- 1Institute for Global Health and Development, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 2College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences, University of SIerra Leone, Freetown, Sierra Leone

Background: In Sierra Leone, women of reproductive age represent a significant portion of the population and face heightened mental health challenges due to the lasting effects of civil war, the Ebola epidemic, and the COVID-19 pandemic. This study aimed to culturally adapt the Friendship Bench Intervention (FBI) for perinatal psychological distress in Sierra Leone.

Method: We utilized the ADAPT-ITT framework and Bernal’s Ecological Validity Model (EVM) for culturally adapting the FBI’s process and content. The adaptation stages included a formative study to assess perinatal women’s mental health needs. We screened the FBI for modifications based on the data from the formative study and EVM. The initial FBI manual was presented to mother-mother support groups (MMSGs, n=5) and primary health workers (n=3) for feedback (version 1.0). A theatre test with perinatal women (n=10) was conducted led by MMSGs, yielding further feedback (version 2.0). The revised manual was then reviewed by topical experts (n=2), whose insights were incorporated (version 3.0).

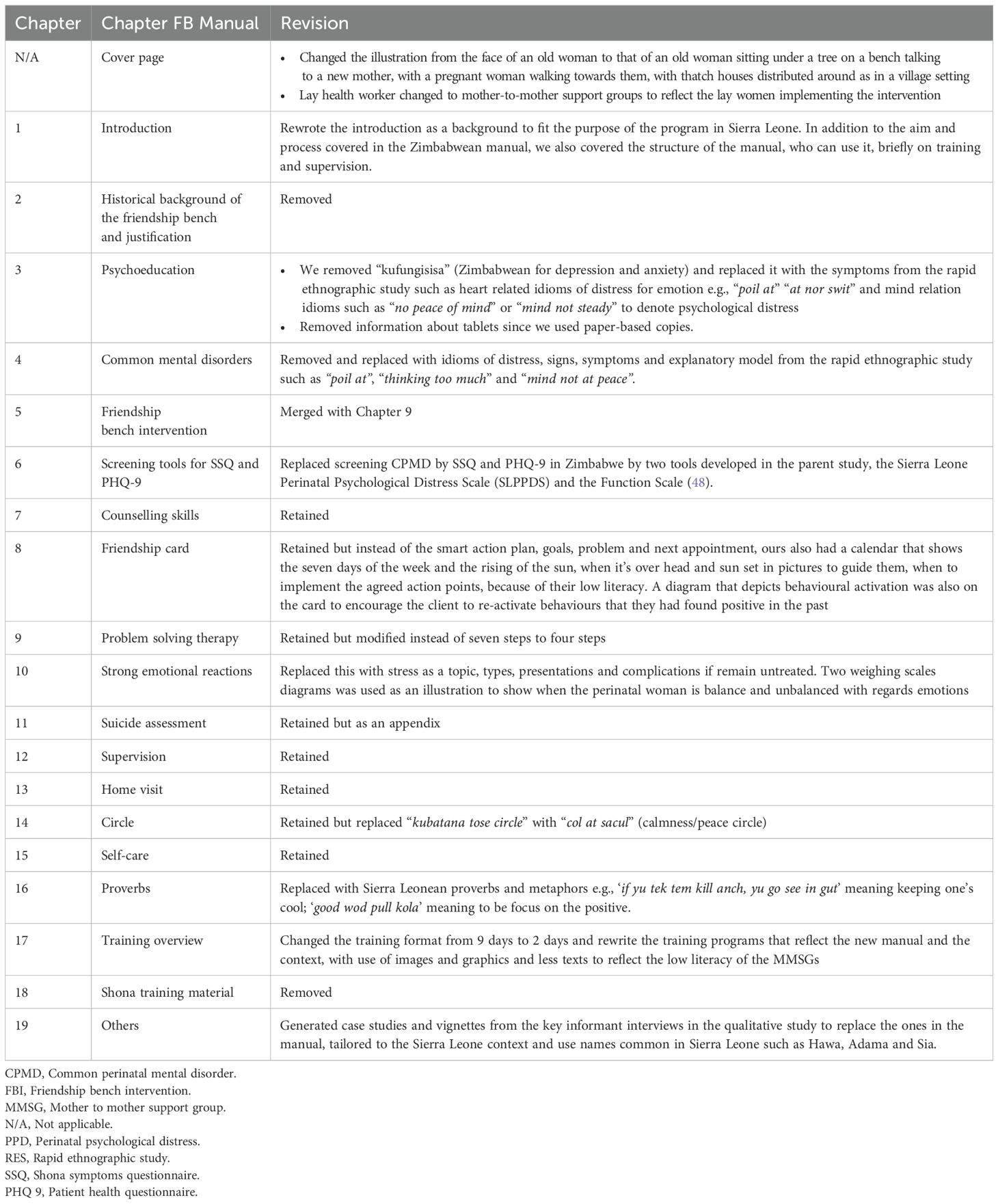

Results: The Friendship Bench manual for Sierra Leone has been revised to better meet the cultural needs of perinatal women. The cover now illustrates an elderly woman conversing with a new mother, emphasizing community support. Culturally relevant idioms, such as “poil at” and “mind not steady,” replace previous terms, and new screening tools, the Sierra Leone Perinatal Psychological Distress Scale (SLPPDS) and the Function Scale, have been introduced. The problem-solving therapy was simplified from seven to four steps, and training duration was reduced from nine days to two, using visual aids to enhance comprehension for those with low literacy levels.

Conclusion: Through this systematic approach, we successfully culturally adapted the FBI for treating perinatal psychological distress in Sierra Leone. The next step is to evaluate it feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness in perinatal care settings.

Introduction

The perinatal period if often associated with significant physiological, social, and psychological changes in women, often resulting in common perinatal mental disorders (CPMDs), with depression and anxiety being the most common (1). Global estimates indicate that the prevalence of CPMDs varies between 13% and 30%, with higher rates observed in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs; 2). In a recent study conducted in Kono district, in Eastern Sierra Leone, the prevalence of postnatal depression was 58.3% (Bah et al., in preparation). Despite the high prevalence of postnatal depression and the associated social and economic challenges among perinatal women due to the legacy of eleven years of civil war, the worst Ebola epidemic in human history, and the COVID-19 pandemic, evidence-based mental health interventions remain limited (3). In Sierra Leone, women of childbearing age (14-49) constitute about a quarter of the population (4). Some are often exposed to high rates of sex and gender-based violence, inter-partner violence, gender inequality, and lack of educational opportunities compared to men (5, 6), which is often associated with elevated rates of psychological distress (7). Furthermore, in Sierra Leone, women are disproportionately exposed to food insecurity, multi-dimensional poverty, and limited access to healthcare (7), which is compounded during the perinatal period. Women in rural areas reside in resource-limited settings plagued by high levels of gender inequality and patriarchy (5), exacerbating the negative impacts of previous trauma and loss. This situation contributes to increased rates of suicidal ideation, depression, hopelessness, stressful behaviours, low self-esteem, and increased maternal mortality among women (1, 6).

Enhancing maternal health is a fundamental priority of the Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s, and Adolescents’ Health. However, much of the emphasis remains on physical health. While addressing physical health is essential—given that complications such as bleeding, infections, and eclampsia are leading causes of maternal mortality—neglecting mental health needs leaves mothers neglected (2). Sierra Leone has developed a comprehensive Reproductive Maternal Neonatal Child and Adolescent (RMNCH) policy (8). However, the absence of mental health considerations in the RMNCH program is concerning, especially given that perinatal mental health is in the National Mental Health Policy and Strategic Plan, first published in 2010 and updated in 2019 (9). Research indicates that neglecting perinatal common mental disorders can impact negatively on pregnancy outcomes, as seen in intra-uterine growth retardation, preterm delivery, and delayed social, physical, emotional and neuro-cognitive development (10). Studies have also established an association between maternal depression and decreased or lack of breastfeeding, infant malnutrition, increased absenteeism for immunization, and negative impact on physical and mental health throughout the life-course — with an intergenerational impact (11). Consequently, it is essential to increase government investments in evidence-based mental health and psychosocial support interventions, given that the evidence showed that the return on investment is 1:4 (12).

In recent years, the World Health Organization (WHO) has highlighted the critical need for scalable task-sharing psychological interventions in low-resource settings due to the significant gap between the demand for and availability of evidence-based mental health services in these settings (13). Low-intensity, manualized, task-sharing interventions focus on training non-specialist providers, such as community and lay health workers to deliver mental health care. Designing, implementing, monitoring and evaluating (DIME) new evidence-informed interventions can be resource-intensive; therefore, culturally adapting existing interventions may expedite their implementation especially in resource limited settings (14). Cultural adaptation is the systematic modification of the design and/or delivery of an evidence-based intervention to enhance its relevance and effectiveness in a specific setting different from where it was originally developed (15). Cultural beliefs significantly shape individuals’ understanding of mental health, often leading to stigma, decreased help-seeking, and often include family involvement in decision-making within collectivist societies (16). Additionally, therapeutic approaches may conflict with religious beliefs that challenge notions of personal agency. This adaptation process is essential for ensuring that the intervention is compatible with their values and beliefs, while also integrating their needs, priorities, and social context (17, 18). Meta-analyses have shown that culturally adapted interventions are generally more effective than non-adapted ones (19, 20). Additionally, cultural adaptation is an ethical responsibility, reducing the risk of imposing treatments that conflict with individual’s cultural norms (21). However, such modifications are frequently inadequately documented, which can hinder their replication and the systematic evaluation of their effectiveness (17). Therefore, employing a clear framework for adapting evidence-based interventions for new cultural contexts and populations—such as perinatal women—can enhance engagement, improve access to these services, and support robust methodological evaluations of their clinical effectiveness.

In Sierra Leone, previous initiatives have aimed to meet the mental health needs of conflict-affected youths. Many of these interventions adopt a transdiagnostic approach to address the co-occurrence of symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress (PTS), which are prevalent among children associated with armed forces and armed groups (CAAFAG) (22). For example, the Youth Readiness Intervention (YRI) has been effectively implemented for CAAFAG, resulting in significant reductions in post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTS), anxiety, depression, somatic complaints, and functional impairments while also improving quality of life (23). In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), the YRI showed that the intervention improved prosocial behaviours, emotion regulation, decreased school dropouts, improved classroom behaviour and social support (24). Despite the positive outcomes associated with the YRI, there remains a pressing need for interventions specifically tailored to the unique needs of pregnant women and new mothers in Sierra Leone.

The current study

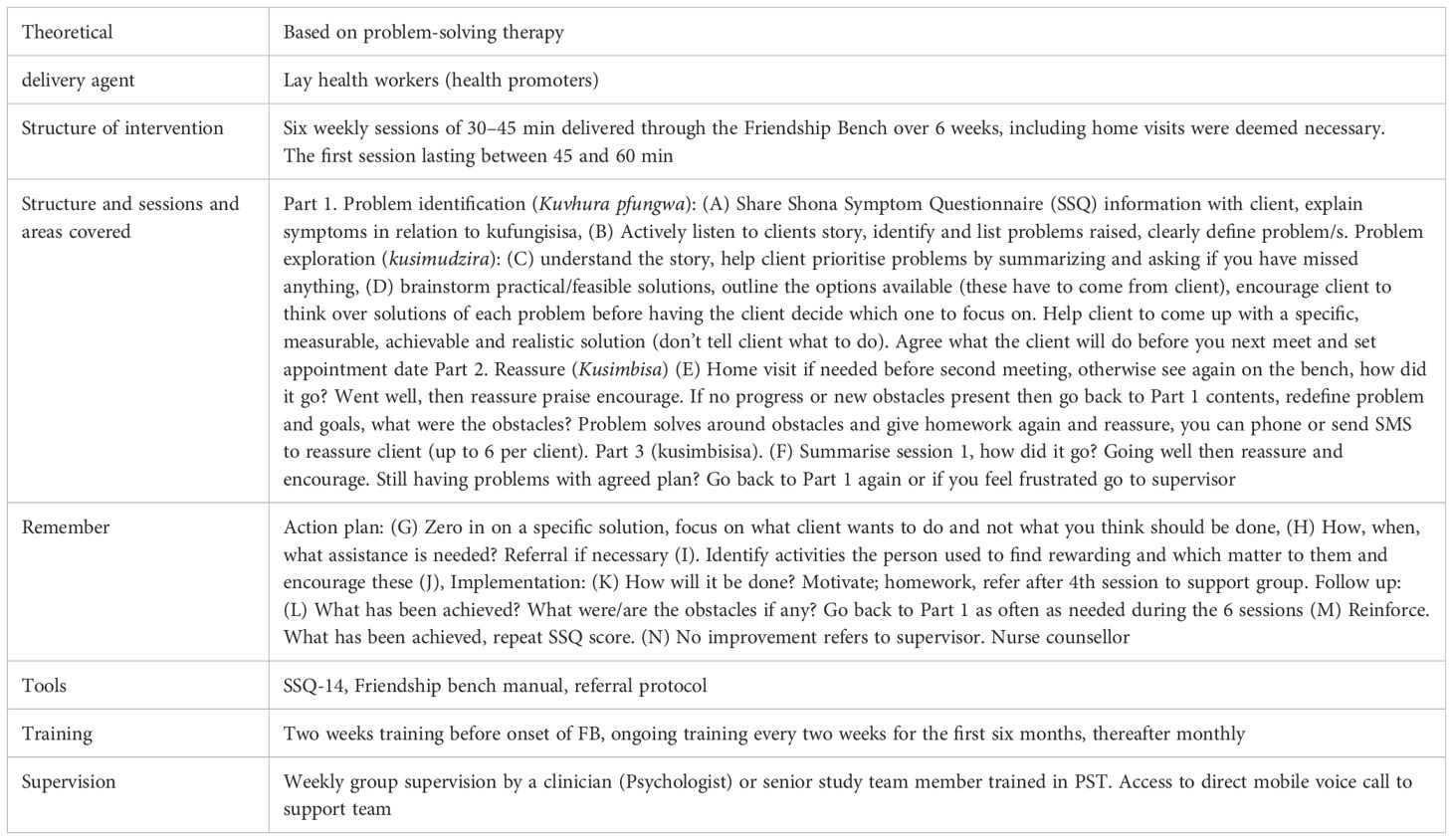

This research aimed to identify and culturally adapt a scalable, evidence-based mental health intervention to address perinatal psychological distress in Sierra Leone. We chose the FBI (see Table 1) for this study. The Friendship Bench intervention originally developed in Zimbabwe, is a community-based mental health initiative designed to provide accessible psychological support through trained lay health workers. It employs a simple, culturally appropriate model where individuals receive counseling on a bench in their community, facilitating open dialogue about mental health issues using a problem-solving approach (25). This program has shown significant effectiveness in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety among participants, demonstrating the potential as a scalable, low-cost, mental health solution (26). By integrating mental health care into community settings, the FBI serves as a proof of concept for similar interventions globally.

The cultural adaptation process followed a structured approach based on the ADAPT-ITT framework (18). This framework has been widely applied for cultural adaptations in health and mental health research across various LMICs and among marginalized groups in Vietnam (27), Columbia (28), Sierra Leone (29), and Ethiopia (30). Furthermore, we combined it with the Ecological Validity Model (EVM) to inform the content modifications of the FBI manual (31), which systematizes adaptations according to eight key parameters: language, goal, context, concept, content, methodology, person, and metaphor. Combining ADAPT ITT and EVM (30) aligns with the call for the use of multiple adaptation models (32), which is considered a strength in the cultural adaptation of evidence-based interventions developed in the Global North for culturally diverse populations in resource-limited settings in the Global South.

Method

Study design

This qualitative research is nested in an exploratory, sequential mixed-method study conducted between January 2020 and July 2021. This study was conducted in Krio, the primary lingua franca of Sierra Leone, which serves as the common language for communication among various ethnic groups, despite English being the official language (33).

Study settings

This research was conducted at two communities, Campbell Town and Lumpa, randomly selected among a list of communities in Waterloo, part of the Freetown metropolitan area. Waterloo, a peri-urban area, is located in the Western Area Rural district, which is one of 16 districts in Sierra Leone. It is situated 20 miles from the capital city of Freetown. It is the second largest city in the Western Area after Freetown. It has a population of 55000 (4). Waterloo is one of the most ethnically diverse, peri-urban cities, and it lies on the main highway linking the capital city and rest of the country.

We worked with nurses, midwives, community health officers (CHOs), community members, pregnant women, new mothers, and MMGs in these communities for the cultural adaptation of the intervention. The primary language used in these communities is Krio, and their main economic activity is agriculture. Waterloo has one primary hospital as well as eight health centres that serve approximately 5,000 households each. Additionally, each health centre is connected to 3-5 health posts, which are basic healthcare facilities that conduct health promotion and illness prevention activities. CHOs head each community health centre (CHC), and their responsibilities include maintaining a list of perinatal women in their catchment area. Following the launch of the National Mental Health Policy and Strategy of Sierra Leone (9), some of the CHOs at these facilities were trained using the WHO mhGAP intervention guide, and are supported in providing first-line mental healthcare.

Research team

The cultural adaptation was done by the study lead (AJB) and four research assistants, all University graduates who were part of the formative study, and understood the purpose of the intervention. A one-day training was conducted for the research assistants on the cultural adaptation of evidence-based interventions. The training was focused on ethics and techniques in cultural adaptation using the qualitative data we collected. All research assistants were involved in the project from the inception phase (34). One of the research assistants was a nurse, and previously worked as the mental health and psychosocial support lead at the Sierra Leone National Ambulance Services. We had two graphic designers in the education department of the Ministry of Health and Sanitation. A supervisory team at Queen Margaret University (AA & RH) supported us throughout the process.

Cultural adaptation of the friendship bench intervention

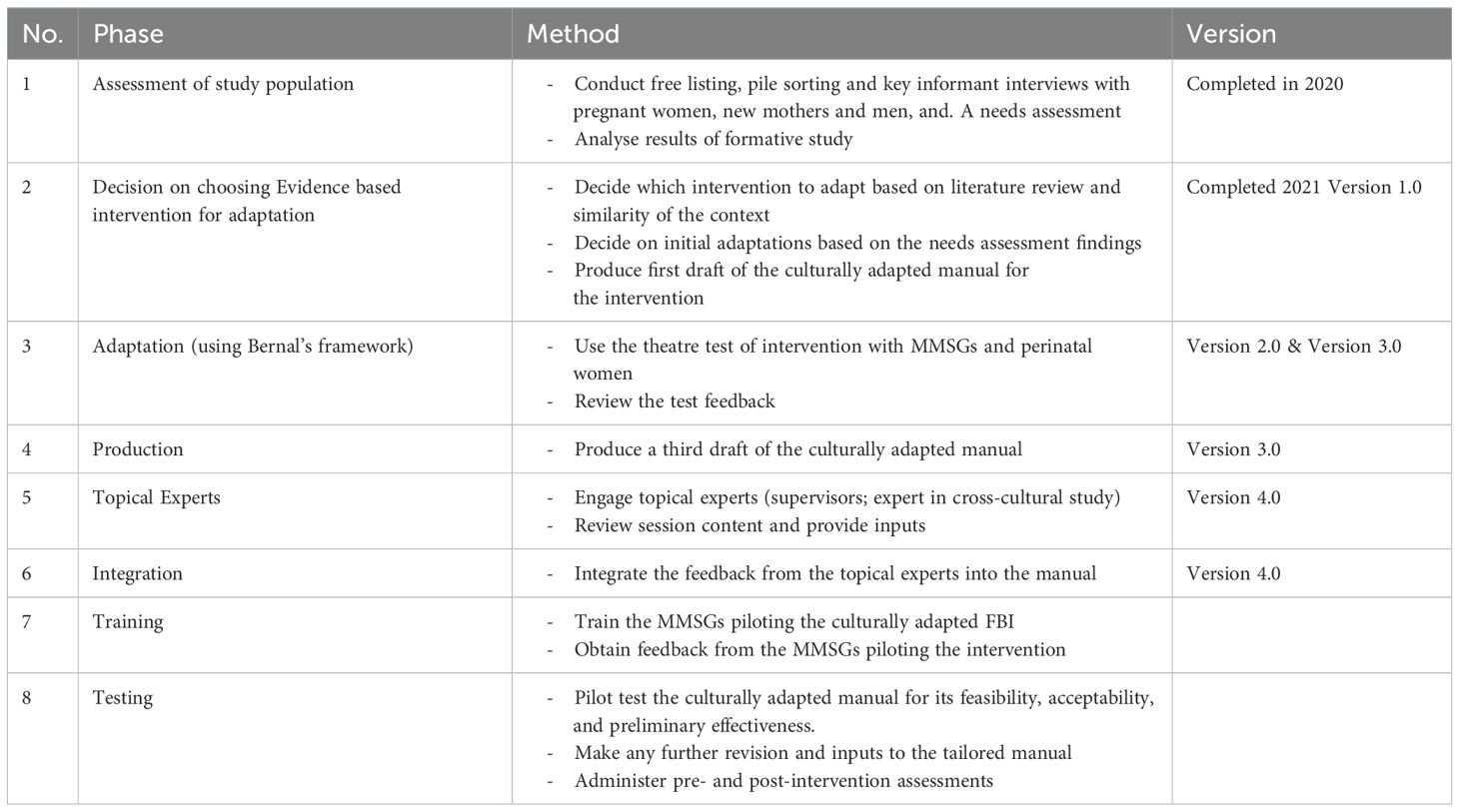

There are eight sequential Phases in the ADAPT-ITT model (see Table 2): Phase 1, the assessment, was the formative study that assessed the mental health needs of pregnant women and new mothers using a rapid ethnographic approach (34). Phase 2, the decision was reached by reviewing the qualitative study and literature data. This paper describes the third to the sixth phases of the model—phase 3 (adaptation), phase 4 (production), phase 5 (topical experts), and phase 6 (integration). Phase 7 (training) and phase 8 (testing) will be published in a future study exploring the intervention’s feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness.

Phase 1: assessment

This was a formative study, rapid ethnographic research nested in a larger study, which was a mixed-method, exploratory, sequential design. This Phase involved assessing the mental health needs of pregnant women and new mothers, including how they experience and express psychological distress, their coping mechanisms and help-seeking behaviour. We recruited pregnant women, new mothers, men, and older women at the community level in four districts (Bo, Western Area, Bombali and Kono) that is representative of the four geopolitical regions of the country. We conducted free listing (n=96), pile sorting (n=8) and key informant interviews (n=16), exploring the problems experienced by perinatal women related to thoughts, feelings and behaviours. This qualitative formative research highlighted a significant link between the depressive symptoms experienced by perinatal women and various stressors, including poverty, unemployment, insufficient partner support, abuse, bereavement, and unplanned or unwanted pregnancies (34). We analyzed the data using thematic content analysis, supported by frequency analysis and multidimensional scaling.

The analysis identified twenty signs of distress, and the concept of the self for perinatal women encompassed the heart, mind, and body, reflecting their emotional states such as sadness, stress, loneliness, and anger. They articulated various culturally specific idioms of distress, such as “stres” (stress) and “poil at” (depression), which are linked to broader issues like poverty, marital conflict, and gender inequality. These idioms function as overlapping indicators of distress, which can intensify over time. Commonly cited sources of psychological distress included interpersonal conflicts, economic hardship, and gender-related challenges (35). Notably, women did not perceive their problems as biomedical in nature, which is reflected in their coping strategies and help-seeking behaviours. Their coping mechanisms involved conversations with family, friends, community members, and engaging in risky behaviour such as drinking alcohol (34). However, many participants felt their strategies were ineffective, as unresolved issues persisted, contributing to ongoing stress. Help-seeking behaviours included reaching out to social networks, religious leaders, and occasionally traditional healers, while mother-to-mother support groups (MMSGs) were frequently mentioned as a local source of emotional support. The MMSGs in Sierra Leone are lay women, volunteers, working with the directorate of nutrition, supported by UNICEF. They empower perinatal women through peer support and education on health, nutrition, and hygiene to improve maternal and child health outcomes in Sierra Leone.

Phase 2: decision

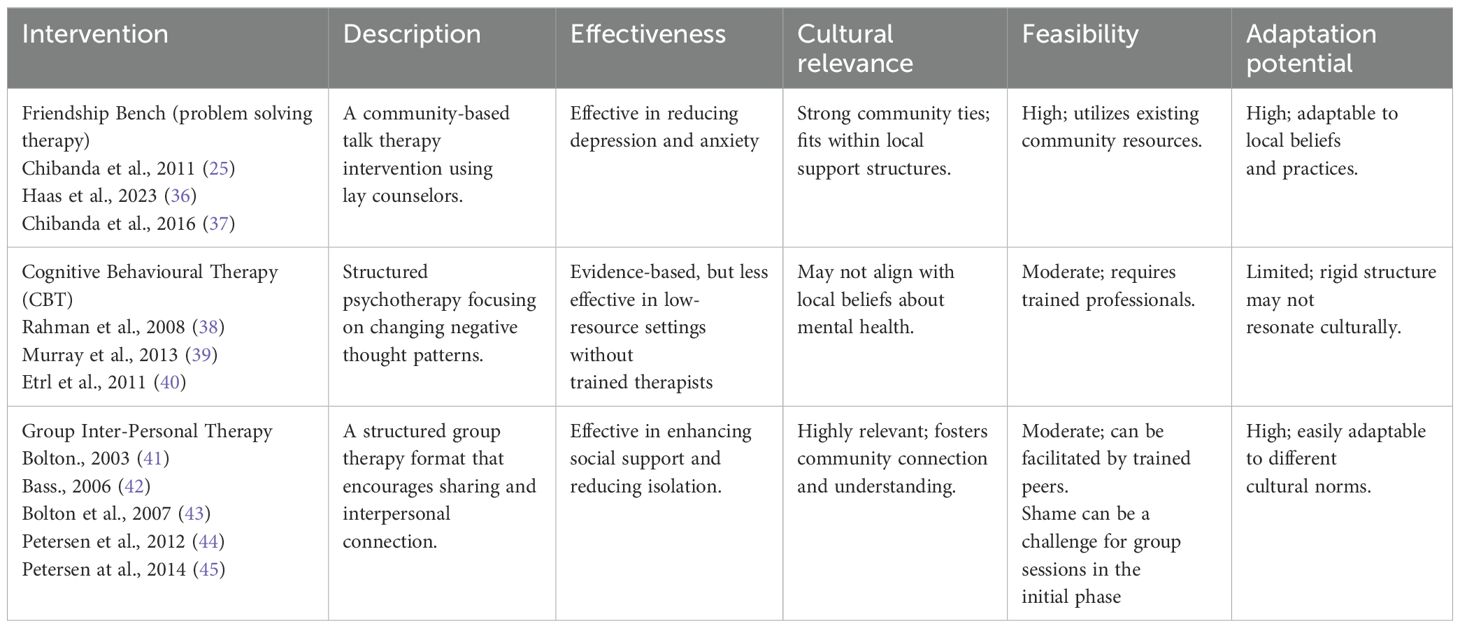

This Phase entailed reviewing the existing evidence-based interventions in the literature and deciding which one resonates with the findings from the formative study. To evaluate various interventions addressing perinatal psychological distress, we conducted a systematic review. The review involved a comprehensive search of the literature and existing programs, focusing on their effectiveness, cultural relevance, feasibility, and potential for adaptation (see Table 3). The review showed that culturally adapted interventions conducted by lay health workers in sub-Saharan African countries fell into three categories: IPT (41–45), FBI-PST (25, 36, 37, 46) and CBT (23, 24, 38–40). We selected the FBI due to its strong cultural fit within the collectivist context of Sierra Leone, where community relationships are vital, and the attributes and risk profiles of the perinatal women match with problem-solving theory and design approaches to interventions.

The formative study conducted in Sierra Leone presents compelling reasons for choosing the Friendship Bench intervention over Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) to address the mental health needs of perinatal women. Firstly, the study underscores the importance of cultural context, revealing that perinatal women express psychological distress through culturally specific idioms, which the Friendship Bench is well-equipped to address, unlike CBT and IPT that may lack cultural resonance (34). Additionally, the findings highlight the significance of community engagement, as participants favored seeking support from family and mother-to-mother support groups (MMSGs), which the Friendship Bench effectively taps into by employing trained lay counselors from the community (35).

Furthermore, the study indicates that participants view their psychological issues as linked to socio-economic stressors rather than biomedical concerns, aligning more closely with the Friendship Bench’s focus on social support and problem-solving (34). The intervention also leverages existing support structures like mother-to-mother support groups, enhancing its effectiveness without requiring extensive infrastructure or training, which is often a barrier for CBT and IPT in resource-limited settings. Moreover, the Friendship Bench emphasizes practical coping strategies and peer support, addressing the immediate needs expressed by participants for more effective coping mechanisms (34). Finally, while CBT and IPT are established therapies, the Friendship Bench has demonstrated effectiveness in similar low-resource contexts, suggesting it can lead to significant improvements in mental health outcomes among populations facing socio-economic challenges (25, 36, 37, see Table 4).

Culturally adapting the Friendship Bench intervention from Zimbabwe to Sierra Leone requires consideration of several key differences. In Zimbabwe, due to the high literacy level, community engagement and awareness about mental health are more pronounced, potentially reducing stigma compared to Sierra Leone, where such awareness may be limited. Language diversity in Sierra Leone includes Krio and various local dialects, necessitating it translation and culturally relevant metaphors. The context of Sierra Leone involves distinct social norms and communal values that may differ from Zimbabwean practices. While Zimbabwe employs trained community health workers, Sierra Leone can leverage on mother-to-mother support groups (MMSGs) for delivery, enhancing relatability and trust.

Phase 3: adaptation of the content using the EVM

The first author (AJB) and the research assistants read the FBI intervention manual to identify components of the intervention that could be subjected to cultural adaptation (adaptive hypothesis) across the eight EVM dimensions. Using the data from the formative study and the EVM, the original FBI manual was modified accordingly by the research team (version 1.0).

Step 1. Presentation of the FBI to the MMSGs, healthcare workers and perinatal women

The research lead (AJB) and the nurse research assistant with a background in mental health psychosocial support presented the modified Zimbabwean FBI manual (version 1.0) as a training course to the MMSGs (n=5), and the primary healthcare workers, nurse (n=1), midwife (n=1), and a CHO (n=1), from the CHC for a two-day session. The other two research assistants served as note-takers. Following the presentation, we conducted a full-day adaptation workshop with the attendees looking at potential challenges and opportunities. MMSGs participated in and led several theatre testing simulations of a lay-health worker-delivered model. They role-played, and after each role-play, we discussed the modified delivery method and adaptations needed (18). MMSGs shared their concerns and thoughts about the barriers and facilitators that may impact the delivery model and potential implementation strategies to address the obstacles. We discussed the feedback from this workshop using the framework from the EVM, and the output from this workshop was the second version of the intervention manual (version 2.0).

Step 2. Theatre testing

Theatre testing is a systematic approach for culturally adapting an intervention that forms part of the ADAPT-ITT approach (18). MMSGs presented version 2.0 of the adapted intervention with separate sessions for pregnant women (n=5) and new mothers (n=5) using theatre testing in the study site area. Clinical vignettes developed from the qualitative study were used for the demonstration. A MMSG (taking the therapist’s role), a pregnant woman, and later a new mother (playing the perinatal woman’s role) role-played the intervention sessions. Role-play activities simulated what the MMSGs could experience when delivering the culturally adapted intervention and what the perinatal women might experience when receiving it.

At the end of each demonstrated session, two facilitators from the research team led separate group discussions using the EVM (47) to improve the comprehension, relevance, and acceptability of the content. The note-takers captured the discussions and feedback. AJB and one of the research assistants analyzed these notes using thematic content analysis, using the EVM domains (version 3.0).

Phase 4: production

In this Phase, the research team combined and analyzed all the data collected during the adaptation phases including the theatre testing, to produce the version 3.0 of the culturally adapted FBI.

Phase 5 and 6: topical expert and integration

Version 3.0 of the manual was then reviewed by the PhD supervisory team at the Queen Margaret University (AA & RH) serving in the capacity of topical experts. Their suggestions and recommendations were integrated, leading to version 4.0 of the intervention manual. The two experts had significant expertise in cross-cultural mental health research, with experience working in low-resource settings, including Sierra Leone (7, 35). Following their inputs, the research team convened to evaluate the suggestions and determine the modifications to be made based on the cultural context. The experts’ feedback emphasized the cultural relevance, format, and duration of the intervention while ensuring the retention of the evidence-based component.

Ethical approval

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board at Queen Margaret University and the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee.

Results

In this section, we present the findings from our study on the cultural adaptation of the FBI using the ADAPT ITT framework and the EVM. The ADAPT ITT framework comprehensively outlines the process for adapting the culturally modified FBI manual, detailing how each step maintains fidelity to the original intervention while addressing the unique needs of perinatal women. Following this, the EVM provides insights into the cultural adaptation of the manual, highlighting the essential adjustments made to align the content, context and delivery of the culturally adapted FBI with the cultural context of the intended perinatal women.

ADAPT ITT

Phase 3: adaptation – the EVM (used as a framework for the content adaptation)

This section synthesizes findings across eight domains of the ecological validity model, highlighting key themes and participant quotes that illustrate the effectiveness of the intervention designed for perinatal mental health in Sierra Leone.

The ecological validity model

The EVM outlines eight domains essential for culturally adapting evidence-based interventions: language, goals, methods, metaphor, content, context, concepts, and persons. Each domain is documented in a matrix format to detail the adaptation process (Additional File IV in Supplementary Material). For instance, training materials for MMSGs were initially developed in English and translated into Krio, ensuring clarity and cultural relevance. Language specificity was emphasized, using local idioms to enhance understanding and reduce stigma. Frequently used local idioms of psychological distress from the formative study: “vex, heng at, stres, tink too much, cry cry, dikoraj, and fostrate” were identified. All technical terms were translated into local expressions, and we replaced the term depression for example with culturally congruent terms such as “poil at”,” at nor swit”, and anxiety, with ‘‘stres” or wori”, and we tried to avoid psychiatric labels. This was to improve clarity during the consultation, minimize stigma and increase perinatal women’s engagement with services. Participants noted the significance of this adaptation, stating, “When I read in Krio, I understand better”. Locally recognized idioms for psychological distress, such as “poil at” and “tink too much”, were integrated to provide a broader understanding of symptoms beyond conventional classifications. Participants highlighted the importance of using relatable terms: “poil at” feels less stigmatizing compared to depression, making it easier to talk about psychological distress.

The model also highlights the importance of client-therapist pairing, focusing on shared cultural backgrounds and community acquaintance. MMSGs, who are ethnically and gender-matched to the communities they serve, foster trust and credibility. One participant remarked, “because she understands us, I can speak freely”. Their training in the FBI allows them to build empathic, non-judgmental relationships, enhancing client engagement. MMSGs emphasize confidentiality, with one stating, “We always remind them that what is shared stays between us”. The content adaptation involved integrating culturally relevant case studies and addressing problems during community interactions. MMSGs were trained to respect local practices, including traditional remedies. The intervention addresses common stressors and promotes social connections. Participants emphasized the importance of integrating local remedies: “Mixing traditional practices with new ideas helps us feel supported”. The focus on behavioural activation encourages the rediscovery of enjoyable activities, such as braiding and visiting friends, reinforcing a holistic view of well-being.

The EVM stresses that intervention concepts must align with cultural norms and be understood by clients, promoting positive inter-partner relationships and reducing violence. The PST intervention adopts a bio-psycho-social-spiritual framework, highlighting the interconnectedness of physical symptoms, thoughts, and emotions. One participant noted, “Understanding that my feelings can affect my body helps me seek help”.

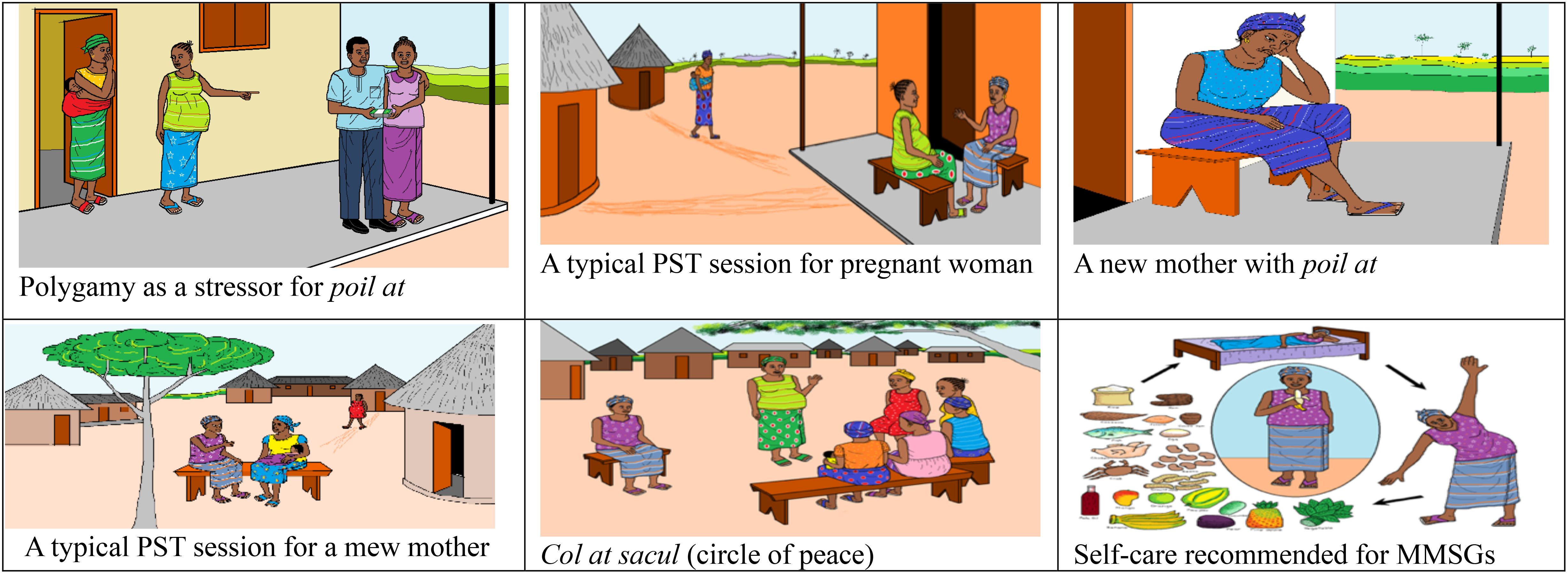

Methods were tailored to individual sessions due to clients’ preferences for privacy, ensuring flexibility to accommodate personal commitments. The intervention minimizes written materials and uses pictures, graphics, and drawings (Additional Files I–III in Supplementary Material) This was intended to make the locally developed and validated screening tool for perinatal psychological distress and the function scale (16), as well as the assignment and activity tracker for perinatal women more user-friendly for women with low literacy and numeracy.. One participant noted, “The pictures help me see what I need to do”. The structured problem-solving approach, reinforced by the manualized materials and consistent supervision, ensures clarity and understanding throughout the therapeutic process.

Contextual factors—such as social support, stigma, and transportation—were considered in designing the intervention. Flexibility in scheduling therapy sessions around significant local events enhances acceptability. A participant remarked, “Having sessions at times that work for us makes attending easier. “The intervention’s adaptability to community dynamics, such as family involvement and culturally appropriate delivery methods, underscores its relevance. Participants emphasized the importance of involving male partners in discussions, stating,” When my husband knows, he can support me better.” Metaphors which are sayings that are familiar to the community were integrated, such as “Ol kondo de dreg in belleh na gron, yu kno kno d wan wae in belleh de at” meaning ‘some challenges in life might be invisible’. Participants appreciated this approach, with one saying, “Stories from our culture make the messages clearer”. The use of expressions like” “fambul tik kin ben, but enoba brok”, meaning ‘families endure challenges over time but consistently recover’, this resonates deeply with the community members. The goals of treatment were designed to reflect and reinforce positive cultural values, focusing on the client’s perspective and promoting optimal symptom reduction and social functioning. The EVM emphasizes a comprehensive, culturally sensitive framework for effective intervention delivery. Participants stressed the importance of clarifying treatment expectations, with one stating, “We need to know what to expect; it helps reduce our fears”. Education about stigma and misconceptions surrounding mental health is crucial for engagement.

Phase 4: production

After imputing the contributions from the MMSGs, primary healthcare workers, and the perinatal women, we produced a fifteen-chapter manual intended to guide the piloting of the culturally adapted intervention. To effectively manage the delivery of the intervention by MMSGs with low literacy levels, we proposed several strategies: utilizing visual aids such as pictures and diagrams to convey key concepts (see Figure 1 for a model illustration), emphasizing oral communication and storytelling as primary methods for sharing information. Training lay MMSGs to facilitate discussions and document key insights, and implementing simple feedback mechanisms to gauge understanding without requiring written responses, thereby making the intervention more accessible and effective. Additional File 1 and 2 provide screening tools (48) for psychological distress and functional capacity, translated in Krio and presented in graphic form, while Additional File 3 depicts the culturally adapted FBI, including the behavioral activation components in graphic design, and a weekly calendar using the sun as a reference frame for the time of the day, to remind perinatal women of specific activities to incorporate into their weekly plans following the PST sessions.

Phase 5 and 6: topical expert and integration

The topical experts recommended adjustments to ensure the vignettes and metaphors reflected the formative, qualitative data from Sierra Leone, while maintaining the core structure of the intervention. The committee emphasized preserving the fidelity of in-person counselling procedures and maintaining the PST framework in each session.

The integration phase involved the research team meeting to iteratively revise the manual based on feedback from the topical experts. This collaborative effort led to the development of version 4.0, the final version. This version intends to train MMSGs in a randomized controlled, pilot study to test the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary effectiveness of the culturally adapted intervention (see Table 5).

Phase 7 and 8: training and testing

These phases focused on training and testing the culturally adapted intervention. We conducted a two-day training for the MMSGs that piloted the culturally adapted intervention at intervention and control sites. Subsequently, a randomized controlled pilot study was conducted to assess the intervention’s feasibility, acceptability and preliminary effectiveness among newly screened pregnant women and new mothers, published in a subsequent manuscript. The findings from this mixed-method pilot study will inform the final version of the culturally adapted FBI manual that would be used for a well-powered randomized controlled Trial.

Discussion

This study systematically adapted an evidence-based mental health intervention originally designed for common mental disorders among adults in Zimbabwe to address the needs of perinatal women in Sierra Leone (21, 26). Using community-based participatory research methods, guided by the ADAPT-ITT framework and Bernal’s EVM (49), we collaborated with community members, primary healthcare workers, and perinatal women to achieve the cultural adaptation. This approach ensured that the life-world of perinatal women were integral to the cultural adaptation, enabling the intervention to effectively address their specific needs and priorities. A key feature of the adapted intervention is its lay health worker delivery model, where trained MMSGs, who do not have formal mental health training, will be implementing the intervention. Research has shown that lay health worker delivery models can be effective for mental health interventions in low-resource settings (25, 50, 51).

Our findings underscore the importance of culturally sensitive adaptations of evidence-based interventions, which resonate with the specific needs of the target population and enhance engagement and effectiveness (52). Previous adaptations of the FBI have demonstrated it feasibility and effectiveness of culturally tailored interventions in various settings (27, 37, 46, 53). For instance, the FBI was successfully adapted for use in Zimbabwe, where community health workers delivered PST to address common mental disorders, significantly improving mental health outcomes (36, 54, 55). This study exemplifies how community involvement and local context can enhance the efficacy of mental health interventions.

Previous studies have shown that culturally adapted interventions conducted by lay health workers in sub-Saharan African countries significantly enhanced the effectiveness of health programs. Noteworthy examples include the IPT in South Africa (44, 45), IPT in Uganda (40–43), PST in Zimbabwe (25, 36), and CBT in Zambia (39). Although some of these studies employed randomized control trial methodologies (25, 40–43), others utilized quasi-experimental designs (56), non-randomized approaches (36, 44), cohort prospective studies (39), and randomized control pilot studies (45). It is important to note that the application of a cultural adaptation framework was largely absent in most of these studies, with cultural adaptation often encompassing only a limited scope. The elements of cultural adaptation included the reduction of training and intervention delivery times, the use of local languages, the integration of cultural and religious components, and the involvement of local lay health workers (57). All of these adaptations have demonstrated effectiveness and acceptability.

Our adaptation process, involving community feedback from the MMSGs and perinatal women, ensured that the intervention was grounded in scientific evidence while also reflecting the lived experiences of the pregnant women and new mothers (57). This participatory approach is consistent with the principles of community-based participatory research, emphasizing collaboration and co-learning between researchers and community members (58). The cultural adaptation highlighted the interplay between societal norms, traditional beliefs, and the psychological distress experienced by perinatal women, which aligns with findings from other contexts where culturally tailored interventions have been shown to increase engagement with services, reduce stigma, and improved the outcomes of the target population (59).

Limitations and future directions

While our adaptation process was robust, it is essential to acknowledge some limitations. Firstly, relying on the MMSGs for perinatal mental health support can lead to inconsistencies in the quality of care provided. While these community members can offer valuable assistance, they often lack the professional training and expertise necessary for addressing complex mental health issues. This variability may affect the effectiveness of the intervention, particularly for more severe cases that require specialized care from trained professionals. Furthermore, the long-term sustainability of such interventions is a significant concern. Continuous funding, training, and supervision of the MMSGs are crucial to maintain the quality and impact of the program.

Additionally, evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention poses difficulties, particularly in capturing long-term outcomes and ensuring that the goals are met across diverse settings. Addressing these challenges is essential to enhance the overall impact and success of the culturally adapted FBI intervention for perinatal psychological distress in Sierra Leone.

Implications for maternal mental health

The culturally adapted FBI for perinatal mental disorders in Sierra Leone offers significant benefits by aligning with local cultural beliefs, enhancing its relevance and acceptance among perinatal women. By utilizing community resources and the MMSGs, the intervention increases accessibility to mental health support, especially in rural or underserved areas where professional services are limited. This approach helps overcome logistical and financial barriers that perinatal women often face, ensuring they receive the support they need during a vulnerable period.

Furthermore, the intervention fosters vital social support networks, which can alleviate feelings of isolation and anxiety among perinatal women. By normalizing discussions about mental health within the community, the FBI helps reduce stigma, encouraging more women to seek help. The success of this culturally sensitive model in Sierra Leone could serve as a blueprint for similar initiatives in other regions, ultimately improving maternal and infant health outcomes and contributing to a more supportive and resilient community.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the cultural adaptation of the FBI for perinatal psychological distress in Sierra Leone represents a meaningful advancement in addressing the mental health needs of women during the perinatal period. This study provides valuable insights for developing effective mental health interventions in LMICs by using a culturally informed, community-driven approach. The successful adaptation of the FBI provides a model for future interventions. It highlights the necessity of tailoring mental health services to the unique cultural contexts of the populations they serve. The next step will be to assess the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary effectiveness of the intervention and its delivery in perinatal care settings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Queen Margaret University Edinburgh Research Ethics Committee and the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee, Ministry of Health and Sanitation. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HW: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. MS: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. RH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research programme 16/136/100. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of the research assistants, who demonstrated high levels of commitment and professionalism throughout the data collection process, which include Ajaratu Kamara, Mamadu Jalloh, Sinava B. Lamin, Simeon S. Sesay, and Malik Sulaiman Daewood. We extend our heartfelt gratitude to Ms. Aminata Shamit Koroma and her team, Directorate of Nutrition at the MoHS, for her invaluable support and for assigning the MMSGs to our study. We also recognize the dedication and passion exhibited by the MMSGs in delivering the intervention.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1441936/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ADAPT ITT, Assessment Decision Adaptation Production Topical Expert Integration Training & Testing; CBT, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; CHC, Community Health Centre; CHOs, Community health Officers; EIP, Evidence Informed Prevention; EVM, Ecological Validity Model; FBI, Friendship bench Intervention; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency virus; IPT, Interpersonal Therapy; LMIC, Low- and Middle-Income Countries; MoHS, Ministry of Health and Sanitation; mhGAP, Mental Health Gap Action Program; MMSGs, Mother-Mother Support Groups; PPD, perinatal Psychological Distress; PST, Problem Solving Therapy; UNICEF, United Nations International Children’s Fund; WHO, World Health Organization.

References

1. Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. (2012) 90:139–149H. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.091850

2. Lancet T. Perinatal depression: A neglected aspect of maternal health. Lancet. (2023) 402:667. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01786-5

3. Bah AJ, Idriss A, Wurie H, Bertone MP, Elimian K, Horn R, et al. A scoping study on mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) in Sierra Leone. (Edinburgh, UK: Queen Margaret University) (2018). doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.21691.85284.

4. Statistics Sierra Leone. Sierra leone demographic and health survey. (Freetown, Sierra Leone: Statistics Sierra Leone) (2019).

5. Duffy M, Churchill R, Kak LP, Reap M, Galea JT, O’Donnell Burrows K, et al. Strengthening perinatal mental health is a requirement to reduce maternal and newborn mortality. Lancet Regional Health - Americas. (2024) 39:100912. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2024.100912

6. McNab SE, Dryer SL, Fitzgerald L, Gomez P, Bhatti AM, Kenyi E, et al. The silent burden: A landscape analysis of common perinatal mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2022) 22:342. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-04589-z

7. Horn R, Arakelyan S, Wurie H, Ager A. Factors contributing to emotional distress in Sierra Leone: A socio-ecological analysis. Int J Ment Health Syst. (2021) 15:58. doi: 10.1186/s13033-021-00474-y

8. MoHS. National reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health policy. (Freetown, Sierra Leone: Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MoHS)) (2017).

9. Harris D, Endale T, Lind UH, Sevalie S, Bah AJ, Jalloh A, et al. Mental health in Sierra Leone. BJPsych Int. (2020) 17:14–6. doi: 10.1192/bji.2019.17

10. Slomian J, Honvo G, Emonts P, Reginster J-Y, Bruyère O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women’s Health. (2019) 15:174550651984404. doi: 10.1177/1745506519844044

11. Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M, et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet. (2014) 384:1800–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61277-0

12. WHO. Investing in treatment for depression and anxiety leads to fourfold return. WHO (2016). Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/13-04-2016-investing-in-treatment-for-depression-and-anxiety-leads-to-fourfold-return (Accessed December 27, 2024).

13. WHO. Scalable psychological interventions for people in communities affected by adversity: A new area of mental health and psychosocial work at WHO. World Health Organization (2017). Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254581/WHO-MSD-MER-17.1-eng.pdf (Accessed January 01, 2025).

14. Perera C, Salamanca-Sanabria A, Caballero-Bernal J, Feldman L, Hansen M, Bird M, et al. No implementation without cultural adaptation: A process for culturally adapting low-intensity psychological interventions in humanitarian settings. Conflict Health. (2020) 14:46. doi: 10.1186/s13031-020-00290-0

15. Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, Calloway A. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implementation Sci. (2013) 8:65. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-65

16. Ahad AA, Sanchez-Gonzalez M, Junquera P. Understanding and addressing mental health stigma across cultures for improving psychiatric care: A narrative review. Cureus. (2023) 15(5):39549. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10220277/.

17. Barrera M Jr., Castro FG. A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clin Psychology: Sci Pract. (2006) 13:311–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00043.x

18. Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The ADAPT-ITT model: A novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. JAIDS J Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. (2008) 47:S40. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1

19. Benish SG, Quintana S, Wampold BE. Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: A direct-comparison meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol. (2011) 58:279–89. doi: 10.1037/a0023626

20. Chowdhary N, Jotheeswaran AT, Nadkarni A, Hollon SD, King M, Jordans MJD, et al. The methods and outcomes of cultural adaptations of psychological treatments for depressive disorders: A systematic review. psychol Med. (2014) 44:1131–46. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001785

21. Bernal G, Adames C. Cultural adaptations: conceptual, ethical, contextual, and methodological issues for working with ethnocultural and majority-world populations. Prev Sci. (2017) 18:681–8. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0806-0

22. Betancourt TS, Borisova II, de la Soudière M, Williamson J. Sierra leone’s child soldiers: war exposures and mental health problems by gender. J Adolesc Health. (2011) 49:21–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.021

23. Newnham EA, McBain RK, Hann K, Akinsulure-Smith AM, Weisz J, Lilienthal GM, et al. The youth readiness intervention for war-affected youth. J Adolesc Health. (2015) 56:606–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.020

24. Betancourt TS, Hansen N, Farrar J, Borg RC, Callands T, Desrosiers A, et al. Youth functioning and organizational success for west african regional development (Youth FORWARD): study protocol. Psychiatr Serv. (2021) 72:563–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000009

25. Chibanda D, Weiss HA, Verhey R, Simms V, Munjoma R, Rusakaniko S, et al. Effect of a primary care–based psychological intervention on symptoms of common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2016) 316:2618–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19102

26. Chibanda D, Bowers T, Verhey R, Rusakaniko S, Abas M, Weiss HA, et al. The Friendship Bench programme: A cluster randomised controlled trial of a brief psychological intervention for common mental disorders delivered by lay health workers in Zimbabwe. Int J Ment Health Syst. (2015) 9:21. doi: 10.1186/s13033-015-0013-y

27. Tran HV, Nong HTT, Tran TTT, Filipowicz TR, Landrum KR, Pence BW, et al. Adaptation of a problem-solving program (Friendship bench) to treat common mental disorders among people living with HIV and AIDS and on methadone maintenance treatment in Vietnam: formative study. JMIR Formative Res. (2022) 6:e37211. doi: 10.2196/37211

28. Pineros-Leano M, Desrosiers A, Piñeros-Leaño N, Moya A, Canizares-Escobar C, Tam L, et al. Cultural adaptation of an evidence-based intervention to address mental health among youth affected by armed conflict in Colombia: An application of the ADAPT-ITT approach and FRAME-IS reporting protocols. Global Ment Health. (2024) 11:e114. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2024.106

29. Freeman JA, Desrosiers A, Schafer C, Kamara P, Farrar J, Akinsulure-Smith AM, et al. The adaptation of a youth mental health intervention to a peer-delivery model utilizing CBPR methods and the ADAPT-ITT framework in Sierra Leone. Transcultural Psychiatry. (2024) 61:3–14. doi: 10.1177/13634615231202091

30. Bitew T, Keynejad R, Myers B, Honikman S, Medhin G, Girma F, et al. Brief problem-solving therapy for antenatal depressive symptoms in primary care in rural Ethiopia: Protocol for a randomised, controlled feasibility trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. (2021) 7:35. doi: 10.1186/s40814-021-00773-8

31. Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. J Abnormal Child Psychol. (1995) 23:67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01447045

32. Cardemil EV. Cultural adaptations to empirically supported treatments: A research agenda. Sci Rev Ment Health Practice: Objective Investigations Controversial Unorthodox Claims Clin Psychology Psychiatry Soc Work. (2010) 7:8–21.

34. Bah AJ, Wurie HR, Samai M, Horn R, Ager A. Idioms of distress and ethnopsychology of pregnant women and new mothers in Sierra Leone. Transcultural Psychiatry. (2024).

35. Horn R, Sesay SS, Jalloh M, Bayoh A, Lavally JB, Ager A. Expressions of psychological distress in Sierra Leone: Implications for community-based prevention and response. Global Ment Health (Cambridge England). (2020) 7:e19. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2020.12

36. Chibanda D, Mesu P, Kajawu L, Cowan F, Araya R, Abas MA. Problem-solving therapy for depression and common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: Piloting a task-shifting primary mental health care intervention in a population with a high prevalence of people living with HIV. BMC Public Health. (2011) 11:828. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-828

37. Haas AD, Kunzekwenyika C, Manzero J, Hossmann S, Limacher A, van Dijk JH, et al. Effect of the friendship bench intervention on antiretroviral therapy outcomes and mental health symptoms in rural Zimbabwe: A cluster randomized trial. JAMA Network Open. (2023) 6:e2323205. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.23205

38. Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, Roberts C, Creed F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London England). (2008) 372:902–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61400-2

39. Murray LK, Familiar I, Skavenski S, Jere E, Cohen J, Imasiku M, et al. An evaluation of trauma focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children in Zambia. Child Abuse Negl. (2013) 37:1175–85. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.017

40. Ertl V, Pfeiffer A, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Community-implemented trauma therapy for former child soldiers in Northern Uganda: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. (2011) 306:503–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1060

41. Bolton P, Bass J, Neugebauer R, Verdeli H, Clougherty KF, Wickramaratne P, et al. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. (2003) 289:3117–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3117

42. Bass J, Neugebauer R, Clougherty KF, Verdeli H, Wickramaratne P, Ndogoni L, et al. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: 6-month outcomes: Randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. (2006) 188:567–73. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.6.567

43. Bolton P, Bass J, Betancourt T, Speelman L, Onyango G, Clougherty KF, et al. Interventions for depression symptoms among adolescent survivors of war and displacement in northern Uganda: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. (2007) 298:519–27. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.519

44. Petersen I, Bhana A, Baillie K, MhaPP Research Programme Consortium. The feasibility of adapted group-based interpersonal therapy (IPT) for the treatment of depression by community health workers within the context of task shifting in South Africa. Community Ment Health J. (2012) 48:336–41. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9429-2

45. Petersen I, Hanass Hancock J, Bhana A, Govender K. A group-based counselling intervention for depression comorbid with HIV/AIDS using a task shifting approach in South Africa: A randomized controlled pilot study. J Affect Disord. (2014) 158:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.013

46. Bengtson AM, Filipowicz TR, Mphonda S, Udedi M, Kulisewa K, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. An intervention to improve mental health and HIV care engagement among perinatal women in Malawi: A pilot randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. (2023) 27:3559–70. doi: 10.1007/s10461-023-04070-8

47. Bernal G. Intervention development and cultural adaptation research with diverse families. Family Process. (2006) 45:143–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00087.x

48. Bah AJ, Wurie HR, Samai M, Horn R, Ager A. A. Developing and validating the Sierra Leone perinatal psychological distress scale through an emic-etic approach. J Affect Disord Rep. (2025) 19:100852. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2024.100852

49. Bitew T, Keynejad R, Myers B, Honikman S, Sorsdahl K, Hanlon C. Adapting an intervention of brief problem-solving therapy to improve the health of women with antenatal depressive symptoms in primary healthcare in rural Ethiopia. Pilot Feasibility Stud. (2022) 8:202. doi: 10.1186/s40814-022-01166-1

50. Lund C, Tomlinson M, Patel V. Integration of mental health into primary care in low-and middle-income countries: The PRIME mental healthcare plans. Br J Psychiatry. (2016) 208:s1–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153668

51. Rahman A, Fisher J, Bower P, Luchters S, Tran T, Yasamy MT, et al. Interventions for common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. (2013) 91:593–601I. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.109819

52. Kirmayer LJ, Fung K, Rousseau C, Lo HT, Menzies P, Guzder J, et al. Guidelines for training in cultural psychiatry. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. (2021) 66:195–246. doi: 10.1177/0706743720907505

53. Fernando S, Brown T, Datta K, Chidhanguro D, Tavengwa NV, Chandna J, et al. The Friendship Bench as a brief psychological intervention with peer support in rural Zimbabwean women: A mixed methods pilot evaluation. Global Ment Health (Cambridge England). (2021) 8:e31. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2021.32

54. Chibanda D, Shetty AK, Tshimanga M, Woelk G, Stranix-Chibanda L, Rusakaniko S. Group problem-solving therapy for postnatal depression among HIV-positive and HIV-negative mothers in Zimbabwe. J Int Assoc Providers AIDS Care (JIAPAC). (2014) 13:335–41. doi: 10.1177/2325957413495564

55. Chinoda S, Mutsinze A, Simms V, Beji-Chauke R, Verhey R, Robinson J, et al. Effectiveness of a peer-led adolescent mental health intervention on HIV virological suppression and mental health in Zimbabwe: Protocol of a cluster-randomised trial. Global Ment Health (Cambridge England). (2020) 7:e23. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2020.14

56. Munetsi E, Simms V, Dzapasi L, Chapoterera G, Goba N, Gumunyu T, et al. Trained lay health workers reduce common mental disorder symptoms of adults with suicidal ideation in Zimbabwe: A cohort study. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:227. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5117-2

57. Marsiglia FF, Booth JM. Cultural adaptation of interventions in real practice settings. Res Soc Work Pract. (2015) 25:423–32. doi: 10.1177/1049731514535989

58. Collins SE, Clifasefi SL, Stanton J, Straits KJE, Espinosa PR, Andrasik MP, et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am Psychol. (2018) 73:884–98. doi: 10.1037/amp0000167

Keywords: cultural adaptation, perinatal, psychological distress, lay health worker, task-sharing

Citation: Bah AJ, Wurie HR, Samai M, Horn R and Ager A (2025) The cultural adaptation of the Friendship Bench Intervention to address perinatal psychological distress in Sierra Leone: an application of the ADAPT-ITT framework and the Ecological Validity Model. Front. Psychiatry 16:1441936. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1441936

Received: 31 May 2024; Accepted: 22 January 2025;

Published: 19 February 2025.

Edited by:

Stephan Zipfel, University of Tübingen, GermanyReviewed by:

Farooq Naeem, University of Toronto, CanadaDixon Chibanda, University of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe

Copyright © 2025 Bah, Wurie, Samai, Horn and Ager. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abdulai Jawo Bah, MTcwMTEzNjBAcW11LmFjLnVr

Abdulai Jawo Bah

Abdulai Jawo Bah Haja Ramatulai Wurie

Haja Ramatulai Wurie Mohamed Samai2

Mohamed Samai2 Rebecca Horn

Rebecca Horn Alastair Ager

Alastair Ager