94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry, 27 June 2024

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1420632

This article is part of the Research TopicCommunity Series In Mental-Health-Related Stigma and Discrimination: Prevention, Role, and Management Strategies, Volume IIIView all 19 articles

Background: Few studies have explored the associated factors of attitudes of nonpsychiatric nurses towards mental disorders. Therefore, this study is aimed to evaluate the attitudes of nonpsychiatric nurses towards mental disorders and especially explore the association between psychiatric clinical practice and these attitudes.

Methods: A total of 1324 nonpsychiatric nurses and students majoring in nursing were recruited through an online questionnaire from December 2021 to March 2022 in Sichuan Province, China. Demographic information, personal care experience, psychiatric nursing education and the Community Attitudes towards the Mentally Ill (CAMI) were collected. A higher score indicates a stigmatizing attitude in the authoritarianism and social restrictiveness (SR) subscales and a positive attitude in the benevolence and community mental health ideology (CMHI) subscales. Multivariate linear regression was employed to analyze associated factors of attitudes towards mental disorders, and hierarchical linear regression was used to analyze the association between psychiatric clinical practice and the attitudes towards mental disorders.

Results: Under the control of confounders, high education level, long residence in urban and personal care experience were positively correlated with score of authoritarianism and SR (p < 0.05), and negatively correlated with score of benevolence (p < 0.05). Long residence in urban and personal care experience were negatively correlated with score of CMHI (p < 0.05). Hierarchical linear regression analysis showed that after adjusting for demographic information, psychiatric clinical practice was associated with lower score of benevolence (B = -0.09, 95%CI = -0.17 ~ -0.003, p = 0.043) and CMHI (B = -0.09, 95%CI = -0.17 ~ -0.01, p = 0.027), but the initial associations between psychiatric clinical practice and authoritarianism, SR disappeared.

Conclusions: High education level, long residence in urban, personal care experience and the psychiatric clinical practice were associated with the discrimination of nonpsychiatric nurses towards mental disorders. Further exploring practical strategies to optimize the psychiatric clinical practice experience of nonpsychiatric nurses could help improve their attitudes towards mental disorders.

Mental disorders are common worldwide, and their incidence has been rising globally (1). According to a recent national survey (2), the estimated 12-month prevalence and lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in China were 9.3% and 16.6%, respectively. The long and recurrent course of mental disorders leads to the shortening of people’s lifespans and the decline of their quality of life (3). Early detection and timely intervention from mental health professionals are crucial to improve the prognosis of mental disorders. As the group with the most direct and longest contact with patients in mental health services, nurses play a key role in both parts. Therefore, as a part of the healthcare front role, whether nurses discriminate against mental disorders or not could affect the patients’ further medical behavior, which in turn affects the early diagnosis and treatment.

The stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination towards mental disorders were stigma of mental disorders, which were often reflected through behavior of avoidance and social distance (4, 5). Mental health stigma poses a significant challenge on early diagnosis, timely treatment, treatment compliance, recovery of mental disorders and so on (6, 7). Recent researches have revealed that nursing students may regard mental disorders as unpredictable, potentially dangerous, and untreatable (8, 9). Therefore, they may exhibit a preference for maintaining social distance from patients, which prevents patients from seeking mental health services (10, 11). The nurses’ attitudes towards mental disorders have a significant impact on their behavior of coping with mental disorders, which in turn affect help-seeking behavior of patients (12). However, most patients with psychiatric symptoms initially seek help from nonpsychiatric professionals in general hospitals rather than psychiatrists (13). Therefore, as the gatekeepers to the mental health service by influencing the help-seeking behavior of patients, whether the nonpsychiatric nurses receive standardized training is vital for how to guide psychiatric patients to seek for mental health services.

Previous studies explored the attitudes of psychiatric nurses towards mental disorders and found that the attitudes of psychiatric nurses to patients with mental disorders were basically as negative as those of the general population, but were significantly more negative and stereotypical than those of other mental health professionals, such as psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers (14–16). In addition, a cross-sectional study noted that psychiatric nurses’ attitudes towards mental disorders were significantly associated with their clinical experience in mental health services, i.e., the more clinical experience they had, the more positive their attitudes towards mental disorders were (17). The results of these studies suggested that attitudes towards mental disorders might be related to the contents and forms of psychiatric education. Despite extensive research on psychiatric nurses’ attitudes, only a few studies have explored the attitudes of nonpsychiatric nurses towards mental disorders.

A cross-sectional study in Qatar found that nurses had more negative attitudes towards patients with mental disorders than doctors, and nonpsychiatric nurses had an even higher level of sigma than psychiatric nurses (18). However, another study on the attitudes of Finnish nonpsychiatric nurses showed positive attitudes (19). This evidence indicated that culture might contribute significantly to stigmatizing patients with mental disorders (20). Compared with Western culture, Chinese people emphasize “face culture” and interpersonal relationships, so stigma against mental disorders may be more common in Chinese society (21, 22). A recent survey in China has found that nonpsychiatric nurses working in general hospitals adopted stigmatizing attitudes towards mental disorders (23). However, the association between psychiatric clinical practice and the attitudes of nonpsychiatric nurses towards mental disorders has not been reported, so there is an urgent need to explore the association between psychiatric clinical practice and the attitudes of nonpsychiatric nurses towards mental disorders.

The purpose of China’s undergraduate level nursing education is to cultivate general nurses. Typically, undergraduate nursing students learn about mental disorders through two courses. The first is psychiatric nursing course, which covers the basics of mental disorders. Secondly, nursing students must complete clinical practice for no less than 40 weeks in the final year before graduation. They will rotate to different departments, including psychiatry nursing, where they can contact and participate in the clinical care of patients with mental disorders under the supervision of psychiatric nurses (24). There is evidence that contact with mental disorder, including direct contact, indirect filmed contact or educational email, can change nurses’ attitudes towards mental disorders in a positive way (25, 26). A study conducted in China found that having clinical practice experiences in psychiatric clinics contributed to improving nursing students’ attitudes towards mental disorders (21). Although professional contact (under the guidance of mental health professionals) with mental disorders of nonpsychiatric nurse is almost exclusively in psychiatric nursing education, nonpsychiatric nurses may be involved in the care of mental disorders at a personal level (e.g. family members, friends, etc.), which may also have an impact on their attitudes towards mental disorders (27). However, few studies explore the association between these factors and the attitudes towards patients with mental disorders concerning Chinese nonpsychiatric nurses.

Given these backgrounds, in this study we aim to evaluate the attitudes of nonpsychiatric nurses towards mental disorders, identify associated factors of attitudes towards mental disorder and further explore the association between psychiatric clinical practice and the attitudes of nonpsychiatric nurses towards patients with mental disorders.

This was a multicenter cross-sectional study investigating attitudes towards mental disorders among nonpsychiatric nurses by using multistage sampling. To avoid bias in single point sampling, cluster random sampling was adopted to separately select 2 public nursing schools and 1 hospital from 25 public nursing schools and 13 hospitals by lottery in Chengdu and Mianyang, Sichuan Province, China. Participants were recruited by convenience sampling from these institutions. Eligible participants were (1) people aged 18 and over, (2) finished the “Psychiatric Nursing” course at school. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) psychiatric nurses and (2) students who had not studied the “Psychiatric Nursing” course. Based on whether participants had experienced psychiatric clinical practice, they were divided into two groups: one group with psychiatric clinical practice and the other group without psychiatric clinical practice.

The link of an anonymous online survey, posted on Questionnaire Star Platform (https://www.wjx.cn/), was sent to nurse managers and nursing faculty at the selected institutions from December 2021 to March 2022. They forwarded it to nonpsychiatric nurses and nursing interns who had not been to a psychiatric department or mental health center, respectively. Informed consent, inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria were on the first page of the online survey. When they finished reading this, participants clicked the “Agree” button to indicate their consent to participate in the study, and the questionnaire appeared. In the process of filling in the questionnaire, if there is any missing item, it cannot be submitted, and the system will mark the missing item for participants to fill in. A total of 1355 valid questionnaires were retrieved, excluding 15 questionnaires from nurses working in the mental health center and 16 from nursing interns who had working experience in a psychiatric department or mental health center. Finally, 1324 questionnaires were included in this study. All data can only be obtained online by researchers publishing the questionnaires.

A Self-administered questionnaire was used to collect participants’ demographic data, personal care experience and psychiatric nursing education. Demographic data included identity (including nurses and nurse interns), age, gender, working department, education level, marital status, only child status and long-term residence. Psychiatric nursing education was identified by the question “What kind of psychiatric nursing education have you received?” Participants should choose “Psychiatric course only” or “Psychiatric course and clinical practice in psychiatric department (at least 4 weeks to 3 months)”. Personal care experience was identified by the answer of “yes” to the question “Have you ever been involved in caring for someone diagnosed with mental disorders (in a nontherapeutic relationship), such as a family member, friend or neighbor”?

The CAMI was used to measure participants’ attitudes towards mental disorders (28). It consists of 40 items, which are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree, depending on how much one agrees or disagrees with the items. It was translated into Chinese in 1998 (29). The CAMI examines four dimensions of attitudes towards mental disorders, namely, authoritarianism, social restrictiveness (SR), benevolence and community mental health ideology (CMHI). Authoritarianism refers to the view that mental disorders need coercive treatment and SR involves the view that patients with mental disorders are a threat to society, which indicates negative attitudes towards mental disorders. The higher the score is, the worse the attitude is. Benevolence reflects sympathy for mental disorders, and the CMHI is about mental health services and the acceptance of mental disorders in the community. Both of them represent positive attitudes towards mental disorders, with higher scores indicating higher acceptance. The CAMI presenting good and acceptable reliability and validity was initially used in community members and then applied to mental health professionals, nurses, students, etc. (30, 31). Previous studies showed that the scale had acceptable reliability (the alpha coefficient for each of the four scales varied from 0.68 to 0.88) and concurrent validity (29, 32).

All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 26.0 software. Participants’ general information was analyzed with descriptive statistical methods. Categorical variables were described as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were described as the mean and standard deviation (SD). Participants were divided into different age groups on a 10-year line. All variables were subjected to univariable logistic analysis to compare the demographic characteristics, personal care experience and attitudes towards mental disorders between nursing education with and without psychiatric clinical practice. Multivariate linear regression was used to identify characteristics that were associated with the four dimensions of attitudes towards mental disorders. Hierarchical linear regression models were conducted to assess associations between psychiatric nursing clinical practice and attitudes towards mental disorders: authoritarianism, SR, benevolence, CMHI. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for age, education level, marital status and long-term residence. Model 3 was further adjusted for identity and personal care experience. For all analyses, two-sided p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

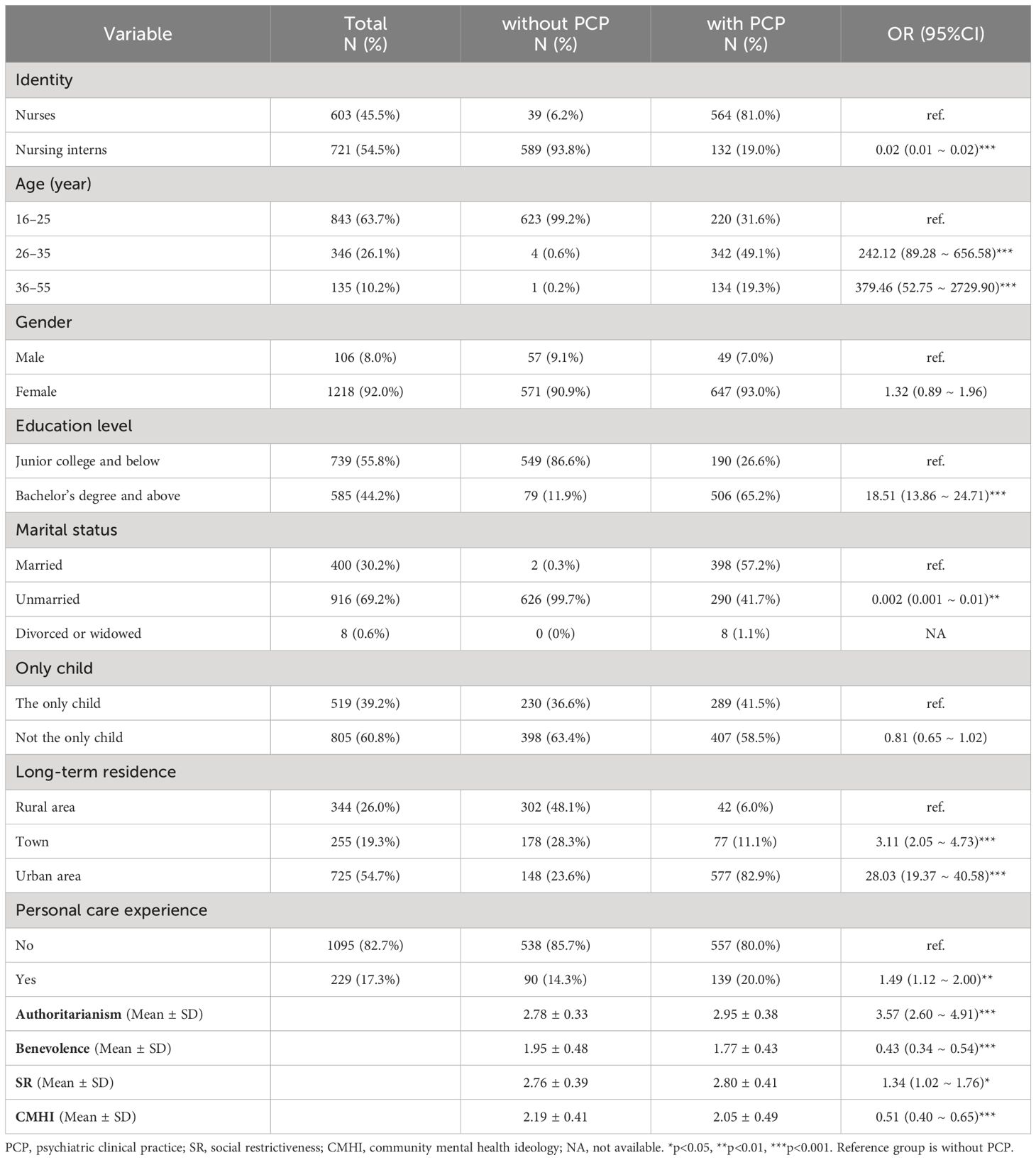

In total, 1324 participants were involved in this study, of whom without psychiatric clinical practice group (those who have had only psychiatric nursing course) mainly consisted of nursing interns whose average age was relatively young. The majority of them were with junior college degrees or below, unmarried and living in rural areas. By contrast, the psychiatric clinical practice group (those who have had both psychiatric nursing course and psychiatric nursing clinical practice) mainly consisted of nurses with older average age. The majority of them had bachelor’s degree and above, married and living in rural areas (presented in Table 1). Identity, age, education level, marital status, long-term residence, personal care experience differed significantly between the two groups (p < 0.05).

Table 1 Comparison of demographic characteristics, personal care experience and attitudes towards mental disorders between nursing education with and without psychiatric clinical practice (N=1324).

The CAMI subscale scores of nonpsychiatric nurses under two types of psychiatric nursing education showed that the scores of psychiatric clinical practice group were significantly lower than those of without psychiatric clinical practice group in benevolence (OR = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.34 ~ 0.54, p < 0.001) and CMHI (OR = 0.51, 95%CI = 0.40 ~ 0.65, p < 0.001), and significantly higher in authoritarianism (OR = 3.57, 95%CI = 2.60 ~ 4.91, p < 0.001) and SR (OR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.02 ~ 1.76, p = 0.035) (Table 1).

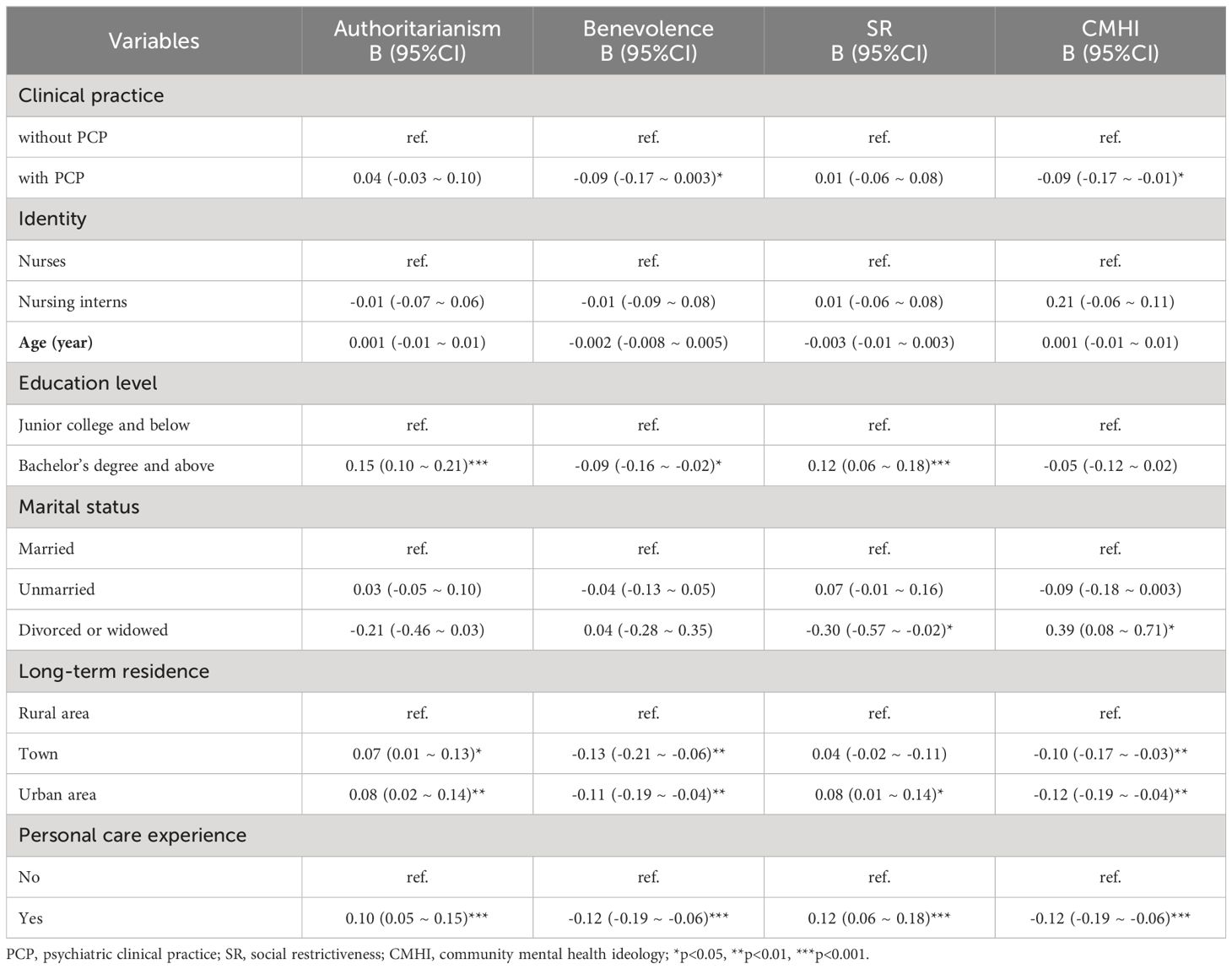

Multivariate linear regression was carried out to test whether the independent variables with the above differences had an impact on the four subscales of CAMI. The results showed that authoritarianism was positively correlated with high education level (B = 0.15, 95%CI = 0.10 ~ 0.21, p < 0.001), long residence in urban (B = 0.08, 95%CI = 0.02 ~ 0.14, p = 0.009) and personal care experience (B = 0.10, 95%CI = 0.05 ~ 0.15, p < 0.001). Benevolence was negatively correlated with psychiatric clinical practice (B = -0.09, 95%CI = -0.17 ~ 0.003, p = 0.043), high education level (B = -0.09, 95%CI = -0.16 ~ -0.02, p = 0.013), long residence in urban (B = -0.11, 95%CI = -0.19 ~ -0.04, p = 0.004) and personal care experience (B = -0.12, 95%CI = -0.19 ~ -0.06, p < 0.001). SR was positively correlated with high education level (B = 0.12, 95%CI = 0.06 ~ 0.18, p < 0.001), long residence in urban (B = 0.08, 95%CI = 0.01 ~ 0.14, p = 0.021) and personal care experience (B = 0.12, 95%CI = 0.06 ~ 0.18, p < 0.001). CMHI was negatively correlated with long residence in urban (B = -0.12, 95%CI = -0.19 ~ -0.04, p = 0.003), personal care experience (B = -0.12, 95%CI = -0.19 ~ -0.06, p < 0.001) and psychiatric clinical practice (B = -0.09, 95%CI = -0.17 ~ -0.01, p = 0.027). Results were shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Associations between factors and attitudes towards mental disorders among nonpsychiatric nurses (N=1324).

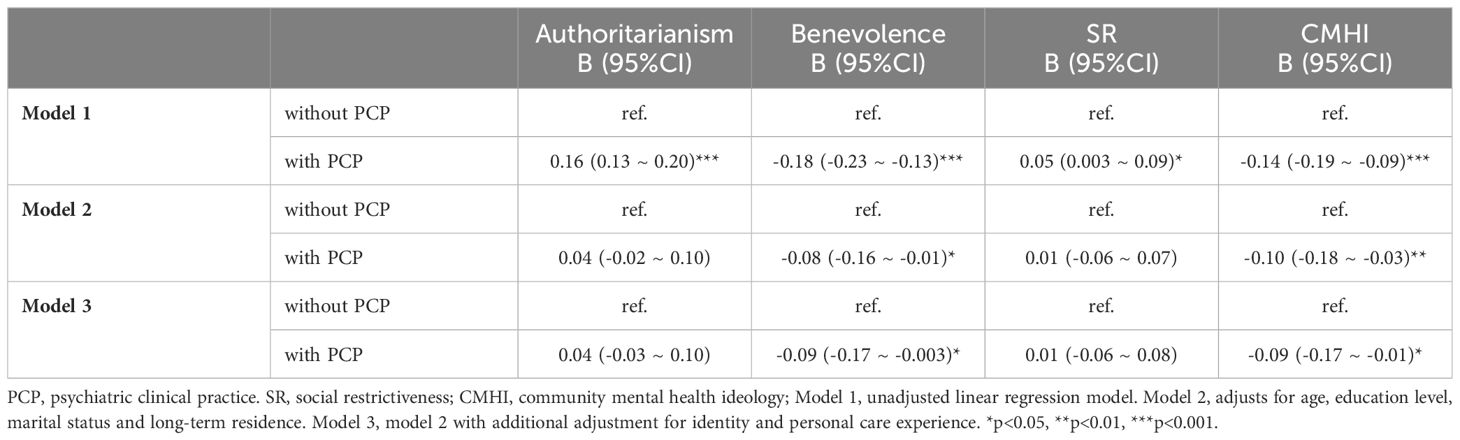

Table 3 showed the results from the hierarchical linear regression models for the relationship between CAMI subscale scores and two types of psychiatric nursing education in nonpsychiatric nurse burden while controlling for contextual variables. Psychiatric clinical practice was initially associated with higher score of authoritarianism (B = 0.16, 95%CI = 0.13 ~ 0.20, p < 0.001) and SR (B = 0.05, 95%CI = 0.003 ~ 0.09, p = 0.035), lower score of benevolence (B = -0.18, 95%CI = -0.23 ~ -0.13, p < 0.001) and CMHI (B = -0.14, 95%CI = -0.19 ~ -0.09, p < 0.001) (Model 1). As for the initial associations between psychiatric clinical practice status and authoritarianism, SR disappeared after adjusting for age, education level, marital status and long-term residence (Model 2), as well as further adjusted for identity and personal care experience (Model 3).

Table 3 Relationship between CAMI subscale scores and two types of psychiatric nursing education among nonpsychiatric nurses (N=1324).

To our knowledge, this study is one of the few to investigate the attitudes of nonpsychiatric nurses (nonpsychiatric nurses and nursing interns) towards mental disorders and factors associated with their attitudes in China. Although we originally found that those taking psychiatric clinical practice were more likely to exhibit authoritarianism and SR, and less likely to exhibit benevolence and CMHI towards mental disorders than those without psychiatric clinical practice. Only benevolence and CMHI were still correlated with psychiatric clinical practice after adjusting confounding factors. In addition, education level, long-term residence, personal care experience and psychiatric nursing education were associated with different dimensions of attitudes to mental disorders.

This study showed that the nonpsychiatric nurses who received psychiatric nursing clinical practice in the psychiatric department had less empathy and community acceptance towards mental disorders than those who did not. This was inconsistent with previous findings. Some previous studies found that psychiatric nursing clinical practice could positively affect the attitudes of nursing students towards mental disorders (33–36). However, others reported an negative effect, which suggested that the effect of clinical practice still needed to be explored (9, 37). Such inconsistency might be caused by different states of the contacted patients (38, 39). The systematic review emphasized that interacting with stable patients (such as in a state of recovery) in a relatively safe clinical environment helped to challenge the stereotypes of mental disorders (40). However, the states of contacted patients of this study were not restricted. Therefore, future studies should investigate whether the state of patients will impact the effects of psychiatric nursing clinical practice on the attitudes of nursing students to give insight into the reform of psychiatric nursing education.

In addition, the timing of assessment of attitudes towards mental disorders might also contribute to the inconsistency (41). The systematic review found that the effectiveness of clinical practice in promoting health care students’ attitudes towards mental disorders was short-term, disappearing in one-year follow-up (40). The assessment of attitudes towards mental disorders were conducted years after the completion of psychiatric nursing clinical practice for nonpsychiatric nurses. Therefore, future studies should assess the short-term and long-term effects of psychiatric nursing clinical practice. Moreover, to sustainably improve nonpsychiatric nurses’ attitudes towards mental disorders, psychiatric nursing education should be added to their professional education.

Our study found that nonpsychiatric nurses with higher education levels were more likely to agree that patients with mental disorders were inferior, should be coerced into treatment or were a threat to society and were less likely to empathize with such groups. This was in contrast to most previous studies: with the improvement in nursing education level, mental health literacy also gradually improved (42, 43). However, a recent study on the care behavior of emergency department nurses towards mental disorders found a significant inverse correlation between level of education and care behavior, which is similar to our results (44). This result may be due to the fact that nurses with higher levels of education, who play more administrative roles, have less contact time with mental disorders (45).

This study also showed that individuals who lived for a long time in rural areas had significantly better attitudes towards mental disorders than people who lived in urban areas. This was supported by the results of previous studies showing that medical students from rural areas had a better attitude to patients with mental disorders than those from urban areas (46, 47). Mental health services and facilities in urban communities are more mature and comprehensive, and there is greater dissemination of knowledge about mental disorders (48). However, the media in China are in general filled with negative images of psychiatric patients, which can powerfully influence the urban residents’ attitudes towards mental disorders (49). In addition, there is a deep-rooted family collectivism in China’s rural areas, where families are likely to come together to take care of the sick (50), which may be related to a reduction in stigma.

Furthermore, we found that nonpsychiatric nurses who had been involved in the care for mental disorders on a personal level (as family members, friends or neighbors) had more negative attitudes towards these people; that is, they considered people diagnosed with mental disorders to be treated compulsively, a threat to society, and had less empathy and acceptance towards them. The reason for this phenomenon may be related to the personal care situation in which the nonpsychiatric nursing groups were involved. Nonpsychiatric nursing groups do not care for mental disorders on a full-time basis but as support to control their abnormal behaviors or seek medical assistance when their mental condition deteriorates, which might provide an inadequate and incorrect view of mental disorders and reinforce stereotypes. This suggests that the quality of contact with people diagnosed with mental disorders greatly affects people’s attitudes towards mental disorders (51, 52). Not having extensive professional practice in dealing with the symptoms of mental disorders can be frustrating and resistant to these people, which may lead to the belief that mental disorders are unpredictable and untreatable (53). Therefore, clinical practice lecturers should be aware of students’ relevant nursing experiences at the beginning of clinical practice, provide them with counseling and support, and help them overcome negative thoughts through positive practice experiences.

The study is the first in China to focus on the influence of psychiatric clinical practice on the attitudes of nonpsychiatric nurses towards mental disorders. The results revealed that the psychiatric nursing clinical practice of nonpsychiatric nurses did not improve the discrimination of nonpsychiatric nurses towards mental disorders, suggesting that psychiatric nursing clinical practice should be further strengthened. Meanwhile, this study is one of the few studies researching the factors that influence the stigma of mental disorders in nonpsychiatric nurses, providing new insights into further studies in the field. However, there were also some limitations to this study. First, although this was a cross-sectional study and couldn’t explain the causal relationship between variables, we collected questionnaires from different centers and used reliable evaluation tools to minimize the bias in horizontal surveys. Second, the samples of this study were all from cities in southwest China, so the generalization of the conclusion needs to be done with caution and may not represent the whole country. Third, the total number and proportion of eligible nurses and nursing interns within selected institutions could not be determined because of the convenience sampling method in each institution, which might lead to bias in some degree.

This study showed that nonpsychiatric nurses who had taken both psychiatric nursing courses and psychiatric nursing clinical practice had a more negative attitude towards mental disorders than those who had taken only psychiatric nursing courses. Besides, education level, personal care experience and long-term residence were associated with attitudes towards mental disorders among nonpsychiatric nurses in China. These suggested that psychiatric nursing clinical practice education should be improved, such as offering them a contact with patients during the remission period of mental disorders, and adding psychiatric nursing to the vocational education for nonpsychiatric nurses. The quality and the duration of nursing clinical practice might affect the level of stigma, so we should actively explore better psychiatric nursing clinical practice models. During the clinical practice process, emphasis should be placed on lessening the stigma of mental disorders among nursing interns, and active guidance should be given to them on correctly understanding the negative effects of mental disorders, aiming to reduce the discrimination towards mental disorders among nonpsychiatric nurses. Further research could take longitudinal studies to explore the association between psychiatric nursing clinical practice and the attitudes of nonpsychiatric nurses towards mental disorders. And it is necessary to explore practical strategies to optimize the psychiatric nursing clinical practice experience of nonpsychiatric nurses, thus to improve their attitudes towards mental disorders.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ID: 2019–686). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Q-KW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. XW: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Resources, Validation. Y-JQ: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. W-XB: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. X-CC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation. J-JX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Validation.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2023YFS0291).

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank all nurses who participated in the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. (2022) 9:137–50. doi: 10.1016/s2215–0366(21)00395–3

2. Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:211–24. doi: 10.1016/s2215–0366(18)30511-x

3. Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Agerbo E, Holtz Y, Erlangsen A, Canudas-Romo V, et al. A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: A nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet (London England). (2019) 394:1827–35. doi: 10.1016/s0140–6736(19)32316–5

4. Valery KM, Prouteau A. Schizophrenia stigma in mental health professionals and associated factors: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 290:113068. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113068

5. Fino E, Agostini A, Mazzetti M, Colonnello V, Caponera E, Russo PM. There is a limit to your openness: mental illness stigma mediates effects of individual traits on preference for psychiatry specialty. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:775. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00775

6. The L. The health crisis of mental health stigma. Lancet (London England). (2016) 387:1027. doi: 10.1016/s0140–6736(16)00687–5

7. Rezvanifar F, Shariat SV, Amini H, Rasoulian M, Shalbafan M. A scoping review of questionnaires on stigma of mental illness in persian. Iranian J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. (2020) 26:240–58. doi: 10.32598/ijpcp.26.2.2619.1

8. Stuhlmiller C, Tolchard B. Understanding the impact of mental health placements on student nurses' Attitudes towards mental illness. Nurse Educ Pract. (2019) 34:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2018.06.004

9. Chang S, Ong HL, Seow E, Chua BY, Abdin E, Samari E, et al. Stigma towards mental illness among medical and nursing students in Singapore: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e018099. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017–018099

10. Shi W, Shen Z, Wang S, Hall BJ. Barriers to professional mental health help-seeking among chinese adults: A systematic review. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:442. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00442

11. Zhao K, He Y, Zeng Q, Ye L. Factors of mental health service utilization by community-dwelling adults in Shanghai, China. Community Ment Health J. (2019) 55:161–7. doi: 10.1007/s10597–018-0352–7

12. Lien YY, Lin HS, Tsai CH, Lien YJ, Wu TT. Changes in attitudes toward mental illness in healthcare professionals and students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:4655. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16234655

13. Wu Q, Luo X, Chen S, Qi C, Yang WFZ, Liao Y, et al. Stigmatizing attitudes towards mental disorders among non-mental health professionals in six general hospitals in hunan province. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:946. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00946

14. Economou M, Peppou LE, Kontoangelos K, Palli A, Tsaliagkou I, Legaki EM, et al. Mental health professionals' Attitudes to severe mental illness and its correlates in psychiatric hospitals of attica: the role of workers' Empathy. Community Ment Health J. (2020) 56:614–25. doi: 10.1007/s10597–019-00521–6

15. Happell B Rn RPNBADEBEMEP, Scholz B Bhsci P, Bocking JB, Phil BS, Comm S, Platania-Phung C Ba P. Promoting the value of mental health nursing: the contribution of a consumer academic. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2019) 40:140–7. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2018.1490834

16. Koutra K, Mavroeides G, Triliva S. Mental health professionals' Attitudes towards people with severe mental illness: are they related to professional quality of life? Community Ment Health J. (2022) 58:701–12. doi: 10.1007/s10597–021-00874-x

17. Han KH, Sun CK, Cheng YS, Chung W, Kao CC. Impacts of extrinsic and intrinsic factors on psychiatric nurses' Spiritual care attitudes. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2023) 30:481–91. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12878

18. Ghuloum S, Mahfoud ZR, Al-Amin H, Marji T, Kehyayan V. Healthcare professionals' Attitudes toward patients with mental illness: A cross-sectional study in Qatar. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:884947. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.884947

19. Ihalainen-Tamlander N, Vähäniemi A, Löyttyniemi E, Suominen T, Välimäki M. Stigmatizing attitudes in nurses towards people with mental illness: A cross-sectional study in primary settings in Finland. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2016) 23:427–37. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12319

20. Alaqeel M, Moukaddem A, Alzighaibi R, Alharbi A, Alshehry M, Alsadun D. The level of the stigma of medical students at king saud bin abdulaziz university for health sciences, towards mentally ill patients. J Family Med Primary Care. (2020) 9:5665–70. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1099_20

21. Zhang X, Wu Y, Sheng Q, Shen Q, Sun D, Wang X, et al. The clinical practice experience in psychiatric clinic of nursing students and career intention in China: A qualitative study. J Prof Nurs. (2021) 37:916–22. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.07.013

22. Yu M, Cheng S, Fung KP, Wong JP, Jia C. More than mental illness: experiences of associating with stigma of mental illness for chinese college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:864. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020864

23. Li L, Lu S, Xie C, Li Y. Stigmatizing Attitudes toward Mental Disorders among Non-Mental Health Nurses in General Hospitals of China: A National Survey. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1180034. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1180034

24. Shen L, Zhang X, Chen J, Yang Y, Hu R. Exploring the experience of undergraduate nursing students following placement at psychiatric units in China: A phenomenological study. Nurse Educ Pract. (2023) 72:103748. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103748

25. Gu L, Xu D, Yu M. Mediating effects of stigma on the relationship between contact and willingness to care for people with mental illness among nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. (2021) 103:104973. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104973

26. Lien YY, Lin HS, Lien YJ, Tsai CH, Wu TT, Li H, et al. Challenging mental illness stigma in healthcare professionals and students: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Psychol Health. (2021) 36:669–84. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2020.1828413

27. Kolb K, Liu J, Jackman K. Stigma towards patients with mental illness: an online survey of United States nurses. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2023) 32:323–36. doi: 10.1111/inm.13084

28. Taylor SM, Dear MJ. Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophr Bull. (1981) 7:225–40. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.2.225

29. Sévigny R, Yang W, Zhang P, Marleau JD, Yang Z, Su L, et al. Attitudes toward the mentally ill in a sample of professionals working in a psychiatric hospital in Beijing (China). Int J Soc Psychiatry. (1999) 45:41–55. doi: 10.1177/002076409904500106

30. Chambers M, Guise V, Välimäki M, Botelho MA, Scott A, Staniuliené V, et al. Nurses' Attitudes to mental illness: A comparison of a sample of nurses from five european countries. Int J Nurs Stud. (2010) 47:350–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.08.008

31. Tong Y, Wang Z, Sun Y, Li S. Psychometric properties of the chinese version of short-form community attitudes toward mentally illness scale in medical students and primary healthcare workers. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:337. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00337

32. Song LY, Chang LY, Shih CY, Lin CY, Yang MJ. Community attitudes towards the mentally ill: the results of a national survey of the Taiwanese population. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2005) 51:162–76. doi: 10.1177/0020764005056765

33. Al-Maraira OA. The impact of psychiatric education and clinical practice on students' Beliefs toward people with mental illnesses. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2022) 40:56–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2022.05.001

34. Fernandes JB, Família C, Castro C, Simões A. Stigma towards people with mental illness among portuguese nursing students. J Personalized Med. (2022) 12:326. doi: 10.3390/jpm12030326

35. Foster K, Giandinoto JA, Furness T, Blanco A, Withers E, Alexander L. 'Anyone can have a mental illness': A qualitative inquiry of pre-registration nursing students' Experiences of traditional mental health clinical placements. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2021) 30:83–92. doi: 10.1111/inm.12808

36. Foster K, Withers E, Blanco T, Lupson C, Steele M, Giandinoto JA, et al. Undergraduate nursing students' Stigma and recovery attitudes during mental health clinical placement: A pre/post-test survey study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2019) 28:1065–77. doi: 10.1111/inm.12634

37. Linden M, Kavanagh R. Attitudes of qualified vs. Student mental health nurses towards an individual diagnosed with schizophrenia. J Adv Nurs. (2012) 68:1359–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365–2648.2011.05848.x

38. De Witt C, Smit I, Jordaan E, Koen L, Niehaus DJH, Botha U. The impact of a psychiatry clinical rotation on the attitude of South African final year medical students towards mental illness. BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:114. doi: 10.1186/s12909–019-1543–9

39. Happell B, Gaskin CJ, Byrne L, Welch A, Gellion S. Clinical placements in mental health: A literature review. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2015) 36:44–51. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2014.915899

40. Chia NN, Kannusamy P, Klainin-Yobas P. The effectiveness of mental health-related theoretical education and clinical placement in mental health settings in changing the attitudes of health care students towards mental illness: A systematic review. JBI Library Syst Rev. (2012) 10:1–19. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2012–286

41. Mohebbi M, Nafissi N, Ghotbani F, Khojasteh Zonoozi A, Mohaddes Ardabili H. Attitudes of medical students toward psychiatry in eastern mediterranean region: A systematic review. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:1027377. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1027377

42. Kong L, Fan W, Xu N, Meng X, Qu H, Yu G. Stigma among Chinese Medical Students toward Individuals with Mental Illness. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. (2020) 58:27–31. doi: 10.3928/02793695–20191022–03

43. Saito AS, Creedy DK. Determining mental health literacy of undergraduate nursing students to inform learning and teaching strategies. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2021) 30:1117–26. doi: 10.1111/inm.12862

44. McIntosh JT. Emergency department nurses' Perceptions of caring behaviors toward individuals with mental illness: A secondary analysis. Int Emergency Nurs. (2023) 68:101271. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2023.101271

45. Shahif S, Idris DR, Lupat A, Abdul Rahman H. Knowledge and attitude towards mental illness among primary healthcare nurses in Brunei: A cross-sectional study. Asian J Psychiatry. (2019) 45:33–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.08.013

46. O'Ferrall-González C, Almenara-Barrios J, García-Carretero M, Salazar-Couso A, Almenara-Abellán JL, Lagares-Franco C. Factors associated with the evolution of attitudes towards mental illness in a cohort of nursing students. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2020) 27:237–45. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12572

47. Shen Y, Dong H, Fan X, Zhang Z, Li L, Lv H, et al. What can the medical education do for eliminating stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness among future doctors? Effect of clerkship training on chinese students' Attitudes. Int J Psychiatry Med. (2014) 47:241–54. doi: 10.2190/PM.47.3.e

48. Hu X, Rohrbaugh R, Deng Q, He Q, Munger KF, Liu Z. Expanding the mental health workforce in China: narrowing the mental health service gap. Psychiatr Serv (Washington DC). (2017) 68:987–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700002

49. Gu L, Ding H. A bibliometric analysis of media coverage of mental disorders between 2002 and 2022. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2023) 58:1719–29. doi: 10.1007/s00127–023-02473–5

50. Chai X, Liu Y, Mao Z, Li S. Barriers to medication adherence for rural patients with mental disorders in eastern China: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:141. doi: 10.1186/s12888–021-03144-y

51. Hsiao CY, Lu HL, Tsai YF. Factors influencing mental health nurses' Attitudes towards people with mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2015) 24:272–80. doi: 10.1111/inm.12129

52. Siu BW, Chow KK, Lam LC, Chan WC, Tang VW, Chui WW. A questionnaire survey on attitudes and understanding towards mental disorders. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. (2012) 22:18–24.

Keywords: social stigma, mental health, nursing education research, nurses, China

Citation: Wang Q-K, Wang X, Qiu Y-J, Bao W-X, Chen X-C and Xu J-J (2024) The attitudes of nonpsychiatric nurses towards mental disorders in China. Front. Psychiatry 15:1420632. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1420632

Received: 20 April 2024; Accepted: 10 June 2024;

Published: 27 June 2024.

Edited by:

Mohammadreza Shalbafan, Iran University of Medical Sciences, IranReviewed by:

Atefeh Zandifar, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, IranCopyright © 2024 Wang, Wang, Qiu, Bao, Chen and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jia-Jun Xu, eHVqaWFqdW4xMjBAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Xia-Can Chen, eGlhY2FuY2hlbjE3QHNjdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.