- 1Department of Philosophy, Social Sciences and Education, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy

- 2Laboratory of Experimental and Behavioral Neurophysiology, Scientific Institutes for Research, Hospitalization, and Healthcare (IRCCS) Santa Lucia Foundation, Rome, Italy

- 3Department of Psychology, University Sapienza of Rome, Rome, Italy

Introduction: Over the past few decades, research on affective touch has clarified its impact on key psychological functions essential for environmental adaptation, such as self-awareness, self-other differentiation, attachment, and stress response. These effects are primarily driven by the stimulation of C-tactile (CT) fibers. Despite significant advancements in understanding the fundamental mechanisms of affective touch, its clinical applications in mental health remain underdeveloped. This systematic review aims to rigorously assess the scientific literature on the relationship between CT fiber stimulation and psychological disorders, evaluating its potential as a therapeutic intervention.

Methods: This systematic review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. A search was performed in the EMBASE, PubMed, and Web of Science databases for articles published in the last 10 years. The review focused on two main aspects: (1) potential dysregulation of CT fibers in individuals with psychological disorders, and (2) psychological treatments based on CT fiber stimulation and their psychological and functional outcomes.

Results: Most studies investigating CT fiber dysregulation in psychological disorders reported sensory alterations, with patients rating affective touch as less pleasant than healthy controls. These differences were often associated with dysregulation in the reward network and interoceptive processing, with several studies suggesting reduced insular cortex activation as a contributing factor. Regarding psychological treatments, only a limited number of studies analyzed therapies based on CT fiber stimulation. Despite methodological variations and differences in psychological diagnoses, the available evidence suggests that affective touch therapies can effectively reduce symptom severity and improve interoception across different psychological conditions.

Discussion: The findings underscore the potential of affective touch as a therapeutic avenue for psychological disorders. However, given the dearth of studies on this topic, further analyses are necessary to fully understand its mechanisms and clinical efficacy. Expanding research in this area could provide valuable insights into functional impairments related to CT fiber dysregulation and support the development of targeted interventions for mental health treatment.

1 Introduction

Affiliative touch, characterized by slow and gentle gestures such as caresses and particularly effective when applied in a repetitive, rhythmic manner, constitutes a fundamental aspect of interpersonal sensorimotor interaction (1, 2). An expanding body of contemporary research on affective touch elucidates the underlying mechanisms of this specific form of skin contact, emphasizing its crucial role in a range of evolutionarily fundamental functions (1, 3). These functions include attachment, stress regulation, body representation, differentiation between self and others, and body ownership (2, 4–14).

The effects of affective touch are mediated by the activation of C-tactile (CT) unmyelinated fibers, a specialized class of low-threshold mechanoreceptors located in hairy skin that optimally respond to slow and gentle touch (15). CT fibers conduct signals at a velocity of approximately 1 m/s, significantly slower than myelinated Aβ fibers, which are responsible for processing discriminative touch (2). Experimental studies indicate that brush strokes applied at velocities between 1 and 10 cm/s, particularly at skin temperature, are consistently rated as more pleasant compared to those delivered at either slower or faster speeds (16). Microneurography studies have shown that the optimal velocity for activating CT fibers is between 1 and 10 cm/s, while velocities exceeding 10 cm/s activate only a limited number of CT fibers (17).

CT fiber activation is associated with the release of oxytocin (5) and dopamine (18), enhancing pleasure, alleviating pain, and reinforcing the attachment between caregiver and infant (5–7, 10). Research has demonstrated that skin-to-skin contact is correlated with elevated peripheral oxytocin levels in both parents and infants (19, 20) and that oxytocin levels peak after approximately 30 min of continuous, rhythmic stroking in both adults (2) and children (10). Notably, affective touch plays a crucial role in maintaining physiological stability in newborns, as evidenced by stable heart rate variability, suggesting its involvement in autonomic self-regulation and stress reduction (21). During stress-inducing situations, such as the Still Face paradigm, infants exhibit increased self-touch behaviors, highlighting the significance of affective touch in self-soothing mechanisms (22). Furthermore, infants engage in spontaneous self-touch, which contributes to the development of an early sense of self and body ownership (23, 24).

The CT fiber system establishes indirect connections with the posterior insular cortex (12, 25), primary (S1) and secondary (S2) somatosensory cortices, as well as the prefrontal cortex (11, 26) and precisely these connections may support the role of affective touch not only in the early development of interoceptive awareness but also in the integration of interoceptive and exteroceptive signals—a process fundamental to the emergence of bodily self-representation and the distinction between self and others (8, 13, 14, 27–29). In infants, gentle stroking has been found to activate both the S1 and the posterior insular cortex (30–32). Conversely, children raised in institutional care, who typically receive limited physical contact, often exhibit heightened sensitivity to sensory input, an increased prevalence of sensory processing difficulties, behavioral and psychological disorders, and, in some cases, an aversion to touch (33–36). These findings suggest that CT-mediated touch supports early sensorimotor and cognitive development as well as serves as a foundational element for relational and affective experiences throughout life.

On such a basis, a growing body of clinical research has explored the therapeutic potential of affective touch, demonstrating its efficacy in the treatment of various psychological disorders (37–41), in which the processes of body representation, differentiation between self and others, and body ownership are crucial. Despite this evidence, the implementation of affective touch in mental healthcare remains underdeveloped. A notable disparity exists between the substantial body of research on affective touch and the limited evidence-based clinical practices integrating this knowledge (42). Affective touch interventions are therapeutic techniques involving the application of gentle, non-intrusive physical contact, such as light stroking or holding, designed to promote emotional and psychological wellbeing. These interventions specifically engage CT afferents and include techniques such as therapeutic massage (43), Kangaroo Mother Care for preterm infants (44), affect-regulating massage therapy (ARMT) (45), psycho-regulatory massage therapy (PRMT) (46), mechanical affective touch therapy (MATT) (47, 48), and amniotic therapy (AT) (49). These therapies are utilized in various clinical settings, including pediatrics, geriatrics, psychiatry, and psychosomatic medicine, to enhance both mental and physical health.

The objective of this systematic review is to examine the scientific literature on the relationship between CT fiber stimulation and psychological disorders using a rigorous methodology. Specifically, we aim to (1) review studies assessing the potential dysregulation of CT fiber-mediated somatosensory processing in individuals with various psychiatric conditions, and (2) evaluate current psychological treatments that leverage CT fiber stimulation, analyzing their psychological and functional outcomes. By synthesizing existing findings, this review seeks to enhance the empirical framework for understanding the role of affective touch in psychopathology and its therapeutic potential in mental health interventions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Protocol

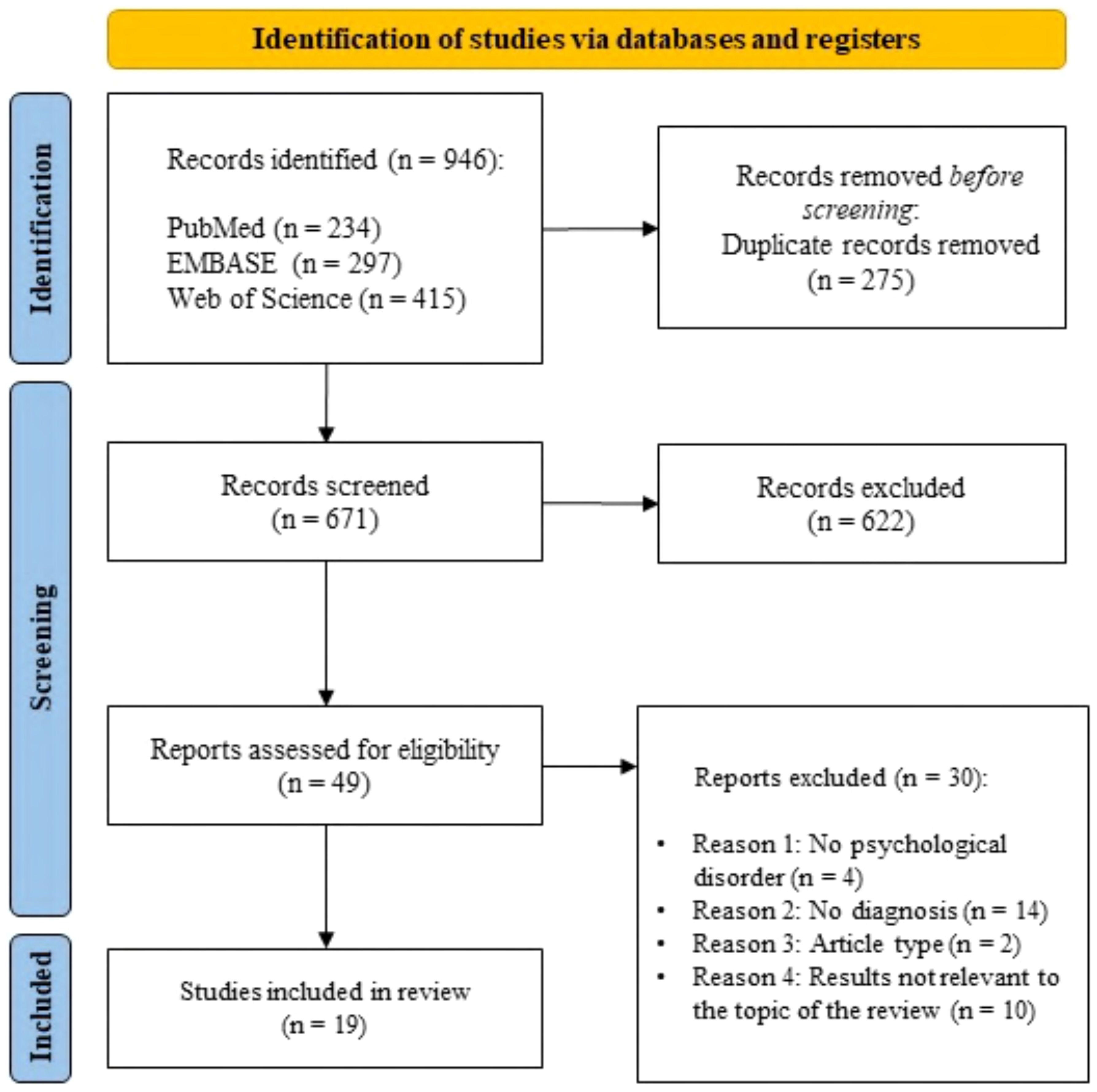

This systematic review was produced as stated by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (50). The PRISMA flowchart of the study selection is described in Figure 1.

2.2 Search strategy and study selection

The systematic search of the literature was conducted in three databases—PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science—to screen articles published in the 10 years prior to the research date (27 February 2024), which focused on the following areas of interest: “psychological intervention” and “affective touch and CT fiber stimulation.” After keywords selection, the search was performed within “Title and abstract” in PubMed and EMBASE, and within “All fields” in Web of Science. In the following, advanced searches for each database are reported:

– PubMed advanced search: ((psychological therap* OR psychological treatment* OR psychological intervention* OR psychotherapy OR psychiatric) AND (affective touch OR affiliative touch OR C tactile fiber* OR C-tactile OR tactile C)).

– EMBASE advanced search: (((psychological AND therap* OR psychological) AND treatment* OR psychological) AND intervention* OR ‘psychotherapy’/exp OR psychotherapy OR psychiatric) AND (‘affective touch’/exp OR ‘affective touch’ OR (affective AND (‘touch’/exp OR touch)) OR ‘affiliative touch’ OR (affiliative AND (‘touch’/exp OR touch)) OR ((‘c’/exp OR c) AND tactile AND fiber*) OR ‘c tactile’ OR ‘tactile c’ OR (tactile AND (‘c’/exp OR c))).

– Web of Science advanced search: (((psychological therap* OR psychological treatment* OR psychological intervention* OR psychotherapy OR psychiatric) AND (affective touch OR affiliative touch OR C tactile fiber* OR C-tactile OR tactile C))).

The screening was independently performed by two different authors.

2.3 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The PICOS model was used to determine the inclusion criteria:

– P (population): “individuals with a diagnosis of psychological disorder.”

– I (intervention): “CT fiber stimulation.”

– C (comparators): “individuals without a psychological diagnosis (i.e., control and placebo groups).”

– O (outcome): “psychological, neuromorphological, and biological differences in the effect of C-tactile fiber stimulation and the treatment effects of CT fiber stimulation.”

– S (study design): “observational studies, cohort studies, clinical trials, cross-sectional studies, and case–control studies.”

All human studies were included in this systematic review despite the study design. Conversely, all studies including animal models or in vitro and in silico studies were excluded. We excluded narrative reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and book chapters. In order to properly stick to the research question, we excluded articles that did not include patients whose diagnosis was stated and involved a validated method.

2.4 Risk of bias assessment

Two researchers (M.P. and D.D.) assessed the methodological quality of each included study using the Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2). This tool was designed to evaluate the risk of bias in randomized controlled trials (51). It consists of five key items, addressing five domains: selection bias, reporting bias, performance bias, attrition bias, and other potential sources of bias.

2.5 Data extraction

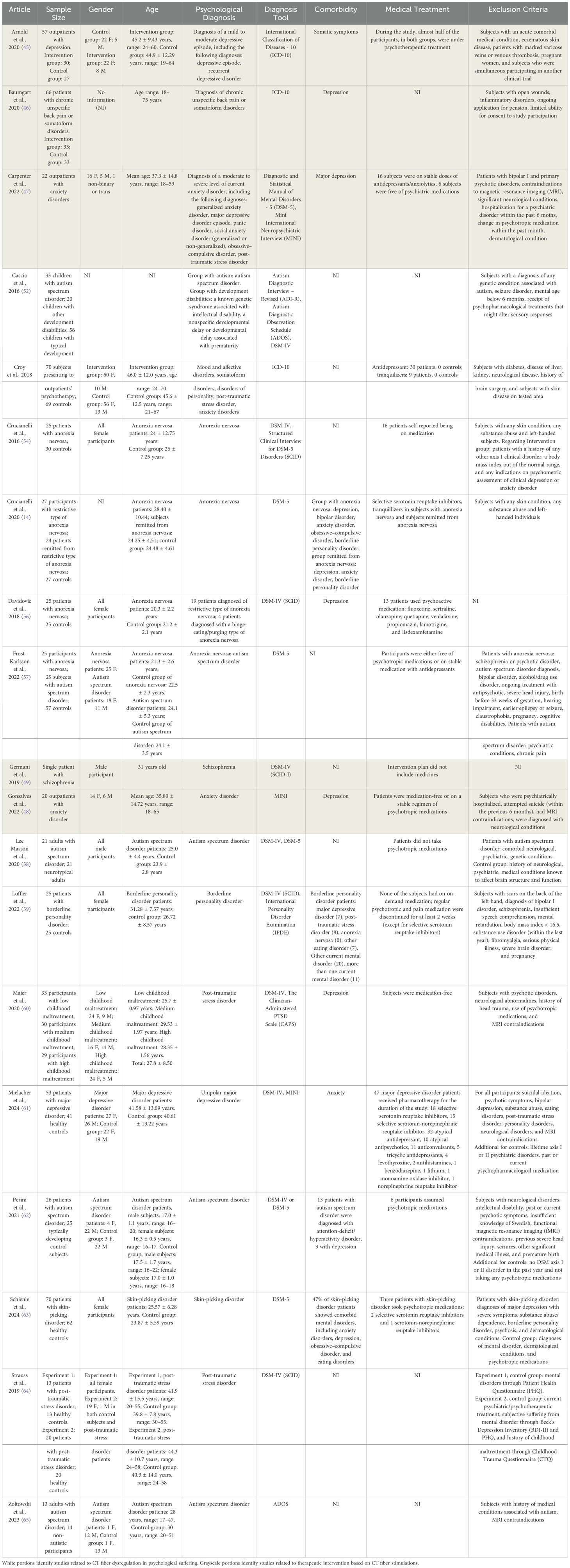

After defining the inclusion and exclusion criteria and having completed the selection of studies, data were extracted and summarized in Tables 1–5, reporting the following information:

– Description of all selected studies including sample size, gender, ethnicity, age, psychological diagnosis, diagnosis tool, comorbidity, medical treatment, and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

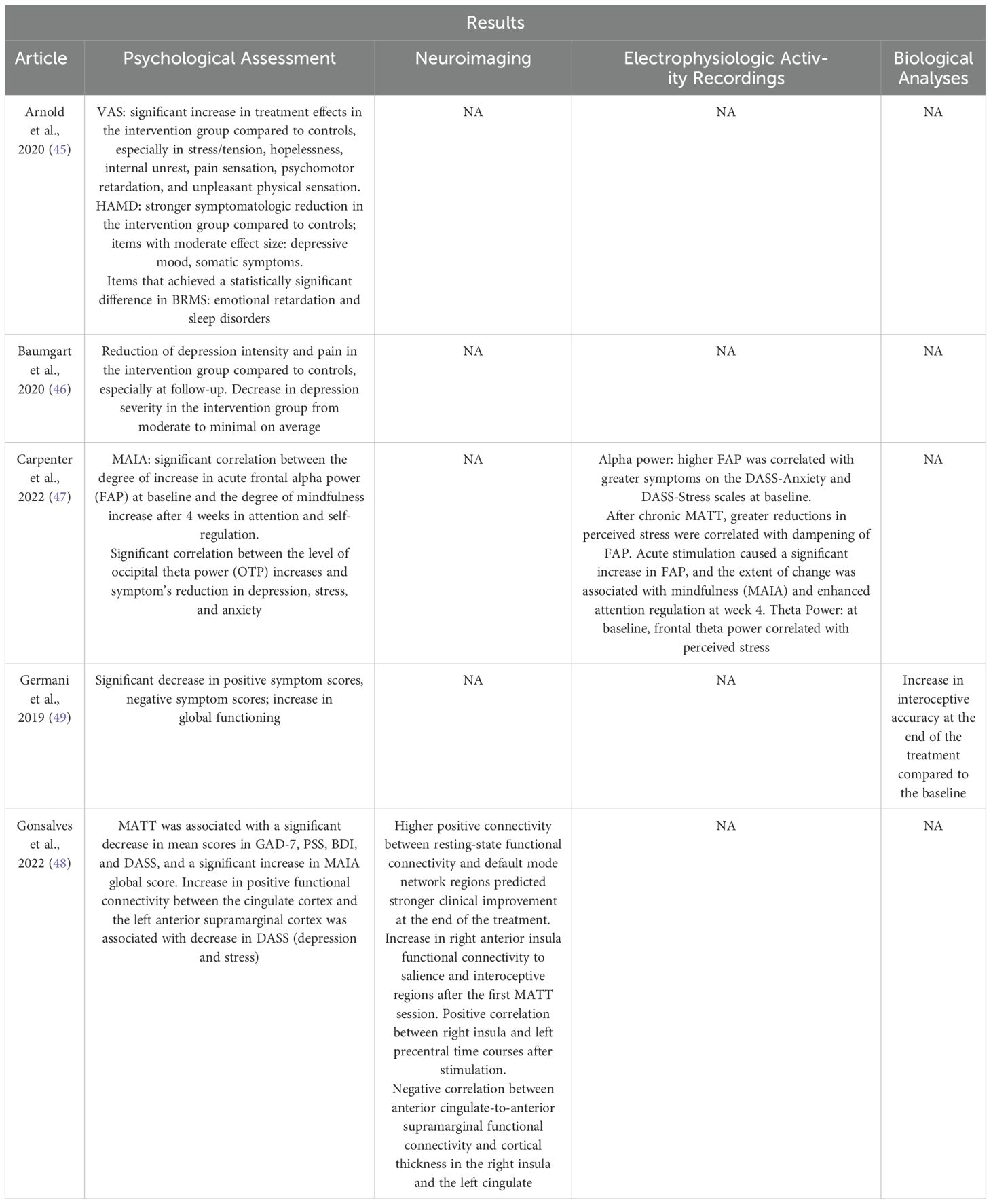

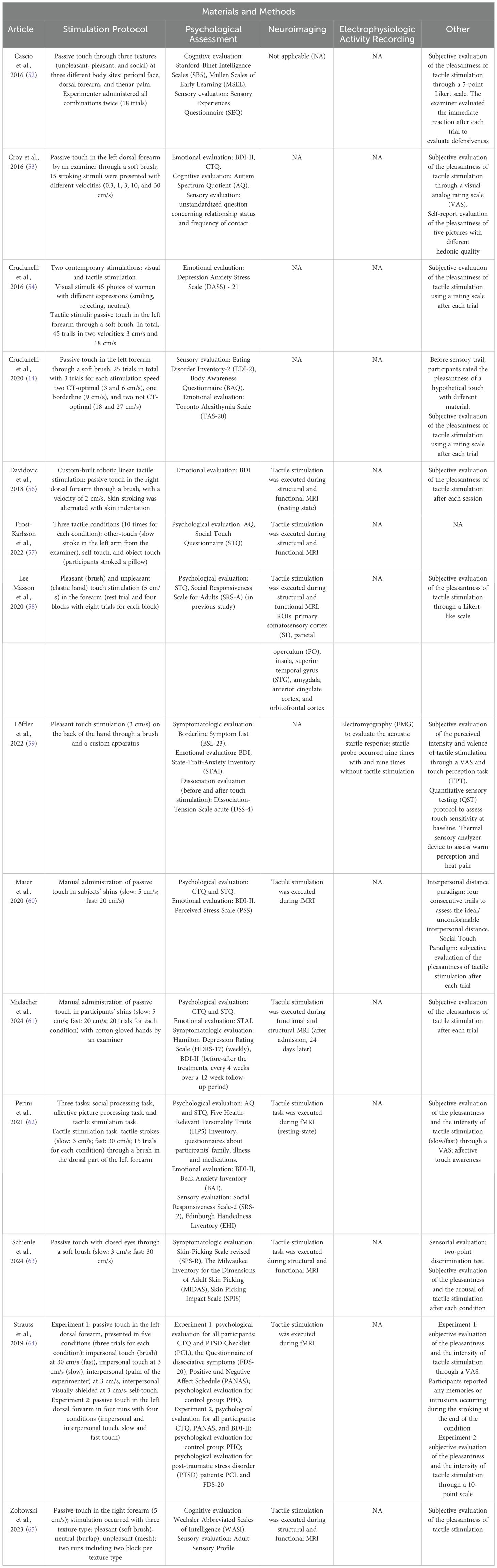

– Methodologies (Table 2) and results (Table 3) of studies evaluating CT fiber stimulation to assess potential CT fiber dysregulation in individuals with a diagnosis of psychological disorder. The tables include information regarding stimulation protocol, psychological assessment, neuroimaging analyses, electrophysiologic activity recordings, and other analyses (e.g., subjective evaluation of the pleasantness of tactile stimulation through Likert scale or a visual analog rating scale).

– Methodologies (Table 4) and results (Table 5) of studies in which CT fiber stimulation was used as psychological treatment. The tables include information regarding stimulation protocol, psychological assessment, neuroimaging analyses, electrophysiologic activity recordings, and biological analyses (e.g., heartbeat tracking).

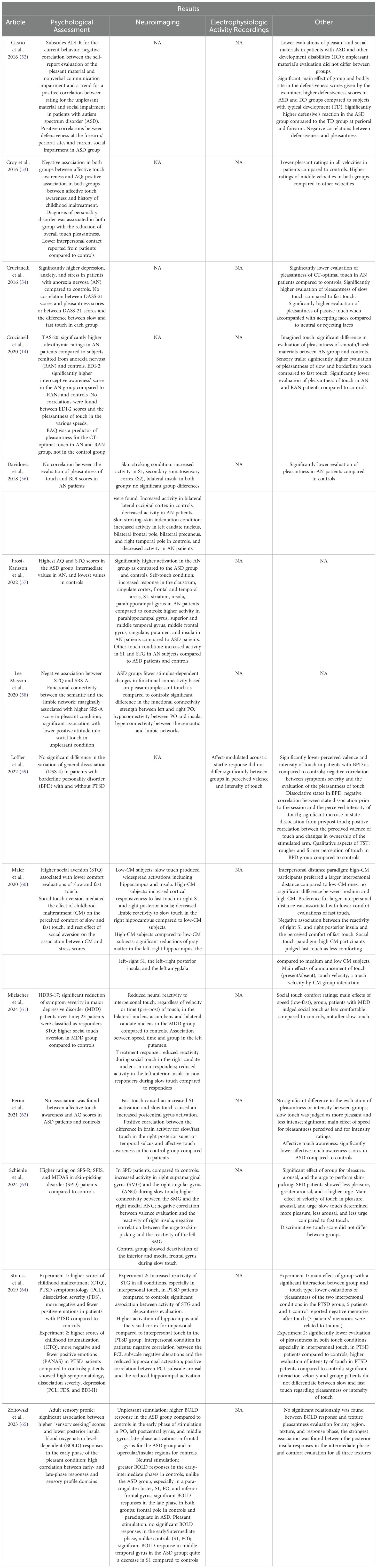

Table 2. Summary of the methodological approach of studies on CT fiber functionality to assess potential CT fiber dysregulation in individuals with a diagnosis of psychological disorder.

Table 3. Summary of the results of studies on CT fiber functionality to assess potential CT fiber dysregulation in individuals with a diagnosis of psychological disorder.

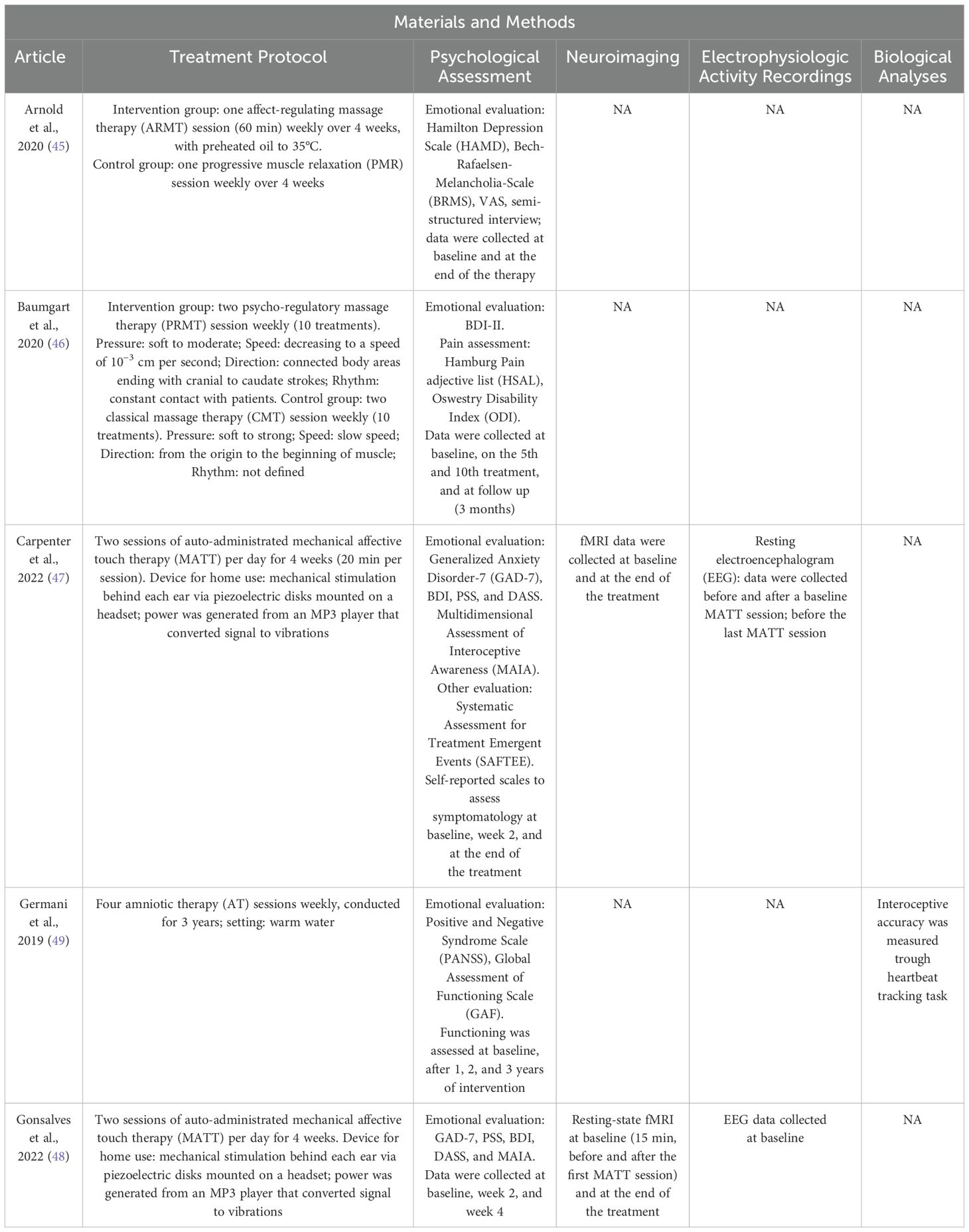

Table 4. Summary of the methodological approach of studies using CT fiber stimulation as a psychological treatment.

3 Results

3.1 Selected studies investigating the role of affective touch in psychological suffering

The bibliographic research offered a total of 946 articles that met the search criteria (Figure 1). PubMed search produced 234 articles, EMBASE search produced 297 results, and 415 articles were provided by Web of Science. After excluding 275 duplicate records, 671 papers were screened by reading the title and abstract; out of these, 622 articles were excluded and 49 publications were admitted for the full-text screening. After the second screening, 30 reports were discarded due to the inconsistency with our inclusion criteria. The remaining 19 articles were included in the present systematic review. Out of these, 14 studies primarily focus on an exploratory analysis of neurobiological and morphological aspects associated to CT fiber functionality in different psychopathological conditions (52–65). Furthermore, 5 studies focus on CT fiber stimulation as part of psychological treatment (45–49). The description of 19 studies is reported in Table 1.

3.2 The dysregulation of CT fibers in psychological suffering

The methods and results of analyses on CT fiber functionality to assess potential CT fiber dysregulation in patients suffering from various psychological disorders are summarized in Tables 2, 3.

3.2.1 Autism spectrum disorder

Based on a comprehensive literature screening, five studies have investigated the potential dysregulation of CT fibers in individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (52, 57, 58, 62, 65). These studies examined neuroimaging evidence (57, 58, 62, 65) and subjective perceptions of pleasantness (52, 58, 62, 65) in response to standardized tactile stimulation, employing various experimental protocols. Specifically, the studies differed in the tactile texture of stimulation and the velocity of touch. Researchers explored pleasant and unpleasant touch (52, 58, 65), as well as neutral touch using burlap fabric (65). Additionally, self-touch and object-touch (57), along with social-touch interactions (52, 57), were assessed.

Perini et al. (2021) (62) administered CT stimulations at velocities of 3 and 30 cm/s, while Zoltowski et al. (2023) (65) and Lee Masson et al. (2020) (58) employed a 5 cm/s velocity. In all studies, affective touch was applied to the participants’ forearm (57, 58, 62, 65), except for Cascio et al. (2016) (52), who stimulated three bodily sites characterized by varying levels of CT fiber innervation: the perioral face, dorsal forearm, and thenar palm.

Furthermore, the phenomenon of sensory defensiveness—characterized by heightened emotional reactions and hyperresponsiveness—was analyzed, revealing significantly greater defensive reactions in children with ASD and other developmental disabilities compared to control groups. In the ASD cohort, defensiveness reactions were particularly elevated in the perioral and forearm regions, which are densely innervated by CT fibers. Notably, defensiveness was negatively correlated with perceived pleasantness.

Lee Masson et al. (2020) (58) identified a negative correlation between the connectivity of the semantic network (i.e., lateral temporal lobe) and the limbic network (i.e., bilateral hippocampus and amygdala), as assessed via functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and attitudes toward social touch. These attitudes were evaluated using the Social Touch Questionnaire (STQ) and the Social Responsiveness Scale for Adults (SRS-A) (66). Specifically, the STQ assesses individuals’ perceptions of touch-related social interactions in daily life, particularly regarding the quality of caressing experiences. In neurotypical control subjects, stronger functional connectivity was observed between the parietal operculum (PO) and the right insula during pleasant touch. In contrast, individuals with ASD exhibited reduced modulation in these regions, characterized by hypo-connectivity between the PO and insula and hyper-connectivity between the semantic and limbic networks.

Perini et al. (2021) (62) examined subjective evaluations of pleasantness and perceived intensity in response to tactile stimulation, using these measures as proxies for affective touch awareness and its neural correlates. The analysis found no significant differences in comfort or intensity ratings between ASD and control participants. Across all groups, slow touch was rated as more pleasant and less intense than fast touch. However, only in neurotypical individuals did affective touch awareness positively correlate with neural responses in the right posterior superior temporal sulcus.

Zoltowski et al. (2023) (65) utilized fMRI to investigate blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) responses during tactile stimulation. In individuals with ASD, a heightened BOLD response was observed in the early phase of stimulation within the PO, left postcentral gyrus, and middle frontal gyrus during unpleasant touch. In contrast, neurotypical individuals exhibited a graded response pattern. Regarding neutral stimulation, participants with ASD showed no significant BOLD responses in the aforementioned areas until the late stimulation phase, whereas neurotypical subjects exhibited early-phase activation. At this later phase, participants with ASD demonstrated significant BOLD responses in the paracingulate cortex, while controls exhibited activity in the frontal pole. In response to pleasant touch, individuals with ASD displayed significant BOLD responses only in the late phase, with increased activation in the middle temporal gyrus and decreased activity in the S1 relative to controls. Furthermore, an inverse relationship was observed between early-phase responses to pleasant stimulation and sensory-seeking behaviors in the ASD group, as assessed using the Adult Sensory Profile (67).

Finally, one study (57) utilized fMRI to investigate self–other distinction during tactile stimulation in individuals with ASD, those with anorexia nervosa (AN), and neurotypical controls. In the ASD group, no regions exhibited increased BOLD activity compared to the AN and control groups, suggesting a potential alteration in the neural mechanisms underlying self–other differentiation in ASD.

3.2.2 Anorexia nervosa

The analysis of potential CT fiber dysregulation in patients diagnosed with AN identified four relevant studies (54–57). In all studies, patients with AN and healthy controls received CT fiber stimulation and subsequently rated the perceived pleasantness of the touch, except in Frost-Karlsson et al. (2022) (57). Additionally, in two studies, tactile stimulation was administered during fMRI scanning (56, 57).

In Frost-Karlsson et al. (2022) (57), neuroimaging data revealed that during self-touch, individuals with AN exhibited significantly higher activation in the claustrum, cingulate cortex, frontal and temporal regions, S1, striatum, insula, and parahippocampal gyrus compared to controls. Moreover, greater activation was observed in the parahippocampal gyrus, superior and middle temporal gyri, middle frontal gyrus, cingulate cortex, insula, and putamen in patients with AN compared to those with ASD. During other-touch conditions, subjects with AN showed significantly higher activity in S1 and the superior temporal gyrus compared to both patients with ASD and controls.

Davidovic et al. (2018) (56) also utilized fMRI to examine brain responses during CT fiber stimulation, which was administered via a linear tactile stimulator. Participants received several trials of passive touch on the right forearm at a velocity of 2 cm/s, interspersed with blocks of static skin indentation. Self-reported ratings of comfort during skin stroking revealed a significantly lower evaluation of pleasantness in patients with AN compared to controls, with no correlation to depression scores. Whole-brain analysis showed a significantly reduced response to skin stroking versus skin indentation in patients with AN compared to controls, specifically in the left caudate nucleus, bilateral frontal pole, bilateral precuneus, and right temporal pole. Additionally, patients with AN exhibited significantly decreased activation in the bilateral lateral occipital cortex in response to skin stroking, whereas controls demonstrated increased activity in this region during tactile stimulation.

Crucianelli et al. (2016) (54) investigated the interplay between visual and tactile stimulation. Participants underwent CT fiber stimulation on the forearm via brush strokes at two different velocities, while simultaneously viewing images of individuals displaying critical/rejecting expressions, neutral expressions, or smiling faces. The study aimed to determine whether the perceived pleasantness of touch was modulated by the emotional quality of the observed facial expression. Patients with AN, who exhibited significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress compared to controls, reported significantly lower comfort ratings in response to CT-optimal stimulation. In both groups, exposure to smiling faces enhanced the perceived pleasantness of touch compared to neutral or rejecting facial expressions.

Similarly, another study (55) reported significantly lower pleasantness ratings for touch in patients with AN compared to controls. This study investigated tactile anhedonia in individuals with AN, those recovered from AN, and healthy controls. Participants completed the Interoceptive Awareness subscale of the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 and the Body Awareness Questionnaire (BAQ) before undergoing CT fiber stimulation on the forearm at three different velocities: CT-optimal (3 cm/s), non-optimal (30 cm/s), and borderline (9 cm/s), classified as such given that CT-optimal stimulation typically falls within the 1–10 cm/s range (16). Patients with AN exhibited significantly higher interoceptive awareness compared to controls. Importantly, body awareness was identified as a predictor of perceived comfort in response to CT-optimal touch within the clinical group.

3.2.3 Post-traumatic stress disorder

The literature review identified three studies examining CT fiber stimulation in patients diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (53, 60, 64). In these studies, researchers administered passive touch to individuals with PTSD and healthy controls under different conditions, varying both the velocity and method of stimulation. Croy et al. (2016) (53) applied stimulation at 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 30 cm/s, while Maier et al. (2020) (60) utilized slow (5 cm/s) and fast (20 cm/s) velocities. Strauss et al. (2019) (64) conducted two experiments, exposing participants to combinations of impersonal and interpersonal touch, CT-optimal (3 cm/s) or non-optimal (30 cm/s) velocities, and self-touch. In two studies (60, 64), tactile stimulation was administered during fMRI scanning. All studies required participants to rate the perceived pleasantness of CT fiber stimulation. Additionally, Maier et al. (2020) (60) included an interpersonal distance paradigm to assess participants’ preferred interpersonal distance, while Strauss et al. (2019) (64) (Experiment 1) invited participants to report any memories evoked during touch stimulation.

In Maier et al. (2020) (60), the study sample comprised adults with varying levels (low, moderate, and high) of childhood maltreatment (CM). Participants were screened for lifetime psychiatric disorders using the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition) and for current PTSD using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. Individuals with high CM exhibited a preference for greater interpersonal distance and rated fast touch as significantly less pleasant compared to those with no or moderate CM. They also reported heightened discomfort during tactile stimulation, particularly in response to fast touch. This discomfort was associated with increased activation in the right S1 and posterior insula in response to fast touch, as well as reduced neural responses to slow touch in the right hippocampus. Additionally, significant reductions in gray matter volume were observed in the bilateral hippocampus, bilateral S1, bilateral posterior insula, and the left amygdala in participants with high CM.

Similarly, Strauss et al. (2019) (64) conducted two experiments with distinct participant groups, utilizing various psychological assessment tools. Across both experiments, the clinical groups exhibited significantly higher levels of PTSD symptomatology, CM, and dissociative symptoms compared to healthy controls. Moreover, the clinical groups reported experiencing fewer positive and more negative emotions than controls. In both experiments, all touch conditions were rated as less comfortable by the clinical group, with interpersonal touch receiving the most negative evaluation. In Experiment 1, one control participant and five individuals with PTSD reported intrusive memories during touch, three of which were trauma-related. In addition to the assessments conducted in Experiment 1, the second experiment found that PTSD patients exhibited high levels of depressive symptoms and reported perceiving touch as more intense. Furthermore, they did not differentiate between slow and fast touch in terms of pleasantness. In individuals with PTSD, touch aversion was associated with reduced hippocampal responses and increased activation in the superior temporal gyrus. Moreover, hippocampal response was negatively correlated with symptoms of negative affect and positively correlated with arousal symptoms.

Finally, Croy et al. (2016) (53) investigated CT fiber stimulation in patients recruited from an outpatient psychotherapy clinic and healthy controls. The clinical group comprised individuals diagnosed with various psychopathological conditions, including PTSD. Following CT fiber stimulation, patients rated touch as significantly less pleasant than controls. Consistent with previous findings, mid-range velocities, particularly CT-optimal stimulation (3 cm/s), were perceived as the most pleasant. The study further revealed that higher CM scores and lower autism spectrum quotient scores were associated with greater affective touch awareness. Although not statistically significant, diagnoses of PTSD and personality disorders contributed to this model.

3.2.4 Personality disorders

Two studies investigated CT fiber stimulation in patients diagnosed with personality disorders (PD) (53, 59). In the study conducted by Croy et al. (2016) (53), the authors reported a reduction in the overall perceived pleasantness of touch in the clinical group compared to healthy controls. Similarly, in the second study (59), participants received tactile stimulation at a CT-optimal velocity (3 cm/s) and were asked to rate the perceived pleasantness of the touch. This study included patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) and healthy controls.

Participants underwent psychological assessments and electromyographic recording to measure the acoustic startle response, which served as a physiological correlate of affective response. Patients with BPD reported significantly lower ratings of touch valence and intensity, describing the stimulation as rougher and firmer compared to controls. Moreover, in patients with BPD, symptom severity was inversely correlated with the perceived intensity of touch. A significant increase in dissociative state from pre- to post-tactile stimulation was also observed. Additionally, in the BPD group, the perceived valence of touch was positively correlated with changes in the sense of ownership of the stimulated arm.

3.2.5 Major depressive disorder

Two studies investigated CT fiber stimulation in patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) (53, 61). In Croy et al. (2016) (53), as previously discussed, the clinical group included aggregated data from individuals with various psychopathological conditions, without distinguishing specific diagnoses. However, the global analysis found no significant association between depression severity and affective touch awareness.

In contrast, the second study (61) specifically examined patients with MDD and healthy controls. Participants received manually administered passive touch at slow (5 cm/s) and fast (20 cm/s) velocities during fMRI sessions, conducted both at hospital admission and 24 days later. They were asked to rate the perceived comfort of the tactile stimulation. Most patients received pharmacotherapy throughout the study and periodically completed depression inventories to assess clinical improvement. Patients with MDD exhibited greater aversion to social touch, lower comfort ratings for tactile stimulation, and reduced neural responses to interpersonal touch in the nucleus accumbens, caudate nucleus, and putamen compared to healthy controls. Antidepressant treatment led to a reduction in clinical symptoms over time. However, patients who did not respond to therapy demonstrated persistently reduced activity in the caudate nucleus, anterior insula, and putamen.

3.2.6 Skin-picking disorder

The literature review identified only one study analyzing CT fiber stimulation in patients with skin-picking disorder (SPD) (63). The authors investigated tactile processing in individuals with SPD and healthy controls, who received passive touch at CT-optimal (3 cm/s) and non-optimal CT (30 cm/s) velocities during fMRI scanning. Patients with SPD scored higher on all scales compared to controls, reporting lower comfort, greater arousal, and a stronger urge to engage in skin-picking, with a significant main effect of touch velocity. Neuroimaging analyses revealed increased activity in the right supramarginal gyrus (SMG) and angular gyrus (ANG) in response to CT-optimal velocity touch. Additionally, greater connectivity was observed between the SMG and medial frontal gyrus, as well as between the ANG and SMG. A negative correlation emerged between insular activity and the positive valence of touch in patients with SPD compared to controls. Lastly, whereas healthy controls exhibited deactivation of the inferior and medial frontal gyri during CT-optimal velocity touch, this pattern was not observed in the SPD group.

3.3 Therapeutic potential of CT fiber stimulation in psychological suffering

The methodologies and results of investigations into therapeutic intervention based on CT fiber stimulation and affective touch in patients with psychopathological disorders are summarized in Tables 4, 5.

3.3.1 Risk of bias assessment

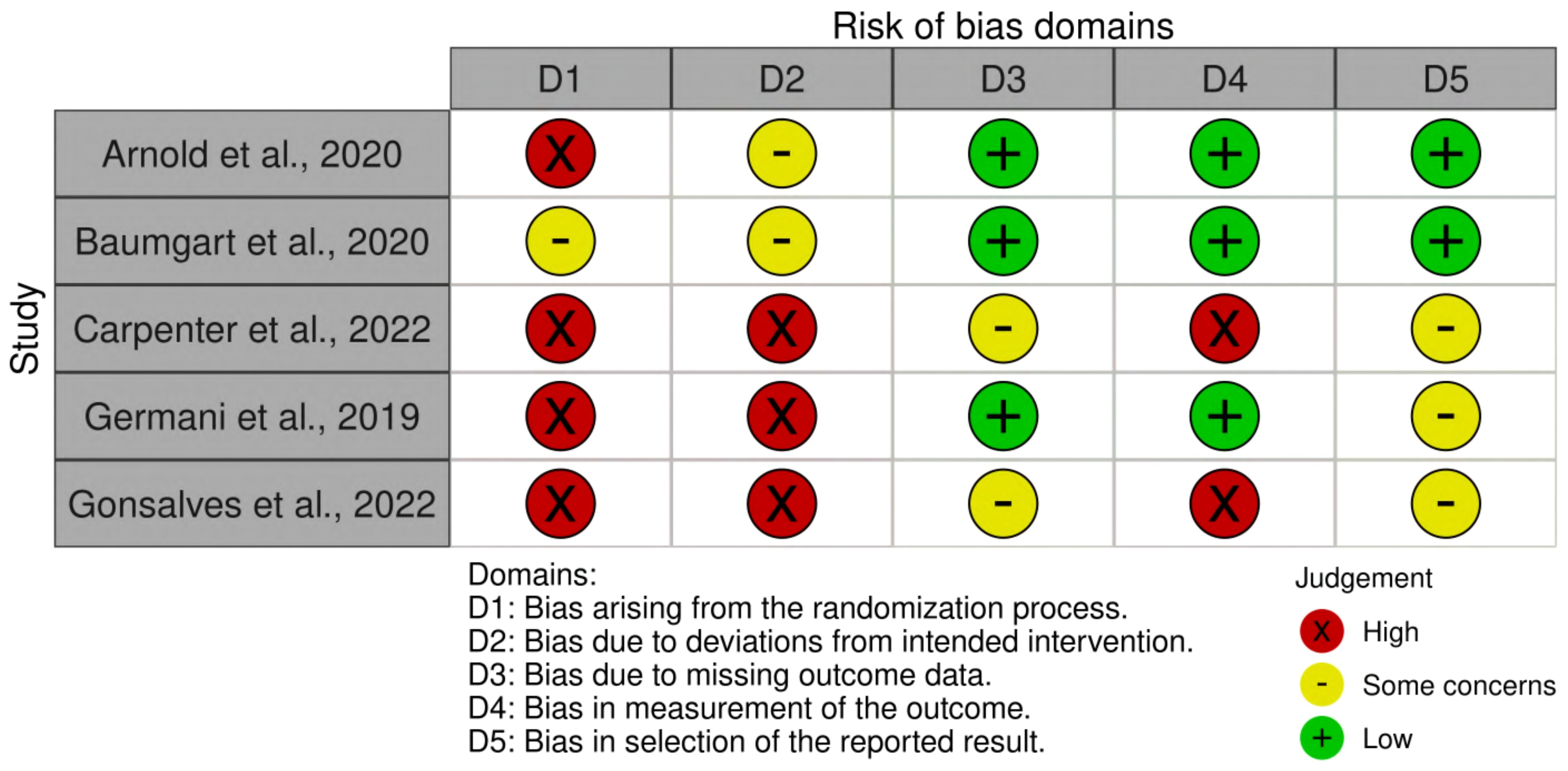

Risks of bias were judged based on the Cochrane guidance, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Risk of bias summary. Green represents low risk; red represents high risk; yellow represents some concerns.

A risk of bias assessment was conducted on studies proposing an intervention model based on affective touch, resulting in five articles (45–49). Two studies (45, 46) were rated as low risk of bias in domains 3, 4, and 5, leading to an overall low or moderate risk of bias. In contrast, three studies (47–49) were rated as high risk of bias in most domains, particularly Gonsalves et al. (48) and Carpenter et al. (47). These articles (47, 48) presented significant limitations, as they relied on the same sample without a control group, which prevented the randomization and double-blind control. Lastly, Germani et al. (49) conducted a single-case study, which is not fully applicable to the proposed quality appraisal. As a result, it showed some criticism, particularly in domains 1 and 2. Overall, the risk of bias assessment highlighted methodological strengths in some studies, while others exhibited significant limitations, underscoring the need for more rigorous research to strengthen the evidence on affective touch interventions.

3.3.2 Depressive disorder

Arnold et al. (2020) (45) used the ARMT, which was conducted in a quiet room using preheated massage oil (35°C), and involved a sequence of ventral, diagonal, and symmetrical gentle strokes administered in both supine and prone positions. The treatment consisted of one ARMT session (60 min) per week over four consecutive weeks. Regarding ARMT (45), the authors observed a greater reduction in depressive symptomatology in the intervention group compared to controls, as measured by the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) at the end of the treatment, especially in depressive mood and somatic symptoms. The visual analogue scale (VAS) for self-assessment showed significantly greater treatment effects in the intervention group compared to controls, with larger pre–post differences in stress/tension, hopelessness, internal unrest, pain sensation, psychomotor retardation, and unpleasant physical sensation. The Bech–Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale (BRMS) revealed significant differences in emotional retardation and sleep disorders at the end of the treatment; in particular, the ARMT group showed greater symptom reduction compared to the control group.

3.3.3 Somatoform disorder

Baumgart and colleagues (2020) (46) used the PRMT, which involved continuous whole-body massage, patient positioning (supine and prone), and the use of preheated oil. PRMT began with three partial massages before progressing to a full-body massage with different intensities of touch, ranging from soft to moderate pressure. The protocol included a full-body massage, ending with strokes from cranial to caudal areas while decreasing the velocity to 10−3 cm per second. Participants underwent two PRMT sessions (30 to 60 min each) per week over five consecutive weeks. In this study (46), the authors examined the effect of PRMT on somatoform and depressive symptoms using BDI-II. Pre–post assessment scores revealed a significant and sustained reduction in depression severity in the intervention group compared to controls, decreasing from a moderate to minimal level on average. Additionally, after completing PRMT, patients with somatoform disorder experienced sustained pain reduction compared to controls (46).

3.3.4 Anxiety disorder

The two studies focusing on anxiety disorders (47, 48) employed a home-based device that enabled participants to self-administer MATT, which delivers soft vibrations to the bilateral mastoid processes. The prototype included round ceramic piezoelectric actuators that converted the signal into mechanical stimulation behind the patients’ ears. These actuators were attached to a metal headset and powered by an MP3 signal generator. Carpenter et al. (2022) (47) chose an isochronic 10-Hz wave as a stimulation pattern, cycling 2 s on and 2 s off. Gonsalves et al. (2022) (48) tailored the stimulation intensity to participants’ preferences, selecting the level immediately above the threshold of perception. In both studies, participants were instructed to perform two self-administrated MATT sessions per day (20 min each) for four consecutive weeks. In both studies (47, 48), a significant decrease in mean symptom scores (47) was observed, along with an increase in Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) total scores in patients (47, 48). After MATT, scores on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), DASS, and BDI significantly decreased (48). Additionally, reductions in depression and stress DASS subscale scores were correlated with increased positive functional connectivity between the cingulate cortex and the left anterior supramarginal cortex after the completion of MATT (48). EEG data revealed that higher frontal alpha power (FAP) was associated with greater stress and anxiety DASS subscale scores at baseline (47). At the end of the treatment, greater reductions in perceived stress were correlated with dampening of FAP. Additionally, increased occipital theta power (OTP) was significantly associated with a reduction in depression, stress, and anxiety scores. Also, the extent of the increase in acute FAP at baseline correlated with the degree of mindfulness improvement at the end of the treatment in MAIA subscales, specifically in attention regulation and self-regulation (47). fMRI evidence revealed an increase in right anterior insula functional connectivity to salience and interoceptive regions following the first MATT session (48). At the end of the treatment, stronger functional connectivity between pain-processing regions (anterior insula, thalamus, and mid-cingulate area), anxiety regions (amygdala), and the default mode network was predictive of greater clinical improvement (48).

3.3.5 Schizophrenia

Germani and colleagues (2019) (49) proposed an AT, to be performed in warm water. Each patient was supported by a therapist, enabling the creation of an amniotic holding: a continuous fluctuation between skin-to-skin contacts and separation movements (49). The protocol provided four weekly AT sessions (90 min each), conducted over a period of 3 years. To assess the effect of AT in schizophrenia, researchers administered the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) (49). The authors reported a significant reduction in positive symptom scores, a decrease in negative symptomatology, and an improvement in global functioning. Furthermore, patients demonstrated higher levels of interoceptive accuracy at the end of the treatment compared to baseline.

4 Discussion

4.1 CT fiber dysregulation across psychological disorders: impact on touch perception, emotional processing, and clinical implications

We analyzed the potential CT fiber dysregulation, through psychological and functional evaluation, in patients with a diagnosis of psychological disorder (ASD, AN, PTSD, PD, MDD, and SPD). Taken together, many studies suggest an alteration of CT fiber sensory processing, resulting in lower perceived pleasantness rating of touch in subjects with psychopathological conditions (52–56, 59–61, 63, 64), while only one study (62) did not detect any difference in perceived comfort of touch between patients with ASD and healthy controls. Patients with ASD showed high defensiveness reaction (52), and subjects with MDD reported higher aversion to interpersonal touch (53, 61). Patients affected by PTSD revealed a higher estimation of the intensity of stroke (53, 60, 64), while patients with BPD were characterized by a lower evaluation of the intensity of touch, whose perception was rougher and firmer (53, 59). Subjects with SPD perceived the stimulation as less pleasant, more arousing, and evoking higher urge (63); lastly, a study underlined lower perceived comfort and tactile anhedonia as a persisting trait in individuals with AN and RAN, even during the recovery (54, 55). The heterogeneity in responses—ranging from heightened defensiveness in ASD and MDD to altered intensity perception in PTSD and BPD—raises intriguing questions about the underlying neurobiological mechanisms. One possibility is that these differences reflect disorder-specific alterations in somatosensory–affective integration. Moreover, the persistence of tactile anhedonia in AN and RAN, even during recovery, suggests that impairments in affective touch processing may not merely be symptomatic of acute pathology but could represent a stable trait-like feature, influencing long-term emotional regulation. This opens avenues for exploring whether interventions targeting affective touch—such as sensory-based therapies—could mitigate affective dysregulation in these conditions. Future research should investigate whether these alterations in CT fiber function contribute to broader patterns of social cognition and attachment, potentially influencing treatment responsiveness and prognosis. Patients affected by AN reported significantly lower activation in LOC, a hub of processing images of human bodies and self-representation (68). This alteration may reflect a disturbed body perception network. Moreover, a significant decrease in the left caudate nucleus’ activity in subjects with AN was found as compared to controls (56). Several selected studies corroborated the hypoactivation of the reward circuit and its components, involving patients diagnosed with AN (56), MDD (61), and PTSD (60, 64). According to Nestler and Carlezon (2006) (69), another study (61) investigated the association between reward network, affective touch, and MDD. The authors, through fMRI data, evidenced a decreased neural activation in the reward system in patients compared to controls, specifically in nucleus accumbens, caudate nucleus, and putamen, independently of the velocity of stimulation (61). Moreover, in responder patients, the hypoactivation of the nucleus accumbens and caudate nucleus persisted after the end of the antidepressant treatment. Those non-responder patients showed decreased activity in the caudate nucleus, putamen, and anterior insula during social touch both before and after the treatment. The alteration in neural processing of the reward network, combined with social aversion, can promote social isolation (61). The shared involvement of the reward circuit across AN, MDD, and PTSD highlights a potential transdiagnostic mechanism linking affective dysregulation and maladaptive social functioning. Future research should explore whether targeting reward system dysfunction could enhance treatment outcomes. Understanding the interplay between reward processing and affective touch may offer novel therapeutic insights, particularly for individuals resistant to conventional treatments. As regards patients with PTSD, Maier et al. (2020) (60) reported a sensory cortical (S1, posterior insula) hyperreactivity to discriminative touch (i.e., fast touch) and a limbic (hippocampus) hypoactivation to affective touch (i.e., slow touch) during fMRI. Hyperreactivity of the posterior insula may indicate increased salience detection, while hippocampal hypoactivation may impair affective touch encoding due to reward-associated cells (70). In another study (64), the authors suggested that the decreased hippocampal response may be associated with a coping mechanism based on voluntary suppression of unwanted memories (71). This deactivation was also connected with increased activity in the STG, as well as touch aversion (64). Moreover, a significant reduction in gray matter volume in the hippocampus, S1, insula, and amygdala in patients with PTSD was revealed (60). The amygdala is rated as a core region in processing CT fiber stimulation (26), and it is involved in social behavior, valence and salience of stimuli, and reward processing (72). In patients affected by ASD, the authors (58) revealed dysfunctional cortical communication in several regions implicated in the processing of affective touch, including alteration in STG, bilateral PO, and insula (73), via fMRI scanning. The authors suggest that these findings can be imputed to an insufficiency of stimulus-dependent modulation in regional connectivity patterns during the skin strokes (58). Patients with ASD exhibited hyper-connectivity between semantic and limbic networks, linked to social touch aversion, and hypo-connectivity between PO and the insula (58). Asaridou et al. (2024) (74) demonstrated that autistic individuals generally have heightened tactile sensitivity but found no autism-specific sex differences, implying that certain sensory traits might serve as universal autism markers. Osório et al. (2021) (75) revealed that autistic female patients exhibit more severe sensory processing difficulties, particularly in auditory and balance-related domains, which could aid in refining diagnostic criteria for female autism. These findings underscore the importance of considering sex differences in sensory and affective processing, as they have direct implications for both clinical practice and psychological research. In fact, Schirmer et al. (2022) (76) found that while men and women exhibit similar sensory pleasantness to touch, women display higher interpersonal comfort with unfamiliar touch and more negative affective associations, suggesting that touch may serve as a more relevant coping mechanism for them. The results suggest that diagnostic and therapeutic approaches should be tailored to account for sex-specific sensory profiles, particularly in autism, where female presentation is often overlooked. In SPD, greater insula activity correlated with lower affective touch ratings (63). Moreover, an increased SMG–ANG connectivity in patients was found, while controls showed deactivation in the inferior and middle frontal gyrus in comparison to patients with SPD. With SMG and ANG being two areas involved in attentional control, the authors hypothesized that the self-stimulation in SPD can be useful to redirect attentional resources from external stressors to inner sensations (63). Leknes and Tracey (2008) (77) evidenced a neurobiological similarity in affective somatosensory processing of pain and pleasure. This affinity is determined by the common involvement of areas such as the insula, amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and orbitofrontal cortex, as well as the common modulation of the opioid and the dopamine system. According to these findings, another study (59) suggested that both processes can be altered in BPD, in terms of lower sensitivity, according to a cortico-limbic (i.e., top-down modulation) dysregulation pathway (78). Löffler et al. (2022) (59) found a significant increase in state dissociation from pre- to post-stimulation in subjects with BPD, and the perceived valence of touch was related to the change in ownership of the stimulated arm. This association was not seen in the non-stimulated arm. The authors suggest that a decrease in body ownership experiences could be associated with an unpleasant perception of touch (59).

4.2 Neurobiological effects and clinical benefits of CT fiber stimulation in treating psychological disorders: from stress reduction to interoception enhancement

The previously mentioned findings contribute to the evaluation of CT fiber stimulation protocols (MATT, AT, ARMT, and PRMT) and their therapeutic potential in psychological suffering. Taken together, each protocol produced a decrease in symptom severity at the end of the treatment (45–49). In particular, two studies (47, 48) investigated MATT’s therapeutic effects via resting-state fMRI and EEG. MATT exploited insula activity and the associated interoceptive training through CT fiber stimulation. Through resting-state fMRI, Gonsalves et al. (2022) (48) evidenced that greater functional connectivity between the insula and the amygdala and the default mode network at baseline was related to a stronger decrease in stress and anxiety symptoms at the end of the treatment. Acutely (after a single MATT session), the authors observed higher insula connectivity to salience and interoceptive regions. However, interoceptive awareness, measured at the end of the treatment (MAIA), did not change significantly, suggesting that it may require a longer time window than the MATT treatment (48). Chronic effects of MATT (i.e., after 4 weeks of treatment) were detected, via fMRI data, in greater connectivity between the mid-cingulate cortex and the lateral subnetwork of the default mode network, resulting in a decrease in stress and anxiety scores (DASS) (48). In addition, a previous study revealed an association between the interoceptive awareness, promoted by mindfulness techniques, and an increase in FAP (79). Based on this evidence, another study (47) revealed a significant association between FAP and the symptoms’ severity at baseline, while after MATT completion, the decrease in FAP was related to the greatest symptoms’ reduction, suggesting a ceiling effect. In line with the previous study, Germani et al. (2019) (49) focused on the key role of the posterior insula in interoception (80) as well as in identification–separation processes (i.e., self–other distinction) (49). The authors evinced a progressive implementation in global functioning and a decline in positive and negative symptoms during a 3-year-long AT. Moreover, the interoceptive accuracy, measured through heartbeat tracking task, was enhanced at the end of the treatment, suggesting a potential tool for reducing self-disorder in patients who have been diagnosed with schizophrenia (49). Similarly, applying the ARMT protocol, Arnold et al. (2020) (45) observed a significant decrease in depressive symptomatology in subjects with MDD as compared to controls, with larger differences in internal unrest, unpleasant physical sensation, pain sensation, and stress. The authors identified the therapeutic potential of ARMT in insula activation, able to normalize a disturbed interoception (81). A previous study (18) linked gentle touch to oxytocin release and lower cortisol, supporting reduced stress scores (45). Interestingly, a previous study (82) observed an increase in oxytocin levels and a reduction of adrenocorticotropin hormone as a result of massage therapy. Besides insula activation, CT fiber stimulation is also associated with the concomitant response of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) directly linked to the paraventricular nucleus, responsible for the release of oxytocin (83). Baumgart et al. (2020) (46) explored CT fiber stimulation to reduce pain and comorbid depressive symptoms in somatoform disorder. Through the PRMT’s application, the authors obtained significant and continuous improvement in the depressive symptomatology in subjects with somatoform disorder, as well as a long-term effect on pain reduction (46). In addition, according to their projections to the amygdala, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex (84), oxytocin neurons may act through the neuromodulation of socio-emotional factors (stress and anxiety), which are known to influence pain perception (85).

5 Limitations

The present review highlights several limitations that should be considered to improve future research on affective touch in alleviating psychological distress. The first concern regards the limited number of studies available and the small sample sizes, which impact the reproducibility of findings and their applicability across different clinical populations. To further analyze the efficacy of affective touch interventions, it should be mandatory to expand the research with larger-scale studies. Another significant limitation is the heterogeneity of the psychological disorders that are characterized by distinct neurobiological and psychological mechanisms. Psychopathological differences and factors such as age, gender, cultural background, medication use, and comorbid conditions may strongly impact their response to affective touch and introduce potential confounding effects that can obscure the true impact of CT fiber stimulation. Moreover, the use of different protocols of stimulation complicates the comparability of findings and the identification of a comprehensive therapeutic approach even more. Moreover, this complicates the isolation of the specific effects of CT fiber stimulation. A key limitation of this study is the variability in methodological rigor among the included articles, as highlighted by the risk of bias assessment. While some studies demonstrated a low to moderate risk of bias, others presented significant methodological weaknesses, such as the absence of a control group, lack of randomization, and reliance on single-case designs. These limitations hinder the generalizability of the findings and emphasize the need for future research employing more robust study designs. The use of a more systematic approach characterized by standardized intervention guidelines (ensuring consistency in session duration, frequency, and intensity) could enhance the evaluation of the potential beneficial effects of affective touch in psychological disorders. The majority of existing studies focus on the short-term effects of affective touch, leaving its long-term potential effects unexplored. It could be useful to improve the research on this topic to build longitudinal studies with extended follow-up periods to evaluate if the observed beneficial effects persists over time. Despite the growing interest in the potential benefits of affective touch, the knowledge on the interactions of CT fiber stimulation with brain networks remains incomplete. While existing lines of evidence support the involvement of key regions such as the insula, amygdala, and reward circuitry, the precise pathways and the mechanisms through which affective touch exerts its effects are still not fully described yet. In addition, genetic and epigenetic influences on touch perception and response could offer insights into individual differences in affective touch. Furthermore, subjective effects associated with affective touch in emotional and cognitive dimensions when considering its potential therapeutic applications. By addressing these limitations, the field could progress, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of affective touch as a therapeutic tool. This will help to establish new clinical protocols of affective touch and expand its potential as a non-invasive intervention for individuals experiencing psychological distress.

6 Conclusion

This review explored the role of affective touch in psychological disorders, focusing on the potential modulation of CT fiber-mediated somatosensory processing. The evidence suggests that individuals diagnosed with psychiatric conditions tend to exhibit altered sensory perception, often reporting reduced perceived pleasantness of touch compared to healthy controls. These differences are attributed to disruptions in interoceptive processing and limbic system functioning.

In light of these findings, the review evaluated existing psychological interventions leveraging CT fiber stimulation. Despite methodological heterogeneity across the reviewed studies, a consensus emerged on the beneficial effects of affective touch therapies in reducing symptom severity and enhancing interoception in a wide range of psychological conditions.

Given the safety of these interventions and the current paucity of research, further studies are needed to explore their neuromodulatory effects and therapeutic potential, particularly in psychosis. Individuals with psychotic disorders often exhibit structural and functional alterations in the insular cortex, impairments in self–other differentiation, diminished interoceptive accuracy, attachment disturbances, and dysregulated stress responses. Affective touch may offer therapeutic benefits by modulating these key processes, warranting further investigation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MPa: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DD: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MPe: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by University of Perugia (to DL and CM).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor GB declared a shared affiliation with the author DC secondary affiliation at the time of review.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Dunbar RIM. The social role of touch in humans and primates: Behavioural function and neurobiological mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2010) 34:260–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.07.001

2. Triscoli C, Croy I, Steudte-Schmiedgen S, Olausson H, Sailer U. Heart rate variability is enhanced by long-lasting pleasant touch at CT-optimized velocity. Biol Psychol. (2017) 128:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.07.007

3. Peciccia M. Affiliative touch, sense of self and psychosis. Front Psychiatry. (2024) 15:1497724. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1497724

4. Beebe B, Jaffe J, Markese S, Buck K, Chen H, Cohen P, et al. The origins of 12-month attachment: A microanalysis of 4-month mother–infant interaction. Attachment Hum Dev. (2010) 12:3–141. doi: 10.1080/14616730903338985

5. Walker SC, Trotter PD, Swaney WT, Marshall A, Mcglone FP. C-tactile afferents: Cutaneous mediators of oxytocin release during affiliative tactile interactions? Neuropeptides. (2017) 64:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2017.01.001

6. Feldman R. Oxytocin and social affiliation in humans. Hormones Behav. (2012) 61:380–91. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.01.008

7. Walker SC, McGlone FP. The social brain: neurobiological basis of affiliative behaviours and psychological well-being. Neuropeptides. (2013) 47:379–93. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2013.10.008

8. Feldman R, Gordon I, Schneiderman I, Weisman O, Zagoory-Sharon O. Natural variations in maternal and paternal care are associated with systematic changes in oxytocin following parent–infant contact. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2010) 35:1133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.01.013

9. Peciccia M, Buratta L, Ardizzi M, Germani A, Ayala G, Ferroni F, et al. Sense of self and psychosis, part 1: Identification, differentiation and the body; A theoretical basis for amniotic therapy. Int Forum Psychoanalysis. (2022) 31:226–36. doi: 10.1080/0803706X.2021.1990401

10. Fairhurst MT, Löken L, Grossmann T. Physiological and behavioral responses reveal 9-month-old infants’ Sensitivity to pleasant touch. Psychol Sci. (2014) 25:1124–31. doi: 10.1177/0956797614527114

11. McGlone F, Wessberg J, Olausson H. Discriminative and affective touch: sensing and feeling. Neuron. (2014) 82:737–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.001

12. Olausson H, Lamarre Y, Backlund H, Morin C, Wallin BG, Starck G, et al. Unmyelinated tactile afferents signal touch and project to insular cortex. Nat Neurosci. (2002) 5:900–4. doi: 10.1038/nn896

13. (Bud) Craig DA. How do you feel — now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2009) 10:59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555

14. Crucianelli L, Filippetti ML. Developmental perspectives on interpersonal affective touch. Topoi. (2020) 39:575–86. doi: 10.1007/s11245-018-9565-1

15. Olausson H, Wessberg J, Morrison I, McGlone F, Vallbo Å. The neurophysiology of unmyelinated tactile afferents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2010) 34:185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.011

16. Essick GK, James A, McGlone FP. Psychophysical assessment of the affective components of non-painful touch. NeuroReport. (1999) 10:2083. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199907130-00017

17. Meijer LL, Baars W, Chris Dijkerman H, Ruis C, van der Smagt MJ. Spatial factors influencing the pain-ameliorating effect of CT-optimal touch: a comparative study for modulating temporal summation of second pain. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:2626. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-52354-3

18. Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Cortisol decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. Int J Neurosci. (2005) 115:1397–413. doi: 10.1080/00207450590956459

19. Hardin JS, Jones NA, Mize KD, Platt M. Parent-training with kangaroo care impacts infant neurophysiological development & Mother-infant neuroendocrine activity. Infant Behav Dev. (2020) 58:101416. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2019.101416

20. Vittner D, McGrath J, Robinson J, Lawhon G, Cusson R, Eisenfeld L, et al. Increase in oxytocin from skin-to-skin contact enhances development of parent–infant relationship. Biol Res For Nurs. (2018) 20:54–62. doi: 10.1177/1099800417735633

21. Della Longa L, Dragovic D, Farroni T. In touch with the heartbeat: newborns’ Cardiac sensitivity to affective and non-affective touch. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:2212. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052212

22. Menin D, Aureli T, Dondi M. Two forms of yawning modulation in three months old infants during the Face to Face Still Face paradigm. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0263510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263510

23. DiMercurio A, Connell JP, Clark M, Corbetta D. A naturalistic observation of spontaneous touches to the body and environment in the first 2 months of life. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:2613. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02613

24. Della Longa L, Filippetti ML, Dragovic D, Farroni T. Synchrony of caresses: does affective touch help infants to detect body-related visual–tactile synchrony? Front Psychol. (2020) 10:2944. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02944

25. Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2002) 3:655–66. doi: 10.1038/nrn894

26. Gordon I, Voos AC, Bennett RH, Bolling DZ, Pelphrey KA, Kaiser MD. Brain mechanisms for processing affective touch. Hum Brain Mapp. (2013) 34:914–22. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21480

27. Ardizzi M, Ambrosecchia M, Buratta L, Ferri F, Peciccia M, Donnari S, et al. Interoception and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Front Hum Neurosci. (2016) 10:379. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00379

28. Ardizzi M, Ambrosecchia M, Buratta L, Ferri F, Ferroni F, Palladini B, et al. The motor roots of minimal self disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2020) 218:302–3. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.03.007

29. Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Öhman A, Dolan RJ. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat Neurosci. (2004) 7:189–95. doi: 10.1038/nn1176

30. Jönsson EH, Kotilahti K, Heiskala J, Wasling HB, Olausson H, Croy I, et al. Affective and non-affective touch evoke differential brain responses in 2-month-old infants. NeuroImage. (2018) 169:162–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.12.024

31. Pirazzoli L, Lloyd-Fox S, Braukmann R, Johnson MH, Gliga T. Hand or spoon? Exploring the neural basis of affective touch in 5-month-old infants. Dev Cogn Neurosci. (2019) 35:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.06.002

32. Tuulari JJ, Scheinin NM, Lehtola S, Merisaari H, Saunavaara J, Parkkola R, et al. Neural correlates of gentle skin stroking in early infancy. Dev Cogn Neurosci. (2019) 35:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.10.004

33. Dozier M, Higley E, Albus KE, Nutter A. Intervening with foster infants’ caregivers: Targeting three critical needs. Infant Ment Health Journal: Infancy Early Childhood. (2002) 23:541–54. doi: 10.1002/imhj.10032

34. Montagu A. Touching: The Human Significance of the Skin. 3rd edition. New York: William Morrow Paperbacks (1986).

35. Spitz RA. Hospitalism; an inquiry into the genesis of psychiatric conditions in early childhood. Psychoanal Study Child. (1945) 1(1):53–74. doi: 10.1080/00797308.1945.11823126

36. Wilbarger J, Gunnar M, Schneider M, Pollak S. Sensory processing in internationally adopted, post-institutionalized children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2010) 51:1105–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02255.x

38. Mueller SM, Winkelmann C, Grunwald M. Human Touch in Healthcare: Textbook for Therapy, Care and Medicine. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer (2023). doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-67860-2

39. Olausson H, Wessberg J, Morrison I, McGlone F eds. Affective Touch and the Neurophysiology of CT Afferents. New York, NY: Springer (2016). doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6418-5

40. Peciccia M, Mazzeschi C, Donnari S, Buratta L. A sensory-motor approach for patients with a diagnosis of psychosis. Some data from an empirical investigation on amniotic therapy. Psychosis. (2015) 7:141–51. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2014.926560

41. Peciccia M, Germani A, Ardizzi M, Buratta L, Ferroni F, Mazzeschi C, et al. Sense of self and psychosis, part 2: A single case study on amniotic therapy. Int Forum Psychoanalysis. (2022) 31:237–48. doi: 10.1080/0803706X.2021.1990402

42. McGlone F, Uvnäs Moberg K, Norholt H, Eggart M, Müller-Oerlinghausen B. Touch medicine: bridging the gap between recent insights from touch research and clinical medicine and its special significance for the treatment of affective disorders. Front Psychiatry. (2024) 15:1390673. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1390673

43. Zhang Y, Duan C, Cheng L, Li H. Effects of massage therapy on preterm infants and their mothers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Pediatr. (2023) 11:1198730. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1198730

44. Karimi F, Abolhassani M, Ghasempour Z, Gholami A, Rabiee N. Comparing the effect of kangaroo mother care and massage on preterm infant pain score, stress, anxiety, depression, and stress coping strategies of their mothers. J Pediatr Perspect. (2021) 9:14508–19. doi: 10.22038/ijp.2020.50006.3990

45. Arnold MM, Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Hemrich N, Bönsch D. Effects of psychoactive massage in outpatients with depressive disorders: A randomized controlled mixed-methods study. Brain Sci. (2020) 10:676. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10100676

46. Baumgart SB-E, Baumbach-Kraft A, Lorenz J. Effect of psycho-regulatory massage therapy on pain and depression in women with chronic and/or somatoform back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Brain Sci. (2020) 10:721. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10100721

47. Carpenter LL, Kronenberg EF, Tirrell E, Kokdere F, Beck QM, Temereanca S, et al. Mechanical affective touch therapy for anxiety disorders: feasibility, clinical outcomes, and electroencephalography biomarkers from an open-label trial. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:877574. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.877574

48. Gonsalves MA, Beck QM, Fukuda AM, Tirrell E, Kokdere F, Kronenberg EF, et al. Mechanical affective touch therapy for anxiety disorders: effects on resting state functional connectivity. Neuromodulation: Technol at Neural Interface. (2022) 25:1431–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neurom.2021.10.007

49. Germani A, Ambrosecchia M, Buratta L, Peciccia M, Mazzeschi C, Gallese V. Constructing the sense of self in psychosis using the amniotic therapy: a single case study. Psychosis. (2019) 11:277–81. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2019.1618381

50. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

51. Eldridge S, Campbell M, Campbell M, Dahota A, Giraudeau B, Higgins J, et al. Revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2.0): additional considerations for cluster-randomized trials. Cochrane Methods Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2016) 10(suppl 1).

52. Cascio CJ, Lorenzi J, Baranek GT. Self-reported pleasantness ratings and examiner-coded defensiveness in response to touch in children with ASD: effects of stimulus material and bodily location. J Autism Dev Disord. (2016) 46:1528–37. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1961-1

53. Croy I, Geide H, Paulus M, Weidner K, Olausson H. Affective touch awareness in mental health and disease relates to autistic traits – An explorative neurophysiological investigation. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 245:491–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.09.011

54. Crucianelli L, Cardi V, Treasure J, Jenkinson PM, Fotopoulou A. The perception of affective touch in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 239:72–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.078

55. Crucianelli L, Demartini B, Goeta D, Nisticò V, Saramandi A, Bertelli S, et al. The anticipation and perception of affective touch in women with and recovered from anorexia nervosa. Neuroscience. (2021) 464:143–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.09.013

56. Davidovic M, Karjalainen L, Starck G, Wentz E, Björnsdotter M, Olausson H. Abnormal brain processing of gentle touch in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. (2018) 281:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2018.08.007

57. Frost-Karlsson M, Capusan AJ, Perini I, Olausson H, Zetterqvist M, Gustafsson PA, et al. Neural processing of self-touch and other-touch in anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum condition. NeuroImage: Clin. (2022) 36:103264. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2022.103264

58. Lee Masson H, Op de Beeck H, Boets B. Reduced task-dependent modulation of functional network architecture for positive versus negative affective touch processing in autism spectrum disorders. NeuroImage. (2020) 219:117009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117009

59. Löffler A, Kleindienst N, Neukel C, Bekrater-Bodmann R, Flor H. Pleasant touch perception in borderline personality disorder and its relationship with disturbed body representation. bord Pers Disord emot dysregul. (2022) 9:3. doi: 10.1186/s40479-021-00176-4

60. Maier A, Gieling C, Heinen-Ludwig L, Stefan V, Schultz J, Güntürkün O, et al. Association of childhood maltreatment with interpersonal distance and social touch preferences in adulthood. AJP. (2020) 177:37–46. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19020212

61. Mielacher C, Scheele D, Kiebs M, Schmitt L, Dellert T, Philipsen A, et al. Altered reward network responses to social touch in major depression. psychol Med. (2024) 54:308–16. doi: 10.1017/S0033291723001617

62. Perini I, Gustafsson PA, Igelström K, Jasiunaite-Jokubaviciene B, Kämpe R, Mayo LM, et al. Altered relationship between subjective perception and central representation of touch hedonics in adolescents with autism-spectrum disorder. Transl Psychiatry. (2021) 11:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01341-7

63. Schienle A, Schlintl C, Wabnegger A. Brain mechanisms for processing caress-like touch in skin-picking disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2024) 274:235–43. doi: 10.1007/s00406-023-01669-9

64. Strauss T, Rottstädt F, Sailer U, Schellong J, Hamilton JP, Raue C, et al. Touch aversion in patients with interpersonal traumatization. Depression Anxiety. (2019) 36:635–46. doi: 10.1002/da.22914

65. Zoltowski AR, Failla MD, Quinde-Zlibut JM, Dunham-Carr K, Moana-Filho EJ, Essick GK, et al. Differences in temporal profile of brain responses by pleasantness of somatosensory stimulation in autistic individuals. Somatosensory Motor Res. (2023) 0:1–16. doi: 10.1080/08990220.2023.2294715

66. Lee Masson H, Pillet I, Amelynck S, Van De Plas S, Hendriks M, Op de Beeck H, et al. Intact neural representations of affective meaning of touch but lack of embodied resonance in autism: a multi-voxel pattern analysis study. Mol Autism. (2019) 10:39. doi: 10.1186/s13229-019-0294-0

67. Brown C, Tollefson N, Dunn W, Cromwell R, Filion D. The adult sensory profile: measuring patterns of sensory processing. Am J Occup Ther. (2001) 55:75–82. doi: 10.5014/ajot.55.1.75

68. Cazzato V, Mian E, Serino A, Mele S, Urgesi C. Distinct contributions of extrastriate body area and temporoparietal junction in perceiving one’s own and others’ body. Cognit Affect Behav Neurosci. (2015) 15:211–28. doi: 10.3758/s13415-014-0312-9

69. Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA. The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biol Psychiatry. (2006) 59:1151–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.018

70. Tryon VL, Penner MR, Heide SW, King HO, Larkin J, Mizumori SJY. Hippocampal neural activity reflects the economy of choices during goal-directed navigation. Hippocampus. (2017) 27:743–58. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22720

71. Anderson MC, Ochsner KN, Kuhl B, Cooper J, Robertson E, Gabrieli SW, et al. Neural systems underlying the suppression of unwanted memories. Science. (2004) 303:232–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1089504

72. Rutishauser U, Mamelak AN, Adolphs R. The primate amygdala in social perception - insights from electrophysiological recordings and stimulation. Trends Neurosci. (2015) 38:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.03.001

73. Kaiser MD, Yang DY-J, Voos AC, Bennett RH, Gordon I, Pretzsch C, et al. Brain mechanisms for processing affective (and nonaffective) touch are atypical in autism. Cereb Cortex. (2016) 26:2705–14. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv125

74. Asaridou M, Wodka EL, Edden RAE, Mostofsky SH, Puts NAJ, He JL. Could sensory differences be a sex-indifferent biomarker of autism? Early investigation comparing tactile sensitivity between autistic males and females. J Autism Dev Disord. (2024) 54:239–55. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05787-6

75. Osório JMA, Rodríguez-Herreros B, Richetin S, Junod V, Romascano D, Pittet V, et al. Sex differences in sensory processing in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. (2021) 14:2412–23. doi: 10.1002/aur.2580

76. Schirmer A, Cham C, Zhao Z, Lai O, Lo C, Croy I. Understanding sex differences in affective touch: Sensory pleasantness, social comfort, and precursive experiences. Physiol Behav. (2022) 250:113797. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2022.113797

77. Leknes S, Tracey I. A common neurobiology for pain and pleasure. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2008) 9:314–20. doi: 10.1038/nrn2333

78. Schmahl C, Bohus M, Esposito F, Treede R-D, Di Salle F, Greffrath W, et al. Neural correlates of antinociception in borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2006) 63:659–67. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.659

79. Lomas T, Ivtzan I, Fu CHY. A systematic review of the neurophysiology of mindfulness on EEG oscillations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2015) 57:401–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.09.018

80. Morrison I, Löken LS, Minde J, Wessberg J, Perini I, Nennesmo I, et al. Reduced C-afferent fibre density affects perceived pleasantness and empathy for touch. Brain. (2011) 134:1116–26. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr011

81. Eggart M, Queri S, Müller-Oerlinghausen B. Are the antidepressive effects of massage therapy mediated by restoration of impaired interoceptive functioning? A novel hypothetical mechanism. Med Hypotheses. (2019) 128:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.05.004

82. Morhenn V, Beavin LE, Zak PJ. Massage increases oxytocin and reduces adrenocorticotropin hormone in humans. Altern Ther Health Med. (2012) 18:11–8.

83. Bystrova K. Novel mechanism of human fetal growth regulation: a potential role of lanugo, vernix caseosa and a second tactile system of unmyelinated low-threshold C-afferents. Med Hypotheses. (2009) 72:143–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.09.033

84. Grinevich V, Knobloch-Bollmann HS, Eliava M, Busnelli M, Chini B. Assembling the puzzle: pathways of oxytocin signaling in the brain. Biol Psychiatry. (2016) 79:155–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.013

Keywords: C tactile afferent, psychological disorder, psychological treatment, affiliative touch, social touch, affective touch therapies

Citation: Papi M, Decandia D, Laricchiuta D, Cutuli D, Buratta L, Peciccia M and Mazzeschi C (2025) The role of affective touch in mental illness: a systematic review of CT fiber dysregulation in psychological disorders and the therapeutic potential of CT fiber stimulation. Front. Psychiatry 16:1498006. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1498006

Received: 18 September 2024; Accepted: 03 March 2025;

Published: 25 March 2025.

Edited by:

Giulia Ballarotto, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyReviewed by:

Isabella Lucia Chiara Mariani Wigley, University of Turku, FinlandLaura Clara Grandi, University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Papi, Decandia, Laricchiuta, Cutuli, Buratta, Peciccia and Mazzeschi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maurizio Peciccia, bWF1cml6aW8ucGVjaWNjaWFAdW5pcGcuaXQ=

Martina Papi

Martina Papi Davide Decandia

Davide Decandia Daniela Laricchiuta

Daniela Laricchiuta Debora Cutuli

Debora Cutuli Livia Buratta

Livia Buratta Maurizio Peciccia

Maurizio Peciccia Claudia Mazzeschi

Claudia Mazzeschi