- 1Department of Basic and Emergency Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- 2Department of IQ Healthcare, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, Netherlands

- 3Sydney Nursing School, The University of Sydney, Darlington, NSW, Australia

- 4Department of Geriatrics, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, Netherlands

- 5Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing, School of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Randwick, NSW, Australia

- 6Department of Psychology, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- 7Department of Psychiatry, Wroclaw Medical University, Wroclaw, Poland

- 8Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Faculty of Medicine, Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, Wroclaw, Poland

- 9Department for Health Services Research, Institute for Public Health and Nursing Research, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

- 10Faculty of Nursing, University of Jember, Jember, Indonesia

- 11Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Background: Social health in the context of dementia has recently gained interest. The development of a social health conceptual framework at the individual and social environmental levels, has revealed a critical need for a further exploration of social health markers that can be used in the development of dementia intervention and to construct social health measures.

Objective: To identify social health markers in the context of dementia.

Method: This international qualitative study included six countries: Australia, Germany, Indonesia, Italy, Poland, and the Netherlands. Using purposive sampling, three to five cases per country were recruited to the study, with each case consisting of a person living with dementia, a primary informal caregiver, an active network member, and a health care professional involved in the care of the person with dementia. In-depth interviews, using an agreed topic guide, and content analysis were conducted to identify known and new social health markers. The codes were then categorized against our conceptual framework of social health.

Results: Sixty-seven participants were interviewed. We identified various social health markers, ranging from those that are commonly used in epidemiological studies such as loneliness to novel markers of social health at the individual and the social environmental level. Examples of novel individual-level markers were efforts to comply with social norms and making own choices in, for example, keeping contact or refusing support. At a social environmental level, examples of novel markers were proximity (physical distance) and the function of the social network of helping the person maintaining dignity.

Conclusions: The current study identified both well-known and novel social health markers in the context of dementia, mapped to the social health framework we developed. Future research should focus on translating these markers into validated measures and on developing social health focused interventions for persons with dementia.

1 Introduction

Dementia is acknowledged as a syndrome with multifactorial causes and multiple presentations. In relation to its development, focus on social health has recently gained interest in addition to biological (1–4) and psychological factors (5, 6). In its presentation, dementia profoundly affects the individual’s life, not only cognitively, physically and mentally, but also socially (7). Changes in social functioning often are the first signs of dementia (8, 9). During the trajectory of dementia, persons with dementia struggle with their social identity and can feel like outcasts (10). Dementia changes communication abilities and opportunities (11) and is associated with a reduction in social network size (12–15). Qualitative studies have shown how persons with dementia strive to maintain their social connections (16, 17). This illustrates the importance of social health in the context of dementia.

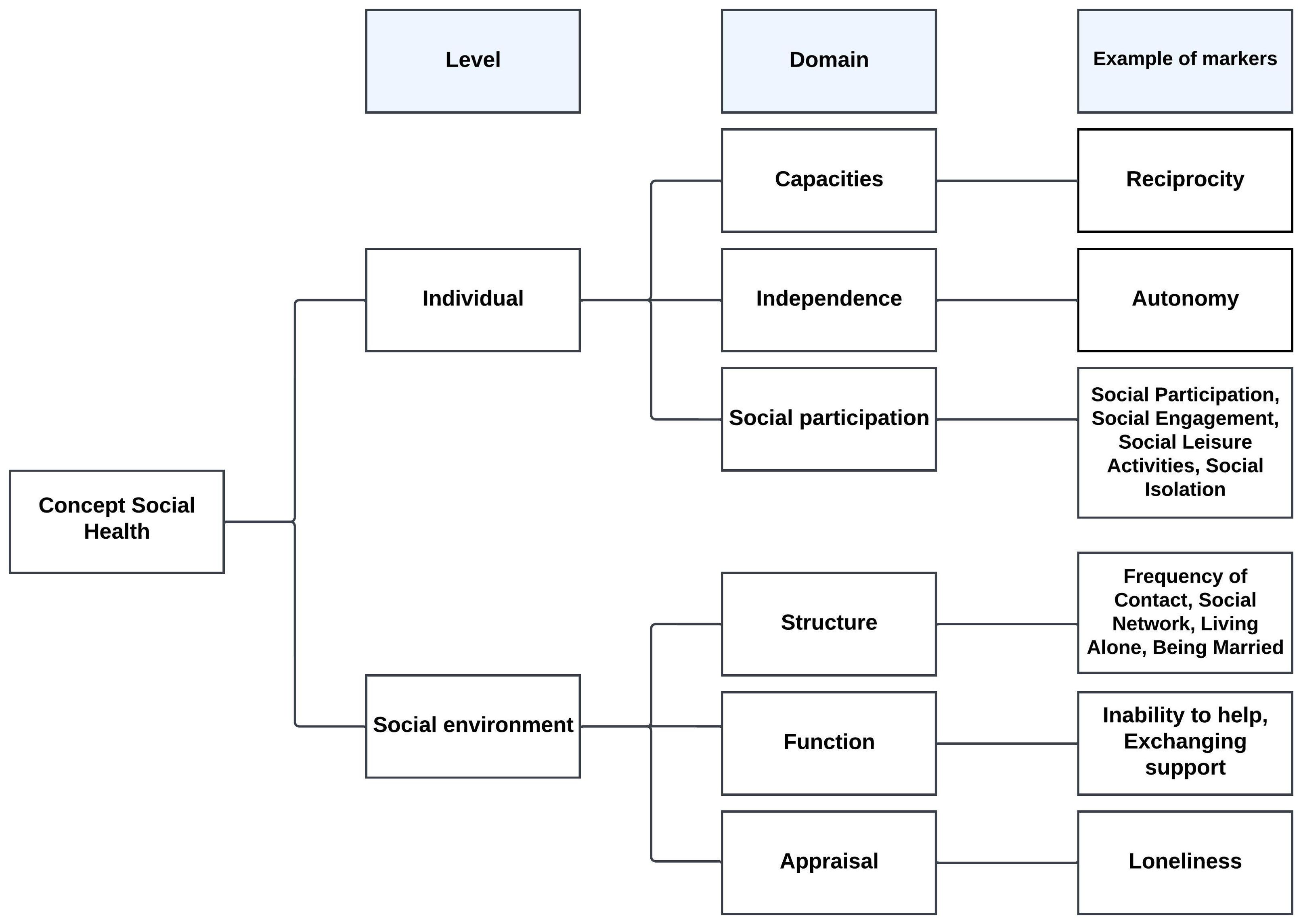

Social health is an umbrella concept: ‘It is essentially a relational concept in which wellbeing is defined on the one hand, as the impact that an individual has on others (social environment), and on the other hand as the impact that the social environment (others) has, in turn, on the individual’ (18). Social health in the context of dementia is seen as a new perspective on maintaining potential and capacity. We used the conceptual framework for social health in the context of dementia which we developed in our previous work to organize social health markers on its individual and social environmental levels (18). The next step is to identify relevant social health markers to enable measurement of social health.

The conceptual framework (18) can be used to study relationships between social health markers and cognitive functioning. Epidemiological studies have already demonstrated associations between specific social health markers (e.g., social support, social participation) and cognitive functioning and dementia risk (1, 2, 4, 19–21). A higher level of social connectivity was associated with lower cognitive decline (3, 20) and lower risk of dementia (21–23). Conversely, loneliness (1) and the lack of people to talk with on a daily basis (5, 6) were associated with cognitive decline and risk of dementia.

Both the framework (18) and epidemiological research however lack a clear articulation of relevant social health markers. Especially social health markers on the level of the individual are narrowly defined in the domains of individual’s autonomy and their capacity to fulfill their potential. Markers on the social environmental level mainly focus on the domains of network structure and social support (18). The current qualitative research aims to identify new social health markers in the context of dementia, relevant to people with dementia and their social environment. This will facilitate a better understanding of social health. New social health markers can be used for consideration of potentially modifiable protective and risk factors for development of novel interventions as well as for construction of social health measurement.

2 Method

2.1 Study context

This study was conducted as part of the ‘Social Health And Reserve in the Dementia patient journey (SHARED)’ project involving diverse disciplines including epidemiology, sociology, psychology, nursing, geriatrics, psychiatry, neuropsychiatry, and family practice. The SHARED project aims to identify the theoretical and epidemiological associations between social health markers, cognitive reserve, and dementia risk in older adults. The social health conceptual framework (18) has been developed as part of the SHARED project.

2.2 Design and setting

The study is an international qualitative study using in-depth interviews. It was conducted in: Australia (AU), Germany (GE), Indonesia (ID), Italy (IT), the Netherlands (NL), and Poland (PL). All countries had at least one researcher in their team who was experienced in conducting qualitative research and dementia research. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative studies (COREQ) checklist was used for reporting (24) (Appendix 2).

2.3 Participants and recruitment

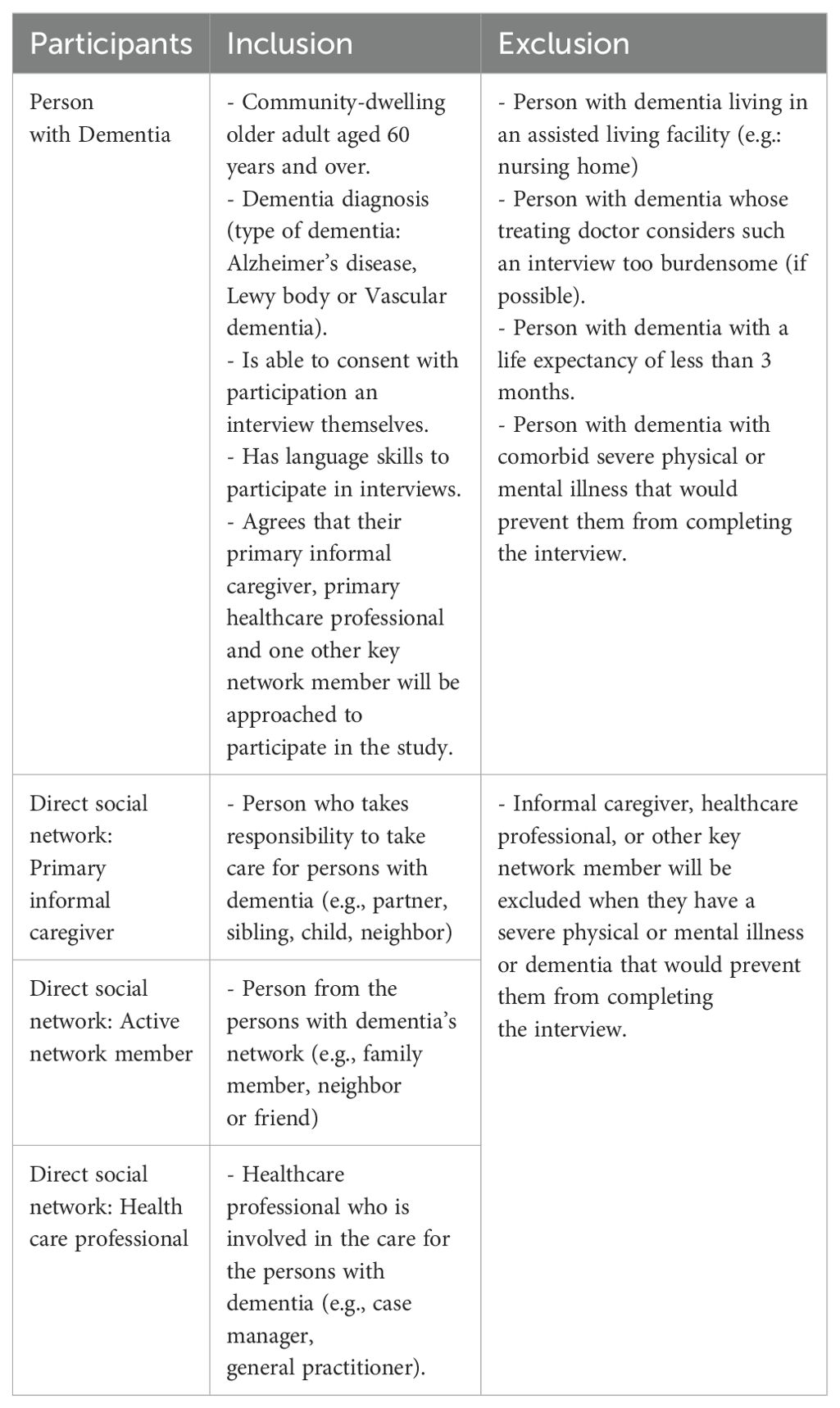

In each of the six countries, we aimed to recruit quartets consisting of person with dementia, and an associated primary informal caregiver, active network member, and health care professional. We employed purposive sampling. In the first step, participants were recruited based on inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

In the second step, we strived for a country level maximum variation of sampling taking into account age, gender, living condition (alone/with family) of the person with dementia, and types of health care professionals.

2.4 Sample size

In this international study, we aimed to identify social health markers for persons with dementia from the perspective of persons with dementia and their key social network members, irrespective of culture or socio-economic status. We therefore did not aim to achieve data saturation in each participating country, but to achieve data saturation based on the combined data of all participating countries, which we expected after three cases per country (25).

2.5 Data collection

We employed in-depth interviews guided by a participant recruitment and data collection protocol developed by the NL team. Potential participants were approached either at clinics or general practices (NL, PL and ID), or utilizing patient support networks namely Deutsche Alzheimer Gesellschaft e.V. (GE), StepUp for Dementia Research (AU) (26) and Alzheimer Café (IT). In each country, the interviews were led by experienced interviewers in their local languages (EV in NL, ML in PL, IS in GE, GO in IT, SS in AU and MSK in ID) (27).

We collected data in 2020-2021 while COVID-19 public health orders still varied amongst countries. NL and PL collected data using in-person meetings while others relied on videocalls for data collection. Participants were interviewed once only and all interviews were audio recorded. Interviewers did not know the participants prior to data collection.

The interview topic guide was developed based on a multi-country qualitative study (28), and experiences from all authors, and subsequently tested in NL prior to data collection and further refined. It included items on dementia diagnosis, social network and daily activities, influence of social network on functioning, changes in social network and interaction with social network after dementia diagnosis and influence of functioning on social network (Appendix 1).

We also collected demographic characteristics from all participants. In order to provide more information on the context of persons with dementia social engagement, social network characteristics of persons with dementia were explored and described as high, medium and poor levels per case, based on the individual’s frequency of contacts, number of people seen, appreciation, contact with the community and feeling of being socially isolated.

2.6 Data analysis

We used qualitative content analysis (29). Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim using each country’s local language. In order to enhance the feasibility to communicate to all participating countries, the transcripts were coded in English (27). To enhance objectivity, we had at least two researchers in each country who conducted coding and discussed amongst each other.

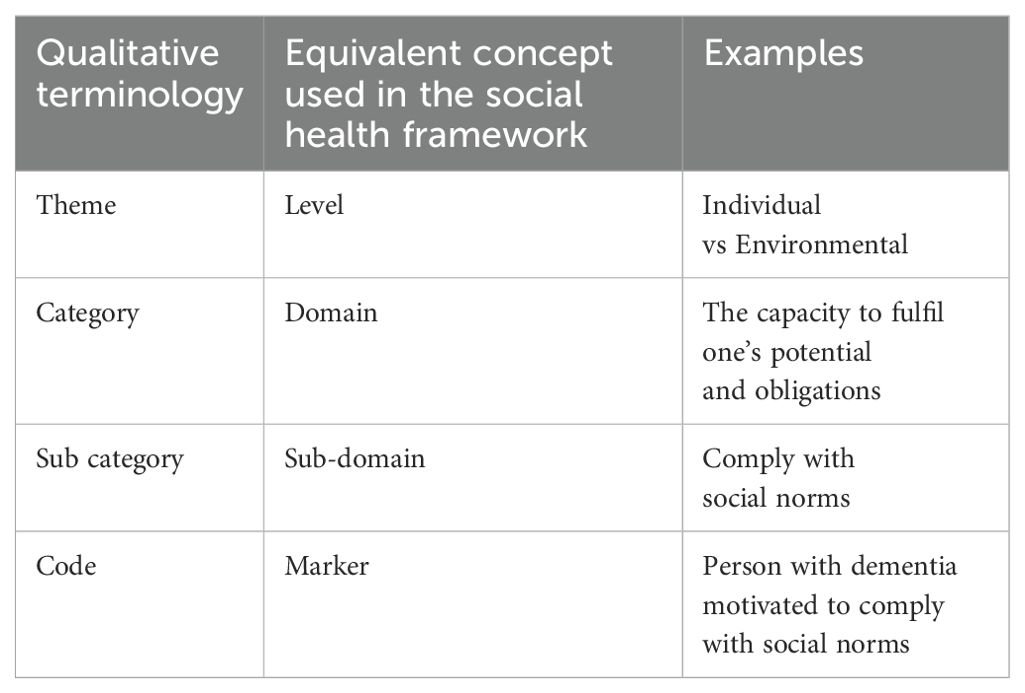

Data analysis was conducted iteratively using a codebook developed by the NL team in collaboration with all other participating countries. The codebook consisted of codes including definitions describing what is and what it is not in the scope of the code. All participating countries conducted open coding inductively. They were able to use and add codes to the codebook during the coding process, when necessary. Next, multiple meetings amongst all participating countries were conducted to iteratively revise the codebook. Codes were considered markers (Table 2). After consensus on coding was reached, we used the conceptual framework of social health (18) to cluster the codes into categories (equal with domains in the framework: Table 2) and left the possibility to formulate new categories when necessary.

The discussion ended when the consensus for coding and categorization was reached. During the coding process, some participating countries used Atlas.ti (NL, ID) to organize data while others used NVivo (AU), MAXQDA (GE) and Excel (IT, PL). Further we utilized Excel spreadsheets and an online application (Miro https://miro.com) to facilitate team discussion and categorization.

2.7 Ethical consideration

All countries used equivalent protocols and adapted to be submitted to ethical committee in each country (30). Ethical permission received from Australia (Ref: HC210100), Germany (ref. No: 2021-14/06-3), Indonesia (Ref: KE/KF/0230/ES/2021), Italy (Ref: Prot.n.170353), Poland (Ref: KB-162/2021) and the Netherlands (Ref: 2020-6153).

3 Results

3.1 Participant characteristics

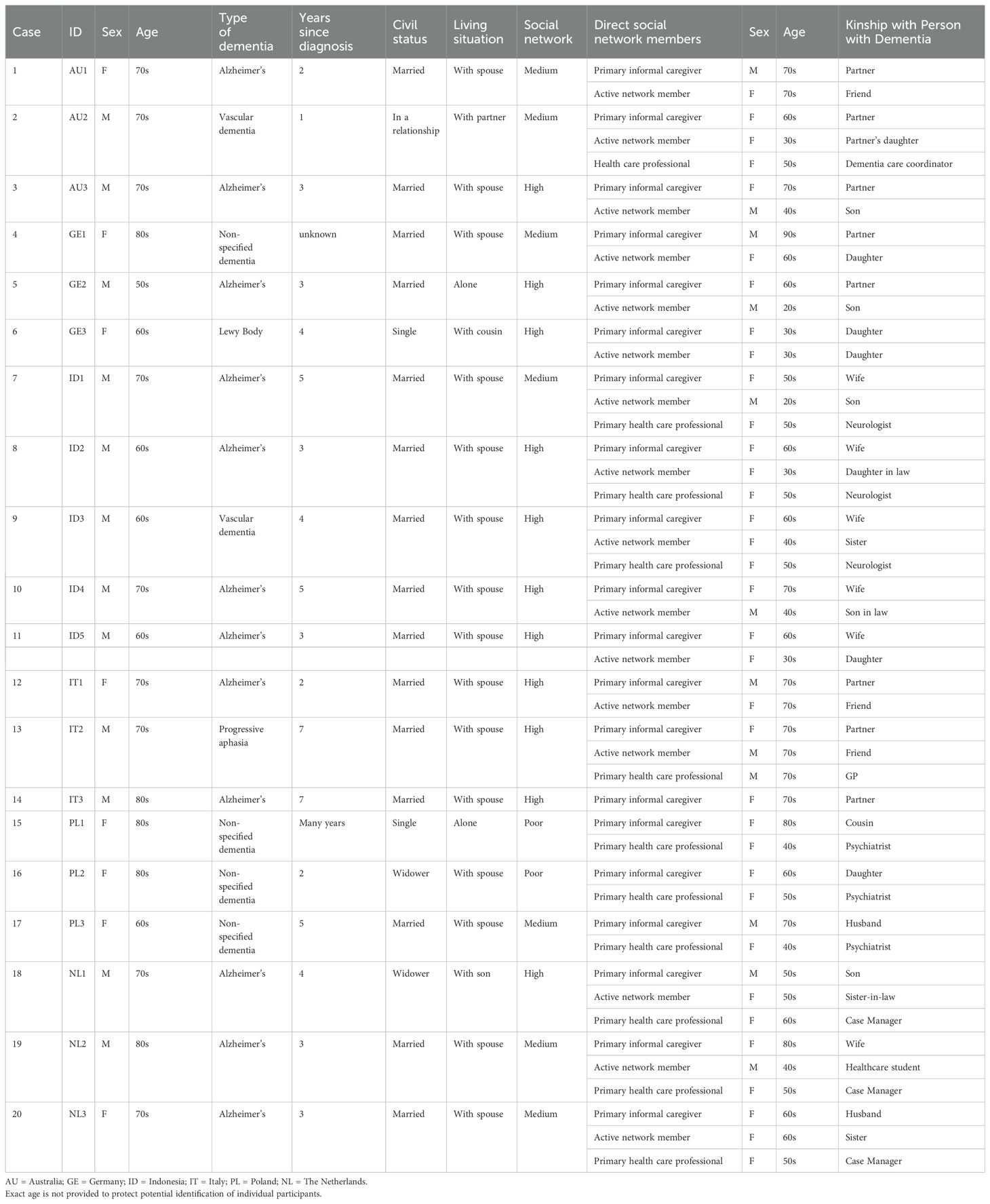

Of a total of 20 cases (n=67 participants), eight cases were complete members of four, 11 cases included three members each (8 cases without healthcare professionals and 3 cases without other network members) and 1 case was represented by two, a person with dementia and the informal caregiver. Table 3 provides detailed characteristics of individual cases and participants.

Twenty persons with dementia were interviewed: 12 males and 8 females. The average age was 72.8 years (range: 61 – 88 years). They were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease (n=12), vascular dementia (n=2), Lewy body dementia (n=1), progressive aphasia (n=1), or the non-specific type of dementia (n=4). Two persons with dementia lived alone, all others lived either with their spouse/partner (n=16), adult children (n=1) or other family members (n=1). Time from diagnosis ranged from 1 to 7 years (there were also 2 cases of ‘many years’ and ‘unknown). The social network levels of the participating persons with dementia varied: high (n=11), medium (n=7), and poor (n=2).

Of 20 primary informal caregivers, 14 were female and 15 were spouses. The mean age of the primary informal caregivers was 67 years. Sixteen active network members were involved in the study and eight were adult children of those people with dementia. They had a mean age of 48 years. Eleven health care professionals were involved in the current study. They were managers (n=3), psychiatrists (n=3), neurologists (n=2), a General Practitioner (n=1), and a dementia care coordinator (n=1).

3.2 Identification of social health markers

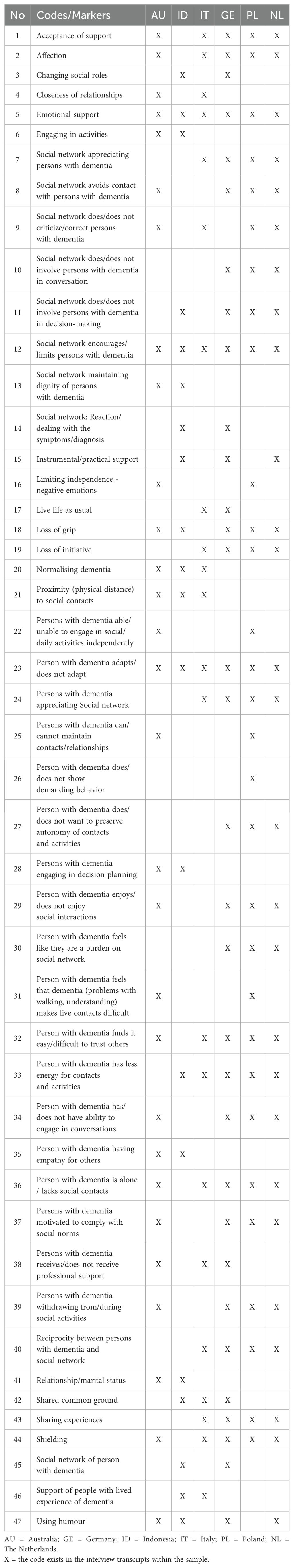

Iterative collaborative analyses yielded 47 codes/social health markers. All markers were used multiple times in the participating countries (Table 4).

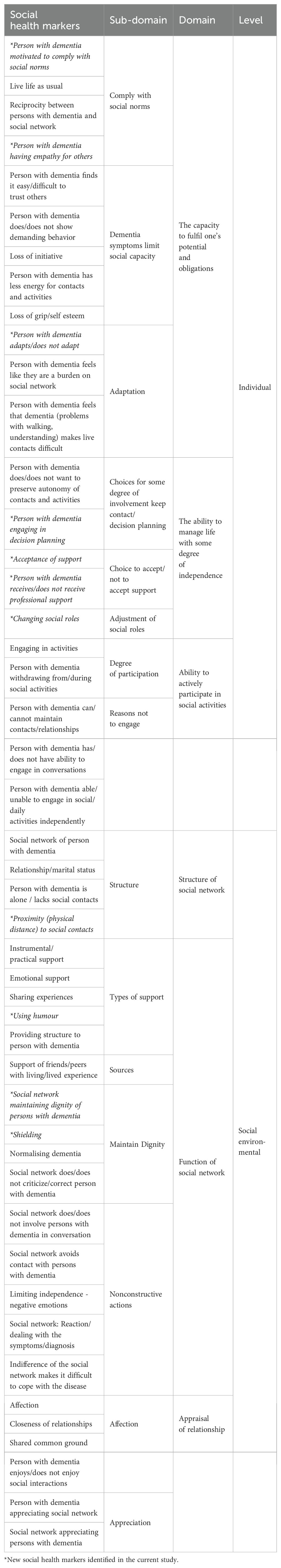

The markers were organized into six categories that are equivalent with the domains of the conceptual framework (18): capacities, independence, social participation, structure, function and appraisal (Figure 1). These domains are subsequently clustered into two levels: the individual and the social environmental. Table 5 provides an overview of social health markers, and domains. In this table, we also indicated some social health markers that have not used in previous epidemiological nor intervention studies.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of social health (18).

Below, we describe the storyline on markers of social health for persons with dementia in the level domains and sub-domains.

3.3 Individual level

3.3.1 Capacity to fulfill one’s potential and obligations

Persons with dementia described how they used their talents and skills to comply with social norms, in order to maintain social engagement. They did so by making efforts to live their life as usual, for example, by visiting friends, taking a walk, doing grocery shopping, preparing their own meals or visiting the physician independently when it was possible. As part of living life as usual, persons with dementia found it important to show empathy to others.

“I’d like to pay sometimes for the one [refer to persons with dementia’s friend] who didn’t have much money with him.” (Person with dementia, The Netherlands)

Persons with dementia identified reciprocity as an important social norm: if you get something, you want to give something back. Despite their limitations, persons with dementia expressed their desire to give something to others.

“She (the neighbor) says I’m good and helpful to her. I kept her spirits up while she was in the hospital.” (Person with dementia, Poland)

Persons with dementia and member of their social network mentioned several dementia symptoms and characteristics that limited the capacity to comply with social norms. As part of the condition, persons with dementia had issues on trusting others. It was reported that persons with dementia tended to be more suspicious toward others, even towards their close ones, for example:

“I myself start to think that people may think that I have a problem on my mind and that they think: ‘You don’t have to talk to that man because he doesn’t know anything anymore’.” (Person with dementia, The Netherlands)

“She (person with dementia) became more sensitive and feels mistreated easily.” (Health care professional, Poland)

Persons with dementia also lost some skills and physical functions, therefore they worried about being a burden to their social environment and were frustrated not to able to maintain the capacity they used to have. Dementia had affected them physically so that they lost energy for contacts and activities. Persons with dementia claimed that their loss of energy might have contributed to the fact that they became less active and lost initiative. With those changes, persons with dementia reported to lose their confidence and self-esteem.

Persons with dementia also reported feeling frustration.

“Sometimes I get lost in chaos because I can’t get certain things structured, sorted and then it looks as if a bomb has fallen in.” (Person with dementia, Germany)

Despite these limitations, persons with dementia emphasized their continuous efforts and perseverance to adapt to their current capabilities and health status, also in order to continue to comply with social norms and remain independent.

“I fight every day to be independent, to be self-reliant.” (Person with dementia, Germany)

“I write everything down on sticky notes and put it on the front of fridge.” (Person with dementia, Poland)

3.3.2 The ability to manage life with some degree of independence

Persons with dementia described several aspects of autonomy, which is about the state of being self-governing and to solve problems in life. We found that persons with dementia used their autonomy to make decisions on whether they want or do not want to preserve contacts or activities or to engage in decision planning. Also, we found that persons with dementia carefully weighed their capability to decide what daily activities to perform and how to perform these, to remain as independent as possible.

“What is still possible is to go out for a short time up and down the street. Not too far from home. To the bakery is fine. That’s not too far either. To the doctor … that’s also within walking distance.” (Person with dementia, Germany)

We also identified that persons with dementia used their autonomy to make decisions on professional and social support that was offered. Persons with dementia realized that that they can either accept or decline.

“I appreciate he (carer) takes me to the doctor, since I’m not sure I can write everything down and understand by myself.” (Person with dementia, Poland)

Persons with dementia made certain choices in life that changed their social roles. Like in one case, a person with dementia who was a leader in a social organization, decided to resign his position as a leader and continue to stay in the organization as a member. In this case, the person with dementia analyzed his capability and options, then independently made decision.

“Not that I don’t want, but I can’t do it in my condition now. I will still support them in many ways, but not as the leader.” (Person with dementia, Indonesia)

The social roles changing of persons with dementia eventually impacted their direct social network and social participation. The example of impact was expressed by a family carer and a person with dementia who decided to change their social roles.

“It used to be my husband who is active in the community, now, I need to replace him, because one of the members of the family need to join. It is our social obligation.” (Wife of person with dementia, Indonesia)

3.3.3 Ability to actively participate in social activities

Persons with dementia described the engagement in social activities such as keeping their usual habit to attend social functions on their local communities. Persons with dementia mentioned that these engagements positively impacted their mental health. Persons with dementia mentioned that the decision to participate often was driven by to their need to be productive and meaningful. For example, in one of our cases, the person with dementia was still keeping up her/his ability in writing. This made her very satisfied.

“I also write about my experiences in my dementia situation. In good days, I can concentrate a bit for two to three hours. When I read the things three days later [.] I think ‘Wow cool, you did a great job’. I’m always really happy.” (Person with dementia, Germany)

Some persons with dementia eventually decided to withdraw from social activities or from the interaction with loved ones due to the decline of their cognitive functions.

“I lost a lot of friends, because it was difficult for them to talk to me and that upset me. I withdrew from social contacts.” (Person with dementia, Poland)

“So right now, he’s a lot quieter and more withdrawn than he was previously. I mean, he was always a reasonably quiet guy, but he was maybe just a bit more interactive and getting involved in things, whereas now he’ll kind of sit on the sidelines. I guess by natural preference and same with the kids. I think probably previously, he would have just been a little bit more with them and asking them things when now he just sits back a little bit more.” (Daughter of person with dementia, Australia).

The reasons to join or not participate in social activities varied. Some persons with dementia explicitly mentioned how their cognitive decline negatively impacted their engagement in social activities or in conversations independently.

“I’m also getting tired of the conversation itself [….] it’s hard for me to think and stay sharp, try to listen.” (Person with dementia, The Netherlands)

3.4 Social environmental level

3.4.1 Structure of social network

The direct social network confirmed that the structure of social network influenced the perceived social support of persons with dementia. Proximity, the distance to network members, seemed to be important. Some persons with dementia mentioned feelings of loneliness due to physical distance when none of their family members lived nearby. On the other hand, some persons with dementia reported enjoying living in a small village where everyone knows each other and in which they can lean on ties developed in the past from before they got dementia. They and their families appreciated being embedded in the community.

“He (person with dementia) is still going to the mosque alone every morning. We are not worried because it is close to our house. Even if he is lost, then our neighbors will take him back home.” (Wife of person with dementia, Indonesia)

3.4.2 Function of social network

Persons with dementia acknowledged several types of support provided by the direct social network. They reported instrumental or practical support, for example, an offer to help with grocery shopping, accompanying to visit a physician or an offer to walk their dog on their ‘bad days’. Persons with dementia reported that this kind of practical supports reduced their burden knowing that they have somebody to rely on. Persons with dementia also identified emotional support. This was offered by the direct social network through various ways including sharing experiences like looking at pictures together with friends. The use of humor was also frequently mentioned by persons with dementia and the direct social network and identified as emotional support. Both parties confirmed that humor was helpful to break the boundaries and tension of the situation.

“These days the names of the people I just forget them. And I just say: ‘I’m so sorry about that, but I forgot your name again’. I try to do a lot with humor and sarcasm and obviously people don’t hold it against me and those who did just went away.” (Person with dementia, Germany)

Further, the direct social network mentioned how they empowered the persons with dementia to stay socially connected and contribute to daily life.

“If there is something he can do, then we let him do it. I said: ‘Here, Dad, can you help me carry something or so.’ Not because I necessarily need it, but just so that he feels a bit needed.” (Daughter of person with dementia, Germany)

The social network reported various resources of support. Apart from the direct network, family caregivers indicated support from neighbors and the community.

The direct social network reported what they did aiming to preserve persons with dementia’s dignity. They mentioned that they were aware that persons with dementia lost some skills and functions and gently corrected when needed. The direct social network bolstered person with dementia’s self-esteem by continuing to ask permission and advice.

“I still discuss things and ask for his (person with dementia) permission and advice although I do not know if he can understand it properly.” (Wife of person with dementia, Indonesia)

Sometimes the person with dementia observed such protective behaviors from the direct social network.

“I think she [wife] shields me a bit. In terms of um … she’ll know when I’m struggling, I think, and so she would just … shield me you know, just different chatter … different talk.” (Person with dementia, Australia)

Maintaining dignity could also result from the social network normalizing dementia as persons with dementia, so that they do not feel too bad about their condition, for instance by assuring the persons with dementia that forgetting something is a ‘normal thing’ for older persons.

“And I just tell her, ‘It’s just it’s just age’ (person laughs), you know. Yes, yes. So anyway, that’s it.” (Friend of person with dementia, Australia).

On the other hand, some persons with dementia mentioned that they were experiencing some non-constructive actions, which could be active (criticizing) and more implicit (avoiding, ignoring). One person with dementia felt like being ‘constantly criticized over doing something wrong or not good enough or not listening’. Persons with dementia also reported that the social network avoiding contact. Further, persons with dementia experienced that they were not involved in a conversation during a visit to the physician. Persons with dementia revealed that these non-constructive actions can be challenging for them. which made them feel not taken seriously.

“I have experienced so many times that as soon as my daughter sits next to me, the doctors act as if I am not even there.” (Person with dementia, Germany)

Health care professionals described observations of similar non-constructive actions from social network sometimes.

“The caregiver forgets that the patient is sitting next to her, it limits her. Talking about the patient in the third person, when she is sitting next to him, takes away some of her dignity, she (person with dementia) is treated like a child.” (Health care provider, Poland)

3.4.3 Appraisal of relationships

Persons with dementia indicated the quality of relationships within their social network to be important. They mentioned some gestures of affection by family and friends, but also from their pets, to be meaningful for them.

“Dori is a great dog. She is also a support in my life. On the day when I’m not feeling well, I look at her or when she’s lying there next to me … and that’s also such a stable factor in my life.” (Person with dementia, Germany)

“She obviously relies on me an awful lot and so. That’s sort of nice, in a way. Uhm, it’s it’s … She appreciates what I do for her, you know. Uhm? We, uh, we give each other lots of hugs (chuckles).” (Partner of person with dementia, Australia).

Persons with dementia reported that the degree of closeness with the social network influenced the quality of relationship. They mentioned that when the quality of relationship was satisfying, they enjoyed the social interaction, despite their functional challenges.

“We have very nice neighbors. We always go out for dinner and so on. Of course, I can’t say anything because I’m not that fast [fast here could mean = I am a bit slow]. But that’s always nice.” (Person with dementia, Germany)

Both persons with dementia and the direct social network emphasized that the affection that is shown to each other is highly appreciated by both parties.

“What is very important is the way my daughters deal with me, their love, and affection.” (Person with dementia, Germany)

4 Discussion

The current qualitative study contributes to the identification of social health markers from the perspective of persons living with dementia and their direct social network, including their primary informal and professional caregivers and other social network members. The current study also identified some social health markers that have not been used in epidemiological nor intervention studies. It led to the refinement of and therewith better understanding of the social health domains as defined in the recently developed framework (18). Interviews also revealed how persons with dementia used their remaining talents and skills to comply with social norms and to live their lives as usual.

In terms of individual level social health markers, we found that the person with dementia’s capacity was impacted by cognitive and functional changes to which they tried to adapt continuously. Autonomy was expressed by making choices in keeping contact or withdrawing socially, and accepting or declining support being offered. In general, being involved in decision making in daily life played a key role in preserving autonomy. We found a variety in degrees of participation in social activities as well as in reasons to join in activities. Persons with dementia mentioned that engaging in activities provide positive impact on their mental health.

In addition to traditional markers of social network structure such as marital status, living alone or lack of social contact, we found that proximity (physical distance) indeed is a relevant structural marker. Physical distance caused persons with dementia to feel isolated. Some persons with dementia who lived in a small village, where people know each other, felt more closely related to their social network in which they could lean on contacts from the time before they got ill. Previous research mentioned that living with dementia in rural area enhances the sense of self-sufficiency of persons with dementia (31). The neighborhood is perceived as a place with biographical attachment and emotion connections with familiar friends and relatives (32, 33) as well as a relational place for persons with dementia to engage and interact with familiar faces (34). In fact, the value of proximity for persons with dementia was the fundamental idea behind some programs such as dementia-friendly communities (35). This confirms the (more implicit) acknowledgement of this specific marker. Future studies may inform us on how to intervene on this specific marker to make persons with dementia in more urban areas obtain social health value from their neighborhood.

With regards to social network functions, we found that emotional support by using humor and sharing experiences were appreciated by both persons with dementia and the direct social network. The direct social network often supported persons with dementia to maintain their dignity, by active and more implicit empowerment. However, we also identified some non-constructive actions like not involving persons with dementia in conversations. Relevant markers on the appraisal of the relationship were affection and appreciation for example closeness of relationship and sharing common ground.

We found that persons with dementia attempted to live as normal as possible and had intentions to comply with social norms. These findings are consistent with previous literature. Review studies pointed out that persons with dementia aim to maintaining a normal situation in daily life (36) and continuity in their lives as a coping strategy (37). As a result of the fear of not being able to comply with social norms in social interactions, persons with dementia tended to exclude themselves from social participation (38). Therefore, health care professionals underlined the importance in maintaining ordinariness in life of persons with dementia to support their intention to comply with social norms (39). Whereas previous research showed that the level of persons with dementia’s empathy during their trajectory of illness is declining (40), we found that many of them still desired to show empathy to others. Efforts of persons with dementia to live life as normally as possible has been described in previous literature (36, 37) but not explicitly been labelled as an attempt to comply with social norms, obligations or tasks. We hypothesize that persons with dementia’s intention to live life as usual can be due to their intention to comply with social norms and the fear of being excluded. The complex interplay within these two relevant markers needs to be further explored in the future studies. For the most relevant markers identified, we discuss their relevance and novelty in relation to the existing literature below.

Our data showed that persons with dementia used their ability to manage life with some degree of independence for keeping contact and activities as well as to accept or refuse support being offered. Therewith, persons with dementia focused on autonomy with regard to daily life decisions rather than major end-of-life decisions such as advance care planning. This corresponds with the findings from several qualitative studies which found that persons with dementia are still maintaining their autonomy during the disease trajectory (41), especially to participate in making choices in everyday life (42). Even in the context of advance care planning conversations, persons with dementia highly appreciated and preferred discussing short-term non-medical topics (43) over deciding on advance directives. This emphasizes how the little things in life influence the quality of life of older adults (44, 45).

We found that the direct social network can influence persons with dementia in both positive and negative ways. Our study revealed that the most powerful positive approach was for family caregivers and other social network members to actively promote dignity of persons with dementia. This specific marker was found in all participating countries which illustrates its relevance, regardless of cultural background. Previous review studies pointed out that the social network helps preserving persons with dementia’s dignity by offering personalized care such as implementing patient centered care or by showing respect with involving persons with dementia during care process (46, 47). When persons with dementia are no longer able to make sound decisions for themselves, dignity still can be preserved by employing some persuasive actions (47).

We also found negative functioning of social network and non-constructive attitudes toward persons with dementia such as excluding them during conversations. This very active exclusion contradicts with previous studies that merely provide illustrations of passive-non-constructive attitude such as people being afraid to be around and avoiding persons with dementia although they have sufficient knowledge on this illness (48–50). Overall, these negative approaches emphasized how social health of persons with dementia is threatened by stigma. Stigma is a complex concept and varies amongst ethnic and culture (51) and widely described in relation to dementia (52). Stigmatization by the social network was shown to lead to self-stigma at the individual level, manifested in our study and confirmed in the literature by withdrawal from activities due to feelings of incompetence (52).

Our study provided empirical data on social health markers as well as identified new markers that have not used in previous epidemiological nor intervention studies. Next, future research is needed to unravel the interplay between markers within and between domains and levels and to study the association between social health as a concept, and cognitive decline and dementia. Further, to be able to study novel social health markers such as autonomy-in-everyday life, the development of instruments is essential.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The current study identified social health markers which were underexplored in extant dementia research that examined the association between social health and cognition/dementia. Secondly, we started with open coding and used the conceptual framework of social health in dementia to organize the codes (18). The fact that our inductive codes fit within this framework, underlines the credibility of our findings and of the framework. Thirdly, in order to provide uniformity of the data collection process, we used the same data collection method and topic guide in all participating countries. Also, we applied investigator triangulation for data analysis and interpretation, as we included multidisciplinary perspectives from our international research team which come from various educational backgrounds, namely sociologists, psychologists, neuropsychiatrists, geriatricians and nursing.

The current study has a number of inherent limitations/challenges due to the involvement of multiple countries and languages. The transcripts were drafted in original languages, but the codes were generated in English, which may have led to details getting ‘lost in translation’. In order to limit this loss of credibility, we managed to have at least two independent coders in each participating country. We iteratively developed a codebook including definitions with all partners from all different countries to facilitate the harmonization of the codes. Further, as we were restricted by ethical regulations in data sharing from each country, we shared and discussed data on the coding level. As a consequence, no single researcher had access to all the transcripts. This may have led to heterogeneity in the interpretation of the codes. As mentioned above, the researchers did, however, discuss the harmonisation and scope of each of the codes to minimise coding heterogeneity.

The current study also faced the reluctance of involvement of primary health care professionals. Health care professionals can be seen as ‘observer’. Therefore, the consequence of lacking healthcare voices is that in some cases we may have lost the “objective” voice in the description of examples of interaction between person with dementia, family and active network member.

5 Conclusions

The current international qualitative study identified and articulated novel social health markers both on the level of the person with dementia and on their social environment, that provide further insights into the recently established social health conceptual framework. Our results added refinement to the domains within the framework by the identification of new sub-domains as ‘dementia symptoms limit social capacity’ and ‘adaptation’ within the individual level. Instrument development and validation are essential next steps to enable measurement and implementation in ongoing cohort studies. This may provide further understanding of these markers and their interplay. Understanding the interplay between social markers may contribute to a more complete multifaceted perspective on the entire dementia patient journey from first symptoms to advanced disease. When used as a fundament in innovative intervention studies, these markers may ultimately contribute to developing interventions focused on preventing dementia and on living a meaningful life for persons with dementia and their social network.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MK: Resources, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Project administration, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. MV-D: Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. MP: Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Y-HJ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. EV: Writing – review & editing, Software, Investigation. SS: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. GO: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Software, Investigation. RC: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology. HB: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. ML: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology. KK: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Investigation. JR: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. DS: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Data curation. AG: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. IS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Investigation. MA: Writing – review & editing, Software, Data curation. CE: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project was supported through funding organizations under the aegis of JPND 733051082: Netherlands, ZonMw grant number 733050831; Australia, NHMRC RG181672 United Kingdom, Alz Society UK grant number 469; Germany, BMBF 01ED1905; and Poland, NCBiR (National Center for Research and Development in Poland, project number JPND/06/2020).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1384636/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Freak-Poli R, Wagemaker N, Wang R, Lysen TS, Ikram MA, Vernooij MW, et al. Loneliness, not social support, is associated with cognitive decline and dementia across two longitudinal population-based cohorts. J Alzheimers Dis. (2022) 85:295–308. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210330

2. van der Velpen IF, Melis RJF, Perry M, Vernooij-Dassen MJF, Ikram MA, Vernooij MW. Social health is associated with structural brain changes in older adults: the rotterdam study. Biol Psychiatry Cognit Neurosci Neuroimaging. (2022) 7:659–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2021.01.009

3. Marseglia A, Kalpouzos G, Laukka EJ, Maddock J, Patalay P, Wang HX, et al. Social health and cognitive change in old age: the role of brain reserve. Ann Neurol. (2023) 93(4):844–55. doi: 10.1002/ana.26591

4. Maddock J, Gallo F, Wolters FJ, Stafford J, Marseglia A, Dekhtyar S, et al. Social health and change in cognitive capability among older adults: findings from four European longitudinal studies. Gerontology. (2023) 69(11):1330–46. doi: 10.1101/2022.08.29.22279324

5. Tsutsumimoto K, Doi T, Makizako H, Hotta R, Nakakubo S, Makino K, et al. Association of social frailty with both cognitive and physical deficits among older people. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2017) 18:603–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.004

6. Ma L, Sun F, Tang Z. Social frailty is associated with physical functioning, cognition, and depression, and predicts mortality. J Nutr Health Aging. (2018) 22:989–95. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1054-0

7. Eramudugolla R, Huynh K, Zhou S, Amos JG, Anstey KJ. Social cognition and social functioning in MCI and dementia in an epidemiological sample. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (2022) 28:661–72. doi: 10.1017/S1355617721000898

8. Singleton D, Mukadam N, Livingston G, Sommerlad A. How people with dementia and carers understand and react to social functioning changes in mild dementia: a UK-based qualitative study. BMJ Open. (2017) 7. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016740

9. Toller G, Cobigo Y, Ljubenkov PA, Appleby BS, Dickerson BC, Domoto-Reilly K, et al. Sensitivity of the social behavior observer checklist to early symptoms of patients with frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. (2022) 99:e488–99. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200582

10. Patterson KM, Clarke C, Wolverson EL, Moniz-Cook ED. Through the eyes of others - the social experiences of people with dementia: a systematic literature review and synthesis. Int Psychogeriatr. (2018) 30:791–805. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216002374

11. Nickbakht M, Angwin AJ, Cheng BBY, Liddle J, Worthy P, Wiles JH, et al. Putting “the broken bits together”: A qualitative exploration of the impact of communication changes in dementia. J Commun Disord. (2022) 101:106294. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2022.106294

12. Dyer AH, Murphy C, Lawlor B, Kennelly SP, Study Group FTN. Social networks in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer disease: longitudinal relationships with dementia severity, cognitive function, and adverse events. Aging Ment Health. (2021) 25:1923–9. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1745146

13. Sabatini S, Martyr A, Gamble LD, Jones IR, Collins R, Matthews FE, et al. Are profiles of social, cultural, and economic capital related to living well with dementia? Longitudinal findings from the IDEAL programme. Soc Sci Med. (2023) 317:115603. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115603

14. Hackett RA, Steptoe A, Cadar D, Fancourt D. Social engagement before and after dementia diagnosis in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. PloS One. (2019) 14:e0220195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220195

15. Balouch S, Rifaat E, Chen HL, Tabet N. Social networks and loneliness in people with Alzheimer’s dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2019) 34:666–73. doi: 10.1002/gps.5065

16. Johannessen A, Engedal K, Haugen PK, Dourado MCN, Thorsen K. To be, or not to be”: experiencing deterioration among people with young-onset dementia living alone. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. (2018) 13:1490620. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2018.1490620

17. Birt L, Griffiths R, Charlesworth G, Higgs P, Orrell M, Leung P, et al. Maintaining social connections in dementia: A qualitative synthesis. Qual Health Res. (2020) 30:23–42. doi: 10.1177/1049732319874782

18. Vernooij-Dassen M, Verspoor E, Samtani S, Sachdev PS, Ikram MA, Vernooij MW, et al. Recognition of social health: A conceptual framework in the context of dementia research. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:1052009. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1052009

19. Joyce J, Ryan J, Owen A, Hu J, McHugh Power J, Shah R, et al. Social isolation, social support, and loneliness and their relationship with cognitive health and dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2021) 37. doi: 10.1002/gps.5644

20. Samtani S, Mahalingam G, Lam BCP, Lipnicki DM, Lima-Costa MF, Blay SL, et al. Associations between social connections and cognition: a global collaborative individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. (2022) 3:e740–e53. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00199-4

21. Sommerlad A, Sabia S, Singh-Manoux A, Lewis G, Livingston G. Association of social contact with dementia and cognition: 28-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort study. PloS Med. (2019) 16:e1002862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002862

22. Duffner LA, Deckers K, Cadar D, Steptoe A, de Vugt M, Köhler S. The role of cognitive and social leisure activities in dementia risk: assessing longitudinal associations of modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2022) 31:e5. doi: 10.1017/S204579602100069X

23. Zhou Z, Wang P, Fang Y. Social engagement and its change are associated with dementia risk among Chinese older adults: A longitudinal study. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:1551. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17879-w

24. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

25. Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 292:114523. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

26. Jeon YH, Shin M, Smith A, Beattie E, Brodaty H, Frost D, et al. Early implementation and evaluation of stepUp for dementia research: an Australia-wide dementia research participation and public engagement platform. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111353

27. Squires A. Methodological challenges in cross-language qualitative research: a research review. Int J Nurs Stud. (2009) 46:277–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.006

28. van Riet Paap J, Vernooij-Dassen M, Brouwer F, Meiland F, Iliffe S, Davies N, et al. Improving the organization of palliative care: identification of barriers and facilitators in five European countries. Implement Sci. (2014) 9:130. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0130-z

29. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. (2008) 62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

30. Erber AC, Arana B, Bennis I, Ben Salah A, Boukthir A, Castro Noriega M, et al. An international qualitative study exploring patients’ experiences of cutaneous leishmaniasis: study set-up and protocol. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:e021372. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021372

31. Blackstock KL, Innes A, Cox S, Smith A, Mason A. Living with dementia in rural and remote Scotland: Diverse experiences of people with dementia and their carers. J Rural Stud. (2006) 22:161–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.08.007

32. Li X, Keady J, Ward R. Transforming lived places into the connected neighbourhood: a longitudinal narrative study of five couples where one partner has an early diagnosis of dementia. Ageing Society. (2019) 41:1–23. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X1900117X

33. Ward R, Clark A, Campbell S, Graham B, Kullberg A, Manji K, et al. The lived neighborhood: understanding how people with dementia engage with their local environment. Int Psychogeriatr. (2018) 30:867–80. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217000631

34. Clark A, Campbell S, Keady J, Kullberg A, Manji K, Rummery K, et al. Neighbourhoods as relational places for people living with dementia. Soc Sci Med. (2020) 252:112927. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112927

35. Hebert CA, Scales K. Dementia friendly initiatives: A state of the science review. Dementia (London). (2019) 18:1858–95. doi: 10.1177/1471301217731433

36. Bjørkløf GH, Helvik A-S, Ibsen TL, Telenius EW, Grov EK, Eriksen S. Balancing the struggle to live with dementia: a systematic meta-synthesis of coping. BMC Geriatrics. (2019) 19:295. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1306-9

37. Górska S, Forsyth K, Maciver D. Living with dementia: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research on the lived experience. Gerontologist. (2017) 58:e180–e96. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw195

38. Donkers H, van der Veen D, Vernooij-Dassen M, Nijhuis-van der Sanden M, Graff M. Social participation of people with cognitive problems and their caregivers: a feasibility evaluation of the Social Fitness Programme: Social participation promotion. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. (2017) 32(12):e50–e63. doi: 10.1002/gps.4651

39. Gjernes T, Måseide P. Maintaining ordinariness in dementia care. Sociol Health Illn. (2020) 42:1771–84. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13165

40. Baez S, Manes F, Huepe D, Torralva T, Fiorentino N, Richter F, et al. Primary empathy deficits in frontotemporal dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. (2014) 6:262. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00262

41. D’Cruz M, Banerjee D. Caring for persons living with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic: advocacy perspectives from India. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:603231. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.603231

42. Smebye KL, Kirkevold M, Engedal K. How do persons with dementia participate in decision making related to health and daily care? A multi-case study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2012) 12:241. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-241

43. Tilburgs B, Vernooij-Dassen M, Koopmans R, Weidema M, Perry M, Engels Y. The importance of trust-based relations and a holistic approach in advance care planning with people with dementia in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics. (2018) 18:184. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0872-6

44. Rodgers V, Welford C, Murphy K, Frauenlob T. Enhancing autonomy for older people in residential care: what factors affect it? Int J Older People Nurs. (2012) 7:70–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2012.00310.x

45. Kane RA, Caplan AL, Urv-Wong EK, Freeman IC, Aroskar MA, Finch M. Everyday matters in the lives of nursing home residents: wish for and perception of choice and control. J Am Geriatr Soc. (1997) 45:1086–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05971.x

46. van der Geugten W, Goossensen A. Dignifying and undignifying aspects of care for people with dementia: a narrative review. Scand J Caring Sci. (2020) 34:818–38. doi: 10.1111/scs.12791

47. Tranvåg O, Petersen KA, Nåden D. Dignity-preserving dementia care: a metasynthesis. Nurs Ethics. (2013) 20:861–80. doi: 10.1177/0969733013485110

48. Chang CY, Hsu HC. Relationship between knowledge and types of attitudes towards people living with dementia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113777

49. Parveen S, Mehra A, Kumar K, Grover S. Knowledge and attitude of caregivers of people with dementia. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2022) 22:19–25. doi: 10.1111/ggi.14304

50. Rosato M, Leavey G, Cooper J, De Cock P, Devine P. Factors associated with public knowledge of and attitudes to dementia: A cross-sectional study. PloS One. (2019) 14:e0210543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210543

51. Herrmann LK, Welter E, Leverenz J, Lerner AJ, Udelson N, Kanetsky C, et al. A systematic review of dementia-related stigma research: can we move the stigma dial? Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. (2018) 26:316–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.09.006

Keywords: social health, social health markers, qualitative, multicountry analysis, dementia - alzheimer disease

Citation: Kristanti MS, Vernooij-Dassen M, Jeon Y-H, Verspoor E, Samtani S, Ottoboni G, Chattat R, Brodaty H, Lenart-Bugla M, Kowalski K, Rymaszewska J, Szczesniak DM, Gerhardus A, Seifert I, A’la MZ, Effendy C and Perry M (2024) Social health markers in the context of cognitive decline and dementia: an international qualitative study. Front. Psychiatry 15:1384636. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1384636

Received: 10 February 2024; Accepted: 22 July 2024;

Published: 19 September 2024.

Edited by:

Gaelle Eve Doucet, Boys Town National Research Hospital, United StatesReviewed by:

Stefanie Auer, University for Continuing Education Krems, AustriaWei Xu, Qingdao University Medical College, China

Copyright © 2024 Kristanti, Vernooij-Dassen, Jeon, Verspoor, Samtani, Ottoboni, Chattat, Brodaty, Lenart-Bugla, Kowalski, Rymaszewska, Szczesniak, Gerhardus, Seifert, A’la, Effendy and Perry. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martina S. Kristanti, c2ludGFAdWdtLmFjLmlk

Martina S. Kristanti

Martina S. Kristanti Myrra Vernooij-Dassen

Myrra Vernooij-Dassen Yun-Hee Jeon

Yun-Hee Jeon Eline Verspoor4

Eline Verspoor4 Suraj Samtani

Suraj Samtani Giovanni Ottoboni

Giovanni Ottoboni Rabih Chattat

Rabih Chattat Henry Brodaty

Henry Brodaty Krzysztof Kowalski

Krzysztof Kowalski Joanna Rymaszewska

Joanna Rymaszewska Dorota M. Szczesniak

Dorota M. Szczesniak Ansgar Gerhardus

Ansgar Gerhardus Muhamad Zulvatul A’la

Muhamad Zulvatul A’la Christantie Effendy

Christantie Effendy Marieke Perry

Marieke Perry