- 1Louis and Gabi Weisfeld School of Social Work, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel

- 2Division for Ethics in Medicine, Department for Health Services Research, School VI - Medicine and Health Sciences, Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany

- 3Division for Prevention and Rehabilitation Research, Department for Health Services Research, School VI - Medicine and Health Sciences, Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany

Background: The global rise in dementia among older adults has led to an increased reliance on migrant live-in caregivers, particularly in countries like Germany and Israel. This triadic care arrangement, involving persons with dementia, their families, and migrant live-in caregivers, presents unique challenges and vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities, deeply intertwined with ethical concerns, are shaped by the socio-cultural and legal contexts of each country. This study aims to explore these vulnerabilities through a comparative analysis of expert experiences in Germany and Israel.

Method: A qualitative study was conducted using semi-structured interviews with 24 experts—14 from Israel and 10 from Germany—who have extensive experience in dementia care or migrant caregiving. The interviews were analyzed through qualitative content analysis, focusing on six dimensions of vulnerability: physical, psychological, relational/interpersonal, moral, socio-cultural-political-economic, and existential/spiritual.

Results: The analysis revealed that all parties in the care triad—persons with dementia, migrant live-in caregivers, and family members—experience distinct yet interconnected vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities are deeply entangled, manifesting in complex, interrelated ways both within each party and between the different parties in this triadic arrangement. The study also highlighted both similarities and differences in expert experiences between Germany and Israel, reflecting the unique socio-cultural and legal contexts of each country.

Conclusions: The study underscores the multifaceted and interdependent nature of vulnerabilities in migrant live-in care arrangements for people with dementia. By comparing expert insights from Israel and Germany, the research highlights the critical role of national policies and cultural contexts in shaping these vulnerabilities, leading to distinct experiences and challenges in each country. Addressing these vulnerabilities is essential for improving the quality of care and the well-being of all parties involved in the triadic care arrangement.

1 Introduction

The phenomenon of demographic aging is closely linked with an increasing number of older individuals living with dementia who require care services. Currently, more than 55 million people worldwide are living with dementia, with nearly 10 million new cases emerging each year (1). This growing burden is both significant and concerning. In many Western countries, including Germany and Israel, a majority of people with dementia reside within their communities, receiving care primarily from family members, often supplemented by migrant live-in carers (2, 3), thereby creating a triadic care arrangement. Providing dementia care with the assistance of migrant live-in carers entails a multifaceted set of difficulties, possible conflicts, and vulnerabilities (4–7). Vulnerability is closely tied to ethical issues in migrant live-in care for people with dementia due to several key factors, e.g. protection of vulnerable groups -ensuring the welfare, rights, and dignity of vulnerable populations, such as people with dementia and migrant caregivers, is a fundamental ethical concern; risk of exploitation - migrant caregivers face potential exploitation, and people with dementia risk neglect, highlighting the need for ethical vigilance and protective measures; equity and justice -the reliance on migrant caregivers reflects deeper societal inequalities, raising ethical questions about the fair distribution of care responsibilities and resources (8).

This research offers a comparative perspective on the complexities of this triadic care arrangement and explores vulnerabilities for all parties involved (persons with dementia, family members, and migrant live-in carers) based on the experiences of experts in migrant live-in dementia care in Israel and Germany.

In the following sections, we will provide a background on migrant live-in care in Israel and Germany, elaborate on the issue of vulnerabilities in aged care and home-based dementia care with migrant live-in carers, and explain the rationale and importance of the present study.

1.1 Migrant live-in care for people with dementia in Israel and Germany

Migrant live-in care for people with dementia plays a critical role in supporting older individuals in both Israel and Germany. Despite many similarities and common challenges across nations, notable differences are primarily influenced by each country’s unique geographical and socio-cultural contexts and legal frameworks. In Israel, regulated by the Long-Term Care Insurance Program (LTIP) since 1988, the system promotes ‘aging in place’ through home-based care. Israel has over 73,633 migrant caregivers—59,254 documented and 14,379 undocumented—origating from countries like the Philippines, India, Sri Lanka, Uzbekistan, Moldova, and Ukraine (9). Recent reforms since 2018 have enhanced the flexibility of care options and facilitated the employment of migrant live-in carers (10, 11).

In contrast, Germany’s care sector, which relies on about 500,000 Eastern European caregivers, operates within a less regulated ‘grey’ market (12, 13). German families often engage caregivers through agencies that navigate strict employment laws, facilitating frequent caregiver rotations. This practice, influenced by legal constraints and caregivers’ preferences due to their geographical proximity to their home countries, allows for more flexible employment arrangements but leads to less stable care relationships compared to Israel’s more regulated approach (6). These differences in regulatory frameworks and policies significantly impact the experiences and challenges faced by migrant live-in carers, people with dementia, and their families.

1.2 Vulnerabilities in migrant home-based dementia care

Migrant live-in care arrangements for people with dementia involve complex interactions between care recipients, migrant live-in carers, and family members, leading to various challenges, potential moral conflicts, and vulnerabilities (14–16). Building upon the initial exploration of challenges and vulnerabilities in migrant live-in dementia care, it is essential to delve deeper into the concept of vulnerability itself. Vulnerability, as analyzed in various studies, is a multifaceted concept that encompasses different types, definitions, and categories (17–20). Basic human vulnerability refers to the inherent condition affecting all individuals due to their human nature, characterized by the universal experience of ‘human finitude’ and susceptibility to harm and injury (21, 22). Various approaches to the concept of vulnerability agree that while we all share a common vulnerability, this vulnerability is distributed differently across individuals. Universal vulnerability can become exacerbated in certain social, political, and other contexts (23). Specifically, situational vulnerability arises from specific external conditions—such as cultural, social, political, and economic factors—that render some individuals more susceptible to harm than others (24).

In the context of aged care, Sanchini and colleagues (25), based on the latest studies, proposed six dimensions of vulnerabilities for older people that characterize aged care. Physical vulnerability is observed in the bodily deterioration associated with aging, which can lead to conditions like frailty, illness, dementia, and disability. Psychological vulnerability encompasses mental health changes, diminishing intellectual functioning, and emotional factors such as the cumulative loss of loved ones and the absence of emotional support. Relational/interpersonal vulnerability highlights the impact of human interdependence and the potential for conflicts and miscommunications. Moral vulnerability concerns ethical dilemmas, respect for dignity, and the potential for infantilization and depersonalization of older adults. Socio-cultural, political, and economic vulnerabilities reflect discrimination, economic instability, and marginalization faced by older adults and their caregivers. Lastly, existential/spiritual vulnerability pertains to existential questions about identity, purpose, and finitude experienced more intensely by older adults. These dimensions also offer insights into the vulnerabilities of persons with dementia in home-based care. However, it is imperative to explore the vulnerabilities of all parties involved in the triadic care arrangement—persons with dementia, family members, and migrant live-in caregivers—to fully capture the scope of challenges they face. This comprehensive approach will provide a holistic understanding of the care arrangement and the dynamics within it.

1.3 Present study: rationale and research questions

This study focuses on the vulnerabilities in dementia home care with migrant live-in carers. Addressing these vulnerabilities is crucial for enhancing the well-being and safety of everyone in the care triad. These vulnerabilities can significantly impact the quality of care for persons with dementia. Understanding them, especially through experts’ experiences, will help identify systemic inequities and gaps, leading to more effective support systems and policies that improve conditions for migrant live-in carers, persons with dementia, and their families.

Experts provide comprehensive insights into these vulnerabilities, drawing on a broad spectrum of experiences and observations. This is especially valuable given the practical challenges of directly accessing the care triad, whose members may face barriers to participation due to privacy concerns, health issues, or legal constraints. Furthermore, as experts positioned within intermediate structures such as organizational, community, and policy frameworks (meso-level), they offer invaluable insights that bridge the micro-level of individual experiences and the macro-level of national policies.

In this study, we obtained information from interviews with experts in Israel and Germany. We focus on Germany and Israel due to their aging populations, high life expectancy, and increasing numbers of people with dementia. Both countries have national dementia plans (Israel, 2013; Germany, 2020) and a growing number of migrant caregivers (10, 26). Despite similarities as modern Western countries, they also differ culturally (e.g., Israel is more collectivistic, with closer family ties and greater reliance on groups (27) and geographically. These differences in socio-cultural and geographic settings impact the legal and practical aspects of migrant live-in care arrangements. For example, in Israel, migrant live-in caregivers reside with the person with dementia for extended periods, while in Germany, live-in caregivers typically stay for 2-3 months and are rotated. Focusing on experts’ experiences in these two countries may help identify common and unique vulnerabilities and deepen our understanding of the influence of different socio-cultural and policy contexts on these vulnerabilities. In addition, the focus of most existing studies on single-country contexts (7, 28–30) constrains our comprehension of how diverse cultural and policy environments affect the nature and scope of these vulnerabilities. Our research seeks to bridge these gaps through a comparative analysis between countries, aiming to enhance our understanding of vulnerabilities in home-based care settings across different cultural and policy backgrounds.

In this study, we aimed to answer two research questions:

1. According to experts’ experiences, what are the vulnerabilities of each party involved in triadic arrangements (person with dementia, migrant live-in caregiver, family member)?

2. What are the commonalities and differences in experts’ experiences regarding vulnerabilities inherent in migrant live-in care arrangements for people with dementia between Israel and Germany?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

A qualitative methodology using semi-structured interviews was adopted to elicit experts’ experiences regarding complexities and vulnerabilities in home-based migrant care arrangements for older people with dementia. The study protocol was approved by the Bar-Ilan University (062201, June 2022) and Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Ethics Committees (2022–049).

2.2 Sample composition and recruitment

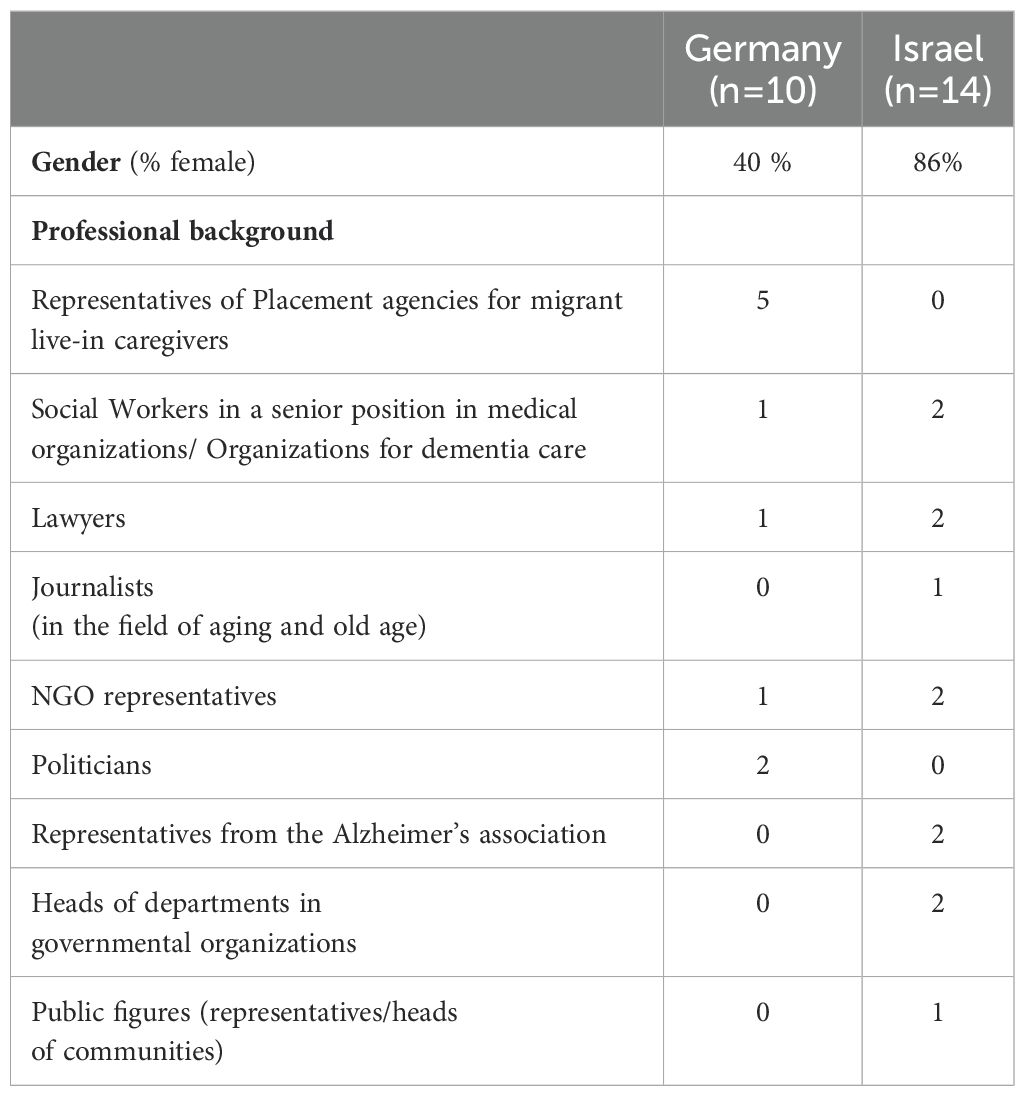

This study included 14 Israeli and 10 German participants. We defined “experts” as individuals meeting the following inclusion criteria: 1) holding a senior position in a governmental, political, or public setting; 2) having substantial knowledge and experience in the field of dementia care or migrant home care for older people/people with dementia, and 3) Being directly involved in the recruitment and monitoring of migrant caregivers, including representatives of placement agencies, care and welfare organizations, NGOs, human rights organizations, and governmental structures. For this study, we excluded individuals who: 1) do not have substantial experience in dementia care or migrant home care, and 2) hold positions that do not provide direct insight or influence in the field of dementia or migrant care. For more detailed information regarding the characteristics of the experts in Germany and Israel, see Table 1.

Purposive sampling was used in both countries. In Israel, experts were recruited via researchers’ professional and personal connections. Additionally, targeted outreach was conducted through email to key persons in the field of dementia home-based migrant care to achieve diversity regarding their professional expertise and positions. In Germany, several strategies were used. Participants were primarily recruited through email, e.g., all directors of placement agencies. Some of the directors were chosen based on their agency’s size and status. Politicians were contacted based on their importance in the field of aged care and on variance in their political orientation/party affiliation.

2.3 Procedure

All participants signed informed consent sheets prior to participating in the study. In Israel, 14 semi-structured interviews with experts were conducted using Zoom or video telephone call platforms from October 2022 to June 2023. In Germany, ten semi-structured interviews with experts were conducted using the video call platform Big Blue Button between August 2022 and January 2023.

The interviews were conducted following a semi-structured interview guideline, which was developed jointly by the research teams in both countries in English and later translated into Hebrew and German. Interviews started by asking the participants to describe their professional background and experience with migrant live-in care arrangements for people with dementia. This was followed by questions aimed at gaining the expert’s views regarding dementia home-based care (e.g., “How do you perceive this form of care in comparison to other forms of care, for example, home? “). In this particular study, we focused on challenging situations, conflicts, and vulnerabilities, asking experts, for instance, the following questions: “Do you recognize problematic power structures within the arrangements? “; “Do you see potential conflicts in live-in care arrangements?”; “Can you describe vulnerabilities in live-in care arrangements?”; “In your opinion, is there a side that is more vulnerable in these triadic arrangements, and if so, which side?”. Interviews lasted an average of 60 minutes both in Israel and Germany and were conducted by members of the research teams with experience in qualitative research.

2.4 Data analysis

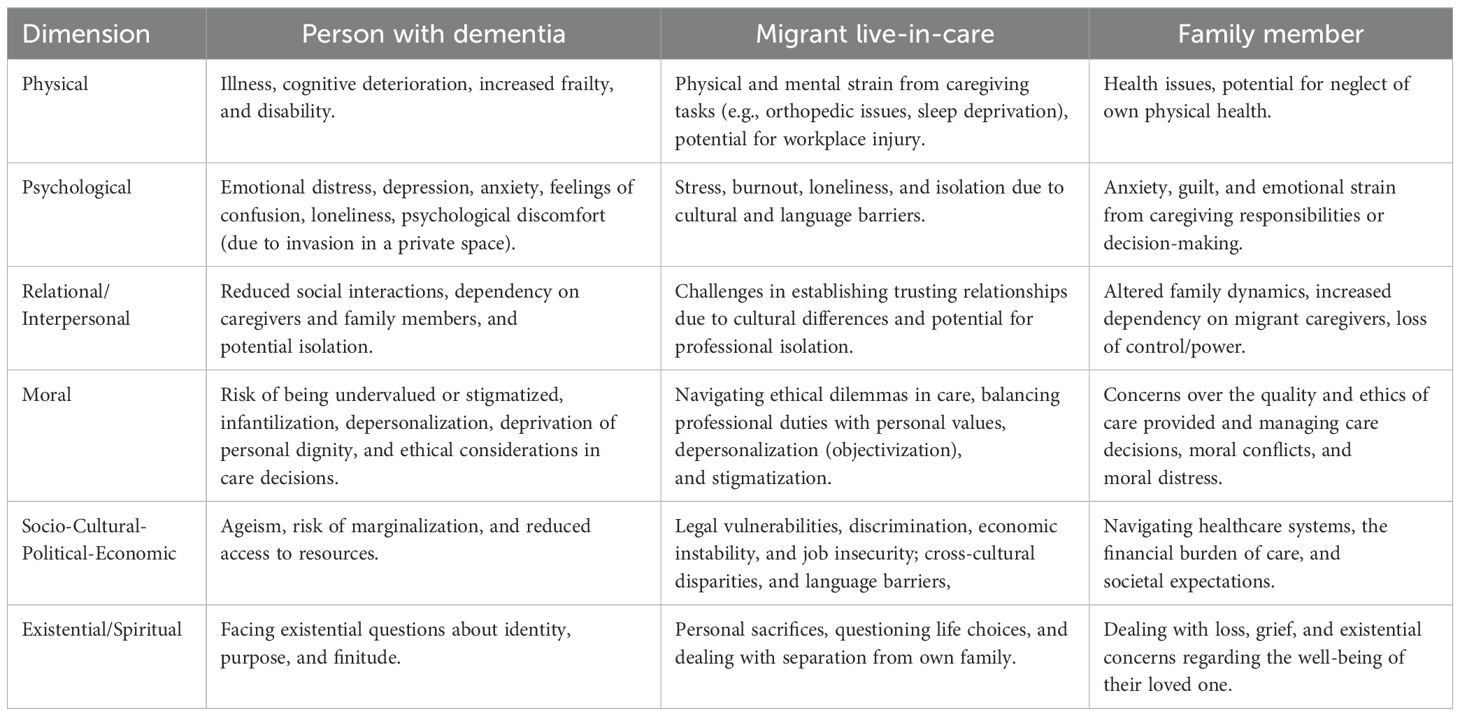

We employed a qualitative content analysis approach to ensure a thorough and nuanced examination of the expert interviews, following several steps outlined by Braun and Clark (31). The process began with verbatim transcription of the interviews, followed by multiple readings. Initially, guided by the study’s questions, we applied deductive coding to analyze expert interviews concerning the vulnerabilities of people with dementia, using a predefined set of categories based on the six dimensions of vulnerabilities in aged care identified in prior studies [e.g (32, 33)] and elaborated by Sanchini et al. (2022) (25). These dimensions (as mentioned in the introduction section) include: 1) physical, 2) psychological, 3) relational/interpersonal, 4) moral, 5) socio-cultural-political-economic, and 6) existential/spiritual. We used these six categories as a basis because they offer a comprehensive and up-to-date literature review-based view of the vulnerabilities of older people in need of care, including those with dementia. We chose to employ Sanchini’s and colleges’ framework (25), tailored initially to describe the vulnerabilities of older people in need of care and adapt it to all members of the triad because, to the best of our knowledge, no existing concept or model in eldercare comprehensively considers the vulnerabilities of all parties involved. This approach allowed us to systematically capture the multifaceted nature of vulnerabilities experienced by persons with dementia, their family members, and migrant live-in carers, providing a holistic understanding of the triadic care dynamics. For instance, the physical dimension of vulnerabilities for a person with dementia encompasses issues such as physical illness, cognitive decline or advanced dementia stages, increased frailty, and disability. In contrast, this dimension for migrant live-in caregivers might be expressed in physical and mental strain from caregiving tasks, including orthopedic problems, sleep deprivation, and the risk of workplace injuries. As for family members, this dimension of vulnerabilities may involve health issues and potential neglect of their own physical well-being.

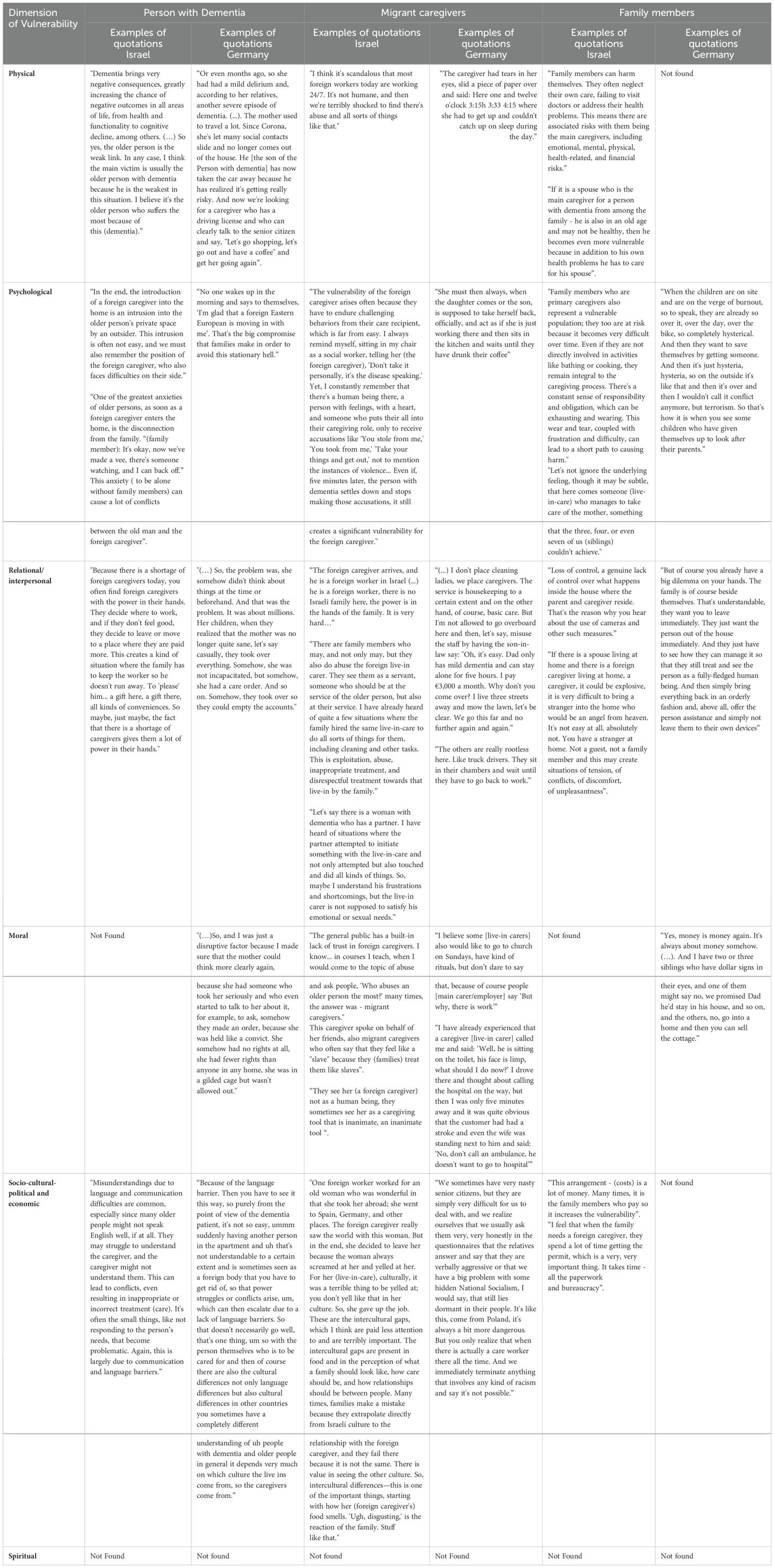

This framework, detailing vulnerability dimensions for each party, served as the main categories for discussion within and across research teams in both countries until a consensus on the coding structure was achieved. The final phase involved identifying quotes/statements within the interview material that support these categories (dimensions of vulnerabilities) for each party involved in the care triad. Due to space constraints, we present a detailed description of each dimension of vulnerability for each party in the triadic home-based care arrangement in Table 2, and we provide examples of relevant quotes from the expert interviews in Israel and Germany in Table 3.

Table 2. Dimensions of vulnerabilities in dementia home care for persons with dementia, migrant live-in carers and family members.

Table 3. Dimensions of vulnerabilities in triadic dementia home care arrangements accompanied by direct excerpts from experts’ interviews in Israel and Germany.

3 Results

In exploring the vulnerabilities within migrant live-in care arrangements for people with dementia across Israel and Germany based on experts’ experiences, it becomes apparent that, according to them, all parties involved are vulnerable in different ways and that some of these vulnerabilities are interdependent.

In general, Israeli experts highlight the complex nature of vulnerability, suggesting that it is difficult to pinpoint the most vulnerable group within the care triad. While the person with dementia is often perceived in public opinion as the most vulnerable, Israeli experts acknowledged that each party in the triad—persons with dementia, migrant live-in carers, and family members (both spouses and children)—faces unique challenges that can amplify their respective vulnerabilities depending on the context and specific circumstances. In contrast, German experts focused more on the vulnerabilities of migrant live-in carers, drawing attention to their exposure to discrimination, excessive working hours, and challenging working conditions coupled with a lack of autonomy. Interestingly, the vulnerabilities of family members received relatively less attention in interviews with German experts, possibly reflecting their less extensive involvement in the caregiving process compared to their Israeli counterparts.

In the following, we present different dimensions of vulnerabilities that emerged from the analysis of interviews with experts in Israel and Germany, noting commonalities and specificities between the two countries.

3.1 Dimensions of vulnerabilities for persons with dementia, migrant caregivers, and family members

3.1.1 Physical vulnerabilities

We identified various types of physical vulnerabilities that arise from the specific situations of each party in the caregiving triad. Israeli and German experts acknowledged these vulnerabilities for persons with dementia and migrant live-in carers, while only Israeli experts recognized them for family members. These vulnerabilities are partly interdependent and context-specific.

For persons with dementia, cognitive impairment significantly limits their physical and cognitive abilities, leading to considerable dependence on others and a diminished level of autonomy. This dependency is a primary reason for employing a migrant caregiver.

Migrant live-in carers, as acknowledged by both Israeli and German experts, face physical vulnerabilities resulting from the nature of their work, which includes managing the physical and behavioral symptoms of dementia. This can lead to chronic sleep deprivation, strenuous physical labor, and potential trauma from aggressive behaviors exhibited by older individuals with dementia.

Family members, even without direct physical involvement, may experience indirect physical vulnerabilities due to the caregiving burden. The physical and cognitive condition of their loved ones, coupled with the responsibility of coordinating care, can result in neglecting their own health, thus manifesting in a vulnerable physical state. However, it was observed that only Israeli experts, and not their German counterparts, highlighted the physical dimension of vulnerabilities among family members. This discrepancy could be influenced by cultural and geographical differences: for example, in Germany, a country much larger country in area than Israel, children often reside at a significant distance from their parents, resulting in less active involvement in caregiving. This geographical distance means that family members in Germany might not face the same physical strains of hands-on caregiving, potentially reducing their physical vulnerabilities. However, this can lead to other forms of vulnerability, such as emotional stress and anxiety, due to their inability to be physically present. In contrast, Israeli family members, who are more likely to live closer to their aging parents, are more actively involved in caregiving, which increases their physical vulnerabilities due to the direct physical demands and stresses of caregiving.

3.1.2 Psychological vulnerabilities

Drawing from insights provided by experts in Israel and Germany, we identified several types of psychological vulnerabilities affecting all parties within the caregiving triad. Similar to the previous dimension, these vulnerabilities stem from the unique circumstances each party faces and are often interrelated.

For persons with dementia, experts from both Germany and Israel noted that the discomfort of welcoming a foreign caregiver into their home can lead to emotional stress and feelings of intrusion into their personal space, as well as an increased awareness of their dependency.

Migrant live-in-carers face psychological vulnerabilities resulting from being in a stranger’s private space in a foreign country and adapting to an unfamiliar culture. They might experience additional emotional stress due to separation from their families and being out of their comfort zone. German and Israeli experts both highlighted the psychological harm migrant caregivers may suffer. For instance, Israeli experts noted unfounded accusations of theft or violence from the person with dementia they care for, while German experts observed feelings of being belittled due to their status.

Family members also experience psychological vulnerabilities. The psychological strain of caregiving was recognized by experts in both Germany and Israel. Additionally, Israeli experts pointed out the complex emotions family members might experience, such as guilt and jealousy, due to hiring foreign caregivers, reflecting on their perceived inadequacies in providing care.

3.1.3 Relational/interpersonal vulnerabilities

This dimension focuses on human interdependence, resulting in vulnerabilities. For individuals with dementia, their condition necessitates reliance on migrant caregivers and family members, who then overtly or covertly take up decision-making roles. Israeli experts have noted that due to a scarcity of migrant caregivers, these caregivers gain disproportionate power and may abruptly leave the person with dementia, possibly without notice, if they find better pay elsewhere. German experts emphasized the loss of autonomy and the dependence of a person with dementia on their adult children, who can sometimes abuse this power, leading to moral vulnerability, which will be described in the next section. This paternalism on the part of the children, which may stem from genuine concern or from a belief that a parent has lost the capacity to make decisions, can result in the denial of rights and a lack of consideration, turning the person into a “prisoner in their own house.”

Concerning migrant live-in carers, their relational/interpersonal vulnerabilities are linked to complex relationships with family members who inherently hold more control and power, potential exploitation and even sexual abuse, and loneliness stemming from being in an unfamiliar environment. Both Israeli and German experts acknowledged these issues.

Regarding family members, both Israeli and German experts highlighted the loss of control that adult children experience over what happens inside the house. Israeli experts noted that this has led to the adoption of surveillance cameras to monitor caregiving, while German experts reported cases of migrant live-in carers engaging in inappropriate behaviors, such as excessive alcohol consumption, which initially went unnoticed by relatives. This situation places family members in a moral quandary, as they feel compelled to protect the rights of the live-in caregiver, despite any misconduct, rather than terminating their employment hastily. Additionally, Israeli experts pointed out spouses’ discomfort with entrusting their homes to an “outsider,” which can also be challenging for them. These observations reflect the complex dynamics of trust, control, and vulnerability that characterize the caregiving relationship.

3.1.4 Moral vulnerabilities

This dimension encompasses vulnerabilities within live-in care arrangements that are tied to overarching norms and values. These might be expressed as the risk of being stigmatized and undervalued for persons with dementia and migrant live-in carers, ethical dilemmas in care for migrant live-in carers, and family members’ concerns over ethics and quality of care for their loved ones.

For migrant live-in carers, Israeli experts describe depersonalization and their treatment by family members not as human beings but as tools to achieve a goal—referred to as the “objectification” of live-in carers or treatment of them as “slaves.” Furthermore, influenced by portrayals in public media regarding evidence of abuse of older people by migrant caregivers, live-in carers in Israel may experience public stigmatization and a built-in lack of trust from society, including family members and older persons- recipients of care. In Germany, experts highlight the moral dilemmas faced by live-in carers, who struggle to take time off due to the constant demands of their responsibilities, whether caring for a person with dementia or managing household tasks. In emergency situations, these caregivers must make rapid decisions about the health of the person with dementia, balancing not only the wishes of the individual but also those of the family members.

For persons with dementia, German experts point out specific moral vulnerabilities for them. They noted that cognitive decline and dependence of the person lead to their devaluation by family members, financial exploitation, deprivation of rights, and inability to take part in decisions regarding their own care.

For family members, German experts noted moral vulnerabilities that might arise when several siblings are involved. Financial disagreements between them may lead to ethical concerns and dilemmas about whether the parent’s funds should be viewed as a potential inheritance for them (the children) or if they should be allocated toward care expenses, such as employing a migrant live-in carer.

Notably, Israeli experts did not mention these particular moral vulnerabilities concerning persons with dementia or their family members.

3.1.5 Socio-cultural, political, and economic vulnerabilities

These vulnerabilities refer to the risk of marginalization and reduced access to resources for persons with dementia; discrimination, economic instability, and job insecurity for migrant live-in carers; and the financial burden of care and societal expectations for family members. Both Israeli and German experts identified language barriers and cultural disparities between the person with dementia and the live-in carer as sources of clashes, misunderstandings, and conflicts that may lead to such vulnerabilities in the caregiving setting. Accounts range from persons with dementia feeling estranged in their own homes to the neglect of their needs and even power struggles that may escalate, leaving both parties feeling disregarded. The inability of persons with dementia to effectively communicate their needs and the inability of migrant live-in carers to understand and respond to these needs, coupled with existential interdependence, renders both parties vulnerable. Experts in both Israel and Germany also stressed that cultural differences contribute to these vulnerabilities. Live-in carers may feel unwelcome or even harassed due to these cultural differences. German experts specifically addressed covert racist attitudes toward Polish live-in carers from the care recipient’s side.

Regarding family members, German experts, except for indirectly mentioning workload, do not explicitly address vulnerabilities. However, Israeli experts recognize the financial constraints and bureaucratic challenges faced by family members as significant vulnerabilities.

3.1.6 Spiritual vulnerabilities

This dimension remained unaddressed by experts in both countries in our study.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to comprehensively understand the vulnerabilities within the triad of dementia home-based care with migrant live-in caregivers, focusing on persons with dementia, live-in caregivers, and family members based on experts’ experiences in Israel and Germany. The relationships in home care arrangements with migrant live-in caregivers are complex and characterized by significant interdependence; each member of this triad relies on the others for their well-being in crucial ways (34). The exploration of vulnerabilities within this triadic setting, based on interviews with experts from Israel and Germany, reveals the multifaceted nature of this caregiving environment and its dynamics.

The complexities of vulnerabilities within the care triad were widely acknowledged. Israeli experts emphasized the intricate nature of these vulnerabilities. Contrary to the popular opinion among the general public and professionals, which often views the person with dementia as the most vulnerable member of the triad due to their health and mental condition (35), Israeli experts did not identify any particular side of the triad as the most vulnerable. Instead, they noted that vulnerabilities are present in all parties involved, stemming from their unique situations. Each party faces distinct challenges that can increase their vulnerability in specific contexts, making these vulnerabilities inherent to the triadic care arrangement. This aligns with existing literature that acknowledges different conditions leading to vulnerabilities: asymmetrical power relations and the intersection of ethnicity, culture, class, and legal status for migrant care workers; the poor physical and cognitive condition of people with dementia; and the emotional and physical burden experienced by family members (28, 36–38). However, German experts placed significant emphasis on the vulnerability of migrant live-in caregivers, highlighting their susceptibility to discrimination, excessive working hours, and challenging conditions.

The relatively lesser focus on family members’ vulnerabilities in Germany may be influenced by several socio-cultural factors, such as fewer children per family, greater geographic distance from parents, and more remote involvement in caregiving. These factors suggest a divergence in familial engagement between the two countries. However, it is important to note that these interpretations are derived from our analysis and were not explicitly probed during the interviews. Explicitly addressing this question with the experts could have provided deeper insights into these dynamics, and we recommend this for future research. Another explanation may be the different expectations in the two countries regarding family involvement in care, as Israel’s more collectivistic culture involves closer family ties (27), leading to greater family involvement in care.

In general, five of the six dimensions, except for spiritual vulnerability, were acknowledged by Israeli and German experts as relevant to all parties involved in triadic dementia home care arrangements. However, these vulnerabilities differ for each party according to their specific situations. While physical and psychological vulnerabilities are universally recognized, the emphasis on relational and moral vulnerabilities varies. Israeli experts noted the power dynamics and potential exploitation of migrant caregivers within the caregiving arrangement. This observation aligns with recent studies highlighting how relationships within the care triad can sometimes be discriminatory, reflecting power imbalances and the vulnerability of migrant live-in caregivers (7, 10). In contrast, German experts highlighted the moral dilemmas and decision-making challenges faced by migrant caregivers, underscoring the ethical complexities inherent in caregiving. Interestingly, the moral vulnerability dimension for a person with dementia was acknowledged by German experts but not by Israeli experts, potentially indicating a greater awareness in Germany of preserving the autonomy of people with dementia and probably a lower level of public stigma surrounding the condition. Supporting this, a study found that only 4% of the German population over the age of 50 reported fear of people with dementia, while over 80% expressed no fear, indicating relatively low levels of stigma in Germany (39). This could also stem from the more autonomy-oriented orientation of German society (27, 40).

Our findings also indicate a gap in addressing existential and spiritual vulnerabilities, suggesting that these aspects are often overshadowed by more immediate practical and ethical concerns. This oversight points to a potential area for further research and intervention, recognizing that spiritual well-being significantly impacts the quality of life for all parties involved (41).

In a comparative view, our analysis also showed that home care arrangements for people with dementia, along with the complex vulnerabilities for all parties involved, are significantly influenced by the legal policies specific to each country. These policies distinctly shape the vulnerabilities experienced by each party. For example, in Israel, a shortage of caregivers allows them to switch families for better pay, leading to concerns about caregivers gaining disproportionate power and potentially leaving their positions abruptly. Conversely, in Germany, while family members may wish to quickly dismiss a live-in caregiver for inappropriate behavior or keep them longer, they are constrained by legal policies requiring caregivers to rotate every three months. Such differing policies highlight the variations in how care arrangements are managed across these countries, underlining the distinct vulnerabilities that arise in Israel and Germany.

4.1 Entangled vulnerabilities in dementia care triads

This study aimed to deepen our understanding of the various vulnerabilities present in home care arrangements for people with dementia involving migrant live-in caregivers. We introduced a theoretical framework that distinguishes between different dimensions of vulnerability to address the challenges faced by each side of the triadic care relationship. However, the complex reality of caregiving—where individuals with varying health conditions, economic and legal statuses, cultural backgrounds, and generational differences interact within intricate human relationships—often results in these vulnerabilities becoming entangled, complicated, and interrelated. While previous studies have acknowledged the existence of vulnerabilities within home care arrangements, they typically addressed these vulnerabilities in isolation for each party involved (5, 42–44). Based on our findings, we propose viewing these vulnerabilities as entangled, interconnected, and interdependent rather than separate, highlighting the need for a more holistic approach to understanding and addressing them.

Interrelations within a single party of the triad refer to how different dimensions of vulnerability intersect and reinforce each other. For instance, our findings indicate that the “relational/interpersonal dimension of vulnerability” for a person with dementia can intensify their moral vulnerability. As German experts highlighted, when a person with dementia becomes increasingly dependent on others, they may lose autonomy, leading to a sense of diminished dignity. Similarly, Israeli experts revealed that the psychological vulnerability of family members, burdened by the responsibilities of caring for a parent with dementia and managing the relationship with a foreign caregiver, can manifest in physical vulnerability, such as neglecting their own health due to caregiving stress.

The interrelations of vulnerabilities between the parties of the triad highlight the entangled dependencies within the caregiving arrangement. For example, the physical vulnerability of a person with dementia, exacerbated by rapid health deterioration, can lead to increased physical or psychological strain on migrant live-in caregivers. These caregivers may face more demanding physical care tasks or suffer from sleep deprivation due to nighttime caregiving, leading to stress and burnout. This situation, in turn, can heighten the vulnerabilities of family members, who may experience increased stress, greater dependency on the caregiver, and concerns over care decisions, such as whether to continue with live-in care or opt for institutional care. Moreover, the socio-cultural, political, and economic vulnerabilities of migrant caregivers—who often occupy a lower position in terms of resources and power—are intricately linked to the vulnerabilities of family members, who bear the financial burden of employing a migrant caregiver. Language barriers, a form of psychological vulnerability, further complicate communication between all parties, leading to misunderstandings that affect the quality of care. For example, when people with dementia struggle to express their needs due to language differences, the caregiver’s ability to provide appropriate care is compromised, causing emotional stress and concerns over care quality among family members. In another example, the physical and cognitive decline of a person with dementia can create moral dilemmas for family members, who may face difficult decisions regarding care budgets and sibling relationships. These moral vulnerabilities can, in turn, influence the economic vulnerabilities of live-in caregivers, who might experience job insecurity based on the family’s decisions.

5 Conclusions

In summarizing our study, we can conclude that our research revealed multifaceted and interrelated vulnerabilities in dementia care arrangements with migrant live-in caregivers, illustrating the depth and complexity of the challenges faced by all parties involved in the triadic care arrangement. Furthermore, our findings emphasize the significant role of meso- and macro-level factors in shaping these vulnerabilities. By adopting a comparative research perspective, we have been able to identify how different socio-cultural and legal contexts influence the dynamics of these vulnerabilities.

For example, at the meso-level, the organizational structures within the care systems of Israel and Germany play a critical role in shaping the experiences of vulnerability for each party. In Israel, where migrant live-in caregivers reside with care recipients on a permanent basis, the constant presence of the caregiver can lead to a blurring of professional and personal boundaries. This close proximity might increase the relational vulnerability for both the caregiver and the care recipient, as tensions may arise from continuous interaction without sufficient breaks. Additionally, this setup can exacerbate the psychological vulnerability of caregivers due to the potential for burnout from being on call 24/7, while care recipients might feel a loss of privacy and autonomy in their own homes. In Germany, the less regulated grey market of migrant caregiving, where many caregivers are hired through agencies that navigate strict employment laws, creates a different set of challenges. The frequent rotation of caregivers, as required by German policies, disrupts the continuity of care, exacerbating the psychological vulnerability of both the person with dementia and the family members, who may struggle to build trust with constantly changing caregivers. This rotation system, while intended to protect caregivers from exploitation, can inadvertently lead to a lack of stability in care, highlighting how macro-level legal frameworks directly influence the relational and psychological vulnerabilities within the triad.

At the macro-level, broader socio-cultural and legal factors also play a pivotal role. For instance, Israel’s collectivistic culture, which emphasizes close family ties and a strong sense of responsibility toward older family members, often leads to higher involvement of family members in the caregiving process. This cultural expectation can heighten the physical and psychological vulnerabilities of family members, who may feel obligated to take on more significant caregiving responsibilities despite the presence of a live-in caregiver. In contrast, Germany’s more individualistic culture, where families are often geographically dispersed, reduces direct family involvement in daily caregiving tasks. While this can lessen the physical strain on family members, it can increase their psychological and emotional vulnerabilities due to feelings of guilt or helplessness when they cannot be physically present to care for their loved ones. This geographical and cultural distance can also create a sense of isolation for the person with dementia, as their primary emotional support system is not immediately available, further complicating their psychological and relational vulnerabilities.

These examples demonstrate how the interplay between meso- and macro-level factors, including organizational structures, legal frameworks, and cultural contexts, profoundly shapes the vulnerabilities experienced by each party in the triadic care arrangement. Understanding these complexities is essential for developing targeted interventions and policies that address the specific needs of each party involved, ultimately leading to improved care strategies in diverse socio-political environments.

6 Study limitations and strengths

The present study is not without its limitations. Firstly, the number of participants was relatively small, and the composition of the sample differed between Israel and Germany. However, these differences reflect the distinct organization of live-in care arrangements in each country. The German sample predominantly consisted of directors of placement agencies, who play a significant role in the migrant home care framework, while the Israeli sample included many social workers responsible for monitoring live-in care arrangements, as the employment of migrant live-in caregivers in Israel often relies on care recipients or family members.

Additionally, while the study mentions the country of origin of migrant caregivers, future studies could examine how the caregivers’ different cultural and socio-economic backgrounds influence the care dynamic, including vulnerabilities and resilience strategies within the triadic care arrangement.

Secondly, the findings of this study may not be generalizable to all settings or populations. Nevertheless, the comparative design allowed us to identify the influence of contextual factors, such as cultural and policy environments, on vulnerabilities in triadic care arrangements—insights that might not have emerged if the study had been conducted in only one country.

Thirdly, our study exclusively involved experts in the field, relying on their experiences as informants. While this is crucial for understanding the vulnerabilities of all parties from an intermediary perspective (between micro- and macro-levels), it is also a limitation. This choice was deliberate, as experts are uniquely positioned to synthesize diverse experiences and provide critical insights into systemic and policy-level complexities. To complement these findings, we have conducted interviews with individuals directly involved in triadic care arrangements across different countries. These interviews aim to provide a more direct and comprehensive perspective on vulnerabilities and care dynamics. We plan to publish these findings separately.

Despite its limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the complexities and vulnerabilities associated with migrant live-in care arrangements for people with dementia in Germany and Israel. Through comparative analysis, we identified both common and unique vulnerabilities within the caregiving triad, significantly shaped by the differing cultural and legal frameworks of the two countries. The proposed framework of vulnerability dimensions deepens our understanding of the challenges faced by each party, while the discussion of the interdependencies of these vulnerabilities’ sheds light on their deeply entangled nature.

While vulnerability is an ontological or universal condition inherent in human beings (21, 23), we strive to reduce these conditions as much as possible. Therefore, understanding these vulnerabilities within migrant live-in care settings is crucial for developing effective interventions that improve the well-being of all parties involved. This study contributes to the broader discourse on dementia care ethics and offers actionable insights for policymakers, care practitioners, and families, paving the way for improved care strategies in diverse socio-political contexts.

Data availability statement

Due to ethical considerations and participant confidentiality, the datasets from this study are not publicly accessible. Access to anonymized data may be granted upon request, pending approval from the relevant ethics committee.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Bar-Ilan University, Israel (062201, June 2022); Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, Germany (2022-049). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

NU: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LA: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research project MoDeCare (Moral conflicts in familial dementia care involving migrant live-in carers in Germany and Israel: A comparative-ethical exploration and analysis) is funded by The Volkswagen Foundation, grant number 11-76251-2684/2021 ZN 3864.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization. Fact sheets of dementia. Geneva: World Health Organization (2024). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (Accessed June 2, 2024).

2. Van Hooren FJ. Varieties of migrant care work: Comparing patterns of migrant labor in social care. J Eur Soc Policy. (2012) 22:133–47. doi: 10.1177/0958928711433654

3. Bentur N, Sternberg SA. Dementia care in Israel: top-down and bottom-up processes. Isr J Health Policy Res. (2019) 8:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13584-019-0290-z

4. Ayalon L. Evaluating the working conditions and exposure to abuse of Filipino home care workers in Israel: Characteristics and clinical correlates. Int Psychogeriatr. (2009) 21:40–9. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208008090

5. Green O, Ayalon L. Violations of workers’ rights and exposure to work-related abuse of live-in migrant and live-out local home care workers–a preliminary study: implications for health policy and practice. Isr J Health Policy Res. (2018) 7:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13584-018-0224-1

6. Kuhn E, Seidlein AH. Ethical harms for migrant 24h caregivers in home care arrangements. Nurs Ethics. (2023) 30:382–93. doi: 10.1177/09697330221122903

7. Teshuva K, Cohen-Mansfield J, Iecovich E, Golander H. Like one of the family? Understanding relationships between migrant live-in care workers and older care recipients in Israel. Ageing Soc. (2019) 39:1387–408. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X1800003X

8. King-Dejardin A. The social construction of migrant care work: At the intersection of care migration and gender. Int Labour Organ Rep. (2019) 42:978–92. Available online at: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/working-papers/WCMS_674622/lang--en/index.htm (Accessed June 5, 2024).

9. Israel Population and Immigration Authority. Data on Foreigners in Israel. Hebrew (2022). Available online at: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/foreign_workers_stats/he/zarim_2021.pdf (Accessed June 5, 2024).

10. Cohen-Mansfield J, Golander H. Bound in an imbalanced relationship: Family caregivers and migrant live-in care-workers of frail older persons in Israel. Qual Health Res. (2023) 33:1116–30. doi: 10.1177/10497323231186108

11. Kushnirovich N, Raijman R. Bilateral agreements, precarious work, and the vulnerability of migrant workers in Israel. Theor Inq Law. (2022) 23:266–88. doi: 10.1515/til-2022-0019

12. Lutz H. Die Hinterbühne der Care-Arbeit: Transnationale Perspektiven auf Care-Migration im geteilten Europa. Weinheim Basel: Beltz Juventa (2018).

13. Leiber S, Rossow V. Self-regulation in a grey market? Insights from the emerging Polish-German business field of live-in care brokerage. In: Kuhlmann J, Nullmeier F, editors. The Global Old Age Care Industry: Tapping into migrants for tackling the old age care crisis. Springer, Singapore (2021). p. 127–52.

14. Arieli D, Yassour-Borochowitz D. Decent care and decent employment: family caregivers, migrant care workers, and moral dilemmas. Ethics Behav. (2024) 34:314–26. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2023.2212822

15. Gerhards S, Kutzleben MV, Schweda M. Moral issues of live-in care by Eastern European care workers for people with dementia: an ethical analysis of relatives' expectations in online forums. Ethik Med. (2022) 34:573. doi: 10.1007/s00481-022-00708-8

16. Cohen-Mansfield J, Jensen B, Golander H, Iecovich E. Recommended vs. reported working conditions & current satisfaction levels among migrant caregivers in Israel. J Popul Ageing. (2017) 10:363–83. doi: 10.1007/s12062-016-9170-2

17. Bozzaro C, Boldt J, Schweda M. Are older people a vulnerable group? Philosophical and bioethical perspectives on ageing and vulnerability. Bioethics. (2018) 32:233–39. doi: 10.1111/bioe.2018.32.issue-4

18. Have H. Respect for human vulnerability: the emergence of a new principle in bioethics. J Bioeth Inq. (2015) 12:395–408. doi: 10.1007/s11673-015-9648-1

19. Hurst SA. Vulnerability in research and health care: Describing the elephant in the room? Bioethics. (2008) 22:191–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00631.x

20. Rogers W, Mackenzie C, Dodds S. Why bioethics needs a concept of vulnerability. Int J Fem Approaches Bioeth. (2012) 5:11–38. doi: 10.3138/ijfab.5.2.11

21. Fineman MA. The vulnerable subject: Anchoring equality in the human condition. In: Fineman MA, ed. Transcend Bound Law. Routledge-Cavendish. (2010) 2010:161–75. doi: 10.4324/9780203848531-26

22. Schroeder D, Gefenas E. Vulnerability: too vague and too broad? Camb Q Healthc Ethics. (2009) 18:113–21. doi: 10.1017/S0963180109090203

23. Rodríguez JD. The relevance of the ethics of vulnerability in bioethics. Les ateliers l’éthique/The Ethics Forum. (2017) 12:154–79. doi: 10.7202/1051280ar

24. Mackenzie C, Rogers W, Dodds S. Introduction: What is vulnerability and why does it matter for moral theory. In: Mackenzie C, Rogers W, Dodds S, editors. Vulnerability: New essays in ethics and feminist philosophy. Oxford University Press, New York (2014). p. 1–29.

25. Sanchini V, Sala R, Gastmans C. The concept of vulnerability in aged care: a systematic review of argument-based ethics literature. BMC Med Ethics. (2022) 23:84. doi: 10.1186/s12910-022-00819-3

26. Safuta A, Noack K, Gottschall K, Rothgang H. Migrants to the rescue? Care workforce migrantisation on the example of elder care in Germany. In: Kuhlmann J, Nullmeier F, editors. Causal Mechanisms in the Global Development of Social Policies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham (2022). p. 219–42.

27. Hofstede Insights. Country comparison: Israel and Germany. Hofstede Insights website. Available online at: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/israel,germany/ (Accessed May 2, 2024).

28. Arieli D, Halevi Hochwald I. Family caregivers as employers of migrant live-in care workers: Experiences and policy implications. J Aging Soc Policy. (2023) 36(4):639–57. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2023.2238535

29. Rogalewski A, Florek K. The future of live-in care work in Europe: Report on the EESC country visits to the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and Poland following up on the EESC opinion on “The rights of live-in care workers. European Economic and Social Committee (2020). Available online at: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/files/report_on_the_eesc_country_visits_to_uk_Germany_Italy_Poland_0.pdf (Accessed July 21, 2024).

30. Chaouni SB, Smetcoren AS, De Donder L. Caring for migrant older Moroccans with dementia in Belgium as a complex and dynamic transnational network of informal and professional care: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. (2020) 101:103413. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103413

31. Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: Cooper H, Camic PM, Long DL, Panter AT, Rindskopf D, Sher KJ, eds. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. Am Psychol Assoc. (2012) 2:57–71. doi: 10.1037/13620-004

32. Blasimme A. Physical frailty, sarcopenia, and the enablement of autonomy: philosophical issues in geriatric medicine. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2017) 29:59–63. doi: 10.1007/s40520-016-0714-3

33. Van der Meide H, Olthuis G, Leget C. Why frailty needs vulnerability: a care ethical perspective on hospital care for older patients. Nurs Ethics. (2015) 22:860–9. doi: 10.1177/0969733014557138

34. Arieli D. Foreign Intimacy: Our parents, the people who care for them, and us. Tel Aviv: Orion Publishers (2021).

35. Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. (2019) 394:1365–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31786-6

36. Bélanger D, Silvey R. An im/mobility turn: power geometries of care and migration. J Ethn Migr Stud. (2020) 46:3423–40. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1592396

37. Green G, Halevi Hochwald I, Radomyslsky Z, Nissanholtz-Gannot R. Family caregiver’s depression, confidence, satisfaction, and burden regarding end-of-life home care for people with end-stage dementia. Omega (Westport). (2022), 00302228221147961. doi: 10.1177/00302228221147961. [Epub ahead of print].

38. Halevi Hochwald I, Arieli D, Radomyslsky Z, Danon Y, Nissanholtz-Gannot R. Emotion work and feeling rules: Coping strategies of family caregivers of people with end-stage dementia in Israel—A qualitative study. Dementia (London). (2022) 21:1154–72. doi: 10.1177/14713012211069732

39. Weinhardt M, Lärm A, Boos B, Tesch-Römer C. Attitudes towards people with dementia in Germany. dza-aktuell: Deutscher Alterssurvey 03/2022. Berlin: Deutsches Zentrum für Altersfragen (2022). Available online at: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-83408-7 (Accessed May 5, 2024).

40. Raz AE, Schicktanz S. Comparative Empirical Bioethics: Dilemmas of Genetic Testing and Euthanasia in Israel and Germany. Cham: Springer (2016).

41. Laceulle H. Aging and the ethics of authenticity. Gerontologist. (2018) 58:970–8. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx037

42. Green O, Ayalon L. Whom do migrant home care workers contact in the case of work-related abuse? An exploratory study of help-seeking behaviors. J Interpers Violence. (2016) 31:3236–57. doi: 10.1177/0886260515584347

43. Mehta SR. Contesting victim narratives: Indian women domestic workers in Oman. Migr Dev. (2017) 6:395–411. doi: 10.1080/21632324.2017.1303065

Keywords: vulnerability, dementia care, migrant caregivers, experts, triadic care arrangement

Citation: Ulitsa N, Nebowsky AE, Ayalon L, Schweda M and von Kutzleben M (2025) Vulnerabilities in migrant live-in care arrangements for people with dementia: a comparative analysis of experts’ insights from Germany and Israel. Front. Psychiatry 16:1485270. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1485270

Received: 23 August 2024; Accepted: 03 February 2025;

Published: 28 February 2025.

Edited by:

Yuka Kotozaki, Iwate Medical University, JapanReviewed by:

Olayinka Onayemi, Bowen University, NigeriaJudith Phillips, University of Stirling, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Ulitsa, Nebowsky, Ayalon, Schweda and von Kutzleben. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Natalie Ulitsa, bmF0YS11bEBob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Natalie Ulitsa

Natalie Ulitsa Anna Eva Nebowsky

Anna Eva Nebowsky Liat Ayalon

Liat Ayalon Mark Schweda

Mark Schweda Milena von Kutzleben

Milena von Kutzleben