts as a mental habit? Results from an ecological momentary assessment study. Behav Res Ther. (2021) 140:103832. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2021.103832

8. Smith BM, Smith GS, Dymond S. Relapse of anxiety-related fear and avoidance: Conceptual analysis of treatment with acceptance and commitment therapy. J Exp Anal Behav. (2020) 113:87–104. doi: 10.1002/jeab.v113.1

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing. (2013). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

10. Harrow M, Jobe TH. How frequent is chronic multiyear delusional activity and recovery in schizophrenia: a 20-year multi-follow-up. Schizophr Bull. (2010) 36:192–204. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn074

11. Gillan CM, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ, van den Heuvel OA, van Wingen G. The role of habit in compulsivity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2016) 26:828–40. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.12.033

12. Roth BL, Gumpper RH. Psychedelics as transformative therapeutics. Am J Psychiatry. (2023) 180:340–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.20230172

13. Horton DM, Morrison B, Schmidt J. Systematized review of psychotherapeutic components of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Am J Psychother. (2021) 74:140–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.20200055

14. Peixoto C, Santos FQ, Rego D, Medeiros H. Psychedelics and psychiatric disorders: A emerging role. Eur Psychiatry. (2021) 64:S776–6. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2054

15. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman J, Golsof S, Keeler J, Marsh B, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. (2021) 8:e19. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

16. Sharma R, Batchelor R, Sin J. Psychedelic treatments for substance use disorder and substance misuse: A mixed methods systematic review. J Psychoactive Drugs. (2023) 55:612–30. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2023.2190319

17. Zafar R, Siegel M, Harding R, Barba T, Agnorelli C, Suseelan S, et al. Psychedelic therapy in the treatment of addiction: the past, present and future. J. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1183740. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1183740

18. Rucker JJ, Jelen LA, Flynn S, Frowde KD, Young AH. Psychedelics in the treatment of unipolar mood disorders: a systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. (2016) 30:1220–9. doi: 10.1177/0269881116679368

19. Wolfgang AS, Fonzo GA, Gray JC, Krystal JH, Grzenda A, Widge AS, et al. MDMA and MDMA-assisted therapy. Am J Psychiatry. (2025) 182:79–103. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.20230681

20. Nardou R, Sawyer E, Song YJ, Wilkinson M, Padovan-Hernandez Y, de Deus JL, et al. Psychedelics reopen the social reward learning critical period. Nature. (2023) 618:790–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06204-3

21. Mendes FR, Costa C dos S, Wiltenburg VD, Morales-Lima G, Fernandes JAB, Filev R. Classic and non-classic psychedelics for substance use disorder: A review of their historic, past and current research. Addict Neurosci. (2022) 3:100025. doi: 10.1016/j.addicn.2022.100025

22. Aleksandrova LR, Phillips AG. Neuroplasticity as a convergent mechanism of ketamine and classical psychedelics. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2021) 42:929–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2021.08.003

23. Olson DE. Psychoplastogens: A promising class of plasticity-promoting neurotherapeutics. J Exp Neurosci. (2018) 12:1179069518800508. doi: 10.1177/1179069518800508

24. Voss P, Thomas ME, Cisneros-Franco JM, de-Villers-Sidani ÉChecktae. Dynamic brains and the changing rules of neuroplasticity: Implications for learning and recovery. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:1657. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01657

25. Marzola P, Melzer T, Pavesi E, Gil-Mohapel J, Brocardo PS. Exploring the role of neuroplasticity in development, aging, and neurodegeneration. Brain Sci. (2023) 13:1610. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13121610

26. Gillick BT, Zirpel L. Neuroplasticity: an appreciation from synapse to system. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2012) 93:1846–55. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.04.026

27. de Vos CMH, Mason NL, Kuypers KPC. Psychedelics and neuroplasticity: A systematic review unraveling the biological underpinnings of psychedelics. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:724606. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.724606

28. Zavaliangos-Petropulu A, Al-Sharif NB, Taraku B, Leaver AM, Sahib AK, Espinoza RT, et al. Neuroimaging-derived biomarkers of the antidepressant effects of ketamine. Biol Psychiatry Cognit Neurosci Neuroimaging. (2023) 8:361–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2022.11.005

29. Frautschi PC, Singh AP, Stowe NA, John-Paul JY. Multimodal neuroimaging of the effect of serotonergic psychedelics on the brain. Am J Neuroradiology. (2024) 45:833–40.

30. Kuburi S, Di Passa A-M, Tassone VK, Mahmood R, Lalovic A, Ladha KS, et al. Neuroimaging correlates of treatment response with psychedelics in major depressive disorder: A systematic review. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks). (2022) 6:24705470221115344. doi: 10.1177/24705470221115342

31. Ly C, Greb AC, Cameron LP, Wong JM, Barragan EV, Wilson PC, et al. Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity. Cell Rep. (2018) 23:3170–82. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.022

32. Gattuso JJ, Perkins D, Ruffell S, Lawrence AJ, Hoyer D, Jacobson LH, et al. Default mode network modulation by psychedelics: A systematic review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. (2023) 26:155–88. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyac074

33. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, Sexton JD, Wall MB, Erritzoe D, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. (2022) 28:844–51. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01744-z

34. Ly C, Greb AC, Vargas MV, Duim WC, Grodzki ACG, Lein PJ, et al. Transient stimulation with psychoplastogens is sufficient to initiate neuronal growth. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. (2021) 4:452–60. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00065

35. Shao L-X, Liao C, Gregg I, Davoudian PA, Savalia NK, Delagarza K, et al. Psilocybin induces rapid and persistent growth of dendritic spines in frontal cortex in vivo. Neuron. (2021) 109:2535–2544.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.06.008

36. Savalia NK, Shao L-X, Kwan AC. A dendrite-focused framework for understanding the actions of ketamine and psychedelics. Trends Neurosci. (2021) 44:260–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.11.008

37. Zhornitsky S, Oliva HNP, Jayne LA, Allsop ASA, Kaye AP, Potenza MN, et al. Changes in synaptic markers after administration of ketamine or psychedelics: a systematic scoping review. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1197890. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1197890

38. Holmes SE, Finnema SJ, Naganawa M, DellaGioia N, Holden D, Fowles K, et al. Imaging the effect of ketamine on synaptic density (SV2A) in the living brain. Mol Psychiatry. (2022) 27:2273–81. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01465-2

39. Dwyer JM, Duman RS. Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin and synaptogenesis: role in the actions of rapid-acting antidepressants. Biol Psychiatry. (2013) 73:1189–98. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.011

40. Cavalleri L, Merlo Pich E, Millan MJ, Chiamulera C, Kunath T, Spano PF, et al. Ketamine enhances structural plasticity in mouse mesencephalic and human iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons via AMPAR-driven BDNF and mTOR signaling. Mol Psychiatry. (2018) 23:812–23. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.241

41. Moliner R, Girych M, Brunello CA, Kovaleva V, Biojone C, Enkavi G, et al. Psychedelics promote plasticity by directly binding to BDNF receptor TrkB. Nat Neurosci. (2023) 26:1032–41. doi: 10.1038/s41593-023-01316-5

42. Rozas C, Loyola S, Ugarte G, Zeise ML, Reyes-Parada M, Pancetti F, et al. Acutely applied MDMA enhances long-term potentiation in rat hippocampus involving D1/D5 and 5-HT2 receptors through a polysynaptic mechanism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2012) 22:584–95. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.11.010

43. Young MB, Andero R, Ressler KJ, Howell LL. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine facilitates fear extinction learning. Transl Psychiatry. (2015) 5:e634. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.138

44. Vargas MV, Dunlap LE, Dong C, Carter SJ, Tombari RJ, Jami SA, et al. Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Science. (2023) 379:700–6. doi: 10.1126/science.adf0435

45. Maples-Keller JL, Norrholm SD, Burton M, Reiff C, Coghlan C, Jovanovic T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and fear extinction retention in healthy adults. J Psychopharmacol. (2022) 36:368–77. doi: 10.1177/02698811211069124

46. Zeifman RJ, Wagner AC, Watts R, Kettner H, Mertens LJ, Carhart-Harris RL. Post-psychedelic reductions in experiential avoidance are associated with decreases in depression severity and suicidal ideation. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:782. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00782

47. Riggs SA. Childhood emotional abuse and the attachment system across the life cycle: What theory and research tell us. In: The effect of childhood emotional maltreatment on later intimate relationships. New York, NY, USA: Routledge (2019). p. 5–51.

48. Price RB, Duman R. Neuroplasticity in cognitive and psychological mechanisms of depression: an integrative model. Mol Psychiatry. (2020) 25:530–43. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0615-x

49. Albert PR. Adult neuroplasticity: A new “cure” for major depression? J Psychiatry Neurosci. (2019) 44:147–50. doi: 10.1503/jpn.190072

50. Deppermann S, Storchak H, Fallgatter AJ, Ehlis A-C. Stress-induced neuroplasticity: (mal)adaptation to adverse life events in patients with PTSD–a critical overview. Neuroscience. (2014) 283:166–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.08.037

51. Chiamulera C, Piva A, Abraham WC. Glutamate receptors and metaplasticity in addiction. Curr Opin Pharmacol. (2021) 56:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2020.09.005

52. Shalev A, Cho D, Marmar CR. Neurobiology and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (2024) 181:705–19. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.20240536

53. O’Brien CP. Neuroplasticity in addictive disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2009) 11:350–3. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/cpobrien

54. Madsen HB, Brown RM, Lawrence AJ. Neuroplasticity in addiction: cellular and transcriptional perspectives. Front Mol Neurosci. (2012) 5:99. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00099

55. Li X-Y, Wan Y, Tang S-J, Guan Y, Wei F, Ma D. Maladaptive plasticity and neuropathic pain. Neural Plast. (2016) 2016:4842159. doi: 10.1155/2016/4842159

56. Gatchel RJ, Neblett R, Kishino N, Ray CT. Fear-avoidance beliefs and chronic pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. (2016) 46:38–43. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2016.0601

57. Crombez G, Eccleston C, Van Damme S, Vlaeyen JWS, Karoly P. Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: the next generation: The next generation. Clin J Pain. (2012) 28:475–83. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182385392

58. Sekerdag E, Solaroglu I, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y. Cell death mechanisms in stroke and novel molecular and cellular treatment options. Curr Neuropharmacol. (2018) 16:1396–415. doi: 10.2174/1570159X16666180302115544

59. Cassidy JM, Cramer SC. Spontaneous and therapeutic-induced mechanisms of functional recovery after stroke. Transl Stroke Res. (2017) 8:33–46. doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0467-5

60. Luft AR. Rehabilitation and plasticity. Clin recovery CNS damage. (2013) 32:88–94. doi: 10.1159/000348879

61. Caleo M. Rehabilitation and plasticity following stroke: Insights from rodent models. Neuroscience. (2015) 311:180–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.10.029

62. Brady MC, Kelly H, Godwin J, Enderby P, Campbell P. Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2016) 2016:CD000425. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4

63. Rowland T, Cooke D, Gustafsson L. Role of occupational therapy after stroke. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. (2008) 11:S99–107. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.41723

64. Manurung SS, Rumambo Pandin MG. Cognitive Therapy Approach for Post-Stroke Patients: A review of literature. medRxiv. (2023). doi: 10.1101/2023.12.15.23300013

65. Jang S. Motor function-related maladaptive plasticity in stroke: a review. NeuroRehabilitation. (2013) 32:311–6. doi: 10.3233/NRE-130849

66. Goodwin GM, Malievskaia E, Fonzo GA, Nemeroff CB. Must psilocybin always “assist psychotherapy”? Am J Psychiatry. (2024) 181:20–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.20221043

67. Cavarra M, Falzone A, Ramaekers JG, Kuypers KPC, Mento C. Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy—A systematic review of associated psychological interventions. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:887255. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.887255

68. Johansen L, Liknaitzky P, Nedeljkovic M, Murray G. How psychedelic-assisted therapy works for depression: expert views and practical implications from an exploratory Delphi study. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1265910. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1265910

69. Pahnke W, Kurland A, Unger S, Savage C, Grof S. The experimental use of psychedelic (LSD) psychotherapy. JAMA. (1970) 212:1856–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.1970.03170240060010

70. Grof S. The use of LSD in psychotherapy. J Psychedelic Drugs. (1970) 3:52–62. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1970.10471362

71. Grof S, Goodman LE, Richards WA, Kurland AA. LSD-assisted psychotherapy in patients with terminal cancer. Int Pharmacopsychiatry. (1973) 8:129–44. doi: 10.1159/000467984

72. Richards WA. Psychedelic psychotherapy: Insights from 25 years of research. J Humanist Psychol. (2017) 57:323–37. doi: 10.1177/0022167816670996

73. Gründer G, Brand M, Mertens LJ, Jungaberle H, Kärtner L, Scharf DJ, et al. Treatment with psychedelics is psychotherapy: beyond reductionism. Lancet Psychiatry. (2024) 11:231–6. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00363-2

74. Zamaria JA, Fernandes-Osterhold G, Shedler J, Yehuda R. Psychedelics assisting therapy, or therapy assisting psychedelics? The importance of psychotherapy in psychedelic-assisted therapy. Front Psychol. (2025) 16:1505894. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1505894

75. Johnson M, Richards W, Griffiths R. Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. J Psychopharmacol. (2008) 22:603–20. doi: 10.1177/0269881108093587

76. Brennan W, Belser AB. Models of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: A contemporary assessment and an introduction to EMBARK, a transdiagnostic, trans-drug model. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:866018. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.866018

77. Leone L, McSpadden B, DeMarco A, Enten L, Kline R, Fonzo GA. Psychedelics and evidence-based psychotherapy: A systematic review with recommendations for advancing psychedelic therapy research. Psychiatr Clin North Am. (2024) 47:367–98. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2024.02.006

78. Grabski M, McAndrew A, Lawn W, Marsh B, Raymen L, Stevens T, et al. Adjunctive ketamine with relapse prevention-based psychological therapy in the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (2022) 179:152–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21030277

79. Azhari N, Hu H, O’Malley KY, Blocker ME, Levin FR, Dakwar E. Ketamine-facilitated behavioral treatment for cannabis use disorder: A proof of concept study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2021) 47:92–7. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2020.1808982

80. Dakwar E, Levin F, Hart CL, Basaraba C, Choi J, Pavlicova M, et al. A single ketamine infusion combined with motivational enhancement therapy for alcohol use disorder: A randomized midazolam-controlled pilot trial. Am J Psychiatry. (2020) 177:125–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19070684

81. Dakwar E, Nunes EV, Hart CL, Foltin RW, Mathew SJ, Carpenter KM, et al. A single ketamine infusion combined with mindfulness-based behavioral modification to treat cocaine dependence: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. (2019) 176:923–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18101123

82. Rodriguez C, Wheaton MG, Zwerling J, Steinman SA, Sonnenfeld D, Galfalvy H, et al. Can exposure-based CBT extend the effects of intravenous ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder? an open-label trial. J Clin Psychiatry. (2016) 77:408–9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15l10138

83. O’Donnell KC, Okano L, Alpert M, Nicholas CR, Thomas C, Poulter B, et al. The conceptual framework for the therapeutic approach used in phase 3 trials of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD. Front Psychol. (2024) 15:1427531. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1427531

84. Earleywine M, Low F, Lau C, De Leo J. Integration in psychedelic-assisted treatments: Recurring themes in current providers’ definitions, challenges, and concerns. J Humanist Psychol. (2022) 62:002216782210858. doi: 10.1177/00221678221085800

85. Cabaniss DL, Arbuckle MR, Douglas C. Beyond the supportive-expressive continuum: An integrated approach to psychodynamic psychotherapy in clinical practice. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). (2010) 8:25–31. doi: 10.1176/foc.8.1.foc25

86. Lacewing M. Psychodynamic psychotherapy, insight, and therapeutic action. Clin Psychol (New York). (2014) 21:154–71. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12065

87. Fischman LG. Seeing without self: Discovering new meaning with psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Neuropsychoanalysis. (2019) 21:53–78. doi: 10.1080/15294145.2019.1689528

88. Fenn K, Byrne M. The key principles of cognitive behavioural therapy. InnovAiT. (2013) 6:579–85. doi: 10.1177/1755738012471029

89. Rothbaum BO, Schwartz AC. Exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychother. (2002) 56:59–75. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2002.56.1.59

90. Guss JR, Krause R, Sloshower J. The Yale Manual for psilocybin-Assisted Therapy of depression (using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as a therapeutic frame) (2020). Available online at: https://psyarxiv.com/u6v9y/download/?format=pdf (Accessed December 1, 2024).

91. Sloshower J, Guss J, Krause R, Wallace RM, Williams MT, Reed S, et al. Psilocybin-assisted therapy of major depressive disorder using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as a therapeutic frame. J Contextual Behav Sci. (2020) 15:12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.11.002

92. Luoma JB, Sabucedo P, Eriksson J, Gates N, Pilecki BC. Toward a contextual psychedelic-assisted therapy: Perspectives from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and contextual behavioral science. J Contextual Behav Sci. (2019) 14:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.10.003

93. Miller WR. National institute on alcohol abuse and alcoholism (U.S.). Motivational enhancement therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. Rockville, Maryland, USA: U.S. Department of health and human services, public health service, alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health administration, national institute on alcohol abuse and alcoholism (1992).

94. Veale D. Behavioural activation for depression. Adv Psychiatr Treat. (2008) 14:29–36. doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.107.004051

Keywords: psychedelics, neuroplasticity, psychoplastogens, psychedelic-assisted therapy, mental health disorders, therapeutic integration, maladaptive plasticity, cognitive flexibility

Citation: Jones JL (2025) Harnessing neuroplasticity with psychoplastogens: the essential role of psychotherapy in psychedelic treatment optimization. Front. Psychiatry 16:1565852. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1565852

Received: 23 January 2025; Accepted: 13 March 2025;

Published: 08 April 2025.

Edited by:

Amir Garakani, Yale University, United StatesReviewed by:

David Bender, Washington University in St. Louis, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Jones. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer L. Jones, am9uamVuQG11c2MuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.