- 1Department of Acupuncture, Nanjing Hospital of Chinese Medicine Affiliated to Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

- 2The First Clinical Medical College, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

- 3Department of Acupuncture Rehabilitation, Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

Background: The benefits of acupuncture on primary insomnia (PI) have been well established in previous studies. However, different acupuncture dosages may lead to controversy over its efficacy. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between the dose and efficacy of acupuncture for the treatment of PI.

Methods: Seven databases were searched from inception until May 30, 2024. The included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with acupuncture for PI on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores were divided into three categories according to the therapeutic dose of acupuncture (frequency, session, and course): low dosage, medium dosage, and high dosage. The correlation between the dose and the effect of treatment was analyzed. Risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool. Meta-analyses were performed using RevMan v.5.4 and Stata 16.0 software.

Results: A total of 56 studies were included. There were 17 sham acupuncture-controlled RCTs that are notable because of their high quality. Overall, the effect on the reduction of the PSQI scores varied across the different acupuncture dosages. For the frequency of acupuncture, the results showed a significant improvement in the moderate frequency (three sessions per week) and high frequency (five to seven sessions per week) categories. With regard to the acupuncture session, it was shown that moderate session (12–20 sessions) and high session (24–30 sessions) had better effects on the reduction of the PSQI scores, with low session (≤10 sessions) being not significant. For the acupuncture course, there were no differences in the short course (≤2 weeks) and the long course (>4 weeks) between the acupuncture group and the control group. Medium course (3–4 weeks) was considered as the optimal course. In addition, there were no differences between acupuncture and SATV (sham acupuncture therapy at verum points) on the same acupuncture points in the PSQI scores. The results of GRADE assessment demonstrated that the level of evidence was very low to moderate, probably due to the poor methodological quality and the substantial heterogeneity among studies.

Conclusions: A dose–effect relationship was found between the acupuncture dose and the PSQI scores. Although sham acupuncture needling at the same points as those in acupuncture may not be a true placebo control, this was utilized in a minority of studies. Collectively, the data suggest that at least three sessions per week for 3–4 weeks and a total of at least 12 acupuncture sessions would be the optimal clinical response.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/, identifier CRD42024560078.

1 Introduction

Sleep is a vital process, occupying up to a third of the human life span. According to clinical statistics, approximately 25% of people experience unsatisfactory sleep and that 6.0%–10% of individuals meet the diagnostic criteria of insomnia (1). Primary insomnia (PI) is characterized by difficulties in falling asleep and in maintaining sleep and by early morning awakening. It is coupled with daytime consequences such as fatigue, attention deficit, and mood instability. Although insomnia is not a critical disease, long-term insomnia can increase the risk of other physical or mental illnesses or exacerbate existing medical or psychiatric disorders (2, 3). The societal costs of insomnia are substantial. Some studies have shown that poor sleepers cost society approximately 10 times as much as good sleepers (4). Benzodiazepine and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics are recommended for short-term use (maximum 4 weeks), with risks of negative side effects and with limited evidence of their long-term efficacy (5). Although cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the first-line treatment for chronic insomnia, an impediment to its wider utilization is the lack of suitably trained psychologists (6).

Acupuncture has been practiced in China for the prevention and treatment of diseases for thousands of years. Several recently published meta-studies suggested that acupuncture has shown a moderate or large effect in patients with PI when compared with sedative hypnotics alone, control acupuncture (invasive and noninvasive sham controls), and no treatment/waitlist (7, 8). However, these meta-studies have primarily focused on the efficacy of acupuncture and the different acupuncture methods. The adequate acupuncture “dose” with optimal intervention parameters and time table has been overlooked, despite its potential direct impact on trial outcomes. Thus far, there has been no systematic review of the dose–response relationship between acupuncture and its efficacy on PI. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to provide evidence-based recommendations for the dose–response association and the optimal dosage of acupuncture in PI.

2 Materials and methods

The systematic review protocol was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42024560078). The dose–effect meta-analysis was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statements.

2.1 Search strategy

Systematic literature searches of PubMed, The Cochrane Library, Web of Science, EMBASE, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wan Fang Database, China Biology Medicine (CBM), and the VIP Database were performed from the date of database inception to May 25, 2024, for studies on the effects of acupuncture on PI. The search strategy for PubMed is shown in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria followed the PICOS framework, and only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in the Chinese and the English language were included: i) PI must be diagnosed according to at least one internationally or nationally recognized diagnostic criterion; ii) acupuncture was limited to manual acupuncture (MA) and electro-acupuncture (EA); iii) studies that compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture or with a sedative hypnotic drug; and iv) the primary outcome was the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) clinical trials with fewer than 20 participants in either the intervention or the control group and ii) studies employing non-acupuncture techniques or combined methods in the intervention group, such as a combination of acupuncture with medication, massage, or moxibustion.

2.3 Article screening and data extraction

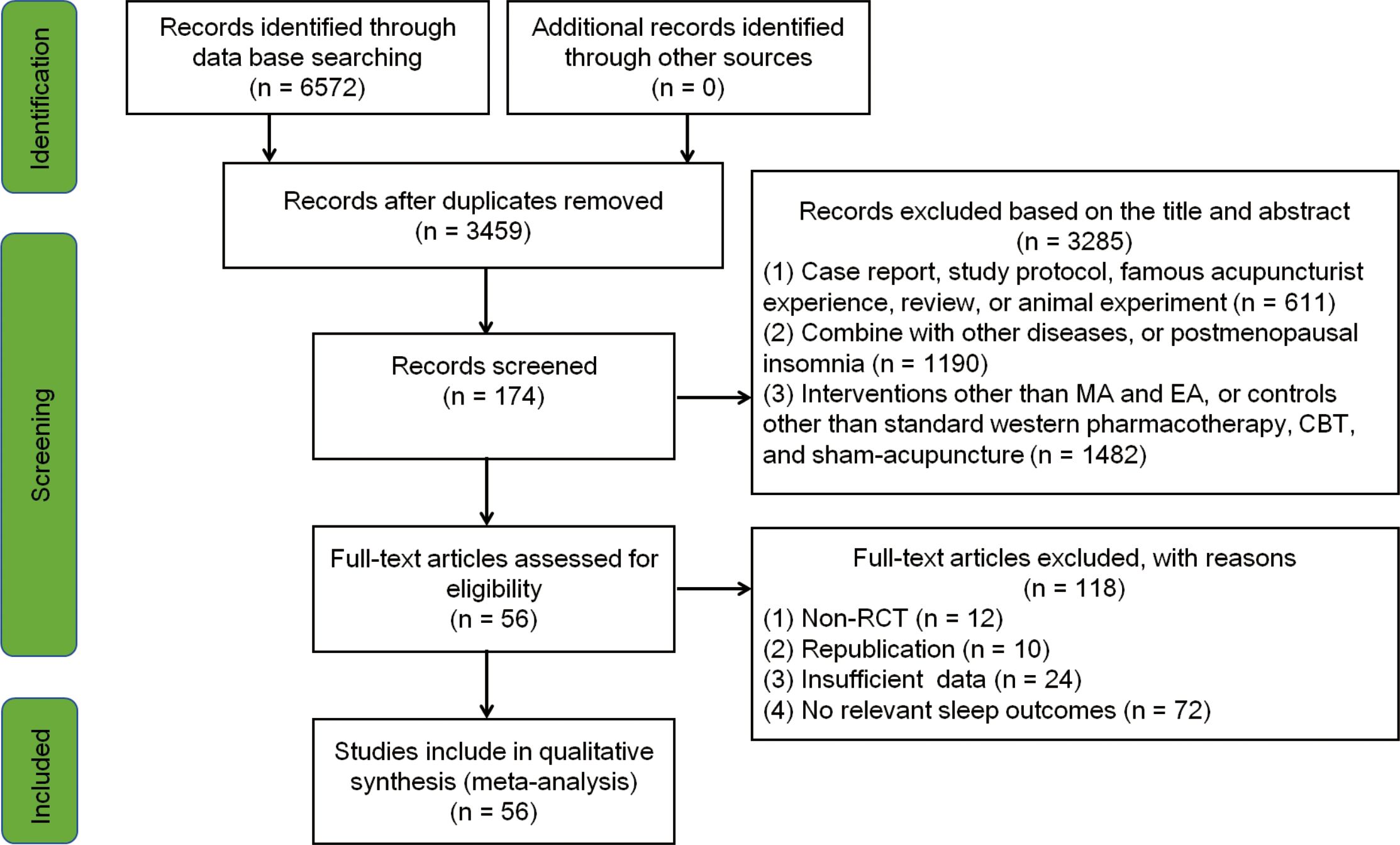

Figure 1 illustrates the process of study selection. Two researchers (XZ and YW) independently selected the studies and collected the data, importing the identified studies into EndNote X9.0. Where disagreements occurred, a third researcher (CL) was consulted to reach a consensus. The following information was retrieved: study characteristics (i.e., author information, publication year, title, and study design); participant details (i.e., age, gender, duration, and diagnosis); method of intervention/control (i.e., number of treatments and frequency); outcomes [e.g., mean and standard deviation (SD) of the PSQI scores and follow-up].

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study search and selection process. CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; EA, electro-acupuncture; MA, manual acupuncture; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

2.4 Risk of bias assessment

Two trained researchers (SQ and LL) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool. For any disagreements, a third reviewer (CD) helped to reach consensus. The evaluations included the following categories: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, completeness of the outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. For each category, the risk of bias was rated as low, high, or unclear.

2.5 Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using RevMan 5.4 and Stata 16.0 software. For continuous variables, the mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence interval (95%CI) was calculated. For dichotomous variables (effective rate), the relative risk (RR) with 95%CI was determined. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity among the RCTs. An I2 >50% indicates heterogeneity, while an I2 <50% was assumed to indicate no heterogeneity. In analyses where p > 0.1 and I2 < 50%, a fixed effects model was applied; otherwise, a random effects model was used. To explore the most suitable or the optimal parameters of acupuncture dose, the included studies were divided into three different groups. For acupuncture frequency, the studies were divided into: low frequency (one to two sessions per week), moderate frequency (three sessions per week), and high frequency (five to seven sessions per week). For acupuncture session, they were classified into: low session (<12 sessions), moderate session (12–20 sessions), and high session (24–30 sessions). According to the course of treatment, the three groups were: short course (≤2 weeks), medium course (3–4 weeks), and long course (>4 weeks). If substantial heterogeneity was detected, subgroup analyses were considered to explore the causes of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were assessed by removing any single study in each group to explore its effect on heterogeneity. Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and Egger’s test when at least 10 studies were included.

2.6 Quality assessment

To assess the certainty of evidence, the GRADEpro online tool (http://gdt.gradepro.org/app#projects) was used to perform the evaluation and followed the recommended procedures for grading (high, moderate, low, or very low).

3 Results

A total of 6,572 articles were initially retrieved from the searches. After removing the duplicates and further screening, 56 RCTs (involving 4,019 participants) were ultimately included in the meta-analyses. The literature screening process is summarized in Figure 1.

3.1 Study characteristics

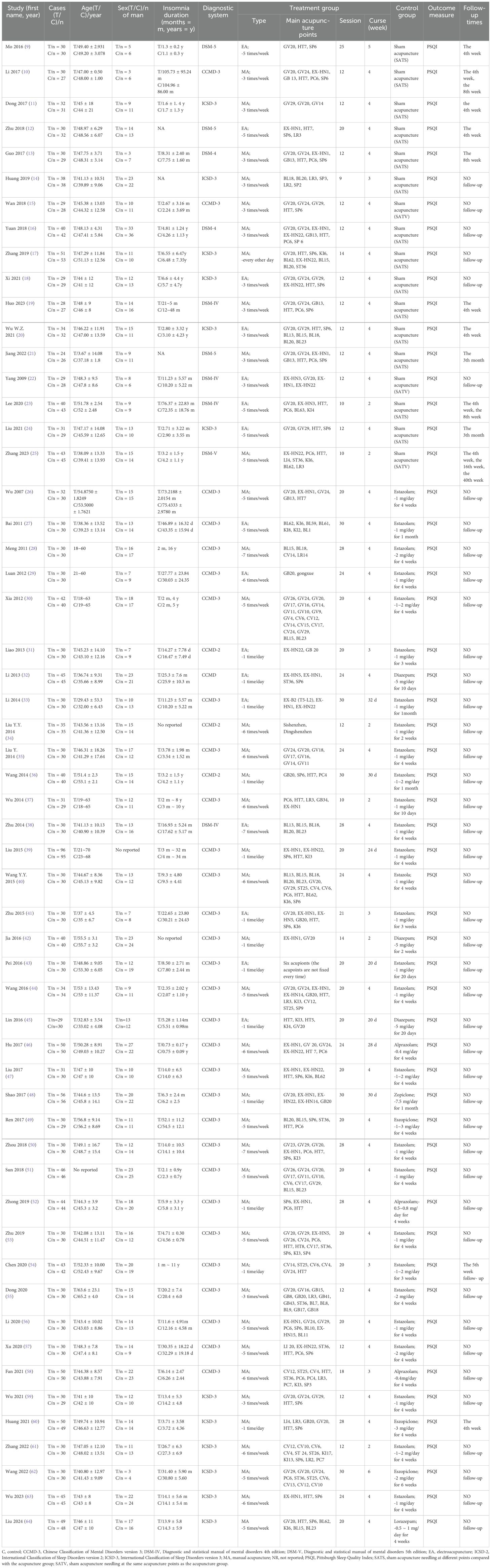

The features of the included studies are shown in Table 1. Of the included studies, 55 (9–22, 24–64) were conducted in China and one (23) was conducted in Korea. Of those conducted in China, four were published in English (22–25) and 52 in Chinese (9–21, 26–64). There were 17 RCTs (9–25) that compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture, while 39 RCTs (21–59) compared acupuncture with Western medication (sedative hypnotics).

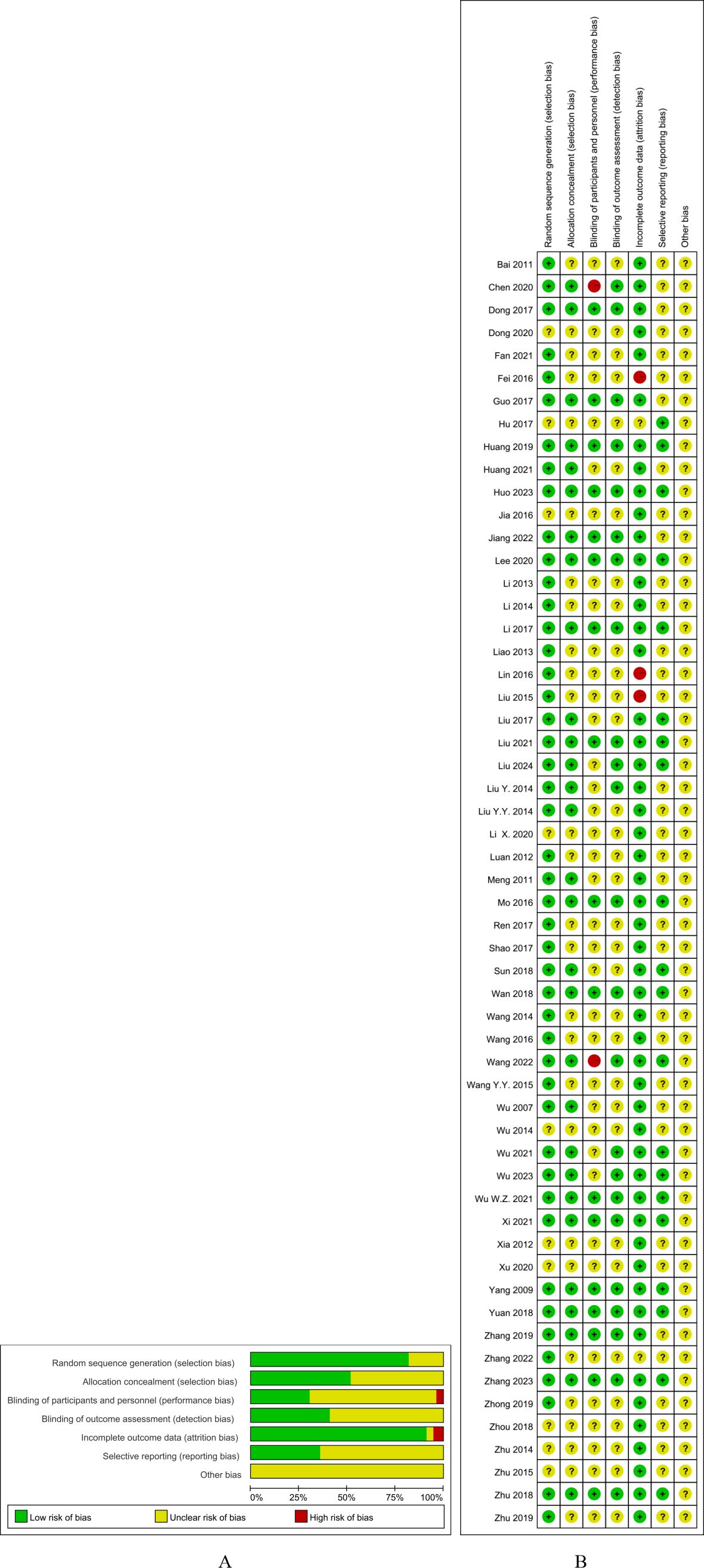

3.2 Risk of bias assessment

The parameters of quality assessment included the following:

a. Random sequence generation: Of the 56 RCTs, 46 (9–29, 31–36, 39, 40, 43–45, 47–53, 58–64) (82.1%) had a low risk of bias for random sequence generation.

b. Allocation concealment: There were 29 RCTs (9–22, 28, 34, 35, 47, 51, 54, 56, 59, 60, 62–64) that were judged to have a low risk of bias for this item.

c. Blinding of participants and personnel: As acupuncture must be performed by a qualified professional, it was impossible to blind the acupuncturists. Only 17 (30.4%) of the RCTs (9–24) that used sham acupuncture as a control involved blinding of the patients.

d. Blinding of outcome assessment: There were 23 RCTs (9–25, 35, 54, 59, 62–64) (41.1%) that involved blinding of the data evaluators.

e. Incomplete outcome data: A total of 51 RCTs (9–38, 40–42, 44, 47–60, 62–64) (91.1%) were rated as showing a low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data.

f. Selective reporting: Of the RCTs, 20 (35.7%) (9, 10, 12, 14–16, 18–20, 22–25, 46, 47, 50, 59, 62–64) showed a low risk of bias as their protocols were registered.

g. None of the RCTs described other sources of bias and were rated as showing unclear risk (Figure 2).

4 Meta-analysis

The 56 RCTs could be classified into two groups based on the comparator used: 1) acupuncture vs. sham acupuncture (17 RCTs) and 2) acupuncture vs. Western medication (sedative hypnotics; 39 RCTs).

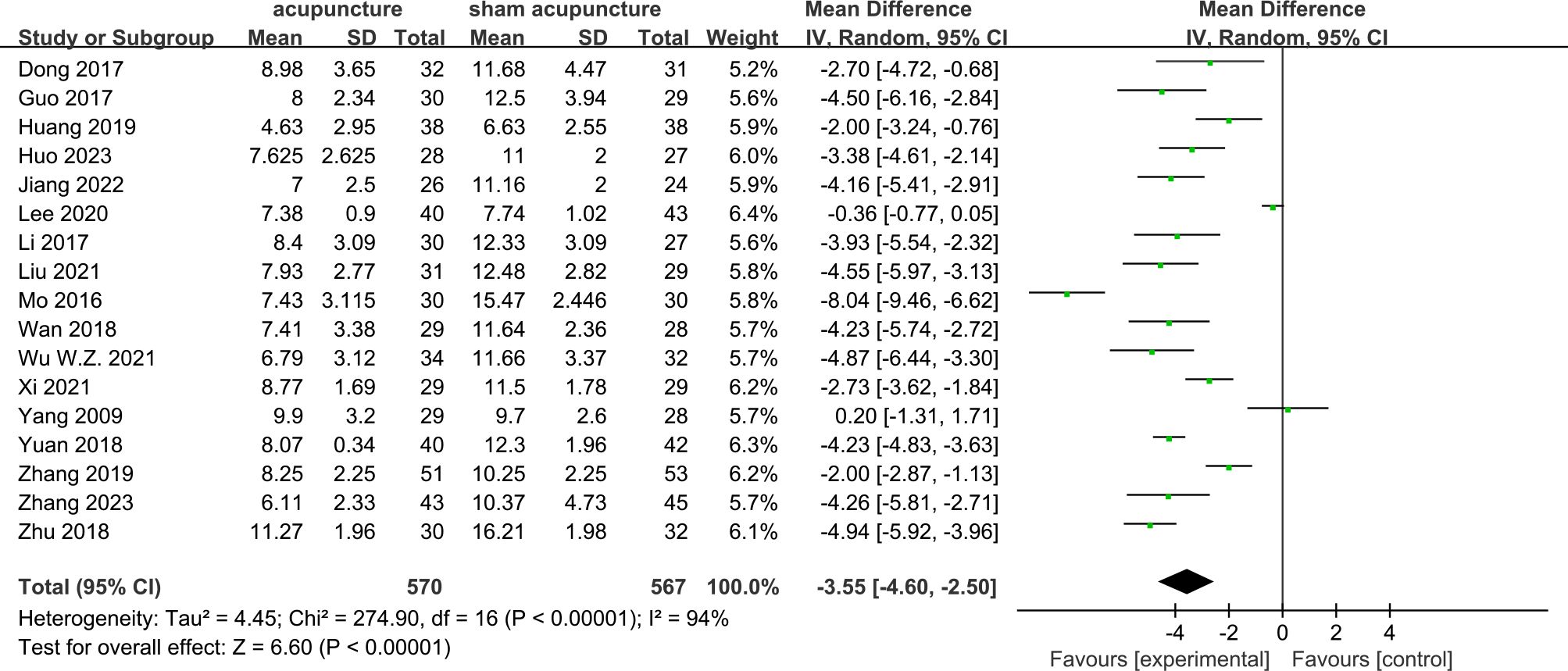

4.1 Acupuncture vs. sham acupuncture

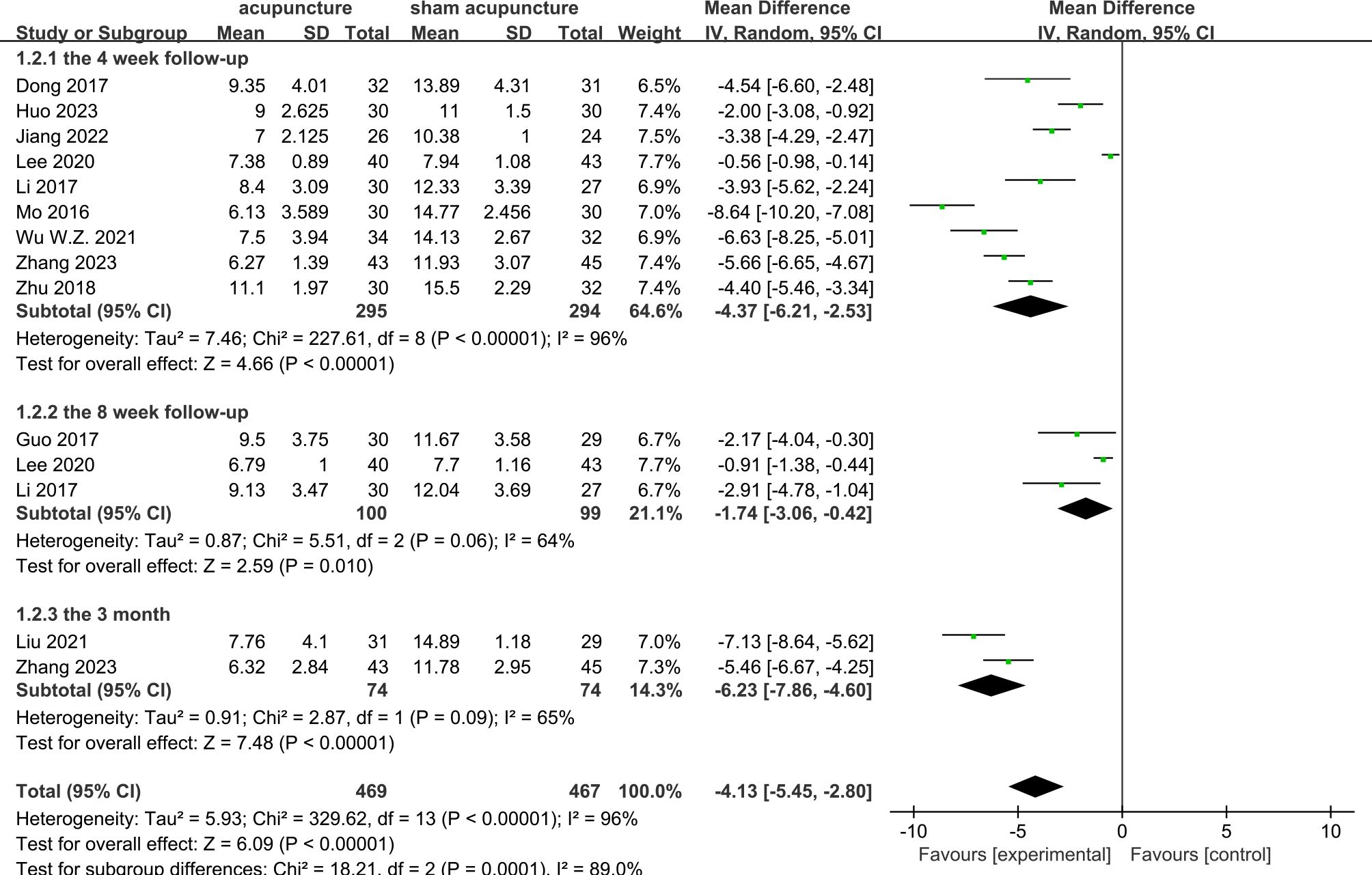

PSQI scores were reported in all 17 RCTs (9–25). The results of the meta-analysis revealed that acupuncture significantly lowered the PSQI scores compared with sham acupuncture (MD = −3.55, 95%CI = −4.6 to −2.5, p < 0.00001, I2 = 94%) (Figure 3). Due to the high heterogeneity, a random effects model was used. At the 4-week follow-up, eight RCTs (9–12, 19, 20, 23, 25) showed that acupuncture was associated with lowering of the PSQI scores compared with sham acupuncture (MD = −4.37, 95%CI = −6.21 to −2.53, p < 0.00001, I2 = 96%). At the 8-week follow-up, three RCTs (18, 65, 66) reported that acupuncture resulted in a significant reduction of the PSQI scores compared with sham acupuncture (MD = −1.74, 95%CI = −3.06 to −0.42, p = 0.01, I2 = 64%). At the 3-month follow-up, two RCTs (16, 19) showed acupuncture to have a significant difference compared with sham acupuncture (MD = −6.23, 95%CI = −7.86 to −4.60, p < 0.00001, I2 = 65%) (Figure 4). Subgroup analyses were performed to determine the heterogeneity of the outcomes. For the different acupuncture methods (MA or EA) (Supplementary Figure S1) and the different number of acupoints (≥10 or <10) (Supplementary Figure S2), the findings suggested that acupuncture was significantly more effective than sham acupuncture in both subgroups. However, there were no statistically significant associations with the therapeutic effect (MA vs. EA: Chi2 = 0.00, df = 1, p = 0.94; ≥10 vs. <10: Chi2 = 0.24, df = 1, p = 0.64). The results of the sensitivity analysis showed that it remained essentially unchanged after omitting any one study, suggesting that the research results were credible and relatively stable (Supplementary Figure S3). The results of Egger’s test (p = 0.009) suggested a potential risk of publication bias, as indicated by the asymmetry in the funnel plots (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 3. Forest plots of acupuncture vs. sham acupuncture for the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) after treatment.

Figure 4. Forest plots of acupuncture vs. sham acupuncture for the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) at the 4-week, 8-week, and 3-month follow-up.

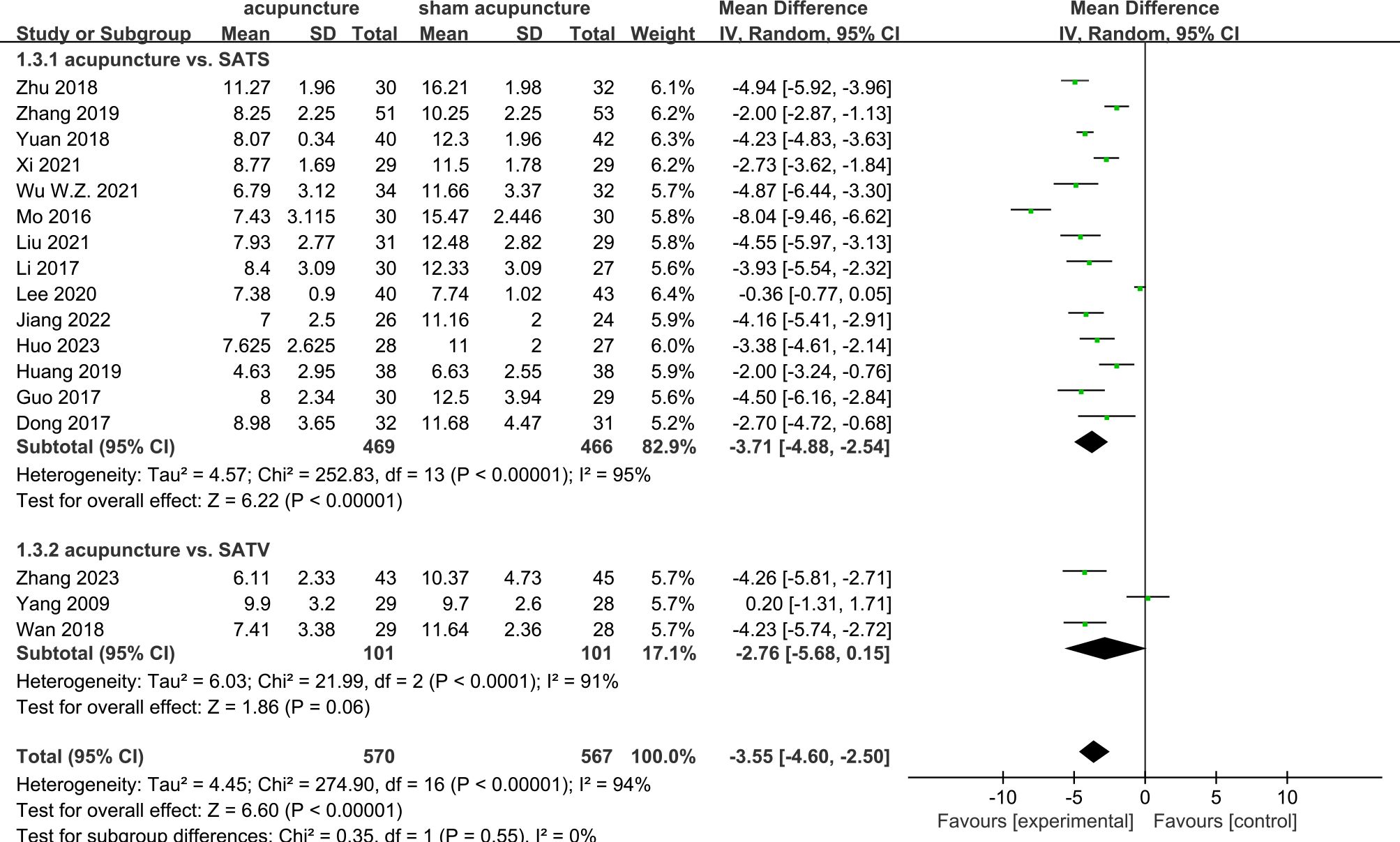

4.2 Sham acupuncture type

In order to evaluate the specific effects of acupuncture, sham acupuncture was classified according to the needling points as follows: 1) SATS (sham acupuncture therapy), which is sham acupuncture needling at different points compared with the acupuncture group, and 2) SATV (sham acupuncture therapy, verum), which is sham acupuncture needling at the same acupuncture points as the acupuncture group. Of the RCTs, 14 (9–14, 16–21, 23, 24) performed SATS and three (15, 22, 25) performed SATV. Compared with SATS, acupuncture showed a significant association with the reduction of the PSQI scores (MD = −3.71, 95%CI = −4.88 to −2.54, p < 0.00001, I2 = 95%). However, there were no differences between acupuncture and SATV (MD = −2.76, 95%CI = −5.68 to 0.15, p = 0.06, I2 = 91%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Forest plots of the different sham acupuncture types (SATS or SATV) for the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).

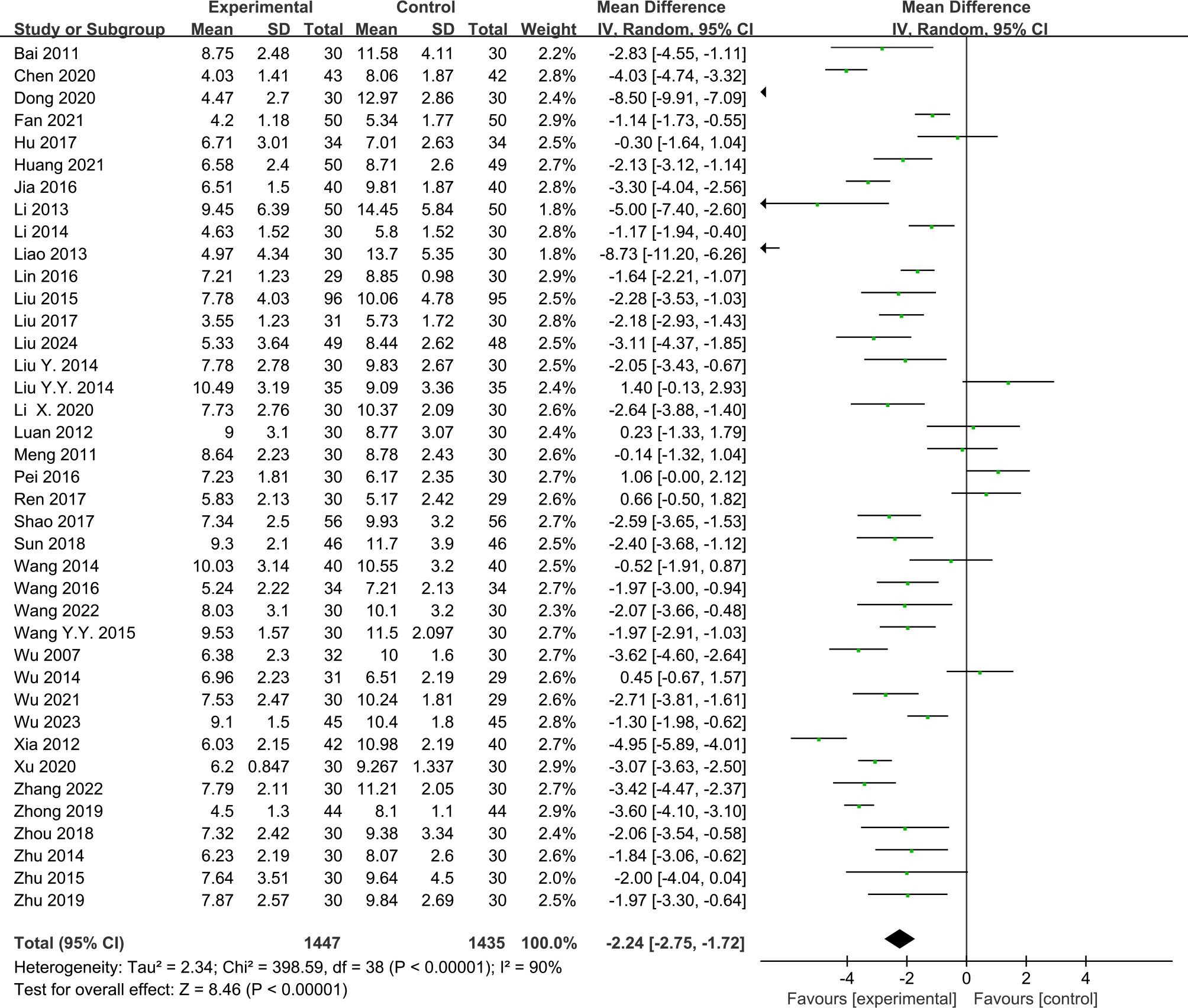

4.3 Acupuncture vs. Western medication

A total of 39 RCTs (26–64) were included. The results of the meta-analysis revealed that acupuncture significantly reduced the PSQI scores more than Western medication (MD = −2.24, 95%CI = −2.75 to −1.72, p < 0.00001, I2 = 90%) (Figure 6). Due to the high heterogeneity, a random effects model was used. In the subgroup analyses, the results for the different acupuncture types (MA or EA) (Supplementary Figure S5) and the number of acupoints (≥10 or <10) (Supplementary Figure S6) showed that acupuncture had a significant difference compared with Western medication. No significant interaction effects were found in the subgroups (MA vs. EA: Chi2 = 0.03, df = 1, p = 0.85; ≥10 vs. <10: Chi2 = 0.61, df = 1, p = 0.44). The sensitivity analysis demonstrated the good robustness of the results (Supplementary Figure S7). The funnel plots showed apparent asymmetry (Supplementary Figure S8), and the p-value was 0.002 in the Egger’s test; thus, it was assessed that there may be some publication bias.

Figure 6. Forest plots of acupuncture vs. Western medication for the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) after treatment. WM, Western medication.

4.4 Acupuncture dose and the PSQI score

All 56 RCTs were included to investigate potential correlations between efficacy and acupuncture dose (acupuncture frequency, acupuncture session, and acupuncture course).

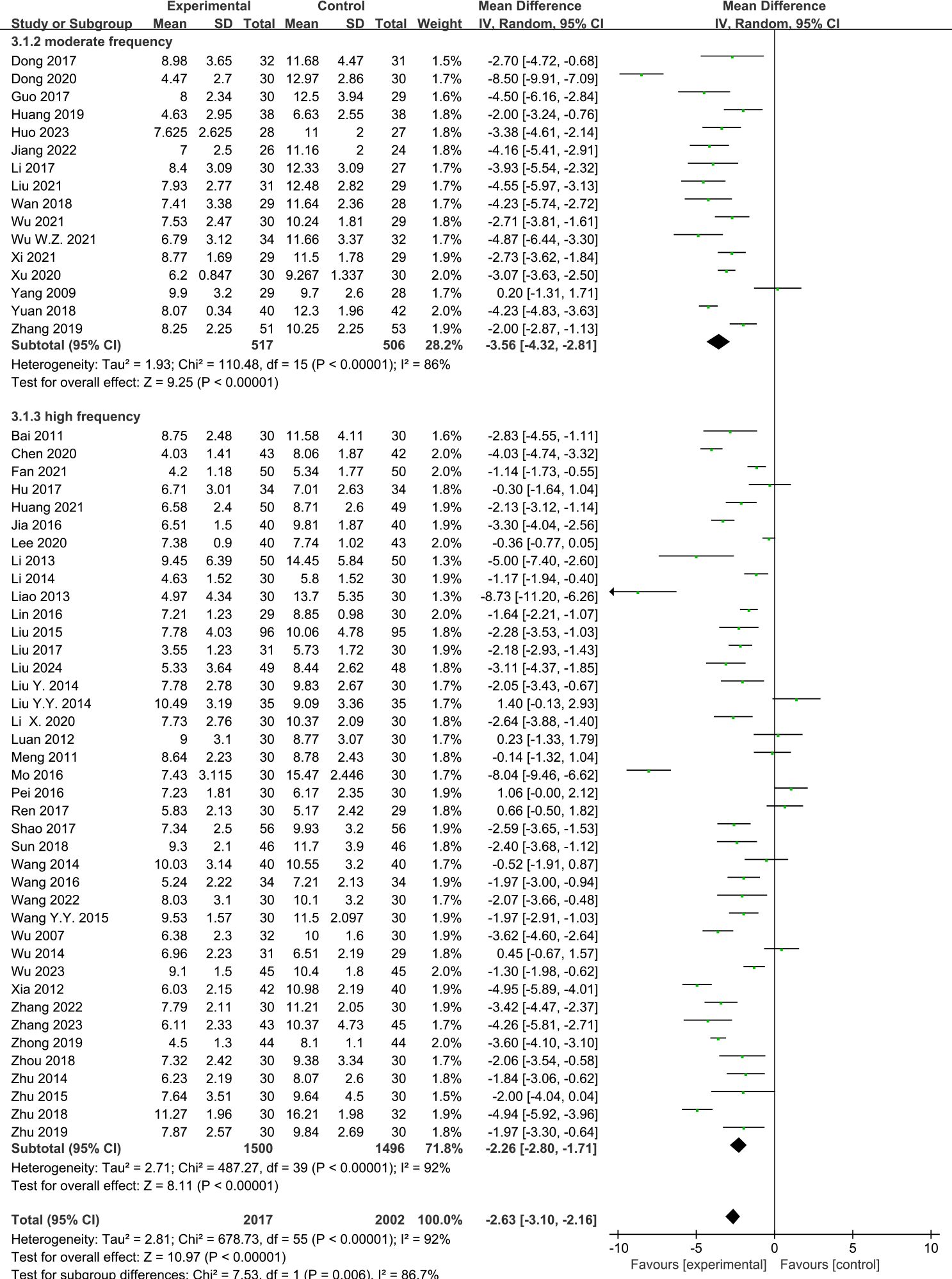

4.4.1 Acupuncture frequency and the PSQI score

There were 16 RCTs (10, 11, 13–22, 24, 55, 57, 59) that reported the effect of moderate-frequency acupuncture and 40 RCTs (9, 12, 23, 25–54, 56, 58, 60–64) that reported the effect of high-frequency acupuncture on PI. The pooled results showed that acupuncture had a significantly greater effectiveness compared with the control group in lowering the PSQI scores, within both the moderate-frequency group (MD = −3.56, 95%CI = −4.32 to −2.81, p < 0.00001, I2 = 86%) and the high-frequency group (MD = −2.26, 95%CI = −2.80 to −1.71, p < 0.00001, I2 = 92%) (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Effects of acupuncture on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores based on different frequencies.

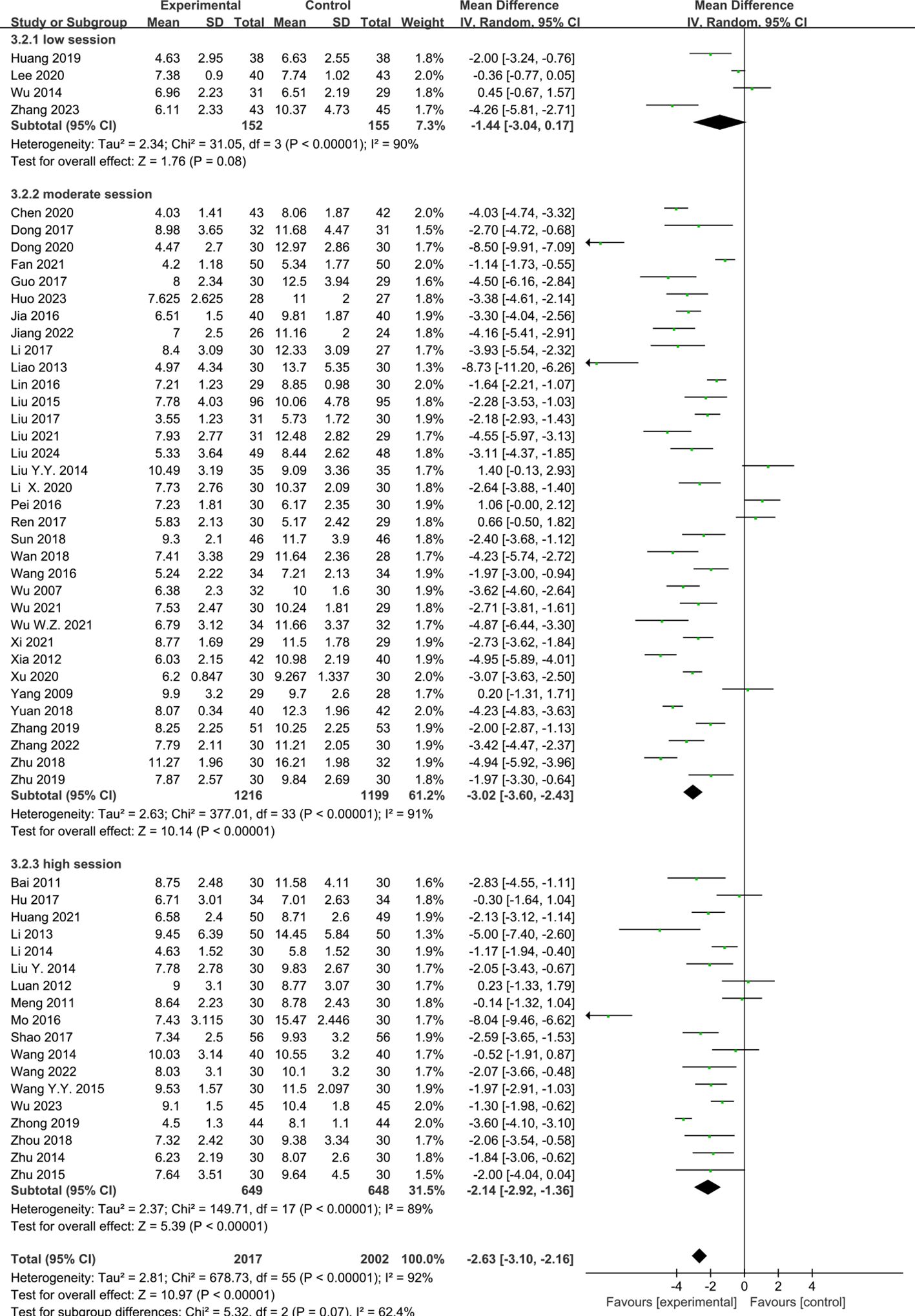

4.4.2 Acupuncture session and the PSQI score

Of the RCTs, four (14, 23, 25, 37) reported the effect of low-session acupuncture, 34 (10–13, 15–22, 24, 26, 30, 31, 34, 39, 42–45, 47, 49, 51, 53–59, 61, 64) reported the effect of moderate-session acupuncture, and 18 (9, 27–29, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 40, 41, 46, 48, 50, 52, 60, 62, 63) reported the effect of high-session acupuncture on PI. The pooled results showed that acupuncture was observed to have a significant difference compared with the control group in the improvement of the PSQI scores in the moderate-session group (MD = −3.02, 95%CI = −3.60 to −2.43, p < 0.00001, I2 = 91%) and the high-session group (MD = −2.14, 95%CI = −2.92 to −1.36, p < 0.00001, I2 = 89%). However, there were no differences between the acupuncture and control groups in the low-session group (MD = −1.44, 95%CI = −3.07 to −0.17, p = 0.08, I2 = 90%) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Effects of acupuncture on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores based on different sessions.

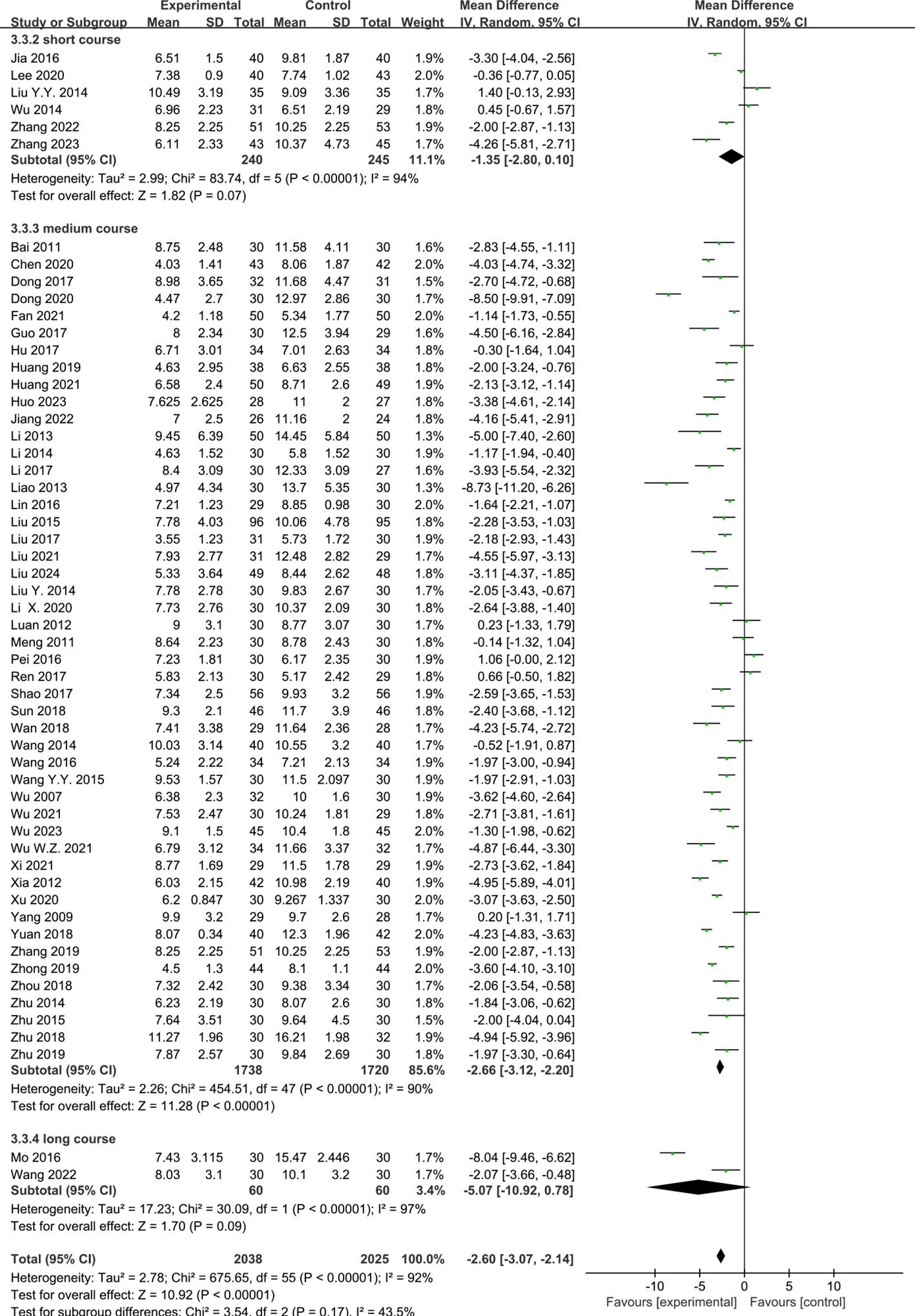

4.4.3 Acupuncture course and the PSQI score

Six RCTs (23, 25, 34, 37, 42, 61) reported the effect of short-course acupuncture on insomnia, 49 RCTs (10–24, 26–33, 35, 36, 38–41, 43–60, 63, 64) the effect of medium-course acupuncture, and two RCTs (9, 62) the effect of long-course acupuncture. The pooled results indicated that acupuncture was more effective than the control group in terms of the PSQI scores in the medium-course group (MD = −2.66, 95%CI = −3.12 to −2.20, p < 0.00001, I2 = 90%). However, no greater difference than the control group in the short-course group (MD = −1.35 [95% CI −2.80, 0.10], P = 0.07, I2 = 94%) and the high-course group was shown (MD = −1.56, 95%CI = −3.38 to 0.26, p = 0.09, I2 = 93%) (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Effects of acupuncture on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores based on different courses.

4.5 Quality assessment

The available evidence was evaluated using the GRADE tool. The quality of evidence on acupuncture for PI was graded as “moderate, low, or very low.” Details are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

5 Discussion

5.1 Main findings

This systematic review evaluated the impact of acupuncture on the PSQI scores of individuals with PI based on 56 RCTs that included 4,019 participants. The results demonstrated the efficacy of acupuncture in patients with PI, evidenced by the significant reduction in the PSQI scores compared with those for sham acupuncture or Western medication. Despite the significant heterogeneity observed among the studies, the sensitivity analysis revealed good robustness. In the subgroup analyses, the results indicated that there was no significant association between the different acupuncture types and the number of acupoints with regard to efficacy. As is well known, pharmacological treatment highlights accurate drug frequency and the duration of treatment. Similar principles are applied in acupuncture. Therefore, based on the above results, we opted to disregard the differences, assuming equivalent efficacy, and investigated the influence of acupuncture frequency, acupuncture session, and acupuncture course. The findings suggested that at least three sessions per week for 3–4 weeks and a total of at least 12 acupuncture sessions would be the optimal dosage of acupuncture for PI.

In terms of acupuncture frequency, the results showed that moderate frequency (three sessions per week) and high frequency (five to seven sessions per week) were beneficial for the improvement of sleep quality. Therefore, acupuncture might confer better effects when the treatment frequency is at least three sessions per week. For acupuncture session, the effect of low session (≤10 sessions) was not statistically significant. It showed better effects on the reduction of the PSQI scores until moderate session (12–20 sessions) and high session (24–30 sessions) were reached, indicating that the acupuncture treatment needs to reach a certain dose in order to obtain better therapeutic effects. Therefore, an acupuncture dose of ≥12 sessions should be recommended to achieve better clinical therapeutic effects in clinical practice. This finding was consistent with previous research, which showed that 12 or more acupuncture sessions yielded superior results compared with 6–10 sessions (67). With regard to the acupuncture course, the short (≤2 weeks) and long courses (>4 weeks) showed no obvious differences between acupuncture and sham acupuncture or Western medication. Medium course (3–4 weeks) was considered as the optimal course for acupuncture. The analysis indicated that acupuncture demonstrated comparable efficacy to sham acupuncture or Western medication during the initial 1–2 weeks. However, by the third week, the efficacy of acupuncture surpassed that of sham acupuncture or Western medication. For patients with slow or poor response to Western medication, with strong adverse reactions, or those seeking non-pharmacological options, this finding underscored that acupuncture can serve as an alternative treatment option. The results also indicated that treatment duration of at least 3 weeks can serve as a reference point for the onset of action in clinical treatment, aiding clinicians in refining the treatment plans and assessing efficacy. Nevertheless, extending the treatment to more than 4 weeks did not confer additional benefits. This is related to the “after-effect” of acupuncture treatment. In this meta-analysis, acupuncture was shown to still significantly improve sleep quality at the 4-week, 8-week, and 3-month follow-up. Therefore, continuous acupuncture might lead to “fatigue” of the acupuncture points, which greatly reduces its efficacy. Some studies have found that the long course may be associated with better efficacy of acupuncture, which differed from our results (68, 69). However, as the number of studies with long course was small in this meta-analysis, the current evidence is insufficient. Thus, more high-quality RCTs are needed to verify this in the future.

In this meta-analysis, the outcome of sham acupuncture according to the needling points was also investigated to evaluate the specific effects of acupuncture. The results showed that there was a significant difference between acupuncture and SATS. However, no significant difference was observed between acupuncture and SATV in the PSQI scores. Interestingly, the findings were consistent with those of previous meta-analyses of cancer-related pain (70) and chronic nonspecific low back pain (71), which were conducted using the same hypothesis. These results indicated that the clinical outcome of sham acupuncture could differ depending on whether its needling point is the same as that used in the acupuncture group, suggesting that needling at the same acupuncture points may not be regarded as a true placebo control as there is no consideration for acupuncture point specificity. It is possible that sham contact with acupuncture points is a modified form of acupuncture instead of a true placebo. This result examined the point specificity of acupuncture by analyzing the outcome of sham acupuncture according to the needling point. To obtain more credible evidence, it will be necessary in the future to carry out a direct comparative trial of acupuncture and the above different type of sham acupuncture.

5.2 Implications for practice and research

The number of studies on acupuncture for insomnia has increased exponentially in recent years; however, the relationship between acupuncture dose and its effect remains unclear. To some extent, this limits the use of acupuncture. For any kind of drug intervention, the relationship between the therapeutic dose and efficacy is critical. Similarly, the relationship between the acupuncture dose and clinical efficacy should be studied and is of great clinical value. This dose–effect meta-analysis suggested that at least three sessions per week for 3–4 weeks and a total of at least 12 acupuncture sessions may be recommended. A prolonged acupuncture course might not increase its efficacy. Therefore, considering the economic burden of patients, when patients with insomnia have agreed to acupuncture treatment for 12 sessions within 3–4 weeks in clinical practice, acupuncture can then be stopped for a period of time to avoid body tolerance. The included studies only used subjective outcome measurements (PSQI score). In order to confirm the conclusion, an objective outcome [polysomnography (PSG) or actigraphy] might be better than a subjective outcome measurement as it is less affected by subjective factors.

5.3 Limitations

This meta-analysis has several limitations. Firstly, the number of studies included was limited, particularly for long-course acupuncture, which could have lowered the precision of the results and affected the certainty of the evidence. Secondly, the patients included in the trials had different degrees of sleep disorder, resulting in a possible clinical heterogeneity between studies. Thirdly, the quality of some of the included RCTs was relatively low, which could have influenced the accuracy of the results. Finally, as all but one of the studies were conducted in China, it was considered that there was potential for publication bias as triggered by the cultural background of different regions and countries. Accumulating evidence suggests that the Asia-Pacific region is more inclined toward acupuncture treatment and publishes positive results.

6 Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that acupuncture could play a positive role in the management of insomnia, although the evidence level was very low to moderate. A dose–effect relationship was found between the dose (frequency, session, and course) of acupuncture and the clinical response. Comparison of several different doses will help explore the best treatment options and guide clinical decision making. However, further study is necessary to confirm the dose–effect relationship of acupuncture in PI.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

WW: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. YW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SQ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. LL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. CD: Writing – review & editing. ZC: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO.82274631), and the Nanjing Traditional Chinese Medicine Young Talents Project, China (ZYQ20049).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the library of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine for providing access to the different databases.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1501321/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Ferini-Strambi L, Auer R, Bjorvatn B, Castronovo V, Franco O, Gabutti L, et al. European Sleep Foundation Insomnia disorder: clinical and research challenges for the 21st century. Eur J Neurol. (2023) 28:2156–67. doi: 10.1111/ene.14784

2. de Bergeyck R, Geoffroy PA. Insomnia in neurological disorders: Prevalence, mechanisms, impact and treatment approaches. Rev Neurol (Paris). (2023) 179:767–81. doi: 10.1016/j

3. Meyer N, Schmidt RLC, Schmid C, Kyle SD, McClung CA, Cajochen C, et al. The sleep-circadian interface: A window into mental disorders. PNAS. (2024) 121:e2214756121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2214756121

4. Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Gregoire JP, Savard J. The economic burden of insomnia: direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep. (2009) 32:55–64. doi: 10.5665/sleep/32.1.55

5. Tseng LY, Huang ST, Peng LN, Chen LK, Hsiao FY. Benzodiazepines, z-hypnotics, and risk of dementia: special considerations of half-lives and concomitant use. Neurotherapeutics. (2020) 17:156–64. doi: 10.1007/s13311-019-00801-9

6. Zweerde T, Bisdounis L, Kyle SD, Lancee J, van Straten A. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a meta-analysis of long-term effects in controlled studies. Sleep Med Rev. (2019) 48:101208. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.08.002

7. Kim S-A, Lee S-H, Kim J-H, Noort M, Bosch P, Won T, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Chin Med. (2021) 49:1135–50. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X21500543

8. Lu Y, Zhu HF, Wang Q, Tian C, Lai HH, Hou LY, et al. Comparative effectiveness of multiple acupuncture therapies for primary insomnia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trial. Sleep Med. (2022) 93:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2022.03.012

9. Mo YT. The effect of Sancai Acupoints combination on ET and PSQI in patients with primary insomnia. (Master Thesis). Changchun, China: Changchun Univ Chinese. (2016).

10. Li HQ, Zou YH, Guo J, Wei J, Cao KG. Treatment of 30 cases of primary insomnia by Zhou’s acupuncture method. Global Traditional Chin Med. (2017) 10:882–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-1749.2017.07.033

11. Dong B, Chen ZQ, Ma J, Yi P, Li SS, Xu SF. Clinical curative observation of applying acupuncture at EX-HN3, GV20 and GV14 with periosteal puncture method in the treatment of primary insomnia. J Sichuan Traditional Chin Med. (2018) 36:176–8. doi: CNKI:SUN:SCZY.0.2018-03-062

12. Zhu YS. Tranquilize mind acupunctures treatment of liver depression to fire clinical observation of primary insomnia. (master thesis). Changchun, China: Changchun University of Chinese Medicine (2018).

13. Guo J, Tang CY, Wang LP. Effect of tiaoshen acupuncture therapy on sleep quality and hyperarousal state in primary insomnia. J Clin Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2017) 33:1–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-0779.2017.06.001

14. Huang TY. Clinical effects research and fMRI research of neijing “shu ci “ acupuncture method in treatment of insomnia with liver-qi depression and spleen deficiency. (master thesis). Shanghai, China: Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2019). doi: 10.27320/d.cnki.gszyu.2019.000013

15. Wan QY. Clinical observation of intervention on chronic insomnia with “Tong Du Tiao Shen” acupuncture. (master thesis). Nanjing, China: Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (2019).

16. Yuan F, Guo J. Clinical study on acupuncture treatment of patients with primary insomnia based on ‘Zhoujing Yeming’ theory. China J Traditional Chin Med Pharmacy. (2019) . 34:5993–6. doi: CNKI:SUN:BXYY.0.2019-12-125

17. Zhang F. Acupuncture regulates hyperarousal in chronic insomnia with deficiency of heart and spleen. (master thesis). Beijing, China: Beijing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2019).

18. Xi HQ, Wu WZ, Liu CY, Wang XQ, Qin S, Zhao YN, et al. Effect of acupuncture at Tiaoshen acupoints on hyperarousal state in chronic insomnia. Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2021) 41:263–7. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20200303-k0004

19. Huo Y, Chen ZY, Yin XJ, Jiang TF, Wang GL, Cui XY, et al. Tiaoshen acupuncture for primary insomnia: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2023) 43:1008–13. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20221120-0001

20. Wu WZ, Zhao YN, Liu CY, Qin S, Wang XQ, Xu YQ, et al. Effects of electroacupuncture on sleep quality, daytime fatigue and serum cortisol in chronic insomnia. China J Traditional Chin Med Pharmacy. (2021) 36:5693–6.

21. Jiang TF. Effect of tiaoshen acupuncture on emotional network in patients with insomnia: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Beijing, China: Beijing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2022). doi: 10.26973/d.cnki.gbjzu.2022.000531

22. Yeung WF, Chung KF, Zhang SP, Yap TG, Law AC. Electroacupuncture for primary insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. (2009) 32:1039–47. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.8.1039

23. Lee B, Kim BK, Kim HJ, Jung IC, Kim AR, Park HJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of electroacupuncture for insomnia disorder: A multicenter, Randomized, Assessor-Blinded, Controlled Trial. Nat Sleep. (2020) 12:1145–59. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S281231

24. Liu C, Zhao Y, Qin S, Wang X, Jiang Y, Wu W. Randomized controlled trial of acupuncture for anxiety and depression in patients with chronic insomnia. Ann Trans Med. (2021) 9:1426. doi: 10.21037/atm-21-3845

25. Zhang L, Deng Y, Hui R, Tang Y, Yu S, Li Y, et al. The effects of acupuncture on clinical efficacy and steady-state visual evoked potentials in insomnia patients with emotional disorders: A randomized single-blind sham-controlled trial. Front Neurol. (2023) 13:1053642. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1053642

26. Wu X. Effect of acupuncture of Zhou’s Tiaoshen decoction on sleep quality in patients with primary insomnia: a randomized controlled study. (master thesis). Beijing, China: Beijing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2007).

27. Bai WJ, Zhang ZQ. Clinical study of heel vessel acupuncture treating insomnia. Chin Arch Traditional Chin Med. (2011) 29:413–4. doi: 10.13193/j.archtcm.2011.02.191.baiwj.005

28. Meng FY. Back-shu point and front-mu point of acupuncture treatment of positive insomnia by the clinical research. (master thesis). Harbin, China: Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine (2011).

29. Luan YH. Clinical study on electro-nape-acupuncture treatment of insomnia. (master thesis). Harbin, China: Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine (2012).

30. Xia XF. Clinical observations on ren-du-meridian-regulating acupuncture therapy for insomnia of yin deficiency with effulgent fire type. Shanghai J Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2012) 31:869–70. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-0957.2012.12.869

31. Liao H, Gao YJ, Liao S. Clinical observation of 30 cases of insomnia treated with electro acupuncture. Jiangsu J Tradit Chin Med. (2013) p. 45–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-397X.2013.07.033

32. Liu JY, Wei XT. Clinical observation of electroacupuncture in the treatment of insomnia with deficiency of both heart and spleen. Shenzhen J Integrated Traditional Chin Western Med. (2013) 23:168–70. doi: 10.16458/j.cnki.1007-0893.2013.03.005

33. Li F. Clinical curative effect observation of Jiaji electroacupuncture for patients with primary insomnia. (master thesis). Harbin, China: Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine (2014).

34. Liu YY. Clinical study of Sishenzhen combined Dingshenzhen treatment for primary insomnia. (master thesis). Guangzhou, China: Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2014).

35. Liu Y. Clinical research of the therapy of insomnia with the method of treating gowernor vessel acupoints. (master thesis). Hefei, China: Anhui University of Chinese Medicine (2014).

36. Wang ZH. The clinical research of using accupuncture”An mian wu xue”to cure simple insomnia. (master thesis). Shijiazhuang, China: Hebei Medical University (2014).

37. Wu JM, Zhuo YY, Zhong YL, Chen QL. Clinical study on acupuncture treatment of insomnia from the heart of liver. Guangming J Chin Med. (2014) 29:1017–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-8914.2014.05.061

38. Zhu LL. Clinical study of needling by five zang-organs regulating five zang-soul in insomnia patients. (master thesis). Changchun, China: Changchun University of Chinese Medicine (2014).

39. Liu F, Wang L, Wei QP, Wang ZH, Chen DM, Li CY, et al. Clinical curative observation of applying acupuncture at shen-you time to regulate 196 cases of insomnia. J Sichuan Traditional Chin Med. (2015) 33:174–6. doi: CNKI:SUN:SCZY.0.2015-08-086

40. Wang YY. Clinical study of insomnia with the treatment of Tongdutiaoshen-Yinqiguiyuan. (master thesis). Guangzhou, China: Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (2015).

41. Zhu YL. Effect observation on treatment of primary insomnia by head of a Pin electric stimulation. Chin Health Standard Management. (2015) 6:130–2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-9316.2015.26.095

42. Jia YM. Effects of the serum amino acid neurotransmitter by acupuncture GV14, GV20 in insomnia. Chin J Medicinal Guide. (2016) 18:567–71. doi: CNKI:SUN:DKYY.0.2016-06-010

43. Pei Y. The observation time point injection adopted method combined with the therapeutic effect of electroacupuncture in the treatment of primary insomnia. (master thesis). Harbin, China: Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine (2016).

44. Wang YJ, Zhang LH, Han YX, Li PP. Efficacy observation on Governor Vessel-unblocking and mind-calming acupuncture for insomnia. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. (2016) 14:274–8. doi: 10.1007/s11726-016-0935-1

45. Lin YX. A Clinical Study on Treating imbalance between heart-yang and kidney-yin type of insomnia with Yuan-Luo point compatibility. (master thesis). Nanning, China: Guangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2016).

46. Hu WJ. Observation on the efficacy of acupuncture and moxibustion in the treatment of insomnia. Inner Mongolia J Traditional Chin Med. (2017) 36:114. doi: 10.16040/j.cnki.cn15-1101.2017.14.114

47. Liu Y, Feng H, Liu WJ, Mao HJ, Mo YL, Yi Y, et al. Regulation action and nerve electrophysiology mechanism of acupuncture on arousal state in patients of primary insomnia. Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2017) 37:19–23. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.2017.01.004

48. Shao Y. Clinical study on acupuncture for primary insomnia. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. (2017) 15:410–4. doi: 10.1007/s11726-017-1037-4

49. Ren S, Zhang J, Han X. Clinical observation of invigorating spleen and nourishing heart acupuncture treatment on insomnia. China J Traditional Chin Med Pharmacy. (2017) 32:4303–6. doi: CNKI:SUN:BXYY.0.2017-09-122

50. Zhou B, Yuan Z, Feng H. Curative effect observation of 30 cases insomnia with heart yang kidney yin incoordination by regulating spirit and tonifying kidney acupuncture method. Tianjin J Traditional Chin Med. (2018) 35:264–6. doi: 10.11656/j.issn.1672-1519.2018.04.07

51. Sun JL. The effect of tone up as overseers method is given priority to acupuncture in the treatment of yin deficiency type fire insomnia. World J Sleep Med. (2018) 5:689–90. doi: CNKI:SUN:SMZZ.0.2018-06-021

52. Zhong LX. Observation on the therapeutic effect of acupuncture and moxibustion on patients with insomnia and its effect on sleep quality. World J Sleep Med. (2019) 6:1066–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-7130.2019.01.024

53. Zhu XH, Zhang F, Dai JL, Dou ZC, Yang M, Zhu RH, et al. Clinical study on Tongdu Tiaoshen acupuncture in the treatment of insomnia. Lishizhen Med Mater Med Res. (2019) 30:389–90. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-0805.2019.02.042

54. Chen H, Chai TQ. Observations on the therapeutic effect of acupoint selection of Yinhuo Guiyuan on insomnia by the type of yin deficiency and fire hyperactivity. J Tianjin Univ Traditional Chin Med. (2020) 39:300–3. doi: 10.11656/j.issn.1673-9043.2020.03.12

55. Dong J, Ding JY, Zhang YY, Xiang SY, Cui HX. Clinical observation of acupuncture on the treatment of insomnia with syndrome of internal disturbance of phlegm-heat. World J Sleep Med. (2020) 7:606–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-7130.2020.04.019

56. Li X, Lu JM, Zhong BM. Observation on the therapeutic effect of mind-regulation acupuncture combined with cervical three points in the treatment of insomnia due to deficiency of both heart and spleen. Guangming J Chin Med. (2020) 35:3777–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-8914.2020.23.043

57. Xu YY, Lin XM. Clinical study on acupuncture of six points in regulating spirit and sleep three needle points for primary insomnia of liver fire disturbing heart type. J New Chin Med. (2020) 52:151–3. doi: 10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2020.03.045

58. Fan JJ, Zhang HY, Zhang DX, Liu J, Zhou XL, Wei LP. Observation on the effect of Shengyang Yiwei acupuncture on insomnia in 50 cases. Hunan J Traditional Chin Med. (2021) 37:78–80. doi: 10.16808/j.cnki.issn1003-7705.2021.03.027

59. Wu WZ, Zheng SY, Liu CY, Qin S, Wang XQ, Hu JL, et al. Effect of Tongdu Tiaoshen acupuncture on serum GABA and CORT levels in patients with chronic insomnia. Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2021) 41:721–4. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20200704-k0001

60. Huang SY. The observation on the clinical effect of shugan xiehuo anshen acupuncture on the treatment of insomnia type of liver depression and fire-transforming based on the thinking of tiaoshu. (master thesis). Fuzhou, China: Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2021). doi: 10.27021/d.cnki.gfjzc.2021.000302

61. Zhang XQ. Clinical observation of abdominal acupuncture combined with ordinary acupuncture in the treatment of insomnia of liver depression and fire and its effect on sleep quality. China’s Naturopathy. (2022) 30:55–7. doi: 10.19621/j.cnki.11-3555/r.2022.0119

62. Wang L. Clinical efficacy of Yingtang Periosteal acupuncture combined with Laoshi acupuncture in the treatment of chronic insomnia with decreased IgG and IgM. (master thesis). Hohhot, China: Inner Mongolia Medical University (2022). doi: 10.27231/d.cnki.gnmyc.2022.000138

63. Wu BX, Yang S, Huang R, Liao Y, Zhang XR. Clinical effect of acupuncture based on syndrome differentiation in the treatment of chronic insomnia and its influence on cognitive function. Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2023) 43:1014–7. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20230128-0004

64. Liu Y, Feng H, Yu ZH, Zhou CL, Chen GL, Wei YD. Acupuncture for reducing the south to reinforce the north on executive function and sleep structure in patients with chronic insomnia disorder of heart-kidney disharmony. Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2024) 44:384–8. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20230501-k0004

65. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

66. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. 2nd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2005).

67. Zhao F-Y, Fu Q-Q, Kennedy GA, Conduit R, Zhang W-J, Wu W-Z, et al. Can acupuncture improve objective sleep indices in patients with primary insomnia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. (2021) 80:244–59. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.01.053

68. Tang Y. The clinical study of Acupuncture cooperating with Moxibustion to treat Insomnia of Heart and Gallbladder Qi deficiency based on the method “combining yuan-source points and Lou-connecting points”. (master thesis). Chengdu, China: Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2023).

69. Wang B-L, Yan L-D, Zhu X, Fu W-B, Cheng N, Wu M-Y, et al. Clinical observation on the shugan tiaoshen acupuncture method combined with auricular acupuncture in the treatment of hypertension complicated with insomnia. J Guangzhou Univ Traditional Chin Med. (2023) 40:1974–80. doi: 10.13359/j.cnki.gzxbtcm.2023.08.019

70. Lee B, Kwon C-Y, Lee HW, Nielsen A, Wieland LS, Kim T-H, et al. Different outcomes according to needling point location used in sham acupuncture for cancer-related pain: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). (2023) 15:5875. doi: 10.3390/cancers15245875

Keywords: acupuncture, dose-effect, primary insomnia, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation: Zhang X, Wang Y, Liu C, Qin S, Lin L, Dong C, Wu W and Chen Z (2025) The dose–effect relationship between acupuncture and its effect on primary insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 16:1501321. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1501321

Received: 24 September 2024; Accepted: 10 January 2025;

Published: 10 February 2025.

Edited by:

Kittisak Sawanyawisuth, Khon Kaen University, ThailandReviewed by:

Katharine Reynolds, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, United StatesLihua Wu, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, China

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Wang, Liu, Qin, Lin, Dong, Wu and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenzhong Wu, bWFlcnRhX3pob25nYWN1QDE2My5jb20=; Zhaoming Chen, Y3ptNjcwNEAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Xiaoni Zhang1,2†

Xiaoni Zhang1,2† Wenzhong Wu

Wenzhong Wu