94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CLINICAL TRIAL article

Front. Psychiatry , 18 November 2024

Sec. Schizophrenia

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1457864

This article is part of the Research Topic Redefining Acute Psychiatric Care: Strategies for Improved Inpatient Experiences View all 6 articles

Rebekah Carney1,2*

Rebekah Carney1,2* Heather Law1

Heather Law1 Hany El-Metaal3

Hany El-Metaal3 Mark Hann4

Mark Hann4 Gemma Shields4

Gemma Shields4 Siobhan Savage3

Siobhan Savage3 Ingrid Small3

Ingrid Small3 Richard Jones3

Richard Jones3 David Shiers2,5,6

David Shiers2,5,6 Gillian Macafee1

Gillian Macafee1 Sophie Parker1,2

Sophie Parker1,2Background: People with severe mental illness experience physical health inequalities and a 15–20-year premature mortality rate. Forensic inpatients are particularly affected by restrictions on movement, long admissions, and obesogenic/sedative psychotropic medication. We aimed to establish the feasibility and acceptability of Motiv8, a multidisciplinary weight management intervention co-produced with service users for forensic inpatients.

Methods: A randomised waitlist-controlled trial of Motiv8(+Treatment-As-Usual) vs.TAU was conducted in medium-secure forensic services in Greater Manchester. Motiv8 is a 9-week programme of exercise sessions, diet/cooking classes, psychology, physical health/sleep education, and peer support. Physical and mental health assessments were conducted at baseline/10-weeks/3-months. A nested qualitative study captured participant experiences. A staff sub-study explored ward environment.

Results: We aimed to recruit 32 participants (four cohorts). The trial met recruitment targets (n=29, 90.9%; 4 cohorts, 100%), participants were randomised to Motiv8+TAU (n=12) or waitlist (control) (n=17). Acceptable retention rates were observed (93.1%, 10-weeks; 72.4%, 3-months), and participants engaged well with the intervention. The blind was maintained, and no safety concerns raised. Assessment completion was high suggesting acceptability (>90% for people retained and engaged in the study). Participants reported high levels of satisfaction.

Conclusions: The trial was not powered to detect group differences. However, data suggests it is feasible to conduct a rigorous, methodologically robust study of Motiv8 vs.TAU for adults on forensic inpatient units. Motiv8 was acceptable with potential promise providing evidence to proceed to a definitive trial for males. A larger trial is needed to explore potential effectiveness and reduce physical health inequalities for people with SMI.

Clinical trial registration: https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN13539285, identifier ISRCTN13539285.

People with Serious Mental Illness (SMI) experience physical health inequalities and a 15-20-year loss of life (1–3). This has been labelled a ‘national scandal’, leading to increased calls to action, such as the Lancet commission for physical healthcare, updated guidance from National Health Service England (top 10 priorities to improve the physical health of people living with SMI) and World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations (4–8). The Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2023) published updated prevalence rates showing compared with all patients, those with SMI have higher prevalence of obesity, asthma, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, hypertension and cancer. Individuals in forensic services are particularly vulnerable. Forensic psychiatric services have a dual purpose; to treat people who pose a risk to themselves or others and address offending behaviours. Approximately, 8000 people reside in forensic psychiatric services in the UK (9). Admissions usually exceed 5 years, and over 15 years for 20% of people (6, 10–12). Forensic psychiatric services receive a quarter of the mental health funding budget (13, 14), and physical comorbidities are a key predictor of total healthcare costs (15).

Obesity rates in forensic psychiatric services can reach 70%, and correlate with length of stay (16, 17). Cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes are more prevalent on secure units than generic inpatient units (16, 18, 19). People in forensic psychiatric services are more susceptible to risk-taking behaviours associated with high rates of adverse childhood experiences (20, 21). There are high rates of engagement with adverse health behaviours (e.g. sedentary activity) and polypharmacy of obesogenic and sedative psychotropic medication is common (22, 23). The ‘obesogenic’ nature of the inpatient environment also affords fewer opportunities to be active due to restrictions on movement, reduced access to outdoor spaces, and increased access to unhealthy foods (24).

WHO recommend increasing physical activity, reducing sedentary behaviour, and improving lifestyle to improve cardiometabolic health for people with SMI (25). Despite evidence showing physical health interventions benefit mental and physical health, well conducted studies in forensic settings are limited (26–30). An NHS-commissioned review identified only one weight management randomised controlled trial (RCT), along with several small uncontrolled studies (31, 32). Existing interventions often fail to include control groups, standardised outcome measures, and long-term follow-ups. There is often limited input from service users in intervention development, underrepresenting the ‘patient voice’, yet co-production is vital to increase sustainability and improve engagement (33).

We aim to address this evidence gap and explore the feasibility of Motiv8. Motiv8 is a 9-week multidisciplinary intervention which was co-developed, co-produced and co-facilitated with service users to improve cardiovascular health of people on forensic psychiatric units, (see (34) for further details). The primary aim is to conduct a randomised waitlist-controlled feasibility trial of Motiv8 vs.TAU for adults on forensic mental health units, to investigate the acceptability, feasibility, and potential effectiveness of Motiv8 to supplement standard care.

We conducted a prospective, single blind, cluster-randomised controlled feasibility trial with two conditions; Motiv8+treatment as usual (TAU), versus TAU+waitlist control (with Motiv8 delivered after TAU) (see Supplementary Materials for flow chart). The study took place in adult medium secure forensic mental health inpatient services at Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust (GMMH NHS FT). All authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Health Research Authority (HRA) London Bromley Research Ethics Committee [25th October 2021, 21/LO/0658, IRAS 299909]. It was prospectively registered on the ISRCTN registry [ISRCTN13539285]. The study protocol was published prior to study end (34). The trial was conducted and reported in line with the CONSORT extension to RCTs (35). An independent “Experts by Experience” group was established prior to study set-up and provided study oversight.

Participants were recruited from medium secure units at forensic services at GMMH NHS FT and were eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria.

● Adult inpatient (18+) of a medium secure unit at GMMH NHS FT.

● Mental health diagnosis requiring treatment from forensic psychiatric services.

● Capacity to provide informed consent.

● Physically able and medically safe to exercise (according to the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire).

● Inability to provide informed consent in line with ethical requirements.

● Previous Motiv8 participant.

● Insufficient command of English/communication difficulties preventing engagement in written informed consent, validity of research assessments or understanding of the programme.

Clinical leads of forensic services were consulted to identify potential wards. The research team liaised with clinical teams on wards to inform them of the study and provide details about inclusion criteria. Clinical teams approached patients to see if they were interested and obtain consent-to-contact. Researchers then arranged to meet with potential participants on the ward to discuss the study. A member of the research team had approvals to screen patient lists and identify potentially eligible participants.

All participants provided written informed consent prior to undertaking research procedures and completed a physical health risk assessment prior to engaging in Motiv8. We aimed to recruit 32 participants making up four cohorts, with a maximum of eight participants per cohort. This was due to pragmatic limitations associated with the need to keep groups small due to complex needs of service users requiring a set staff-to-patient ratio, and time/funding constraints. We aimed to recruit cohorts on a ward-by-ward basis, a decision based on previous consultations with people with lived experience as it was believed to avoid conflict between wards and meet COVID restrictions which prevented wards mixing. Eligible wards were required to have up to eight potential participants. This was not feasible for one cohort. Therefore, through discussions with the experts-by-experience group and service leads at the trust, participants from two wards were combined.

Participants were cluster randomised by cohort using the free web-based system (Sealed Envelope™, www.sealedenvelope.com) by a research administrator. Allocation was communicated to the chief investigator, study management, facilitators, and care teams of participating wards. Research assistants, the statistician and health economist remained blinded. Participants were informed of their randomisation outcome by letters sent to the wards, and clinicians who were informed by the administrator. Blinding remained in place until all outcome measures were collected and analysed. Measures to maintain blindness included separate offices and workspaces for facilitators and researchers, protocols for answering phones, secretarial support and separate secure drives to store password protected documents. The blind was successfully held.

Recruitment occurred at two timepoints (Dec 2021/July 2022) and two cohorts were recruited at each timepoint. Cohorts were randomised to receive Motiv8 straight away or placed on a waitlist to receive Motiv8 after the first follow-up timepoint. Motiv8 was provided along with TAU which was the usual provision of inpatient care for people with SMI and remained unchanged throughout the study. Assessments were conducted by trained, blinded researchers at baseline (pre-Motiv8/TAU), 10-weeks (post-Motiv8/TAU), and after another 12-weeks (TAU/waitlist Motiv8 (Supplementary Data Sheet 1). Demographics and clinical data were collected via self-report measures and researcher administered questionnaires.

Motiv8 is a 9-week intensive programme co-developed with service users to improve the cardiovascular and metabolic health of people on forensic inpatient units. It was developed with service users who were inpatients at the hospital and clinical teams. It aims to increase activity levels, improve diet, and use psychological guidance to maintain good physical health using goal-based techniques. It was delivered in groups to each cohort consecutively (the waitlist design meant all participants were offered Motiv8). Sessions took place in clinical areas in inpatient NHS facilities (e.g., ward or recovery academy kitchen, sports hall, meeting rooms and therapy rooms).

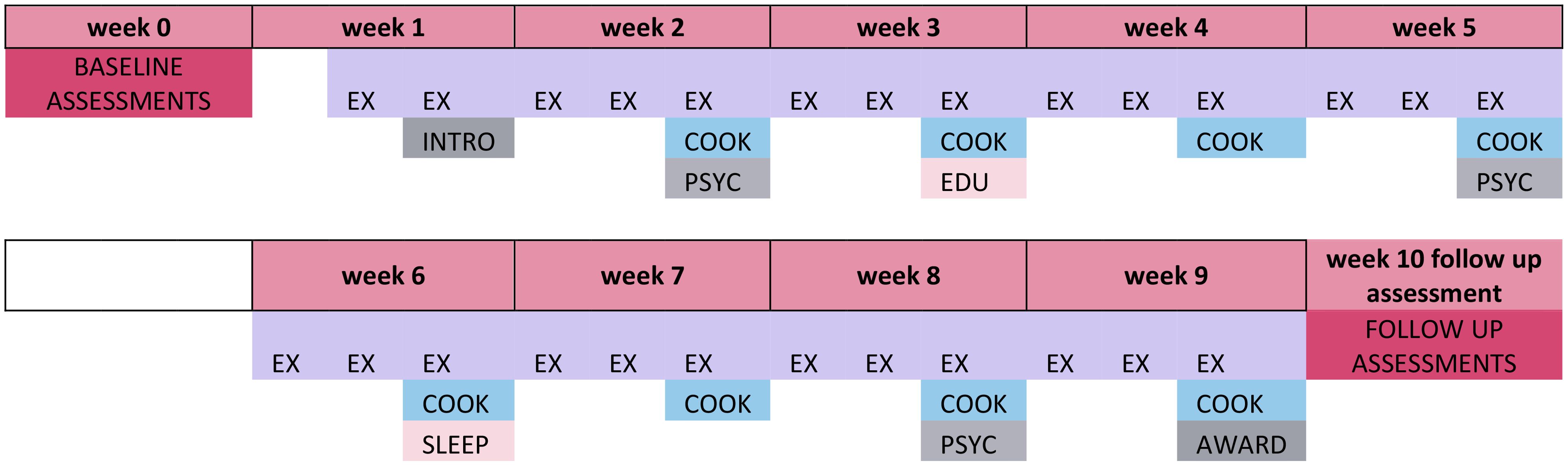

Motiv8 is multidisciplinary including several components to support physical health: exercise sessions, cooking/nutrition classes, physical health education, psychology sessions, sleep education, peer support and a medication review (See Figure 1; Table 1 for an example schedule). Motiv8 was facilitated and delivered by experienced occupational therapists, dietitians, psychologists, pharmacists, physicians, exercise and sport recreation workers, nurses, and peer mentors. Weekly supervisions were conducted internally, and intervention fidelity was monitored through regular meetings and paperwork. A person with lived experience co-facilitated and co-delivered sessions and provided peer support. An intervention booklet was created by the experts-by-experience group and research team which consisted of resources, activities and prompts for goal setting/review of progress. To increase morale, emphasis was placed on achievements and community, and participants attended an awards ceremony upon completion where they received a trophy, certificate, Motiv8 t-shirt, Motiv8 water bottle and voucher. Findings from successful pilot work across five cohorts (n=32) enabled Motiv8 to be iteratively updated with service user input and suggested that it may be feasible and beneficial for participants. [See https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3087194/v1 (34)].

Figure 1. Example schedule for Motiv8 intervention. INTRO, Introduction; EX, Exercise Sessions; COOK, Nutrition Sessions; EDU, Physical Health Education; PSYC, Psychology Sessions; SLEEP, Sleep Session; AWARD, Awards Session.

The primary aim was to assess the acceptability and feasibility of the trial and associated processes including the intervention and assessments. Key markers of feasibility included recruitment rates, follow-up retention rates, completion of clinical outcomes, and safety. Intervention acceptability was assessed via receiving a dose of the intervention, attendance, and adherence to the intervention, as well as subjective participant experiences and feedback from qualitative interviews. Participant interviews were analysed using in-depth qualitative methods and will be reported separately to provide a comprehensive, complete, and transparent account of our findings. The proposed primary outcome for a definitive trial was change in weight at 10-weeks/3-months. The study was not powered sufficiently to detect significant differences between groups and primary outcomes were to establish feasibility.

Clinical outcomes included a purpose-built form to collect basic sociodemographic information (e.g. ethnicity, gender, education status) and clinically relevant information (diagnoses, admission history, inpatient status, physical health conditions). Physical health measures included BMI, resting blood pressure, pulse rate, hip/waist/neck/chest circumference collected using disposable tape measures and recorded on a purpose-built questionnaire. To estimate cardiovascular fitness the six-minute walk (36) and standing jump test (37) were completed. Mental health outcomes included wellbeing [Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, WEMWEBS (38)], symptoms of depression and anxiety [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (39)] and negative symptoms [Scale of Negative Symptoms, SNS (40)]. Behavioural outcomes included physical and sedentary activity [Simple Physical Activity Questionnaire, SIMPAQ, (41)]; dietary intake (24-hour diet recall including time of consumption/portion size, (42); sleep quality and quantity [PROMIS Sleep Disturbance short form 8-item and PROMIS Sleep-Related Impairment short form 4-item (43)]; and smoking habits using a purpose-built demographics questionnaire developed from existing measures. Functioning was assessed through occupational therapy [Model of Human Occupational Screening Tool, (44)]. Outcomes to inform cost-effective analysis for a future study included health status [EQ-5D-5L, (45)], quality of life (Recovering Quality of Life, ReQoL (46), and medication side effects [Liverpool University Neuroleptic Side Effect Rating Scale, LUNSERS, (47)].

This feasibility study is not powered to test for intervention effectiveness therefore, our analyses are descriptive. The primary focus is on summaries of key indicators of success of the study (e.g. rates of recruitment, engagement, retention, and satisfaction). Following intention-to-treat principles, ‘logistics’ data is reported according to the CONSORT extension to RCTs (48) including: the number of prospective participants who were approached, subsequently deemed eligible and consented; the number of participants completing baseline questionnaires and who were randomised (by cohort); the number of participants who received their intended intervention and who were assessed at follow-up (including any reasons for loss to follow-up); the number of participants providing ‘complete’ clinical outcome data at each assessment.

Descriptive summaries of baseline demographic data are reported. For the latter, we present the median, the inter-quartile range and the data range due to the small numbers and likely skewness of each measure. We also present descriptive data on change in outcomes between baseline and week 10 for weight, WEMWBS and other clinical indicators of interest. As Motiv8 was delivered in cohorts, intra-cohort correlation will be present in the outcomes. A sample size calculation for a definitive trial will require an estimate of the intra-cohort correlation. Although such estimates have been calculated, the number of cohorts is likely to be too small here for them to be accurate.

This work was funded by the NIHR via the Research for Patient Benefit Programme (Grant Reference Number: RfPB NIHR201482). The funder had no input to the study design, delivery or interpretation of results, and the views expressed here are that of the authors.

Participants were recruited at two timepoints, December 2021/July 2022 and final follow up assessments were completed in December 2022. Four cohorts were successfully recruited (100% target) consisting of 29 participants (90.6% target). Forty potential participants were referred and a referral recruitment rate of 1.4:1 was observed (n=40 referrals). All referrals were screened, six were ineligible at referral (n=4, 10% not on eligible ward, n=2, 5% discharged before approached) and five declined when approached (12.5% referrals). 100% consented participants were randomised to either Motiv8 (n=12, 41.4%) or TAU+Waitlist Motiv8 (n=17, 58.6%). Participants were recruited from five medium secure treatment wards (4 male wards, 1 female ward). See Figure 2 for consort.

Retention to the trial was 93.1% (n=27) at 10-weeks and 72.4% (n=21) at 3-months which almost fulfilled progression criteria. The main reason for loss-to-follow up was driven by participants being discharged or moved to another trust (n=5, 17.2%). Lower retention rate at 3-months may have been caused by an unprecedented incident which occurred in the latter stage of the trial resulting in high staff turnover and rapid patient discharge. Additionally, retention was significantly lower in Cohort 3 and 4 (83.3%, n=10, 10-weeks; 58.3%, n=7, 3-months), compared with Cohort 1and 2 (100%, n=17, 10-weeks; 82.4%, n=14, 3-months). After six-months, contact was attempted with the first two cohorts, 11 participants were contacted (64.7%) and almost all said they would take part in assessments in a definitive trial (91%). Completion of the proposed primary outcome (weight) was high 96.6% (n=28, 10-weeks) and 95.2% (n=20, 3-months). High levels of acceptability were found for all measures (completion rate 93.3%-95.7%, 3-months). Retention rate per cohort is included in Supplementary Data Sheet 1.

The socio-demographics of participants are as follows. Participants were predominantly male (89.7%, n=25), White-British/White Other (75.9%, n=22), single (93.1%, n=27) and over half had been an inpatient for over five years (55.2%, n=16). See Table 2. Almost all participants (n=28, 96.5%) had a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum/psychosis related disorder and all were receiving medication, (93% antipsychotics, n=27). At baseline 85.7% (n=24) of participants were overweight or obese (median BMI 34.4, range 20.4-56.8). See Table 3. Full baseline characteristics will be published in detail elsewhere for completeness.

Motiv8 was delivered as planned for all four cohorts. Eight participants could form a cohort, the average amount of participants per cohort was seven. A total of 138 individual sessions were delivered during the trial. On average 33.5 sessions were delivered per cohort and varied for each component including on average 22 exercise sessions, 6.5 diet/nutrition sessions, 3 psychology sessions, 1 sleep session, 1 physical health session and 1 pharmacy review. Feedback from facilitators suggested high levels of confidence delivering sessions and the content, duration and frequency was appropriate.

All participants were offered Motiv8. 72.4% (n=21) started the intervention, uptake was lower in the waitlist group (n=11, 64.7%; vs. n=10, 83.3%), and the reasons for not starting were discharge/moving wards (n=6, 75%). For those starting the intervention, almost half attended more than 70% of sessions, one third attended 50-69% of sessions and 19% attended less than 50% of sessions, meeting amber progression criteria. Therefore, before progressing to a full definitive trial we will conduct further work with people with lived experience to identify ways to improve adherence, see (49). Reasons for non-attendance at individual sessions included participant declined (34%), no longer interested (28%), on leave (13%), discharged (11%), COVID (6%), unwell (4%) or sleeping (4%).

Since the primary aim was to establish feasibility, it was not sufficiently powered to reliably detect significant differences between groups, and secondary analyses are being conducted to explore any potential outcomes of promise for a definitive trial. See Supplementary Data Sheet 1 for some of the main clinical outcomes of interest.

Focused on informing future economic evaluation, two measures of health status were collected to estimate utility to calculate quality-adjusted life years (QALYS); a generic measure (EQ-5D-5L) and a mental health measure (ReQoL). Complete EQ-5D-5L data was available for 81% (baseline), 84% (10-weeks) and 58% (3-months). Utility could be estimated using the EQ-5D-5L for 55% of participants at all time-points. The mean EQ-5D-5L value at baseline was 0.732 (SD 0.243). As expected, this is lower than population norms (0.893, 35-44) (32). Estimating utility from ReQoL data uses a selection of the items available. Complete ReQoL-UI data was available for 68% (baseline), 84% (10-weeks) and 58% (3-months). Utility could be estimated using the ReQoL for 45% of participants at all time-points. The mean ReQoL-UI value at baseline was 0.846 (SD 0.146). Comparing the EQ-5D-5L and ReQoL derived utilities for participants with complete data for both at baseline, there is a notable difference (EQ-5D 0.767/ReQoL-UI 0.852). This aligns with findings from a larger study of people with schizophrenia (33). Therefore, further work is needed to validate the ReQoL-UI prior to a definitive trial.

Safety was assessed through tracking incidents and adverse events. Six adverse events occurred. This included participant injury/illness (n=3), one of which resulted in involuntary hospitalisation and two incidents of self-harm (n=2). An unprecedented incident occurred for the latter two cohorts, which resulted in rapid patient discharges and a high staff turnover. However, no adverse events or incidents were related to participation in the trial.

To our knowledge this is the first study of its kind to explore a multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention for adults on forensic inpatient units under randomised conditions. We provide evidence to suggest it is feasible and acceptable to conduct a rigorous, methodologically robust study comparing Motiv8+TAU with TAU. The trial met, (or almost met) all progression criteria including recruitment and randomisation to target and had acceptable retention levels and intervention uptake (49). Blinded conditions were maintained, and no safety concerns raised. This is despite challenging circumstances in which the study was delivered during the COVID-19 pandemic. The trial was not powered to reliably detect any significant differences between clinical outcomes; however, high levels of completion (generally above 90% for people retained and engaged in the study) suggest they are appropriate and acceptable for this population. Feedback from participants was positive and many benefits were reported after taking part (full qualitative and quantitative results are reported elsewhere for completeness).

Our work addresses several policy guidelines, including the WHO recommendations to manage physical health of people with SMI using lifestyle interventions, and the recent top ten priorities put forward by NHSE to improve the physical health of people with SMI (7, 50). Lifestyle interventions such as Motiv8 are non-invasive and non-stigmatising approaches to healthcare which may prevent the onset of comorbid physical health conditions and reduce the significant loss of life experienced by people with SMI. Our work meets standards from NHSE ‘Managing a healthy weight in adult secure services practice guidance’ which recommend service users should be supported to maintain a healthy weight by accessing multidisciplinary interventions, education, and support, which include service user involvement (51).

. This adds to previous research which has shown that physical health interventions are beneficial, and should form part of standardised care (4{England, 2017 #94)}. Additionally, a person with lived experience of forensic services co-delivered the intervention and received positive feedback. This highlights the benefits of peer support and how this can make a difference to research participants (52, 53). Peer support in forensic care is particularly important and has been found to aid recovery, community reintegration and quality of life. Further developmental work is underway to explore how this can be achieved and implemented in forensic care (54).

The sample was predominately male, and therefore, there is less confidence when suggesting feasibility for females. Previous research has shown distinct differences in clinical presentation, pathways to care, physical health needs and therapeutic approaches for females in forensic services (55–57). The research team experienced difficulties recruiting from female wards including scepticism from clinical teams, and disinterest from the women approached. Further developmental work is underway to establish the appropriateness of Motiv8 for female service users.

Additionally, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were set to allow trial feasibility to be established (e.g. assessing the appropriateness of study processes, written materials, written and verbal assessments and content). This, therefore, resulted in excluding people who did not have sufficient command of English or communication differences which prevented their ability to engage with assessments/group discussions. Forensic services have high rates of neurodiversity including co-morbid autism spectrum disorder and cognitive impairment affecting communication ability (58, 59). Therefore, necessary adaptations are required (such as translated or simplified materials, additional staff support) to allow for more inclusive practice, prior to implementation.

Motiv8 is a valuable contribution to the evidence base which seeks to address the physical health inequalities experienced by people with SMI. It is the first of its kind to be successfully delivered in forensic inpatient services according to a rigorous RCT protocol. The study was delivered as planned and met our original aims, despite challenging circumstances and COVID-19 restrictions. It is a complex multidisciplinary intervention which provides support above and beyond physical health. It was co-produced and co-delivered with significant user-input to ensure acceptability and appropriateness for the patient group, and this peer support was extremely well received. All participants had the chance to engage in the intervention and those who did reported high levels of satisfaction and enjoyment, resulting in immediate real-world impact.

Despite our promising findings, our sample was not wholly representative of the population served as we had a predominately white-male sample; therefore, a definitive trial should attempt to increase inclusivity and diversity. Additionally, there were important mitigating factors which made it difficult to ascertain what was true ‘feasibility’ and what was driven by the unprecedented incident which affected participation, (demonstrated by differences across cohorts). Cohort 1/2 maintained excellent recruitment, retention, and engagement with the intervention. However, Cohort 3/4 had substantially lower retention and attendance and increased loss to follow up. For example, 58.3% retention at 3 months (compared with 82.4% first cohorts) and average attendance was 40.6% of available sessions. Therefore, it is likely rapid discharges contributed to this, and latter cohorts may not represent true feasibility. Nevertheless, as the main reason for participant loss was discharge, it is important that in a definitive trial this factor is mitigated by identifying ways to allow continued participation if they are discharged. Finally, as the main aim of the study was to establish feasibility, the focus here was to present the overall feasibility outcomes of the trial. Therefore, data relating to outcomes and descriptors such as physical health indicators are reported separately to allow a complete and thorough discussion of their implications.

Given our positive findings, a larger trial is needed to understand the potential benefits and cost-effectiveness of Motiv8. A future trial may also identify potential mechanisms of action and methods of implementation to enhance care provision. Due to the low numbers of female participants, further developmental work is needed with user and clinician input to refine and determine feasibility for female wards. Additionally, further developmental work should be done to account for the impact of the unprecedented incident at the trust, and to ascertain “true” follow-up and attendance rates.

To conclude, the data provides evidence that the trial is appropriate, feasible and acceptable for patients on forensic inpatient services. Our study provides health providers, commissioners, policy makers, service users and researchers with valuable data regarding evidence-based interventions to enhance physical and mental wellbeing for adults on forensic inpatient services. Further developmental work is needed to create a definitive application to explore the cost-effectiveness and clinical utility of Motiv8 as an adjunct to usual care in NHS services. If Motiv8 is found to result in clinically meaningful changes and prove cost-effective it will have a significant impact on service development, with a view to be incorporated in NICE guidelines.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of the article are not readily as it contains sensitive information. Requests to access the data should be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The studies involving humans were approved byHealth Research Authority London Bromley Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

RC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HL: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HE: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. GS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. IS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. RJ: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DS: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. GM: Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. SP: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. National Institute for Health and Care Research, Research for Patient Benefit (Reference Number NIHR201482).

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the experts by experience group who were invaluable in supporting and advising on research materials and procedures throughout and after the trial. We extend particular appreciation for our primary lived experience consultant James who was integral to this work. We acknowledge the efforts and support of the clinical teams at Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust. We specifically thank James Ryan, Douglas Ainsworth and Lisa Nuttall who facilitated Motiv8 sessions and were invaluable to the running of the intervention. We would like to acknowledge Andrew Macdonald who provided input during the early stages of the trial. We acknowledge Onagh Boyle and Hannah Poloczek for their support and expertise with pharmacy. Additionally, we would like to thank Kyriakos Velemis for his hard-work and dedication with data analysis and cleaning.

DS is an expert advisor for the NICE centre for guidelines; views expressed are those of the authors and not NICE.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1457864/full#supplementary-material

1. De Hert M, Schreurs V, Vancampfort D, Van Winkel R. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: a review. World Psychiatry. (2009) 8:15. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00199.x

2. Correll CU, Solmi M, Veronese N, Bortolato B, Rosson S, Santonastaso P, et al. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: a large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry. (2017) 16:163–80. doi: 10.1002/wps.20420

3. Brown S, Kim M, Mitchell C, Inskip H. Twenty-five year mortality of a community cohort with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. (2010) 196:116–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067512

4. Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, Siskind D, Rosenbaum S, Galletly C, et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:675–712. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30132-4

5. England PH. Health matters: reducing health inequalities in mental illness. Public Health England: GOV UK (2018). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-reducing-health-inequalities-in-mental-illness/health-matters-reducing-health-inequalities-in-mental-illness.

6. England PH. Working together to address obesity in adult mental health secure units A systematic review of the evidence and a summary of the implications for practice. Public Heal Engl. (2017). Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7f1b63ed915d74e62286c9/obesity_in_mental_health_secure_units.pdf.

7. Shiers D, Bradshaw T, Campion J. Health inequalities and psychosis: time for action. Br J Psychiatry. (2015) 207:471–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.152595

8. Thornicroft G. Physical health disparities and mental illness: the scandal of premature mortality. Br J Psychiatry. (2011) 199:441–2. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092718

9. Tully J, Hafferty J, Whiting D, Dean K, Fazel S. Forensic mental health: envisioning a more empirical future. Lancet Psychiatry. (2024). doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(24)00164-0

10. Commission CQ. Monitoring the mental health act in 2015/2016. Care Qual Commission. (2016) 2022. Available online at: https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20161122_mhareport1516_web.pdf.

11. Davoren M, Byrne O, O’Connell P, O’Neill H, O’Reilly K, Kennedy HG. Factors affecting length of stay in forensic hospital setting: need for therapeutic security and course of admission. BMC Psychiatry. (2015) 15:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0686-4

12. Hare Duke L, Furtado V, Guo B, Völlm BA. Long-stay in forensic-psychiatric care in the UK. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2018) 53:313–21. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1473-y

14. McInerny T, Minne C. Principles of treatment for mentally disordered offenders. Crim Behav Ment Health S43. (2004) 14:s43–7. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1471-2857

15. Ride J, Kasteridis P, Gutacker N, Aragon Aragon MJ, Jacobs R. Healthcare costs for people with serious mental illness in England: an analysis of costs across primary care, hospital care, and specialist mental healthcare. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. (2020) 18:177–88. doi: 10.1007/s40258-019-00530-2

16. Haw C, Rowell A. Obesity and its complications: a survey of inpatients at a secure psychiatric hospital. Br J Forensic Pract. (2011) 13:270–7. doi: 10.1108/14636641111190033

17. Meiklejohn C, Sanders K, Butler S. Physical health care in medium secure services. Nurs Standard (through 2013). (2003) 17:33. doi: 10.7748/ns.17.17.33.s55

18. Moss K, Meurk C, Steele ML, Heffernan E. The physical health and activity of patients under forensic psychiatric care: A scoping review. Int J Forensic Ment Health. (2022) 21:194–209. doi: 10.1080/14999013.2021.1943570

19. Johnson M, Day M, Moholkar R, Gilluley P, Goyder E. Tackling obesity in mental health secure units: a mixed method synthesis of available evidence. BJPsych Open. (2018) 4:294–301. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2018.26

20. Stinson JD, Quinn MA, Menditto AA, LeMay CC. Adverse childhood experiences and the onset of aggression and criminality in a forensic inpatient sample. Int J Forensic Ment Health. (2021) 20:374–85. doi: 10.1080/14999013.2021.1895375

21. Pedersen ALW, Lindekilde CR, Andersen K, Hjorth P, Gildberg FA. Health behaviours of forensic mental health service users, in relation to smoking, alcohol consumption, dietary behaviours and physical activity—A mixed methods systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2021) 28:444–61. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12688

22. Vancampfort D, Correll CU, Galling B, Probst M, De Hert M, Ward PB, et al. Diabetes mellitus in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and large scale meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. (2016) 15:166–74. doi: 10.1002/wps.20309

23. Vancampfort D, Firth J, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Mugisha J, Hallgren M, et al. Sedentary behaviour and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. (2017) 16:308–15. doi: 10.1002/wps.20458

24. Faulkner GE, Gorczynski PF, Cohn TA. Psychiatric illness and obesity: recognizing the” obesogenic” nature of an inpatient psychiatric setting. Psychiatr Serv. (2009) 60:538–41. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.538

25. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. (2020) 54:1451–62. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

26. Ashdown-Franks G, Firth J, Carney R, Carvalho AF, Hallgren M, Koyanagi A, et al. Exercise as medicine for mental and substance use disorders: a meta-review of the benefits for neuropsychiatric and cognitive outcomes. Sports Med. (2020) 50:151–70. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01187-6

27. Czosnek L, Lederman O, Cormie P, Zopf E, Stubbs B, Rosenbaum S. Health benefits, safety and cost of physical activity interventions for mental health conditions: A meta-review to inform translation efforts. Ment Health Phys Activity. (2019) 16:140–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2018.11.001

28. Teasdale SB, Ward PB, Rosenbaum S, Samaras K, Stubbs B. Solving a weighty problem: systematic review and meta-analysis of nutrition interventions in severe mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. (2017) 210:110–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177139

29. Bonfioli E, Mazzi MA, Berti L, Burti L. Physical health promotion in patients with functional psychoses receiving community psychiatric services: Results of the PHYSICO-DSM-VR study. Schizophr Res. (2018) 193:406–11. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.017

30. Long C, Rowell A, Rigg S, Livesey F, McAllister P. What is effective in promoting a healthy lifestyle in secure psychiatric settings? A review of the evidence for an integrated programme that targets modifiable health risk behaviours. J Forensic Pract. (2016) 18:204–15. doi: 10.1108/JFP-12-2015-0055

31. Bacon N, Farnworth L, Boyd R. The use of the Wii Fit in forensic mental health: exercise for people at risk of obesity. Br J Occup Ther. (2012) 75:61–8. doi: 10.4276/030802212X13286281650992

32. Prebble K, Kidd J, O’Brien A, Carlyle D, McKenna B, Crowe M, et al. Implementing and maintaining nurse-led healthy living programs in forensic inpatient settings: an illustrative case study. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. (2011) 17:127–38. doi: 10.1177/1078390311399094

33. Mateo-Urdiales A, Michael M, Simpson C, Beenstock J. Evaluation of a participatory approach to improve healthy eating and physical activity in a secure mental health setting. J Public Ment Health. (2020) 19:301–9. doi: 10.1108/JPMH-11-2019-0090

34. Carney R, El-Metaal H, Law H, Savage S, Small I, Hann M, et al. Motiv8: a study protocol for a cluster-randomised feasibility trial of a weight management intervention for adults with severe mental illness in secure forensic services. Pilot Feasib Stud. (2024) 10:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40814-024-01458-8

35. Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. Bmj. (2012) 345:1–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5661

36. Enright PL. The six-minute walk test. Respir Care. (2003) 48:783–5. Available online at: https://rc.rcjournal.com/content/48/8/783/tab-pdf.

37. Bui HT, Farinas MI, Fortin AM, Comtois AS, Leone M. Comparison and analysis of three different methods to evaluate vertical jump height. Clin Physiol Funct Imag. (2015) 35:203–9. doi: 10.1111/cpf.2015.35.issue-3

38. Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, Weich S, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2007) 5:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63

39. Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2003) 1:1–4. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-29

40. Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br J Psychiatry. (1989) 155:49–52. doi: 10.1192/S0007125000291496

41. Rosenbaum S, Ward PB. The simple physical activity questionnaire. Lancet Psychiatry. (2016) 3:e1. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00496-4

43. Yu L, Buysse DJ, Germain A, Moul DE, Stover A, Dodds NE, et al. Development of short forms from the PROMIS™ sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment item banks. Behav Sleep Med. (2012) 10:6–24. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2012.636266

44. Kielhofner G, Fan C-W, Morley M, Garnham M, Heasman D, Forsyth K, et al. A psychometric study of the Model of Human Occupation Screening Tool (MOHOST). Hong Kong J Occup Ther. (2010) 20:63–70. doi: 10.1016/S1569-18611170005-5

45. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen MF, Kind P, Parkin D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. (2011) 20:1727–36. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x

46. Keetharuth AD, Brazier J, Connell J, Bjorner JB, Carlton J, Buck ET, et al. Recovering Quality of Life (ReQoL): a new generic self-reported outcome measure for use with people experiencing mental health difficulties. Br J Psychiatry. (2018) 212:42–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2017.10

47. Morrison P, Gaskill D, Meehan T, Lunney P, Lawrence G, Collings P. The use of the Liverpool University neuroleptic side-effect rating scale (LUNSERS) in clinical practice. Aust New Z J Ment Health Nurs. (2000) 9:166–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0979.2000.00181.x

48. Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, Bond CM, Hopewell S, Thabane L, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. bmj. (2016) 355:1–29. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5239

49. Avery KN, Williamson PR, Gamble C, Francischetto EOC, Metcalfe C, Davidson P, et al. Informing efficient randomised controlled trials: exploration of challenges in developing progression criteria for internal pilot studies. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013537. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013537

50. England N. Improving the physical health of people living with severe mental illness. NHS England (2024).

51. England PH. Managing a healthy weight in adult secure services – practice guidance. Public Health England (2021).

52. Smit D, Miguel C, Vrijsen JN, Groeneweg B, Spijker J, Cuijpers P. The effectiveness of peer support for individuals with mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. psychol Med. (2023) 53:5332–41. doi: 10.1017/S0033291722002422

53. Mutschler C, Bellamy C, Davidson L, Lichtenstein S, Kidd S. Implementation of peer support in mental health services: A systematic review of the literature. Educ Publishing Foundation;. (2022) 19(2):360–74. doi: 10.1037/ser0000531

54. Hardy SC, Alves-Costa F, Robinson G. Peer support-led interventions in forensic settings: listening to service users and peer support worker’ Perceptions and experiences. J Forensic Psychol Res Pract. (2023) 24(5):1–23. doi: 10.1080/24732850.2023.2251446

55. Archer M, Lau Y, Sethi F. Women in acute psychiatric units, their characteristics and needs: a review. BJPsych Bull. (2016) 40:266–72. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.115.051573

56. Bartlett A, Somers N. Are women really difficult? Challenges and solutions in the care of women in secure services. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. (2017) 28:226–41. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2016.1244281

57. Coid J, Kahtan N, Gault S, Jarman B. Women admitted to secure forensic psychiatry services: I. Comparison of women and men. J Forensic Psychiatry. (2000) 11:275–95. doi: 10.1080/09585180050142525

58. Tromans S, Chester V, Kiani R, Alexander R, Brugha T. The prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in adult psychiatric inpatients: a systematic review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health: CP EMH. (2018) 14:177. doi: 10.2174/1745017901814010177

Keywords: secure services, forensic, physical health, multidisciplinary, lifestyle intervention, randomised controlled trial

Citation: Carney R, Law H, El-Metaal H, Hann M, Shields G, Savage S, Small I, Jones R, Shiers D, Macafee G and Parker S (2024) A multidisciplinary weight management intervention for adults with severe mental illness in forensic psychiatric inpatient services (Motiv8): a single blind cluster-randomised wait-list controlled feasibility trial. Front. Psychiatry 15:1457864. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1457864

Received: 01 July 2024; Accepted: 28 October 2024;

Published: 18 November 2024.

Edited by:

Gretchen L. Haas, University of Pittsburgh, United StatesReviewed by:

Peter Andiné, University of Gothenburg, SwedenCopyright © 2024 Carney, Law, El-Metaal, Hann, Shields, Savage, Small, Jones, Shiers, Macafee and Parker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rebekah Carney, UmViZWthaC5jYXJuZXlAZ21taC5uaHMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.