- 1School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China

- 2Internal Encephalopathy of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Dongfang Hospital of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China

Introduction: Depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms are highly comorbid and represent the most prevalent psychosomatic health issues. Few studies have investigated the network structure of psychosomatic symptoms among traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) students. This study aims to investigate the psychosomatic health status of college students in TCM universities, while simultaneously constructing a network structure of common somatic symptoms and psychological symptoms.

Methods: Online investigation was conducted among 665 students from a university of Chinese medicine. Health Status Questionnaire, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), and Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) were used to assess the mental symptoms and physical status of participants. With the R software processing, a network model of psychosomatic symptoms was constructed. Specifically, we computed the predictability (PRE), expected influence (EI), and bridging expected influence (BEI) of each symptom. Meanwhile, the stability and accuracy of the network were evaluated using the case-deletion bootstrap method.

Results: Among the participants, 277 (41.65%) subjects exhibited depressive symptoms, and 244 (36.69%) subjects showed symptoms of anxiety. Common somatic symptoms included fatigue, forgetfulness, sighing, thirst, and sweating. Within the psychosomatic symptoms network, “ worrying too much about things “, “uncontrollable worries” and “weakness” exhibited the high EI and PRE, suggesting they are central symptoms. “ Little interest or pleasure in doing things,” “ feeling down, depressed, or hopeless,” “ dyssomnia,” and “sighing” with high BEI values demonstrated that they are bridging symptoms in the comorbid network.

Conclusion: The psychosomatic health status of college students in traditional Chinese medicine schools is concerning, showing high tendencies for depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms. There exists a complex relationship between somatic symptoms and psychological symptoms among students. “ Worrying too much about things “, “uncontrollable worries” and “weakness” enable to serve as comorbid intervention targets for anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms. Addressing “ little interest or pleasure in doing things,” “ feeling down, depressed, or hopeless,” “ dyssomnia,” and “sighing” may effectively prevent the mutual transmission between psychological and physical symptoms. The network model highlighting the potential targeting symptoms to intervene in the treatment of psychosomatic health.

1 Introduction

Mental health is considered as the foundation of human health in the “Mental Health Action Plan (2020-2030)” of the World Health Organization (1). Nowadays, mental health issue is the leading cause of disability and a major public health concern worldwide. Depression and anxiety are important indicators of mental health, which are closely associated with somatic symptoms. Researches indicate that patients with anxiety and depression often exhibit somatic symptoms in clinical settings (2). Usually, somatic symptoms give raise to the impairment in daily life and work, as well as a primary reason for seeking medical care. Many of these symptoms are purely subjective discomfort without organic pathology, serving as outward manifestations of impaired mental health (3). Somatic symptoms, anxiety and depression constitute the three most common psychosomatic health issues. At least one-third of individuals with somatic symptom disorders concurrently experience anxiety and depression, highlighting a high comorbidity among these conditions (4, 5). The comorbid mechanisms among anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms need to be further investigated. Menkes et al. found that some exogenous interferons can induce depression by inhibiting serotonin synthesis, thereby leading to fatigue and somatic symptoms (such as limb pain) (6). Rudolf et al. discovered that patients with anxiety disorders exhabited lower autonomic nervous system adaptability compared to healthy individuals, with more abnormal neuroregulation. As a result, the lower perception threshold for external stimuli is obtained for the patients, causing their central nervous system to struggle in accurately distinguishing whether the received stimuli are related to anxiety or neutral stimuli (7). Meanwhile, research shows a gradual increase in psychosomatic health issues among adolescents (8, 9).The somatic and psychological problems has became the significant components of mental disorders (10).

Current research on anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms mostly relies on traditional latent variable theories in which the symptoms of mental disorders are interpreted as outcomes of underlying common factors (11). However, from this perspective, the co-occurrence or random clustering of different symptoms in mental disorders is attributed to the latent common factors that cannot be directly observed (12). Therefore, these methods based on the latent variable theories usually capture common differences among all symptoms. They overlook information related to the individual development of mental disorders (13, 14).

Recently, the network analysis has provided a new insight to understanding psychopathological symptoms (15). The network theory of psychopathology no longer regards mental disorders as underlying entities behind symptoms, but rather considers symptoms as integral components of mental disorders (16). It explores the interactions among individual psychopathological symptoms to reveal connections among individual variables (15, 17). In network analysis, nodes represent symptoms, and edges (lines between nodes) denote connections between symptoms. The weight of an edge signifies the strength of the association. The nodes connected with more edges and with larger weights suggest their higher centrality (18). Researchers often focus on nodes with higher centrality because these nodes can bring about prominent influence or can be used to predict other nodes. Additionally, network analysis offers a fresh perspective on the mechanisms of comorbidity in mental disorders, providing an intuitive depiction of the relationships among symptom clusters (19, 20). The “bridge variables” are established to connect different symptom clusters, which are beneficial to understand interactions between symptom clusters and identify targets for targeted interventions (20–22). Numbers of studies have utilized network analysis in mental disorders. Yang et al., explored the correlation among personality traits, anxiety and depression in college students (23). Luo et al., analyzed the comorbid characteristics of anxiety and depression symptoms in the student groups (14). Liu et al., used network analysis to explore bridging symptoms between depression and anxiety in HIV patients (24). However, the network analysis between psychosomatic symptoms needs to be further explored. Constructing networks of psychosomatic symptoms allows exploration of the relationship between somatic symptoms and psychological symptoms from a comorbidity perspective, thereby bridging research gaps between physical and psychological fields.

College students are a critical transitional stage from late adolescence to early adulthood, which are a high-risk group for physical and mental illnesses. Compared to other countries, the incidence of psychosomatic health issues among Chinese university students is relatively high (25–27), which may be owing to the large population, significant competitive pressure, and limited resources for mental health education. Among undergraduate students in Chinese comprehensive universities, 11.8% of them exhibited severe or moderate somatic symptoms; the students with severe anxiety symptoms accounted for 7.8% of the surveyed students; and severe depression symptoms are reported by 23.3% (28). Medical schools are a relatively unique category within universities, characterized by specialized programs, longer durations, extensive coursework, and high employment pressures. These characteristics of medical schools contribute to greater stress for medical students. Research suggested that 20% to 67% of medical students experience varying degrees of psychosomatic health issues, which was significantly higher than the 10% to 30% observed in regular college students (29).Within medical schools, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) universities represent a unique presence because of blending elements of medical education with both natural and humanistic sciences. Meanwhile, TCM universities are widespread across nearly every province of China. However, there is currently limited research on the psychosomatic health characteristics of college students in TCM universities.

In this work, taking the TCM college students as objects, their psychosomatic status was investigated by a comprehensive questionnaire survey. Based on the investigation results, we constructed a network model (Psychosomatic Symptoms Network Model) which comprised somatic symptoms and anxiety-depression symptoms. The central and bridging symptoms within this network were also explored to elucidate important connections between somatic symptoms and psychological symptoms. This work describes the current psychosomatic health status of TCM college students. In addition, the network model we proposed provides theoretical insights into specific pathways linking somatic symptoms with psychological symptoms.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

An online survey was adopted via the survey links (www.wjx.cn), and the survey link was distributed to college students from Beijing University of Chinese Medicin. Participants were briefed on the purpose of survey and how to complete the questionnaire. The informed consents were obtained from participants. A total of 665 participants completed the survey from April to May 2024. The survey consisted of conventional information of the participant, Health Status Questionnaire, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), and Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2). This work strictly adhered to the principles of “Helsinki Declaration” and received approval from the Ethics Committee of BUCM (No. 2024BZYLL0105)

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Health status questionnaire

The health status questionnaire was revised based on literature research and expert consultation. It is a self-assessment questionnaire that includes 30 relevant symptoms (items) categorized into overall symptoms, head-face-neck symptoms, chest-abdomen symptoms, diet, sleep, bowel movements, etc. All items are presented in clear and understandable description. Each item employs a 4-point rating scale: 0 points for “none,” 1 point for “occasional,” 2 points for “sometimes,” and 3 points for “frequent”. For example, “Do you feel dizzy?” Responses such as “none,” “occasional,” “sometimes,” and “frequent” correspond to 0 points, 1 point, 2 points, and 3 points respectively. Previous research has confirmed that this questionnaire has good reliability and validity, accurately reflecting the participants’ physical health status (30). In this investigation, the Cronbach’s α for health status questionnaire was 0.92.

2.2.2 Generalized anxiety disorder-7

The GAD-7 is a common tool for evaluating anxiety symptoms, developed by Spitzer et al (31). This investigation employed the version of GAD-7 revised by He et al. The version is suitable for the Chinese context and has demonstrated good reliability and validity among Chinese populations (32, 33). The GAD-7 consists of 7 items including excessive worry, difficulty relaxing, feeling restless, irritability, and fear. Each item employs a 4-point Likert scale: 0, 1, 2, 3 points representing “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day,” respectively. A total score of ≥ 5 on the GAD-7 indicates an anxiety state (34). In this investigation, the Cronbach’s α for the GAD-7 was 0.91.

2.2.3 Patient health questionnaire-2

The PHQ-2, developed by Kroenke et al., is a brief and widely used screening tool for depression (35). The PHQ-2 consists of 2 items: “little interest or pleasure in doing things” and “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”. Similarly, a 4-point Likert scale was employed for each item: 0, 1, 2, 3 points indicating “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day,” respectively. A total score of ≥ 2 on the PHQ-2 suggests the depression (36). Related studies have confirmed that the PHQ-2 has good reliability and validity in screening for depressive symptoms (36). In this investigation, the Cronbach’s α for the PHQ-2 was 0.72.

2.3 Statistical analysis

2.3.1 General information statistics

Descriptive statistics of the participants were conducted by SPSS 26.0. The classification data was expressed in terms of frequencies and component ratios. The mean ± standard deviation was used for the description of continuous variables. Bivariate correlations between psychological symptoms and somatic symptoms were obtained by Spearman correlation analysis.

2.3.2 Network model construction

The qgraph package in R software (version 4.4.0) (37) was employed to construct symptom networks based on EBICglasso function and Spearman correlation analysis. The EBICglasso function combines the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regularization with extended Bayesian information criterion (EBIC) (23). In this work, the EBIC hyperparameter γ was set to 0.5 (19). The Fruchterman-Reingold layout was utilized (38). The network was divided into the somatic symptom community and the anxiety-depression community. Nodes in each community represent somatic symptoms or items from GAD-7 and PHQ-2 scales. In the visualized network, blue edges between nodes indicate positive correlations, while red edges indicate negative correlations. Thicker edges signify stronger correlations between adjacent nodes (39).

The expected influence (EI) of each node was also calculated by qgraph package, which sums the values of all edges connected to that specific node. A higher EI value demonstrates the greater importance of the node within the network (40). Meanwhile, the bridge expected influence (BEI) of each node is calculated to identify bridging symptoms (41). The BEI is the sum of edge weights between a specific node and nodes in other communities (20). A larger BEI suggests the stronger influence of that node on another community (41). Nodes can be forecasted through their neighboring nodes. Predictability (PRE) of each node was obtained by R-package mgm (42). With PRE ranging from 0 to 1, the node with higher PRE indicates the stronger predictive ability of this node (43).

Network robustness test were assessed using the bootnet package, which includes the stability and the accuracy of the network (19). With a non-parametric bootstrap (1000 bootstrap samples), the accuracy of edge weight was evaluated via computing 95% confidence intervals (CI). Case-deletion bootstrap was employed to calculate the stability coefficient, with coefficients above 0.5 to indicate good stability of centrality indices (19). Bootstrap difference tests (1000 bootstrap samples, α = 0.05) were employed on edge weights, EI, and BEI to examine differences between two edge weights or two nodes.

3 Results

3.1 Demographic characteristics and descriptive statistics

Among 665 participants, there were 193 males (29.02%) and 472 females (70.98%). The age ranged from 18 to 32 years old, with an average age of 22.38 ± 3.20 years. Among them, 443 (66.62%) participants were undergraduates and 222 (33.38%) participants were graduate students.

3.1.1 Mental health

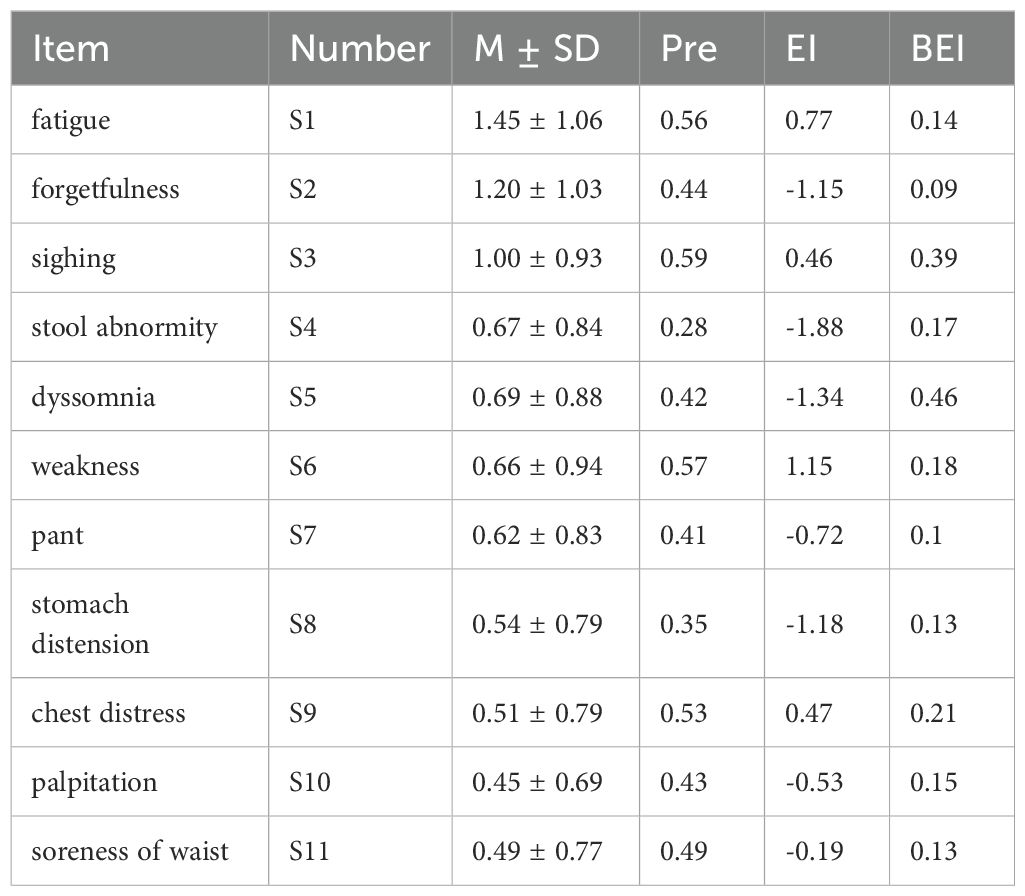

Varying degrees of anxiety and depression were discovered among participants, with 244 (36.69%) experiencing anxiety and 277 (41.65%) experiencing depression. Based on the GAD-7 and PHQ-2, the total scores, mean (M), standard deviation (SD), as shown in Table 1. Node numbers, Pre, EI, and BEI of items were also listed Table 1.

3.1.2 Somatic symptoms

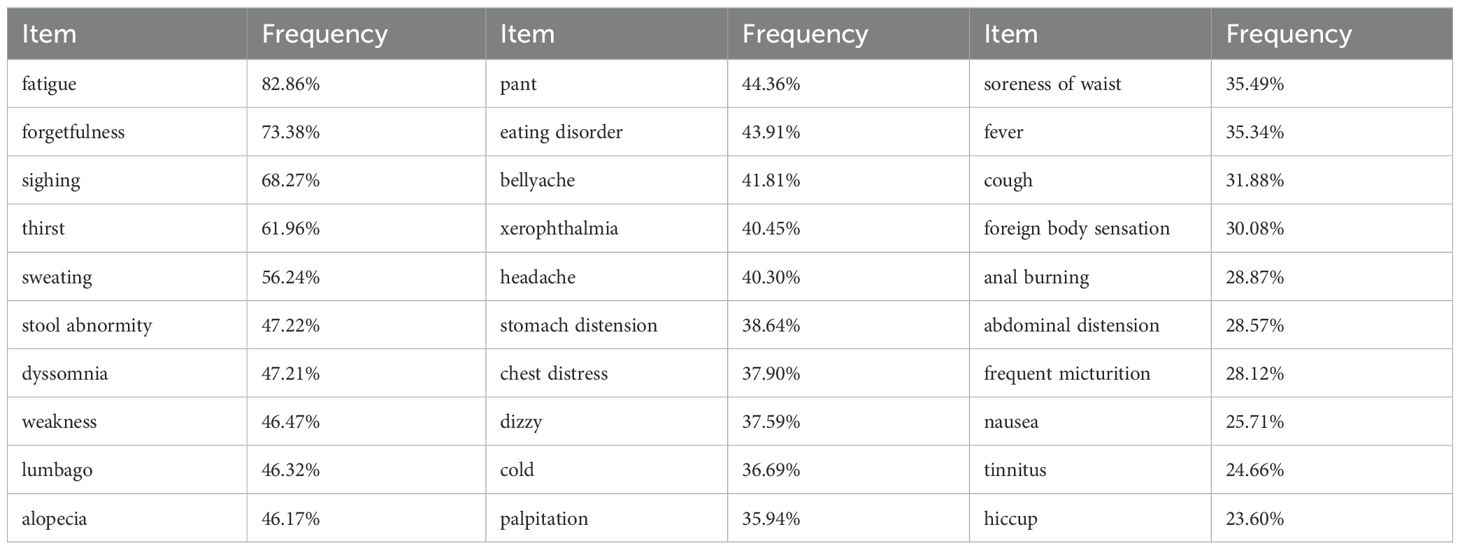

About 30 somatic symptoms were investigated, and their frequencies were studied, as shown in Table 2. Common somatic symptoms (> 50%) among participants included fatigue, forgetfulness, sighing, thirst, and sweating in order of frequency.

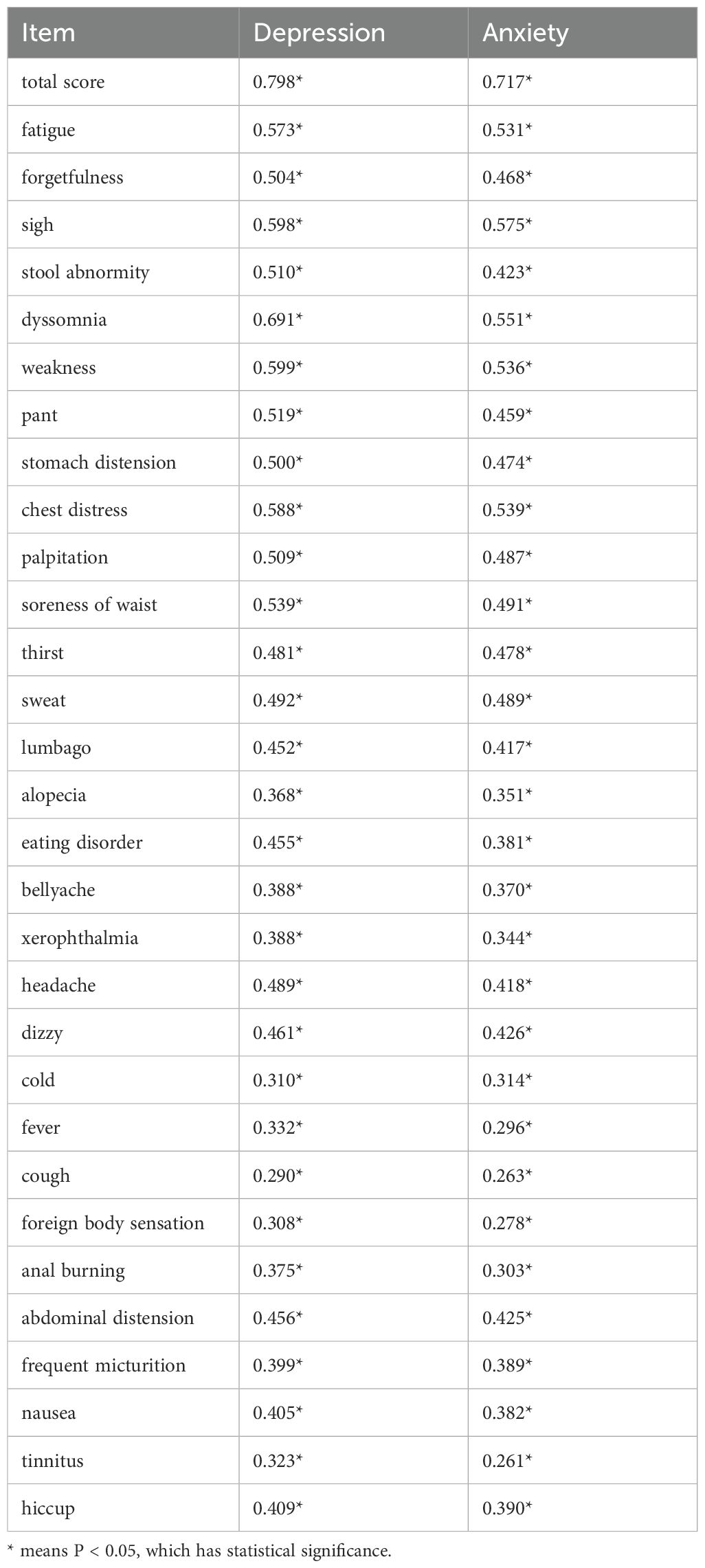

The correlation between somatic symptoms and anxiety/depression was shown in Table 3. Symptoms such as fatigue, forgetfulness, sighing, stool abnormity, dyssomnia, weakness, pant, stomach distension, chest tightness, palpitations, and soreness of waist had correlation coefficients r ≥ 0.5 with depression or anxiety, indicating strong relationships among these variables. Moreover, all symptoms were analyzed in the comorbid network to calculate their scores (M, SD) and parameters (PRE, EI, and BEI), as outlined in Table 4.

3.2 Network structure

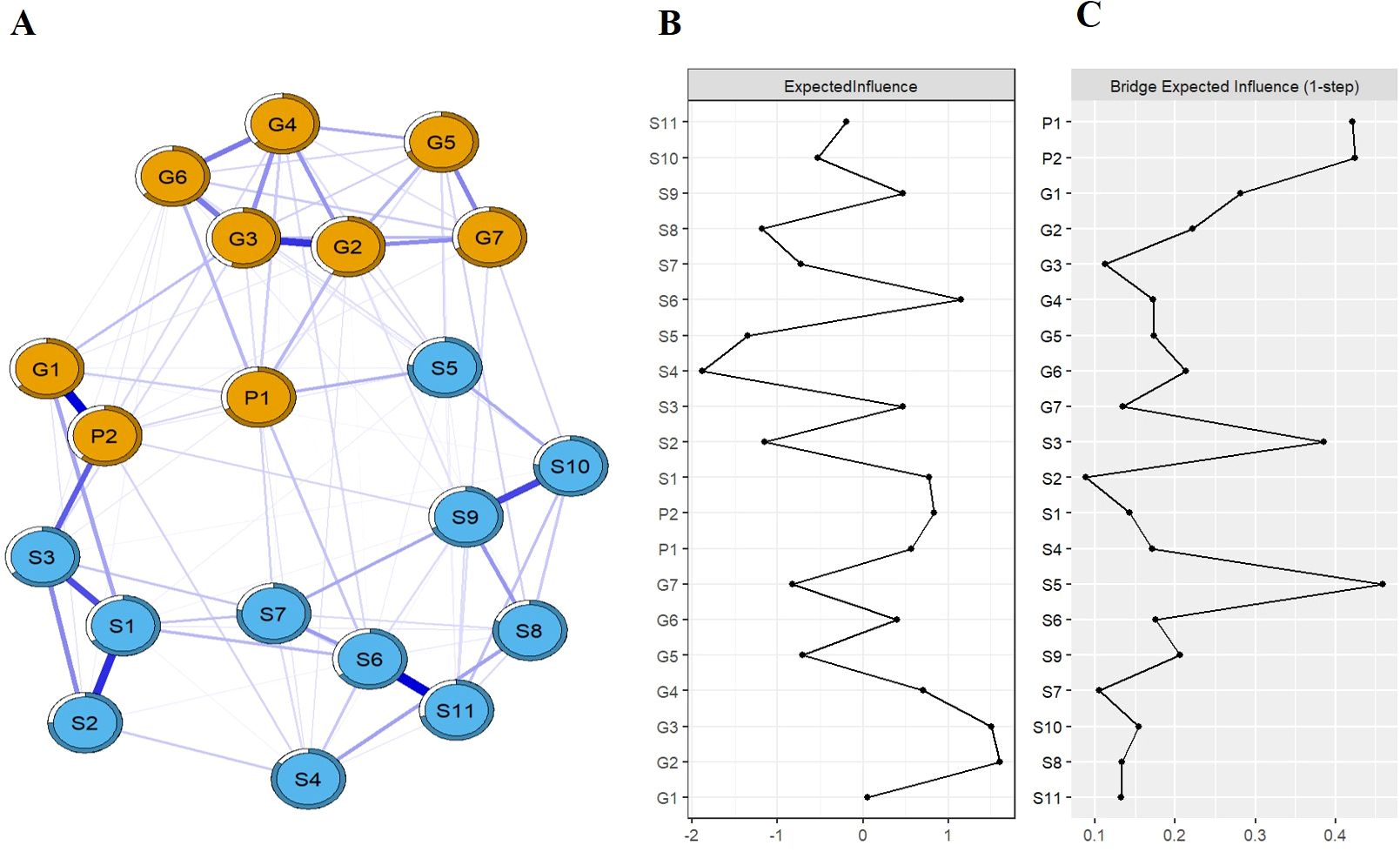

Figure 1A depicts the network structure of somatic symptoms with anxiety-depressive symptoms. The network structure (average weight of 0.048) includes 129 non-zero edges, and edge weights range from 0.00 to 0.38. Within the network, 52 edges (40.31%) bridge the somatic symptoms and the symptoms of anxiety/depression, and these52 bridging edges are all positively correlated. These edges with the top three weights are the bridge between “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless” and “sighing” (edge weight = 0.24), the bridge between “Feeling nervous, anxious or eager” and “fatigue” (edge weight = 0.14), and the bridge between “Little interest or pleasure in doing things” and “dyssomnia” (edge weight = 0.12). The correlation matrix of the network is also shown in Supplementary Table S1 of Supplementary Material. Bootstrap estimation of edge weights shows relatively narrow CI, indicating reliable evaluation of these edge weights, as depicted in Supplementary Figure S1. Testing differences of edge are also shown in Supplementary Figure S2. Additionally, predictability of node is represented by circle around this node. PRE values of nodes range from 0.28 to 0.69 in this network. The nodes of “Uncontrollable worries” and “Worrying too much about things” exhibit the high predictability, indicating that 67% and 69% of their variances can be explained by adjacent nodes, respectively.

The expected influences among somatic manifestations and symptoms of anxiety/depression are shown in Figure 1B. In the network, the nodes of “Uncontrollable worries”, “Worrying too much about things”, and “weakness” exhibit the large EI values (1.61, 1.51, and 1.15, respectively). Statistically, these three symptoms have the highest associations in comorbid network, considered as the central symptoms. Bootstrap difference test reveals a stable coefficient of 0.75 for the EI, suggesting the stability of EI evaluation (Supplementary Figure S3). Furthermore, bootstrap difference tests of EI demonstrate significant differences among the central symptoms and the majority (≥50%) of other symptoms, as shown in Supplementary Figure S4.

The bridging expected influences among somatic manifestations and symptoms of anxiety/depression are depicted in Figure 1C. Larger BEI values indicate stronger bridging centrality. The nodes of “dyssomnia”, “Little interest or pleasure in doing things”, “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”, and “sighing” are identified as bridging symptoms because of their high BEI (0.46, 0.42, 0.42, and 0.39, respectively). Bootstrap difference test obtains a coefficient of 0.67 for the stability of BEI evaluation (Supplementary Figure S5). Meanwhile, bootstrap difference tests of BEI demonstrate significant differences among the bridging symptoms and most other nodes (Supplementary Figure S6).

4 Discussion

In this study, the proportion of depression among college students was 41.65%, and anxiety was 36.69%. These proportions are significantly higher than the average rates of 32.74% for depression and 27.22% for anxiety among medical students in China, respectively (44). The differences of proportions may be attributed to variations of subjects, measurement tools, methods, and geographical factors. The high proportions reflect the serious states of depression and anxiety among college students of TCM universities. Compared to general medical students, TCM students face unique challenges such as learning both TCM and Western medicine, high academic pressures, and intense competition in employment. With the challenges exceeding their coping abilities, they are more prone to developing mental health issues (i.e. depression and anxiety). For physical health, we found various somatic symptoms with high frequencies (> 20%) among college students. Furthermore, the frequencies of some somatic manifestations (such as fatigue, forgetfulness, sighing, thirst, and sweating) exceed 50%. These physical discomforts have become prevalent issues affecting academic performance and daily lives of students, demanding significant attention.

From a causal systems perspective (CSP), this study investigated the interactions among psychosomatic symptoms in TCM university students. Compared with the traditional common cause perspective (CCP), this work attributed comorbidities to direct interactions among symptoms, providing an alternative explanation (14). The work identified the symptoms of “ worrying too much about things “, “uncontrollable worries” and “weakness” as central symptoms in the network. Both symptoms of “uncontrollable worries” and “ worrying too much about things “ refer to a persistent state of anxiousness, which are the common central symptoms in existing anxiety and depression network models. Cai et al. reported that the symptom of “worrying too much about things” was the central symptom of the anxiety-depression network adolescents in the later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (45). Zhang et al. discovered that the symptoms of “uncontrollable worries” and “worrying too much about things” were the core symptoms in the anxiety-depression network of Chinese elderly diabetic patients (46). Similar results have been reported in investigations on new university students of China (14). The recurring presence of “uncontrollable worries” or “worrying too much about things” as the central symptom across different groups highlights the significance in psychological manifestations. With insighting into the neuroendocrine perspective, persistent worry results in overactivity of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, increasing cortisol secretion, thereby leading to a range of somatic symptoms (i.e. dizziness, headaches, fatigue and palpitations) (47, 48). Therefore, the modulation of unnecessary worry is crucial for improving the psychosomatic health of college students. As another central symptom in this network, the somatic manifestation of “weakness” means a persistent feeling of tiredness and lack of energy. This sensation can significantly impact the activities in daily life, which also exhibits a relatively high occurrence (46.47%) among college students. College students often face high academic demands, such as complex subject knowledge, heavy assignments, and exam tasks. This pressure can lead to long study hours, insufficient rest and relaxation, ultimately resulting in weakness. Weakness can be classified into physiological and pathological types. Physiological weakness is usually caused by factors such as excessive exertion, lack of sleep, or poor nutrition, while pathological weakness may be a symptom of certain diseases. Psychological disorders (especially depression and anxiety) often accompany weakness, which affects not only the body but also emotional states. Additionally, weakness also contributes to psychological health issues. Chronic tiredness may lead to mood disturbances, anxiety, and depression, thereby creating a vicious cycle. From a psychopathological perspective, the comorbid mechanisms of weakness and psychological disorders involve complex interactions among neurobiological, inflammatory, sleep quality, and psychosocial factors. Within the comorbid network, these three symptoms are strongly associated with other symptoms because of their high EI values, playing a crucial role in activating and maintaining the network. Intervening in central symptoms of network can effectively reduce the overall severity of symptoms, thereby promoting treatment and prevention (49, 50).

BEI is an indicator for identifying bridging symptoms, and in this study the four symptoms with the highest BEI values were identified: “little interest or pleasure in doing things”, “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”, “sighing” and “dyssomnia”. In network analysis, bridging symptoms have cross-diagnostic significance as they serve to connect symptom networks from two different communities. Although there is a lack of network analysis studies on psychosomatic symptoms, in anxiety-depression network models, symptom of “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”and “little interest or pleasure in doing things” appears as bridging symptoms among Chinese new college students (14). During the COVID-19 pandemic, symptoms of “little interest or pleasure in doing things” and “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless” were identified as bridging symptoms in the anxiety-depression network of nursing students (51). Additionally, “little interest or pleasure in doing things” and “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless” were also typical symptoms for diagnosing major depression (52). The above studies highlight the importance of bridging symptoms “little interest or pleasure in doing things” and “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless” in psychological clinical manifestations, which matches the findings in this network analysis. In this study, these two symptoms also demonstrated their significant impact on physical manifestations, specifically their strong capacity to increase the risk of somatic symptoms. The somatic symptoms of “sighing” and “dyssomnia” are two additional bridging symptoms identified in this network, which exhibit the strongest ability to increase the risk of anxiety and depression contagion. Sighing is an external manifestation of anxiety/depression, and individuals may sigh to alleviate inner tension and repression when feeling anxious or depressed. However, frequent sighing enables to lead individuals to focus more on their negative emotions, worsening anxiety and depression. The serious influence makes sighing an important link in psychosomatic symptoms. Another bridging symptom is “ dyssomnia,” which aligns with previous research findings. A systematic review indicates that dyssomnia is bidirectionally associated with anxiety and depression in adolescents, adults, and the elderly (53). Meanwhile, the somatic manifestations of “dyssomnia” were also identified as a bridging symptom in the network of anxiety, depression, and insomnia for clinical practitioners with depressive symptoms (54). In terms of psychopathology, brain neurotransmitters are considered a common underlying mechanism linking dyssomnia with depression/anxiety. Imbalances in neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine can affect mood and sleep. Furthermore, a lack of sleep can reversely disrupt these neurotransmitters, yielding a negative feedback loop. As mentioned, bridging symptoms play a crucial role in the generation of comorbidities, which give raise to the onset and persistence of mental comorbidities. Intervening in bridging symptoms can effectively prevent or alleviate comorbid symptoms (55, 56).

The average node predictability of the network is 0.52, indicating a moderate level of self-determination (43). The predictability of nodes can reflect the controllability of the network and determine the effectiveness of the planned treatment (43). In this study, “uncontrollable worry” and “ Worrying too much about things” showed high predictability values that could be controlled by intervening in their adjacent nodes. However, symptoms with lower predictability, like “ stool abnormity” and “ stomach distension” may require direct control or intervention from external factors outside the network (39).

The study exhibits limitations. The investigation employed convenience sampling from a single TCM university with an uneven gender ratio. Recruiting participants from different regions on a larger scale will be considered. Meanwhile, it is also a cross-sectional study, preventing examination of dynamic or causal relationships among symptoms. Future longitudinal studies should explore these relationships. In addition, the use of brief scales (PHQ-2 and GAD-7) may have limited the ability to capture the full spectrum of psychological symptoms. The study found that the effect between somatic symptoms and psychological symptoms was relatively weak, which may indicate that the actual effect is limited. Future intervention trials targeting central and bridging symptoms are needed to validate its effectiveness.

This work investigated the psychosomatic health status of college students of TCM, thereby establishing a network model of psychosomatic symptoms. Within the comorbid network, the centrality, bridging role, and predictability of symptoms were explored. We found that the psychosomatic health of these students is concerning, showing tendencies towards high levels of depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms. After comorbid network analysis, the symptoms of “ worrying too much about things “, “uncontrollable worries” and “weakness” were identified as central symptoms in the network model. Targeting these central symptoms for intervention could further relieve overall somatic presentations and reduce the severity of anxiety or depression. Simultaneously, interventions of targeting nodes with high predictability (“uncontrollable worry” and “ Worrying too much about things”) can be achieved by intervening in their adjacent nodes. Bridging symptoms (“ little interest or pleasure in doing things,” “ feeling down, depressed, or hopeless,” “ dyssomnia,” and “sighing”) can effectively prevent or alleviate the symptoms of comorbidity. This study will serve as a reference for psychosomatic health interventions among college students in TCM universities.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SY: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. XH: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Data curation, Conceptualization. CW: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. JG: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation. ZM: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. YZ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 7232298) and Central Universities Basic Research Business Fund Special Funding (Grant No.2024-JYB-KYPT-11).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deep appreciation to all of the individuals who contributed to this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1467064/full#supplementary-material

References

1. James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. (2018) 392:1789–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

2. Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Mussell M, Schellberg D, Kroenke K. Depression, anxiety and somatization in primary care: syndrome overlap and functional impairment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2008) 30:191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.01.001

3. Lipowski ZJ. Somatization: the concept and its clinical application. Am J Psychiatry. (1988) 145:1358–68. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.11.1358

4. de Waal MW, Arnold IA, Eekhof JA, van Hemert AM. Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. (2004) 184:470–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.6.470

5. Bener A, Al-Kazaz M, Ftouni D, Al-Harthy M, Dafeeah EE. Diagnostic overlap of depressive, anxiety, stress and somatoform disorders in primary care. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2013) 5:E29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-5872.2012.00215.x

6. Menkes DB, MacDonald JA. Interferons, serotonin and neurotoxicity. Psychol Med. (2000) 30:259–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291799001774

7. Hoehn-Saric R, McLeod DR, Funderburk F, Kowalski P. Somatic symptoms and physiologic responses in generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder: an ambulatory monitor study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2004) 61:913–21. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.913

8. Potrebny T, Wiium N, Lundegård MM. Temporal trends in adolescents' self-reported psychosomatic health complaints from 1980-2016: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. (2017) 12:e0188374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188374

9. Buli BG, Lehtinen-Jacks S, Larm P, Nilsson KW, Hellström-Olsson C, Giannotta F. Trends in psychosomatic symptoms among adolescents and the role of lifestyle factors. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:878. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18327-x

10. van Geelen SM, Hagquist C. Are the time trends in adolescent psychosomatic problems related to functional impairment in daily life? A 23-year study among 20,000 15-16year olds in Sweden. J Psychosom Res. (2016) 87:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.06.003

11. Li J, Luo C, Liu L, Huang A, Ma Z, Chen Y, et al. Depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms among Chinese college students: A network analysis across pandemic stages. J Affect Disord. (2024) 356:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.04.023

12. Kaiser T, Herzog P, Voderholzer U, Brakemeier EL. Unraveling the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in a large inpatient sample: Network analysis to examine bridge symptoms. Depress Anxiety. (2021) 38:307–17. doi: 10.1002/da.23136

13. Bringmann LF, Lemmens LH, Huibers MJ, Borsboom D, Tuerlinckx F. Revealing the dynamic network structure of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychol Med. (2015) 45:747–57. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001809

14. Luo J, Bei D-L, Zheng C, Jin J, Yao C, Zhao J, et al. The comorbid network characteristics of anxiety and depressive symptoms among Chinese college freshmen. BMC Psychiatry. (2024) 24:297. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-05733-z

15. Borsboom D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. (2017) 16:5–13. doi: 10.1002/wps.20375

16. Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, van der Maas HLJ, Borsboom D. Complex realities require complex theories: Refining and extending the network approach to mental disorders. Behav Brain Sci. (2010) 33:178–93. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X10000920

17. Guo Z, Yang T, He Y, Tian W, Wang C, Zhang Y, et al. The relationships between suicidal ideation, meaning in life, and affect: a network analysis. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2023), 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s11469-023-01019-9

18. Chen Z, Xiong J, Ma H, Hu Y, Bai J, Wu H, et al. Network analysis of depression and anxiety symptoms and their associations with mobile phone addiction among Chinese medical students during the late stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. SSM - Population Health. (2024) 25:101567. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101567

19. Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried EI. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods. (2018) 50:195–212. doi: 10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1

20. Jones PJ, Ma R, McNally RJ. Bridge centrality: A network approach to understanding comorbidity. Multivariate Behav Res. (2021) 56:353–67. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2019.1614898

21. Ke C, Chen Y, Ju Y, Xiao C, Li Y. Relationships between attitudes toward mental problems,doctor-patient relationships, and depression/anxiety levels in medical workers: A network analysis. J Cent South Univ (Med Sci). (2023) 48:1506–17. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2023.230115

22. Guo Z, Liang S, Ren L, Yang T, Qiu R, He Y, et al. Applying network analysis to understand the relationships between impulsivity and social media addiction and between impulsivity and problematic smartphone use. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:993328. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.993328

23. Yang T, Guo Z, Zhu X, Liu X, Guo Y. The interplay of personality traits, anxiety, and depression in Chinese college students: a network analysis. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1204285. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1204285

24. Liu X, Wang H, Zhu Z, Zhang L, Cao J, Zhang L, et al. Exploring bridge symptoms in HIV-positive people with comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:448. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04088-7

25. Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, Benjet C, Cuijpers P, et al. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. (2018) 127:623–38. doi: 10.1037/abn0000362

26. Gao L, Xie Y, Jia C, Wang W. Prevalence of depression among Chinese university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:15897. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72998-1

27. Wang X, Liu Q. Prevalence of anxiety symptoms among Chinese university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. (2022) 8:e10117. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10117

28. Xu H, Xiong H, Chen Y, Wang L, Liu T, Kang Y. A study of anxiety, depression and somatization symptoms and their influencing factors in undergraduate students of a comprehensive university. J Sichuan Univ (Medical Sciences). (2013) 44:669–72. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-4393.2002.02.011

29. Lin Z, Yu B. Psychological health status and its influential factors in medical students. J Guizhou Med Univ. (2001) 5:391–3.

30. Tang L, Deng H, Zhao Y, Wu H, Wei Y, Zhao Y, et al. Research on correlation between life events and physical health of university undergraduates. World Chin Med. (2013) 8:117–21.

31. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

32. He XY, Li CB, Qian J, Cui HS, Wu WY. Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety disorder scale in general hospital outpatients. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. (2010) 22:200–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2010.04.002

33. Tong X, An D, McGonigal A, Park SP, Zhou D. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. (2016) 120:31–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.11.019

34. Ni Z, Lebowitz ER, Zou Z, Wang H, Liu H, Shrestha R, et al. Response to the COVID-19 outbreak in urban settings in China. J Urban Health. (2021) 98:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00498-8

35. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. (2003) 41:1284–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

36. Levis B, Sun Y, He C, Wu Y, Krishnan A, Bhandari PM, et al. Accuracy of the PHQ-2 alone and in combination with the PHQ-9 for screening to detect major depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. (2020) 323:2290–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6504

37. Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, Borsboom D. Qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J Stat SOFTWARE. (2012) 48:367–71. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i04

38. Fruchterman TMJ, Reingold EM. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Software: Pract Exp. (1991) 21:1129–64. doi: 10.1002/spe.4380211102

39. Ren L, Wang Y, Wu L, Wei Z, Cui LB, Wei X, et al. Network structure of depression and anxiety symptoms in Chinese female nursing students. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:279. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03276-1

40. Cai H, Chow IHI, Lei S-M, Lok GKI, Su Z, Cheung T, et al. Inter-relationships of depressive and anxiety symptoms with suicidality among adolescents: A network perspective. J Affect Disord. (2023) 324:480–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.093

41. Robinaugh DJ, Millner AJ, McNally RJ. Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. J Abnorm Psychol. (2016) 125:747–57. doi: 10.1037/abn0000181

42. Haslbeck JMB, Waldorp LJ. How well do network models predict observations? On the importance of predictability in network models. Behav Res Methods. (2018) 50:853–61. doi: 10.3758/s13428-017-0910-x

43. Haslbeck JMB, Fried EI. How predictable are symptoms in psychopathological networks? A reanalysis of 18 published datasets. Psychol Med. (2017) 47:2767–76. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001258

44. Mao Y, Zhang N, Liu J, Zhu B, He R, Wang X. A systematic review of depression and anxiety in medical students in China. BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:327. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1744-2

45. Cai H, Bai W, Liu H, Chen X, Qi H, Liu R, et al. Network analysis of depressive and anxiety symptoms in adolescents during the later stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl Psychiatry. (2022) 12:98. doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-01838-9

46. Zhang Y, Cui Y, Li Y, Lu H, Huang H, Sui J, et al. Network analysis of depressive and anxiety symptoms in older Chinese adults with diabetes mellitus. Front Psychiatry. (2024) 15:1328857. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1328857

47. Jin Y, Sha S, Tian T, Wang Q, Liang S, Wang Z, et al. Network analysis of comorbid depression and anxiety and their associations with quality of life among clinicians in public hospitals during the late stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in China. J Affect Disord. (2022) 314:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.051

48. Tafet GE, Nemeroff CB. Pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders: the role of the HPA axis. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:443. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00443

49. Cai H, Bai W, Sha S, Zhang L, Chow IHI, Lei SM, et al. Identification of central symptoms in Internet addictions and depression among adolescents in Macau: A network analysis. J Affect Disord. (2022) 302:415–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.068

50. Haws JK, Brockdorf AN, Gratz KL, Messman TL, Tull MT, DiLillo D. Examining the associations between PTSD symptoms and aspects of emotion dysregulation through network analysis. J Anxiety Disord. (2022) 86:102536. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102536

51. Bai W, Xi HT, Zhu Q, Ji M, Zhang H, Yang BX, et al. Network analysis of anxiety and depressive symptoms among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. (2021) 294:753–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.072

52. Shimizu K, Kikuchi S, Kobayashi T, Kato S. Persistent complex bereavement disorder: clinical utility and classification of the category proposed for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. Psychogeriatrics. (2017) 17:17–24. doi: 10.1111/psyg.2017.17.issue-1

53. Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep. (2013) 36:1059–68. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2810

54. Cai H, Zhao YJ, Xing X, Tian T, Qian W, Liang S, et al. Network analysis of comorbid anxiety and insomnia among clinicians with depressive symptoms during the late stage of the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Nat Sci Sleep. (2022) 14:1351–62. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S367974

55. Liang S, Liu C, Rotaru K, Li K, Wei X, Yuan S, et al. The relations between emotion regulation, depression and anxiety among medical staff during the late stage of COVID-19 pandemic: a network analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2022) 317:114863. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114863

Keywords: college students, psychosomatic health, anxiety, depression, somatic symptoms, comorbidity, network analysis

Citation: Yi S, Hu X, Wang C, Ge J, Ma Z and Zhao Y (2024) Psychosomatic health status and corresponding comorbid network analysis of college students in traditional Chinese medicine schools. Front. Psychiatry 15:1467064. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1467064

Received: 19 July 2024; Accepted: 03 September 2024;

Published: 20 September 2024.

Edited by:

Steffen Schulz, Charité University Medicine Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Richa Tripathi, All India Institute of Medical Sciences Gorakhpur, IndiaCristian Ramos-Vera, Cesar Vallejo University, Peru

Copyright © 2024 Yi, Hu, Wang, Ge, Ma and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yan Zhao, eWFuemgzMjMyQDEyNi5jb20=

Shuang Yi

Shuang Yi Xingang Hu2

Xingang Hu2 Jieqian Ge

Jieqian Ge Yan Zhao

Yan Zhao