- 1Department of Psychiatry, Kangci Hospital of Jiaxing, Tongxiang, Zhejiang, China

- 2Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Intelligent Psychological Evaluation and Intervention, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Psychotic Disorders, Shanghai, China

- 3Department of Psychology, Shanghai Xinlianxin Psychological Counseling Center, Shanghai, China

- 4Department of Psychological Medicine, Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

Introduction: Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) traits play a crucial role in the prognosis of psychiatric disorders, as well as in assessing risks associated with negativity and impulsivity. However, there is a lack of data regarding the distribution characteristics of BPD traits and symptoms within clinical populations.

Methods: A total of 3015 participants (1321 males, 1694 females) were consecutively sampled from outpatients at the psychiatric and psycho-counseling clinics at the Shanghai Mental Health Center. BPD symptoms were assessed using a self-reported personality diagnostic questionnaire. Having BPD traits is defined as having five or more positive items in self-reported BPD characteristics. Participants were stratified into male and female groups, age groups, and diagnostic groups (schizophrenia, mood disorders, anxiety disorders). Exploratory factor analysis using principal components analysis was conducted. Three factors were identified: “F1: Affective Instability and Impulsivity”, “F2: Interpersonal Unstable and Extreme Reactions”, and “F3: Identity Disturbance”.

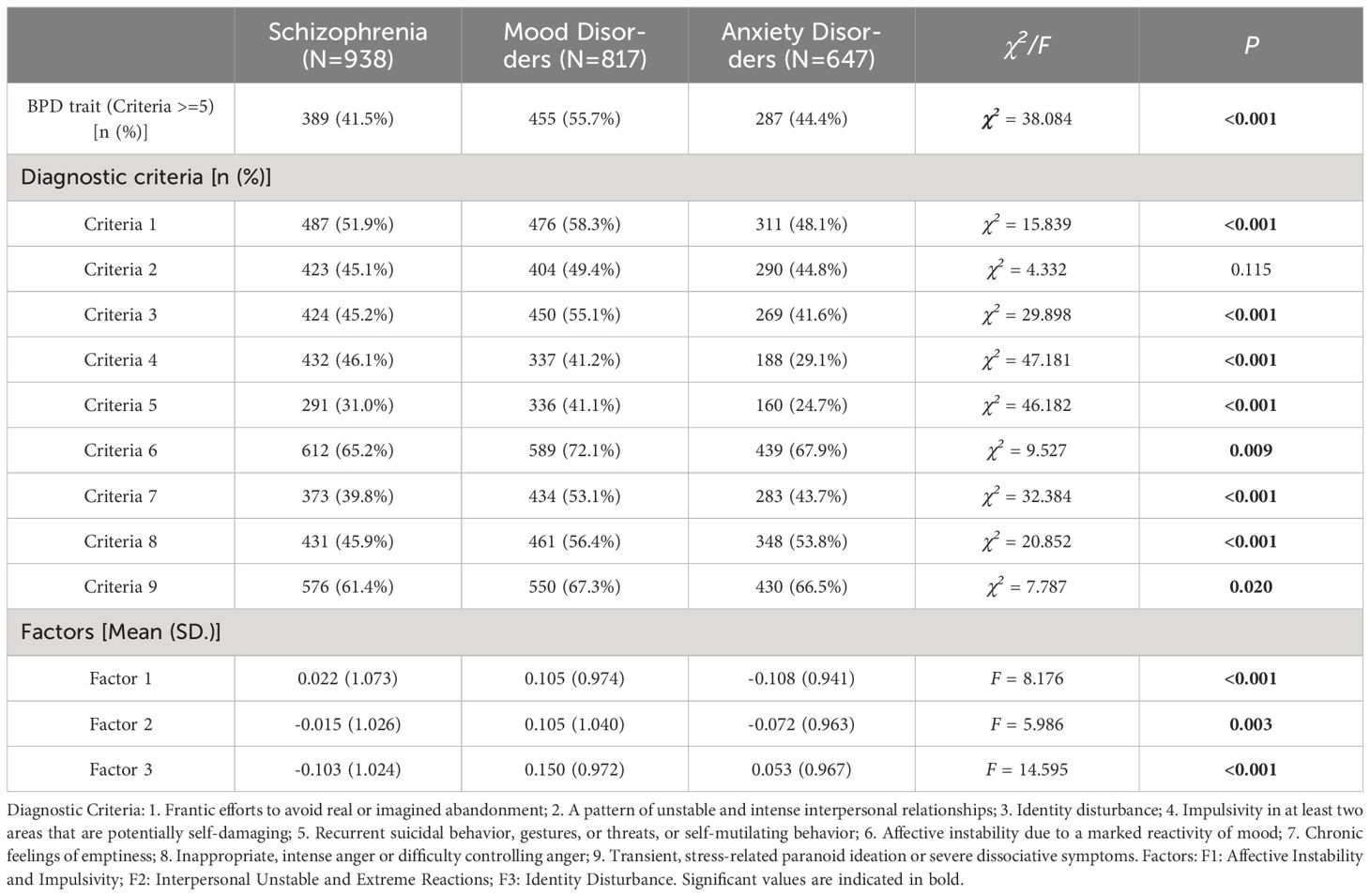

Results: Among 3015 participants, 45.9% of the patients self-reported BPD traits. Comparing of male and female patients, there was no statistically significant difference in the occurrence rate of BPD traits (χ2 = 1.835, p=0.176). However, in terms of symptoms, female patients reported more symptoms than male patients. Female patients also exhibited more pronounced features on F2 compared to male patients (t =-1.972, p=0.049). There is a general decrease in BPD traits, symptoms, and factors with increasing age. Specifically, the proportion of positive BPD traits is approximately halved before the age of 30 and decreases to around one-third after the age of 30. BPD traits were most common in the Mood Disorders group at 55.7%, followed by the Anxiety Disorders group at 44.4%, and Schizophrenia group at 41.5% (χ2 = 38.084, p<0.001).

Discussion: Our study revealed the pervasive presence of BPD traits and symptoms among psychiatric outpatients, exhibiting distinctive distributions across gender, age, and diagnostic categories. These findings emphasize the significance of identifying and addressing BPD pathology in the clinical care of psychiatric outpatients.

Introduction

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a common personality disorder characterized by pervasive emotion dysregulation, impulsivity, identity disturbances, and unstable and intense interpersonal relationships (1–3). Individuals with BPD are at an elevated risk of early death over the course of the disorder (4). Longitudinal research has reported rates of completed suicide and rates of early death from other medical causes in the longer term. A study by Temes et al. (5) followed 290 adult BPD inpatients over a 24-year period and found that 5.9% of borderline patients died by suicide, indicating an increased risk of premature death among individuals with BPD. Despite the significant risk associated with BPD, it remains a challenging disorder both in terms of diagnosis and treatment (6). There is ongoing controversy regarding its conceptualization, with debate over whether it should be viewed as a specific personality disorder or as a level of impairment in general personality functioning (7). Treatment for BPD, including both pharmacotherapy (8) and psychotherapy (9), remains challenging.

In the identification of BPD, instability in multiple aspects such as self-image, emotions, interpersonal relationships, and behavioral patterns is involved. These unstable features often blur the boundaries between BPD and other psychiatric disorders, leading to frequent comorbidities (10–12). These comorbidities contribute to poor prognosis. A previous longitudinal study tracking a clinical cohort with BPD found that chronic somatic conditions are prevalent in individuals with BPD and interact negatively with persistent BPD pathology, deteriorating their long-term quality of life (13). In addition to comorbidities with Axis I disorders and physical illnesses, comorbidities between BPD and other personality disorders are also common. It suggests that BPD exhibits features of personality dysfunction that are shared across all types of personality disorders and exist on a severity dimension (14).

Previous research has demonstrated that BPD traits and symptoms manifest differently across genders and ages (15, 16). Studies have shown mixed results regarding gender differences in BPD (17, 18). Some studies indicate that certain BPD features, such as suicidal behavior and intense anger, are more prevalent in women, while other studies report no significant gender differences. For instance, Johnson et al. found that women with BPD tend to exhibit more emotional dysregulation and self-harm behaviors than men (19), whereas Zanarini et al. found no significant gender differences in the overall severity of BPD symptoms (20). Age-related changes in BPD symptoms have also been observed. Longitudinal studies suggest that certain BPD symptoms, such as impulsivity and aggression, tend to decrease with age. For example, research by Paris and Zweig-Frank indicated that older individuals with BPD exhibit fewer impulsive behaviors and have a lower prevalence of substance use disorders compared to younger individuals (3).

In recent years, the prevalence of BPD patients and BPD traits has been increasing among psychiatric clinical populations, particularly among adolescents and young adults (21), with Non-Suicidal Self-Injury as a prominent feature (22). This situation poses significant challenges to clinical diagnosis and treatment. Overall, BPD traits are characterized by impulsivity and the risk of negative self-harm and suicide. Additionally, they often coexist with other psychiatric disorders, exerting a significant impact on the prognosis of common mental disorders. Therefore, it is crucial for clinicians to recognize and address BPD traits as an important component of routine assessments. Given these concerns, this study investigated the distribution of BPD traits among a large clinical sample, stratifying by gender, age, and diagnosis, aiming to achieve a better understanding of BPD’s presentation in psychiatric clinical populations.

Methods

Sample and procedures

The survey was conducted at the Shanghai Mental Health Center (SMHC) from 2016 to 2023, involving participants recruited from outpatients attending psycho-counseling and psychiatric clinics at SMHC, one of China’s largest healthcare facilities. The study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee at SMHC (2016–3R), and participants provided written informed consent during the recruitment stage. The study aimed to assess the prevalence of Personality Disorders (PDs) in a consecutive clinical sample of adult patients. A total of 3015 outpatients were randomly selected between January 2016 and December 2023, meeting inclusion criteria such as age between 18 and 55 years, ability to comprehend the study questionnaire, willingness to disclose information about PDs, and being under stable treatment conditions. “Stable treatment conditions” are defined as having no changes in treatment regimen, including medication and therapy, in the two weeks prior to study enrollment. Exclusion criteria included severe or unstable physical conditions, current pregnancy, and other factors identified by investigators as rendering the patient ineligible.

Among the screened participants, 219 individuals did not complete the self-assessment scales, resulting in incomplete data and their exclusion from the analysis. Primary reasons for non-completion included perceived assessment duration being too lengthy for 179 participants, 33 individuals providing entirely inconsistent responses, 3 participants refusing researchers’ use of information provided after the interview, and 7 individuals requesting to withdraw from the study without providing a clear reason. Ultimately, data from 3015 patients were included in the final analysis. Among 3015 participants, the mean age was 31.5 years (SD=9.679), with 1694 females (56.2%), 1592 being first diagnosed (52.8%), 1551 single (51.4%), and the mean duration of disorder being 58.9 months (SD=75.798).

BPD trait measurements

The assessment of BPD traits and symptoms utilized a concise and well-structured self-report questionnaire, namely the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire 4th Edition Plus (PDQ-4plus) (23), as described in previous publications (2, 10, 24). The PDQ-4plus comprises 107 true-false questions designed to evaluate 10 Axis II DSM-IV PDs, including BPD, which is the focus of this study. Specifically, the questionnaire includes 11 items related to BPD traits, corresponding to the 9 diagnostic criteria outlined in DSM-IV (see Table 1). Having BPD traits is defined as having five or more positive items in self-reported BPD characteristics, corresponding to the requirement in BPD diagnostic criteria of meeting five or more diagnostic criteria. The primary aim of the PDQ-4plus is to differentiate individuals exhibiting characteristics associated with PD from those who do not. It demonstrates high sensitivity (0.89) and acceptable specificity (0.65). Widely used for screening DSM-IV PDs in Chinese psychiatric patients, the PDQ-4plus has shown high test-retest reliability (0.92) within the Chinese population, indicating the questionnaire’s reliability in yielding consistent results (11, 25, 26).

Clinical diagnosis

All participants received clinical diagnoses from their psychiatrists according to routine clinical practice, utilizing the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10). The diagnoses were provided by psychiatrists with over 5 years of clinical experience, ensuring a high level of diagnostic reliability and expertise. Participants diagnosed with schizophrenia were classified under the F20 category, which includes various subtypes and categories such as paranoid schizophrenia (F20.0), hebephrenic schizophrenia (F20.1), catatonic schizophrenia (F20.2), undifferentiated schizophrenia (F20.3), residual schizophrenia (F20.5), other schizophrenia (F20.8), and unspecified schizophrenia (F20.9).

Participants diagnosed with mood disorders were categorized under the F30-F39 range, encompassing various subtypes and categories including manic episode (F30), bipolar affective disorder (F31), depressive episode (F32), recurrent depressive disorder (F33), persistent mood disorders (F34), other mood disorders (F38), and unspecified mood disorders (F39).

Participants diagnosed with anxiety disorders were classified under the F40-F48 range, which includes various subtypes and categories such as phobic anxiety disorders (F40), other anxiety disorders (F41), obsessive-compulsive disorder (F42), reaction to severe stress, and adjustment disorders (F43), dissociative disorders (F44), somatoform disorders (F45), and other nonpsychotic mental disorders (F48).

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The dataset underwent double data entry, and rigorous data checking and cleaning procedures were conducted to ensure both range and consistency prior to analysis. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Quantitative variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while qualitative variables are presented as frequencies (%). We conducted exploratory factor analysis using principal components analysis, followed by varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization. The determination of the number of factors retained in the analysis was based on factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. Subsequently, utilizing the factor loading coefficients, we calculated the estimated factor scores for each factor for all participants. Three factors were identified: “F1: Affective Instability and Impulsivity”, “F2: Interpersonal Unstable and Extreme Reactions”, and “F3: Identity Disturbance”. Participants were stratified into male and female groups, age groups (18–20, 21–25, 26–30, 31–35, 36–40, 41–45, 46–50, 51–55 years), and diagnostic groups (Schizophrenia, mood disorders, anxiety disorders). Differences between means and proportions were assessed using the t-test (for comparison between two groups), one-way ANOVA (for comparison among three or more groups), and the Chi-square test, respectively. To visually depict gender and age differences more intuitively, bar charts and line graphs were utilized.

Results

Criteria and factors

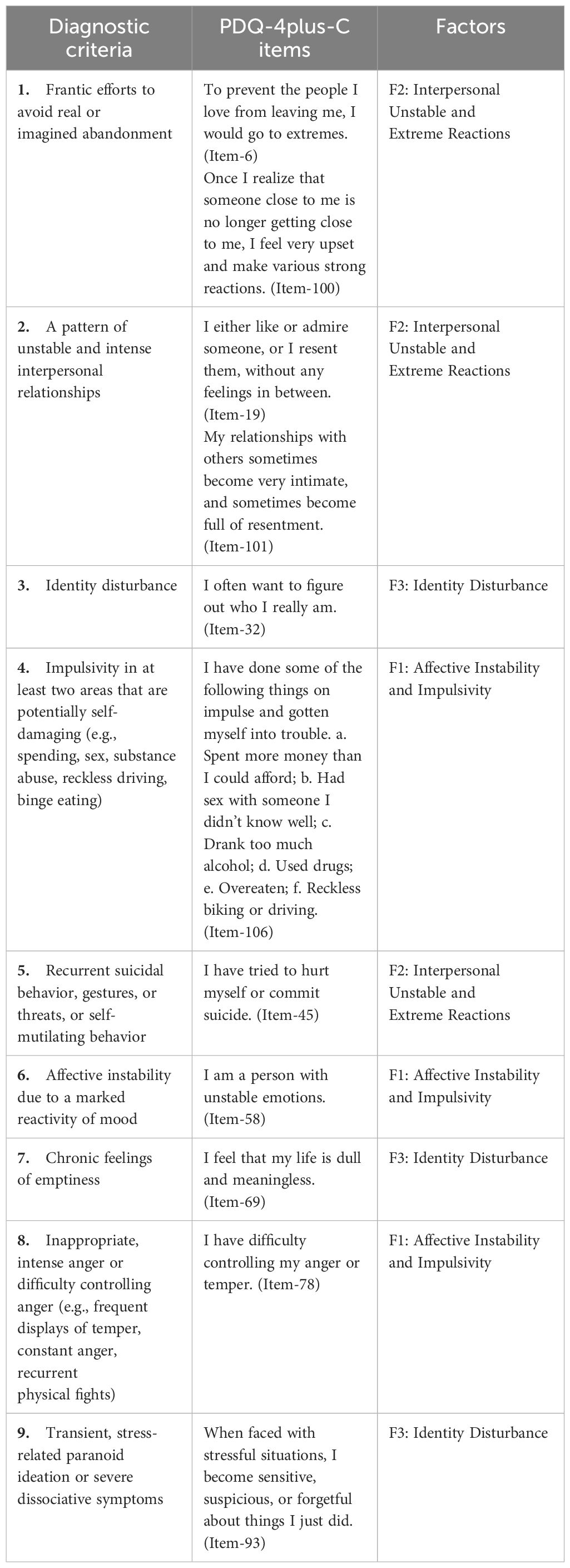

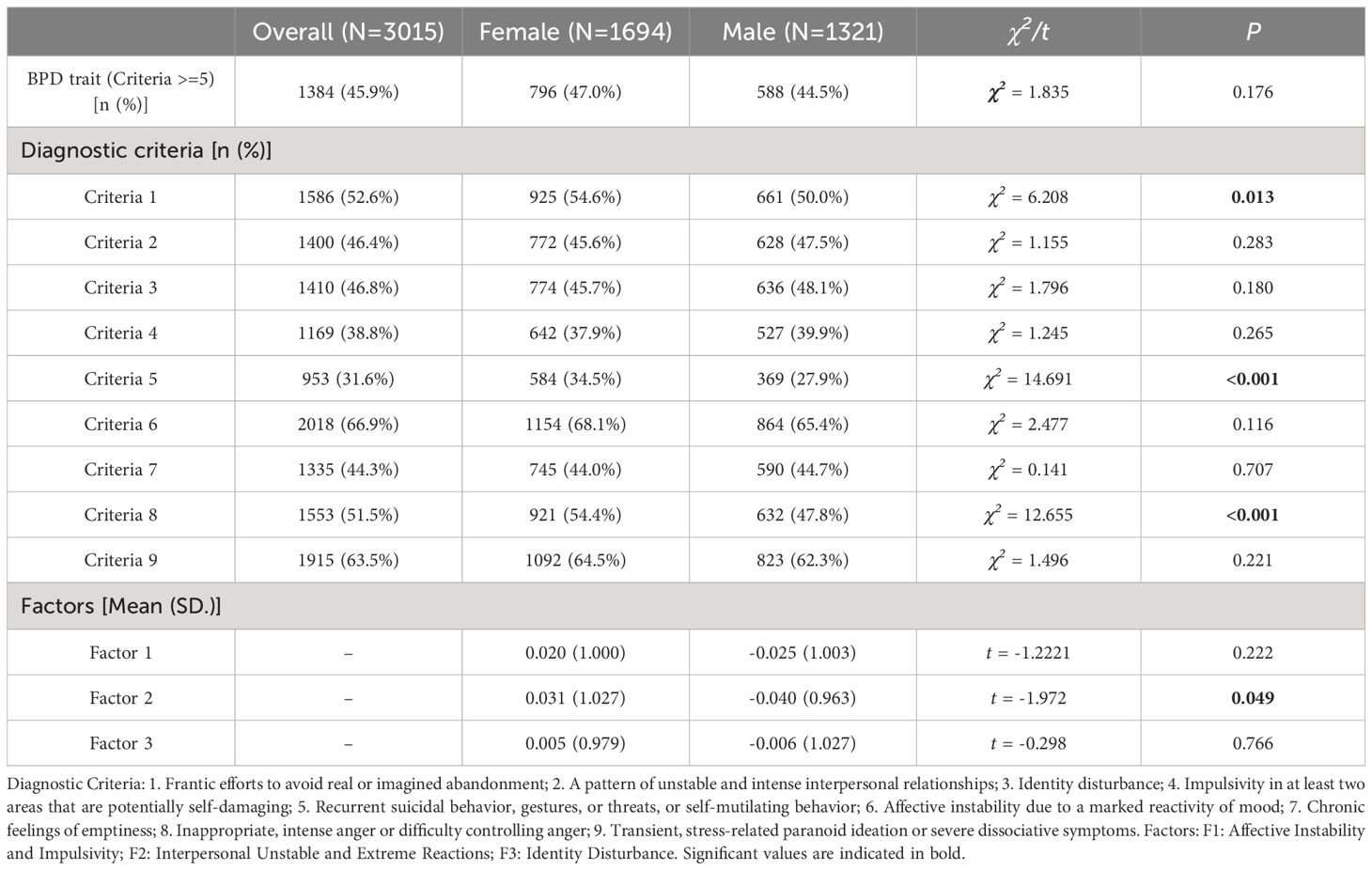

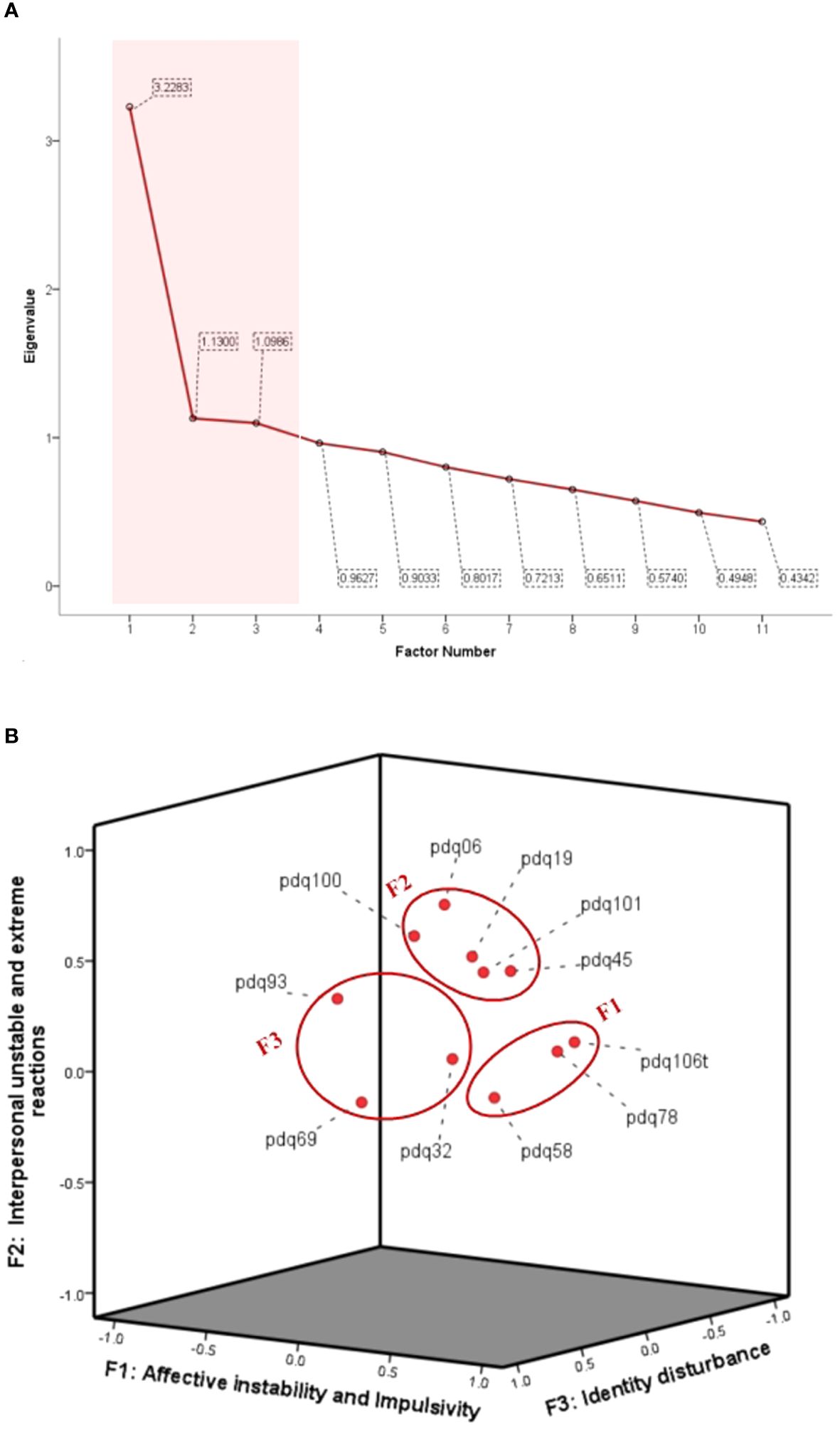

Table 1 presents the BPD diagnostic criteria alongside their corresponding PDQ-4plus-C items. Exploratory factor analysis of the PDQ-4plus-C items revealed three factors, as illustrated in Figures 1A, B. These three factors exhibited eigenvalues greater than 1, indicating their significance, while other factors with eigenvalues below 1 were not retained (Figure 1A). The first factor, with an eigenvalue of 3.228, comprised items 58, 78, and 106, and was labeled as “Affective Instability and Impulsivity”. The second factor, with an eigenvalue of 1.130, included items 6, 19, 45, 100, and 101, and was termed “Interpersonal Unstable and Extreme Reactions”. The third factor, with an eigenvalue of 1.099, encompassed items 32, 69, and 93, and was designated as “Identity Disturbance” (Figure 1B).

Figure 1 Factors by self-reported BPD traits. (A) Standardized factor loadings were obtained from the exploratory factor analysis, using varimax rotation. (B) Factor plot in rotated space.

Profiles of BPD criteria and factors in overall sample and gender groups

As shown in Table 2, nearly half (45.9%) of the clinically assessed patients self-reported BPD traits. Among our sample population, the most commonly reported BPD symptom was Criterion 6 “Affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood” (66.9%), followed by Criterion 9 “Transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms” (63.5%). Additionally, the more severe symptom “Recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, or threats, or self-mutilating behavior” was reported by almost one-third of the patients (31.6%). Comparing BPD traits and symptoms reported by male and female patients, there was no statistically significant difference in the occurrence rate of BPD traits between the two groups (χ2 = 1.835, p = 0.176). However, in terms of symptoms, female patients reported more Criteria 1 (χ2 = 6.208, p = 0.013), 5 (χ2 = 14.691, p < 0.001), and 8 (χ2 = 12.655, p < 0.001) than male patients. Female patients also exhibited more pronounced features on Factor 2 “Interpersonal Unstable and Extreme Reactions” compared to male patients (t = -1.972, p = 0.049).

BPD traits profile across age groups

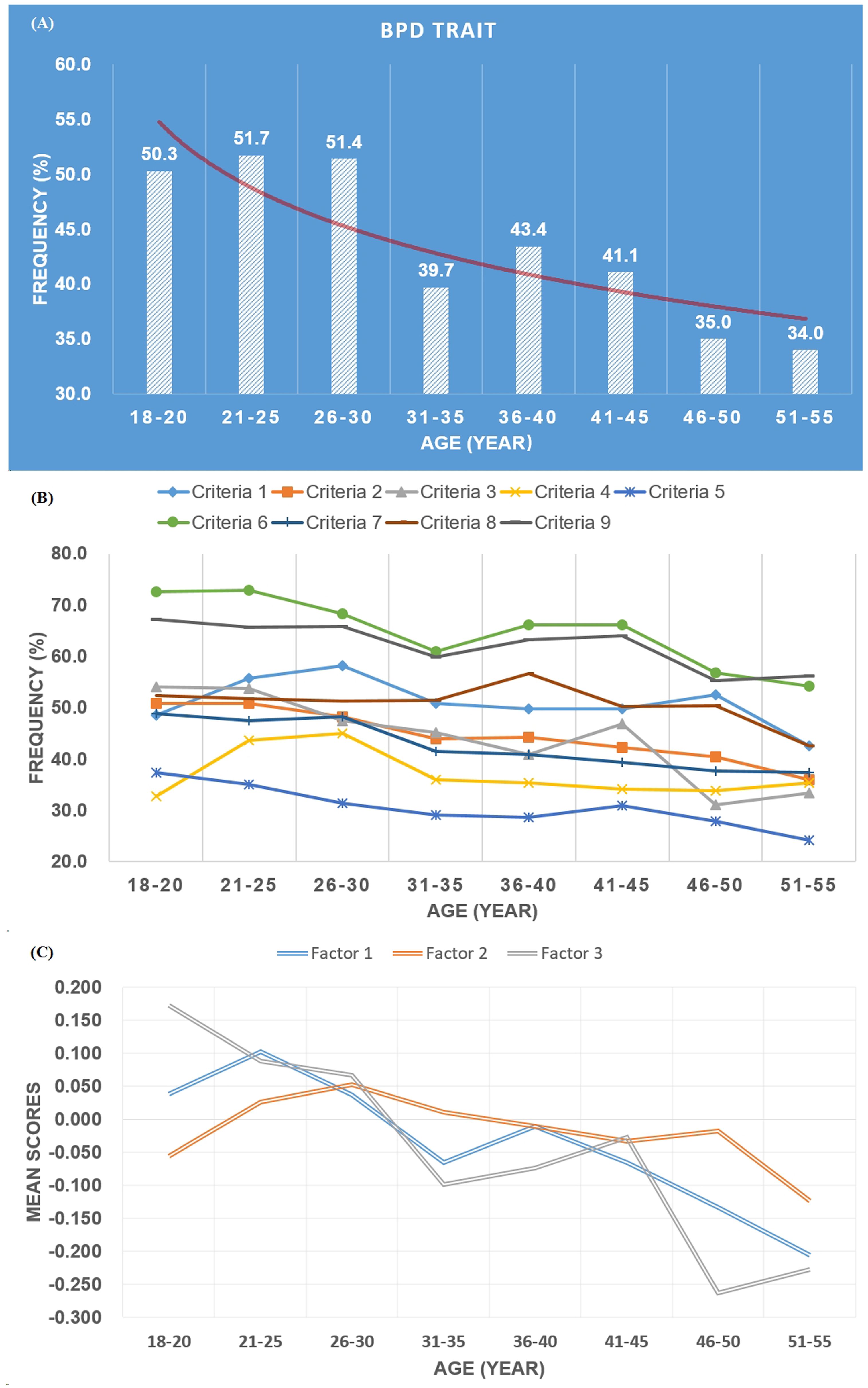

As shown in Figure 2, there is a general decrease in BPD traits, symptoms, and factors with increasing age. Specifically, in Figure 2A, the proportion of positive BPD traits is approximately halved before the age of 30 and decreases to around one-third after the age of 30. Likewise, there is a declining trend in the symptoms associated with each diagnostic criterion (Figure 2B). Based on the one-way ANOVA indicates statistically significant differences in the declining trends of Factor 1 (F = 3.074, df = 7, p=0.003) and Factor 3 (F = 6.413, df = 7, p < 0.001) with age (Figure 2C).

Figure 2 Frequency of BPD trait (A), criteria (B), and profile of three factors (C) across age groups.

BPD traits profile across diagnostic groups

Based on the diagnostic grouping of Schizophrenia (N=938), Mood Disorders (N=817), and Anxiety Disorders (N=647), significant differences were observed in the distribution of BPD traits, symptoms, and factors among these three groups (Table 3). BPD traits were most common in the Mood Disorders group at 55.7%, followed by the Anxiety Disorders group at 44.4%, and Schizophrenia group at 41.5% (χ2 = 38.084, p < 0.001). Among the 9 symptom criteria, except for Criterion 2 where there was no significant difference among the three groups, differences were observed for all other criteria (p < 0.05). Specifically, BPD symptoms were most prevalent in the Mood Disorders group, except for Criterion 4 “Impulsivity in at least two areas that are potentially self-damaging,” which was relatively less common in the Anxiety Disorders group. However, Criterion 4 was relatively more prevalent in the Schizophrenia group at 46.1%. Among the three factors, the Mood Disorders group had the highest factor scores, followed by Schizophrenia for factors 1 (F = 8.176, p < 0.001) and 2 (F = 5.986, p = 0.003), and Anxiety Disorders for factor 3 (F = 14.595, p < 0.001).

Table 3 Frequency of BPD trait, criteria, and profile of three factors, compared among diagnostic groups.

Discussion

Key findings

Through a cross-sectional survey involving a substantial clinical sample, this study provides a comprehensive overview of the distribution of BPD pathology among a large clinical population. The findings indicate that approximately half of psychiatric patients exhibit a prominent self-reported trait of BPD, with affective instability being the most common symptom. The clinical features of BPD can be summarized into three dimensions: Affective Instability and Impulsivity, Interpersonal Unstable and Extreme Reactions, and Identity Disturbance. While there was no difference in the proportion of reported BPD traits between genders, suicidal or self-mutilating behavior and extreme reactions were more common among female patients. Regarding age effects, BPD traits, symptoms, and the three dimensions showed an overall declining trend with increasing age. More than half of the patients diagnosed with mood disorders reported BPD traits, and clinical BPD symptoms were more pronounced among them compared to patients with schizophrenia and anxiety disorders. Regarding the impulsivity dimension of BPD symptoms, schizophrenia patients exhibited more pronounced features compared to patients with anxiety disorders.

Gender effect

The manifestation of BPD features occurs in both genders, yet the debate on whether they are more prevalent in men or women persists in the literature, remaining an empirical question (27). Studies focusing on clinical differences between genders in BPD patients are limited (28). Some studies (29–32) suggest that certain BPD features are more prevalent in women, while others report no significant difference across genders (19, 33), and a minority suggest that some clinical manifestations are more common in men (34, 35). Our study found no difference between genders in self-reported BPD traits. However, female patients exhibited higher prevalence rates compared to male patients in criteria 5 “Recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, or threats, or self-mutilating behavior”, criteria 8 “Inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger”, and criteria 1 “Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment”. The differences in societal gender roles may contribute to the observed gender disparities. In many societies, traditional gender norms and expectations shape how individuals express and cope with emotions, interpersonal relationships, and distress. From a young age, boys and girls are often socialized differently in terms of how they are encouraged to express their emotions. Boys may be taught to suppress vulnerable emotions like sadness or fear, while girls may be encouraged to express these emotions more openly. This could lead to differences in how BPD-related emotions such as anger, sadness, or anxiety are expressed and perceived between genders. While our study primarily focused on psychological differences, it is essential to consider the influence of hormonal variations, neurobiological factors, and differences in brain structure and function on the manifestation of BPD. Future research could explore the interplay between psychological and physiological factors to gain a more comprehensive understanding of gender effects in BPD pathology.

Age effect

Previous studies (36–38) have produced inconclusive evidence regarding whether improvements in BPD symptoms are attributed to the passage of time or differences in the age of individuals in the study. Nonetheless, the potential for age-related reductions in symptoms is supported by research indicating that BPD-relevant symptoms change with age across various psychopathologies (39). For instance, impulsivity and aggression are more strongly associated with completed suicides in younger individuals compared to older ones (40). Our study findings indicate a trend of alleviation in BPD traits, symptoms, and factors with increasing age, especially for the dimension of identity disturbance. This observed trend could be attributed to several factors. As individuals age, they often experience greater maturity and personal growth. This may lead to improved self-awareness, emotional regulation, and coping skills, which are essential components in managing BPD symptoms. With age comes increased stability in various aspects of life, such as relationships, career, and social support networks. Greater stability can provide a buffer against the emotional turmoil and interpersonal difficulties characteristic of BPD, contributing to symptom alleviation (41). Age-related changes in brain structure and function, particularly during adolescence and early adulthood, may contribute to variations in cognitive and emotional processes relevant to BPD pathology. Future research could explore the interplay between neurodevelopmental factors and psychological manifestations to gain a more comprehensive understanding of age effects in BPD.

Diagnostic effect

BPD exhibits high rates of comorbidity with various Axis I disorders in both clinical (42) and community samples (43, 44). What distinguishes BPD from many other conditions is its shared characteristics with both internalizing and externalizing disorders (45). Regarding internalizing disorders, features of BPD such as affective instability, feelings of emptiness, and interpersonal difficulties may contribute to the elevated rates of comorbidity between BPD and mood (46)/anxiety disorders (47). On the other hand, concerning externalizing disorders, previous research has established a strong association with substance use (48)/impulse control disorders (49). In our current clinical sample, approximately half of the patients reported BPD traits, indicating the widespread presence of BPD symptom dimensions among clinical populations, particularly among patients with mood disorders. This suggests that assessing BPD features and symptoms in clinical patients can provide additional insight into the comprehensive understanding of both internalizing and externalizing disorders. Given the elevated risk of self-harm, suicide, and impulsivity among BPD patients, developing personalized risk management strategies based on the assessment of BPD features may be necessary in psychiatric clinical routine (50).

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. Firstly, despite being a large-scale study, the cross-sectional design used restricts the ability to establish causal relationships; instead, the study provides descriptive comparisons. Future research could benefit from longitudinal designs, such as cohort studies, to delve deeper into causal connections. Secondly, recall bias is inherent in retrospective assessments, and the accuracy of recollections may be influenced by varying illness trajectories and patient ages. Moreover, axis I psychiatric symptoms may influence the collection of BPD traits and symptoms, potentially leading to fabrication or misconstruction. Although we emphasized during the PDQ-4plus assessment that questions are targeted towards consistent behavioral patterns rather than transient symptoms, patients may still be influenced when self-reporting. For example, individuals with severe depression may be more inclined to perceive themselves as possessing pathological personality traits. Lastly, due to the extensive scope of assessments focusing primarily on BPD traits, the study did not systematically evaluate patients’ clinical symptoms. Consequently, the relationship between different symptom types and BPD traits/symptoms remains unexplored.

Conclusion

Our study identified widespread presence of BPD traits and symptoms among psychiatric outpatients, with characteristic distributions across gender, age, and diagnostic categories. These findings suggest that clinicians should be vigilant for the presence of BPD traits and symptoms when assessing psychiatric patients, particularly in certain demographic groups such as females, younger individuals and with diagnosis of mood disorders. Early identification and intervention for BPD traits can help prevent the development of more severe symptoms, suicide and self-harm risks and improve overall treatment outcomes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The ethics committee of Shanghai Mental Health Center. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YL: Writing – original draft, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. ZG: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. YZ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Funding acquisition. YW: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation. LX: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. XT: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. ZW: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. YH: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. JW: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Conceptualization. HW: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Resources. YLL: Writing – review & editing. YM: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Conceptualization. TZ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC2506800), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171544, 82371505, 82151314, 82101623, 82101582, 82271548, U22A20305), and Zhejiang Provincial Medical Health Science and Technology Project (2023XY198).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Wang L, Ross CA, Zhang T, Dai Y, Zhang H, Tao M, et al. Frequency of borderline personality disorder among psychiatric outpatients in Shanghai. J Pers Disord. (2012) 26:393–401. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.3.393

2. Zhang T, Wang L, Good MJ, Good BJ, Chow A, Dai Y, et al. Prevalence of personality disorders using two diagnostic systems in psychiatric outpatients in Shanghai, China: a comparison of uni-axial and multi-axial formulation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2012) 47:1409–17. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0445-x

3. Paris J, Zweig-Frank H. A 27-year follow-up of patients with borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. (2001) 42:482–7. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.26271

4. Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry. (2014) 13:153–60. doi: 10.1002/wps.v13.2

5. Temes CM, Frankenburg FR, Fitzmaurice GM, Zanarini MC. Deaths by suicide and other causes among patients with borderline personality disorder and personality-disordered comparison subjects over 24 years of prospective follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. (2019) 80. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12436

6. Leichsenring F, Fonagy P, Heim N, Kernberg OF, Leweke F, Luyten P, et al. Borderline personality disorder: a comprehensive review of diagnosis and clinical presentation, etiology, treatment, and current controversies. World Psychiatry. (2024) 23:4–25. doi: 10.1002/wps.21156

7. Mulder RT, Horwood LJ, Tyrer P. The borderline pattern descriptor in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision: A redundant addition to classification. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2020) 54:1095–100. doi: 10.1177/0004867420951608

8. Stoffers-Winterling JM, Storebo OJ, Pereira Ribeiro J, Kongerslev MT, Vollm BA, Mattivi JT, et al. Pharmacological interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2022) 11:CD012956. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012956.pub2

9. Woodbridge J, Townsend M, Reis S, Singh S, Grenyer BF. Non-response to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2022) 56:771–87. doi: 10.1177/00048674211046893

10. Zheng Y, Severino F, Hui L, Wu H, Wang J, Zhang T. Co-morbidity of DSM-IV personality disorder in major depressive disorder among psychiatric outpatients in China: A further analysis of an epidemiologic survey in a clinical population. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:833. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00833

11. Wang J, Chen Z, Sun W, Zheng Y, Hui L, Liu X, et al. A strategy to address high comorbidity of personality disorders in a Chinese population: A principal and subordinate diagnostic model. Psychiatry. (2019) 82:272–82. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2019.1600218

12. Zhu S, Zhang T, Yang C, Wei Y, Xu L, Wang J, et al. A compromise solution between overlapping and overlooking DSM personality disorders in Chinese psychiatric practice. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2018) 53:99–106. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1444-3

13. Alvarez-Tomas I, Soler J, Schmidt C, Pascual JC. Physical health, primary care utilization and long-term quality of life in borderline personality disorder: A 10-year follow-up study in a Spanish sample. J Psychosom Res. (2024) 179:111623. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2024.111623

15. BarraChina J, Pascual JC, Ferrer M, Soler J, Rufat MJ, Andion O, et al. Axis II comorbidity in borderline personality disorder is influenced by sex, age, and clinical severity. Compr Psychiatry. (2011) 52:725–30. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.11.009

16. Distel MA, Trull TJ, Derom CA, Thiery EW, Grimmer MA, Martin NG, et al. Heritability of borderline personality disorder features is similar across three countries. Psychol Med. (2008) 38:1219–29. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002024

17. Preyde M, DiCroce M, Parekh S, Heintzman J. Exploring screening for borderline personality disorder in pediatric inpatients with psychiatric Illness. Psychiatry Res. (2022) 309:114397. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114397

18. De Moor MH, Distel MA, Trull TJ, Boomsma DI. Assessment of borderline personality features in population samples: is the Personality Assessment Inventory-Borderline Features scale measurement invariant across sex and age? Psychol Assess. (2009) 21:125–30. doi: 10.1037/a0014502

19. Johnson DM, Shea MT, Yen S, Battle CL, Zlotnick C, Sanislow CA, et al. Gender differences in borderline personality disorder: findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Compr Psychiatry. (2003) 44:284–92. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00090-7

20. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Silk KR, Hudson JI, McSweeney LB. The subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder: a 10-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. (2007) 164:929–35. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.929

21. Klinkby IMI, Hastrup LH, Bo S, Storebo OJ, Simonsen E, Kongerslev MT. Prevalence and incidence of personality disorders among children and adolescents in Danish mental health services: a nationwide register study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2023) Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1007/s00787-023-02274-w

22. Cipriano A, Cella S, Cotrufo P. Nonsuicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:1946. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01946

23. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation. (1996) 93:1043–65.

24. Zhang T, Li H, Tang Y, Li H, Zheng L, Guo Q, et al. Screening schizotypal personality disorder for detection of clinical high risk of psychosis in Chinese mental health services. Psychiatry Res. (2015) 228:664–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.04.049

25. Wang J, Sun W, Tang X, Xu L, Wei Y, Cui H, et al. Transdiagnostic dimensions towards personality pathology and childhood traumatic experience in a clinical sample: subtype classification by a cross-sectional analysis. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:11248. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47754-9

26. Wei Y, Zhang T, Chow A, Tang Y, Xu L, Dai Y, et al. Co-morbidity of personality disorder in schizophrenia among psychiatric outpatients in China: data from epidemiologic survey in a clinical population. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:224. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0920-8

27. Bozzatello P, Blua C, Brandellero D, Baldassarri L, Brasso C, Rocca P, et al. Gender differences in borderline personality disorder: a narrative review. Front Psychiatry. (2024) 15:1320546. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1320546

28. Qian X, Townsend ML, Tan WJ, Grenyer BFS. Sex differences in borderline personality disorder: A scoping review. PloS One. (2022) 17:e0279015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279015

29. McCormick B, Blum N, Hansel R, Franklin JA, St John D, Pfohl B, et al. Relationship of sex to symptom severity, psychiatric comorbidity, and health care utilization in 163 subjects with borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. (2007) 48:406–12. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.05.005

30. Silberschmidt A, Lee S, Zanarini M, Schulz SC. Gender differences in borderline personality disorder: results from a multinational, clinical trial sample. J Pers Disord. (2015) 29:828–38. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_175

31. Tadic A, Wagner S, Hoch J, Baskaya O, von Cube R, Skaletz C, et al. Gender differences in axis I and axis II comorbidity in patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology. (2009) 42:257–63. doi: 10.1159/000224149

32. Sher L, Rutter SB, New AS, Siever LJ, Hazlett EA. Gender differences and similarities in aggression, suicidal behaviour, and psychiatric comorbidity in borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2019) 139:145–53. doi: 10.1111/acps.12981

33. Bernstein DP, Cohen P, Velez CN, Schwab-Stone M, Siever LJ, Shinsato L. Prevalence and stability of the DSM-III-R personality disorders in a community-based survey of adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. (1993) 150:1237–43. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1237

34. Henry KA, Cohen CI. The role of labeling processes in diagnosing borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (1983) 140:1527–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.11.1527

35. Zanarini MC, Horwood J, Wolke D, Waylen A, Fitzmaurice G, Grant BF. Prevalence of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder in two community samples: 6,330 English 11-year-olds and 34,653 American adults. J Pers Disord. (2011) 25:607–19. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.5.607

36. Alvarez-Tomas I, Ruiz J, Guilera G, Bados A. Long-term clinical and functional course of borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Psychiatry. (2019) 56:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.10.010

37. Tracie Shea M, Edelen MO, Pinto A, Yen S, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, et al. Improvement in borderline personality disorder in relationship to age. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2009) 119:143–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01274.x

38. Soloff PH, Chiappetta L. Time, age, and predictors of psychosocial outcome in borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. (2020) 34:145–60. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2018_32_386

39. Zhang T, Good MJ, Good BJ, Chow A, Wang L, Dai Y, et al. Age and remission of personality pathology in the psychotic disorders compared to mood and/or anxiety disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med. (2012) 44:241–55. doi: 10.2190/PM.44.3.e

40. McGirr A, Renaud J, Bureau A, Seguin M, Lesage A, Turecki G. Impulsive-aggressive behaviours and completed suicide across the life cycle: a predisposition for younger age of suicide. Psychol Med. (2008) 38:407–17. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001419

41. Peckham AD, Jones P, Snorrason I, Wessman I, Beard C, Bjorgvinsson T. Age-related differences in borderline personality disorder symptom networks in a transdiagnostic sample. J Affect Disord. (2020) 274:508–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.111

42. Ha C, Balderas JC, Zanarini MC, Oldham J, Sharp C. Psychiatric comorbidity in hospitalized adolescents with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. (2014) 75:e457–64. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08696

43. Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. (2007) 62:553–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019

44. Tomko RL, Trull TJ, Wood PK, Sher KJ. Characteristics of borderline personality disorder in a community sample: comorbidity, treatment utilization, and general functioning. J Pers Disord. (2014) 28:734–50. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2012_26_093

45. Bailey AJ, Finn PR. Borderline personality disorder symptom comorbidity within a high externalizing sample: relationship to the internalizing-externalizing dimensional structure of psychopathology. J Pers Disord. (2020) 34:814–26. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2019_33_415

46. Soderholm JJ, Socada JL, Rosenstrom TH, Ekelund J, Isometsa E. Borderline personality disorder and depression severity predict suicidal outcomes: A six-month prospective cohort study of depression, bipolar depression, and borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2023) 148:222–32. doi: 10.1111/acps.13586

47. Qadeer Shah A, Prasad D, Caropreso L, Frey BN, de Azevedo Cardoso T. The comorbidity between Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. (2023) 164:304–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.06.009

48. Carpenter RW, Wood PK, Trull TJ. Comorbidity of borderline personality disorder and lifetime substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample. J Pers Disord. (2016) 30:336–50. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2015_29_197

49. Gonzalez RA, Igoumenou A, Kallis C, Coid JW. Borderline personality disorder and violence in the UK population: categorical and dimensional trait assessment. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:180. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0885-7

Keywords: personality disorder, borderline trait, self-report, mood disorders, schizophrenia

Citation: Lin Y, Guo Z, Zhou Y, Wei Y, Xu L, Tang X, Wang Z, Hu Y, Wang J, Mei Y, Wu H, Luo Y and Zhang T (2024) Distribution of self-reported borderline personality disorder traits symptoms in a large-scale clinical population. Front. Psychiatry 15:1424966. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1424966

Received: 29 April 2024; Accepted: 06 June 2024;

Published: 25 June 2024.

Edited by:

Gonzalo Haro, Universidad CEU Cardenal Herrera, SpainReviewed by:

Mehmet Hamdi Örüm, Elazığ Eğitim ve Araştırma Hastanesi, TürkiyeYangyang Xu, Xiamen Xianyue Hospital, China

Copyright © 2024 Lin, Guo, Zhou, Wei, Xu, Tang, Wang, Hu, Wang, Mei, Wu, Luo and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: TianHong Zhang, emhhbmdfdGlhbmhvbmdAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Yi Mei, bWVpeWkyMzRAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=; YanLi Luo, bHVvbHVveWFubGlAMTYzLmNvbQ==; HaiSu Wu, d3VoYWlzdTA1QDE2My5jb20=

†These authors contributed equally to this work

Yong Lin1†

Yong Lin1† TianHong Zhang

TianHong Zhang