- 1Health and Wellness Research Group, Department of Family Medicine, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

- 2Spiritual Health Research Center, Lifestyle Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Objectives: The study examined the prevalence, incidence, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) associated with self-harm across countries in the Middle East and North Africa, while also analyzing suicide mortality. It aims to explore the variations in self-harm and suicide mortality by sex and assess trends in these phenomena from 1990 to 2021.

Methods: Global Burden of Disease 2021 data sources were used in this study. Estimates for all-age counts and age-standardized prevalence rates (per 100,000) were determined for prevalence, incidence, Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs), and suicide mortality. These disease burden indicators were analyzed across the period from 1990 to 2021, and the results were further stratified by sex and location. Additionally, the percentage change observed between 1990 and 2021 was documented. A 95% uncertainty interval was used for each estimate reported.

Results: The age-standardized prevalence of self-harm in the MENA region was 111.82 per 100,000 in 1990, decreasing to 105.84 by 2021. The global age-standardized prevalence rate of self-harm is 182.24 per 100,000 in 2021. Throughout this period, the self-harm rates in the MENA region remained lower than the global average. In 2021, approximately 621,509 individuals in the region were reported to engage in self-harm. In the same year, the age-standardized suicide mortality rate in MENA stood at 3.43 per 100,000, with an estimated total of over 21,000 suicide deaths. The age-standardized DALYs rate of self-harm in MENA was 246.03 per 100,000 in 1990 and decrease to 177.44 per 100,000 in 2021. The gender disparity in 2021 revealed higher self-harm rates among females than males, at 112.57 vs. 99.67 per 100,000, respectively. In contrast, suicide mortality rates were higher in males than females, recorded at 4.83 vs. 1.92 per 100,000.

Conclusions: Although the rates of suicide mortality and self-harm have declined, the overall number of cases has risen alongside population growth. This highlights the necessity for more comprehensive efforts in mental health care, including screening, prevention, treatment, and the accurate identification of risk factors.

Introduction

Self-harm and suicide are major health and societal issues in the world, and have a great burden on health, especially in low- and middle-income countries (1). Self-harm is defined as “when somebody injures or harms themselves to cope with or express extreme emotional distress and internal turmoil. They do not generally intend to kill themselves, but the results can be fatal” (2). Suicide is defined as “the act of intentionally carrying out an action to kill oneself” (2).

Based on the estimates made during recent decades, age-standardized incidence rates of self-harm are 62.48 per 100,000 and the rate of DALY rates of self-harm were 424.7 per 100,000 (3). The burden of self-harm varies with age and sex (3). The ratio of self-harm in young women to that in men is reported to be 2.6 to 1 (4). In the most recent report published by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), the prevalence of self-harm was 8.4 million in females and 7.07 million in males (5). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 700,000 people die by suicide every year, of which 77% live in low- and middle-income countries (6). Among the causes of death, 1.3% of deaths are caused by suicide; according to a report published in 2019, suicide was the 17th most common cause of death worldwide (7), and suicide is more prevalent in men than in women (8, 9). One of the super regions of the world that has faced many challenges in recent decades and has affected mental health is MENA (10).

North Africa and the Middle East, including 21 countries, have a range of sociodemographic similarities. However, there are also differences in other dimensions, and these differences exist in health systems (11). Over the past few decades, this super region has witnessed an improvement in morbidity and mortality due to improvements in health care, health education, and socioeconomic development (11). Several factors can affect mental health, especially self-harm and suicide in MENA. First, as mentioned, the highest rates of self-harm and suicide occur in low- and middle-income countries (6). In this regard, a classification of 21 countries in MENA shows that almost two-thirds of these countries are low- and middle-income countries (11). Second, conflict, war, and its consequences, i.e., displacement and migration, are important factors in mental health (12–15). In this respect, MENA has been the center of conflict and war during the last few decades (16). These wars and conflicts have led to injuries, trauma, human crises, destruction of health infrastructure, displacement, and increase in morbidity and mortality (17). Third, demographic changes in MENA are among the most important health issues affecting all aspects of health. In the past, we have seen a trend of population growth in this super region, which led to an increase in the population and, as a result, the demand for healthcare and services; however, in recent years, a population change has been observed with a decrease in the fertility rate (18, 19).

Self-harm and suicide have negative effects on society’s health and impose a significant burden on health and the economic system. The region has faced decades of conflict, war, and displacement, all of which have significantly affected its mental health. Simultaneously, the shared history and cultural similarities among countries in the area provide a valuable context for understanding these mental health challenges. Examining suicidal behaviors is especially crucial, as the region encounters distinct sociopolitical pressures such as ongoing conflict, migration issues, and scarce mental health resources. These factors play a critical role in shaping both the prevalence of self-harm and suicide as well as the patterns of how they are reported. Based on this, this study aimed to investigate the prevalence, incidence, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) caused by self-harm in MENA countries, as well as suicide mortality. Sex differences in self-harm and suicide mortality, as well as investigating the trends of self-harm and suicide from 1990 to 2021, are among the goals of this study.

Methods

Data source

This study was based on the Global Burden of Disease 2021 (20). The analysis of disease burden indicators included prevalence, incidence, Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs), Years Lived with Disability (YLDs), Years of Life Lost (YLLs), and mortality data spanning 371 diseases and injuries. It also incorporates estimates of healthy life expectancy (HALE). These metrics are categorized by sex, age groups, and 204 countries and territories, with subnational data provided for 21 of these countries (20). The GBD 2021 analysis utilized 100,983 data sources, including 19,189 newly added specifically for DALYs. Furthermore, 12 new causes were introduced, accompanied by several major methodological improvements (20). The estimates covered the Middle East and North Africa region, with additional details about GBD 2021 available from other sources (20).

Case definitions

Self-harm in the GBD 2021 is “deliberate bodily damage inflicted on oneself, resulting in death or injury. ICD-9: E950-E959; ICD-10: X60-X64.9, X66-X84.9, Y87.0” (20, 21). Contains two subclasses Self-harm by firearm “Death or disability inflicted by the intentional use of a firearm on oneself. ICD-9: E955-E955.9; ICD-10: X72-X74.9” (20, 21). Self-harm by other specified means is defined as “death or occurrence of deliberate bodily damage inflicted on oneself resulting in death using self-poisoning, medication overdose, transport, falling from height, hanging or strangulation, or other mechanisms not including firearms. ICD9: E950-E954, E956-E959; ICD10: X60-X64.9, X66-X67.9, X69-X71.9, X75-X75.9, X77-X84.9, Y87.0” (20, 21). This study incorporated suicide data from various sources, including vital registration (VR) records, survey results, verbal autopsy (VA) data, and surveillance systems, with further details available in other referenced materials (22).

Estimation framework

Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) were calculated “with a microsimulation process that used estimated age-sex-location-year-specific prevalent counts of non-fatal disease sequelae (consequences of a disease or injury) for each cause and disability weights for each sequela as the input estimates at varying levels of severity by an appropriate disability weight” (20). YLLs calculated as “the product of estimated age-sex location-year-specific deaths and the standard life expectancy at the age death occurred for a given cause” (20). DALYs were calculated as the sum of YLDs and YLLs (20).

Statistical analysis

Estimates for all-age counts and age-standardized rates (per 100,000) were computed for prevalence, incidence, Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs), and suicide mortality. The age-standardized rate is “a weighted average of the age-specific rates, where the weights are the proportions of a standard population in the corresponding age groups” (23). Disease burden indicators were analyzed for the period spanning 1990 to 2021, broken down by sex and location. In addition, the percentage change over the years was recorded. A 95% uncertainty interval was used for each estimate. More details about the data, data processing, and modeling are provided elsewhere and are related to GBD 2021 (20).

GBD 2021 complies with the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER) (24).

Results

Prevalence of self-harm in MENA from 1990 to 2021

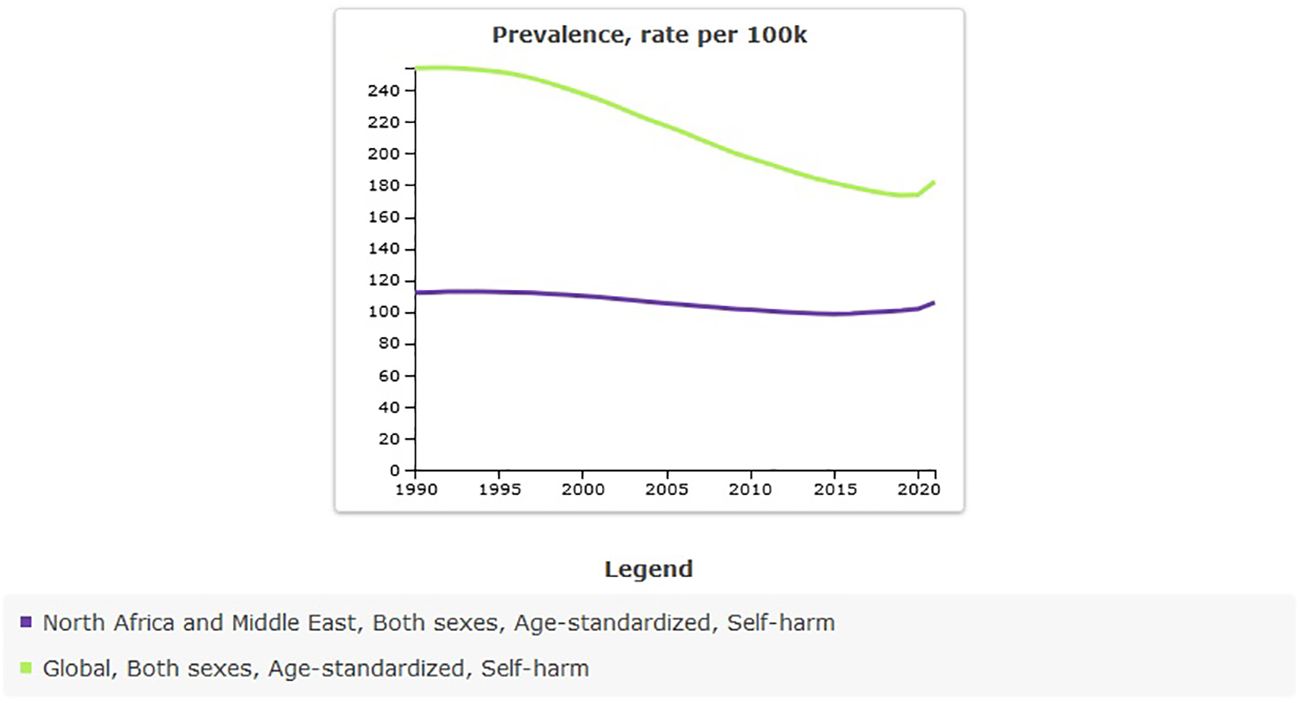

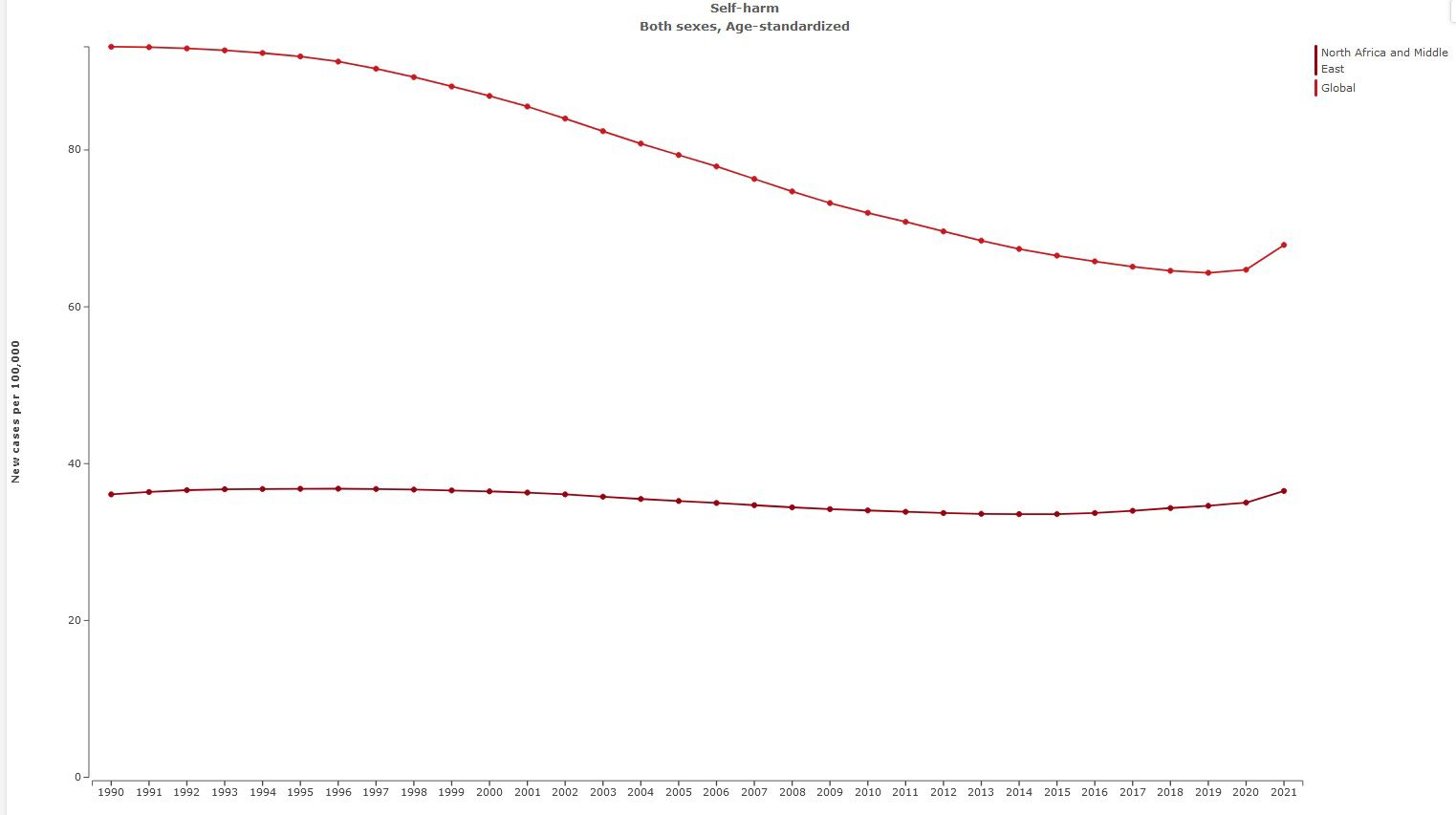

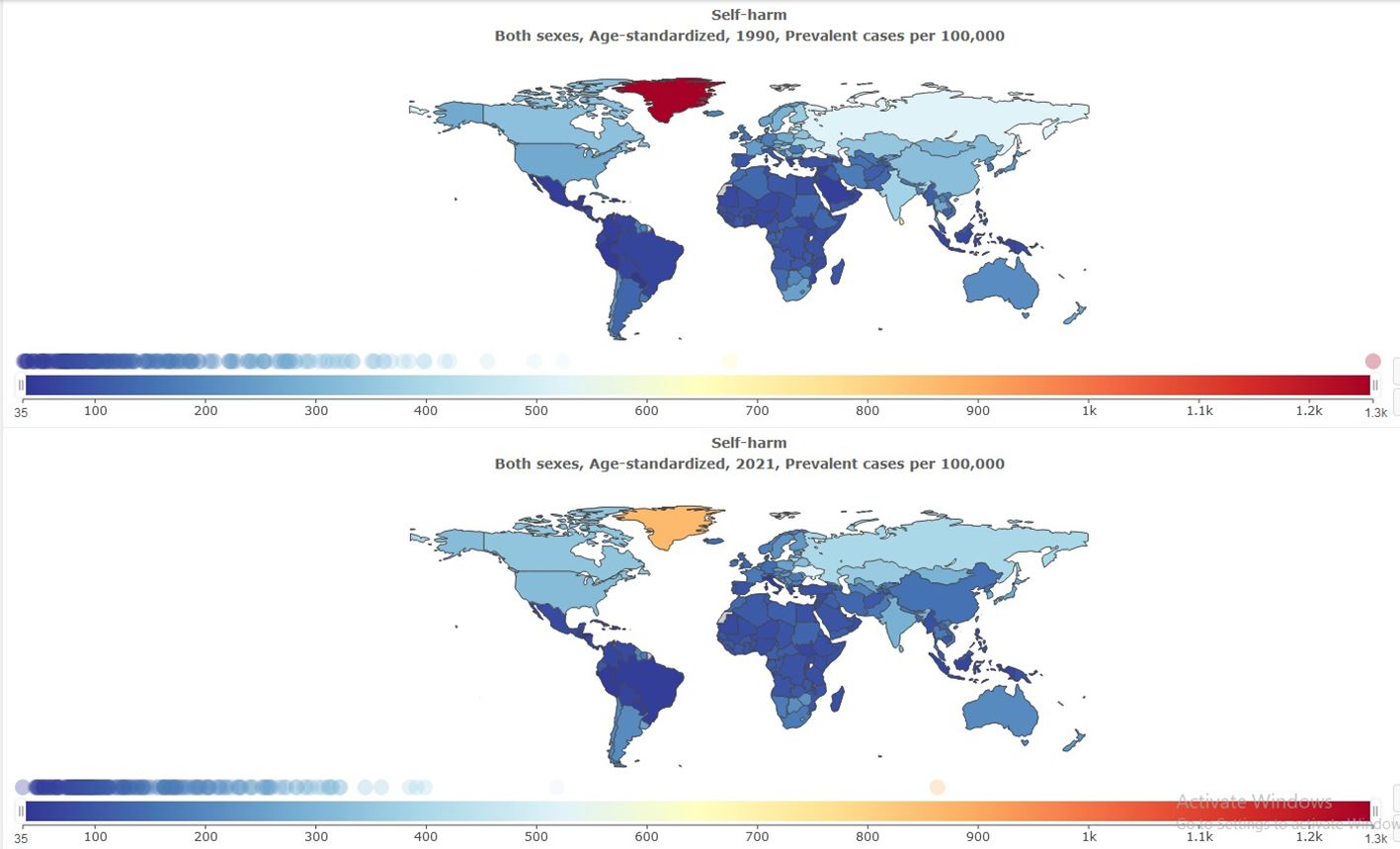

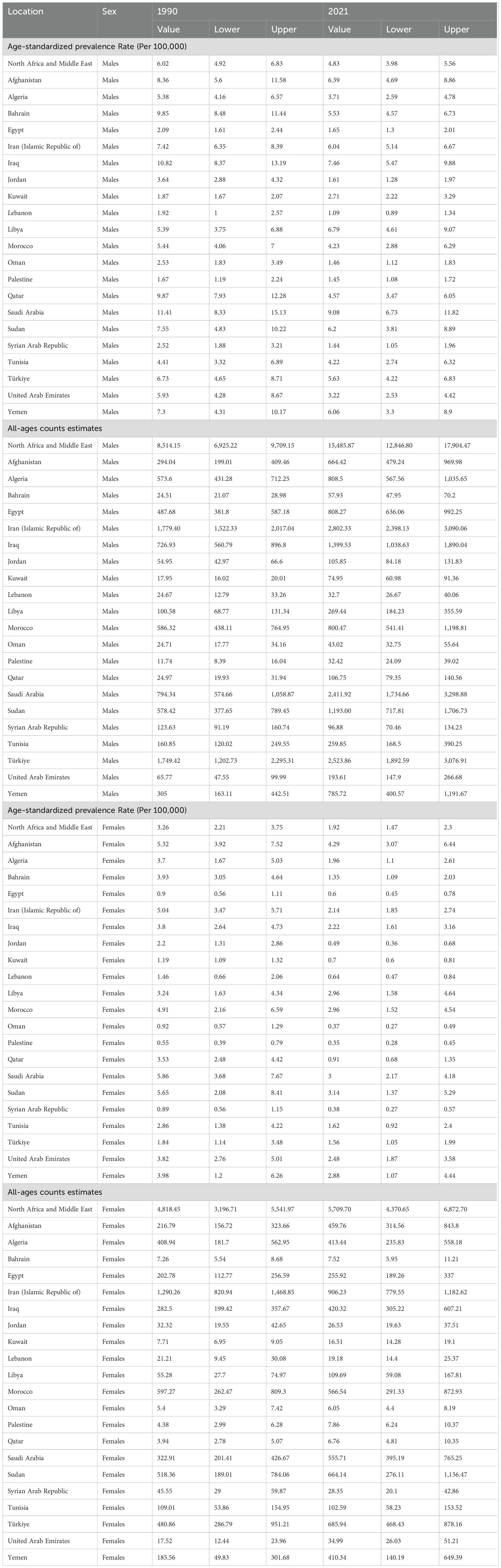

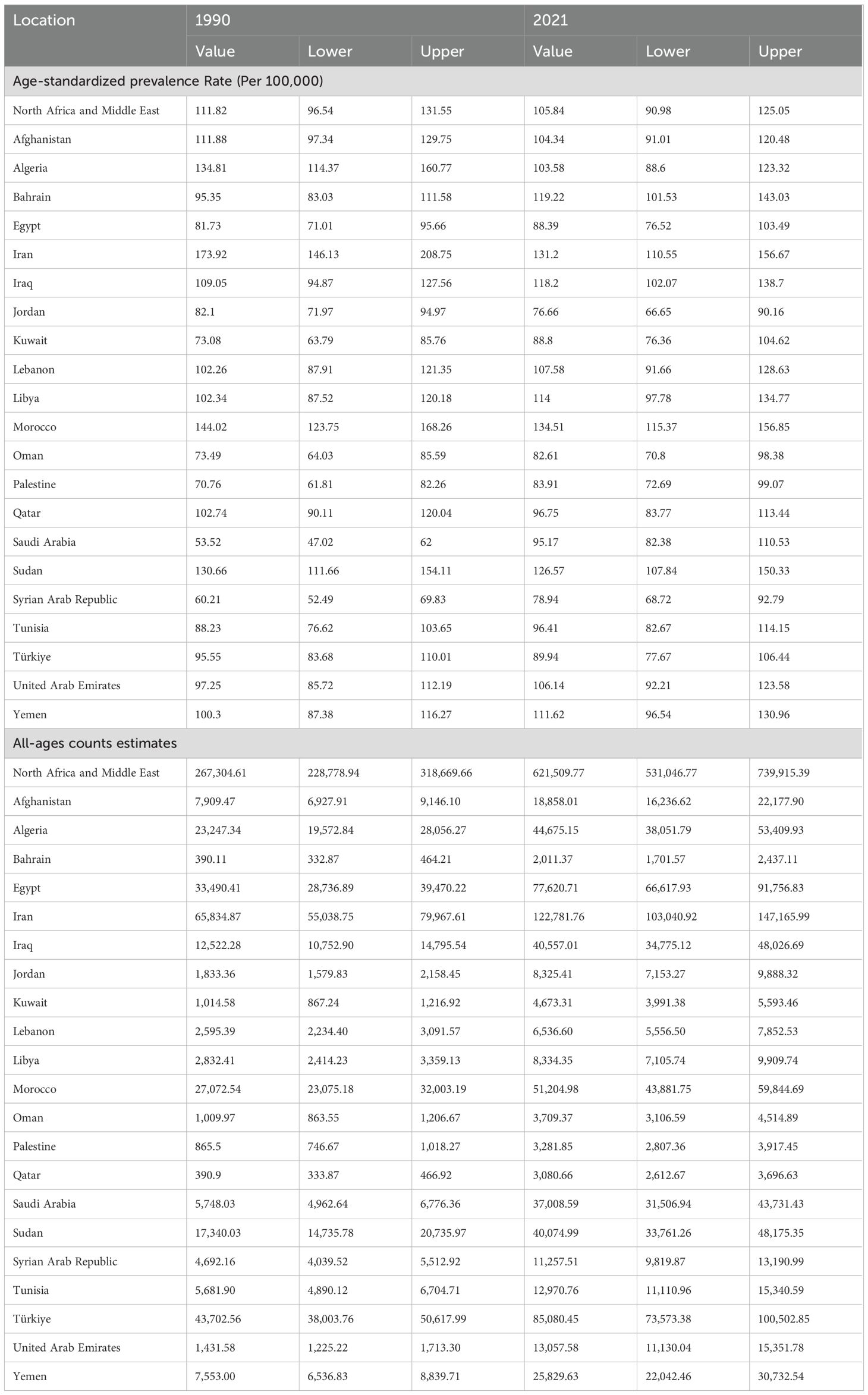

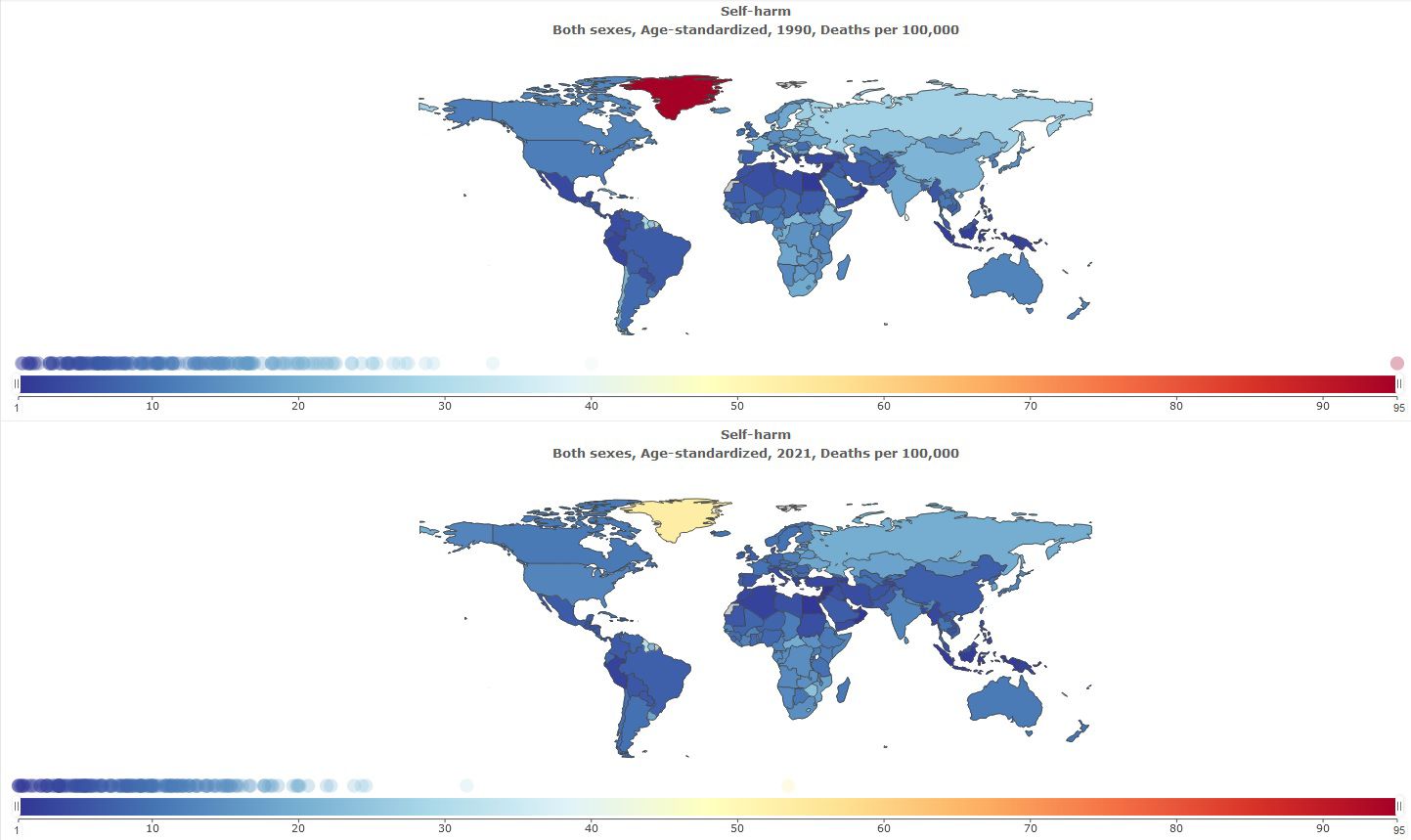

The age-standardized prevalence rate of self-harm in MENA was 111.82 [95% UI 96.54 to 131.55] per 100,000 in 1990, and this rate decreased to 105.84 [95% UI 90.98 to 125.05] per 100,000 in 2021 [Table 1]. The percentage change from 1990 to 2021 showed a negative trend of -5% [95% UI −8 to −4]. Global age-standardized prevalence rate of self-harm was 182.24 per 100,000 in 2021. Compared with the global population, self-harm was less prevalent in MENA from 1990 to 2021 (Figure 1). The prevalence of self-harm in MENA countries is lower than that in most other countries (Figure 2).

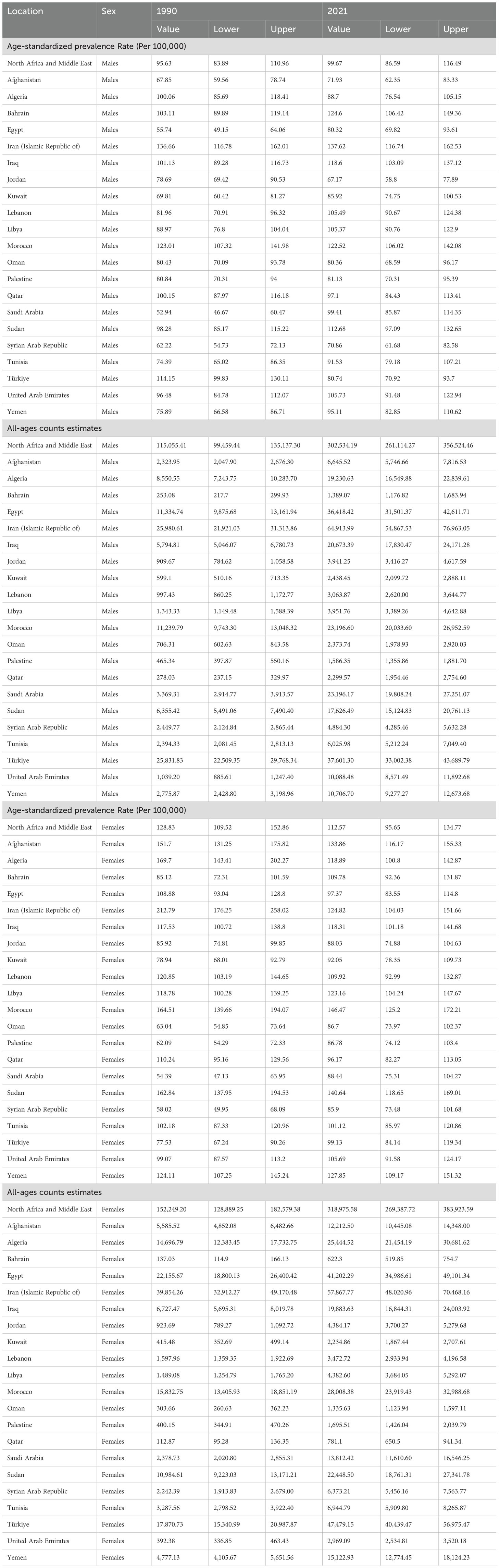

Table 1. All-ages counts and age-standardized prevalence rate (per 100,000) of self-harm in MENA, 1990–2021.

The all-age count estimates that the prevalence of self-harm in MENA was 267,304 [95% UI 228,778 to 318,669] in 1990, and this rate increased to 621,509 [95% UI 531,046 to 739,915] in 2021. The percentage change from 1990 to 2021 showed a sharp increase of 133% [95% UI 124 to 140]. This shows that, despite the decrease in the age-standardized prevalence rate, the number of self-harms has increased. An increase in population leads to an increase in self-harm counts.

Incidence of self-harm in MENA from 1990 to2021

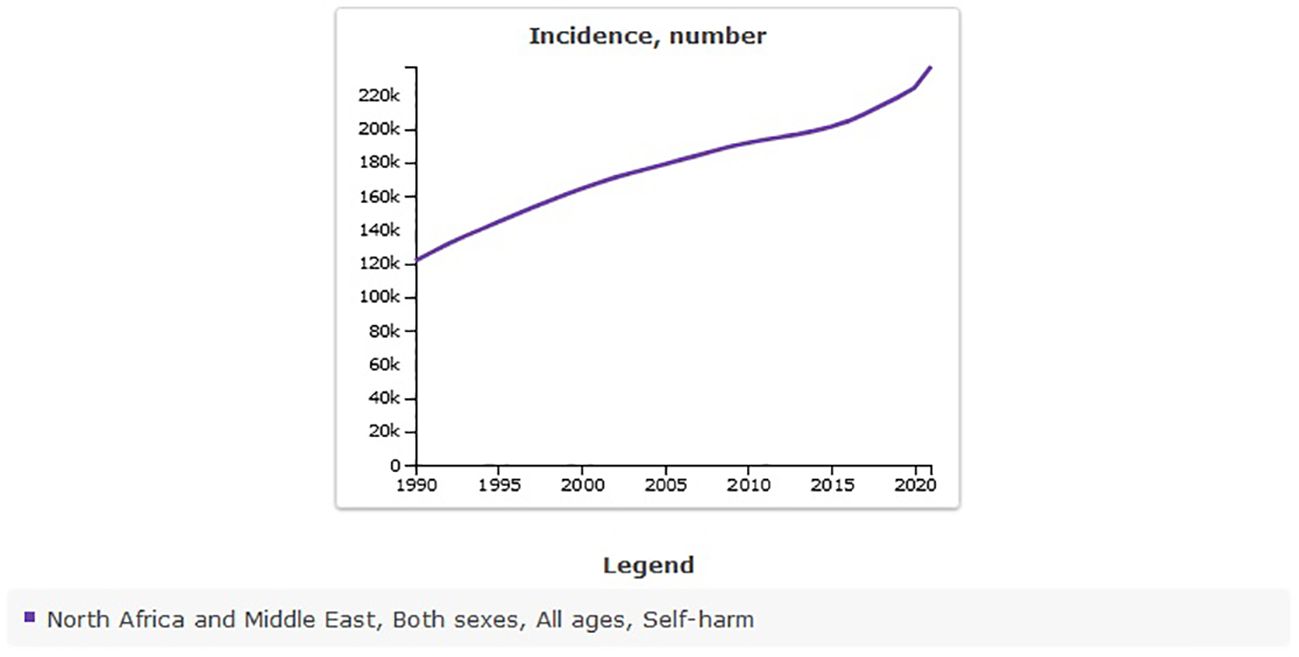

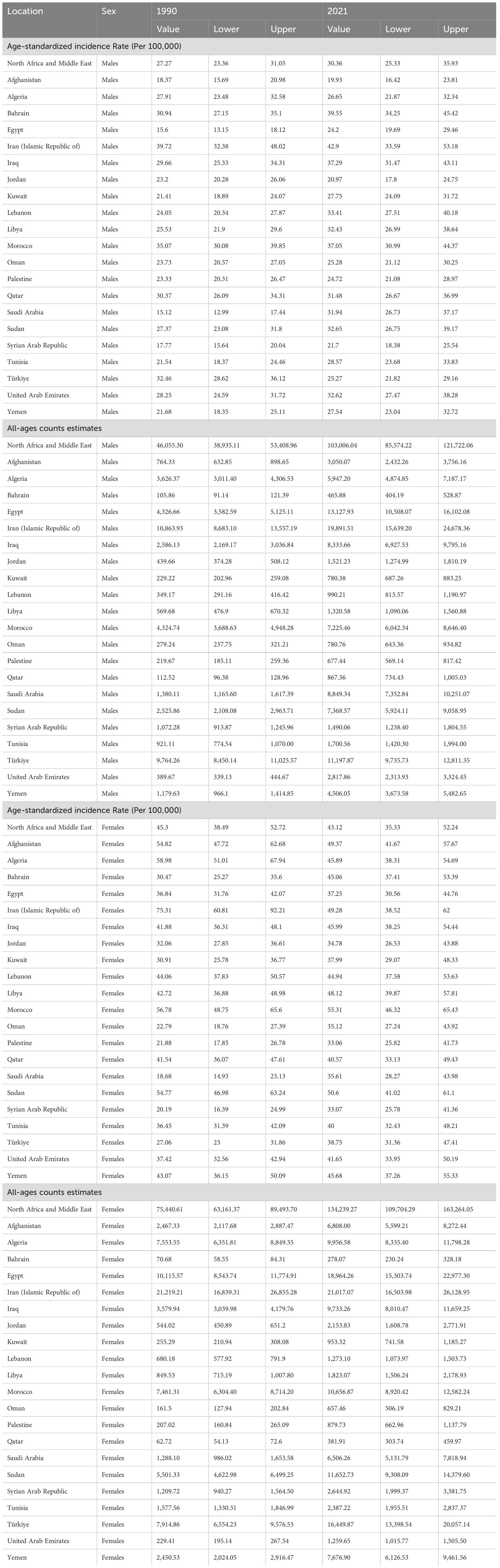

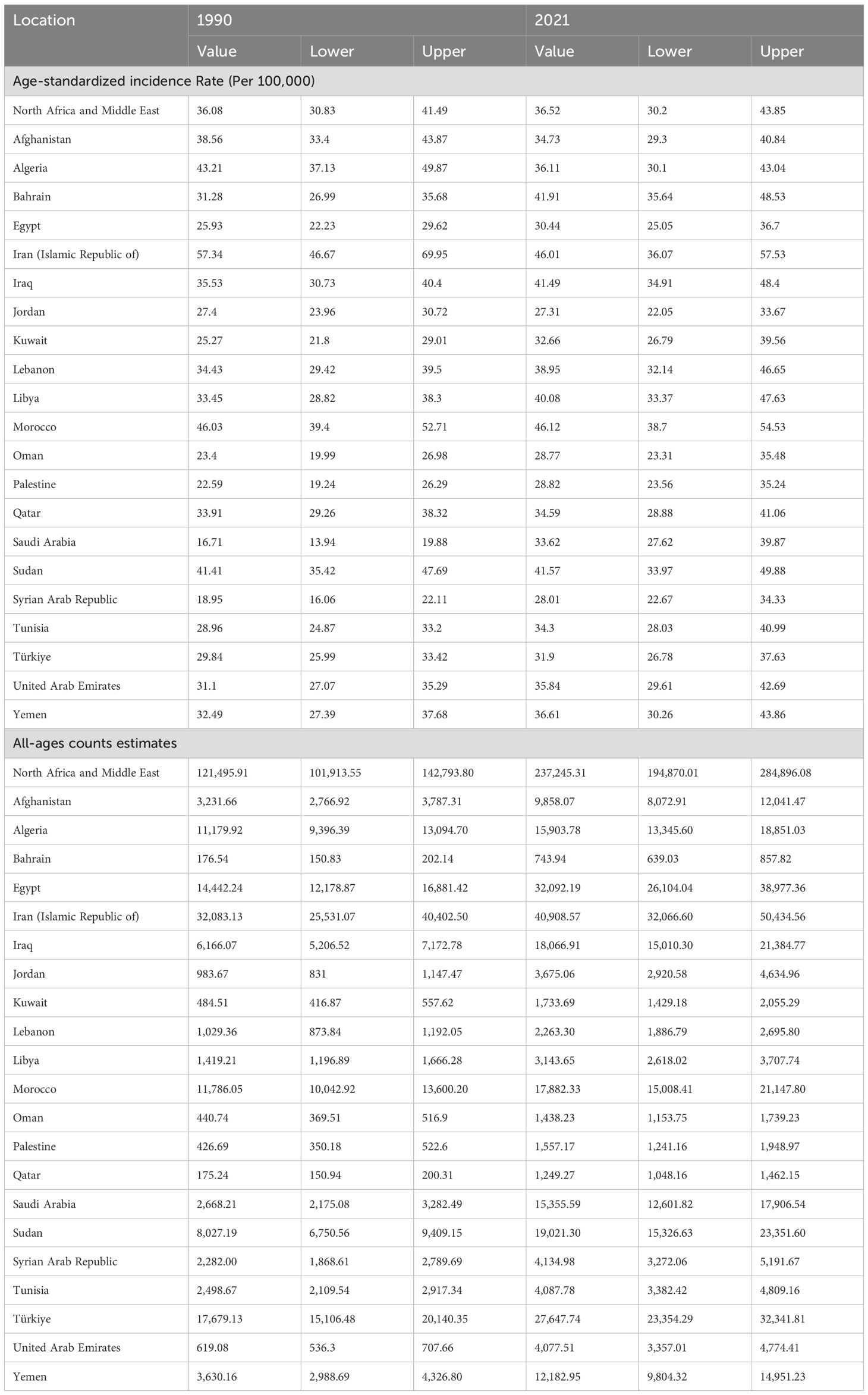

The age-standardized incidence rate of self-harm in MENA was 36.08 [95% UI 30.83 to 41.49] per 100,000 in 1990, and there was a very slight increase to 36.52 [95% UI 30.2to 43.85] per 100,000 in 2021 (Table 2). The percentage change from 1990 to 2021 shows a positive trend of 1% [95% UI −4 to 7]. The incidence rate of self-harm from 1990 to 2021 showed an almost constant trend with a slight fluctuation (Figure 3).

Table 2. All-ages counts and age-standardized incidence rate (Per 100,000) of self-harm in MENA, 1990–2021.

The all-age count estimates that the incidence of self-harm in MENA was 121,495 [95% UI 101,913 to 142,793] in 1990, and this rate increased to 237,245 [95% UI 194,870 to 284,896] in 2021. The percentage change from 1990 to 2021 showed a sharp increase of 95% [95% UI 83 to 111] (Figure 4).

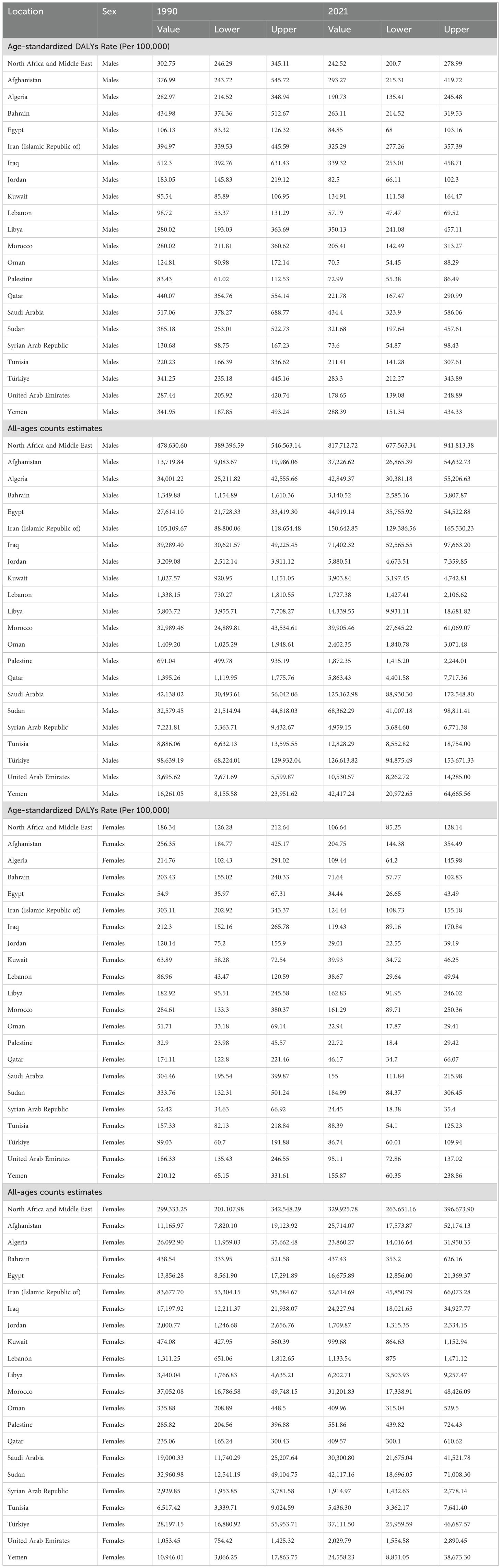

Disability-Adjusted Life Years of self-harm in MENA from 1990 to 2021

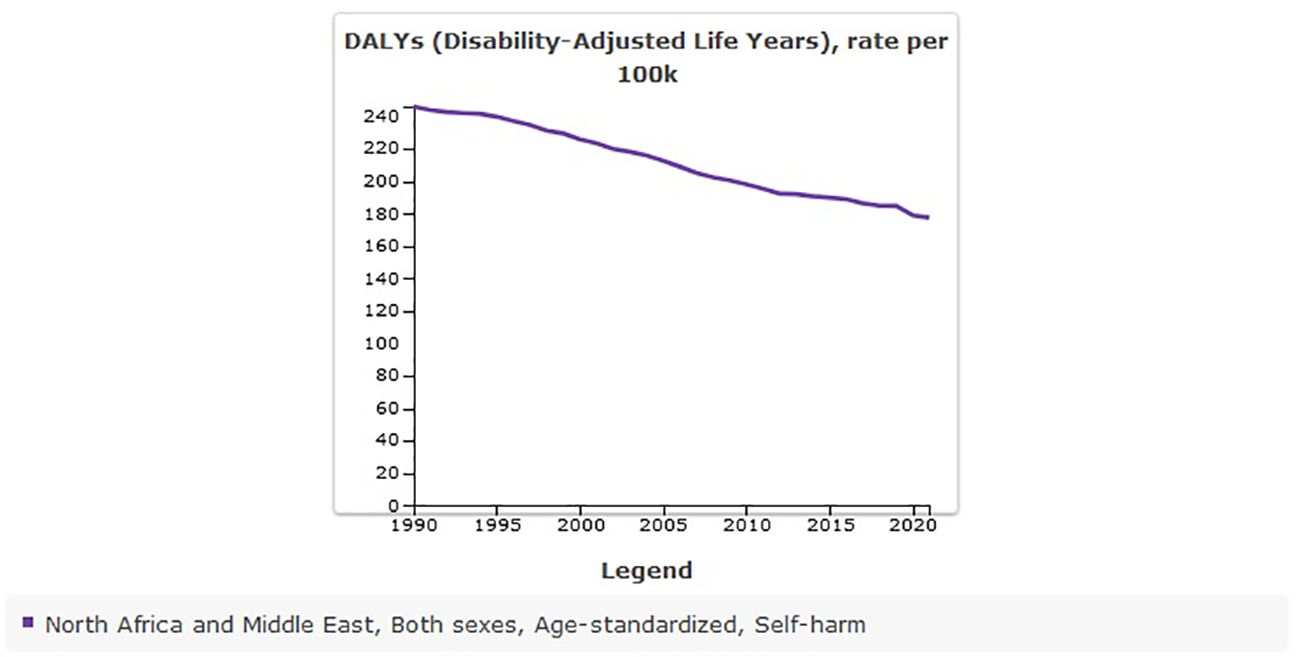

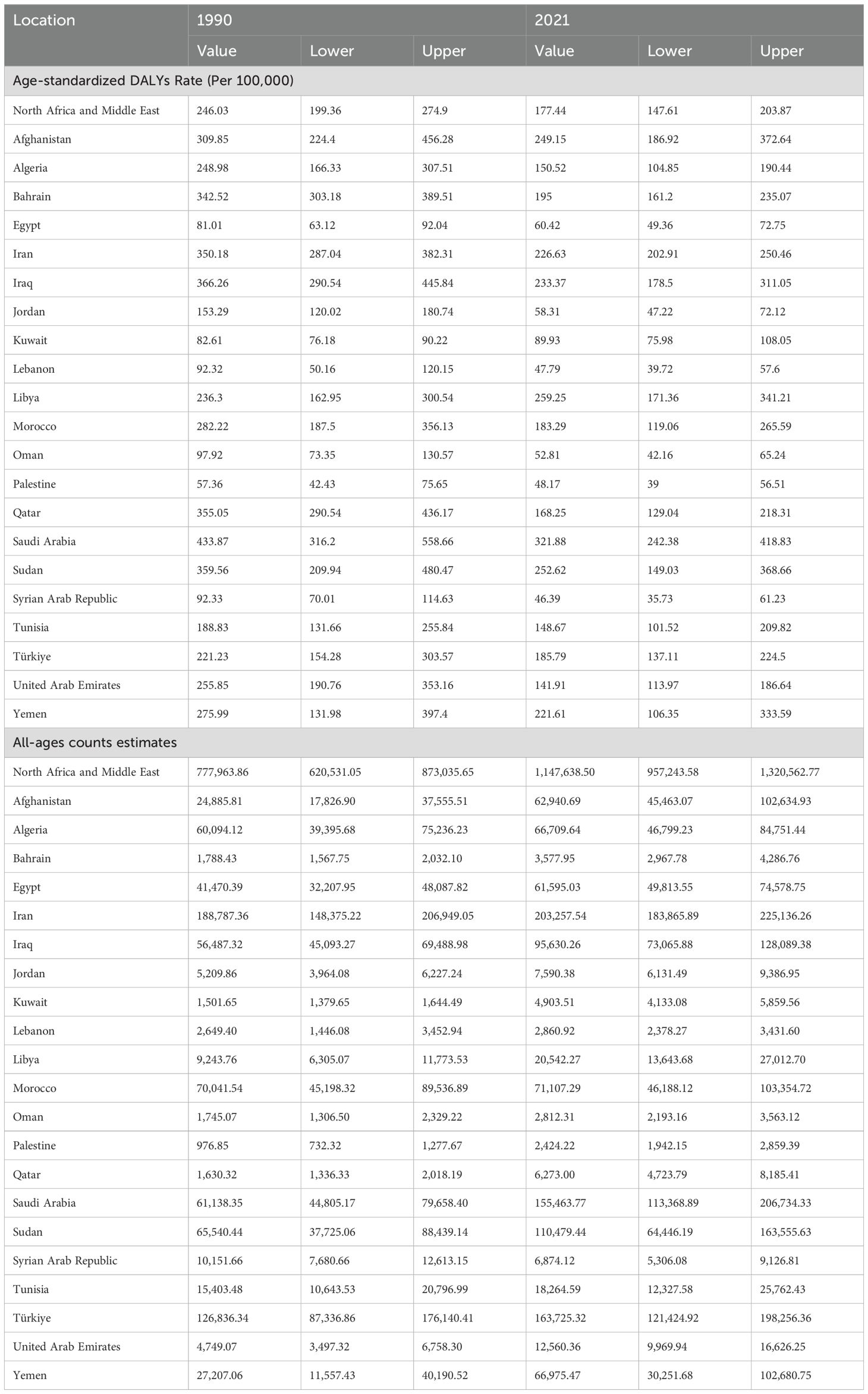

The age-standardized DALYs rate of self-harm in MENA was 246.03 [95% UI 199.36 to 274.9] per 100,000 in 1990, and there was a decrease to 177.44 [95% UI 147.61 to 203.87] per 100,000 in 2021 (Table 3). The percentage change from 1990 to 2021 showed a negative trend of −0.28% [95% UI −0.37 to −0.06] (Figure 5).

Table 3. All-ages counts and age-standardized DALYs rate (Per 100,000) of self-harm in MENA, 1990–2021.

The number of DALYs due to self-harm in MENA was 777,963 [95% UI 620,531 to 873,035] in 1990, and this rate increased to 1,147,638 [95% UI 957,243 to 1,320,562] by 2021. The percentage change from 1990 to 2021 showed a sharp increase of 48% [95% UI 29 to 92].

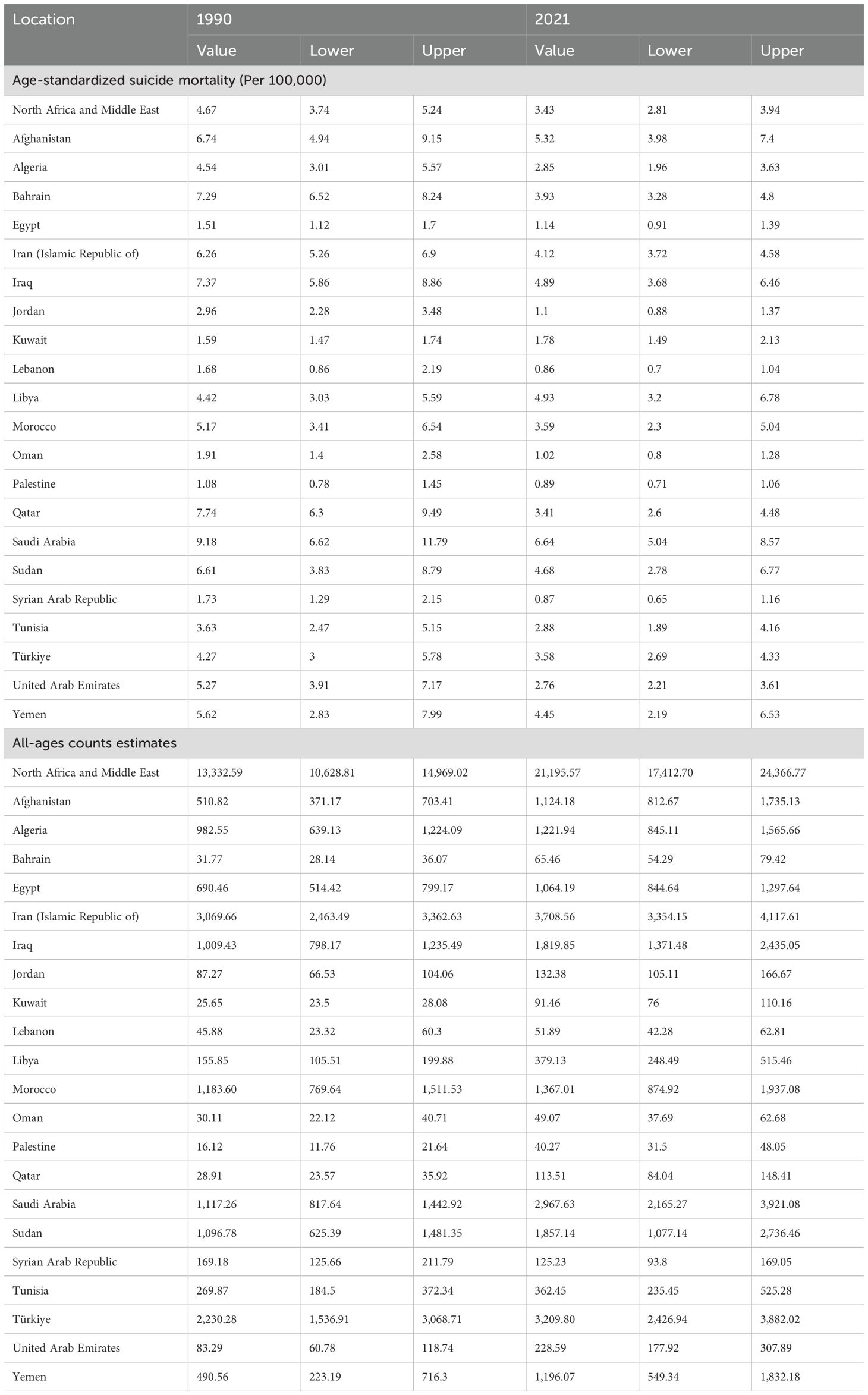

Suicide mortality in MENA from 1990 to 2021

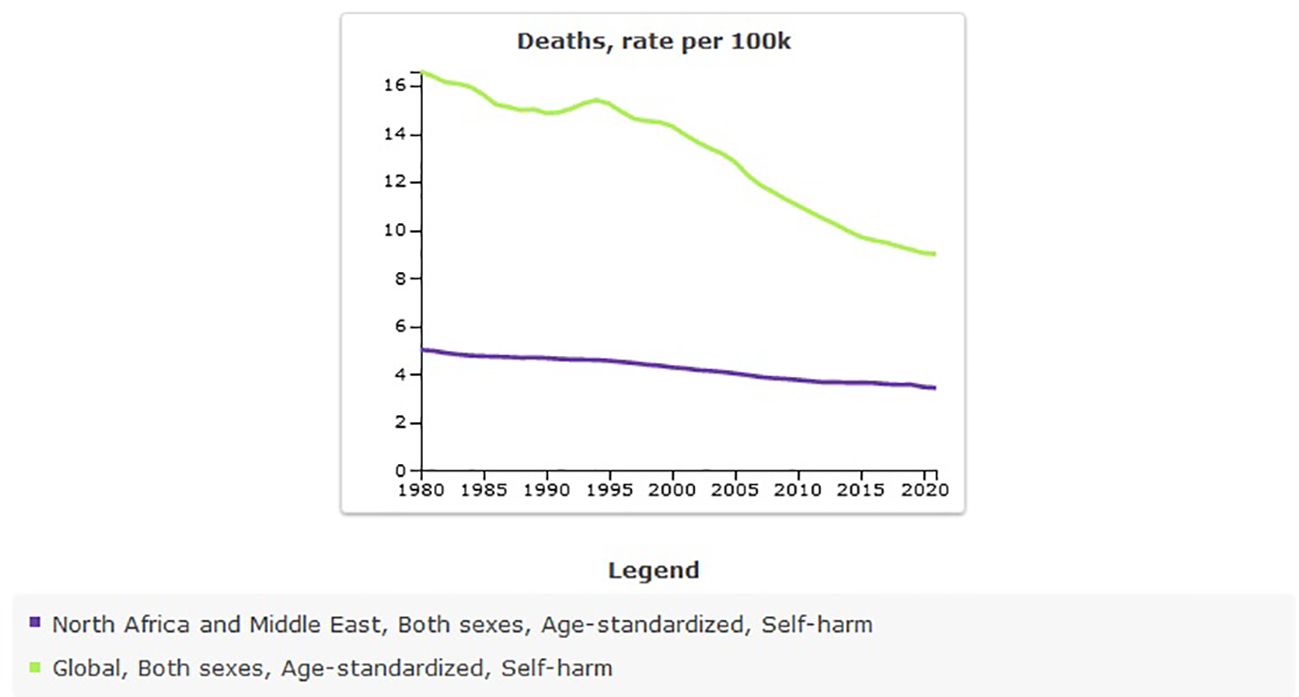

The age-standardized rate of suicide mortality in MENA was 4.67 [95% UI 3.74 to 5.24] per 100,000 in 1990, and this rate decreased to 3.43 [95% UI 2.81 to 3.94] per 100,000 in 2021 (Table 4). The percentage change from 1990 to 2021 showed a negative trend of −27% [95% UI −36 to −4]. The global age-standardized rate of suicide mortality is 8.99 per 100,000 individuals in 2021. Compared with the global population, suicide mortality was less prevalent in MENA from 1990 to 2021 (Figure 6). The prevalence of suicide mortality in MENA countries was lower than in other countries (Figure 7).

Table 4. All-ages counts and age-standardized rate (Per 100,000) of suicide mortality in MENA, 1990–2021.

More than 21,000 suicide mortalities were estimated in MENA in 2021, which was estimate for 1990 was 13,332 [95% UI 10,628 to 14,969]. This shows that, despite the decrease the in age-standardized prevalence rate, the number of suicide deaths has increased.

The sex-specific burden of self-harm and suicide mortality in MENA

Sex-specific prevalence of self-harm in MENA showed that the age-standardized prevalence rate (per 100,000) in 2021 was higher in females (112.57 [95% UI 95.65 to 134.77]) than in males (99.67 [95% UI 86.59 to 116.49]) (Table 5).

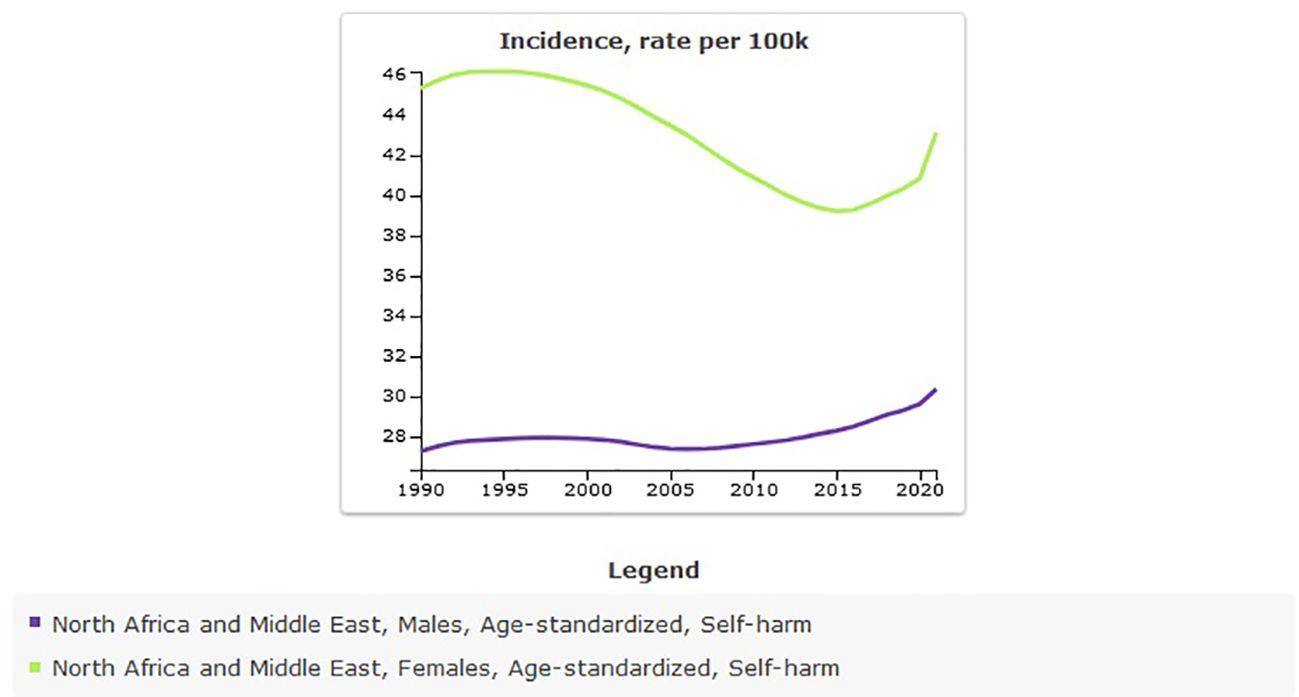

The incidence of self-harm in MENA showed that the age-standardized incidence rate (per 100,000) in 2021 was higher in females (43.12 [95% UI 35.33to 52.24]) than in males (30.36 [95% UI 25.33 to 35.93]) (Table 6).

The trend of incidence of self-harm in males and females from 1990 to 2021 showed that the trend in females decreased, but it increased in males (Figure 8). DALYs of self-harm rate per 100,000 in 2021 were higher in males (242.52 [95% UI 200.7 to 278.99]), than in females (106.64 [95% UI 85.25 to 128.14]). The trend of DALYs caused by self-harm in both sexes showed a decreasing trend compared with 1990 (Table 7).

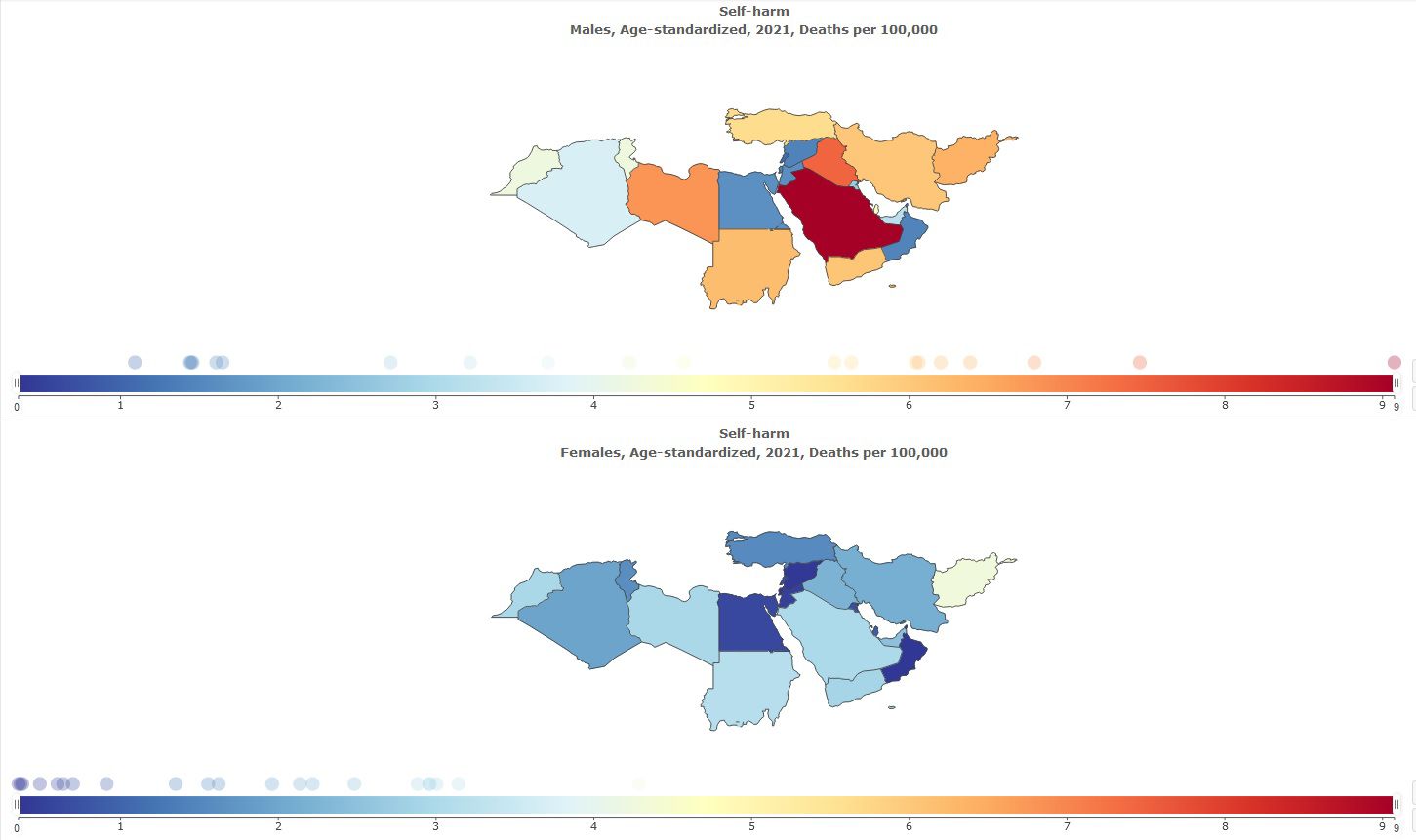

Suicide mortality was more common in males than in females; the age-standardized prevalence rate (per 100,000) of suicide mortality in 2021 was 4.83 [95% UI 3.98 to 5.56] in males and 1.92 [95% UI 1.47 to 2.30] in females (Table 8, Figure 9).

Figure 9. Sex specific age-standardized suicide mortality rate in MENA, stratified by country, 1990-2021.

Discussion

This study deals with self-harm and suicide mortality in MENA from 1990 to 2021 based on sex and country. Based on this, the prevalence, incidence, DALYs, and suicide mortality in 21 countries according to sex were presented and compared with the global population.

This level of prevalence of self-harm compared to 1990 showed a decreasing trend, and it has also been shown that the estimated prevalence of self-harm is higher in females than in males. This decrease in self-harm over the last three decades may involve different mechanisms. The first point that is evident in MENA is that it especially affects mental health. Sociodemographic and religious commonalities are some of the factors that especially affect the tendency to self-harm and suicide mortality. In addition, the study shows that religiosity is protective against suicide (25–27). The dominant religion of the MENA countries is Islam, and most of the population in these countries are Muslims; according to Islamic teachings, self-harm is forbidden, and suicide is considered unforgivable from God’s point of view and prohibited by Islam (28, 29).

Previous studies have also shown a downward trend in suicide rates in this region (30). Similar to previous studies, this study showed that countries with Muslim populations have a lower prevalence of suicide (31, 32). Being religious is a protective factor against self-harm and suicide, even though this region has been involved in conflict, war, displacement, migration, and poverty for decades. In the past decades, this super region has witnessed an improvement in morbidity and mortality due to improvements in health care, health education, socioeconomic developments (11), and mental health infrastructure (33, 34). The stigma surrounding suicide can influence reported estimates, as many families choose to conceal deaths resulting from suicide due to the associated shame. The tendency to hide such cases can distort the accuracy of suicide-related statistics in the region.

However, the results clearly indicate an increase in the number of self-harm incidents and suicide-related deaths. Over the past three decades, the global population, as well as that of this region, has grown substantially (35), which requires an increase in health infrastructure and access to healthcare, especially mental healthcare. However, health systems in this region have faced challenges (34), which have affected the health performance of countries, and conflicts and wars have also increased the burden on the health system. As a result of conflicts and wars, migration also increases and people are displaced from their places of residence. As the literature also shows, there is an increase in mental disorders as a result of migration and displacement (15, 36). Accordingly, the increase in the number of self-harm and suicide deaths does not seem unusual.

Another finding of this study was the sex differences in the rate of self-harm and suicide mortality, which showed that self-harm is more common in females than in males, but the prevalence of suicide mortality is higher in males. The findings obtained from previous studies also confirm the higher prevalence of self-harm in females than in males; this sex difference has been shown in adolescents and adults (37, 38). Suicidal mortality has also been shown to be more common in males than females (39, 40). Mechanisms have been identified for the higher prevalence of self-harm in females (37). Individual, interpersonal, and sociocultural factors are associated with high levels of depression and distress in females (41). The tendency toward rumination also has an important relationship with self-harm (42). Depression is one of the main causes of suicide. Depression is more common in females, but suicide mortality is more common in males, and there is a paradox (39). In explaining these differences, three factors should be considered “methods used by suicide attempters, lethality of the suicidal act, and intent to die” (43). In females, the use of pills for suicide is more common, and in males, the use of firearms or hanging oneself is more common (44–47). The degree of suicide attempt among females is less lethal (46). There is a difference between males and females in the intention to die (48, 49); in men compared to females, this intention to die is more serious (43). In addition, some biological and cultural factors have been proposed to explain gender differences in suicidal behaviors, including glutaminergic activity (50), sleep time (51), spirituality, and coping skills (52). Therefore, the risk factors for suicidal behavior in women and men are different (53), and these should be considered in explanations.

Not all countries in the region had similar rates of self-harm and suicide mortality and there was a disparity. These differences can be influenced by many factors, some of which can be attributed to the performance of the health systems in these countries. In addition, there are cultural differences, as suicide has high stigma in some countries, which may have affected the estimates obtained. At the political level, some countries in this region have been involved in conflicts and long wars, which have affected the performance of the mental health care system. There is also inequality in economic conditions, such that some countries have a high level of welfare, and some other countries have a high level of poverty and economic and social problems. Therefore, any of these factors can affect differences in the rates of self-harm and suicide in these countries.

Limitations

This was a comprehensive effort to examine the burden of self-harm and suicide mortality in MENA, covering more than three decades, assessing sex differences, and reporting decompositions in 21 countries. This research has limitations according to the Global Burden of Disease study, including the quality and collection of primary data and inconsistency of data availability. The challenges of measuring suicidal behaviors in conflict settings and the impact of missing or biased data should be considered. In addition to the methodological limitations that exist in GBD, some cultural limitations can also affect the estimation of the results in this region. For example, the stigmatization effects of self-harm and suicidal behaviors traditionally exist in this area, and, as a result, the estimates obtained may differ from the true extent. Most countries in this region have predominantly Muslim populations, and in Islam, self-harm and suicide are considered sins. These religious teachings can affect the estimates obtained because families may hide suicide. Raw data are not available for some countries or the data are not up-to-date, and these are extracted and estimated from other countries based on specific methodologies. This uncertainty, as noted in a previous study (Yan et al., 2024), may have affected the estimates.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed a trend of reducing self-harm and suicide mortality in MENA in recent decades. Self-harm was more common in females than males, but suicide mortality was more common in males. Despite the decrease in the rates of suicide mortality and self-harm, the rates of suicide mortality and self-harm have increased. Therefore, in this context, there is a need to provide structures related to mental health care, screening, prevention, and treatment in a more comprehensive manner, as well as to accurately identify risk factors. Another suggestion involves incorporating mental healthcare into the primary healthcare system. Additionally, providing structured education within families and schools can play a crucial role in enhancing mental health literacy, ultimately helping alleviate the impact of mental disorders.

Data availability statement

The data sources of this study were taken from GBD 2021, which is publicly available here: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/.

Author contributions

MABK: Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Validation. SA: Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Knipe D, Padmanathan P, Newton-Howes G, Chan LF, Kapur N. Suicide and self-harm. Lancet. (2022) 399:1903–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00173-8

2. World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern M. Suicide and self-harm. Cairo: World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2019).

3. Zhou X, Li R, Cheng P, Wang X, Gao Q, Zhu H. Global burden of self-harm and interpersonal violence and influencing factors study 1990–2019: analysis of the global burden of disease study. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:1035. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18151-3

4. Diggins E, Heuvelman H, Pujades-Rodriguez M, House A, Cottrell D, Brennan C. Exploring gender differences in risk factors for self-harm in adolescents using data from the Millennium Cohort Study. J Affect Disord. (2024) 345:131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.10.106

5. Evaluation IfHMa. Self-harm (2024). Available online at: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/diseases-injuries-risks/factsheets/2021-self-harm-level-3-disease (Accessed January 1, 2025).

6. WHO. Suicide (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (Accessed January 1, 2025).

7. World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern M. Mental Health, Brain Health and Substance Use (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/data-research/suicide-data (Accessed January 1, 2025).

8. Bachmann S. Epidemiology of suicide and the psychiatric perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:1425. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071425

9. Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet (London England). (2016) 388:1459–544.

10. Skuse D. Conflict and mental health in North Africa and the Middle East. Int Psychiatry. (2013) 10:55–6. doi: 10.1192/S1749367600003830

11. Mate K, Bryan C, Deen N, McCall J. Review of Health Systems of the Middle East and North Africa Region. International Encyclopedia of Public Health (2017) 347–56. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-803678-5.00303-9

12. WHO. Mental health and forced displacement (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-and-forced-displacement.

13. Blackmore R, Boyle JA, Fazel M, Ranasinha S, Gray KM, Fitzgerald G, et al. The prevalence of mental illness in refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS Med. (2020) 17:e1003337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003337

14. Zabarra M, Obtel M, Sabri A, El Hilali S, Zeghari Z, Razine R. Prevalence and Risk Factors associated with Mental Disorders among Migrants in the MENA region: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. (2024), 117195. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.117195

15. Amiri S. Prevalence of suicide in immigrants/refugees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch suicide Res. (2022) 26:370–405. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2020.1802379

16. Betts A, Loescher G, Milner J. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR): The politics and practice of refugee protection. Routledge (2013).

17. Taghizadeh Moghaddam H, Sayedi SJ, Emami Moghadam Z, Bahreini A, Ajilian Abbasi M, Saeidi M. Refugees in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Needs, problems and challenges. Int J Pedia. (2017) 5:4625–39. doi: 10.22038/ijp.2017.8452

18. Assaad R, Roudi-Fahimi F. Youth in the Middle East and North Africa: Demographic opportunity or challenge? Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau (2007), 1–8.

19. Yüceşahin M, Tulga A. Demographic and social change in the Middle East and North Africa: processes, spatial patterns, and outcomes. Population Horizons. (2017) 14:2.

20. Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, Abate YH, Abbafati C, Abbastabar H, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990&x2013;2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. (2024) 403:2133–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8

21. Self-harm—Level 3 cause (2024). Available online at: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/diseases-injuries-risks/factsheets/2021-self-harm-level-3-disease (Accessed January 1, 2025).

22. GBD 2021 Suicide Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Public Health. (2025) 10:e189–e202. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(25)00006-4

23. Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray JLC. editors. Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank (2006). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11812/. Co-published by Oxford University Press, New York.

24. Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, Boerma JT, Collins GS, Ezzati M, et al. Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet. (2016) 388:e19–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30388-9

25. Gearing RE, Alonzo D. Religion and suicide: new findings. J religion Health. (2018) 57:2478–99. doi: 10.1007/s10943-018-0629-8

26. Lawrence RE, Oquendo MA, Stanley B. Religion and suicide risk: A systematic review. Arch suicide Res. (2016) 20:1–21. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1004494

27. Wu A, Wang JY, Jia CX. Religion and completed suicide: a meta-analysis. PloS One. (2015) 10:e0131715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131715

29. Shoib S, Armiya'u AY, Nahidi M, Arif N, Saeed F. Suicide in Muslim world and way forward. Health Sci Rep. (2022) 5:e665. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.v5.4

30. Lew B, Lester D, Kõlves K, Yip P, Chen Y-Y, Chen W, et al. An analysis of age-standardized suicide rates in Muslim-majority countries in 2000-2019. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:882.

31. Daouk S, Dailami M, Barakat S, Awaad R, Muñoz RF, Leykin Y. Suicidality in the Arab world: results from an online screener. Community Ment Health J. (2023) 59:1401–8. doi: 10.1007/s10597-023-01129-7

32. Arafat SMY, Rezaeian M, Khan MM. “Suicidal behavior in Islamic countries: An overview”. In: Arafat S. M. Y., Rezaeian M., Khan M. M. (Eds.), Suicidal behavior in Muslim majority countries: Epidemiology, risk factors, and prevention. Switzerland AG: Springer Nature (2024). pp. 1–18. doi: 10.1007/978-981-97-2519-9_1

33. Sobhani M, Saeidi P, Naeim M, Kavand R, Shojaei B, Imannezhad S, et al. Improving mental health infrastructure across the Middle East. Asian J Psychiatry. (2024) 93:103908. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103908

34. Katoue MG, Cerda AA, García LY, Jakovljevic M. Healthcare system development in the Middle East and North Africa region: Challenges, endeavors and prospective opportunities. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:1045739. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1045739

35. Ahmad K. Global population will increase to nine billion by 2050, says UN report. Lancet. (2001) 357:864. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71800-6

36. Cogo E, Murray M, Villanueva G, Hamel C, Garner P, Senior SL, et al. Suicide rates and suicidal behaviour in displaced people: A systematic review. PloS One. (2022) 17:7:e026379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263797

37. Lutz NM, Neufeld SAS, Hook RW, Jones PB, Bullmore ET, Goodyer IM, et al. Why is non-suicidal self-injury more common in women? Mediation and moderation analyses of psychological distress, emotion dysregulation, and impulsivity. Arch suicide Res. (2023) 27:905–21. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2022.2084004

38. Moloney F, Amini J, Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Lanctôt KL, Mitchell RHB. Sex differences in the global prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents: A meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. (2024) 7:e2415436. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15436

39. Murphy GE. Why women are less likely than men to commit suicide. Compr Psychiatry. (1998) 39:165–75. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(98)90057-8

40. Richardson C, Robb KA, O'Connor RC. A systematic review of suicidal behaviour in men: A narrative synthesis of risk factors. Soc Sci Med. (2021) 276:113831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113831

41. Hyde JS, Mezulis AH. Gender differences in depression: biological, affective, cognitive, and sociocultural factors. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. (2020) 28:4–13. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000230

42. Voon D, Hasking P, Martin G. The roles of emotion regulation and ruminative thoughts in non-suicidal self-injury. Br J Clin Psychol. (2014) 53:95–113. doi: 10.1111/bjc.2014.53.issue-1

43. Shelef L. The gender paradox: do men differ from women in suicidal behavior? J men's Health. (2021) 17:22–9. doi: 10.31083/jomh.2021.099

44. Denning DG, Conwell Y, King D, Cox C. Method choice, intent, and gender in completed suicide. Suicide Life-Threat Behavior. (2000) 30:282–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2000.tb00992.x

45. De Leo D, Kõlves K. Suicide at very advanced age—The extremes of the gender paradox [Editorial]. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention (2017) 38(6):363–6. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000514

46. Cantor CH. “Suicide in the western world”. In: The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide (2000), 9–28.

47. Shaffer D, Pfeffer CR. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2001) 40:24S–51S. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107001-00003

48. Freeman A, Mergl R, Kohls E, Székely A, Gusmao R, Arensman E, et al. A cross-national study on gender differences in suicide intent. BMC Psychiatry. (2017) 17:234. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1398-8

49. Jaworski K. Suicide and gender: Reading suicide through butler's notion of performativity1. J Aust Stud. (2003) 27:137–46. doi: 10.1080/14443050309387832

50. Dean B, Duncan C, Gibbons A. Changes in levels of cortical metabotropic glutamate 2 receptors with gender and suicide but not psychiatric diagnoses. J Affect Disord. (2019) 244:80–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.088

51. Park WS, Kim S, Kim H. Gender difference in the effect of short sleep time on suicide among Korean adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:3285. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16183285

52. Mirkovic B, Belloncle V, Pellerin H, Guilé J-M, Gérardin P. Gender differences related to spirituality, coping skills and risk factors of suicide attempt: A cross-sectional study of French adolescent inpatients. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.537383

Keywords: prevalence, incidence, self-harm, suicide mortality, global burden of disease, Middle East and North Africa

Citation: Khan MAB and Amiri S (2025) Prevalence, incidence, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years of self-harm and suicide mortality in the Middle East and North Africa: a sex-specific study based on Global Burden of Disease. Front. Psychiatry 16:1529941. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1529941

Received: 18 November 2024; Accepted: 24 February 2025;

Published: 21 March 2025.

Edited by:

Mohammadreza Shalbafan, Iran University of Medical Sciences, IranReviewed by:

Areiba Arif, O.P. Jindal Global University, IndiaAhlem Silini, Tunis El Manar University, Tunisia

Rubens Wajnsztejn, Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, Brazil

Alice Demesmaeker, Université de Lille, France

Copyright © 2025 Khan and Amiri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sohrab Amiri, YW1pcnlzb2hyYWJAeWFob28uY29t

Moien AB Khan

Moien AB Khan Sohrab Amiri

Sohrab Amiri