- 1School of Nursing, China Medical University, Shenyang, Liaoning, China

- 2School of Nursing, Li Ka Shing (LKS) Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 3Centre for Applied Dementia Studies, University of Bradford, Birmingham, United Kingdom

Background: There is a gap between the principles of person-centred dementia care and their actual implementation. However, scoping reviews of the barriers and facilitators to implementing person-centred dementia care in long-term care facilities for Western countries and Asian countries are lacking.

Objective: To identify and compare the barriers and facilitators to implementing person-centred dementia care in long-term care facilities between Western and Asian countries.

Methods: In line with Arksey and O’Malley’s methodology, a scoping review was conducted and is reported following PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Nine English language databases and three Chinese databases were searched to identify qualitative and quantitative research studies published in English and Chinese. Thematic analysis was used to summarise and characterize the barriers and facilitators to implementing person-centred dementia care in long-term care facilities for Western and Asian countries.

Results: Thirty-three studies were included. Over half were conducted in Western countries (n =20). Barriers and facilitators were grouped under four high level themes: Nursing and care staff factors, people living with dementia and family factors, organizational factors, and resource factors. Inadequate knowledge of person-centred care, staffing shortages, time constraints, and low wages were the principal barriers to implementing person-centred dementia care in both Western and Asian countries.

Conclusions: The findings indicate that staff encounter numerous obstacles and needs in implementing person-centred care for people living with dementia in long-term care settings. Educational levels of nursing staff in Western countries were generally higher compared to Asian countries. Additionally, work-related injuries and stigma associated with dementia care presented unique challenges for nursing staff in Asia and were not cited in Western studies. Conversely, family-related factors were more frequently and elaborately cited as influencing person-centred dementia care in Western long-term care facilities. Moreover, Asian studies identified a significant lack of educational training support for person-centred dementia care, as well as shortages in staffing and poor availability of personalized, home-like environments

1 Introduction

Person-centred dementia care (PCDC) is characterized by an approach that is individualized and based on holistic understanding of how dementia affects each person in the context not only of their cognitive difficulties but also their personality, biography, health and relationships (1). The terms PCDC and person-centred care are often used synonymously but person-centred care is also used in a wider sense to refer to any individualized care (2). Therefore in this paper, we used the term PCDC throughout, to refer to care based on Kitwood’s model for understanding each individual person with dementia. The person-centred approach to dementia care was developed more than 25 years ago (3), and is now considered the gold-standard practice in care (4). Alzheimer’s Disease International (2022) recommend that care should be person-centred as well as culturally appropriate. Despite this wide recognition of its value, a gap between theory and practice persists, with significant disparities in PCDC across different countries and regions. For instance, it has been found that in China the prevailing approach to dementia care is often characterized by a medical focus, a disease-centric perspective, and a task-oriented methodology (5, 6). Care providers typically emphasize routines and tasks over the personalized preferences of individuals with dementia (7). In contrast, Western Europe, North America and Australia have seen a shift in the last twenty years towards the aspiration to deliver PCC that is relationship-driven, collaborative, and holistic. This approach prioritizes the quality of life of people with dementia by fostering a sense of community and belonging between staff and care recipients (8).

Due to the earlier demographic transition in Western countries (9), which led to an ageing population, strategies such as PCDC were initially developed in these regions to address the increasing number of people developing dementia (10). Asian countries have more recently undergone demographic changes, and have adopted best practices in dementia care, including PCDC, from Western countries to guide their developing dementia services as their populations age (11). PCDC is founded on caring by understanding each person’s needs. Expression of individual needs and viewpoints is consistent with the Western ethos of individualism and freedom (12), which may facilitate the implementation of PCDC. By contrast, the influence of Confucianism in Asian countries, means these cultures often emphasize collective interests, with individual needs frequently being subsumed under the broader community agenda (13). Asian cultures value humility, leading to more indirect and restrained personal expression. This cultural backdrop may mean those with dementia feel uncomfortable expressing their needs and may also subtly influence the attention long-term care staff pay to unique individual needs (14). These could be barriers to the adoption of PCDC. Thus, questions have been raised about the effectiveness of transferring care principles across different cultural and systemic contexts (15). Comparing PDCD across these two contexts can help to understand whether the concept is transferable between environments, address its applicability in these new settings and identify whether it might need adaptation in its implementation (16). Consequently, this paper aims to compare key differences and similarities in barriers and facilitators to PCDC between Western and Asian countries. This should have significant practical implications and provide theoretical and empirical insights.

Several reviews have addressed the barriers and facilities to implementing PCDC experienced by nursing home staff (17–19). However, to date there have been no comprehensive scoping reviews comparing the barriers and facilitators of PCDC between Western and Asian countries. Kim and Park’s (18) review excluded observational and qualitative studies, while Guney et al. (17) restricted their review to qualitative studies of the perceptions of nurses and nursing assistants. The review by Kim and Park includes studies exclusively from Western countries, while Güney’s review contains only one study from an Asian country (South Korea), with the rest being from Western countries. In addition, Lee et al. (19) was limited to qualitative studies reporting the experience of implementation of PCDC, and the included countries were mainly Western, so excluding Asian literature. Conversely, Wang et al. (6)’s meta-synthesis only reports on PCDC in China. Searches of the Cochrane Library, PROSPERO, and JBI Library of Systematic Reviews confirmed that similar reviews did not exist.

To facilitate the implementation of PCDC, it is essential to understand the contextual barriers to providing this type of care, especially as some of these may be culturally determined or influenced by the societal context. In this review, we have defined Western countries as those with cultural ties to Europe, including nations in Western Europe, North America, and Australasia, such as the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (20). These countries have the longest established aging populations. Asian countries are defined as those located on the Asian continent, including East Asia (e.g., China, Japan), Southeast Asia (e.g., Thailand, Vietnam), South Asia (e.g., India, Pakistan), Central Asia (e.g., Kazakhstan), and Western Asia (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Turkey) (21). These countries generally share a more collectivist culture and have experienced rapid ageing of their populations more recently. Barriers refer to factors that hinder the implementation of PCDC in long-term care facilities, and facilitators refer to factors that promote the implementation of PCDC. Therefore, in this review, we compare facilitators of and barriers to the implementation of PCDC between Asian and Western countries for people with dementia who are receiving long-term care.

2 Methods

In accordance with the methodology of Arksey and O’Malley (22), we conducted a scoping review. We report our study in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (23) for reporting scoping reviews. Through several meetings, the review team developed the protocol for conduct of each stage of the review. As this paper aims to provide a comprehensive overview rather than evaluate the quality of the literature, in line with Arkey and O’Malley’s approach, a quality assessment was not conducted (22).

2.1 Research question

Our purpose was to synthesize research literature on facilitators of and barriers to the implementation of PCDC in long-term care facilities in Asian and Western countries. We asked two main research questions:

1. What are the facilitators of and barriers to the implementation of PCDC in long-term care facilities in Asian and Western countries?

2. How do the facilitators of and barriers to the implementation of PCDC in long-term care facilities compare between Asian and Western countries?

2.2 Search strategy

The phenomena of interest were identified, a research context was established, and a framework for the search terms was created (24). The phenomena of interest included facilitators of and barriers to the implementation of PCDC. The research context was long-term care facilities in Asian and Western countries. Formal caregivers play a pivotal role in providing PCDC and face unique challenges critical to improving care quality. Therefore, our study included participants who were formal caregivers, either nursing or other paid staff. Where studies also included people living with dementia and their family members, this was acceptable as long as formal caregivers were included. Our focus was on the barriers and facilitators experience by formal caregivers. These could be at an individual level or within the system of care, such as organizational, cultural, social, political, and economic influences on delivery of PCDC (Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in (Table 1).

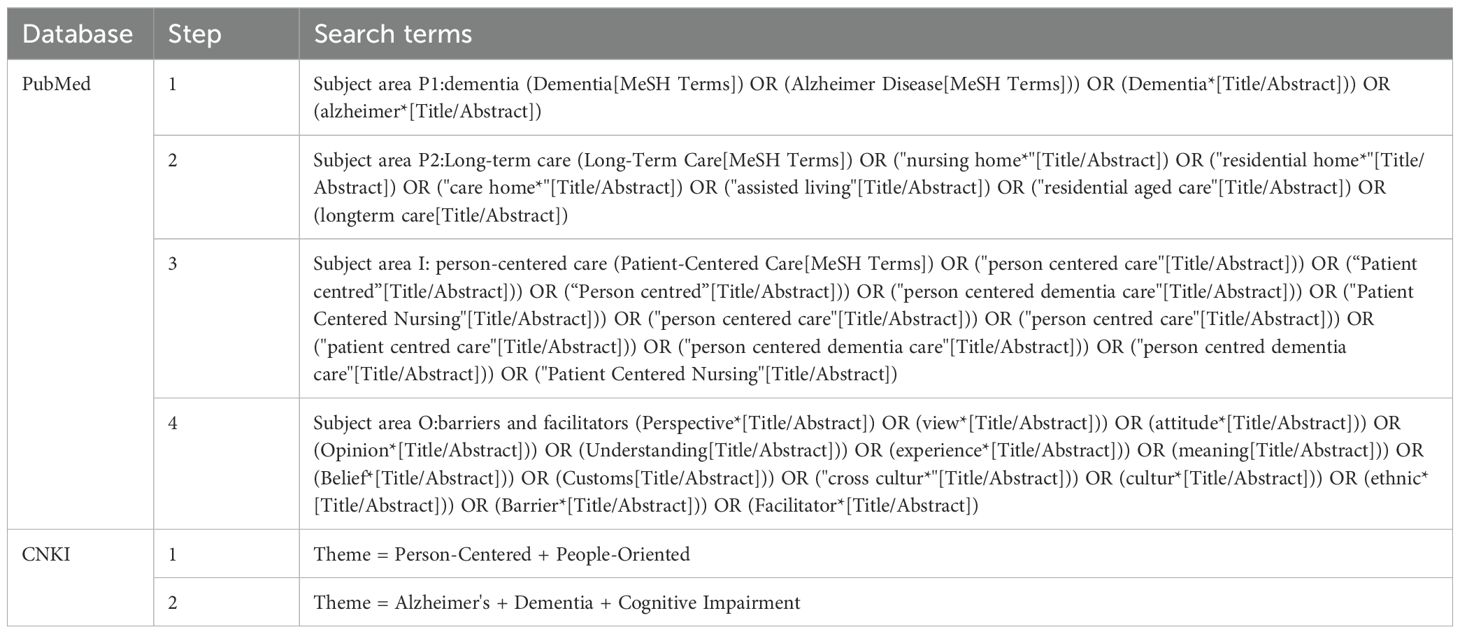

We consulted an information science expert and a research librarian to develop suitable search strategies. Using nine international databases (Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, Medline, PsycINFO, ProQuest, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) and three Chinese databases (China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang, and China Biology Medicine (CBM)), we conducted a comprehensive search. The search period began with database inception and ended in November 2024. We restricted language to Chinese and English. The search strategy for Chinese-language studies used Chinese search terms and was based on CNKI, and the search strategy for English-language studies used English terms and was based on PubMed (see Table 2). Using mesh subject headings (MESH) and free-text keywords for “nurse” or “nursing,” we then modified the strategy to be suitable for each database (see the Supplementary Material). We did not restrict search terms on study design; however, we did not hand search journals or supplementary grey materials. All the studies included in our scoping review are provided in the reference list.

2.3 Eligibility and study selection

Title and abstract screening, in accordance with our inclusion criteria, as well as full-text review, were conducted by GX and Am-D to ensure consistency and confirm the inclusion of relevant articles. To extract data from the included studies and to synthesize evidence, we used a standardised, piloted form. Authors, country, year, title, objectives, study design and setting, participants, data collection, type of analysis, and main findings or conclusions were extracted and tabulated. We also extracted the facilitators of and barriers to the implementation of PCDC in long-term care facilities in Asian and Western countries. After data extraction by one review author (XG), other members of the review team (Am-D, YL, JO) cross-checked the findings. The review team met regularly to discuss and resolve any ambiguity.

2.4 Collating the results

Braun’s thematic analysis method (25) was used to collate the findings into themes and categories of facilitators and barriers to dementia care. The process involved several steps: Firstly, the included literature was thoroughly read to gain familiarity with its content. Secondly, the material on barriers and facilitators to PCDC that had been extracted was coded into initial themes. We assigned initial codes to qualitative study findings and to variables from quantitative studies. Thirdly, initial codes were categorized into latent themes and sub-themes. Fourthly, potential themes and sub-themes underwent further scrutiny and validation, based on criteria of internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity. Some themes were subsequently divided, merged, or removed. Finally, each theme was clearly defined and labelled.

Coding, thematic categorization, and theme refinement were conducted independently by two researchers, with subsequent discussions to ensure consistency and accuracy (XG, Am-D). In cases of disagreement, consensus was reached through discussion with two experienced qualitative research professors (JO, YL) to ensure the best possible categorisation. Excel software facilitated organization, coding, and validation of the data analysis process.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

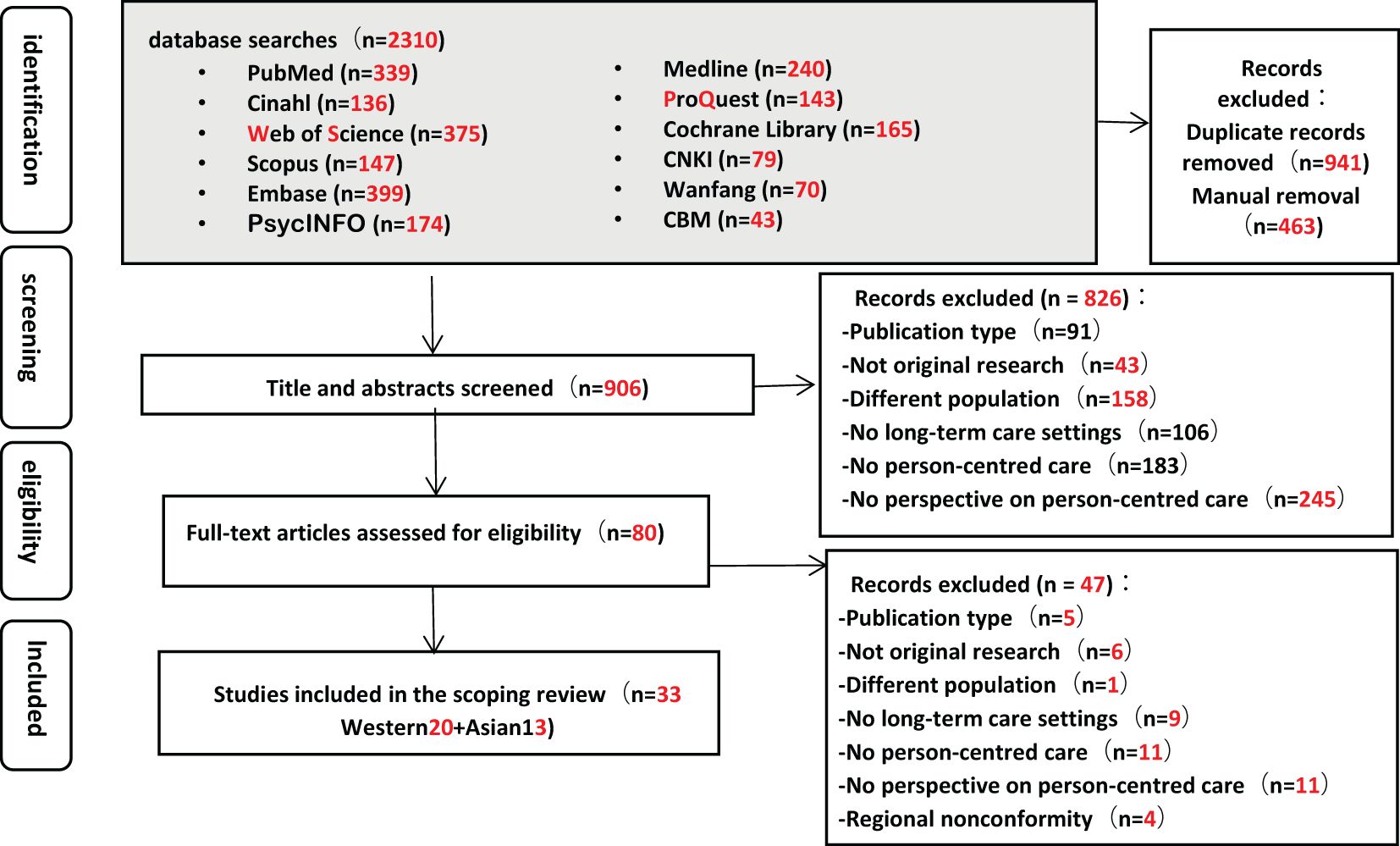

Of the 2,310 articles identified in the search, 80 underwent full-text screening, resulting in final selection of 33 studies (5, 6, 26–56) (see Figure 1). The steps followed and the number of records included or excluded at each stage are summarised in Figure 1.

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

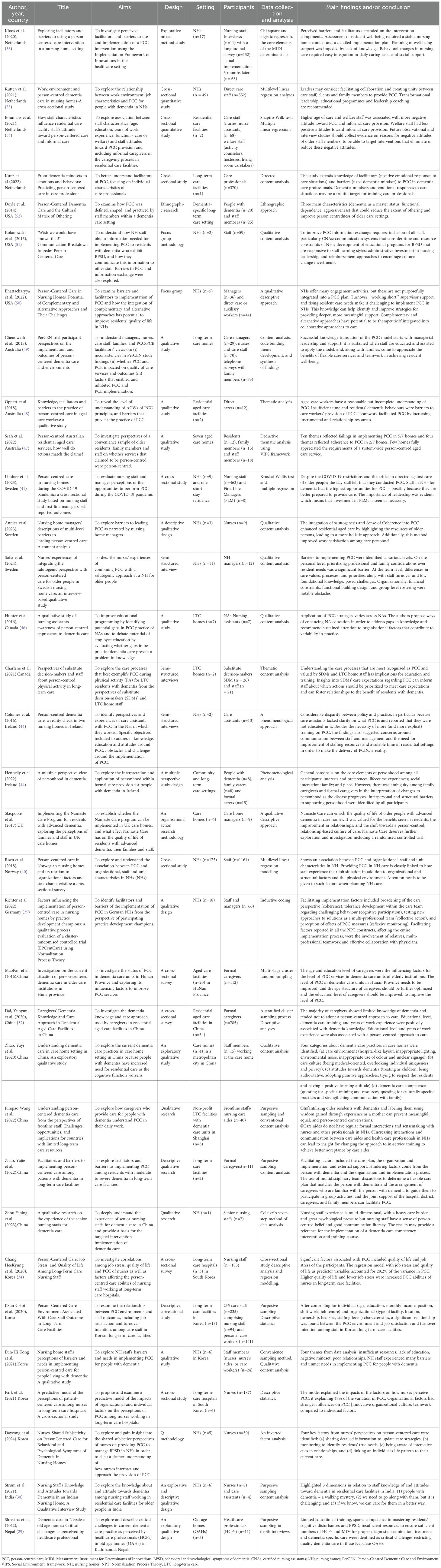

The characteristics of the included studies are listed in Table 3. Most studies (n=24) (5, 6, 26–37, 39, 41, 43, 45, 47, 50, 53–56) were published after 2020, with the publication period ranging from 2014 to 2023. Only one Asian paper had been published pre-2020, whereas eight Western papers had been published pre-2020. More than half (n=20) (26, 28, 39–56) were conducted in Western countries, including the Netherlands (n=4) (53–56), the United States (n=3) (50–52), Australia (n=3) (47–49), Sweden (n=3) (26, 28, 41), Canada (n=2) (45, 46), Ireland (n=2) (43, 44), and others (n=3) (39, 40, 42). Twelve studies were conducted in Asian countries, including China (n=6) (5, 6, 35–38), South Korea (n=5) (27, 31–34) and others (n=2) (29, 30). One of the studies (56) used mixed methods, nine (31, 34, 37, 38, 40, 41, 53–55) used quantitative methods and twenty-three (5, 6, 26–30, 32, 33, 35, 36, 39, 42–52) employed a qualitative design (see Table 3). Across all studies, a total of 4,879 care staff participated, with sample sizes ranging from 7 to 1,161 participants. Qualified nurses and nursing assistants constituted 95% of the participants, while the remainder were other healthcare professionals, individuals with dementia and family carers. Twenty-nine studies (5, 6, 26, 27, 30–41, 43–52, 54–56) included qualified and assistant nurses. Other studies also included managers (26, 39, 41, 42, 49, 50), welfare staff (54), healthcare professionals (29), and substitute decision-makers (45). Doyle and Rubinstein (52) observed people with dementia as well as formal caregivers, while three studies (43, 47, 49) interviewed care staff, people living with dementia, and family members. The majority of the research was conducted in nursing homes (n=14) (26–28, 30, 32, 35, 39–41, 44, 50, 51, 55, 56). Other care facilities were variously described as residential care (53), long-term care homes (6, 31, 33, 34, 36, 43, 45, 46, 49, 53), dementia-specific long-term care (52), residential aged care (37, 48), aged care homes (47) and long-term-care hospitals (31, 34).

3.3 Key findings

The studies included indicated that nursing staff experienced multiple facilitators of and barriers to the implementation of PCDC for people with dementia in long-term care facilities. Across the 33 studies, we identified 67 facilitators and 122 barriers to the implementation of PCC. In both Asian and Western countries, the facilitators of and barriers to care could be grouped into four broad themes. These were factors associated with people living with dementia and their families, with nursing and care staff, with resources, and with organizational influences. Descriptions of each theme and the associated barriers and facilitators are presented in Table 4.

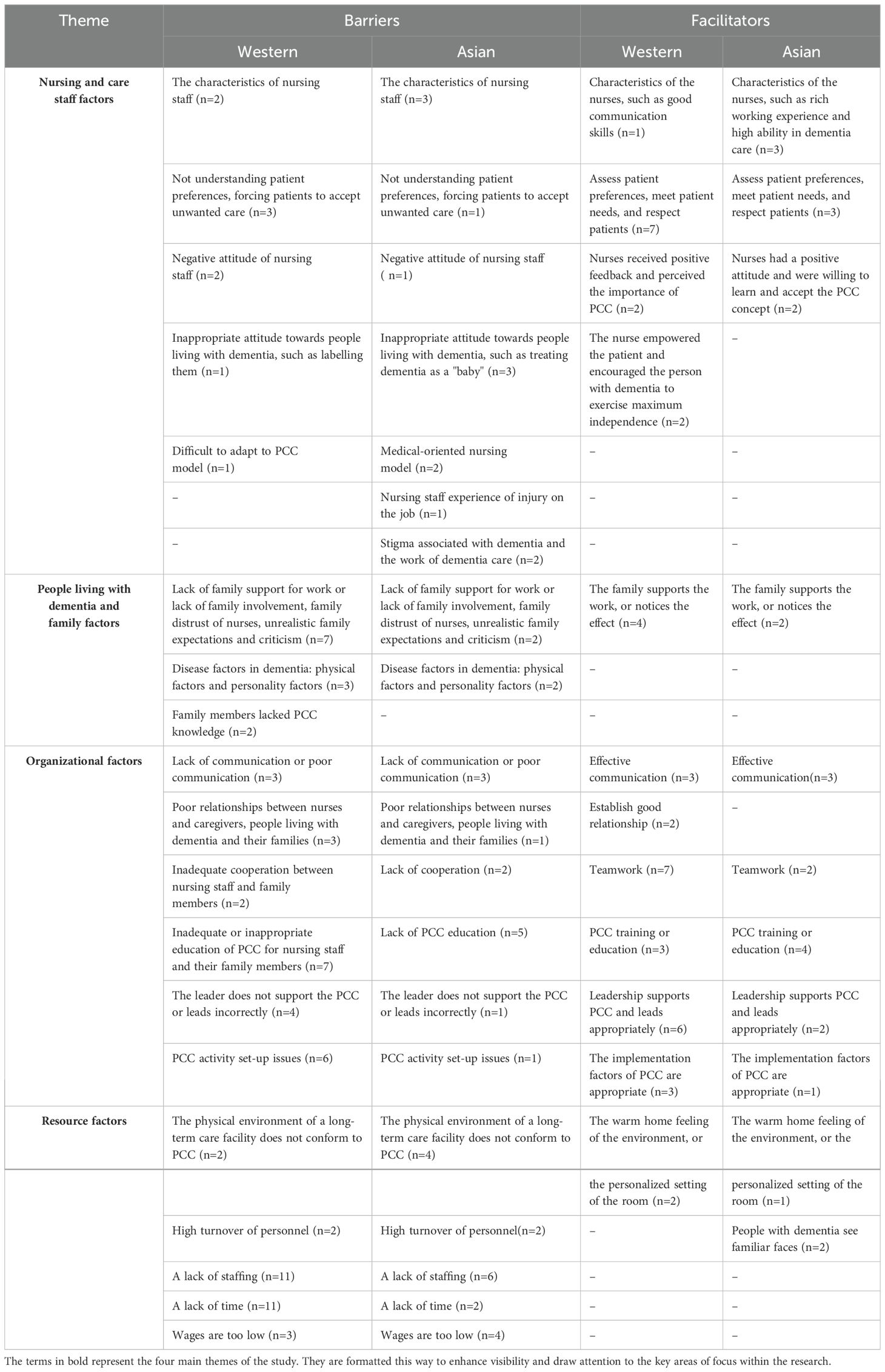

Table 4. Barriers and facilitators to implementing person-centred care in long-term care facilities. (Number of studies shown in brackets).

3.3.1 Nursing and care staff factors

Nursing and care staff’s personal characteristics were important factors affecting the implementation of PCDC. Staff being older (36), having lower education (38), not understanding residents’ preferences (6), forcing residents to accept unwanted care (6), and negative attitude towards PCDC (32) were identified as barriers to PCDC in both Western and Asian countries, while staff’s rich past work experience (34), high educational background (34), skill in assessing residents’ preferences (51), meet residents’ needs (46), respect for residents (50), receiving positive feedback from residents and perceiving PCDC (49) as important were facilitators. Nursing and care staff in Asian countries faced some barriers not mentioned in Western studies; in particular, nursing staff experienced injuries from people living with dementia and also experienced stigma associated with working in dementia care. The cause of such injuries is not known but the behaviour of those with dementia would most likely result from a combination of factors connected with cognitive impairment and reactions connected with fear. Injuries from residents led to caregivers feeling hurt and helpless, and became a barrier that discouraged them from providing person-centred care (32). Studies of Asian countries found more staffing-related barriers to delivering PCDC compared to Western countries. In Western studies, a unique facilitator was staff empowering the person with dementia to maintain appropriate levels of independence. This was categorized under caregiver factors by the authors of the original study and it implies that this staff skill contributes to staff ability to foster PCDC (43).

3.3.2 People living with dementia and family factors

In both Western and Asian countries, common barriers to PCDC included lack of family support for the work of nursing and care staff, lack of family involvement, family distrust of nurses, unrealistic family expectations, and criticism. Facilitators were when families supported the care staff’s work or noticed the positive effect of PCC practices. The papers reviewed suggested that criticism from families often stemmed from having very high expectations of nursing homes. These unrealistically high expectations could undermine caregivers’ confidence and elevate their psychological stress, impacting their motivation to provide PCDC as ‘nothing is ever good enough (49). Only Western countries reported that family members’ lack of PCDC knowledge was a barrier (43): some family members lacked knowledge of dementia and PCDC, making it difficult for them to accept that the condition of people living with dementia was not improving or was deteriorating. They often believed that the worsening condition was due to the care staff not taking good care of their relatives. Additionally, our study found barriers to delivering PCDC related to individuals with dementia. Staff found the complexities of dementia, including physical impairments and psychological changes, made it hard for them to provide PCDC. In addition, when individuals living with dementia expressed irritability or aggressive behaviour, staff were discouraged from approaching them (48). This hindered PCDC by making it difficult for staff to understand and respond to their needs and preferences. Western studies reported more barriers and facilitators related to individuals with dementia and family factors compared to Asian studies.

3.3.3 Organizational factors

This theme includes factors related to organizational culture, leadership and working arrangements, such as communications, interpersonal relationships, teamwork, education, and training. This factor is less reported in studies of Asian countries than those of Western countries but the subthemes are mostly consistent across both. In Western and Asian studies, the most frequent barriers were inadequate education and training about PCDC for nursing staff (6, 44). In Western studies, a unique barrier identified was the lack of education about dementia for family members. Western studies also reported more issues related to the setup of PCDC activities, such as the need for clear PCDC implementation plans and assistance in prioritizing tasks for staff (56). For Western countries, cohesive team working, leadership support and having an appropriate leadership style were the most common facilitators, while for Asian countries, the most frequent facilitator was PCDC training or education.

3.3.4 Resource factors

Barriers related to lack of resources were common across both Western and Asian countries and included that the physical environment of long-term care facilities did not enable PCDC; lack of staff time; lack of staffing; high turnover of personnel, and wages being too low. Prominent in reports from Western countries were lack of time and staffing to deliver PCDC. Studies of Asian countries also highlighted lack of staffing but, in addition, the poor care environment and low staff wages were prominent barriers (5). Facilitators in Western countries were a warm homely environment and the personalized setting of residents’ rooms but this was also reported in one Asian study (49).

Both Western and Asian studies reported that staff faced heavy workloads, resulting in insufficient time to provide PCDC. Furthermore, studies indicated that high workloads and long hours contributed to employee fatigue, not least as staffing shortages made taking leave a challenge, and training or shift changes sometimes extended working hours (6, 44). These pressures led staff to prioritize rest once basic tasks were done, rather than spending time on PCDC (32, 46). Additionally, high turnover rates in nursing homes undermined team stability, hindering the establishment of relationships between staff and people with dementia, which in turn obstructed the implementation of PCDC (33, 50). Both Western and Asian studies reported low wages and poor benefits for employees, leading staff to feel that their hard work was undervalued, further diminishing their motivation to provide high-quality PCDC (34, 43).

One facilitator related to continuity of staffing which was only reported in Asian studies was that people with dementia saw familiar faces (6). This was seen as contributing to residents’ sense of security, as they experienced greater emotional support through interacting with familiar staff. This facilitator appeared to help staff provide PCDC, as they had the opportunity to develop in-depth understanding of individuals’ histories and interests. This could then be used to evoke memories and facilitate emotional communication. This, in turn impacted on factors associated with the person with dementia, as such relationships enabled individuals to express their needs more comfortably, thereby improving relational understanding and fully embodying the PCDC philosophy.

On the whole, across the studies reviewed, there were shared themes at the higher level, more barriers and facilitators were reported by studies conducted in Western countries than in Asian countries but also both Western and Asian countries had some unique factors.

4 Discussion

This study reviewed the literature to establish barriers and facilitators to the implementation of PCDC in long-term care settings in Western and Asian countries. The results were grouped under four high level factors, related to nursing and care staff, people living with dementia and their families, the organization, and resources. Aspects of each are discussed below. We discuss in some depth the possible reasons for several factors and comment on the differences between barriers and facilitators to PCDC in Asian and Western countries.

Among nursing and care staff factors, older age, lower education and lack of knowledge were common barriers to PCDC across both Western and Asian countries, despite the different care contexts. Some studies have shown that the educational level of formal caregivers is positively correlated with the level of PCDC (5). It is possible that this is a more severe barrier in Asian countries. One Chinese study found that 80% of caregivers in nursing homes were illiterate or semi-illiterate, whereas a US study showed that 87% of caregivers had a high school diploma or equivalent (41). The educational level of nurses in Asian countries therefore may limit their understanding, learning and adaptation to the PCDC model (57).

Our review found injuries sustained at work at the hands of people with dementia, and stigma associated with the job were barriers in Asian dementia care but were not reported in Western research. Other researchers have also found that nurses in Asian countries face highly challenging social situations and are more likely to receive physical abuse from people with dementia or their families (56). In addition, in the Asian context, nurses in nursing homes are often perceived as having undignified jobs, resulting in a sense of professional shame (44) and low professional value, which further hampers the motivation of staff to implement PCDC (58). The culture of care in Asian countries focuses mainly on meeting physical needs of residents at the expense of supporting their uniqueness and dignity (5). Care tends to be focused only on basic personal and medical care and fails to support the unique identity of the individual (59). This is not to imply that work with people with dementia is of high status in Western countries, as there are reports of occupational stigma being associated with dementia care work (60), only that this has not been reported as a barrier to PCDC in the studies reviewed.

The Western studies in our review reported unique facilitators in dementia care, emphasizing the role of nurses in empowering individuals with dementia to achieve maximum independence. In PCDC, this empowerment is regarded as essential for enhancing quality of life. Research suggests that encouraging individuals living with dementia to participate in self-care and daily activities, where possible, not only boosts their self-esteem but also improves emotional well-being, potentially slowing cognitive decline (5). Additionally, personalized care plans tailored to individual abilities, can significantly enhance people’s sense of involvement and promote independence (61). This implies that it is imperative that nurses and other care staff prioritize empowerment within their implementation of PCDC to enhance both independence and quality of life for individuals living with dementia.

Most barriers and facilitators linked with people living with dementia and their families were shared across Western and Asian studies. The challenge of implementing PCDC arises from a combination of contextual factors, the nature of cognitive impairment, and the approach taken by staff members. From the perspective of individuals living with dementia, reactions to these factors highlight the difficulties in implementing PCDC. Lack of family involvement and lack of family support are understandable within the different societal contexts of Western and Asian countries. In both Asian and Western cultures, the term “dementia” carries negative connotations (62, 63), with symptoms of dementia leading to significant social and personal stigma. This stigma is particularly pronounced in Asian countries (64) where individuals and their families often feel embarrassed in social contexts (65). Family members may feel guilty for allowing their relatives with dementia to be cared for by others (66, 67). Shame and guilt may cause family members to distance themselves from their relatives with dementia or to place blame for any care issues on the caregivers. This, in turn, can hinder nursing and care staff from providing effective PCDC, as it obstructs access to crucial information about residents’ life histories and personal preferences.

While there were no sub-themes connected with people with dementia and families that were unique to either the Western or Asian context, there was much more detailed and specific reporting of barriers and facilitators in Western studies, while studies in Asian countries were based more on the perceptions of formal caregivers than on practice. This is likely to reflect that PCDC has been embedded in policies, education and guidelines for over two decades in Western countries, whereas Asian countries have less knowledge of PCDC at this stage (19). Similarly, PCDC training, education and support for managers is more lacking in Asian countries (3, 15, 46). While Western countries face some challenges with training resources, they generally provide more comprehensive and specialized educational programs (68). In contrast, Asian countries often experience a significant deficit in specialized training for PCDC, with existing training programs facing several issues, such as scheduling sessions during staff time off, repetitive content, and a disconnect from practical applications (30, 31, 41, 49).

Supportive leadership and teamwork are recognized as important facilitators in both regions. In Western contexts, supportive leadership styles effectively encouraged staff participation in care activities, which is particularly crucial in the emotionally and cognitively complex environment of dementia care (53). Although families play a critical caregiving role within Asian culture (69), only Western studies highlighted the need for educating family members (41). Our findings and the allied literature imply that Asian countries could facilitate better PCDC by fostering family collaboration and involving family members in education of staff.

Lack of resources was widely reported by both Western and Asian studies, with formal caregivers reporting being understaffed and overworked. PCDC is often seen as requiring time to learn and implement, even if this is a misunderstanding (70). The degree of staff and time shortage appears more profound in Asian than in Western long-term care contexts (71). The environment has an impact on the behaviour and health of people with dementia, as well as on care staff, and is a key to good quality of life in long-term care settings (72). Homely environments and opportunities for residents to have individualized rooms were found to be facilitators of PCDC in some studies in Western countries. In contrast, Asian countries have a greater lack of personalised, homely designed environments (5), as well as problems with multiple shared rooms (31), poor lighting, ambient noise, inappropriate use of colour and unclear signage (5). This highlights the benefits to delivering PCDC that are available in more highly-resourced economies. On the other hand, although staff turnover is an issue in both Western and Asian countries, it is reported more frequently in Asian countries. In Western countries, staff groups often include both long-term local staff and young individuals from immigrant backgrounds (73). However, having familiar staff was reported as a positive facilitator of PCDC only in Asian research studies. This suggests that reducing staff churn or turnover in long-term care facilities would be particularly beneficial in enhancing PCDC.

To effectively promote the implementation of PCDC, comprehensive recommendations are proposed across multiple domains. It is suggested that media in both Western and Asian countries have a responsibility to actively disseminate authentic narratives related to dementia care within long-term care facilities, highlighting the efforts and contributions of staff. This would facilitate a more nuanced public understanding of dementia and caregiving roles, and help to reduce stigma associated with dementia and dementia care (74, 75). Educational curricula and continuing professional development need to incorporate modules and courses on PCDC for dementia that foster empathy and understanding among students and nursing and care staff. Information for families and communities that raises awareness about the nature of dementia, particularly in Asian contexts where family responsibilities rooted in Confucian values could be emphasized as a way of encouraging continuing involvement of families. Establishing clear PCDC policies within long-term care facilities would provide a lever to help ensure that staff receive adequate training and support on PCDC. Given the barriers to PCDC revealed through this review that are rooted in lack of resources, it is apparent that further research needs to explore whether better environments can improve resident well-being, so reducing injuries to staff and staff turnover as well as drug costs (76). Arguments around cost-effectiveness of high quality facilities may help to persuade Governments or care companies to invest in better care facilities.

5 Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this scoping review are the novelty and relevance of the topic in comparing barriers and facilitators to PCDC in long-term care settings across Western and Asian countries. The review includes a wide range of study types, a comprehensive search of databases, and the inclusion of primary peer-reviewed studies in both English and Chinese. This approach identified articles from 13 countries, contributing to the generalisability of findings. However, it is important to emphasize that these Asian studies are primarily concentrated in China and South Korea, so cannot be generalised across Asia. Our study distills a wide range of barriers and facilitators into four high level themes, offering a systematic framework for understanding both the barriers and facilitators of PCDC. In line with scoping review methodology, studies were not evaluated for quality, which may weaken the strength of our conclusions. In addition, given that Asian studies may be less extensively reported in international journals compared to Western research, it is possible some Asian research was missed. although this was mitigated to some extent by our inclusion of Chinese databases. Furthermore, the exclusive use of English and Chinese databases may have led to the omission of studies in other languages.

6 Conclusions

This review found numerous barriers to the implementation of PCDC for individuals with dementia in long-term care facilities across both Western and Asian countries. Barriers are especially pronounced in Asian countries where resources are more limited, implementation is at an earlier stage and nursing and care staff currently have lower educational levels. Additionally, nursing and care staff in Asian countries face unique challenges such as the greater cultural stigma associated with dementia care work, which further impedes the implementation of PCDC. Western studies identified more family-related factors as both barriers and facilitators of PCDC in long-term care facilities; whereas in Asian studies identified organization and resource factors including significant shortages in educational programmes, staffing, and the provision of personalized, home-like environments.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

XG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. GX: Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JO: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Postgraduate Education and Teaching Reform Research Project of Liaoning Province, China (grant numbers-LNYJG2022300), 2022 Annual Liaoning Province Department of Education Basic Research Project (grant numbers-LJKMZ20221187), 2024 Liaoning Province outstanding Student project (grant numbers-3110024174).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Liaoning Provincial Department of Education and China Medical University for providing financial support for our study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be constructed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1523501/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Brooker D. Person centred dementia care: making services better. (2006). Available online at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Person-Centred-Dementia-Care%3A-Making-Services-Brooker/35923261c9700a9a937ae94f93a9f0ab76eea266 (Accessed June 29, 2024).

2. Sharma T, Bamford M, Dodman D. Person-centred care: an overview of reviews. Contemp Nurse. (2015) 51:107–20. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2016.1150192

3. Kitwood T. Toward a theory of dementia care: ethics and interaction. J Clin Ethics. (1998) 9:23–34. doi: 10.1086/JCE199809103

4. World Alzheimer Report 2022. Life after diagnosis: Navigating treatment, care and support. London, UK: Alzheimer's Disease International (2022).

5. Zhao Y, Liu L, Ding Y, Chan HYL. Understanding dementia care in care home setting in China: An exploratory qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. (2021) 29:1511–21. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13213

6. Wang J, Bian X, Wang J. Understanding person-centered dementia care from the perspectives of frontline staff: Challenges, opportunities, and implications for countries with limited long-term care resources. Geriatr Nur (Lond). (2022) 46:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.04.020

7. Wang J. Person-centered care for older adults. In: D Gu, Dupre ME, editors. Encyclopedia of gerontology and population aging [Internet]. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2021). p. 3788–94. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-22009-9_1113

8. Fazio S, Pace D, Flinner J, Kallmyer B. The fundamentals of person-centered care for individuals with dementia. Gerontologist. (2018) 58:S10–9. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx122

9. Beard JR, Officer A, de Carvalho IA, Sadana R, Pot AM, Michel JP, et al. The World report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet Lond Engl. (2016) 387:2145–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00516-4

10. Røsvik J, Brooker D, Mjorud M, Kirkevold Ø. What is person-centred care in dementia? Clinical reviews into practice: the development of the VIPS practice model. Rev Clin Gerontol. (2013) 23:155–63. doi: 10.1017/S0959259813000014

11. WHO. Progress report on the united nations decade of healthy ageing, 2021-2023. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2023).

12. Nisbett RE. The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently … and why Vol. xxiii. . New York, NY, US: Free Press (2003). 263 p. (The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently … and why).

13. Drew (PhD) C. Collectivism vs. Individualism: Similarities and Differences(2024). Available online at: https://helpfulprofessor.com/collectivism-vs-individualism/ (Accessed December 2, 2024).

14. Sorge A, Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related values. Adm Sci Q. (1983) 28:625. doi: 10.2307/2393017

15. Mitton C, Adair CE, McKenzie E, Patten SB, Waye Perry B. Knowledge transfer and exchange: review and synthesis of the literature. Milbank Q. (2007) 85:729–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00506.x

16. Berntsen GR, Yaron S, Chetty M, Canfield C, Ako-Egbe L, Phan P, et al. Person-centered care (PCC): the people’s perspective. Int J Qual Health Care. (2021) 33:ii23–6. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzab052

17. Güney S, Karadağ A, El-Masri M. Perceptions and experiences of person-centered care among nurses and nurse aides in long term residential care facilities: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Geriatr Nurs N Y N. (2021) 42:816–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.04.005

18. Kim SK, Park M. Effectiveness of person-centered care on people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. (2017) 12:381–97. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S117637

19. Lee JY, Yang E, Lee KH. Experiences of implementing person-centered care for individuals living with dementia among nursing staff within collaborative practices: A meta-synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud. (2023) 138:104426. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104426

21. About: List of Asian countries and regions. (2024). Available online at: https://dbpedia.org/page/List_of_sovereign_states_and_dependent_territories_in_Asia (Accessed September 9, 2024).

22. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005). doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

23. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-scR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

24. Peters M, Godfrey C, Mcinerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Adelaide, Australia: Joanna Briggs Institute (2015) 1–24.

25. Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Davey L, Jenkinson E. Doing reflexive thematic analysis. In: Bager-Charleson S, McBeath A, editors. Supporting research in counselling and psychotherapy : qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research [Internet]. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2022). p. 19–38. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-13942-0_2

26. Backman A, Ahnlund P, Lövheim H, Edvardsson D. Nursing home managers’ descriptions of multi-level barriers to leading person-centred care: A content analysis. Int J Older People Nurs. (2024) 19:e12581. doi: 10.1111/opn.12581

27. Kim D, Choi YR, Lee YN, Chang SO. Nurses’ Shared subjectivity on person-centered care for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in nursing homes. J Nurs Res JNR. (2024) 32:e330. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000611

28. Ehk S, Petersson S, Khalaf A, Nilsson M. Nurses’ experiences of integrating the salutogenic perspective with person-centered care for older people in Swedish nursing home care: an interview-based qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. (2024) 24:262. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-04831-7

29. Shrestha S, Tranvåg O. Dementia care in Nepalese old age homes: Critical challenges as perceived by healthcare professionals. Int J Older People Nurs. (2022) 17:e12449. doi: 10.1111/opn.12449

30. Strøm BS, Lausund H, Rokstad AMM, Engedal K, Goyal A. Nursing staff's knowledge and attitudes towards dementia in an Indian nursing home: a qualitative interview study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra (2021) 11(1):29–37. doi: 10.1159/000514092

31. Park M, Jeong H, Giap TT. A predictive model of the perceptions of patient-centered care among nurses in long-term care hospitals: A cross-sectional study. Geriatr Nur. (2021) 42(3):687–93. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.02.019

32. Kong EH, Kim H, Kim H. Nursing home staff’s perceptions of barriers and needs in implementing person-centred care for people living with dementia: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. (2022) 31:1896–906. doi: 10.1111/jocn.v31.13-14

33. Choi J, Kim DE, Yoon JY. Person-centered care environment associated with care staff outcomes in long-term care facilities. (2021) 29(1):e133. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0000000000000412

34. Chang H, Gil C, Kim H, Bea H. Person-centered care, job stress, and quality of life among long-term care nursing staff. J Nurs Res JNR. (2020) 28:e114. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0000000000000398

35. Zhou YP, Liu J, Li T, Wang Y. A qualitative study on the dementia care experience of senior caregivers in elderly care institutions in China. Med Res And Education. (2023) 40:64–70. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-490X.2023.01.010

36. Zhao YJ, Lü XZ, Li LY, Li C, Xia MM, Xiao HM, et al. Study on the promoting and hindering factors for implementing person-centered care for dementia patients in long-term care institutions. Chin Nurs Management. (2021) 21:1491–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2021.10.012

37. Dai Y, Zhao J, Li S, Zhao C, Gao Y, Johnson CE. Caregivers’ Dementia knowledge and care approach in residential aged care facilities in China. Am J Alzheimers Dis Dementiasr. (2020) 35:153331752093709. doi: 10.1177/1533317520937096

38. Mao P, Xiao LD, Zhang MX, Xie FT, Feng H. Investigation on the current situation of person-centered care in dementia care units in nursing institutions in hunan province. J Nurs Science. (2016) 31:1–4. doi: 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2016.21.001

39. Richter C, Fleischer S, Langner H, Meyer G, Balzer K, Köpke S, et al. Factors influencing the implementation of person-centred care in nursing homes by practice development champions: a qualitative process evaluation of a cluster-randomised controlled trial (EPCentCare) using Normalization Process Theory. BMC Nurs. (2022) 21:182. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-00963-6

40. Røen I, Kirkevold Ø, Testad I, Selbæk G, Engedal K, Bergh S. Person-centered care in Norwegian nursing homes and its relation to organizational factors and staff characteristics: a cross-sectional survey. Int Psychogeriatr. (2018) 30:1279–90. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217002708

41. Lindner H, Kihlgren A, Pejner MN. Person-centred care in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross sectional study based on nursing staff and first-line managers’ self-reported outcomes. BMC Nurs. (2023) 21,22:276. doi: 10.1186/s12912-023-01437-z

42. Stacpoole M, Hockley J, Thompsell A, Simard J, Volicer L. Implementing the Namaste Care Program for residents with advanced dementia: exploring the perceptions of families and staff in UK care homes. Ann Palliat Med. (2017) 6:327–39. doi: 10.21037/apm.2017.06.26

43. Hennelly N, O’Shea E. A multiple perspective view of personhood in dementia. Ageing Soc. (2022) 42:2103–21. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X20002007

44. Colomer J, De Vries J. Person-centred dementia care: a reality check in two nursing homes in Ireland. Dementia. (2016) 15:1158–70. doi: 10.1177/1471301214556132

45. Chu CH, Quan AML, Gandhi F, McGilton KS. Perspectives of substitute decision-makers and staff about person-centred physical activity in long-term care. Health Expect. (2022) 25:2155–65. doi: 10.1111/hex.13381

46. Hunter PV, Hadjistavropoulos T, Kaasalainen S. A qualitative study of nursing assistants’ awareness of person-centred approaches to dementia care. Ageing Soc. (2016) 36:1211–37. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X15000276

47. Seah SSL, Chenoweth L, Brodaty H. Person-centred Australian residential aged care services: how well do actions match the claims? Ageing Soc. (2022) 42:2914–39. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X21000374

48. Oppert ML, O’Keeffe VJ, Duong D. Knowledge, facilitators and barriers to the practice of person-centred care in aged care workers: a qualitative study. Geriatr Nur (Lond). (2018) 39:683–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2018.05.004

49. Chenoweth L, Jeon YH, Stein-Parbury J, Forbes I, Fleming R, Cook J, et al. PerCEN trial participant perspectives on the implementation and outcomes of person-centered dementia care and environments. Int Psychogeriatr. (2015) 27:2045–57. doi: 10.1017/S1041610215001350

50. Bhattacharyya KK, Craft Morgan J, Burgess EO. Person-centered care in nursing homes: potential of complementary and alternative approaches and their challenges. J Appl Gerontol. (2022) 41:817–25. doi: 10.1177/07334648211023661

51. Kolanowski A, Van Haitsma K, Penrod J, Hill N, Yevchak A. Wish we would have known that!” Communication Breakdown Impedes Person-Centered Care. Gerontologist. (2015) 55:S50–60. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv014

52. Doyle PJ, Rubinstein RL. Person-centered dementia care and the cultural matrix of othering. Gerontologist. (2014) 54:952–63. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt081

53. Kunz LK, Scheibe S, Wisse B, Boerner K, Zemlin C. From dementia mindsets to emotions and behaviors: Predicting person-centered care in care professionals. Dementia. (2022) 21:1618–35. doi: 10.1177/14713012221083392

54. Boumans J, Van Boekel L, Kools N, Scheffelaar A, Baan C, Luijkx K. How staff characteristics influence residential care facility staff’s attitude toward person-centered care and informal care. BMC Nurs. (2021) 20:217. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00743-8

55. Rutten JER, Backhaus R, Tan F, Prins M, Roest H, Heijkants C, et al. Work environment and person-centred dementia care in nursing homes—A cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manage. (2021) 29:2314–22. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13386

56. Kloos N, Drossaert CHC, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Westerhof GJ. Exploring facilitators and barriers to using a person centered care intervention in a nursing home setting. Geriatr Nur (Lond). (2020) 41:730–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.04.018

57. Sengupta M, Harris-Kojetin LD, Ejaz FK. A national overview of the training received by certified nursing assistants working in U. S. Nurs homes. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. (2010) 31:201–19. doi: 10.1080/02701960.2010.503122

58. Zhu R, Hou W, Wang L, Zhang C, Guo X, Luo D, et al. Willingness to purchase institutionalised elderly services and influencing factors among Chinese older adults: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2024) 14:e082548. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-082548

59. Yuan Q, Yi X, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Qin L, Liu H. Study on the current situation and research progress of nursing assistants’ Stress in nursing homes. Chin Nurs Manage. (2015) 15:112–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2015.01.035

60. Manchha AV, Way KA, Tann K, Thai M. The social construction of stigma in aged-care work: implications for health professionals’ Work intentions. Gerontologist. (2022) 62:994–1005. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac002

61. Wang Q, Xiao X, Zhang J, Jiang D, Wilson A, Qian B, et al. The experiences of East Asian dementia caregivers in filial culture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1173755. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1173755

62. Devenney EM, Anh N Nguyen Q, Tse NY, Kiernan MC, Tan RH. A scoping review of the unique landscape and challenges associated with dementia in the Western Pacific region. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. (2024), 50:101192. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2024.101192

63. Racine L, Ford H, Johnson L, Fowler-Kerry S. An integrative review of Indigenous informal caregiving in the context of dementia care. J Adv Nurs. (2022) 78:895–917. doi: 10.1111/jan.15102

64. World Alzheimer Report. Global changes in attitudes to dementia. (2024). Available online at: https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2024/ (Accessed September 26, 2024).

65. van Corven CTM, Bielderman A, Wijnen M, Leontjevas R, Lucassen PLBJ, Graff MJL, et al. Empowerment for people living with dementia: An integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. (2021) 124:104098. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104098

66. Lee KH, Lee JY, Kim B. Person-centered care in persons living with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontologist. (2022) 62:e253–64. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa207

67. He J, Yao Y, Jiang L, Liu D, Jiang M, Zhang Y, et al. Analysis of the intentions of home-based pension of the elderly in China and related factors: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Military Nursing. (2024) 41:41–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2097-1826.2024.04.011

68. Surr CA, Gates C, Irving D, Oyebode J, Smith SJ, Parveen S, et al. Effective dementia education and training for the health and social care workforce: A systematic review of the literature. Rev Educ Res. (2017) 87:966–1002. doi: 10.3102/0034654317723305

69. Low LF, Purwaningrum F. Negative stereotypes, fear and social distance: a systematic review of depictions of dementia in popular culture in the context of stigma. BMC Geriatr. (2020) 20:477. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01754-x

70. George ES, Kecmanovic M, Meade T, Kolt GS. Psychological distress among carers and the moderating effects of social support. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:154. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02571-7

71. Wang J, Wu B, Bowers BJ, Lepore MJ, Ding D, McConnell ES, et al. Person-centered dementia care in China: A bilingual literature review. Gerontol Geriatr Med. (2019) 5:2333721419844349. doi: 10.1177/2333721419844349

72. Haunch K, Downs M, Oyebode J. [amp]]lsquo;Making the most of time during personal care’: nursing home staff experiences of meaningful engagement with residents with advanced dementia. Aging Ment Health. (2023) 27:2346–54. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2023.2177254

73. The King’s Fund. The adult social care workforce in A nutshell. (2024). Available online at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/data-and-charts/social-care-workforce-nutshell (Accessed December 2, 2024).

74. Kong D, Chen A, Zhang J, Xiang X, Lou WQV, Kwok T, et al. Public discourse and sentiment toward dementia on chinese social media: machine learning analysis of weibo posts. J Med Internet Res. (2022) 24:e39805. doi: 10.2196/39805

75. Yang Y, Fan S, Chen W, Wu Y. Broader open data needed in psychiatry: practice from the psychology and behavior investigation of chinese residents. Alpha Psychiatry. (2024) 25:564–5. doi: 10.5152/alphapsychiatry.2024.241804

Keywords: staff, dementia, person-centred care, barriers, facilitators, long-term care, scoping review

Citation: Guan X, Duan A-m, Xin G-k, Oyebode J and Liu Y (2025) Barriers and facilitators to implementing person-centred dementia care in long-term care facilities in Western and Asian countries: a scoping review. Front. Psychiatry 15:1523501. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1523501

Received: 06 November 2024; Accepted: 23 December 2024;

Published: 14 January 2025.

Edited by:

Yibo Wu, Peking University, ChinaReviewed by:

Jonas Debesay, Oslo Metropolitan University, NorwayLouise McCabe, University of Stirling, United Kingdom

Shih-Yin Lin, New York University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Guan, Duan, Xin, Oyebode and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jan Oyebode, Si5PeWVib2RlQGJyYWRmb3JkLmFjLnVr; Yu Liu, bGl1eXVAY211LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡ ORCID: Xin Guan, orcid.org/0009-0008-6442-5223

A-min Duan, orcid.org/0009-0000-0688-6584

Gong-kai Xin, orcid.org/0009-0001-3819-9591

Jan Oyebode, orcid.org/0000-0002-0263-8740

Yu Liu, orcid.org/0000-0002-6544-3078

Xin Guan

Xin Guan A-min Duan1†‡

A-min Duan1†‡ Gong-kai Xin

Gong-kai Xin Jan Oyebode

Jan Oyebode Yu Liu

Yu Liu