- 1School of Psychology, University of Surrey, Guildford, United Kingdom

- 2Psychological Sciences Research Institute, UCLouvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium

- 3School of Medicine, University of Surrey, Guildford, United Kingdom

Introduction

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent patterns of inattention, distractibility, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, which interfere with functioning or development (1). ADHD is associated with an elevated risk of other mental health disorders and adverse outcomes such as educational underachievement, employment difficulties, interpersonal relationship challenges, and potential involvement in criminal activities (2). These far-reaching impacts make accurate and reliable ADHD assessments critical for both clinical and research purposes.

Diagnosing ADHD involves various methods, including clinical interviews, continuous performance tests, and behavioral rating scales. Best practices recommends triangulating information via a comprehensive diagnostic approach that synthesizes information from multiple sources, such as structured interviews, cognitive assessments, and behavioral rating scales (3, 4). However, in research contexts—particularly studies exploring new treatment approaches—behavioral rating scales are often the preferred outcome measure due to their cost-effectiveness, ease of administration, and accessibility (5–10).

While this pragmatic choice is often driven by resource constraints that limit the feasibility of more comprehensive assessment procedures (11), it highlights a critical responsibility for researchers: ensuring the data collected through these scales accurately represent the genuine experiences of respondents. Selecting the appropriate scale is not just a matter of practicality—it is foundational to producing reliable, meaningful research outcomes. However, behavioral rating scales are not without their challenges. Their inherent subjectivity makes them vulnerable to feigned or exaggerated symptom reporting, which can compromise the validity of findings, and hinder scientific progress.

To mitigate these risks, researchers need to remain vigilant about advancements in ADHD assessment methodologies, particularly the development of tools designed to detect invalid or exaggerated symptom presentations. These tools play a crucial role in distinguishing genuine cases from noncredible reports, ensuring that research findings are both reliable and meaningful. Without this level of scrutiny, studies risk being undermined by data that fail to accurately represent the true experiences of participants.

In this opinion paper, we aim to provide researchers with an overview of the most widely used ADHD rating scales, focusing specifically on their capacity to detect malingering—‘the intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms, motivated by external incentives’ (1). Additionally, we offer practical recommendations to guide researchers in selecting assessment tools that maximize diagnostic accuracy, enhancing the reliability and validity of their research. By addressing the challenges of malingering and invalid symptom reporting, we aim to contribute to the development of more robust ADHD evaluation strategies to allow the needed scientific progress.

Why should we care about malingering?

Diagnosing ADHD presents unique challenges, primarily due to the commonality of its symptoms—such as inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity—among the general population (12). These symptoms are often encountered to varying extents, complicating the differentiation between genuine cases and instances of feigned or malingered presentations. Moreover, the ease with which ADHD symptoms can be feigned introduces another layer of complexity to the diagnostic process (13).

In recent years, the complexity of ADHD presentations and the prevalence of potential comorbidities have further extended the diagnostic challenges beyond intentional malingering to include unintentional misdiagnosis. Both malingering and misdiagnosis highlight the critical need for accurate assessment measures in ADHD diagnosis. The vulnerability of behavioral rating scales to falsification is a particularly concerning issue, given their subjective nature (14–17).

The susceptibility of questionnaires to feigned responses is heightened by the diverse motivations individuals may have for fabricating ADHD symptoms. These include attaining social acceptance, gaining access to ADHD medications, or even enhancing academic performance (14, 18, 19). The non-specificity of the ADHD symptoms outlined in the DSM-5 further facilitates the feigning of symptoms, especially in adults, particularly among college students who may attempt to manipulate their presentation during assessments (13, 15). Alarmingly, the prevalence of feigned ADHD symptoms among students ranges from 5% to 50% (20). However, this critical issue remains largely overlooked in the literature. Specifically, only half of the recent reviews on rating scales address this problem, and even within these discussions, the topic is often treated superficially, with only brief or incidental mention (3, 21–23).

Recognizing the potential consequences of ignoring feigned ADHD symptoms in research contexts is paramount. Neglecting this issue could lead to the mismanagement of resources, erroneous conclusions, and the failure of trials, development of biomarkers, or replications, as findings may be based upon inaccurate diagnoses. Therefore, it is essential for researchers to detect feigned ADHD symptoms when utilizing behavioral rating scales to enhancing the integrity and reliability of their findings.

Addressing feigned ADHD symptoms in assessments

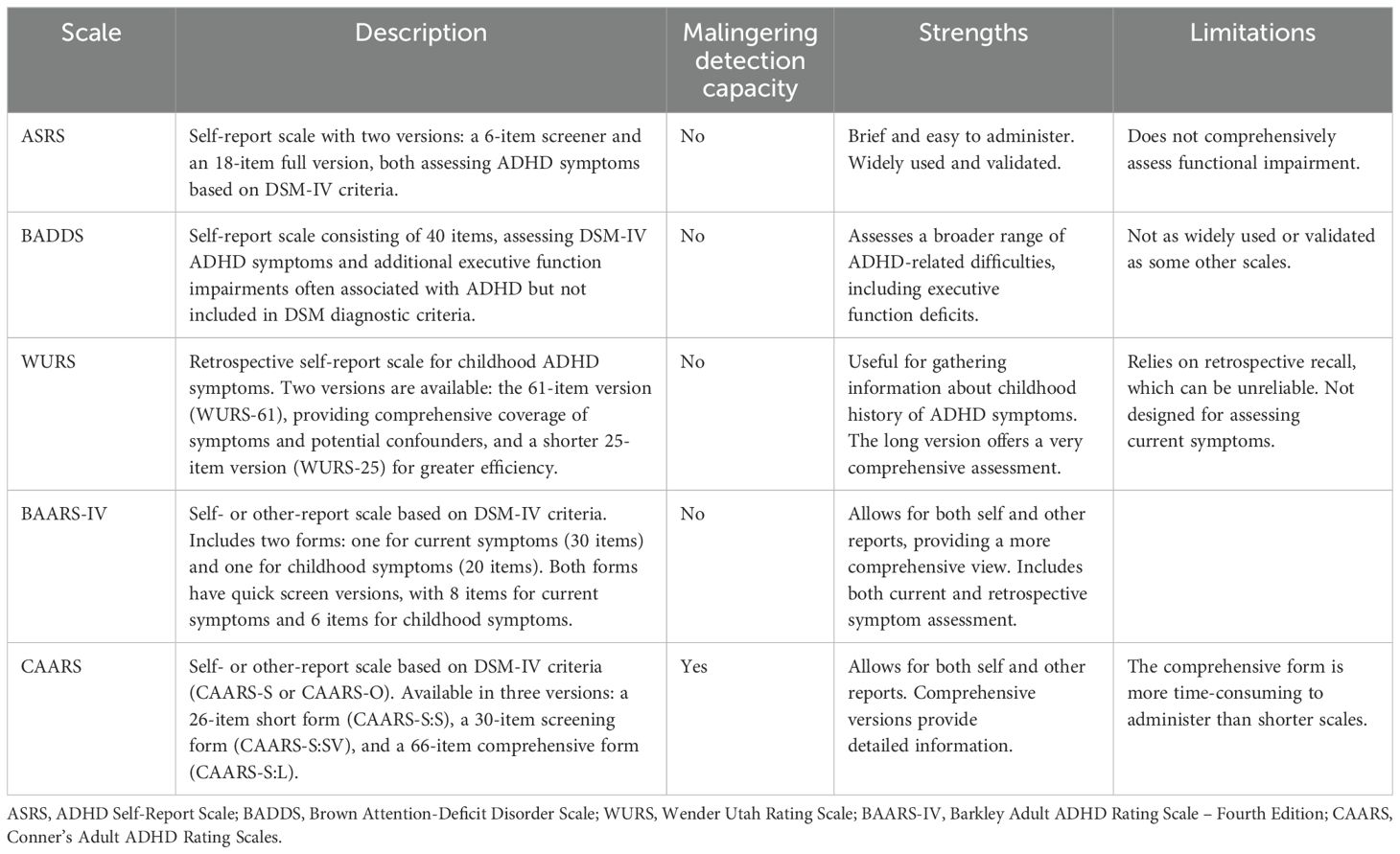

Among the most commonly used behavioral rating scales in adult ADHD assessment are the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS; 11), the Brown Attention-Deficit Disorder Scale (BADDS; 24), the Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS; 25), the Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale (BAARS-IV; 26) and the Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS; 27). Publicly available scales like the ASRS assess ADHD symptoms outlined in the DSM-4 (28) while the WURS retrospectively evaluates childhood ADHD symptoms. Commercial tools such as the BAARS and the CAARS offer more comprehensive assessments. Notably, the CAARS and BAARS-IV provide self- and observer-reported versions, enhancing reliability. These scales are valued for their ease of administration and ability to measure ADHD symptom severity across various domains of functioning (see Table 1). However, their reliance on self-reported data, without accounting for feigned symptoms, increases the likelihood that the score in these questionnaires could include intentional exaggeration or falsification of symptoms.

Fortunately, recent years have seen a surge in the development of tools aimed at identifying invalid ADHD symptom reports (29–31). These tools, commonly referred to as symptom validity tests (SVTs), can be incorporated into existing scales or used as standalone measures. In contrast with the scales previously mentioned, the CAARS stands out as the sole scale currently featuring two embedded validity indexes1, the CAARS Infrequency Index (CII; 32) and the Exaggeration Index (EI; 33). The CII consists of items that are rarely endorsed by individuals with ADHD or by healthy controls, making it highly effective at identifying noncredible symptom reporting when responses exceed a specific threshold. The EI, on the other hand, combines items from the CAARS with additional items adapted from the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES; 34), all of which are infrequently endorsed by individuals with genuine ADHD. A third validity index, the ADHD credibility index (ACI; 35) is still under development. The ACI uses ADHD-specific items designed to capture various patterns of noncredible symptom reporting. Together, these indexes help determine whether an individual’s symptom reports align with expected behavioral patterns, providing a robust method for detecting malingering.

In addition to these embedded SVTs, there is also an increasing demand for standalone SVTs specifically designed to distinguish between genuine and feigned ADHD symptoms. Notable examples include the ADHD Symptom Infrequency Scale (ASIS; 36), which consists of two subscales: the ADHD subscale (aligned with DSM-5 diagnostic criteria) and the Infrequency subscale (designed to identify symptoms more likely to be endorsed by individuals feigning ADHD). Another scale is the Multidimensional ADHD Rating Scale (MARS; 37), which includes three categories of items: symptom items, impairment items, and symptom-validity items. The MARS also incorporates “catch” items to assess the test-taker’s effort and attention during the assessment. Although these scales show promise, further validation is needed to confirm their reliability and accuracy.

One significant advantage of using embedded SVTs over standalone measures is that they make the detection strategy less transparent to individuals who might attempt to feign symptoms. The subtlety of embedded SVTs minimizes the chances of test-takers altering their responses when they are aware of the detection process (32).

Discussion

The critical issue of feigning in ADHD assessments has long been overlooked, despite its significant impact on both clinical practice and research. Accurate assessments are essential for diagnosis and treatment planning, and it is crucial that the detection of feigned responses becomes a standard part of all behavioral rating scale protocols. As the field moves toward developing novel methods for identifying feigned responses, we expect substantial improvements in accuracy and precision. However, until these advancements become widely available, it is vital to continue using well-established tools that have proven their effectiveness over time. While the scope of providing recommendations on using SVTs in clinical settings is outside the scope of the current paper, we refer the reader to Marshall et al. (3), whose review also underscores their relevance to diagnostic procedures.

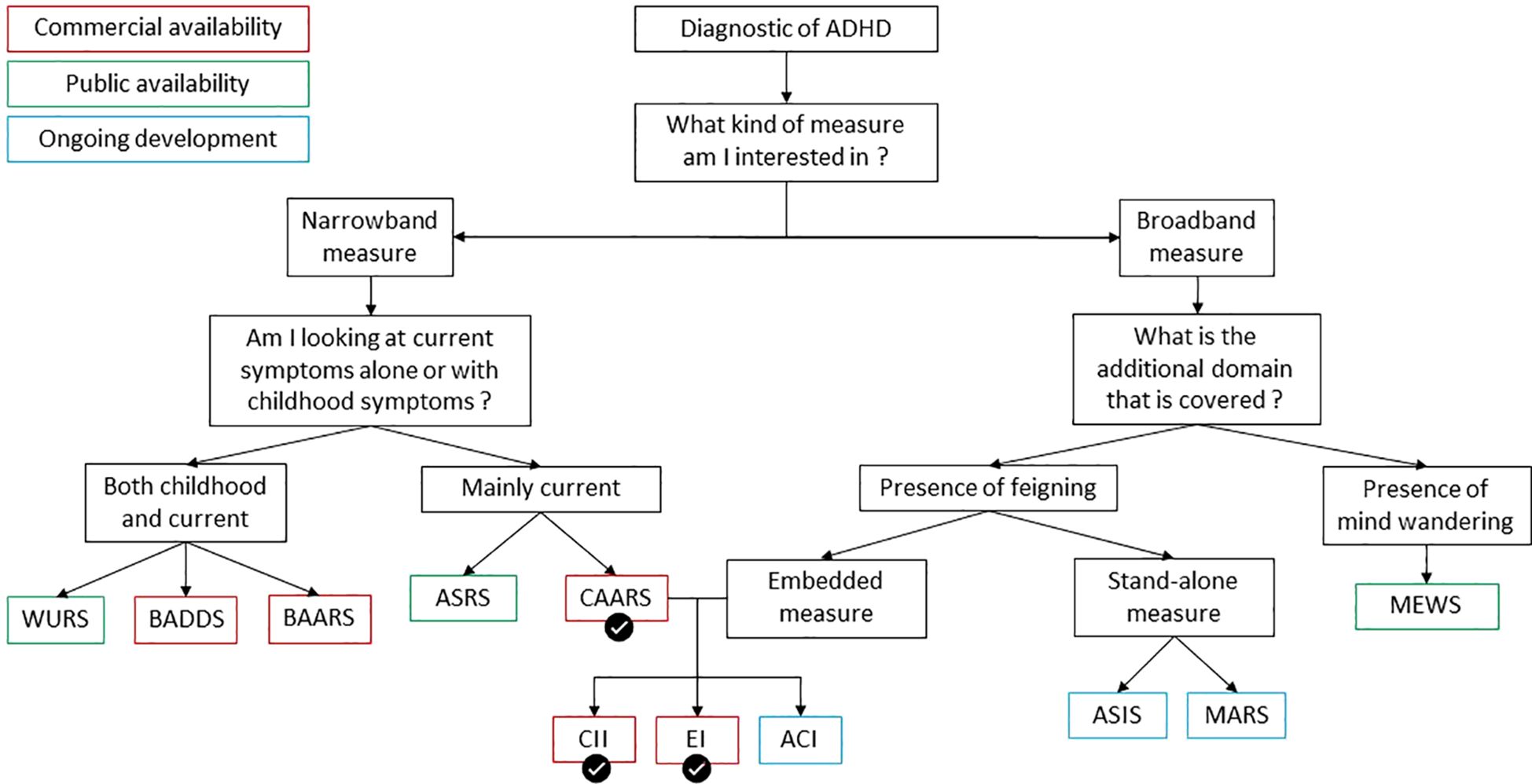

Based on current evidence, we strongly recommend using the long version of the CAARS self-report form (CAARS-S:L), due to its proven accuracy and widespread acceptance in the field (3, 23). The CAARS has consistently been identified as one of the most reliable tools for assessing ADHD symptoms. One of its key strengths is its ability to detect feigned responses, with its embedded validity indexes—the CII and EI—which help to identify invalid symptom reporting. We recommend using both of them as employing multiple SVTs effectively lowers the incidence of false positives in malingering evaluations (17). Additionally, unlike other scales such as the WURS or ASRS, the CAARS covers a broader range of ADHD symptoms, including those not specifically outlined in the DSM-5, enhancing its diagnostic utility. Moreover, the CAARS is particularly advantageous in monitoring treatment efficacy, as it tracks both the presence and severity of ADHD symptoms over time, unlike the WURS, which only addresses historical symptoms. Future research should clarify how these tools, including the ADHD Credibility Index (ACI), be further verified and customized for usage in varied demographics and circumstances. To conclude, we have outlined key assessment tools to address the challenge of feigned or malingering ADHD symptoms, considering their scope, target populations, usage terms, and effectiveness. Figure 1 summarizes our recommendations. Although the CAARS is a commercial tool and not freely available, its comprehensive coverage of ADHD symptoms, ability to detect feigned responses through embedded validity indexes, and its utility in monitoring both symptom severity and treatment efficacy make it an invaluable resource for accurate and reliable ADHD assessment in research settings.

Figure 1. Flowchart of ADHD assessment tools based on availability, symptoms measured and detection of feigning. Measures are color-coded for their availability status—green for publicly available, red for commercially available, and blue for those under development. Recommended measures are indicated with a checkmark. The CII and EI are marked in red, as their use requires the CAARS-S. Narrowband measures target specific ADHD symptoms, while broadband measures assess a wider range of behaviors. Key abbreviations include: WURS (Wender Utah Rating Scale), BADDS (Brown Attention-Deficit Disorder Scale), ASRS (ADHD Self-Report Scale), CAARS (Conner’s Adult ADHD Rating Scales), CII (CAARS Infrequency Index), ACI (ADHD Credibility Index), ASIS (ADHD Symptom Infrequency Scale), BAARS-IV (Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale – Fourth Edition), EI (Exaggeration Index), MEWS (Mind Excessively Wandering Scale), and MARS (Multidimensional ADHD Rating Scale).

Author contributions

MG: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. RM: Writing – review & editing. RC: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The work was supported by the MRC Impact Acceleration Grant (RN0521D) awarded to RC.

Conflict of interest

RM has delivered presentations for several pharmaceutical companies specializing in ADHD, whereby the funds generated were specifically allocated to the neurodevelopmental teams, with no direct financial compensation received by the author.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ These two indexes were developed to be used with the CAARS-S:L. The CAARS-S:S and CAARS-S:L also have an Inconsistency Index but it only measures the consistency at which an individual is reporting similar symptoms.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

2. Sayal K, Prasad V, Daley D, Ford T, Coghill D. ADHD in children and young people : Prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. Lancet Psychiatry. (2018) 5:175–86. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30167-0

3. Marshall P, Hoelzle J, Nikolas M. Diagnosing Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in young adults : A qualitative review of the utility of assessment measures and recommendations for improving the diagnostic process. Clin Neuropsychologist. (2021) 35:165–98. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2019.1696409

4. Sibley MH. Empirically-informed guidelines for first-time adult ADHD diagnosis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. (2021) 43:340–51. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2021.1923665

5. Alyagon U, Shahar H, Hadar A, Barnea-Ygael N, Lazarovits A, Shalev H, et al. Alleviation of ADHD symptoms by non-invasive right prefrontal stimulation is correlated with EEG activity. NeuroImage : Clin. (2020) 26:102206. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102206

6. Berger I, Dakwar-Kawar O, Grossman E, Nahum M, Cohen Kadosh R. Scaffolding the attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder brain using transcranial direct current and random noise stimulation : A randomized controlled trial. Clin Neurophysiol. (2021) 132(3):699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2021.01.005

7. Dakwar-Kawar O, Mairon N, Hochman S, Berger I, Cohen Kadosh R, Nahum M. Transcranial random noise stimulation combined with cognitive training for treating ADHD : A randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial. Trans Psychiatry. (2023) 13:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02547-7

8. McGough JJ, Sturm A, Cowen J, Tung K, Salgari GC, Leuchter AF, et al. Double-blind, sham-controlled, pilot study of trigeminal nerve stimulation for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2019) 58:403–11.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.11.013

9. Paz Y, Friedwald K, Levkovitz Y, Zangen A, Alyagon U, Nitzan U, et al. Randomised sham-controlled study of high-frequency bilateral deep transcranial magnetic stimulation (dTMS) to treat adult attention hyperactive disorder (ADHD) : Negative results. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2018) 19:561–6. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2017.1282170

10. Weaver L, Rostain AL, Mace W, Akhtar U, Moss E, O’Reardon JP. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adolescents and young adults : A pilot study. J ECT. (2012) 28:98. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e31824532c8

11. Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E, et al. The World Health Organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS) : A short screening scale for use in the general population. psychol Med. (2005) 35:245–56. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704002892

12. DuPaul GJ, Schaughency EA, Weyandt LL, Tripp G, Kiesner J, Ota K, et al. Self-report of ADHD symptoms in university students : Cross-gender and cross-national prevalence. J Learn Disabil. (2001) 34:370–9. doi: 10.1177/002221940103400412

13. Quinn CA. Detection of Malingering in assessment of adult ADHD. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. (2003) 18:379–95. doi: 10.1093/arclin/18.4.379

14. Harrison AG, Edwards MJ, Parker KCH. Identifying students faking ADHD : Preliminary findings and strategies for detection. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. (2007) 22:577–88. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.03.008

15. Jachimowicz G, Geiselman RE. Comparison of ease of falsification of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnosis using standard behavioral rating scales. Cognitive Science Online. (2004) 2:6–20.

16. Lee Booksh R, Pella RD, Singh AN, Drew Gouvier W. Ability of college students to simulate ADHD on objective measures of attention. J Attention Disord. (2010) 13:325–38. doi: 10.1177/1087054708329927

17. Sollman MJ, Ranseen JD, Berry DTR. Detection of feigned ADHD in college students. psychol Assess. (2010) 22:325–35. doi: 10.1037/a0018857

18. Hinshaw SP, Scheffler RM. The ADHD explosion : Myths, medication, money, and today’s push for performance. New York: Oxford University Press (2014). p. xxxii, 254.

19. Suhr J, Wei C. Symptoms as an excuse : attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom reporting as an excuse for cognitive test performance in the context of evaluative threat. J Soc Clin Psychol. (2013) 32:753–69. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2013.32.7.753

20. Sadek J. Malingering and stimulant medications abuse, misuse and diversion. Brain Sci. (2022) 12:Article 8. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12081004

21. Caroline S, S. S, Sudhir PM, Mehta UM, Kandasamy A, Thennarasu K, et al. Assessing adult ADHD : an updated review of rating scales for adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). J Attention Disord. (2024) 28(7):1045–62 10870547241226654. doi: 10.1177/10870547241226654

22. Harrison AG, Edwards MJ. The ability of self-report methods to accurately diagnose attention deficit hyperactivity disorder : A systematic review. J Attention Disord. (2023) 27(12):1343–59. doi: 10.1177/10870547231177470

23. Taylor A, Deb S, Unwin G. Scales for the identification of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) : A systematic review. Res Dev Disabil. (2011) 32:924–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.036

24. Brown TE. Brown attention-deficit disorder scales. San Antonio: TX: Psychological Corporation (1996).

25. Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah Rating Scale : An aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (1993) 150:885–90. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.885

26. Barkley RA. Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV (BAARS-IV). New York: The Guilford Press (2011). p. x, 150.

27. Conners CK, Erhardt D, Sparrow MA. Conner’s Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS). New York: Multihealth Systems, Inc (1999).

28. Adler LA, Spencer T, Faraone SV, Kessler RC, Howes MJ, Biederman J, et al. Validity of pilot Adult ADHD Self- Report Scale (ASRS) to Rate Adult ADHD symptoms. Ann Clin Psychiatry. (2006) 18:145–8. doi: 10.1080/10401230600801077

29. Sagar S, Miller CJ, Erdodi LA. Detecting feigned attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) : current methods and future directions. psychol Injury Law. (2017) 10:105–13. doi: 10.1007/s12207-017-9286-6

30. Tucha L, Fuermaier ABM, Koerts J, Groen Y, Thome J. Detection of feigned attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Neural Transm. (2015) 122:123–34. doi: 10.1007/s00702-014-1274-3

31. Wallace ER, Garcia-Willingham NE, Walls BD, Bosch CM, Balthrop KC, Berry DTR. A meta-analysis of Malingering detection measures for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. psychol Assess. (2019) 31:265–70. doi: 10.1037/pas0000659

32. Suhr JA, Buelow M, Riddle T. Development of an infrequency index for the CAARS. J Psychoeducational Assess. (2011) 29:160–70. doi: 10.1177/0734282910380190

33. Harrison AG, Armstrong IT. Development of a symptom validity index to assist in identifying ADHD symptom exaggeration or feigning. Clin Neuropsychologist. (2016) 30:265–83. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2016.1154188

34. Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nervous Ment Dis. (1986) 174:727. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198612000-00004

35. Becke M, Tucha L, Weisbrod M, Aschenbrenner S, Tucha O, Fuermaier ABM. Non-credible symptom report in the clinical evaluation of adult ADHD : Development and initial validation of a new validity index embedded in the Conners’ adult ADHD rating scales. J Neural Transm. (2021) 128:1045–63. doi: 10.1007/s00702-021-02318-y

36. Courrégé SC, Skeel RL, Feder AH, Boress KS. The ADHD Symptom Infrequency Scale (ASIS) : A novel measure designed to detect adult ADHD simulators. psychol Assess. (2019) 31:851–60. doi: 10.1037/pas0000706

Keywords: ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), malingering and feigning detection, research, diagnostic, behavioral rating scale

Citation: Grandjean M, Hochman S, Mukherjee R and Cohen Kadosh R (2025) Malingering in ADHD behavioral rating scales: recommendations for research contexts. Front. Psychiatry 16:1532807. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1532807

Received: 22 November 2024; Accepted: 08 January 2025;

Published: 24 January 2025.

Edited by:

Vikram Kulkarni, SVKM’s Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies, IndiaReviewed by:

Bhushankumar Nemade, Mumbai University, IndiaCopyright © 2025 Grandjean, Hochman, Mukherjee and Cohen Kadosh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marius Grandjean, bWFyaXVzLmdyYW5kamVhbkB1Y2xvdXZhaW4uYmU=

Marius Grandjean

Marius Grandjean Shachar Hochman

Shachar Hochman Raja Mukherjee

Raja Mukherjee Roi Cohen Kadosh

Roi Cohen Kadosh