94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 17 March 2025

Sec. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Rehabilitation

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1511841

Astrid M. Kamperman1*

Astrid M. Kamperman1* Milan Zarchev1

Milan Zarchev1 Jens Henrichs2,3,4,5

Jens Henrichs2,3,4,5 Sten P. Willemsen6,7

Sten P. Willemsen6,7 Emmanuel M. E. H. Lesaffre8

Emmanuel M. E. H. Lesaffre8 Wilma E. Swildens9,10

Wilma E. Swildens9,10 Yolanda Nijssen11,12

Yolanda Nijssen11,12 Hans Kroon13,14

Hans Kroon13,14 Anneke D. J. F. van Schaik4,15,16

Anneke D. J. F. van Schaik4,15,16 Mark van der Gaag11,17

Mark van der Gaag11,17 Philippe A. E. G. Delespaul18,19

Philippe A. E. G. Delespaul18,19 Jaap van Weeghel13

Jaap van Weeghel13 Dike van de Mheen13

Dike van de Mheen13 Stefan Bogaerts20,21

Stefan Bogaerts20,21 Cornelis Lambert Mulder1,11

Cornelis Lambert Mulder1,11Objective: To examine determinants of the prevalence and frequency of criminal victimization (i.e. both personal and property crime victimization) in outpatients with severe mental illness.

Methods: Data was collected using a multisite epidemiological survey including a random sample of 956 adult outpatients with SMI. Data were collected between 2010 and 2012. Data on 12-month victimization prevalence and frequency were obtained using the victimization scale of the Dutch Crime and Victimization Survey. Demographic characteristics, clinical determinants, e.g., clinical diagnosis, psychosocial functioning, drug use and alcohol abuse over the past 12 months, co-morbid PTSD diagnosis, and victimological determinants e.g. physical abuse, physical neglect and sexual abuse in childhood, perpetration of violence over the past 12-months, and anger disposition were assessed as determinants. Univariable and multivariable hurdle regression analyses were conducted to test associations of the potential determinants with victimization prevalence and frequency.

Results: Twelve-month prevalence rates of personal and property crime were 19% and 28%, respectively. Clinical characteristics were more pronounced regarding personal crime victimization. In the multivariable model, presence of psychotic disorder, drug use, childhood physical and sexual abuse, and recent violent perpetration were associated with the 12-month prevalence or frequency rate of personal crime victimization. Native Dutch and divorced patients were more at risk as well. Next to this being employed, poor social functioning, having perpetrated a violent crime, as well as alcohol abuse and recent drug use were all significantly related to property crime prevalence or frequency rate in the multivariable model. In absolute terms, the effect sizes observed tended to be moderate to small. The multivariate models, however, explained the outcome variance moderately well (Nagelkerke’s pseudo R2 = 25.0 - 27.9%.

Conclusions: Clinicians should be aware of the high risk of victimization among their patients with severe mental illness. Particular attention should be devoted to people with substance use histories and perpetrators of violence, since they are also at an increased risk of being victims as well.

Outpatients with severe mental illness (SMI), including bipolar, depressive or psychotic disorders, have a higher risk of falling victim to a crime than the general population (1–3).

As an example, a randomized survey in Chicago (n = 936) demonstrated that adult outpatients with SMI had an 11-times higher prevalence of personal crime victimization compared to the general population (3). Crime victimization refers to the involuntary exposure of criminal acts which can be distinguished in two categories: (a) personal crime, which includes victimization events assault, battery, and rape; and (b) property crime which results in theft, larceny or burglary of belongings (3, 4).

Crime victimization is associated with psychopathology (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychotic disorders, anxiety and substance abuse), stigmatization and perpetration of violence (1, 5–9). Moreover, victimization among psychiatric patients is related to exacerbation of existing mental problems, increased service use of health services and suboptimal treatment results (9–11). These figures are alarming and raise the urgent question of identifying risk factors of crime victimization. Risk factors can be broadly categorized as sociodemographic (e.g. the victim’s sex, housing, or socio-economic status), clinical (e.g. mental health problems, drug and alcohol abuse, or social functioning) and victimological (e.g. childhood neglect or abuse, crime perpetration) (3). Such information is crucial, because it can be used for the development or fine-tuning of prevention and intervention programs to address (re-)victimization of outpatients with SMI and its consequences.

Deinstitutionalization of psychiatric care may be a key factor in the increase of reported crime victimization among patients with SMI. Although, compared to the US, deinstitutionalization has been less drastic in European countries, such as the Netherlands (12–14), the majority of the Dutch SMI patients now receive less care from 24-hour hospital services and are instead living in the community. Among persons with SMI, deinstitutionalization may have potentially increased the rates of homelessness, which constitutes an important risk factor of victimization (15–20). As persons with SMI are more often confronted with other adverse conditions (e.g., unemployment, poverty, being a member of an ethnic minority, and conflict prone relationships) these factors may also constitute additional high-risks for victimization (21–23). It is unknown, however, whether victimization has genuinely increased in numbers or instead spilled outside institutional care where crime incidents could be neglected and thus have remained unreported (24). In addition, because of psychiatric problems, including substance abuse, poor reality testing and judgment, reduced social skills as well as impaired emotional regulation, persons with SMI are likely targets to be at an increased risk of victimization (25–29). Finally, persons with SMI have often experienced violent, sexual and/or emotional victimization in childhood, which may make them more vulnerable for victimization in adulthood due to learned helplessness (30–33).

The above lines of research suggest that various socio-demographic adversities, psychiatric problems, and childhood experiences of victimization may contribute to the increased risk of crime victimization among adult outpatients with SMI. However, systematic research simultaneously studying multiple risk factors of crime victimization among outpatients with SMI based on large-scale representative samples is lacking. Some previous studies have looked at specific clinical predictors of victimization for people with SMI, such as the duration and severity of illness, hospitalizations and history of trauma (3, 35). No studies so far have offered a broad perspective on how broader risk factors coalesce to increase the risk of victimization. This leaves an important research gap for holistically identifying systems of risk factors which predict victimization using a multivariable approach.

The current study is a nation-wide randomized multi-site epidemiological survey on victimization among SMI outpatients in the Netherlands. It is the first nationwide multi-site epidemiological study in Europe on assessing both the 12-month prevalence and 12-month frequency rates of crime victimization among adult outpatients with SMI. It includes additional information on various potential criminal victimization, In the current study we aim to estimate the impact of potential demographic, clinical, and victimological determinants on crime victimization prevalence and frequency. We differentiate between personal and property crimes.

The current study is embedded in the Victimization in Psychiatric Patients (ViPP) study, a cross-sectional epidemiological survey of a large random community sample of 956 patients with SMI in the Netherlands (36). Participants were randomly selected from the caseload of six Mental Health Care (MHC) organizations in the Netherlands providing outpatient care to patients suffering from SMI. The organizations are located in both urban and rural areas of the Netherlands and provide care to a range of 240 to 2000 patients with chronic psychotic, bipolar or major depressive disorders. The patient populations at the participating MHC organizations are representative of the SMI patient population in the Netherlands (37–39). Participants were enrolled between December 2010 and April 2012. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus MC, Rotterdam (MEC-2010-232) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Dutch Act of Medical Research involving Humans (WMO Act).

Eligible for the study were all people aged between 18 and 65, being outpatients of one out of six of the participating MHC organizations. A random sample of 3336 eligible outpatients was selected from the patient administration system of each participating site. In- and exclusion criteria were checked by the treating clinician. Excluded were patients with insufficient command of the Dutch language. Those incarcerated in prison or admitted to an acute hospital service and unable to answer study questions due to their psychiatric condition (severe symptomatology, psycho-organic disorders, high levels of aggression or cognitive impairments) were also excluded. This resulted in a sample of 2572 eligible patients who received an invitation letter, and were subsequently contacted by the research team. After signing informed consent the patient was included in the study. Full details on the recruitment has been published previously (36). Flowchart of the recruitment process can be found in the Appendix Figure A (S1).

Data on crime victimization and determinants were obtained in a structured, computer-assisted face-to-face interview. Respondents were paid 20 Euro in cash at the end of the interview. The patient’s interview took 75 minutes on average (range: 40-160 minutes) and was carried out at the respondent’s discretion in his or her home or at the MHC organization.

Data on crime victimization and determinants of crime victimization were collected by interviewers who were master’s level social scientists, e.g., psychologists and sociologists. These interviewers were trained in conducting the structured computer-assisted interview, and in interviewing skills adapted to persons with SMI by senior researchers experienced with the study research population and an actor. An experienced interview coordinator with a master’s level in social science in collaboration with the researchers (AMK, JH) supervised the interviewers and monitored the quality of the interviews.

Twelve-month prevalence of crime victimization and the number of incidents were assessed using the crime victimization scale of the Dutch Crime and Victimization Survey [in Dutch: ‘Integrale Veiligheidsmonitor’(IVM)] (40). The IVM crime victimization scale strongly resembles the International Crime Victimization Survey (41). The IVM consists of 14 screening questions on various types of property crime, personal crime and vandalism. For each reported incident in the preceding 12 months detailed information on the time and number of incidents, setting and perpetrator was assessed. To minimalize the effect of telescoping, the respondents were asked to recall incidents over the past five years, before recalling incidents over the past 12 months (4, 40).

The IVM assessed the following crime victimization categories: Personal crime victimization consisting of sexual harassment or assault, being threatened with violence, and threatened with physical assault; Property crime consisting of burglary, attempted burglary, bike theft, pick-pocketing, robbery, and theft (other). The total crime category consists of burglary, attempted burglary, bicycle theft, pick-pocketing, robbery, theft, vandalism (other), sexual harassment or assault, threatened with violence, physical assault, and crime (other). Since car ownership has low prevalence in the current sample (42), car-related crimes (car theft, theft from car and vandalism of car; n = 5 crime thefts in the current sample) are included in the crime categories used for sensitivity analysis only.

Socio- demographic characteristics included gender, age, ethnicity, marital and employment status, educational level, housing status, and urbanicity. Following the definition of the Dutch government (43) ethnicity was classified on the basis of country of birth and his/her parents’ country of birth. If the parents were born in different countries, the mother’s country of birth prevails. Information about the population density on a postal code level for 2010 was obtained from the national bureau of statistics and matched to each participants. All other information was obtained via the interview.

The primary psychiatric diagnosis, i.e., psychotic, bipolar or major depressive disorder was extracted from the electronic patient files (EPF). Commonly this is a diagnosis set by the psychiatrist or clinical psychologist at the start of the treatment/intake, and updated by the primary clinician. Diagnosis extracted from the EPF were cross-checked by the primary clinician at the start of the study.

Psychosocial functioning was assessed using the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) (44), an observational instrument. The HoNOS consists of 12 items, covering a range of health and social domains, i.e. overactive, aggressive or agitated behavior; non-accidental self-injury; problem drinking or drug taking; cognitive problems; physical illness or disability; problems associated with hallucinations and delusions; problems with depressed mood; other mental and behavioral problems; problems with relationships; problems with activities of daily living; problems with living conditions; problems with occupation and activities. The items are scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from ‘no problem’ to ‘(very) severe problem’. In accordance with HoNOS instruction, the rating was based on all information available to the rater and was related to the most severe problem that occurred during the period rated (usually the two weeks leading up to the point of rating). HoNOS questionnaires were scored by the primary clinician, and shared with the research team. The reliability of the HoNOS in a Dutch population was sufficient (Cronbach α =0.78), and so were divergent and concurrent validity (45). The cut-off score of 9 or higher was used to dichotomize the total score in two categories: mild problems and moderate to severe problems in psychosocial functioning (45, 46), which coincide with the median score in this sample.

Substance abuse was assessed using the Dutch version of the 12-month drug and alcohol use questionnaire of the European Monitoring Centre for drugs and Drugs Addiction (EMCDDA) (47). Regarding alcohol use, frequency and quantity were assessed. For this study, we operationalized alcohol abuse as at least one episode of heavy drinking or binge drinking (e.g. more than 6 consumptions at one occasion) during the past 6 months in line with the definitions used by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization (48, 49). With regard to drug use, type and recency were assessed. Drugs use was operationalized as using one or more types of drugs, or using medication without a doctor’s prescription.

Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were assessed using the Self-Rating Inventory for Posttraumatic stress Disorder (SRIPD) (50). The questionnaire consisted of 22 items, reflecting the 17 PTSD symptoms according to DSM-IV. The items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘no problem’ to ‘very severe problem’. A score above 52 points was interpreted as the presence of PTSD (50, 51). Sensitivity was estimated as 86% and specificity was 71%. Reliability is good (Cronbach α ranges from 0.90 to 0.94); construct validity is satisfactory (50).

Childhood victimization was assessed using three scales of the short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (52). The CTQ is a tool to detect histories of maltreatment. Items on the CTQ assessed experiences in childhood and adolescence which were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from ‘never true’ to ‘very often true’. The subscales physical abuse (5 items), physical neglect (5 items), and sexual abuse (5 items) were included in this study. Psychometric research showed that the construct and criterion-related validity of the CTQ was satisfactory; test-retest reliability of the CTQ subscales ranged from.79 to.86, and internal consistency coefficients ranged from.66 to.92 (52). The scores on the subscales were dichotomized in ‘no experiences’, and ‘one or more experiences’.

Perpetration of physical violence over the past 12-months was assessed by the physical assault subscale (12 items) of the Conflict Tactics Scale short form (CTV2) (53). The items assessed mild and severe experiences of violent perpetration and were answered on a 6-point scale with response options ranging from ‘once a year’ to ‘more than 20 times a year’. Response options for ‘never happened’, and ‘did not happen in the past year, but it did happen before’, were also included. The score was dichotomized in ‘no experiences’, and ‘one or more experiences’.

The Dimensions of Anger Reactions scale (DAR) (54) was used to assess trait anger. The DAR consisted of seven items. The scale assessed anger, frequency, intensity, duration, antagonistic expression, and impairment of work performance, interpersonal relationships, and personal health. In the Dutch version, the items were scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 ‘not at all’ to 4’very much’ (55). Higher scores reflected higher dispositional anger. Test-retest reliability in a Dutch population was good (r=0.84); construct validity was satisfactory (55). Internal consistency was good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79). The score was dichotomized into a low and a high dispositional anger category using a score of 12 as the cut-off point (56).

Hurdle regression analyses were conducted to separately estimate the effects of factors associated with victimization prevalence and victimization frequency over the previous 12 months (57). This model is estimated using logistic regression to model the dichotomous outcome (any vs no victimization incident, i.e., the zero component), and a zero-truncated negative binomial regression for the count outcome (the number of victimization incidents i.e., the count component). Separate models were estimated for personal crime and for property crime victimization outcomes. We used R software (version 4.02) (58) and made use of the ‘pscl’ package (59, 60) for estimating the parameters of the hurdle models.

We first assessed the univariable impact of all determinants on victimization. Second, we entered all determinants into a multivariable model (full model), regardless of the univariable significance obtained in the first step. Next, we excluded variables based on two rules: a significant Likelihood Ratio-test of the reduced model fit at the 5% level and a lack of coefficient change (Δ β >20%) for any of the main determinants (gender, urbanicity and level of psychosocial functioning). We started from least to most significant variable in the full-model (61). The main determinants remained in the model, irrespective of significance or coefficient change. In a last step, the final reduced model was re-estimated using the Sandwich estimation method as implemented in the ‘Sandwich’ package1 (62). Continuous determinants were dichotomized to improve interpretation of the coefficients. We report on Nagelkerke’s pseudo-R2 as a measure of effect size and use contemporary rules of thumbs to interpret its magnitude (63).

Seven variables accounted for missing data: urbanicity (n=2; 0.5% of cases), alcohol abuse (n=10; 1.0% of cases), dispositional anger (n=10; 1.0% of cases), co-morbid PTSD (n=11; 1.2% of cases), perpetration of violence (n=13; 1.4% of cases), housing (n=29; 3.0% of cases), psychosocial functioning (n=260; 27% of cases).Missing values were imputed under the assumption of missing at random using a multiple imputation (five imputed datasets) as implemented in the ‘mice’ package (64). We report on pooled estimates, calculated using the ‘mitools’ package (65, 66).

Multicollinearity between determinant variables was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF>2.0) as implemented in the ‘car’ package (67) and none were found to be above the threshold. Seven cases (0.7% of the total sample) were identified as outliers, reporting extremely high numbers of incidents (>65 incidents), and were removed additionally from the analyses on determinants of victimization frequency. With regards to the other socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, we observed strong similarities between the outlying and the non-outlying cases (see Table 1 and Appendix Table B (S2)).

The full sample consisted of 956 SMI patients: 608 men (64%) and 348 women (36%). Mean (M) age was 44.7 year (Standard Deviation (SD)=10.4). The majority of respondents (61%) had Dutch ethnicity. Educational level was categorized into no/primary education (23%), basic vocational education (34%), intermediate vocational or preparatory academic education (28%), and high vocational or academic education (15%). While most patients were receiving social welfare (86%), 14% were employed (in regular and/or sheltered employment). Psychotic disorder was present in 77% of the cases. Alcohol abuse and/or drug use was present in a quarter of the respondents. The respondents’ demographic and clinical characteristics were consistent with nationwide figures for SMI patients in the Netherlands (38, 39, 68) and thus representative of our target population. Full sample, outliers, and sample characteristics before and after imputation are described in Table 1. The outliers were mostly men living in urban conditions. The imputed covariates did not substantially differ from the original data on any of the determinants. The results presented below were based on the imputed sample.

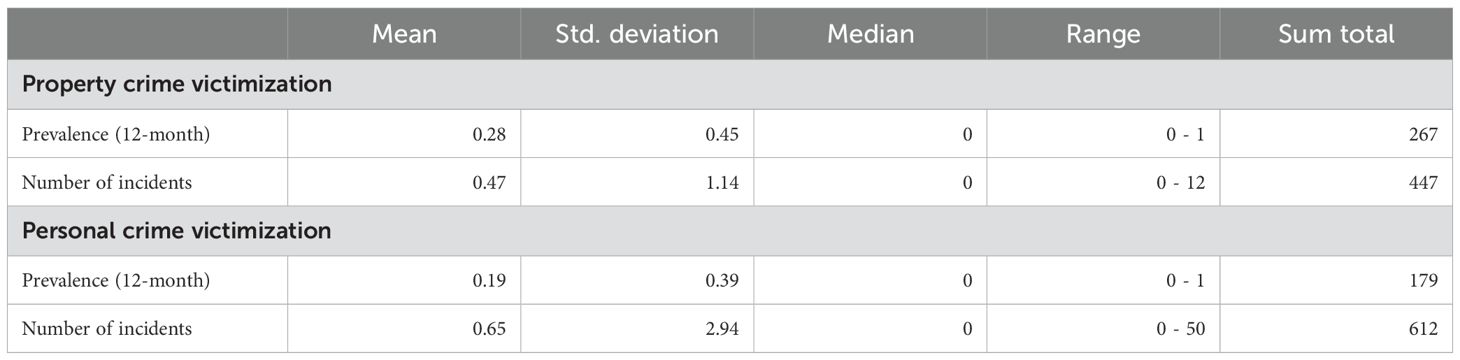

Table 2 shows twelve-month prevalence of personal and property crime victimization was 19% and 28%, respectively. These participants reported a total of 612 personal crimes (M=0.65; SD 2.94) and 447 property crimes (M= 0.47; SD 1.14).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for 12-month prevalences and number of incidents in the current sample after removing the identified outliers (n = 7).

Figures 1, 2, and Appendix Tables C, D (S3, S4) show the determinants of personal crime victimization and property crime victimization, based on an univariable and multivariable analyses in the imputed sample from which outliers were removed. Results regarding personal and property crime are described in the following paragraphs. Results regarding total criminal victimization (personal and property crime combined) are described in Appendix Table E and Appendix Figure F (S5, S6).

The age categories 31-40 yr. and 41-50 yr. were significantly associated with higher prevalence of personal criminal victimization compared to the oldest age category (Odds Ratio (OR)31-40yr: 1.95; 95%Confidence Interval (CI)31-40yr: 1.25-3.03; OR41-50yr: 1.59; 95%CI41-50yr: 1.04-2.44). Ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status, housing, and urbanicity did not show any significant univariable association with personal crime victimization.

Patients diagnosed with a mood disorder were more often a victim of personal crime than patients with psychotic disorders (OR: 0.68; 95%CI: 0.47-0.99). Patients with poor psychosocial functioning had a two times higher prevalence rate than patients with better levels of social functioning (OR: 2.01; 95%CI: 1.31-3.11). Both alcohol abuse (OR: 1.67; 95%CI: 1.18-2.36) and drug use (OR: 2.51; 95%CI: 1.78-3.53) were associated with higher prevalence of personal victimization. Physical and sexual abuse during childhood were also associated with over two times higher prevalence rates of personal victimization (ORphysical: 2.11; 95%CIphysical: 1.52-2.92; ORsexual: 2.17; 95%CIsexual: 1.56-3.03). Violent perpetration was associated with a threefold higher prevalence (OR: 3.12; 95%CI: 2.19-4.44). Finally, patients with high levels of dispositional anger showed an increased risk for personal victimization (OR: 1.72; 95%CI: 1.23-2.41). Co-morbid PTSD and childhood neglect were not significantly associated with personal crime victimization.

In the multivariable logistic model, and based on the sandwich estimator, all demographic and clinical determinants proved important, e.g. removal proved to change remaining coefficients to change >20%.

The impact of most univariable clinical determinants was confirmed in the final multivariable logistic model. Patients with poor psychosocial functioning were more likely to become victim of personal crime (OR: 1.72; 95%CIS: 1.08-2.75). Additionally, drug use remained a significant determinant for personal crime (OR: 1.95; 95%CIS: 1.29-2.94). Prevalence rates for victims of childhood physical abuse (OR: 1.57; 95%CIS: 1.08-2.28) or childhood sexual abuse (OR: 1.76; 95%CIS: 1.19-2.61) were increased, as well as prevalence rates for violent perpetrators (OR: 2.41; 95%CIS: 1.62-3.59). The patient’s diagnosis, alcohol abuse, or dispositional anger no longer showed a significant impact on personal victimization risk in the multivariable logistic model. The final multivariable model explained a moderate 25.0% of the variance of personal crime victimization.

Dutch native patients did not show a higher risk of being victimized, but those who were victimized reported two times more incidents than non-native patients (Incident Rate Ratio (IRR): 1.97; 95%CI: 1.08-3.59). Divorced or widowed reported four times more incidents than patients in a committed relationship (IRR: 0.25; 95%CI: 0.10-0.64), as well as single patients (IRR: 0.26; 95%CI: 0.12-0.60). Patients victimized living in sheltered housing with other patients showed more than twofold more incidents (IRR: 2.14; 95%CI: 1.02-4.48) than patients living in single-person households. None of the other demographic or clinical determinants showed an impact on the number of personal crime incidents experienced by a victim.

In the multivariable hurdle model, the impact of Dutch ethnicity on the frequency of personal crime victimization became more pronounced (IRR: 3.56; 95%CIS: 1.10-10.20). Similar effects were shown with regard to the decreased risk of single patients (IRR: 0.14; 95%CIS: 0.03-0.68) and patients in a committed relationship (IRR: 0.11; 95%CIS: 0.02-0.54) compared to divorced and widowed patients.

Two of the clinical determinants were found to be related to higher numbers of incidents in victims in the multivariable hurdle model. The number of incidents was more than three times higher for patients diagnosed with a psychotic disorder (IRR: 3.36; 95%CIS: 1.26-8.96) than for patients diagnosed with a mood disorder. Drug use was a significant determinant for personal crime frequency, showing almost four times more incidents in victims that used drugs (IRR: 3.85; 95%CI: 1.07-13.88).

Of the socio-demographic characteristics, younger age categories were significantly associated with higher prevalence of property criminal victimization compared to the oldest age category (OR18-30yr: 2.33; 95%CI18-30yr: 1.45-3.77; OR31-40yr: 1.56; 95%CI31-40yr: 1.06-2.30). Property crime victimization was almost two times more common among patients with low educational levels than among those with high vocational or academic educational levels (OR: 0.57; 95%CI: 0.34-0.96). Patients living in sheltered housing showed a more than 1.5-fold higher prevalence (OR: 1.56; 95%CI: 1.09-2.23) than patients living in a single household. Gender, ethnicity, marital status, employment status, and urbanicity did not show any univariable significant association with the prevalence of property crime victimization.

Patients with poor psychosocial functioning had almost two times higher prevalence rates than patients with better levels of social functioning (OR: 1.881; 95%CI: 1.28-2.74). Alcohol abuse (OR: 1.81; 95%CI: 1.33-2.47) and drug use (OR: 2.44; 95%CI: 1.80-3.33) were associated with a doubling of the risk of property crime victimization. Patients with co-morbid PTSD also reported more often to be a victim of property crime (OR: 1.52: 95%CI: 1.07-2.15). Patients who had experienced physical abuse during childhood were also more likely to become victim of property crime (OR: 1.38; 95%CI: 1.04-1.84). Violent perpetration was associated with a twofold higher prevalence (OR: 2.15; 95%CI: 1.56-2.98). Finally, patients with high levels of dispositional anger showed a higher risk for property victimization (OR: 1.50; 95%CI: 1.12-2.00). The patient’s diagnosis, childhood neglect and childhood sexual abuse were not significantly associated with the prevalence of property crime victimization.

In the multivariable logistic model, all demographic and clinical factors were kept in the model. Either they contributed to the overall fit of the model or their removal resulted in a >20% change of the coefficients of the main determinants. Gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, educational level, housing and urbanicity did not show significant associations with property crime prevalence in the full logistic model. Only employment status was significantly related to an increased risk of property crime victimization in the full logistic model. Patients with a paid job had a higher risk of property crime victimization (OR: 1.64; 95%CIs: 1.06-2.53).

With respect to the clinical determinants, co-morbid PTSD, childhood neglect, childhood physical abuse, and dispositional anger were no longer associated with property crime prevalence in the multivariable logistic model. Patients with poor psychosocial functioning had a higher risk for property crime victimization (OR: 1.57; 95%CIs:1.03-2.38). Additionally, patients with alcohol abuse (OR: 1.54; 95%CIs: 1.07-2.24) and drug use (OR: 1.79; 95%CIs: 1.25-2.56) showed higher risks for property crime victimization. Finally, patients who had committed a violent crime over the past year, also had a higher risk to fall victim to a property crime (OR: 1.66; 95% CIs: 1.15-2.39).

The number of property crime incidents for those who had fallen/were victim, was significantly higher for divorced or widowed patients than for lower for married patients (IRR: 0.39; 95%CI: 0.17-0.62). In line with that finding patients living in a single household reported more incidents (IRR: 0.43; 95%CI: 0.20-0.95), than patients living in a family household. None, of the other demographic characteristics were found to be related to the frequency rate of property crime in the univariable analysis.

Patients with co-morbid PTSD, survivors of childhood neglect or childhood physical abuse reported approximately twice the number of property victimization incidents (IRRptsd: 1.79; 95%CIptsd: 1.01-3.19; IRRneglect: 2.19; 95%CIneglect: 1.24-3.88; IRRphysical abuse: 2.38; 95%CIphysical abuse: 1.42-1.98. Additionally, victims of property crime that showed high levels of dispositional anger, experienced more incidents (IRR: 1.70; 95%CI: 1.01-2.87).

In the multivariable hurdle model and based on sandwich estimation, none of the individual demographic or clinical characteristics were significantly associated with the number of incidents a victim experienced property crime. The variance explained by the final model was a moderate 27.9% as measured by Nagelkerke’s pseudo-R2.

By means of sensitivity analyses, all property crime models were refitted with car-related property crime included. Results show a more pronounced impact of poor social functioning and drug use and less pronounced impact of employment (Δ β > 5%), while the impact of alcohol abuse and violent perpetration remained unaffected by the inclusion this type of property crime (see Appendix Table G (S7)).

We found high prevalence of personal and property victimization in outpatients with severe mental illness, as well as several predictive determinants.

Determinants differed across crime categories, suggesting that pathways to victimization differ for personal and property crime incidents. For personal crime victimization, we found a profound impact, often both on prevalence and frequency rate of clinical determinants and childhood trauma. Higher frequency rates were found for victims with psychotic disorder. A higher prevalence risk was found among those with lower levels of psychosocial functioning and current alcohol abuse, defined as occasional excessive drinking, or drug use. In case of drug use, the number of incidents of personal crime victimization was four times higher, while alcohol abuse was related to an almost two times higher risk for this type of victimization. The risk of being personally victimized was also higher for those with a history of childhood physical and sexual trauma. Perpetrators of violence were at double odds of becoming a personal crime victim and having twice as many incidents than other non-perpetrator victims. Dutch and divorced victims experienced three to four times more incidents than non-native, married or single victims. The models explained a moderate amount of variance in crime victimization.

Turning to property crime, becoming a victim of this category was more common among younger patients, and patients with paid employment. In contrast to single-person households, patients living with others in sheltered housing had a higher risk of becoming victims of property crime. Elevated prevalence of property victimization was also associated with lower levels of social functioning, alcohol abuse, and drug use. Finally, violent perpetration indicated an increased risk of becoming a victim. Victims of childhood physical abuse were equally vulnerable to become a victim of property crime as patients without these childhood experiences. However, the number of property crime incidents reported by these victims was doubled. Although the frequencies were elevated for a variety of clinical factors, in a multivariable hurdle model most of these determinants lost their statistical significance.

Previous studies found increased victimization risk for women in the general population and female patients (2, 35, 69). However, these previous studies often estimated associations with gender using univariable models (70, 71). In the current study we did not find women to be at an increased risk for personal or property crime. A gender difference emerged only when looking at a combined category of total crime. The gender effect therefore was not a particularly robust one in the present analysis. Additionally, it has been previously reported that among SMI patients gender differences related to victimization are less profound, and it has even been suggested that the presence of SMI impacts men more than women (36). The increased vulnerability of divorced patients was shown in earlier studies as well (21, 23, 28). Our results showed that this vulnerability relates to both the number of patients being victimized, as well as the number of incidents experienced. We suggest that in many of these cases victimization could take place during or in the aftermath of the divorce, or in the context of co-parenting (72).

Living in sheltered housing was found to be a potential risk factor especially for property crime victimization, impacting both prevalence and frequency rates. This is particularly poignant since sheltered living is supposed to protect and facilitate recovery of vulnerable patients (73). The elevated risk of shared sheltered housing, in contrast to single housing, remained significant after adjusting for socio-demographic and a variety of clinical characteristics, suggesting that mechanisms unique to those housing arrangements pose an independent risk for its inhabitants. The downsides of sheltered housing have been described before, however often in the context of qualitative studies (73–76).

We found consistent and strong associations between violent perpetration and victimization. This interrelationship has been documented previously (1, 21, 35, 77), and so has been the impact of childhood trauma (22, 78). For both personal as well as property crime victimization, we found a strong and consistent association with an overall lower level of functioning (more symptoms, more impairments, problems with substance use) in victims. In the multivariable hurdle model these factors, which suggest a heightened level of psychopathology, remained relevant. However, when including a more robust form of parameter estimation, the coefficients lost significance in favor to the factors indicating a risk-taking lifestyle.

Although documented previously, and strongly connected with the cycle of violence paradigm, we did not find co-morbid PTSD diagnosis to be an important determinant for personal crime victimization (22, 67, 75, 79). We speculate that within the subgroup of SMI patients, PTSD symptomatology is closely interwoven with the overall level of psychopathology and therefore cannot show the same discriminant value it has in less affected samples.

The most prominent strengths of this study were its large sample size, random sampling method and high response rate offering a unique perspective on victimization based on an hard to reach SMI population in Europe. The sample size allowed us to reliably estimate small to medium sized associations with personal and property crime victimization in the multivariable models. Furthermore, the representative characteristics of our sample offer a strong case for the current results to be generalized on a population level beyond the sample of SMI patients reported here.

We also note several limitations of the current study. Generally, falling victim to crime, especially falling victim to more severe forms of crime over a 12-month period is considered a rare event. Rare event models are prone to speculative results and over-interpretation. We used hurdle regression models to analyze our rare and overdispersed data. Furthermore, we chose to combine our crime incidents into two categories. In doing so, we found robust determinants of personal and property crime victimization prevalence. However, by modelling categories, we lost the ability to distinguish unique determinants for unique crime incidents and we might have lost power to detect more modest associations (80). This might have limited the usefulness of our models with regard to more rare crime incidents, such as sexual assault. The estimations of the determinants of the number of victimization incidents, were less robust. We speculate that this results from the existence of specific (high risk) subpopulations within our sample (34).

Another limitation concerns the use of self-reported data, which is vulnerable to bias. Patients might have over-reported or under-reported their symptoms and use of drugs and alcohol due to unmeasured variables. It is unknown how these divergent possibilities would affect the magnitude and directions of the association reported here. Crime victimization numbers were also based on self-report. However, the IVM questionnaire is developed specifically to avoid recall bias and telescoping (i.e., the tendency to report impactful events closer in more recent history than is true) and considered the golden standard in Dutch crime research (40). Finally, the data was collected between 2010 and 2012, which might have impacted the generalizability of the prevalence and incidence rates, but most likely does not impact the underlying dynamics causing SMI patients to become victims of crime.

We found high annual prevalence rates of personal and property victimization of 19% and 28% respectively. For property crime, we found the strongest determinants in the clinical category, in particular substance abuse and poor social functioning. However, we also found predictive associations among the victimological determinants (i.e. being a perpetrator of violence) and the sociodemographic determinants (i.e. being unemployed). For personal crime, clinical determinants, consisting of drug use and poor social, functioning again emerged as the strongest predictors. In the victimological category, perpetration of violence, but also childhood abuse were predictive of personal crime.

This study provides more evidence for clinicians to become more aware of criminal victimization as well as perpetration, since both are prevalent and strongly interrelated. This perpetuation of violence, from childhood into adulthood and between victimization and perpetration incidents, is often described and is referred to as the cycle of violence (79). To break this cycle of violence, we stress the importance of early intervention, starting with the prevention of childhood neglect and abuse, especially because these factors also have an important role in developing adult psychopathology. We speculate that the pathways to personal victimization (e.g., physical and sexual threats and violent acts) are determined more profoundly by this cycle of violence than property victimization (e.g., theft, vandalism) which seems to be impacted more by a risk-taking lifestyle and opportunity (e.g., the presence of valuables). Intervention studies reported that clinicians feel inhibited to discuss these topics with their patients and suggested that less than 10% of the patients are detected as victims by the primary clinician (81–83). Training of clinicians, mandatory screening or AI-supported screening might help overcome the hesitation surrounding crime victimization (84–86).

Considering the high prevalence and frequency, there is a strong need for evidence-based interventions to prevent victimization. Interventions should target specific risk profiles. We distinguished specific risk profiles for personal and property crimes, patients with situational or chronic lifetime risk patterns, risk profiles related to failing coping strategies, as well as profiles related to risk taking and disorganized behavior (87). Once SMI patients have been victimized trauma-focused therapy is safe and effectively reduces effects on psychiatric symptoms and improves social functioning (88, 89). Given the impact of the cycle of violence, we urge early intervention as well as a nuanced perspective on the interrelationship of perpetration and victimhood. We further suggest the staff of sheltered housing to remain alert for crime incidents, monitoring both co-habitants as well as contact from the wider community. Theft and vandalism could be prevented by providing personal lockers or helping inhabitants make sure their doors remain locked.

To conclude, this study underscores the vulnerable position of SMI patients. The high prevalence of crime victimization and the strong interrelationship with violent perpetration among outpatients urges clinicians to engage their patients in discussing the impact of crime and violence in their lives. Overall, the clinical determinants were most important, but the interplay with other demographic and victimological factors stress the importance of a holistic perspective on victimization.

The data is not available due to the sensitive nature of the population under study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to YS5rYW1wZXJtYW5AZXJhc211c21jLm5s.

The studies involving humans were approved by Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus MC, Rotterdam (MEC-2010-232). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

AK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding for this research was received from the Dutch Research Council (NWO; nr: 2010/12072/MaGW).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1511841/full#supplementary-material

1. Choe JY, Teplin LA, Abram KM. Perpetration of violence, violent victimization, and severe mental illness: balancing public health concerns. Psychiatr Serv. (2008) 59:153–64. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.2.153

2. Ruiz-Perez I, Rodriguez-Barranco M, Cervilla JA, Ricci-Cabello I. Intimate partner violence and mental disorders: Co-occurrence and gender differences in a large cross-sectional population based study in Spain. J Affect Disord. (2018) 229:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.032

3. Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Weiner DA. Crime victimization in adults with severe mental illness: comparison with the National Crime Victimization Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2005) 62:911–21. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.911

4. CBS. Integrale veiligheidsmonitor 2008. Landelijke rapportage. Den Haag: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (2009).

5. Burnam MA, Stein JA, Golding JM, Siegel JM, Sorenson SB, Forsythe AB, et al. Sexual assault and mental disorders in a community population. J Consult Clin Psychol. (1988) 56:843–50. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.843

6. Dean K, Moran P, Fahy T, Tyrer P, Leese M, Creed F, et al. Predictors of violent victimization amongst those with psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2007) 116:345–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01078.x

7. Lam JA, Rosenheck R. The effect of victimization on clinical outcomes of homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. (1998) 49:678–83. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.5.678

8. Logan TK, Walker R, Cole J, Leukefeld C. Victimization and substance abuse among women: Contributing factors, interventions, and implications. Rev Gen Psychol. (2002) 6:325–97. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.325

9. Mueser KT, Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Trumbetta SL. Trauma, PTSD, and the course of severe mental illness: an interactive model. Schizophr Res. (2002) 53:123–43. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00173-6

10. Lysaker PH, Meyer PS, Evans JD, Clements CA, Marks KA. Childhood sexual trauma and psychosocial functioning in adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. (2001) 52:1485–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.11.1485

11. Goodman LA, Johnson M, Dutton MA, Harris M. Prevalence and impact of sexual and physical abuse in women with severe mental illness. Amsterdam,Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers (1997).

12. Farkas M, Coe S. From residential care to supportive housing for people with psychiatric disabilities: past, present, and future. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:862. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00862

13. Priebe S, Frottier P, Gaddini A, Kilian R, Lauber C, Martinez-Leal R, et al. Mental health care institutions in nine European countries, 2002 to 2006. Psychiatr Serv. (2008) 59:570–3. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.5.570

14. Tomlin J, Lega I, Braun P, Kennedy HG, Herrando VT, Barroso R, et al. Forensic mental health in Europe: some key figures. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2021) 56:109–17. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01909-6

15. Drake RE, Osher FC, Wallach MA. Homelessness and dual diagnosis. Am Psychol. (1991) 46:1149–58. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.46.11.1149

16. Lamb HR, Bachrach LL. Some perspectives on deinstitutionalization. Psychiatr Serv. (2001) 52:1039–45. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.8.1039

17. North CS, Smith EM, Spitznagel EL. Violence and the homeless: An epidemiologic study of victimization and aggression. J Traumatic Stress. (1994) 7:95–110. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490070110

18. Shlay AB, Rossi PH. Social-science research and contemporary-studies of homelessness. Annu Rev Sociol. (1992) 18:129–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.001021

19. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE. Deinstitutionalization and other factors in the criminalization of persons with serious mental illness and how it is being addressed. CNS Spectrums. (2020) 25:173–80. doi: 10.1017/S1092852919001524

20. Markowitz FE. Mental illness, crime, and violence: Risk, context, and social control. Aggression Violent Behavior. (2011) 16:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2010.10.003

21. Silver E. Mental disorder and violent victimization: the mediating role of involvement in conflicted social relationships. Criminol. (2002) 40:191–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2002.tb00954.x

22. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Borum R, Wagner HR. Criminal victimization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv S2- Hosp Community Psychiatry. (1999) 50:62–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.1.62

23. Krumm S, Checchia C, Kilian R, Becker T. Adult victimization of mental health service users A review of prevalences, risk factors, and disclosure. Psychiatr Prax. (2018) 45:66–77. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-119484

24. Hodgins S, Alderton J, Cree A, Aboud A, Mak T. Aggressive behaviour, victimization and crime among severely mentally ill patients requiring hospitalisation. Br J Psychiatry. (2007) 191:343–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.06.029587

25. Bone CW, Goodfellow AM, Vahidi M, Gelberg L. Prevalence of Sexual Violence and its Association with Depression among Male and Female Patients with Risky Drug Use in Urban Federally Qualified Health Centers. J Urban Health-Bulletin New York Acad Med. (2018) 95:111–5. doi: 10.1007/s11524-017-0213-7

26. Fujii DE, Wylie AM, Nathan JH. Neurocognition and long-term prediction of quality of life in outpatients with severe and persistent mental illness. Schizophr Res. (2004) 69:67–73. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00122-1

27. Gearon JS, Bellack AS. Women with schizophrenia and co-occurring substance use disorders: An increased risk for violent victimization and HIV. Community Ment Health J. (1999) 35:401–19. doi: 10.1023/A:1018778310859

28. Hiday VA. The social context of mental illness and violence. J Health Soc Behav S2- J Health Hum Behavior. (1995) 36:122–37. doi: 10.2307/2137220

29. Sells DJ, Rowe M, Fisk D, Davidson L. Violent victimization of persons with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv S2- Hosp Community Psychiatry. (2003) 54:1253–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.9.1253

30. Goodman LA, Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT, Drake RE. Physical and sexual assault history in women with serious mental illness: Prevalence, correlates, treatment, and future research directions. Schizophr Bull. (1997) 23:685–96. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.4.685

31. Silver E, Piquero AR, Jennings WG, Piquero NL, Leiber M. Assessing the violent offending and violent victimization overlap among discharged psychiatric patients. Law Hum Behav. (2011) 35:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s10979-009-9206-8

32. Pro G, Camplain R, de Heer B, Chief C, Teufel-Shone N. A national epidemiologic profile of physical intimate partner violence, adverse childhood experiences, and supportive childhood relationships: group differences in predicted trends and associations. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. (2020) 7:660–70. doi: 10.1007/s40615-019-00696-4

33. Kmett JA, Eack SM. Characteristics of sexual abuse among individuals with serious mental illnesses. J Interpersonal Violence. (2018) 33:2725–44. doi: 10.1177/0886260516628811

34. Albers WMM, Roeg DPK, Nijssen Y, van Weeghel J, Bongers IMB. Profiling of victimization, perpetration, and participation: A latent class analysis among people with severe mental illness. PloS One. (2018) 13:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208457

35. de Mooij LD, Kikkert M, Lommerse NM, Peen J, Meijwaard SC, Theunissen J, et al. Victimisation in adults with severe mental illness: prevalence and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. (2015) 207:515–22. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.143370

36. Kamperman AM, Henrichs J, Bogaerts S, Lesaffre EMEH, Wierdsma AI, Ghauharali RRR, et al. Criminal victimisation in people with severe mental illness: A multi-site prevalence and incidence survey in the Netherlands. PloS One. (2014) 9:e91029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091029

37. Kortrijk H, Schaefer B, van Weeghel J, Mulder CL, Kamperman A. Trajectories of patients with severe mental illness in two-year contact with Flexible Assertive Community Treatment teams using Routine Outcome Monitoring data: An observational study. PloS One [Electronic Resource]. (2019) 14:e0207680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207680

38. Delespaul PH, de consensusgroep EPA. Consensus regarding the definition of persons with severe mental illness and the number of such persons in the Netherlands] Consensus over de definitie van mensen met een ernstige psychische aandoening (EPA) en hun aantal in Nederland. Tijdschr Psychiatr. (2013) 55:427–38.

39. Djordjevic M, Jongsma HE, Simons CJP, Oomen PP, de Haan L, Boonstra N, et al. Associations between momentary mental states and concurrent social functioning after remission from first episode psychosis: A HAMLETT ecological momentary assessment study. J Psychiatr Res. (2025) 181:560–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.12.002

40. CBS. Integrale Veiligheidsmonitor 2008. Landelijke rapportage. The Hague, The Netherlands: CBS Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (2009).

41. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. Technical background on the redesigned National Crime Victimization Study. Washington, USA: US Bureau of the Census (1994).

42. CBS. Ruim kwart huishoudens heeft geen motorvoertuig: cbs.nl(2018). Available online at: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2018/25/ruim-kwart-huishoudens-heeft-geen-motorvoertuig (Accessed January 09, 2023).

43. Keij I. Numbers of foreigners according to various definitions. Maandstatistiek van Bevolking. (2000) 48:14–7. Available online at: https://www.cbs.nl/-/media/imported/documents/2000/21/b-15-05-00.pdf?la=nl-nl.

44. Wing JK, Beevor AS, Curtis RH, Park SB, Hadden S, Burns A. Health of the nation outcome scales (HoNOS). Res Dev Br J Psychiatry. (1998) 172:11–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.11

45. Mulder CL, Staring ABP, Loos J, Buwalda VJA, Kuijpers D, Sytema S, et al. De Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) als instrument voor ‘routine outcome assessment’. TvP. (2004) 46:273–84. Available online at: https://www.tijdschriftvoorpsychiatrie.nl/media/5/articles_1238pdf.pdf.

46. Parabiaghi A, Kortrijk HE, Mulder CL. Defining multiple criteria for meaningful outcome in routine outcome measurement using the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2014) 49:291–305. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0750-7

47. Van Rooij AJ, Schoenmakers TM, Van de Mheen D. Nationaal Prevalentie Onderzoek Middelengebruik 2009: De kerncijfers [National Prevalence Study on Substance Use 2009: Core Statistics]. Rotterdam: Instituut voor Verslavingsonderzoek (2011).

48. Organization WH. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. (Geneva: World Health Organization) (2018).

49. CDC. Binge Drinking: cdc.gov (2022). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/binge-drinking.htm (Accessed January 09, 2023).

50. Hovens JE, Bramsen I, van der Ploeg HM. Self-rating inventory for posttraumatic stress disorder: review of the psychometric properties of a new brief Dutch screening instrument. Perceptual Motor Skills. (2002) 94:996–1008. doi: 10.2466/pms.2002.94.3.996

51. van Zelst WH, de Beurs E, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Bramsen I, van Dyck R. Criterion validity of the self-rating inventory for posttraumatic stress disorder (SRIP) in the community of older adults. J Affect Disord. (2003) 76:229–35. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00095-2

52. Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. (2003) 27:169–90. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

53. Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. J Family Issues. (1996) 17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001

54. Hawthorne G, Mouthaan J, Forbes D, Novaco RW. Response categories and anger measurement: do fewer categories result in poorer measurement?: development of the DAR5. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2006) 41:164–72. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0986-y

55. Nederlof AF, Hovens JE, Muris P, Novaco RW. Psychometric evaluation of a Dutch version of the Dimensions of Anger Reactions. Psychol Rep. (2009) 105:585–92. doi: 10.2466/PR0.105.2.585-592

56. Forbes D, Alkemade N, Mitchell D, Elhai JD, McHugh T, Bates G, et al. Utility of the Dimensions of Anger Reactions-5 (DAR-5) scale as a brief anger measure. Depress Anxiety. (2014) 31:166–73. doi: 10.1002/da.2014.31.issue-2

57. Mullahy J. Specification and testing of some modified count data models. J Econometrics. (1986) 33:341–65. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(86)90002-3

58. Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2018).

59. Jackman S. pscl: Classes and methods for R developed in the political science computational laboratory. Stanford: Stanford University, Science DoP (2012).

60. Zeileis A, Kleiber C, Jackman S. Regression models for count data in R. J Stat Softw. (2008) 27:1–25. doi: 10.18637/jss.v027.i08

62. Zeileis A. Object-oriented computation of sandwich estimators. J Stat Software. (2006) 16:1–16. doi: 10.18637/jss.v016.i09

63. Bujang MA, Sa’at N, Sidik T, Joo LC. Sample size guidelines for logistic regression from observational studies with large population: emphasis on the accuracy between statistics and parameters based on real life clinical data. Malays J Med Sci. (2018) 25:122–30. doi: 10.21315/mjms2018.25.4.12

64. van Buuren S, Groothius-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. (2011) 45:1–67. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03

65. Lumley T. mitools: Tools for Multiple Imputation of Missing Data. R package version 2.4 (2019). Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mitools.

67. Fox JW. Sanford. an {R} companion to applied regression. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (2011).

68. Kortrijk HE, Mulder CL, Drukker M, Wiersma D, Duivenvoorden HJ. Duration of assertive community treatment and the interpretation of routine outcome data. Aust New Z J Psychiatry. (2012) 46:240–8. doi: 10.1177/0004867411433214

69. Khalifeh H, Moran P, Borschmann R, Dean K, Hart C, Hogg J, et al. Domestic and sexual violence against patients with severe mental illness. Psychol Med. (2015) 45:875–86. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001962

70. Khalifeh H, Johnson S, Howard LM, Borschmann R, Osborn D, Dean K, et al. Violent and non-violent crime against adults with severe mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. (2015) 206:275–82. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147843

71. Khalifeh H, Dean K. Gender and violence against people with severe mental illness. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2010) 22:535–46. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.506185

72. Stolzenberg L, D’Alessio SJ. The effect of divorce on domestic crime. Crime Delinquency. (2007) 53:281–302. doi: 10.1177/0011128705284383

73. Zarchev M, Mulder CL, Henrichs J, Roeg DPK, Bogaerts S, van Weeghel J, et al. Victimisation of individuals with serious mental illness living in sheltered housing: differential impact of risk factors related to clinical and demographic characteristics. BJPsych Open. (2021) 7:e97. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.57

74. McPherson P, Krotofil J, Killaspy H. Mental health supported accommodation services: A systematic review of mental health and psychosocial outcomes. BMC Psychiatry. (2018) 18(1):128. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1725-8

75. Whitley R, Harris M, Drake RE. Safety and security in small-scale recovery housing for people with severe mental illness: An inner-city case study. Psychiatr Serv. (2008) 59:165–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.2.165

76. Gonzalez MT, Andvig E. Experiences of tenants with serious mental illness regarding housing support and contextual issues: A meta-synthesis. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2015) 36:971–88. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1067262

77. Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Feder G, Chung WS, Richardson J, Moorey S. Relation between childhood sexual and physical abuse and risk of revictimisation in women: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. (2001) 358:450–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05622-7

78. Anderson F, Howard L, Dean K, Moran P, Khalifeh H. Childhood maltreatment and adulthood domestic and sexual violence victimisation among people with severe mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2016) 51:961–70. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1244-1

79. Augsburger M, Basler K, Maercker A. Is there a female cycle of violence after exposure to childhood maltreatment? A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. (2019) 49:1776–86. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719000680

80. Zima BT, Bussing R, Bystritsky M, Widawski MH, Belin TR, Benjamin B. Psychosocial stressors among sheltered homeless children: relationship to behavior problems and depressive symptoms. Am J Orthopsychiatry. (1999) 69:127–33. doi: 10.1037/h0080389

81. Ruijne R, Mulder C, Zarchev M, Trevillion K, van Est R, Leeman E, et al. Detection of domestic violence and abuse by community mental health teams using the BRAVE intervention: A multicenter, cluster randomized controlled trial. J Interpersonal Violence. (2022) 37(15–23):1–7. doi: 10.1177/08862605211004177

82. Rose D, Trevillion K, Woodall A, Morgan C, Feder G, Howard LM. Barriers and facilitators of disclosure of domestic violence by mental health service users: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. (2011) 198:189–94. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.072389

83. Trevillion K, Byford S, Carey M, Rose D, Oram S, Feder G, et al. Linking abuse and recovery through advocacy: an observational study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2014) 23:99–113. doi: 10.1017/S2045796013000206

84. Hunt X, Tomlinson M, Sikander S, Skeen S, Marlow M, du Toit S, et al. Artificial intelligence, big data, and mHealth: the frontiers of the prevention of violence against children. Front Artif Intelligence. (2020) 3:543305. doi: 10.3389/frai.2020.543305

85. Menger V, Spruit M, van Est R, Nap E, Scheepers F. Machine learning approach to inpatient violence risk assessment using routinely collected clinical notes in electronic health records. JAMA Netw Open. (2019) 2:e196709. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6709

86. Ruijne RE, Kamperman AM, Trevillion K, Garofalo C, Jongejan FE, Bogaerts S, et al. Mental health professionals’ knowledge, skills and attitudes on domestic violence and abuse in the Netherlands: cross-sectional study. Bjpsych Open. (2019) 5. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.8

87. Albers WMM, Roeg DPK, Nijssen YAM, Deen ML, Bongers IMB, van Weeghel J. Intervention to prevent and manage the effects of victimization related to social participation for people with severe mental illness: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2021) 44:254–65. doi: 10.1037/prj0000449

88. van den Berg DP, de Bont PA, van der Vleugel BM, de Roos C, de Jongh A, Van Minnen A, et al. Prolonged exposure vs eye movement desensitization and reprocessing vs waiting list for posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with a psychotic disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. (2015) 72:259–67. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2637

89. de Bont PA, van den Berg DP, van der Vleugel BM, de Roos C, de Jongh A, van der Gaag M, et al. Prolonged exposure and EMDR for PTSD v. a PTSD waiting-list condition: effects on symptoms of psychosis, depression and social functioning in patients with chronic psychotic disorders. Psychol Med. (2016) 46:2411–21. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001094

Keywords: victimization, violence, crime, determinants, psychiatric patients, epidemiology

Citation: Kamperman AM, Zarchev M, Henrichs J, Willemsen SP, Lesaffre EMEH, Swildens WE, Nijssen Y, Kroon H, van Schaik ADJF, van der Gaag M, Delespaul PAEG, van Weeghel J, van de Mheen D, Bogaerts S and Mulder CL (2025) Determinants of victimization in patients with severe mental illness: results from a nation-wide cross-sectional survey in the Netherlands. Front. Psychiatry 16:1511841. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1511841

Received: 15 October 2024; Accepted: 11 February 2025;

Published: 17 March 2025.

Edited by:

Manuel Trachsel, University of Basel, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Tilman Steinert, ZfP Südwürttemberg, GermanyCopyright © 2025 Kamperman, Zarchev, Henrichs, Willemsen, Lesaffre, Swildens, Nijssen, Kroon, van Schaik, van der Gaag, Delespaul, van Weeghel, van de Mheen, Bogaerts and Mulder. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Astrid M. Kamperman, YS5rYW1wZXJtYW5AZXJhc211c21jLm5s

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.