- 1Center of Research on Psychological Disorders and Somatic Diseases (CoRPS), Department of Medical and Clinical Psychology, Tilburg University, Tilburg, Netherlands

- 2Viersprong Institute for Studies on Personality Disorders, De Viersprong, Halsteren, Netherlands

- 3Clinical Centre of Excellence for Older Adults with Personality Disorders, Mondriaan Mental Health Center, Heerlen-Maastricht, Netherlands

- 4PersonaCura, Clinical Centre of Excellence for Personality and Developmental Disorders in Older Adults, GGZ Breburg, Tilburg, Netherlands

- 5Tranzo, Scientific Centre for Care and Wellbeing of the Tilburg School of Social and Behavioral Sciences of Tilburg University, Tilburg, Netherlands

- 6Personality and Psychopathology Research Group (PEPS), Department of Psychology, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Brussels, Belgium

- 7NPI Centre for Personality Disorders, Arkin, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 8Levvel, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 9Orygen, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 10Centre for Youth Mental Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Introduction: Clinical staging aims to refine psychiatric diagnosis by describing mental disorders on a continuum of disorder progression, with the pragmatic goal of improved treatment planning and outcome prediction. The first systematic review on this topic, published a decade ago, included 78 papers, and identified separate staging models for schizophrenia, unipolar depression, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, substance use disorder, anorexia, and bulimia nervosa. The current review updates this review by including new proposals for staging models and by systematically reviewing research based upon full or partial staging models since 2012.

Methods: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane databases were systematically searched from 2012 to June 2023. The original review’s eligibility criteria were used and extended with newly introduced categories of DSM-5 mental disorders, along with mental disorders for which a progressive course might be expected. Included papers: a) contained a complete or partial staging model, or b) focused upon clinical features that might be associated with stages, or c) focused upon treatment research associated with specific stages.

Results: Seventy-one publications met the inclusion criteria. They described staging models for schizophrenia and related psychoses (21 papers), bipolar (20), depressive (4), anxiety (2), obsessive-compulsive (3), trauma related (4), eating (3), personality disorders (2), and ‘transdiagnostic’ staging models (13).

Discussion: There is a steady but slow increase in interest in clinical staging and evidence for the validity of staging remains scarce. Staging models might need to be better tailored to the complexities of mental disorders to improve their clinical utility.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD42021291703.

1 Introduction

Prevailing systems of psychiatric diagnosis have been widely criticized for not capturing the heterogeneity among individuals who meet the same diagnosis (1) and for lacking a perspective on the development and longitudinal course of a mental disorder, thereby failing to capture the dynamic nature of mental disorders (2). ‘Clinical staging’ aims to refine psychiatric diagnosis by describing mental disorders along an assumed continuum of disorder progression (3), across sequential stages describing progression of disorder processes. Originally developed in the field of oncology, staging models aim to enhance prognosis prediction and guide treatment decisions. The adoption of clinical staging in psychiatry was catalyzed by McGorry and colleagues’ model (4–6) and is intended to provide a more useful clinical framework for decisions about treatment assignment and the proportionality of such treatments to the presenting problems (3, 5). Initially proposed for psychotic disorders and later adapted for other diagnoses (e.g., bipolar, anxiety and depressive disorders), the model distinguishes five main stages (0-4), with stages 1 and 3 being further subdivided. Such a sequence of stages aligns with concepts of personalized or stratified care (7), enabling professionals to tailor treatment to the specific stage of a disease, called ‘staged care’ (8). Moreover, focusing clinical attention upon early stages of mental ill-health promotes a more hopeful, and potentially more effective, mental health care system, stressing the potential for prevention and early intervention for what might be seen to be, or experienced as, a progressive and/or severe mental illness (9). Staging models aim to optimize the timing of therapeutic interventions, embracing the assumption that the later stages of a disorder might be avoided or ameliorated by identifying and treating early precursors (6, 10).

One decade ago, Cosci and Fava (11) conducted the first systematic review of staging models in psychiatry. They identified 78 publications that met their inclusion criteria, including staging models for discrete disorders such as schizophrenia, unipolar depression, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, substance use disorder, anorexia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa. The current review aims to update this review. As the concept of staging was still relatively novel in 2012, it is relevant to review progress in the field and to what extent staging models have been empirically validated. Moreover, since the 2012 review, publication of the DSM-5 introduced some changes in psychiatric nosology. Finally, the original review did not contain all mental disorders for which a progressive course might be expected (e.g., personality disorders).

The first aim was to collect new proposals for full or partial staging models since 2012. Full staging models were defined as consisting of multiple stages, comprehensively describing the full course of a disorder, while a partial staging model describes only some stages. The second aim was to provide an overview of empirical papers substantiating the reliability, validity, and clinical utility of staging models.

2 Methods

The present systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines (12) and was preregistered at PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021291703).

2.1 Eligibility criteria

Papers eligible for screening were written in English, published in a peer-reviewed journal and reported data on humans with mental disorders according to the DSM-III (13), -IIIR (14), -IV (15), 1994), -IVTR (16), or -5 (17), the Research Diagnostic Criteria (18) or the International Classification of Diseases (19). We used the same criteria as Cosci and Fava (11), meaning that the following papers were eligible for screening: category a) papers wherein a (full or partial) staging model was proposed including a motivation of its existence; category b) papers studying clinical features related to a staging model; category c) papers studying treatment interventions related to a staging model. Additional inclusion criteria for category b) were: inclusion of at least 10 patients; papers with participants with co-occurring mental or organic disorders were also included. Additional inclusion criteria for category c) were: inclusion of at least 10 patients, inclusion of a comparison group or a crossover design, at least a double-blind design in the case of pharmacological treatments, at least a single-blind design in the case of nonpharmacological treatments. Papers with a primary focus on neuroanatomy or biological markers were excluded.

2.2 Information sources and searches

The search strategy of Cosci and Fava was replicated, including the databases used by Cosci and Fava, which were Medline, psychINFO, EMBASE and Cochrane. The databases were systematically searched from May 2012 to June 2023. Reference lists of relevant systematic reviews on clinical staging and of all included papers were checked for additional papers. Search terms were ‘stage OR stages OR staging’, combined using the Boolean ‘AND’ operator with different categories of mental disorders. Abstracts, titles, and keywords were searched. We combined with the following search terms: ‘mental disorder’, ‘psychiatric disorder’, ‘mood disorder’, ‘anxiety disorder’, ‘substance abuse disorder’, ‘schizophrenia’, ‘eating disorder’, ‘conduct disorder’, and ‘personality disorder’. These search terms deviated in two ways from Cosci and Fava’s (11) original search terms. First, we chose to include additional categories of mental disorders for which a potentially progressive course may be assumed, i.e., personality and conduct disorders. Second, we wanted to account for changes in the transition to DSM-5 and therefore performed an additional search including the search terms ‘obsessive compulsive disorders’ and ‘posttraumatic stress disorder’. In the Supplementary Material we reported the search strategy.

The searches in the databases were conducted by one reviewer (S.Cl.) and references were exported to Endnote (20). After removal of duplicates in Endnote (21), the remaining papers were exported to Rayyan (22). The last duplicates were removed by hand in Rayyan. Papers were screened by four independent reviewers (S.Cl., N.S., S.Cr., L.P.). Given the high number of papers retrieved during this procedure, we chose to first assess interrater reliability of eligibility ratings. Two pairs were made (S.Cl./N.S. and S.Cr/L.P) and both pairs of reviewers independently rated 100 papers based upon title, abstract and key words. As interrater reliability was excellent for both pairs (k = 0.96 to 1.00) (23), reflecting (almost) perfect agreement between both screeners, all references were divided and screened independently by the four reviewers. In case of doubt, a reviewer could consult the other reviewer of the pair to decide upon eligibility. Disagreements were solved by consensus (24). If there still was doubt about inclusion of the paper for the full text round (round 2), inclusion was discussed by all authors to find a consensus. In round 2, all possible eligible papers in the full texts round were screened by two independent researchers. We used the same procedure in case of disagreement as in round 1.

2.3 Data extraction

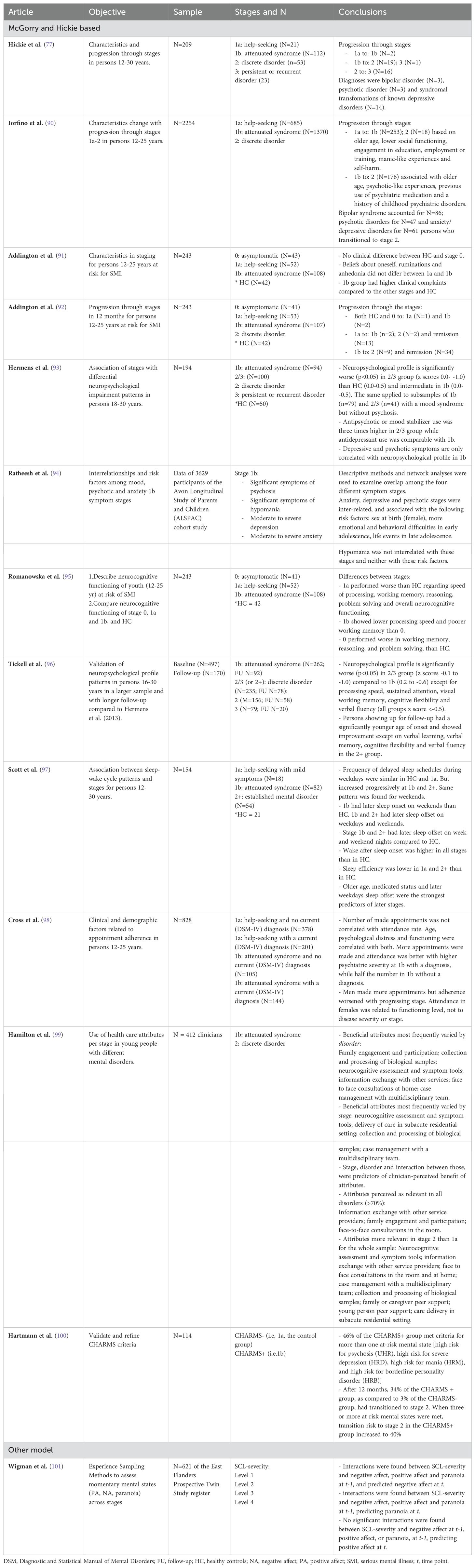

The first data extraction was performed on 23/08/2022. Data were extracted from the papers in two different ways. Firstly, a summary of findings was reported in a pre-designed table including the headings ‘objective’, ‘sample’, ‘stages and N’, and ‘conclusions’. This was done by N.S. and S.Cl. and supervised by H.V. Secondly, preliminary drafts were written for the result section according to a pre-designed format, including ‘full or partial staging model’, ‘reason for inclusion (criterion a, b, or c)’ and ‘main findings’. The various disorder sections were divided between N.S. and S.Cl. They composed summaries for each disorder section with assistance from L.P. and B.B. Each summary was supervised by one of the senior researchers (H.V., A.V., S.v.A., J.H., L.D.). Further details (objective, sample, stages and N and conclusions) of the included studies were reported in Tables 1–9.

2.4 Data analysis

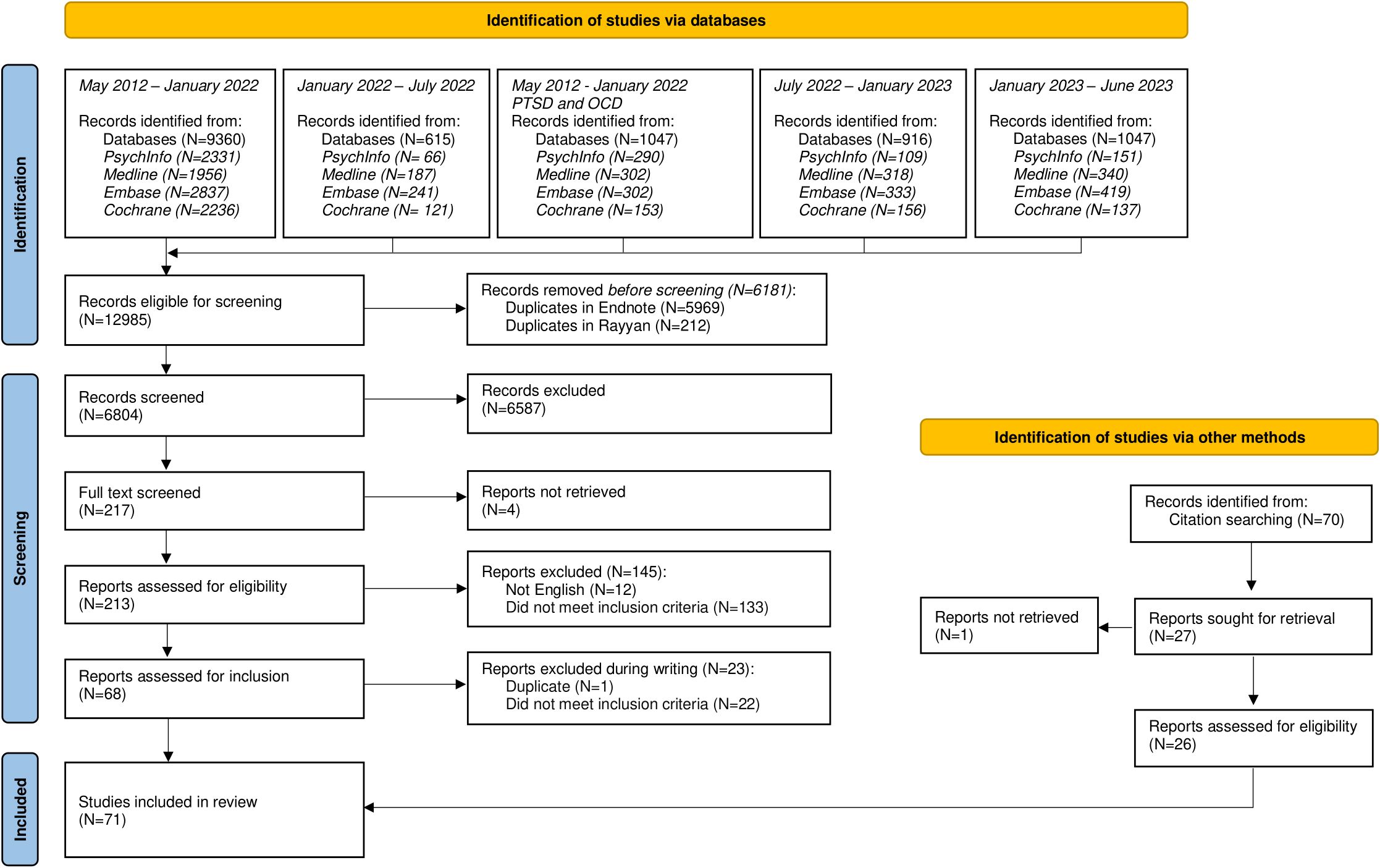

The selection procedures and resulting outcomes are presented in a PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1). In line with procedures described for data extraction, we used the extracted data to summarize findings for each category of mental disorders. Data are presented in a table that summarizes key findings from the selected studies. In addition, brief text summaries describe the number of studies, their reasons for inclusion (i.e. whether they met inclusion criterion a, b, or c), whether the studies related to an existing staging model, the study objective, and a summary of findings.

3 Results

3.1 Selection of papers and study characteristics

Our search revealed 12985 papers. After removing duplicates, 6804 papers were screened on titles, abstracts, and keywords. Of these, 217 papers were subject to full text screening, of which 45 papers were included. Inspection of the reference lists of these 45 papers revealed another 26 papers that met inclusion criteria. The PRISMA flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

3.2 Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders

Twenty-one papers met our inclusion criteria for schizophrenia or related psychotic disorders. One paper was included because of a theoretical focus on staging (‘category a’ see full definition in method section), seventeen papers focused on clinical characteristics of different stages (‘category b’) and three papers comprised interventions for one or several stages of a staging model (‘category c’). An overview of papers with a summary of aims and conclusions can be found in Table 1.

Ten papers referred to McGorry and colleagues’ (4–6) model or to an adaptation of this model. Armando and colleagues (25) proposed an extension of McGorry’s model, by including associated impairments in social functioning in the formulation of stages. In addition, they described several stage-appropriate adaptations, based upon mentalization-based treatment. Eight papers investigated clinical features related to McGorry’s staging model. Berendsen et al. (26) supported construct validity by demonstrating worse affective, catatonic, and negative clinical markers in later stages. Although their paper revealed no difference in treatment response between stages, they found that duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was associated with more symptomatology both at baseline and at two-year follow-up. In a follow-up paper, they proposed subdividing stage 2 in less (2a) versus more (2b) than one year of DUP, which was supported by their finding that negative symptoms were more severe in stage 2b than in stage 2a (27). In a subsequent paper, working memory and processing speed as measures of cognitive performance were found to be lower in later stages at baseline, however this was not the case anymore at 3 and 6 years of follow-up (28). Godin et al. (29) studied stage stability and validated their model by using number of episodes, daily functioning, and total scores on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). A subdivision of stages 2 and 3 based upon mood and cognition was proposed by data-driven cluster analyses. Kommescher et al. (30) found more maladaptive coping styles in high-risk populations (stage 0-1) and in stage 4. Li et al. (31) focused on stability of Psychotic disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PNOS) and suggested a subdivision of stage 2 in first episode PNOS (2a) or schizophrenia (2b). Another validation paper (32) yielded significant differences in the factor structure of the PANSS between stages independent of age of onset and duration of the illness, indicating staging may serve as an appropriate model to deal with the clinical heterogeneity of schizophrenia. Peralta et al. (33) focused on stages from the first psychotic episode onwards and made alterations to the McGorry model based on stability and progression of non-remitting illness. Validation of this adjusted model followed mainly from differences between stage 2 and 3A and addressed the factors involved in full versus incomplete remission. Finally, one paper investigated stage-tailored interventions referring to McGorry’s model. Ruiz-Oriondo et al. (34) found that combining integrated psychological therapy (IPT) with emotional management therapy (EMT) improved clinical symptoms, cognitive performance, social outcome, and quality of life in stage 4.

The remaining eleven papers departed from other staging models than McGorry’s. Nine papers studied correlates of stages and two articles [i.e., Rapado-Castro et al. (35), and Falkai et al. (36)] studied a corresponding intervention. Duration of illness was used in a paper by Bagney et al. (37) to define treatment groups and to study executive functioning related to negative symptoms. Rapado-Castro et al. (35) found a significant interaction between duration of illness and response to N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) for positive symptoms and functional variables, but not for negative or general symptoms. Specifically, this mediator effect for DUP in response to treatment was more evident in subjects with 20 years or more DUP, suggesting a potential advantage of adjunctive NAC on positive symptoms in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Ortiz et al. (38) used the four-stage model proposed by Cosci and Fava (11) to study clinical and psychopathological differences. Sauvé et al. (39) also used a four-stage model to study negative symptoms by categorising data from 47 studies on point prevalence. Carrion et al. (40) described and clinically validated a partial four-stage model that focused on the prodromal phases of psychosis as well as on conversion rates between stages. Dragioti et al. (41) developed and described a clinical staging approach using the PANSS pyramidal model and arbitrarily chose stages based on age groups and gender, as duration of illness was not available. Fountoulakis et al. (42) used duration of illness as the primary factor to describe stages and plotted illness duration against PANSS, factors resulting in four major stages (43). Positive symptoms were dominant in the first three years, excitement and hostility in the period between 3 and 12 years, depression and anxiety after 12 years, and neurocognitive impairment after 25 years. Negative symptoms were found to be mostly stable during all stages, with a mild increase from after 18 years onwards. Fountoulakis et al. (44) also studied the role of gender, age at onset (four groups) and duration of illness (seven groups) on the course of schizophrenia. They found a later onset and more benign course of the disorder for females, a relation between early onset and slower progression of the disorder for both sexes, while they did not find an effect of the disorder duration. Falkai et al. (36) used an early (<5 years illness duration) and late (≥ 15 years) stage to study the use of cariprazine versus placebo. Cariprazine was found to be more effective than placebo in both stages with a larger treatment response in the early stage. Lastly, Fusar-poli et al. (45) conducted a qualitative paper, with input from patient experts, and themes were discussed between patients, family members and professionals to design enriched stages, improving their validity, based upon the lived experience of patients.

3.3 Bipolar and related disorders

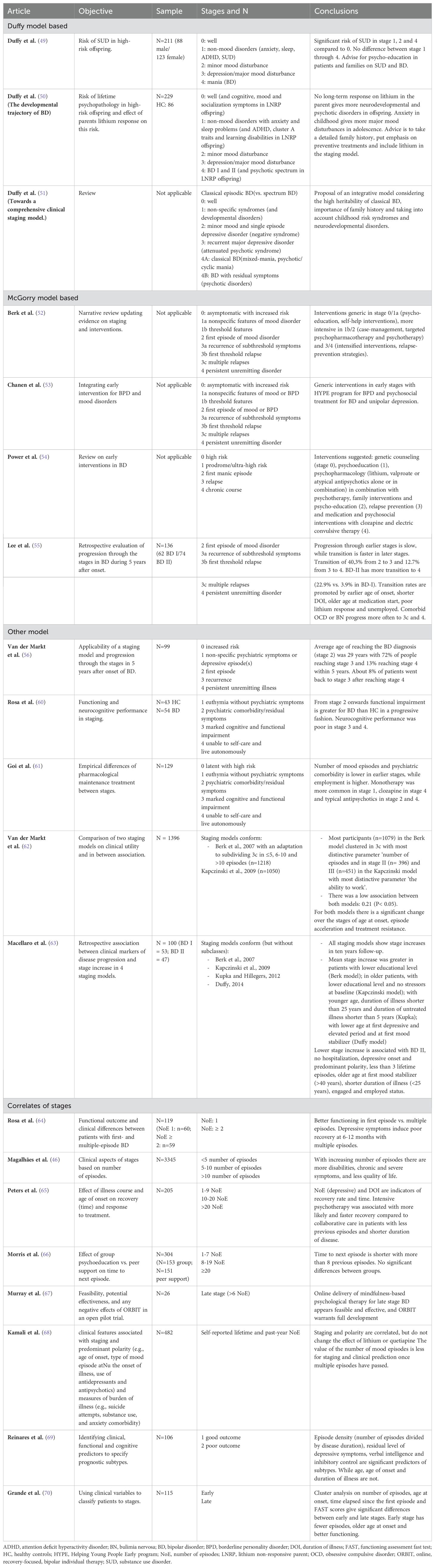

Twenty papers met inclusion criteria for bipolar and related disorders. Four papers presented theoretical proposals for a staging model, ten papers described clinical features of stages, five papers studied stage-related treatments and one paper (46) studied both clinical features and a stage-related intervention. Four different staging models, or adaptations, and associated interventions were mentioned, and eight papers used correlates of stages. See Table 2.

Two studies focused upon clinical characteristics, based on a previously proposed clinical staging model of Duffy and colleagues (47, 48). The first study found that, regardless of bipolar parent substance abuse, offspring in stage 1, 2 and 4 were likely to develop substance use disorder compared to stage 0, while no further significant differences were found between stages 1 to 4 (49). The second study found that offspring of one parent diagnosed with bipolar disorder with no long-term response to lithium were more likely to develop psychotic and neurodevelopmental disorders compared to offspring with a lithium responding parent. Therefore, they advised including parents’ response to lithium in the staging model (50). A subsequent conceptual paper distinguished between classic episodic and spectrum bipolar disorder within the staging model and underlined the high heritability of the disorder and the need for a thorough family history assessment to add context to early (otherwise nonspecific) risk syndromes (51).

Berk et al. (52) described an adaptation of McGorry’s staging model of psychotic and severe mood disorders (4) for bipolar disorder, which was also used by Chanen et al. (53) in a combined model for borderline personality disorder (BPD), unipolar depression and bipolar disorder given their common underlying risk factors, age of onset, co-occurrence and overlapping core symptoms (see personality disorders, below). The same model was then slightly simplified, and interventions tailored to each stage were proposed (54). A third paper used the model of Berk et al. (52) to study clinical features. Illness progression was monitored during five years after onset of bipolar I or II disorder with slower progression through the earlier stages and faster transition in the later stages (55).

Van der Markt et al. (56) refined a combined model based on the staging models of Berk et al. (57), Kupka and Hillegers (58) and Duffy et al. (51). Retrospective life charts were used to study progression through stages in the five years after onset of bipolar disorder (stage 2) with the majority reaching stage 3 and a smaller amount reaching stage 4. Two papers referred to the staging model described by Kapczinski et al. (59). Rosa et al. (60) evaluated functional and neurocognitive performance across stages and found a progressive impairment in functioning along the stages with neurocognitive decline in the later stages. Goi et al. (61) studied patterns of pharmacological treatment with more functional impairment when more medication was used from the second stage onward. Two papers compared different staging models with each other. Van der Markt et al. (62) compared the models of Berk et al. (57) and Kapczinski et al. (59) and found a low association suggesting the models act complementary. Furthermore, they suggested using ‘dispersion over the stages’ to assess the clinical utility of a model. Macellaro et al. (63) also compared these models with the models of Kupka and Hillegers (58) and Duffy (51) and retrospectively found stage progression in all four models during a ten year period. Results showed that an increased number of mood episodes worsened severity of next episodes and reduced treatment response.

Finally, several papers discussed correlates of stages for bipolar disorder. Most studies used ‘number of episodes’ as a proxy to define stages. One study (64) studied functional outcomes in patients with only one versus more (depressive, manic, or mixed) episodes. First episode patients were younger and more autonomous, had less cognitive complaints and better work performance, and were better able to enjoy spare time and their companions. Magalhães et al. (46) observed more severe symptoms and a lesser quality of life after more episodes had passed. In a subset of (chronic) patients, antidepressant use was evaluated with no significant difference between subgroups.

Four papers studied differential effects of interventions for bipolar disorder. Peters et al. (65) found that intensive psychotherapy was associated with more likely and faster recovery compared to collaborative care in patients with less previous episodes and shorter duration of disease (i.e., earlier stage). Similarly, Morris et al. (66) noted more beneficial treatment effects for structured group psychoeducation compared to optimized unstructured group support in patients with fewer episodes. Murray et al. (67) defined the late stage as more than six episodes and found that online mindfulness therapy improved quality of life. This contrasts with findings of Kamali et al. (68) who found that self-reported number of lifetime and past-year mood episodes predicted neither the effects of lithium nor quetiapine. However, illness duration was on average more than 23 years and number of episodes high. Reinares and colleagues (69) proposed still another partial staging model of remitted patients and used latent class analysis to find a two-class model fitting the data best. Classification in ‘good’ or ‘poor’ outcome stages was based on functional outcome with episode density (number of episodes divided by disorder duration), residual level of depressive symptoms, estimated verbal intelligence and inhibitory control as strongest predictors. Grande et al. (70) used cluster analysis on several clinical variables (number of episodes, age of onset, time since first episode and functioning) to divide their study population in an early and late stage with the first functioning better, having a later age of onset and fewer episodes.

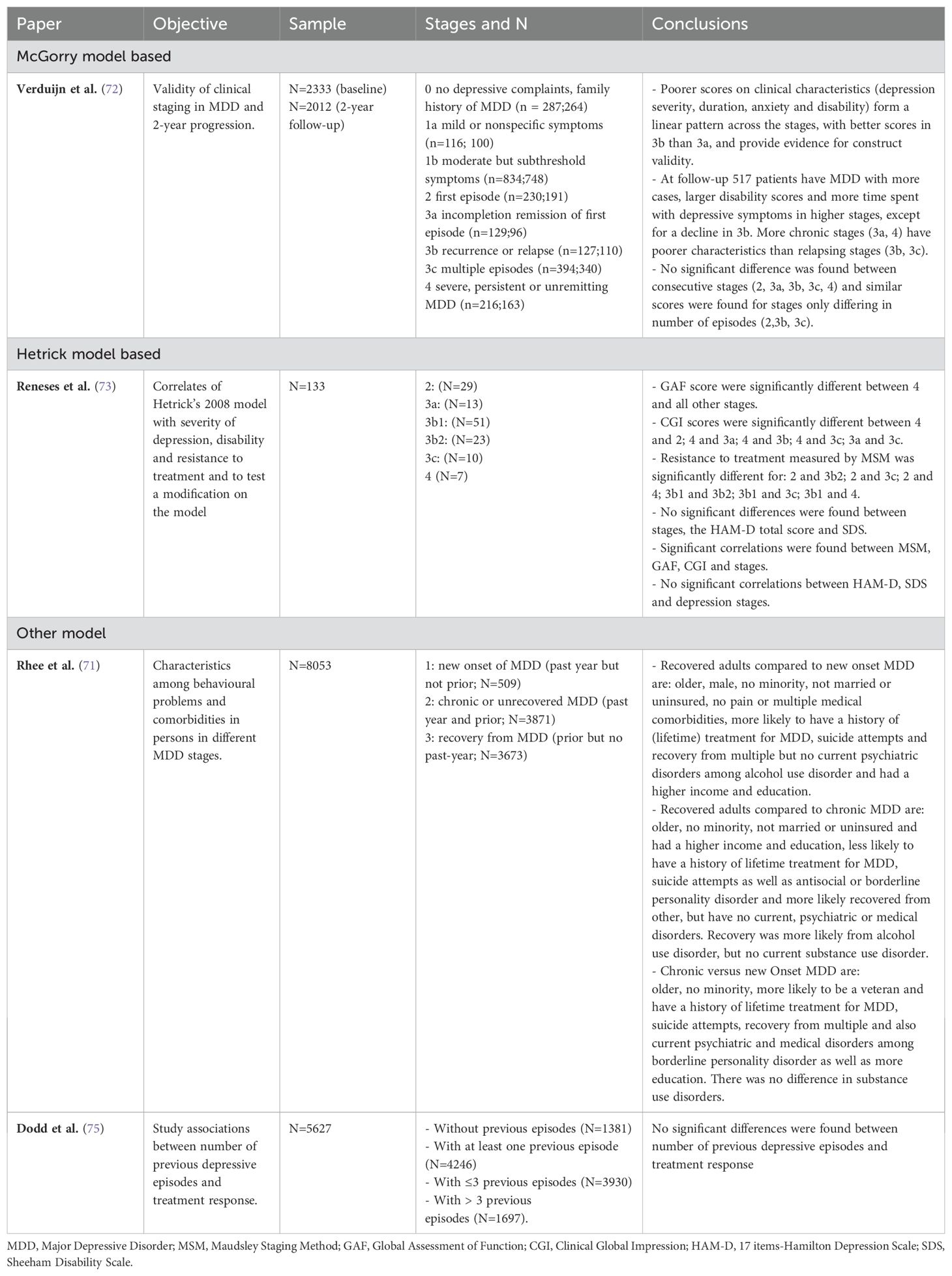

3.4 Depressive disorders

Our search revealed one newly proposed staging model including a study on clinical correlates, two papers on clinical correlates of existing staging models and one stage-related treatment paper. A more extensive description of findings can be found in Table 3.

Rhee and colleagues (71) proposed and studied a staging model for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) with three stages, namely stage 1 ‘new onset of MDD’ (past-year but not prior MDD), stage 2 ‘chronic or unrecovered MDD’ (past-year and prior MDD) and stage 3 ‘recovery from MDD’ (prior but no past-year MDD). Verduijn and colleagues (72) studied the construct and predictive validity of a clinical staging model for MDD, as proposed by McGorry and colleagues (4), consisting of different stages (0, 1A, 1B, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C, 4) based on the severity and duration of symptoms and the number of episodes. At 2-year follow-up, most of the clinical characteristics, such as severity and duration of symptoms and disability, worsened across the stages. Reneses and colleagues (73) modified Hetrick and colleagues’ model (74), by separating those with “recurrence from a previous depressive episode that was stabilized with a complete remission” into stage 3b1. They found that ‘treatment resistance’ – operationalized using the Maudsley Staging Model based upon a) disease episode duration, b) symptom severity and c) treatment failures – distinguished best between clinical stages and they argued that this variable differentiates best the stages in Hetrick and colleagues’ (74) model. Finally, a study by Dodd and colleagues (75) found no significant differences between the number of previous depressive episodes and treatment response.

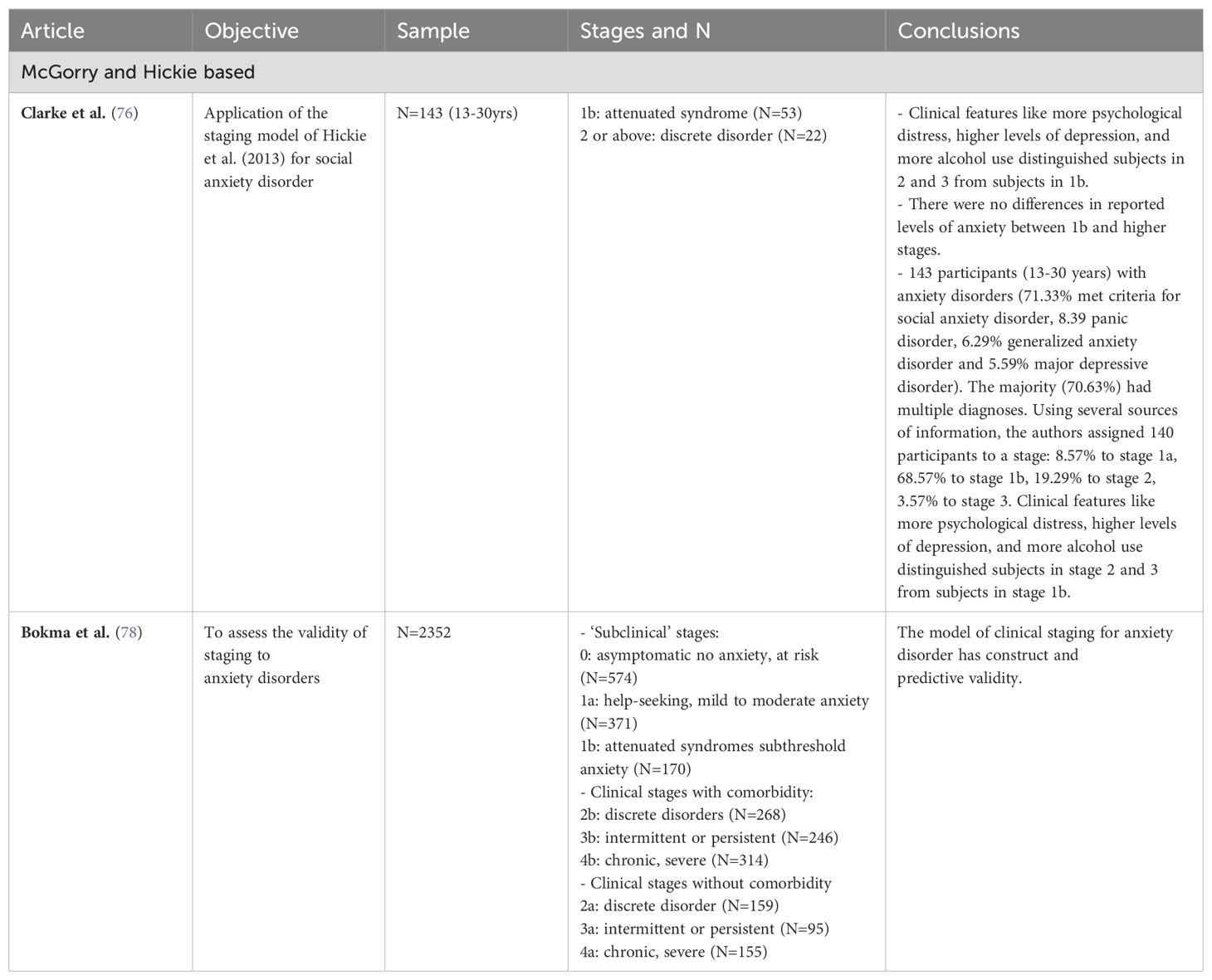

3.5 Anxiety disorders

The two papers identified refer to clinical correlates (see Table 4). Clarke and colleagues (76) used Hickie and colleagues’ (77) (see below) transdiagnostic model to classify participants according to the stage of their anxiety disorder. They found that clinical features, such as greater psychological distress, higher levels of depression, and more alcohol use distinguished participants in stages 2 and 3 from participants in stage 1b. There were no differences in reported levels of anxiety between stage 1b and the higher stages. Bokma and colleagues (78) adapted Hickie and colleagues’ (77) and McGorry and colleagues’ (4) models, differentiating between ‘subclinical’ stages (0, 1a, 1b), clinical stages with comorbidity (2b, 3b, 4b) and without (2a, 3a, 4a) comorbidity. Linear trends were found with severity of anxiety, depression and disability increasing in the later stages.

3.6 Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders

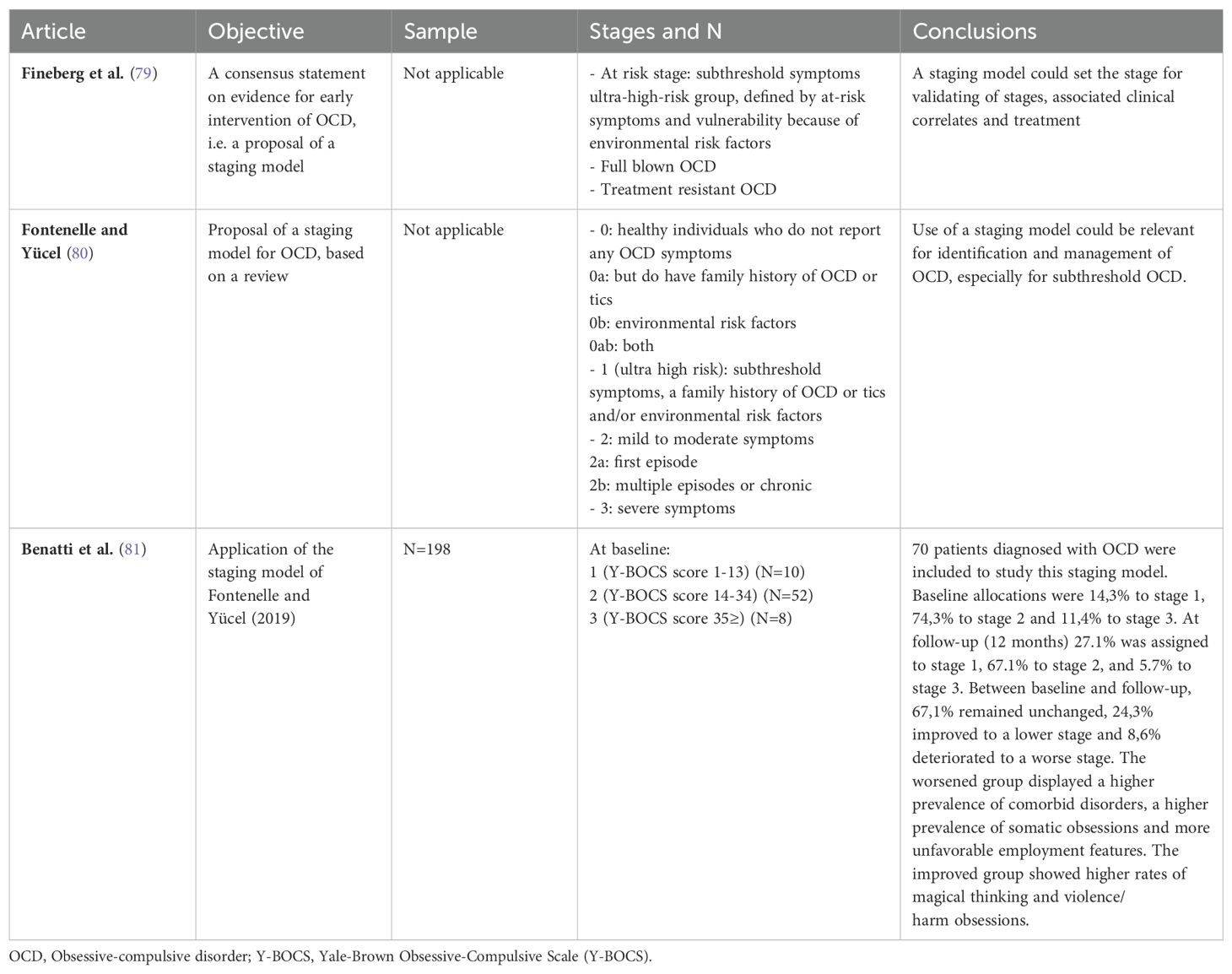

Our search found two conceptual proposals and one study of clinical correlates (see Table 5). Fineberg and colleagues (79) proposed a partial staging model, starting with subthreshold symptoms that may represent the first at-risk stage for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), for which they suggest psychoeducation for parents on not accommodating of the obsessive-compulsive symptoms. They additionally proposed an ultra-high-risk group, defined by at-risk symptoms and vulnerability because of environmental risk factors. The next stage includes patients who do meet the syndromal threshold for OCD, for which they recommend cognitive behavior therapy and medication (SSRI). Finally, they describe later stages as consisting of patients who appear to be resistant to treatment.

Fontenelle and Yücel (80) proposed a staging model for OCD, based upon a review, considering clinical markers, potential biomarkers, and outcome characteristics. They proposed stage 0, 0a, 0b, 0ab, 1, 2, 2a, 2b and 3. The authors identify different types of symptoms, levels of family accommodation, and comorbidity for these stages and they also propose different treatment strategies. This model was studied by Benatti and colleagues (81) in a follow-up study. About two-thirds remained unchanged. The worsened group displayed a higher prevalence of comorbid disorders, a higher prevalence of somatic obsessions and more unfavorable employment features. The improved group showed higher rates of magical thinking and violence/harm obsessions.

3.7 Trauma and stressor-related disorders

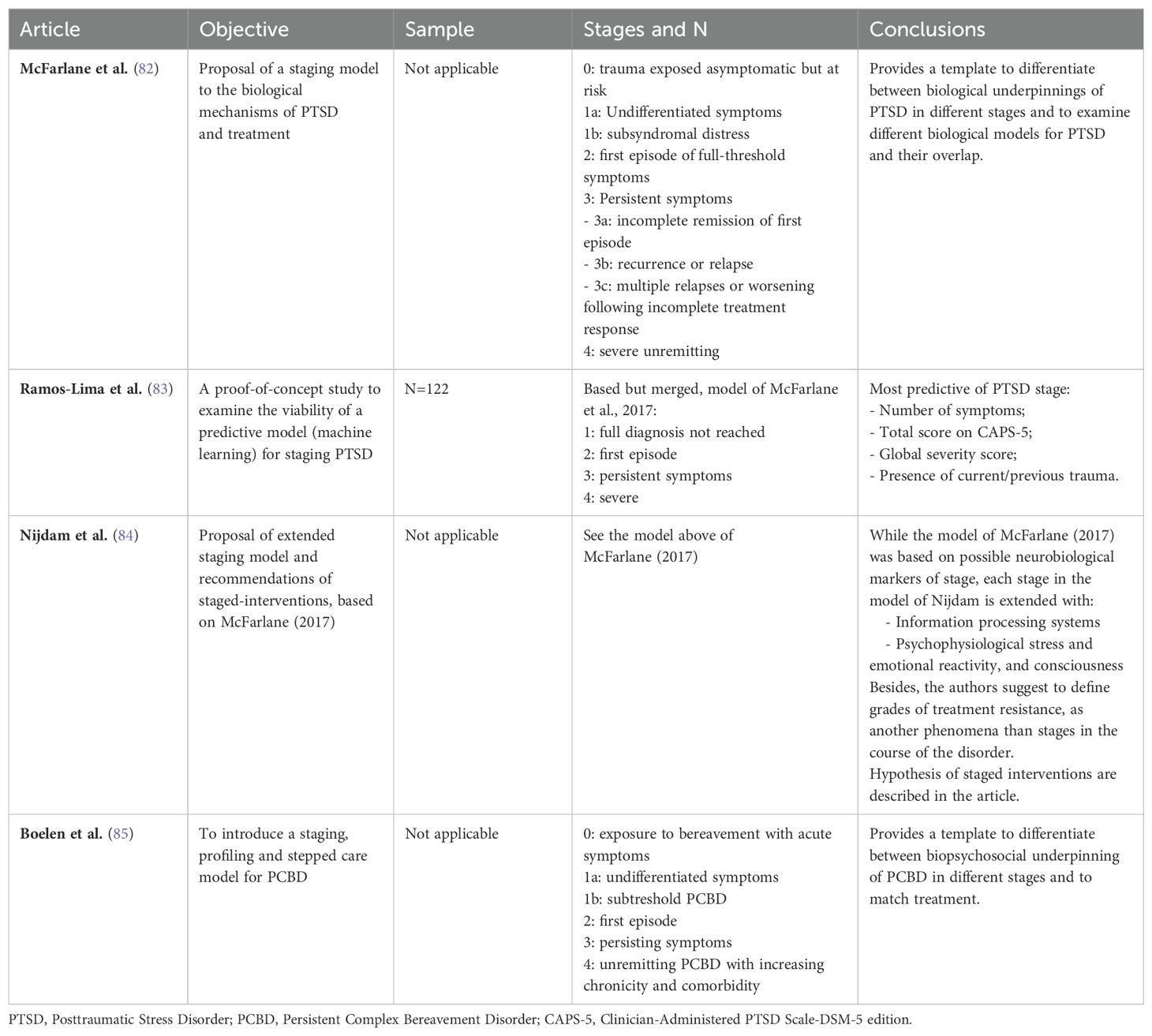

Three conceptual papers and one study of correlates (see Table 6) were identified. McFarlane and colleagues (82) distinguished between five stages of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Their model describes a range of possible neurobiological changes associated with different stages and they stress how these biological processes may also affect the immune system and underpin somatic comorbidities. A proof-of-concept study used machine-learning techniques to predict stage assignment, based upon McFarlane’s staging model (83). The authors found that number of symptoms, the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale-DSM-5 edition (CAPS-5) total score, global severity score, and presence of current/previous trauma were most predictive of PTSD stage. Nijdam et al. (84) proposed to extend McFarlane’s model with information processing systems and psychophysiological stress and emotional reactivity, and consciousness. The authors proposed interventions for each stage of the disorder based upon their extended approach. The search also retrieved a hypothetical staging model for persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD) following the loss of a loved one in traumatic circumstances (85), to inform treatment decisions.

3.8 Feeding and eating disorders

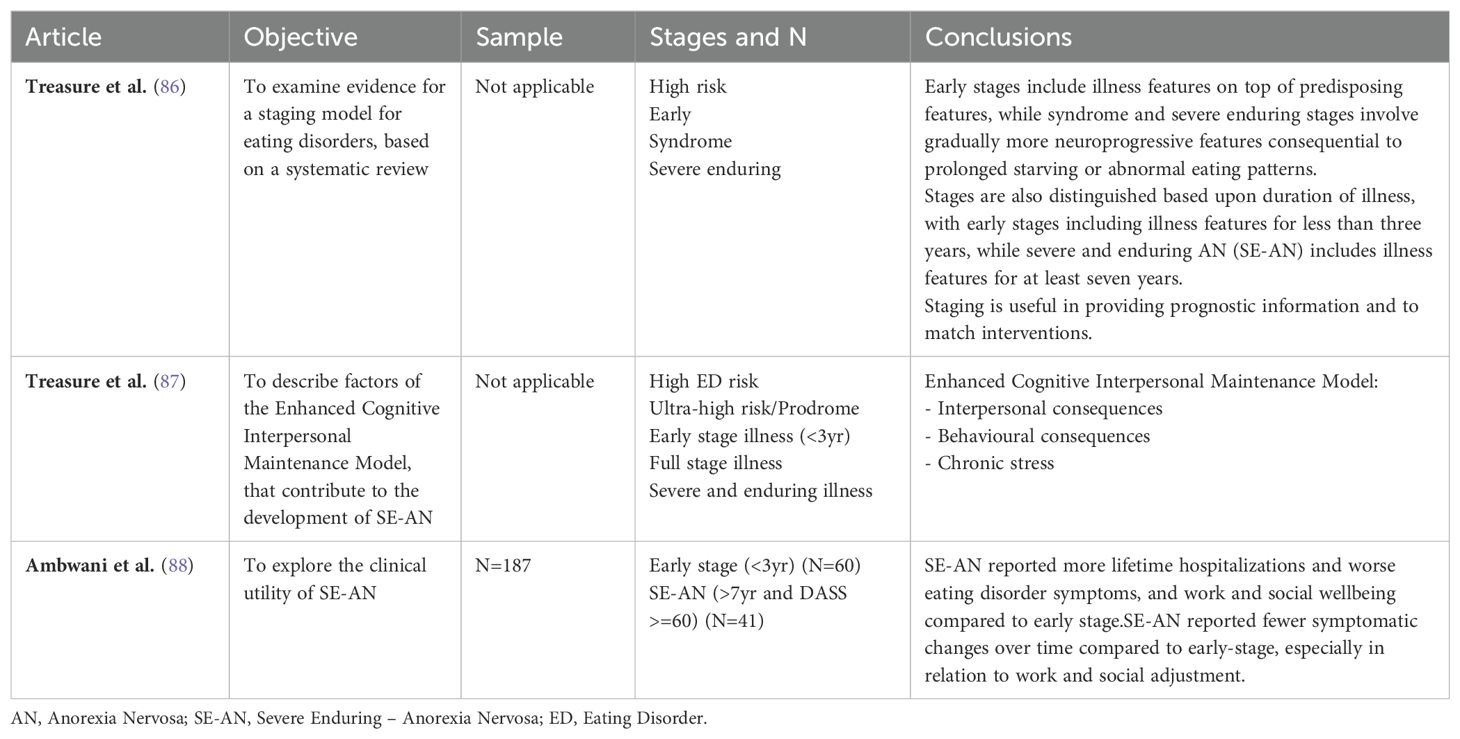

Three papers on staging models for feeding and eating disorders were identified, two conceptual papers and a study of clinical correlates (see Table 7). Treasure et al. (86) proposed a staging model, based upon a systematic review, distinguishing between four stages (high risk, early, syndrome, severe enduring). They focused on the progression of anorexia nervosa (AN), as few data were found to support staging models for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorders. Stages for AN were largely based upon the presence of predisposing features, illness features and neuroprogressive features, and duration of illness. The authors propose different interventions with so-called ‘psychoprotective’ (cognitive dissonance strategies and social media literacy) and ‘neuro-protective’ (promoting healthy eating and physical activity) interventions for the high-risk stage, and family support and family-based therapy for the early stage. A slightly modified version of the same model was included in Treasure et al. (87), differentiating ‘high risk’ in a ‘high risk’ and an ‘ultra-high risk/prodrome stage’. The authors explore different interventions for the severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SE-AN) stage, based upon a maintenance model including interpersonal consequences, behavioral consequences, and reactions to chronic stress. Their suggestions include caregiver skill training, habit reversal therapy, exposure techniques, neuromodulation, and pharmacotherapy. The clinical utility of a concept of SE-AN was further explored in an outpatient service (88). Results highlighted different courses and service use associated with different stages of AN.

3.9 Disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders

No papers were found for staging models in conduct disorders.

3.10 Substance-related and addictive disorders

No staging models were found for substance use disorders.

3.11 Personality disorders

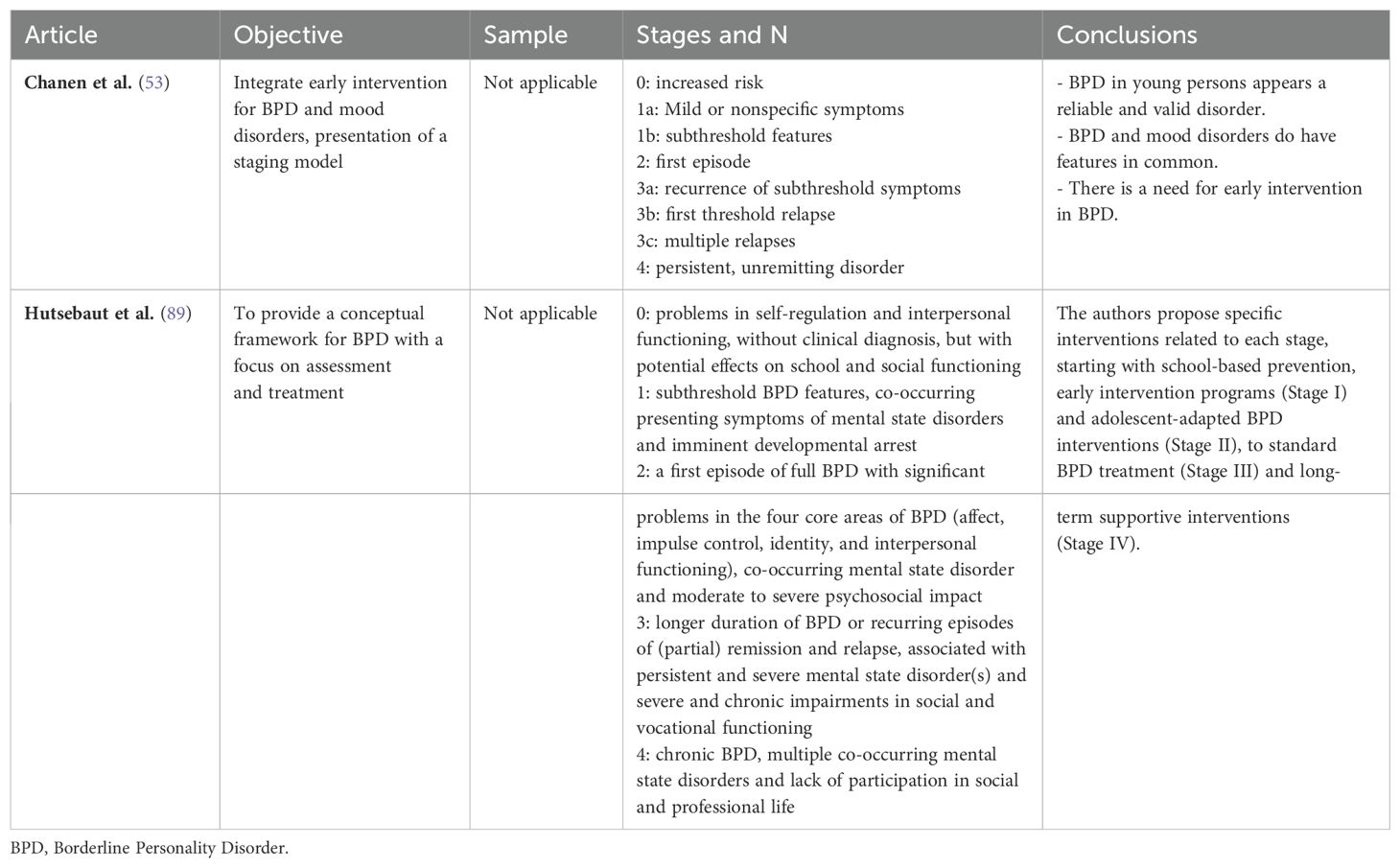

Two conceptual papers on staging models were found for borderline personality disorder (BPD) (see Table 8). Chanen et al. (53) (2016) presented a combined model for BPD and mood disorder, based upon their similar age of onset, common risk factors, frequent co-occurrence and overlapping clinical phenomenology. This model further outlines a mental health care response to each stage. Interventions are more generic and simpler at stage 0 and 1a and become more specialist and intensive at stages 1b and 2, and further on. A second staging model for BPD has been proposed by Hutsebaut et al. (89). Their model uses features of BPD, co-occurring psychopathology, and psychosocial disability as criteria to distinguish between five stages.

3.12 Transdiagnostic staging models

The thirteen included papers all studied clinical correlates and are outlined in Table 9. Twelve papers used Hickie and colleagues’ (77) transdiagnostic staging model. In a study of young people seeking mental health care, assignment to stages was reliable and at follow-up 11%, 19%, and 33% of respective stages 1a, 1b, and 2 progressed to a later stage. In a large-scale longitudinal observational study, Iorfino and colleagues (90) investigated the transition rates from a help-seeking stage and an attenuated syndrome stage to a discrete disorder stage in patients with anxiety, mood, and psychotic disorders. Stage progression from the help-seeking stage was associated with older age, self-harm, manic-like experiences and lower social functioning, and engagement in education, employment, or training. Progression from the attenuated syndrome stage was associated with older age, psychotic-like experiences, previous use of psychiatric medication and a history of childhood psychiatric disorders. Addington and colleagues (91, 92) followed youth with emerging severe mental illness (SMI), assigned to similar stages. Of the help-seeking participants, 50% remained symptomatic, and 7.5% moved to the next stage or developed a SMI. Of the attenuated syndrome participants, 9% developed a SMI and one-third had symptom remission within 12 months. Hermens and colleagues (93) used the same staging model in a sample of young people seeking mental health care for psychotic and/or depressive symptoms. They found that the discrete disorder group displayed the most impaired neuropsychological profile (i.e., problems in memory and executive functioning), compared with the attenuated syndrome group, with a healthy control group being least impaired. To further inform empirical research in transdiagnostic staging, Ratheesh et al. (94) explored interrelationships and risk factors among mood, psychotic and anxiety 1b symptom stages. Anxiety, depressive and psychotic stages were found to be inter-related and associated with the following risk factors: sex at birth (female), more emotional and behavioral difficulties in early adolescence, and life events in late adolescence. Hypomania was not interrelated with these stages nor with these risk factors. Based on these findings, the authors suggested that anxiety, psychotic and depressive symptoms could form a combined transdiagnostic stage in their studied cohort.

Two papers investigated neuropsychological functioning across stages. Romanowska and colleagues (95) reported that participants in the help-seeking stage 1a performed worse than healthy controls on measures of speed of processing, working memory, reasoning, problem solving and overall neurocognitive functioning. Participants in the attenuated syndrome stage 1b showed lower processing speed and poorer working memory than participants in the asymptomatic stage 0. Participants in stage 0 performed worse than healthy controls in working memory, reasoning, and problem solving. Tickell and colleagues (96) found differences in verbal learning, verbal memory, visual memory and set shifting between stage 1b and 2+. Both groups showed similar improvement in neuropsychological functioning at follow-up.

In a study of disturbed sleep-wake cycle patterns, Scott and colleagues (97) found that help-seeking young people experienced more wake time after sleep onset, compared with healthy young people. Participants in the mild symptom and established disorder stages had lower sleep efficiency, compared with healthy young people. Delayed sleep increased across stages. Cross and colleagues (98) used the medical records of young people to assign them to one of four groups: stage 1a lacking a current (DSM-IV) diagnosis, stage 1a with a current diagnosis, stage 1b lacking a current diagnosis, or stage 1b with a current diagnosis. Age, gender, severity of illness, functioning and psychological distress had differential associations with both planned treatment intensity and attendance rates.

One paper used an online survey method to identify perceived utility of a wide range of attributes of mental health care for different disorders in the attenuated syndrome and discrete disorder stages (99). Hartmann et al. (100) introduced CHARMS (Clinical High At Risk Mental State), a pluripotent, at-risk mental state concept. CHARMS criteria are proposed as an extension of UHR (Ultra High Risk) criteria, extending these to psychosis (UHR), high risk for severe depression (HRD), high risk for mania (HRM) and high risk for BPD (HRB).

Finally, Wigman and colleagues (101) used experience sampling methods in a sample of women, 95% twins, to study the reciprocal impact of momentary mental states (positive affect, negative affect, and paranoia) over time across different stages of severity of psychopathology; staging was operationalized across four levels of increasing severity of psychopathology, based on the total score of the Symptom Checklist. They found that more severe stages were characterized by stronger connections and more variable connections between mental states. Moreover, severe stages indicated more individual-specific associations between mental states over time. These results suggest that, as individuals move through progressive stages, the dynamics between different mental states become increasingly stronger (referring to the nomothetic concept of staging), and the differences between individuals become progressively larger (referring to the idiographic concept of profiling).

4 Discussion

The current systematic review aimed to provide an overview of the past decade of clinical staging models for potentially progressive mental disorders included in DSM-5. Our second aim was to review empirical studies of the reliability, validity, and clinical utility of staging models published over this period. Our search identified 71 papers, with 13 newly proposed staging models or extensions on earlier staging models. We identified 58 empirical papers, 47 of which focused upon validating staging models by studying clinical correlates. Nine papers investigated treatment interventions based upon a model of staging. Two of the 58 empirical papers had several aims (studying correlates and interventions or proposing a staging model and studying correlates of the proposed model). One of the 71 papers focused on a newly proposed staging model combined for bipolar disorder and mood disorder (53) and is therefore described under both bipolar disorder and personality disorders. By far most papers were found for schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders (21 papers), and bipolar and related disorders (20), while other categories of mental disorders were much less represented: depressive disorders (4), anxiety disorders (2), obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (3), trauma and stressor-related disorders (4), feeding and eating disorders (3) and personality disorders (2). In addition, 13 papers used a transdiagnostic model. No papers were identified for disruptive, impulse-control and conduct disorders, or for substance-related and addictive disorders. Compared with the original Cosci and Fava review (that included 78 papers), fewer papers met the inclusion criteria for the current review. However, it is noteworthy that the current review excluded certain types of papers that were included in Cosci and Fava’s review. For example, papers referring to ‘stages of change’ in the treatment of substance use (SUD) or eating disorders were not included in the current review, as we conceived these ‘stages’ not as reflective of disorder progression. The current review identified no papers on SUD and only three on eating disorders that met the inclusion criteria.

The results of our search suggest that the field has been producing consistent outputs but that it is not growing rapidly. The review also shows some evolution in the field over the last decade. While models for psychotic and bipolar disorders still dominate the field, the current review identified additional staging models for specific syndromes, including obsessive-compulsive, trauma and stressor-related, and personality disorders, along with several papers using a transdiagnostic approach to staging.

Our first aim was to summarize new conceptual models of staging in psychiatry. Staging models were primarily developed to better capture the dynamic nature of the trajectories of psychopathology and the emergence of mental disorder syndromes over time, complementing the cross-sectional nature of traditional psychiatric classifications (2). Conceptually, most staging models share a similar design, resembling the disease staging of their medical counterparts. Most models consider individual disorders and use DSM-5 criteria to distinguish between stages: stage 1 is usually defined in terms of subthreshold diagnosis, while the demarcation with stage 2 is usually based upon a transition from subthreshold to full DSM-5 syndrome diagnosis. Similarly, transition to stage 3 is usually determined by recurrence, i.e., a new acute episode of the disorder. However, it is questionable whether this ‘disease-based’ approach, rooted in psychopathology, fits adequately with the typical heterogeneity of mental health issues and the unpredictable course of many mental disorders (102). This raises several issues.

Firstly, many DSM-5 diagnostic thresholds are arbitrary (103) and it’s questionable whether diagnostic criteria will ultimately enable valid distinctions between stages. Staging approaches fit better with diseases of which the underlying psychopathology is fully understood, including clear biomarkers for disease onset and progression (104). This is clearly not the case for mental disorders, limiting the validity of a disease-approach. In addition, unlike untreated physical illness which often progresses in a predictable way, mental disorders are often characterized by multifinality, and course and outcomes are more difficult to predict (105). Secondly, many severe mental disorders, including psychotic and personality disorders, might be characterized by unstable symptomatic episodes, that are accompanied by longstanding psychosocial consequences (106). Typically, psychosocial disability is considered to occur in parallel with, or be a consequence of, mental disorder. Arguably, for some conditions, especially personality disorder, psychosocial disability could be the source of the disorder (107), while for others, disability might precede disorder. Overall, some disabilities are more intrinsically interwoven with mental impairments, in contrast to psychosocial disabilities arising as outcomes of somatic medical conditions. Moreover, many severe mental disorders are characterized by a ‘symptom-disability gap’, in which psychopathological symptoms fade away, while psychosocial disability might be more persistent and influential upon the longer-term outcome of mental disorders (108). Two recent conceptual models include psychosocial disability to define distinction between stages, thereby deviating from a purely psychopathological approach (25, 89). Both models include psychosocial disability as a marker of more enduring stages of mental illness. Thirdly, nearly all staging models describe markers of psychopathology while ignoring areas of resilience that might mitigate the impact of a disorder. Indeed, especially in mental health, disorder progression might also be influenced by (lack of) domains of resilience and/or adaptive functioning (109, 110). Fourth, clinical staging highlights the importance of early detection and intervention and thus the relevance to identify symptoms and features that characterize a subclinical stage. A major issue given the heterogeneity of phenomena within this early stage, however, is to distinguish mild subclinical expressions of a disorder from early stages that may indeed progress into more severe manifestations. A key challenge therefore may be to identify symptoms that mark increased risk across different diagnostic categories with greater specificity. Finally, and probably most importantly, for disease staging to function as a prototype for clinical staging it must account for the heterotypic continuity of mental disorders (111) and heterogeneity among stages. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated that mental disorders are not fixed and independent entities but are highly correlated leading to differential expressions of psychopathology throughout the lifespan (112). For these reasons, models focusing upon single disorders are likely to be of limited explanatory value. Interestingly, despite our search terms being more likely to elicit disorder-specific staging models, we also retrieved several studies on transdiagnostic models. The number of trans-syndromal models required us to summarize these papers in a distinct and new category. This appears to reflect emerging recognition of the limitations of single disorder staging models and a shift toward the development of transdiagnostic or trans-syndromal models (113), exemplified by the first international consensus statement on transdiagnostic clinical staging in youth mental health (114). Such developments within the field of clinical staging align with a broader reconceptualization of psychopathology that stresses general dimensions or clusters of psychopathology as opposed to traditional nosologies, like the formulation of the p-factor (115), the emergence of HiTOP (116) and the revised alternative models of personality disorders (117). However, as opposed to these concepts, staging models emphasize more strongly the progressive nature of psychopathology. Still, in line with these developments, we contend that rather than rigidly adhering to single disorder models that are solely based in psychopathology, future development of clinical staging models will need to be more carefully tailored to incorporate evidence regarding the structure and development of psychopathology, along with other specific features of mental disorders that set them apart from their somatic counterparts. Staging models might also benefit from incorporating resilience and/or psychosocial functioning criteria that might be associated with (non-)progression. It remains to be seen whether these aims can be addressed while also achieving reliability and ease of use, which are crucial to clinical staging’s pragmatic aims.

Taking all these issues together, we believe that from a conceptual point of view, models of clinical staging may need to be tailored better to the complexities of mental disorders. Although it might affect their reliability and ease-of-use, it is worthwhile to consider whether staging models might benefit from considering more criteria related to resilience and/or psychosocial functioning that might be associated with (non-)progression.

Our second aim related to the empirical support for the validity and clinical utility of clinical staging in psychiatry. Our review found that the distinction between stages was validated in almost all reviewed papers, despite the abovementioned conceptual issues. These findings suggest that psychopathology can be approached as progressive with later stages being associated with increased severity, different symptom profiles, and more neurocognitive impairments across different studies. This underpins the notion that patients with late-stage disorders might indeed have different clinical needs, when compared with those with early-stage disorders. Importantly, outside the field of psychotic and bipolar disorders, empirical papers are largely lacking, suggesting that in most areas the focus is still on the conceptualization of models, with only initial efforts to validate them. Most papers investigated clinical correlates of different stages, while there were only ten publications in which treatment or intervention was based upon a staging model. Our search did not identify publications that explicitly investigated the clinical utility of clinical staging models, suggesting that these models have had only limited impact upon clinical practice. This might be due to the lack of a consensus about which model(s) to adopt in practice, along with the narrow scope of single syndrome models. If clinical staging models are to be used in routine clinical practice, there is a clear need for evidence supporting their direct utility. This requires more studies to establish the potential effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatment planning and interventions according to predetermined models of clinical staging. In the absence of sufficient studies demonstrating the clinical utility of models of clinical staging, their impact on clinical practice or on developing treatment guidelines can be expected to be rather limited.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

Notable strengths include using the same eligibility criteria as Cosci and Fava (11), allowing for comparison and identification of potential trends in publications about clinical staging. We also performed an a priori interrater reliability test, showing very high to almost perfect levels of agreement, to avoid differences among raters in selection of papers for eligibility. Our systematic review was also preregistered.

Limitations include introducing extra search terms referring to disorders for which we assumed a potentially lifelong progressive course, like personality and conduct disorder (that may progress into antisocial personality disorder). However, we did not include neurodevelopmental disorders in our search, such as autism spectrum disorder, and we excluded papers with a primary focus on neuroanatomy or biological markers. Furthermore, we chose to include extra search terms, i.e., PTSD and OCD, in a follow-up search to include categories of mental disorders that have been re-allocated into new individual categories in DSM-5. Although this inclusion was justified given by the transition to DSM-5, which occurred after the publication of Cosci and Fava’s review, this deviated from our preregistered search protocol. Furthermore, we deviated from Cosci and Fava’s (11)) eligibility criteria by excluding papers referring to stages of change in substance abuse and eating disorders. Also, we did not include papers referring to treatment-resistant depression, as we decided that such papers did not reflect the criterion of a partial or full staging model in our eligibility criteria. Finally, we did not perform any quality assessment of the designs used in the included studies in this review, which could be seen as a shortcoming. Although recommended, we believe the usefulness of such a quality assessment is limited given the aim of our systematic review to provide a broad overview of the current state of clinical staging and given the type of papers retrieved by the search. The results of our review revealed very heterogeneous studies, varying from RCT’s, cohort studies, longitudinal studies, mixed methods studies, survey studies and qualitative studies. Widely used tools for Risk of Bias analyses, such as Cochrane’s tool or ROBINS-I, are not suitable to report on the quality of heterogeneous studies. Therefore, we opted to merely describe findings, as a reflection of academic and clinical interest in staging. Consequently, no conclusions can be drawn about the quality of evidence derived from these studies. Our results should be interpreted largely as a reflection of efforts to validate staging models, rather than as justification of these models in and of themselves. reviews could rigorously assess the quality of evidence.

5 Conclusions

The current review demonstrates only a slow increase in interest in clinical staging as an alternative way of assessing the progressive course and severity of psychopathology. In addition, for most categories of mental disorders, staging models are still in a phase of conceptualization and initial validation. There is a general lack of (new) evidence supporting the clinical utility of clinical staging. Current models will need to be better tailored to the complexities of mental disorders, including taking a transdiagnostic or trans-syndromal approach, and including areas of resilience and psychosocial disabilities given, their complex relationships with psychopathology.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LP: Writing – original draft. SC: Writing – original draft. BB: Writing – original draft. AC: Writing – review & editing. JH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1473051/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Material 1 | Search strategy used for PsycINFO.

References

1. Fava GA, Kellner R. Staging: a neglected dimension in psychiatric classification. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. (1993) 87:225–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03362.x

2. Schnyder U. Longitudinal development of symptoms and staging in psychiatry and clinical psychology: a tribute to Giovanni Fava. Psychother Psychosomatics. (2023) 92:4–8. doi: 10.1159/000527462

3. Scott J, Leboyer M, Hickie I, Berk M, Kapczinski F, Frank E, et al. Clinical staging in psychiatry: a cross-cutting model of diagnosis with heuristic and practical value. Br J Psychiatry. (2013) 202:243–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.110858

4. McGorry PD, Hickie IB, Yung AR, Pantelis C, Jackson HJ. Clinical staging of psychiatric disorders: a heuristic framework for choosing earlier, safer and more effective interventions. Aust New Z J Psychiatry. (2006) 40:616–22. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01860.x

5. McGorry PD, Purcell R, Hickie IB, Yung AR, Pantelis C, Jackson HJ. Clinical staging: a heuristic model for psychiatry and youth mental health. Med J Australia. (2007) 187:S40–S2. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01335.x

6. McGorry PD, Nelson B, Goldstone S, Yung AR. Clinical staging: a heuristic and practical strategy for new research and better health and social outcomes for psychotic and related mood disorders. Can J Psychiatry. (2010) 55:486–97. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500803

7. Evers AW, Gieler U, Hasenbring MI, Van Middendorp H. Incorporating biopsychosocial characteristics into personalized healthcare: a clinical approach. Psychother psychosomatics. (2014) 83:148–57. doi: 10.1159/000358309

8. McGorry PD, Mei C. Clinical staging for youth mental disorders: progress in reforming diagnosis and clinical care. Annu Rev Dev Psychol. (2021) 3:15–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-devpsych-050620-030405

9. McGorry PD. RETRACTED ARTICLE: staging in neuropsychiatry: A heuristic model for understanding, prevention and treatment. Neurotoxicity Res. (2010) 18:244–55. doi: 10.1007/s12640-010-9179-x

10. McGorry P, Purcell R. Youth mental health reform and early intervention: encouraging early signs. Early intervention Psychiatry. (2009) 3:161–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2009.00128.x

11. Cosci F, Fava GA. Staging of mental disorders: Systematic review. Psychother Psychosomatics. (2013) 82:20–34. doi: 10.1159/000342243

12. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J surgery. (2021) American Psychiatric Association. 88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

13. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (1980).

14. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (1987). revised.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (1994).

16. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (2000). text rev.

17. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

18. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research diagnostic criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1978) 35(6):773–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013

19. World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases Eleventh Revision (ICD-11). 11th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

21. Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Library Association: JMLA. (2016) 104:240. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014

22. Kellermeyer L, Harnke B, Knight S. Covidence and rayyan. J Med Library Association: JMLA. (2018) 106:580. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2018.513

23. Gisev N, Bell JS, Chen TF. Interrater agreement and interrater reliability: key concepts, approaches, and applications. Res Soc Administrative Pharmacy. (2013) 9:330–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.04.004

24. Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch V. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken: Wiley (2019).

25. Armando M, Hutsebaut J, Debbané M. A mentalization-informed staging approach to clinical high risk for psychosis. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00385

26. Berendsen S, van der Paardt J, van Bruggen M, Nusselder H, Jalink M, Peen J, et al. Exploring construct validity of clinical staging in schizophrenia spectrum disorders in an acute psychiatric ward. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. (2018). doi: 10.3371/CSRP.BEPA.061518

27. Berendsen S, Van HL, van der Paardt JW, de Peuter OR, van Bruggen M, Nusselder H, et al. Exploration of symptom dimensions and duration of untreated psychosis within a staging model of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Early Intervention Psychiatry. (2021) 15:669–75. doi: 10.1111/eip.13006

28. Berendsen S, Nummenin E, Schirmbeck F, de Haan L, van Tricht M, Bartels-Velthuis AA, et al. Association of cognitive performance with clinical staging in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a prospective 6-year follow-up study. Schizophr Research: Cognition. (2022) 28:100232. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2021.100232

29. Godin O, Fond G, Bulzacka E, Schürhoff F, Boyer L, Myrtille A, et al. Validation and refinement of the clinical staging model in a French cohort of outpatient with schizophrenia (FACE-SZ). Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2019) 92:226–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.01.003

30. Kommescher M, Gross S, Pützfeld V, Klosterkötter J, Bechdolf A. Coping and the stages of psychosis: an investigation into the coping styles in people at risk of psychosis, in people with first-episode and multiple-episode psychoses. Early Intervention Psychiatry. (2017) 11:147–55. doi: 10.1111/eip.2017.11.issue-2

31. Li L, Rami FZ, Piao YH, Lee BM, Kim WS, Sui J, et al. Comparison of clinical features and 1-year outcomes between patients with psychotic disorder not otherwise specified and those with schizophrenia. Early intervention Psychiatry. (2022) 16:1309–18. doi: 10.1111/eip.v16.12

32. Higuchi CH, Cogo-Moreira H, Fonseca L, Ortiz BB, Correll CU, Noto C, et al. Identifying strategies to improve PANSS based dimensional models in schizophrenia: Accounting for multilevel structure, Bayesian model and clinical staging. Schizophr Res. (2021) 243:424–30. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.06.034

33. Peralta V, de Jalón EG, Moreno-Izco L, Peralta D, Janda L, Sánchez-Torres AM, et al. A clinical staging model of psychotic disorders based on a long-term follow-up of first-admission psychosis: A validation study. Psychiatry Res. (2023) 322:115109. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115109

34. Ruiz-Iriondo M, Salaberría K, Polo-López R, Iruin Á, Echeburúa E. Improving clinical symptoms, functioning, and quality of life in chronic schizophrenia with an integrated psychological therapy (IPT) plus emotional management training (EMT): A controlled clinical trial. Psychother Res. (2020) 30:1026–38. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2019.1683634

35. Rapado-Castro M, Berk M, Venugopal K, Bush AI, Dodd S, Dean OM. Towards stage specific treatments: Effects of duration of illness on therapeutic response to adjunctive treatment with N-acetyl cysteine in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2015) 57:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.10.002

36. Falkai P, Dombi ZB, Acsai K, Barabássy Á, Schmitt A, Németh G. The efficacy and safety of cariprazine in the early and late stage of schizophrenia: a post hoc analysis of three randomized, placebo-controlled trials. CNS spectrums. (2023) 28:104–11. doi: 10.1017/S1092852921000997

37. Bagney A, Rodriguez-Jimenez R, Martinez-Gras I, Sanchez-Morla EM, Santos JL, Jimenez-Arriero MA, et al. Negative symptoms and executive function in schizophrenia: does their relationship change with illness duration? Psychopathology. (2013) 46:241–8. doi: 10.1159/000342345

38. Ortiz BB, Eden FDM, de Souza ASR, Teciano CA, de Lima DM, Noto C, et al. New evidence in support of staging approaches in schizophrenia: Differences in clinical profiles between first episode, early stage, and late stage. Compr Psychiatry. (2017) 73:93–6. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.11.006

39. Sauvé G, Brodeur MB, Shah JL, Lepage M. The prevalence of negative symptoms across the stages of the psychosis continuum. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. (2019) 27:15–32. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000184

40. Carrión RE, Correll CU, Auther AM, Cornblatt BA. A severity-based clinical staging model for the psychosis prodrome: Longitudinal findings from the New York recognition and prevention program. Schizophr Bull. (2017) 43:64–74. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw155

41. Dragioti E, Wiklund T, Siamouli M, Moutou K, Fountoulakis KN. Could PANSS be a useful tool in the determining of the stages of schizophrenia? A clinically operational approach. J Psychiatr Res. (2017) 86:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.11.013

42. Fountoulakis KN, Dragioti E, Theofilidis AT, Wikilund T, Atmatzidis X, Nimatoudis I, et al. Staging of Schizophrenia with the use of PANSS: an international multi-center study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. (2019) 22:681–97. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyz053

43. Fountoulakis KN, Dragioti E, Theofilidis AT, Wiklund T, Atmatzidis X, Nimatoudis I, et al. Modeling psychological function in patients with schizophrenia with the PANSS: An international multi-center study. CNS Spectrums. (2021) 26:290–8. doi: 10.1017/S1092852920001091

44. Fountoulakis KN, Dragioti E, Theofilidis AT, Wiklund T, Atmatzidis X, Nimatoudis I, et al. Gender, age at onset, and duration of being ill as predictors for the long-term course and outcome of schizophrenia: an international multicenter study. CNS Spectrums. (2022) 27:716–23. doi: 10.1017/S1092852921000742

45. Fusar-Poli P, Estradé A, Stanghellini G, Venables J, Onwumere J, Messas G, et al. The lived experience of psychosis: A bottom-up review co-written by experts by experience and academics. World Psychiatry. (2022) 21(2):168–88. doi: 10.1002/wps.20959

46. Magalhães PV, Dodd S, Nierenberg AA, Berk M. Cumulative morbidity and prognostic staging of illness in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Aust New Z J Psychiatry. (2012) 46:1058–67. doi: 10.1177/0004867412460593

47. Duffy A, Alda M, Hajek T, Sherry SB, Grof P. Early stages in the development of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. (2010) 121:127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.022

48. Duffy A. The early natural history of bipolar disorder: what we have learned from longitudinal high-risk research. Can J Psychiatry. (2010) 55:477–85. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500802

49. Duffy A, Horrocks J, Milin R, Doucette S, Persson G, Grof P. Adolescent substance use disorder during the early stages of bipolar disorder: A prospective high-risk study. J Affect Disord. (2012) 142:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.010

50. Duffy A, Horrocks J, Doucette S, Keown-Stoneman C, McCloskey S, Grof P. The developmental trajectory of bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. (2014) 204:122–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.126706

51. Duffy A. Toward a comprehensive clinical staging model for bipolar disorder: integrating the evidence. Can J Psychiatry. (2014) 59:659–66. doi: 10.1177/070674371405901208

52. Berk M, Berk L, Dodd S, Cotton S, Macneil C, Daglas R, et al. Stage managing bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. (2014) 16:471–7. doi: 10.1111/bdi.2014.16.issue-5

53. Chanen AM, Berk M, Thompson K. Integrating early intervention for borderline personality disorder and mood disorders. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. (2016) 24:330–41. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000105

54. Power P. Intervening early in bipolar disorder in young people: A review of the clinical staging model. Irish J psychol Med. (2015) 32:31–43. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2014.72

55. Lee Y, Lee D, Jung H, Cho Y, Baek JH, Hong KS. Heterogeneous early illness courses of Korean patients with bipolar disorders: replication of the staging model. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:684. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04318-y

56. van der Markt A, Klumpers UM, Draisma S, Dols A, Nolen WA, Post RM, et al. Testing a clinical staging model for bipolar disorder using longitudinal life chart data. Bipolar Disord. (2019) 21:228–34. doi: 10.1111/bdi.2019.21.issue-3

57. Berk M, Hallam KT, McGorry PD. The potential utility of a staging model as a course specifier: a bipolar disorder perspective. J Affect Disord. (2007) 100:279–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.03.007

58. Kupka RW, Hillegers MH. Stagering en profilering bij bipolaire stoornissen [Staging and profiling in bipolar disorders]. Tijdschr Psychiatr. (2012) 54(11):949–56.

59. Kapczinski F, Dias VV, Kauer-Sant’Anna M, Frey BN, Grassi-Oliveira R, Colom F, et al. Clinical implications of a staging model for bipolar disorders. Expert Rev neurotherapeutics. (2009) 9:957–66. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.31

60. Rosa AR, Magalhães PV, Czepielewski L, Sulzbach MV, Goi PD, Vieta E, et al. Clinical staging in bipolar disorder: focus on cognition and functioning. J Clin Psychiatry. (2014) 75:2951. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08625

61. Goi PD, Bücker J, Vianna-Sulzbach M, Rosa AR, Grande I, Chendo I, et al. Pharmacological treatment and staging in bipolar disorder: evidence from clinical practice. Braz J Psychiatry. (2015) 37:121–5. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1554

62. van der Markt A, Klumpers UM, Dols A, Draisma S, Boks MP, van Bergen A, et al. Exploring the clinical utility of two staging models for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. (2020) 22:38–45. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12825

63. Macellaro M, Girone N, Cremaschi L, Bosi M, Cesana BM, Ambrogi F, et al. Staging models applied in a sample of patients with bipolar disorder: Results from a retrospective cohort study. J Affect Disord. (2023) 323:452–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.11.081

64. Rosa A, González-Ortega I, González-Pinto A, Echeburúa E, Comes M, Martínez-Àran A, et al. One-year psychosocial functioning in patients in the early vs. late stage of bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. (2012) 125:335–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01830.x

65. Peters A, Sylvia L, da Silva Magalhães P, Miklowitz D, Frank E, Otto M, et al. Age at onset, course of illness and response to psychotherapy in bipolar disorder: results from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). psychol Med. (2014) 44:3455–67. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000804

66. Morriss R, Lobban F, Riste L, Davies L, Holland F, Long R, et al. Clinical effectiveness and acceptability of structured group psychoeducation versus optimised unstructured peer support for patients with remitted bipolar disorder (PARADES): a pragmatic, multicentre, observer-blind, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. (2016) 3:1029–38. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30302-9

67. Murray G, Leitan ND, Berk M, Thomas N, Michalak E, Berk L, et al. Online mindfulness-based intervention for late-stage bipolar disorder: pilot evidence for feasibility and effectiveness. J Affect Disord. (2015) 178:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.024

68. Kamali M, Pegg S, Janos JA, Bobo WV, Brody B, Gao K, et al. Illness stage and predominant polarity in bipolar disorder: Correlation with burden of illness and moderation of treatment outcome. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 140:205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.05.082

69. Reinares M, Papachristou E, Harvey P, Bonnín CM, Sánchez-Moreno J, Torrent C, et al. Towards a clinical staging for bipolar disorder: defining patient subtypes based on functional outcome. J Affect Disord. (2013) 144:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.005

70. Grande I, Magalhães P, Chendo I, Stertz L, Panizutti B, Colpo G, et al. Staging bipolar disorder: clinical, biochemical, and functional correlates. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. (2014) 129:437–44. doi: 10.1111/acps.2014.129.issue-6

71. Rhee TG, Mohamed S, Rosenheck RA. Stages of major depressive disorder and behavioral multi-morbidities: Findings from nationally representative epidemiologic study. J Affect Disord. (2021) 278:443–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.081

72. Verduijn J, Milaneschi Y, van Hemert AM, Schoevers RA, Hickie IB, Penninx BW, et al. Clinical staging of major depressive disorder: an empirical exploration. J Clin Psychiatry. (2015) 76:2953. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09272

73. Reneses B, Aguera-Ortiz L, Sevilla-Llewellyn-Jones J, Carrillo A, Argudo I, Regatero MJ, et al. Staging of depressive disorders: relevance of resistance to treatment and residual symptoms. J Psychiatr Res. (2020) 129:234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.022

74. Hetrick S, Parker A, Hickie I, Purcell R, Yung A, McGorry P. Early identification and intervention in depressive disorders: towards a clinical staging model. Psychother psychosomatics. (2008) 77:263–70. doi: 10.1159/000140085

75. Dodd S, Berk M, Kelin K, Mancini M, Schacht A. Treatment response for acute depression is not associated with number of previous episodes: Lack of evidence for a clinical staging model for major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. (2013) 150:344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.016

76. Clarke PJ, Hickie IB, Scott E, Guastella AJ. Clinical staging model applied to young people presenting with social anxiety. Early Intervention Psychiatry. (2012) 6:256–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2012.00364.x

77. Hickie IB, Scott EM, Hermens DF, Naismith SL, Guastella AJ, Kaur M, et al. Applying clinical staging to young people who present for mental health care. Early intervention Psychiatry. (2013) 7:31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2012.00366.x

78. Bokma WA, Batelaan NM, Hoogendoorn AW, Penninx BW, van Balkom AJ. A clinical staging approach to improving diagnostics in anxiety disorders: Is it the way to go? Aust New Z J Psychiatry. (2020) 54(2):173–84. doi: 10.1177/0004867419887804

79. Fineberg NA, Dell’Osso B, Albert U, Maina G, Geller D, Carmi L, et al. Early intervention for obsessive compulsive disorder: An expert consensus statement. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2019) 29:549–65. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2019.02.002

80. Fontenelle LF, Yücel M. A clinical staging model for obsessive–compulsive disorder: is it ready for prime time? EClinicalMedicine. (2019) 7:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.01.014

81. Benatti B, Lucca G, Zanello R, Fesce F, Priori A, Poloni N, et al. Application of a staging model in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: cross-sectional and follow-up results. CNS Spectrums. (2022) 27:218–24. doi: 10.1017/S1092852920001972

82. McFarlane AC, Lawrence-Wood E, Van Hooff M, Malhi GS, Yehuda R. The need to take a staging approach to the biological mechanisms of PTSD and its treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2017) 19:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0761-2

83. Ramos-Lima LF, Waikamp V, Oliveira-Watanabe T, Recamonde-Mendoza M, Teche SP, Mello MF, et al. Identifying posttraumatic stress disorder staging from clinical and sociodemographic features: a proof-of-concept study using a machine learning approach. Psychiatry Res. (2022) 311:114489. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114489

84. Nijdam MJ, Vermetten E, McFarlane AC. Toward staging differentiation for posttraumatic stress disorder treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. (2023) 147:65–80. doi: 10.1111/acps.v147.1

85. Boelen PA, Olff M, Smid GE. Traumatic loss: Mental health consequences and implications for treatment and prevention. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2019) 10(1):1591331. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1591331

86. Treasure J, Stein D, Maguire S. Has the time come for a staging model to map the course of eating disorders from high risk to severe enduring illness? An examination of the evidence. Early Intervention Psychiatry. (2015) 9:173–84. doi: 10.1111/eip.2015.9.issue-3

87. Treasure J, Willmott D, Ambwani S, Cardi V, Bryan DC, Rowlands K, et al. Cognitive interpersonal model for anorexia nervosa revisited: The perpetuating factors that contribute to the development of the severe and enduring illness. J Clin Med. (2020) 9(3):630. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030630

88. Ambwani S, Cardi V, Albano G, Cao L, Crosby RD, Macdonald P, et al. A multicenter audit of outpatient care for adult anorexia nervosa: Symptom trajectory, service use, and evidence in support of “early stage” versus “severe and enduring” classification. Int J Eating Disord. (2020) 53:1337–48. doi: 10.1002/eat.23246

89. Hutsebaut J, Videler AC, Verheul R, Van Alphen SPJ. Managing borderline personality disorder from a life course perspective: Clinical staging and health management. Pers Disorders: Theory Research Treat. (2019) 10:309–16. doi: 10.1037/per0000341

90. Iorfino F, Scott EM, Carpenter JS, Cross SP, Hermens DF, Killedar M, et al. Clinical stage transitions in persons aged 12 to 25 years presenting to early intervention mental health services with anxiety, mood, and psychotic disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. (2019) 76:1167–75. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2360

91. Addington J, Liu L, Goldstein BI, Wang J, Kennedy SH, Bray S, et al. Clinical staging for youth at-risk for serious mental illness. Early Intervention Psychiatry. (2019) 13:1416–23. doi: 10.1111/eip.12786

92. Addington J, Liu L, Farris MS, Goldstein BI, Wang JL, Kennedy SH, et al. Clinical staging for youth at-risk for serious mental illness: A longitudinal perspective. Early Intervention Psychiatry. (2021) 15:1188–96. doi: 10.1111/eip.13062

93. Hermens DF, Naismith SL, Lagopoulos J, Lee RS, Guastella AJ, Scott EM, et al. Neuropsychological profile according to the clinical stage of young persons presenting for mental health care. BMC Psychol. (2013) 1:1–9. doi: 10.1186/2050-7283-1-8

94. Ratheesh A, Hammond D, Gao C, Marwaha S, Thompson A, Hartmann J, et al. Empirically driven transdiagnostic stages in the development of mood, anxiety and psychotic symptoms in a cohort of youth followed from birth. Trans Psychiatry. (2023) 13:103. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02396-4

95. Romanowska S, MacQueen G, Goldstein BI, Wang J, Kennedy SH, Bray S, et al. Neurocognitive deficits in a transdiagnostic clinical staging model. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 270:1137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.030

96. Tickell AM, Lee RSC, Hickie IB, Hermens DF. The course of neuropsychological functioning in young people with attenuated vs discrete mental disorders. Early Intervention Psychiatry. (2019) 13:425–33. doi: 10.1111/eip.2019.13.issue-3

97. Scott EM, Robillard R, Hermens DF, Naismith SL, Rogers NL, Ip TKC, et al. Dysregulated sleep-wake cycles in young people are associated with emerging stages of major mental disorders. Early Intervention Psychiatry. (2016) 10:63–70. doi: 10.1111/eip.2016.10.issue-1

98. Cross SP, Hermens DF, Scott J, Salvador-Carulla L, Hickie IB. Differential impact of current diagnosis and clinical stage on attendance at a youth mental health service. Early Intervention Psychiatry. (2017) 11:255–62. doi: 10.1111/eip.2017.11.issue-3

99. Hamilton MP, Hetrick SE, Mihalopoulos C, Baker D, Browne V, Chanen AM, et al. Targeting mental health care attributes by diagnosis and clinical stage: the views of youth mental health clinicians. Med J Australia. (2017) 207:S19–26. doi: 10.5694/mja2.2017.207.issue-S10

100. Hartmann JA, McGorry PD, Destree L, Amminger GP, Chanen AM, Davey CG, et al. Pluripotential risk and clinical staging: theoretical considerations and preliminary data from a transdiagnostic risk identification approach. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:553578. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.553578

101. Wigman JTW, Van Nierop M, Vollebergh WAM, Lieb R, Beesdo-Baum K, Wittchen HU, et al. Evidence that psychotic symptoms are prevalent in disorders of anxiety and depression, impacting on illness onset, risk, and severity - Implications for diagnosis and ultra-high risk research. Schizophr Bulletin. (2012) 38:247–57. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr196

102. Shah JL, Jones N, van Os J, McGorry PD, Gülöksüz S. Early intervention service systems for youth mental health: integrating pluripotentiality, clinical staging, and transdiagnostic lessons from early psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2022) 9:413–22. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00467-3