- 1Private Practitioner, Solothurn, Switzerland

- 2Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, University Hospital Basel and University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

A 64-year-old male patient who suffered from traumatic life experiences and neuropathic pain after oncological chemotherapy was treated with medium to high doses of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and high doses and microdoses of methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA). At the beginning of treatment, the patient did not experience any acute subjective effects of LSD at a dose of 200 µg. After increasing the LSD dose to 400 µg, he experienced subjective acute effects, and the first lasting therapeutic effects were observed. After changing from LSD to MDMA at both high doses (150-175 mg) and repeated low doses (12.5-25 mg), the patient exhibited marked improvements in neuropathic pain that were sustained even after stopping repeated MDMA treatment. MDMA mini/microdosing has not yet been broadly investigated. This case documents benefits of low doses of MDMA for the treatment of a pain disorder. Further research is needed on effects of MDMA on pain.

Background

Since the early 1960s, the analgesic efficacy of classic psychedelics, which act via agonism on serotonin 2A receptors, in the treatment of cancer patients has been questioned (1). Experimental results have been inconclusive, and treatment with psychedelics has subsequently focused on psychological disorders and coping with life-threatening and sometimes painful illnesses (2–5). However, Goel et al. (6) reported evidence of an analgesic effect of psychedelics on tumor-related pain and certain forms of headache. Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), which is not considered a classic psychedelic, acts as monoamine and oxytocin releasing agent (7, 8). It has shown only limited evidence of an analgesic effect that goes beyond more immediate effects of the substance (9). In a study in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder, MDMA reduced chronic pain intensity and disability in a subgroup of patients with the highest chronic pain scores (9). Our own clinical research and experiences have led us to suspect that acute effects of psychedelics can lead to pain relief through general relaxation and focusing on other areas of experience, but they can also lead to pain intensification through a stronger focus on the pain itself. Among classic psychedelics, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin have shown a pain-mitigating effect through microdosing (i.e., the intake of low doses with minimal acute psychedelic effects every few days over several weeks or months), which has been reported in individual case reports or anecdotal reports (10). We found no related published reports for MDMA. In the present case, we observed improvements of a neuropathic pain disorder with both high doses (150-175 mg) and low doses (12.5-25 mg) of MDMA.

Case presentation

The male patient, born in 1960, was 58-64 years old during the course of treatment. He grew up as the older of two sons in a rural area of Switzerland in a middle-class family. He and his brother suffered from severe physical abuse at the hands of their father throughout childhood and adolescence, and they were not protected by their mother, who did not intervene. During adolescence, the patient experienced a severe psychological crisis with the temporary excessive consumption of legal and illegal substances of abuse (alcohol, tobacco, marihuana, heroin, cocaine). Despite this, he managed to stabilize himself psychologically, complete an apprenticeship as a mechanic, and continue his education to become an engineer. He also entered a stable relationship with a woman with whom he has a child.

A traumatic separation from his wife occurred in 2010. In the same year, he was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, which was treated with chemotherapy, which was discontinued prematurely after three treatment cycles in 2011 because of hepatotoxicity. In the subsequent years, the patient developed a diffuse painful polyneuropathy.

After the separation the patient became mentally destabilized. He was no longer able to work. He later became a disability pensioner. In 2012, he started permanent psychotherapeutic treatment, followed by two 3-month psychiatric/psychosomatic hospitalizations in 2013 and 2016, where he was diagnosed for continuous severe depression and complex posttraumatic stress disorder.

In 2020, he was diagnosed with metastatic colon carcinoma, which was treated with surgery and chemotherapy. This again intensified the neuropathy symptoms. Despite extensive polypharmacological treatment with paracetamol, ibuprofen, antiepileptics (pregabalin, carbamazepine), antidepressants (sertraline, escitalopram, trimipramine), sedative neuroleptics (quetiapine), and benzodiazepines (lorazepam), there was no improvement of the polyneuropathy. The patient also suffered from recurring pain in the lower sacral region following a vertebral disc herniation. This pain responded to treatment with analgesics and/or local infiltrations with cortisol and local anesthetics.

Treatment

Participation in study

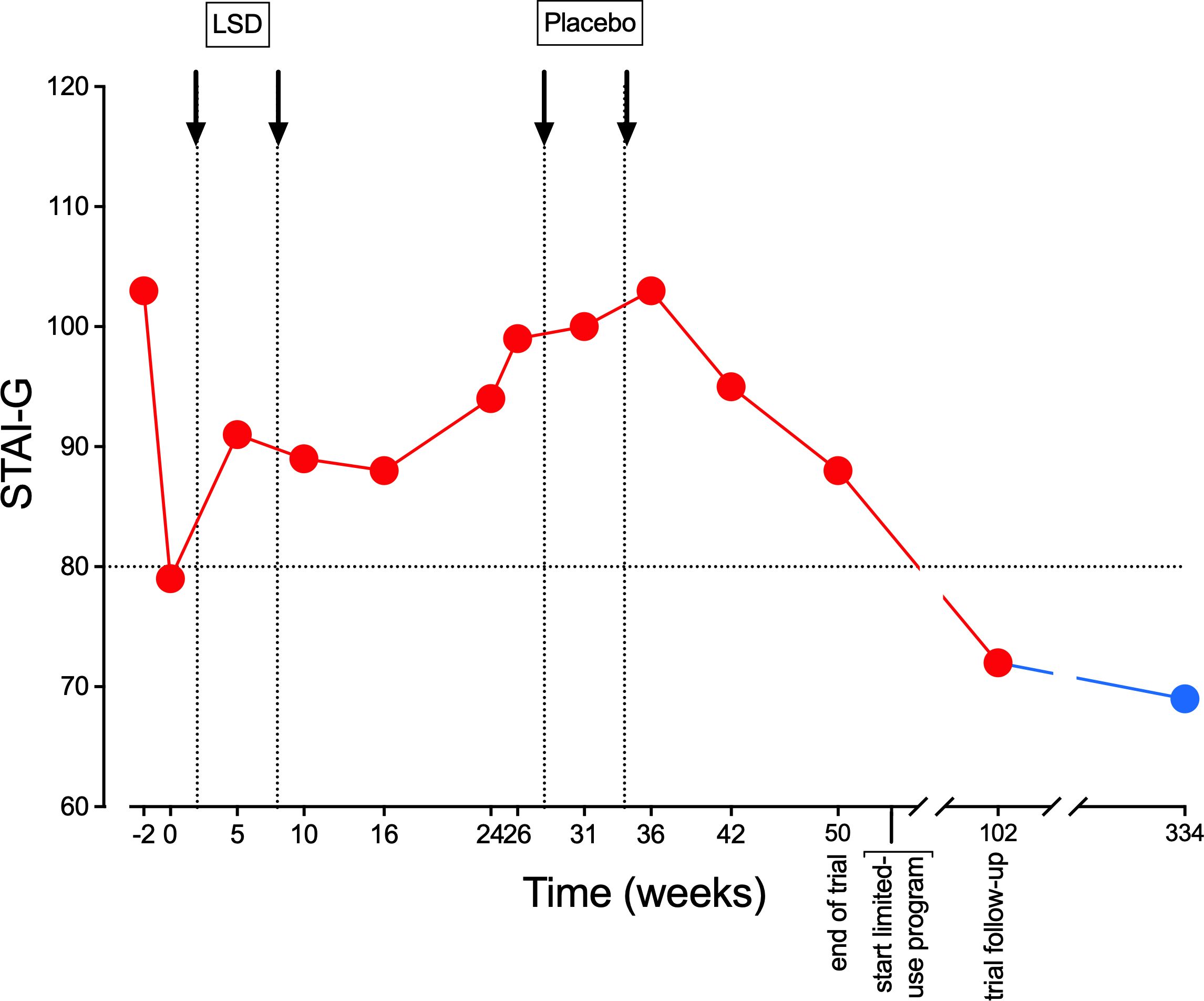

The patient registered as a participant in a study of LSD in patients with anxiety-related life-threatening illness (5, 11) in January 2018. He underwent two sessions with 200 µg LSD each. During the study treatments, which he completed in March 2019, he did not experience any subjective or objective LSD-typical effects. Subjective effect ratings on the 5-Dimensions of Altered States of Consciousness (5D-ASC) rating scale were the following (average of both sessions): 5D-ASC total score = 2.2% of a possible maximum score of 100%; 3D-ASC total score = 2.8/100%. Such low subjective effect scores (< 10% of the total 5D-ASC score) were only seen in two patients of the total of 40 patients who received LSD in the study. Figure 1 presents the course of the measurement of anxiety symptoms using the Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), showing that LSD had no anxiety-reducing effect in that patient.

Figure 1. Non-response to LSD on the Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Values represent repeated ratings on the STAI-Global scale, which is the sum of STAI-State and STAI-Trait ratings. Scores of > 80 were needed for study inclusion, representing significant anxiety. The red dots are measures during the study. The blue dot is a measure on June 14, 2024, 334 weeks after start of the study, after 10 LSD and three MDMA dosing sessions during the limited medical use treatment phase that is described in the present report.

Further limited medical treatment

After the end of the study, participants who had an insufficient response were allowed to obtain limited medical use treatment with LSD and MDMA with authorization from the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Authorization for the limited medical use of LSD in this patient was granted in February 2019. Throughout this treatment, STAI ratings fell permanently to values below 80, which is defined as the threshold for relevant anxiety symptoms. Between May 2019 and May 2024, the patient underwent a total of 10 dosing sessions with LSD (250-400 µg), followed by three dosing sessions with MDMA (150-175 mg). All of these experiences occurred in a group setting (group size = 5-8 participants with two therapists, including preparation and integration sessions within the group). Patients were asked to write an experience report after each treatment session. These diary-like reports had no formal requirements and served to improve the memorability and integration of psychedelic experiences and help reestablish the connection to the psychedelic experience in subsequent individual psychotherapeutic sessions. Table 1 summarizes statements from these reports that were important for the therapeutic process and assigns them to therapy-relevant topics. The therapy-relevant topics were defined in consultation with the patient. In the total of 13 psychedelic sessions after the LSD study, the patient increasingly had experiences that were typical of LSD and MDMA. We interpreted the non-responding phase in the LSD study as a psychological unconscious defense. During this 5 years of therapy, the patient underwent an intensive process of physical and psychological stabilization, which today allows the patient to have a significantly better quality of life. He has reentered an intimate partnership after a break of more than 10 years. He can experience feelings of love for his partner, his two grandchildren, and their parents. He no longer suffers from insomnia, which was a chronic problem in the past. His relationship to death and dying has relaxed considerably.

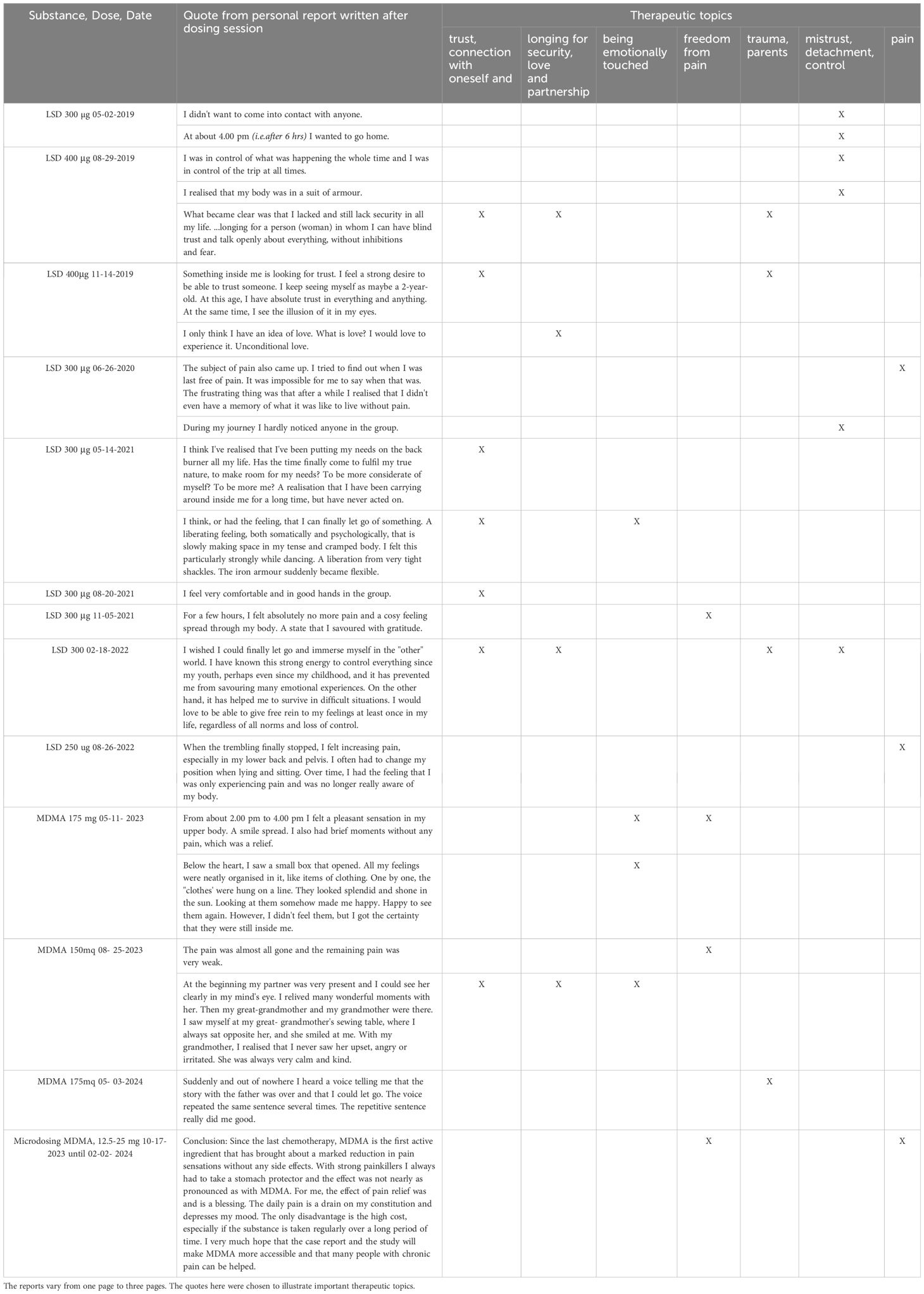

Table 1. Synopsis of quotes from individual non-structured reports written shortly after the psychedelic therapy sessions.

He has completely stopped his antidepressants, neuroleptics, and benzodiazepines. However, pain medication is still necessary occasionally, as well as for back pain and peaks of neuropathy. If neuropathic pain becomes more severe, then he currently takes nasal ketamine two to three times monthly. The patient is not a tobacco smoker but smokes a small amount of cannabis three to four times weekly for relaxation alone at home. He does not drink alcohol and since his early twenties he does not consume other illegal substances any more.

Microdosing with MDMA

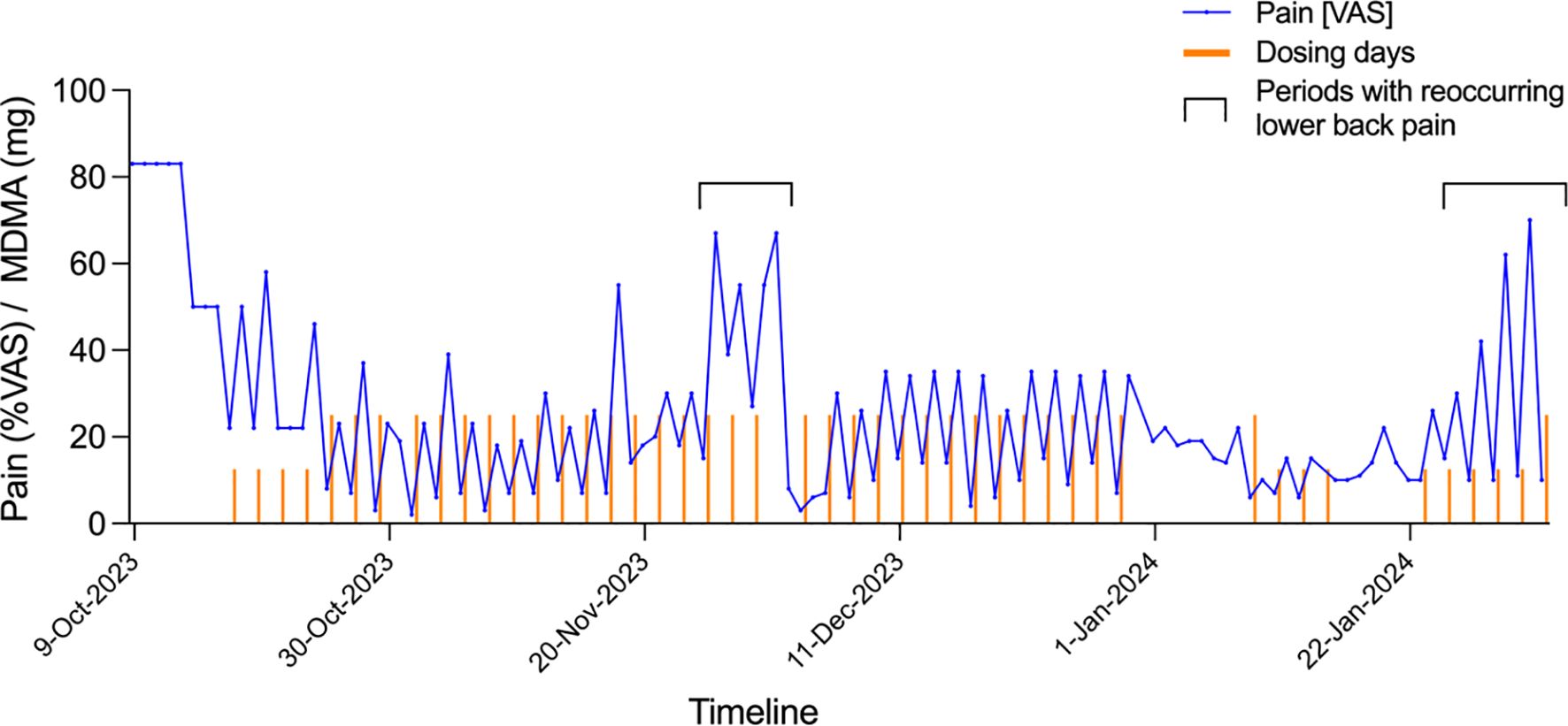

The switch from LSD to MDMA required a new application to the FOPH, which was approved in August 2022. The reason for this change in medication was that the patient’s traumatic childhood came back into the focus of treatment, and he experienced an intensification of neuropathic pain in the tenth and last LSD session, which deterred him from having any further LSD experiences. In all three MDMA sessions, the patient reported a good pain-reducing effect, which lasted for several days after taking the drug. This prompted us to give a series of low-dose treatments to this patient. The threshold dose for a noticeable psychological effect of MDMA was assumed to be 30-40 mg. From October 9, 2023, to February 2, 2024, he took a dose of 25 or 12.5 mg MDMA every other day. These low doses of MDMA did not induce typical psychological effects of MDMA and did not interfere with daily activities. Every day, the patient recorded his pain level using a marker on a Visual Analog Scale (Figure 2).

Figure 2. MDMA microdosing for neuralgic pain after chemotherapy. Columns shown Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores for pain (0 = no pain, 100 = most severe pain). Small red columns indicate treatment days with 12.5 mg MDMA. Large red columns indicate treatment days with 25 mg MDMA. Treatment with 12.5 mg MDMA started on October 17, 2023. The increases in pain November 26, 2023, to December 1, 2023, and January 24, 2024, to February 1, 2024, were attributable to recurrent low back pain. This pain was treated with oral analgesics, including first paracetamol and ibuprofen and then local infiltration with cortisol and a local anesthetic.

Six months after the end of the MDMA microdosing treatment, the neuropathic pain disorder is still well-improved. After the 4-month trial of continuous treatment, the patient took 25 mg MDMA a few times at intervals of several weeks, and in the last 3 months he took ketamine nasal spray, 1-2 strokes of 20 mg/stroke every 1-3 weeks, instead of MDMA. This had a satisfactory pain-relieving effect. Because MDMA can trigger cardiac valve fibrosis (12, 13) we performed two cardiological examinations, including echocardiography before and after the MDMA microdosing treatment phase. Both examinations were unremarkable, and the patient did not complain of cardiac symptoms.

Discussion

The present case report described the treatment of a patient with severe psychological stress from a traumatic childhood and traumatic separation who was undergoing oncology treatment and suffered from psychological distress from this life-threatening disease and experienced chemotherapy-induced diffuse neuropathic pain disorder. No effects of a medium dose of LSD (200 µg) were initially noticed. This made the patient one of the very few non-responders in an LSD study with regard to acute subjective effects and the therapeutic response. Only when the LSD dose was increased to a very high 400 µg dose during further treatment did the patient have an LSD-specific acute reaction. Afterward, the dose was lowered to 250 µg while still experiencing LSD-specific subjective effects. The patient underwent a series of 10 LSD sessions, in which he experienced therapeutic benefits, such as confidence building, a reduction of social anxiety, a reduction of fear of death, improvements in sleep, and a reduction of depressive symptoms. Thus, there was no subjective response and no therapeutic response during the clinical study, but subjective and therapeutic responses could be achieved later with higher doses and repeated LSD treatments outside the constraints of the clinical study and with a Swiss license for the limited medical use of psychedelics. This finding is consistent with the view that greater therapeutic responses are seen in patients who experience greater acute psychedelic effects (5). This could mean that the subjective experience causally contributes to the therapeutic process. It could also mean that patients who are able to perceive and experience emotional and self-altering effects of psychedelics might be more likely to improve, with the subjective effect a predictive biomarker of the therapeutic response. The finding also illustrates that some patients may not respond to the standard dosing of a psychedelic in a clinical trial but may respond to individualized dosing and treatment approaches. With regard to polyneuropathy that occurred during chemotherapy for cancer, the patient experienced no clear progress under LSD treatment. Thus, no analgesic effects of LSD were observed. Only when switching to MDMA-assisted therapy did the patient experience a clear improvement in pain under the acute effect up to 1 week after the single-dose administration. This clinical observation prompted a trial of MDMA microdosing (12.5-25 mg every other day for 4 months). This treatment led to a sustained improvement in neuropathic pain. To our knowledge, a pain-reducing effect of repeated low doses or “microdoses” of MDMA has not been previously reported and would need further confirmatory studies. Reductions of chronic pain have been previously reported among patients with chronic pain who were treated for posttraumatic stress disorder. However, these patients were treated with fully psychoactive doses and only three times (first 120 mg and then 180 mg twice). Thus, full doses of MDMA were used, whereas we also found reductions of pain with repeated every-other-day doses of only 12.5-25 mg that were not psychoactive and did not interfere with daily activities. How MDMA would reduce pain is unclear. It is not known as an analgesic per se. However, in humans, MDMA produces acute effects via the release of norepinephrine, serotonin, and oxytocin (7, 8), which are all known modulators of pain. Animal studies have also shown a possible effect on the opioid system (14). Subjectively, the patient reported that he felt more relaxed overall in everyday life, an impression that was also confirmed by his partner. Thus, MDMA may have influenced aspects of emotional pain processing and cognitive pain perception. MDMA has been shown to reduce the response to negative emotional stimuli, including lower amygdala activation in response to fear (15–18). MDMA may thus reduce negative emotional reactions to pain. It has also been shown to enhance extinction learning (19–21) and may potentially help with pain perception desensitization. MDMA may also enhance positive mood and reduce depressive symptoms, thereby reducing the negative impact of pain on mood (9) rather than primary pain perception. Certainly, diffuse neuropathic pain disorders cannot be treated with muscular relaxation alone, and relaxation that is elicited by MDMA should be seen as more than a muscular relaxation process that promotes such general factors as confidence, trust, and openness (17, 22). Importantly, MDMA continued to exert analgesic effects in the present patient, even when it was administered at doses that did not produce overt emotional effects, indicating additional beneficial effects on pain perception that may be independent of its mood-altering properties.

In conclusion, the present description of an improvement in a neuropathic pain disorder with MDMA is one isolated case that is described in the context of a complex disease state. The mechanisms that led to improvements are largely unexplained. Further observations and ultimately controlled studies are necessary to shed more light on the potential of MDMA in chronic pain disorders.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

PG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. ML: Writing – review & editing. FH: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wilsdorf Mettler Future Foundation for contributing to the costs of the medication and the publication.

Conflict of interest

PG and ML are consultants for Mind Medicine, Inc. PG is former president of the Swiss Medical Society for Psycholytic/Psychedelic Therapy.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Kast EC, Collins VJ. Study of lysergic acid diethylamide as an analgesic agent. Anesth Analg. (1964) 43:285–91. doi: 10.1213/00000539-196405000-00013

2. Pahnke WN, Kurland AA, Goodman LE, Richards WA. LSD-assisted psychotherapy with terminal cancer patients. Curr Psychiatr Ther. (1969) 9:144–52.

3. Grof S, Goodman LE, Richards WA, Kurland AA. LSD-assisted psychotherapy in patients with terminal cancer. Int Pharmacopsychiatry. (1973) 8:129–44. doi: 10.1159/000467984

4. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. (2016) 30:1165–80. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675512

5. Holze F, Gasser P, Muller F, Dolder PC, Liechti ME. Lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted therapy in patients with anxiety with and without a life-threatening illness: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II study. Biol Psychiatry. (2023) 93:215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.08.025

6. Goel A, Rai Y, Sivadas S, Diep C, Clarke H, Shanthanna H, et al. Use of psychedelics for pain: A scoping review. Anesthesiology. (2023) 139:523–36. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004673

7. Hysek CM, Simmler LD, Nicola V, Vischer N, Donzelli M, Krähenbühl S, et al. Duloxetine inhibits effects of MDMA (“ecstasy”) in vitro and in humans in a randomized placebo-controlled laboratory study. PloS One. (2012) 7:e36476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036476

8. Atila C, Holze F, Murugesu R, Rommers N, Hutter N, Varghese N, et al. Oxytocin in response to MDMA provocation test in patients with arginine vasopressin deficiency (central diabetes insipidus): a single-centre, case-control study with nested, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2023) 11:454–64. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00120-1

9. Christie D, Yazar-Klosinski B, Nosova E, Kryskow P, Siu W, Lessor D, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy is associated with a reduction in chronic pain among people with post-traumatic stress disorder. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:939302. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.939302

10. Lyes M, Yang KH, Castellanos J, Furnish T. Microdosing psilocybin for chronic pain: a case series. Pain. (2023) 164:698–702. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002778

11. Holze F, Gasser P, Strebel M, Müller F, Liechti ME. LSD-assisted therapy in people with anxiety: an open-label prospective 12-month follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. (2024) 225(3):362–70. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2024.99

12. Tagen M, Mantuani D, van Heerden L, Holstein A, Klumpers LE, Knowles R. The risk of chronic psychedelic and MDMA microdosing for valvular heart disease. J Psychopharmacol. (2023) 37:876–90. doi: 10.1177/02698811231190865

13. Rouaud A, Calder AE, Hasler G. Microdosing psychedelics and the risk of cardiac fibrosis and valvulopathy: Comparison to known cardiotoxins. J Psychopharmacol. (2024) 38(3):217–24. doi: 10.1177/02698811231225609

14. Belkai E, Scherrmann JM, Noble F, Marie-Claire C. Modulation of MDMA-induced behavioral and transcriptional effects by the delta opioid antagonist naltrindole in mice. Addict Biol. (2009) 14:245–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00156.x

15. Bedi G, Hyman D, de Wit H. Is ecstasy an “empathogen”? Effects of ±3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on prosocial feelings and identification of emotional states in others. Biol Psychiatry. (2010) 68:1134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.003

16. Bedi G, Phan KL, Angstadt M, de Wit H. Effects of MDMA on sociability and neural response to social threat and social reward. Psychopharmacol (Berl). (2009) 207:73–83. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1635-z

17. Hysek CM, Schmid Y, Simmler LD, Domes G, Heinrichs M, Eisenegger C, et al. MDMA enhances emotional empathy and prosocial behavior. Soc Cognit Affect Neurosci. (2014) 9:1645–52. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst161

18. Hysek CM, Domes G, Liechti ME. MDMA enhances “mind reading” of positive emotions and impairs “mind reading” of negative emotions. Psychopharmacology. (2012) 222:293–302. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2645-9

19. Vizeli P, Straumann I, Duthaler U, Varghese N, Eckert A, Paulus MP, et al. Effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on conditioned fear extinction and retention in a crossover study in healthy subjects. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:906639. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.906639

20. Feduccia AA, Mithoefer MC. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD: Are memory reconsolidation and fear extinction underlying mechanisms? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2018) 84:221–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.03.003

21. Young MB, Andero R, Ressler KJ, Howell LL. 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine facilitates fear extinction learning. Transl Psychiatry. (2015) 5:e634. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.138

Keywords: MDMA, LSD, microdosing, chronic pain, limited medical use, psychedelic-assisted therapy

Citation: Gasser P, Liechti ME and Holze F (2025) Treatment of neuropathic pain with repeated low-dose MDMA: a case report. Front. Psychiatry 16:1513022. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1513022

Received: 17 October 2024; Accepted: 10 January 2025;

Published: 03 February 2025.

Edited by:

Marcus Herdener, University of Zurich, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Winston De La Haye, University of the West Indies, Mona, JamaicaJacopo Sapienza, San Raffaele Scientific Institute (IRCCS), Italy

Copyright © 2025 Gasser, Liechti and Holze. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peter Gasser, cGdhc3NlckBnbXgubmV0

Peter Gasser

Peter Gasser Matthias E. Liechti

Matthias E. Liechti Friederike Holze

Friederike Holze