- 1Department of Paediatrics, Khoo Teck Puat – National University Children’s Medical Institute, National University Hospital, National University Health System, Singapore, Singapore

- 2Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine , National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 3Department of Family Medicine, National University Health System, Singapore, Singapore

- 4Division of Family Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

Introduction: Bullying and victimization in adolescence is associated with mental health problems including depression. Depression in East Asian adolescents presents similarities and differences from that in Western adolescents. This review reports on the prevalence and psychosocial associations of bullying and depression in East Asian adolescents.

Methods: Electronic databases (Medline, and Embase) were searched for English language articles on bullying and its associations for a span of 10 years (1st January 2013 to 19th January 2024). Searches were limited to studies conducted in East Asia involving adolescents 10-19 years of age.

Results: Out of 1,231 articles initially identified, 65 full-text articles (consisting of 44 cross-sectional and 21 cohort studies) met the inclusion criteria and were included for qualitative synthesis & analysis. Prevalence rates of bullying ranged from 6.1% - 61.3% in traditional bullying victimization and 3.3% to 74.6% in cyberbullying victimization with higher rates in at-risk groups (e.g., adolescents with internet addiction). Psychosocial associations of bullying and depression which were similarly found in Western cultures include individual factors of coping style and gender; family factors of functioning and sibling relationships; and community factors of friendship and school-connectedness. In contrast, unique East Asian risk factors included being different (i.e., sexual minority status) and teachers as bullies.

Conclusion: Findings of this scoping review suggest that strong relationships within families, peers and the school community coupled with adolescents’ positive coping style are protective against the negative effects of bullying. Conversely, poor parent-child attachment in the midst of family dysfunction, poor engagement with peers and the school community together with low self-esteem predispose East Asian adolescents to depressive symptoms as a result of victimization. Similar to Western cultures, adolescents who are bully-victims and poly-victims are most vulnerable to depression. As a significant proportion of bullying occurred in school, future research could focus on a whole-school intervention approach to counter bullying.

1 Introduction

Depression is estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO) to occur in up to 2.8% of adolescents (1). Evidence suggests that bullying and victimization during early adolescence is associated with depression and suicidality during late adolescence, which may persist into adulthood (2, 3).

Bullying is understood to be one key risk factor for depression (4–7). Globally, about a third of adolescents aged 12 – 15 years have experienced bullying with suicide attempts twice as likely in adolescents who have experienced bullying compared to those who have not (8). While studies published in Western countries have shown a link between bullying, depression and suicidality in adolescents (5–7, 9), data from East Asian countries is sparse. Studies have shown many similarities in bullying patterns between Western and Eastern cultures (4, 8), but there is limited information on differences. The culture of East Asian countries does appear to impact the experience of school bullying especially in how it is experienced, prevented or mitigated (10). For instance, while students in England reported bullying in the playground from older and unfamiliar school mates, students in Japan and Korea reported bullying from classmates they knew well (8). A better understanding of the differences in bullying patterns can serve to inform practices to prevent and address bullying in East Asian cultures.

In East Asian countries, ‘collectivism’ which has its roots in Confucianism, provides the basis for how society functions. ‘Collectivism’ refers to a culture where the goals of the group are prioritized over the goals of individuals for the sake of harmony. Elements of collectivism include harmonious interpersonal relationships, group orientation, hierarchy, compliance with authority, and avoidance of peer and interpersonal conflicts” (11, 12). With its emphasis on hierarchy, power differences can be marked between adults in positions of authority and adolescents in their care. Adolescents may have little recourse when victimization originates from persons in authority (9). While East Asian culture promotes helping the vulnerable and weak within a group (13), the goals of maintaining harmony within a group may also mean that individuals who do not conform to the rules of the group may be exposed to correction by others within the group (14). The culture of East Asian countries does impact the way bullying is experienced or mitigated from differences in societal values or school systems (15). For instance, school bullying in collectivistic cultures may more likely be in the form of group bullying by social isolation compared to aggression in individualistic cultures (16) and more bullying may occur in hierarchical classrooms in Eastern cultures compared to more consultative classrooms in western cultures (15).

The emphasis on group goals in East Asian cultures during adolescence offers a contrast with personal goals of adolescence in Western cultures to achieve self-identity (Who am I)? and autonomy (Do my choices matter)? (17). Would the hierarchical norms and focus on harmonious interpersonal relationships mean that East Asian adolescents have fewer opportunities to receive support in the face of victimization, and stop bullying?

The aims of this review were to understand if there were unique aspects of East Asian, ‘collectivistic’, culture which would predispose adolescents to bullying and depression or protect them when bullying occurred. Countries/regions where the mainstream culture is Confucian-influenced (18) were selected for this study specifically including China, Japan, South Korea, Macau, Mongolia, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. The prevalence of bullying among adolescents in the cultures of East Asia and both risk and protective factors for bullying and development of depression in East Asian adolescents were investigated.

2 Methods

This review was conducted in line with the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews” (PRISMA-SCR) standardized reporting guidelines (see Appendix for checklist).

2.1 Information source and search strategy

A systematic search was conducted in 2 databases, MEDLINE (using the PubMed platform) and Embase for English language articles published from 1st January 2013 to 19th January 2024. These two databases were prioritized to yield a good scope of articles for the topic of interest. Searches were limited to studies conducted in populations from these countries: Japan, South Korea, Mongolia, China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Singapore.

To achieve the maximum sensitivity of the search strategy, we used combinations of free text and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms. The key concepts used for this search included “adolescent” (population) AND “bullying” (exposure) AND “depression” (outcome). Each concept was expanded, including the use of MeSH terms, with each term for the same concept searched using the Boolean operator “OR”, while the 3 main concepts combined with the Boolean operator “AND” for the overall search. The reference lists of included studies were also screened to identify other relevant studies.

2.2 Inclusion criteria

Studies which met the following inclusion criteria were included: (i) involved adolescents 10 – 19 years old (19) from East Asian countries, specifcially including China, HK, Mongolia, Macau, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and Singapore; (ii) examined traditional and/or cyberbullying (see Supplementary Table 1 for definitions) as the exposure; (iii) had psychosocial associations of bullying and development of depression as the outcome (Bullying was defined by its modalities - direct i.e., fighting and aggression versus indirect i.e., spreading rumours; types i.e., physical, relational, verbal; and forms i.e., traditional vs cyberbullying i.e., internet or social media based (20); single type versus poly-victimization involving multiple forms of bullying (see Supplementary Table 1 for definitions); and (iv) contained original epidemiological research i.e., cross-sectional and cohort studies.

2.3 Exclusion criteria

Studies which (i) involved East Asian expatriate adolescents; (ii) did not have outcomes related to bullying or bullying as a form of exposure; (iii) did not measure depression with standardized or validated scales; (iv) were conducted in South East Asian countries including Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Philippines, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Timor Leste where Confucianism is not practised widely (Singapore, which adopts a Confucian-informed culture, was not excluded); (v) were informal publications (such as commentaries, letters to the editor, editorials, meeting abstracts, theses or dissertations); (vi) were not published in English; (vii) lacked access to full texts; or (viii) were review papers, were excluded.

2.4 Study selection

Articles retrieved through the searches of the 2 databases were screened to remove duplicates. Four authors (G.W.S., N.T.J.H., N.S.H., L.Y.) independently assessed the abstracts and full-texts of articles identified from the searches to ensure they met the study inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus with the lead author (J.S.H.K.).

2.5 Data extraction

Four authors (M.S.B.M.S., G.W.S., N.T.J.H., N.S.H., L.Y.) extracted relevant data using a standard template including study author, country, study design, settings (e.g., urban or rural), sample size, participant characteristics (e.g., age), description of exposures and definitions, adjusted factors, outcomes (e.g., depression) and study design limitations.

2.6 Quality assessment

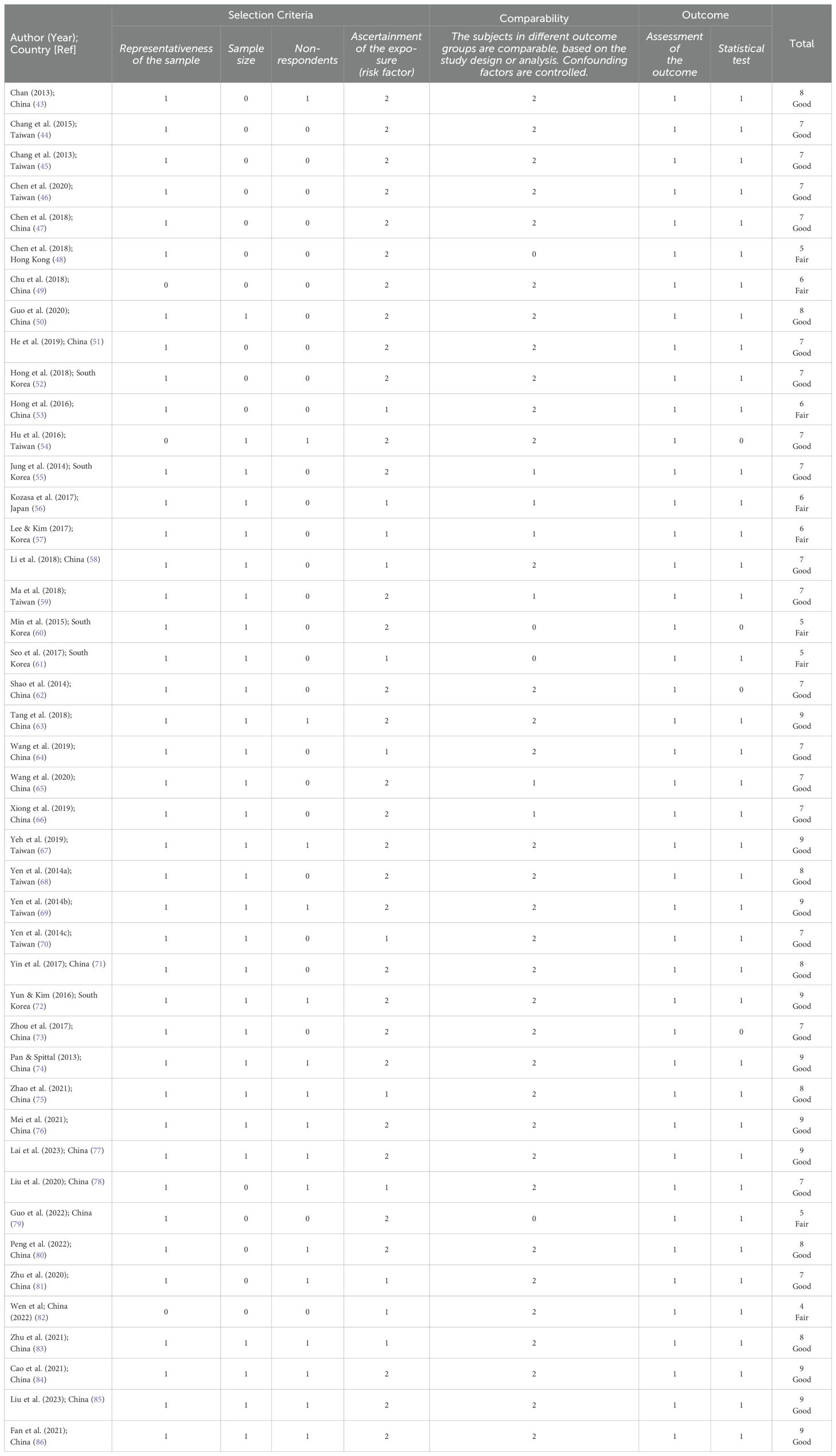

The risk of bias from cohort and cross-sectional studies included in this review were evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment (NOS) Scale which assesses the quality of non-randomized studies (21). High quality studies with a low risk of bias are scored between 7 and 9; fair quality studies with moderate-high risk of bias and low-quality studies with very high risk of bias are given scores between 4 and 6 and 0 and 3, respectively.

2.7 Synthesis of results

As this was a scoping review, a qualitative synthesis approach was adopted. More emphasis was placed on cohort and cross-sectional studies of “good” quality and low risk of bias (described as NOS score ≥ 7) with larger sample sizes (n > 1,000). P-values were represented as * where p < 0.001 was ***, p < 0.01 was ** and p < 0.05 was*.

3 Results

A total of 1,231 articles were identified from Medline (n = 764) and Embase (n = 467) databases. After removal of 518 duplicates, 714 records were eligible for further screening. Of these, 597 studies did not meet the eligibility criteria, leaving 117 studies for further evaluation. Of these, 51 were excluded for reasons such as unavailability of full-text and non-East Asian study population. Thus, a total of 65 studies were included in this review for analysis, comprising 21 cohort (22–42) studies [Taiwan (n = 3), South Korea (n = 2), China (n = 16), and 44 cross-sectional (43–86) studies [China (n = 27), HK (n = 1) Taiwan (n = 9), Korea (n = 6), and Japan (n = 1)]. The study screening and selection process is shown in Figure 1, while a detailed description of the included studies is provided in Table 1.

We assessed the quality of the included studies using the NOS. Findings are summarized in Tables 2, 3. Of the 44 cross-sectional studies with an average NOS score of 7.47 (range: 4 – 9); 35 had a low risk of bias (NOS score ≥ 7), 9 had an intermediate risk of bias (NOS score 4 – 6); with no studies having a high risk of bias (NOS score 0 – 3). Of the 21 cohort studies with an average NOS score of 6.28 (range: 3 – 8); 13 had a low risk of bias (NOS score ≥ 7), 7 had an intermediate risk of bias (NOS score 4 – 6) and 1 had a high risk of bias (NOS score 0 – 3).

Table 2. Quality Assessment for cross-sectional studies (n=45) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies.

3.1 Prevalence rates and patterns of bullying

Table 4 summarizes prevalence of bullying amongst adolescents in East Asian countries. The most commonly used bullying questionnaire was the adapted, revised, or translated version of Olweus Bully Victim Questionnaire (OBVQ), used in 25 studies.

For the 65 studies that were included, the sample size ranged from 194 to 18,341 participants. Of these, 3 studies were based on a large population study in children from 2009 – 2010 (n = 18,34) (43, 47, 81); and 2 studies were based on the Korean Child Youth Panel Survey (KCYPS) (n = 2,283) (36, 57).

Prevalence of bullying was reported as either in the preceding 6- or 12-month period, lifetime, or not reported. Twenty-three studies reported on the preceding 12-month prevalence which ranged from 6.1% to 61.3% in traditional bullying victimization and 3.3% to 74.6% in cyberbullying victimization. Lifetime prevalence of bullying victimization ranged from to 8.2% to 71.4%.

Rates of bullying victimization trended highest in the rural areas (range: 18.5 – 49.8%; average: 46%), intermediate in studies with urban and rural participants (range: 8.2 – 61.3%; average: 28%) and lowest in urban areas (range: 4.5 – 74.6%; average: 21.9%).

Children and adolescents who were perceived as ‘different’ to peers experienced higher rates of bullying, including children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (up to 49.8%) (45), Left Behind Children (LBC- children who are left behind when parents go to work) (up to 48.3%) (63) in rural studies, and those in the sexual minority (up to 26.5%) (75, 81). Males experienced more traditional bullying victimization than females (36, 43, 45, 47, 50, 51, 63, 75) except in one study (61) with higher rates in females (10.6% in females vs. 6.4% in males) (Table 4). Females also tended to experience more relational bullying while males experienced physical bullying more (72, 74) (Table 4).

Twelve papers addressed cyberbullying victimization in the preceding 12 months with prevalence rates (median: 18.6%) ranging from 3.3% (55) in South Korea to 74.6% (49) in Wuhan, China. Rates of cyber-victimization and cyberbullying more than doubled to 30% if the victim or bully had an internet addiction (44). One-fifth (22.2%) of Japanese cyberbullies were victims themselves i.e., cyberbully-victims (56). Cyberbullying rates were either higher in females (48, 56), or approaching those of male rates (17.2% in females vs. 19.6% in males) (45). In 4 studies, bullying victimization occurred more in older children (23, 31, 49, 71), while it was higher in younger children in only one study (43).

3.2 Depression assessment

The most commonly used depression scales were adaptions or translations of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) and Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC) (n = 28 studies).

3.3 Risk and protective factors for bullying and depression in East Asian adolescents

Many studies showed a correlation between peer victimization and the presence of depression or depressive symptoms in adolescents in East Asian cultures (24, 26, 45, 49, 51, 58, 59, 64, 65). In Taiwan, bully-victims reported the highest odds of depression (β = 8.46***) and lowest levels of self-esteem compared to the other two groups of victims only (β = 6.51***) or bully only (β = 1.23*) (68). Factors to be considered in bullying and depression are described below; whether they increased risk of bullying or depression or whether they were protective.

Results are presented as individual, family and community factors as well as vulnerable groups for comparison and description of the themes across the various studies (Table 5). Details of statistics, sample size, correlations are included in Table 5. Studies of “good” quality and low risk of bias (described as NOS score ≥ 7) with larger sample sizes (n > 1,000) are emphasized.

3.3.1 Individual factors

3.3.1.1 Personal traits/style

The findings of 3 studies with good NOS scores with larger sampler sizes (77, 81, 86) were examined in more detail. Adolescents with a high sense of security and positive coping style were more resilient to the negative effects of victimization. Adolescents with low self-esteem were more susceptible to bullying victimization and its negative health effects.

Self-esteem – Adolescents with repeated victimization had significantly lower levels of self-esteem and overall health, compared with none or one-time victimization (81). In LBC, depression was higher in children with low self-esteem compared to those with high-self-esteem (odds ratio (OR) 2.47***) (63). Active or passive victimization also had mediation effect on the relationship between increased BMI and low self-esteem (69). In smaller studies, low self-esteem predicted cyberbullying victimization (25), while friendship intimacy correlated positively with self-esteem (29).

Sense of security is a perception and reaction of one’s security state apart from anxiety and fear (Maslow’s hierarchical theory of needs) (86). Sense of security partially mediated depression risk, with more secure individuals experiencing less depression. Victimization (N = 1,174) was negatively associated with sense of security, and sense of security was negatively associated with depressive symptoms (86).

Coping style is an approach where individuals can use their cognition and strategies to manage stressful events. They are predominantly positive (problem solving, seeking support) or negative (avoiding, enduring) (77). Adolescents with negative coping styles (n = 10,006) who experienced relational victimization (β = 3.42***) and cyberbullying victimization (β = 4.82***) were more likely to have anxiety than those with a positive coping style. They were also more likely to have depression than those with a positive coping style (β = 10.32***) (77).

In other smaller studies, ‘active coping’ (71), high support-seeking (59), mindfulness (73), self-compassion (49), and ‘solution-oriented’ conflict resolution skills (65), resulted in better outcomes from victimization. Individuals with high interdependence (22) and hopelessness (49) had poorer outcomes.

Mindfulness (which refers to a trait of being aware of ongoing physical, cognitive and psychological experiences, and requires attention control, self-awareness and self-empathy or acceptance) moderated both bullying victimization on resilience (β = 0.23***) and bullying victimization on depression (β = − 0.11**), and this was seen more in children with low mindfulness (73).

Self-compassion moderated the effects of victimization on depression (47). Self-compassion is described as a ‘kind and understanding disposition exhibited towards the self in times of trouble and failures’ (32, 47). Self-compassion negatively predicted depression in bullying victimization (32, 47). In individuals with low self-compassion, cyberbullying victimization was associated with hopelessness (β = 0.70***) and depression (β = 0.36*).

‘Interdependence’ is a construct where individuals rely on emotional connection with others for their self-view. Studies by Kawabata et al. (n = 387) (22) and Yin et al. (71) found that adolescents who placed great value and emphasis on relationships (i.e., highly interdependent) were more likely to have subsequent depressive symptoms if they experienced relational victimization) (r = 0.72***) (22).

3.3.1.2 Age

In 2 large studies with good NOS scores, the effects of age were opposite (31, 43). Chan et al. (43) (n = 18,341) found age was negatively associated with bully victimization (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 0.91***). Li et al. (31) (n = 10,279) on the other hand, found bullying victimization was higher in older adolescents (n = 2,498) (Table 5). Bullying victimization increased with increasing age in three other studies (49, 51, 70), with a higher risk of depression in older adolescence (49, 51). Age was a moderator of bullying victimization and depression in older females through sleep problems (23). In only one study (n = 661) in Chinese adolescents did bullying victimization lead to higher rates of depression in younger children (25) where students in Grade 7 had greater symptoms of depression (F(1,594) = 4.13*) than in Grade 8.

3.3.1.3 Gender

In 3 studies with good NOS scores and larger sample size (28, 44, 45), male adolescents were more likely than females to be involved with traditional and cyberbullying victimization/perpetration (Table 5). In 3 other good quality studies, sexual minority status was overwhelmingly associated with victimization and depression risk (75, 80, 85).

Chinese boys (n = 1,019) scored higher at T1and T2 than girls (n = 668) on bully victimization (26) (Table 5). Male gender (n = 901) was also associated with cyberbullying victimization (OR 1.62) and cyberbullying perpetration (OR 1.59) more than female gender in Taiwan (42). Taiwanese males were also more likely to be cyberbully perpetrators (OR 1.57) and cyberbully-victims (OR 3.17) than females (43).

Sexual minority status was strongly associated with bullying victimization (74, 79, 84) and depression risk. In Liu et al. (85), homosexuality (n = 74) (AOR 6.40*), bisexuality (n = 139) (AOR 3.15*) and uncertainty of sexual orientation (n = 588) (AOR 2.34*) were significantly associated with a combination of traditional and cyberbullying victimization when compared with heterosexual status. Sexual minority students, especially bisexual students, had a higher risk of depressive (AOR 2.35*) and anxious mood (AOR 3.05*) compared to heterosexual students. In a large Chinese study (75) (n = 16,380), sexual minority youths (n = 1,360) were more likely to experience maltreatment (AOR range: 1.25-2.46**) and bully victimization (AOR range: 1.38 – 1.77**) and a series of health problems (AOR range: 1.85 – 3.69***) than youths with opposite-sex attraction. In Peng et al. (80), LGBTQ adolescents (n = 668) had higher odds of experiencing sibling victimization only (OR 1.41*), or peer victimization only (OR 1.54**) or both sibling and peer victimization (OR 2.23***) compared to heterosexual adolescents (n = 2,394).

3.3.1.4 Other factors

Cognitive Ability and Academic Achievement – Victimization scores were higher for those with low cognitive ability scores (n = 2,631) (M = 11.6 vs. 10.4***) when compared to adolescents with highest ability scores (n = 2,210) (31). In the same study (n = 10,279), victimization was also associated with poorer academic achievement at 2 and 5 year follow up (β2yr = -0.04**, β5yr = -0.03*).

There were 2 good quality studies on BMI (26, 69). Overweight adolescents (n = 5,252) had increased risk of victimization and poorer mental health outcomes (69). Increased BMI was positively associated with severity of victimization (active and passive bullying, perpetration of passive bullying) and these severities were positively associated with severities of social phobia, depression, suicidality and low self-esteem (Table 5). The association between BMI and depressive symptoms was also significantly mediated by peer victimization and sleep problems in Chang (n = 1,893) (26). Higher BMI predicted more peer victimization, leading to more sleep problems, and to higher levels of depressive symptoms (Total effect β = -0.039, SE 0.020, 95% CI: -0.079 to 0.001).

3.3.2 Family factors

Parent – child attachment was examined in 3 good quality papers with larger sample size (44, 72, 83). In Chang et al. (44) (n = 1,867), adolescents with cyberbullying victimization had lower parental attachment (OR 0.79) compared to those without cyberbullying victimization. Parent – child attachment significantly moderated effects of cyberbullying victimization on depression in a study by Zhu et al. (n = 3,232) (83). In adolescents with greater levels of parent – child attachment, the lifetime and preceding year cyberbullying victimization had less effects on adolescents’ depressive symptoms (βlifetime = -0.33***; βpast year = -0.57***) and PTSD (βlifetime = -0.40**; βpast year = -0.54*) compared with those with lower attachment scores (83). Parent – child attachment also moderated the effects of victimization on depression in all three groups (bully, bully-victim, victim) in a Korean study of 1793 adolescents (70). In adolescents experiencing victimization, significantly lower levels of depression were reported by those who held a higher attachment to their parents than those who had a lower attachment (β = - 0.33***) (83).

Family dysfunction was explored in 3 good quality papers with larger sample size (31, 47, 52) and was associated with increased bullying victimization, perpetration and depression. In Chen et al. (n = 18,341) (47), parental divorce/separation/parent widow status (AOR 1.37 – 1.68*) was associated with bully perpetration. All types of family victimization (conflicts within family) were associated with greater risk of bully victimization (AOR 1.99 – 5.36***). All types of family victimization (except neglect) were associated with cyberbullying victimization (AOR 2.24 – 5.36***) (47). In a Korean study of 10,453 adolescents (52), high levels of parental abuse (β = 0.05***); high levels of parental neglect (B=0.025*); and high levels of family dysfunction (β = 0.053**) were associated with direct cyberbullying victimization (adjusted R2 = 0.173). In Li et al. (n = 10,279) (31) traditional bullying victimization scores were higher for adolescents who were not close to parents (n = 5,335) (M: 11.3 (4.4) vs. (10.6 (4.2) ***) in adolescents who were closer to parents; and for adolescents not living with parents (n = 3,084) (M: 11.3(4.4) vs. 10.6(4.2) ***) compared to those living with parents. Cyberbullying victimization was also associated with fewer parental restrictions (OR 0.89) than in children with more parental oversight in the Taiwan study (n = 1,867) (44).

Sibling association with bullying victimization was examined in four large studies (31, 43, 78, 80). Liu et al. (n = 8,918) (78) specifically explored the sub-types of sibling bullying among Chinese children and adolescents. Sibling bullying perpetration (n = 1230) (verbal, physical or relational) had a higher risk of major depression (AOR 1.44***) and anxiety (AOR 1.63 ***) than those not involved with bullying. Sibling bullying victimization (n = 1,235) (verbal, physical or relational) had a higher risk of major depression (AOR 1.49***) and anxiety (AOR 1.68***) than those not involved with sibling victimization. Peng et al. (80) found that sexual minority adolescents (i.e., LGBTQ) experienced more bullying from their siblings. Adolescents with siblings were more like to be involved in bullying victimization and perpetration. In Chen et al. (n = 18,341) (43), having siblings (AOR 1.36* – 1.41***) was associated with bullying perpetration and bullying victimization (AOR 2.00***) compared to adolescents with no siblings. In Li et al. (n = 10,279) (31), traditional bullying victimization scores were also higher for those with siblings (n = 6,774) (M: 11 vs. 10.5***), compared to those without.

3.3.3 Community factors

3.3.3.1 Peer relationships

Friendship intimacy (29, 37, 41, 62, 71) strongly contributed to reduced risk of depression, improved self-esteem and well-being, with less bullying victimization. Two good quality papers explored this theme (37, 41). In Yang et al. (37), (n = 2,339), adolescents who had resilient profiles [n = 188 (8%)] had higher levels of bullying victimization but low levels of depression and high levels of subjective well-being. Higher level of friend support contributed to a ‘resilient’ profile. Adolescents in the ‘Resilient’ profile group benefitted from more teacher and peer support. Support from teachers and peers correlated positively with subjective well-being r = 0.28***; r = 0.31***); correlated negatively with bullying victimization (r = -0.20***; r = -.0.51***); and correlated negatively with depressive symptoms (r = -0.23***; r = -0.30***) (35). Higher friendship quality also dramatically increased odds of moving from a victim or bully-victim to non-involved adolescent [Victim to Uninvolved (OR 7.31***)]; [Bully-victim to Uninvolved (OR 17.07***) (41). In a smaller study with high NOS score, greater friendship intimacy (n = 450 in Yang et al.) was measured by adolescents’ level of intimacy with up to four best friends. T1 Bullying victimization and T1 Friendship intimacy was a moderator and correlated positively with T2 self-esteem (β = 0.090*).

Conversely, adolescents with lower levels of peer support (β = -1.05**, OR 0.35) were more likely to be classified as ‘Adverse’ profiles, rather than the ‘Resilient’ profile in Yang et al. (37). Adverse profiles [n = 89 (3.8%)] had the highest level of bullying victimization, highest levels of depression, and lowest levels of subjective well-being.

3.3.3.2 School Environment

Adolescents who have been bullied have less depression if they have more teacher support (35, 60), better peer support (50, 71) and higher levels of school connectedness (the belief that others in school care about their learning, and them as individuals) (51) (Table 5).

In contrast, adolescents with lower levels of teacher support (β = -0.87**, OR 0.42) were more likely to be classified as ‘Adverse’ profiles, rather than the ‘Resilient’ profile in Yang et al. (37). Bullying by teachers (46, 51) (including quarrelling with teacher, emotional or physical punishment by teacher) correlated with depression. Surprisingly, adolescents within low victimization environments had more reactive aggression, and victims of physical bullying had more depression compared to those in higher victimization environments. In Zhao et al. (n = 691) (42), physically and relationally (but not verbally) victimized adolescents in healthy cliques with lower victimization norms reported committing more reactive (not proactive) forms of aggression ((Externalizing)BphysicalV = -0.10*; BrelationalV = 0.10*) and having more depressive symptoms 2 years later ((Internalizing) BphysicalV =0.20**) (Table 5). This may be explained by the ‘healthy context paradox’ which describes children in cliques with lower victimization levels reacting more aggressively as there is greater disparity with the majority of peers (i.e., social misfit), further aggravating peer isolation. LBC also experienced more severe bullying in schools (OR 2.37***) (63).

3.4 Social determinants of health

Higher parental education was protective (29) through higher paternal occupational socio-economic status, but the risk of cyberbullying victimization also increased (70), possibly due to increased online access. Lower socio-economic status (25, 31, 61), lower maternal education (31, 47) and paternal unemployment (31, 47) were associated with higher rates of bullying victimization (47, 61) and depression (25).

3.5 Type of bullying with higher risk of depression

Higher depression levels or poorer well-being resulted from bullying perpetration of passive and active bullying (68), higher levels of bullying victimization (37), bullying by being threatened or intimidated (33), poly-victims (those experiencing more than one type of bullying (43, 81), and those in the bully-victim group (56). In a Japanese study (56) of 486 adolescents, boys who are bully-victims (n = 35) had significantly higher mean scores when compared with the neither group (n = 146) in terms of social problems (M=5.06***), attention problems (M=7.29 ***), aggressive behaviour, (M=9.80***), and the externalizing scale (M=12.23***) (Table 5). For adolescent girls, the mean scores for the bully-victim group were significantly higher than those for the Neither group for all the dimensions and subscales measured above.

3.6 Vulnerable Groups

3.6.1 Left behind children

LBC accounting for around 69 million children in China are children left in the care of grandparents or one parent in rural areas when their parent(s) move to cities in China for work (61, 63, 64). LBC have a higher risk of bullying victimization and being depressed as a result (61). The presence of high maternal psychological control increased bully victimization in LBC whereas a with the presence of both maternal high psychological and behavioural control on children, the negative effect of bully victimization on self-injury was buffered. When left behind women had low psychological control, then higher maternal behaviour control worsened the negative effect of peer victimization on self-injury (64). In LBC, depression from bullying victimization also increased with being an only child (OR 1.55***), low self-esteem (OR 2.47***), being in care of another relative as opposed to mother only (OR 2.84***) (63).

3.6.2 Ethnocultural bullying

Ethnocultural (i.e., racial or religious) bullying was significantly associated with depression. Racial bullying was associated with depression in females (AOR 2.19*) and religious bullying was associated with depression in males (AOR 8.85**) (74).

3.6.3 Adolescents with developmental conditions and existing mental health issues

Two studies (54, 70) showed that children with developmental disorders such as ADHD had depressive symptoms associated with bully victimization (β = 0.190**) or perpetration (β = 0.228***).

Adolescents with prior mental health conditions had higher risk of both being victims and perpetrators (36). Those with existing depression were more likely to be victims or bully/victims (27, 41), or bully perpetrators (36, 82) and those with social anxiety (76) were more likely to be victims. Adolescents with mild anxiety were more likely bully perpetrators than those with more severe anxiety (82).

Problematic Internet Use – Korean boys had a higher prevalence of PIU compared to girls (16.1% vs. 8.1%) (55). All groups including victim only (OR 2.36***), bully only (OR 1.66*) and bully-victim group (OR 2.38***) had a higher likelihood of PIU than the group who were neither victims nor bullies. Cyberbullying victims were also more likely to be depressed (OR 4.2 ***) in this study (55). In a Taiwan study of 1808 high school students, internet addiction was also found to be associated with depression (OR 1.92) (44).

4 Discussion

4.1 Prevalence rates of bullying victimization

In East Asian countries, the prevalence rates of bullying and victimization in adolescence varied greatly and ranged from 6.1 – 61.3% in traditional bullying victimization, and 3.35 – 74.6% in cyberbullying victimization. This variation in prevalence rates of bullying victimization is also observed globally. Data from the Global School-based Student Health Survey GSHS (2003 – 2015) of school children aged 12 – 17 years showed that the Eastern Mediterranean Regions (including the middle East) had the highest prevalence (45.1%) (87) compared with rates of 24% from China. Prevalence rates from Europe and North America were not covered in this study but in other studies were reported to be up to 36% of European adolescents (88) and 20.2% of American youth (89).

The possible downward trend of rates of bullying victimization in studies conducted after 2012 may reflect the global outcry of bullying in schools, raising awareness at the community level and successful national responses with the implementation of policies to prevent bullying and deal with perpetrators in schools (90).

There was also variation in prevalence rates within the three subgroups of bullying victimization (bully, victim, bully-victim) described. The prevalence rates of bully-victims in adolescents was highest in Japan (15.9%) (56) and lowest in Fujian, China (3%) (53). The literature is clear that bully-victims have the poorest functioning with poorer emotional adjustment, peer relationships and health, and longer-term outcomes including depression, suicidal ideation, substance abuse and delinquency (91, 92) compared to bullies and victims.

Bully-victims had the most dysfunction (93) and consequent poor school engagement and academic functioning. Bully-victims experienced intense emotional distress from feelings of helplessness and anxiety when victimised, to feelings of anger and frustration when bullying others. The cycle of being victimised and bullying others made it difficult for them to form positive relationships with others. Hence, they were the most socially isolated, perceived as social outcasts by peers and tended to provoke negative reactions (93). They were also more likely to experience violence and extreme discipline at home and have a chaotic family life (94). With a paucity of peer and home supports (95), they were at much higher risk of poorer mental and physical health outcomes.

4.2 Discussion of bullying and depression

Similar to Western cultures (96–98) there is a strong positive correlation between bullying and depression seen in East Asian adolescents. In a recent meta-analysis, the risk of depression in children and adolescents was 2.77 times higher if they were bullied (97). The aims of this scoping review are to determine if there were unique aspects of East Asian ‘collectivistic’ culture which would predispose adolescents to bullying and depression when bullying occurred, and the presence of protective factors.

The main findings are that risk and protective factors for bullying and victimization in East Asian cultures are very similar to those reported in Western cultures. The evidence being that strong relationships within families, peers and the school community coupled with adolescents’ positive coping style and view of the world are protective against the negative effects of bullying. Conversely, poor parent-child attachment amidst family dysfunction, poor engagement with peers and the school community together with a negative coping style predispose East Asian adolescents to depressive symptoms as a result of bullying victimization.

Healthy and supportive relationships within family systems, peer interactions and teacher engagement are key to increasing ‘resilience’ in East Asian adolescents who experience victimization, and this is no different to that seen in Western cultures. Studies with high NOS scores of 7 and above with larger sample sizes (above 1000) support this conclusion (Table 5).

4.2.1 Family factors

Within family systems, poorer parent-child attachment (44, 73) or family dysfunction with separation, conflicts, abuse and neglect (31, 47, 52) were found to be significantly associated with bully victimization and risk of depression.

It is not surprising that adolescents with poorer attachment to parents are at higher risk of bully victimization and subsequent depression. Secure attachment to a caregiver from infancy provides the foundation for children to learn to trust and grow in social emotional competencies (99). These include the ability to manage difficult emotions such as fear, anger or anxiety. Insecurely attached children may become more avoidant or anxious. In the absence of secure attachment to a parent, children are likely to have difficulties regulating their emotions and as they mature, managing negative experiences like victimization (100). Adolescents with poor attachment are more likely to have low self-esteem and negative coping strategies to stress (101). They may have more emotional dysregulation with increased aggression or passivity. This further impairs their social functioning increasing social isolation, spiralling into more withdrawal, victimization and depression (102).

Similarly, adolescents from dysfunctional homes (31, 47, 52) experienced more victimization and a higher risk of depression. Parent separation/divorce is associated with bully perpetration (47). The emotional turmoil from family dysfunction, may lead to them trying to regain control by acting out these feelings. They are also susceptible to risk-taking behaviours (especially in single-father families) and vulnerable to victimization (103), probably due to lack of home supervision and susceptibility to peer pressure.

All types of family victimization were associated with greater risk of bully victimization as adolescents (47). Children who experience victimization at home are more likely to be exposed to negative parenting behaviours which may be harsh, maladaptive or neglectful (104) and model these behaviours on peers.

The finding of a sibling as bullies is concerning. Sibling bullying is common (105, 106), and mostly harmless (107). However, sibling bullying can increase likelihood of depression and anxiety. Liu et al. (78) found significantly higher risks of depression and anxiety in sibling perpetration and victimization. LGBTQ adolescents were also more likely to be bullied by siblings than heterosexual adolescents (80). Sibling victimization may be a reflection of family dysfunction and conflict while LGBTQ sibling victimization may instead be due to social stigma and internalised homophobia (108).

Two other Chinese studies showed that adolescents with siblings were more likely to be victims (31, 47) or perpetrators (43) but not necessarily of their siblings. It is possible that with larger families in rural China (31), there may be fewer resources (i.e., lower socio-economic status) (24, 31, 61), to reduce stress in the home compared to smaller families.

4.2.2 Community factors

In the area of peer relationships, friendship quality and intimacy (29, 37, 41, 62, 71) strongly contributed to reduced risk of depression, improved self-esteem and well-being with less bully victimization. Higher levels of friend support, intimacy with friends and quality of friendships were protective against victimization and subsequent depressive symptoms. High quality friendship was also shown to increase the likelihood of moving from a victim or bully-victim to an uninvolved adolescent (41). This is a very hopeful finding given that bully-victims have the worst outcomes of all the bully subgroups.

Friendship support, especially high-quality friendships, in both East Asian (29, 37) and Western cultures (109), is one of the most effective protective factors against bully victimization, perpetration and development of depression in adolescents. One of the most important tasks of adolescence is to form and sustain friendships. Friendships provide emotional support and validation, buffer against isolation and loneliness, problem-solving strategies for both victims and perpetrators. Friends can also model more positive coping strategies and defend victims against bullies (110).

In the school community, adolescents with more teacher support (37, 62), better peer support and higher levels of school connectedness (the belief that others in school care about their learning, and them as individuals) (51) experienced less depression when victimized. Nurturing teachers provide students with safety from bullying, social and emotional support, and a sense of belonging (111). Adolescents who are more connected to school participate more positively with their teachers and peers and have improved academic engagement. Nurturing teachers also provide positive role models and can teach victimized adolescent more positive coping strategies in the presence of bullying victimization. This is critical at a time when the adolescent is developing their identity, sense of self and purpose. More importantly, as persons in authority teachers can stop bullying victimization when it occurs (112).

4.2.3 Individual factors

Adolescents with a high sense of security, high self-esteem (63) and positive coping style (30, 77, 86) were found to be more resilient to the negative effects of bullying victimization. This was seen in both Western and East Asian cultures (30, 77, 86, 113).

A positive coping style (77) was found to reduce the risk of anxiety and depression (71) from victimization. Coping styles included problem focused/solution orientated (71), social support seeking (51), positive self-talk, emotion-focused coping (i.e., mindfulness (73) and relaxation approaches), cognitive reappraisal (71) and self-compassion (34, 49). Coping styles are potential areas for intervention where victimized adolescents can learn more positive ways to manage being bullied. For instance, adolescents who are victimized can learn how to seek social support from family, peers or teachers.

Self-esteem was an important mediator in the link between bullying victimization and depression, with low self-esteem being a risk factor for depression while higher self-esteem contributed towards resilience (114).

Sense of security was important in adolescents’ sense of self (115). When adolescents felt emotionally and physically secure they were less likely to be targeted by bullies. Secure adolescents were also more confident and assertive and sought out positive relationships. They were also more likely to seek help when victimized.

4.2.4 Other findings

In both cultures, bully-victims and poly-victims fared the worst and had the highest risk of depression as a result of bullying victimization. Patterns of bullying (with gender differences) were also noted to be similar between East Asian and Western cultures. In East Asian cultures, boys were more likely to be physically bullied while girls were more likely to experience relational or verbal victimization (72). These patterns were similarly noted in Western countries (91, 116, 117). Problematic internet use (PIU) was also found to be associated with bully victimization (55) and depression (44) in both East Asian (118, 119) and Western cultures (120).

4.2.5 The uniqueness in East Asian Confucian-informed cultures

‘Being different’ – Appears to be a considerable risk factor in collectivistic cultures which promote group harmony and blending in (121). Adolescents who are in the sexual minority, LBC, have racial or religious differences, or body weight differences are vulnerable to bullying as they stand out. Of these, sexual minority status has significant implications for East Asian culture.

Sexual minority status (i.e., LGBTQ, bisexual status) in adolescents was found to be strongly associated with bullying victimization (75, 80, 85) and depression risk. This may be because of the strong emphasis of traditional gender roles in East Asian Confucian informed cultures. Traditional views of gender mean that any deviation from this is seen as aberrant and increases the risk of victimization. Family expectations and the concept of filial piety is the expectation that children will fulfil traditional roles of marriage, and have children to carry on the family line (122). Sexual minority status also may bring shame to families and disrupt social harmony where the needs of the group have to be placed above the needs of the individual (123). As such, sexual minority adolescents are susceptible to victimization and may have difficulties accessing support when social norms do not support LGBTQ individuals.

Left behind children (LBC) – LBC are at risk for bullying victimization. Although parent migration for work is not unique to China, these children are particularly vulnerable and get ‘left behind’ in developmental, learning and mental health outcomes (124). This may also account for children living in rural areas in China experiencing higher rates of bully victimization.

Teachers as bullies – In collectivistic cultures where group harmony is valued over the needs of an individual, adolescents are particularly susceptible to bullying from figures in authority. The finding of ‘teachers’ as bullies was indeed startling (46, 51, 52). The Confucian ethos which pervades all aspects of life in East Asian cultures may also mean that school systems may be more authoritarian and punitive rather than consultative (125). Teacher violence was prevalent, with up to 50% and 62% of children reporting corporal punishment by teachers in China and South Korea, respectively (125). Teachers’ bullying students is a much rarer occurrence in Western cultures (1.2%) (126) where the reverse occurs, with studies showing teachers experiencing bullying by students (80% of Australian teachers were bullied by students in a Latrobe study) (127). Apart from teachers, older students in schools may perpetrate acts of bullying. In East Asian countries, school environments and activities may be structured in accordance with beliefs and values to reinforce the peer group and ‘authority figures’ as the administrator of approval or rejections of behaviour (127). In a qualitative study of 41 adolescents aged 12 – 16 years, key themes such as a lack of education about bullying, poor classroom and failure of teachers to recognise and address bullying were identified (128).

Differences in coping styles adopted - While positive coping styles described earlier are seen in both Eastern and Western cultures, there are also differences in the preferential use of coping style in bullying victimization (129). In Western cultures where individual rights and personal autonomy are emphasized, coping styles tend to be more problem-focused, where adolescents may confront the bully or take active steps to stop the bullying. They are also more likely to talk about their emotions and experiences through counselling. In East Asian culture where group harmony and social conformity are prioritized, adolescents may avoid direct confrontation to preserve the peace (130). Support-seeking within the family or peer group may be preferred. There may also be a tendency to suppress emotions and manage through emotional coping strategies (131).

Problematic internet use (PIU) – While PIU has been found to be associated with bully victimization in both East Asian and Western cultures, there are significant differences in the rates of PIU being much higher in East Asian countries and up to three times that in Western countries (132) eg 14% in China Vs 4% in the US (133). The higher rates of PIU may relate to adolescents gaining relief from academic pressure (134), a notable stressor in East Asian countries (135) or coping with anxiety (118, 119). Greater PIU in turn is associated with higher likelihood of bully victimization.

4.3 Study limitations

While most of the East Asian countries hold to collectivistic practices, a comparison of the degree to which it still informs policy and practice in each of the countries was not done. Within the Chinese diaspora, it was difficult to make comparisons due to the diversity across rural and urban areas and large variations in data found. The quality of papers varied significantly (Table 2) though the higher quality NOS papers were emphasized in synthesis. The time period for bullying victimization was inconsistent, with some studies reporting 30 days to lifetime versus the previous 12 months. It is possible that some evidence was omitted since non-English papers, published in Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, and Korean native languages were excluded limiting the comprehensiveness of the findings. In addition, the protocol for this scoping review has not been pre-registered. The intention was to pre-register the scoping review protocol on an open platform such as PROSPERO; however, PROSPERO does not accept scoping reviews.

4.4 Future research

The high prevalence of bullying among adolescent children suggests that more needs to be done to recognize and address the issue. The scoping review showed that a significant proportion of bullying occurred in schools through peer or teacher victimization. The whole school intervention approach (anti-bullying framework) (136–138) at four different levels of the individual, classroom, school and community has been shown to be very effective in reducing bullying victimization and increasing student satisfaction in Sweden. This approach could be the next steps of a further research initiative. The first step of applying the intervention would be to understand what is now occurring at these four levels in East Asian schools. A survey could be conducted to understand how adolescent students at an ‘individual level’ are getting help when victimization occurs, and their knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about asking for support.

4.5 Conclusion

Bullying prevalence rates varied across East Asia, from 6.1 – 61.3% in traditional bullying victimization and 3.3 – 74.6% in cyberbullying victimization, with higher prevalence rates seen in at-risk populations. Bullying correlated strongly with depression. Findings of this review suggest that risk and protective factors for bullying and victimization in East Asian cultures are very similar to those reported in Western cultures. The evidence suggests that strong relationships within families, peers and the school community coupled with adolescents’ positive coping style and high self-esteem are protective against the negative effects of bullying. Similar to Western cultures, adolescents who are bully-victims and poly-victims are most vulnerable to depression. Unique findings specific to East Asian culture are that adolescents who are perceived as ‘being different’ i.e., sexual minority, LBC are more likely to be bully victims and to experience depression. In East Asian cultures, teachers and parents who are figures of authority, may paradoxically be perpetrators of bullying and harsh physical punishment. Understanding bullying patterns, including purpose (for example, when the physical punishment is not for personal reasons), in East Asian cultures and systems of support in schools may offer further clues to providing support to bullying victims.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ER: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. WG: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. NT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. SN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. LY: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. DY: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. VL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Support was provided by National University Health System (Department of Paediatrics, Khoo Teck Puat – National University Children’s Medical Institute; Department of Family Medicine) for paying the journal publication fee.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Sheena Nishanti Ramasamy (Department of Paediatrics, National University of Singapore) for providing editorial support and for Dr Nicholas Ng (Department of Paediatrics, National University Hospital) for invaluable support in manuscript revisions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1497866/full#supplementary-material

References

1. World Health Organization. . Adolescent mental health (2021). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (Accessed April 20, 2023).

2. World Health Organization. Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA)! - Guidance to Support Country Implementation (2017). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available online at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255415/9789241512343-eng.pdf (Accessed April 20, 2023).

3. Roh B-R, Jung EH, Hong HJ. A comparative study of suicide rates among 10–19-year-olds in 29 OECD countries. Psychiatry Invest. (2018) 15:376–83. doi: 10.30773/pi.2017.08.02

4. Prevention of depression and suicide - Consensus Paper (2008). Luxembourg: European Communities. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/health/archive/ph_determinants/life_style/mental/docs/consensus_depression_en.pdf (Accessed June 13, 2018).

5. Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet. (2009) 373:1372–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X

6. World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Mental health status of adolescents in South-East Asia: evidence for action (2017). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254982 (Accessed April 20, 2023).

7. Saluja G, Iachan R, Scheidt PC, Overpeck MD, Sun W, Giedd JN. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2004) 158:760–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.760

8. Kanetsuna T. Comparisons between English bullying and Japanese ijime. In: Smith PK, Kwak K, Toda Y, editors. School Bullying in Different Cultures: Eastern and Western Perspectives. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press (2016). p. 153–69.

9. Shamrova D, Lee JM, Choi S. School bullying victimization and child subjective well-being in east Asian countries and territories: Role of children’s participation in decision-making in schools and community. Children Soc. (2024) 00:1–18. doi: 10.1111/chso.12888

10. Haner M, Lee H. Placing school victimization in a global context. Victims Offenders. (2017) 12:845–67. doi: 10.1080/15564886.2017.1361675

11. Chen X. Growing up in a collectivist culture: Socialization and socioemotional development in Chinese children. In Comunian AL & Gielen UP. In: International perspectives on human development. Germany: Pabst Science Publishers (2000). p. 331–53.

12. Zhang YB, Lin M-C, Nonaka A, Beom K. Harmony, hierarchy and conservatism: A crossCultural comparison of confucian values in China, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. Communication Res Rep. (2005) 22:107–15. doi: 10.1080/00036810500130539

13. Fox CL, Jones SE, Stiff CE, Sayers J. Does the gender of the bully/victim dyad and the type of bullying influence children’s responses to a bullying incident? Aggress Behav. (2014) 40:359–68. doi: 10.1002/ab.21529

14. Smith PK, Robinson S. How does individualism-collectivism relate to bullying victimisation? Int J bullying Prev. (2019) 1:3–13. doi: 10.1007/s42380-018-0005-y

15. Smith PK ed. School bullying in different cultures. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press (2016).

16. Bergmuller S. The relationship between cultural individualism-collectivism and student aggression across 62 countries. Aggressive Behav. (2013) 39:182–200. doi: 10.1002/ab.21472

17. Stringham Z. The Three Goals of Adolescence (2017). USA: WeHaveKids. Available online at: https://wehavekids.com/parenting/Parents-One-thing-you-can-do-for-your-teenage-children (Accessed April 20, 2023).

18. World Population Review. East Asian Countries. California, USA: World Population Review (2023). Available at: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/east-asian-countries (Accessed January 20, 2024).

19. World Health Organization – Regional Office for South-East Asia. Adolescent health in the South-East Asia Region (2021). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available online at: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health:~:text=WHO%20defines%20%27Adolescents%27%20as%20individuals,age%20range%2010%2D24%20years (Accessed April 20, 2023).

20. Vivolo-Kantor AM, Martell BN, Holland KM, Westby R. A systematic review and content analysis of bullying and cyber-bullying measurement strategies. Aggress Violent Behav. (2014) 19:423–34. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.06.008

21. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses (2014). Ontario, Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Available online at: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (Accessed April 20, 2023).

22. Kawabata Y, Tseng WL, Crick NR. Mechanisms and processes of relational and physical victimization, depressive symptoms, and children’s relational-interdependent self-construals: implications for peer relationships and psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. (2014) 26:619–34. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000273

23. Chang LY, Wu CC, Lin LN, Chang HY, Yen LL. Age and sex differences in the effects of peer victimization on depressive symptoms: Exploring sleep problems as a mediator. J Affect Disord. (2019) 245:553–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.027

24. Hong HC, Min A. Peer victimization, supportive parenting, and depression among adolescents in South Korea: A longitudinal study. J Pediatr Nurs. (2018) 43:e100–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2018.08.002

25. Chu XW, Fan CY, Lian SL, Zhou ZK. Does bullying victimization really influence adolescents’ psychosocial problems? A three-wave longitudinal study in China. J Affect Disord. (2019) 246:603–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.103

26. Chang LY, Chang HY, Wu WC, Lin LN, Wu CC, Yen LL. Body mass index and depressive symptoms in adolescents in Taiwan: testing mediation effects of peer victimization and sleep problems. Int J Obes (Lond). (2017) 41:1510–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.111

27. Chen L, Chen X. Affiliation with depressive peer groups and social and school adjustment in Chinese adolescents. Dev Psychopathol. (2020) 32:1087–95. doi: 10.1017/S0954579419001184

28. He Y, Chen SS, Xie GD, Chen LR, Zhang TT, Yuan MY, et al. Bidirectional associations among school bullying, depressive symptoms and sleep problems in adolescents: A cross-lagged longitudinal approach. J Affect Disord. (2022) 298:590–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.038

29. Yang P, Zhao S, Li D, Ma Y, Liu J, Chen X, et al. Bullying victimization and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model of self-esteem and friendship intimacy. J Affect Disord. (2022) 319:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.038

30. Xiong Y, Wang Y, Wang Q, Zhang H, Yang L, Ren P. Bullying victimization and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents: the roles of belief in a just world and classroom-level victimization. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2023) 32:2151–62. doi: 10.1007/s00787-022-02059-7

31. Li L, Jing R, Jin G, Song Y. Longitudinal associations between traditional and cyberbullying victimization and depressive symptoms among young Chinese: a mediation analysis. Child Abuse Negl. (2023) 140:106141. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106141

32. Yuan G, Liu Z. Longitudinal cross-lagged analyses between cyberbullying perpetration, mindfulness and depression among Chinese high school students. J Health Psychol. (2021) 26:1872–81. doi: 10.1177/1359105319890395

33. Ren P, Liu B, Xiong X, Chen J, Luo F. The longitudinal relationship between bullying victimization and depressive symptoms for middle school students: A cross-lagged panel network analysis. J Affect Disord. (2023) 341:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.08.048

34. Yan R, Ding W, Wang D, Lin X, Lin X, Li W, et al. Longitudinal relationship between child maltreatment, bullying victimization, depression, and nonsuicidal self-injury among left-behind children in China: 2-year follow-up. J Clin Psychol. (2023) 79:2899–917. doi: 10.1002/jclp.v79.12

35. Gao L, Liu J, Yang J, Wang X. Longitudinal relationships among cybervictimization, peer pressure, and adolescents’ depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. (2021) 286:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.049

36. Perret LC, Ki M, Commisso M, Chon D, Scardera S, Kim W, et al. Perceived friend support buffers against symptoms of depression in peer victimized adolescents: Evidence from a population-based cohort in South Korea. J Affect Disord. (2021) 291:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.078

37. Yang L, Xiong Y, Gao T, Li S, Ren P. A person-centered approach to resilience against bullying victimization in adolescence: Predictions from teacher support and peer support. J Affect Disord. (2023) 341:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.08.089

38. Liang Y, Chen J, Xiong Y, Wang Q, Ren P. Profiles and transitions of non-suicidal self-injury and depressive symptoms among adolescent boys and girls: predictive role of bullying victimization. J Youth adolescence. (2023) 52:1705–20. doi: 10.1007/s10964-023-01779-6

39. Shen Z, Xiao J, Su S, Tam CC, Lin D. Reciprocal associations between peer victimization and depressive symptoms among chinese children and adolescents: Between-and within-person effects. Appl Psychology: Health Well-Being. (2023) 15:938–56. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12418

40. Long Y, Zhou H, Li Y. Relational victimization and internalizing problems: Moderation of popularity and mediation of popularity status insecurity. J Youth adolescence. (2020) 49:724–34. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-01177-x

41. Yu L, Li X, Hu Q, Guo Z, Hong D, Huang Y, et al. School bullying and its risk and protective factors in Chinese early adolescents: A latent transition analysis. Aggressive Behav. (2023) 49:345–58. doi: 10.1002/ab.22080

42. Zhao Q, Li C. Victimized adolescents’ aggression in cliques with different victimization norms: The healthy context paradox or the peer contagion hypothesis? J school Psychol. (2022) 92:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2022.03.001

43. Chan KL. Victimization and poly-victimization among school-aged Chinese adolescents: prevalence and associations with health. Prev Med. (2013) 56:207–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.12.018

44. Chang FC, Chiu CH, Miao NF, Chen PH, Lee CM, Chiang JT, et al. The relationship between parental mediation and Internet addiction among adolescents, and the association with cyberbullying and depression. Compr Psychiatry. (2015) 57:21–8. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.11.013

45. Chang FC, Lee CM, Chiu CH, Hsi WY, Huang TF, Pan YC. Relationships among cyberbullying, school bullying, and mental health in Taiwanese adolescents. J Sch Health. (2013) 83:454–62. doi: 10.1111/josh.12050

46. Chen JK, Wu C, Chang CW, Wei HS. Indirect effect of parental depression on school victimization through adolescent depression. J Affect Disord. (2020) 263:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.126

47. Chen Q, Lo CKM, Zhu Y, Cheung A, Chan KL, Ip P. Family poly-victimization and cyberbullying among adolescents in a Chinese school sample. Child Abuse Negl. (2018) 77:180–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.015

48. Chen Q, Chan KL, Cheung ASY. Doxing victimization and emotional problems among secondary school students in Hong Kong. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:2665. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122665

49. Chu X-W, Fan C-Y, Liu Q-Q, Zhou Z-K. Cyberbullying victimization and symptoms of depression and anxiety among Chinese adolescents: Examining hopelessness as a mediator and self-compassion as a moderator. Comput Hum Behav. (2018) 86:377–86. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.039

50. Guo J, Li M, Wang X, Ma S, Ma J. Being bullied and depressive symptoms in Chinese high school students: The role of social support. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 284:112676. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112676

51. He G-H, Strodl E, Chen W-Q, Liu F, Hayixibayi A, Hou X-Y. Interpersonal conflict, school connectedness and depressive symptoms in chinese adolescents: moderation effect of gender and grade level. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2182. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16122182

52. Hong JS, Kim DH, Thornberg R, Kang JH, Morgan JT. Correlates of direct and indirect forms of cyberbullying victimization involving South Korean adolescents: An ecological perspective. Comput Hum Behav. (2018) 87:327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.010

53. Hong L, Guo L, Wu H, Li P, Xu Y, Gao X, et al. Bullying, depression, and suicidal ideation among adolescents in the fujian province of China: A cross-sectional study. Med (Baltimore). (2016) 95:e2530. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002530

54. Hu HF, Chou WJ, Yen CF. Anxiety and depression among adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: The roles of behavioral temperamental traits, comorbid autism spectrum disorder, and bullying involvement. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. (2016) 32:103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2016.01.002

55. Jung YE, Leventhal B, Kim YS, Park TW, Lee SH, Lee M, et al. Cyberbullying, problematic internet use, and psychopathologic symptoms among Korean youth. Yonsei Med J. (2014) 55:826–30. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.3.826

56. Kozasa S, Oiji A, Kiyota A, Sawa T, Kim SY. Relationship between the experience of being a bully/victim and mental health in preadolescence and adolescence: a cross-sectional study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2017) 16:37. doi: 10.1186/s12991-017-0160-4

57. Lee Y, Kim S. The role of anger and depressive mood in transformation process from victimization to perpetration. Child Abuse Negl. (2017) 63:131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.014

58. Li Y, Yuan Z, Clements-Nolle K, Yang W. Sexual orientation and depressive symptoms among high school students in jiangxi province. Asia Pac J Public Health. (2018) 30:635–43. doi: 10.1177/1010539518800335

59. Ma TL, Chow CM, Chen WT. The moderation of culturally normative coping strategies on Taiwanese adolescent peer victimization and psychological distress. J Sch Psychol. (2018) 70:89–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2018.08.002

60. Min A, Park S-C, Jang EY, Park YC, Choi J. Variables linking school bullying and suicidal ideation in middle school students in South Korea. J Psychiatry. (2015) 18:1000268. doi: 10.4172/psychiatry.1000268

61. Seo HJ, Jung YE, Kim MD, Bahk WM. Factors associated with bullying victimization among Korean adolescents. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2017) 13:2429–35. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S140535

62. Shao A, Liang L, Yuan C, Bian Y. A latent class analysis of bullies, victims and aggressive victims in Chinese adolescence: relations with social and school adjustments. PloS One. (2014) 9:e95290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095290

63. Tang W, Wang G, Hu T, Dai Q, Xu J, Yang Y, et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems among Chinese left-behind children: A cross-sectional comparative study. J Affect Disord. (2018) 241:133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.017

64. Wang J, Zou J, Luo J, Liu H, Yang Q, Ouyang Y, et al. Mental health symptoms among rural adolescents with different parental migration experiences: A cross-sectional study in China. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 279:222–30. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.004

65. Wang Z, Chen X, Liu J, Bullock A, Li D, Chen X, et al. Moderating role of conflict resolution strategies in the links between peer victimization and psychological adjustment among youth. J Adolesc. (2020) 79:184–92. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.002

66. Xiong Y, Wang H, Wang Q, Liu X. Peer victimization, maternal control, and adjustment problems among left-behind adolescents from father-migrant/mother caregiver families. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2019) 12:961–71. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S219249

67. Yeh YC, Huang MF, Wu YY, Hu HF, Yen CF. Pain, bullying involvement, and mental health problems among children and adolescents with ADHD in Taiwan. J Atten Disord. (2019) 23:809–16. doi: 10.1177/1087054717724514

68. Yen CF, Yang P, Wang PW, Lin HC, Liu TL, Wu YY, et al. Association between school bullying levels/types and mental health problems among Taiwanese adolescents. Compr Psychiatry. (2014) 55:405–13. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.06.001

69. Yen CF, Liu TL, Ko CH, Wu YY, Cheng CP. Mediating effects of bullying involvement on the relationship of body mass index with social phobia, depression, suicidality, and self-esteem and sex differences in adolescents in Taiwan. Child Abuse Negl. (2014) 38:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.015

70. Yen CF, Chou WJ, Liu TL, Ko CH, Yang P, Hu HF. Cyberbullying among male adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: prevalence, correlates, and association with poor mental health status. Res Dev Disabil. (2014) 35:3543–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.08.035

71. Yin XQ, Wang LH, Zhang GD, Liang XB, Li J, Zimmerman MA, et al. The promotive effects of peer support and active coping on the relationship between bullying victimization and depression among chinese boarding students. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 256:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.037

72. Yun I, Kim SG. Bullying among South Korean adolescents: prevalence and association with psychological adjustment. Violence Vict. (2016) 31:167–84. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-13-00138

73. Zhou Z-K, Liu Q-Q, Niu G-F, Sun X-J, Fan C-Y. Bullying victimization and depression in Chinese children: A moderated mediation model of resilience and mindfulness. Pers Individ Dif. (2017) 104:137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.040

74. Pan SW, Spittal PM. Health effects of perceived racial and religious bullying among urban adolescents in China: a cross-sectional national study. Glob Public Health. (2013) 8:685–97. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2013.799218

75. Zhao M, Xiao D, Wang W, Wu R, Zhang W, Guo L, et al. Association among maltreatment, bullying and mental health, risk behavior and sexual attraction in Chinese students. Acad Pediatr. (2021) 21:849–57. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.11.024

76. Mei S, Hu Y, Sun M, Fei J, Li C, Liang L, et al. Association between bullying victimization and symptoms of depression among adolescents: a moderated mediation analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:3316. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063316

77. Lai W, Li W, Guo L, Wang W, Xu K, Dou Q, et al. Association between bullying victimization, coping style, and mental health problems among Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. (2023) 324:379–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.080

78. Liu X, Peng C, Yu Y, Yang M, Qing Z, Qiu X, et al. Association between sub-types of sibling bullying and mental health distress among Chinese children and adolescents. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:368. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00368

79. Guo Y, Tan X, Zhu QJ. Chains of tragedy: The impact of bullying victimization on mental health through mediating role of aggressive behavior and perceived social support. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:988003. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.988003

80. Peng C, Wang Z, Yu Y, Cheng J, Qiu X, Liu X. Co-occurrence of sibling and peer bullying victimization and depression and anxiety among Chinese adolescents: The role of sexual orientation. Child Abuse Negl. (2022) 131:105684. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105684

81. Zhu Y, Xiao C, Chen Q, Wu Q, Zhu B. Health effects of repeated victimization among school-aged adolescents in six major cities in China. Child Abuse Negl. (2020) 108:104654. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104654

82. Wen Y, Zhu X, Haegele JA, Yu F. Mental health, bullying, and victimization among Chinese adolescents. Children. (2022) 9:240. doi: 10.3390/children9020240

83. Zhu Y, Li W, O’Brien JE, Liu T. Parent–child attachment moderates the associations between cyberbullying victimization and adolescents’ health/mental health problems: An exploration of cyberbullying victimization among Chinese adolescents. J interpersonal violence. (2021) 36:NP9272–98. doi: 10.1177/0886260519854559

84. Cao R, Gao T, Ren H, Hu Y, Qin Z, Liang L, et al. The relationship between bullying victimization and depression in adolescents: multiple mediating effects of internet addiction and sleep quality. Psychology Health Med. (2021) 26:555–65. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1770814

85. Liu X, Yang Z, Yang M, Ighaede-Edwards IG, Wu F, Liu Q, et al. The relationship between school bullying victimization and mental health among high school sexual minority students in China: A cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. (2023) 334:69. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.054

86. Fan H, Xue L, Zhang J, Qiu S, Chen L, Liu S. Victimization and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. J Affect Disord. (2021) 294:375–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.022

87. Biswas T, Scott JG, Munir K, Thomas HJ, Huda MM, Hasan MM, et al. Global variation in the prevalence of bullying victimisation amongst adolescents: Role of peer and parental supports. EClinicalMedicine. (2020) 20:100276. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100276

88. Barzilay S, Brunstein Klomek A, Apter A, Carli V, Wasserman C, Hadlaczky G, et al. Bullying victimization and suicide ideation and behavior among adolescents in europe: A 10-country study. J Adolesc Health. (2017) 61:179–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.002

89. U.S. Department of Education. Bullying (2021). USA: National Center for Education Statistics. Available online at: https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=719 (Accessed April 20, 2023).

90. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. School violence and bullying a major global issue, new UNESCO publication finds (2019). France: UNESCO. Available online at: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/school-violence-and-bullying-major-global-issue-new-unesco-publication-finds (Accessed April 20, 2023).

91. Nansel TR, Craig W, Overpeck MD, Saluja G, Ruan WJ, Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Bullying Analyses Working Group. Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2004) 158:730–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.730

92. Hamburger ME, Basile KC, Vivolo AM. Measuring Bullying Victimization, Perpetration, and Bystander Experiences: A Compendium of Assessment Tools. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2011).