- 1Institute of Basic Research in Clinical Medicine, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing, China

- 2Beijing Key Laboratory of Applied Experimental Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, National Demonstration Center for Experimental Psychology Education, National Virtual Simulation Center for Experimental Psychology Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 3Business School, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 4Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Beijing Normal University at Zhuhai, Zhuhai, China

Introduction: The relationship between rumination and depressive symptoms has been extensively studied over the past two decades. However, few studies have explored how rumination contributes to depressive symptoms within the context of heterogeneous romantic relationships, particularly regarding potential gender differences in these effects. The present study aims to investigate whether rumination is related to four key factors of depressive symptoms (i.e., depressed affect, positive affect, somatic and retarded activity, interpersonal distress) both on the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels among young couples.

Methods: Participants were 148 Chinese young couples (N = 296; males: M age = 21.94 years, SD = 2.40 years; females: M age = 21.62 years, SD = 2.26 years). Couples completed self-reported questionnaires assessing rumination and depressive symptoms separately, using the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).

Results: The results of a series of actor-partner interdependence models (APIM) showed that, on the intrapersonal level, rumination was positively and significantly associated with an individual’s own depressed affect, somatic and retarded activity, and interpersonal distress. On the interpersonal level, higher levels of rumination in males were associated with increased depressed affect and interpersonal distress in their female partners. However, no such partner effect was observed for male partners of ruminative females.

Conclusions: These findings suggest that females in romantic relationships, as compared to males, may be more susceptible to the influence of their male partners’ rumination. This study is among the firsts to demonstrate the gender-specific effect in the relationship between rumination and depressive symptoms in young couples.

1 Introduction

In recent years, research on the association between rumination and depressive symptoms has expanded significantly (1–3), largely due to the critical role rumination plays in understanding mental health outcomes, particularly depression (4–7). While many studies have examined the relationship between rumination and depressive symptoms at the individual (intrapersonal) level (1, 2), few have adopted a comprehensive perspective or explored these associations within romantic relationships. Moreover, whether rumination affects depressive symptoms differently based on gender within heterosexual romantic relationships remains uncertain. This study aims to enhance our understanding of rumination by examining its influence on both an individual’s own depressive symptoms and those of their partner in young heterosexual couples, as well as investigating potential gender differences in these relationships.

1.1 Rumination and depressive symptoms

According to response styles theory (8), rumination is defined as a response style involving a repeated focus on self-related negative feelings during times of distress. Individuals with a ruminative response style dwell on thoughts and behaviors related to the potential causes, meanings, and consequences of their distressed feelings (2, 6). Extensive evidence links rumination with various adverse outcomes, including negative thinking (9), anxiety (10), and post-traumatic stress symptoms (11).

In addition to these negative impacts, rumination has been strongly and consistently associated with depressive symptoms (1, 2). Radloff (12) proposed four major aspects of depressive symptoms: (1) depressed affect, including feelings of worthlessness, helplessness, and hopelessness; (2) somatic and retarded activity, such as loss of appetite and sleep disturbances; (3) absence of positive affect, including diminished feelings of hope, happiness, or enjoyment; and (4) interpersonal distress, characterized by feelings of being unfriendly and disliked. Increased rumination has been found to be associated with each of these aspects of depressive symptoms, including greater depressed affect (1) and higher somatic and retarded activity, such as a reduced ability and motivation to develop effective plans and behaviors for managing problems (13, 14). Regarding interpersonal distress, adolescents and adults who are depressed tend to ruminate more, particularly on stressors involving interpersonal issues (15, 16). However, findings on the association between rumination and positive affect have been mixed. Some studies indicate that engaging in rumination reduces positive affect (17, 18), while others report no significant correlation between rumination and positive affect (19). Therefore, further studies are recommended to clarify the relationships between rumination and different aspects of depressive symptoms, especially the absence of positive affect.

1.2 The role of gender

Gender differences in rumination are widely noted, with researchers suggesting that females are more likely than males to ruminate when feeling sad or depressed (20–22). Several explanations have been proposed for why females may be more prone to rumination. First, socialization processes may encourage females to be more emotionally expressive and introspective, leading them to focus more intensely on their emotional experiences, which can promote ruminative thinking (23). For example, Zimmermann and Iwanski (24) argued that females are often socialized to be more attuned to their emotions, and this heightened focus on internal experiences can increase the likelihood of rumination, particularly during emotional distress. Additionally, females may find it more challenging to alleviate negative emotions, making them more susceptible to rumination as they work to process and regulate these feelings (7). Another explanation is females’ tendency to feel responsible for the emotional climate of their relationships, which increases their sensitivity to partners’ behaviors and comments (25, 26). This heightened relational awareness can make females more vigilant in detecting potential interpersonal conflicts or negative cues, potentially leading to rumination. Given the gender disparity in rumination, it is important to understand whether rumination is equally related to depressive symptoms for both males and females.

1.3 Rumination in romantic relationship

Recent studies have increasingly focused on rumination and its detrimental effects within romantic relationships (5, 27). For instance, Verhallen et al. (28) examined depressive symptom trajectories following relationship breakups and assessed the impact of rumination impact on these trajectories. They found that individuals with higher levels of rumination experienced more severe depressive symptoms post-breakup, underscoring how rumination amplifies distress in romantic contexts. Additionally, Horn et al. (27) studied couples transitioning to retirement and explored rumination’s impact on their daily adjustment. They observed that on days with elevated rumination, couples reported greater communication difficulties, particularly in understanding the retiree’s disclosures, and experienced more negative emotions. While these studies provide valuable insights, they are limited to specific adult samples, such as couples post-breakup or retirees, and thus leave a gap in understanding how rumination impacts couples in more general populations.

In the limited studies that have examined rumination patterns among general couples, findings consistently indicate that females are more likely than males to engage in rumination (29, 30). For example, Bastin et al. (29) found that adolescent females engaged in co-rumination more frequently than males, which was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. This tendency may partly stem from females’ enhanced social perspective-taking abilities, a skill that supports relationship quality but can also lead to empathetic distress in emotionally charged situations (31). Focusing specifically on young couples, the impact of rumination on depression becomes particularly important due to the central role that romantic relationships play in their psychological development. Romantic relationships during early adulthood are characterized by emotional intensity and identity formation, and difficulties within these relationships can significantly affect mental health (32). For instance, young couples may experience heightened emotional reactivity to their partner’s ruminative thoughts, which could exacerbate depressive symptoms. Research indicates that higher levels of rumination not only affect individuals directly but can also contribute to stress and emotional strain within the relationship (28).

While studies have shown that women are more likely to co-ruminate, limited empirical research has directly examined how a partner’s rumination affects both their own and their partner’s depressive symptoms. Moreover, little is known about whether these relationships differ according to the gender of the couples involved. Given the significant role of romantic relationships in the mental health of young adults (28, 32), more research is needed to explore the association between rumination and depressive symptoms among young couples and to determine whether gender differences exist in these relationships.

1.4 Advantages of dyadic analysis

To explore the impact of individuals’ rumination on both their own (i.e., intrapersonal) and their partner’s (i.e., interpersonal) depressive symptoms, we employed the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM). The APIM is particularly advantageous for analyzing dyadic data, as it treats the dyad as the unit of analysis, thus accounting for the non-independence of data that naturally arises in close relationships (33). By examining both the “actor effect” (the impact of an individual’s rumination on their own depressive symptoms) and the “partner effect” (the impact of an individual’s rumination on their partner’s depressive symptoms), the APIM enables us to distinguish between intrapersonal and interpersonal influences within the dyadic context, making it well-suited for understanding mutual influences within couples. Due to this advantage, the APIM has become a popular approach in studies of dyadic interactions (34). In the context of our study, using the APIM allows us to examine how one partner’s rumination might resonate within the relationship, potentially impacting the mental health of both partners. This approach supports a comprehensive analysis of the reciprocal influences in couple dynamics, offering valuable insights into how psychological processes like rumination function within intimate relationships.

1.5 Current study

Our study is one of the firsts to explore the relationship between rumination and depressive symptoms at both interpersonal and interpersonal levels in Chinese young couples. Specifically, we aim to investigate how an individual’s rumination is associated with their own and their partner’s various dimensions of depressive symptoms (i.e., depressed affect, positive affect, somatic and retarded activity, and interpersonal distress) and to explore whether there were gender differences in these relationships. Based on theoretical considerations, we hypothesized that rumination would be positively associated with both an individual’s own and their partner’s depressive symptoms across all four dimensions. Moreover, we proposed that females might be more susceptible to the influence of their male partner’s ruminative thoughts in relation to their own depressive symptoms.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

Data were drawn from a study on romantic relationships and psychological well-being among young heterosexual couples. Participants were recruited via flyers posted in the local community. Eligibility criteria required that participants be in a romantic relationship for at least three months, have no clinical diagnosis of psychological disorders (e.g., depression), and not be taking any medication related to mental health. A total of 163 heterosexual couples (N = 326) initially agreed to participate. However, nine couples were excluded due to incomplete assessments, and three additional couples were excluded because of technical issues. This resulted in a final sample of 151 couples (N = 302). Male participants ranged in age from 17 to 33 years (M age = 21.94 years, SD = 2.40 years), while female participants ranged from 18 to 27 years (M age = 21.62 years, SD = 2.26 years). The couples had been in their romantic relationship for an average of 25.64 months (SD = 21.19 months, range = 3-96 months).

2.2 Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Upon arrival at our laboratory, all participants provided written informed consent. They then completed a series of questionnaires, including demographic information, rumination, and depressive symptoms. The entire procedure took approximately one hour. Each couple received 150 RMB (approximately 20 USD) as compensation for their participation.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Rumination

The ruminative response style in couples was assessed using the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS; 35). The RRS comprises 22 items that assess an individual’s tendency to ruminate in response to sad moods. Participants rate the frequency of their use of ruminative strategies on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = almost never to 4 = almost always), with higher scores indicating a stronger ruminative response style. The original RRS demonstrated good internal consistency (35), and the Chinese version has also showed strong reliability and validity (36). In this study, the RRS exhibited excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α = .920 for males and α = .925 for females.

2.3.2 Depressive symptoms

Couples’ depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; 12). The CES-D consists of 20 items and includes four subscales: depressed affect (e.g., “I felt that I could not shake off the blues even with help from my family or friends”), positive affect (e.g., “I felt that I was just as good as other people”), somatic and retarded activity (e.g., “I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor”), and interpersonal distress (e.g., “People were unfriendly”). The Chinese version of the CES-D has shown good psychometric properties (36). In the current study, we calculated internal consistency reliability separately for males and females. The reliability for each CES-D subscale was acceptable: Cronbach’s α for the depressed affect subscale was.827 for males and.874 for females; for the positive affect subscale,.696 for males and.732 for females; for the somatic and retarded activity subscale,.687 for males and.721 for females; and for the interpersonal distress subscale,.640 for males and.671 for females.

2.4 Data analysis

In the preliminary analyses, we conducted descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analyses for the study variables. In dyadic data analysis, non-independence refers to the interdependence of variables within a couple, where one partner’s characteristics or behaviors may affect the other’s (33). Recognizing this interdependence is essential, as it supports treating the dyad as a single unit in statistical models like APIM. To confirm non-independence in our study, we examined correlations between males and females on the same variables, specifically rumination and the four dimensions of depressive symptoms. Significant correlations would indicate non-independence, justifying the use of APIM for further analysis.

Subsequently, we conducted four APIM models to investigate the effects of males’ and females’ rumination on both their own and their partner’s depressed affect, positive affect, somatic and retarded activity, and interpersonal distress, using Analysis of Moment Structures (Amos) version 20.0 software. Given that participant age and relationship duration could influence the observed relationships, we included these variables as covariates in the models. We analyzed the dyad as a unit and used a 95% confidence interval (CI) based on 5,000 bootstrap samples to assess the significance of actor effects (the influence of an individual’s rumination on their own depressive symptoms) and partner effects (the influence of an individual’s rumination on their partner’s depressive symptoms). Unstandardized coefficients were reported in accordance with recommendations from Kenny et al. (33).

3 Results

3.1 Preliminary analyses

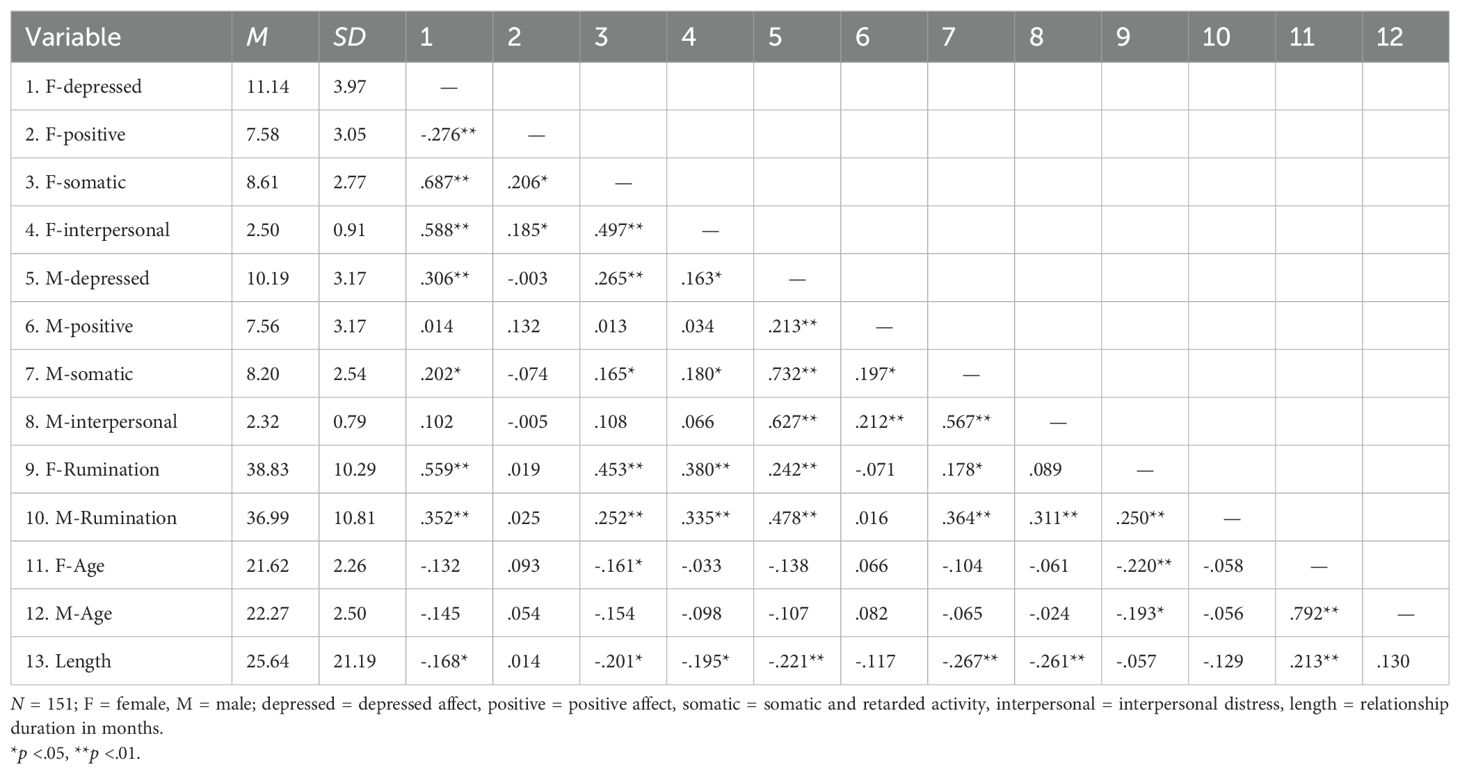

The descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations are presented in Table 1. Both females’ and males’ rumination were significantly and positively associated with their own depressed affect, somatic and retarded activity, and interpersonal distress (p-values <.05). Additionally, females’ depressed affect was positively correlated with males’ depressed affect (r = .306, p <.001), and females’ somatic and retarded activity was positively correlated with males’ somatic and retarded activity (r = .165, p = .043). There was also a positive correlation between females’ and males’ rumination (r = .250, p = .002). These results suggest a non-independence of study variables within couples.

Moreover, females’ rumination was significantly and positively associated with males’ depressed affect (r = .242, p = .003) and somatic and retarded activity (r = .178, p = .029). Similarly, males’ rumination was significantly and positively correlated with females’ depressed affect (r = .352, p <.001), somatic and retarded activity (r = .252, p = .002), and interpersonal distress (r = .335, p <.001).

Finally, a series of paired-sample t-tests were conducted to assess potential gender differences in the key study variables. The results indicated a significant difference in depressed affect between females and males (t (150) = 2.733, p = .007). However, there were no significant gender differences in rumination (t (150) = 1.744, p = .083), positive affect (t (150) = 0.040, p = .968), somatic and retarded activity (t (150) = 1.470, p = .144), or interpersonal distress (t (150) = 1.883, p = .062).

3.2 APIM models

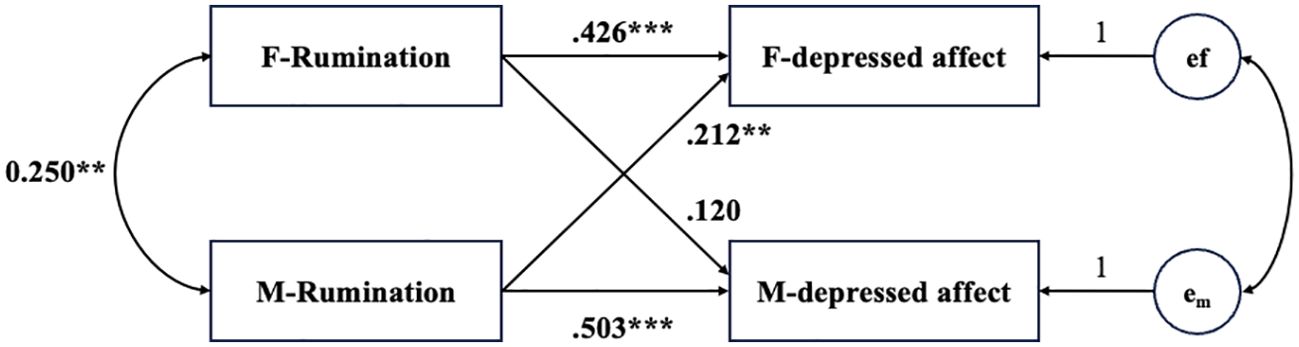

For the model with couples’ depressed affect as the outcome variables, the model fit the data well, χ²(2) = 1.09, p = .58, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .001. Regarding the actor effect (see Figure 1), the results indicated that both males’ and females’ rumination were positively associated with their own depressed affect (females: β = .426, p <.001; males: β = .503, p <.001). For the partner effect (see Figure 1), higher levels of rumination in males were positively correlated with higher levels of depressed affect in their female partners (β = .212, p = .001), while females’ rumination was not significantly associated with their male partners’ depressed affect (β = .120, p = .100). Additionally, for the covariate effects, relationship duration was negatively associated with males’ depressed affect, but it was not correlated with females’ depressed affect. Participant age did not correlate with either males’ or females’ depressed affect.

Figure 1. Actor–partner interdependence model predicting depressed affect from rumination. ef and em represent the error terms of depression of female and male. Participant age and relationship duration were controlled for in the model, but are not displayed in the figure for simplicity. **p <.01, ***p <.001.

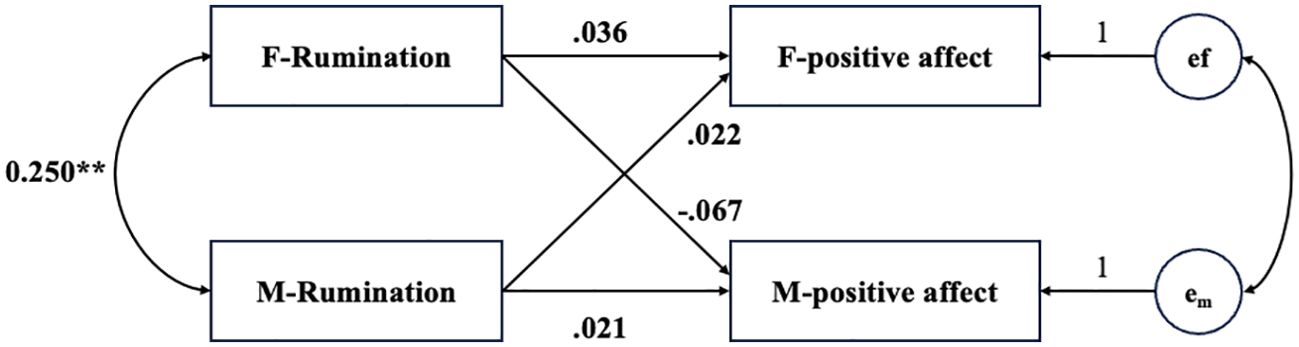

For the model with couples’ positive affect as the outcome variables, the model fit the data well, χ²(2) = 1.93, p = .91, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .001. As shown in Figure 2, the results showed that neither males’ nor females’ rumination was significantly associated with their own positive affect, nor was it correlated with their partner’s positive affect.

Figure 2. Actor–partner interdependence model predicting positive affect from rumination. ef and em represent the error terms of positive affect of female and male. Participant age and relationship duration were controlled for in the model, but are not displayed in the figure for simplicity.

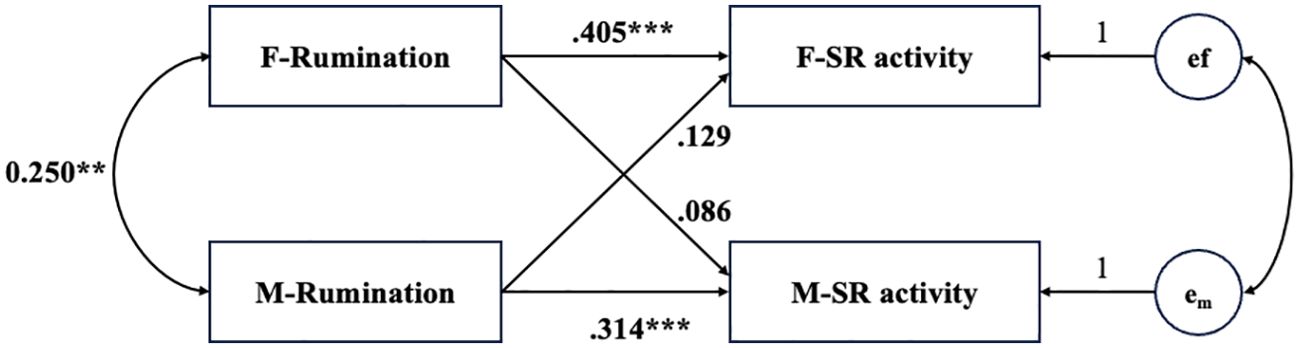

For the model with couples’ somatic and retarded activity as the outcome variables, the model fit the data well, χ²(2) = 0.48, p = .79, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .001. Regarding the actor effect, the results indicated that both males’ and females’ rumination were positively associated with their own somatic and retarded activities (females: β = .405, p <.001; males: β = .314, p <.001). However, for the partner effect, neither males’ nor females’ rumination was significantly associated with their partners’ somatic and retarded activities (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Actor–partner interdependence model predicting somatic and retarded activity from rumination. SR activity = somatic and retarded activity; ef and em represent the error terms of somatic and retarded activity of female and male. Participant age and relationship duration were controlled for in the model, but are not displayed in the figure for simplicity. ***p <.001.

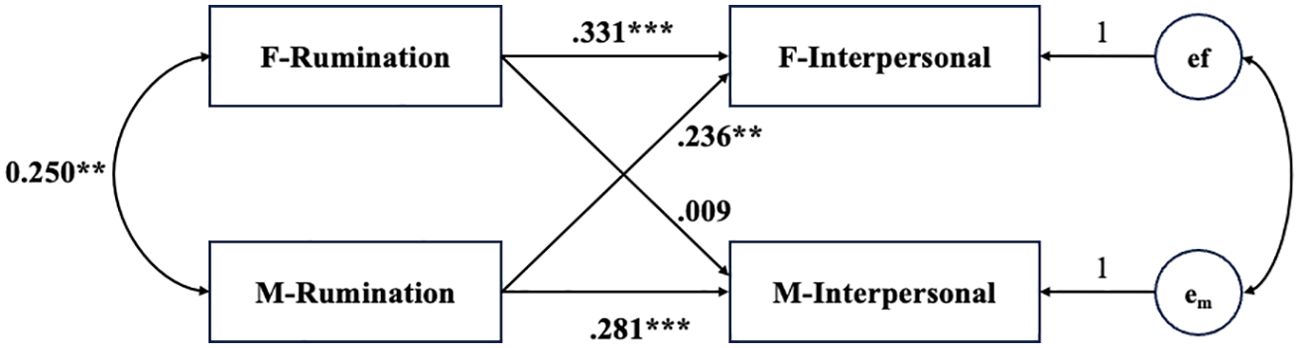

For the model with couples’ interpersonal distress as the outcome variable, the model fit the data well, χ²(2) = 2.62, p = .27, CFI = 0.989, TLI = 0.940, RMSEA = .045. As shown in Figure 4, regarding the actor effect, the results indicated that both males’ and females’ rumination were positively associated with their own interpersonal distress (females: β = .029, p <.001; males: β = .021, p <.001). For the partner effect, higher levels of rumination in males were positively correlated with higher levels of interpersonal distress in their female partners (β = .020, p = .001), while females’ rumination was not significantly associated with their male partners’ interpersonal distress (β = .001, p = .910). Additionally, for the covariate effects, relationship duration was negatively associated with both males’ and females’ interpersonal distress (females: β = -.007, p = .026; males: β = -.009, p = .003). depressed affect. However, participant age did not correlate with either males’ or females’ interpersonal distress.

Figure 4. Actor–partner interdependence model predicting interpersonal distress from rumination. Interpersonal = interpersonal distress; ef and em represent the error terms of interpersonal distress of female and male. Participant age and relationship duration were controlled for in the model, but are not displayed in the figure for simplicity. **p <.01, ***p <.001.

4 Discussion

Previous studies investigating the influence of rumination on depressive symptoms have often focused on its impact on the onset and duration of these symptoms (37, 38), leaving its role in more nuanced aspects of depressive symptoms unclear. Moreover, most literature has examined the relationship between rumination and depressive symptoms at the individual level (1, 2), with few studies exploring this relationship on both intrapersonal and interpersonal levels. Additionally, little research has investigated potential gender differences in these associations, particularly among individuals in romantic relationships.

The present study expands current knowledge by examining the effects of rumination on four aspects of depressive symptoms (i.e., depressed affect, positive affect, somatic and retarded activity, and interpersonal distress) in Chinese young couples, as well as the influence of gender on these associations. Results indicated that individuals who reported higher levels of rumination tended to experience greater depressed affect, somatic and retarded activity, and interpersonal distress. Interestingly, gender differences emerged in how an individual’s rumination was associated with their partner’s depressive symptoms. Specifically, males who reported more ruminative thoughts had female partners who reported higher levels of depressed affect and interpersonal distress. However, the reverse was not true; females’ rumination was not associated with their male partners’ depressed affect or interpersonal distress. These findings deepen our understanding of how gender differences influence individuals’ psychological responses to their partners’ rumination, highlighting the need for more targeted support programs for females in romantic relationships.

We found actor effects for both males and females, as well as partner effects for females, in the domains of depressed affect and interpersonal distress. The actor effects align with response styles theory (8), which posits that rumination can exacerbate depressive symptoms (39). Regarding partner effects, limited research has compared the impact of rumination on depressive affect and interpersonal distress across genders. Our findings reveal that males who engage in more ruminative thinking tend to have female partners with higher levels of depressed affect and interpersonal distress. In contrast, females’ rumination did not correspond to increased depressed affect or interpersonal distress in their male partners.

Several explanations may account for this gender difference. First, socialization often encourages females to be more emotionally expressive and introspective (23, 24). This increased focus on emotions can heighten their vulnerability to their partner’s rumination, making them more likely to experience depressive symptoms in response (7). Additionally, females may feel a stronger sense of responsibility for the emotional dynamics in their relationships (25, 26). This relational sensitivity can lead them to be more vigilant about signs of conflict or distress, making their partner’s rumination more impactful on their perceptions of relationship issues and on their own depressive symptoms. However, it is important to note that these potential explanations were not directly examined in our study, underscoring the need for future research to explore them further.

Surprisingly, rumination was not associated with positive affect at either the intrapersonal or interpersonal level. Our findings align with Tumminia and colleagues’ (2020) study, which found that rumination was significantly associated with adolescents’ negative affect but not with their positive affect. It appears that rumination is more closely linked to negative feelings, such as depressed affect, within couples than to positive emotions. These findings support previous observations that simply eliminating sources of suffering, such as rumination, may not be enough to enhance well-being (40). The absence of rumination does not necessarily lead to increased positive affect for individuals or their partners.

Regarding somatic and retarded depression-related activities, our results revealed only actor effects, meaning that an individual’s own rumination influenced their own somatic and retarded activity, while no partner effect was observed. This actor effect is consistent with existing research that demonstrates a strong link between rumination and various negative somatic consequences (14). The perseverative cognition hypothesis suggests that rumination can initiate and sustain stress, leading to adverse physiological outcomes, such as disrupted eating and sleep patterns (41). Rumination appears to keep individuals focused on negative thoughts, preventing them from engaging in restorative activities or seeking effective solutions under stress.

Interestingly, no partner effect was found, meaning that one partner’s rumination did not seem to influence the other partner’s somatic and retarded activity. This may be due to the more internalized and personal nature of somatic symptoms, which are typically experienced and managed on an individual level (42). Unlike emotional or interpersonal distress, which may be more shared or observable between partners, somatic symptoms related to rumination—such as sleep disruption or changes in appetite—are likely less directly influenced by a partner’s behavior. These symptoms may primarily be driven by the individual’s own coping mechanisms and physiological responses, rather than external factors such as their partner’s ruminative response style.

4.1 Limitations

Our study was among the firsts to explore the relationship between rumination and depressive symptoms at both the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels in a heterogeneous sample of young couples from the community. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of how rumination is linked to depressive symptoms in romantic relationships, while also highlighting the differential role of gender in these associations. However, there are some limitations to consider. First, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow us to establish causality or test the direction of effects. Second, the study relied solely on self-reported data for all variables, which may introduce biases such as social desirability or inaccurate self-assessment. Despite these limitations, this study provides one of the firsts evidence of a partner effect of rumination on females’ depressive symptoms in romantic relationships. These findings underscore the importance of developing targeted psychoeducation programs for females, particularly those with male partners who demonstrate higher levels of rumination, in order to help prevent the future development of depression.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Faculty of Psychology, Beijing Normal University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. AZ: Software, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ZJ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft. ZH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JQ: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. HW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (23ASH014), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32300891), and the Guangdong Province Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (GD24YXL04).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used ChatGPT to improve readability and language of the work. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Brandão T, Brites R, Hipólito J, Nunes O. Perceived emotional invalidation, emotion regulation, depression, and attachment in adults: A moderated-mediation analysis. Curr Psychol. (2023) 42:15773–81. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02809-5

2. Collins AC, Lass AN, Jordan DG, Winer ES. Examining rumination, devaluation of positivity, and depressive symptoms via community-based network analysis. J Clin Psychol. (2021) 77:2228–44. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23158

3. Kato T. The mediating role of experiential avoidance in the relationship between rumination and depression. Curr Psychol. (2024) 43:10339–45. doi: 10.1007/s12144-023-05199-4

4. Deguchi A, Masuya J, Naruse M, Morishita C, Higashiyama M, Tanabe H, et al. Rumination mediates the effects of childhood maltreatment and trait anxiety on depression in non-clinical adult volunteers. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2021) 2021:3439–45. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S332603

5. Kim AJ, Sherry SB, Mackinnon SP, Lee-Baggley D, Wang GA, Stewart SH, et al. When love hurts: Testing the stress generation hypothesis between depressive symptoms, conflict behaviors, and breakup rumination in romantic couples. J Soc Clin Psychol. (2024) 43:180–206. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2024.43.2.180

6. Visted E, Vøllestad J, Nielsen MB, Schanche E. Emotion regulation in current and remitted depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:756. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00756

7. Zawadzki MJ. Rumination is independently associated with poor psychological health: Comparing emotion regulation strategies. Psychol Health. (2015) 30:1146–63. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2015.1026904

8. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect psychol Sci. (2008) 3:400–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

9. Taylor MM, Snyder HR. Repetitive negative thinking shared across rumination and worry predicts symptoms of depression and anxiety. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. (2021) 43:904–15. doi: 10.1007/s10862-021-09898-9

10. McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behav Res Ther. (2011) 49:186–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006

11. Moulds ML, Bisby MA, Wild J, Bryant RA. Rumination in posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. (2020) 82:101910. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101910

12. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl psychol Meas. (1977) 1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

13. Hong RY. Worry and rumination: Differential associations with anxious and depressive symptoms and coping behavior. Behav Res Ther. (2007) 45:277–90. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.006

14. Yu T, Hu J, Zhao J. Childhood emotional abuse and depression symptoms among Chinese adolescents: the sequential masking effect of ruminative thinking and deliberate rumination. Child Abuse Negl. (2024) 154:106854. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2024.106854

15. Schwartz-Mette RA, Smith RL. When does co-rumination facilitate depression contagion in adolescent friendships? Investigating intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2018) 47:912–24. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1197837

16. Tudder A, Wilkinson M, Gresham AM, Peters BJ. The intrapersonal and interpersonal consequences of a new experimental manipulation of co-rumination. Emotion. (2023) 23:1190–201. doi: 10.1037/emo0001151

17. Feldman GC, Joormann J, Johnson SL. Responses to positive affect: A self-report measure of rumination and dampening. Cogn Ther Res. (2008) 32:507–25. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9083-0

18. Sailer U, Rosenberg P, Al Nima A, Gamble A, Gärling T, Archer T, et al. A happier and less sinister past, a more hedonistic and less fatalistic present and a more structured future: time perspective and well-being. PeerJ. (2014) 2:e303. doi: 10.7717/peerj.303

19. Tumminia MJ, Colaianne BA, Roeser RW, Galla BM. How is mindfulness linked to negative and positive affect? Rumination as an explanatory process in a prospective longitudinal study of adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. (2020) 49:2136–48. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01238-6

20. Espinosa F, Martin-Romero N, Sanchez-Lopez A. Repetitive negative thinking processes account for gender differences in depression and anxiety during adolescence. Int J Cogn Ther. (2022) 15:115–33. doi: 10.1007/s41811-022-00133-1

21. Johnson DP, Whisman MA. Gender differences in rumination: A meta-analysis. Pers Individ Dif. (2013) 55:367–74. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.019

22. Lilly KJ, Howard C, Zubielevitch E, Sibley CG. Thinking twice: examining gender differences in repetitive negative thinking across the adult lifespan. Front Psychol. (2023) 14:1239112. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1239112

23. Zeman J, Cameron M, Price N. Sadness in youth: Socialization, regulation, and adjustment. In: LoBue V, Edgar KP-, Buss K, editors. Handbook of emotional development. Springer, London, UK (2019). p. 227–256).

24. Zimmermann P, Iwanski A. Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: Age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. Int J Behav Dev. (2014) 38:182–94. doi: 10.1177/0165025413515405

26. Nowland R, Talbot R, Qualter P. Influence of loneliness and rejection sensitivity on threat sensitivity in romantic relationships in young and middle-aged adults. Pers Individ Dif. (2018) 131:185–90. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.04.047

27. Horn AB, Holzgang SA, Rosenberger V. Adjustment of couples to the transition to retirement: the interplay of intra-and interpersonal emotion regulation in daily life. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:654255. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.654255

28. Verhallen AM, Alonso-Martínez S, Renken RJ, Marsman J-BC, ter Horst GJ. Depressive symptom trajectory following romantic relationship breakup and effects of rumination, neuroticism and cognitive control. Stress Health. (2021) 38:653–65. doi: 10.1002/smi.3123

29. Bastin M, Luyckx K, Raes F, Bijttebier P. Co-rumination and depressive symptoms in adolescence: Prospective associations and the mediating role of brooding rumination. J Youth Adolesc. (2019) 50:1003–16. doi: 10.1007/s10964-021-01412-4

30. Horn AB, Maercker A. Intra-and interpersonal emotion regulation and adjustment symptoms in couples: The role of co-brooding and co-reappraisal. BMC Psychol. (2016) 4:51–62. doi: 10.1186/s40359-016-0159-7

31. Smith RL, Rose AJ. The “cost of caring” in youths’ friendships: Considering associations among social perspective taking, co-rumination, and empathetic distress. Dev Psychol. (2011) 47:1792–803. doi: 10.1037/a0025309

32. Joosten DHJ, Nelemans SA, Meeus W, Branje S. Longitudinal associations between depressive symptoms and quality of romantic relationships in late adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. (2021) 51:509–23. doi: 10.1007/s10964-021-01511-2

34. Kenny DA, Ledermann T. Bibliography of actor-partner interdependence model. J Behav Dev. (2012) 29:139–45. http://davidakenny.net/doc/apimbiblio.pdf. (Accessed January 7, 2025).

35. Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. J Abnormal Psychol. (1991) 100:569–82. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569

36. Yang J, Zhang C, Yao SQ. The impact of rumination and stressful life events on depressive symptoms in high school students: A multi-wave longitudinal study. Acta Psychol Sin. (2010) 42:939–45. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2010.00939

37. Stone LB, Hankin BL, Gibb BE, Abela JR. Co-rumination predicts the onset of depressive disorders during adolescence. J Abnormal Psychol. (2011) 120:752–7. doi: 10.1037/a0023384

38. Whisman MA, du Pont A, Butterworth P. Longitudinal associations between rumination and depressive symptoms in a probability sample of adults. J Affect Disord. (2020) 260:680–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.035

39. Steiner JL, Wagner CD, Bigatti SM, Storniolo AM. Depressive rumination and cognitive processes associated with depression in breast cancer patients and their spouses. Fam Syst Health. (2014) 32:378–88. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000066

40. Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol. (2000) 55:5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.1.89

41. Verkuil B, Brosschot JF, Gebhardt WA, Thayer JF. Perseverative cognition, psychopathology, and somatic health. In: Emotion regulation and well-being. Springer New York, New York, NY (2010). p. 85–100).

Keywords: gender, rumination, depressive symptoms, romantic relationship, young couples

Citation: Liu X, Zhou A, Jin Z, Han ZR, Qian J and Wang H (2025) Dyadic examination of rumination and depressive symptoms in Chinese heterogeneous young couples: the differential role of gender. Front. Psychiatry 15:1447040. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1447040

Received: 11 June 2024; Accepted: 19 December 2024;

Published: 21 January 2025.

Edited by:

Takahiro Nemoto, Toho University, JapanReviewed by:

Meenakshi Shukla, Allahabad University, IndiaSonja Mostert, University of Pretoria, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Zhou, Jin, Han, Qian and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jing Qian, amluZ3FpYW5AYm51LmVkdS5jbg==; Hui Wang, aHVpd2FuZ0BibnUuZWR1LmNu

Xiaoyu Liu

Xiaoyu Liu Anji Zhou

Anji Zhou Zhuyun Jin

Zhuyun Jin Zhuo Rachel Han

Zhuo Rachel Han Jing Qian

Jing Qian Hui Wang

Hui Wang