- 1Qatar Biomedical Research Institute, Hamad bin Khalifa University, Doha, Qatar

- 2College of Health and Life Sciences, Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Doha, Qatar

- 3World Innovation Summit for Health (WISH), Qatar Foundation, Doha, Qatar

- 4Community Outreach, Qatar Autism Family Association, Doha, Qatar

- 5Center for Autism Spectrum Disorders, Childrens National Health System, Rockville, MD, United States

- 6Department of Biological Sciences, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 7Autism Department, Shafallah Center for Children with Disabilities, Doha, Qatar

Introduction: The unprecedented impact of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) has had profound implications on the ASD community, including disrupting daily life, increasing stress and emotional dysregulation in autistic children, and worsening individual and family well-being.

Methods: This study used quantitative and qualitative survey data from parents in Qatar (n=271), to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on autistic children and their families in Qatar. The questionnaire was a combination of open-ended (qualitative) and closed-ended (quantitative) questions to explore patterns in the experiences of the different families, as well as to contrive themes. The survey was created in a way to evaluate the psychological, academic/intervention, economic, and other impacts of the pandemic related measures on a sample of multicultural families residing in the State of Qatar during the peak period of confinement and physical distancing in 2020. Data acquisition involved the utilization of Google Forms. Subsequent quantitative analysis employed the SPSS software and chi-square analysis for numerical examination, enabling the characterization of the studied population and exploration of associations between parental stress levels and variables such as employment status, therapy accessibility, presence of hired assistance, and alterations in their childs skills. Concurrently, qualitative data from written responses underwent thorough categorization, encompassing themes such as emotional isolation, mental or financial challenges, and difficulties in obtaining support.

Results: Parents expressed distress and disturbance in their daily lives, including profound disruptions to their childrens access to treatment, education, and activities. Most parents reported deteriorations in their childrens sleep (69.4%), behavioral regulation (52.8%), and acquired skills across multiple domains (54.2%). Parents also reported decreased access to family and social support networks, as well as decreased quality of clinical and community support. Qualitative analysis of parental responses revealed that child developmental regression was an important source of parental stress.

Discussion and conclusion: The greater impact of the pandemic on autistic children and their families emphasizes the need for accessible and affordable health, education, and family services to manage their special needs.

Introduction

There is no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic, which has rapidly swept through the world, has affected nearly all aspects of life; including the health and safety of all people, especially individuals affected by acute and chronic illnesses. Individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are no less immune to the direct and indirect impacts of this pandemic. Early data suggests that people with developmental disabilities may be even more susceptible to adverse health outcomes and death from COVID-19 (1, 2). Measures taken by most countries to control and limit the spread of COVID-19 included the closure of schools and centers providing treatment, rehabilitation, educational and training services. Nonetheless, efforts were made by most service providers to find alternative ways to compensate, even partially, for these restrictions to alleviate the great burden on families of autistic individuals. While the measures taken by countries to control and limit the spread of COVID-19 are myriad in number, they can be addressed in the following categories: impact on 1) the provision of health care services, including diagnostic, treatment, and rehabilitation services; 2) educational services; 3) autistic individuals and their families; 4) medical and intervention service providers; and 5) ASD research.

ASD is characterized by pervasive impairments in social reciprocity, communication, stereotyped behaviors, and restricted interests (3). Diagnosis of ASD requires a multidisciplinary assessment by healthcare service providers. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, centers and clinics around the world, including in Qatar, usually had a long waiting list for assessment (4). With the rise of this pandemic, many of these services were interrupted for varying periods, forcing families to postpone diagnostic evaluations, in turn negatively affecting the outcome of any intervention for the child, as earlier diagnosis is strongly associated with positive lifelong outcomes for autistic individuals (5–9). Early intervention (implemented before the age of four) is associated with gains in cognition, language, adaptive behavior, social behavior, and overall quality of life for both the child and the family (10–13).

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated health inequalities and increased mental health problems on a worldwide scale. Many studies have been published recently that report increased mental health challenges across multiple study settings (e.g. USA, England, India, Lebanon, Qatar, Singapore, etc.) imposed by COVID-19 (14–17), including specifically among autistic children (18). There has also been a “silver lining” of increased access to telehealth services, which long-term may address underlying disparities in healthcare systems through the dissemination of more sustainable and equitable practices for delivering efficient mental healthcare services (19). An online survey of ASD professionals highlighted several vulnerability factors of autistic individuals in coping with the COVID-19 pandemic, including challenges related to core ASD characteristics, neuropsychological traits, executive functioning difficulties, and comorbid mental health problems all vulnerability factors reported by professionals (20). Results of initial research have indeed shown a significant negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD (21–23). Autistic individuals are particularly vulnerable to the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Lockdowns seeking to stem the spread of the pandemic led to closures of critical support institutions, such as schools, diagnostic and treatment clinics and agencies, and outpatient mental and medical healthcare, as well as support groups and organizations. Online learning, used widely to maintain access to education, has been an insufficient replacement for many autistic individuals, due to their need for specialized direct instruction and hands-on learning. One study examining the telehealth adaptation of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety in autistic children found challenges related to distractibility and reduced control of the environment, as well as decreased reciprocity and engagement in sessions (18). Attempts to provide online educational instruction for autistic students have also substantially increased demands on both educators and families to support students learning (24), often leaving families with little more than recommendations for how to provide instruction themselves (25). In addition to educational challenges, autistic individuals and their families are also impacted by reduced access to vocational training and support, home-based intervention, and access to invaluable outlets for leisure (26). Indeed, reduced independence and disruptions to routines were reported by most families of autistic children (26).

Yet the impacts of the pandemic may not be universally negative. One recent study on the psychological impact of the pandemic on autistic individuals in Spain, showed reduced psychopathology and stress and improved feeding on both caregiver-report and self-report, despite decreases in social interaction and face-to-face relationships, with particular benefits for young adults, perhaps due to reduced stressors related to these external relationships and demands (27). In contrast, caregivers reported increased levels of stress and anxiety for themselves. The contrast between the experiences of autistic individuals and those of their caregivers in this study may be at least partially attributable to the already high-stress levels for family members of autistic individuals before the pandemic (28–30). A study based in Saudi Arabia found that parents of autistic children reported increased stress and anxiety related to caring for their autistic children during the COVID-19 pandemic (31). Parents of younger children, and mothers in particular, reported the highest levels of anxiety, and parental anxiety and mental health together predicted perceived mental health needs. Parents of autistic children may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns, to their pre-existing high-stress levels which make the added stresses faced by all parents (e.g., unemployment, working from home, caring for typically developing children engaging in online learning, reduced access to social supports) even more impactful.

The objective of the present study is to evaluate the effect of measures taken to control COVID-19 pandemic on the daily functioning and well-being of autistic individuals and their families in Qatar, a country that has made critical gains in recent decades in expanding access to ASD diagnosis and treatment. Specifically, this study investigates parent-reported impacts of COVID-19 mitigation measures (i.e., lockdowns restricting access to services and requiring families to remain at home) on the daily functioning of autistic children, access to services, and parent psychological well-being. We hypothesized that parental stress would be significantly associated with parent employment status, access to in-home therapy, access to specialized intervention, presence of hired help in the home (e.g., housekeeper, nanny, etc.), and regression in child skills. Of note, hired help in the home is relatively common in Qatar and these untrained individuals often provide substantial support to families in caring for autistic children in the home. Thus, this variable was important to include in this specific cultural context. The qualitative data not only allowed us to add more context to the individual situation of each family and provided an open view of the differences in experiences during that time but also played a crucial role in strengthening our study design and findings. By considering the qualitative data questions, we were able to gain more perspective and contrive additional information about the common and uncommon challenges parents faced during this period. This holistic approach, combining qualitative and quantitative data, contributes to a comprehensive understanding of the effects of COVID-19 mitigation measures on the daily functioning and well-being of autistic individuals and their families in Qatar. Examining the impact of COVID-19 on autistic children in Qatar is particularly vital, as it allows for a nuanced understanding of how cultural and contextual factors unique to the region may shape the experiences of families and individuals with autism.

Materials and methods

Study design

To examine and evaluate the effect of measures taken to control the COVID-19 pandemic on autistic individuals and their families, a mixed-method approach (32), collecting quantitative and qualitative survey data from parents of autistic children in Qatar was used. To collect the data, we created a questionnaire to be completed through Google Forms. The survey took place between September and December of 2020. The Participants gave their informed consent via the online platform or by email. This study was approved by Qatar Biomedical Research Institute Institutional Review Board (IRB) research ethics committee. All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Participants

A convenience sample of 271 parents who self-identified as having at least one child aged between 3 and 18 years with a formal ASD diagnosis was used. All families resided in the State of Qatar during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were recruited via online advertisement through various social media channels, organizations (e.g., Qatar Autism Society) and via existing databases of autistic individuals (33) that have previously given their consent to be contacted for ASD-related research. We contacted parents of children with the diagnosis of ASD by telephone or by e-mail (online form). Those with more than one autistic child were asked to focus on just one child (of their own choosing) in their responses.

Instruments

Google Forms was used to create an online parent survey to be shared through the dissemination of a hyperlink. All participants provided electronic informed consent that contained information about the purpose of the study, procedures, benefits of participating, voluntary participation, and contact information of the researchers. Since no questionnaire existed for evaluating the target concept, the researchers in this study created one. All the survey questions were developed based on the available literature in the subject matter e.g. The Autism Parenting Stress Index (APSI) and the World Health Organizations Quality of Life Questionnaire with Parents of Children with Autistic Disorder (34, 35). The survey questions were not contrived directly from these questionnaires, they were rather used as a guide as to how to design our survey and which questions to ask. The questionnaire was pilot tested first on a sample of three parents of autistic children to assess the studys measures for reliability, and to establish validity before embarking on the full study. Parents were asked to evaluate appropriateness of response options, time taken to complete it, and clarity of the questions in terms of language, wording, and meaning. Necessary corrections were considered and made by authors as appropriate. All measures and informed consent were then translated from English to Arabic by bilingual researchers in this study to enable families to complete forms in their preferred language [N=58 (21.4%) English, N=213 (78.6%) Arabic]. The final version of the questionnaire was comprised of 36 multiple-choice and open-ended questions about sociodemographic information, the impact of the pandemic on autistic childrens daily life, access to information and services/support during the pandemic period, parents pandemic experience and primary challenges, and parents overall health status and stress levels.

Procedures

The preliminary version of the questionnaire was revised in an iterative process by three of the authors (FA, SA, and IG). All the researchers involved in data collection are Arabs fluent in both English and Arabic who have extensive experience in ASD research within the Arab community. The study employed two distinct recruitment methods. Initially, participants were reached through email, wherein they received a survey link. Families who chose to engage accessed, completed, and submitted the survey electronically. Alternatively, a second recruitment mode involved contacting families via phone. During this outreach, the studys purpose was explained, and families were given the option to either complete the survey over the phone with the researcher or independently. Consent was obtained electronically through an online form in all instances. Notably, this approach was particularly relevant given the studys timeframe coinciding with social distancing measures and the closure of centers, schools, and clinics. The survey took approximately 10- 15 minutes to fill out. If a parent had more than one autistic child, a separate survey was filled for each child. The survey pertained to the COVID-19 pandemic, and more specifically, the period of confinement and physical distancing in 2020.

Data analysis

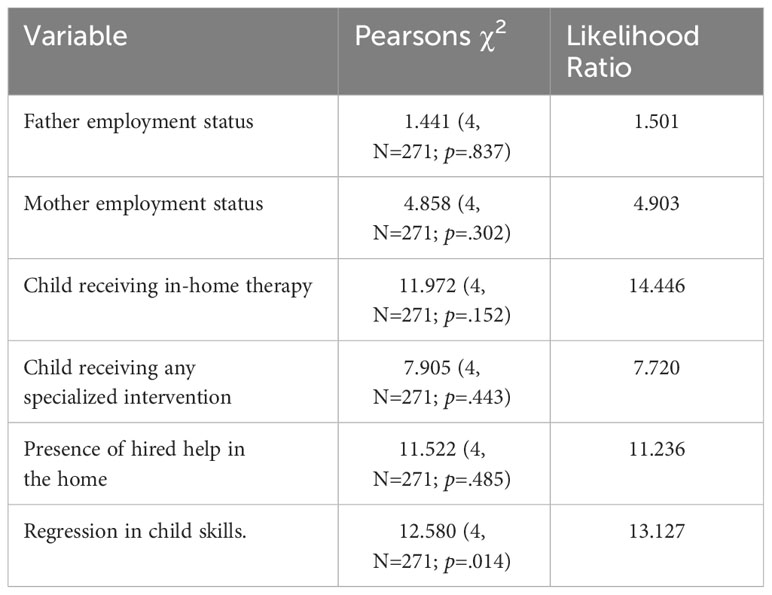

The final raw data were downloaded from Google Forms into a Microsoft Excel file for analysis using SPSS software (Version 26.0). For the quantitative data, descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and examine survey responses. Then, chi square and likelihood ratio tests were used to investigate the association between parents stress levels and employment status, access to in-home therapy, access to any sort of specialized intervention, presence of hired help in the home (e.g., housekeeper, nanny, etc.), and regression in child skills. In order to identify the challenges that parents with autistic children face during the pandemic, the qualitative data collected by written responses through semi-structured forms was analyzed using thematic content analysis technique by identifying themes and subthemes and associating them with examples (36). Three authors (FA, SA, and IG) independently evaluated responses and placed them into categories (e.g., social isolation, mental and psychological problems, financial issues, access to regular support, service interruption, etc.). In the rare instances of discrepant category attribution, the authors reached consensus through discussion.

Results

Sociodemographic information

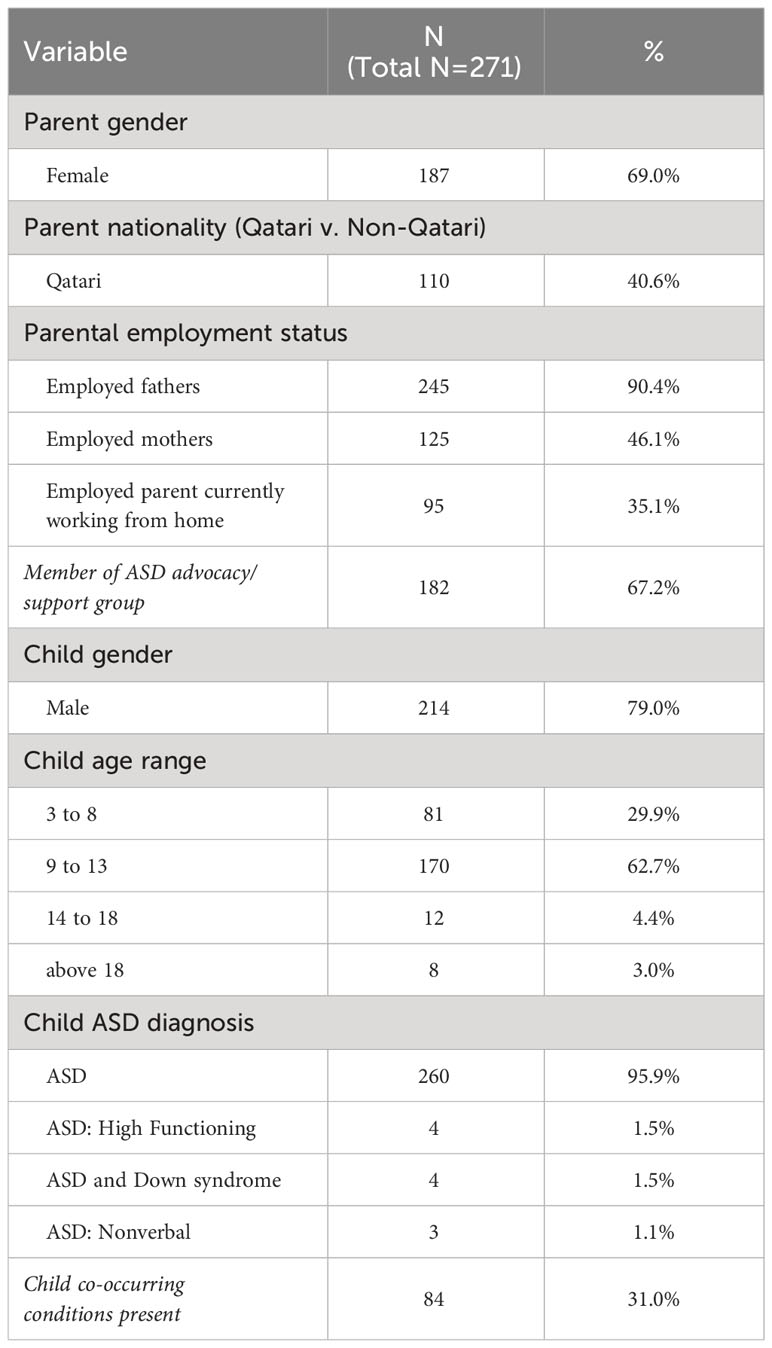

Parents provided basic sociodemographic information about themselves and their autistic child, including parent gender, nationality, and work status, as well as child age, gender, and diagnoses, along with the number of children at home and membership in ASD advocacy/family support networks. The majority of the participants were female (mothers; 66.4%), and non-Qatari (59.4%). Almost all fathers (90.4%) were employed, while most mothers (53.9%) were unemployed. The majority of parents do not work from home (64.9%) and are members of ASD advocacy and family support networks (67.2%). An average of four children lived at the home, including autistic children. The vast majority of autistic children were male (79.0%; n=214) with most (62.7%) falling between the ages of 9 and 13. Approximately one-third (31.0%) of the children had co-occurring conditions such as ADHD or epilepsy (see Table 1 for more details). To ensure a comprehensive understanding of each participants current level of functioning, our survey questions were occasionally supplemented with sub-questions. Some questions offered multiple options for selection, followed by inquiries about the presence of comorbid conditions, utilizing a yes/no format. Participants selecting “yes” were then prompted to specify the particular condition. Notably, information regarding the childs verbal ability was not explicitly addressed in a dedicated question; instead, it relied on data reported in the comorbid conditions or additional comments sections of relevant survey questions.

Survey responses: quantitative analyses of survey results

Impact of COVID-19 on autistic children and their families

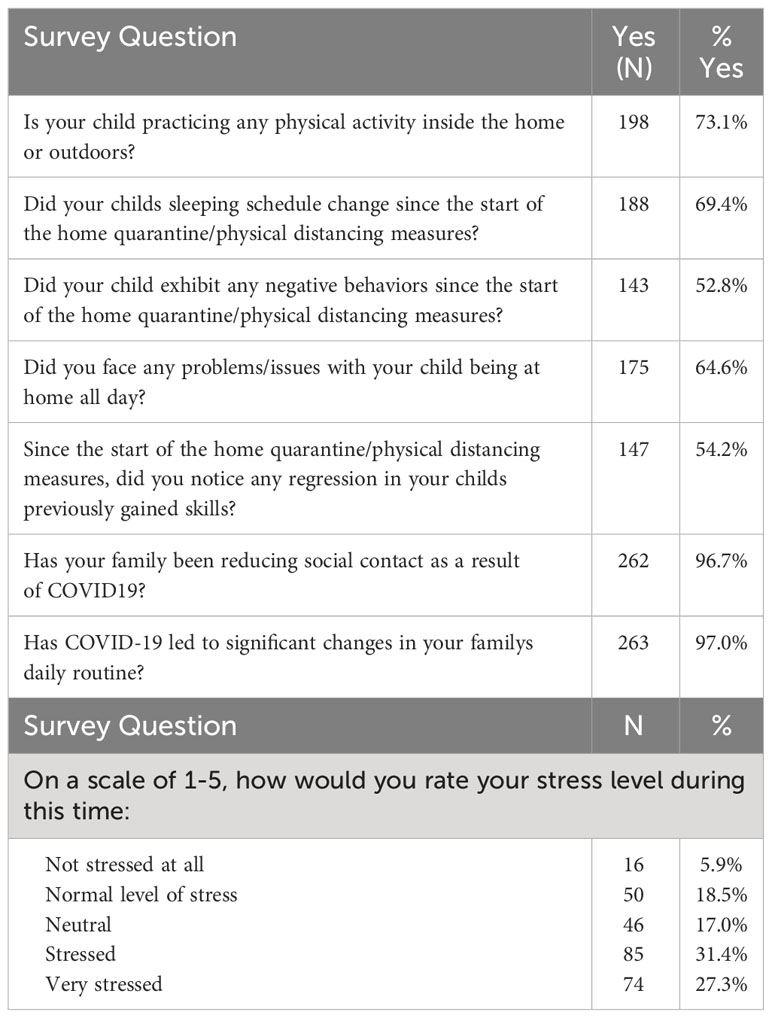

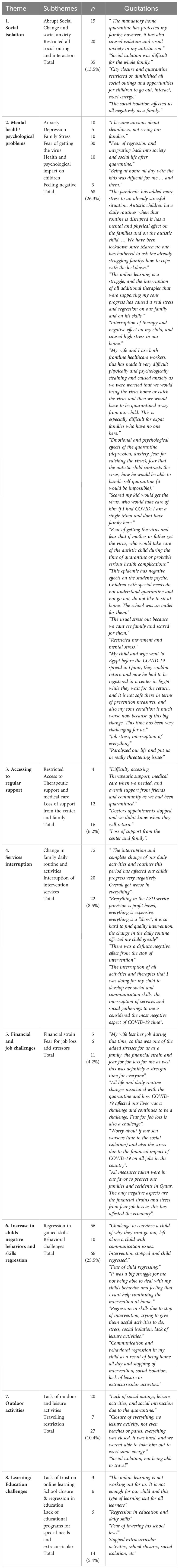

Parent survey responses indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant on autistic children in Qatar. As seen in Table 2, the majority of parents reported that their childrens sleeping schedules had been disrupted or changed since the start of home quarantine (69.4%). Most reported that their children displayed new problem behaviors (52.8%), such as hyperactivity, tantrums, self-injurious behavior, new stereotyped behaviors, and/or disrupted sleep. Most parents also endorsed a noticeable regression in their childrens previously gained skills (54.2%), such as difficulty following instructions, reduced self-help skills, worsening social skills, increased attention issues, and/or reductions in communication and academic skills. Furthermore, most parents (64.6%) attributed specific problems/issues to the challenges of being home all day (e.g., boredom, aggression, mood/irritability issues, etc.). However, the vast majority of parents (73.1%) indicated that their children were still participating in physical activities, either inside or outside the home. The COVID-19 pandemic was also found to have a significant impact on the daily lives of families in this study. The vast majority of parents (97.0%) reported that COVID-19 caused substantial changes in their daily routine, reduced social contact (96.7%), and increased their stress levels (58.7%).

Chi square tests were then used to assess the relationship between parental stress levels and key variables of interest, including: parent employment status, access to in-home therapy, access to any sort of specialized intervention, presence of hired help in the home (e.g., housekeeper, nanny, etc.), and regression in child skills. Findings indicated that from the predicted variables (Table 3), parent stress was significantly associated only with a regression in the childs previously gained skills, such that child skill regression was associated with increased parental stress [χ2 (4, N=271) = 12.580, p=.014), such that child regression increased the likelihood of high parental stress thirteen-fold (Likelihood Ratio=13.127).

Table 3 Summary results of Chi square and likelihood ratio tests of predictors with parent stress level.

Impact of COVID-19 on accessing and receiving services/support

As shown in Table 4, the majority of parents in this study stated that they had difficulty receiving support from extended families/friends/community during the pandemic (57.6%), that they could not access usual support due to COVID-19 (63.1%), that they were only partially or not at all supported by their families and community (55%), and that they did not have access to any online ASD support (e.g. family support groups, therapeutic support) (63.5%). Most also reported that their autistic children were not participating in online learning (58.7%) and did not receive any intervention sessions from a qualified specialist during the home quarantine period (76.0%).

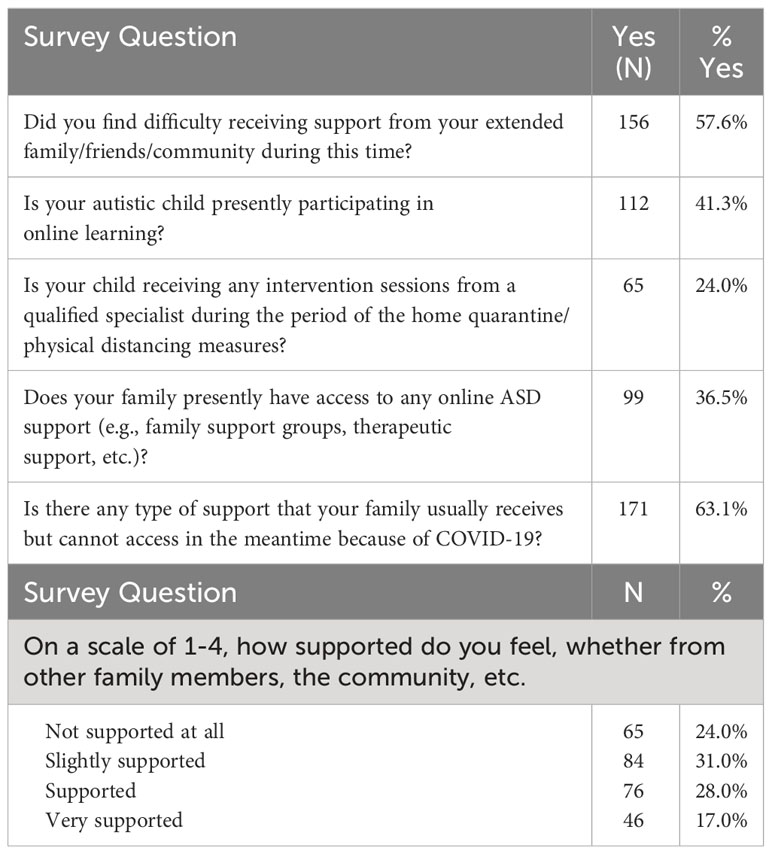

Qualitative analyses: the main challenges families face during the pandemic

Parents opinions regarding the main challenges they faced during the pandemic were analyzed with thematic content analysis (Table 5). The main challenges that parents face during the pandemic are grouped under social isolation, mental health/psychological problems, access to regular support, service interruption, financial, and job challenges, increase in childs negative behaviors and skill regression, outdoor activities, and learning/education challenges. The highest frequency is in the mental health/psychological problems, increase in childs negative behaviors and skills regression categories, social isolation, and lack of outdoor activities. The lowest frequency is in the Financial and job challenges category. The sub-categories with the highest frequency are regression in gained skills (n =56), fear of getting the virus (n =30), lack of outdoor activities (n =20) and restricted all social outings and interaction (n = 20).

Discussion

This study used parent report surveys to gain insight into the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lives of autistic children and their families in the State of Qatar. As expected, parents reported high levels of distress and disruption to their daily lives, as has been widely reported throughout the world. The majority of parents reported that their childrens access to activities, education, and treatment was either substantially reduced or non-existent. Parents also reported reduced access to family and social support networks during this critical time of increased stress. Interestingly, parental stress was not significantly associated with support factors, such as access to treatment and social support, nor was it associated with parental employment status. This is in direct contrast to prior studies of families caring for autistic children, which routinely find an association between familial stress and access to support services (29, 37). It is possible that families were under so much stress during this intense period of lockdown that even access to support provided minimal relief.

The data also indicate that families had minimal access to support and that available supports were routinely of lower quality than those provided before the COVID-19 pandemic; thus, the lack of association indicates that the services provided were insufficient to impact family stress levels. Parental stress was significantly associated with child developmental regression, indicating that children whose support needs increased even more during this time due to skill loss likely increased parental stress. Furthermore, the majority of parents indicated that their childrens sleeping habits had been interrupted or changed since the start of home quarantine, that their children had shown negative behaviors, and that there had been a clear regression in the childrens previously acquired abilities. Beyond the quantitative data collected in this study, the qualitative data analysis provides valuable additional insights into the unique experience of parenting an autistic child during the COVID-19 pandemic. While many of the experiences endorsed by parents in quantitative data were likely shared by parents of neuro-typical children (e.g., reduced access to activities, financial and employment stress, lack of connection to support networks) (38), the qualitative data reveal stressors and experiences unique to parents of autistic children (39). Throughout the major themes that emerged, two major underlying threads were clear that connected the stress expressed in each of the themes and subthemes.

Firstly, parents emphasized that they had already been under enormous stress with insufficient support to care for their children prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns. Parents indicated that services for ASD were already scarce and that there was little societal understanding and support for the challenges that they and their children faced before the pandemic. Parents in this study shared feeling “forgotten” by society, stating that because their needs were already overlooked and their children ignored before the COVID-19 pandemic, it felt clear to them that the unique impact of the pandemic on their children and families was not recognized or considered by society at large. Thus, while they reported concerns that are similar to those echoed by parents of neuro-typical children, these concerns emerged in the context of pre-existing distress and unmet support needs. The lockdown was often framed in their comments as a new layer of stress that felt “impossible” to handle on top of their pre-existing experiences.

Secondly, parents highlighted how their childs symptoms of ASD compounded the stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown experienced by all families. Although all families experienced stressful disruptions to their daily routines, parents in this study noted that their children relied intensively on predictable routines before the pandemic, even more so than their peers did, with even small changes having the potential to be highly disruptive. These families thus felt the catastrophic changes wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic even more intensely. Similarly, families around the world were negatively impacted by the lack of opportunities for social interaction for their children. The lack of social interaction was particularly worrisome to families in this study, as difficulties with social communication and engagement skills are a core feature of ASD, which are targeted directly in treatment and education for these children. Families expressed their worries that the social isolation of the pandemic would lead to further delays in their children and/or loss of skills. Concerns about regression, which occurs much more commonly in autistic children than in neuro-typical children, also emerged across themes. Parents highlighted that not only was their child failing to learn and gain new skills during this time, but also that there was a very real risk that their child might lose previously gained skills (and in some cases had already). In addition to developmental regression and skill loss, parents also shared that their children experienced exacerbations in pre-existing negative behaviors or developed new negative behaviors, as a unique expression of the impact of the lockdowns on autistic children.

Finally, their childrens underlying difficulties with learning and social attention attempted at online education and intervention, when available, extremely difficult, or even impossible to access. Since these learners require different types of instruction, they were often left with recommendations for instruction to be practiced by the families, rather than direct instruction. The online learning format substantially increased demands on both educators and families to support students learning around the world (24), with minimal time and resources to adapt special education curriculums to online learning with the unique needs of autistic students in mind.

An additional challenge not captured by the present survey is the delay in diagnosis and identification. In addition to the impact on treatment and educational services, diagnostic assessments have also been affected, causing delays in diagnosis for many individuals. This in turn can have severe negative long-term outcomes due to delays in access to treatments and appropriate interventions (9). Access to early diagnosis and intervention is a strong predictor of long-term outcomes (40, 41), meaning that children whose diagnosis and access to treatment are delayed during this time are at substantial risk for even more negative long-term outcomes with higher support needs.

Limitations

The current study also has some limitations. First, like many online research studies, our sample may reflect some degree of selection bias. In particular, we expect certain underestimations of extreme cases, that is, people who were either minimally or very affected by the pandemic. Second, the results of this study are limited to the immediate experience at the onset of the pandemic and, therefore, to the short-term effects of the pandemic. Future studies also need to consider the long-term effects of the pandemic as it is becoming increasingly clear that this pandemic and any future pandemic are likely to have a prolonged course. Thirdly, the study methodology and data exclusively involve input from parents/guardians, resulting in the absence of perspectives from autistic individuals themselves. This constitutes an additional limitation to the study that should be taken into account in future research.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic and recurrent lockdowns have already had an enormous impact on our world, and their effects will be felt for years to come. As vaccinations continue to become more available and access to services and education steadily increase, we cannot simply “go back to normal.” It will be critical for providers and educators to consider the effects of the ongoing pandemic on childrens development, academic progress, and emotional well-being. Moreover, the medical community should learn from this crisis and to support autistic families in navigating burdensome times to enable autistic children to thrive. As evidenced by the high levels of distress described by parents in this study, the development of personalized formulation-based-psycho-social interventions to support and engage autistic individuals and their caregivers to help cope with the consequences of the pandemic and similar waves in the future is critical (20). As highlighted in this study, there have been substantial disruptions to the lives and developmental progress of autistic children. These disruptions will have lasting effects on their skills, including potential skill loss. Adjustments will need to be made to educational, treatment planning that adjust developmental, and educational goals to remediate skills and begin helping children catch up on lost time. The emotional impacts of this time will also need to be considered, including that many children may have had a traumatic reaction to the disruptions in their routines and lives. Trauma-informed approaches to both treatment and education are likely to have much more relevance in the field of ASD going forward than they have in the past.

There will be a pressing need for society to not only stop neglecting the needs of autistic children and their families but to begin actively supporting them in enhanced ways. Local and national governments will need to consider increased supportive initiatives for psychological support, financial support, training workshops, and online sessions for families and providers. This should also include additional support and incentives for provider and teacher training in ASD. The interruption of service provision whether home-, school-, or center-based, by experienced and highly skilled multi-disciplinary professionals is expected to have a negative effect on these service providers as they have acquired their skills and continue to enhance them through their daily practices while working with autistic individuals. This has also limited opportunities for trainees to develop critical skills needed for working in ASD. Reduced training opportunities will in turn mean fewer qualified providers are available, in a system that is already unable to fully meet the needs of autistic children. Increasing access to services through support to providers will also be critical. Moving forward into the “new normal,” governments around the world will need to make substantial and lasting investments in training, family support, education, and services for this vulnerable group of children and their families. The greater impact of the pandemic on the autistic children and their families emphasizes the need for accessible and affordable (continued) health, education, and family services to manage their special and immediate needs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Qatar Biomedical Research Institute - Institutional Review Board (IRB). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants legal guardians/next of kin. The parents/legal guardians of the adult participants provided written informed consent as they are usually the ones who provide consent on their behalf.

Author contributions

FA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IG: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA-H: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. ML: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. HA-S: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. FA-F: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. AR: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. AN: Writing – review & editing. MT: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Qatar Biomedical Research Institute supported this study.

Acknowledgments

We are immensely grateful to the families and their children for their time and participation in the research. We thank Qatar Family Association; The Shafallah Center, Renad Academy, and all other private centers that participated in the study. The authors would also like to thank the Qatar Biomedical Research Institute (QBRI) for providing the funding and support for the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1322011/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Sabatello M, Landes SD, McDonald KE. People With Disabilities in COVID-19: Fixing Our Priorities. The American journal of bioethics: AJOB. (2020) 20(7):187–190. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2020.1779396

2. Turk MA, Landes SD, Formica MK, Goss KD. Intellectual and developmental disability and COVID-19 case-fatality trends: TriNetX analysis. TriNetX analysis. Disability and health journal (2020) 13(3):100942. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100942

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. (2013). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

4. Wiggins LD, Baio J, Rice C. Examination of the time between first evaluation and first autism spectrum diagnosis in a population-based sample. J Dev Behav pediatrics: JDBP. (2006) 27:S79–87. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604002-00005

5. Stahmer AC, Collings NM, Palinkas LA. Early intervention practices for children with autism: descriptions from community providers. Focus Autism other Dev Disabil. (2005) 20:66–79. doi: 10.1177/10883576050200020301

6. Boyd BA, Odom SL, Humphreys BP, Sam AM. Infants and toddlers with autism spectrum disorder: early identification and early intervention. J Early Intervention. (2010) 32:75–98. doi: 10.1177/1053815110362690

7. Strain SP, Schwartz SI, Barton EE. Providing early interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorders: what we still need to accomplish. J Early Intervention. (2011) 33:321–32.

8. Warren Z, McPheeters ML, Sathe N, Foss-Feig JH, Glasser A, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. A systematic review of early intensive intervention for autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. (2011) 127:e1303–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0426

9. Elder JH, Kreider CM, Brasher SN, Ansell M. Clinical impact of early diagnosis of autism on the prognosis and parent-child relationships. Psychol Res Behav Manage. (2017) 10:283–92. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S117499

10. Remington B, Hastings RP, Kovshoff H, degli Espinosa F, Jahr E, Brown T, et al. Early intensive behavioral intervention: outcomes for children with autism and their parents after two years. Am J Ment retardation: AJMR. (2007) 112:418–38. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[418:EIBIOF]2.0.CO;2

11. Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M, Winter J, Greenson J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics. (2010) 125:e17–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0958

12. Zwaigenbaum L, Bauman ML, Choueiri R, Kasari C, Carter A, Granpeesheh D, et al. Early intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder under 3 years of age: recommendations for practice and research. Pediatrics. (2015) 136 Suppl 1:S60–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3667E

13. Vivanti G, Dissanayake C, Victorian ASELCC Team. Outcome for children receiving the early start denver model before and after 48 months. J Autism Dev Disord. (2016) 46:2441–9. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2777-6

14. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatry. (2020) 52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

15. Wadoo O, Latoo J, Reagu SM, et al. Mental health during COVID-19 in Qatar. Gen Psychiatry. (2020) 33:e100313. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100313

16. Newlove-Delgado T, McManus S, Sadler K, Thandi S, Vizard T, Cartwright C, et al. Child mental health in England before and during the COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet Psychiatry. (2021) 8:353–4. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30570-8

17. Vadivel R, Shoib S, El Halabi S, El Hayek S, Essam L, Gashi Bytyci D, et al. Mental health in the post-COVID-19 era: challenges and the way forward. Gen Psychiatry. (2021) 34:e100424. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100424

18. Kalvin CB, Jordan RP, Rowley SN, Weis A, Wood KS, Wood JJ, et al. Conducting CBT for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder during COVID-19 pandemic. J Autism Dev Disord. (2021) 51:4239–47. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04845-1

19. Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, Nordentoft M, Crossley N, Jones N, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:813–24. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2

20. Bellomo TR, Prasad S, Munzer T, Laventhal N. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with autism spectrum disorders. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. (2020) 13:349–54. doi: 10.3233/PRM-200740

21. Mutluer T, Doenyas C, Aslan Genc H. Behavioral implications of the covid-19 process for autism spectrum disorder, and individuals Comprehension of and reactions to the pandemic conditions. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:561882. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.561882

22. Suzuki K, Hiratani M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with neurodevelopmental disorders when school closures were lifted. Front Pediatr. (2021) 9:789045. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.789045

23. Dekker L, Hooijman L, Louwerse A, Visser K, Bastiaansen D, Ten Hoopen L, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and their families: a mixed-methods study protocol. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e049336. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049336

24. Hurwitz S, Garman-McClaine B, Carlock K. Special education for students with autism during the COVID-19 pandemic: “Each day brings new challenges”. Autism: Int J Res Pract. (2022) 26:889–99. doi: 10.1177/13623613211035935

25. Autism Speaks. Special report - COVID-19 and autism: Impact on needs, health, and healthcare costs (2021). Available online at: https://act.autismspeaks.org/site/DocServer?docID=4002.

26. Baweja R, Brown SL, Edwards EM, Murray MJ. COVID-19 pandemic and impact on patients with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. (2022) 52:473–82. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-04950-9

27. Lugo-Marin J, Gisbert-Gustemps L, Setien-Ramos I, Espanol-Martin G, Ibanez-Jimenez P, Forner-Puntonet M, et al. COVID-19 pandemic effects in people with Autism Spectrum Disorder and their caregivers: Evaluation of social distancing and lockdown impact on mental health and general status. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2021) 83:101757. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101757

28. Smith LE, Hong J, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Almeida DM, Bishop SL. Daily experiences among mothers of adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. (2010) 40:167–78. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0844-y

29. Kheir N, Ghoneim O, Sandridge AL, Al-Ismail M, Hayder S, Al-Rawi F. Quality of life of caregivers of children with autism in Qatar. Autism: Int J Res Pract. (2012) 16:293–8. doi: 10.1177/1362361311433648

30. DesChamps TD, Ibanez LV, Edmunds SR, Dick CC, Stone WL. Parenting stress in caregivers of young children with ASD concerns prior to a formal diagnosis. Autism research: Off J Int Soc Autism Res. (2020) 13:82–92. doi: 10.1002/aur.2213

31. Althiabi Y. Attitude, anxiety and perceived mental health care needs among parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Saudi Arabia during COVID-19 pandemic. Res Dev Disabil. (2021) 111:103873. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103873

32. Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Sage Publications (2017).

33. Alshaban F, Aldosari M, Al-Shammari H, El-Hag S, Ghazal I, Tolefat M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of autism spectrum disorder in Qatar: a national study. J Child Psychol psychiatry Allied disciplines. (2019) 60:1254–68. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13066

34. Silva LM, Schalock M. Autism Parenting Stress Index: initial psychometric evidence. J Autism Dev Disord. (2012) 42:566–74. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1274-1

35. Skevington SM, Lotfy M, OConnell KA, WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. (2004) 13(2):299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00

36. Roberts K, Dowell A, Nie JB. Attempting rigor and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Med Res Method. (2019) 19:66. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0707-y

37. Pilapil M, Coletti DJ, Rabey C, DeLaet D. Caring for the caregiver: supporting families of youth with special health care needs. Curr problems Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2017) 47:190–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2017.07.003

38. Gayatri M, Puspitasari MD. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on family well-being: A literature review. Family J (Alexandria Va.). (2022), 10664807221131006. doi: 10.1177/10664807221131006

39. Isensee C, Schmid B, Marschik PB, Zhang D, Poustka L. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on families living with autism: An online survey. Res Dev Disabil. (2022) 129:104307. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104307

40. Turner LM, Stone WL. Variability in outcome for children with an ASD diagnosis at age 2. J Child Psychol psychiatry Allied disciplines. (2007) 48:793–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01744.x

Keywords: COVID-19, social restrictions, ASD, stress, support

Citation: Alshaban FA, Ghazal I, Al-Harahsheh ST, Lotfy M, Al-Shammari H, Al-Faraj F, Thompson IR, Ratto AB, Nasir A and Tolefat M (2024) Effects of COVID-19 on Autism Spectrum Disorder in Qatar. Front. Psychiatry 15:1322011. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1322011

Received: 15 October 2023; Accepted: 31 January 2024;

Published: 20 February 2024.

Edited by:

Cecilia Montiel Nava, The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, United StatesReviewed by:

Elisabetta Filomena Buonaguro, University of Naples Federico II, ItalyAnna Urbanowicz, Deakin Univeristy, Australia

Copyright © 2024 Alshaban, Ghazal, Al-Harahsheh, Lotfy, Al-Shammari, Al-Faraj, Thompson, Ratto, Nasir and Tolefat. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fouad A. Alshaban, ZmFsc2hhYmFuQGhia3UuZWR1LnFh

Fouad A. Alshaban

Fouad A. Alshaban Iman Ghazal

Iman Ghazal Sanaa T. Al-Harahsheh

Sanaa T. Al-Harahsheh Mustafa Lotfy4

Mustafa Lotfy4 Fatema Al-Faraj

Fatema Al-Faraj I. Richard Thompson

I. Richard Thompson Allison B. Ratto

Allison B. Ratto